Abstract

Background:

The objective was to assess mental health and substance use disorders (MSUD) at delivery hospitalization and readmissions after delivery discharge.

Methods:

This is a population-based retrospective cohort study of persons who had a delivery hospitalization during January to September in the 2019 Nationwide Readmissions Database. We calculated 90-day readmission rates for MSUD and non-MSUD, overall and stratified by MSUD status at delivery. We used multivariable logistic regressions to assess the associations of MSUD type, patient, clinical, and hospital factors at delivery with 90-day MSUD readmissions.

Results:

An estimated 11.8% of the 2,697,605 weighted delivery hospitalizations recorded MSUD diagnoses. The 90-day MSUD and non-MSUD readmission rates were 0.41% and 2.9% among delivery discharges with MSUD diagnoses, compared to 0.047% and 1.9% among delivery discharges without MSUD diagnoses. In multivariable analysis, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, stimulant-related disorders, depressive disorders, trauma- and stressor-related disorders, alcohol-related disorders, miscellaneous mental and behavioral disorders, and other specified substance-related disorders were significantly associated with increased odds of MSUD readmissions. Three or more co-occurring MSUDs (vs one MSUD), Medicare or Medicaid (vs private) as the primary expected payer, lowest (vs highest) quartile of median household income at residence zip code level, decreasing age, and longer length of stay at delivery were significantly associated with increased odds of MSUD readmissions.

Conclusion:

Compared to persons without MSUD at delivery, those with MSUD had higher MSUD and non-MSUD 90-day readmission rates. Strategies to address MSUD readmissions can include improved postpartum MSUD follow-up management, expanded Medicaid postpartum coverage, and addressing social determinants of health.

Keywords: Mental health and substance use disorders, Nationwide Readmissions Database, Postpartum readmission, Hospital discharge data

1. Introduction

Mental health and substance use disorders (MSUD) during pregnancy and postpartum are a public health concern. The proportion of delivery hospitalizations with mental health condition diagnoses such as prenatal depression, anxiety, bipolar disorders, and psychotic disorders has increased significantly in recent years (Haight et al., 2019; Logue et al., 2022; McKee et al., 2020; Weiss et al., 2022). Prevalence of diagnosed perinatal depression ranged from 6.5%–12.9% (Gavin et al., 2005). Prevalence of self-reported depression during pregnancy was 14.8% and prevalence of self-reported postpartum depressive symptoms was 13.4% in 2019 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022). Prevalence of self-reported prenatal anxiety symptoms was 18.2% and prevalence of a clinical diagnosis of any anxiety disorder was 15.2%, with postpartum anxiety prevalence estimated at 9.9% and postpartum anxiety symptoms prevalence estimated at 15.0% (Dennis et al., 2017). Pooled prevalence of bipolar disorder during the perinatal period among women with no previously known psychiatric illness was 2.6% (Masters et al., 2022). About 18.4% of pregnant females aged 15–4 years had past-month use of illicit drugs, tobacco products, or alcohol in 2019 in the United States (US) (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019). The prevalence of maternal opioid-related diagnoses at delivery hospitalization significantly increased from 2010 to 2017 (Hirai et al., 2021). MSUDs are associated with adverse perinatal, neonatal, and child outcomes (Chang, 2020; Forray and Foster, 2015; Sithisarn et al., 2012). Select obstetric risk factors were more common among delivery stays involving at least one mental health disorder than among delivery stays with no mental health disorders (Weiss et al., 2022). Mental health conditions, which include deaths of suicide, overdose/poisoning related to substance use disorder, and other deaths determined to be related to a mental health condition, including substance use disorder are a leading underlying cause of pregnancy-related death in the US, accounting for 22.7% of pregnancy-related deaths from year 2017 to 2019 (Trost et al., 2022). Nearly three-quarters of persons with a pregnancy-related mental health cause of death had a history of depression, and more than two-thirds had past or current substance use (Trost et al., 2021).

Professional and clinical organizations have issued recommendations on screening and management of MSUDs during pregnancy and postpartum, which are known to improve maternal and infant health (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2018; O’Connor et al., 2016). However, there remain unmet needs and barriers to MSUD care during pregnancy and postpartum (Ko and Haight, 2020; Raffi et al., 2021; Webb et al., 2021). Readmissions data can inform interventions to improve discharge planning and follow-up care and reporting such data was included as a bundle element to improve health and well-being of postpartum women (Stuebe et al., 2021). Anticipated care needs can take into account the reasons for readmissions and factors that are associated with readmissions (Girsen et al., 2022). Studies of MSUD readmissions after delivery have focused on all-cause readmissions (Clapp et al., 2016; Kumar et al., 2019; Salemi et al., 2020), specific conditions such as opioid use disorder (Wen et al., 2019), or grouped psychiatric conditions (Wen et al., 2021). However, these studies used International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes for a subset of MSUDs.

Our study assessed MSUDs based on grouped ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes to (1) characterize delivery hospitalizations with and without MSUD diagnoses; (2) assess 90-day MSUD and non-MSUD readmission rates and reasons for readmissions; and (3) estimate how MSUD type, patient, hospital, and clinical factors at delivery were associated with MSUD readmissions.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Data source

This is a population-based retrospective cohort study of MSUDs recorded at delivery hospitalization and readmission within 90 days after delivery discharge using the 2019 National Readmissions Database (NRD). The NRD, compiled and released annually by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), is drawn from HCUP State Inpatient Databases containing verified patient linkage numbers that can be used to track a person across hospitals within a state during a calendar year while adhering to strict privacy guidelines. Thirty HCUP partner states contributed to the 2019 NRD. These states are geographically dispersed and account for 61.8% of the total U.S. resident population and 60.4% of all U.S. hospitalizations. The NRD includes discharges from community hospitals, as defined by the American Hospital Association, and excludes discharges from noncommunity hospitals or community hospitals that are either rehabilitation or long-term acute care hospitals. The NRD contains more than 100 clinical and non-clinical data elements provided in a hospital discharge abstract. HCUP developed discharge weights for national estimates to support national readmissions analysis. More information on discharge level or hospital level exclusions, sampling design, and data elements can be found in the NRD data documentation (HCUP, 2019).

