Abstract

The writings of Jane Jacobs led urbanists to advocate for increased social diversity in neighborhoods as a method of promoting vitality in public spaces. Since then, New York City has become both a role model and a testing ground for zoning changes that support this objective. However, since the 2000s community activists and scholars have argued that these zoning changes have led to the dislocation of communities of color and incentivized gentrification. This project analyzed panel social and housing census data from 1990 and 2015 to assess the validity of these arguments. Results suggest that zoning changes have limited and differentiated effects on the different dimensions of social diversity. For instance, they have strong effects on household income diversity, a nuanced effect on race diversity, and slightly negative effects on family type diversity.

Keywords: Urban form, New York City, social diversity, zoning, gentrification

Introduction

The recent availability of quantitative data about cities has motivated a set of empirical studies that attempt to validate the traditional theories about urbanism. At present, the discourses that dominate the theory of urbanism have a common origin in the ideas promoted by Jane Jacobs in the 1960s, and they are associated with the use of neotraditionalist urban forms, compact urban growth, and urban intensification in the central core of cities. The intensification discourse argues that policies must incentivize a mixture of land uses and increase dwelling densities to improve the walkability and vitality of neighborhoods; but also, this discourse argues that the provision of different housing alternatives increases social diversity because people of different income levels, races, and family types living in proximity, increases social and economic relationships between them and thus contributes to social equity and cohesion.

While, the body of literature about the assessment of walkability in neighborhoods is relatively well developed, social diversity literature is less well developed and there is still no consensus among academics and practitioners of urbanism about the definition and implications of this diversity. For instance, scholars do not agree whether social diversity itself has a positive or negative effect on communities or how much the built environment can influence it. Therefore, this study seeks to improve our understanding of the relationship between social diversity and urban form. Specifically, this study expands the quantitative evidence about the effect of changes in the urban form on social diversity through an analysis that takes into account its different dimensions.

Literature review

The contemporary theoretical underpinnings of the importance of social diversity in urbanism are rooted in Jane Jacobs’ ideas in which she described how the mixture of housing along with other activities, such as retail and services, within neighborhoods facilitated the interaction of people of different backgrounds, ages, and income on the streets (1961). More recently, another renowned scholar, Richard Florida (2002) argued that social diversity in cities benefits the local economies as diverse areas attract highly educated individuals. These individuals, called the “Creative Class,” by Florida, are capable of developing new businesses for the creative economy, thereby enlarging the local tax base and creating jobs. Besides Jacobs and Florida, other scholars have highlighted the importance of social diversity in addressing neighborhood effects on inter-generational immobility, focusing on the problems of concentrated poverty in public housing projects across the United States (Ellen and Turner 2003; Galster, Cutsinger, and Malega 2008; The Brookings Institution and Federal Reserve Bank 2008; Wilson 1990).

Resulting from these theories, a new generation of planning practitioners have been promoting the intensification of urban form, and the diversification of housing typologies to catalyze street vitality and social diversity in neighborhoods (Talen 1999; Gehl 2011). However other scholars and practitioners have criticized these approaches arguing that this new type of urbanism at the small scale cause gentrification. Susan Fainstein, for example, argues:

Diversity is one of the principles of the just city; but is one that is constrained by scale. On the metropolitan scale it is appropriate to have places where different social groups can cluster, however, the intermixture of social conditions at the neighborhood scale may, in opposition, create environments of conflict, brought by gentrification, ethnic violence, or intergenerational incompatible lifestyles (2010, 67).

The availability of spatial information and data processing technologies has led scholars to further assess the concept of social diversity, hoping to understand if Jacobs’ or Florida’s theories could be statistically proven. An example of this branch of research is a paper by Pendall and Caruthers (2003) that connected income segregation with population density. They traced curvilinear relationships between income segregation and density for different cities across the United States. They found that the correlation curve bends at different levels depending on the morphology of the city i.e. if it is predominantly compact like Chicago or sprawled like Phoenix. Internationally, scholars have been also exploring the relationship between high-density development, social diversity, and segregation. Studies about mid-sized cities in England have found positive associations between high densities and lower social segregation levels (Burton 2000) and more interaction among neighbors in denser areas (Bramley et al. 2009). Contradictory relationships however were found in the developing world. Studies in Mumbai (Dave 2011) and Santiago (Aquino and Gainza 2014) show that the potential relationship between density and social integration is being overshadowed by traditional spatial separation in the city among high and lower classes.

