Abstract

Purpose

Dysregulated behaviors of trophoblast cells leading to defective placentation are considered the main cause of preeclampsia (PE). Abnormal miRNA expression profiles have been observed in PE placental tissue, indicating the significant role of miRNAs in PE development. This study aimed to investigate the expression of miR-101-5p in PE placental tissue and its biological functions.

Methods

The expression of miR-101-5p in placental tissue was detected by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). The localization of miR-101-5p in term placental tissue and decidual tissue was determined by the fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)-immunofluorescence (IF) double labeling assay. The effect of miR-101-5p on the migration, invasion, proliferation, and apoptosis of the HTR8/SVneo trophoblast cells was investigated. Online databases combined with transcriptomics were used to identify potential target genes and related pathways of miR-101-5p. Finally, the interaction between miR-101-5p and the target gene was verified by qRT-PCT, WB, dual-luciferase reporter assay, and rescue experiments.

Results

The study found that miR-101-5p was upregulated in PE placental tissue compared to normal controls and was mainly located in various trophoblast cell subtypes in placental and decidual tissues. Overexpression of miR-101-5p impaired the migration and invasion of HTR8/SVneo cells. DUSP6 was identified as a potential downstream target of miR-101-5p. The expression of miR-101-5p was negatively correlated with DUSP6 expression in HTR8/SVneo cells, and miR-101-5p directly bound to the 3′ UTR region of DUSP6. DUSP6 upregulation rescued the migratory and invasive abilities of HTR8/SVneo cells in the presence of miR-101-5p overexpression. Additionally, miR-101-5p downregulated DUSP6, resulting in enhanced ERK1/2 phosphorylation.

Conclusion

This study revealed that miR-101-5p inhibits the migration and invasion of HTR8/SVneo cells by regulating the DUSP6-ERK1/2 axis, providing a new molecular mechanism for the pathogenesis of PE.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10815-023-02846-4.

Keywords: Preeclampsia, miR-101-5p, DUSP6, ERK1/2, Migration, Invasion

Introduction

Preeclampsia (PE) is a pregnancy disorder characterized by newly onset hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg) along with proteinuria or end-organ dysfunction after 20 weeks of gestation. It is a major cause of maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity worldwide, accounting for 3–5% of cases [1, 2]. The pathogenesis of PE is not yet fully understood, but it is believed to involve dysregulated trophoblast cell behaviors, resulting in defective placentation and maternal systemic endothelial dysfunction [3–5]. Therefore, understanding the mechanisms of trophoblast cell dysfunction is crucial to reduce the incidence of PE.

microRNAs (miRNAs) are small endogenous non-coding RNAs, 19–25 nucleotides in size, that can regulate protein synthesis post-transcriptionally by binding to the 3′ UTRs of the target mRNAs through complementary base pairing [6]. Extensive research has demonstrated the involvement of miRNAs in diverse biological processes, including differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis, thereby contributing to the development of human diseases [7]. In the context of PE, the dysregulation of miRNAs has been linked to alterations in trophoblast cell behaviors essential for normal placental development [8–10]. One miRNA of particular interest is miR-101-5p, which has been identified as playing a significant role in the onset and progression of various malignancies, including breast cancer (BrCa) and cervical cancer. Its regulatory effects encompass critical cellular processes such as growth, metastasis, proliferation, invasion, and migration of cancer cells [11, 12]. Notably, trophoblast cells share behavioral similarities with cancer cells [13], which raises the possibility that miR-101-5p may also contribute to the development of PE. However, the specific impact of miR-101-5p on trophoblast cell functions in the context of PE remains unclear, warranting further investigation.

Using online databases (TargetScan, miRDB, and mirDIP) and transcriptomic technology, we identified dual-specificity protein phosphatase 6 (DUSP6) as a potential target of miR-101-5p. DUSP6, also known as HH19, MKP3, and PYST1, specifically dephosphorylates and inactivates the classical ERK1 and ERK2 MAPKs [14]. Previous studies have shown that DUSP6 is essential for normal placental formation and that its expression is reduced in response to ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury, which is a common in vitro model of PE [15]. Additionally, in mice, Tfap2c regulates its target gene Dusp6, and the loss of Tfap2c led to severe placental abnormalities, including growth arrest of the junctional zone and a reduced trophoblast population [16]. Therefore, we hypothesized that miR-101-5p and DUSP6 may be involved in the development of PE by regulating the biological functions of trophoblast cells.

To test our hypothesis, we analyzed the expression levels and localization of miR-101-5p in PE placental tissues and investigated the impact of miR-101-5p on trophoblast cell function and the interplay between miR-101-5p and DUSP6 in the HTR8/SVneo cell line.

Materials and methods

Placental tissue collection

Placental tissues were collected from 12 normal pregnant women and 12 patients with preeclampsia who underwent cesarean delivery at the Department of Obstetrics of the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University. The specimens were processed according to Burton et al. [17]. PE was diagnosed based on the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) guidelines [18], which state about patients with new-onset hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg) after 20 weeks of gestation accompanied by proteinuria, or without proteinuria but with end-organ dysfunction, including thrombocytopenia, renal failure, liver dysfunction, and pulmonary edema. Patients with gestational diabetes mellitus, chronic hypertension, spontaneous abortion, immune diseases, or other metabolic diseases were excluded. The clinical characteristics of the participants are presented in Table S1. This study was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Cell culture

The immortalized human trophoblast cell line HTR8/SVneo was acquired from the American Type Culture Collection (CRL-3271™, Manassas, VA, USA) and cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (PAN, Germany) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

A total RNA isolation was performed using TRIzol (Invitrogen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol to extract RNA from placental tissues or HTR8/SVneo cells. The RNA concentration was measured using ultraviolet spectroscopy (NanoDrop2000, Thermo, MA, USA). To measure miR-101-5p or the internal control U6 in clinical samples and cells, the Mir-X miRNA First-Strand Synthesis Kit (Takara, USA) was used to synthesize the cDNA from 1.0 μg RNA following the manufacturer’s instructions. For measuring mRNA levels, 1.0 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the PrimeScript™ RT reagent kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. qRT-PCR was carried out using the TB Green® Premix Ex Taq™ II Kit (Takara, Japan) on a CFX Connect Real-Time System (Bio-Rad, USA). Table S2 lists the primer sequences for PCR. The miRNA PCR cycling conditions consisted of predenaturation at 95°C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s, 63.3°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 20 s, while the mRNA PCR cycling conditions consisted of predenaturation at 95°C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s, 63.3°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 20 s. The relative expression was determined using the 2−△△CT method, and all experiments were performed in triplicate.

RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)-protein immunofluorescence (IF) double labeling (FISH/IF)

Double labeling of FISH/IF was performed to investigate the co-localization of miR-101-5p and cytokeratin-7 (CK-7) or HLA-G on sections of human placental or decidual tissues. FISH was conducted prior to IF using a Cy3-labeled probe for miR-101-5p (5′-AGCATCAGCACTGTGATAACTG-3′) that was designed and synthesized by GenePharma (Shanghai, China). The signals were detected with a FISH kit (GenePharma, Shanghai, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. After hybridization with the miR-101-5p probe, the IF assay was performed as follows: frozen placental or decidual sections were washed in 2 × SSC and 1 × SSC, and then blocked with 5% BSA (Beyotime, Beijing, China) at room temperature for 1 h. The sections were then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against CK-7 (1:100, #GB12225, Servicebio, Wuhan, China) or HLA-G (1:100, 66447-1-lg, Proteintech, China). The next day, after washing with PBS, the sections were blocked with 0.5% BSA and incubated for 1 h with the appropriate secondary antibody at room temperature. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI for 10 min at room temperature, and images were captured using an Evos FL Color Imaging System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA).

Transfection

miR-101-5p mimics, inhibitors, and their respective negative controls were designed and synthesized by GenePharma (Shanghai, China) and their sequences are shown in Table S3. Plasmids containing DUSP6 overexpression (pcDNA3.1-DUSP6) and a mock vector without DUSP6 sequence (pcDNA3.1) were purchased from Hanbio Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). HTR8/SVneo cells were seeded onto 6-well plates with a density of 2×105/well 1 day before transfection. After the cells reached 70 to 90% confluence, transient transfection of miR-101-5p mimics or inhibitors (GenePharma, Shanghai, China) or DUSP6 plasmids (Hanbio, Shanghai, China) was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The cells were harvested for further studies during the 24 to 48 h after transfection.

Wound-healing assay

After HTR8/SVneo cells grew to 90% confluence in 6-well plates, the monolayer was scratched using a 200-μL pipette tip. The cells were then gently washed with PBS, and fresh serum-free medium was added before returning the cells to the incubator for 24 h. Images were captured at 0 and 24 h, and the wound-healing area was calculated using ImageJ 1.53o software. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

Invasion assay

Invasion assays were conducted using 24-well transwell chambers (Falcon, USA) with 8 μm pore size and precoated with 60 μL of 1 mg/mL Matrigel matrix solution per chamber (BD Biosciences, USA). A suspension of 5×104 transfected HTR8/SVneo cells in 200 μL of serum-free culture medium was added to the upper transwell chambers, while the lower chambers were loaded with 600 μL of culture medium containing 10% FBS. After 24 h, the chambers were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with crystal violet boric acid. Non-invading HTR8/SVneo cells were gently removed from the upper side of the membrane with a sterile cotton swab. Images were captured using the Evos FL Color Imaging System. The Evos FL Color Imaging System was used to capture images, and ImageJ 1.53o software was used to count invaded cells. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) staining

The EdU assay was performed using the Cell-Light EdU Apollo567 In Vitro Kit (RiboBio, Guangzhou, China). After transfecting HTR8/SVneo cells with miR-101-5p mimics or inhibitors for 48 h, 8×103 cells were seeded in each well of a 96-well plate. A total of 100 μL of 50 μM EdU medium was added to each well and incubated for 2 h. Cells were then fixed with 50 μL of 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 30 min, and the excessive aldehyde groups were neutralized with 50 μL of 2 mg/mL glycine for 5 min on the shaker. After washing with PBS, cells were treated with 100 μL of 0.5% TritonX-100. HTR8/SVneo cells were then incubated with 100 μL of 1X Apollo® dyeing solution for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI for 10 min at room temperature. Images were captured using an Evos FL Color Imaging System, and cell counts were analyzed using ImageJ 1.53o software.

Flow cytometry

To assess apoptosis in HTR8/SVneo cells, we used flow cytometry using a CytoFlex Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Cells were treated with miR-101-5p mimics or inhibitors and their respective negative controls for 48 h before being detached using 0.25% trypsin-EDTA, resuspended in PBS, and centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min. Next, 1×106 cells were resuspended in 500 μL PBS and incubated with PI and Annexin V-FITC solution to detect apoptosis. CytExpert_2.4 software was used to analyze the data.

Transcriptomics and bioinformatic analysis

HTR8/SVneo cells were grown to 70–90% confluence and transfected with miR-101-5p mimics or inhibitors for 24 h. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen, USA), and RNA quality and quantity were assessed using the Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). Three independent replicates were performed for each experimental condition. To prepare sequencing libraries, the NEBNext® Ultra™ RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® (NEB, USA) was used following the manufacturer’s protocols. Differential expression analysis was conducted using the DESeq2 R package (1.20.0). Genes with an adjusted P-value < 0.05 were considered differentially expressed. Enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes was performed using the ClusterProfiler software, including Gene Ontology and pathway analysis. Results were considered statistically significant at a false discovery rate (FDR) of < 0.05.

Western blotting

Total proteins were extracted from placental tissues and HTR8/SVneo cells using RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) supplemented with 1% phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and 1% phosphatase inhibitors (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Protein concentrations were measured using the BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China), and standardized to 1 μg/μL for each sample. The lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE (Bio-Rad, USA) and transferred to PVDF membranes (Roche, Germany). The blots were blocked with 5% nonfat milk (Bio-Rad, USA) in TBST and incubated with primary antibodies against DUSP6 (ab76310, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), p-ERK1/2 (28733-1-AP, Proteintech, China), ERK1/2 (sc-514302, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, TX, USA), α-tubulin (GB11200, Servicebio, Wuhan, China), or β-actin (66009-1-lg, Proteintech, China) overnight at 4°C. After washing with TBST, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (ZB-2305, ZSGB-BIO, China) or goat anti-rabbit IgG (ZB-2301, ZSGB-BIO, China) at room temperature for 1 h. Protein bands were detected using the WesternBright™ ECL kit (K-12045-D10, Advansta, USA), and images were captured and analyzed using the Quantity One System image analyzer (Bio-Rad, USA).