2.2. Measurement of MSUDs, readmissions, and covariates

Index hospitalizations were delivery hospitalizations occurring during January-September 2019 to allow for adequate time to capture 90-day readmissions after delivery discharges in 2019. We chose 90 days to assess patterns of readmission later in the postpartum period. We identified delivery hospitalizations based on a validated algorithm (Clapp et al., 2020).

We identified MSUDs based on Clinical Classifications Software Refined (CCSR) V2021.2 categories in the Mental, Behavioral and Neurodevelopmental Disorders (MBD) chapter. The CCSR aggregates more than 70,000 International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) diagnosis codes into over 530 clinically meaningful categories, organized into 21 body system chapters following the ICD-10-CM diagnosis codebook chapters (HCUP, 2021). The MBD chapter generally follows the organization of the American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders and includes 32 CCSR categories. A total of 21 CCSR categories were included as MSUDs and the rest 11 CCSR categories in the MBD chapter were excluded as MSUDs and included as non-MSUDs (Appendix Table A1). These 11 CCSR categories, including tobacco use, developmental disorders, and remission or subsequent encounter codes, are generally not coded as the principal discharge diagnosis, which were confirmed in our preliminary analysis.

We converted all principal and secondary ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes recorded at the delivery hospitalization to the corresponding CCSR categories. Each MSUD was coded as present at delivery if one or more ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes at delivery belongs to MSUDs. We used the default CCSR category assigned to the principal diagnosis at readmission to determine the principal reason for readmission (HCUP, 2021). If the default CCSR category belonged to MSUD, we coded the readmission as an MSUD readmission. Otherwise, we coded it as a non-MSUD readmission. We based the definition of readmission rate on established HCUP methods (Barrett et al., 2011). We identified the first all-cause/MSUD/non-MSUD readmission within 90 days of index delivery discharge. All-cause readmissions included both MSUD and non-MSUD readmissions. We calculated the 90-day all-cause, MSUD, or non-MSUD readmission rate as the total number of all-cause readmissions, MSUD readmissions, or non-MSUD readmissions within 90 days after delivery, divided by the total number of delivery hospitalization discharges.

We assessed patient and hospital characteristics at delivery hospitalization (Table 1). We used the definitions of these variables provided by HCUP except the following: for primary expected payer, we combined categories other than Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance, or other government insurance into one category, which included missing, no charge, or self-pay (Barrett et al., 2011). For urbanicity of patient residence, we combined large central metropolitan and large fringe metropolitan into large metropolitan area.

Table 1.

Patient, Clinical, and Hospital Characteristics of Delivery Hospitalizations, With or Without Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders (MSUD) Diagnoses, National Readmissions Database, January-September 2019.

| Total |

Delivery Without MSUD Diagnoses |

Delivery With MSUD Diagnoses |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted No. (Col %) | Weighted No. (Col %) | Weighted No. (Col %) | |

| Total | 2,697,605 | 2,380,129 | 317,476 |

| Patient characteristics a | |||

| Age group | |||

| 12–19 | 134,620 (5.0) | 117,176 (4.9) | 17,445 (5.5) |

| 20–29 | 1,288,969 (47.8) | 1,131,773 (47.6) | 157,195 (49.5) |

| 30–39 | 1,184,965 (43.9) | 1,051,952 (44.2) | 133,013 (41.9) |

| 40–55 | 89,051 (3.3) | 79,228 (3.3) | 9823 (3.1) |

| Primary expected payer | |||

| Medicare | 21,775 (0.8) | 15,647 (0.7) | 6128 (1.9) |

| Medicaid | 1,096,603 (40.7) | 939,558 (39.5) | 157,046 (49.5) |

| Private | 1,446,777 (53.6) | 1,306,787 (54.9) | 139,990 (44.1) |

| Other | 81,074 (3.0) | 71,973 (3.0) | 9101 (2.9) |

| Self-pay /no charge/missing | 51,376 (1.9) | 46,164(1.9) | 5212(1.6) |

| Location of patient residence | |||

| Large metropolitan | 1,443,114 (53.5) | 1,283,738 (53.9) | 159,375 (50.2) |

| Medium metropolitan | 617,056 (22.9) | 540,734 (22.7) | 76,322 (24.0) |

| Small metropolitan | 257,413 (9.5) | 223,620 (9.4) | 33,793 (10.6) |

| Micropolitan | 217,406 (8.1) | 189,649 (8.0) | 27,757 (8.7) |

| Not metropolitan or micropolitan | 159,676 (5.9) | 140,356 (5.9) | 19,320 (6.1) |

| Missingb | 2940 (0.1) | 2032 (0.1) | 909 (0.3) |

| Median household income at zip code level | |||

| Quartile 1 (lowest) | 731,892 (27.1) | 641,613 (27.0) | 90,279 (28.4) |

| Quartile 2 | 688,749 (25.5) | 605,243 (25.4) | 83,506 (26.3) |

| Quartile 3 | 695,663 (25.8) | 613,216 (25.8) | 82,447 (26.0) |

| Quartile 4 (highest) | 564,047 (20.9) | 505,023 (21.2) | 59,024 (18.6) |

| Missing | 17,254 (0.6) | 15,034 (0.6) | 2221 (0.7) |

| Clinical characteristics a | |||

| Mode of delivery | |||

| Cesarean section | 856,515 (31.8) | 745,814 (31.3) | 110,701 (34.9) |

| MSUDs | |||

| Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders | 3881 (0.1) | 3881 (1.2) | |

| Depressive disorders | 117,785 (4.4) | 117,785 (37.1) | |

| Bipolar and related disorders | 25,429 (0.9) | 25,429 (8.0) | |

| Anxiety and fear-related disorders | 154,242 (5.7) | 154,242 (48.6) | |

| Trauma- and stressor-related disorders | 16,821 (0.6) | 16,821 (5.3) | |

| Miscellaneous mental and behavioral disorders/conditions | 253,238 (9.4) | 253,238 (79.8) | |

