Abstract

BACKGROUND

Upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is a life-threatening condition with high mortality rates.

AIM

To compare the performance of pre-endoscopic risk scores in predicting the following primary outcomes: In-hospital mortality, intervention (endoscopic or surgical) and length of admission (≥ 7 d).

METHODS

We performed a retrospective analysis of 363 patients presenting with upper GI bleeding from December 2020 to January 2021. We calculated and compared the area under the receiver operating characteristics curves (AUROCs) of Glasgow-Blatchford score (GBS), pre-endoscopic Rockall score (PERS), albumin, international normalized ratio, altered mental status, systolic blood pressure, age older than 65 (AIMS65) and age, blood tests and comorbidities (ABC), including their optimal cut-off in variceal and non-variceal upper GI bleeding cohorts. We subsequently analyzed through a logistic binary regression model, if addition of lactate increased the score performance.

RESULTS

All scores had discriminative ability in predicting in-hospital mortality irrespective of study group. AIMS65 score had the best performance in the variceal bleeding group (AUROC = 0.772; P < 0.001), and ABC score (AUROC = 0.775; P < 0.001) in the non-variceal bleeding group. However, ABC score, at a cut-off value of 5.5, was the best predictor (AUROC = 0.770, P = 0.001) of in-hospital mortality in both populations. PERS score was a good predictor for endoscopic treatment (AUC = 0.604; P = 0.046) in the variceal population, while GBS score, (AUROC = 0.722; P = 0.024), outperformed the other scores in predicting surgical intervention. Addition of lactate to AIMS65 score, increases by 5-fold the probability of in-hospital mortality (P < 0.05) and by 12-fold if added to GBS score (P < 0.003). No score proved to be a good predictor for length of admission.

CONCLUSION

ABC score is the most accurate in predicting in-hospital mortality in both mixed and non-variceal bleeding population. PERS and GBS should be used to determine need for endoscopic and surgical intervention, respectively. Lactate can be used as an additional tool to risk scores for predicting in-hospital mortality.

Keywords: Glasgow-Blatchford; Pre-endoscopic Rockall; Age older than 65; Age, blood tests and comorbidities; Risk score; Gastrointestinal bleeding

Core Tip: Upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is a life-threatening condition with high mortality rates. It represents one of the main reasons for presentation in the emergency department, having a major impact on both the patient and the clinician. This cohort study evaluates four of the mostly used pre-endoscopic risk scores by comparing them in two populations, variceal and non-variceal upper GI bleeding, highlighting which one should be preferably used depending on the investigated outcome.

INTRODUCTION

Upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is defined as blood loss from the GI tract above the ligament of Treitz. It is a life-threatening condition with high mortality rates, of up to 15%[1]. This is particularly important as emergency services are struggling with high patient flow[2] and clinicians must promptly decide the need for admission, timing of endoscopy and level of care. It is generally recommended to perform endoscopy within 24 h of presentation[3]. It plays a pivotal role in identifying the source of bleeding and it can achieve haemostasis in most cases. However, endoscopy may not be available in all centers or, if performed in low-risk patients, it may overcrowd the service with unnecessary urgent interventions.

European Society of Gastroenterology recommends immediate assessment of patient’s haemodynamic status, transfusion strategy and risk stratification[4]. The latter can be achieved by calculating GI bleeding risk scores which should predict several outcomes such as need for intervention, mortality, rebleeding rate or death[5]. Pre-endoscopy risk scores have been increasingly used as they rely on limited number of parameters and may allow timely sequential decisions. Glasgow-Blatchford score (GBS)[6] has been validated to identify low risk patients which may be managed as outpatients. PERS[7] evaluates the risk of rebleeding and mortality, while albumin, international normalized ratio, altered mental status, systolic blood pressure, age older than 65 (AIMS65)[8], determines the risk of death. Age, blood tests and comorbidities (ABC) is a relatively new risk score used to predict mortality in patients with both upper and lower GI bleeding[9]. These scores have been previously compared, with a certain variability among studies, potentially due to the differences in population included. Moreover, there is limited data for variceal upper GI bleeding, with most of the studies including non-variceal cohorts[10,11].

Venous lactate can be an important tool in critically ill patients, such as those with shock, trauma, or heart failure. It increases as a result of tissue hypoperfusion or hypoxia. Although not routinely used, it can predict in-hospital mortality, need for intensive care or surgical intervention, as well as rebleeding in patients with upper GI bleed[12]. It may be used to improve the performance of existing scoring systems[13] and guide clinicians towards early triage of patients.

In this study, we aim to evaluate the performance of pre-endoscopic risk scores (GBS, PERS, AIMS65, and ABC) in patients with variceal and non-variceal upper GI bleeding for predicting the following primary outcomes: In-hospital mortality, type of intervention (endoscopic or surgical) and length of admission (≥ 7 d). We will further evaluate whether the addition of venous lactate improves the score performance in predicting the determined outcomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted a single centre cohort study, performed in a tertiary emergency hospital, “Saint Spiridon’’ Emergency University Hospital, Iasi, Romania. We retrospectively analyzed all patients above 18 years old presenting to the emergency department (ED) with upper GI bleeding from January 2020 to December 2021.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Hospital’s Ethics Committee. The ‘’Saint Spiridon’’ Institutional Review Board approved this study, approval number 39/30.03.2022. Each patient signed our standard informed consent. We did not require additional consent as patient data is anonymous and the study included standard of care information.

Patient management

Each patient presenting with upper GI bleed exteriorized as hematemesis, coffee ground vomiting or melena was fully assessed by the emergency medicine physician, including past medical history and complete clinical examination. Immediate venous catheterization and fluid resuscitation was performed as indicated following primary assessment. Subsequent full work-up with blood tests (full blood count, haemoglobin (Hb), platelets, INR, aPTT, albumin, ALT, AST, urea, creatinine, and venous lactate), and other investigations (as indicated) were performed within 24 h from presentation. Hemodynamically stable patients with a Hb ≤ 7 g/dL had at least one unit of red blood cell concentrate transfused, with more than one unit in those with severely lower Hb. A higher Hb threshold (Hb ≤ 8 g/dL) was used for patients with associated cardiovascular disease. Post-transfusion target Hb was between 7-9 g/dL. In case of major transfusion protocol, severe liver disease, drug-induced coagulopathy with active bleeding, patients received both red cell concentrate and fresh frozen plasma. Endoscopy was performed within 24 h of ED arrival in all patients included in analysis. Forrest classification was used to describe peptic ulcer disease, with Baveno and Sarin’s classification for gastroesophageal varices. Those with suspected variceal bleeding had endoscopic evaluation and management within 6 h to 12 h, after initial appropriate fluid resuscitation. In those with non-variceal upper GI bleeding, endoscopy was performed within the first 12 h to 24 h with no patient being postponed more than 24 h. However, we would perform the intervention earlier guided by the patient’s clinical status and the clinician’s preference. Patients with non-variceal upper GI bleeding received an infusion with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), while those with variceal bleeding were treated with Somatostatin. Endoscopic treatment was performed depending on the cause of bleeding. For non-variceal upper GI bleeding, there was a combined approach with injection therapy (dilute epinephrine) and mechanic therapy (thermal coagulation or haemostatic clip) for FIa, Fib, and FIIa, with clot removal in FIIb lesions. In variceal bleeding, endoscopic ligation was the main approach. Surgical treatment was performed in cases where endoscopic treatment failed, such as actively bleeding malignant lesion, vascular fistula, or in patients with bleeding perforated ulcer. Need for admission was established by the gastroenterology and general surgery teams on-call guided by the patient’s clinical status, comorbidities, and high risk of rebleeding and mortality (GBS score ≥ 2 in non-variceal patients and all patients with stigmata of variceal bleeding irrespective of risk score).

