Abstract

In this study, an ultrasonic-assisted alkaline method was used to remove proteins from wastewater generated during oil-body extraction, and the effects of different ultrasonic power settings (0, 150, 300, and 450 W) on protein recovery were investigated. The recoveries of the ultrasonically treated samples were higher than those of the samples without ultrasonic treatment, and the protein recoveries increased with increasing power, with a protein recovery of 50.10 % ± 0.19 % when the ultrasonic power was 450 W. Amino acid analysis showed that the amino acids comprising the recovered samples were consistent, regardless of the ultrasonic power used, but significant differences in the contents of amino acids were observed. No significant changes were observed in the protein electrophoretic profile using dodecyl polyacrylamide gel, indicating that sonication did not change the primary structures of the recovered samples. Fourier transform infrared and fluorescence spectroscopy revealed that the molecular structures of the samples changed after sonication, and the fluorescence intensity increased gradually with increasing sonication power. The contents of α-helices and random coils obtained at an ultrasonic power of 450 W decreased to 13.44 % and 14.31 %, respectively, whereas the β-sheet content generally increased. The denaturation temperatures of the proteins were determined using differential scanning calorimetry, and ultrasound treatment reduced the denaturation temperatures of the samples, which was associated with the structural and conformational changes caused by their chemical bonding. The solubility of the recovered protein increased with increasing ultrasound power, and a high solubility was essential in good emulsification. The emulsification of the samples was improved well. In conclusion, ultrasound treatment changed the structure and thus improved the functional properties of the protein.

Keywords: Wastewater, Protein, Ultrasound-assisted alkali method, Structural property, Functional property

1. Introduction

Soybean, which is a critical oilseed crop that provides edible vegetable oil and protein, is used as a functional nutritional component for humans. Soybean seeds store triacylglycerol in the form of spherical droplets denoted oil bodies (OBs). The outer membrane of an OB comprises a monolayer of phospholipids and membrane proteins. Recently, OBs attracted considerable attention. As a natural oil-in-water emulsion [1], the special structure provides a unique stability that renders it outstanding for use in the fields of food, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals [2]. OB extraction from the slurry obtained by grinding and filtering soybeans requires the addition of large amounts of sucrose and alkali. After centrifugation, the slurry is divided into three layers: the upper OB layer, the middle layer containing soluble protein in a clear liquid, and the lower precipitated solid layer. After collecting the OBs, the middle and lower layers are discarded as waste. However, the middle layer contains numerous carbohydrates, proteins, and inorganic and organic salts, often with high chemical and biological oxygen demands, which, if discharged directly into the environment, may contaminate water bodies, thereby negatively affecting aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems [3]. Therefore, this study was conducted using the discarded intermediate layer, as few studies regarding the crucial proper treatment of this wastewater are reported. The current increase in the global population and shift in individual dietary habits towards protein-rich foods are increasing concerns regarding protein shortages [4]. Therefore, this study extracts protein from wastewater to address the negative environmental impact of excess nutrients in the wastewater and recover protein resources from the generated wastewater.

Alkali extraction-isoelectric point and micellar precipitation and salt extraction-dialysis are three common methods of extracting plant proteins [5]. Alkali extraction-isoelectric point precipitation, which is the most commonly used method, is employed to extract purified protein products from various plants in high yields [6]. However, the extraction pH used in alkali extraction-isoelectric point precipitation may affect protein functionality: a higher alkalinity may increase protein denaturation and aggregation [7], which may adversely affect protein solubility and induce the oxidation of polyphenols to quinones, resulting in extracted proteins with darker colors [8]. Due to the structural binding of proteins to other biomolecules, such as polyphenols and cellulose, conventional alkali extraction-isoelectric point precipitation exhibits limitations. To address this challenge, pretreatment methods, including various enzymatic and physical techniques, are used to maximize structural disruption and improve protein extraction [9]. Due to the low installation and maintenance costs of ultrasound, ultrasonic pretreatment in combination with the alkaline method was used in this study to recover proteins from the wastewater generated by OB extraction.

Ultrasound-assisted extraction methods are employed to extract proteins rapidly and efficiently from materials, using ultrasound to rupture cells. Ultrasound is classified as low (20–100 kHz), medium (100 kHz–1 MHz), or high frequency (1–10 MHz). The ultrasound-induced nucleation, growth, and collapse of microbubbles are known as acoustic cavitation. At a sufficiently high intensity and power, the negative pressure of the rarefaction cycle may exceed the threshold intermolecular force of attraction of the liquid medium, resulting in the formation of cavitation bubbles. The bubbles grow via the rectified diffusion of dissolved gas and solvent molecules, and over numerous cycles, the bubbles gradually grow until they reach critical sizes. When unable to withstand the internal vapor pressure, these bubbles burst violently, releasing a considerable amount of energy [10]. In liquid media, ultrasound propagates various types of physical forces, such as acoustic flow, cavitation, shear, microjets, and shockwaves. These contribute to the rupturing of cell walls and enhance mass transfer between protein molecules and the solvent, thus improving the efficiency of protein extraction [11]. Ultrasonic power is related to the pressure amplitudes of ultrasound waves and provides the threshold for cavitation. Different ultrasonic powers display different effects on the number and sizes of cavitation bubbles, maximum bubble collapse temperature, and ultrasonic chemical yield. Increasing the ultrasonic power may yield an optimal level of cavitation, beyond which marginal effects or reduced performance are observed. Therefore, determining the optimal power for a given application and experimental condition is a key step in the study [10].

Recently, this method improved the yields of various plant proteins. Chittapalo and Noomhorm [12] reported that sonication combined with the alkali method in extracting rice bran protein resulted in a 1.65-fold higher yield than that obtained via the conventional alkali method. The protein yield of ultrasonically treated watermelon seeds increased by 87 % compared to that obtained using conventional methods [13]. Wang et al. [14] reported that ultrasonication-assisted alkali extraction with a shorter extraction time afforded a higher yield of pea proteins (82.6 %) with enhanced functionalities compared to those of the proteins obtained via conventional alkali extraction. The propagation of ultrasound waves in the extraction medium results in acoustic cavitation, which promotes protein extraction by increasing the mass transfer and internal diffusion of the matrix [15].

This study used a combination of ultrasonic treatment and alkali extraction to remove proteins from the effluent produced during OB extraction. Alkali extraction was performed at pH 9 to investigate the effects of different ultrasound powers (0, 150, 300, and 450 W) on the recovery and basic composition of the protein recovered from wastewater to yield insight into the changes in protein structure and function. The process aids in protecting the environment and ensuring the sustainability of food systems, and the recovered proteins may be used to develop renewable protein resources for use in protein applications.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Materials

Soybeans (Dong-Nong 42), which contained 41.2 % crude protein, 23.6 % oil, 11.7 % moisture, and 4.1 % ash, were harvested in Harbin, China [16], and soybean oil was purchased from local supermarkets (Harbin, China). All reagents used were of analytical grade.