| Alcohol-related disorders | 3827 (0.1) | 3827 (1.2) | |

| Opioid-related disorders | 19,805 (0.7) | 19,805 (6.2) | |

| Cannabis-related disorders | 44,432 (1.6) | 44,432 (14.0) | |

| Stimulant-related disorders | 15,490 (0.6) | 15,490 (4.9) | |

| Other specified substance-related disorders | 77,136 (2.9) | 77,136 (24.3) | |

| Number of non-MSUD comorbidities c | |||

| No Comorbidity | 2,019,390 (74.9) | 1,823,502 (76.6) | 195,888 (61.7) |

| 1 | 535,418 (19.8) | 446,930 (18.8) | 88,488 (27.9) |

| 2 | 117,976 (4.4) | 91,838 (3.9) | 26,138 (8.2) |

| 3 or more | 24,821 (0.9) | 17,859 (0.8) | 6963 (2.2) |

| Length of stay in days (Mean ± SE) | 2.7 (0.01) | 2.6 (0.01) | 3.1 (0.03) |

| Hospital characteristics a | |||

| Hospital bed size | |||

| Small | 482,133 (17.9) | 426,862 (17.9) | 55,272 (17.4) |

| Medium | 743,009 (27.5) | 656,982 (27.6) | 86,027 (27.1) |

| Large | 1,472,463 (54.6) | 1,296,285 (54.5) | 176,178 (55.5) |

| Teaching status of hospital | |||

| Metropolitan non-teaching | 457,468 (17.0) | 410,813 (17.3) | 46,654 (14.7) |

| Metropolitan teaching | 1,993,265 (73.9) | 1,750,992 (73.6) | 242,272 (76.3) |

| Non-metropolitan | 246,873 (9.2) | 218,323 (9.2) | 28,550 (9.0) |

All differences are significant using Chi-squared test except for hospital bed size.

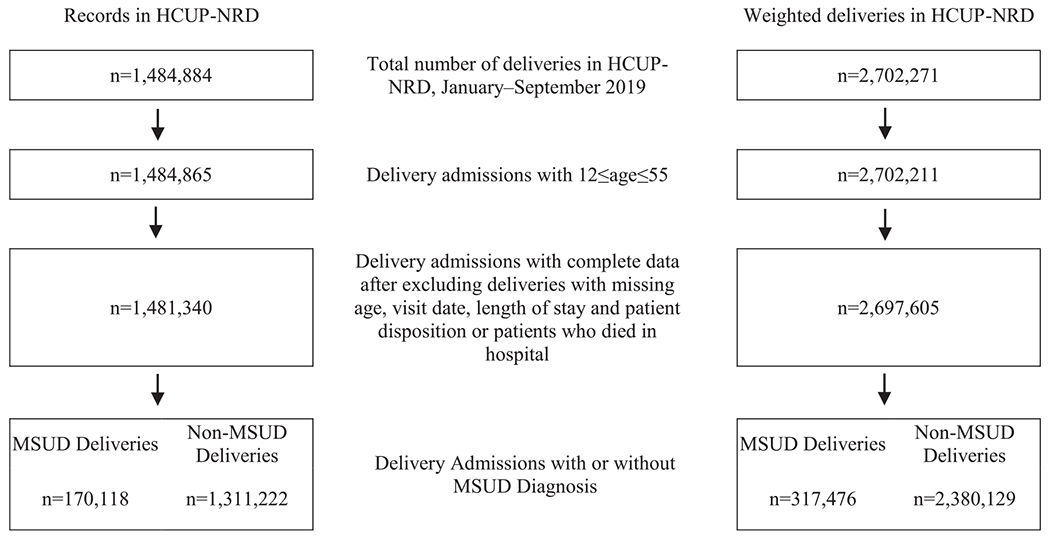

We created missing categories for median household income at zip code level and location of patient residence. Missing primary expected payer is combined with the “self-pay” and “no charge” category. For all other variables, either they do not have missing values or observations with missing values were excluded from the study sample (Fig. 1).

Comorbidities as defined by HCUP Elixhauser comorbidity Software, excluding alcohol abuse, depression, drug abuse, and psychosis.

Clinical characteristics included the delivery mode (cesarean vs vaginal delivery) and the number of non-MSUD comorbidities (none, one, two, three or more) based on Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Elixhauser Comorbidity Software (HCUP, 2022). We excluded Elixhauser comorbidity categories of alcohol abuse, depression, drug abuse, and psychosis because these were included in the definition of MSUDs. In our preliminary analysis, we ran a frequency table of the list of comorbidities and included the top 6 major comorbidities in the multivariate regressions. We also tried including maternal comorbidities of diabetes, hypertension, and obesity. The results were similar. Thus, we included the number of non-MSUD comorbidities for ease of presentation.

We excluded delivery hospitalizations from the analysis if the patient died during the delivery hospitalization or information on patient disposition was missing; age was greater than 55, less than 12 years or missing; or information that was needed to calculate readmission rate (visit date, length of stay) was missing (Fig. 1). Missing information on median household income at zip code level and on location of patient residence was noted as missing, but we included these observations in rate calculations and regressions.

Fig. 1.

Sample inclusion and exclusion criteria among delivery hospitalizations in the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Nationwide Readmissions Database, January-September 2019. HCUP, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, NRD, Nationwide Readmission Database, MSUD, mental health and substance use disorders.

2.3. Statistical analyses

We calculated the 90-day readmission rates after delivery discharge due to all causes, MSUD, and non-MSUD, stratified by MSUD status at delivery. We also tabulated the number of readmissions within 30 days, 31–60 days, and 61–90 days after delivery. We assessed the differences in patient characteristics (age, primary expected payer, location of patient residence, quartile of median household income at the residence zip code), clinical characteristics (delivery mode, number of non-MSUD-related comorbidities, length of stay), and hospital characteristics (bed size, teaching status) of delivery hospitalizations by MSUD status at delivery using Chi-squared test. P< 0.05 is considered statistically significant. To characterize readmission reasons, we calculated the percentages of readmissions that different CCSR body system chapters accounted for, stratified by MSUD status at delivery.

