Abstract

This cross-sectional study evaluates racial disparities in physical restraint use in US emergency departments.

In Yale New Haven Health System emergency departments (EDs), Black children were reported to be 1.8 times more likely to be physically restrained than White children.1 Applying an intersectional lens, we examined sex and age as potential modifiers of these racial inequities.

Methods

We performed a cross-sectional study of ED visits from the Yale New Haven health care system to examine previously identified racial disparities between non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White (henceforth Black and White, respectively) patients.1 We included Black and White patients aged 5 to 16 years between January 2013 and December 2021. The study was deemed exempt by Yale University’s institutional review board and followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

The primary outcome was proportion of ED visits with a physical restraint order. Our explanatory variable was patient race (Black, White), and proposed moderators were patient sex (female, male) and age, as documented in the electronic health record. We explored associations between physical restraint, race, sex, and age using multivariable mixed-effects logistic regression, clustering visits by patient and including an interaction term between race and each moderator. For models with statistically significant interaction terms, we reported probabilities of restraint using marginal effects and stratified logistic regression. Analyses were conducted using Stata version 17 (StataCorp).

Results

There were 189 259 ED visits by 86 899 Black or White children. A physical restraint order was placed in 203 of 71 733 visits (0.28%) for Black children and 195 of 117 526 visits (0.17%) for White children (P < .001). Physical restraint was more common among visits for boys than girls (264 of 99 838 [0.26%] vs 134 of 89 420 [0.15%]; P < .001). The mean (SD) age of restraint was 13.0 (3.1) years (Table).

Table. Adjusted Odds of Physical Restraint by Visit Characteristics in the Full Sample Stratified by Sexa,b.

| Full sample | Stratified by sex, aOR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visits with a restraint order | Female | Male | ||

| No. (%) | aOR (95% CI)a,c | |||

| Race | ||||

| Black | 203 (0.28) | 1.96 (1.49-2.58) | 2.52 (1.56-4.07) | 1.69 (1.22-2.35) |

| White | 195 (0.17) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 134 (0.15) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Male | 264 (0.26) | 2.18 (1.66-2.86) | NA | NA |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 12.99 (3.05) | 1.08 (1.02-1.13) | 1.05 (0.96-1.15) | 1.09 (1.03-1.14) |

| Language preference | ||||

| English | 383 (0.20) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Language other than English | 15 (0.65) | 3.92 (1.71-8.97) | NAd | 5.96 (2.63-13.347) |

| Insurance type | ||||

| Private | 128 (0.14) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Public | 267 (0.31) | 1.37 (1.03-1.80) | 1.77 (1.10-2.87) | 1.16 (0.83-1.63) |

| Other | 3 (0.03) | 0.39 (0.12-1.27) | NAd | 0.53 (0.16-1.76) |

| Presentation during a school month | ||||

| Yes | 297 (0.22) | 0.82 (0.62-1.06) | 0.82 (0.52-1.28) | 0.83 (0.60-1.15) |

| No | 101 (0.21) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Behavioral health chief concern | ||||

| Yes | 329 (2.69) | 33.45 (22.63-49.42) | 36.00 (18.14-71.41) | 32.94 (20.43-53.13) |

| No | 69 (0.04) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Behavioral health outpatient medications | ||||

| Yes | 298 (1.00) | 2.72 (1.96-3.77) | 2.80 (1.55-5.07) | 2.70 (1.83-3.99) |

| No | 100 (0.01) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| History of a behavioral health condition | ||||

| Yes | 181 (0.98) | 1.78 (1.36-2.33) | 1.86 (1.16-3.00) | 1.74 (1.25-2.41) |

| No | 217 (0.13) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted odds ratio; NA, not applicable.

Race by sex interaction term P = .04.

Race by age interaction term P value = .26; full model results not included due to nonsignificant interaction terms.

P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Did not report odds ratios present for visit categories with zero restraint observations.

