Abstract

Cerebral sinus vein thrombosis (CVT) is a relatively rare neurovascular entity, usually associated with acquired or genetic hypercoagulable states, and in many cases it remains idiopathic. Trauma is also associated with CVT among patients with major head or neck trauma, including penetrating injuries. However, CVT associated with acceleration trauma has only been described in few cases so far. We present an unusual case of a 19-year-old woman with no past medical history, admitted with an extensive CVT following sneezing. A thorough investigation did not reveal any other potential etiology or risk factor other than estrogen-containing oral contraceptives. The patient was treated with anticoagulation and improved clinically with complete recanalization on follow-up imaging. This case suggests acceleration trauma may be a potential factor of risk for CVT.

Keywords: Cerebral sinus vein thrombosis, Acceleration trauma, Case report

Introduction

Cerebral sinus venous thrombosis (CVT) accounts for approximately 1% of all forms of stroke [1]. It is an important cause of cerebrovascular disease in young adults, with a mean age of 33 years old and a two-thirds female preponderance [2]. CVT is associated with various etiologies and conditions including coagulopathies, malignancy, concurrent infection, pregnancy and peripartum period, estrogen-containing oral contraceptives, smoking, and connective tissue disorders among others [3, 4]. CVT can also be associated with trauma; however, it mainly refers to major head or neck trauma, including penetrating injury to skull fracture, dural sinuses, jugular veins, or during neurosurgical procedures [5]. CVT associated with acceleration or minor trauma is limited to a few case reports [6–8].

CVT is frequently missed or diagnosed late since it can mimic other acute neurological conditions and can only be recognized with a specific brain image [9]. We report the occurrence of CVT secondary to acceleration trauma which may be an under-recognized precipitating factor.

Case Report

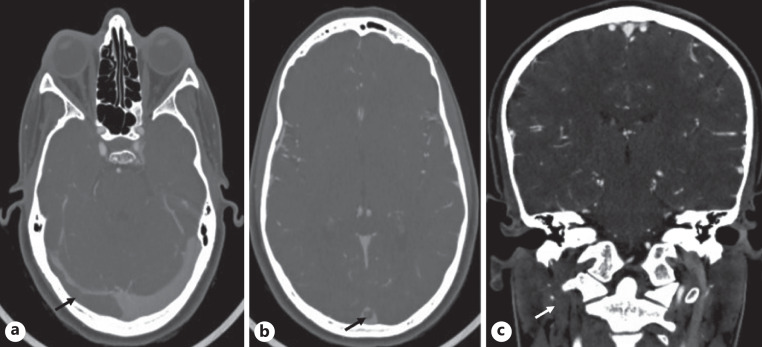

A 19-year-old patient with no past medical history presented with a severe right temporal headache one day following sneezing. The headache began immediately after sneezing and was accompanied by nausea with no vomiting or focal neurological symptoms. Treatment with analgesics resulted in some improvement. On the day of admission, a second sneeze resulted in an acute worsening headache, however, with no improvement with treatment. The patient denied preceding trauma other than sneezing, upper respiratory symptoms, smoking, or substance abuse. There was no family history of thrombotic events or known hypercoagulable states. She had no risk factors other than oral contraceptives. On neurological examination, she was fully conscious and oriented, without neck stiffness, swollen discs, or focal neurological signs. Non-contract computerized tomography showed an abnormal hyperdense signal in the right transverse dural sinus compatible with an acute sinus thrombosis (Fig. 1). Computed tomography angiography demonstrated an extensive filling defect in the right jugular vein, sigmoid sinus, and transverse sinus, as well as in the superior sagittal. An empty delta sign in the superior sagittal sinus was also demonstrated (Fig. 2a–c). No anatomical abnormality or other vascular lesions were shown. Laboratory results showed no signs of infectious or inflammatory disease, and no thrombophilia was found; ANA, ANCA, antiphospholipid antibodies, lupus anticoagulant, protein C, factor VIII, factor V-Leiden, antiprothrombin, and MTHFR were all negative. Low levels of protein S were probably due to anticoagulation treatment started earlier. JAK2 mutation was also negative. D-dimer level was elevated (1.07 mg/L; reference range 0.05–0.55).

Fig. 1.

Non-contrast head CT demonstrates an abnormal hyperdense signal in the right transverse sinus compatible with an acute sinus thrombosis. CT, computed tomography.

Fig. 2.

a CTA confirms a filling defect in the right jugular vein, sigmoid sinus, and transverse sinus. b The superior sagittal sinus shows a classic empty delta sign. c Coronal image demonstrates a filling defect in the right jugular vein with no evidence of venous dissection. CTA, computed tomography angiography.