2.2. Extraction

The washed soybeans were placed in water in a ratio of 1:5 (w/v), and the solution was stored in a refrigerator at 4 °C for 18 h. Deionized (DI) water was added to the soaked soybeans (1:8, w/v), which were then ground using a tissue crusher at maximum speed for 90 s to yield a slurry. The obtained slurry was filtered through four layers of coarse cotton cloth to remove solid residues, and sucrose (20 %) was then added to the filtrate. The pH was adjusted to 9 (NaOH), followed by 1 h of stirring in an ice-water bath to dissolve the proteins. The filtrate was then centrifuged at 15 000 × g for 30 min (L535R-1, Changsha Xiangyi Centrifuge Instrument, Changsha, China) and transferred to partition funnels to separate the semisolid cream layers from the waste solutions, which were collected. The collected wastewater was treated using an ultrasonic processor (Scientz, Ningbo, China) at 20 kHz for 10 min with an output of 0, 150, 300, or 450 W (0 W: protein samples were recovered using conventional alkali extraction, without ultrasonic treatment, by directly adding HCl to the collected wastewater for precipitation). The wastewater was sonicated by applying a 4 s pulse, with two consecutive cycles separated by a 2 s rest period. After sonication, the pH of the wastewater was adjusted to 4.5 using HCl (1 M), and the wastewater was allowed to stand for 2 h and then centrifuged (15 000 × g, 30 min, 4 °C). The precipitate was collected and redissolved in DI water (1:5, w/v) via stirring for 1 h, and centrifugation was repeated a total of thrice (washing steps). Finally, the precipitates were solubilized in DI water, neutralized with 2 M NaOH, and centrifuged again (15 000 × g, 30 min, 4 °C). The supernatant was lyophilized to afford the resulting protein, which was denoted 0, 150, 300, or 450 W based on the employed output power of 0, 150, 300, or 450 W, respectively.

2.3. Basic composition

2.3.1. Chemical composition

The crude protein contents recovered using the ultrasound-assisted alkaline method with different ultrasonic power settings were determined via the Dumas method (N × 6.25). Petroleum ether was used as the extraction solvent, the oil contents were determined using Soxhlet extraction, and the extracted proteins were determined via the method proposed by Jiang et al. [17]. The protein contents and masses after lyophilization of the samples recovered via the ultrasonic-assisted alkali method with different power settings were recorded and denoted Cr and Wr, respectively. The volume and protein content of the wastewater generated by OB extraction were recorded as Ve and Ce, respectively.

| (1) |

2.3.2. Amino acid analysis

Samples were placed in sealed test tubes containing 6 mol/L HCl, hydrolyzed for 24 h at 110 °C, and then cooled to 20 ± 2 °C, as reported by Zheng et al. [18]. The sample was transferred to a 25 mL volumetric flask and filtered. A 1 mL aliquot of the treated sample solution was dried under vacuum and redissolved in 1 mL HCl, and 30 μL was introduced into the amino acid analyzer (L-8900, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

2.4. Structural analysis

2.4.1. Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

The samples were used to prepare protein suspensions with concentrations of 2 mg/mL by dissolving them in DI water, adding 2 × protein loading buffer, mixing well, and boiling for 5 min. The gels comprised separating (12 %) and concentrating gels (5 %), and 5 μL of the samples were added to the gels. The potential was set to 80 or 120 mV for the concentrating or separating gel, respectively, and the power was cut after the dye reached the bottom of the gel. The gels were dyed, decolorized for 24 h, and photographed.

2.4.2. Fluorescence spectroscopy

Protein suspensions (0.25 mg/mL) were prepared using the samples recovered via the ultrasound-assisted alkali method with different ultrasonic power settings, and the fluorescence spectra were measured at excitation and emission wavelengths and a potential of 280 and 300–400 nm and 700 mV, respectively.

2.4.3. Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy

The FT-IR spectra of the samples recovered via the ultrasound-assisted alkali method with different ultrasonic power settings were obtained using an FTIR-8400S spectrometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) in the spectral range 4000–400 cm−1.

2.4.4. Free sulfhydryl (–SH) groups

Tris-glycine buffer was prepared using 0.086 mol/L tris, 0.09 mol/L glycine, and 4 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid at pH 8.0. Subsequently, 4 mg of 5,5′-dithiobis (2-nitrobenzoic acid) was added to 1 mL Tris-glycine buffer. Different samples were dissolved in 4.5 mL Tris-glycine buffer, added to 50 μL Ellman reagent and mixed well. Then, the solution was protected from light, and its absorbance was recorded using a UV spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The extinction coefficient was 13 600 M−1 cm−1, which was used to calculate the free SH content.

2.4.5. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

DSC was conducted using a differential scanning calorimeter (Mettler Toledo, Columbus, OH, USA) to determine the thermal properties. First, 5–15 mg of soy protein was placed in a sealed sterile (Al) container and then scanned over 20–140 °C at a ramping rate of 10 °C/min.

2.4.6. Surface tension

Different sample powders were weighed to prepare solutions with concentrations of 1 mg/mL, and the surface tension between the protein solution and air was measured for 300 s at 25 °C using a tensiometer equipped with a charge-coupled-device camera (Theta Lite, Biolin Scientific, Gothenburg, Sweden).

2.5. Microstructural characterization

2.5.1. Particle size and ζ-potential

The particle sizes and ζ-potentials of the samples were measured using a Zetasizer Nano ZS90 analyzer (Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, UK). The samples were diluted to 0.001 % with phosphate-buffered saline, and the refractive indices of the dispersed and continuous phases were set to 1.456 and 1.333, respectively [19].

2.5.2. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The lyophilized sample powder was evenly applied to double-sided carbon tape. A scanning electron microscope (S-3400 N, Hitachi) was used at an operating voltage of 30 kV to study the microstructures of the samples, which were coated with layers of Au prior to observation.

2.6. Functional characteristics

2.6.1. Protein solubility

Different sample powders were weighed and dissolved in DI water to prepare solutions with concentrations of 1 mg/mL and the pH values were set to 3–9. The solutions were then centrifuged (10 000 × g, 30 min, 4 °C), and the protein contents in the supernatants were determined using the bicinchoninic acid protein assay.

| (2) |

2.6.2. Surface hydrophobicity (H0)

Protein samples recovered at different powers were dissolved in DI water at concentrations of 0.01–0.5 mg/mL. The protein solution (4 mL) was mixed with 20 μL ANS solution, and the fluorescence intensity was measured at 370 (excitation) and 465 nm (emission). The curve was plotted with the protein concentration as the horizontal axis and the measured fluorescence intensity as the vertical axis, and the slope of the curve was H0.