Emily Talen, a renowned scholar of urban theory and social diversity, argues that social diversity may not solely produce conflict but, on the contrary, it may nurture environments of tolerance and mutual benefit in neighborhoods. To prove her point, she performed a study in the city of Chicago (2006, 2010) where she used four dimensions of social diversity: race, household income levels, age, and family types (2008, 66–67). She discovered that such neighborhoods exist and that their diversity conveys understanding among different social groups and energizes the local economy. Furthermore, in her book “Design for Diversity” (2008) she proved that the goals of vitality, economic growth, tolerance, sustainability, and social justice in cities may be accomplished through urban design strategies that relate to the different dimensions of social diversity. More importantly, Talen was able to trace a statistical relationship between residential density and social diversity. This connection is curvilinear: at first increasing densities encourage household income diversity, but only up to a point, where from there high densities reverse their effect and trigger income clustering. Following these findings, Talen was able to propose that the built environment has a relationship that at least explains a third of social diversity in a neighborhood, the other factors being urban policy and history (2008, 24). Recently other authors also have pointed-out other characteristics of the built environment that contribute to social diversity. Examples of these are traditional commercial and residential urban typologies that contribute to a sense of place (Sharifi and Murayama 2013), or a variety of age in buildings, first proposed by Jane Jacobs and currently statistically proven (King 2013; Sung, Lee, and Cheon 2015).

On the other hand, there are many academic criticism of zoning changes and intensification policies that urbanists promote. Mostly critics argue that such changes induce booms in development that become powerful drivers of gentrification in neighborhoods. For instance, in New York City, areas in lower and mid-town Manhattan and central Brooklyn, which had a large population of low income and communities of color in the 1970s, experienced displacement and dislocation during the 1990s and 2000s eventually turning more white and affluent. During the 2000s, scholars and community advocates have extensively documented these changes in books, journal articles, and movie documentaries.

One example of this is Sharon Zukin’s book “Naked City, the Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places” (2009), that analyzes the gentrification processes in six archetypal neighborhoods in New York City. She outlines how developers have ironically transformed Jacobian prescriptions for urban vitality into forces that destroy the authenticity of neighborhoods. Another example is found in the book “New York for Sale” (2011) written by Angotti and Marcuse, that showcases how local communities struggle against the plans formulated by the city authorities. The authors show how some communities succeed in stopping the “development machine” and formulate their own community-based plans that resist the influx of development and prevent gentrification. Other activists have used documentaries to illustrate how communities are dislocated by new local plans, as in the case in Kelly Anderson’s “My Brooklyn” (2012). The documentary recounts experiences of dislocation – including that of the director herself – of the traditional communities of central Brooklyn within the context of a new downtown Brooklyn rezoning effort. The plan promoted the densification and diversification of Brooklyn to catalyze economic development and increase housing availability in well-connected areas. However, Anderson’s documentary exposes how the plan also led to the elimination of affordable housing units and the displacement of local businesses mostly owned by African-Americans.

These are just a few examples of the intensive research surrounding gentrification that academics have written in the latest decades. These works join several other papers about New York City that explain in detail how authorities and developers trigger gentrification through zoning changes promoted by urbanists (Hackworth 2001, 2002; Lees 2003; Newman and Wyly 2006; Curran 2007; Zukin et al. 2009; Osman 2011; Pearsall 2013; Stabrowski 2014).

Case study

This paper uses New York City (NYC) as a case study because its significance in the development of theories and policies about planning and urbanism that are then applied elsewhere. Since the early 20th century, NYC has been a laboratory of policy intervention to control the urban form in response to different urban problems at different points in time. For instance, in 1916 the city introduced the first urban form control in the United States in an effort to mitigate the negative impacts of high-rise buildings on neighboring properties, such as reductions in natural light and ventilation. In the subsequent post-war years under the influence of city planner Robert Moses the city underwent a large urban renewal that resulted in the demolition of large areas of the city consisting of mid-rise tenement buildings considered overcrowded and substandard. To cope with the new requirements of hygiene and efficiency, urbanists developed a new urban typology that became known as the “tower-in-the-park.” Moses, during the mid-twentieth century, developed numerous tower-in-the-park compounds, known as Public Housing projects, in the Lower-East Side and East Harlem in Manhattan, as well as across the Bronx and northern Brooklyn, which were managed by the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA).

Special purpose districts (SD)

Jacob’s critique of tower-in-the-park urbanism soon led to a different approach to zoning and affordable housing policies in NYC. For instance, in the second half of the twentieth century planners and urbanists developed a new zoning tool known as “Special Purpose Districts” (SDs). The SDs are, broadly speaking, zoning overlays in specific neighborhoods to fulfill specific planning objectives such as promoting street vitality, social diversity, and neighborhood character. They are widespread across the city and are referred to as “Enhanced Commercial Districts” or “Special Mixed Use Districts.” Well-known areas of the city such as Little Italy, the Upper West Side or Battery Park City in Manhattan; or Park Slope, DUMBO or Coney Island in Brooklyn, are designated SDs.

