Abstract

In Alabama, despite the high screening rates for cervical cancer in Blacks, they still have higher mortality rates compared to Whites. Our objective was to increase knowledge and awareness of cervical cancer with the intention to encourage more women to have Pap tests, Human Papillomavirus (HPV) tests and HPV vaccinations after a short-term educational-based intervention. Pre and post questionnaires were administered to collect data before and after a primary educational intervention in Macon County was taught by a team of experts in the subject area. Descriptive statistics were done using SAS software to generate frequency and chi-square tests. Out of the 100 participants: 9% had cervical cancer; 86% were Blacks; about 65% were over the age of 35 and earned less than $50,000/year; 62% lived in the Tuskegee community; 34% were students, staff or faculty of Tuskegee University; about 25% were either married or living with their partner; leaving about 75% of the women as single, divorced or widowed; and more than 80% were students between their first year of college and graduate school with only 40% working for pay. The short-term educational intervention increased participants’ knowledge of: who knew what cervical cancer was; ever heard of HPV; and ever had an HPV-test by margins of 9%, 23% and 4% respectively. Participants who had ever heard of Pap test had the same knowledge of 97% before and after the intervention. There was a significant knowledge level increased: in understanding that cervical cancer was caused by 38% HPV infection; 39% of all HPV infections lead to cervical cancer; and cervical cancer has decreased in recent years by 50%. Significant differences were observed only among participants who had ever heard of Pap test before and after the educational intervention with p-values of 0.004 and 0.03 respectively, compared to participants who knew what cervical cancer was and who had ever heard of HPV test. Although some participants lacked knowledge in certain areas, this study showed an apparent increase in their knowledge and awareness following the educational intervention.

Keywords: Human Papilloma Virus (HPV), cervical cancer, Pap test/Pap smear, HPV test, knowledge, awareness

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the fourth most frequent cancer in women with an estimated 570,000 new cases in 2018 representing 6.6% of all female cancers (WHO | Cervical cancer, n.d.). Nearly 13,000 women in the US are diagnosed with cervical cancer each year. However, cervical cancer is the most prevalent cancer among women in the state of Alabama compared to any other state in the United States (Cervical Health Awareness Month—NCCC : NCCC, n.d.). Ironically, although Alabama possesses the highest rates of cervical cancer nationwide, the state also has the highest rates for cervical cancer screenings (Alabama has highest rate of cervical cancer death in nation, says report—Al.com, n.d.-a). The cervical cancer mortality rate in Alabama is 3.2 - significantly higher than the US rate of 2.3. Black females in the state have a significantly higher cervical cancer mortality rate than white females, with a rate of 5.2 versus 2.7 (Cancer Facts & Figures 2017.pdf, n.d.).

Cervical cancer is a malignant tumor that grows in the lower portion of a woman’s cervix. All women are at risk of being diagnosed with cervical cancer (Basic Information About Cervical Cancer | CDC, 2019). It is imperative that women are aware of the Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccinations and its ability to prevent cervical cancer, if coupled with suitable screenings. Human Papillomavirus is the most common sexually transmitted infection with which a majority of individuals, in their late teens or early 20s, will be infected (STD Facts—Human papillomavirus (HPV), 2019). Some types of HPV vaccines can cause health complications leading to cervical cancer. However, HPV vaccines and screenings can prevent complications or prolong health (STD Facts—Human papillomavirus (HPV), 2019). The most commonly used HPV vaccine is Gardasil 9, which protects against types 6, 11, 16, and 18. This vaccine is typically administered at ages of 11–12 (HPV Vaccine | What Is the HPV Vaccination, n.d.). Another type of HPV vaccine is Cervarix, which protects against only types 16 and 18 (Saqer et al., 2017).

The suitable screenings for cervical cancer prevention are Pap smear/Pap test, as well as HPV test. The Pap test, also known as the Papanicolaou test or cervical cytology, is conducted by gently scraping cells from the cervix and analyzing them for abnormalities that could possibly be precancerous or cancerous (Gynecologic Cancers | CDC, 2020). The objective of the HPV test is relatively similar to a Pap test in its aim to analyze the cells of the cervix. However, instead of analyzing cells for abnormalities, they are analyzed for the HPV virus. The HPV test has a higher accuracy level because it detects the actual DNA of the virus (Burd, 2016). Although women in Alabama are receiving the proper screenings to prevent cervical cancer, those residing in the more rural communities are at a higher risk of cervical cancer (Yu, 2019).

Women residing in rural communities who are in a low socioeconomic class may encounter barriers that interfere with their access to quality health care. These barriers prohibit their access to optimal cervical cancer prevention, early detection, and even treatment (Yu, 2019). Despite high screening rates for cervical cancer among all races in Alabama, Blacks still have higher mortality rates compared to Whites (Abdalla, 2016). According to a report by Human Rights Watch, Alabama has the highest rate of cervical cancer deaths in the country. Black women in Alabama are dying of a preventable disease at a rate twice as high as the nation’s (Avenue et al., 2019). This gap could be due to a variety of health disparities that exist within communities, including access to correct knowledge pertaining to prevention and treatment methods.

Research Question and Hypothesis

The research question was therefore: What effect does a short-term educational intervention on cervical cancer have on the level of knowledge and awareness of women residing in Macon County, Alabama?

We hypothesized that an increase in knowledge and awareness among the participants following the intervention will result in a higher likelihood of them being screened for cervical cancer. We also hypothesized that the less knowledge women have regarding cervical cancer screening, the less likely they are to obtain cervical cancer screenings.

Research Goal

The main goal of this research was to increase knowledge and awareness about Cervical Cancer with the intention of encouraging community members to have a Pap test, HPV test, and HPV vaccination after the educational-based intervention.

Research Objective

The objective of this research was to increase the participants’ knowledge and willingness to participate in proper cervical cancer screenings and human papillomavirus vaccination programs, following the short-term educational-based intervention.

Cervical Cancer Trends in the US

Cervical Cancer is the fourth most common cancer affecting women worldwide (Cervical Health Awareness Month—NCCC : NCCC, n.d.). In the US, there was an estimated 12,200 new cases of cervical cancer in 2010 (Alabama has highest rate of cervical cancer death in nation, says report—Al.com, n.d.-b). However, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention in 2016, which is the latest year with recorded incidence data, nearly 13,000 new cases were reported, and nearly 4,200 women died of cervical cancer in the U.S. For every 100,000 women, there are 8 women diagnosed with cervical cancer and 2 women who die of cervical cancer (Basic Information About Cervical Cancer | CDC, 2019). The American Cancer Society hypothesizes that for the year of 2020 there will be nearly 14,000 newly diagnosed cases in the United States resulting in approximately 4,300 mortalities.

Adegoke et al. (2012) analyzed the trends of invasive cervical cancer incidence by age, histology, and race over a 35-year period from 1973–2007. They collected useful information from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results cancer registries, also referred to as SEER. This data included demographic characteristics, diagnosis date, follow-up of vital status, and the cause of death (if applicable). This evaluation did not include any women under the age of 20 and race was confined to only Black and White women. The results of this study showed that the incidence of invasive cervical cancer was higher between the ages of 45–49 years old. However, over the 35-year period, age-adjusted incidents rates for all invasive cervical cancer decreased by 54% from 1973 to 2007.