Data collection

Initially, a ward clerk extracted all data from ED’s computer data. Further exclusion of duplicates/incomplete files was performed. We extracted from the patient’s records and electronic files, the following data: age, gender, comorbidities (heart failure, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, liver cirrhosis, active malignancy, hepatocarcinoma, and cerebral vascular disease), symptoms on presentation (hematemesis, melena, coffee ground vomiting, abdominal pain, and syncope), vital signs (systolic blood pressure, heart rate), blood parameters needed to calculate the GBS, PERS, AIMS65 and ABC scores, venous lactate level, source of bleeding if identified by endoscopy (variceal bleeding- oesophageal and/or gastric varices and non-variceal bleeding-gastric/duodenal ulcer, severe/erosive gastritis or duodenitis, severe/erosive esophagitis, Mallory Weiss syndrome, GI malignancy, angiodysplasia, Dieulafoy lesion), type of endoscopic intervention (no intervention, injection therapy, mechanical intervention) or surgical intervention, length of admission (number of days), need for transfusion on admission and in-hospital survival. Venous lactate was measured using Radiometer ABL 90 Series I393-09.

Patients were excluded if they were unable to undergo/did not consent for endoscopy or surgical intervention, had a final diagnosis of non-upper GI bleeding, were also diagnosed with sepsis, pregnancy, severe trauma, were taking Metformin, had incomplete data for score calculation or venous lactate was not determined.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software for Windows (v.22.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States). The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by I.L. Rusu, biomedical statistician. Nominal variables are presented as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables as the mean ± SD. We were able to apply all tests as the score values are homogenous, median value is similar to the mean value and skeweness test had [-2÷ 2] interval. Categorical variables were presented as percentages and compared using Chi-square test. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We determined the scores’ ability to predict each investigated outcome by calculating the area under the receiver operating characteristics curves (AUROCs), including optimal cut-off value with specificity and sensitivity and 95% confidence intervals. AUROCs were determined significant for a value above 0.600. Subsequently, we analyzed through a logistic binary regression model, if addition of lactate to the risk scores increased the probability of previously determined outcomes.

RESULTS

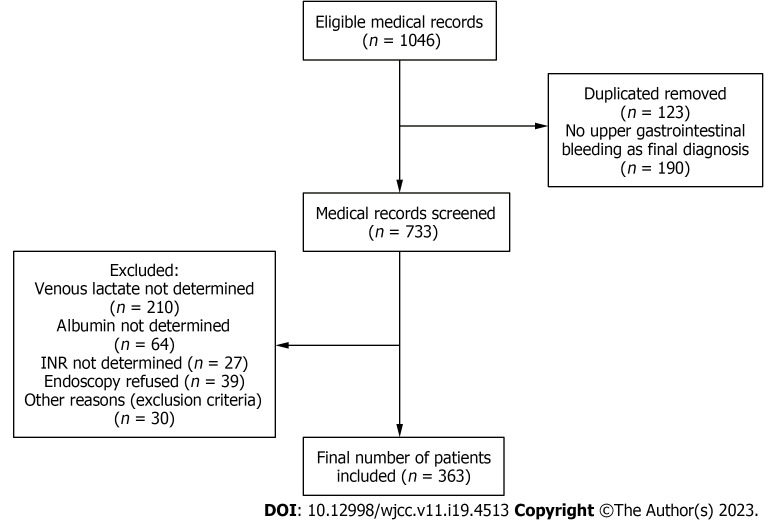

A total of 1046 medical records were considered eligible (Figure 1). We excluded duplicates or patients with more than one presentation within the study period. After applying the exclusion criteria, the study ended with a cohort of 363 patients with upper GI bleeding with a mean age of 60 years old and a predominance of male sex (n = 240, 66.1%). Non-variceal bleeding was the main cause of presentation (n = 236, 65%). Liver cirrhosis is the most frequent associated comorbidity in the entire group (n = 139, 38.3%), and 2.5% (n = 9) of patients had associated hepatocarcinoma (Table 1). The main symptom of presentation was haematemesis in patients with variceal bleeding and melena in the non-variceal group. Approximately 9% of our patients had chronic treatment with antiplatelets (n = 36, 9.9%) or oral anticoagulation (n = 32, 8.9%). Gastric/duodenal ulcer was the main cause of GI bleeding (n = 151, 41.6%), followed by oesophageal varices (n = 115, 31.7%). Most patients in variceal bleeding group required mechanical endoscopic therapy with band ligation (n = 48, 13.2%) and only 2 patients (0.6%) had variceal sclerotherapy. In the non-variceal bleeding group, dual therapy with thermal anticoagulation and local administration of dilute Adrenaline was the main type of endoscopic intervention (n = 29, 8.0%). Failed endoscopy was recorded in approximately 4.7% (n = 17) of patients. Only 9 patients in the non-variceal group required surgical intervention, in most cases due to actively bleeding perforated duodenal ulcer, inability to achieve local haemostasis in diffuse bleeding induced by malignancy or fistulas. Approximately 31% (n = 112) of the population in both groups required transfusion. In-hospital mortality had an overall rate of 9.4% (n = 34), most cases (n = 16, 12.6%) were in the variceal group (Table 1). The direct cause of death was hypovolaemic shock secondary to upper GI bleeding (in most cases variceal). There were several cases of perforated duodenal ulcer which required emergency surgery, but with poor outcome. One patient developed ventilator associated pneumonia, and another one, acute myocardial infarction, both of them, in the context of major GI bleeding.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of patient selection.

Table 1.

Descriptive analysis of demographical data, clinical findings, type of intervention and outcome by type of bleeding, n (%)

|

Parameters

|

All cases, n = 363 (%)

|

Variceal bleeding, n = 127 (34%)

|

Non-variceal bleeding, n = 236 (65%)

|

P value

|

| Demographical data | ||||

| Age, yr; median/interval | 60.90; 61/19-93 | 57.24; 57.50/19-88 | 62.87; 63/21-93 | 0.001 |

| > 60 yr | 201 (55.4) | 56 (44.1) | 145 (61.4) | 0.002 |

| Male | 240 (66.1) | 85 (66.9) | 155 (65.7) | 0.810 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Heart failure | 75 (20.7) | 9 (7.1) | 66 (28.0) | 0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 52 (14.3) | 8 (6.3) | 44 (18.6) | 0.001 |

| Arterial hypertension | 119 (32.8) | 22 (17.3) | 97 (41.1) | 0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 61 (16.8) | 4 (3.1) | 57 (24.2) | 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 49 (13.5) | 18 (14.2) | 31 (13.1) | 0.783 |

| COPD | 9 (2.5) | 1 (0.8) | 8 (3.4) | 0.096 |

| Asthma | 3 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.3) | 0.107 |

| Kidney disease | 30 (8.3) | 2 (1.6) | 28 (11.9) | 0.001 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 139 (38.3) | 99 (78.0) | 40 (16.9) | 0.001 |

| Active malignancy | 25 (6.9) | 12 (9.4) | 13 (5.5) | 0.166 |

| Hepatocarcinoma | 9 (2.5) | 8 (6.2) | 1 (0.5) | |

| Cerebral vascular disease | 24 (6.6) | 2 (1.6) | 22 (9.3) | 0.002 |

| Symptoms | ||||

| Haematemesis | 279 (76.9) | 115 (90.6) | 164 (69.5) | 0.001 |

| Melena | 267 (73.6) | 89 (70.1) | 178 (75.4) | 0.274 |

| Abdominal pain | 60 (16.5) | 19 (15.0) | 41 (17.4) | 0.553 |

| Syncope | 12 (3.3) | 2 (1.6) | 10 (4.2) | 0.151 |

| Presyncope | 8 (2.2) | 2 (1.6) | 6 (2.5) | 0.539 |

| Other symptoms | 36 (9.9) | 12 (9.4) | 24 (10.2) | 0.826 |

| Chronic treatment | ||||

| Antiplatelets | 36 (9.9) | 0.002 | ||

| Aspirin | 22 (6.1) | 1 (0.8) | 21 (8.9) | |

| Clopidogrel | 7 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 7 (3.0) | |

| DAPT (aspirin clopidogrel or aspirin ticagrelor) | 6 (1.7) | 1 (0.8) | 5 (2.1) | |