Historic districts (HD)

Concurrently, the demolition of the old Penn Station in 1963 triggered a social movement to protect areas of historic and cultural significance from uncontrolled development. This invigorated the preservationist movement and, in conjunction with Jacobs’ ideas, eventually led city authorities to declare not only buildings but entire neighborhoods as historically significant; and establish strict built form rules to control their redevelopment. These rules were comprised of the “Historic Districts” (HDs) designation, which can include several city blocks or just a few houses. The Landmark Preservation Commission first applied the HD designation to Brooklyn Heights and since then, the Commission has designated 120 HDs across the city. Some examples of HDs in New York City are Park Avenue, Greenwich Village, and Chelsea in Manhattan; Prospect Heights and Greenpoint in Brooklyn; Hunters Point and Jackson Heights in Queens, and the Grand Concourse in the Bronx.

Inclusionary housing (IH)

More recently, authorities have developed a new generation of zoning policies that are aimed at addressing concerns about gentrification in the city. The most important move has been the creation of an existing optional density bonus to developers. The bonus is given to market-rate housing projects that include affordable units in designated areas undergoing gentrification. This policy has been referred to as the “Inclusionary Housing Program” (IH). However, these IH areas have been criticized for being insufficient in terms of replacing affordable units lost to the speculative real estate market forces (Stabrowski 2015). Other academics criticize how developers adapt the affordable units to the market-rate housing, often using a second door to give access the subsidized units. This entrance is often designed to be hidden from view and with much less architectural quality than the other parts of the building. As result, this feature has become known as “the poor door,” and has been banned by city authorities (Licea 2016; Navarro 2014).

Methodology and data

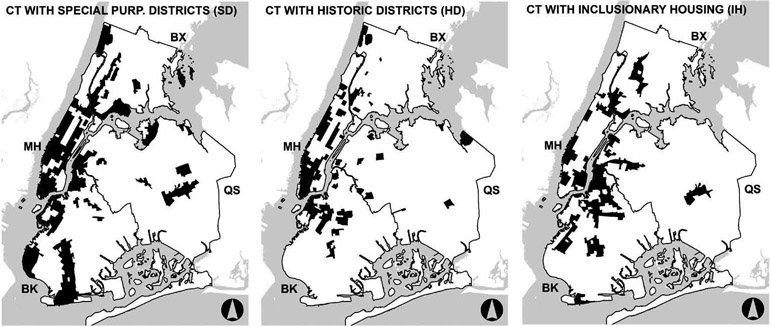

As we argued before, thanks to the new availability of statistical and GIS data, scholars can now quantitatively assess the relationships between variables of the built form and levels of social diversity across neighborhoods. Following Talen’s theories and the controversies explained in the sections before, and focusing on zoning changes such as the SDs, HDs, and the IH program, this research aims to explore the relationship between these zoning changes in NYC and the dimensions of social diversity that Talen previously identified – race, household income levels, age, and family types. We used census data from 1990 and 2015 to build an experiment with a pre- and post-observation period with a timeframe of 25 years. For 1990, we used Decennial census data and for 2015, we used data from the American Community Survey (ACS) – five year estimates. We choose to use census tracts and not census block groups as the unit of analysis to simplify the statistical operations. We also observed that, because of the high density of NYC, the census tracts include only a handful of city blocks, and therefore, it is a proper scale that approaches to the area that people often associate with “neighborhoods”. Our analysis looked at 465 census tracts incorporating SDs, 248 census tracts incorporating HDs, 313 census tracts with IH, and 1,269 census tracts without any of the zoning changes. Figure 1 provides a set of maps that show the location of the census tracts used in this analysis across the boroughs of Manhattan (MH), Brooklyn (BK), the Bronx (BX) and Queens (QS).

Figure 1.

Zoning changes in census tracts across NYC. Elaborated by the authors based in NYC planning.

We used a fixed effects (FE) regression model to trace the association between these different combinations of zoning changes and the variations in the social composition of census tracts in the four boroughs mentioned above, for 1990 and 2015. FE regression models analyze panel (longitudinal) data representing the observed quantities as non-random and imposes time independent effects for each entity that are correlated with the independent variables. In this way, the FE models controls for unobserved heterogeneity of the observations, in this case census tracts, when this heterogeneity is constant over time. The main limitation of using FE models is that they do not account for time-varying heterogeneity between census tracts. We try to overcome this disadvantage controlling for other socio-economic and housing variables that vary overtime, but nonetheless we try to be cautious about claiming causality.