Based on the previous findings, the age-adjusted incidence rates for Black women decreased by 72% compared to the age-adjusted incidence rates for White women, which decreased 54%. Although rates for Black women have shown a greater decrease than for White women, the incidence of cervical cancer remains higher in Black women compared to their White counterparts. These disparities could be due to the geographic distribution of minority groups in the US, leaving mortality rates higher in rural areas and lower in urban areas. Though it has not been demonstrated clearly, it could reflect less access to care and poorer outcomes (Excess Cervical Cancer Mortality: A Marker for Low Access to Health Care in Poor Communities, n.d.). Ito et al. suggests that the utilization of community-based interventions could provide a strategy for reaching individuals in the community who are not necessarily accessing the health care system. Previous studies, also suggest that if further research was conducted on behavior, such community-based interventions could be utilized as a tool for increasing HPV vaccinations and cervical cancer screenings (Ito et al., 2014).

Based on statistics from the American Cancer Society, in the US, Hispanic women are most likely to get cervical cancer, followed by African-Americans, American Indians and Alaskan natives, and Whites (Cervical Cancer Statistics | Key Facts About Cervical Cancer, n.d.). Asians and Pacific Islanders have the lowest risk of cervical cancer in this country (Cervical Cancer Statistics | Key Facts About Cervical Cancer, n.d.). Gopalani et al (2018) assessed the incidence and mortality trends in Oklahoma and compared t to those of the US between the years of 1999 and 2013. The data for this study was obtained from the Oklahoma Central Cancer Registry, which is a population-based cancer registry that possesses data pertaining to all reported cases in Oklahoma since 1997. The findings suggested that cervical cancer incidence was highest among women of minority races in Oklahoma, which was nearly double that of the nation’s (Gopalani et al., 2018). This could be due to various factors, including but not limited to, low cervical cancer screening rates, poor health literacy, lack of access to health insurance and care, and many socioeconomic factors (Flores & Bencomo, 2009). In the last 15 years, the cervical cancer mortality rate in Oklahoma had only begun to stabilize, in contrast to the U.S. trend of mortality rates, which earlier began to decrease (Cancer of the Cervix Uteri—Cancer Stat Facts, n.d.). This study suggests that the alarming rates of cervical cancer should be addressed using evidence-based strategies to increase access to screenings and follow-up care (Wong & Miller, 2019).

Racial Disparities in Cervical Cancer

Although cervical cancer can be prevented with the proper screenings and vaccinations, there are still women of different races that are being negatively impacted by this disease. Beavis et al. (2017) showed that black women died at an age-adjusted rate that was almost twice as high as white women. This is a representation of how women of minority races are disproportionately affected by this preventable disease. Scarinci et al (2010) emphasized the fact that more than 60% of cervical cancer diagnoses occur in small pockets of underserved, under screened, populations of women.

Fleming et al. (2014) conducted a study in Maryland to determine treatment factors used to evaluate outcome differences between races. Maryland, similar to the US as a whole, has seen an overall decreased incidence in cervical cancer in both White and Black patients for decades. However, cervical cancer mortality increased between 2003 and 2007 amongst Black women at a rate of 2.8% per year, whereas it decreased amongst White women at a rate of 0.1% per year (Fleming et al., 2014). The findings of Abdalla et al. show that in Alabama cervical cancer screening percentages of Blacks were higher than those of Whites (Abdalla, 2016), however Blacks in Alabama also had a higher cervical cancer mortality rate than Whites (AlabamaFactsfigures2012.pdf, n.d.).

Intervention Methods to Improve Cervical Cancer Screenings and Rates

Previous research from Scarinci et al. (2010) noted that effective interventions are not comprised of just vaccinations and screening clinics, but are influenced by establishing a relationship with the affected community. This relationship will open up opportunities to build trust between stakeholders and community members while also breaking down barriers related to fears. Sagar et al. (2017) conducted an intervention in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates with aims to assess the knowledge and attitudes of parents towards HPV and whether or not they would be willing to vaccinate their daughters. The researchers utilized a self-administered questionnaire, which was divided into five categories:

Demographics (age, nationality, level of education including spouse’s)

Cervical Cancer knowledge

HPV knowledge

HPV Vaccine Knowledge, and

Participants’ attitudes and willingness towards being vaccinated or vaccinating daughters

The findings of that previous study suggested that although the participants lacked knowledge regarding cervical cancer screenings, the parents’ willingness to vaccinate their daughters had a significant increase. It was also concluded that the Sharjah public uses media as their primary source of information. This gives stakeholders and decision-makers lead-way on how to effectively approach the community. With the United Arab Emirates possessing a conservative culture, researchers were also able to conclude that having males be a part of the intervention could impose some discomfort to mothers, due to the sensitivity of the topic. Although men are not at risk for cervical cancer, they are however at risk for HPV which can lead to throat, penile, and anal cancer. (STD Facts—HPV and Men, 2019).

Dutta et al. (2018) assessed individual and intimate partner factors associated with cervical cancer screening in Kenya. Researchers conducted a secondary analysis on questionnaire responses pertaining to cervical cancer screening and domestic violence in the Kenya Demographic and Health Survey, 2014. They examined the association of cervical cancer screening with age, religion, education, wealth, recent exposure to family planning on television, head of household’s sex, and any experience of intimate partner violence. The findings of that study showed an increase, with each new level of education attainment, in the participants having heard of cervical cancer. That study also found a relationship between religion and cervical cancer screening. Similar studies in Nigeria suggest that cervical cancer screenings do not adhere to their cultural beliefs, which consider any talk about sexuality to be prohibited. The researchers of the Nigerian study were able to distinguish between issues that needed to be addressed in order to improve cervical cancer screening rates through effective intervention methods.

Ito et al. (2014) examined the effectiveness of an intervention by increasing knowledge about human papillomavirus and cervical cancer in middle school-girls while increasing the intention to have cervical cancer screenings in their mothers. The researchers utilized a pre and post questionnaire design during an intervention for 7th graders and their mothers at three rural middle schools. The intervention consisted of two components. One to be completed during school and one to be completed at home with their mothers. The intervention was created to address the following subject matters:

The high prevalence and incidence of cervical cancer among young women

The fact that cervical cancer is preventable

How to prevent cervical cancer

The results of that study showed an increase in the students and mothers’ knowledge following the intervention. The findings also suggested that there might be underlying factors besides the mothers’ knowledge that are affecting their willingness to be screened due to the fact that mothers had high knowledge scores but still failed to be in compliance with screenings. Researchers were able to conclude from the study that intervention methods need to be effective for all participants. For example, the content needs to be able to effectively improve the student’s knowledge while also being adequate for the educational needs of the mothers. The study illustrated the importance of having follow-up surveys after an educational-based intervention to ensure that the knowledge given is successfully being converted to more health improving behaviors.