Among delivery hospitalizations with MSUD diagnoses, we used multivariable logistic regressions to assess factors associated with 90-day MSUD readmissions. Factors assessed included the above-mentioned patient, clinical, and hospital characteristics as well as an indicator for each of the 11 specific types of MSUDs that accounted for more than 1% of delivery hospitalizations with MSUD. Since MSUDs types were not mutually exclusive, the estimated odds ratio of a specific MSUD controlled for all other MSUDs present at delivery. In a separate model, we replaced the specific MSUD indicators with the number of MSUDs recorded at delivery (one, two, three or more) and assessed whether having multiple MSUDs diagnoses recorded at delivery was associated with MSUD readmissions. The adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95% Cis were based on survey procedures in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

This study does not require institutional review board review given analyses of deidentified data are considered research not involving human subjects.

3. Results

Of 2,697,605 weighted delivery hospitalizations from January to September 2019 included in our analysis, an estimated 11.8% of delivery hospitalizations recorded one or more MSUDs. Among these delivery hospitalizations recorded with MSUDs, an estimated 8.8% had one MSUD recorded; 61.4% had two; and 29.8% had three or more. The most frequently recorded MSUDs at delivery were miscellaneous mental and behavioral disorders/conditions (9.4%, Table 1), anxiety and fear-related disorders (5.7%), depressive disorders (4.4%), other specified substance-related disorders (2.9%), cannabis-related disorders (1.6%), bipolar and related disorders (0.9%), opioid-related disorders (0.7%), trauma- and stressor-related disorders (0.6%), stimulant-related disorders (0.6%), schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders (0.1%) and alcohol-related disorders (0.1%). Other MSUD categories each accounted for less than 0.1% of deliveries.

Among the most frequently recorded MSUD at delivery, “miscellaneous mental and behavioral disorders/conditions.”, the specific ICD-10-CM codes that collectively accounted for over 90% of “miscellaneous mental and behavioral disorders/conditions” included O99344, O99343, O99345, O99340, O99342, O99341 (other mental disorders complicating pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperium), F53 (Mental and behavioral disorders associated with the puerperium, not elsewhere classified), and F99 (Mental disorder, not otherwise specified). The specific ICD-10-CM codes that collectively accounted for over 90% of “other specified substance related disorders” included O99324 (drug use complicating childbirth), O99323 (drug use complicating pregnancy, third trimester), F1910 (other psychoactive substance abuse, uncomplicated), and F1990 (other psychoactive substance use, unspecified, uncomplicated).

As presented in Table 1, distribution of characteristics among deliveries with or without MSUD diagnoses recorded was statistically different for all examined characteristics except hospital bed size. Compared to delivery hospitalizations with no MSUD recorded, a higher proportion of delivery hospitalizations with MSUDs recorded listed Medicaid as their primary expected payer (49.5% vs 39.5%, P<0.001), residency at locations other than large metropolitan areas (49.8% vs 46.1%, P<0.001), and median household income at zip codes of residence belonging to the lowest quartile (28.4% vs 27.0%, P<0.001). A higher percentage of deliveries with MSUD diagnoses were by cesarean compared to those deliveries without MSUD recorded (34.9% vs 31.3%, P<0.001). Delivery hospitalizations with MSUD recorded on average had longer length of stay (3.1 vs 2.6 days, P<0.001) and younger age at delivery than delivery hospitalizations without MSUD recorded (28.7 vs 29.1, P<0.001).

The top 10 primary CCSR body system chapters based on principal diagnosis recorded on all-cause 90-day readmissions after delivery are in Fig. 2. Pregnancy-related readmissions accounted for 77.4% of readmissions among deliveries without MSUD diagnoses, in comparison to 66.7% among deliveries with MSUD diagnoses. Mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders chapter accounted for 11.5% of readmissions among deliveries with MSUD diagnoses, in comparison to 2.3% among deliveries without MSUD diagnoses. The 90-day all-cause, MSUD, and non-MSUD readmission rates differed by MSUD status at delivery hospitalization (Table 2). Regardless of MSUD status at delivery, the number of non-MSUD readmissions decreased after the first 30 days after delivery discharge. In contrast, the number of MSUD readmissions increased over time after delivery (Table 2). For example, among deliveries with MSUD diagnoses, the number of MSUD readmissions increased from 338 in the first 30 days to 508 in the 61–90 days after delivery discharge. Among deliveries without MSUD diagnoses, the number of MSUD readmissions increased from 218 in the first 30 days to 481 in the 61–90 days after delivery discharge.

Fig. 2.

Percentage distribution of top 10 default Clinical Classifications Software Refined categories for principal diagnosis of readmissions within 90 days after delivery discharge. PRG, pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperium; DIG, diseases of the digestive system; MBD, mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders; INF, certain infectious and parasitic diseases; GEN, diseases of the genitourinary system; CIR, diseases of the circulatory system; INJ, injury, poisoning and certain other consequences of external causes; RSP, diseases of the respiratory system; NVS, diseases of the nervous system; NEO, neoplasms. Detailed ICD diagnoses codes in each category available online in the CCSR user’s guide.

Table 2.

Readmission Rate for Deliveries With or Without Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders (MSUD) Diagnoses, National Readmission Database, January to September 2019.

| Deliveries without MSUD | Deliveries with MSUD | |

|---|---|---|

| Total weighted N(Col %) | 2,380,129 (100) | 317,476 (100) |

| All-cause 90-day readmissions, weighted N | 45,209 | 10,403 |

| All-cause 90-day readmission rate, % (95% CI) a | 1.9 (1.8–2.0) | 3.3 (3.1–3.4) |

| 0–30 day readmission, weighted N(Col %) | 34,764 (1.5) | 7150 (2.3) |

| 31–60 day readmission, weighted N(Col %) | 5975 (0.3) | 1773 (0.6) |

| 61–90 day readmission, weighted N(Col %) | 4469 (0.2) | 1480 (0.5) |

| MSUD 90-day readmissions, weighted N | 1119 | 1295 |

| MSUD 90-day readmission rate, % (95% CI) a | 0.047 (0.042–0.052) | 0.41 (0.37–0.45) |

| 0–30 day readmission, weighted N (Col %) | 218 (0.01) | 338 (0.1) |

| 31–60 day readmission, weighted N(Col %) | 420 (0.02) | 449 (0.1) |

| 61–90 day readmission, weighted N(Col %) | 481 (0.02) | 508 (0.2) |

| Non-MSUD 90-day readmissions, weighted N | 44,180 | 9221 |

| Non-MSUD 90-day readmission rate, % (95% CI) a | 1.9 (1.8–1.9) | 2.9 (2.8–3.0) |

| 0–30 day readmission, weighted N (Col %) | 34,556 (1.5) | 6832 (2.2) |

| 31–60 day readmission, weighted N(Col %) | 5585 (0.2) | 1378 (0.4) |

| 61–90 day readmission, weighted N(Col %) | 4040 (0.2) | 1011 (0.3) |

All differences are significant using Chi squared test. The calculation of readmission rate only includes the first readmission in a given time period, thus the MSUD 90-day readmissions and non-MSUD readmissions do not necessarily sum to the all-cause 90-day readmissions.

