Abstract

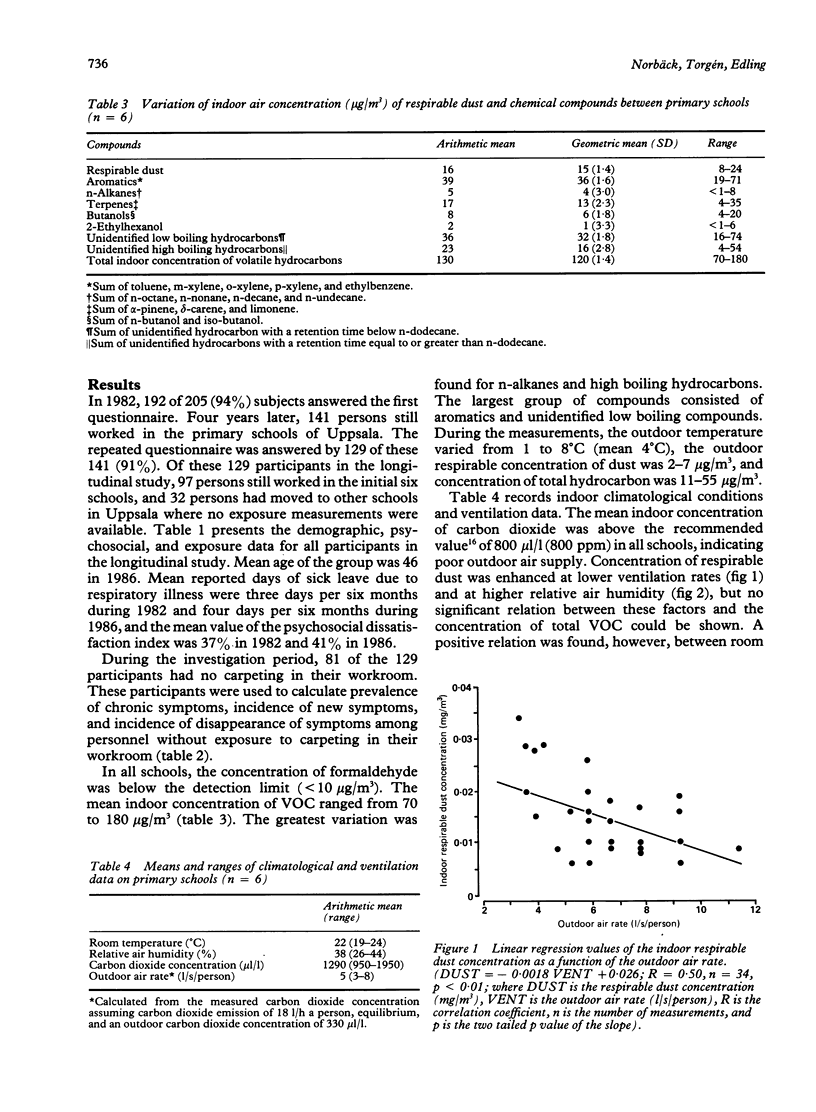

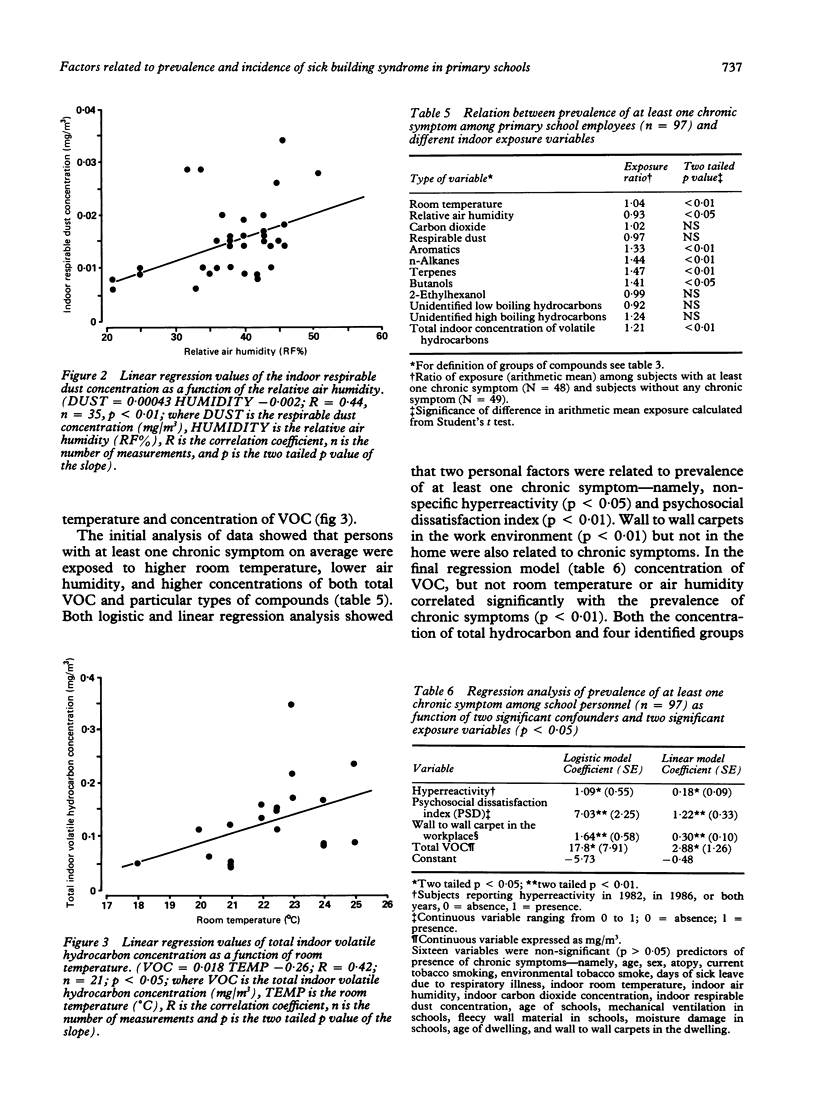

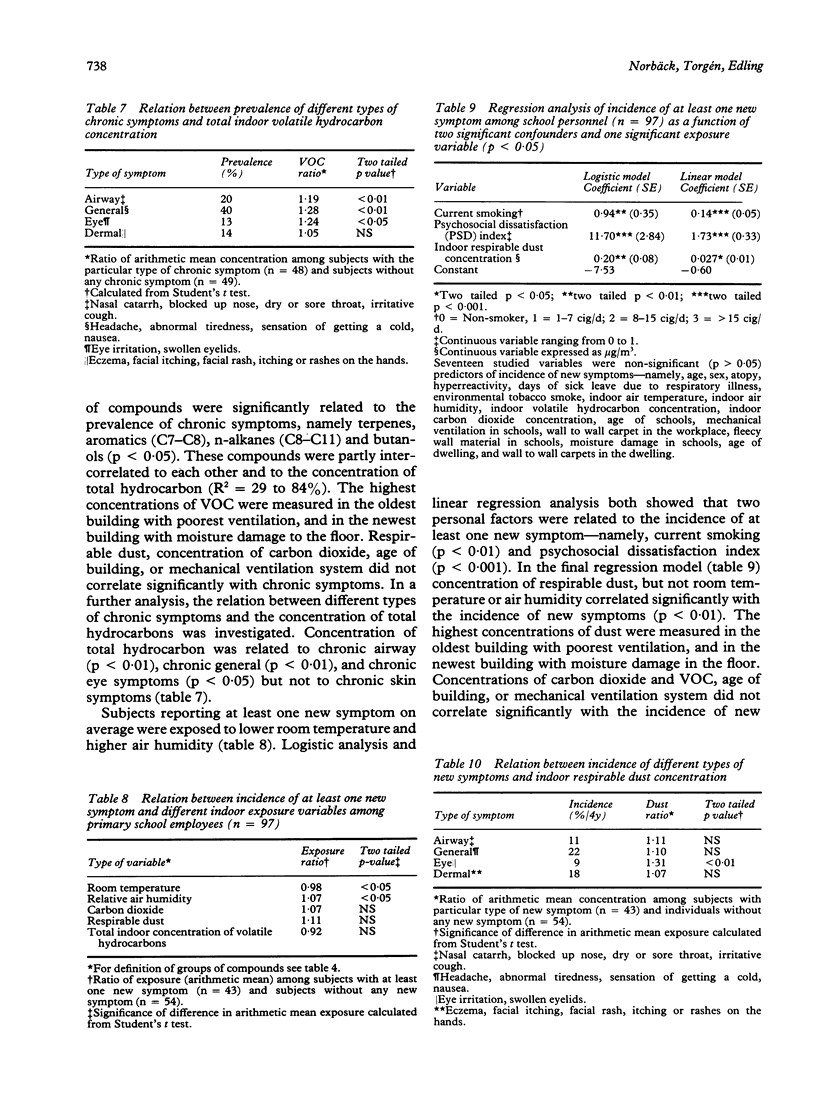

Possible relations between incidence and prevalence of sick building syndrome (SBS), indoor exposures, and personal factors were studied in a four year longitudinal study among personnel (n = 129) in six primary schools. The mean concentration of carbon dioxide was above the recommended value of 0.08 microliter/l (800 ppm) in all schools, indicating a poor outdoor air supply. Indoor concentration of volatile hydrocarbon (VOC) was enhanced at high room temperatures. Respirable dust, but not concentration of VOC was enhanced at lower ventilation rates and high air humidity. Chronic SBS was related to VOC, previous wall to wall carpeting in the schools, hyper-reactivity, and psychosocial factors. Incidence of new SBS was related to concentration of respirable dust, current smoking, and the psychosocial climate. Remission of hyperreactivity, decrease in sick leave owing to airway illness, removal of carpeting in the schools, and moving from new to old dwellings resulted in a decrease in SBS score. It is concluded that SBS is of multifactorial origin, related to a variety of factors and exposures. The total concentration of hydrocarbons is a simple and convenient measure of exposure, which also seems to be a predictor of chronic symptoms. Further investigations on the effect of temperature, ventilation, and air humidity on SBS should consider how these factors may influence the chemical composition of the air. Because poor air quality in schools could also affect the children, it may have implications for the state of health of a large proportion of the population.