Abstract

There is limited data on the bleeding safety profile of direct oral anticoagulants, such as rivaroxaban, in low- and middle-income country settings like Kenya. In this prospective observational study, patients newly started on rivaroxaban or switching to rivaroxaban from warfarin for the management of venous thromboembolism (VTE) within the national referral hospital in western Kenya were assessed to determine the frequency of bleeding during treatment. Bleeding events were assessed at the 1- and 3-month visits, as well as at the end of follow-up. The International Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ISTH) and the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) criteria were used to categorize the bleeding events, and descriptive statistics were used to summarize categorical variables. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression model was used to calculate unadjusted and adjusted associations between patient characteristics and bleeding. The frequency of any type of bleeding was 14.4% (95% CI: 9.3%-20.8%) for an incidence rate of 30.9 bleeding events (95% CI: 20.1-45.6) per 100 patient-years of follow-up. The frequency of major bleeding was 1.9% while that of clinically relevant non-major bleeding was 13.8%. In the multivariate logistic regression model, being a beneficiary of the national insurance plan was associated with a lower risk of bleeding, while being unemployed was associated with a higher bleeding risk. The use of rivaroxaban in the management of VTE was associated with a higher frequency of bleeding. These findings warrant confirmation in larger and more targeted investigations in a similar population.

Keywords: direct oral anticoagulants, venous thromboembolism, bleeding, Kenya, rivaroxaban

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. It is 1 of the leading causes of disability-adjusted life years lost, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).1,2

The management of VTE involves choosing among several classes of anticoagulant medications, which vary considerably in terms of ease of administration, drug–drug and drug–food interactions, monitoring requirements, efficacy, safety, and cost. The commonly used options include heparins, Vitamin K antagonists (VKA, primarily warfarin), and direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs).3–5 The DOACs offer several advantages over other treatment options including fixed-dosing, no need for routine monitoring, faster onset of action (negating the need for bridging therapy), fewer drug–drug and drug–food interactions, and a lower risk of major bleeding. These agents were approved on the basis of landmark clinical trials evaluating their use in the management of VTE.6–9 In the EINSTEIN trials, rivaroxaban was shown to be non-inferior to warfarin with regard to the primary efficacy outcome (recurrent VTE), while having a significantly lower risk of major bleeding8,9; critically, a significantly lower risk of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH). 10 These observed trends apply to the entire class of DOACs, as shown in a meta-analysis by van Es et al. 11 While the lower risk of ICH seems to be a class effect, the impact of DOACs on other bleeding outcomes seems to be more varied. On the other hand, rivaroxaban has been associated with an increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding in some12–14 but not all studies, 15 particularly in patients with cancer. 16 Even for the outcome of ICH, there seems to be a differential risk among the various DOAC agents, with rivaroxaban seemingly being associated with the greatest risk among the DOACs, albeit still better than using warfarin. 17 The above notwithstanding, the second update of the CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report recommends the use of DOACs over VKAs for the initiation and treatment phases of anticoagulant therapy for VTE patients. Among patients with cancer, DOACs are recommended over low molecular weight heparin (LMWH). 14

Unfortunately, from published literature, there is only limited investigation on populations of African descent, as the majority of patients enrolled in these studies were white, with black patients making up less than 5% of the DOAC arms. Only the EINSTEIN-DVT and the Hokusai-VTE trials included patients from Africa, all of whom were from South Africa, who made up 3.7% and 4.4% of the study populations, respectively.8,18

Several post-marketing observational studies have been published since the EINSTEIN trials, focusing on the real-world efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban in the management of VTE. A summary of the findings from these studies is presented in Table 1. These studies have largely re-affirmed the efficacy of rivaroxaban. However, the findings regarding the frequency of bleeding are varied. These variable findings could be attributed to different study methodologies, different follow-up durations, and different study populations. Most of these have been conducted outside Africa, predominantly in Europe. Only the XALIA-LEA and the GARFIELD-VTE studies enrolled patients from Africa; only the former included patients from Kenya: 12 out of a total of 1285 participants.20,25

Table 1.

Summary of Efficacy and Safety Data for Rivaroxaban in VTE.

| Study | N | Mean Age (y) | Mean Follow-Up Duration (Days) | VTE Recurrence (%) | Any Bleed (%) | Major Bleed (%) | GI Bleed (%) | ICH (%) | CRNMB (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EINSTEIN-DVT 8 | 1731 | 55.8 | 365 | 2.1 | a | 0.8 | a | <0.1 | 7.3 |

| EINSTEIN-PE 9 | 2419 | 57.9 | 365 | 2.1 | a | 1.1 | a | a | 9.5 |

| XALIA 19 | 2619 | 59 | 239 | 1.4 | 11.4 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.2 | a |

| XALIA-LEA 20 | 1285 | 59.6 | 184 | 1.4 | 7.6 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 0.2 | |

| Pooled XALIA & XALIA-LEA 21 | 3904 | 58 | 225 | 1.4 | 10.1 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.2 | a |

| HOT-PE 22 | 519 | 57 | 90 | 0.6 | a | 1.2 | 10.9 | a | 6.0 |

| ROSE 23 | 1532 | 63 | 84 | a | a | 1.5 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 4.9 |

| Dresden 24 | 418 | 61 | 911 | 1.9 | 45.5 b | 3.8 | a | a | 17.7 |

| GARFIELD-VTE 25 | 4791 | 61 | 365 | 3.7 | 9.1 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.1 | |

| Remote-V 26 | 308 | 62 | 180 | 1.4 | a | 1.1 | 0.4 | 0 | 4.3 |

| FIRST 27 | 1262 | 59 | 607 | 0.6 | 10.4 | 0.9 | 1.8 | a | 6.4 |

Abbreviations: CRNMB, clinically relevant non-major bleeding; VTE, venous thromboembolism; ICH, intracranial hemorrhage.