Dual-luciferase reporter assay

The target sites of DUSP6 binding to miR-101-5p were predicted using TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org). To validate the predicted target sites, we synthesized plasmids containing the wild-type or mutation DUSP6 3′ UTR sequence, which were obtained from Hanbio Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). HTR8/SVneo cells were seeded into a 24-well plate at a density of 2.5×104 per well and transfected with NC or miR-101-5p mimics, in combination with either WT-DUSP6-3′ UTR or MUT-DUSP6-3′ UTR plasmids, using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). After transfection for 48 h, cell lysates were prepared using the Dual-Luciferase® Reporter Assay System (Promega, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The luminescence signal was measured using a luminometer (Tecan Spark, Swiss). Each experiment was repeated three times to ensure reproducibility.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Placental tissue sections were heated at 60 °C for an hour, followed by deparaffinization in xylene. The sections were then rehydrated using a graded ethanol series and microwaved in citrate buffer. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% H2O2 at room temperature for 15 min. Primary antibodies against DUSP6 (1:100; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and CK-7 (1:100; Servicebio, Wuhan, China) were added to the sections and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The following day, sections were treated with secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase for 20 min at room temperature. The sections were then visualized by color development using freshly prepared DAB solution. Images were captured using an Evos FL color Imaging System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

Statistics

Each experiment was performed in triplicate, and the results were presented as the mean ± standard error for the sample mean (SEM). Statistical analysis for comparison between two groups was conducted using Student’s t-test, while one-way ANOVA was used for comparison among three or more groups. The threshold for statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001). All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

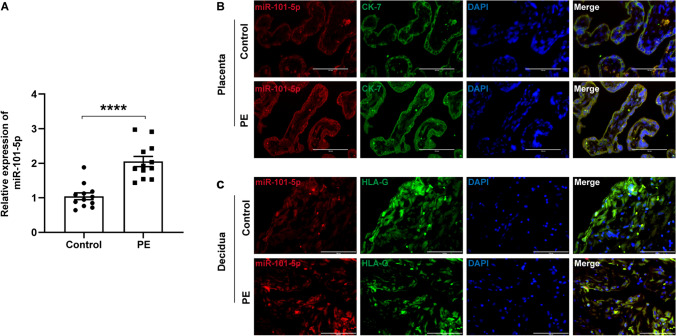

Expression and localization of miR-101-5p in placental tissues from PE patients

To investigate the role of miR-101-5p in the pathogenesis of PE, we initially assessed its relative expression level in placental tissues from PE patients (n = 12) and normal control placental tissues (n = 12) through qRT-PCR technology. Our results revealed a significant upregulation of miR-101-5p expression in preeclamptic placentas compared to normal controls (Fig. 1A). To further explore the expression patterns of miR-101-5p, we employed FISH/IF double labeling in normal control and preeclamptic placental and decidual tissues. CK-7 and HLA-G were utilized as markers for trophoblast cells and extravillous trophoblasts (EVTs), respectively. Our data demonstrated that miR-101-5p was prominently localized in syncytiotrophoblasts (STBs) in the placenta and EVTs in the decidua of preeclamptic patients, as depicted in Fig. 1B and C. Based on these observations, our findings suggest that miR-101-5p is widely expressed and is remarkably upregulated in trophoblasts of pregnant women with PE.

Fig. 1.

Expression and localization of miR-101-5p in placental tissues. A qRT-PCR analysis of miR-101-5p expression in term placentas from normal controls (n=12) and PE pregnancies (n=12). The data were presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed by Student’s t-test. ****P<0.0001. B FISH/IF staining of miR-101-5p (red) and CK-7 (green) in term placentas. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 100 μm. C FISH/IF staining of miR-101-5p (red) and HLA-G (green) in term decidual tissues. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 100 μm

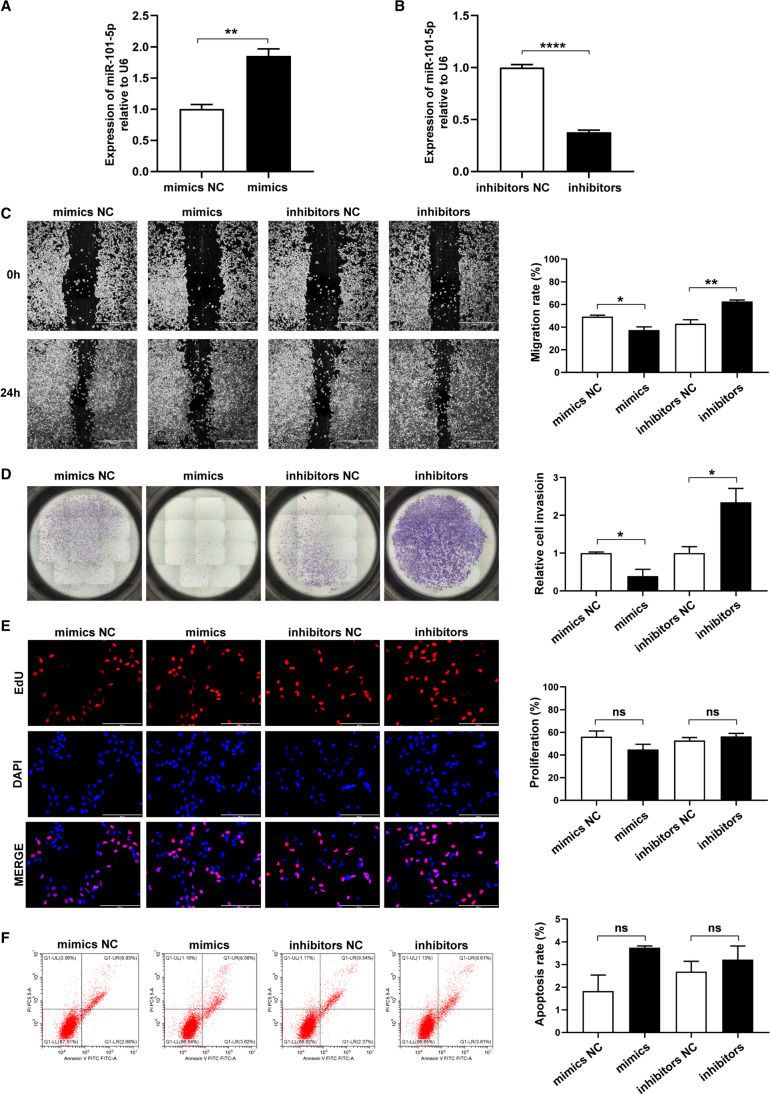

miR-101-5p regulates trophoblast cell migration and invasion

We found that miR-101-5p was upregulated in the preeclamptic placentas and mainly distributed in trophoblast cell subtypes. To investigate the effect of miR-101-5p on the biological functions of trophoblast cells, we performed a series of cell functional assays on HTR8/SVneo cells. Specifically, we transfected miR-101-5p mimics and inhibitors into HTR8/SVneo cells to increase and decrease miR-101-5p expression, respectively. Firstly, we confirmed the transfection efficiency using qRT-PCR, and the results showed a significant upregulation of miR-101-5p in the mimics group (P < 0.01, vs. mimics NC group) and downregulation in the inhibitors group (P < 0.0001, vs. inhibitors NC group) (Fig. 2A, B). We then evaluated the impact of miR-101-5p on HTR8/SVneo cell migration and invasion using wound-healing and transwell assays. Our data demonstrate that both migration and invasion were significantly inhibited in the mimics group compared to those in the mimics NC group (Fig. 2C, D). Conversely, the miR-101-5p inhibitor group showed enhanced migratory and invasive abilities in comparison to the inhibitor NC group (Fig. 2C, D). We also examined cell proliferation and apoptosis in HTR8/SVneo cells using EdU assay and flow cytometry. However, the results showed no significant impact of miR-101-5p on cell proliferation or apoptosis (Fig. 2E, F).