| Ticagrelor | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | |

| No treatment | 327 (90.1) | 125 (98.4) | 202 (85.6) | |

| Anticoagulation | 32 (8.9) | 0.003 | ||

| DOAC | 22 (6.1) | 0 (0) | 22 (9.3) | |

| VKA | 10 (2.8) | 3 (2.4) | 7 (3.0) | |

| No treatment | 331 (91.2) | 124 (97.6) | 207 (87.7) | |

| Source of GI bleeding | ||||

| Ulcerative and erosive lesions | 25 (6.9) | 0 (0) | 25 (10.6) | 0.001 |

| Severe/erosive esophagitis | 27 (7.4) | 0 (0) | 27 (11.4) | |

| Severe/erosive gastritis/duodenitis | 151 (41.6) | 0 (0) | 151 (64) | |

| Vascular lesions (angiodysplasia) | 6 (1.7) | 0 (0) | 6 (2.5) | |

| Mass lesions | 12 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 12 (5) | |

| Traumatic lesions (Mallory Weiss tear) | 9 (2.4) | 0 (0) | 9 (3.8) | |

| Lesion unidentified/Dieulafoy | 6 (1.6) | 0 (0) | 6 (2.7) | |

| Oesophageal varices | 115 (31.7) | 115 (90.5) | 0 (0) | 0.003 |

| Gastric varices | 12 (3.3) | 12 (9.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Intervention | ||||

| Injection therapy (dilute epinephrine) with thermal coagulation | 29 (8.0) | 0 (0.0) | 28 (11.9) | 0.001 |

| Mechanical endoscopic therapy | 59 (16.3) | 50 (39.4) | 9 (3.8) | 0.001 |

| Haemostatic clip | 9 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 9 (3.8) | |

| Variceal ligation | 48 (13.2) | 48 (37.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Variceal sclerotherapy | 2 (0.6) | 2 (1.6) | 0 (0) | |

| Failed endoscopic therapy | 17 (4.7) | 9 (7) | 8 (3.4) | 0.001 |

| Surgical interventions | 9 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 9 (3.8) | 0.026 |

| Transfusion | ||||

| Transfusions | 112 (30.9) | 38 (29.9) | 74 (31.5) | 0.758 |

| In-hospital mortality | ||||

| Death | 34 (9.4) | 16 (12.6) | 18 (7.7) | 0.131 |

COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DAPT: Dual antiplatelets treatment DOAC: Direct oral anticoagulation VKA: Vitamin K antagonist GI: Gastrointestinal.

GBS had the highest mean value in the mixed population (12.32), as well as in the two main study groups (12.98 in variceal bleeding and 11.97 in non-variceal bleeding), most patients being at high risk of intervention. ABC score (mean value 5.02) and AIMS65 (mean value 1.52) showed a medium risk of mortality rate. Mean PERS is consistent with an 11% chance of mortality prior to endoscopy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean values of scores in variceal and non-variceal bleed

|

Scores

|

All cases, n = 363, mean

|

Variceal bleeding, n = 127, mean (SD)

|

Non-variceal bleeding, n = 236, mean (SD)

|

P value

|

| AIMS-65 | 1.52 | 1.74 (0.95) | 1.40 (1.05) | 0.003 |

| PERS | 3.30 | 3.76 (1.35) | 3.06 (1.70) | 0.001 |

| ABC | 5.02 | 5.83 (2.42) | 4.59 (2.51) | 0.001 |

| GBS | 12.32 | 12.98 (2.90) | 11.97 (3.74) | 0.008 |

AIMS65: Age older than 65; PERS: Pre-endoscopic Rockall score; ABC: Age, blood tests and comorbidities; GBS: Glasgow-Blatchford score.

We have performed linear regression analysis of each pre-endoscopic score against each determined outcome. AIMS65 score is influenced by the following variables: mortality, endoscopic and surgical intervention (Model 4: r = 0.316; P = 0.007), as well as length of stay, with an Y point 3.959-0.961 Death-0.148 Endoscopy + 0.057 Surgery -0.291 d (Table 3). PERS score is influenced by mortality and endoscopic intervention (Model 2: r = 0.243; P = 0.009), with an Y point 6.227-1.961 Death-0.512 Endoscopy (Table 4). ABC score is influenced by mortality and endoscopic intervention (Model 2: r = 0.324; P = 0.006), with an Y point 11.161-2.466 Death-0.815 Endoscopy (Table 5). GBS score is influenced by mortality and endoscopic intervention (Model 2: r = 0.241; P = 0.007), with an Y point 18.557-2.231 Death-1.127 Endoscopy (Table 6).

Table 3.

Linear regression analysis of age older than 65 score against each determined outcome

| Model | R | R square | Adjusted R square | Std. error of the estimate |

Change statistics

|

||||

|

R square change

|

F change

|

df1

|

df2

|

Sig. F change

|

|||||

| 1 | 0.261 (a) | 0.068 | 0.065 | 0.994 | 0.068 | 260.305 | 1 | 361 | 0.000 |

| 2 | 0.281 (b) | 0.079 | 0.074 | 0.989 | 0.011 | 40.320 | 1 | 360 | 0.038 |

| 3 | 0.286 (c) | 0.082 | 0.074 | 0.989 | 0.003 | 10.010 | 1 | 359 | 0.316 |

| 4 | 0.316 (d) | 0.100 | 0.090 | 0.981 | 0.018 | 70.290 | 1 | 358 | 0.007 |

Table 4.

Linear regression analysis of pre-endoscopic Rockall score against each determined outcome

| Model | R | R square | Adjusted R square | Std. error of the estimate |

Change statistics

|

||||

|

R square change

|

F change

|

df1

|

df2

|

Sig. F change

|

|||||

| 1 | 0.202 (a) | 0.041 | 0.038 | 10.588 | 0.041 | 150.411 | 1 | 361 | 0.000 |

| 2 | 0.243 (b) | 0.059 | 0.054 | 10.575 | 0.018 | 60.987 | 1 | 360 | 0.009 |

| 3 | 0.248 (c) | 0.062 | 0.054 | 10.575 | 0.002 | 0.941 | 1 | 359 | 0.333 |

| 4 | 0.260 (d) | 0.068 | 0.057 | 10.572 | 0.006 | 20.359 | 1 | 358 | 0.125 |

Table 5.

Linear regression analysis of age, blood tests and comorbidities score against each determined outcome

| Model | R | R square | Adjusted R square | Std. error of the estimate |

Change statistics

|

||||

|

R square change

|

F change

|

df1

|

df2

|

Sig. F change

|

|||||

| 1 | 0.294 (a) | 0.087 | 0.084 | 20.435 | 0.087 | 340.206 | 1 | 361 | 0.000 |

| 2 | 0.324 (b) | 0.105 | 0.100 | 20.413 | 0.019 | 70.543 | 1 | 360 | 0.006 |

| 3 | 0.329 (c) | 0.108 | 0.101 | 20.413 | 0.003 | 10.241 | 1 | 359 | 0.266 |

| 4 | 0.334 (d) | 0.111 | 0.101 | 20.412 | 0.003 | 10.183 | 1 | 358 | 0.277 |

Table 6.

