Abstract

Glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78) is frequently and highly expressed in various human malignancies and protects cancer cells against apoptosis induced by multifarious stresses, particularly endoplasmic reticulum stress (ER stress). The inhibition of GRP78 expression or activity could enhance apoptosis induced by anti-tumor drugs or compounds. Herein, we will evaluate the efficacy of lysionotin in the treatment of human liver cancer as well as the molecular mechanism. Moreover, we will examine whether inhibition of GRP78 enhanced the sensitivity of hepatocellular carcinoma cells to lysionotin. We found that lysionotin significantly suppressed proliferation and induced apoptosis of liver cancer cells. TEM showed that lysionotin-treated liver cancer cells showed an extensively distended and dilated endoplasmic reticulum lumen. Meanwhile, the levels of the ER stress hallmark GRP78 and UPR hallmarks (e.g., IRE1α and CHOP) were significantly increased in response to lysionotin treatment in liver cancer cells. Moreover, the reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenger NAC and caspase-3 inhibitor Ac-DEVD-CHO visibly attenuated the induction of GRP78 and attenuated the decrease in cell viability induced by lysionotin. More importantly, the knockdown of GRP78 expression by siRNAs or treatment with EGCG, both induced remarkable increase in lysionotin-induced PARP and pro-caspase-3 cleavage and JNK phosphorylation. In addition, knockdown of GRP78 expression by siRNA or suppression GRP78 activity by EGCG both significantly improved the effectiveness of lysionotin. These data indicated that pro-survival GRP78 induction may contribute to lysionotin resistance. The combination of EGCG and lysionotin is suggested to represent a novel approach in cancer chemo-prevention and therapeutics.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12192-023-01358-5.

Keywords: Endoplasmic reticulum stress, Glucose-regulated protein 78, Liver cancer, Lysionotin, Apoptosis, Unfolded protein response

Introduction

Lysionotin is a kind of natural flavonoid, also known as nevadensin, which is mainly extracted from lysionotus (Gesneriaceae) herbs, such as lysionotus pauciflorus Maxim (Teng et al. 2017). Its structure is 5, 7-dihydroxy-4', 6, 8-trimethoxy flavone, and its melting point is 195~196 °C. It inhibits tuberculous bacteria in vitro. In particular, the bioactive properties of lysionotus focused on the anti-inflammatory effects and anti-microbial activity (Chen et al. 2002; Jiang et al. 2019). Additionally, lysionotin suppresses the growth rate of BEL-7404 hepatoma cells in a dose-dependent manner in vitro (Yang et al. 2021). In liver cancer cells, lysionotin obviously reduced cell viability, suppressed cell growth and migration, and promoted caspase-3 mediated mitochondrial apoptosis (Muller et al. 2021). However, the mechanism warrants further investigation. Findings from previous studies have shown that lysionotus can inhibit human colon carcinoma HT29 cells growth by blocking the cell cycle in the G2/M phase, eventually by inducing topoisomerase poisoning via the triggering of DNA damage and leading to apoptosis (Liu et al. 2019). Also, the activation of G protein-coupled receptor 30, leading to the expression of acetylcholinesterase in cultured PC12 cells, could be a potential strategy for the treatment of brain diseases (Li et al. 2009).

In recent years, endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-related apoptosis pathways have received increasing attention from researchers. The ER is the primary harbor for protein folding and modification, and its own protein synthesis quality control system is used to ensure correct protein folding and prevent unfolded or misfolded proteins from aggregating and accumulating in the ER lumen (Frakes and Dillin 2017; Kleizen and Braakman 2004). Certain physiological or pathological conditions, such as hypoxia, hunger, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, pH changes, and chemical drugs, can cause ER stress, which damages ER functions, such as protein folding ability, thus causing the accumulation of misfolded and unfolded proteins in the ER lumen (Diaz-Bulnes et al. 2019; Lin et al. 2019; Senft and Ronai 2015; Zeeshan et al. 2016). To eliminate or mitigate this damage, the ER rapidly initiates the unfolded protein response (UPR) (Gardner et al. 2013; Hetz 2012; Hetz et al. 2020).

UPR is an adaptive response of eukaryotic cells to ER stress. Its protective effects include termination of the majority of protein synthesis and reduction of ER load, which accelerates expression of the ER chaperones, such as GRP78, Calnexin, PDI, and GRP94, among others, for assistance in protein folding (Cudna and Dickson 2003; Jarosch et al. 2003; Pahl 1999). A moderate ER stress response helps protect cells, but when ER stress is persistent or too intense, apoptotic signaling pathways are activated, thus leading to apoptosis of damaged cells. ER stress induces apoptosis primarily by activating the expression of Caspase family proteins, inducing CHOP expression, or inducing apoptosis through the IRE1-TRAF2-JNK pathway (Kim and Kim 2018; Oyadomari and Mori 2004; Rao et al. 2001; Urano et al. 2000). The survival, injury, or apoptosis of cells under ER stress depends on the duration and intensity of stress stimulation and the balance between the protective and the apoptosis effects.

The increase in the expression of ER chaperone proteins, represented by GRP78, in tumor cells is one of the mechanisms for tumors to adapt to ER stress and survive. GRP78, as a representative chaperone protein of ER, normally binds to and inhibits three important stress-sensing proteins including, inositol requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1), protein kinase R-like ER kinase (PERK), and activating transcription factor-6 (ATF6). During stresses, GRP78 preferentially attaches to hydrophobic parts of the unfolded and misfolded proteins, thus releasing from PERK, IRE1, and ATF6. The disassociation of GRP78 from three membrane transducers enables their activation. In addition, GRP78 can maintain intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis (Li and Lee 2006), assist protein folding, and induce the degradation of related proteins. Moreover, GRP78 inhibits ER stress-induced apoptosis through inhibiting the activity of the apoptotic molecules, such as pro-caspase-4, pro-caspase-7, and Bik (Fu et al. 2007; Jiang et al. 2007; Reddy et al. 2003). Additionally, evidence from studies conducted by our and other groups has found that GRP78 is abnormally expressed in various tumor cells, and its upregulated expression is correlated with the sensitivity of some anti-cancer drugs (Cook et al. 2013; Gifford and Hill 2018; Sun et al. 2011; Zhang et al. 2015). The inhibition of GRP78 expression can increase the sensitivity of cancer cells to anti-cancer drugs, such as microtubule drugs, and resolve the resistance of breast cancer cells to paclitaxel to an extent (Dong et al. 2005; Suzuki et al. 2011; Zhang et al. 2022).

In this study, we showed that lysionotin could significantly inhibit the proliferation of liver cancer Hep3B and HepG2 cells and induce apoptosis. Further investigation showed that lysionotin visibly upregulated the ER stress hallmark GRP78 in liver cancer cells. Given that the high of GRP78 expression in tumor cells can promote tumor growth and may mediate tumor resistance to some anti-tumor drugs, we hypothesize that inhibition of GRP78 may enhance the anti-tumor effect of lysionotin. Herein, we investigated a novel signaling pathways and molecular mechanisms of ER stress in liver cancer cells. We indicated that inhibition of GRP78 combined with lysionotin may be a new strategy for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Materials and methods

Reagents and antibodies

Lysionotin (#3807) was purchased from Nature Standard (Shanghai, China). EGCG (#HY-13653) and AC-DEVD-CHO (#HY-P1001) were purchased from MedChem Express. The following antibodies were used. Grp78 (# 3177), IRE1α (# 3294), eIF2α (# 5324), phospho-eIF2α (# 3398), CHOP (# 2895), cleaved PARP (# 9542), phospho-JNK (# 4668), anti-mouse IgG (# 7076), and anti-rabbit IgG (# 7074) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology. β-actin (# TA-09) was purchased from ZSGB-Bio. The Annexin V-FITC/ PI apoptosis detection kit (#) was purchased from BD Biosciences. Hoechst 33258 was purchased from Solarbio.