Fig. 2.

miR-101-5p regulated the migration and invasion of HTR8/SVneo cells. A, B qRT-PCR results for miR-101-5p expression in HTR8/SVneo cells transfected with mimics NC or miR-101-5p mimics (A) and inhibitors NC or miR-101-5p inhibitors (B). The relative expression of miR-101-5p was normalized to U6, which served as an internal reference. HTR8/SVneo cells transfected with mimics NC, miR-101-5p mimics, inhibitors NC, and miR-101-5p inhibitors were subjected to C wound-healing assays to measure the migration. Scale bar, 1000 μm. Images were taken at 0 h and after 24 h; D Matrigel transwell assays to detect the invasion; E EdU assays to measure the proliferation, with the nuclei stained by DAPI (blue), while proliferating cells were stained by Azide594 (red); and F flow cytometry to detect apoptosis. Each experiment was independently repeated at least three times. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001, ns, not statistically significant, using one-way ANOVA and Student’s t-test

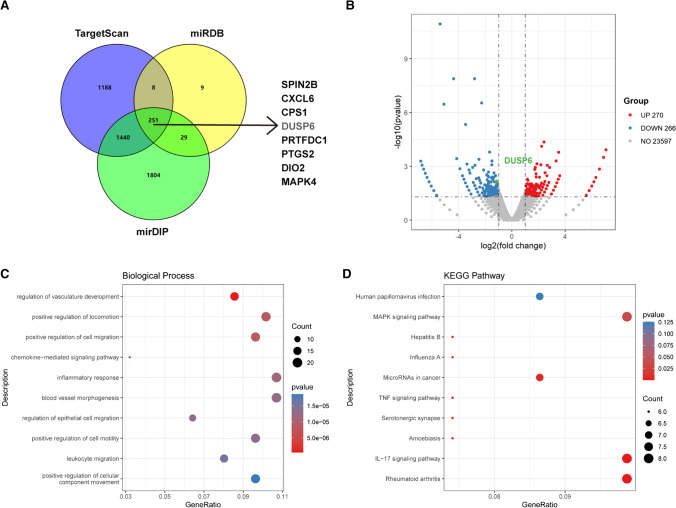

Identification of miR-101-5p-mRNA regulatory network in HTR8/SVneo cells

To explore the mechanistic basis of miR-101-5p-induced PE, we employed bioinformatics predictions and transcriptomic analyses. Three public miRNA datasets (TargetScan, miRDB, and mirDIP) were utilized to predict potential downstream target genes of miR-101-5p. The integration of these datasets yielded a total of 251 candidate target genes, as illustrated in Fig. 3A. We then conducted transcriptomic analyses of HTR8/SVneo cells transfected with miR-101-5p mimics or inhibitors. In comparison to cells transfected with miR-101-5p mimics, those transfected with inhibitors exhibited significant changes in the expression of 536 mRNAs (270 upregulated and 266 downregulated; Fig. 3B). Functional enrichment analyses of differentially expressed genes were then conducted using the Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) databases. The results of the GO analysis showed that miR-101-5p was involved in biological processes related to cell movement, such as vasculature development, regulation of locomotion, and cell migration (Fig. 3C). Similarly, the results of the KEGG analysis revealed that several classical pathways were significantly associated with miR-101-5p, including the MAPK, TNF, VEGF, and IL-17 signaling pathways (Fig. 3D). After cross-referencing the results of the public datasets and RNA sequencing, we identified DUSP6 as the specific target gene of miR-101-5p for further investigation.

Fig. 3.

Identification of downstream target genes and pathways related to miR-101-5p using bioinformatics and transcriptomics. A Prediction of potential miR-101-5p target genes using three miRNA databases (TargetScan, miRDB, and mirDIP). B Volcano plot showing the differentially expression of genes between HTR8/SVneo cells transfected with miR-101-5p mimics and inhibitors. C Classification of the Gene Ontology (GO) for the differentially expressed genes. D Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis for the differentially expressed genes