Linear regression analysis of Glasgow-Blatchford score against each determined outcome

| Model | R | R square | Adjusted R square | Std. error of the estimate |

Change statistics

|

||||

|

R square change

|

F change

|

df1

|

df2

|

Sig. F change

|

|||||

| 1 | 0.198 (a) | 0.039 | 0.036 | 30.434 | 0.039 | 140.659 | 1 | 361 | 0.000 |

| 2 | 0.241 (b) | 0.058 | 0.053 | 30.405 | 0.019 | 70.250 | 1 | 360 | 0.007 |

| 3 | 0.256 (c) | 0.065 | 0.058 | 30.396 | 0.007 | 20.873 | 1 | 359 | 0.091 |

| 4 | 0.273 (d) | 0.075 | 0.064 | 30.384 | 0.009 | 30.534 | 1 | 358 | 0.061 |

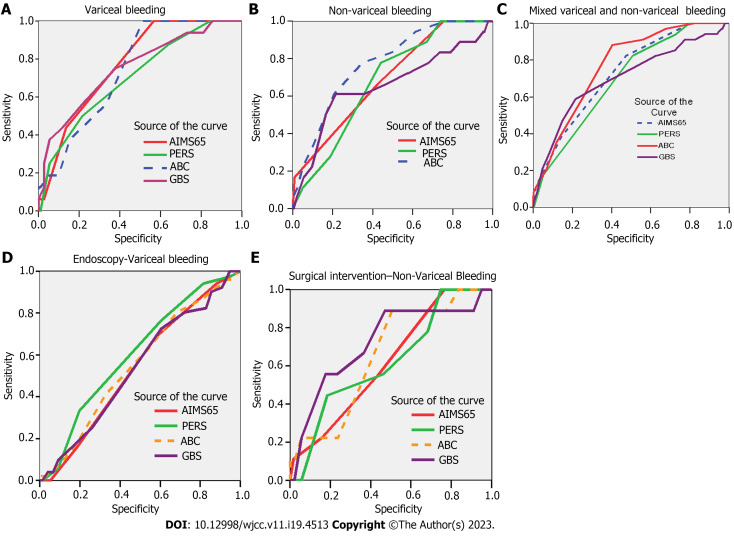

In-hospital mortality

All scores had discriminative ability in predicting in-hospital mortality irrespective of study group (AUROC > 0.600). AIMS-65 score had the best performance for the variceal bleeding group (AUROC 0.772; P < 0.001) (Figure 2A, Table 7), and ABC (AUROC 0.775; P < 0.001) in the non-variceal bleed (Figure 2B, Table 7).

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristics curve of age older than 65, pre-endoscopic Rockall score, age, blood tests and comorbidities, and Glasgow-Blatchford score predictors of in-hospital mortality. A: Variceal bleed; B: Non-variceal bleed; C: Mixed variceal and non-variceal bleeding population; D: Variceal bleeding group; E: Non-variceal bleeding group.

Table 7.

Analysis of area under the receiver operating characteristics curve, cut-off value, 95% confidence interval for in-hospital mortality

|

Test result variable

|

Area

|

Cut off

|

Std. error(a)

|

Asymptotic Sig.(b)

|

Asymptotic 95% confidence interval

|

| Variceal bleed | |||||

| AIMS-65 | 0.772 | 1.0 | 0.051 | 0.001 | 0.673-0.871 |

| PERS | 0.705 | 3.5 | 0.067 | 0.008 | 0.573-0.837 |

| ABC | 0.744 | 5.5 | 0.052 | 0.002 | 0.642-0.845 |

| GBS | 0.752 | 10.5 | 0.067 | 0.001 | 0.621-0.883 |

| Non-variceal bleed | |||||

| AIMS-65 | 0.693 | 1.5 | 0.059 | 0.006 | 0.577-0.810 |

| PERS | 0.680 | 3.5 | 0.053 | 0.011 | 0.576-0.785 |

| ABC | 0.775 | 5.5 | 0.051 | 0.001 | 0.675-0.874 |

| GBS | 0.657 | 12.5 | 0.077 | 0.027 | 0.505-0.808 |

AIMS65: Age older than 65; PERS: Pre-endoscopic Rockall score; ABC: Age, blood tests and comorbidities; GBS: Glasgow-Blatchford score.

The optimal cut-off value for predicting in-hospital mortality was calculated for each score depending on the type of bleeding. For variceal bleeding, an AIMS 65 score above 1 with sensitivity of 90% and specificity of 73% (AUC = 0.772; 95%CI: 0.673-0.871; P = 0.001) and GBS score above 10.5 with a sensitivity of 93.8% and specificity of 81% (AUC = 0.752; 95%CI: 0.621-0.883; P = 0.001). PERS and ABC scores had similar cut-off values, of 3.5 and 5.5, respectively, irrespective of type of bleeding, but with slight variations in sensitivity (PERS: 87.5% variceal group, 77.8% non-variceal group; ABC: 80% variceal group, 77.8% non-variceal group) and specificity (PERS: 64% variceal group, 56% non-variceal group; ABC: 76.7% variceal group, 65.1% non-variceal group). In the non-variceal bleeding group, the optimal cut-off value for in-hospital mortality was 1.5 for AIMS65 score, with sensitivity of 66.7% and specificity of 57% (AUC = 0.693; 95%CI: 0.577-0.810; P = 0.006), and 12.5 for GBS score with sensitivity of 66.7% and specificity de 52.8% (AUC = 0.657; 95%CI: 0.505-0.808; P = 0.027) (Table 7).

We have determined the best scoring system for in-patient mortality in the included population for both variceal and non-variceal bleeding. ABC showed the highest AUROC, 0.770 (Figure 2C), as being the best predictor for in-patient mortality in the entire population, at a cut-off value of 5.5 with a sensitivity of 88.2% and a specificity of 59.6% (95%CI: 0.700-0.840; P = 0.001) (Table 8).

Table 8.

Analysis of area under the receiver operating characteristics curve, cut-off value, 95% confidence interval for in-patient mortality in mixed variceal and non-variceal bleeding population

|

Scores

|

Cut off

|

Sensitivity

|

Specificity

|

Area

|

Std. error

|

Asymptotic Sig.

|

Asymptotic 95% confidence interval

|

| AIMS-65 | 1.50 | 82.4 | 52.6 | 0.730 | 0.041 | 0.001 | 0.650-0.809 |

| PERS | 3.50 | 82.4 | 49.2 | 0.696 | 0.042 | 0.001 | 0.615-0.778 |

| ABC | 5.50 | 88.2 | 59.6 | 0.770 | 0.036 | 0.001 | 0.700-0.840 |

| GBS | 12.50 | 76.5 | 47.7 | 0.704 | 0.052 | 0.001 | 0.602-0.805 |

AIMS65: Age older than 65; PERS: Pre-endoscopic Rockall score; ABC: Age, blood tests and comorbidities; GBS: Glasgow-Blatchford score.

Type of intervention

Endoscopic intervention: For variceal bleeding patients, only PERS score, at a cut-off value above 3.5 was a good predictor for endoscopic treatment with a sensitivity of 76.5% and specificity of 40% (AUC = 0.604; 95%CI: 0.506-0.703; P = 0.046) (Figure 2D). No score performed as a good predictor for endoscopic intervention in non-variceal bleeding group (Table 9).

Table 9.

Analysis of area under the receiver operating characteristics curve, cut-off value, 95% confidence interval for intervention

|

Test result variable

|

Area

|

Cut off

|

Std. error(a)

|

Asymptotic Sig.(b)

|

Asymptotic 95% confidence interval

|

| Endoscopy-variceal bleed | |||||

| AIMS-65 | 0.538 | 0.051 | 0.470 | 0.437-0.638 | |

| PERS | 0.604 | 3.5 | 0.050 | 0.046 | 0.506-0.703 |

| ABC | 0.553 | 0.052 | 0.313 | 0.452-0.654 | |

| GBS | 0.538 | 0.052 | 0.468 | 0.437-0.639 | |

| Surgical intervention-non-variceal bleed | |||||

| AIMS-65 | 0.621 | 1.5 | 0.081 | 0.218 | 0.461-0.781 |

| PERS | 0.624 | 3.5 | 0.088 | 0.208 | 0.451-0.796 |

| ABC | 0.657 | 5.5 | 0.079 | 0.111 | 0.502-0.811 |

| GBS | 0.722 | 12.5 | 0.092 | 0.024 | 0.541-0.903 |

AIMS65: Age older than 65; PERS: Pre-endoscopic Rockall score; ABC: Age, blood tests and comorbidities; GBS: Glasgow-Blatchford score.

Surgical intervention: In the non-variceal bleeding group, all risk scores were good predictors for surgical intervention, with an AUROC > 0.600 (Figure 2E). However, only GBS score, at a cut-off value above 12.5 with a sensitivity of 66.7% and specificity of 52.8% (AUC = 0.722; 95%CI: 0.541-0.903; P = 0.024), had statistical significance (Table 9). No patient in the variceal bleeding group underwent surgical intervention.

Length of admission (> 7 d)

No score proved to be a good predictor for length of admission, due to their low AUROC < 600 (Table 10).

Table 10.