Cell culture

HepG2 and Hep3B cells were gained from Procell Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd. The cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 U/mL streptomycin and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Cell viability assay

The cells were treated with or without lysionotin and then subjected to cell growth testing. Cells were added in 12-well plates (7500/well). Cell growth rate was evaluated by calculating the cell number at different time points.

Apoptosis assay

Apoptosis was assayed using flow cytometry with an Annexin V-FITC/PI kit according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, cells were treated with lysionotin for 24 h and then harvested, washed, centrifuged, resuspended, and stained with Annexin V-FITC/PI kit. Then, cells were analyzed by FACS (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

Colony formation assay

Hep3B cells were seeded in 12-well plates at 1500 cells/well. Cells were treated with lysionotin for 24 h, followed by proliferation in the medium without lysionotin for 14 days. Colonies were fixed and stained Giemsa dye liquor. Images were acquired using a light microscope. The number and size of colonies were determined using a NIS-Elements F3.0 imaging system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Immunoblot analysis

The protein lysate prepared using high-efficiency RIPA lysate, PMSF, and protein phosphatase inhibitor in the ratio of 200:5:2 lysed the cells on ice for 30 min and then placed in a 4 °C centrifuge and centrifuged at 12,000g for 10 min. Add 1/4 volume of 4 × loading buffer. The protein sample was heated at 95 °C for 10 min. Protein samples were resolved using SDS-PAGE. The proteins in the PAGE were transferred electrophoretically onto the PVDF membrane. The PVDF membranes were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C or 2 h at room temperature. After washing 3 times, membranes were incubated with appropriate HRP-linked secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Signals were visualized using the chemiluminescence agents.

Transient siRNA transfection

The GRP78-1 siRNA target sequence was 5′-GGAGCGCATTGATACTAGATT-3′. The GRP78-2 siRNA target sequence was 5′CTGGTCAGAGATACTTCTTTT-3′. The negative control siRNA target sequence was 5′-TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGTTT-3′. Cells were transfected with siRNA (Gene Pharma) diluted in Opti-MEM and Lipofectamine 3000. The cells were collected for subsequent experiments at 72-h post-transfection.

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as mean ± SD. To determine the significant difference between values in two groups, one-way analysis of variance and post-hoc multiple comparisons Bonferroni tests were used. Values with P < 0.05 were considered to be significant

Results

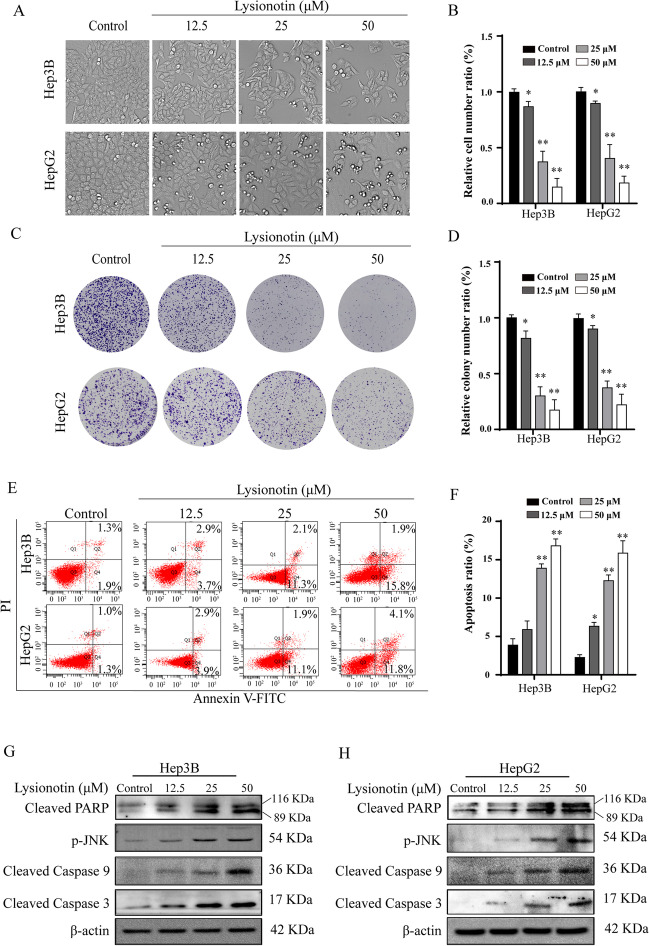

Lysionotin inhibits the growth of liver cancer cells

To detect the cytotoxicity of lysionotin on liver cancer cells, Hep3B and HepG2 cells were treated with different concentrations of lysionotin (12.5, 25, and 50 μM) for 24 h. With the increase in the concentration of lysionotin, the number of shrinking, scrawny, and rounded floating cells increased, and the cell numbers reduced (Fig. 1A). Lysionotin treatment significantly reduced cell proliferation and induced obvious cell death in liver cancer cells (Fig. 1B). Next, we inspected the role of lysionotin on the colony formation potential of liver cancer cells. The results indicated that the number of colonies reduced significantly upon lysionotin treatment in a dose-dependent manner. Meanwhile, the surviving colonies in cells treated with lysionotin tended to be much smaller than those of control cells (Fig. 1C, D). At the same time, we used LO2 as normal liver cells for detection, and found that the growth of LO2 cells was slightly inhibited after lysionotin treatment, and the difference was not statistically significant (Supplementary Fig. 1A, B). Collectively, these results revealed the cytotoxic effects of lysionotin on liver cancer cells.

Fig. 1.

Lysionotin inhibits the growth of liver cancer cells. A and B Representative images of liver cancer cells at 24-h post-treatment with lysionotin were shown. Bar, 100 μm. The cell counting ratio is plotted. Values represent the mean ± SD. n = 3, *p < 0.05, **p <0.01, compared to the control group. C and D The representative images of cell colony and statistical analysis results of numbers of cell colonies are shown. n = 3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, compared to control group. E Representative scatter plots of cell apoptosis are shown. F The apoptosis percentage is plotted. n = 3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, compared to the control group. G and H Western blot analysis performed on lysates to detect the levels of cleaved PARP, p-JNK, and cleaved caspase 3 in HepG2 and Hep3B cells treated with the indicated concentration of lysionotin for 24 h

As widely known, apoptosis is a common type of cell death. To determine whether apoptosis contributes to the lysionotin-induced reduction of cell viability, Annexin V-FITC/PI staining assays were performed. Remarkably, flow cytometric assays showed that the rate of Annexin V-FITC-positive cells increased dose dependently in response to lysionotin treatment in liver cancer cells (Fig. 1E, F). We further examined the level of apoptosis-related proteins by immunoblot analysis. As confirmed, lysionotin treatment significantly induced the expression of activated pro-apoptotic proteins, such as cleaved caspase-3, caspase-9, PARP, and phosphorylated JNK, suggesting that lysionotin-induced apoptosis may be relate to the caspase cascade in both Hep3B and HepG2 cells (Fig. 1G, H). These data show that the liver cancer cells growth retardation induced by lysionotin could be attributed to apoptosis.