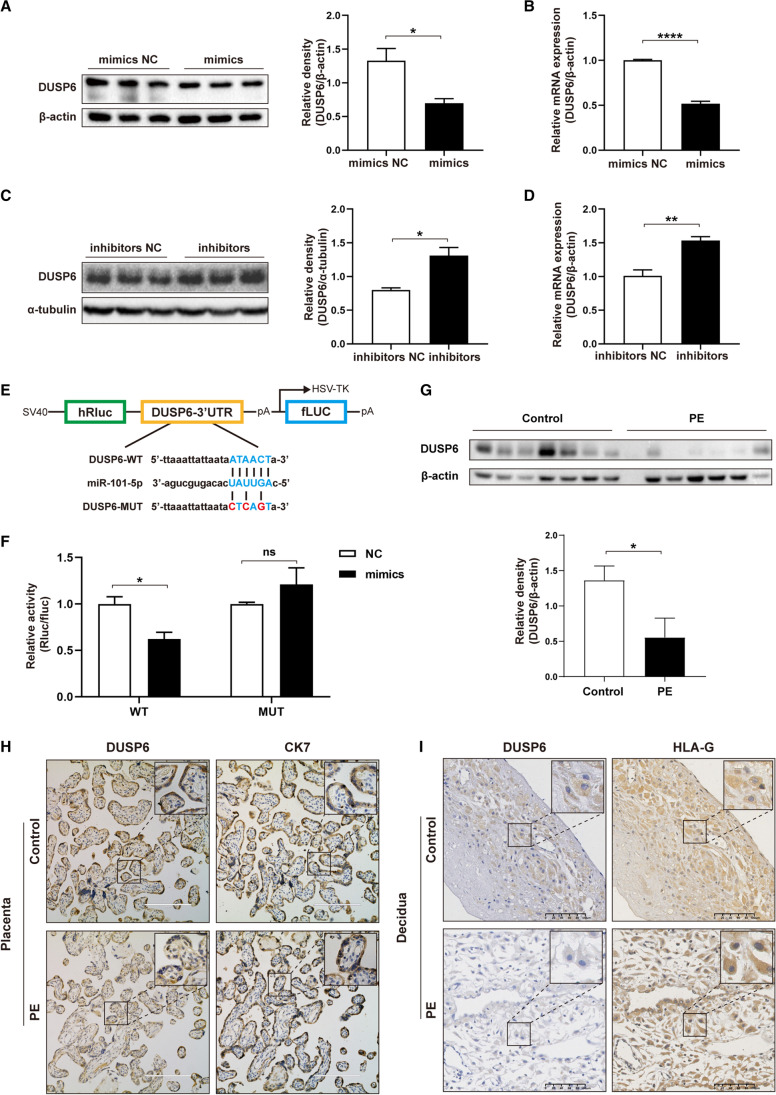

DUSP6 was a direct target of miR-101-5p in HTR8/SVneo cells

The overexpression of miR-101-5p resulted in a reduction of DUSP6 expression at both protein and mRNA levels, as demonstrated in Fig. 4A and B. Conversely, the inhibition of miR-101-5p led to an increase in DUSP6 expression at both protein and mRNA levels, as shown in Fig. 4C and D. Using bioinformatic analysis of the TargetScan dataset, we identified that the seed sequence of miR-101-5p was complementary to 1174–1180 nt of 3′ UTR in DUSP6 mRNA (Fig. 4E). To confirm that DUSP6 was the direct target of miR-101-5p, we conducted dual-luciferase reporter assays in HTR8/SVneo cells. Wild-type DUSP6 (WT-DUSP6) and mutated-type DUSP6 (MUT-DUSP6) vectors were co-transfected with either mimics NC or miR-101-5p mimics for 48 h. Our results showed that miR-101-5p mimics significantly reduced the relative luciferase activity of the WT-DUSP6, but had no effect on the relative luciferase activity of MUT-DUSP6 when compared to the NC (Fig. 4F). These findings confirmed that DUSP6 is a direct target of miR-101-5p.

Fig. 4.

DUSP6 is a direct target of miR-101-5p in HTR8/SVneo cells. A, B Protein and mRNA levels of DUSP6 were measured by western blotting (A) and qRT-PCR (B) after transfection with mimics NC and miR-101-5p mimics into HTR8/SVneo cells. C, D Protein and mRNA levels of DUSP6 were measured by western blotting (C) and qRT-PCR (D) after transfection with inhibitors NC and miR-101-5p inhibitors in HTR8/SVneo cells. E Schematic diagram of plasmid vector (pSI-Check2) showing the predicted binding sites of miR-101-5p in the 3′ UTR of DUSP6 and the corresponding mutated sites. F Dual-luciferase reporter assay was performed to detect the luciferase activity of HTR8/SVneo cells co-transfected with mimics NC or miR-101-5p mimics and WT-DUSP6 or MUT-DUSP6. G Detection of DUSP6 expression in control and PE placental tissues using western blot. H IHC staining of DUSP6 and CK-7 in control and PE placentas. Scale bar: 100 μm. I IHC staining of DUSP6 and HLA-G in control and PE decidual tissues. Scale bar: 100 μm. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Data were analyzed using Student’s t-test and presented as mean ± SEM. ns, not statistically significant; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001; 3′ UTR, 3′ untranslated region

Subsequently, we validated DUSP6 expression in control and PE placental tissues, as depicted in Fig. 4G. Notably, DUSP6 exhibited a significant downregulation in PE placental tissues compared to control placentas (P < 0.05). Furthermore, the IHC analysis revealed a distinct co-localization pattern of DUSP6 with CK-7 within the STB compartments of the placental tissues, as shown in Fig. 4H. Additionally, within the decidual tissues, DUSP6 exhibited co-localization with HLA-G in the EVT (Fig. 4I).

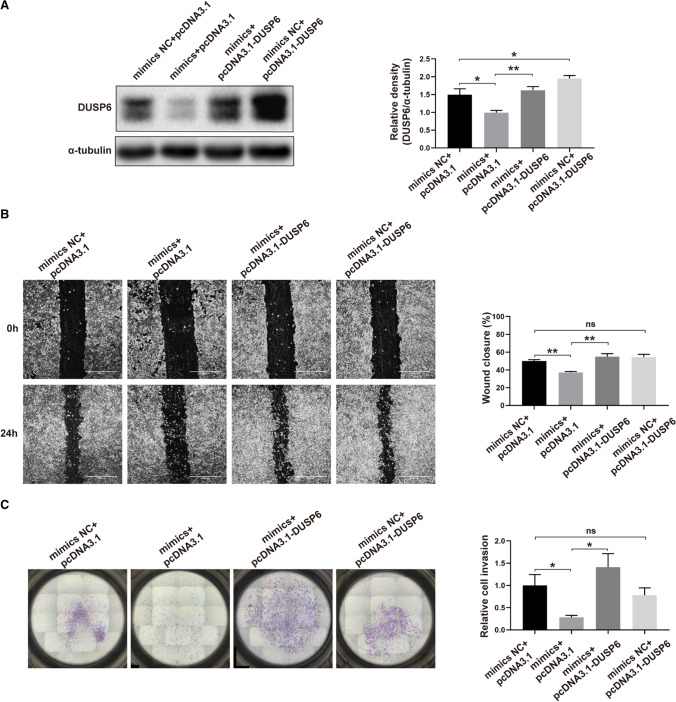

miR-101-5p inhibits HTR8/SVneo cell migration and invasion by regulating DUSP6 expression

To investigate whether miR-101-5p suppresses DUSP6 expression and affects trophoblast function, we conducted a series of functional rescue experiments. HTR8/SVneo cells were divided into four groups and transfected with mimics NC + pcDNA3.1, mimics + pcDNA3.1, mimics + pcDNA3.1-DUSP6, and mimics NC + pcDNA3.1-DUSP6. Western blotting analysis showed that DUSP6 expression was substantially lower in the mimics + pcDNA3.1 group than in the mimics NC+pcDNA3.1 group and statistically higher in the mimics + pcDNA3.1-DUSP6 group than in the mimics + pcDNA3.1 group (Fig. 5A). To further validate that DUSP6 rescues miR-101-5p-induced impairments in HTR8/SVneo cell migration and invasion, we measured the migration and invasion abilities of each group. Our findings revealed that the migration and invasion abilities of the mimics+pcDNA3.1 group were significantly reduced compared to the mimics NC+pcDNA3.1 group, while they were significantly restored in the mimics+pcDNA3.1-DUSP6 group (Fig. 5B, C). Based on the results of these experiments, we conclude that miR-101-5p inhibits the migration and invasion of HTR8/SVneo cells by regulating DUSP6 expression.

