Abstract

Degenerative spondylolisthesis is a common cause of low back pain and resultant disability in the adult population. The causes of degenerative spondylolisthesis are not entirely understood, though a combination of anatomic and lifestyle factors likely contributes to the development of this pathology. Here, we report a case of a 38-year-old female presenting with low back pain and right lower extremity radiculopathy, found to have degenerative L5-S1 spondylolisthesis, which we postulate developed in part due to the sagittal orientation of her L5-S1 facet joints bilaterally.

Keywords: injury biomechanics, surgery, orthopedic surgery, neurosurgery, lumbar spine, transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion, spondylolisthesis, spine surgery

Introduction

Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis (DLS) is an extremely common spine condition with incidence estimates ranging from 12% to 19.9% [1]. In this pathology, one vertebral body translates relative to its adjacent counterpart with the potential to cause significant low back pain, neurogenic claudication and/or radiculopathy secondary to instability as well as central canal, lateral recess, or foraminal stenosis [2,3]. Neurogenic claudication results in a constellation of symptoms including cramping back, buttock, and leg pain due to the compression of multiple lumbar nerve roots in the cauda equina, while radiculopathy relates to buttock and leg pain attributable to a single compressed nerve root in the lateral recess or neural foramen [4]. Symptomatic DLS can lead to diminished health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and disability in the adult population [5,6]. Following failure of an appropriate trial of non-operative treatment, surgical treatment consists of either decompression alone or decompression with instrumented fusion through an open or minimally invasive approach depending on various pathological and patient-related factors [7-10]. DLS is most common at the L4-5 level followed by the L5-S1 level [2,4]. However, isthmic spondylolisthesis secondary to pars interarticularis defect accounts for the majority of cases of spondylolisthesis at L5-S1, rather than DLS [11]. Here, we present the case of a young female with mobile degenerative L5-S1 spondylolisthesis secondary to the presence of abnormal facet joint morphology/anatomy as a predisposing factor for the early development of this DLS.

Case presentation

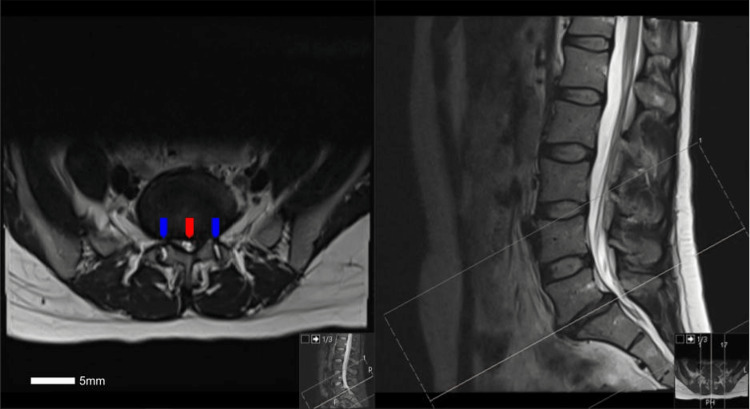

The patient was a 38-year-old female without a significant medical history who presented to our clinic in the setting of low back pain, neurogenic claudication and right lower extremity pain for a duration of 18 months. She tried medications including membrane stabilizers, muscle relaxants, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with little relief, and had attempted physical therapy as well as epidural steroid injections with only temporary relief. On physical examination, the patient did have full strength throughout her bilateral lower extremities; however, a sensory examination demonstrated altered sensation involving the right lower extremity along the L5 and S1 dermatomes. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine demonstrated significant disc degeneration and collapse at the L5-S1 level along with disc herniation resulting in moderate to severe L5-S1 central canal and foraminal stenosis along with presence of grade 1 L5-S1 spondylolisthesis (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Axial (left) and sagittal (right) T2-weighted MRI of the lumbar spine without contrast at the level of L5-S1, demonstrating severe central canal and lateral recess stenosis (red arrow) with bilateral foraminal stenosis, as well as facet joint effusions (blue arrows).

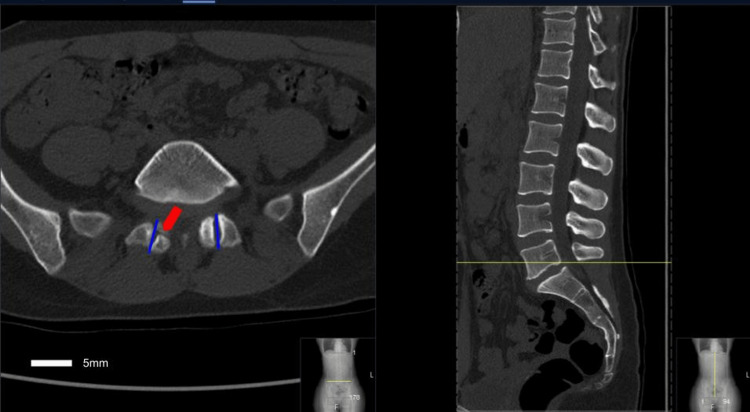

Computed tomography (CT) of the lumbar spine was performed to understand further anatomical details and rule out pars defect that demonstrated the presence of abnormal/atypical facet joint anatomy with the more sagittally oriented L5-S1 facet joint (Figure 2).