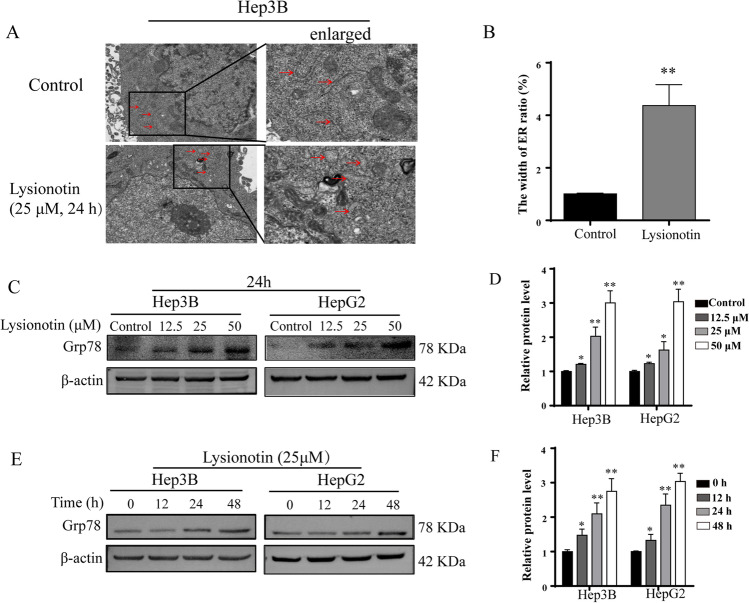

Lysionotin activated ER stress in liver cancer cells

Recently, evidence from studies conducted by our and other research groups has demonstrated that natural bioactive compounds and multiple chemotherapeutic drugs may lead to the disruption of cellular homeostasis, followed by the accumulation of misfolded and unfolded proteins and ER stress. To ensure the involvement of ER stress in lysionotin-treated cells, we performed transmission electron microscopy (TEM) assays to observe the morphology of the ER. TEM analysis demonstrated that lysionotin-treated cells displayed an extensively distended and dilated ER compared with control cells (Fig. 2A, B), suggesting that apoptosis induced by lysionotin may be related to ER stress. To further verify that lysionotin induces ER stress in liver cancer cells, we assayed the expression of GRP78, which is a sentinel marker of ER stress. Western blot analysis showed that, upon lysionotin treatment, the expression of GRP78 increased significantly in a time- and dose-dependent manner in Hep3B and HepG2 cells (Fig. 2C–F).

Fig. 2.

Lysionotin induces the activation of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in liver cancer cells. A and B Hep3B cells were treated with 25 μM lysionotin for 24 h. The cells were then processed for electron microscopy, as described in the Methods. Representative images (scale bars, 1 μM) and statistical analysis results of the width of ER are shown. n = 3, **p < 0.01. C–F Cells were treated with 25 μM lysionotin for the indicated periods or with lysionotin for 24 h at the indicated doses and were then subjected to western blot analysis for Grp78 expression. The results of the quantitative analysis of the levels of Grp78 are shown. The data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, compared to the control group

ROS mediates lysionotin-induced ER stress

ROS represent a class of strongly reactive ions and molecules, which are reported to evoke canonical ER stress. Here, 2', 7'-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) staining was used to detect intracellular ROS production in liver cancer cells. Interestingly, the liver cancer cells treated with lysionotin led to a notable increase in the levels of ROS in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3A, B). In order to detect the ROS burden of individual cells, FACS was used to exam the effect of lysionotin on ROS in HepG2 and Hep3B cells, respectively. The results showed that ROS increased significantly after treatment with lysionotin (Fig. 3C, D).

Fig. 3.

ROS mediates lysionotin-induced ER stress. A and B Superoxide anion staining was used to observe the effect of lysionotin on the level of ROS in Hep3B and HepG2 cells. The data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, compared with the control group. C and D Representative images of changes in ROS levels in Hep3B and HepG2 cells induced by lysionotin detected by flow cytometry. Statistical analysis of flow cytometry test result, n = 4, ***p < 0.001 compared with the control group. E and F Hep3B and HepG2 cells were treated with or without lysionotin and NAC and were then subjected to the western blot analysis of Grp78 expression. The data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). **p < 0.01 compared with the control group. G and H Representative images of liver cancer cells treated with lysionotin and NAC are shown. Bar, 100 μm. The cell counting ratio is plotted. Values represent mean ± SD. n = 3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, compared to the control group

To further inspect whether ROS contributes to lysionotin-induced ER stress, Hep3B cells were treated with or without lysionotin and the ROS scavenger N-229 acetylcysteine (NAC). Remarkably, western blot analysis indicated that NAC pre-treatment partially but significantly abrogated the lysionotin promoted upregulation of GRP78, suggesting that ROS mediates the effects of lysionotin on ER stress. Similar results were observed in HepG2 cells (Fig. 3E, F). Moreover, treatment with 3 μM NAC partly attenuated the decrease in cell viability induced by lysionotin both in Hep3B and HepG2 cells (Fig. 3G, H). Collectively, these results suggest that ROS mediates lysionotin-induced ER stress in liver cancer cells.

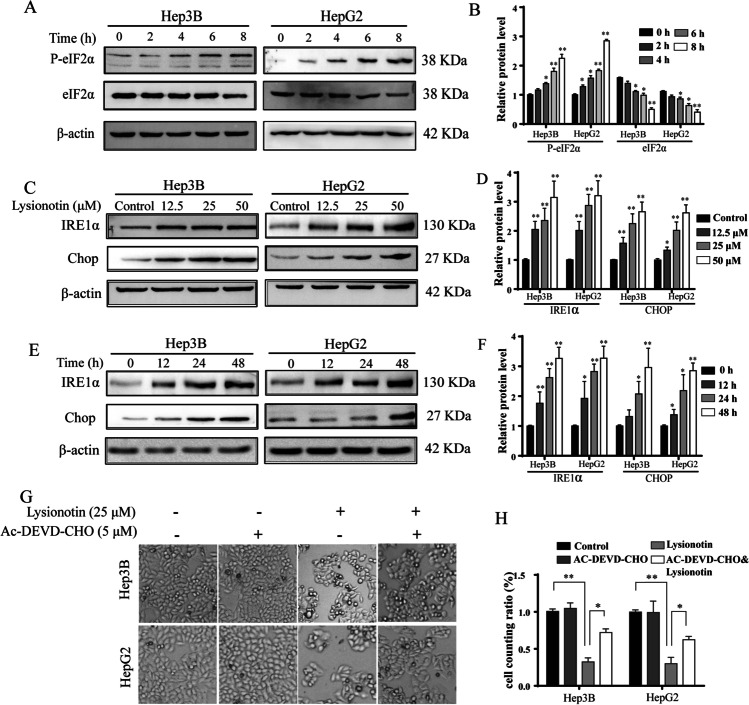

Lysionotin induces the UPR

The UPR is a conserved cellular pathway that regulates protein quality control for the maintenance of cellular environmental homeostasis under ER stress. To further confirm the induction of the UPR in lysionotin-treated cells, we examined the activation status of the effector proteins of UPR (e.g., phosphorylated eIF2α). The data showed that the phosphorylated eIF2α was obviously upregulated in response to lysionotin treatment for 4, 6, and 8 h. Similar effects were detected in HepG2 cells (Fig. 4A, B). Moreover, liver cancer cell treatment with lysionotin showed the induction of IRE and CHOP expression, a hallmark of the UPR, in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4C–F). Thus, lysionotin is identified as an inducer of the UPR.