Fig. 5.

miR-101-5p regulates DUSP6 to affect the migration and invasion of HTR8/SVneo cells. HTR8/SVneo cells were co-transfected with mimics NC + pcDNA3.1, miR-101-5p mimics + pcDNA3.1, miR-101-5p mimics + pcDNA3.1-DUSP6, and mimics NC + pcDNA3.1-DUSP6, and subjected to the following assays: A western blotting to detect the protein level of DUSP6; B wound-healing assays to measure the migration ability (scale bar, 1000 μm); C Matrigel transwell assays to assess the invasion ability. Each experiment was performed in triplicate. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. ns, not statistically significant; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, using one-way ANOVA and Student’s t-test

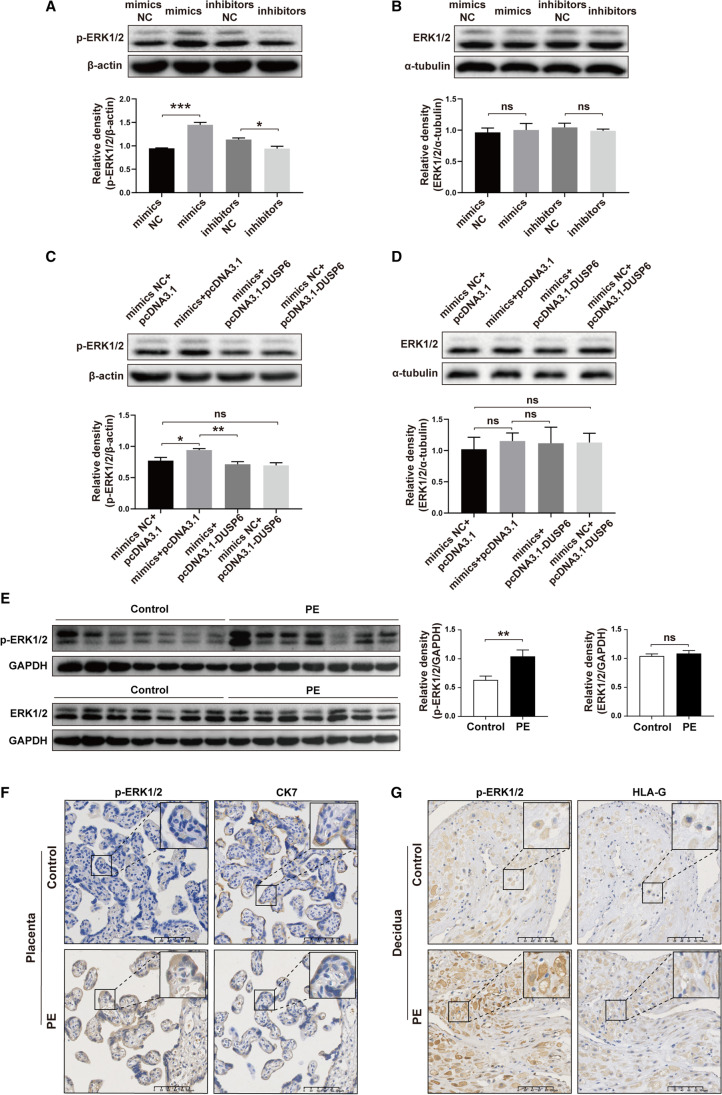

miR-101-5p suppresses DUSP6 expression and activates ERK1/2 in HTR8/SVneo cells

DUSP6 is a member of the dual-specificity protein phosphatase subfamily that inactivates target kinases, including ERK1/2. In this study, we aimed to explore if miR-101-5p suppresses DUSP6 expression in HTR8/SVneo cells, leading to altered ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Western blotting assay revealed that miR-101-5p mimics increased ERK1/2 phosphorylation, which was blocked by miR-101-5p inhibitors (Fig. 6A). However, neither miR-101-5p mimics nor inhibitors affected the total protein expression level of ERK1/2 (Fig. 6B). To investigate whether DUSP6 can restore ERK1/2 activation induced by miR-101-5p, we performed a western blotting assay. As shown in Fig. 6C, miR-101-5p increased ERK1/2 phosphorylation, which was reversed by DUSP6. Importantly, the total ERK1/2 protein level remained unaffected (Fig. 6D). These results demonstrated that miR-101-5p downregulates DUSP6 expression, leading to activation of ERK1/2.

Fig. 6.

miR-101-5p activates ERK1/2 by regulating DUSP6 expression. A, B Western blotting was used to detect the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (A) and the total protein level of ERK1/2 (B) after transfection with mimics NC, miR-101-5p mimics, inhibitors NC, and miR-101-5p inhibitors. C, D Western blotting was performed to measure the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (C) and the total protein level of ERK1/2 (D) after co-transfection with mimics NC + pcDNA3.1, miR-101-5p mimics + pcDNA3.1, miR-101-5p mimics + pcDNA3.1-DUSP6, and mimics NC + pcDNA3.1-DUSP6. E The expression of p-ERK1/2 and total ERK1/2 in control and PE placental tissues was detected using western blot. F IHC staining of p-ERK1/2 and CK-7 was performed in control and PE placental tissues. Scale bar: 100 μm. G IHC staining of p-ERK1/2 and HLA-G was conducted in control and PE decidual tissues. Scale bar: 100 μm. All experiments were replicated in triplicate. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; ns, not statistically significant; ns, not statistically significant. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 using one-way ANOVA and Student’s t-test

In addition, we investigated the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and the expression of total ERK1/2 in control and PE placental tissues. As illustrated in Fig. 6E, the phosphorylation level of ERK1/2 was significantly upregulated in PE placental tissues compared to control placentas, while the total ERK1/2 expression showed no difference between the two groups. Subsequently, IHC staining was conducted to explore the precise localization of p-ERK1/2 in placental and decidual tissues. In accordance with the localization patterns of miR-101-5p and DUSP6, p-ERK1/2 predominantly localized within the STB compartments of the placental tissues, as well as within the EVT of the decidual tissues (Fig. 6F, G).

Discussion

PE is a life-threatening complication during pregnancy with complex and not fully understood causes involving multiple factors and pathways. The classical two-stage theory posits a connection between PE and aberrant trophoblast cell function, leading to impaired uterine spiral artery remodeling, inadequate placental development, and ischemia [19]. Trophoblast cell function is tightly regulated by a diverse array of molecules and pathways, among which miRNAs exert significant influence as potent modulators of gene expression. Certain miRNAs, including miR-210 [20], miR-486-5p [21], and miR-362-3p [22], impede trophoblast cell invasion or migration, while others such as miR-145-5p [23], miR-221-3p [24], and miR-18a [25] facilitate these processes by modulating pivotal signaling pathways. Recent investigations have revealed significant differences in the expression of multiple miRNAs in PE placental tissues, underscoring their pivotal role in controlling critical mechanisms such as angiogenesis, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and immune tolerance [26]. Consequently, comprehending the functional significance of these dysregulated miRNAs assumes paramount importance in discerning key pathways associated with PE. Therefore, the recognition of studying miRNAs in this context is steadily gaining prominence. In our investigation, we have identified miR-101-5p as a novel miRNA implicated in PE, exerting inhibitory effects on trophoblast cell invasion and migration through the regulation of the DUSP6-ERK1/2 pathway and contributing to the pathogenesis of PE.

miR-101-5p is widely recognized as a tumor suppressor miRNA that exerts its effects in various malignant tumors. Previous studies have shown that miR-101-5p is downregulated in NSCLC tissues, leading to decreased proliferation, migration, and invasion of NSCLC cells, as well as reduced metastasis and tumor growth in vivo [27]. In addition, overexpression of miR-101-5p induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) cells [28]. Notably, malignant cells and trophoblast cells have strikingly similar biological functions and regulatory mechanisms [13]. Encouragingly, our study reveals a significant upregulation of miR-101-5p in PE placental tissue, specifically localized within various subtypes of trophoblast cells. Consistent with prior research findings, our investigation demonstrates the inhibitory role of miR-101-5p in the migration and invasion of trophoblast cells, while having no impact on their proliferation and apoptosis. These findings further underscore the distinctive functional significance of miR-101-5p in placental trophoblast cells within the context of PE.