In multivariable regression among deliveries with MSUD, MSUD type at delivery were differentially associated with 90-day MSUD readmissions (Table 3). Among the 11 types of MSUDs evaluated, eight MSUDs were associated with significantly higher odds for postpartum MSUD readmissions, with the highest odds for schizophrenia (OR = 7.30, 95%CI: 5.44–9.78), bipolar (OR = 2.27, 95%CI: 1.70–3.02), and stimulant-related disorders (OR =2.15, 95%CI: 1.52–3.05). Other types of MSUDs associated with increased odds of MSUD readmissions included depressive disorders (OR =1.35, 95%CI:1.07 −1.72), trauma- and stressor-related disorders (OR =1.65, 95%CI:1.28 −2.12), miscellaneous mental and behavioral disorders/conditions (OR =1.77, 95% CI:1.24 −2.54), alcohol-related disorders (OR =1.75, 95%CI: 1.04–2.94), and other specified substance-related disorders (OR =1.54, 95%CI:1.08 −2.20). Medicare or Medicaid insurance (vs private insurance) as primary expected payer at delivery and residence in a zip code with the lowest household income quartile (vs the highest income quartile) were significantly associated with higher odds for MSUD readmissions. Odds of MSUD readmission also increased with longer length of delivery hospitalization stay and younger age at delivery. In a separate multivariable regression analysis, where specific MSUD categories were replaced by the number of MSUDs at delivery, three or more MSUDs (vs one MSUD) at delivery was associated with significantly higher odds for MSUD readmissions (OR=3.27, 95% CI:2.10–5.09) (Data not shown).

Table 3.

Factors Associated With 90-day Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders Readmissions Among Hospital Deliveries with MSUD Diagnoses, National Readmissions Database, 2019.a

| Characteristics at delivery hospitalization | aOR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| MSUD type | ||

| Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders | 7.30 (5.44–9.78) | <0.001 |

| Depressive disorders | 1.35 (1.07–1.72) | 0.013 |

| Bipolar and related disorders | 2.27 (1.70–3.02) | <0.001 |

| Anxiety and fear-related disorders | 0.84 (0.68–1.03) | 0.088 |

| Trauma- and stressor-related disorders | 1.65 (1.28–2.12) | <0.001 |

| Miscellaneous mental and behavioral disorders/conditions | 1.77 (1.24–2.54) | 0.002 |

| Alcohol-related disorders | 1.75 (1.04–2.94) | 0.035 |

| Opioid-related disorders | 1.25 (0.84–1.87) | 0.266 |

| Cannabis-related disorders | 0.75 (0.53–1.06) | 0.100 |

| Stimulant-related disorders | 2.15 (1.52–3.05) | <0.001 |

| Other specified substance-related disorders | 1.54 (1.08–2.20) | 0.016 |

| Primary expected payer | ||

| Medicare | 5.04 (3.40–7.48) | <0.001 |

| Medicaid | 2.13 (1.62–2.80) | <0.001 |

| Private | 1.0 (reference) | |

| Other | 1.75 (0.95–3.23) | 0.073 |

| Self-pay/ no charge/ unknown | 1.39 (0.65–2.95) | 0.395 |

| Median household income at zip code level | ||

| Quartile 1 (lowest) | 1.57 (1.12–2.21) | 0.009 |

| Quartile 2 | 1.38 (0.99–1.92) | 0.054 |

| Quartile 3 | 1.15 (0.83–1.61) | 0.400 |

| Quartile 4 (highest) | 1.0 (reference) | |

| Age at delivery in years | 0.96 (0.94–0.97) | <0.001 |

| Length of stay in days | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | 0.014 |

MSUD, Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; Results not reported for other characteristics that are not significant in the regression, including hospital bed size, hospital teaching status, patient location, delivery mode, number of non-MSUD comorbidities, and missing categories for median household income at zip code level. MSUD types are dummy variable indicators, and MSUD types are not mutually exclusive. Odds of readmission for each type of MSUD is controlling for all other types of MSUD.

4. Discussion

Eight MSUDs were associated with significantly higher odds for postpartum MSUD readmissions. This is consistent with previous findings that women with psychiatric diagnoses at delivery hospitalization were more likely to be readmitted for postpartum psychiatric conditions compared with those without psychiatric comorbidity, although that study grouped all psychiatric diagnoses together (Wen et al., 2021). Although screening for depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, trauma and intimate partner violence, and substance use disorders (for example, opioid use disorders and stimulant use disorder) is recommended by professional organizations, implementation of screening and referral to treatment can still benefit from improvement, such as evidence-based, individualized, non-judgmental care and the capacity for integrating screening and intervention for multiple, co-occurring MSUDs (Byatt et al., 2020; Ecker et al., 2019; Gulbransen et al., 2022). Furthermore, we found that severe mental illness such as schizophrenia, bipolar and related disorders, noted at delivery hospitalization was associated with the highest odds for MSUD readmissions, even when controlling for the presence of other MSUDs. Continuity of care post-discharge is especially important for individuals with these conditions (Conejo-Galindo et al., 2022; Jones et al., 2014). We noted a large proportion of MSUDs have indicators for nonspecific miscellaneous mental and behavioral disorders/conditions or other specified substance-related disorders. This may reflect difficulties in confirming a diagnosis or transferring diagnosis to coding for MSUD conditions in the billing infrastructure (Kim et al., 2012; Howell et al.,2021).