Analysis of area under the receiver operating characteristics curve, cut-off value, 95% confidence interval for length of admission (over 7 d)

|

Test result variable

|

Area

|

Std. error(a)

|

Asymptotic Sig.(b)

|

Asymptotic 95% confidence interval

|

| Variceal bleeding | ||||

| AIMS65 | 0.516 | 0.053 | 0.768 | 0.412-0.619 |

| PERS | 0.497 | 0.054 | 0.960 | 0.391-0.604 |

| ABC | 0.434 | 0.053 | 0.215 | 0.330-0.538 |

| GBS | 0.496 | 0.053 | 0.946 | 0.393-0.600 |

| Non-variceal bleeding | ||||

| AIMS65 | 0.587 | 0.037 | 0.024 | 0.514-0.660 |

| PERS | 0.557 | 0.038 | 0.139 | 0.482-0.631 |

| ABC | 0.550 | 0.039 | 0.194 | 0.473-0.627 |

| GBS | 0.566 | 0.038 | 0.084 | 0.491-0.641 |

AIMS65: Age older than 65; PERS: Pre-endoscopic Rockall score; ABC: Age, blood tests and comorbidities; GBS: Glasgow-Blatchford score.

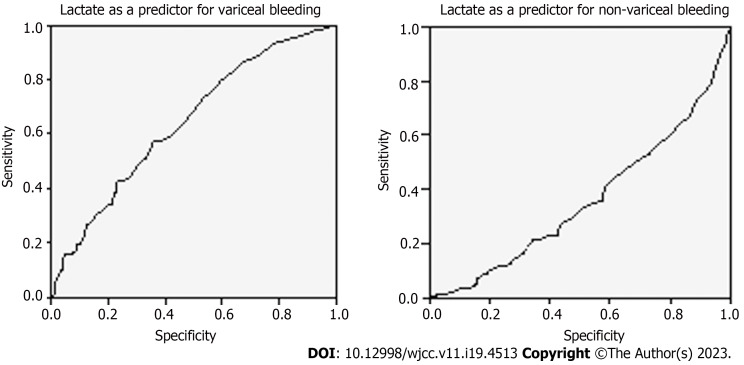

Role of venous lactate

Logistic regression model showed that lactate is an independent predictor for the determined outcomes. It did not show, however, good performance in predicting variceal or non-variceal bleeding, either due to low sensitivity (64.3%) and specificity (53.2%) or a low AUROC (0.357) (Figure 3, Table 11). For the variceal bleeding population, addition of lactate to AIMS65 score, leads to a 5-fold increase in probability of in-hospital mortality (P < 0.05). For non-variceal bleeding, addition of lactate to GBS score showed a 12-fold increase in probability of in-hospital mortality (P < 0.003). In terms of intervention, higher level of venous lactate increases by 5.5 times the probability of endoscopic intervention and by 2 the probability for surgical intervention (P = 0.001) (Table 12).

Figure 3.

Receiver operating characteristics curve. Lactate as a predictor for variceal bleed compared to non-variceal bleeding group.

Table 11.

Analysis of area under the receiver operating characteristics curve, cut-off value, 95% confidence interval of venous lactate in variceal and non-variceal bleed

|

Venous lactate

|

Cut off

|

Area

|

Std. error

|

Asymptotic Sig.

|

Asymptotic 95% confidence interval

|

| Variceal bleed | 2.05 | 0.643 | 0.030 | 0.001 | 0.585-0.701 |

| Non variceal bleed | 2.45 | 0.357 | 0.030 | 0.001 | 0.299-0.415 |

Table 12.

Logistic regression model for age older than 65, pre-endoscopic Rockall score, age, blood tests and comorbidities, Glasgow-Blatchford score and lactate

|

Logistic regression models

|

Independent variable

|

Odds ratio (95% confidence interval)

|

P value

|

| In-hospital mortality (Yes/No) | |||

| Adjusted model variceal bleed | AIMS-65 | 1.434 (1.202-1.930) | 0.032 |

| PERS | 1.028 (0.591-1.789) | 0.922 | |

| ABC | 0.799 (0.608-1.049) | 0.106 | |

| GBS | 0.915 (0.740-1.132) | 0.415 | |

| Venous lactate | 4.944 (2.207-11.008) | 0.001 | |

| Adjusted model, non-variceal bleed | AIMS-65 | 0.716 (0.374-1.372) | 0.314 |

| PERS | 0.965 (0.669-1.393) | 0.850 | |

| ABC | 0.824 (0.627-1.084) | 0.167 | |

| GBS | 1.159 (1.053-1.276) | 0.003 | |

| Venous lactate | 11.720 (3.437-39.968) | 0.001 | |

| Endoscopy (Yes/No) | |||

| Adjusted model variceal bleed | AIMS-65 | 1.049 (0.688-1.599) | 0.823 |

| PERS | 0.762 (0.544-1.067) | 0.113 | |

| ABC | 1.025 (0.850-1.236) | 0.794 | |

| GBS | 1.029 (0.905-1.171) | 0.659 | |

| Venous lactate | 2.222 (0.531-9.305) | 0.274 | |

| Adjusted model non variceal bleed | AIMS-65 | 0.860 (0.533-1.388) | 0.537 |

| PERS | 1.205 (0.904-1.604) | 0.203 | |

| ABC | 0.931 (0.743-1.166) | 0.533 | |

| GBS | 0.982 (0.891-1.083) | 0.721 | |

| Venous lactate | 5.550 (1.943-15.853) | 0.001 | |

| Surgical intervention (Yes/No) | |||

| Adjusted model non variceal bleed | AIMS-65 | 0.928 (0.533-1.388) | 0.870 |

| PERS | 0.870 (0.904-1.604) | 0.663 | |

| ABC | 1.255 (0.743-1.166) | 0.280 | |

| GBS | 1.214 (0.891-1.083) | 0.130 | |

| Venous lactate | 2.002 (1.002-2.047) | 0.001 | |

AIMS65: Age older than 65; PERS: Pre-endoscopic Rockall score; ABC: Age, blood tests and comorbidities; GBS: Glasgow-Blatchford score.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare four of the most representative pre-endoscopic risk scores, AIMS65, PERS, GBS and the relatively new ABC score in variceal and non-variceal GI bleeding cohort. Our aim was to identify which score would be preferably used depending on source of bleeding.

Prognostic risk scores could be a key step in the initial evaluation of upper GI bleeding patient in order to establish which one is at high risk of death. It should further identify likelihood of blood transfusion, endoscopic or surgical treatment, need for intensive care unit admission and cost of care in an attempt to decrease the burden over ED. Moreover, the routine determination of venous lactate should be used in determining probability of in-patient mortality, both as an independent predictor, and in association with certain risk scores.

Our cohort included a total of 363 patients, out of which 9.4% (n = 34) died, most of them (n = 16, 12.6%) in the variceal bleeding group. The mortality rate in our group is high, but similar to the one reported in other studies[14]. The pre-endoscopic risk scores should be considered as a key step to improve these numbers. When we analyzed the performance of risk scores according to in-patient mortality, ABC score had the best performance in both mixed and non-variceal bleeding group, with AIMS65 in variceal bleeding cohort. For endoscopic treatment, only PERS showed good discriminative value in the variceal bleeding group. In terms of surgical intervention, all determined scores had good performance, but only GBS had statistical significance. No score proved to be good in determining length of admission.

When comparing the two cohorts and their AUROC values, AIMS65 had the best accuracy in predicting in-patient mortality for patients with variceal bleeding. AIMS65 includes clinical parameters and regular laboratory tests which are fast and simple to be performed in ED settings. We determined an AUROC of 0.772 (95%CI: 0.673-0.871; P = 0.001), which was similar to other studies[15,16], but lower than other cohorts[10,17]. AIMS65 was also reported in other studies as the only score to provide accurate risk assessment for variceal GI bleeding population[18] in comparison to other scores, such as GBS or full Rockall (endoscopic) score. In our research, AIMS65 was superior to GBS, but the latter performed better than ABC or PERS score, which had the lowest AUROC, of 0.705. Previous reports compared both GBS and full Rockall score in predicting outcomes in patients with variceal bleeding, with similar results as ours[19]. The substrate for GBS inferiority in comparison to AIMS65, might be explained by the lack of liver disease history as some patients’ first presentation of liver cirrhosis is with variceal bleeding. Moreover, AIMS65 includes level of serum albumin and INR, which reflect liver function. Other reports comparing several different scores used in patients with liver cirrhosis (MELD-model for end-stage liver disease, APACHE II-acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II, qSOFA-quick sepsis related organ failure assessment) confirmed higher accuracy of AIMS65 in predicting in-hospital mortality[1]. Similar predictive power for in-hospital mortality of AIMS65 score, Child-Pugh score (CTP) and MELD score was found in a metanalysis performed on a variceal bleeding population[20].