The dependent variable in the FE model consisted of the levels of social diversity of each census tract for both 1990 and 2015 based on Talen’s classifications. In this specific case, we found collinearity between family type diversity and age diversity. Young people are likely to live in single-person households, while older people often live with children. As a result, we analyzed only three of the four Talen’s dimensions: race, household income levels, and family type. In order to measure levels of social diversity, we used the open-source software “Geo-Segregation Analyzer” (Apparicio et al. 2014) that automatically processes the multi-group Entropy index (h). The Entropy index, widely used in literature about residential segregation (Massey and Denton 1988; Iceland 2004), measures the departure from evenness by assessing each unit’s departure from the pattern of the whole city for multiple groups simultaneously. It reaches a maximum of 1.0 when groups in a district have a share division equal to that of the city. We provide the formula for the calculation of the multi-group Entropy index in Equation 1, where corresponds to the Entropy of census tract; to the number of groups (in race, income or family type); to the proportion of population of group in tract , where is the number of population of group in census tract ; and to the total population in census tract )

| (1) |

For independent variables we used dummy variables to represent the three different zoning changes (SDs, HDs and IH) and, as mentioned before, we choose to control for housing and socio-economic characteristics in each census tract to increase the validity of the study and explore other variables that may contribute to social diversity. For housing, we controlled for variables such as the existence of NYCHA public housing projects in the census tract, the total number of units, rates of ownership and vacancy, the diversity of housing typologies, and the age of construction. In the socio-economic control variables, we included the rate of white population and married households, the age of individuals, and the household annual income. We provide a detail descriptive table of the variables used in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of variables.

| Categories | Unit | Data Source | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DEPENDENT VARIABLES | |||

| Dimensions of Social Diversity | |||

| h Race | Asian | Count | 1990: US Census |

| Black | 2015: ACS-5 year estimates | ||

| Native | |||

| Other | |||

| White | |||

| h Household Annual Income Level | Less than $25K | Count | 1990: US Census |

| $25K – $50K | 2015: ACS-5 year estimates | ||

| $50K – $75K | |||

| $75K – $100K | |||

| More than $100K | |||

| h Family Type | Single person | Count | 1990: US Census |

| Single parent | 2015: ACS-5 year estimates | ||

| Married couple with children | |||

| INDEPENDENT VARIABLES | |||

| Dummies Zoning Changes | |||

| Special Purpose District (SPD) | Yes (1) | N/A | NYC Planning |

| No (0) | |||

| Historic District (HD) | Yes (1) | N/A | NYC Planning |

| No (0) | |||

| Inclusionary Housing Program (IHP) | Yes (1) | N/A | NYC Planning |

| No (0) | |||

| CONTROL VARIABLES | |||

| Housing Characteristics Variables | |||

| Dummy NYCHA Project | Yes (1) | N/A | NYC Planning |

| No (0) | |||

| Number of Housing Units | N/A | Count | 1990: US Census |

| 2015: ACS-5 year estimates | |||

| Housing Ownership | N/A | Percentage | 1990: US Census |

| 2015: ACS-5 year estimates | |||

| Housing Vacancy | N/A | Percentage | 1990: US Census |

| 2015: ACS-5 year estimates | |||

| Housing Typology | 1 unit | Count | 1990: US Census |

| 2 to 4 units | 2015: ACS-5 year estimates | ||

| 5 unit or more | |||

| Average Year of Construction | N/A | Year | 1990: US Census |

| 2015: ACS-5 year estimates | |||

| Socio-Economic Characteristics Variables | |||

| White Population | N/A | Percentage | 1990: US Census |

| 2015: ACS-5 year estimates | |||

| Married Households | N/A | Percentage | 1990: US Census |

| 2015: ACS-5 year estimates | |||

| Age of Individuals | Less than 18 | Count | 1990: US Census |

| 18 to 34 | 2015: ACS-5 year estimates | ||

| 35 to 65 | |||

| More than 65 | |||

| Household Annual Income | Less than $25K | Count | 1990: US Census |

| $25K – $50K | 2015: ACS-5 year estimates | ||

| $50K – $75K | |||

| $75K – $100K | |||

| More than $100K |

Using the dependent and independent variables described above we built three FE models shown in Equations 2, 3, and 4, where the dependent variable is the social diversity level in each of the three dimensions, measured through the Entropy index for census tract for time (1990 or 2015). The independent variables are dummies for Special Purpose Districts (SD), Historic Districts (HD), and Inclusionary Housing Program (IH); is the unknown intercept for census tract; is the error term for census tract for time ; and Control Variables are those shown in detail in Table 1.

