Abstract

A 62-year-old woman with no systemic disease presented to the emergency department (ED) with acute febrile illness for three days. During her ED course, she developed respiratory distress and refractory cardiogenic shock with ST-elevation on electrocardiography. No occluded coronary vessel was found in angiography, and perimyocarditis was impressed. The serum indirect immunofluorescence assay was positive for scrub typhus. Hemopericardium and subsequently intracranial hemorrhage occurred on the 4th hospital day even under intensive care, and the patient expired. Perimyocarditis is a rare but fatal complication of scrub typhus. Through this case report, we aim to convey the genuine possibility that a fulminant perimyocarditis may occur in a previously healthy adult as a potential complication of scrub typhus. By recognizing the risk factors of scrub typhus-related myocarditis, an ED physician can maintain a high index of suspicion for the cardiac complication and intervene in a timely manner.

Keywords: cardiogenic shock, perimyocarditis, scrub typhus

Introduction

Scrub typhus is a zoonotic disease that is endemic in Asian-Pacific rims, including Taiwan. According to Taiwan Centers for Disease Control, about 400 people are diagnosed with scrub typhus annually. Among those that are treated, the vast majority are expected to recover without significant sequela. However, in a small number of healthy individuals, scrub typhus may prove to be fatal due to cardiac complications. As such, prompt recognition of the individuals at risk of poor outcomes may be life-saving. In this case review, we report a case of scrub typhus-related perimyocarditis documented by a positive Weil-Felix test with a brief review of literature.

Case Report

A 62-year-old Taiwanese woman with no systemic disease suffered from acute febrile illness for three days accompanied by nausea and dizziness. No symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection, headache, abdominal pain, dysuria, or joint pain were elicited. She had a body temperature of 39.7°C, pulse rate of 125 bpm, blood pressure of 135/84 mmHg, respiratory rate of 20 breaths/min, SpO2 of 94% on room air, and clear oriented mental status. Physical examination showed clear breath sounds, regular heart beat without murmur, and no abdominal tenderness. Skin inspection revealed lymph node swelling over right axilla and one 1.0 x 0.6 cm dark papule over erythematous base on right upper back (Figure 1). Travel history was notable for a trip to Orchid Island (Lan-Yu) about three weeks ago.

Figure 1. Photograph showing 1.0 x 0.6 cm eschar in the right axilla region.

Initial laboratory data revealed normal leukocyte count with marked bandemia (6,900/μL, 22%), lymphopenia (0.8%), thrombocytopenia (platelets, 43,000 μL), hyponatremia (121 mmol/L), abnormal liver enzymes (GOT/GPT: 216/94 U/L), coagulopathy (INR: 1.26), and elevated procalcitonin level (2.90 ng/dL). Her renal function was within normal range. Chest X-ray was unremarkable for significant lung consolidation (Figure 2A), and electrocardiography (ECG) showed sinus tachycardia (Figure 3A). Under clinical suspicion of scrub typhus, empirical treatment with oral doxycycline (100 mg twice daily) and intravenous ceftriaxone (2 g twice daily) were initiated immediately.

Figure 2A. Chest radiograph at the time of admission and six-hour later.

(A) The initial chest radiograph revealed mild bilateral pleural effusion.

Figure 3A. Electrocardiography at the time of admission and six-hour later.

(A) Initial electrocardiography revealed sinus tachycardia.

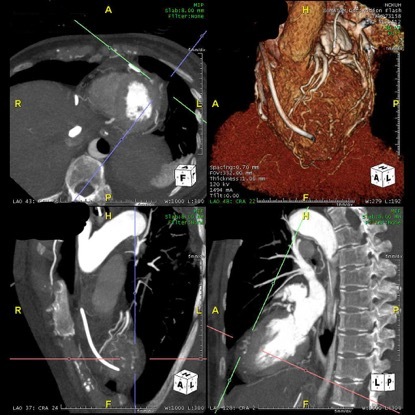

About six hours after initial treatment, hypotension with respiratory distress developed. Followed chest X-ray showed diffuse, bilateral pulmonary infiltrate (Figure 2B) and ECG revealed anterior leads ST-elevations (Figure 3B) with dynamic elevation of cardiac enzymes. Emergent coronary angiography, however, showed no occluded coronary vessels. Aortic computed tomography (CT) angiography showed sessile hypervascular epicardial ill-defined soft tissue at apical left ventricular, consistent with acute fulminant perimyocarditis (Figure 4). Perimyocarditis was favored as the primary etiology of cardiogenic shock. As a consequence of severe hemodynamic instability, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) and intraaortic balloon pump were placed.

Figure 2B. Chest radiograph at the time of admission and six-hour later.

(B) Second chest radiography of six hours later revealed bilateral enlarged hilar shadows with lung infiltrations and patchy densities.

Figure 3B. Electrocardiography at the time of admission and six-hour later.