As expected, we found a higher rate of MSUD readmissions for delivery hospitalizations with MSUD diagnoses than for those without MSUD diagnoses. The number of MSUD readmissions increased over time after delivery for both groups regardless of whether MSUD was present at delivery, although the MSUD readmissions numbers were small for both groups. This finding may reflect the continued need for screening and referral to treatment for MSUD beyond the traditional postpartum visit at 6 weeks after delivery. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecology has increased awareness of the postpartum period or “fourth trimester” of pregnancy and recommended that women with chronic medical conditions, including mood disorders and substance use disorders, should be counseled regarding the importance of timely follow-up with their obstetrician-gynecologists or primary care providers for ongoing coordination of care (McKinney et al., 2018).

Our results showed that 51.4% of delivery hospitalizations with MSUD diagnoses had Medicaid or Medicare as their primary expected payer, in comparison to 40.2% of delivery hospitalizations without MSUD diagnoses. MSUDs are among the most prevalent chronic conditions and incur high health service use during pregnancy through one year postpartum among persons who were covered by Medicaid at delivery (Pollack et al., 2022; Salahuddin et al., 2022). Structural and individual barriers to care among Medicaid and Medicare beneficiaries are wide ranging, such as lack of provider continuity, lack of transportation, and stigma related to insurance status or substance use (Bellerose et al., 2022; Pollack et al., 2022). In multivariable analysis, our result showed that Medicare or Medicaid insurance (vs private insurance) as primary expected payer was associated with higher odds of MSUD readmissions. Other studies have shown that insurance coverage can affect postpartum care access and Medicaid insurance is associated with obstetric hospital readmissions (Matthews et al., 2022; Reddy et al., 2021). To address insurance instability, which is a barrier to health care access in the postpartum period, particularly for those insured by Medicaid at delivery, states can implement strategies to extend Medicaid coverage up to 1 year postpartum (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2021). The extended postpartum coverage option through the American Rescue Plan offers states an opportunity to improve the continuity of care for chronic conditions, including MSUDs (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2021).

In addition to insurance coverage, our results highlight how other social determinants of health, such as living in the lowest quartile of median household income at zip code level, were associated with higher odds of MSUD readmissions. A recent study on assessment of multiple social needs (e.g., food, utilities, transportation) among Medicaid beneficiaries found that each of the 10 examined social needs was consistently associated with MSUDs (McQueen et al., 2021). MSUD clinical care can be improved by integrating interventions for meeting unmet social needs (Barfield, 2021; Byatt et al., 2020; Horbar et al., 2020).

4.1. Strength and limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, we were unable to account for MSUD care in settings such as outpatient MSUD management, including medications, therapy, or follow up visits with health care professionals. Second, we were unable to examine certain sociodemographic variables such as race/ethnicity because they were not included in the NRD. Racial and ethnic disparities in postpartum readmissions and the way that social determinants of health influence these disparities have been documented (Aseltine et al., 2015; Aziz et al., 2019; Matthews et al., 2022). Third, the characteristics assessed at delivery hospitalization may have changed by the time of readmission, such as insurance status. Fourth, the NRD only includes readmissions from community hospitals and does not include psychiatric hospitalizations. Fifth, we assessed the number of MSUDs present at delivery hospitalizations without further examining the co-occurrence of specific MSUDs. Despite these limitations, key strengths of this study include the use of population-based cohort data and use of a comprehensive list of MSUDs.

5. Conclusions

Our study documented MSUDs at delivery hospitalization and readmissions and assessed factors associated with MSUD readmissions. Factors associated with higher odds of readmission, such as type of MSUD, primary expected payer and community income levels, may present considerations for anticipatory care needs at the delivery hospitalization to reduce readmissions. Strategies to improve care for persons with MSUD at delivery can include improved follow-up screening and management of MSUDs in the postpartum period, equitable access to quality postpartum care, expanded Medicaid postpartum coverage, and addressing social determinants of health.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Table A1.

Clinical Classifications Software Refined Categories (CCSR) in the Mental, Behavioral and Neurodevelopmental Disorders Chapter by Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders (MSUD) inclusion status.

| CCSRa Category | CCSR Category Description |

|---|---|

| Included as MSUD | |

| MBD001 | Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders |

| MBD002 | Depressive disorders |

| MBD003 | Bipolar and related disorders |

| MBD004 | Other specified and unspecified mood disorders |

| MBD005 | Anxiety and fear-related disorders |

| MBD006 | Obsessive-compulsive and related disorders |

| MBD007 | Trauma- and stressor-related disorders |

| MBD008 | Disruptive, impulse-control and conduct disorders |

| MBD009 | Personality disorders |

| MBD010 | Feeding and eating disorders |

| MBD011 | Somatic disorders |

| MBD012 | Suicidal ideation/attempt/intentional self-harm |

| MBD013 | Miscellaneous mental and behavioral disorders/conditions |

| MBD017 | Alcohol-related disorders |

| MBD018 | Opioid-related disorders |

| MBD019 | Cannabis-related disorders |

| MBD020 | Sedative-related disorders |

| MBD021 | Stimulant-related disorders |

| MBD022 | Hallucinogen-related disorders |

| MBD023 | Inhalant-related disorders |

| MBD025 | Other specified substance-related disorders |

| Excluded as MSUD | |

| MBD014 | Neurodevelopmental disorders |

| MBD024 | Tobacco-related disorders |

| MBD026 | Mental and substance use disorders in remission |

| MBD027 | Suicide attempt/intentional self-harm; subsequent encounter |

| MBD028 | Opioid-related disorders; subsequent encounter |

| MBD029 | Stimulant-related disorders; subsequent encounter |

| MBD030 | Cannabis-related disorders; subsequent encounter |

| MBD031 | Hallucinogen-related disorders; subsequent encounter |

| MBD032 | Sedative-related disorders; subsequent encounter |

| MBD033 | Inhalant-related disorders; subsequent encounter |

| MBD034 | Mental and substance use disorders; sequela |

CCSR, Clinical Classifications Software Refined V2021.2. Detailed mapping between CCSR and ICD-10-CM codes is available online in the CCSR user’s guide.

Footnotes

Author disclosures

None.

Financial disclosures

None.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no conflicts to declare.

Appendix A

See Table A1.

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), 2019. Introduction to the HCUP Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD) 2019. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nrd/Introduction_NRD_2019.pdf (Accessed 8 February 2022).