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

Results

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the dependent variables, the Entropy () levels of social diversity for each of the dimensions, both in 1990 and in 2015. The table shows first that, across the board, race diversity is overall lower than income or family type diversity at both moments in time. Means for race diversity are 0.4–0.6 for all tracts at both moments of time while for household income and family type are 0.7–0.9. In addition, standard deviations suggest values for race diversity are slightly more dispersed across the census tracts than for the other dimensions of diversity. Standard deviations of race for both 1990 and 2015 were higher than 0.14 in all cases, while for household income and family type were in all cases lower than 0.16. This suggest that there is more racial clustering in NYC than clustering of the other types of social conditions, while zoning changes may have little effect on this. Secondly, race and household income diversity grew over time while family type diversity is higher and slightly decreased or stayed the same. In 1990 race diversity across the census tracts had means of 0.4–0.5; for household income the mean reached 0.6–0.8; and for family type 0.8–0.9. In 2015, means for race diversity increased to 0.5–0.6, means for household income diversity increased to 0.9–1.0; while at the same time, means for family type diversity decreased slightly or remained at similar levels. This suggests that NYC is more diverse in race and income in 2015 compared to 1990, while family type diversity levels are high and stable. Finally, broadly speaking, means for all the dimensions of diversity in census tracts without zoning changes were similar to those with either SDs, HDs or IH, in both moments of time. This could challenge the assumption that zoning is the main driver of social changes across the city.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of census tracts, social diversity and zoning.

| SD | HD | IH | None | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| h Race | |||||

| 1990 | Min. | 0.043 | 0.068 | 0.068 | 0.013 |

| Mean | 0.454 | 0.397 | 0.533 | 0.417 | |

| Median | 0.460 | 0.394 | 0.581 | 0.398 | |

| Max. | 0.903 | 0.850 | 0.903 | 0.886 | |

| St.Dev. | 0.221 | 0.193 | 0.198 | 0.230 | |

| Count | 461 | 248 | 313 | 1269 | |

| 2015 | Min. | 0.026 | 0.069 | 0.080 | 0.020 |

| Mean | 0.535 | 0.510 | 0.600 | 0.530 | |

| Median | 0.552 | 0.509 | 0.626 | 0.565 | |

| Max. | 0.915 | 0.915 | 0.902 | 0.914 | |

| St.Dev. | 0.175 | 0.158 | 0.146 | 0.195 | |

| Count | 461 | 248 | 313 | 1269 | |

| h Household Income | |||||

| 1990 | Min. | 0 | 0.301 | 0 | 0 |

| Mean | 0.741 | 0.795 | 0.651 | 0.750 | |

| Median | 0.774 | 0.832 | 0.675 | 0.785 | |

| Max. | 0.993 | 0.993 | 0.993 | 0.989 | |

| St.Dev. | 0.179 | 0.156 | 0.163 | 0.161 | |

| Count | 461 | 248 | 313 | 1269 | |

| 2015 | Min. | 0.290 | 0.441 | 0.290 | 0 |

| Mean | 0.902 | 0.915 | 0.897 | 0.918 | |

| Median | 0.930 | 0.931 | 0.931 | 0.950 | |

| Max. | 0.998 | 0.992 | 0.997 | 0.998 | |

| St.Dev. | 0.089 | 0.070 | 0.100 | 0.091 | |

| Count | 461 | 248 | 313 | 1269 | |

| h Family Type | |||||

| 1990 | Min. | 0.066 | 0.508 | 0.066 | 0 |

| Mean | 0.859 | 0.849 | 0.917 | 0.904 | |

| Median | 0.897 | 0.893 | 0.950 | 0.917 | |

| Max. | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.999 | 1 | |

| St.Dev. | 0.124 | 0.125 | 0.102 | 0.083 | |

| Count | 461 | 248 | 313 | 1269 | |

| 2015 | Min. | 0 | 0.404 | 0.404 | 0.400 |

| Mean | 0.835 | 0.825 | 0.875 | 0.908 | |

| Median | 0.861 | 0.845 | 0.910 | 0.932 | |

| Max. | 0.999 | 1 | 0.999 | 0.999 | |

| St.Dev. | 0.131 | 0.126 | 0.114 | 0.083 | |

| Count | 461 | 248 | 313 | 1269 |

In terms of types of zoning changes, a comparison of means in Table 2 suggests that social diversity and its changes between 1990 and 2015 are more similar for census tracts with SDs and HDs than with IH across the three dimensions. Racial diversity increased more in tracts with HDs (Δ.113) than in SD (Δ.081) or IH (Δ.067). Household income diversity increased significantly more in tracts with IH (Δ.246) than SD (Δ.161) or IH (Δ.120); while family type diversity decreased slightly more in IH (Δ−.042) than in tracts with SD or HD (both Δ−.024). This shows that census tracts with IH were less prone to changes in race diversity, while more to changes in diversity of household income and family type. This may respond to IH tracts being more peripheral and having more NYCHA public housing projects. With lower real estate prices neighborhoods are more sensible to gentrification.