Not reported.

Defined by the authors as any bleeding requiring medical attention.

These findings highlight the importance of conducting phase IV post-marketing studies that track the real-world experiences when medications are introduced into varied populations that might otherwise not be sufficiently represented in clinical trials.

One of the main factors contributing to the limited use of DOACs in LMIC settings in Africa is the prohibitive cost that has limited access, especially to patients who rely on the public health sector. In response, the Anticoagulation Clinic based at Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital (MTRH) (Eldoret, Kenya) has partnered with Bayer® East Africa Limited to provide rivaroxaban (the second FDA-approved DOAC after dabigatran) at a subsidized price. This has expanded access to the medication to a public sector patient population that did not previously have access and is not typically included in clinical trials. While several large-scale randomized controlled trials including participants from Africa have recently been completed, there are limited data on the real-world experiences with DOACs when used in routine care in public sector settings in this region. 28

Given the dearth of real-word evidence of the use of DOACs in patients of African descent, and in low-resource settings such as Kenya, we sought to characterize the real-world bleeding-related side effects observed when utilizing rivaroxaban for the management of VTE among patients in the public sector with newly identified anticoagulation needs and for patients switching from warfarin to rivaroxaban.

Methods

Study design

This analysis was part of a broader prospective observational study assessing the pharmaco-economic considerations of rivaroxaban versus warfarin conducted at the Anticoagulation Clinic of MTRH, Eldoret, Kenya. The objective of this analysis was to determine the safety of rivaroxaban in the management of VTE in a Kenyan cohort.

Study site

The clinic provides comprehensive services including INR testing, direct medication dispensation in pill boxes as indicated, and management of adverse drug reactions in 1 convenient location. The clinic is staffed by clinical officers, pharmaceutical technologists, and clinical pharmacists and guided by protocols developed in conjunction with cardiologists who are available for consultation in the event of complications or clinical concerns.

Study population, consent, and ethical approval

The study population included patients diagnosed with VTE being managed by the MTRH anticoagulation clinic who provided informed consent for participation in the study. This included patients being treated with rivaroxaban from the onset of VTE diagnosis as well as patients transitioning from warfarin to rivaroxaban. The study was approved by the Institutional Review and Ethics Committee (IREC) at Moi University/MTRH.

Enrollment began in March 2020 and was completed at the end of March 2021. Participants were required to be 18 years or older, have a confirmed VTE diagnosis, follow up with the MTRH Anticoagulation Team (inpatient/outpatient), and provide written informed consent, individually or via next of kin. Participants were excluded if they were pregnant or breastfeeding (due to rivaroxaban being pregnancy category C and our protocol recommendation of LMWH for VTE in pregnancy) or if they were participating in another study. This study was conducted during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, and patients who declined participation were able to access rivaroxaban if they were appropriate clinical candidates. The restrictions on travel and clinic operation as a result of government-mandated COVID-19 lockdowns made DOACs an especially desirable treatment option during this time as the need for frequent follow-up and travel to clinics was reduced.

Sampling and interventions

Convenience sampling was employed to enroll patients into the study. Patients with newly diagnosed VTE and initiating anticoagulation therapy were placed on rivaroxaban (Xarelto® supplied by Bayer® as part of an Access Program)15 mg twice daily for 3 weeks, after which their dose was transitioned to 20 mg daily for the intended duration of anticoagulation. Patients previously on warfarin were transitioned to rivaroxaban at 20 mg daily, provided the INR at the time of the switch was <3.0. When patients had an INR above 3.0, rivaroxaban was started 3 days later.

Data collection

Data were collected over the course of patient follow-up at the clinic including at the initial encounter (upon enrollment into care), at the end of 1 month, and at 3 months (scheduled anticoagulation stop date for the majority of patients). Each of these data collection times was designed to coincide with the anticipated routine clinic appointments. At the first encounter, demographic information (age, sex, marital status, residence), clinical information (details of VTE diagnosis, comorbidities, liver function, renal function, concurrent medications), socioeconomic information (employment status, income source, insurance, education, family, transportation), and consent for participation were obtained. At the subsequent visits, additional clinical information (VTE recurrence, bleeding episodes, adverse drug reactions, new comorbidities, symptoms of liver and renal dysfunction, and concurrent medications) was obtained. Clinical events (recurrent VTE, bleeding events, other adverse reactions) were verified and evaluated by the clinicians at the anticoagulation clinic. The means by which these events were evaluated was left to the discretion of the treating clinicians, using the relevant treatment guidelines. Patients unable to make clinic appointments were contacted via their respective mobile phone numbers on file to address any safety concerns arising from medication use.