Materials and Methods

Study Design, Setting, Data collection and Participants

A short-term educational based intervention was conducted utilizing a pre and post questionnaire design. The study setting took place in Macon County in the rural Black Belt Counties of Alabama in September 20, 2018. Participants included were females 18 years and older from this county. All female participants were eligible for inclusion; there were no exclusion criteria for females. Before initiating any components of the study, it was required to obtain approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) whose goal is to protect the rights and welfare of human research subjects that have been recruited to be a part of any research components. After obtaining approval from the IRB, we began campaigning throughout the community at different locations and events (All Macon County Celebration Day, International Southern Christian Leadership Foundation (SCL), Tuskegee Police Department, Neighborhood Watch meetings, Board of Education meetings, Housing Authority, churches, etc.) to recruit participants into the intervention from Macon County. The campaigning process of the study took place between August 23 and September 19, 2018 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study Design of Assessment of the Awareness of Cervical Cancer among Women Living in Macon County, Alabama.

Procedure to collect the comprehensive multifactorial epidemiologic data

We developed a Comprehensive Health Survey Questionnaire, defined the study population and determined an appropriate sample size of 100 women 18 years and older to carry out a baseline survey in Macon County in the rural Black Belt Counties of Alabama. This survey was developed using questions from previously published surveys (McGhee et al., 2017). Informed consent was obtained from adult women 18 years and older prior to participating in the study voluntarily and anonymously to ensure privacy and confidentiality of all information collected from the community. Participants also completed six demographic questions on race, age, marital status, employment, education and annual income, which were administered pre-intervention questionnaire only. The pre-intervention questionnaires were administered before educational sessions. The post-intervention questionnaires were distributed after educational sessions taken by the participants, and they were collected after these sessions. The pre- questionnaire consisted of four modules, comprised of 39 yes/no and multiple-choice questions and the post- questionnaire consisted of three modules, comprised of 33 yes/no and multiple-choice questions. Each questionnaire took 15 minutes to be completed by participants. The modules covered the following: demographic and socio-economic information; participant’s family history and knowledge about cervical cancer; participant’s medical history and knowledge about HPV vaccine and cervical cancer. The survey questionnaires were administered during the workshop conducted in Tuskegee University, which is located in Macon County, Alabama. Specific investigators trained to conduct studies with human subjects from Tuskegee University (including faculty, staff and graduate students), leaders from collaborating community organizations and community groups (e.g., Macon Mean for Cancer Support Group) helped in administering the survey instrument questionnaires, especially with the participants who had reading and/or writing disabilities. Each participant received a variety of cervical cancer awareness products upon completion of the pre and post questionnaires as a token of appreciation.

Inclusion of Women, Minorities, and Children

One hundred female participants 18 years and older living in Macon county in the rural Black Belt Counties of Alabama were recruited for this study. This study exclusively focused on women over the age of 18 years. This study was also conducted exclusively in this targeted population because evidence suggests that in Alabama, women die at an annual rate of 3.9/100,000 (Cervical Health Awareness Month—NCCC : NCCC, n.d.), however, vast racial health disparities skew the picture. Blacks die at nearly double the rate of Whites, (5.2/100,000 versus 2.7/100,000) [4]. Therefore, we have ensured that this population was appropriately represented in this study.

Recruitment and Retention Plan

We enrolled 100 female participants 18 years and older living in Macon county in the rural Black Belt Counties of Alabama. On August 23, 2018, the Tuskegee University Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the study protocol. Leaders from community organizations and community groups (e.g., Macon Means for Cancer Support Group) helped Tuskegee University specific investigators who were trained in Human Subjects to reach out to the participants 18 years and in Macon county and proposed recruitment and advertising materials. The informed consent was ascertained by women 18 years and older before being allowed to voluntarily and anonymously participated in the study to ensure privacy and confidentiality of all information collected from the community. Participants were also recruited by attending the following events: All Macon County Celebration Day, International Southern Christian Leadership Foundation, Tuskegee Police Department, Neighborhood Watch meetings, Board of Education meetings, Housing Authority, churches, etc. The IRB reviewed not only the wording of advertising materials but also the presentation and the intended mode of communication (e.g., print, radio, television). The purpose of the IRB’s review is to ensure that no aspect of the advertising materials might be considered coercive or misleading.

Retention began during the workshop, while the participant was going through the informed consent process, we ensured that the participant understood the time and procedures involved and talk about why it is important to complete all the required study procedures. Locator forms were created to record a participant’s contact information. Using a locator form, Tuskegee University specific investigators recorded the participant’s address, phone number, and contact information for friends and family members who may be called, of course, with the consent of the participants. This information helped Tuskegee University specific investigators to locate and invite the participants after the workshop to share their finding based on the information regarding their knowledge and awareness about cervical cancer, HPV vaccination, and cervical cancer screening (Pap test and HPV test) were provided by participants. After the completion of the study including the statistical analysis, a power point presentation was prepared based on the information provided by the participants, one of the Tuskegee University specific investigator (Kellon Banks) reached out to the participants throughout the community at different locations and events and made multiples presentations.

Intervention

The intervention comprised a comprehensive education on cervical cancer and screening for cervical cancer. Women 18 years and older from Macon County, Alabama who voluntarily consented to participate in the study constituted the intervention group (Appendix H). The intervention included information on cervical cancer and screening for cervical cancer to increase the level of knowledge and awareness about the disease. The education on cervical cancer focused on the cause (HPV); predisposing factors; signs and symptoms; complications and methods of prevention. The benefits of cervical cancer screening and the perceived barriers to screening were addressed. This short-term educational intervention included sessions lasting approximately four hours and comprised of lectures, discussions, videos, and leaflets. A qualified expert (e.g., a female obstetrics and gynecology specialist, nurse, public health specialist, behavior specialist etc.) provided their knowledge and insight about HPV, cervical cancer and screening for cervical cancer, delivered knowledge base on cervical cancer during each of the sessions. On average, each lecture took approximately 45 minutes after which participants were given the opportunity to ask questions and any misconceptions were clarified. Participants were also given time to reflect and discuss issues concerning cervical cancer and screening amongst themselves. After educational sessions, the participants were reassessed with the same questionnaire instrument as used prior to the educational intervention, excluding the demographic and socioeconomic questions mentioned earlier, to assess any changes in knowledge and perceptions about the HPV, cervical cancer and cervical cancer screening. The participants were then asked to complete a thirty-three item questionnaire. The content of the presentations of each educational session addressed four fundamental topics: 1) Black Women and cervical cancer: A Historical Perspective 2) the high prevalence, incidence and mortality of cervical cancer among women, 3) cervical cancer is preventable and 4) how to prevent cervical cancer. For those participants who agreed to participate in the study but were not available at the time of data collection or the educational intervention, efforts were made to either collect the data or carry out the health education at a later date convenient to them but within the time period for the project.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using Statistical Analysis System (SAS) software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Basic descriptive statistics and frequency calculations were performed for all variables. In bivariate models for identifying the factors associated with screening and cervical cancer awareness, Pearson chi-square (χ2) or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables were used to examine association between some of demographics, socioeconomic factors and knowledge of cervical cancer, screening tests, HPV infections and HPV vaccine among groups. Trends based on indication of patient characteristics are reported descriptively. A two-tail alpha or a two-sided alpha to reject null hypotheses at 0.05, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and P-values with significance are marked in bold in the tables. A p-value is defined as the probability, if the null hypothesis is true, that you would obtain a sample statistic as great as or greater than the one you observed just by chance. All calculated statistics were obtained and presented in Microsoft word 2016 tables and bar graphs using Excel functions.

