Abstract

Background:

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a component of firefighting foams used at military installations. Although high PFAS exposures have been related to cancer risks among civilian populations, the effects for military personnel are unclear.

Objectives:

We investigated associations between serum PFAS concentrations and testicular germ cell tumors (TGCT) among U.S. Air Force servicemen.

Methods:

This nested case–control study involved active-duty Air Force servicemen with sera from the Department of Defense Serum Repository. We selected 530 cases and 530 controls individually matched on birth date, race and ethnicity, year entered the service, and year of sample collection, with prediagnostic serum samples collected between 1988 and 2017. A second prediagnostic sample, collected a median of 4 y after the first, was selected for 187 case–control pairs. Seven PFAS were quantified using isotope-dilution tandem mass spectrometry. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) from conditional logistic regression adjusting for military grade, number of deployments, and, in some models, other PFAS, estimated associations between PFAS concentrations (categorized using quartiles among controls) and TGCT.

Results:

Elevated concentrations of some PFAS were observed for military employment in firefighting [perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS), perfluorohexanesulfonic acid (PFHxS), perfluorooctanoic acid] and service at a base with high PFAS concentrations in drinking water (PFHxS). Elevated PFOS concentrations in the second sample were positively associated with TGCT [OR for fourth vs. first quartile , 95% CI: 1.1, 6.4; ], including after adjustment for other PFAS (, 95% CI: 1.4, 15.1; ). Associations with PFOS in the first/only samples were weak and not statistically significant. Elevated concentrations of perfluorononanoic acid were inversely associated with TGCT, whereas results were null for other PFAS.

Discussion:

We identified service-related predictors of PFAS concentrations and increased TGCT relative risks with elevated PFOS concentrations among Air Force servicemen. These findings warrant further investigation in other populations and military service branches. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP12603

Introduction

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are manufactured chemicals with useful properties of oil, stain, grease, and water repellency that have been used since the 1940s in the manufacture of firefighting foams, nonstick cookware, and other products.1 PFAS have become widespread food and water contaminants owing to their resistance to degradation and persistence in the environment and are detectable in the serum of most Americans.2 A major source of PFAS water contamination is the use of PFAS-containing aqueous film forming foams (AFFFs) at airports and military installations to extinguish petroleum-based fires.3 The Department of Defense (DoD) possesses the largest amount of AFFF in the United States; its stockpile in 2004 of represented nearly 30% of all domestic AFFF holdings.4 The U.S. Air Force has been using AFFFs containing perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS), perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), and perfluorohexanesulfonic acid (PFHxS) at crash sites and in fire training areas since the late 1960s.5 The Air Force discontinued use of AFFFs containing such long-alkyl chain PFAS in 2018 because of concerns over environmental persistence, contamination of water supplies of surrounding communities, and possible health effects.6 Following a systematic testing of all DoD drinking water systems between June 2016 and August 2017,7 the DoD had identified 401 military bases (including 203 Air Force installations) with a known or suspected release of PFOS/PFOA, including 90 with tested groundwater PFOS/PFOA concentrations exceeding the 2016 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) lifetime health advisory (LHA) of 70 parts per trillion (ppt) and 36 with tested drinking water PFOS/PFOA concentrations exceeding this threshold.8 The extent of exposure to PFAS among military service members themselves, however, is unclear.

There is emerging epidemiological evidence suggesting an association between PFAS and testicular cancer. In 2014, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified PFOA as a possible human carcinogen (Group 2B) on the basis of limited epidemiological evidence of associations with cancers of the kidney and testis and limited evidence in experimental animals.9 No studies to date have directly investigated other PFAS in relation to testicular cancer, although an elevated but statistically nonsignificant relative risk of this malignancy was observed among residents of a community in Sweden exposed to high drinking water concentrations of PFOS and PFHxS due to contamination from AFFF use at a nearby airport.10 Testicular cancer [ of which are testicular germ cell tumors (TGCTs)] is the most frequently diagnosed malignancy among U.S. men age 15–39 y, with incidence rates peaking in this age range, and among U.S. active-duty servicemen.11,12 The etiology of testicular cancer is poorly understood; established risk factors include having an undescended testicle (cryptorchidism), a personal or family history of testicular cancer, and non-Hispanic White race and ethnicity.11 Although the prevailing hypothesis is that in utero exposures are important in determining risk, analyses of age-period-cohort models also implicate postnatal exposures in the etiology of testicular cancer.13 Several occupational and environmental exposures in adolescence and adulthood are suspected risk factors for testicular cancer.11 Notably, several studies have observed elevated rates of testicular cancer among firefighters, who have potential exposure to PFAS through the use of AFFFs.14

Given the lack of evidence regarding PFAS exposure among military personnel and of PFAS associations with testicular cancer in this population, we conducted a nested case–control study within the DoD Serum Repository (DoDSR), investigating serum PFAS concentrations and TGCTs diagnosed among active-duty Air Force servicemen. Our study aims were: a) to describe PFAS serum concentrations among Air Force servicemen, including comparisons with general-population survey data and explorations of potential service-related exposure determinants; and b) to investigate associations between serum concentrations of PFAS (including PFOA) and TGCT.

Methods

Study Design

The DoDSR is a repository for the storage of sera remaining after routine human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing of military personnel conducted at or prior to induction and periodic medical examinations and before and after overseas deployments. Beginning in 2004, a new policy was enacted requiring HIV testing of all service members every 2 y.15,16 Blood collection and serum processing are conducted within service branches following their protocols, with sera shipped to a designated HIV testing center. The length of time from sample collection to HIV testing varies, depending on the site and workload. The remaining serum is transported to the DoDSR, transferred to a new tube and frozen at for long-term storage. The DoD established long-term holdings of frozen human serum specimens in 1985, with separate repositories maintained by each service branch. In 1989, the repositories of the Army and Navy/Marines were physically combined. Air Force serum samples were later added in 1996, marking the official beginning of the DoDSR. It is one of the largest longitudinal serum repositories in the world, containing vials of serum collected from service members. Because the DoDSR is linked to the personnel and health records of service members contained in the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS), it is a unique resource for epidemiological studies of exposures relevant to military populations.15

We identified cases through data linkage between the DoDSR and the DoD Cancer Registry, which records patients diagnosed with and/or treated for cancer at military treatment facilities. We identified 914 cases of TGCT (International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition site code C62 and morphology codes 9060–9062, 9064–9102) diagnosed among Air Force servicemen with no prior history of cancer (excluding nonmelanoma skin cancer) between 1990 and 2018. After excluding cases that were not on active-duty status at diagnosis (), age y at diagnosis (), or with no available prediagnostic samples in the DoDSR (), we identified 530 cases for our study, with samples collected between 1988 and 2017. For the majority of cases (), we selected a single prediagnostic sample (the earliest collected sample) for inclusion in this study. We selected two prediagnostic samples from 187 cases with two or more prediagnostic banked samples that were diagnosed at least 5 y after the earliest sample collection date (i.e., a 5-y exposure lag time for the earliest samples). When such cases had three or more banked prediagnostic samples in storage, we selected the earliest available sample as the first sample and used the following algorithm to select the second sample: a) if there were any remaining prediagnostic samples collected 5 or more years prior to case diagnosis, we selected the prediagnostic sample from this set with the latest collection date; b) if there were no remaining prediagnostic samples collected 5 or more years prior to case diagnosis, we selected the prediagnostic sample with the earliest collection date. This algorithm thus selected second samples as close as possible to the time point of 5 y before the case diagnosis date. Our motivation for this approach was to select samples collected at a later period of follow-up than the first samples, but preferably not within 5 y prior to diagnosis, which we speculated may be a less etiologically relevant time window. The study was determined by the Uniformed Services University’s Human Research Protections Program (HRPP) Office to be considered research not involving human subjects because of the de-identification of samples and data. Similarly, the involvement of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S. CDC) laboratory did not constitute engagement in human subjects research.

We used risk set sampling with replacement to individually match one control per case from among Air Force servicemen who were on active duty and cancer-free as of the case diagnosis date. Matching criteria include date of birth ( y), self-reported race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic White persons, Hispanic persons, non-Hispanic Black persons, Asian/Pacific Islander persons, Native American/Alaskan Native persons, other), year entered military service ( y), availability in the DoDSR of a sample collected in the same year as that of the baseline case sample ( y) and, if applicable, availability of a sample collected in the same year as that of the later selected case sample ( y). The categories of race and ethnicity are those provided by the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division (AFHSD). We included race and ethnicity as a matching factor in the study design because of its potential to introduce confounding, given evidence of differences across groups in serum PFAS concentrations and TGCT incidence.2,11

We also received from the AFHSD the following service-related data from subjects’ personnel records contained in the DMSS: military grade at the time of the case diagnosis (enlisted, officer), the year military service began, the number of military deployments prior to case diagnosis (0, 1, ), and Air Force Specialty Codes (AFSCs, designating Air Force occupations) prior to serum collection and case diagnosis. The AFHSD also used the reported results of the DoD water testing initiative (testing all DoD drinking water systems for PFOA and PFOS concentrations between June 2016 and August 2017)7,8 to create variables indicating whether, prior to sample collection and diagnosis, subjects had been stationed at an Air Force facility identified through the initiative as having drinking water or groundwater samples exceeding the 2016 U.S. EPA LHA.