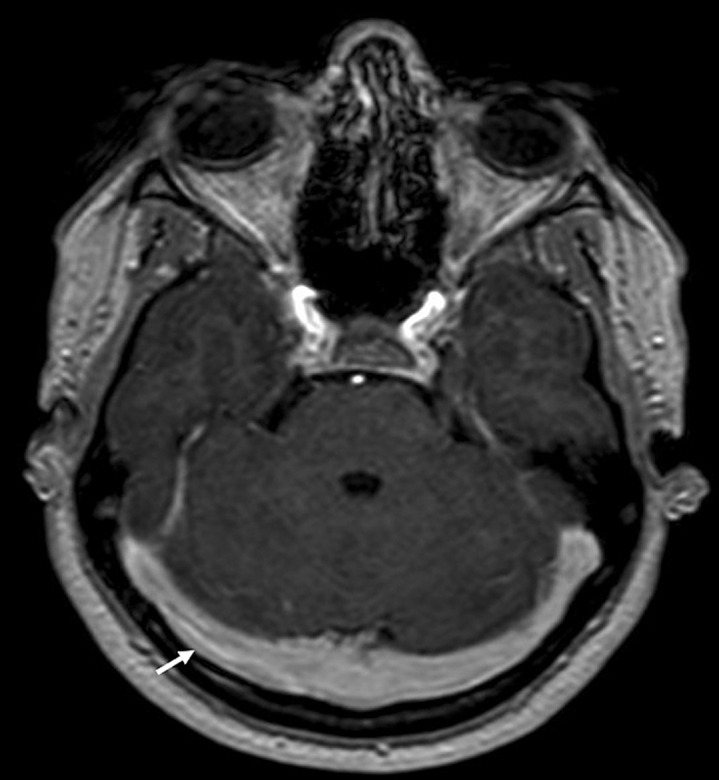

The patient was treated with low molecular weight heparin and discharged 4 days later with complete resolution of headaches and without evidence of swollen discs on follow-up examination. At follow-up, she remained well with no headaches or new neurological symptoms. She continued treatment with warfarin at therapeutic INR levels. Follow-up magnetic resonance venography demonstrated complete recanalization (Fig. 3). The CARE Checklist has been completed by the authors for this case report, attached as online supplementary material (for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000530812).

Fig. 3.

Follow-up brain MRV demonstrates complete recanalization. MRV, magnetic resonance venography.

Discussion

CVT is an uncommon neurovascular disorder associated with a wide range of conditions and etiologies including trauma. We present a unique case of a young female patient with extensive dural sinus thrombosis following sneezing.

There are few published reports which describe the association between CVT and acceleration or minor trauma, such as sneezing, golf swing, or jumping from a low altitude [6–8]. Similar to our case, all of these patients had at least one predisposing factor such as oral contraceptive use, smoking, or a moderate anticardiolipin antibody level. The exact mechanism for the development of thrombosis following acceleration trauma is unclear. Rottger et al. [6] suggested the mechanism to be a combination of an acceleration trauma, where brain structures impact against fixed dural structures, and eventually a sudden rise in ICP causing damage to the endothelial layer of sinuses and cerebral veins. Bone fragments, sinus dissection, and sinus distortion that may create obstructions to flow and thrombus formation were mentioned by D’Alise et al. [8].

The close temporal association between two sneezing and headache episodes and CVT diagnosis in our case strongly suggests a causal relationship. Moreover, abnormal hyperdensity on initial non-contract computerized tomography is compatible with an acute process, and it seems unlikely that an extensive thrombosis would have been asymptomatic prior to sneezing.

This case describes a rare cause of an uncommon neurovascular disorder. We suggest incorporating head acceleration trauma as a potential factor of risk for CVT. Moreover, it is reasonable to consider computed tomography and CVT for patients who present with a headache after acceleration trauma.

Statement of Ethics

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of the details of their medical case and any accompanying images. Ethical approval is not required for this study in accordance with local guidelines.

Conflict of Interest Statement

None of the authors have any financial disclosures or conflicts of interests.

Funding Sources

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author Contributions

Helal Nashef conceptualized and designed the work including data acquisition and drafting of the manuscript. Rom Mendel took part in the drafting of the manuscript and in its revision. Salo Haratz took part in the manuscript revision. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

I take full responsibility for the data, the analyses, and the interpretation. All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its online supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Bousser MG, Ferro JM. Cerebral venous thrombosis: an update. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(2):162–70. 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70029-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Coutinho JM, Zuurbier SM, Stam J. Declining mortality in cerebral venous thrombosis: a systematic review. Stroke. 2014;45(5):1338–41. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.004666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Towbin A. The syndrome of latent cerebral venous thrombosis: its frequency and relation to age and congestive heart failure. Stroke. 1973;4(3):419–30. 10.1161/01.str.4.3.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Canhao P, Ferro JM, Lindgren AG, Bousser MG, Stam J, Barinagarrementeria F, et al. Causes and predictors of death in cerebral venous thrombosis. Stroke. 2005;36(8):1720–5. 10.1161/01.STR.0000173152.84438.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ferro JM, Canhão P, Stam J, Bousser MG, Barinagarrementeria F; ISCVT Investigators . Prognosis of cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis: results of the international study on cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis (ISCVT). Stroke. 2004;35(3):664–70. 10.1161/01.STR.0000117571.76197.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rottger C, Trittmacher S, Gerriets T, Kaps M, Stolz E. Sinus thrombosis after a jump from a small rock and a sneezing attack: minor endothelial trauma as a precipitating factor for cerebral venous thrombosis? Headache. 2004;44(8):812–5. 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2004.04150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Saneto RP, Samples S, Kinkel P. Traumatic intracerebral venous thrombosis associated with an abnormal golf swing. Headache. 2000;40(7):595–8. 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2000.00093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. D’Alise MD, Fichtel F, Horowitz M. Sagittal sinus thrombosis following minor head injury treated with continuous urokinase infusion. Surg Neurol. 1998;49(4):430–5. 10.1016/s0090-3019(97)00182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Linn J, Ertl-Wagner B, Seelos KC, Strupp M, Reiser M, Brückmann H, et al. Diagnostic value of multidetector-row CT angiography in the evaluation of thrombosis of the cerebral venous sinuses. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28(5):946–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

I take full responsibility for the data, the analyses, and the interpretation. All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its online supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.