Figure 2. An axial (left) and sagittal (right) CT scan of the lumbar spine at the L5-S1 level.

Note the pars defect on the right (red arrow), as well as the sagittal orientation of the L5-S1 facet joint line (blue lines).

The facet joint at L5-S1 demonstrated an angle relative to the midsagittal axis of 1.6°, which is substantially more sagittal than what would be expected of a L5-S1 joint that is typically coronally oriented (Table 1).

Table 1. Facet tropism of the lumbar spine.

Corresponding angles of each lumbar facet joint measured on the patient’s CT relative to a midsagittal line, or the patient’s facet tropism; the expected progression would include a continued increase in the angle with caudal progression down the lumbar spine.

| Level | Angle of the facet joint line relative to the midsagittal line |

| L1-L2 | 20.4 |

| L2-L3 | 24.5 |

| L3-L4 | 33.4 |

| L4-L5 | 35.3 |

| L5-S1 | 1.6 |

Additionally, flexion/extension plain films were obtained that showed a mobile Meyerding Grade I spondylolisthesis at L5-S1 secondary to the inability of the facet joint to prevent translational motion due to the sagittal orientation (Figure 3).

Figure 3. A flexion (left) and extension (right) lateral plain film radiograph of the lumbar spine demonstrating a mobile spondylolisthesis at L5-S1 (red arrows).

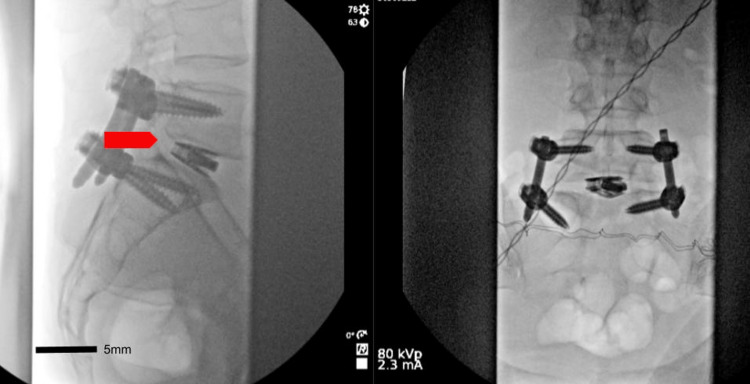

After a discussion of risks and benefits of surgical intervention, the patient ultimately underwent an L5-S1 minimally invasive decompression and transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF) with pedicle screw fixation using intraoperative 3D navigation. The surgery was completed without complications with complete reduction of the spondylolisthesis (Figure 4). The patient was discharged with significant improvement in her radiculopathy.

Figure 4. A lateral (left) and anterior/posterior (right) lateral plain film radiograph of the lumbar spine after the placement of the L5-S1 interbody graft and percutaneous pedicle screw fixation, with reduction of the spondylolisthesis (red arrow) seen on the lateral film.

Discussion

This case demonstrates an atypical characteristic of degenerative spondylolisthesis. Our patient did not meet the typical demographics of degenerative spondylolisthesis, as DLS presents most commonly at the L4-L5 level in patients older than 50 years of age [12]. Also, she lacked the typical pars defect that accounts for the majority of cases of L5-S1 isthmic spondylolisthesis in younger populations [13]. Therefore, it is important to assess anatomic factors that may have contributed to the premature development of this pathology.

Facet tropism, the variation in facet joint orientation in the sagittal plane, has been sparsely studied and is often overlooked in the development of lumbar degenerative pathology [14]. Facet tropism in our patient demonstrated a general increase in angulation until an abruptly sagittal facet joint at the L5-S1 level (Table 1). Previous research has primarily explored facet orientation and tropism in relation to lumbar disc herniation among young adults [15]. While there is limited evidence suggesting that facet tropism alone does not contribute to lumbar stenosis, it has been proposed as an independent predictor of progressive DLS by Yoshihara [2,16]. Multiple studies have demonstrated an association between an increased sagittal facet joint angulation and an elevated risk of developing spondylolisthesis [17,18]. Specifically, studies by Samartzis et al. and Guo et al. found that facet angulations exceeding 58 and 60 degrees, respectively, were indicative of a greater likelihood of spondylolisthesis development. Furthermore, Connolly et al. in a study of adolescent tennis players found that larger facet joint angles were associated with higher rates of spondylolysis that might predispose them to future pars abnormalities [19].

Leng and colleagues conducted a study examining the relationship between spinopelvic type and facet joint orientation in the development of lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis. They discovered that the facet joint morphology undergoes dynamic changes, with remodeling of facet joint orientation accompanying the progression of spondylolisthesis [20]. Facet joint morphology and angulation should be considered when conservatively managing symptomatic patients with degenerative pathologies of the lumbar spine in order to identify those who may be predisposed to further progression of their degenerative disease process.