Results

Participant Demographics

As presented in Table 2, there were a total of 100 women participants. Of those participants, 86% self-identified as Blacks, 65% were over the age of 35, 65% were making less than $50k/year, 62% currently lived in the Tuskegee community, 34% engaged the community as students/faculty who resided outside of the Tuskegee community, 25% of the participants were either married or living with their partner, 75% were single, divorced, or widowed, more than 80% were in between their 1st year of college and graduate school, and 40% were currently working for pay. Among the 62% of women who resided in the Tuskegee community, 9% were diagnosed with cervical cancer. Of that 9%, 6% of those women were between the ages of 60–69. The remaining 3% were diagnosed at very young ages, 17, 28, and 32.

Table 2.

Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the participants.

| Demographic and socioeconomic variables | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Race | ||

| Blacks | 86 | 86.00 |

| Whites | 10 | 10.00 |

| Other | 4 | 4.00 |

| Age group in years | ||

| < 35 | 36 | 36.00 |

| 36–50 | 23 | 23.00 |

| 51–79 | 41 | 41.00 |

| Marital status | ||

| Divorced | 17 | 17.00 |

| Living with partner but not married | 4 | 4.00 |

| Married | 21 | 21.00 |

| No answer | 2 | 2.00 |

| Separated | 4 | 4.00 |

| Single | 43 | 43.00 |

| Widowed | 9 | 9.00 |

| Employment Status | ||

| Housewife | 4 | 4.00 |

| Not working | 6 | 6.00 |

| Retired | 18 | 18.00 |

| Student | 29 | 29.00 |

| Unable to work/disabled | 3 | 3.00 |

| Working for pay | 40 | 40.00 |

| Level of education | ||

| Between Grades 9–11 (some high school) | 2 | 2.00 |

| Between Grades 1–8 (elementary) | 4 | 4.00 |

| Between college 1–3 years (some college or technical school) | 15 | 15.00 |

| College 4 years or more (college graduate) | 38 | 38.00 |

| Grade 12 or GED | 8 | 8.00 |

| Graduate or Professional School | 33 | 33.00 |

| Level of annual income ($) | ||

| $10,000 to $14,999 | 7 | 7.00 |

| $15,000 to $19,999 | 4 | 4.00 |

| $20,000 to $24,999 | 9 | 9.00 |

| $25,000 to $29,999 | 3 | 3.00 |

| $30,000 to $49,999 | 13 | 13.00 |

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 7 | 7.00 |

| $75,000 or more | 7 | 7.00 |

| $9,999 or under | 28 | 28.00 |

| No answer | 22 | 22.00 |

| City | ||

| Franklin | 3 | 3.00 |

| Shorter | 1 | 1.00 |

| Tuskegee | 62 | 62.00 |

| Tuskegee University | 34 | 34.00 |

| TOTAL | 100 | 100.00 |

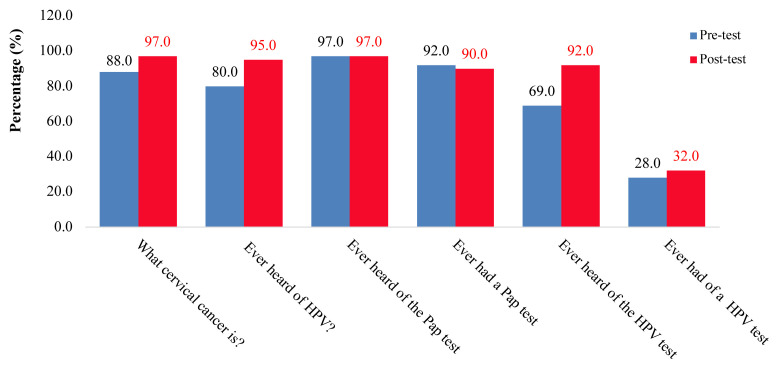

In the sample of 100 women who participated, those who knew what Cervical Cancer was increased after the intervention by 9%, whereas those who answered yes to “Have you ever heard of HPV?” and “Have you ever heard of the HPV-test?” improved by margins of 15% and 23% respectively. Amongst the participants who answered yes to “Have you ever heard of Pap test?” had the same knowledge level before and after the intervention. Unexpectedly, those participants who answered yes to “Have you ever had a Pap test?” decreased by 2%, following the intervention as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Percentage of participants who knew what cervical cancer is, ever heard of HPV, ever heard of Pap test, ever had a pap test, ever heard of the HPV test, and ever had a HPV test.

As shown in Figure 2, the participant’s knowledge increased in regard to cervical cancer, HPV, Pap test, and HPV test following the education-based intervention. The knowledge for the following questions had the most significant improvement levels following the intervention:

Figure 2.

Percentage of correct knowledge about cervical cancer, HPV test, Pap test, and HPV test.

Is cervical cancer caused by HPV infection? (Increased by a margin of 38%);

Can all HPV infections lead to cervical cancer? (39%)

Is cervical cancer decreasing in recent years? (50%)

The answers to the following questions also had levels of improvement after the intervention:

Is cervical cancer preventable? (22%)

Is cervical cancer usually asymptomatic in its early stages? (33%)

Can early detection of cervical cancer possibly save someone’s life? (12%)

Should screening tests be done regularly? (15%)

Can safe sex prevent cervical cancer? (26%)

Do Pap tests, alone, prevent cervical cancer? (22%)

Can a healthy lifestyle prevent cervical cancer? (25%).

Comparison of Association between Demographics, Social Status, and Knowledge

As shown in Table 3, a significant association was only found between the education and knowledge about HPV infection (Pearson Chi-Square (χ2) value: 13.911 and p = 0.009), knowledge about Pap test/Pap smear (χ2 value: 35.567 and p = 0.002) and knowledge about HPV vaccine (χ2 value: 17.488 and p = 0.049). As shown in the table below, many of the comparisons had p-values that were higher than 0.05 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of Association between some of demographics, socioeconomic factors and knowledge of cervical cancer, screening tests, HPV infections and HPV vaccine in women living in Macon county of Alabama.

| Variables | Pearson chi square value | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age and knowledge about cervical cancer | 2.944 | 0.234 |

| Income and knowledge about cervical cancer | 6.591 | 0.559 |

| Education and knowledge about cervical cancer | 13.312 | 0.065 |

|

| ||

| Age and knowledge about HPV infection | 4.019 | 0.137 |

| Income and knowledge about HPV infection | 5.269 | 0.754 |

| Education and knowledge about HPV infection | 13.911 | 0.009 * |

|

| ||

| Age and knowledge about Pap test/Pap smear | 2.220 | 0.331 |

| Income and knowledge about Pap test/Pap smear | 4.383 | 0.899 |

| Education and knowledge about Pap test/Pap smear | 35.567 | 0.002 * |

|

| ||

| Age and knowledge about HPV test | 0.215 | 0.924 |

| Income and knowledge about HPV test | 11.374 | 0.242 |

| Education and knowledge about HPV test | 8.895 | 0.097 |

|

| ||

| Age and knowledge about cervical cancer prevention | 0.503 | 0.783 |

| Income and knowledge about cervical cancer prevention | 7.823 | 0.500 |

| Education and knowledge about cervical cancer prevention | 6.047 | 0.335 |

|

| ||

| Age and knowledge about HPV vaccine | 3.935 | 0.424 |

| Income and knowledge about HPV vaccine | 16.068 | 0.379 |

| Education and knowledge about HPV vaccine | 17.488 | 0.049 * |

P* statistically significant difference (Chi-Square (χ2) Tests (Fisher’s Exact Test) P-value <0.05).