Laboratory Analysis

Serum concentrations of nine PFAS [2-(N-methyl-perfluorooctane sulfonamido) acetic acid (MeFOSAA), perfluorohexanesulfonic acid (PFHxS), perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA), perfluorodecanoic acid (PFDA), perfluoroundecanoic acid (PFUnDA), sum of perfluoromethylheptanoic acids (branched PFOS isomers; Sm-PFOS), linear PFOS (n-PFOS), linear PFOA (n-PFOA), and sum of branched perfluorooctanoic acids (Sb-PFOA)] were measured at the U.S. CDC’s Division of Laboratory Sciences (Atlanta, Georgia) between June 2021 and February 2022 using online solid-phase extraction coupled to reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography–isotope dilution tandem mass spectrometry, as described previously,17 with all samples from matched case–control pairs analyzed consecutively in the same batch. We inserted into each batch four quality control (QC) replicate samples (103 total) from a serum pool created using other DoDSR samples to evaluate method performance. The order of each QC sample within a given batch was randomly assigned, with the constraint that they not interrupt the sequence of samples from a matched case–control pair. Method reproducibility was acceptable, with median within-batch and total coefficients of variation (CVs) of 10.8% (range: 7.9%–13.5%) and 13.2% (range: 10.5%–27.2%) across analytes. The CVs and proportion of detectable measurements for each PFAS in the QC pool are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. Method performance was confirmed by successful participation in three proficiency testing rounds of the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Program (AMAP; https://www.inspq.qc.ca/en/ctq/eqas/amap/description) between June 2020 and January 2021. The limit of detection (LOD) was for all analytes; concentrations below the LOD were assigned a value of one-half the LOD ().18 We calculated the concentrations of total PFOA and total PFOS by adding together the concentrations of the linear and branched isomers. We included total PFOS, total PFOA, and the five other measured PFAS (i.e., seven PFAS in total) in the data analysis.

Statistical Analyses

Using univariate statistics, we compared cases and controls with regard to selected personal and service-related characteristics, extracted by the AFHSD from records in the DMSS. We calculated Spearman rank correlations between measured PFAS and used principal component analysis (PCA) of PFAS transformed by the natural logarithm to identify a limited number of orthogonal linear combinations that explained the majority of the total variance. To summarize the distributions of serum PFAS concentrations among study subjects, we calculated least squares geometric means from multiple linear regression models of serum PFAS concentrations transformed by the natural logarithm. First, we compared PFAS least squares geometric means of first/only samples from study controls vs. serum PFAS measurements (total PFOS, total PFOA, PFHxS, MeFOSAA, PFNA, PFDA, and PFUnDA) from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) male participants age 18–39 y separately for sera collected in selected time periods (1999–2000, 2003–2004, 2005–2006, 2007–2008, 2009–2010)19 by fitting linear regression models of log-transformed PFAS concentrations accounting for complex survey data using the SAS SURVEYREG procedure, adjusting for age group (, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, and 35–39 y) and race and ethnicity [dichotomized to non-Hispanic White and Other (non-Hispanic Black, Mexican American, Other Hispanic, Other/Multi-Racial) given sparse data for non-White racial/ethnic groups] as model covariates. We did not include 2001–2002 NHANES data because PFAS quantitation had been conducted on pooled samples, not individually for subjects, and NHANES data for more recent years were not included because of the smaller numbers of study samples collected in these time periods. For these analyses, sampling weights of NHANES subjects were rescaled to sum to the sample size of the NHANES PFAS data set, whereas study controls were assigned sampling weights of 1, individual unique primary sampling units, and a single common sampling stratum. Both the DoDSR study samples and the NHANES samples were analyzed by the same U.S. CDC laboratory.

We then investigated potential predictors of serum PFAS concentrations among Air Force servicemen by fitting multiple linear regression models of log-transformed PFAS concentration with the following categorical variables included in each model: sample collection year (before 1996 , 1996–1998, 1999–2004, after 2005), age group at serum collection (same categories as before), race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, Other), education level (, some college, bachelor’s degree, advanced degree), military grade (E01–E10, O1–O10), number of years of service at serum collection (, 1 to , y), military occupation in fire protection (AFSC 3E7X1) prior to serum collection (Yes, No), history of service prior to serum collection at an Air Force facility with PFOS/PFOA levels in drinking water samples exceeding the 2016 U.S. EPA LHA (Yes, No), and history of service prior to serum collection at an Air Force facility with PFOS/PFOA levels in groundwater samples above the LHA (Yes, No). These analyses were conducted using samples collected after the start of military service, both for all subjects (additionally adjusting for case–control status) and then restricted to controls. As a sensitivity analysis, we reran these models restricting to case and control samples collected y after the start of military service (the median among cases), and modeling separately the variables indicating history of service at a facility with high drinking water PFOS/PFOA and history of service at a facility with high groundwater PFOS/PFOA. We also ran models to investigate predictors of identified PFAS principal components.

For the case–control analysis, we categorized PFAS concentrations using quartiles among controls as cut points, separately for baseline and second samples. We computed odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) relating PFAS categories with TGCT through conditional logistic regression of matched pairs. We ran unadjusted models (conditioned on the matched sets), models adjusted for military grade (categorized as before) and number of military deployments prior to case diagnosis (categorized 0, 1, ), which we observed to differ between cases and controls (Table 1), and models additionally adjusted for the six other PFAS included in the data analysis (categorized in the same manner as the PFAS of interest). We conducted Wald tests for trend across PFAS categories by modeling the intracategory medians as a continuous parameter. Within the subset of participants with two samples, we conducted an analysis comparing between cases and controls the combinations of dichotomized PFAS concentrations (using controls’ medians as cut points) in both the first and second samples; participants with a given PFAS concentration below the median for both samples were used as the reference group. We conducted sensitivity analyses for our investigations of PFOA, PFOS, and PFHxS (high-priority chemicals given their presence in AFFFs and, for PFOA, prior evidence of association with testicular cancer)5,9 as well as PFNA (given observed associations with TGCT in our data). For these PFAS we reran the aforementioned case–control logistic models restricting to matched sets with case samples collected y after the start of military service, ran models without adjustment for military grade or number of military deployments, and conducted analyses categorizing the measured PFAS concentrations using the same cut points for each sample type (the second-sample quartiles among controls). We also investigated case–control associations with identified PFAS principal components (categorized using quartiles among controls) in first/only and second samples using logistic regression models adjusted for military grade and number of deployments.

Table 1.

Summary of selected characteristics among participants in a nested case–control study of serum PFAS and testicular germ cell tumors among U.S. Air Force servicemen, both overall (530 matched pairs) and for the subset with two prediagnostic serum samples (187 matched pairs).

| All participants | Subset of participants with two samples | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | -Value | Cases | Controls | -Value | |

| Age (y) at first serum collection [ (%)] | — | — | 0.41 | — | — | 0.55 |

| 141 (26.6) | 134 (25.3) | — | 60 (32.1) | 58 (31.0) | — | |

| 20–24 | 194 (36.6) | 220 (41.5) | — | 75 (40.1) | 88 (47.1) | — |

| 25–29 | 95 (17.9) | 76 (14.3) | — | 37 (19.8) | 26 (13.9) | — |

| 30–34 | 64 (12.1) | 66 (12.5) | — | 11 (5.9) | 12 (6.4) | — |

| 35–39 | 36 (6.8) | 34 (6.4) | — | 4 (2.1) | 3 (1.6) | — |

| Age (y) at second serum collection [ (%)] | ||||||

| NA | NA | — | 58 (31.0) | 62 (33.2) | 0.98 | |

| 20–24 | NA | NA | — | 55 (29.4) | 55 (29.4) | — |

| 25–29 | NA | NA | — | 45 (24.1) | 42 (22.5) | — |

| 30–34 | NA | NA | — | 18 (9.6) | 19 (10.2) | — |

| 35–39 | NA | NA | — | 11 (5.9) | 9 (4.8) | — |

| Age (y) at case diagnosis [ (%)]a | — | — | 1.00 | — | — | 1.00 |

| 10 (1.9) | 10 (1.9) | — | 0 | 0 | — | |

| 20–24 | 111 (20.9) | 111 (20.9) | — | 4 (2.1) | 4 (2.1) | — |

| 25–29 | 159 (30.0) | 159 (30.0) | — | 54 (28.9) | 54 (28.9) | — |

| 30–34 | 113 (21.3) | 113 (21.3) | — | 58 (31.0) | 58 (31.0) | — |

| 35–39 | 137 (25.9) | 137 (25.9) | — | 71 (38.0) | 71 (38.0) | — |

| Race and ethnicity [ (%)]a | — | — | 1.00 | — | — | 1.00 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 422 (79.6) | 422 (79.6) | — | 146 (78.1) | 146 (78.1) | — |

| Hispanic | 57 (10.8) | 57 (10.8) | — | 26 (13.9) | 26 (13.9) | — |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 13 (2.5) | 13 (2.5) | — | 3 (1.6) | 3 (1.6) | — |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 6 (1.1) | 6 (1.1) | — | 4 (2.1) | 4 (2.1) | — |

| Native American/Alaskan Native | 5 (0.9) | 5 (0.9) | — | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | — |

| Other/unknown | 27 (5.1) | 27 (5.1) | — | 8 (4.3) | 8 (4.3) | — |

| Education [ (%)] | — | — | 0.26 | — | — | 0.55 |

| 261 (49.3) | 268 (50.6) | — | 82 (43.9) | 88 (47.1) | — | |

| Some college | 120 (22.6) | 138 (26.0) | — | 55 (29.4) | 51 (27.3) | — |

| Bachelor’s degree | 80 (15.1) | 57 (10.8) | — | 18 (9.6) | 17 (9.1) | — |

| Advanced degree | 68 (12.8) | 66 (12.5) | — | 32 (17.1) | 31 (16.6) | — |

| Unknown | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | — | 0 | 0 | — |

| Grade | — | — | 0.06 | — | — | 0.20 |

| E01–E10 (Enlisted) | 410 (77.4) | 435 (82.1) | — | 143 (76.5) | 153 (81.8) | — |

| O01–O10 (Officer) | 120 (22.6) | 95 (17.9) | — | 44 (23.5) | 34 (18.2) | — |

| Number of military deployments | — | — | — | — | 0.23 | |

| 0 | 296 (55.9) | 222 (41.9) | — | 64 (34.2) | 52 (27.8) | — |

| 1 | 114 (21.5) | 121 (22.8) | — | 47 (25.1) | 43 (23.0) | — |

| 120 (22.6) | 187 (35.3) | — | 76 (40.6) | 92 (49.2) | — | |

| Calendar year started military service [median (min, max)]a | 1998 (1986, 2017) | 1998 (1986, 2017) | 0.95 | 1998 (1986, 2012) | 1998 (1986, 2012) | 0.98 |

| Calendar year of sample collection [median (min, max)]a | ||||||

| First/only sample | 1999 (1988, 2017) | 1999 (1989, 2017) | 0.99 | 1999 (1989, 2012) | 1999 (1989, 2012) | 0.98 |

| Second sample | NA | NA | — | 2005 (1991, 2012) | 2005 (1992, 2013) | 0.97 |

| Years of service at sample collection [median (min, max)] | ||||||

| First/only sample | 0.3 (, 12.3)b | 0.4 (, 12.3)b | 0.49 | 0.3 (, 12.1)b | 0.4 (, 12.3)b | 0.64 |

| Second sample | NA | NA | — | 5.8 (, 21.8)b | 5.8 (, 25.0)b | 0.90 |

| Years from sample collection to case diagnosis [median (min, max)] | ||||||

| First/only sample | 5.0 (0.0, 19.8) | NA | — | 10.3 (5.0, 19.8) | NA | — |

| Second sample | NA | NA | — | 5.8 (4.8, 11.5) | NA | — |

| Tumor morphology [ (%)] | ||||||

| Seminoma | 300 (56.6) | NA | — | 125 (66.8) | NA | — |

| Nonseminoma | 230 (43.4) | NA | — | 62 (33.2) | NA | — |

Note: —, no data; max, maximum; min, minimum; NA, not applicable; PFAS, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances.