To gain deeper insights into the gene regulatory network involving miR-101-5p in trophoblast cells, we employed online databases for predictions and conducted transcriptomic analysis. Collectively, three databases predicted complementary binding sites between the 3′ UTR of DUSP6 mRNA and miR-101-5p. Our transcriptomic data revealed a significant downregulation of DUSP6 expression in the miR-101-5p mimics group, while the inhibitor group exhibited a significant upregulation. Consequently, we identified DUSP6 as a downstream target gene of miR-101-5p for further investigation. Our research findings demonstrate the direct binding of miR-101-5p to the mRNA of DUSP6, leading to the inhibition of its post-transcriptional expression. Specifically, we observed that miR-101-5p reduced the mRNA and protein expression levels of DUSP6. Furthermore, dual-luciferase reporter gene assays confirmed the direct binding of miR-101-5p to the 3′ UTR of the DUSP6 gene. Notably, DUSP6 exhibited significant downregulation in PE placental tissue, with its localization corresponding to that of miR-101-5p, expressed in the STB cells of placental tissues and EVT cells of decidual tissues. This co-localization further supports the significant role of DUSP6 in regulating trophoblast cell functions, while miR-101-5p may modulate the invasion and migration of trophoblast cells through its mediation of DUSP6. Rescue experiments confirmed that upregulating DUSP6 under conditions of miR-101-5p overexpression can restore the migration and invasion capabilities of trophoblast cells. This further validates the impact of miR-101-5p on the invasion and migration functions of trophoblast cells through its interaction with DUSP6.

DUSP6, also known as MAPK phosphatase-3 (MKP-3), is capable of specifically dephosphorylating ERK1/2 at tyrosine and serine/threonine residues, resulting in their inactivation [29]. Evidence suggests that DUSP6 is involved in cancer cell invasion and migration. In gastric cancer, high DUSP6 expression has been linked to poor outcomes, and silencing endogenous DUSP6 can suppress the invasion and migration abilities of SGC7901 and BGC823 cell lines [30]. Similarly, in endometrial cancer, DUSP6 is necessary for the invasion and metastasis of cancer cells, and shRNA-mediated DUSP6 knockdown can significantly attenuate the invasion and migration of Hec1 and HHUA cells [31]. In our study, transcriptomic analysis revealed significant enrichment of downstream target genes regulated by miR-101-5p in the MAPK signaling pathway. This strongly indicates the involvement of the DUSP6-ERK1/2 axis in the regulation of invasion and migration in trophoblast cells. Previous research has shown the involvement of the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway in the development of PE. LPS, commonly used to induce PE phenotypes, reduces cell migration and invasion in LPS-treated HTR8/SVneo cells, and upregulates phosphorylation of ERK1/2 [32]. Szilvia et al. found that the average immunoscore of p-ERK1/2 was higher in preterm PE complicated with HELLP syndrome compared to the control group, and hypoxia enhanced ERK1/2 activity in BeWo cells [33]. Consistent with previous studies, we observed a significant upregulation of ERK1/2 phosphorylation levels in PE placental tissue, but no significant difference in total ERK1/2 levels between the two groups. Additionally, the localization of ERK1/2 is consistent with that of miR-101-5p and DUSP6, all being expressed in various subtypes of trophoblast cells within placental and decidual tissues. This further suggests abnormal activation of ERK1/2 in trophoblast cells of PE, potentially mediated by the aberrant expression of miR-101-5p and DUSP6. Furthermore, we also observed that miR-101-5p overexpression activates ERK1/2 phosphorylation, which can be inhibited by miR-101-5p inhibitors. Moreover, altering the expression of miR-101-5p in HTR8/SVneo cells did not affect the overall protein level of ERK1/2. Importantly, rescue experiments confirmed that DUSP6 can reverse the activation of ERK1/2 caused by miR-101-5p overexpression. These experimental data further support the abnormal expression of the miR-101-5p-DUSP6-ERK1/2 axis in placental tissue of PE and its involvement in regulating the invasive and migratory capabilities of trophoblast cells, contributing to the pathogenesis of PE.

Our study has several strengths. Firstly, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that has discovered the involvement of the miR-101-5p/DUSP6/ERK1/2 axis in the progression of PE. Moreover, we have comprehensively explored the effects of miR-101-5p on trophoblast cell migration, invasion, proliferation, and apoptosis in the HTR8/SVneo cell line. Additionally, we have combined transcriptomics to fully reveal the potential mechanism by which miR-101-5p affects the functions of trophoblast cells. However, our study has some limitations that must be considered. Firstly, we only selected DUSP6 as the downstream target of miR-101-5p. Future studies should investigate other target genes and potential mechanisms related to miR-101-5p involved in the pathogenesis of PE. Secondly, our study only explored the effect of miR-101-5p on trophoblast cells in vitro. Therefore, further in vivo studies on miR-101-5p are needed in the future.

In conclusion, our results demonstrated that miR-101-5p suppresses the invasion and migration of trophoblast cells via the DUSP6-ERK1/2 axis. This, thus, may provide a novel molecular mechanism for the pathogenesis of PE.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Tables (DOCX 15 kb)

Supplementary Figures (DOCX 3822 kb)

Author contribution

Conceptualization: Jiacheng Xu; methodology: Jiacheng Xu; investigation: Jiacheng Xu, Jie Wang, Miaomiao Chen; software: Bingdi Chao, Jie He; writing-original draft: Jiacheng Xu; writing-review and editing: Jie Wang; Xin Luo; funding acquisition: Yuxiang Bai, Xiaofang Luo, Xin Luo; formal analysis: Hongli Liu, Lumei Xie; validation: Yuelan Tao; supervision: Hongbo Qi, Xin Luo.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82171668, No. 81771614, No. 82171662, No. 81901506, No. 82001581) and Joint Funds of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. U21A20346).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jiacheng Xu and Jie Wang have contributed equally to this work and share the first authorship.

Contributor Information

Hongbo Qi, Email: qihongbocy@gmail.com.

Xin Luo, Email: 14802315@qq.com.