The ABC score was recently validated to predict 30 d mortality in patients with both upper and lower GI bleeding. Based on patient’s age, kidney, and liver (albumin) function, and associated comorbidities, it can classify patients at low, medium, or high risk of mortality. Although there is limited literature data, the ABC score showed better performance when compared to AIMS65 and full Rockall score on a mixed population (variceal and non-variceal) GI bleeding[9,21]. Interestingly, in our study, the score had the highest performance (AUROC 0.770) in predicting in-patient mortality in the entire population (variceal and non-variceal), as well as non-variceal bleeding when compared to AIMS65, PERS and GBS. This is particularly important as no previous investigations compared the scores’ ability to predict mortality by type of GI bleeding (variceal vs non-variceal). Our findings also support previous evidence that ABC performs better than GBS or AIMS65 score[22], also outperforming Progetto Nazionale Emorragia Digestive (PNED) and Rockall score[23]. Looking at the other three scores, our results show that AIMS65 is superior to GBS and PERS, but with no significant difference in the AUROC value. In non-variceal upper GI bleeding, other investigators support a better predictive power for AIMS65 when compared to other scores[24]. In contrast, GBS and PERS are the most widely used pre-endoscopic scoring system in clinical practice, with most studies in non-variceal upper GI bleeding cohorts. GBS has been previously reported to perform less than PERS in predicting mortality[25,26], similar to our cohort, where GBS had the lowest AUROC of 0.657. However, for practical reasons, we consider that ABC score, at a cut-off value of 5.5 can be used to determine in-hospital mortality in both populations.

The cut-off value of each score was determined as it is a key determinant in predicting outcomes. There are significant variations among different studies, probably due to population characteristics, moment, and type of therapeutic interventions[27]. For in-hospital mortality, we determined a cut-off value of 1 for AIMS65 score in patients with variceal bleeding. This should label the patients as high category of emergency and limit the waiting time until assessment as much as possible. Cut-off values of 1[27], 2[24], or 3[28] were previously reported in different populations, with similar results for European cohorts. For those presenting with non-variceal upper GI bleed, an ABC score of 5.5 classifies them as high risk. Similar to our findings, another study reported a cut-off value of 5.5 for ABC score in predicting 30-d mortality[29] associated with a 13.1% risk of mortality.

Regarding endoscopic intervention, no score performed as a good predictor in the non-variceal bleeding group, due to an AUROC < 0.600. This is consistent with previous reports where AUROC levels were around 0.500[30], but other investigators showed better performance (AUROC 0.750, sensitivity 80.4%, specificity 57.4%)[31]. We found that PERS score, at a cut-off value above 3.5 showed good performance for predicting endoscopic treatment in variceal bleeding patients, with a sensitivity of 76.5% and specificity of 40%, and a relatively low AUROC (AUC = 0.604; 95%CI: 0.506-0.703; P = 0.046). Rockall score can be calculated after endoscopy (full Rockall), or prior to it (PERS). The pre-endoscopic score relies on vital signs, patient’s age and comorbidities and it was previously validated to predict in-patient mortality. On the other hand, the full Rockall score can be used as a predictor of endoscopic treatment at a cut-off value > 3.5[32]. This is particularly important as the latter score includes endoscopic findings which plays a major role in the diagnosis and treatment of such patients. All patients included in our cohort have been investigated endoscopically within the first 24 h of presentation. As previously mentioned, timing of endoscopy is of paramount importance in patients with high risk of further bleeding and mortality and it should be performed within 12 h, especially in patients with variceal bleed. On the other hand, very early endoscopy (less than 6 h) does not appear to reduce mortality or further risk of bleeding[33].

Although our AUROC values were low, we agree with most previously reported data which showed better performance of GBS in predicting endoscopic intervention in patients with GI bleeding[20]. We did not find any study to evaluate the ABC score against this outcome. Further larger studies may be needed.

Nowadays, less surgical interventions are performed in upper GI bleeding, mainly due to advances in types of endoscopic treatment and interventional radiology. All patients requiring surgical intervention in our population (n = 9) are in the non-variceal group. The main reason is failure of endoscopic treatment and lack of availability of endovascular therapies. All scores showed good predictive value for surgical intervention with an AUROC > 600. Our study is the first to compare such outcome for all investigated scores. However, only GBS score, at a cut-off value above 12.5 with a sensitivity of 66.7% and specificity of 52.8% had statistical significance. GBS has been validated to be a good predictor for need of treatment, which consisted of either endoscopy, surgery or interventional radiology[34].

No risk score proved to be a good predictor for length of stay (> 7 d) as it had poor statistic power, with an AUROC below 0.600. Similar low discriminative abilities were previously reported for PNED, full and PERS, GBS and AIMS65 score, with an AUROC close to 0.600[15].

Lactate is an independent predictor for in-hospital mortality, need for intensive care unit admission, recurrence of bleeding or need for surgical intervention[12,13]. We are of the opinion that lactate could be implemented as a standard test in all patients with upper GI bleeding. In variceal bleeding patients, levels of lactate might be higher due to associated liver insufficiency, large volume of bleeding and subsequent hypovolemia[13,35]. On the other hand, in patients with less dramatic clinical presentation, lactate could be used as a tool for early detection of GI bleeding[36,37]. In our cohort it was an independent predictor of mortality and intervention (endoscopy and surgery). There is, however, disparity among studies evaluating role of lactate in addition to risk scores. It seems that incorporation of arterial lactate in PERS and GBS showed a statistically significant improvement in their ability to predict mortality, but with a low AUROC[38]. In contrast, when taking into account venous lactate level, the power of discrimination for GBS and PERS for in-patient mortality showed better performance and an AUROC > 700. The difference between levels of arterial and venous lactate (which has higher levels) might be a determinant factor for study results variability[39]. In our population, addition of lactate to GBS score showed a 12-fold increase in probability of in-hospital mortality (P < 0.003), but this only applies to the non-variceal bleeding group. In case of patients presenting with variceal upper GI bleeding, addition of lactate to AIMS65 score, leads to a 5-fold increase in determining the probability of in-hospital mortality (P < 0.05). Similar findings are supported by another retrospective study where the modified L-AIMS65 score (AIMS65 combining lactate) had higher AUC for rate of rebleeding and 30 days mortality. Unfortunately, it did not show statistical significance[40].

In terms of type of intervention, adding lactate to the regression model of non-variceal bleeding population does not improve the prediction value of any of the determined scores.

There are several limitations of our study. It is a single center, retrospective analysis based on clinical records data which may lead to selection bias. The decision of intervention was based on the clinical judgement of emergency medicine physician. Hospital admission was indicated by the gastroenterologist and surgeon on call. We excluded a large number of patients, mainly due to lack of availability in albumin and venous lactate level. Also, irrespective of their statistical power, risk scores are tools which cannot replace appropriate clinical evaluation, decision making process and the need for an individualized approach of each patient.