Control matching factor.

Negative values represent serum collection dates prior to the military service start date (cases: 115 first/only samples, 6 second samples; controls: 99 first/only samples, 5 second samples).

In addition, we conducted analyses of dichotomized PFAS categories (categorized using the median among controls) stratifying on selected categorical variables (race and ethnicity, year of sample collection, years of service at sample collection) and tested for multiplicative interaction using cross-product terms in conditional models, also adjusted for military grade and number of military deployments (categorized as before). Given the differences between first/only and second samples in the distributions of some stratification variables (e.g., year of sample collection, years of service at sample collection), cut points were selected with consideration to minimize instances of sparse participant counts within strata. We also conducted separate analyses across levels of cancer-related categorical variables (years from sample collection to case diagnosis, histological subtype). For these analyses we tested for OR heterogeneity across levels of each case characteristic by first creating a variable assigning to each matched case–control pair the characteristic of that case (e.g., defining matched pairs as “seminoma” or “nonseminoma”) and then testing for interaction with this variable in a conditional model using a cross-product term. We also conducted analyses to assess the possibility that the association between military occupation as a firefighter and TGCT is at least partially mediated through PFOS effects.20 To do so, we computed TGCT associations with military occupation as a firefighter prior to case diagnosis (Yes, No) among subjects with two samples, both with adjustment for categorized serum PFOS concentration (quartiles) in the second sample (this sample, given its timing, is likely more representative of PFOS exposure related to military firefighting) and without PFOS adjustment. We visually compared the ORs to assess whether the association between firefighting and TGCT weakened with adjustment for serum PFOS, which would be compatible with at least some of the firefighting–TGCT association being explained by PFOS effects.

All analyses were conducted using SAS (version 9.4;SAS Institute Inc.). All statistical tests were two-sided, with an alpha level of 0.05.

Results

Selected characteristics of cases and controls (both overall and restricted to men with two banked samples) are summarized in Table 1. Overall, the majority of subjects were y of age at the date of the first/only serum collection, y of age at case diagnosis, and of non-Hispanic White race and ethnicity. Nearly half of the subjects had high school as their highest education level. Cases and controls did not differ by age, race and ethnicity, or education level; however, cases were slightly more likely than controls to have a military grade of officer () and significantly less likely to have had overseas military deployments (). Similar patterns of subject characteristics were observed for the subset of cases and controls with two serum samples (involving cases diagnosed at least 5 y after the earliest sample collection date), with the exception of an older age at case diagnosis (69% y of age). The DoDSR serum samples selected for this study were originally collected between 1988 and 2017. The median collection year for first/only serum samples was 1999, and these samples had usually been collected within a few months after subjects had started military service (median 0.3 and 0.4 y for cases and controls, respectively). The second banked serum samples were usually collected several years after the first samples (median 4 y, ranging from 0.1 to 13.3 y), with a median of 5.8 y of military service at collection. The number of years from first/only sample collection to case diagnosis ranged from 0 to 20 y, and the majority of TGCTs were seminomas, particularly among the subset of cases with two samples; this is expected given that the average age at diagnosis is higher than for nonseminoma.11

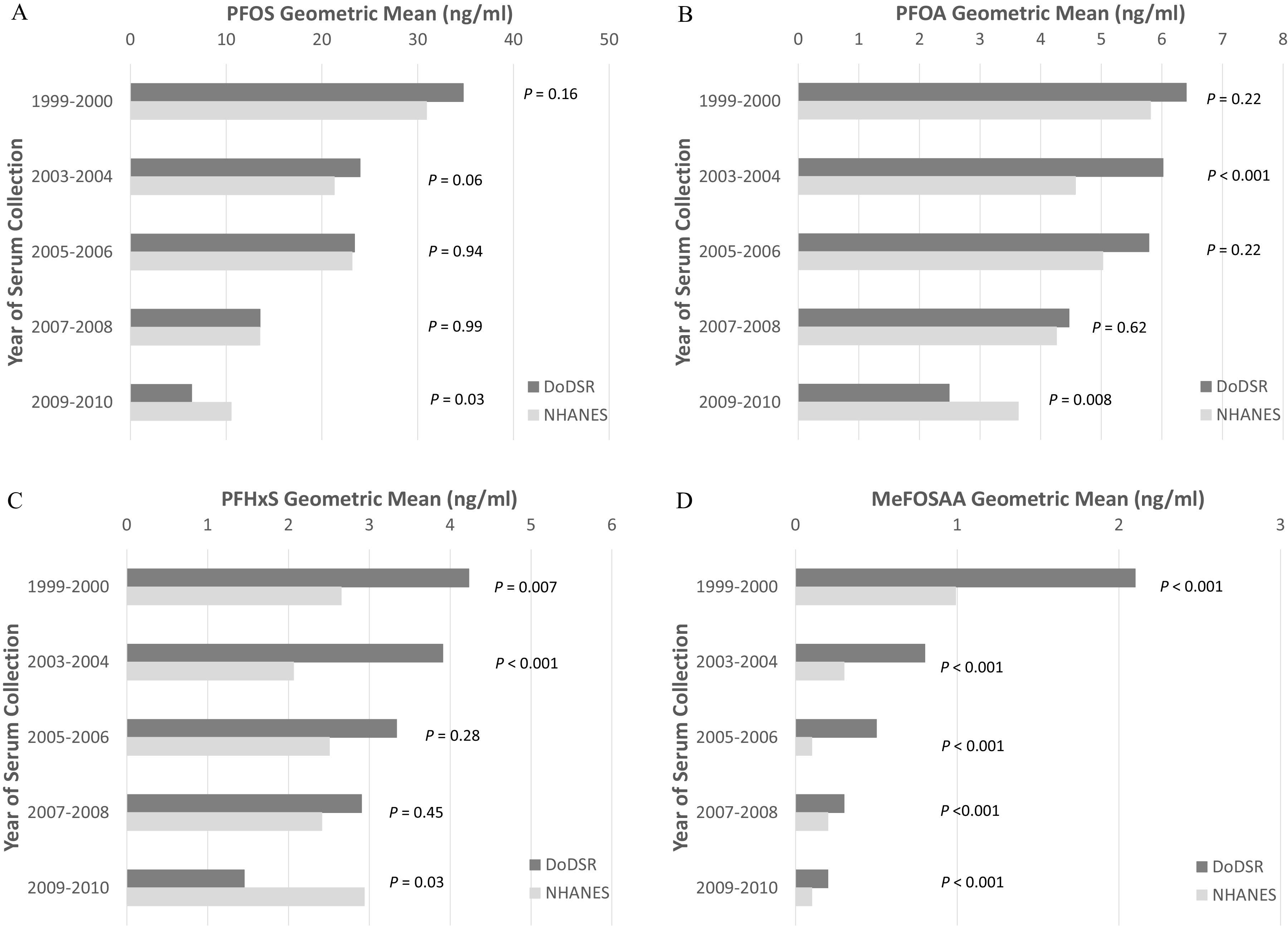

When we summarized the geometric mean serum concentrations of the measured PFAS among study controls and NHANES male participants age 18–39 y for samples collected in the same time periods, we observed concentrations of PFOS, PFOA, PFHxS, and MeFOSAA to be generally lower in later time periods in both populations (Figure 1; Supplementary Table 2). Concentrations of these PFAS were higher in study controls vs. NHANES for samples collected in 1999–2000, 2003–2004, 2005–2006 and 2007–2008 (particularly for PFHxS and MeFOSAA), whereas for samples collected in 2009–2010, the opposite pattern was usually observed. Serum concentrations of PFNA, PFDA, and PFUnDA were lower than those of the other PFAS and remained stable or increased slightly over time in both populations (Supplementary Table 2). We observed evidence of elevated concentrations of these three PFAS in study controls vs. NHANES for samples collected in 2005–2006 and/or 2007–2008. Among controls, we observed two distinct clusters of PFAS correlated with one another: a) PFOS, PFOA, PFHxS, and MeFOSAA in one cluster and b) PFNA, PFDA, and PFUnDA in the other (Supplementary Table 3). Using PCA, we identified two principal components (PCs) that account for of the total variance across measured PFAS (Supplementary Table 3). The compositions of these PCs were similar to the clusters observed in the correlation matrix; the first PC (PC1) loaded strongly onto concentrations of PFOS, PFOA, PFHxS, and MeFOSAA, whereas the second PC (PC2) loaded predominantly onto the other PFAS.

Figure 1.