Data analysis

Data analysis was carried out using the Stata ® statistical software package (College Station, TX). Data were censored for patients who were lost to follow-up. The baseline characteristics were compared between patients starting anticoagulation with rivaroxaban and those switching from rivaroxaban by means of the Student's t-test, with the corresponding P values. Bleeding frequencies were summarized for the overall study cohort as well as by categorical variables using descriptive statistics including the calculation of 95% confidence intervals around the mean bleeding frequency. Bleeding events and the frequency of events were categorized according to the recommendations of the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC). 29 For comparative purposes, bleeds were also classified as per the International Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ISTH) definitions. 30 The incidence proportion of major bleeding and/or clinically relevant non-major bleeding (CRNMB) in the current study was compared with that in the landmark EINSTEIN trials. This was done while cognizant of the fact that the study populations being compared were somewhat different, owing to the limited recruitment of individuals from Sub-Saharan Africa as well as the stricter inclusion criteria adopted in the EINSTEIN trials. The bleeding rate from the EINSTEIN trials was therefore utilized as the most representative description of the bleeding rate in the general population for the comparison with this cohort. A 2-tailed Chi-square test was used to compare the frequency of bleeding among patients started on rivaroxaban versus those making the switch from warfarin. Unadjusted odds ratio for bleeding was calculated.

Univariate, unadjusted analyses were completed using logistic regression to determine which characteristics (switch from warfarin, gender, age >60, current marital status, presence of comorbid cancer or cardiovascular disease, distance from clinic, transport costs, education level, type of employment, enrolled in NHIF, and baseline INR) were associated with an increased risk of any type of bleed. Univariate associations with a P-value <.1 were then included within a multivariate logistic regression model to determine if statistically significant associations persisted after adjustment.

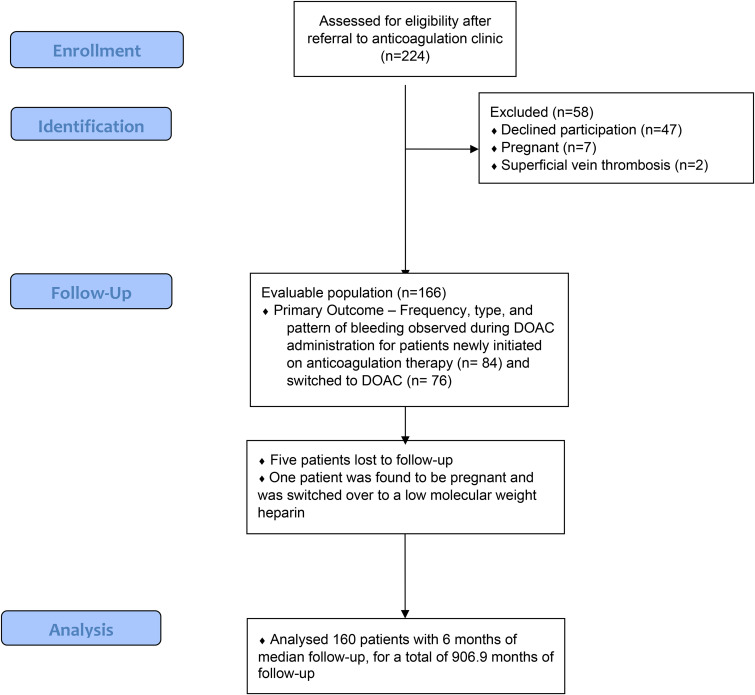

Results

A total of 224 patients were screened for enrollment, and 166 were enrolled into the study as depicted in Figure 1. Five patients were lost to follow-up (3.0%), and 1 participant was removed from the study due to pregnancy leading to the final analysis including 160 patients. Of these, 116 were female (72.5%) and 44 were male (27.5%) with a median age of 49 years (IQR, 36-62) as seen in Table 2. Participants switching from warfarin to rivaroxaban were significantly older than those initiating anticoagulation with rivaroxaban; mean age (SD) 53.7 (16.5) versus 46.7 (14.9), mean difference 7 (95% CI 2.1-11.9, P-value <.01). There were no significant differences between the patient groups with regard to other demographic and clinical characteristics.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Table 2.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Study Population.

| Variable | New on Rivaroxaban (n=84) | Switched From Warfarin to Rivaroxaban (%) (n=76) | Combined (n=160) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 46.7 (14.9) | 53.7 (16.5) | 50 (17.2) | .01* | |

| Median age (IQR) | 44 (26.5) | 54 (22.5) | 49 (36-62) | ||

| Mean follow-up duration (days) | 166.1 | 174.4 | 170.1 | ||

| Male | 27 | 17 | 44 (27.5%) | .08 | |

| Female | 57 | 59 | 116 (72.5%) | .08 | |

| Presence of comorbidity | 49 | 43 | 92 (57.5%) | .82 | |

| Use of NSAIDS/antiplatelet agents | 5 | 7 | 12 (7.5%) | .44 | |

| VTE diagnosis | Lower limb DVT only | 69 (82.1%) | 59 (77.6%) | 128 (80%) | .24 |

| PE | 11 (13.1%) | 9 (11.8%) | 20 (12.5%) | .41 | |

| DVT & PE | 2 (2.4%) | 5 (6.6%) | 7 (4.4%) | .10 | |

| Sagittal sinus thrombosis | 1 (1.2%) | 0 (0) | 5 (3.1%) | NA | |

| Sigmoid sinus thrombosis | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3%) | NA | ||

| Transverse sinus thrombosis | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3%) | NA | ||

| Mesenteric vein thrombosis | 1 (1.2%) | 0 (0) | NA | ||

| Proximal jugular vein thrombosis | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3%) | NA | ||

*Denotes statistically significant difference (P-value for significance: <.05).