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aberg N. Asthma and allergic rhinitis in Swedish conscripts. Clin Exp Allergy. 1989 Jan;19(1):59–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1989.tb02345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson K., Hallgren C., Levin J. O., Nilsson C. A. Chemosorption sampling and analysis of formaldehyde in air. Influence on recovery during the simultaneous sampling of formaldehyde, phenol, furfural and furfuryl alcohol. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1981 Dec;7(4):282–289. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.2546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burge S., Hedge A., Wilson S., Bass J. H., Robertson A. Sick building syndrome: a study of 4373 office workers. Ann Occup Hyg. 1987;31(4A):493–504. doi: 10.1093/annhyg/31.4a.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Empey D. W., Laitinen L. A., Jacobs L., Gold W. M., Nadel J. A. Mechanisms of bronchial hyperreactivity in normal subjects after upper respiratory tract infection. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1976 Feb;113(2):131–139. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1976.113.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnegan M. J., Pickering C. A., Burge P. S. The sick building syndrome: prevalence studies. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984 Dec 8;289(6458):1573–1575. doi: 10.1136/bmj.289.6458.1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gravesen S., Larsen L., Gyntelberg F., Skov P. Demonstration of microorganisms and dust in schools and offices. An observational study of non-industrial buildings. Allergy. 1986 Sep;41(7):520–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1986.tb00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenland S. Modeling and variable selection in epidemiologic analysis. Am J Public Health. 1989 Mar;79(3):340–349. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.3.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Main D. M., Hogan T. J. Health effects of low-level exposure to formaldehyde. J Occup Med. 1983 Dec;25(12):896–900. doi: 10.1097/00043764-198312000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel I., Norbäck D., Edling C. An epidemiologic study of the relation between symptoms of fatigue, dental amalgam and other factors. Swed Dent J. 1989;13(1-2):33–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norbäck D., Michel I., Widström J. Indoor air quality and personal factors related to the sick building syndrome. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1990 Apr;16(2):121–128. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen J. H., Døssing M. Formaldehyde induced symptoms in day care centers. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J. 1982 May;43(5):366–370. doi: 10.1080/15298668291409866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pride N. B. Bronchial hyperreactivity in smokers. Eur Respir J. 1988 May;1(5):485–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skov P., Valbjørn O., Pedersen B. V. Influence of personal characteristics, job-related factors and psychosocial factors on the sick building syndrome. Danish Indoor Climate Study Group. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1989 Aug;15(4):286–295. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling E., Sterling T. The impact of different ventilation levels and fluorescent lighting types on building illness: an experimental study. Can J Public Health. 1983 Nov-Dec;74(6):385–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]