Comparisons of geometric mean serum concentrations (ng/mL) of selected PFAS in DoDSR Air Force study controls (first/only sample) vs. male participants age 18–39 y in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) for samples collected in 1999–2000 (controls, ; NHANES, ), 2003–2004 (controls, ; NHANES, ), 2005–2006 (controls, ; NHANES, ), 2007–2008 (controls, ; NHANES, ), and 2009–2010 (controls, ; NHANES, ). (A) PFOS; (B) PFOA; (C) PFHxS; (D) MeFOSAA. -Values are from Wilcoxon rank sum tests of difference in PFAS concentration between populations for a given sample collection period. The estimated geometric means of all seven evaluated PFAS in study controls and NHANES data are provided in Supplementary Table 2. Note: DoDSR, Department of Defense Serum Repository; MeFOSAA, 2-(N-methyl-perfluorooctane sulfonamido) acetic acid; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; PFHxS, perfluorohexanesulfonic acid; PFOA, perfluorooctanoic acid; PFOS, perfluorooctanesulfonic acid.

Table 2 summarizes least squares geometric mean serum concentrations of PFOS, PFOA, and PFHxS (known AFFF-related PFAS of a priori interest) in relation to select subject and sample characteristics for samples collected after the start of military service. PFAS concentrations were strongly associated with year of sample collection; the highest concentrations of PFOS and PFHxS were observed for samples collected between 1996 and 1998, whereas for PFOA the peak concentrations were among samples from 1999 to 2004. Concentrations dropped sharply for all three PFAS after 2004. Higher concentrations were also associated with several demographic characteristics, including older age at serum collection and non-Hispanic White race and ethnicity (particularly for second samples). The strongest predictor of PFAS concentrations observed among service-related factors was having a military occupation in fire protection prior to serum collection; servicemen in this occupation had substantially higher concentrations of PFOS, PFOA, and PFHxS in the first/only samples in comparison with other servicemen, including approximately 2-fold higher concentrations of PFOS (least squares geometric means 64.8 vs. ) and 3-fold higher concentrations of PFHxS (14.4 vs. ). Similar findings were observed in an analysis of the second samples (Table 3).

Table 2.

Least squares geometric mean concentrations of PFOS, PFOA, and PFHxS (ng/mL) in relation to subject and sample characteristics for samples collected after start of military service among active-duty U.S. Air Force servicemen ().

| First/only sample () | Second sample () | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFOS | PFOA | PFHxS | PFOS | PFOA | PFHxS | |||||||||

| GMa (95% CI) | -Value | GMa (95% CI) | -Value | GMa (95% CI) | -Value | GMa (95% CI) | -Value | GMa (95% CI) | -Value | GMa (95% CI) | -Value | |||

| Year serum collected | ||||||||||||||

| 33 | 51.9 (37.5, 71.8) | 0.11 | 7.4 (5.6, 10.0) | 0.10 | 5.5 (3.1, 9.9) | 0.008 | 3 | 50.2 (27.1, 92.9) | 0.73 | 5.9 (3.6, 9.8) | 0.25 | 4.4 (1.7, 11.5) | 0.05 | |

| 1996–1998 | 313 | 60.5 (46.0, 79.6) | — | 8.6 (6.7, 11.0) | — | 9.8 (6.0, 15.9) | — | 34 | 55.7 (41.0, 75.6) | — | 7.9 (6.1, 10.1) | — | 11.1 (6.9, 17.8) | — |

| 1999–2004 | 264 | 52.7 (39.9, 69.7) | 0.002 | 9.6 (7.4, 12.3) | 0.007 | 9.4 (5.7, 15.4) | 0.64 | 136 | 43.4 (32.9, 57.3) | 0.009 | 8.2 (6.6, 10.3) | 0.56 | 9.0 (5.8, 13.8) | 0.15 |

| 220 | 23.0 (17.3, 30.5) | 5.4 (4.2, 6.9) | 7.6 (4.6, 12.6) | 0.01 | 189 | 19.2 (14.7, 25.2) | 5.3 (4.2, 6.6) | 5.8 (3.8, 8.9) | ||||||

| Age (y) at serum collection | ||||||||||||||

| 173 | 37.7 (28.0, 50.7) | 0.20 | 6.7 (5.1, 8.7) | 0.02 | 5.7 (3.4, 9.7) | 0.16 | 15 | 36.8 (25.2, 53.7) | 0.72 | 5.7 (4.2, 7.8) | 0.35 | 7.5 (4.1, 13.5) | 0.37 | |

| 20–24 | 301 | 40.3 (30.4, 53.4) | — | 7.4 (5.8, 9.6) | — | 6.5 (3.9, 10.7) | — | 114 | 34.8 (25.3, 47.8) | — | 6.5 (5.0, 8.4) | — | 6.0 (3.7, 9.9) | — |

| 25–29 | 160 | 44.2 (33.3, 58.8) | 0.11 | 7.8 (6.0, 10.0) | 0.40 | 8.1 (4.9, 13.4) | 0.03 | 109 | 37.9 (27.5, 52.2) | 0.32 | 7.3 (5.6, 9.5) | 0.09 | 6.7 (4.0, 11.0) | 0.46 |

| 30–34 | 126 | 50.5 (37.7, 67.7) | 0.004 | 8.3 (6.4, 10.8) | 0.12 | 9.8 (5.8, 16.5) | 0.003 | 87 | 38.5 (27.7, 53.5) | 0.33 | 7.0 (5.3, 9.1) | 0.39 | 6.6 (3.9, 11.0) | 0.59 |

| 70 | 49.4 (36.5, 67.0) | 0.03 | 7.8 (5.9, 10.2) | 0.61 | 10.4 (6.0, 17.8) | 0.005 | 37 | 48.9 (34.4, 69.6) | 0.005 | 7.2 (5.4, 9.7) | 0.26 | 9.1 (5.2, 15.8) | 0.03 | |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 658 | 44.8 (34.0, 59.0) | — | 8.0 (6.2, 10.2) | — | 8.4 (5.2, 13.7) | — | 284 | 42.2 (31.5, 56.5) | — | 7.4 (5.8, 9.4) | — | 8.3 (5.3, 13.2) | — |

| Other | 172 | 43.5 (32.8, 57.7) | 0.49 | 7.2 (5.6, 9.3) | 0.009 | 7.4 (4.5, 12.2) | 0.08 | 78 | 36.2 (26.4, 49.6) | 0.02 | 6.1 (4.7, 7.9) | 0.0002 | 6.0 (3.7, 9.8) | 0.001 |

| Education | ||||||||||||||

| 387 | 44.1 (34.0, 57.1) | — | 7.5 (6.0, 9.5) | — | 10.2 (6.4, 16.1) | — | 159 | 42.2 (30.3, 58.7) | — | 7.1 (5.4, 9.3) | — | 7.4 (4.4, 12.4) | — | |

| Some college | 200 | 44.7 (34.5, 58.0) | 0.76 | 7.2 (5.7, 9.1) | 0.30 | 9.7 (6.1, 15.4) | 0.61 | 105 | 38.5 (27.6, 53.8) | 0.14 | 6.6 (5.0, 8.6) | 0.12 | 6.9 (4.1, 11.7) | 0.50 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 117 | 39.0 (30.4, 50.1) | 0.12 | 6.6 (5.3, 8.3) | 0.07 | 8.0 (5.1, 12.5) | 0.09 | 35 | 39.5 (28.5, 54.8) | 0.58 | 6.9 (5.3, 9.0) | 0.74 | 7.2 (4.3, 12.0) | 0.87 |

| Advanced degree | 124 | 40.1 (31.1, 51.7) | 0.32 | 7.0 (5.5, 8.8) | 0.37 | 7.3 (4.6, 11.4) | 0.05 | 63 | 36.4 (26.5, 49.9) | 0.25 | 6.3 (4.9, 8.2) | 0.27 | 6.8 (4.2, 11.2) | 0.69 |

| Grade | ||||||||||||||

| E01–10 (Enlisted) | 633 | 44.2 (33.6, 58.3) | — | 7.6 (6.0, 9.8) | — | 7.4 (4.6, 12.2) | — | 284 | 40.7 (29.9, 55.3) | — | 7.0 (5.4, 8.9) | — | 7.3 (4.5, 11.7) | — |

| O1–O10 (Officer) | 197 | 44.1 (32.7, 59.4) | 0.96 | 7.5 (5.7, 9.8) | 0.82 | 8.4 (4.9, 14.2) | 0.43 | 78 | 37.6 (27.1, 52.2) | 0.50 | 6.5 (5.0, 8.5) | 0.46 | 6.9 (4.1, 11.6) | 0.79 |

| Years of service at serum collection | ||||||||||||||

| 403 | 40.3 (30.3, 53.5) | — | 7.6 (5.9, 9.8) | — | 7.2 (4.4, 12.0) | — | 17 | 37.3 (25.1, 55.4) | — | 6.7 (4.8, 9.2) | — | 5.6 (3.0, 10.4) | — | |

| 171 | 43.7 (32.8, 58.1) | 0.13 | 7.5 (5.8, 9.7) | 0.78 | 7.0 (4.2, 11.6) | 0.69 | 137 | 39.7 (29.6, 53.2) | 0.67 | 6.9 (5.4, 8.8) | 0.77 | 7.6 (4.8, 12.0) | 0.19 | |

| 256 | 49.0 (36.8, 65.2) | 0.01 | 7.6 (5.9, 9.9) | 0.90 | 9.7 (5.9, 16.2) | 0.03 | 208 | 40.4 (29.8, 54.7) | 0.63 | 6.5 (5.1, 8.4) | 0.87 | 8.3 (5.2, 13.4) | 0.12 | |

| Military occupation: fire protection | ||||||||||||||

| No | 825 | 30.1 (25.2, 36.0) | — | 5.8 (4.9, 6.8) | — | 4.3 (3.1, 5.9) | — | 357 | 26.6 (21.8, 32.6) | — | 5.3 (4.5, 6.2) | — | 4.3 (3.1, 5.8) | — |