CONCLUSION

ABC score is the most accurate in predicting in-hospital mortality in both mixed and non-variceal bleeding population. AIMS65 had the best performance in predicting in-patient mortality in patients with variceal upper GI bleeding, however, for practicality, we advise the use of ABC score for both populations. In terms of intervention, PERS and GBS should be used to determine need for endoscopic and surgical intervention. Lactate can be used in conjunction to AIMS65 and GBS score to predict in-patient mortality and intervention. Although GBS is currently largely used, further studies are needed to investigate the relatively new ABC score regarding its role in daily clinical practice and possible implementation in guidelines.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding patients require immediate assessment at the time of arrival in the emergency department (ED). A comprehensive, however fast approach regarding haemodynamic status, transfusion strategy and need for intervention should be performed. This can be achieved by calculating GI bleeding risk scores which should be able to predict several outcomes such as need for intervention, mortality, rebleeding rate or death. Pre-endoscopy risk scores have proved to be a reliable tool which may allow timely sequential decisions. Glasgow-Blatchford score (GBS) has been validated to identify low risk patients which may be managed as outpatients. Pre-endoscopic Rockall score (PERS) evaluates the risk of rebleeding and mortality, while albumin, international normalized ratio, altered mental status, systolic blood pressure, age older than 65 (AIMS65), determines the risk of death. Age, blood tests and comorbidities (ABC) is a relatively new risk score used to predict mortality in patients with both upper and lower GI bleeding. There is a certain variability among these risk scores, potentially due to the differences in population included. Moreover, there is limited data for variceal upper GI bleeding. Venous lactate is another important tool in critically ill patients, such as those with shock, trauma, or heart failure. It has been shown to predict in-hospital mortality, need for intensive care or surgical intervention, as well as rebleeding rate in patients with upper GI bleed. It may be used to improve performance of existing scoring systems and guide clinicians towards early triage of patients.

Research motivation

As emergency services are struggling with high patient flow, clinicians must promptly decide appropriate management in patients with upper GI bleeding. A standardized approach and protocols should attempt to quickly assess the need for admission, timing of endoscopy and level of care. It is generally recommended to perform endoscopy within 24 h of presentation as it plays a pivotal role in identifying the source of bleeding and it can achieve haemostasis in most cases. Unfortunately, it may not be available in all centers or, if performed in low-risk patients, it may overcrowd the service with unnecessary urgent interventions. Hence, we need a standardized tool to guide the emergency medicine clinician for appropriate referral and management of patients. This should reduce the burden and costs on the healthcare system and on-call physicians.

Research objectives

To evaluate the performance of pre-endoscopic risk scores (GBS, PERS, AIMS65, and ABC) in patients with variceal and non-variceal upper GI bleeding for predicting the following primary outcomes: In-hospital mortality, type of intervention (endoscopic or surgical) and length of admission (≥ 7 d). We will further evaluate whether the addition of venous lactate improves the score performance in predicting the determined outcomes.

Research methods

We retrospectively analyzed all patients above 18 years old presenting to the emergency department (ED) with upper GI bleeding from January 2020 to December 2021. Each patient presenting with exteriorized upper GI bleeding was fully assessed by the emergency medicine physician. Immediate venous catheterization and fluid resuscitation was performed and full work-up with blood tests (full blood count, coagulation parameters, liver, kidney function, venous lactate), and other investigations were performed within 24 h from presentation. Patients with a Hb ≤ 7 g/dL had at least one unit of red blood cell concentrate transfused, with a higher Hb threshold (Hb ≤ 8 g/dL) for patients with associated cardiovascular disease. Post-transfusion target Hb was between 7-9 g/dL. Endoscopy was performed within 24 h of ED arrival in all patients included in analysis. Forrest classification was used to describe peptic ulcer disease, with Baveno and Sarin’s classification for gastroesophageal varices. Patients with non-variceal upper GI bleeding received an infusion with PPIs, while those with variceal bleeding were treated with Somatostatin. Endoscopic treatment was performed depending on the cause of bleeding. A combined approach with injection therapy (dilute epinephrine) and mechanic therapy (thermal coagulation or haemostatic clip) was used for FIa, FIb, and FIIa, with clot removal in FIIb lesions. In variceal bleeding, endoscopic ligation was the main approach. Surgical treatment was performed in cases where endoscopic treatment failed. The need for admission was established by the gastroenterology and general surgery teams on-call.

Research results

The final study included 363 patients with upper GI bleeding with a mean age of 60 years old and a predominance of male sex. Non-variceal bleeding was the main cause of presentation, liver cirrhosis the most frequently associated comorbidity in the entire group. The main symptom of presentation was haematemesis in patients with variceal bleeding and melena in the non-variceal group. Approximately 9% of our patients had chronic treatment with antiplatelets or oral anticoagulation. Gastric/duodenal ulcer was the main cause of GI bleeding. Most patients in variceal bleeding group required mechanical endoscopic therapy with band ligation and only 2 patients had variceal sclerotherapy. In the non-variceal bleeding group, dual therapy with thermal anticoagulation and local administration of dilute Adrenaline was the main type of endoscopic intervention. Failed endoscopy was recorded in approximately 4.7% of patients. Only 9 patients in the non-variceal group required surgical intervention. In-hospital mortality had an overall rate of 9.4%, most cases were in the variceal group. All scores had discriminative ability in predicting in-hospital mortality irrespective of study group. AIMS65 score had the best performance for the variceal bleeding group and ABC in the non-variceal bleed. The optimal cut-off value for predicting in-hospital mortality was calculated for each score depending on the type of bleeding. For variceal bleeding, an AIMS65 score above 1 with sensitivity of 90% and specificity of 73% and ABC score with a cut-off value of 5.5 and specificity. In the non-variceal bleeding group, the optimal cut-off value for in-hospital mortality was 1.5 for AIMS65 score, with sensitivity of 66.7% and specificity of 57%. We have determined the best scoring system for in-hospital mortality in the included population, both variceal and non-variceal bleeding, with ABC being the best predictor. For variceal bleeding patients, only PERS score, at a cut-off value above 3.5 was a good predictor for endoscopic treatment with a sensitivity of 76.5% and specificity of 40%. Venous lactate did not show good performance in predicting variceal bleeding, due to low sensitivity (64.3%) and specificity (53.2%). However, logistic regression model showed it is an independent predictor for the determined outcomes. For the variceal bleeding population, addition of lactate to AIMS65 score, leads to a 5-fold increase in probability of in-hospital mortality. For non-variceal bleeding, addition of lactate to GBS score showed a 12-fold increase in probability of in-hospital mortality. In terms of intervention, higher level of venous lactate increases by 5.5 times the probability of endoscopic intervention and by 2 the probability for surgical intervention.

Research conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare four of the most representative pre-endoscopic risk scores, AIMS65, PERS, GBS and the relatively new ABC score in variceal and non-variceal GI bleeding cohort. ABC score is the most accurate in predicting in-hospital mortality in both mixed and non-variceal bleeding population. AIMS65 had the best performance in predicting in-hospital mortality in patients with variceal upper GI bleeding, however, for practicality, we advise the use of ABC score for both populations. In terms of intervention, PERS and GBS should be used to determine the need for endoscopic and surgical intervention. Lactate can be used in conjunction to AIMS65 and GBS score to predict in-hospital mortality and intervention.

Research perspectives

Although GBS is currently largely used, further studies are needed to investigate the relatively new ABC score regarding its role in daily clinical practice and possible implementation in guidelines.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the ‘’Saint Spiridon’’ Institutional Review Board approved this study (approval No. 39/30.03.2022).

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

STROBE statement: The authors have read the STROBE Statement—checklist of items, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the STROBE Statement—checklist of items.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: March 28, 2023

First decision: April 26, 2023

Article in press: May 30, 2023

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Romania

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D, D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Losurdo G, Italy; Skok P, Slovenia; Treeprasertsuk S, Thailand S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Cai YX

Contributor Information

Bianca Codrina Morarasu, Department of Internal Medicine and Toxicology, Saint Spiridon University Regional Emergency Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, “Grigore T. Popa” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Iasi 700111, Romania.

Victorita Sorodoc, Department of Internal Medicine and Toxicology, Saint Spiridon University Regional Emergency Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, “Grigore T. Popa” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Iasi 700111, Romania. victorita.sorodoc@umfiasi.ro.

Anca Haisan, Department of Emergency Medicine, Saint Spiridon University Regional Emergency Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, “Grigore T. Popa” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Iasi 700111, Romania.

Stefan Morarasu, Second Department of Surgical Oncology, Regional Institute of Oncology, Faculty of Medicine, “Grigore T. Popa” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Iasi 700111, Romania.