Of the 160 patients included in the final analysis, 128 patients (80%) had lower limb deep venous thrombosis (DVT), 20 (12.5%) presented with only PE, 7 had both DVT & PE (4.4%) while 5 (3.1%) had DVT not involving the lower limbs (see Table 2).

Occurrence of bleeding

The frequency of any type of bleeding in the entire cohort over the study period was 14.4% (95% CI: 9.3%-20.8%). None of the patients whose data were censored had suffered an event at the time of censoring.

Among all patients (n=23) who suffered a bleeding event, the majority of these occurred among female patients (19 of 23; 82.6%). Based on the total duration of follow-up for the study participants, this translates to an incidence rate of 30.9 bleeding events (95% CI, 20.1-45.6) per 100 patient-years of follow-up. The frequency of bleeding among patients with different VTE diagnoses was 14.1%, 20%, and 16.7% among patients with DVT, PE, and DVT and PE, respectively. The difference in the frequency of bleeding was not statistically different between patients with different VTE diagnoses: DVT versus PE (difference: 5.9%, 95% CI −2.99%-16.4%); DVT versus DVT and PE (difference: 2.6%, 95% CI −3.0%-35.5%); PE versus DVT and PE (difference 3.3%, 95% CI −35.4%-16.3%). Among patients newly started on rivaroxaban, most of the bleeds occurred in the first 3 weeks (8 of 13, 61.5%), while most bleeds among patients switching from warfarin occurred after 3 weeks, (8 of 10, 80%) as seen in Table 3.

Table 3.

Timing of Rivaroxaban Bleeding Adverse Events.

| Timing of Bleed | Intervention | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median Time To Bleed (Days) | Total no. of Patients with a Bleed in First 21 Days (%) | Dose Modification | Permanent Discontinuation | Temporary Discontinuation | Continue with Same Dose | |

| New to rivaroxaban | 14 | 8/13 (61.5) | 7 | 0 | 5 | 1 |

| Switch from warfarin to rivaroxaban | 28 | 2/10 (20) | 1 | 3 | 6 | 0 |

Among patients switching from warfarin to rivaroxaban, the frequency of bleeding was 13.2% (95% CI: 6.5%-22.9%) and 15.7% (95% CI: 8.6%-25.3%) for those starting anticoagulation with rivaroxaban. The frequency of bleeding was not statistically significantly different between the 2 different rivaroxaban initiation strategies used in this study. Across all patients on rivaroxaban, the frequency of major bleeding was 1.9%, while that of CRNMB was 11.9%, for a combined first major bleeding and/or CRNMB rate of 13.8%. This translates into a major bleeding incidence rate of 4.0 (95% CI, 1.0-10.9) per 100 patient-years of follow-up. The incidence rate for CRNMB was 29.5 (95% CI, 18.9-43.9) per 100 patient-years of follow-up.

As outlined in Table 4, all but 4 of the bleeds were classified as CRNMB according to the ISTH classification system and ≤ type 2 bleed on the BARC scoring system.

Table 4.

Assessment of Bleeding Severity.

| Total no. of Patients Experiencing Bleeds | Total no. of Episodes | BARC Bleeding Categorization Type | ISTH Bleeding Classification | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3a or 3b | 4 | 5a or 5b | Fatal Bleeding | Major Bleeding | Clinically Relevant Non-Major Bleed | Non-clinically Relevant Minor Bleed | |||

| New to rivaroxaban | 13 | 25 | 1 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 1 |

| Warfarin to rivaroxaban switch | 10 | 21 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 0 |

Most of the documented bleeds involved vaginal bleeding/heavy menses. As shown in Table 3, the CRNMB were resolved by modifying the dose, temporarily or permanently discontinuing rivaroxaban, or continuing treatment. The major bleeds involved the urinary tract for 2 patients, and the gastrointestinal tract for 1 as seen in Table 5. None of these bleeding events were fatal or resulted in hospitalization. Patients with major bleeds were able to permanently discontinue treatment with rivaroxaban without any further complications or sequelae.

Table 5.

Summary of Bleeding Events by Location.

| Bleeding Location | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaginal Bleeding/Heavy Menses | Lower Limb Ulcer Bleeding | Hemoptysis | Gum Bleed | GI Bleed | Hematuria | Hematochezia | Epistaxis | |

| New to rivaroxaban | 9 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Switch from warfarin to rivaroxaban | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

Just over half of the patients who suffered a bleeding event (12 of 23; 52.2%) had a known risk factor for bleeding 31 ; see Table 6.

Table 6.