The Chi-square values and P-values were rounded to the nearest three decimal places.

Participants Diagnosed with Cervical Cancer

Of the 100 women participants, 9 women answered that they had been diagnosed with cervical cancer at some point in their lifetime. Of those 9 women who were diagnosed with cervical cancer: 7 self-identified as Black, they were all over the age of 60 (with the exception of 1 who was 52), 6 were making between $20k-$49k a year, 8 currently lived in the Tuskegee community, only 1 was married, 6 were retired, 7 were in between their 1st year of college and graduate school, and 40% were currently working for pay (Table 4).

Table 4.

Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of participants with cervical cancer.

| Demographic and socioeconomic variables | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 9 | 100.00 |

| Race | ||

| Blacks | 7 | 78.00 |

| Whites | 2 | 22.00 |

| Age group in years | ||

| 30–60 | 1 | 22.00 |

| 60+ | 8 | 78.00 |

| Marital status | ||

| Divorced | 2 | 22.00 |

| Married | 1 | 11.00 |

| No answer | 1 | 11.00 |

| Separated | 2 | 22.00 |

| Single | 1 | 11.00 |

| Widowed | 2 | 22.00 |

| Employment Status | ||

| Retired | 6 | 67.00 |

| Unable to work/disabled | 1 | 11.00 |

| Working for pay | 2 | 22.00 |

| Level of education | ||

| Between Grades 1–8 (elementary) | 1 | 11.00 |

| Between college 1–3 years (some college or technical school) | 3 | 33.00 |

| College 4 years or more (college graduate) | 3 | 33.00 |

| Grade 12 or GED | 1 | 11.00 |

| Graduate or Professional School | 1 | 11.00 |

| Level of annual income ($) | ||

| $20,000 to $24,999 | 1 | 11.00 |

| $25,000 to $29,999 | 2 | 22.00 |

| $30,000 to $49,999 | 3 | 33.00 |

| $9,999 or under | 3 | 33.00 |

| City | ||

| Franklin | 1 | 11.00 |

| Tuskegee | 8 | 88.00 |

| TOTAL | 9 | 100.00 |

Knowledge-increase of Cervical Cancer and HPV (Participants with cervical cancer)

As shown in Figure 3, before the educational-based intervention only 6 of the diagnosed participants had ever heard of HPV, ever had an HPV test, understood that cervical cancer is caused by HPV infection, and also understood that cervical cancer can be preventable. Only 1 of the 9 diagnosed participants knew that all HPV infections could lead to cervical cancer and that cervical cancer rates had been decreasing in recent years. Overall, the participants with cervical cancer had an increase in correct knowledge pertaining to cervical cancer, HPV, Pap test, and HPV test following the educational intervention. The knowledge of the following questions had the most significant improvement levels from the participants diagnosed with cervical cancer:

Figure 3.

Percentage of diagnosed participants with correct knowledge about cervical cancer, HPV test, Pap test, and HPV test.

Can all HPV infections lead to cervical cancer? (Increased by a margin of 67%)

Is cervical cancer decreasing in recent years? (89%)

The answers to the following questions also had levels of improvement after the intervention:

Have you ever heard of HPV? (33%)

Have you ever heard of an HPV test? (22%)

Is cervical cancer caused by HPV infection? (33%)

Is cervical cancer preventable? (33%)

Among the participants with cervical cancer, those who understood that all HPV infections can lead to cervical cancer increased after the intervention with a margin of 67% and those who understood that cervical cancer is decreasing in recent years increased by a margin of 89%. Those who understood cervical cancer is preventable and can be caused by HPV increased by a margin of 33%. Additionally, those who ever heard of HPV and actually had an HPV-test both improved by margins of 33% and 11%, respectively (Figure 3). Figure 4, shows that among the diagnosed participants who knew what cervical cancer was the knowledge level remained the same before and after the intervention. Those who understood that just a Pap test can’t prevent cervical cancer and that practicing safe sex reduces chances of contracting cervical cancer both had an improvement level of 22%. Similar to those knowledge points, those who answered yes to the question “Have you ever heard of an HPV test?” also increased by 22% after the educational intervention.

Figure 4.

Percentage of diagnosed participants who knew what cervical cancer is, ever heard of Pap test, ever had a Pap test, and ever heard of the HPV test.

Discussion

Overall, the findings of this study showed an increase in knowledge pertaining to cervical cancer and HPV. This supports the findings of a previous study in Jamaica that evaluated the effectiveness of an educational intervention based on pre and post questionnaires. The results showed a significant increase in cervical cancer knowledge from pre-test to post-test. (Coronado Interis et al., 2016)

Percentage of cervical cancer screening in women 18 and older living in Alabama and the US in 2014 was always high in Blacks, compared to counterparts. In Alabama, the cervical cancer screening percentage was 85.5% in Blacks 18 and Older versus 74.9 in Whites. Similarly, in the US 78.9 of Blacks were the most likely to get their cervical cancer screening compared to their White counterparts who had 75.5% cervical cancer screening (Cancer Facts & Figures 2017, n.d.). Based on Healthy People 2020 guidelines, the target for cervical cancer screening is 93.0 %, both Blacks and Whites in Alabama and the US did not reach this target yet. However, the state has not yet achieved the Healthy People 2020 screening goal (Cancer | Healthy People 2020, n.d.). Therefore, increasing screening uptake is pertinent.

Scarinci et al’s findings suggest that HPV vaccination and testing, if used in an effective manner, have the potential to transform cervical cancer prevention particularly among underserved populations (Scarinci et al., 2010). We suppose that these transformations in the Black Belt and other rural counties could have the potential to reduce this preventable disease. According to Canfell, when considering cervical cancer elimination one must first take into account that elimination means the disease is controlled and secondly that this has been accomplished with active interventions and proper surveillance of cervical cancer outcomes (Canfell, 2019).

There was no significance between the participants’ education levels and whether or not they had ever heard of a Pap test or HPV, however, there was significance between their education levels and if they answered yes to “Do you know what cervical cancer is?” Several studies have supported the positive relationship between education level and cervical cancer knowledge. In a similar study done in Kenya (2018) by Dutta et al, it reported that women who had an education level higher than secondary had a higher chance of being screened for cervical cancer than those women without an education (Dutta et al., 2018). Another study in Nepali concluded that the higher the education level, the better was the knowledge among participants which showed that education was necessary to create awareness of diseases (Poudel & Sumi, 2019). The significance between the participants’ education levels and their overall knowledge about HPV, knowledge about Pap test, and knowledge about HPV vaccine could be a result of 85% of the participants being in between their first year of college and graduate school. Future work will be done to target Middle School-aged girls (6th – 8th graders 11–14 years of age) living in Black Belt Counties of Alabama.