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP),2021. User Guide: Clinical Classifications Software Refined (CCSR) for ICD-10-CM Diagnoses, v2021.2.https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccsr/DXCCSR-User-Guide-v2021-2.pdf(Accessed 8 February 2022).

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP),2022. Elixhauser Comorbidity Software Refined for ICD-10-CM.https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/comorbidityicd10/comorbidity_icd10.jsp(Accessed 8 February 2022).

- Aseltine RH Jr., Yan J, Fleischman S, Katz M, DeFrancesco M, 2015. Racial and ethnic disparities in hospital readmissions after delivery. Obstet. Gynecol 126 (5), 1040–1047. 10.1097/aog.0000000000001090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz A, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Siddiq Z, Wright JD, Goffman D, Sheen JJ, D’Alton ME, Friedman AM, 2019. Maternal outcomes by race during postpartum readmissions. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 220 (5), 484.e1–484.e10. 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barfield WD, 2021. Social disadvantage and its effect on maternal and newborn health. Semin. Perinatol 45 (4), 151407. 10.1016/j.semperi.2021.151407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett M, Steiner C, Andrews R, Kassed C, Nagamine M, 2011. HCUP Methods Series Report # 2011-01. Methodological Issues When Studying Readmissions and Revisits Using Hospital Administrative Data, http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/methods/methods.jsp (Accessed 8 February 2022).

- Barrett M, Lopez-Gonzalez L, Hines A, Andrews R, Jiang J, 2014. HCUP Methods Series Report # 2014-03. An Examination of Expected Payer Coding in HCUP Databases, http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/methods/methods.jsp (Accessed 26 February 2023).

- Bellerose M, Rodriguez M, Vivier PM, 2022. A systematic review of the qualitative literature on barriers to high-quality prenatal and postpartum care among low-income women. Health Serv. Res 57 (4), 775–785 10.1111/1475-6773.14008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byatt N, Masters GA, Bergman AL, Moore Simas TA, 2020. Screening for mental health and substance use disorders in obstetric settings. Curr. Psychiatry Rep 22 (11), 62 10.1007/s11920-020-01182-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022. Prevalence of Selected Maternal and Child Health Indicators for all PRAMS Sites, Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), 2016-2020. https://www.cdc.gov/prams/prams-data/mch-indicators/states/pdf/2020/All-Sites-PRAMS-MCH-Indicators-508.pdf (Accessed 27 October 2022).

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services,2021. SHO# 21-007 re: Improving Maternal Health and Extending Postpartum Coverage in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/sho21007.pdf (Accessed 8 February 2022).