Fig. 4.

Lysionotin induces the activation of the pro-apoptotic branch of the unfolded protein response (UPR). A and B The protein expression levels of eIF2α and p-eIF2α in Hep3B and HepG2 cells were measured using western blotting. The quantitative analysis of the levels of eIF2α and p-eIF2α are shown. The data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared with the control group. C–F The protein expression levels of IRE1α and CHOP in Hep3B and HepG2 cells were measured by western blotting. The results of the quantitative analysis of the levels of IRE1α and CHOP are shown. The data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared with the control group. G and H Representative images of liver cancer cell treatment with lysionotin and AC-DEVE-CHO are shown. Bar, 100 μm. The cell counting ratio is plotted. Values represent mean ± SD. n = 3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, compared to the control group

In general, the activation of UPR-related proteins, such as phosphorylated eIF2α, cleaved caspase-3, and CHOP, tends to trigger ER stress-induced apoptosis. Particularly, caspase-3 is a member of executioner caspases that involved UPR-induced apoptosis. Given that lysionotin induces caspase-3 cleavage in liver cancer cells (Fig. 1G, H), we hypothesized that the activation of caspase-3 may contribute to lysionotin-induced cell apoptosis and cell viability inhibition. To test this hypothesis, the effect of the caspase-3 inhibitor Ac-DEVD-CHO on lysionotin-induced cell death was examined. As expected, treatment with Ac-DEVD-CHO partially but significantly attenuated lysionotin-induced colony formation by Hep3B and HepG2 cells (Fig. 4G, H). These data suggest that lysionotin-induced cell viability inhibition is linked to the UPR and caspase activation.

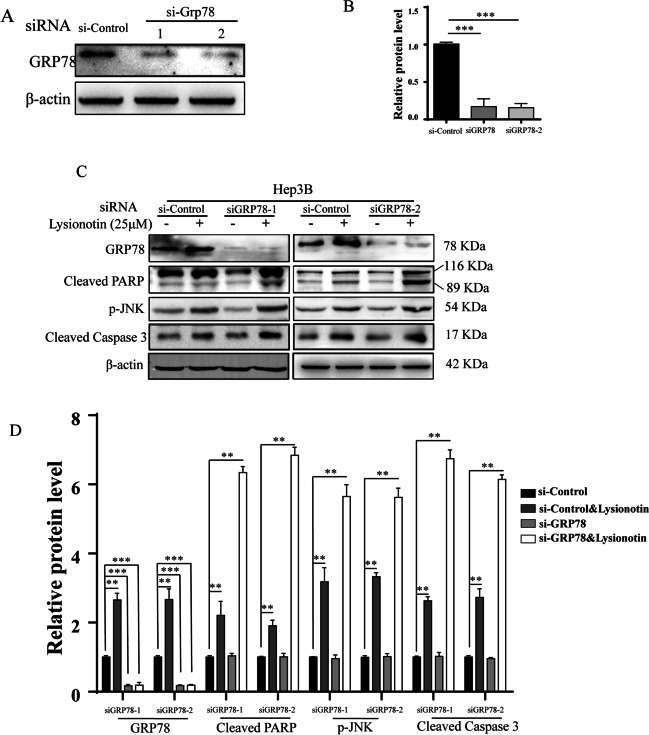

GRP78 knockdown potentiates lysionotin-induced apoptosis

Owing to GRP78 representing a pro-survival arm in the UPR, the downregulation of GRP78 may disrupt the balance between pro-survival and pro-apoptosis signals. To investigate whether GRP78 downregulation potentiates lysionotin-induced activation of caspase-3 and PARP, we detected the effects of GRP78 knockdown via siRNA on the cleavage of caspase-3 and PARP. First, the two designed pairs of GRP78-targeting siRNAs suppressed GRP78 expression efficiently. The expression level of GRP78 in Hep3B cells was reduced to < 20% of the control by si-Grp78-1 and si-Grp78-2 (Fig. 5A, B). Meanwhile, the two GRP78 siRNAs both remarkably downregulated GRP78 expression induced by lysionotin (Fig. 5C, D). More importantly, the two GRP78 siRNAs significantly increased lysionotin-induced caspase-3 and PARP cleavage and JNK phosphorylation (Fig. 5C, D). These results suggest that blockade of GRP78 could potentiate the activation of the caspase cascade induced by lysionotin.

Fig. 5.

GRP78 knockdown potentiates lysionotin-induced apoptosis. A and B Hep3B cells were transfected with the indicated siRNAs and then subjected to western blotting analysis GRP78 expression. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). ***p < 0.001 compared with the control group. C and D Western blot analysis performed on lysates to detect the levels of GRP78, cleaved PARP, p-JNK, and cleaved Caspase 3 in Hep3B cells transfected with the indicated siRNAs. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, compared with the control group

Knockdown of GRP78 expression sensitizes liver cancer cells to lysionotin

To determine whether GRP78 protect liver cancer cells from lysionotin-induced apoptosis, cells were transfected with two pairs of si-Grp78 (si-Grp78 1 and si-Grp78 2) or si-Control and were then treated with or without lysionotin. The colony formation results demonstrated that treatment with both si-Grp78 and lysionotin induced an obvious decrease in the colony number and size, compared to treatment with si-Grp78 (si-Grp78 1 and si-Grp78 2) or lysionotin alone (Fig. 6A, B). Moreover, Hoechst 33342 staining results showed that the inhibition of Grp78 induction inflicted a significant increase in lysionotin-induced apoptosis in Hep3B cells (Fig. 6C, D). The flow cytometric analysis also revealed that the knockdown of Grp78 significantly enhanced lysionotin-induced apoptosis in Hep3B cells (Fig. 6E, F). Together, these results demonstrated that the knockdown of the pro-survival molecule GRP78 expression might lead to the increased sensitivity of liver cancer cells to lysionotin by potentiating the activation of the apoptosis-related branch of the UPR pathway.

Fig. 6.