2.6.3. Emulsifying properties

8 mL of protein solution (5 mg/mL) was homogenized with 2 mL of soybean oil at 10 000 rpm for 2 min. After emulsion preparation, samples were immediately removed from the bottom of the emulsion, and their absorbances were measured at 500 nm via dilution (dissolve SDS in DI water,0.1 % (w/v)) [20].

| (3) |

| (4) |

where A0 and A30 represent absorbance at 0 and 30 min, respectively. The dilution factor, volume fraction of the oil phase, thickness of the cuvette, and concentration of the protein are represented by N (2 0 0), θ (0.20), L (1 cm), and C (g/mL), respectively. T0 and T30 represent 0 and 30 min.

2.6.4. Foaming properties

The foaming capacity (FC) and stability (FSs) of the protein samples recovered using the ultrasound-assisted alkaline method were measured. Protein suspensions of 1 % (w/v) were homogenized at 15 000 rpm for 2 min. V1 is the volume of the foam after homogenization, and V2 is the volume of the foam after 10 min [15].

| (5) |

| (6) |

2.6.5. Water/oil absorption capacity (WAC/OAC)

DI water/oil (10 mL) and proteins (1 g) recovered at different ultrasonic power settings were mixed in centrifuge tubes and centrifuged (8000 × g, 10 min, 4 °C) after standing for 30 min. The precipitate was obtained and placed at a 45° for 20 min and the WAC/OAC is the number of grams of water/oil per gram of sample.

2.6.6. Rheology

The proteins recovered at different ultrasonic power settings were used to prepare 100 g/L suspensions, and silicone oil, which was necessary to prevent evaporation, was prepared prior to the study. Samples were heated from 25 to 90 °C at a heating rate of 2 °C/min, maintained at 90 °C for 10 min, and cooled to 25 °C. The strain and frequency were fixed at 1 % and 0.1 Hz, respectively.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Each experiment was performed in triplicate under the same conditions, and the experimental results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Multiple comparisons were performed using Duncan's test (P < 0.05), and statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Basic composition

3.1.1. Chemical composition

The protein content of the wastewater generated by OB extraction at pH 9.0 was 1.95 % ± 0.03 %. The protein and oil contents and protein recoveries of the sonicated and untreated samples are shown in Table 1. All protein samples recovered in this study display similar protein contents (approximately 80 %). The oil contents of these samples range from 3.55 % to 3.91 %, which are much lower than those of raw soybeans because most oil in the plant is stored in the OBs as triglycerides. Protein recovery using the conventional alkali extraction method is 42.48 %. The recovery of protein from the ultrasound-treated samples increases markedly (P < 0.05) with ultrasonic power, reaching 50.10 % at 450 W. Notably, the process of protein extraction using ultrasound does not exhibit a single mechanism of action but the cumulative effect of shear, microjets, shockwaves, and the formation of hydroxyl radicals via the collapse of cavitation bubbles. These driving forces contribute to the collapse of the cell walls and enhance mass transfer between the protein molecules and solvent, resulting in increased protein recovery [11]. Therefore, ultrasound-assisted alkaline extraction is a suitable method for realizing high recovery rates of proteins from wastewater.

Table 1.

Compositions of protein samples recovered using the ultrasonic-assisted alkali method with different power settings and the protein recovery rates.

| Sample | Protein (%) | Oil (%) | Protein yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 W | 80.59 ± 0.07a | 3.55 ± 0.52a | 42.48 ± 0.34d |

| 150 W | 78.99 ± 0.10c | 3.91 ± 0.59a | 45.31 ± 0.14c |

| 300 W | 78.49 ± 0.11d | 3.88 ± 0.19a | 47.75 ± 0.08b |

| 450 W | 79.65 ± 0.13b | 3.75 ± 0.20a | 50.10 ± 0.19a |

Different letters in the same column indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

3.1.2. Amino acid analysis

Table 2 shows the amino acid compositions and contents of the proteins recovered from wastewater using the ultrasound-assisted alkaline method with different ultrasonic power settings. Glu and Asp are the predominant amino acids, and Met is the limiting amino acid. The amino acids comprising the recovered protein remain identical, irrespective of the ultrasonic power setting, whereas the amino acid contents vary between the samples. The essential amino acid (EAA) contents of the samples increase in the order 26.09 % (0 W) < 26.45 % (150 W) < 26.72 % 300 W) < 27.08 % (450 W). When the ultrasonic power is increased, the content of Pro decreases, whereas those of the other amino acids gradually increase. Amino acids such as Pro and Arg serve as precursors of Asp and numerous enzymes, whereas Glu serves as a substrate for Arg and Pro. Therefore, changes in Pro are associated with Asp [21]. The contents of hydrophilic and -phobic amino acids increase with increasing ultrasonic power. All four samples contain higher contents of hydrophobic amino acids compared to those of hydrophilic amino acids. The compositions of amino acids correlate closely with the functionalities of proteins [22], and thus, the effect of the ultrasound-assisted alkali method on protein functionality was further investigated.

Table 2.

Amino acid analyses of proteins recovered using the ultrasonic-assisted alkaline method with different power settings.

| Total amino acid | 0 W | 150 W | 300 W | 450 W |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asp | 8.37 ± 0.02a | 9.09 ± 0.13b | 9.11 ± 0.08b | 9.37 ± 0.16a |