Distribution of Risk Factors for Bleeding Among Patients With Rivaroxaban Bleeding Adverse Events.

| New on Rivaroxaban (Number with Bleed) | Switch From Warfarin to Rivaroxaban (Number with Bleed) | Total (Number with Bleed) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factors for bleeding | Hypertension | 14 (1) | 10 (1) | 24 (2) |

| Abnormal liver function | a | a | a | |

| Abnormal kidney function | a | a | a | |

| Stroke | 1 (0) | 5 (1) | 6 (1) | |

| Bleeding diathesis/predisposition | a | a | a | |

| Labile INR | Not applicable | a | a | |

| Elderly (age>65 years) | 14 (2) | 19 (4) | 33 (6) | |

| Drugs/alcohol | 3 (0) | 5 (1) | 0 | |

| Diabetes | 3 (0) | 5 (1) | 8 (1) | |

| Malignancy | 15 (2) | 6 (0) | 21 (2) |

Could not be assessed due to missing data; () Denotes number of patients with the risk factor who experienced a bleeding event.

The analysis of potential associations between the increased risk of bleeding and patient characteristics illustrated that having the Kenyan Government's National Hospital Insurance Fund (NHIF) was the only factor that was associated with a lower risk of bleeding, while being unemployed was the only factor that was associated with a higher risk of bleeding. These were the only statistically significant associations in both the adjusted and unadjusted analysis as seen in Table 7.

Table 7.

Associations with Rivaroxaban Bleeding Adverse Events Based on Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics.

| Bleeding Risk Coefficient | 95% CI | P-Value | Adjusted Coefficient | P-Value for Adjusted Risk | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Switch from warfarin | −0.19 | −1.10-0.70 | .68 | ||

| Female gender | 0.67 | −0.47-1.81 | .25 | ||

| Age ≥60 years | −0.01 | −0.97-0.95 | .98 | ||

| Currently married | −0.15 | −1.08-0.78 | .75 | ||

| Pulmonary embolus | 0.38 | −0.72-1.47 | .50 | ||

| Comorbid cancer | −0.67 | −1.38-1.23 | .91 | ||

| Comorbid cardiovascular disease | −0.71 | −1.99-0.56 | .28 | ||

| Distance from clinic ≥100 km | |||||

| 0.47 | −0.73-1.67 | .45 | |||

| Transport costs ≥2000 | −.09 | −1.65-1.46 | .91 | ||

| No formal education | 0.36 | −0.98-1.67 | .60 | ||

| Baseline INR ≥3.5 | 1.13 | −0.41-2.68 | .15 | ||

| Unemployed | 2.04 | 0.55-3.53 | .01 | 1.99 (0.47-3.5) | .01* |

| Enrolled in NHIF | −1.68 | −2.63-−0.75 | .01 | −1.63 (−2.60-−0.66) | .01* |

*P-value for significance: ≤.05.

Discussion

In routine care in the public sector, 14.4% of Kenyan patients with VTE starting anticoagulation with rivaroxaban, or switching from warfarin, experienced a bleeding event. Most of these were clinically relevant non-major bleeds (19 of 23; 82.6%). Compared with a previously published study from the same clinic, prior to the availability of rivaroxaban, the frequency of any bleeding among patients with VTE was significantly higher, 30.3% (95% CI, 22.0%-38.5%; P<.05) 32 than the rivaroxaban cohort analyzed here. Furthermore, the frequency of any bleeding event observed in the present study is similar to that reported in other observational studies completed in other populations (see Table 1).

Higher rates of first major bleed and/or CRNMB were observed in this study compared with landmark trials, such as EINSTEIN-DVT 8 (13.8% vs 8.1%, P<.01). The higher bleeding rates observed in this study relative to those observed in the landmark EINSTEIN studies could be attributable to the small size of the current study, less frequent follow-up, and pharmacogenomic differences in the study populations (majority of the participants in the EINSTEIN trials were Caucasian patients from high-income countries), as well as the non-randomized nature of the present study.33,34

The population from which the study participants were drawn is characterized by a relatively high prevalence of comorbidities associated with an increased risk of bleeding, specifically, hypertension and chronic kidney disease (CKD). Africa has the highest prevalence of hypertension in the world, estimated at 46% of the population above 25 years old, 35 against a global prevalence of 32% in women and 34% in men. 36 The prevalence of CKD in Africa is estimated at 15.8%, 37 against a global, age-adjusted prevalence of 10.4% in men and 11.8% in women. 38 In Kenya, the prevalence of hypertension and CKD is estimated at 34.7% and 14.4%, respectively. 37 Of concern is the fact that only about 49% of patients in Kenya are aware that they are hypertensive, and a dismal 7.7% of hypertensive patients are currently controlled on therapy. 36 The synergy of these risk factors, in combination with others not identified in the course of the study, may partly explain the high incidence of bleeding events.

In the rivaroxaban arm of the INVICTUS trial (which enrolled patients from low-income countries, albeit with a different indication for anticoagulation), the cumulative frequency of major and/or CRNMB was 4.5%. 28 The frequency of major bleeding was 1.8%, similar to that seen in the present study. The frequency of CRNMB was much lower, however, at 2.9% compared with that seen in our cohort at 13.8%. The lower frequency of CRNMB might be attributed to the larger study size of the INVICTUS trial, as well as the lower intensity of anticoagulation, at least for the first 3 weeks. In addition, the dose of rivaroxaban in the INVICTUS trial was adjusted based on renal function. In the present study, the lack of information regarding renal function precluded such dosage adjustments and reflects the real-world challenges with managing VTE in low-resource settings.