The knockdown of GRP78 expression sensitizes liver cancer cells to lysionotin. Cells were transfected with the indicated siRNAs and then treated or without lysionotin, which was followed by colony formation experiments, Hoechst staining, and flow cytometry analysis. A and B Representative images of the colonies and statistical analysis results for the number of cell colonies are shown. n = 3. *p < 0.05. C and D Representative images are shown. Hoechst staining indicates the apoptosis of cells. Bar, 20 μM. The apoptosis rate is plotted. n = 3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. E and F Representative scatter plots are shown. The apoptosis percentage is plotted. n = 3, *p < 0.05

EGCG sensitizes liver cancer cells to lysionotin

Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), a flavone-3-olpolyphenol in green tea, exhibits versatile bioactivities, with its anti-cancer effect most attracting due to the cancer preventive effect of green tea consumption, including its manifold anti-cancer actions and mechanisms (Gan et al. 2018; Negri et al. 2018). What we are interested in Grp78 may be one of the targets of EGCG (Schwarze et al. 2008; Wu et al. 2009). Studies have been shown that EGCG could directly interact with the ATP-binding-domain of GRP78 and block its interaction with procaspase-3, thus inhibiting its protective function (Ermakova et al. 2006; Gardner et al. 2013; Jarosch et al. 2003). Although EGCG is not a specific inhibitor of Grp78, we also want to know if the combination of EGCG and lysionotin can synergistically induce cell apoptosis; the role of EGCG and lysionotin alone or in combination on colony formation and apoptosis was examined both in Hep3B and HepG2 cells. Low-dose EGCG (10 μM) alone did not affect the survival of liver cancer cell colonies, but the combination of EGCG and lysionotin significantly decreased the colony numbers compared to lysionotin alone (Fig. 7A, B). In addition, Hoechst 33342 staining analysis showed that the combination of lysionotin and EGCG caused considerably greater apoptosis than lysionotin alone in both cell lines, whereas EGCG alone did not induce apoptosis (Fig. 7C, D). Furthermore, similar results were obtained when we used the Annexin V-FITC/PI assay to detect apoptosis induced by lysionotin and EGCG alone or both in combination (Fig. 7E, F). Then, the normal liver cells LO2 treated by lysionotin with or without EGCG had almost no effect on cell growth (Supplementary Fig. 1C, D). These results indicated that EGCG significantly enhanced lysionotin-induced apoptosis in liver cancer cells.

Fig. 7.

EGCG sensitizes liver cancer cells to lysionotin. Hep3B and HeepG2 cells were treated with or without EGCG and lysionotin and were then subjected to colony formation experiments, Hoechst staining, flow cytometry, and western blot analysis. A and B Representative images of colonies and statistical analysis results of the number of cell colonies are shown. n = 3. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. C and D Representative images are shown. Hoechst staining indicates the apoptosis of cells. Bar, 20 μM. The apoptosis rate is plotted. n = 3, *p < 0.05. E Representative scatter plots are shown. F The apoptosis percentage is plotted. n = 3, * p < 0.05. G and H Western blot analysis performed on lysates to detect the levels of cleaved PARP, p-JNK, and cleaved Caspase 3 in HepG2 and Hep3B cells

More importantly, we examined the effect of EGCG on the lysionotin-induced activation of caspase-3, PARP, and JNK. Consistent with findings from previous research (Gifford and Hill 2018), EGCG does not inhibit expression of Grp78 (Fig. 7G, H). However, EGCG led to a significant increase in the lysionotin-induced activation of pro-caspase-3, PARP, and JNK, although EGCG alone did not activate these proteins (Fig. 7G, H). These results indicated that suppression of GRP78 function by EGCG might cause an increase in the activation of pro-apoptosis signals of the UPR branch under lysionotin induction.

Discussion

GRP78 is a multifunctional chaperone heat shock protein that plays central roles in a variety of physiological inside and outside the ER. Here, our data showed that lysionotin inhibits hepatoma cell growth dependent on ER stress-induced apoptosis in liver cancer cells, including the upregulation of GRP78, IRE, and CHOP expression and eIF-2α phosphorylation. Furthermore, we found that GRP78 is an inducer protein by lysionotin. More importantly, knockdown of GRP78 or GRP78 inhibitor EGCG synergistically promotes lysionotin-induced cell death. This phenomenon could help to understand the mechanisms underlying the anti-cancer effects of lysionotin.

In recent years, a growing body of evidence has shown that that natural products are highly efficient against cancer owing to their structural diversity. In our study group, hydroxysafflor yellow B isolated from the florets of Carthamus tinctorius (Wang et al. 2022), picropodophyllin derived from the rhizome of Dysosma versipellis (Zhu et al. 2022), and Daphnoretin extracted from Wikstroemia indica (Wang et al. 2021) have been shown to successfully inhibit cell growth in gastric, prostate, and melanoma cancer cells. In this study, we first showed that lysionotin is a novel ER stress inducer in liver cancer cells. To further understand the effects of lysionotin on the ER, we observed the morphology of cells treated with or without lysionotin using electron microscopy. The results showed that endoplasm net cavity was markedly swollen. Western blot analyses showed that the expression of GRP78 increased remarkably after the cells were treated with lysionotin, which further confirmed ER stress, similar to the effects observed upon treatment with a Hsp70 inhibitor (Dong et al. 2005), anti-angiogenesis inhibitors (Baumeister et al. 2009; Virrey et al. 2008), histone deacetylase inhibitor (Wang et al. 2009), and microtubule-targeting agents (Ermakova et al. 2006).

In general, ROS production related to flavonoids should be considered in addition to aspects of cell metabolism, cell uptake, and structural diversity in the study of pharmacodynamics (Muller et al. 2021). In our research, we found that lysionotin could also induce intracellular ROS accumulation in Hep3B and HepG2 cells. This is consistent with previous studies, and researchers found that lysionotin induced cell apoptosis via the Caspase-3-mediated mitochondrial pathway by promoting the increase of intracellular ROS levels, but the specific molecular mechanism of ROS production causing cell apoptosis has not been identified (Yang et al. 2021). Some scholars have pointed out that the increase of ROS in cells may be one of the main factors causing ER stress (Zhong et al. 2018). On the contrary, studies have found that persistent ER stress and protein misfolding initiated ROS cascades and their significant roles in the pathogenesis of multiple human disorders, including neurodegenerative diseases, diabetes mellitus, atherosclerosis, inflammation, ischemia, and kidney and liver diseases (Zeeshan et al. 2016). To verify whether ROS is the cause of ER stress activation or the result of ER stress activation, we used active oxygen scavenger NAC and found that pretreatment with NAC remarkably attenuated the lysionotin-induced upregulation of GRP78 and rescued lysionotin-induced cell growth inhibition. This suggests that the accumulation of intracellular ROS induced by lysionotin may be one of the causes of ER stress activation in HCC cells.

The ER, a continuous membrane system, participates in the maintenance of intracellular homeostasis processes via regulating calcium storage, protein synthesis, and lipid metabolism. Upon endogenous and exogenous simulation, multiple signaling cascades will be activated to respond to perturbations in ER homeostasis. However, if the accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins is not resolved, persistent ER stress tends to trigger cell apoptosis. Therefore, induction of apoptosis in cancer cells via inducing prolonged ER stress may be an important strategy in various therapeutic approaches. Growing evidence indicates that natural compounds can mediate their effects by activating the ER stress-mediated apoptosis signal pathway (Martucciello et al. 2020). Here, lysionotin was found to remarkably inhibit the viability of HepG2 and Hep3B cells. In addition, lysionotin-treated cells displayed a significant decrease in colony numbers and an increased Annexin V-positive ratio in a dose dependent manner. These findings clearly suggested that lysionotin induces the apoptosis of liver cancer cells. More importantly, findings from a previous study suggested that lysionotin exerted no significant adverse effects in mice in vivo (Yang et al. 2021). Collectively, these results may help shed light on the exploitation of novel drugs to inhibit liver cancer development, such as lysionotin analogs. Furthermore, lysionotin treatment significantly upregulated the expression of UPR branch proteins, including IRE1α and phosphorylated eIF2α. Interestingly, the protein levels of UPR genes, particularly late signaling molecules, CHOP, phosphorylated JNK, and cleaved PARP, caspase-3, and caspase-7, which is considered to trigger ER stress-induced apoptosis, were remarkably higher in lysionotin-treated cells. Consistent with findings from a previous study (Yang et al. 2021), the caspase-3 inhibitor Ac-DEVD-CHO significantly rescued the pro-apoptosis effects of lysionotin, suggesting the leading role of the caspase cascade in lysionotin-mediated apoptosis. Based on our present data, lysionotin induced liver cancer cell apoptosis, at least partially, related to ER stress-mediated pro-apoptotic signaling.