Table 3 shows the FE regression results. In terms of racial diversity the results of the model show that SDs and HDs are positively associated, while IH is not significant. For housing characteristics and race diversity, the results show that only public housing was positively associated, while housing ownership was negatively associated. For socio-economic characteristics, adults and the elderly were negatively associated with race diversity. Variables such as different housing typologies, multifamily buildings or building age, are not statistically associated with levels of racial diversity.

Table 3.

Fixed effects models results.

| Dependent Variable |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variable |

Race (+) > Diversity |

Household Income (+) > Diversity |

Family Type (+) > Diversity |

| Zoning Changes | |||

| Special Purpose District (SD) | 2.70e-2* | 5.37e-2*** | − 1.78e-2** |

| Historic District (HD) | 8.37e-2*** | 2.74e-2* | − 1.87e-2* |

| Inclusionary Housing Program (IH) | − 1.21e-2 | 1.33e-1*** | − 3.24e-2*** |

| Housing Characteristics | |||

| NYCHA Public Housing | 8.78e-2*** | 9.35e-2*** | − 1.54e-2** |

| Number of Housing Units | 1.39e-4 | − 5.07e-5 | − 1.52e-4** |

| Housing Ownership | − 6.11e-5** | − 9.04e-5*** | 7.77e-6 |

| Housing Vacancy | 1.63e-5 | 7.43e-5** | 2.05e-5 |

| Housing Typology | |||

| 1 Unit | − 8.38e-5 | 1.45e-4 . | 1.31e-4* |

| 2 to 4 Units | − 1.34e-4 | 7.47e-5 | 1.57e-4** |

| More than 5 Units | − 1.38e-4 | 4.70e-5 | 1.51e-4** |

| Entropy Housing Typology | − 1.98e-2 | 9.82e-2*** | 8.35e-2*** |

| Average Year of Construction | − 3.78e-6 | 2.03e-4*** | 6.54e-5*** |

| Socio-Economic Characteristics | |||

| White Population | − 1.68e-5** | 2.74e-6 | − 5.25e-6* |

| Married Households | 3.62e-5 | − 1.54e-4*** | − 2.65e-5 . |

| Age of Individuals Less than 18 | 1.32e-5 | − 1.60e-5 . | − 4.53e-6 |

| 18 to 34 | − 2.99e-5* | 1.25e-5 | − 1.80e-6 |

| 35 to 65 | 3.41e-5* | 6.51e-5*** | 3.63e-5*** |

| More than 65 | − 4.61e-5* | 2.09e-5 . | 4.14e-5*** |

| Household Annual Income | |||

| Less than $25K | 1.17e-5 | − 1.51e-4*** | − 7.19e-6 |

| $25K to $50K | − 9.44e-6 | 5.52e-6 | − 1.91e-5 . |

| $51K to $75K | − 1.57e-5 | 2.47e-4*** | − 5.24e-5** |

| $76K to $100K | 1.10e-4* | 3.18e-4*** | − 4.96e-5* |

| More than $100K | 2.01e-4*** | 2.35e-5 | − 4.00e-5* |

| R-squared | 0.23 | 0.69 | 0.12 |

Significance codes: 0 “***” 0.001 “**” 0.01 “*” 0.05 “.” 0.1 “ “ 1

In terms of household income diversity all three zoning changes included in the study (SD, HD, and IH) are all positively associated. For housing characteristics such as public housing, levels of vacancy, single housing, and diversity of typologies, they are all positively associated; while ownership levels are negatively associated. In terms of socio-economic characteristics, adults, elderly and high income families are positively associated with income diversity, while the poor and the young are negatively associated. This FE model with zoning changes and the selected control variables explain a great deal of household income diversity demonstrated by the high r-square of the model reaching 0.69.

Finally, for family type diversity, all the zoning strategies included in the model were negatively associated with it. Public housing and housing units were also negatively associated, while diversity of housing typologies and average year of construction were positively associated. In terms of social characteristics, both the share of white and married households was negatively associated with family type diversity. The percentage of the adult population above 35 years old and elderly was positively associated, while all family income groups were negatively associated.