References

- 1.Chappell LC, Cluver CA, Kingdom J, Tong S. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2021;398:341–354. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32335-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mol BWJ, Roberts CT, Thangaratinam S, Magee LA, de Groot CJM, Hofmeyr GJ. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2016;387:999–1011. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burton GJ, Redman CW, Roberts JM, Moffett A. Pre-eclampsia: pathophysiology and clinical implications. BMJ. 2019;366:l2381 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Ji L, Brkić J, Liu M, Fu G, Peng C, Wang Y-L. Placental trophoblast cell differentiation: physiological regulation and pathological relevance to preeclampsia. Mol Aspects Med. 2013;34:981–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duan F-M, Fu L-J, Wang Y-H, Adu-Gyamfi EA, Ruan L-L, Xu Z-W, et al. THBS1 regulates trophoblast fusion through a CD36-dependent inhibition of cAMP, and its upregulation participates in preeclampsia. Genes Dis. 2021;8:353–363. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2020.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartel DP. microRNAs. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mendell JT, Olson EN. microRNAs in stress signaling and human disease. Cell. 2012;148:1172–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lykoudi A, Kolialexi A, Lambrou GI, Braoudaki M, Siristatidis C, Papaioanou GK, et al. Dysregulated placental microRNAs in early and late onset preeclampsia. Placenta. 2018;61:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2017.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu P, Zhao Y, Liu M, Wang Y, Wang H, Li Y, et al. Variations of microRNAs in human placentas and plasma from preeclamptic pregnancy. Hypertension. 2014;63:1276–1284. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.02647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu X, Han T, Sargent IL, Yin G, Yao Y. Differential expression profile of microRNAs in human placentas from preeclamptic pregnancies vs normal pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:661.e1–661.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toda H, Seki N, Kurozumi S, Shinden Y, Yamada Y, Nohata N, et al. RNA-sequence-based microRNA expression signature in breast cancer: tumor-suppressive miR-101-5p regulates molecular pathogenesis. Mol Oncol. 2020;14:426–446. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen W, Xie X-Y, Liu M-R, Wang L-L. microRNA-101-5p inhibits the growth and metastasis of cervical cancer cell by inhibiting CXCL6. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2019;23:1957–1968. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201903_17234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferretti C, Bruni L, Dangles-Marie V, Pecking AP, Bellet D. Molecular circuits shared by placental and cancer cells, and their implications in the proliferative, invasive and migratory capacities of trophoblasts. Hum Reprod Update. 2006;13:121–141. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dml048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caunt CJ, Keyse SM. Dual-specificity MAP kinase phosphatases (MKPs): shaping the outcome of MAP kinase signalling. FEBS J. 2013;280:489–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08716.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu G, Tan J, Li J, Sun X, Du L, Tao S. miRNA-145-5p induces apoptosis after ischemia-reperfusion by targeting dual specificity phosphatase 6. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:16281–16289. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma N, Kubaczka C, Kaiser S, Nettersheim D, Mughal SS, Riesenberg S, et al. Tpbpa-Cre-mediated deletion of TFAP2C leads to deregulation of Cdkn1a, Akt1 and the ERK pathway, causing placental growth arrest. Development. 2016;143(5):787–98. doi: 10.1242/dev.128553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burton GJ, Sebire NJ, Myatt L, Tannetta D, Wang Y-L, Sadovsky Y, et al. Optimising sample collection for placental research. Placenta. 2014;35:9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.ACOG Practice Bulletin No 203 Chronic hypertension in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e26–e50. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Staff AC The two-stage placental model of preeclampsia: an update. J Reprod Immunol. 2019;134–135:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2019.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anton L, Olarerin-George AO, Schwartz N, Srinivas S, Bastek J, Hogenesch JB, et al. miR-210 inhibits trophoblast invasion and is a serum biomarker for preeclampsia. Am J Pathol. 2013;183:1437–1445. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taga S, Hayashi M, Nunode M, Nakamura N, Ohmichi M. miR-486-5p inhibits invasion and migration of HTR8/SVneo trophoblast cells by down-regulating ARHGAP5. Placenta. 2022;123:5–11. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2022.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang N, Feng Y, Xu J, Zou J, Chen M, He Y, et al. miR-362-3p regulates cell proliferation, migration and invasion of trophoblastic cells under hypoxia through targeting Pax3. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;99:462–468. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.01.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lv Y, Lu X, Li C, Fan Y, Ji X, Long W, et al. miR-145–5p promotes trophoblast cell growth and invasion by targeting FLT1. Life Sci. 2019;239:117008. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.117008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang Y, Li H, Ma Y, Zhu X, Zhang S, Li J. miR-221-3p is down-regulated in preeclampsia and affects trophoblast growth, invasion and migration partly via targeting thrombospondin 2. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;109:127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu P, Li Z, Wang Y, Yu X, Shao X, Li Y, et al. miR-18a contributes to preeclampsia by downregulating Smad2 (full length) and reducing TGF-β signaling. Mol Ther - Nucleic Acids. 2020;22:542–556. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2020.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hemmatzadeh M, Shomali N, Yousefzadeh Y, Mohammadi H, Ghasemzadeh A, Yousefi M. microRNAs: small molecules with a large impact on pre-eclampsia. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235:3235–3248. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Q, Liu D, Hu Z, Luo C, Zheng SL. miRNA-101-5p inhibits the growth and aggressiveness of NSCLC cells through targeting CXCL6. OncoTargets Ther. 2019;12:835–848. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S184235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamada Y, Nohata N, Uchida A, Kato M, Arai T, Moriya S, et al. Replisome genes regulation by antitumor miR-101-5p in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2020;111:1392–1406. doi: 10.1111/cas.14327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kidger AM, Keyse SM. The regulation of oncogenic Ras/ERK signalling by dual-specificity mitogen activated protein kinase phosphatases (MKPs) Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2016;50:125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu Q-N, Liao Y-F, Lu Y-X, Wang Y, Lu J-H, Zeng Z-L, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of DUSP6 suppresses gastric cancer growth and metastasis and overcomes cisplatin resistance. Cancer Lett. 2018;412:243–255. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kato M, Onoyama I, Yoshida S, Cui L, Kawamura K, Kodama K, et al. Dual-specificity phosphatase 6 plays a critical role in the maintenance of a cancer stem-like cell phenotype in human endometrial cancer. Int J Cancer. 2020;147:1987–1999. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fan M, Li X, Gao X, Dong L, Xin G, Chen L, et al. LPS induces preeclampsia-like phenotype in rats and HTR8/SVneo cells dysfunction through TLR4/p38 MAPK pathway. Front Physiol. 2019;10:1030. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.01030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Szabo S, Mody M, Romero R, Xu Y, Karaszi K, Mihalik N, et al. Activation of villous trophoblastic p38 and ERK1/2 signaling pathways in preterm preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome. Pathol Oncol Res. 2015;21:659–668. doi: 10.1007/s12253-014-9872-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Tables (DOCX 15 kb)

Supplementary Figures (DOCX 3822 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.