GRP78, as a hallmark protein of ER stress, is expressed at high levels in various tumors, thus promoting cell proliferation and tumor deterioration (Ermakova et al. 2006; Yin et al. 2017). GRP78 is often associated with drug resistance (Gifford and Hill 2018), and the expression of GRP78 induced by lysionotin may be one of the factors contributing to tumor cell resistance to lysionotin. Indeed, our results clearly indicated that the knockdown of GRP78 synergistically promotes lysionotin-induced apoptosis. Mechanistically, we demonstrated that the abrogation of GRP78 expression resulted in the elevated activation of caspase-3, PARP, and JNK induced by lysionotin. These results clearly suggest that the upregulation of GRP78 induced by lysionotin is not a by-stander but a contributor to lysionotin resistance in liver cancer cells. Hence, when the expression of the pro-survival protein GRP78 is suppressed, the balance between the pro-survival branches and pro-apoptosis arms will shift in favor of cell apoptosis. Therefore, combining lysionotin with GRP78 abrogation may synergistically promote cell death or apoptosis in cancer cells. Although deficiency of GRP78 alone cannot induce apoptosis of cancer cells, GRP78 targeting agent may be considerable in biotherapy or chemotherapy. Therefore, exploration of small molecules that specifically targets GRP78 is justified.

Evidence from numerous studies have indicated that EGCG is the predominantly active polyphenolic compound present in green tea, and it has been studied extensively for its anti-tumor effects, with few adverse effects reported in normal cells (Yu et al. 2007). Moreover, EGCG inhibits growth, metastasis, and angiogenesis and promotes apoptosis by modulating diverse signal transduction pathways in various cancers (Almatroodi et al. 2020). Remarkably, Ermakova et al. revealed that EGCG binds to the ATPase domain of GRP78, thereby acting as a competitive inhibitor to ATP, thus inhibiting the ATPase activity of GRP78 (Ermakova et al. 2006). Given that GRP78 is a key regulator of ER homeostasis, EGCG could inhibit the survival of malignant cells by regulating ER stress and ER stress-induced UPR. Studies conducted by us and others have indicated that EGCG not only exerts a direct effect on cancers via ER stress-related apoptosis but also elevates the sensitivity of cancer cells to therapeutic strategies or drugs (Kang et al. 2019). When combined with other anti-tumor drugs, such as irinotecan, daunorubicin, cisplatin, and doxorubicin, EGCG has been shown to improve the safety of treatment (Li et al. 2015), enhance the inhibitory effect of chemotherapeutic drugs on tumor cell proliferation (Dong et al. 2005), and effectively reverse the tolerance of tumor cells to chemotherapeutic drugs (Zhang et al. 2004).

The downregulation of GRP78 by siRNA or EGCG treatment significantly increased celecoxib-induced apoptosis by enhancing the activation of CHOP, caspase-4, and IRE-1a in urothelial carcinoma cells (Huang et al. 2012). Consistently, the findings of our study indicated that EGCG significantly enhanced lysionotin-induced apoptosis in liver cancer cells by enhancing the lysionotin-induced activation of caspase-3, PARP, and JNK. Moreover, we further showed that lysionotin promotes the expression of GRP78 and that the knockdown of GRP78 by siRNA significantly sensitizes liver cancer cells to lysionotin. These results suggested that the inhibition of GRP78 function may mediate, at least in part, the enhancement of lysionotin sensitivity by EGCG. Of note, we speculate that GRP78 is not the only molecular event that is responsible for the EGCG-induced potentiation of lysionotin-induced apoptosis, because EGCG can target multiple molecules involved in cell survival, such as PARP16 (Wang et al. 2017) and EGFR (Sun et al. 2022). Further investigation would be necessary to determine the potential mechanism by which EGCG improves the anti-cancer effect of lysionotin. Regardless, our results indicate that treatment with a combination of lysionotin and EGCG may be a novel regimen for liver cancer.

Overall, in this present report, we found lysionotin-induced ER stress by initiating ROS production, thus promoting cell apoptosis. But pretreatment with NAC partly attenuated the lysionotin-induced ER stress activation and rescued lysionotin-induced cell apoptosis. This also suggests that there may be other modulation of signaling pathways involved. Previous studies have found that lysionotin induced cancer cell apoptosis through the mitochondrial pathway (Yang et al. 2021) and triggered cancer cell ferroptosis through reduced Nrf2 expression (Gao et al. 2022). Therefore, in order to further enrich the pharmacological effects of lysionotin, further exploration is needed.

As we have known, GRP78 is abnormally high expressed in a variety of tumors and represents a pro-survival arm in the UPR; abrogation of GRP78 induction may be a strategy to sensitize cancer cells to chemotherapeutic drugs (Farshbaf et al. 2020). Indeed, this study clearly demonstrated that downregulation of GRP78 by siRNA or EGCG synergistically promotes lysionotin-induced HCC cells death via ER stress-mediated pro-apoptotic pathway. The current study demonstrates that EGCG could sensitize HCC cells to lysionotin. Notably, EGCG can overcome lysionotin-induced GRP78 expression, which represents another mechanism underlying EGCG suppression of GRP78.

Conclusions

Herein, evidence from this study suggested that the inhibition of cell viability and induction of cell apoptosis in liver cancer cells by lysionotin could be mediated through the elevated intracellular ROS production, subsequently the activation of the pro-apoptotic signaling branch of the UPR. However, lysionotin meanwhile triggers highly expression of GRP78, which promotes cancer cell proliferation and tumor deterioration and often associated with drug resistance. Therefore, liver cancer cells treated with the combination of GRP78-targeting siRNA or EGCG and lysionotin exhibited considerably less survival than cells treated with lysionotin alone. Mechanistically, the inhibition of GRP78 potentiates the activation of pro-apoptotic branch of the UPR, such as cleaved PARP and caspase 3, induced by lysionotin. Overall, these results suggest that the combination of GRP78 inhibitors, such as EGCG, may be a novel approach for improving the effectiveness of lysionotin in liver cancer treatment.

Supplementary information

Supplemental figure. The viability of LO2 cells is not affected by EGCG and lysionotin. (A-B) Representative images of LO2 cells at 24 h post-treatment with lysionotin were shown. Bar, 100 μm. The cell counting ratio is plotted, the difference was not statistically significant. (C-D) Representative images of LO2 cells treated with lysionotin and NAC are shown. Bar, 100 μm. The cell counting ratio is plotted, the difference was not statistically significant.