Implications for the practice

The results of this analysis, specifically regarding diversity changes, suggests that NYC is in 2015 more diverse in terms of race and income, and has similar levels of family type diversity compared to 1990. In terms of how zoning changes and other social and housing characteristics relate to these changes, the results are different across the dimensions of diversity. Overall the results of the FE models suggests that zoning changes have more influence on the diversity of household income than on race or family type. This finding is relevant for the practice of urbanism because most of the time practitioners tend to aggregate all the different dimensions of social diversity in their discourses. For instance, visual narratives that support zoning changes often include renderings with people of different races, ages and perceived incomes sharing the same neighborhoods. The findings of this study put into question these visions, as results suggests that changes in the built form are powerful drivers of a diversification of households’ income levels across neighborhoods, but have a complicated effect on other dimensions of social diversity. This suggests that rendering artists perhaps should think twice when choosing photo realistic human figures to illustrate the urban environments resulting from zoning changes. The public may be misled by the assumption that intensification of the built form brings race and family type diversity.

Interestingly, the entropy scores for family type diversity show that actually NYC has a strong mix of family types that has not significantly changed between 1990 and 2015. Results suggest that zoning changes are all negatively associated with family type diversity. Only the variables associated with a diversity of housing typologies and the average year of construction are positively associated with this dimension. This reinforces the Jacobian theories about a diversity of housing options and building ages to contribute to social diversity but suggest that none of the types of zoning changes seem to work towards this end. Therefore, the results of the analysis perhaps suggests that family type diversity is an issue that apparently responds to a more natural evolution of neighborhoods than to public policy or urbanists’ actions.

Race diversity is found to be the most complex of the three diversity dimensions addressed in this study. Across the board NYC is now more diverse in terms of race in 2015 than on 1990. SDs and HDs are positively associated with this change, but these and the control variables explain only about 20 percent of racial diversity changes. This puts into question the argument that zoning changes are, alone, causing racial displacement. Even the variable most commonly associated with urbanists’ theories about diversity, housing typologies diversity, is not significant for race diversity. Other variables not directly associated with urbanism have more impact. Public housing and higher household incomes have a positive influence, while rates of ownership and rate of white population have a negative impact. Perhaps zoning policies could improve race diversity, for instance, with measures to preserve public housing.

In sum, this study shows that changes in the built form have complex and nuanced effects on the different dimensions of social diversity. For race and family type diversity the effects are limited, while specifically for family type, zoning changes may reduce diversity. These results suggests that urbanism education and practice must incorporate a more profound notion of social diversity, while also acknowledging the limits of built form to influence complex social processes. On the other hand, considering gentrification concerns, urbanists should also openly acknowledge that zoning changes induce more diverse levels of household income within neighborhoods. While this empirical study suggests that zoning changes do contribute to gentrification, the debate should focus also on wider changes within urban societies. A better understanding of the complex relation between built form and social processes will help to design new social and economic policies to cope with the social injustices that zoning changes may be causing.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Anderson K 2012. “My Brooklyn.” Documentary. http://www.mybrooklynmovie.com/ [Google Scholar]

- Angotti T, and Marcuse P. 2011. New York for Sale: Community Planning Confronts Global Real Estate. Cambridge, MA: Mit Press. [Google Scholar]

- Apparicio P, Martori JC, Pearson AL, Fournier É, and Apparicio D. 2014. “An Open-Source Software for Calculating Indices of Urban Residential Segregation.” Social Science Computer Review 32 (1): 117–128. doi: 10.1177/0894439313504539. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aquino F, and Gainza X. 2014. “Understanding Density in an Uneven City, Santiago De Chile: Implications for Social and Environmental Sustainability.” Sustainability 9 (6): 5876–5897. doi: 10.3390/su6095876. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bramley G, Dempsey N, Power S, Brown C, and Watkins D. 2009. “Social Sustainability and Urban Form: Evidence from Five British Cities.” Environment and Planning A 41 (9): 2125. doi: 10.1068/a4184. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The Brookings Institution, and Federal Reserve Bank. 2008. The Enduring Challenge of Concentrated Poverty in America: Case Studies from Communities across the US. Richmond, VA: The Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. [Google Scholar]