| Thr | 2.75 ± 0.04b | 2.93 ± 0.06a | 2.94 ± 0.01a | 2.95 ± 0.12a |

| Ser | 3.77 ± 0.06b | 4.14 ± 0.09a | 4.19 ± 0.07a | 4.22 ± 0.07a |

| Glu | 14.73 ± 0.04c | 17.06 ± 0.05b | 17.14 ± 0.15b | 17.55 ± 0.11a |

| Gly | 3.02 ± 0.07b | 3.41 ± 0.14a | 3.44 ± 0.03a | 3.46 ± 0.13a |

| Ala | 2.95 ± 0.01b | 3.28 ± 0.08a | 3.30 ± 0.10a | 3.33 ± 0.05a |

| Cys | 0.70 ± 0.08b | 0.92 ± 0.11a | 0.84 ± 0.04ab | 0.91 ± 0.08a |

| Val | 3.26 ± 0.02b | 3.37 ± 0.02a | 3.38 ± 0.09a | 3.38 ± 0.06a |

| Met | 0.85 ± 0.04b | 0.96 ± 0.07ab | 1.03 ± 0.14a | 1.04 ± 0.09a |

| Trp | – | – | – | – |

| Ile | 3.30 ± 0.12b | 3.44 ± 0.09ab | 3.47 ± 0.06a | 3.54 ± 0.03a |

| Leu | 5.83 ± 0.07b | 6.06 ± 0.16ab | 6.10 ± 0.08a | 6.20 ± 0.19a |

| Tyr | 2.59 ± 0.05b | 2.79 ± 0.09a | 2.84 ± 0.04a | 2.88 ± 0.01a |

| Phe | 3.88 ± 0.05a | 3.59 ± 0.07b | 3.63 ± 0.12b | 3.67 ± 0.13b |

| Lys | 4.39 ± 0.07a | 4.17 ± 0.04c | 4.22 ± 0.07bc | 4.30 ± 0.05ab |

| His | 1.82 ± 0.03b | 1.93 ± 0.07ab | 1.95 ± 0.12ab | 2.00 ± 0.08a |

| Arg | 5.70 ± 0.08b | 5.69 ± 0.08b | 5.77 ± 0.06ab | 5.87 ± 0.06a |

| Pro EAA Hydrophobic Hydrophilic |

3.38 ± 0.05a 26.09 26.47 9.81 |

3.00 ± 0.15b 26.45 27.12 10.77 |

2.93 ± 0.06b 26.72 27.28 10.81 |

2.99 ± 0.16b 27.08 27.61 10.95 |

Different letters in the same column indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

3.2. Structural analysis

3.2.1. Sds-page

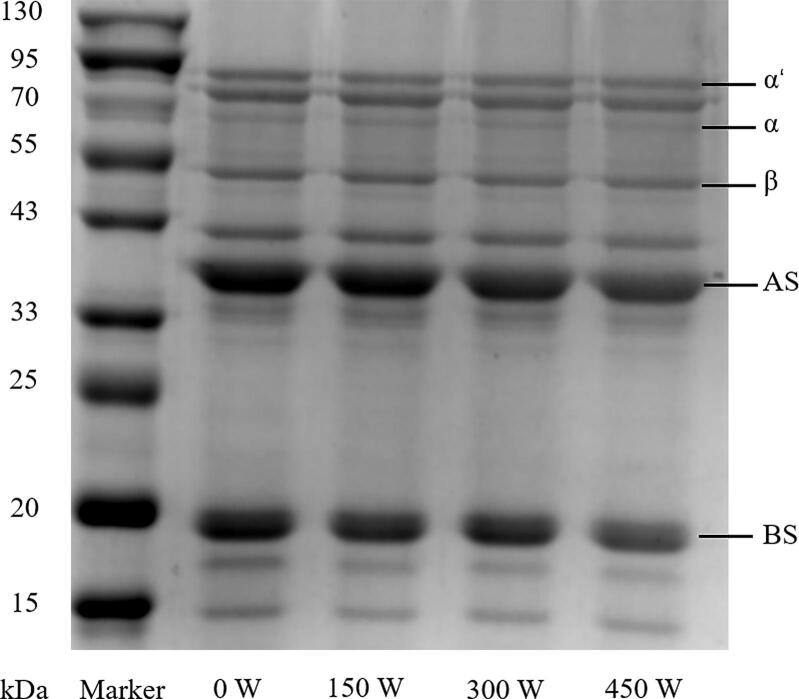

The results of SDS-PAGE of the proteins recovered using the ultrasonic-assisted alkali method with different power settings are shown in Fig. 2. Soy protein contains two major proteins, i.e., 7S and 11S, and their individual subunits are labeled in the figure. As shown in Fig. 2, the ultrasonicated samples exhibit roughly similar bands in the range of approximately 15–95 kDa compared to those of the control, which indicates that the primary structures of the proteins are not altered by sonication. Similar results were reported by Xiong et al. [23], with high-intensity ultrasound used to treat pea protein isolates.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of protein recovery from wastewater.

Fig. 2.

SDS-PAGE profiles of proteins recovered at ultrasonic power of 0, 150, 300, and 450 W.

3.2.2. Fluorescence spectroscopy

As shown in Fig. 3A, the fluorescence intensity increases with increasing ultrasonic power, suggesting that the cavitation forces of ultrasonic treatment unfold the protein structure, leading to an increase in the number of chromophores in the solvent [24]. The maximum emission wavelength (λm) of the initial sample is 328 nm, which increases to 331 nm when the ultrasonic power settings are 150 and 300 W and 330 nm at 450 W. Ultrasonic treatment loosens the protein structure, exposing the internal Trp residues and resulting in the overall redshift of λm [25]. This redshift may be explained by the disruption of the hydrophobic interactions during sonication, which exposes the hydrophobic groups to the molecular surface [26].

Fig. 3.

Fluorescence (A) and Fourier transform infrared spectra (B) of the proteins recovered using the ultrasound-assisted alkali method with different ultrasonic power settings.

3.2.3. FT-IR spectroscopy

Fig. 3B shows the FT-IR spectra of the different protein samples. The FT-IR spectra display three main sets of characteristic transmission bands, among which the amide I band at 1600–1700 cm−1 mainly reflects the stretching vibration of C = O [27]. The secondary structures of the protein components may be analyzed based on the second-order derivatives of the amide I regions. Based on the data shown in Table 3, the respective α-helix and β-sheet and -turn contents are 13.44–15.25 %, 34.53–49.53 %, and 14.36–31.08 %. The content of β-sheets, which are the main secondary structures in the protein samples, is the highest. The α-helix contents of the ultrasonically treated samples are lower than that of the untreated sample. The α-helix content of the untreated sample is 15.25 %, and it is only 13.44 % when treated using an ultrasonic power of 450 W. The content of the random coils exhibits the same trend as that of the α-helices, with the smallest content (14.31 %) observed when an ultrasonic power of 450 W is applied. By contrast, the β-turns content increased to 20.73% at 450 W of ultrasonic power. Therefore, the power setting of ultrasonic treatment changes the secondary structure of the protein to varying degrees [28]. Hydrogen bonding is critical in maintaining the stabilities of the α-helices [29]. Therefore, decreased contents of α-helices and random coils indicate cleavage of the intramolecular hydrogen bonds, a decrease in the disordered protein content, and an increase in protein flexibility, yielding a protein with improved functional properties [29]. Although numerous studies report that ultrasonic treatment changes the secondary structure of a protein [30], [31], these changes should differ according to the protein, modification technology used, and protein components analyzed.

Table 3.