Acknowledgements

We thank Bullet Edits Limited for the linguistic editing and proofreading of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- GRP78

glucose-regulated protein 78

- ER stress

endoplasmic reticulum stress

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- EGCG

polyphenol (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate

- UPR

unfolded protein response

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

- IRE1

inositol requiring enzyme 1

- PERK

protein kinase R-like ER kinase

- ATF6

activating transcription factor-6

Author contributions

MJ. L., DF. L., YC. Y., Y. Z., HW. S., and HY. L. contributed to experimental design, performed the experiments, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. XX. W, GL. W., YJ. G., and F. Y. performed the experiments and interpreted the data. All the listed authors have read and approved the submitted manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (Grant No. ZR2020MH120 to Li Minjing, Grant N. ZR2020LZL020 to Yin Yancun) and the Introduction and Cultivation Project for Young Creative Talents of Higher Education of Shandong Province (to Yin Yancun, Li Minjing and Wang Guoli).

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The raw data for this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Zou Ying, Shi Hewen, and Lin Haiyan contributed equally to this work and share first authorship.

Contributor Information

Yancun Yin, Email: yinyc1985@126.com.

Defang Li, Email: lidefang@163.com.

Minjing Li, Email: liminjing512@126.com.

References

- Almatroodi SA, Almatroudi A, Khan AA, Alhumaydhi FA, Alsahli MA, Rahmani AH (2020) Potential therapeutic targets of epigallocatechin gallate (egcg), the most abundant catechin in green tea, and its role in the therapy of various types of cancer. Molecules 25(14). 10.3390/molecules25143146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Baumeister P, Dong D, Fu Y, Lee AS. Transcriptional induction of grp78/bip by histone deacetylase inhibitors and resistance to histone deacetylase inhibitor-induced apoptosis. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8(5):1086–1094. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JW, Zhu ZQ, Hu TX, Zhu DY. Structure-activity relationship of natural flavonoids in hydroxyl radical-scavenging effects. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2002;23(7):667–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook KL, Clarke PA, Clarke R. Targeting grp78 and antiestrogen resistance in breast cancer. Future Med Chem. 2013;5(9):1047–1057. doi: 10.4155/fmc.13.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cudna RE, Dickson AJ. Endoplasmic reticulum signaling as a determinant of recombinant protein expression. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2003;81(1):56–65. doi: 10.1002/bit.10445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Bulnes P, Saiz ML, Lopez-Larrea C, Rodriguez RM. Crosstalk between hypoxia and er stress response: a key regulator of macrophage polarization. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2951. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong D, Ko B, Baumeister P, Swenson S, Costa F, Markland F, Stiles C, Patterson JB, Bates SE, Lee AS. Vascular targeting and antiangiogenesis agents induce drug resistance effector grp78 within the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2005;65(13):5785–5791. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermakova SP, Kang BS, Choi BY, Choi HS, Schuster TF, Ma WY, Bode AM, Dong Z. (-)-epigallocatechin gallate overcomes resistance to etoposide-induced cell death by targeting the molecular chaperone glucose-regulated protein 78. Cancer Res. 2006;66(18):9260–9269. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farshbaf M, Khosroushahi AY, Mojarad-Jabali S, Zarebkohan A, Valizadeh H, Walker PR. Cell surface grp78: an emerging imaging marker and therapeutic target for cancer. J Control Release. 2020;328:932–941. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frakes AE, Dillin A. The upr(er): sensor and coordinator of organismal homeostasis. Mol Cell. 2017;66(6):761–771. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Li J, Lee AS. Grp78/bip inhibits endoplasmic reticulum bik and protects human breast cancer cells against estrogen starvation-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2007;67(8):3734–3740. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan RY, Li HB, Sui ZQ, Corke H. Absorption, metabolism, anti-cancer effect and molecular targets of epigallocatechin gallate (egcg): an updated review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2018;58(6):924–941. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2016.1231168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z, Jiang J, Hou L, Ji F. Lysionotin induces ferroptosis to suppress development of colorectal cancer via promoting nrf2 degradation. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022;2022:1366957. doi: 10.1155/2022/1366957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner BM, Pincus D, Gotthardt K, Gallagher CM, Walter P. Endoplasmic reticulum stress sensing in the unfolded protein response. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5(3):a13169. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a013169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford JB, Hill R. Grp78 influences chemoresistance and prognosis in cancer. Curr Drug Targets. 2018;19(6):701–708. doi: 10.2174/1389450118666170615100918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetz C. The unfolded protein response: controlling cell fate decisions under er stress and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13(2):89–102. doi: 10.1038/nrm3270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetz C, Zhang K, Kaufman RJ. Mechanisms, regulation and functions of the unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020;21(8):421–438. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-0250-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang KH, Kuo KL, Chen SC, Weng TI, Chuang YT, Tsai YC, Pu YS, Chiang CK, Liu SH. Down-regulation of glucose-regulated protein (grp) 78 potentiates cytotoxic effect of celecoxib in human urothelial carcinoma cells. Plos One. 2012;7(3):e33615. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarosch E, Lenk U, Sommer T. Endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation. Int Rev Cytol. 2003;223:39–81. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(05)23002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang CC, Chen LH, Gillespie S, Wang YF, Kiejda KA, Zhang XD, Hersey P. Inhibition of mek sensitizes human melanoma cells to endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2007;67(20):9750–9761. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang YX, Chen Y, Yang Y, Chen XX, Zhang DD. Screening five qi-tonifying herbs on m2 phenotype macrophages. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2019;2019:9549315. doi: 10.1155/2019/9549315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Q, Zhang X, Cao N, Chen C, Yi J, Hao L, Ji Y, Liu X, Lu J. Egcg enhances cancer cells sensitivity under (60)cogamma radiation based on mir-34a/sirt1/p53. Food Chem Toxicol. 2019;133:110807. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2019.110807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C, Kim B (2018) Anti-cancer natural products and their bioactive compounds inducing er stress-mediated apoptosis: a review. Nutrients 10(8). 10.3390/nu10081021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kleizen B, Braakman I. Protein folding and quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16(4):343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Lee AS. Stress induction of grp78/bip and its role in cancer. Curr Mol Med. 2006;6(1):45–54. doi: 10.2174/156652406775574523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Wang J, Jing J, Hua H, Luo T, Xu L, Wang R, Liu D, Jiang Y. Synergistic promotion of breast cancer cells death by targeting molecular chaperone grp78 and heat shock protein 70. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13(11-12):4540–4550. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00575.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Guo Y, Tang J, Jiang J, Chen Z. New insights into the roles of chop-induced apoptosis in er stress. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2015;47(2):146–147. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmu128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Jiang M, Chen W, Zhao T, Wei Y. Cancer and er stress: mutual crosstalk between autophagy, oxidative stress and inflammatory response. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;118:109249. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu E, Xu ML, Xia Y, Kong X, Wu Q, Dong T, Tsim K. Activation of g protein-coupled receptor 30 by flavonoids leads to expression of acetylcholinesterase in cultured pc12cells. Chem Biol Interact. 