The elevated risk of bleeding is of even greater concern in settings like MTRH, as reversal agents, such as andexanet-alfa, are not available in Kenya. Reversal is therefore much more challenging than with more commonly used anticoagulant medications such as warfarin and heparin. Fortunately, the prompt follow-up and phone-based support provided by the anticoagulation clinic at MTRH helped prevent the clinical sequelae that patients may have experienced with continued use of rivaroxaban in the presence of a minor bleed. As access to DOACs continues to increase in LMIC settings, it is important that clinics establish infrastructure to quickly respond to any bleeding complications, regardless of severity, which may arise through routine use. 32

The observation of the decreased risk of bleeding among those with NHIF could be potentially explained by non-specific advantages that patients in a higher socioeconomic group experience when managing their health care needs. This finding is consistent with our finding that unemployed populations experienced a higher risk of bleeding. This is consistent with several studies reporting an association between lower socioeconomic status and a higher bleeding risk among patients on anticoagulation for various indications (VTE39,40; mechanical heart valves 41 ; atrial fibrillation 42 ). In Kenya, all formally employed citizens and their families are automatically enrolled into NHIF, whereas unemployed and informally employed individuals must pay a monthly fee to retain NHIF coverage. These findings highlight the importance of conducting real-world studies to identify trends that may compromise the care of certain populations. Based on these findings, we are increasing our efforts to provide more proactive phone-based follow-up for patients without insurance and lower socioeconomic status groups to improve our ability to more promptly identify clinically relevant bleeds across our entire population.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of this study is that this represents 1 of the first studies looking at the real-world use of rivaroxaban among patients of Kenyan descent with VTE and provides estimations of the risk of bleeding when used in commonly encountered clinical scenarios. As seen with numerous medications, including those used for anticoagulation, considerable pharmacogenomic variability between different races and ethnicities can impact the efficacy and toxicity of medications. While the higher bleeding risk observed in this study compared with findings from randomized controlled trials needs to be confirmed in larger scale post-marketing studies, it highlights the importance of increasing the inclusion of understudied populations in future assessments.

Despite these strengths, the study had several key limitations. The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic caused significant disruptions to routine care at the clinic. This resulted in a slower than expected accrual of patients into the study and more sporadic follow-up as patients were encouraged to minimize clinical visits. Information regarding the patient's organ function (hepatic and renal) was not available at recruitment as these tests were not routinely performed unless symptomatic renal or liver dysfunction was observed. In addition, the additional cost of these investigations constitutes a significant barrier to many patients in a resource-limited setting. This omission may have led to some patients being on higher doses of rivaroxaban than recommended for their baseline organ function and subsequently, increasing their bleeding risk while on treatment. The lack of sufficient information on the presence of validated risk factors for anticoagulant-associated bleeding precluded an analysis of what role these risk factors play with regard to the bleeding risk in our population. While adherence was not formally assessed, drug refill patterns suggested high levels of adherence. Several patients transitioning from warfarin to rivaroxaban had supra-therapeutic INRs at the baseline clinic visit, potentially impacting their subsequent bleeding risk. However, the timing of bleeding events in this sub-group did not seem to suggest that this impacted the bleeding risk. Owing to the observational nature of the present study, there is potential for under-reporting and/or selective reporting of events, resulting in an under- or over-estimation of the outcomes of interest. The evaluation of patients for inherited and acquired risk factors for VTE was not exhaustive, mainly due to the inability to afford the required investigations.

Conclusion

The results from our observational investigation merit additional investigation of the use of DOACs in Kenyan populations to confirm the findings of elevated bleeding risk compared with those found in large-scale trials comprised primarily of Caucasian populations.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-cat-10.1177_10760296231184216 for Risk of Bleeding Associated With Outpatient Use of Rivaroxaban in VTE Management at a National Referral Hospital in Western Kenya by Dennis Njuguna, BPharm, Francis Nwaneri, MD, Allyson C. Prichard, PharmD, Imran Manji, BPharm, MPH, Gabriel Kigen, BPharm, MPhil, PhD, Naftali Busakhala, MBChB, MMed, Samuel Nyanje,BSc, Emily O'Neil, PharmD and Sonak D. Pastakia, PharmD, MPH, PhD in Clinical and Applied Thrombosis/Hemostasis

Abbreviations

- DALY

disability-adjusted life year

- DVT

deep venous thrombosis

- DOACs

direct oral anticoagulants

- LMIC

low- and middle-income countries

- NSAIDs

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- PE

pulmonary embolism

- VKA

vitamin K antagonist

- VTE

venous thromboembolism.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The clinic obtained discounted rivaroxaban (Xarelto®) from Bayer East Africa Limited as part of the Rivaroxaban Access Program. There was no contribution (financial or otherwise) from the company in terms of data collection, manuscript writing, and submission.