Conclusions

We believe that the presence of abnormally sagittally oriented facet joints, as described in this case, at the L5-S1 level leads to the development of L5-S1 degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis, even in the absence of florid pars defects. Considering facet joint angulation may improve patient counseling and treatment selection, as a sagittal facet joint orientation can potentially accelerate degenerative spondylolisthesis. Moreover, the atypical joint anatomy can pose challenges in accurately identifying intraoperative landmarks, particularly during minimally invasive techniques that offer limited visualization. Therefore, obtaining preoperative CT scans and intraoperative navigation are increasingly important in young patients with spondylolisthesis. This case serves as an important teaching point for a thorough assessment of anatomic nuances that affect patient management.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study

References

- 1.Natural history of degenerative spondylolisthesis. A systematic review and meta-analysis. (Article in press) Atalay B, Gadjradj PS, Sommer FS, Wright D, Rawanduzy C, Ghogawala Z, Härtl R. World Neurosurg. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2023.05.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pathomechanisms and predisposing factors for degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis: a narrative review. Yoshihara H. JBJS Rev. 2020;8:0. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.20.00068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis: definition, natural history, conservative management, and surgical treatment. Bydon M, Alvi MA, Goyal A. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2019;30:299–304. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2019.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neurogenic claudication secondary to degenerative spondylolisthesis: is fusion always necessary? Kitchen WJ, Mohamed M, Bhojak M, Wilby M. Br J Neurosurg. 2016;30:662–665. doi: 10.1080/02688697.2016.1206181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Two-year comprehensive medical management of degenerative lumbar spine disease (lumbar spondylolisthesis, stenosis, or disc herniation): a value analysis of cost, pain, disability, and quality of life: clinical article. Parker SL, Godil SS, Mendenhall SK, Zuckerman SL, Shau DN, McGirt MJ. J Neurosurg Spine. 2014;21:143–149. doi: 10.3171/2014.3.SPINE1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Symptoms, signs, and functional disability in adult spondylolisthesis. Möller H, Sundin A, Hedlund R. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:683–690. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200003150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Outcomes of surgical intervention for degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis: a comparative analysis of different surgical fixation techniques. Jadhakhan F, Bell D, Rushton A. J Spine Surg. 2023;9:83–97. doi: 10.21037/jss-22-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Minimally invasive versus open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion for grade I lumbar spondylolisthesis: 5-year follow-up from the prospective multicenter Quality Outcomes Database registry. Chan AK, Bydon M, Bisson EF, et al. Neurosurg Focus. 2023;54:0. doi: 10.3171/2022.10.FOCUS22602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laminectomy plus fusion versus laminectomy alone for lumbar spondylolisthesis. Ghogawala Z, Dziura J, Butler WE, et al. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1424–1434. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1508788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.A protocol of a randomized controlled multicenter trial for surgical treatment of lumbar spondylolisthesis: the Lumbar Interbody Fusion Trial (LIFT) de Kunder SL, Rijkers K, van Kuijk SM, Evers SM, de Bie RA, van Santbrink H. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:417. doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-1280-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.A systematic review of clinical outcomes in surgical treatment of adult isthmic spondylolisthesis. Noorian S, Sorensen K, Cho W. Spine J. 2018;18:1441–1454. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2018.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis: an epidemiological perspective: the Copenhagen Osteoarthritis Study. Jacobsen S, Sonne-Holm S, Rovsing H, Monrad H, Gebuhr P. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:120–125. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000250979.12398.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Management of lumbar spondylolysis in the adolescent athlete: a review of over 200 cases. Choi JH, Ochoa JK, Lubinus A, Timon S, Lee YP, Bhatia NN. Spine J. 2022;22:1628–1633. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2022.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Associations between facet tropism and vertebral rotation in patients with degenerative lumbar disease. Ma Y, Huang P, Tu Z, Yao Z, Wang Z, Luo Z, Hu X. Eur J Med Res. 2021;26:149. doi: 10.1186/s40001-021-00622-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Are there correlations between facet joint parameters and lumbar disk herniation laterality in young adults? Ke S, Sun T, Zhang W, Zhang J, Li Z. J Clin Neurosci. 2023;109:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2023.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The relationship between bone canal diameter and facet tropism in cases of lumbar spinal stenosis. Akar E, Toprak F, Öğrenci A. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2022;13:641–646. doi: 10.25259/JNRP-2022-7-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Critical values of facet joint angulation and tropism in the development of lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis: an international, large-scale multicenter study by the AOSpine Asia Pacific Research Collaboration Consortium. Samartzis D, Cheung JP, Rajasekaran S, et al. Global Spine J. 2016;6:414–421. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1564417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Predictors of L4-L5 degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis: L4 inclination angle and facet joint angle. Guo M, Kong C, Sun S, Sun X, Li X, Lu S. World Neurosurg. 2019;130:0–6. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.06.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lumbar spine abnormalities and facet joint angles in asymptomatic elite junior tennis players. Connolly M, Rotstein AH, Roebert J, et al. Sports Med Open. 2020;6:57. doi: 10.1186/s40798-020-00285-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Correlation between the spinopelvic type and morphological characteristics of lumbar facet joints in degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis. Leng Y, Tang C, He B, et al. J Neurosurg Spine. 2023;38:425–435. doi: 10.3171/2022.11.SPINE22979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]