Contents (%) of the secondary structures of the proteins recovered using the ultrasonic-assisted alkali method with different power settings.

| Sample | α-helices | β-sheets | β-turns | Random coils |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 W | 15.25 ± 0.02a | 49.53 ± 0.06a | 14.36 ± 0.03d | 15.89 ± 0.05a |

| 150 W | 13.59 ± 0.07b | 45.76 ± 0.09c | 20.40 ± 0.09c | 14.55 ± 0.14b |

| 300 W | 13.61 ± 0.10b | 34.53 ± 0.02d | 31.08 ± 0.05a | 14.67 ± 0.13b |

| 450 W | 13.44 ± 0.06c | 45.97 ± 0.14b | 20.73 ± 0.13b | 14.31 ± 0.04c |

Different letters in the same column indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

3.2.4. Free –SH groups

As shown in Fig. 4, the free -SH content was measured to further understand the variations in the molecular structures of the proteins. The untreated recovered samples contain 6.05 μmol/g of free –SH. With increasing ultrasonic power, the content of free SH gradually increases and reaches a maximum at 450 W (7.21 μmol/g). This increase is possibly due to the cavitation effect that cleaves the disulfide bonds of the protein, resulting in the formation of sulfhydryl groups [23]. However, the electrophoretic profile showed no change in molecular weight for all samples. Another explanation is that ultrasonic treatment promotes the partial unfolding of the protein, exposing the free –SH groups originally present within the protein molecule [30]. Sun et al. [29] treated OB proteins with ultrasound and the free sulfhydryl contents of the proteins increased with increasing ultrasound power, which is consistent with our experimental results. In contrast, Gulseren et al. [32] reported that sonication reduced the free sulfhydryl contents of the studied proteins. The varied findings suggest that differences in the type of protein used and solution and sonication conditions may lead to different results [33].

Fig. 4.

Free –SH groups of the proteins recovered using the ultrasound-assisted alkaline method with different ultrasonic power settings.

3.2.5. Dsc

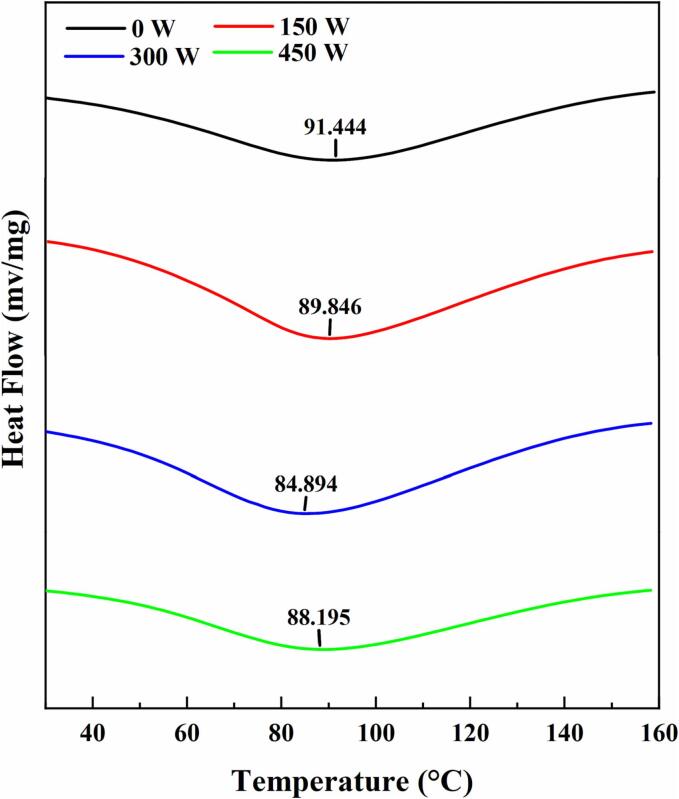

DSC provides insight into the conformational and structural stabilities of the ultrasonically treated recovered proteins [34]. As shown in Fig. 5, the thermograms of all samples exhibit single major heat absorption peaks and different denaturation temperatures. Notably, sonication reduces the denaturation temperatures of the proteins, with denaturation temperatures of 91.444, 89.846, 84.894, and 88.195 °C observed at 0, 150, 300, and 450 W of ultrasonic power, respectively. A decreased denaturation temperature may be related to several structural and conformational changes caused by breakage of the chemical bonds of proteins by ultrasound [35].

Fig. 5.

Differential scanning calorimetry thermograms of the proteins recovered using the ultrasound-assisted alkali method with different ultrasonic power settings.

3.3. Microstructures

3.3.1. Particle size and ζ-potential

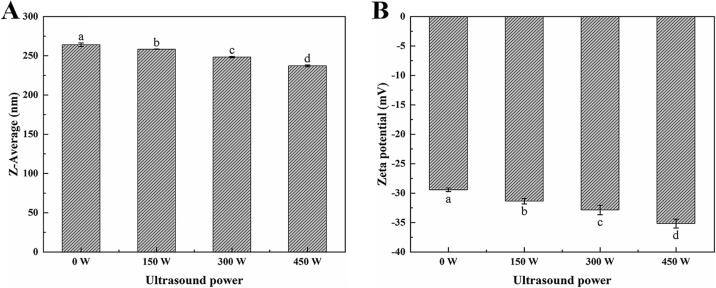

As shown in Fig. 6A, the average particle size of the proteins recovered using the ultrasound-assisted alkali method with different ultrasonic power settings decrease from 264.07 (0 W) to 237.17 nm (450 W) with increasing ultrasonic power. This is likely caused by the cavitation and turbulence effects generated by the ultrasonic probe [36]. Particle size reduction gives the protein a larger surface area, which increases the interactions between the protein and water molecules and leads to increased solubilities. Small particles also increase the surface hydrophobicity because cavitation exposes more groups to a polar environment [35].

Fig. 6.

Particle size (A) and ζ-potential (B) of the proteins recovered using the ultrasound-assisted alkali method with different ultrasonic power settings.

As shown in Fig. 6B, the ζ-potential of all samples is negative, and its absolute value increases with increasing ultrasonic power. This is due to the unfolding of the protein caused by ultrasonic treatment, which results in the exposure of more anionic groups on the surface. The increased exposure of these groups leads to an increased electrostatic repulsive force, which enhances the dispersion of the protein and increases its stability [37].

3.3.2. Sem

As shown in Fig. 7, the image of the untreated recovered protein differs significantly from those of the ultrasonically treated recovered proteins. Compared to those of the untreated protein, the fragments of the ultrasonicated proteins become smaller and more regular with increasing ultrasonic power, which is consistent with the average particle size. This suggests that higher ultrasonic powers may lead to smaller structures and sonication changes the surface structure of the sample, which may affect its function.

Fig. 7.

Surface morphologies of the proteins recovered using the ultrasound-assisted alkali method with different ultrasonic power settings.

3.4. Functional characteristics

3.4.1. Protein solubility

As shown in Fig. 8, the solubilities of the proteins recovered using the ultrasound-assisted alkali method display pH-dependent U-shaped curves. The lowest values (3–7 %) are observed at pH values of 4 and 5, which are related to the isoelectric points of the protein. Protein solubility also increases with increasing ultrasonic power, mainly because of the formation of large cavitation bubbles during sonication, which results in a significant increase in local temperature and pressure. Consequently, protein unfolding and conformational changes occur, leading to an increase in the number of hydrophilic amino acid residues and causing insoluble protein aggregates to become soluble aggregates [38].

Fig. 8.