Poverty creates a barrier in regards to women obtaining proper cervical cancer screenings. We believe the lack of multiple public transportation systems and hospitals in Macon County could possibly have an effect on women seeking follow-up and treatment. There are also financial burdens that play a critical role in women obtaining cervical cancer screenings. Women with lower incomes and those without health insurance are less likely to be properly screened (Margolis et al., 1998).

We suggest that the mortality rate, 3.0 per 100,000 population, among women in rural Alabama with cervical cancer could be due to lack of awareness in this segment of the population. If more initiatives, such as a long-term educational intervention, were developed to address disparities amongst rural communities, we may be a step closer to improving the health and overall well-being of these underserved populations. Overall, this study showed an increase in knowledge of Cervical Cancer, Pap test/Pap smear and HPV among the public in Macon County was lacking. This could be due to the members of this community having a misunderstanding of cervical cancer and its prevention/treatment measures. Therefore, the lack of significant difference among the participants who knew what cervical cancer was and who had ever heard of HPV tests before and after the education-based intervention may be due to possible misconceptions prior to them being a part of the intervention. There were also participants who answered yes during the pre-questionnaire to “Have you ever had a Pap test?” and answered no during the post questionnaire. Similarly, participants who answered no to “Have you ever had a HPV test?” prior to the intervention came back with a response of yes. We believe this could be due to misinformation.

Different intervention methods and health behavior-change frameworks can provide an effective baseline level for cervical cancer prevention. Although we are exposing this community to cervical cancer knowledge and its prevention measures, more actions need to be taken to alter the community’s attitudes towards cervical cancer and HPV. This type of change is hypothesized to result in behavior-change. This intervention utilizes health education as it focuses merely on expanding the knowledge base of the targeted community. However, this findings of Rosser et al (2015) suggests that although educational interventions do increase participants’ knowledge, this does not automatically constitute an increase in screening uptake (Rosser et al., 2015). There may be a proportion of the participants to seek further assistance concerning screenings, but we still would have no certainty of attitude or behavior change amongst the participants. It is critical to assess the relationship between knowledge, attitudes, and behavior when it comes to improving the health status rural, underserved communities. This all-inclusive concept of health education recognizes that many experiences, both negative and positive in nature, have an effect on what individuals think, feel, and do about their health. For future work, initiatives to utilize health behavior-change frameworks may be more effective in decreasing the cervical cancer mortality rates.

In reference to the participants whom were diagnosed with cervical cancer, only one self-identified as married at the time of the intervention. Machida et al. (2018) examined trends of cervical cancer in single women and found that the rate of cervical cancer screening was reported to be lower among single women compared to married women. This could be due to married women having higher rates of pregnancy, which makes them more likely to undergo gynecologic examinations, including cervical cancer screenings. Married women are also at a lower risk of HPV because they typically have a consistent sex partner (Machida et al., 2018).

Among those participants with cervical cancer, nearly 50% of them had family members who were also diagnosed with cervical cancer. Although, most cervical cancers are caused by HPV infections, having a family member with a previous diagnosis may be a risk factor (Things You Should Know If You Have Cervical Cancer, n.d.). According to the American Cancer Society, having family members, such as a mom or sister, with cervical cancer increases your chances of having the disease than someone who doesn’t have it in their family history (Cervical Cancer Risk Factors | Risk Factors for Cervical Cancer, n.d.).

Based on the results of this study, 3 out of the 9 participants with cervical cancer had never heard of HPV prior to the intervention. This lack of knowledge was concerning because it could be a result in HPV knowledge not reaching key populations of Macon County (Kasymova et al., 2019). Zhuang et. al.’s findings identified lack of knowledge as a major barrier for participants to decline HPV vaccinations. Educational interventions promote an increase in knowledge; however, the increase in knowledge doesn’t directly translate to the participation in cervical cancer screening (Sossauer et al., 2014). The utilization of various educational intervention methods can help improve women’s behavior toward cervical cancer screenings (Naz et al., 2018). Different theories aimed at health behavior change indicate that increasing self-regulation skills and developing knowledge and beliefs during interventions may lead to the change of health behavior (Ryan, 2009).

Recommendations

Utilizing different health education methods such as calls, mailed items, radio broadcasts, mother/daughter interventions, and face to face interviews were effective in women’s behavior toward cervical cancer screening (Naz et al., 2018). Although it wasn’t a part of this intervention, a new method of HPV self-testing allowed women to not only receive testing in the comfort of their own home but it also eliminates a barrier between women who lack access to healthcare (Rees et al., 2018). The usage of a long term educational intervention would not only allow us to gradually provide information to participants, but it would also allow us to assess participants’ retainment level (Methods for Assessing Student Knowledge Over Time, n.d.).

Utilizing more intervention methods that focus on eliminating barriers to cervical cancer screenings can simplify access to cervical cancer screenings in underserved populations. These forms of intervention methods should focus on minimizing time or distance that lies between these populations and screening locations (Cancer Screening, 2014). Many women who reside in underserved populations struggle with transportation to and from health care facilities. Communities that suffer from these type barriers are referred to as transit deserts. Transit deserts are areas where demand for transportation exceeds the supply for transportation. In most cases, transit areas exist in underserved communities (Dozens of U.S. Cities Have ‘Transit Deserts’ Where People Get Stranded | Innovation | Smithsonian Magazine, n.d.). Different intervention strategies should also focus on adjusting hours of service to be more convenient to the participants’ needs. Women in rural underserved communities are more likely to possess low paying jobs without flexibility. Time conflicts would arise when women’s work hours are the same as work hours of health care professionals. Using more than one intervention strategy is known as a multicomponent approach. Multicomponent interventions are utilized in underserved communities to increase screenings. The Community Preventive Services Task Force (CPSTF) suggests multicomponent interventions to increase Pap smears and HPV testing (Cancer Screening, 2014). If these forms of interventions contribute to the provision of access to follow-up care and treatments, it could improve the health and reduce and/or eliminate the health disparities of these populations.

The high death rates for cervical cancer amongst communities in rural Alabama represent a critical health burden for women. The results of this study suggest that, although the participants lacked knowledge in certain areas, there was still an increase in their knowledge following the intervention. Different intervention methods and health behavior-change frameworks will provide an effective baseline level for cervical cancer prevention. An increase in intervention strategies can result in an increase in knowledge, contributing to the decrease of cervical cancer mortality rates. There was no significance between the participants’ education levels and whether or not they had ever heard of a Pap test or HPV, however, there was significance between their education levels and if they knew what cervical cancer was. In conclusion, this study showed that the correct knowledge of cervical cancer, Pap test/Pap smear and HPV among the women in Macon County was lacking prior to the intervention.