- Burton E 2000. “The Compact City: Just or Just Compact? A Preliminary Analysis.” Urban Studies 37 (11): 1969–2006. doi: 10.1080/00420980050162184. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Curran W 2007. “‘From the Frying Pan to the Oven’: Gentrification and the Experience of Industrial Displacement in Williamsburg, Brooklyn.” Urban Studies 44 (8): 1427–1440. doi: 10.1080/00420980701373438. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dave S 2011. “Neighbourhood Density and Social Sustainability in Cities of Developing Countries.” Sustainable Development 19 (3): 189–205. doi: 10.1002/sd.433. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellen I, and Turner M. 2003. “‘Do Neighborhoods Matter and Why?’.” In Choosing a Better Life? Evaluating the Moving to Opportunity Social Experiment, edited by Goering J and Feins J, 313–339. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fainstein SS 2010. The Just City. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Florida RL 2002. The Rise of the Creative Class: and How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life. New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Galster G, Cutsinger J, and Malega R. 2008. “The Costs of Concentrated Poverty: Neighborhood Property Markets and the Dynamics of Decline.” In Revisiting Rental Housing: Policies, Programs, and Priorities, edited by Retsinas N and Belsky E, 93–144. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl J 2011. Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space. London: Island Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hackworth J 2001. “Inner-City Real Estate Investment, Gentrification, and Economic Recession in New York City.” Environment and Planning A 33 (5): 863–880. doi: 10.1068/a33160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hackworth J 2002. “Postrecession Gentrification in New York City.” Urban Affairs Review 37 (6): 815–843. doi: 10.1177/107874037006003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iceland J 2004. The Multigroup Entropy Index (Also Known as Theil’s H or the Information Theory Index). College Park, MD: University of Maryland. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs J 1961. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York, NY: Vintage. [Google Scholar]

- King K 2013. “Jane Jacobs and ‘The Need for Aged Buildings’: Neighbourhood Historical Development Pace and Community Social Relations.” Urban Studies 2013 (March): 1–18. doi: 10.1177/0042098013477698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lees L 2003. “Super-Gentrification: The Case of Brooklyn Heights, New York City.” Urban Studies 40 (12): 2487–2509. doi: 10.1080/0042098032000136174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Licea M 2016. “‘Poor Door’ Tenants of Luxury Tower Reveal the Financial Apartheid Within.” January 17. http://nypost.com/2016/01/17/poor-door-tenants-reveal-luxury-towers-financial-apartheid/ [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, and Denton NA. 1988. “The Dimensions of Residential Segregation.” Social Forces 67 (2): 281–315. doi: 10.1093/sf/67.2.281. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro M 2014. “ ‘Poor Door’ in a New York Tower Opens a Fight over Affordable Housing.” The New York Times, August 26, sec. N.Y./Region. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/27/nyregion/separate-entryways-for-new-york-condo-buyers-and-renters-create-an-affordable-housing-dilemma.html [Google Scholar]

- Newman K, and Wyly EK. 2006. “The Right to Stay Put, Revisited: Gentrification and Resistance to Displacement in New York City.” Urban Studies 43 (1): 23–57. doi: 10.1080/00420980500388710. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Osman S. 2011. The Invention of Brownstone Brooklyn: Gentrification Andthe Search for Authenticity in Postwar New York. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pearsall H 2013. “Superfund Me: A Study of Resistance to Gentrification in New York City.” Urban Studies 50 (11): 2293–2310. doi: 10.1177/0042098013478236. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pendall R, and Carruthers JI. 2003. “Does Density Exacerbate Income Segregation? Evidence from US Metropolitan Areas, 1980 to 2000.” Housing Policy Debate 14 (4): 541–589. doi: 10.1080/10511482.2003.9521487. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi A, and Murayama A. 2013. “Changes in the Traditional Urban Form and the Social Sustainability of Contemporary Cities: A Case Study of Iranian Cities.” Habitat International 38 (April): 126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2012.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stabrowski F 2014. “New-Build Gentrification and the Everyday Displacement of Polish Immigrant Tenants in Greenpoint, Brooklyn.” Antipode 46 (3): 794–815. doi: 10.1111/anti.12074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stabrowski F 2015. “Inclusionary Zoning and Exclusionary Development: The Politics of ‘Affordable Housing” in North Brooklyn’.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 39 (6): 1120–1136. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.12297. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sung H, Lee S, and Cheon S. 2015. “Operationalizing Jane Jacobs’s Urban Design Theory Empirical Verification from the Great City of Seoul, Korea.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 35 (February): 117–130. doi: 10.1177/0739456X14568021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- CNU, Talen E 1999. Charter of the New Urbanism. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill Professional. [Google Scholar]

- Talen E 2006. “Neighborhood-Level Social Diversity: Insights from Chicago.” Journal of the American Planning Association 72 (4): 431–446. doi: 10.1080/01944360608976764. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Talen E 2008. Design for Diversity, Exploring Socially Mixed Neighborhoods. Oxford: Architectural Press. [Google Scholar]

- Talen E 2010. “The Context of Diversity: A Study of Six Chicago Neighbourhoods.” Urban Studies 47 (3): 486–513. doi: 10.1177/0042098009349778. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WJ 1990. The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass,And Public Policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zukin S 2009. Naked City: The Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zukin S, Trujillo V, Frase P, Jackson D, Recuber T, and Walker A. 2009. “New Retail Capital and Neighborhood Change: Boutiques and Gentrification in New York City.” City & Community 8(1): 47–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6040.2009.01269.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]