| Yes | 5 | 64.8 (40.7, 103.1) | 0.0006 | 9.9 (6.5, 15.0) | 0.009 | 14.4 (6.3, 32.9) | 0.002 | 5 | 57.4 (35.6, 92.7) | 0.0005 | 8.5 (5.7, 12.6) | 0.009 | 11.8 (5.6, 24.9) | 0.003 |

| Stationed at facility with elevated PFAS in drinking water | ||||||||||||||

| No | 804 | 43.5 (33.4, 56.8) | — | 7.5 (5.9, 9.6) | — | 6.8 (4.2, 10.9) | — | 342 | 39.3 (29.8, 51.7) | — | 6.4 (5.1, 8.0) | — | 5.4 (3.5, 8.3) | — |

| Yes | 26 | 44.8 (32.6, 61.5) | 0.77 | 7.6 (5.7, 10.1) | 0.90 | 9.2 (5.2, 16.1) | 0.10 | 20 | 38.9 (27.3, 55.6) | 0.94 | 7.0 (5.2, 9.4) | 0.35 | 9.3 (5.3, 16.2) | 0.003 |

| Stationed at facility with elevated PFAS in groundwater | ||||||||||||||

| No | 235 | 46.0 (34.8, 60.7) | — | 7.8 (6.1, 10.0) | — | 8.5 (5.2, 14.0) | — | 50 | 38.3 (27.9, 52.6) | — | 6.8 (5.2, 8.8) | — | 7.0 (4.3, 11.5) | — |

| Yes | 595 | 42.4 (32.1, 56.1) | 0.06 | 7.4 (5.7, 9.5) | 0.15 | 7.3 (4.4, 12.0) | 0.04 | 312 | 39.9 (29.6, 53.9) | 0.61 | 6.6 (5.2, 8.5) | 0.77 | 7.1 (4.5, 11.4) | 0.91 |

Note: —, no data; CI, confidence interval; GM, geometric mean; PFAS, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances; PFHxS, perfluorohexanesulfonic acid; PFOA, perfluorooctanoic acid; PFOS, perfluorooctanesulfonic acid.

Least-squares geometric means computed from multiple linear regression models adjusting for all variables listed in the table and case–control status.

Table 3.

Case–control analysis investigating the association between serum prediagnostic concentrations of PFOS, PFOA, PFHxS, and PFNA (categorized using quartiles among controls as cut points) and testicular germ cell tumors among active-duty U.S. Air Force servicemen (530 cases, 530 controls).

| PFOS | PFOA | PFHxS | PFNA | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration (ng/mL) | a (95% CI) | b (95% CI) | Concentration (ng/mL) | a (95% CI) | b (95% CI) | Concentration (ng/mL) | a (95% CI) | b (95% CI) | Concentration (ng/mL) | a (95% CI) | b (95% CI) | ||||

| All subjects | |||||||||||||||

| First/only sample | |||||||||||||||

| 131/133 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 161/139 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 129/138 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 177/156 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| 18.4–29.3 | 116/135 | 1.0 (0.6, 1.5) | 1.2 (0.7, 1.9) | 4.46–5.87 | 115/126 | 0.7 (0.4, 1.0) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.0) | 2.2–3.6 | 118/133 | 1.0 (0.7, 1.4) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.4) | 0.7–0.9 | 172/151 | 0.9 (0.6, 1.2) | 0.8 (0.5, 1.2) |

| 29.4–42.2 | 153/131 | 1.4 (0.8, 2.3) | 1.9 (1.0, 3.4) | 5.88–7.85 | 121/137 | 0.7 (0.5, 1.0) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.1) | 3.7–7.0 | 146/128 | 1.2 (0.8, 1.7) | 1.2 (0.8, 1.8) | 1.0–1.2 | 91/101 | 0.7 (0.5, 1.0) | 0.6 (0.4, 1.0) |

| 130/131 | 1.2 (0.7, 2.0) | 1.8 (0.9, 3.6) | 133/128 | 0.8 (0.5, 1.2) | 0.8 (0.5, 1.4) | 137/131 | 1.1 (0.8, 1.6) | 1.1 (0.7, 1.7) | 90/122 | 0.5 (0.3, 0.8) | 0.4 (0.2, 0.7) | ||||

| — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||||||||

| Subjects with two samples | |||||||||||||||

| First sample | |||||||||||||||

| 29/33 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 46/35 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 44/40 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 60/62 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| 18.4–29.3 | 49/54 | 1.1 (0.6, 2.2) | 1.2 (0.5, 2.5) | 4.46–5.87 | 46/58 | 0.6 (0.3, 1.0) | 0.6 (0.3, 1.2) | 2.2–3.6 | 47/49 | 0.9 (0.5, 1.6) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.5) | 0.7–0.9 | 71/52 | 1.4 (0.8, 2.4) | 1.0 (0.5, 1.9) |

| 29.4–42.2 | 65/61 | 1.5 (0.7, 3.1) | 1.6 (0.6, 4.0) | 5.88–7.85 | 47/52 | 0.7 (0.3, 1.3) | 0.8 (0.3, 1.8) | 3.7–7.0 | 50/52 | 0.8 (0.4, 1.7) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.8) | 1.0–1.2 | 24/35 | 0.7 (0.4, 1.4) | 0.4 (0.2, 1.1) |

| 44/39 | 1.6 (0.7, 3.6) | 2.0 (0.6, 6.4) | 48/42 | 0.9 (0.5, 1.8) | 1.0 (0.4, 2.7) | 46/46 | 0.9 (0.5, 1.8) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.8) | 32/38 | 0.8 (0.4, 1.8) | 0.4 (0.1, 1.3) | ||||

| — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||||||||

| Second sample | |||||||||||||||

| 42/48 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 55/48 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 48/49 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 44/40 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| 13.3–21.2 | 38/46 | 1.1 (0.6, 1.9) | 1.5 (0.7, 3.3) | 4.26–5.65 | 52/46 | 1.0 (0.6, 1.8) | 1.0 (0.5, 2.0) | 2.4–3.7 | 42/46 | 1.1 (0.5, 2.1) | 1.1 (0.5, 2.4) | 0.8–1.0 | 47/49 | 0.9 (0.5, 1.7) | 0.6 (0.3, 1.5) |

| 21.3–33.5 | 50/47 | 1.9 (0.9, 4.1) | 2.8 (1.1, 7.0) | 5.66–7.55 | 39/49 | 0.7 (0.4, 1.4) | 0.6 (0.3, 1.4) | 3.8–6.2 | 41/46 | 1.0 (0.5, 1.9) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.6) | 1.1–1.5 | 50/52 | 0.7 (0.4, 1.5) | 0.3 (0.1, 0.9) |

| 57/46 | 2.6 (1.1, 6.4) | 4.6 (1.4, 15.1) | 41/44 | 0.7 (0.4, 1.5) | 0.6 (0.2, 1.6) | 56/46 | 1.4 (0.7, 2.8) | 1.2 (0.5, 2.5) | 46/46 | 0.6 (0.3, 1.4) | 0.2 (0.1, 0.8) | ||||

| — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||||||||

| Both samples (first/second) | |||||||||||||||

| 53/67 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 72/65 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 72/73 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 92/73 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| 25/20 | 1.2 (0.5, 2.6) | 1.3 (0.6, 3.3) | 35/29 | 1.3 (0.7, 2.4) | 1.3 (0.6, 2.7) | 18/22 | 0.8 (0.4, 1.7) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.8) | 11/18 | 0.4 (0.2, 1.0) | 0.4 (0.2, 1.0) | ||||

| 27/27 | 2.3 (1.0, 5.6) | 2.2 (0.8, 5.9) | 20/28 | 0.6 (0.3, 1.4) | 0.5 (0.2, 1.3) | 19/16 | 1.3 (0.6, 3.0) | 1.1 (0.8, 6.9) | 39/41 | 0.7 (0.3, 1.3) | 0.6 (0.3, 1.2) | ||||

| 82/73 | 2.1 (1.1, 3.9) | 2.3 (1.02, 5.0) | 60/65 | 0.8 (0.5, 1.5) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.6) | 78/76 | 1.1 (0.7, 1.8) | 1.0 (0.5, 1.7) | 45/55 | 0.6 (0.3, 1.1) | 0.3 (0.1, 0.8) | ||||

Note: —, no data; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; PFAS, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances; PFHxS, perfluorohexanesulfonic acid; PFNA, perfluorononanoic acid; PFOA, perfluorooctanoic acid; PFOS, perfluorooctanesulfonic acid.

ORs computed by conditional logistic regression of matched pairs with adjustment for military grade and number of deployments.

ORs computed by conditional logistic regression of matched pairs with adjustment for military grade, number of deployments, and all other PFAS (all PFAS covariates involve the same exposure metric and categorization as the PFAS of interest).

We observed evidence of elevated serum concentrations of PFHxS in servicemen who had been stationed prior to sample collection at an Air Force installation with PFOS/PFOA concentrations in drinking water exceeding the 2016 U.S. EPA LHA, both in the first/only samples (9.2 vs. ; ) and the second samples (9.3 vs. ; ). Individuals with a history of service prior to serum collection at an installation with groundwater PFOS/PFOA concentrations exceeding the LHA had lower serum concentrations of these PFAS vs. other servicemen in first/only samples, and no difference in second samples (Table 2). A cross-tabulation of these two variables is provided in Supplementary Table 4. Because these results are from models including both variables as covariates, we additionally fit models controlling for only one variable at a time to assess the sensitivity of our findings to this mutual adjustment. In these analyses, we still observed associations with elevated PFHxS for the drinking water variable ( for first/only samples, for second samples), whereas associations with the groundwater variable were no longer statistical significant (PFOS: , ; PFOA: , ; PFHxS: , ).

We also observed elevated concentrations of PFOS and PFHxS for y of military service at sample collection for first/only samples, although these patterns were weak and not statistically significant for second samples (Table 2). We observed similar findings (but with wider CIs) when we repeated our analyses of PFOS, PFOA, and PFHxS restricting to samples collected y after the start of military service (Supplementary Table 5) and to controls (Supplementary Table 6). In analyses of MeFOSAA, PFNA, PFDA, and PFUnDA, we did not observe consistent evidence across samples of positive associations with service-related factors (Supplementary Table 7). When we analyzed the identified principal components, military occupation in fire protection prior to serum collection was positively associated with both PC1 and PC2, whereas years of service at serum collection was positively associated with PC1 in first/only samples and negatively associated with PC2 (Supplementary Table 8).