ORCID iD: Dennis Njuguna https://orcid.org/0009-0007-3046-1202

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Raskob GE, Angchaisuksiri P, Blanco AN, et al. Thrombosis: A Major Contributor to Global Disease Burden. Published online 2014:2363-2371. doi: 10.1111/jth.12698.This. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Jha AK, Larizgoitia I, Audera-Lopez C, Prasopa-Plaizier N, Waters H, Bates DW. The global burden of unsafe medical care: analytic modelling of observational studies. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(10):809-815. doi: 10.1136/BMJQS-2012-001748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nordstrom BL, Evans MA, Murphy BR, Nutescu EA, Schein JR, Bookhart BK. Risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism among deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism patients treated with warfarin. Curr Med Res Opin. 2015;31(3):439-447. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2014.998814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klok FA, Kooiman J, Huisman M V, Konstantinides S, Lankeit M. Predicting anticoagulant-related bleeding in patients with venous thromboembolism: a clinically oriented review. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(1):201-210. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00040714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Linkins LA, Choi PT, Douketis JD. Clinical impact of bleeding in patients taking oral anticoagulant therapy for venous thromboembolism. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(11):893. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-11-200312020-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schulman S, Kearon C, Kakkar AK, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(24):2342-2352. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agnelli G, Buller HR, Cohen A, et al. Oral apixaban for the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(9):799-808. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bauersachs R, Berkowitz SD, Brenner B, et al. Oral rivaroxaban for symptomatic venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(26):2499-2510. doi: 10.1056/NEJMOA1007903/SUPPL_FILE/NEJMOA1007903_DISCLOSURES.PDF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Büller HR, Prins MH, Lensing AWA, et al. Oral rivaroxaban for the treatment of symptomatic pulmonary embolism. Cardiol Rev. 2012;28(3):1287-1297. doi: 10.1056/NEJMOA1113572/SUPPL_FILE/NEJMOA1113572_DISCLOSURES.PDF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van der Hulle T, Kooiman J, den Exter PL, Dekkers OM, Klok FA, Huisman MV. Effectiveness and safety of novel oral anticoagulants as compared with vitamin K antagonists in the treatment of acute symptomatic venous thromboembolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12(3):320-328. doi: 10.1111/jth.12485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Es N, Coppens M, Schulman S, Middeldorp S, Büller HR. Direct oral anticoagulants compared with vitamin K antagonists for acute venous thromboembolism: evidence from phase 3 trials. Blood. 2014;124(12):1968-1975. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-04-571232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ingason AB, Hreinsson JP, Ágústsson AS, et al. Rivaroxaban is associated with higher rates of gastrointestinal bleeding than other direct oral anticoagulants. 2021;174(11):1493-1502. doi: 10.7326/M21-1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Radadiya D, Devani K, Brahmbhatt B, Reddy C. Major gastrointestinal bleeding risk with direct oral anticoagulants: does type and dose matter? - a systematic review and network meta-analysis. . Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;33(1S Suppl 1):E50-E58. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000002035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stevens SM, Woller SC, Kreuziger LB, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: second update of the CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2021;160(6):e545-e608. doi: 10.1016/J.CHEST.2021.07.055/ATTACHMENT/60F8BB3C-A059-42FA-8B95-6DC6A6BEF07D/MMC1.MP3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chai-Adisaksopha C, Crowther M, Isayama T, Lim W. The impact of bleeding complications in patients receiving target-specific oral anticoagulants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood. 2014;124(15):2450-2458. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-07-590323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirkilesis GI, Kakkos SK, Tsolakis IA. Editor’s choice – a systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of anticoagulation in the treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2019;57(5):685-701. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2018.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolfe Z, Khan SU, Nasir F, Raghu Subramanian C, Lash B. A systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis of risk of intracranial hemorrhage with direct oral anticoagulants. J Thromb Haemost. 2018;16(7):1296-1306. doi: 10.1111/JTH.14131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Büller HR, Décousus H, Grosso MAet al. Edoxaban versus warfarin for the treatment of symptomatic venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(15):1406-1415. doi: 10.1056/NEJMOA1306638/SUPPL_FILE/NEJMOA1306638_DISCLOSURES.PDF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ageno W, Mantovani LG, Haas S, et al. Safety and effectiveness of oral rivaroxaban versus standard anticoagulation for the treatment of symptomatic deep-vein thrombosis (XALIA): an international, prospective, non-interventional study. Lancet Haematol. 2016;3(1):e12-e21. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(15)00257-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kreutz R, Mantovani LG, Haas S, et al. XALIA-LEA: an observational study of venous thromboembolism treatment with rivaroxaban and standard anticoagulation in the Asia-Pacific, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, Africa and Latin America. Thromb Res. 2019;176:125-132. doi: 10.1016/J.THROMRES.2019.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haas S, Mantovani LG, Kreutz R, et al. Anticoagulant treatment for venous thromboembolism: a pooled analysis and additional results of the XALIA and XALIA-LEA noninterventional studies. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2021;5(3):426-438. doi: 10.1002/RTH2.12489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barco S, Schmidtmann I, Ageno W, et al. Early discharge and home treatment of patients with low-risk pulmonary embolism with the oral factor Xa inhibitor rivaroxaban: an international multicentre single-arm clinical trial. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(4):509-518. doi: 10.1093/EURHEARTJ/EHZ367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evans A, Davies M, Osborne V, Roy D, Shakir S. Evaluation of the incidence of bleeding in patients prescribed rivaroxaban for the treatment and prevention of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in UK secondary care: an observational cohort study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(11):e038102. doi: 10.1136/BMJOPEN-2020-038102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keller L, Marten S, Hecker J, Sahin K, Tittl L, Beyer-Westendorf J. Venous thromboembolism therapy with rivaroxaban in daily-care patients: results from the Dresden NOAC registry. Int J Cardiol. 2018;257:276-282. doi: 10.1016/J.IJCARD.2017.10.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bounameaux H, Haas S, Farjat AE, et al. Comparative effectiveness of oral anticoagulants in venous thromboembolism: GARFIELD-VTE. Thromb Res. 2020;191:103-112. doi: 10.1016/J.THROMRES.2020.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaertner S, Cordeanu EM, Nouri S, et al. Rivaroxaban versus standard anticoagulation for symptomatic venous thromboembolism (REMOTEV observational study): analysis of 6-month outcomes. Int J Cardiol. 2017;226:103-109. doi: 10.1016/J.IJCARD.2016.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Speed V, Patel JP, Cooper D, et al. Rivaroxaban in acute venous thromboembolism: UK prescribing experience. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2021;5(7):e12607. doi: 10.1002/RTH2.12607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Connolly SJ, Karthikeyan G, Ntsekhe M, et al. Rivaroxaban in Rheumatic Heart Disease–Associated Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2022. Published online September 15, 2022. doi: 10.1056/NEJMOA2209051/SUPPL_FILE/NEJMOA2209051_DATA-SHARING.PDF. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mehran R, Rao S V, Bhatt DL, et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials. Circulation. 2011;123(23):2736-2747. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.009449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaatz S, Ahmad D, Spyropoulos AC, Schulman S. Definition of clinically relevant non-major bleeding in studies of anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation and venous thromboembolic disease in non-surgical patients: communication from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(11):2119-2126. doi: 10.1111/JTH.13140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of chest physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e419S. doi: 10.1378/CHEST.11-2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manji I, Pastakia SD, Do AN, et al. Performance outcomes of a pharmacist-managed anticoagulation clinic in the rural, resource-constrained setting of Eldoret, Kenya. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(11):2215-2220. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang D, Qin W, Du W, Wang X, Chen W, Li P. Effect of ABCB1 gene variants on rivaroxaban pharmacokinetic and hemorrhage events occurring in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2022;43(4):163-171. doi: 10.1002/BDD.2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shnayder NA, Petrova MM, Shesternya PA, et al. Using pharmacogenetics of direct oral anticoagulants to predict changes in their pharmacokinetics and the risk of adverse drug reactions. Biomedicines. 2021;9(5), doi: 10.3390/BIOMEDICINES9050451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoruk A, Boulos PK, Bisognano JD. The state of hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa: review and commentary. Am J Hypertens. 2018;31(4):387-388. doi: 10.1093/AJH/HPX196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou B, Carrillo-Larco RM, Danaei G, et al. Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: a pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. Lancet. 2021;398(10304):957-980. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01330-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaze AD, Ilori T, Jaar BG, Echouffo-Tcheugui JB. Burden of chronic kidney disease on the African continent: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Nephrol. 2018;19(1):1-11. doi: 10.1186/S12882-018-0930-5/FIGURES/6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mills KT, Xu Y, Zhang W, et al. A systematic analysis of world-wide population-based data on the global burden of chronic kidney disease in 2010. Kidney Int. 2015;88(5):950. doi: 10.1038/KI.2015.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wadhera RK, Secemsky EA, Wang Y, Yeh RW, Goldhaber SZ. Association of socioeconomic disadvantage with mortality and readmissions among older adults hospitalized for pulmonary embolism in the United States. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(13), doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.021117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cohen AT, Sah J, Dhamane AD, et al. Effectiveness and safety of apixaban versus warfarin among older patients with venous thromboembolism with different demographics and socioeconomic status. Adv Ther. 2021;38(11):5519-5533. doi: 10.1007/s12325-021-01918-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dalén M, Persson M, Glaser N, Sartipy U. Socioeconomic status and risk of bleeding after mechanical aortic valve replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(25):2502-2513. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ravvaz K, Weissert JA, Jahangir A, Ruff CT. Evaluating the effects of socioeconomic status on stroke and bleeding risk scores and clinical events in patients on oral anticoagulant for new onset atrial fibrillation. PLoS One. 2021;16(3 March):1-13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-cat-10.1177_10760296231184216 for Risk of Bleeding Associated With Outpatient Use of Rivaroxaban in VTE Management at a National Referral Hospital in Western Kenya by Dennis Njuguna, BPharm, Francis Nwaneri, MD, Allyson C. Prichard, PharmD, Imran Manji, BPharm, MPH, Gabriel Kigen, BPharm, MPhil, PhD, Naftali Busakhala, MBChB, MMed, Samuel Nyanje,BSc, Emily O'Neil, PharmD and Sonak D. Pastakia, PharmD, MPH, PhD in Clinical and Applied Thrombosis/Hemostasis