Solubilities (A) and surface hydrophobicity(B) of the proteins recovered using the ultrasound-assisted alkali method with different ultrasonic power settings.

3.4.2. h0

As shown in Fig. 8, H0 increases with increasing ultrasonic power, which may be attributed to the unfolding of the protein structure and exposure of the internal hydrophobic groups to the polar environment. Several studies report similar conclusions, i.e., ultrasound treatment increases the H0 values of soy [30] and myofibrillar proteins [39]. The increase in H0 may lead to a decrease in the adsorption energy barrier at the air–water interface, thereby enhancing the adsorption kinetics. Consequently, the protein-water interactions increase, resulting in an improved protein FC and FS [35]. Therefore, the foaming properties and FS should be consistent with the H0 data.

3.4.3. Emulsifying properties

The emulsification activity (EAI) of the sonicated samples increase with increasing sonication power (Table 4). The improved solubility and increased net surface charge may increase the protein-solvent interactions [40], and the protein may be adsorbed faster at the oil–water interface. Hence, the emulsification of the protein solution is enhanced [41]. Emulsion stability (ESI) increases from 365.43 (0 W) to 673.44 min (450 W), and thus, ESI is also enhanced by sonication. This may be due to the formation of smaller droplets or changes in the surfaces of the lipid droplets, thus altering the attraction or repulsion between the droplets [33]. Previous studies indicate that the emulsification properties of various proteins, such as pea [42] and walnut proteins [33], may be improved by sonication.

Table 4.

Effects of ultrasonic power on emulsification, foaming, and water/oil-holding capacities.

| Ultrasonic power | EAI (m2/g) | ESI (min) | FC (%) | FS (%) | WAC (g/g) | OAC(g/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 W | 10.05 ± 0.21c | 365.43 ± 46.77c | 69.79 ± 4.77b | 56.67 ± 1.94c | 2.16 ± 0.02d | 4.49 ± 0.01c |

| 150 W | 12.10 ± 0.61b | 424.12 ± 30.07bc | 70.83 ± 3.61b | 67.68 ± 4.63b | 2.87 ± 0.04c | 5.18 ± 0.08b |

| 300 W | 14.27 ± 1.10a | 478.66 ± 24.16b | 79.17 ± 9.55b | 73.69 ± 2.87b | 3.60 ± 0.03b | 5.27 ± 0.01b |

| 450 W | 15.01 ± 0.79a | 673.44 ± 64.94a | 93.75 ± 6.25a | 84.54 ± 2.89a | 3.67 ± 0.01a | 5.39 ± 0.08a |

Different letters in the same column indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

3.4.4. Foaming properties and surface tension

The FC and FS of the proteins recovered via ultrasound-assisted alkaline extraction at the same concentrations are shown in Table 4. The FC of the sonicated protein (450 W) is 1.34-fold higher than that of the untreated protein due to the effect of ultrasonic homogenization [43]. Moreover, the weaker intermolecular interactions between protein molecules may be due to the smaller particle size and higher solubility [30]. The FS increases from 56.67 % (0 W) to 84.54 % (450 W) with increasing ultrasonic power, which depends mainly on the unfolding of the protein structure. The proteins rapidly transfer and adsorb at the air–water interface, forming a thick viscous film around the bubble and generating a stable foam [23].

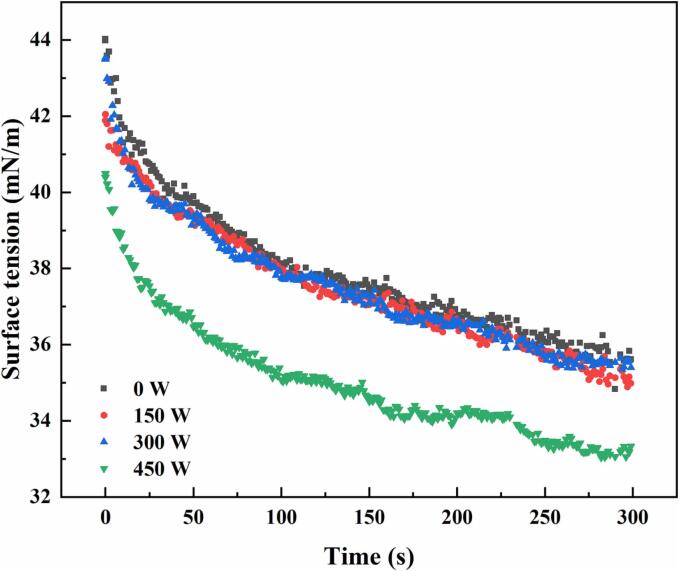

The surface tensions at the air–water interfaces of the proteins recovered using different ultrasonic power settings as functions of time are shown in Fig. 9. The surface tensions of all samples decrease rapidly in the first 50 s and the decrease gradually, indicating that the proteins diffuse rapidly to the interfaces and are adsorbed in the first 50 s, followed by the formation of energy barriers during adsorption and rearrangement. The surface tension of the recovered protein is significantly lower after sonication compared to that of the untreated protein. This may be attributed to the increased flexibility of the protein due to sonication and the large amount of protein adsorbed at the interface. Surface tension exhibits a good negative correlation with FC [40], which further supports the conclusion regarding the foaming properties of the proteins.

Fig. 9.

Surface tensions of the proteins recovered using the ultrasound-assisted alkali method with different ultrasonic power settings.

3.4.5. WAC and OAC

The polar amino groups of proteins are the main sites of water-protein interactions, which affect their water-binding properties. Differences in the purities and conformational characteristics of proteins may lead to variations in WAC [44]. The WAC of the recovered proteins after sonication were higher than that of the untreated protein, slowly increasing with a gradual increase in sonication power and reaching a maximum of 3.67 g/g when the power was 450 W. This may be explained by the increased exposure of polar amino acids due to conformational changes in the protein during extraction [45].

The OAC of proteins is associated with enhanced flavor retention and improved mouthfeel, and the maximum OAC (5.39 g/g) was reached when the sonication power was 450 W. The OAC is associated with the amino acids in proteins, particularly the hydrophobic residues, interacting with the hydrocarbon chains of the lipid molecules [46]. The high OACs of the ultrasonically recovered proteins renders them suitable as ingredients for use in various food products, such as sauces and sausages [47].