Results from the nested case–control analysis for PFOS, PFOA, PFHxS (a priori PFAS of interest), and PFNA (found to be inversely associated with TGCT) are summarized in Table 3. For PFOS, we observed a suggestive but statistically nonsignificant association with TGCT for elevated concentrations in the first/only sample after adjustment for other PFAS [OR for fourth vs. first quartile ; 95% CI: 0.9, 3.6; ]. Among the subset of subjects with two samples (with cases diagnosed at least 5 y after the earliest sample collection date), we observed a similar association with TGCT for elevated serum PFOS in the first sample. For the second sample, however, a statistically significant association with TGCT was observed for elevated serum PFOS (; 95% CI: 1.1, 6.4; ), particularly after adjustment for other PFAS (; 95% CI: 1.4, 15.1; ). We found no evidence of an association with TGCT for PFOA or PFHxS. For PFNA, we observed a statistically significant inverse association with TGCT in analyses of the first/only samples (irrespective of adjustment for other PFAS) and the second samples (after adjustment for other PFAS). In a joint analysis of dichotomized PFAS concentrations in both samples, only categories with an above-median PFOS concentration in the second sample were positively associated with TGCT, whereas above-median concentrations of PFNA in either sample were inversely associated with TGCT (Table 3). We observed similar findings for these four PFAS when we restricted the analysis to matched sets with case samples collected y after the start of military service (Supplementary Table 9) and using regression models unadjusted for grade and number of deployments (Supplementary Table 10). When we reanalyzed the PFOS measurement data using the same cut points for each sample type, an association with elevated serum concentration was observed only for the second samples (Supplementary Table 11). We found no clear evidence of an association with TGCT for serum concentrations of MeFOSAA, PFDA, or PFUnDA (Supplementary Table 12). When we conducted case–control analyses of the identified principal components, PC2 was inversely associated with TGCT for first/only samples, but not for the second samples, whereas for PC1 we observed a suggestive positive association with TGCT for the second samples (Supplementary Table 13).

Table 4 summarizes results from nested case–control analyses of dichotomized PFOS and PFNA concentrations stratified by selected subject and sample factors. For PFOS, the positive association with TGCT appeared stronger among non-Hispanic White individuals in comparison with persons of other races and ethnicities combined, particularly for the second sample (, 0.06 with and without adjustment for other PFAS, respectively). We observed suggestive differences in PFOS effects in relation to length of service at sample collection, with the association weakest or null for samples collected within the first year of military service and strongest for samples collected at y of service (for first/only samples) or 1–4 y of service (for second samples); however, tests of interaction were not statistically significant. PFOS findings also did not significantly differ across strata for other variables (year of sample collection, years from sample collection to case diagnosis, tumor histology). The inverse association between PFNA concentration in first/only samples and TGCT was significantly stronger for samples collected later than 2003, samples collected within the first year of service, for cases diagnosed y after serum collection, and for nonseminomas. These differences across strata, however, were generally not apparent for PFNA concentrations in the second samples.

Table 4.

Case–control analysis of serum PFOS and PFNA concentration (dichotomized using median among controls as the cut point) and testicular germ cell tumors, overall and stratified by selected factors, among active-duty U.S. Air Force servicemen (530 cases, 530 controls).

| First/only samplea | Second sample | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFOS | PFNA | PFOS | PFNA | |||||||

| Stratum | b (95% CI) | c (95% CI) | a (95% CI) | b (95% CI) | b (95% CI) | c (95% CI) | b (95% CI) | c (95% CI) | ||

| Overall | 530/530 | 1.3 (0.9, 1.8) | 1.5 (1.05, 2.2) | 0.7 (0.5, 0.9) | 0.7 (0.5, 0.9) | 187/187 | 2.0 (1.1, 3.7) | 2.3 (1.2, 4.3) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.2) | 0.6 (0.4, 1.2) |

| By race and ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 422/422 | 1.4 (1.0, 2.0) | 1.7 (1.1, 2.7) | 0.7 (0.5, 0.9) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.0) | 146/146 | 2.7 (1.3, 5.2) | 3.3 (1.6, 7.0) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.5) | 0.7 (0.3, 1.4) |

| Other | 108/108 | 1.0 (0.5, 2.2) | 1.1 (0.5, 2.5) | 0.6 (0.3, 1.2) | 0.6 (0.2, 1.4) | 41/41 | 0.5 (0.1, 2.6) | 0.3 (, 2.3) | 0.5 (0.1, 1.5) | 0.4 (0.1, 1.8) |

| — | — | d | — | |||||||

| By year of sample collection | ||||||||||

| 368/368 | 1.2 (0.8, 1.8) | 1.4 (0.9, 2.1) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.2) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.2) | 73/73 | 1.6 (0.5, 5.1) | 2.9 (0.7, 12.3) | 0.4 (0.1, 1.2) | 0.3 (0.1, 1.0) | |

| 162/162 | 2.4 (0.9, 6.0) | 3.8 (1.2, 12.0) | 0.4 (0.2, 0.7) | 0.4 (0.2, 0.8) | 114/114 | 2.6 (1.2, 5.6) | 2.5 (1.1, 5.5) | 0.9 (0.5, 1.6) | 0.9 (0.4, 2.0) | |

| — | — | c | — | |||||||

| By years of service at sample collection | ||||||||||

| 316/316 | 1.2 (0.8, 1.9) | 1.4 (0.8, 2.4) | 0.5 (0.3, 0.8) | 0.4 (0.3, 0.7) | 16/13 | 0.7 (0.1, 5.0) | 1.2 (0.1, 12.9) | — | — | |

| 1–4 | 84/88 | 1.3 (0.5, 3.2) | 1.8 (0.6, 5.5) | 0.6 (0.3, 1.5) | 0.5 (0.2, 1.3) | 67/70 | 4.0 (1.4, 11.6) | 5.5 (1.4, 21.5) | 0.8 (0.3, 2.0) | 0.4 (0.1, 1.3) |

| 130/126 | 2.2 (1.0, 5.0) | 3.0 (1.2, 7.7) | 1.3 (0.7, 2.5) | 1.7 (0.8, 3.4) | 104/104 | 1.9 (0.8, 4.5) | 2.0 (0.8, 5.1) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.6) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.7) | |

| — | — | c | ||||||||

| By years from sample collection to cancer diagnosis | ||||||||||

| 258/258 | 1.3 (0.7, 2.2) | 1.5 (0.8, 2.8) | 0.5 (0.4, 0.8) | 0.5 (0.3, 0.7) | 1/1 | — | — | — | — | |

| 272/272 | 1.3 (0.8, 2.0) | 1.4 (0.9, 2.3) | 1.3 (0.7, 2.4) | 1.6 (0.8, 3.2) | 186/186 | 2.0 (1.1, 3.7) | 2.3 (1.2, 4.3) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.2) | 0.6 (0.3, 1.1) | |

| — | — | c | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| By tumor histology | ||||||||||

| Seminoma | 300/300 | 1.3 (0.8, 1.9) | 1.8 (1.0, 3.3) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.3) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.4) | 125/125 | 2.2 (1.1, 4.6) | 2.8 (1.2, 6.3) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.4) | 0.7 (0.3, 1.4) |

| Nonseminoma | 230/230 | 1.4 (0.8, 2.5) | 1.5 (0.9, 2.4) | 0.4 (0.2, 0.7) | 0.4 (0.2, 0.7) | 62/62 | 2.0 (0.6, 6.0) | 2.3 (0.7, 8.1) | 0.6 (0.2, 1.6) | 0.5 (0.2, 1.8) |

| — | — | d | ||||||||

Note: Median cut points: PFOS, for first/only sample and for second sample; PFNA, for first/only sample and for second sample. —, no data; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; PFAS, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances; PFNA, perfluorononanoic acid; PFOS, perfluorooctanesulfonic acid.

Analysis includes all subjects.

ORs and tests of interaction computed by conditional logistic regression of matched pairs with adjustment for military grade and number of deployments.

ORs and tests of interaction computed by conditional logistic regression of matched pairs with adjustment for military grade, number of deployments, and all other PFAS (all PFAS covariates involve the same exposure metric and categorization as the PFAS of interest).

In general, the -value reflects a test of interaction between PFAS exposure and the stratified variable. For the two cancer-related variables (years from sample collection to cancer diagnosis and tumor histology), the -value reflects a test of heterogeneity between sets of matched case–control pairs defined by the case variable of interest.

To investigate the potential for at least partial mediation by PFOS effects of the association between military occupation in fire protection and TGCT, we compared models with and without adjustment for serum PFOS concentration as a covariate, among participants with two samples (with cases diagnosed at least 5 y after the earliest sample collection date). The OR for having fire protection as a military occupation prior to case diagnosis was 3.8 (95% CI: 0.4, 34.5) among these participants before PFOS adjustment and 2.3 (95% CI: 0.2, 22.3) after adjustment for PFOS concentration in the second sample.

Discussion

This study is to our knowledge the first to investigate serum PFAS concentrations among U.S. Air Force servicemen and their associations with TGCT. We observed elevated concentrations of some PFAS (PFHxS and MeFOSAA in particular) among servicemen relative to NHANES data for samples collected in the early 2000s. We also identified some service-related factors associated with elevated PFAS concentrations, most notably occupation in fire protection (with elevated PFOS, PFOA, PFHxS) and a history of being stationed at an Air Force facility where PFOS/PFOA concentrations in drinking water samples exceeded the 2016 EPA LHA (elevated PFHxS). In case–control analyses, higher serum PFOS concentrations were positively associated with TGCT, particularly in the second samples. We also observed an inverse association with TGCT for PFNA concentrations, whereas findings were null for PFOA and other PFAS.