(B) Second electrocardiography of six hours later revealed anterior ST-segment elevation.

Figure 4. The image of aortic computed tomography angiography revealed acute fulminant perimyocarditis with inflamed/infectious epicardial and hypervascular tissue overlying apical left ventricle.

The serum indirect immunofluorescence assay test showed negative immunoglobulin M (IgM) titer but IgG titer increased significantly from negative to positive (1:1280) in 3 days’ time. Weil-Felix agglutination testing of the patient’s pretreatment serum sample was positive for OXK antigen. The diagnosis of Scrub Typhus was strongly suspected due to the combination of travel history, the dermatologic finding of eschar, and positive Proteus OXK of Weil-Felix slide agglutination test.

On the 4th hospital day, the patient developed cardiac tamponade from a newly developed hemopericardium, and subsequently intracranial hemorrhage with uncal herniation. She expired on the 11th hospital day.

Discussion

Albeit rare, cardiovascular complications associated with scrub typhus may manifest as myocarditis, pericarditis, massive pericardial effusion, acute heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, and cardiogenic shock. Early in 1997, electrocardiographic studies described diverse and non-specific ECG changes in scrub typhus patients.[1] More recently, it has been reported that those with relative bradycardia, ST-segment elevation, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (PAF), and an elevated total bilirubin were at increased risk of scrub typhus-related acute myocarditis.[2,3] Acute fulminant myocarditis may result in severe cardiogenic shock, leading to fatalities.[4] In addition, Karthik et al.[5] reported that myocarditis with a shorter duration of symptoms prior to presentation was associated with prolonged hospitalization, higher quick sequential organ failure assessment scores, and severe disease.

To our knowledge, this is one of the very few cases of scrubs typhus-related perimyocarditis that resulted in severe cardiogenic shock requiring ECMO support. In general, pericarditis is usually diagnosed clinically based on two of the following four criteria: chest pain, pericardial rubs, ECG changes, or pericardial effusion. Evidence of inflammation in imaging and an increase in inflammatory markers supported the finding. In this case, Based on ECG finding (anterior lead ST-elevation) and CT angiography finding (hypervascular epicardial region), pericarditis is highly suspected in this case. In light of the clinical presentation, perimyocarditis was favored. Scrub typhus-related perimyocarditis may be elusive to diagnose due to its non-specific presentation. However, prompt recognition of risk factors associated with poor prognosis including an advanced age, hypoalbuminemia, thrombocytopenia, acute kidney injury, hyperbilirubinemia, and liver impairment serve to guide risk-stratification and prompt management (Table 1). [3,4] Indeed, these were the risk factors this patient exhibited in the course of her illness.

Table 1. Risk factors associated with myocarditis and poor prognosis.

CRP: C-reactive protein.

| Risk factors for myocarditis |

Relative bradycardia ST-segment elevation Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation Elevated total bilirubin Shorter duration of symptom prior to presentation |

| Risk factors for poor prognosis |

Advanced age Liver impairment Hyperbilirubinemia Acute kidney injury Hypoalbuminemia Thrombocytopenia Elevated CRP Delayed antibiotic |

Contrary to the current understanding of scrub typhus as a self-limited infectious disease, the presented case hereby illustrates a previously healthy individual who developed life-threatening cardiovascular complications along with rapid hemodynamic decompensation despite timely antibiotic administration. As mentioned, there are clues that aid in categorizing the severity of scrub typhus infection. As such, physicians should be vigilant of the characteristics that render a patient at increased risk of severe disease, as early recognition translates to early mobilization of resources, monitoring, and hopefully an improved outcome.

References

- Chin Jung Yeon, Kang Ki-Woon, Moon Kyung Min, Kim Jongwoo, Choi Yu Jeong. Predictors of acute myocarditis in complicated scrub typhus: an endemic province in the Republic of Korea. The Korean Journal of Internal Medicine. 2018 Mar 01;33(2) doi: 10.3904/kjim.2016.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim HK, Wang JM. Scrub Typhus: Seven-Year Experience and Literature Review. Journal of Acute Medicine. 2018 Sep 01;8(3) doi: 10.6705/j.jacme.201809_8(3).0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karthik Gunasekaran, Sudarsan Thomas Isaiah, Peter John Victor, Sudarsanam Thambu, Varghese George M, Kundavaram Paul, Sathyendra Sowmya, Iyyadurai Ramya, Pichamuthu Kishore. Spectrum of cardiac manifestations and its relationship to outcomes in patients admitted with scrub typhus infection. World Journal of Critical Care Medicine. 2018 Feb 04;7(1) doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v7.i1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang CY, Dennis DT, Lee JB. Electrocardiographic changes in scrub typhus patients. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1977;8:503–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronoff DM, Watt G. Prevalence of relative bradycardia in Orientia tsutsugamushi infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;68:477–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]