3.4.6. Gelation behavior

As shown in Fig. 10, G′ > G′′ for all samples during temperature variation, indicating the dominant elastic behaviors of the protein gels. The initial G′ of the untreated sample exceeds those of the ultrasonically treated samples, while that of the untreated samples showed a decreasing trend during the first 1000 s because of the hydrophobic interactions of the proteins at low temperatures. G′ then begins to display an increasing trend, indicating the initiation of the formation of a gel network [48]. With time, the G′ values of the ultrasonically treated samples significantly exceed that of the untreated sample, suggesting that sonication enhances the strengths of the protein gels. G′ increases significantly with increasing sonication power because the ultrasound broke the noncovalent bond interactions, which facilitated the intermolecular interactions of the proteins, resulting in stronger gels [37]. The increase in G′ observed during the cooling phase is due to the unfolding of the protein structure and exposure of hydrophobic groups during the high-temperature phase. Consequently, enhanced interactions between protein molecules are more conducive to gel formation [49]. Previous studies have reported that the random coil content of gel samples may be related to gel properties, with higher random coil content associated with poorer gel properties[18]. The stronger gels formed after sonication may be associated with random coil content, with a decrease in random coil content of sonicated proteins compared to untreated proteins.

Fig. 10.

Thermal gelation processes of the proteins recovered using the ultrasound-assisted alkali method with different ultrasonic power settings.

4. Conclusions

The ultrasound-assisted alkali method with different ultrasonication power settings was applied to successfully remove and recover proteins from wastewater generated by OB extraction and study the effects of the employed ultrasonication power on protein structure and function. The protein recovery increased with ultrasonic power, and the relative contents of α-helices and random coils of the sonicated samples gradually decreased, whereas those of the β-turns increased. The improvements in functionality of the sonicated samples could be attributed to the unfolding of the protein structure and exposure of the internal hydrophobic groups due to ultrasound treatment. This method reduces the nutrient content of wastewater and enables the effective recovery of proteins with specific properties and functions, which not only benefits the environment, but also aids in maximizing the functional value of soybean processing.

However, this method still exhibits three problems during treatment: 1) a large amount of sucrose is added during OB extraction to enhance collection; 2) the wastewater still contains large amounts of other nutrients; and 3) the pH of the wastewater is alkaline. These limitations require further investigation in future studies. In terms of subsequent research, we may identify methods of processing them into functional beverages or extracting the sugars from the waste stream generated by oil-body extraction to realize a green recycling method. Currently, our studies are still in the laboratory stage, but the insight gained from our research should aid in application in industry as an alternative to existing techniques.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Hanyu Song: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Mingming Zhong: Methodology, Data curation. Yufan Sun: Methodology. Qiang Yue: . Baokun Qi: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge financial support received from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2021YFD2100301-01).

Contributor Information

Qiang Yue, Email: 360559558@qq.com.

Baokun Qi, Email: qibaokun22@163.com.

Data availability

The authors do not have permission to share data.