Our finding of significantly elevated serum concentrations of PFHxS and MeFOSAA (a chemical precursor of PFOS) among Air Force study controls vs. NHANES for samples collected in 1999–2000 and 2003–2004 is notable, given that the majority of AFFFs used on DoD facilities at that time involved formulations containing PFOS and perfluoroalkane sulfonates such as PFHxS.4 Although PFOA is not an intended ingredient of AFFFs, long-alkyl-chain fluorochemicals in fluorotelomer-based AFFF formulations can break down to PFOA; for example, it has been estimated that 8:2 fluorotelomer alcohol breakdown products react in the environment to produce PFOA at a molar fraction of between on a per-emission basis.21,22 PFOS-based AFFFs were phased out of production in 2003, leading to an increase in DoD AFFF acquisition of fluorotelomer-based formulations, although existing military stockpiles of PFOS-based AFFFs continued to be used.6 The observed secular declines for both NHANES and our study population controls in serum concentrations of PFOS, PFHxS, and MeFOSAA through the 2000s is likely an effect of the phaseout of PFOS-based AFFFs and other products. The weaker secular decline for PFOA may reflect the later and more gradual phaseout of this chemical from commercial products.1 No phaseouts of PFNA, PFDA, and PFUnDA were initiated across the 2000s, which may account for the observed stable concentrations of these chemicals.

The strongest service-related predictor of elevated serum PFAS concentrations observed was employment in fire protection (i.e., firefighting), with substantially elevated concentrations of PFOS and PFHxS (and, to a lesser extent, PFOA), likely because of occupational AFFF use. Our findings are consistent with those of a cross-sectional study of Australian firefighters employed at commercial airports; that study population had similarly high mean serum concentrations of PFOS ( vs. in our subjects) and PFHxS ( vs. ), whereas the measured PFOA concentrations did not differ from other general-population comparison populations.23 In contrast, measured serum PFAS concentrations from prior studies of U.S. firefighters were lower than our observed findings and more variable regarding which PFAS are elevated, although most studies reported elevated circulating PFHxS in comparison to nonfirefighter reference groups.24–27 Because these prior U.S. studies did not include military or airport-based firefighters, it is likely that their findings reflect less frequent AFFF use in nonairport civilian firefighters and variability in the type of AFFF formulation used. A recent IARC monograph evaluation of the carcinogenicity of occupational firefighting noted limited epidemiological evidence of an association with testicular cancer.14 Our finding of a suggested association between fire protection as a military occupation and TGCT (reported in greater detail in another publication),20 although not statistically significant, offers further evidence supporting a relationship. Our observation that the association between firefighting prior to case diagnosis and TGCT among subjects with two samples became attenuated after adjustment for PFOS concentration in the second sample is compatible with a role for PFOS effects in mediating the association between firefighting and testicular cancer.

We also observed elevations in PFHxS serum concentrations in subjects who were previously stationed at Air Force bases reported by the DoD to have PFOA/PFOS concentrations in drinking water samples exceeding the 2016 U.S. EPA LHA of 70 ppt.8 It is unclear why elevations in PFOS or PFOA themselves were not observed; we speculate that one possible explanation is the longer serum half-life of PFHxS, estimated at 5–7 y vs. 2–3 y for PFOS and PFOA.28 As the difference in concentrations in first/only samples did not achieve statistical significance and these findings are based on a small number of exposed subjects, these findings should be interpreted with caution and warrant further study.

A novel finding from our nested case–control analysis is the observed association between elevated serum PFOS concentrations and TGCT. We are not aware of prior epidemiological evidence regarding circulating PFOS and testicular cancer, although one notable study is an investigation of cancer incidence conducted in the Ronneby Register Cohort, a study of residents of Ronneby, Sweden, with PFAS-contaminated drinking water dominated by extremely high levels of PFOS and PFHxS, with geometric mean serum concentrations of and , respectively, observed in a sample of residents who resided between 1985 and 2013 in neighborhoods receiving water from the contaminated waterworks.10 In that investigation, a moderately increased risk of testicular cancer was observed among residents who resided at an address supplied by contaminated drinking water, although the CIs were wide and included unity. It is unclear what pathogenetic mechanisms would mediate a causal association between PFOS and TGCT. Nevertheless, there is toxicological evidence of PFOS-induced male reproductive toxicity in adult mice (reduced testis weight and sperm counts), adult rats (degeneration of gonadotrophic cells and spermatozoids, testicular edema), and zebrafish (gonad structural changes, decrease in spermatogonia).29–31 It has been hypothesized that endocrine-disrupting chemicals may contribute to the pathogenesis of testicular cancer, given the importance of sex steroid hormones in urogenital development and homeostasis.32

We observed stronger evidence of an association between serum PFOS concentrations and TGCT in the analysis of the second banked samples, collected on average after several years of military service, in comparison with the results for first/only samples. The reasons for this are unclear. One possibility is that the measurements in first/only samples (a large proportion of which were collected close to the start of military service) may be less representative of long-term PFOS concentrations, given that they are more likely to reflect a combination of PFOS exposures as civilians and exposures during military service (which may differ), whereas the second samples may on average reflect a more consistent pattern of exposure and be more informative as surrogates of longer-term levels. In line with this hypothesis is the finding that, in stratified analyses of measurements from the first/only samples, serum PFOS concentration is associated with TGCT for subjects with y of service at the time of specimen collection. In our stratified analysis we also observed a stronger association with PFOS among non-Hispanic White subjects vs. subjects of other racial/ethnic backgrounds, particularly for results with the second samples. The reason for this difference by race, if real, is unknown, although it is notable that the incidence of TGCT in the United States is highest among Non-Hispanic White men.11 Given the small number of cases among persons of other race and ethnicity, these findings should be interpreted with caution.

We did not observe positive associations for other PFAS with TGCT. Our null findings for PFOA are inconsistent with results from a few epidemiological studies involving workers at PFOA production plants and communities with contaminated drinking water.33,34 However, because these studies involved subjects having PFOA concentrations substantially higher than those observed in our study population, we cannot rule out an association with testicular cancer at higher concentrations. We also observed an inverse association with PFNA, a PFAS used in some AFFFs, although not the PFOS-based formulation previously used by the DoD.22 We are not aware of prior evidence suggesting an inverse association between PFNA and other health end points. It is notable that the observed inverse association was apparent only among cases diagnosed y after serum collection. The absence of an association with PFNA after incorporating a 5-y lag raises the question of whether chance or disease-induced effects (reverse causation) may account for the finding.

Our study has several strengths. It is to our knowledge the largest study of PFAS exposure and testicular cancer conducted to date and the first to investigate associations with directly measured serum PFAS concentrations. The use of prediagnostic specimens in this study reduced the potential for reverse causation bias, and the availability of multiple specimens for a subset of participants enabled us to evaluate PFAS associations at different periods of service. In addition, the linkage to DoD records for each individual enabled us to investigate possible service-related sources of PFAS exposure.

The study also has limitations, including the comparatively small number of cases and controls with two prediagnostic samples, which limited the statistical power of analyses within this subgroup. In addition, the small number of non-White participants precluded case–control analyses stratified by race and ethnicity. We were unable to adjust for prior history of cryptorchidism or family history of testicular cancer, known TGCT risk factors, in our analysis, because this information is not captured within the DMSS. However, as cryptorchidism has not been associated with PFAS exposures35 and of TGCT cases are expected to have each risk factor,36 confounding from these factors is unlikely to account for our findings. Our restriction to cases age y at diagnosis may affect the generalizability of our findings to cases diagnosed at older ages ( of all cases in the U.S. general population).37 We also note that the PFAS concentrations in first/only samples may not be representative of PFAS exposures among Air Force servicemen in general, given that approximately half of the samples were collected y after the start of military service; the second samples are likely more informative in this regard. In addition, we limited the study follow-up to cases diagnosed while on active duty; this restriction was made because the DoD cancer registry does not comprehensively capture cancer diagnoses after servicemen are discharged from active-duty service. The lag time between serum collection and case diagnosis varied widely (between 0.0 and 19.8 y); however, the association between dichotomized PFOS concentration and TGCT did not differ between analyses restricted to cases diagnosed y after serum collection and cases diagnosed y post-phlebotomy. The time from blood collection to processing, HIV testing, and repository storage likely varied across samples, although the impact of such preanalytical factors on measured PFAS concentrations is unclear; one study reported that serum concentrations of PFHxS, PFOA, PFOS, and PFNA were stable even when serum was left at room temperature for 10 d,38 whereas another study found differences in the concentrations of many PFAS when samples were immediately processed and frozen as plasma, in comparison with when samples were shipped by mail at ambient temperature when the transportation occurred during the winter months.39 The impact of the long storage time on serum PFAS concentrations is unknown; however, because we individually matched controls to cases on the basis of the year(s) of serum collection, among other matching factors, we would not expect differential measurement error between matched pairs from storage-related effects. We had a small number of samples collected after 2012, which prevented us from investigating more recent patterns of PFAS exposure in Air Force personnel. Last, given the multiple comparisons conducted in this analysis, we cannot rule out the possibility that at least some of the observed associations may have arisen due to chance; replication of these findings in other populations is needed.

In conclusion, this study of U.S. Air Force servicemen provides novel evidence of service-related predictors of PFAS exposure and of an association between elevated serum PFOS concentrations and TGCT. These findings argue for further examination of PFOS exposure and testicular cancer, particularly among military and highly exposed populations. Additional research investigating serum PFAS concentrations in military personnel would provide useful information to confirm our findings and, using recently collected sera, gain insight into current patterns of PFAS exposure in this population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank K. Kato, R. Hatchett, K. Hubbard, K. Smith, and D. Tevis (U.S. CDC) for the quantification of PFAS serum concentrations, and B. Graubard [National Cancer Institute (NCI), Rockville, Georgia) for advice regarding the analysis of NHANES data.

This research was supported by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs through the Peer-Reviewed Cancer Research Program (W81XWH-19-1-1044) and the Intramural Research Program of the NCI, National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and are not to be construed as official or necessarily endorsed by the DoD, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the U.S. CDC, or the NIH. The use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. CDC, the Public Health Service, the Department of Health and Human Services or the Department of Defense.