Limitations

There are various limitations associated with using survey tools for research. One general limitation attributed to survey research is dishonesty. There is no way to verify if participants are being 100% honest with their responses. This could be due to various personal reasons, such as privacy (“10 Advantages and Disadvantages of Questionnaires,” 2019). Another limitation ascribed to survey tools is the possibility of unanswered items. In the instance that questions are not made mandatory, there is always a risk that they won’t be answered (“10 Advantages and Disadvantages of Questionnaires,” 2019). In addition to those constraints, other limitations are the lack of time and funding necessary to carry out a survey (Limitations of surveys, n.d.).

Although we had a total of 100 women participants, we still noticed a limitation in conducting the educational intervention during the weekdays as it interfered with many women’s work schedules. This limitation interfered with our ability to reach the majority of our target population. With an increase in resources, we may be able to incentivize the participants with the same pay that they would lose from missing work. This could result in a meaningful increase in the number of participants in the intervention.

Another limitation was the proportion of participants that were educated on a collegiate level. The results stated there was a significant correlation between the participants’ education level and their knowledge about cervical cancer screenings. With more than 80% of the participants being in between their 1st year of college and graduate school, this indicates a need for similar interventions being conducted in the younger population at-risk. In addition to that, if a longer period of time was permitted for the educational intervention, it may lead to an improvement in results.

Conclusion

In conclusion, cervical cancer is a preventable disease that is disproportionally affecting Blacks compared to Whites in the United States. Alabama possesses high screening rates for cervical cancer; however, mortality rates still remain high. Among those rates, Blacks have a significantly higher mortality rate than Whites. This finding suggests that cervical cancer disparities still exist in Alabama. Access to correct knowledge about cervical cancer and HPV could play a major role in increase of cervical cancer screenings.

In this study, we assessed knowledge gain of women in Macon County, Alabama following a short-term educational intervention. Our findings suggested that cervical cancer control interventions and treatment patterns targeted to disadvantaged women, particularly women living in the Black Belt Counties and other rural counties, have the potential to reduce and/or eradicate this preventable disease. We suggest that the mortality rates among women in Macon County with cervical cancer could be due to lack of knowledge and willingness to promote awareness in this segment of the population.

In conclusion, this study showed that the knowledge of cervical cancer, Pap test/Pap smear and HPV among the general public in Macon County was lacking. The lack of significant difference among participants who knew what cervical cancer was and who ever heard of HPV tests before and after the intervention may be due to incorrect knowledge. There was no significance between the participants’ education levels and whether or not they ever heard of a Pap test or HPV, however, there was significance between their education levels and if they knew what cervical cancer was. This study showed an apparent increase in the participants’ knowledge following the education-based intervention. We believe that different intervention methods and health behavior-change frameworks could provide an effective baseline level for cervical cancer prevention. We also suggest that the increase of intervention occurrences can increase knowledge and possibly contribute to the lowering of mortality rates.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by the Tuskegee University Center for Biomedical Research/Research Centers in Minority Institutions (TU CBR/RCMI) Program at the National Institute of Health (NIH) with a CBR/RCMI U54 grant, with grant number MD007585 for funding this study.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Kellon Banks, MPH: Is the first author and major conceiver and designer of the manuscript. Participated and made major contributions to collection, cleaning, analysis, interpretation of the data and writing of the manuscript. Critically reviewed manuscript and approved the final version.

Ehsan Abdalla, DVM, MSc (Hons) (Vet PATH), MSc & PhD (Epidemiology and Risk Analysis): Is the corresponding author, has given significant intellectual inputs and supervised the work, participated in the conceiving and designing of the manuscript. Made major contributions to collection, cleaning, analysis, interpretation of the data, and writing of the manuscript. Critically reviewed manuscript and approved the final version.

Crystal M. James, JD. MPH: Participated in the collection and writing of the manuscript. Critically reviewed manuscript and approved the final version.

David Nganwa, DVM, MPH: Participated in designing of the manuscript. Made substantial contributions to collection and cleaning of the data. Participated in the writing of the manuscript. Critically reviewed manuscript and approved the final version.

John Heath, MS, PhD: Participated in the writing of the manuscript and critically reviewed manuscript and approved the final version.

Lloyd Webb, DVM, MPH: Participated in the writing of the manuscript and critically reviewed manuscript and approved the final version.

Isra Elhussin, MD, MS, Integrative Bioscience (IBS) PhD Fellow: Made substantial contributions to collection and cleaning of the data. Critically reviewed manuscript and approved the final version.

Rawah Faraj, DVM, MSc, PhD: Made substantial contributions to collection and cleaning of the data. Critically reviewed manuscript and approved the final version.

Authors’ Note

This study was funded by the Tuskegee University Center for Biomedical Research/Research Centers in Minority Institutions (TU CBR/RCMI) Program at the National Institute of Health (NIH) with a CBR/RCMI U54 grant, with grant number MD007585 for funding this study. The authors have no competing interests to disclose.

References

- 10 Advantages and Disadvantages of Questionnaires. Survey Anyplace. 2019. Mar 8, https://surveyanyplace.com/questionnaire-pros-and-cons/

- Abdalla EM. Abstract 1778: A comparison study of the disparities of cervical cancer excess mortality between Black and Caucasian women in Alabama and the US. Cancer Research. 2016;76(14 Supplement):1778–1778. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2016-1778. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alabama has highest rate of cervical cancer death in nation, says report—Al.com. n.d.-a. Retrieved April 14, 2020, from https://www.al.com/news/2018/11/alabama-has-highest-rate-of-cervical-cancer-death-in-nation-says-report.html.

- Avenue HRW| 350 F., York, 34th Floor | New, & t 1, 212290.4700, N. 10118-3299U. With the Highest Rate of Cervical Cancer Deaths in the US, Black Women in Alabama Are Losing Out on Health Care. Human Rights Watch; 2019. Apr 19, https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/04/19/highest-rate-cervical-cancer-deaths-us-black-women-alabama-are-losing-out-health . [Google Scholar]

- Basic Information About Cervical Cancer. CDC; 2019. Aug 28, https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/cervical/basic_info/index.htm . [Google Scholar]

- Burd EM. Human Papillomavirus Laboratory Testing: The Changing Paradigm. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2016;29(2):291–319. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00013-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer | Healthy People 2020. n.d. Retrieved April 15, 2020, from https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/cancer/objectives.

- Cancer Facts & Figures 2017.pdf. n.d. Retrieved April 14, 2020, from https://www.alabamapublichealth.gov/ascr/assets/factsfigures20162017.pdf.

- Cancer of the Cervix Uteri—Cancer Stat Facts. SEER; n.d. Retrieved April 14, 2020, from https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/cervix.html. [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Screening: Reducing Structural Barriers for Clients – Cervical Cancer. The Guide to Community Preventive Services (The Community Guide); 2014. Apr 18, https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/cancer-screening-reducing-structural-barriers-clients-cervical-cancer . [Google Scholar]

- Canfell K. Towards the global elimination of cervical cancer. Papillomavirus Research. 2019;8 doi: 10.1016/j.pvr.2019.100170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervical Cancer Risk Factors | Risk Factors for Cervical Cancer. n.d. Retrieved April 14, 2020, from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cervical-cancer/causes-risks-prevention/risk-factors.html.