References

- 1.Sun Y., Zhong M., Wu L., Wang Q.i., Li Y., Qi B. Loading natural emulsions with nutraceuticals by ultrasonication: Formation and digestion properties of curcumin-loaded soybean oil bodies. Food Hydrocoll. 2022;124:107292. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu C., Wang R., He S., Cheng C., Ma Y. The stability and gastro-intestinal digestion of curcumin emulsion stabilized with soybean oil bodies. LWT. 2020;131 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2020.109663. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee S.Y., Stuckey D.C. Separation and biosynthesis of value-added compounds from food-processing wastewater: Towards sustainable wastewater resource recovery. J. Clean. Prod. 2022;357:131975. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Momen S., Alavi F., Aider M. Alkali-mediated treatments for extraction and functional modification of proteins: Critical and application review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021;110:778–797. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2021.02.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanger C., Engel J., Kulozik U. Influence of extraction conditions on the conformational alteration of pea protein extracted from pea flour. Food Hydrocoll. 2020;107:105949. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cui L., Bandillo N., Wang Y., Ohm J.-B., Chen B., Rao J. Functionality and structure of yellow pea protein isolate as affected by cultivars and extraction pH. Food Hydrocoll. 2020;108:106008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao Z., Shen P., Lan Y., Cui L., Ohm J.B., Chen B., Rao J. Effect of alkaline extraction pH on structure properties, solubility, and beany flavor of yellow pea protein isolate. Food Res Int. 2020;131 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hadidi M., Khaksar F.B., Pagan J., Ibarz A. Application of Ultrasound-Ultrafiltration-Assisted alkaline isoelectric precipitation (UUAAIP) technique for producing alfalfa protein isolate for human consumption: Optimization, comparison, physicochemical, and functional properties. Food Res Int. 2020;130 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2019.108907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ampofo J., Ngadi M. Ultrasound-assisted processing: Science, technology and challenges for the plant-based protein industry. Ultrason Sonochem. 2022;84 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.105955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meroni D., Djellabi R., Ashokkumar M., Bianchi C.L., Boffito D.C. Sonoprocessing: From Concepts to Large-Scale Reactors. Chem Rev. 2022;122:3219–3258. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sengar A.S., Thirunavookarasu N., Choudhary P., Naik M., Surekha A., Sunil C.K., Rawson A. Application of power ultrasound for plant protein extraction, modification and allergen reduction – A review. Applied Food Research. 2022;2(2):100219. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chittapalo T., Noomhorm A. Ultrasonic assisted alkali extraction of protein from defatted rice bran and properties of the protein concentrates. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2009;44:1843–1849. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2009.02009.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gadalkar S.M., Rathod V.K. Extraction of watermelon seed proteins with enhanced functional properties using ultrasound. Prep Biochem Biotechnol. 2020;50:133–140. doi: 10.1080/10826068.2019.1679173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang R., Li L., Feng W., Wang T. Fabrication of hydrophilic composites by bridging the secondary structures between rice proteins and pea proteins toward enhanced nutritional properties. Food Funct. 2020;11:7446–7455. doi: 10.1039/d0fo01182g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pezeshk S., Rezaei M., Hosseini H., Abdollahi M. Impact of pH-shift processing combined with ultrasonication on structural and functional properties of proteins isolated from rainbow trout by-products. Food Hydrocoll. 2021;118:106768. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu G., Hu M., Du X., Liao Y.i., Yan S., Zhang S., Qi B., Li Y. Correlating structure and emulsification of soybean protein isolate: Synergism between low-pH-shifting treatment and ultrasonication improves emulsifying properties. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2022;646:128963. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang Y., Zhang C., Zhao X., Xu X. Recovery of emulsifying and gelling protein from waste chicken exudate by using a sustainable pH-shifting treatment. Food Chem. 2022;387 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.132886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng L.i., Wang ZhongJiang, Kong Y., Ma ZhaoLei, Wu ChangLing, Regenstein J.M., Teng F., Li Y. Different commercial soy protein isolates and the characteristics of Chiba tofu. Food Hydrocoll. 2021;110:106115. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun Y., Zhang S., Xie F., Zhong M., Jiang L., Qi B., Li Y.J.F.C. Effects of covalent modification with epigallocatechin-3-gallate on oleosin structure and ability to stabilize artificial oil body emulsions. 2021;341 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y., Zhong M., Xie F., Sun Y., Zhang S., Qi B. The effect of pH on the stabilization and digestive characteristics of soybean lipophilic protein oil-in-water emulsions with hypromellose. Food Chem. 2020;309 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mir N.A., Riar C.S., Singh S. Effect of pH and holding time on the characteristics of protein isolates from Chenopodium seeds and study of their amino acid profile and scoring. Food Chem. 2019;272:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.López-Monterrubio D.I., Lobato-Calleros C., Alvarez-Ramirez J., Vernon-Carter E.J. Huauzontle (Chenopodium nuttalliae Saff.) protein: Composition, structure, physicochemical and functional properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2020;108:106043. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiong T., Xiong W., Ge M., Xia J., Li B., Chen Y. Effect of high intensity ultrasound on structure and foaming properties of pea protein isolate. Food Res Int. 2018;109:260–267. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan S., Xu J., Zhang S., Li Y. Effects of flexibility and surface hydrophobicity on emulsifying properties: Ultrasound-treated soybean protein isolate. Lwt. 2021;142:110881. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li J., Wu M., Wang Y., Li K., Du J., Bai Y. Effect of pH-shifting treatment on structural and heat induced gel properties of peanut protein isolate. Food Chem. 2020;325 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.126921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang L., Wang J., Li Y., Wang Z., Liang J., Wang R., Chen Y., Ma W., Qi B., Zhang M. Effects of ultrasound on the structure and physical properties of black bean protein isolates. Food Res. Int. 2014;62:595–601. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2014.04.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhong M., Sun Y., Sun Y., Fang L., Wang Q., Qi B., Li Y. Soy lipophilic protein self-assembled by pH-shift combined with heat treatment: Structure, hydrophobic resveratrol encapsulation, emulsification, and digestion. Food Chem. 2022;394 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.133514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ding Y., Ma H., Wang K.e., Azam S.M.R., Wang Y., Zhou J., Qu W. Ultrasound frequency effect on soybean protein: Acoustic field simulation, extraction rate and structure. Lwt. 2021;145:111320. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun Y., Zhong M., Wu L., Huang Y., Li Y., Qi B. Effects of ultrasound-assisted salt (NaCl) extraction method on the structural and functional properties of Oleosin. Food Chem. 2022;372 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu H., Wu J., Li-Chan E.C.Y., Zhu L., Zhang F., Xu X., Fan G., Wang L., Huang X., Pan S. Effects of ultrasound on structural and physical properties of soy protein isolate (SPI) dispersions. Food Hydrocoll. 2013;30:647–655. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2012.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eze O.F., Chatzifragkou A., Charalampopoulos D. Properties of protein isolates extracted by ultrasonication from soybean residue (okara) Food Chem. 2022;368 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gulseren I., Guzey D., Bruce B.D., Weiss J. Structural and functional changes in ultrasonicated bovine serum albumin solutions. Ultrason Sonochem. 2007;14:173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu Z., Zhu W., Yi J., Liu N., Cao Y., Lu J., Decker E.A., McClements D.J. Effects of sonication on the physicochemical and functional properties of walnut protein isolate. Food Res Int. 2018;106:853–861. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sha L., Xiong Y.L. Comparative structural and emulsifying properties of ultrasound-treated pea (Pisum sativum L.) protein isolate and the legumin and vicilin fractions. Food Res Int. 2022;156 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.111179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mir N.A., Riar C.S., Singh S. Physicochemical, molecular and thermal properties of high-intensity ultrasound (HIUS) treated protein isolates from album (Chenopodium album) seed. Food Hydrocoll. 2019;96:433–441. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2019.05.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amiri A., Sharifian P., Soltanizadeh N. Application of ultrasound treatment for improving the physicochemical, functional and rheological properties of myofibrillar proteins. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;111:139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.12.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bi C.-H., Chi S.-y., Zhou T., Zhang J.-y., Wang X.-Y., Li J., Shi W.-T., Tian B., Huang Z.-G., Liu Y.i. Effect of low-frequency high-intensity ultrasound (HIU) on the physicochemical properties of chickpea protein. Food Res. Int. 2022;159:111474. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.111474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang L., Ding X., Li Y., Ma H. The aggregation, structures and emulsifying properties of soybean protein isolate induced by ultrasound and acid. Food Chem. 2019;279:114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.11.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Z., Regenstein J.M., Zhou P., Yang Y. Effects of high intensity ultrasound modification on physicochemical property and water in myofibrillar protein gel. Ultrason Sonochem. 2017;34:960–967. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chang L., Lan Y., Bandillo N., Ohm J.-B., Chen B., Rao J. Plant proteins from green pea and chickpea: Extraction, fractionation, structural characterization and functional properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2022;123:107165. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cai Y., Huang L., Chen B., Zhao X., Zhao M., Zhao Q., Van der Meeren P. Effect of alkaline pH on the physicochemical properties of insoluble soybean fiber (ISF), formation and stability of ISF-emulsions. Food Hydrocoll. 2021;111:106188. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang F., Zhang Y., Xu L., Ma H. An efficient ultrasound-assisted extraction method of pea protein and its effect on protein functional properties and biological activities. Lwt. 2020;127:109348. [Google Scholar]

- 43.A. Stefanović, J. Jovanović, M. Dojčinović, S. Lević, M. Žuža, V. Nedović, Z.J.J.o.H.E. Knežević-Jugović, Design, Impact of high-intensity ultrasound probe on the functionality of egg white proteins, J. Hyg. Eng. Des. 6 (2014) 215-224.

- 44.López D.N., Ingrassia R., Busti P., Wagner J., Boeris V., Spelzini D. Effects of extraction pH of chia protein isolates on functional properties. Lwt. 2018;97:523–529. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2018.07.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.López D.N., Ingrassia R., Busti P., Bonino J., Delgado J.F., Wagner J., Boeris V., Spelzini D. Structural characterization of protein isolates obtained from chia (Salvia hispanica L.) seeds. Lwt. 2018;90:396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2017.12.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Das D., Mir N.A., Chandla N.K., Singh S. Combined effect of pH treatment and the extraction pH on the physicochemical, functional and rheological characteristics of amaranth (Amaranthus hypochondriacus) seed protein isolates. Food Chem. 2021;353 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu M., Zeng M., Qin F., He Z., Chen J. Physicochemical and functional properties of protein extracts from Torreya grandis seeds. Food Chem. 2017;227:453–460. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.01.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hu H., Fan X., Zhou Z., Xu X., Fan G., Wang L., Huang X., Pan S., Zhu L. Acid-induced gelation behavior of soybean protein isolate with high intensity ultrasonic pre-treatments. Ultrason Sonochem. 2013;20:187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Malik M.A., Saini C.S. Rheological and structural properties of protein isolates extracted from dephenolized sunflower meal: Effect of high intensity ultrasound. Food Hydrocoll. 2018;81:229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2018.02.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors do not have permission to share data.