References

- 1.Buck RC, Franklin J, Berger U, Conder JM, Cousins IT, de Voogt P, et al. 2011. Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the environment: terminology, classification, and origins. Integr Environ Assess Manag 7(4):513–541, PMID: , 10.1002/ieam.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calafat AM, Wong LY, Kuklenyik Z, Reidy JA, Needham LL. 2007. Polyfluoroalkyl chemicals in the U.S. population: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003–2004 and comparisons with NHANES 1999–2000. Environ Health Perspect 115(11):1596–1602, PMID: , 10.1289/ehp.10598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu XC, Andrews DQ, Lindstrom AB, Bruton TA, Schaider LA, Grandjean P, et al. 2016. Detection of poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in U.S. Drinking water linked to industrial sites, military fire training areas, and wastewater treatment plants. Environ Sci Technol Lett 3(10):344–350, PMID: , 10.1021/acs.estlett.6b00260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Darwin RL. 2004. Estimated Quantities of Aqueous Film Forming Foam (AFFF) in the United States. https://www.informea.org/en/estimated-quantities-aqueous-film-forming-foam-afff-united-states-2004 [accessed 18 September 2022].

- 5.Place BJ, Field JA. 2012. Identification of novel fluorochemicals in aqueous film-forming foams used by the US military. Environ Sci Technol 46(13):7120–7127, PMID: , 10.1021/es301465n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carabajal S. 2018. Swap complete: AF protects Airmen, environment with new firefighting foam. https://www.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/1557670/swap-complete-af-protects-airmen-environment-with-new-firefighting-foam/ [accessed 18 September 2022].

- 7.Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment. Department of Defense. 2020. Perfluoroocanoane Sulfonate and Perfluorooctanoic Acid on Military Installations. Report to Congress. 2-80DE234. https://media.defense.gov/2021/May/27/2002730765/-1/-1/0/DOD-PFOS-AND-PFOA-ON-MILITARY-INSTALLATIONS-RTC-APRIL-2020.PDF [accessed 11 June 2023].

- 8.Sullivan M. 2018. Addressing Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) and Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA). https://partner-mco-archive.s3.amazonaws.com/client_files/1524589484.pdf [accessed 9 September 2018].

- 9.Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Lauby-Secretan B, Loomis D, Guyton KZ, Grosse Y, El Ghissassi F, et al. 2014. Carcinogenicity of perfluorooctanoic acid, tetrafluoroethylene, dichloromethane, 1,2-dichloropropane, and 1,3-propane sultone. Lancet Oncology 15(9):924–925, PMID: , 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70316-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li H, Hammarstrand S, Midberg B, Xu Y, Li Y, Olsson DS, et al. 2022. Cancer incidence in a Swedish cohort with high exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances in drinking water. Environmental Research 204(Pt C):112217, PMID: , 10.1016/j.envres.2021.112217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGlynn KA, Trabert B. 2012. Adolescent and adult risk factors for testicular cancer. Nat Rev Urol 9(6):339–349, PMID: , 10.1038/nrurol.2012.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu K, Devesa SS, Wu H, Zahm SH, Jatoi I, Anderson WF, et al. 2009. Cancer incidence in the U.S. military population: comparison with rates from the SEER program. Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 18(6):1740–1745, PMID: , 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Speaks C, McGlynn KA, Cook MB. 2012. Significant calendar period deviations in testicular germ cell tumors indicate that postnatal exposures are etiologically relevant. Cancer Causes Control 23(10):1593–1598, PMID: , 10.1007/s10552-012-0036-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Demers PA, DeMarini DM, Fent KW, Glass DC, Hansen J, Adetona O, et al. 2022. Carcinogenicity of occupational exposure as a firefighter. Lancet Oncology 23(8):985–986, PMID: , 10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00390-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perdue CL, Cost AA, Rubertone MV, Lindler LE, Ludwig SL. 2015. Description and utilization of the United States department of defense serum repository: a review of published studies, 1985–2012. PLoS One 10(2):e0114857, PMID: , 10.1371/journal.pone.0114857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perdue CL, Eick-Cost AA, Rubertone MV. 2015. A brief description of the operation of the DoD Serum Repository. Mil Med 180(suppl 10):10–12, PMID: , 10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kato K, Kalathil AA, Patel AM, Ye X, Calafat AM. 2018. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances and fluorinated alternatives in urine and serum by on-line solid phase extraction-liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Chemosphere 209:338–345, PMID: , 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.06.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hornung RW, Reed LD. 1990. Estimation of average concentration in the presence of nondetectable values. Appl Occup Environ Hyg 5:6, 10.1080/1047322X.1990.10389579. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.S. CDC (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data: NHANES Questionnaires, Datasets, and Related Documentation. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/default.aspx [accessed 1 May 2022].

- 20.Denic-Roberts H, McGlynn K, Rhee J, Byrne C, Lang M, Vu P, et al. 2023. Military occupation and testicular germ cell tumor risk among U.S. Air Force servicemen. Occup Environ Med 80(6):312–318, PMID: , 10.1136/oemed-2022-108628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wallington TJ, Hurley MD, Xia J, Wuebbles DJ, Sillman S, Ito A, et al. 2006. Formation of C7F15COOH (PFOA) and other perfluorocarboxylic acids during the atmospheric oxidation of 8:2 fluorotelomer alcohol. Environ Sci Technol 40(3):924–930, PMID: , 10.1021/es051858x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson RH, Long GC, Porter RC, Anderson JK. 2016. Occurrence of select perfluoroalkyl substances at U.S. Air Force aqueous film-forming foam release sites other than fire-training areas: field-validation of critical fate and transport properties. Chemosphere 150:678–685, PMID: , 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rotander A, Toms LM, Aylward L, Kay M, Mueller JF. 2015. Elevated levels of PFOS and PFHxS in firefighters exposed to aqueous film forming foam (AFFF). Environ Int 82:28–34, PMID: , 10.1016/j.envint.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khalil N, Ducatman AM, Sinari S, Billheimer D, Hu C, Littau S, et al. 2020. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substance and cardio metabolic markers in firefighters. J Occup Environ Med 62(12):1076–1081, PMID: , 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trowbridge J, Gerona RR, Lin T, Rudel RA, Bessonneau V, Buren H, et al. 2020. Exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances in a cohort of women firefighters and office workers in San Francisco. Environ Sci Technol 54(6):3363–3374, PMID: , 10.1021/acs.est.9b05490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graber JM, Black TM, Shah NN, Caban-Martinez AJ, Lu S-e, Brancard T, et al. 2021. Prevalence and predictors of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) serum levels among members of a suburban US volunteer fire department. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(7):3730, PMID: , 10.3390/ijerph18073730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burgess JL, Fisher JM, Nematollahi A, Jung AM, Calkins MM, Graber JM, et al. 2023. Serum per- and polyfluoroalkyl substance concentrations in four municipal US fire departments. Am J Ind Med 66(5):411–423, PMID: , 10.1002/ajim.23413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Drew R, Hagen TG, Champness D, Sellier A. 2022. Half-lives of several polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in cattle serum and tissues. Food Addit Contam Part A Chem Anal Control Expo Risk Assess 39(2):320–340, PMID: , 10.1080/19440049.2021.1991004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qu J-H, Lu C-C, Xu C, Chen G, Qiu L-L, Jiang J-K, et al. 2016. Perfluorooctane sulfonate-induced testicular toxicity and differential testicular expression of estrogen receptor in male mice. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 45:150–157, PMID: , 10.1016/j.etap.2016.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lopez-Doval S, Salgado R, Pereiro N, Moyano R, Lafuente A. 2014. Perfluorooctane sulfonate effects on the reproductive axis in adult male rats. Environ Res 134:158–168, PMID: , 10.1016/j.envres.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen J, Wang X, Ge X, Wang D, Wang T, Zhang L, et al. 2016. Chronic perfluorooctanesulphonic acid (PFOS) exposure produces estrogenic effects in zebrafish. Environ Pollut 218:702–708, PMID: , 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.07.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toppari J. 2008. Environmental endocrine disrupters. Sex Dev 2(4–5):260–267, PMID: , 10.1159/000152042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barry V, Winquist A, Steenland K. 2013. Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) exposures and incident cancers among adults living near a chemical plant. Environ Health Perspect 121(11–12):1313–1318, PMID: , 10.1289/ehp.1306615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vieira VM, Hoffman K, Shin HM, Weinberg JM, Webster TF, Fletcher T. 2013. Perfluorooctanoic acid exposure and cancer outcomes in a contaminated community: a geographic analysis. Environ Health Perspect 121(3):318–323, PMID: , 10.1289/ehp.1205829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vesterholm Jensen D, Christensen J, Virtanen HE, Skakkebæk NE, Main KM, Toppari J, et al. 2014. No association between exposure to perfluorinated compounds and congenital cryptorchidism: a nested case-control study among 215 boys from Denmark and Finland. Reproduction 147(4):411–417, PMID: , 10.1530/REP-13-0444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McGlynn KA, Sakoda LC, Rubertone MV, Sesterhenn IA, Lyu C, Graubard BI, et al. 2006. Body size, dairy consumption, puberty, and risk of testicular germ cell tumors. Am J Epidemiol 165(4):355–363, PMID: , 10.1093/aje/kwk019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute. 2022. Cancer Statistics Data Visualizations Tool. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dataviz [accessed 3 March 2023].

- 38.Kato K, Wong LY, Basden BJ, Calafat AM. 2013. Effect of temperature and duration of storage on the stability of polyfluoroalkyl chemicals in human serum. Chemosphere 91(2):115–117, PMID: , 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bach CC, Henriksen TB, Bossi R, Bech BH, Fuglsang J, Olsen J, et al. 2015. Perfluoroalkyl acid concentrations in blood samples subjected to transportation and processing delay. PLoS One 10(9):e0137768, PMID: , 10.1371/journal.pone.0137768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.