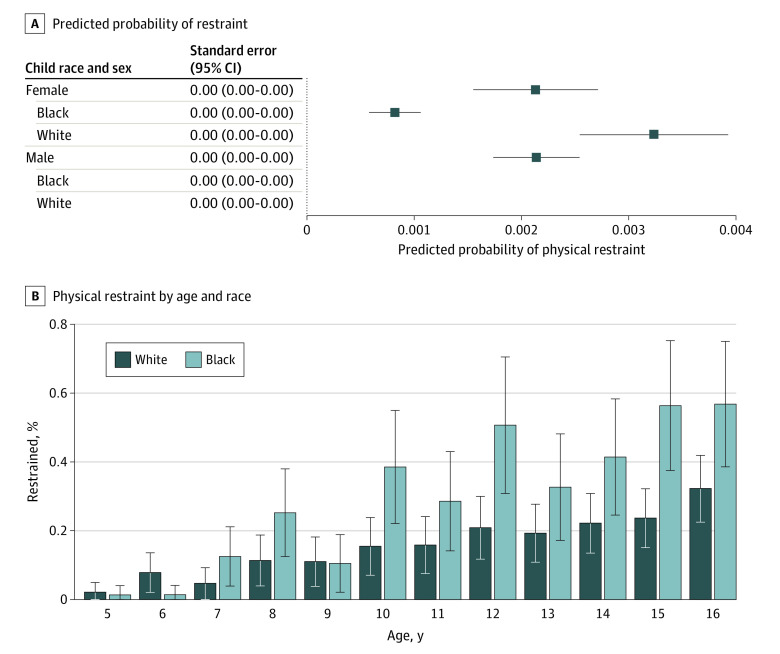

In the multivariable model among the aggregate sample, the race and sex interaction was statistically significant. The absolute difference in probabilities of restraint in Black girls vs White girls was larger than that between Black boys and White boys (0.13% vs 0.11%) (Figure). In models stratified by sex, Black girls had a 2.52-times higher odds of restraint compared to White girls (95% CI, 1.56-4.07); Black boys had a 1.69-times higher odds of restraint compared to White boys (95% CI, 1.22-2.35) (Table).

Figure. Visualizing Modifiers of Racial Disparities in Pediatric Restraint.

The interaction term between race and age was not statistically significant. After age 7 years, the proportion of visits for Black children with a physical restraint order was higher than those for White children at almost every age, although only statistically significant at ages 12 and 15 years (Figure).

Discussion

In this study, racial disparities in pediatric physical restraint differed by sex. Disparities between Black and White race were larger in girls compared to boys, although restraint was more common in boys overall.

We interpret our results in the context of other disciplines that study disparities in punitive approaches to child behavior. For example, Black children are suspended or expelled from school at higher rates than White children,2 and this disparity is wider among girls than boys.3 Black girls face punishment in school for subjective infractions like “disobedience” or “speaking loudly.”3,4 Extrapolating to health care, gendered expectations of Black girls may influence disproportionate use of restraint.

We hypothesized that Black children would be restrained at younger ages due to adultification bias—a perception of Black children as older and less innocent.3 Racial disparities in restraint did not differ significantly by age; however, physical restraint frequencies appeared to increase faster with age for Black children compared to White children.

Physical restraint is rare, potentially limiting power to detect associations between race and age. It is unknown whether race, ethnicity, and gender data in the electronic health record are self-reported. Electronic medical records do not reliably identify multiracial or gender-nonconforming individuals. Further studies should include additional race and ethnicity groups.

Increasingly strained emergency mental health systems risk worsening health care inequities.5 Aggregate data obscure patterns of disparities experienced by individuals with multiple marginalized identities. By applying an intersectional lens we can develop targeted strategies to reduce inequities for those most at risk.6

Data sharing statement.

References

- 1.Nash KA, Tolliver DG, Taylor RA, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in physical restraint use for pediatric patients in the emergency department. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(12):1283-1285. Medline: doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.3348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.United States Government Accountability Office . K-12 Education: discipline disparities for black students, boys, and students with disabilities. Published March 22, 2018. Accessed May 17, 2022. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-18-258

- 3.Epstein R, Blake JJ, González T. Girlhood interrupted: the erasure of black girls’ childhood. Social Science Research Network . 2017. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3000695

- 4.Morris MW, Bush-baskette S, Harris L, et al. Race, gender and the school-to-prison pipeline. Afr Am Policy Forum. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://youthrex.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Morris-Race-Gender-and-the-School-to-Prison-Pipeline.pdf

- 5.Hoffmann JA, Alegr M, Simon KM, Lee LK. Disparities in pediatric mental and behavioral health conditions. Pediatrics. 2022;150(4):e2022058227. doi: 10.1542/peds.2022-058227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Black Women’s Justice Institute . End school pushout for Black girls and other girls of color. Published online 2019. Accessed February 16, 2023. https://pushoutfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/policy-draft.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data sharing statement.