- Cervical Cancer Statistics | Key Facts About Cervical Cancer. n.d. Retrieved April 14, 2020, from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cervical-cancer/about/key-statistics.html.

- Cervical Health Awareness Month—NCCC : NCCC. n.d. Retrieved April 14, 2020, from https://www.nccc-online.org/hpvcervical-cancer/cervical-health-awareness-month/

- Coronado Interis E, Anakwenze CP, Aung M, Jolly PE. Increasing Cervical Cancer Awareness and Screening in Jamaica: Effectiveness of a Theory-Based Educational Intervention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2016;13(1):53. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13010053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozens of US Cities Have ‘Transit Deserts’ Where People Get Stranded | Innovation. Smithsonian Magazine. n.d. Retrieved April 15, 2020, from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/dozens-us-cities-have-transit-deserts-where-people-get-stranded-180968463/

- Dutta T, Haderxhanaj L, Agley J, Jayawardene W, Meyerson B. Association Between Individual and Intimate Partner Factors and Cervical Cancer Screening in Kenya. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2018;15 doi: 10.5888/pcd15.180182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Excess Cervical Cancer Mortality: A Marker for Low Access to Health Care in Poor Communities. n.d:96. [Google Scholar]

- Factsfigures2012.pdf. n.d. Retrieved April 14, 2020, from http://www.alabamapublichealth.gov/ASCR/assets/factsfigures2012.pdf.

- Fleming S, Schluterman NH, Tracy JK, Temkin SM. Black and White Women in Maryland Receive Different Treatment for Cervical Cancer. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores K, Bencomo C. Preventing cervical cancer in the Latina population. Journal of Women’s Health. 2009;2002;18(12):1935–1943. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalani SV, Janitz AE, Campbell JE. Trends in cervical cancer incidence and mortality in Oklahoma and the United States, 1999–2013. Cancer Epidemiology. 2018;56:140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2018.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gynecologic Cancers. CDC; 2020. Mar 2, https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/gynecologic/index.htm . [Google Scholar]

- HPV Vaccine | What Is the HPV Vaccination. n.d. Retrieved April 14, 2020, from https://www.plannedparenthood.org/learn/stds-hiv-safer-sex/hpv/should-i-get-hpv-vaccine.

- Ito T, Takenoshita R, Narumoto K, Plegue M, Sen A, Crabtree BF, Fetters MD. A community-based intervention in middle schools to improve HPV vaccination and cervical cancer screening in Japan. Asia Pacific Family Medicine. 2014;13(1) doi: 10.1186/s12930-014-0013-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasymova S, Harrison SE, Pascal C. Knowledge and Awareness of Human Papillomavirus Among College Students in South Carolina. Infectious Diseases. 2019;12 doi: 10.1177/1178633718825077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limitations of surveys. n.d. Retrieved April 15, 2020, from http://conflict.lshtm.ac.uk/page_26.htm.

- Machida H, Blake EA, Eckhardt SE, Takiuchi T, Grubbs BH, Mikami M, Roman LD, Matsuo K. Trends in single women with malignancy of the uterine cervix in United States. Journal of Gynecologic Oncology. 2018;29(2) doi: 10.3802/jgo.2018.29.e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis KL, Lurie N, McGovern PG, Tyrrell M, Slater JS. Increasing Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening in Low-Income Women. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1998;13(8):515–521. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00161.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGhee E, Harper H, Ume A, Baker M, Diarra C, Uyanne J, Afework S, Partlow K, Tran L, Okoro J, Doan A, Tate K, Rouse M, Tyler M, Evans K, Sanchez T, Hasan I, Smith-Joe E, Maniti J, Pattillo R. Elimination of Cancer Health Disparities through the Acceleration of HPV Vaccines and Vaccinations: A Simplified Version of the President’s Cancer Panel Report on HPV Vaccinations. Journal of Vaccines & Vaccination. 2017;8(3) doi: 10.4172/2157-7560.1000361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Methods for Assessing Student Knowledge Over Time. Study.Com. n.d. Retrieved April 14, 2020, from https://study.com/academy/lesson/methods-for-assessing-student-knowledge-over-time.html.

- Naz MSG, Kariman N, Ebadi A, Ozgoli G, Ghasemi V, Fakari FR. Educational Interventions for Cervical Cancer Screening Behavior of Women: A Systematic Review. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention: APJCP. 2018;19(4):875–884. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2018.19.4.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poudel K, Sumi N. Analyzing Awareness on Risk Factors, Barriers and Prevention of Cervical Cancer among Pairs of Nepali High School Students and Their Mothers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019;16(22) doi: 10.3390/ijerph16224382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees I, Jones D, Chen H, Macleod U. Interventions to improve the uptake of cervical cancer screening among lower socioeconomic groups: A systematic review. Preventive Medicine. 2018;111:323–335. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosser JI, Njoroge B, Huchko MJ. Changing knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors regarding cervical cancer screening: The effects of an educational intervention in rural Kenya. Patient Education and Counseling. 2015;98(7):884–889. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan P. Integrated Theory of Health Behavior Change: Background and intervention development. Clinical Nurse Specialist CNS. 2009;23(3):161–170. doi: 10.1097/NUR.0b013e3181a42373. quiz 171-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saqer A, Ghazal S, Barqawi H, Babi JA, AlKhafaji R, Elmekresh MM. Knowledge and Awareness about Cervical Cancer Vaccine (HPV) Among Parents in Sharjah. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention: APJCP. 2017;18(5):1237–1241. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2017.18.5.1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarinci IC, Garcia FAR, Kobetz E, Partridge EE, Brandt HM, Bell MC, Dignan M, Ma GX, Daye JL, Castle PE. Cervical Cancer Prevention: New Tools and Old Barriers. Cancer. 2010;116(11):2531–2542. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sossauer G, Zbinden M, Tebeu P-M, Fosso GK, Untiet S, Vassilakos P, Petignat P. Impact of an Educational Intervention on Women’s Knowledge and Acceptability of Human Papillomavirus Self-Sampling: A Randomized Controlled Trial in Cameroon. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STD Facts—HPV and Men. 2019. Sep 23, https://www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/stdfact-hpv-and-men.htm .

- STD Facts—Human papillomavirus (HPV) 2019. Sep 12, https://www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/stdfact-hpv.htm .

- Things You Should Know If You Have Cervical Cancer. WebMD; n.d. Retrieved April 14, 2020, from https://www.webmd.com/cancer/cervical-cancer/things-to-know-if-you-have-cervical-cancer. [Google Scholar]

- WHO | Cervical cancer. n.d. Retrieved April 14, 2020, from https://www.who.int/cancer/prevention/diagnosis-screening/cervical-cancer/en/

- Wong FL, Miller JW. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program: Increasing Access to Screening. Journal of Women’s Health. 2019;2002;28(4):427–431. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2019.7726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L. Rural–Urban and Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Invasive Cervical Cancer Incidence in the United States, 2010–2014. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2019;16 doi: 10.5888/pcd16.180447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]