2019;306:147–151. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2019.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martucciello S, Masullo M, Cerulli A, Piacente S (2020) Natural products targeting er stress, and the functional link to mitochondria. Int J Mol Sci 21(6). 10.3390/ijms21061905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Muller L, Schutte L, Bucksteeg D, Alfke J, Uebel T, Esselen M. Topoisomerase poisoning by the flavonoid nevadensin triggers dna damage and apoptosis in human colon carcinoma ht29 cells. Arch Toxicol. 2021;95(12):3787–3802. doi: 10.1007/s00204-021-03162-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negri A, Naponelli V, Rizzi F, Bettuzzi S (2018) Molecular targets of epigallocatechin-gallate (egcg): a special focus on signal transduction and cancer. Nutrients 10(12). 10.3390/nu10121936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Oyadomari S, Mori M. Roles of chop/gadd153 in endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11(4):381–389. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahl HL. Signal transduction from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cell nucleus. Physiol Rev. 1999;79(3):683–701. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.3.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao RV, Hermel E, Castro-Obregon S, Del RG, Ellerby LM, Ellerby HM, Bredesen DE. Coupling endoplasmic reticulum stress to the cell death program. Mechanism of caspase activation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(36):33869–33874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102225200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy RK, Mao C, Baumeister P, Austin RC, Kaufman RJ, Lee AS. Endoplasmic reticulum chaperone protein grp78 protects cells from apoptosis induced by topoisomerase inhibitors: role of atp binding site in suppression of caspase-7 activation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(23):20915–20924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212328200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarze SR, Lin EW, Christian PA, Gayheart DT, Kyprianou N. Intracellular death platform steps-in: targeting prostate tumors via endoplasmic reticulum (er) apoptosis. Prostate. 2008;68(15):1615–1623. doi: 10.1002/pros.20828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senft D, Ronai ZA. Upr, autophagy, and mitochondria crosstalk underlies the er stress response. Trends Biochem Sci. 2015;40(3):141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Huo X, Luo T, Li M, Yin Y, Jiang Y. The anticancer flavonoid chrysin induces the unfolded protein response in hepatoma cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15(11):2389–2398. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun XL, Xiang ZM, Xie YR, Zhang N, Wang LX, Wu YL, Zhang DY, Wang XJ, Sheng J, Zi CT. Dimeric-(-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits the proliferation of lung cancer cells by inhibiting the egfr signaling pathway. Chem Biol Interact. 2022;365:110084. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2022.110084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Lu J, Hu G, Kita K, Suzuki N. Retrovirus-mediated transduction of a short hairpin rna gene for grp78 fails to downregulate grp78 expression but leads to cisplatin sensitization in hela cells. Oncol Rep. 2011;25(3):879–885. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng Z, Shi D, Liu H, Shen Z, Zha Y, Li W, Deng X, Wang J. Lysionotin attenuates staphylococcus aureus pathogenicity by inhibiting alpha-toxin expression. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;101(17):6697–6703. doi: 10.1007/s00253-017-8417-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urano F, Bertolotti A, Ron D. Ire1 and efferent signaling from the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 21):3697–3702. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.21.3697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virrey JJ, Dong D, Stiles C, Patterson JB, Pen L, Ni M, Schonthal AH, Chen TC, Hofman FM, Lee AS. Stress chaperone grp78/bip confers chemoresistance to tumor-associated endothelial cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6(8):1268–1275. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Wang S, Liu W, Li M, Zheng Q, Li D (2022) Hydroxysafflor yellow b induces apoptosis via mitochondrial pathway in human gastric cancer cells. J Pharm Pharmacol. 10.1093/jpp/rgac044 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wang H, Hu X, Li M, Pan Z, Li D, Zheng Q. Daphnoretin induces reactive oxygen species-mediated apoptosis in melanoma cells. Oncol Lett. 2021;21(6):453. doi: 10.3892/ol.2021.12714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Yin Y, Hua H, Li M, Luo T, Xu L, Wang R, Liu D, Zhang Y, Jiang Y. Blockade of grp78 sensitizes breast cancer cells to microtubules-interfering agents that induce the unfolded protein response. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13(9B):3888–3897. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Zhu C, Song D, Xia R, Yu W, Dang Y, Fei Y, Yu L, Wu J. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate enhances er stress-induced cancer cell apoptosis by directly targeting parp16 activity. Cell Death Discov. 2017;3:17034. doi: 10.1038/cddiscovery.2017.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu PP, Kuo SC, Huang WW, Yang JS, Lai KC, Chen HJ, Lin KL, Chiu YJ, Huang LJ, Chung JG. (-)-epigallocatechin gallate induced apoptosis in human adrenal cancer nci-h295 cells through caspase-dependent and caspase-independent pathway. Anticancer Res. 2009;29(4):1435–1442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang A, Zhang P, Sun Z, Liu X, Zhang X, Liu X, Wang D, Meng Z. Lysionotin induces apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells via caspase-3 mediated mitochondrial pathway. Chem Biol Interact. 2021;344:109500. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2021.109500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y, Chen C, Chen J, Zhan R, Zhang Q, Xu X, Li D, Li M. Cell surface grp78 facilitates hepatoma cells proliferation and migration by activating igf-ir. Cell Signal. 2017;35:154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu HN, Ma XL, Yang JG, Shi CC, Shen SR, He GQ. Comparison of effects of epigallocatechin-3-gallate on hypoxia injury to human umbilical vein, rf/6a, and ecv304 cells induced by na(2)s(2)o(4) Endothelium. 2007;14(4-5):227–231. doi: 10.1080/10623320701547299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeeshan H, Lee G, Kim H, Chae H. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and associated ros. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(3):327. doi: 10.3390/ijms17030327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang LY, Li PL, Xu A, Zhang XC. Involvement of grp78 in the resistance of ovarian carcinoma cells to paclitaxel. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(8):3517–3522. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.8.3517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang LY, Yu JY, Leng YL, Zhu RR, Liu HX, Wang XY, Yang TT, Guo YN, Tang JL, Zhang XC. Mir-181c sensitizes ovarian cancer cells to paclitaxel by targeting grp78 through the pi3k/akt pathway. Cancer Gene Ther. 2022;29(6):770–783. doi: 10.1038/s41417-021-00356-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Wei D, Liu J. In vivo reversal of doxorubicin resistance by (-)-epigallocatechin gallate in a solid human carcinoma xenograft. Cancer Lett. 2004;208(2):179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong H, Song R, Pang Q, Liu Y, Zhuang J, Chen Y, Hu J, Hu J, Liu Y, Liu Z, Tang J. Propofol inhibits parthanatos via ros-er-calcium-mitochondria signal pathway in vivo and vitro. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9(10):932. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0996-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Chen X, Wang G, Lei D, Chen X, Lin K, Li M, Lin H, Li D, Zheng Q. Picropodophyllin inhibits the proliferation of human prostate cancer du145 and lncap cells via ros production and pi3k/akt pathway inhibition. Biol Pharm Bull. 2022;45(8):1027–1035. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b21-01006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental figure. The viability of LO2 cells is not affected by EGCG and lysionotin. (A-B) Representative images of LO2 cells at 24 h post-treatment with lysionotin were shown. Bar, 100 μm. The cell counting ratio is plotted, the difference was not statistically significant. (C-D) Representative images of LO2 cells treated with lysionotin and NAC are shown. Bar, 100 μm. The cell counting ratio is plotted, the difference was not statistically significant.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The raw data for this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.