- Chang G, 2020. Maternal substance use: consequences, identification, and interventions. Alcohol Res. 40 (2), 06. 10.35946/arcr.v40.2.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapp MA, Little SE, Zheng J, Robinson JN, 2016. A multi-state analysis of postpartum readmissions in the United States, 113.e111–113.e110. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 215 (1). 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.01.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapp MA, James KE, Friedman AM, 2020. Identification of delivery encounters using international classification of diseases, tenth revision, diagnosis and procedure codes. Obstet. Gynecol 136 (4), 765–767. 10.1097/aog.0000000000004099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conejo-Galindo J, Sanz-Giancola A, Álvarez-Mon M, Ortega M, Gutiérrez-Rojas L, Lahera G, 2022. Postpartum relapse in patients with bipolar disorder. J. Clin. Med 11 (14) 10.3390/jcm11143979. 〈https://doi〉. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis CL, Falah-Hassani K, Shiri R, 2017. Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 210 (5), 315–323. 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.187179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ecker J, Abuhamad A, Hill W, Bailit J, Bateman BT, Berghella V, Blake-Lamb T, Guille C, Landau R, Minkoff H, Prabhu M, Rosenthal E, Terplan M, Wright TE, Yonkers KA., 2019. Substance use disorders in pregnancy: clinical, ethical, and research imperatives of the opioid epidemic: a report of a joint workshop of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and American Society of Addiction Medicine. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 221 (1), b5–b28 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forray A, Foster D, 2015. Substance use in the perinatal period. Curr. Psychiatry Rep 17 (11), 91. 10.1007/s11920-015-0626-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T, 2005. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet. Gynecol 106 (5 Pt 1), 1071–1083. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girsen AI, Leonard SA, Butwick AJ, Joudi N, Carmichael SL, Gibbs RS, 2022. Early postpartum readmissions: identifying risk factors at birth hospitalization. AJOG Glob. Rep 2 (4), 100094 10.1016/j.xagr.2022.100094. 〈https://doi〉. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulbransen K, Thiessen K, Pidutti J, Watson H, Winkler J, 2022. Scoping review of best practice guidelines for care in the labor and birth setting of pregnant women who use methamphetamines. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs 51 (2), 141–152. 10.1016/j.jogn.2021.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haight SC, Byatt N, Moore Simas TA, Robbins CL, Ko JY, 2019. Recorded diagnoses of depression during delivery hospitalizations in the United States, 2000-2015. Obstet. Gynecol 133 (6), 1216–1223. 10.1097/aog.0000000000003291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai AH, Ko JY, Owens PL, Stocks C, Patrick SW, 2021. Neonatal abstinence syndrome and maternal opioid-related diagnoses in the US, 2010-2017. JAMA 325 (2) , 146–155. 10.1001/jama.2020.24991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horbar JD, Edwards EM, Ogbolu Y, 2020. Our responsibility to follow through for NICU infants and their families. Pediatrics 146 (6). 10.1542/peds.2020-0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell BA, Abel EA, Park D, Edmond SN, Leisch LJ, Becker WC, 2021. Validity of incident opioid use disorder (OUD) diagnoses in administrative data: a chart verification study. J. Gen. Intern. Med 36, 1264–1270. 10.1007/s11606-020-06339-. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones I, Chandra PS, Dazzan P, Howard LM, 2014. Bipolar disorder, affective psychosis, and schizophrenia in pregnancy and the post-partum period. Lancet 384 (9956), 1789–1799. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61278-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HM, Smith EG, Stano CM, Ganoczy D, Zivin K, Walters H, Valenstein M, 2012. Validation of key behaviourally based mental health diagnoses in administrative data: suicide attempt, alcohol abuse, illicit drug abuse and tobacco use. BMC Health Serv. Res. 12 (1), 1–9. 10.1186/1472-6963-12-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko JY, Haight SC, 2020. Addressing perinatal mental health and opportunities for public health. Am. J. Public Health 110 (6), 765–767. 10.2105/ajph.2020.305663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Rao A, O’Rourke K, Hanrahan N, 2019. Relationship between depression and/or anxiety and hospital readmission among women after childbirth. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs 48 (5), 552–562. 10.1016/j.jogn.2019.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logue TC, Wen T, Monk C, Guglielminotti J, Huang Y, Wright JD, D’Alton ME, Friedman AM, 2022. Trends in and complications associated with mental health condition diagnoses during delivery hospitalizations. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 226 (3), 405.e401–405.e416. 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews KC, Tangel VE, Abramovitz SE, Riley LE, White RS, 2022. Disparities in obstetric readmissions: a multistate analysis, 2007-2014. Am. J. Perinatol 39 (2), 125–133. 10.1055/s-00411739310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee K, Admon LK, Winkelman TNA, Muzik M, Hall S, Dalton VK, Zivin K, 2020. Perinatal mood and anxiety disorders, serious mental illness, and delivery-related health outcomes, United States, 2006-2015. BMC Women’s Health 20 (1), 150 10.1186/s12905-020-00996-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney J, Keyser L, Clinton S, Pagliano C, 2018. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 736: optimizing postpartum care. Obstet. Gynecol. 132 (3), 784–785. 10.1097/aog.0000000000002849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen A, Li L, Herrick CJ, Verdecias N, Brown DS, Broussard DJ, Smith RE, Kreuter M, 2021. Social needs, chronic conditions, and health care utilization among medicaid beneficiaries. Popul. Health Manag. 24 (6), 681–690. 10.1089/pop.2021.0065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor E, Rossom RC, Henninger M, Groom HC, Burda BU, 2016. Primary care screening for and treatment of depression in pregnant and postpartum women: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 315 (4), 388–406. 10.1001/jama.2015.18948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack LM, Chen J, Cox S, Luo F, Robbins CL, Tevendale HD, Li R, Ko JY, 2022. Healthcare utilization and costs associated with perinatal depression among medicaid enrollees. Am. J. Prev. Med 62 (6), e333–e341. 10.1016/j.amepre.2021.12.00841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffi ER, Gray J, Conteh N, Kane M, Cohen LS, Schiff DM, 2021. Low barrier perinatal psychiatric care for patients with substance use disorder: meeting patients across the perinatal continuum where they are. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 33 (6), 543–552. 10.1080/09540261.2021.1898351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy R, James KE, Mauney LC, Kaimal AJ, Daw JR, Clapp MA, 2021. Postpartum readmission and uninsurance at readmission for medicaid versus privately insured births. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM, 100553. 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salahuddin M, Matthews KJ, Elerian N, Ramsey PS, Lakey DL, Patel DA, 2022. Health burden and service utilization in Texas medicaid deliveries from the prenatal period to 1 year postpartum. Matern. Child Health J. 26 (5), 1168–1179 10.1007/s10995-022-03428-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salemi JL, Raza SA, Modak S, Fields-Gilmore JAR, Mejia de Grubb MC, Zoorob RJ, 2020. The association between use of opiates, cocaine, and amphetamines during pregnancy and maternal postpartum readmission in the United States: a retrospective analysis of the Nationwide Readmissions Database. Drug Alcohol Depend. 210, 107963 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.107963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sithisarn T, Granger DT, Bada HS, 2012. Consequences of prenatal substance use. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 24 (2), 105–112. 10.1515/ijamh.2012.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuebe AM, Kendig S, Suplee PD, D’Oria R, 2021. Consensus bundle on postpartum care basics: from birth to the comprehensive postpartum visit. Obstet. Gynecol 137 (1), 33–40. 10.1097/aog.0000000000004206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters GA, Hugunin J, Xu L, Ulbricht CM, Moore Simas TA, Ko JY, Byatt N, 2022. Prevalence of Bipolar Disorder in Perinatal Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 83 (5), 21r14045. 10.4088/JCP.21rl4045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration,2018. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 18-5054. Clinical Guidance for Treating Pregnant and Parenting Women with Opioid Use Disorder and Their Infants, https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/sma18-5054.pdf (Accessed 8 February 2022).

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration,2019. NSDUH Detailed Tables, https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2019-nsduh-detailed-tables (Accessed 8 February 2022).

- Trost SL, Beauregard J, Njie Fd, et al. , 2022. Pregnancy-Related Deaths: Data from Maternal Mortality Review Committees in 36 US States, 2017–2019. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/docs/pdf/Pregnancy-Related-Deaths-Data-MMRCs-2017-2019-H.pdf. Accessed 8 March 2023). [Google Scholar]

- Trost SL, Beauregard JL, Smoots AN, Ko JY, Haight SC, Moore Simas TA, Byatt N, Madni SA, Goodman D, 2021. Preventing pregnancy-related mental health deaths: insights from 14 US Maternal Mortality Review Committees, 2008-17. Health Aft. 40 (10), 1551–1559. 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb R, Uddin N, Ford E, Easter A, Shakespeare J, Roberts N, Alderdice F, Coates R, Hogg S, Cheyne H, Ayers S, 2021. Barriers and facilitators to implementing perinatal mental health care in health and social care settings: a systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry 8 (6), 521–534. 10.1016/s2215-0366(20)30467-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss A, Head M, Reid LD,2022. Mental Health Disorders Among Delivery Inpatient Stays by Patient Race and Ethnicity, 2020. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs #302. https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb302-Deliveries-Mental-Health-Disorders-Race-2020.jsp (Accessed 26 February 2023).

- Wen T, Fein AW, Wright JD, Mack WJ, Attenello FJ, D’Alton ME, Friedman AM, 2021. Postpartum psychiatric admissions in the United States. Am. J. Perinatol. 38 (2), 115–121 10.1055/s-0039-1694759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen T, Batista N, Wright JD, D’Alton ME, Attenello FJ, Mack WJ, Friedman AM, 2019. Postpartum readmissions among women with opioid use disorder. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 1 (1), 89–98. 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2019.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]