Cristina Bologa, Department of Internal Medicine and Toxicology, Saint Spiridon University Regional Emergency Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, “Grigore T. Popa” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Iasi 700111, Romania.

Raluca Ecaterina Haliga, Department of Internal Medicine and Toxicology, Saint Spiridon University Regional Emergency Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, “Grigore T. Popa” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Iasi 700111, Romania.

Catalina Lionte, Department of Internal Medicine and Toxicology, Saint Spiridon University Regional Emergency Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, “Grigore T. Popa” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Iasi 700111, Romania.

Emilia Adriana Marciuc, Department of Radiology, Emergency Hospital “Prof. Dr. N. Oblu”, Faculty of Medicine, “Grigore T. Popa” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Iasi 700309, Romania.

Mohammed Elsiddig, Department of Gatroenterology, Beaumont Hospital, Dublin D09V2N0, Ireland.

Diana Cimpoesu, Department of Emergency Medicine, Saint Spiridon University Regional Emergency Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, “Grigore T. Popa” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Iasi 700111, Romania.

Gabriel Mihail Dimofte, Second Department of Surgical Oncology, Regional Institute of Oncology, Faculty of Medicine, “Grigore T. Popa” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Iasi 700111, Romania.

Laurentiu Sorodoc, Department of Internal Medicine and Toxicology, Saint Spiridon University Regional Emergency Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, “Grigore T. Popa” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Iasi 700111, Romania.

Data sharing statement

Technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset available from the corresponding author at victorita.sorodoc@umfiasi.ro.

References

- 1.Lai YC, Hung MS, Chen YH, Chen YC. Comparing AIMS65 Score With MEWS, qSOFA Score, Glasgow-Blatchford Score, and Rockall Score for Predicting Clinical Outcomes in Cirrhotic Patients With Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. J Acute Med. 2018;8:154–167. doi: 10.6705/j.jacme.201812_8(4).0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hăisan A, Măirean C, Lupuşoru SI, Tărniceriu C, Cimpoeşu D. General Health among Eastern Romanian Emergency Medicine Personnel during the Russian-Ukrainian Armed Conflict. Healthcare (Basel) 2022;10 doi: 10.3390/healthcare10101976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stanley AJ, Ashley D, Dalton HR, Mowat C, Gaya DR, Thompson E, Warshow U, Groome M, Cahill A, Benson G, Blatchford O, Murray W. Outpatient management of patients with low-risk upper-gastrointestinal haemorrhage: multicentre validation and prospective evaluation. Lancet. 2009;373:42–47. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61769-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gralnek IM, Stanley AJ, Morris AJ, Camus M, Lau J, Lanas A, Laursen SB, Radaelli F, Papanikolaou IS, Cúrdia Gonçalves T, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Awadie H, Braun G, de Groot N, Udd M, Sanchez-Yague A, Neeman Z, van Hooft JE. Endoscopic diagnosis and management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage (NVUGIH): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline-Update 2021. Endoscopy. 2021;53:300–332. doi: 10.1055/a-1369-5274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stanley AJ, Dalton HR, Blatchford O, Ashley D, Mowat C, Cahill A, Gaya DR, Thompson E, Warshow U, Hare N, Groome M, Benson G, Murray W. Multicentre comparison of the Glasgow Blatchford and Rockall Scores in the prediction of clinical end-points after upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:470–475. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blatchford O, Murray WR, Blatchford M. A risk score to predict need for treatment for upper-gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Lancet. 2000;356:1318–1321. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02816-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Risk assessment after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Gut. 1996;38:316–321. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.3.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saltzman JR, Tabak YP, Hyett BH, Sun X, Travis AC, Johannes RS. A simple risk score accurately predicts in-hospital mortality, length of stay, and cost in acute upper GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1215–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laursen SB, Oakland K, Laine L, Bieber V, Marmo R, Redondo-Cerezo E, Dalton HR, Ngu J, Schultz M, Soncini M, Gralnek I, Jairath V, Murray IA, Stanley AJ. ABC score: a new risk score that accurately predicts mortality in acute upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding: an international multicentre study. Gut. 2021;70:707–716. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-320002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hyett BH, Abougergi MS, Charpentier JP, Kumar NL, Brozovic S, Claggett BL, Travis AC, Saltzman JR. The AIMS65 score compared with the Glasgow-Blatchford score in predicting outcomes in upper GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:551–557. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yaka E, Yılmaz S, Doğan NÖ, Pekdemir M. Comparison of the Glasgow-Blatchford and AIMS65 scoring systems for risk stratification in upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22:22–30. doi: 10.1111/acem.12554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strzałka M, Winiarski M, Dembiński M, Pędziwiatr M, Matyja A, Kukla M. Predictive Role of Admission Venous Lactate Level in Patients with Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: A Prospective Observational Study. J Clin Med. 2022;11 doi: 10.3390/jcm11020335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shah A, Chisolm-Straker M, Alexander A, Rattu M, Dikdan S, Manini AF. Prognostic use of lactate to predict inpatient mortality in acute gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:752–755. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imperiale TF, Dominitz JA, Provenzale DT, Boes LP, Rose CM, Bowers JC, Musick BS, Azzouz F, Perkins SM. Predicting poor outcome from acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1291–1296. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.12.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stanley AJ, Laine L, Dalton HR, Ngu JH, Schultz M, Abazi R, Zakko L, Thornton S, Wilkinson K, Khor CJ, Murray IA, Laursen SB International Gastrointestinal Bleeding Consortium. Comparison of risk scoring systems for patients presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding: international multicentre prospective study. BMJ. 2017;356:i6432. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i6432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robertson M, Majumdar A, Boyapati R, Chung W, Worland T, Terbah R, Wei J, Lontos S, Angus P, Vaughan R. Risk stratification in acute upper GI bleeding: comparison of the AIMS65 score with the Glasgow-Blatchford and Rockall scoring systems. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:1151–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abougergi MS, Charpentier JP, Bethea E, Rupawala A, Kheder J, Nompleggi D, Liang P, Travis AC, Saltzman JR. A Prospective, Multicenter Study of the AIMS65 Score Compared With the Glasgow-Blatchford Score in Predicting Upper Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage Outcomes. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50:464–469. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang A, Ouejiaraphant C, Akarapatima K, Rattanasupa A, Prachayakul V. Prospective Comparison of the AIMS65 Score, Glasgow-Blatchford Score, and Rockall Score for Predicting Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Variceal and Nonvariceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Clin Endosc. 2021;54:211–221. doi: 10.5946/ce.2020.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thanapirom K, Ridtitid W, Rerknimitr R, Thungsuk R, Noophun P, Wongjitrat C, Luangjaru S, Vedkijkul P, Lertkupinit C, Poonsab S, Ratanachu-ek T, Hansomburana P, Pornthisarn B, Thongbai T, Mahachai V, Treeprasertsuk S. Prospective comparison of three risk scoring systems in non-variceal and variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:761–767. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang L, Sun R, Wei N, Chen H. Systematic review and meta-analysis of risk scores in prediction for the clinical outcomes in patients with acute variceal bleeding. Ann Med. 2021;53:1806–1815. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2021.1990394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saade MC, Kerbage A, Jabak S, Makki M, Barada K, Shaib Y. Validation of the new ABC score for predicting 30-day mortality in gastrointestinal bleeding. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:301. doi: 10.1186/s12876-022-02374-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mules TC, Stedman C, Ding S, Burt M, Gearry R, Chalmers-Watson T, Falvey J, Barclay M, Lim G, Chapman B, Banerjee T, Ngu J. Comparison of Risk Scoring Systems in Hospitalised Patients who Develop Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Gastro Hep . 2021;3:5–11. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsai HH. Prognostic risk score for gastrointestinal bleeding: Which one is best? Gastro Hep. 2021;3:4. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gu L, Xu F, Yuan J. Comparison of AIMS65, Glasgow-Blatchford and Rockall scoring approaches in predicting the risk of in-hospital death among emergency hospitalized patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a retrospective observational study in Nanjing, China. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18:98. doi: 10.1186/s12876-018-0828-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu M, Sun G, Huang H, Zhang X, Xu Y, Chen S, Song Y, Li X, Lv B, Ren J, Chen X, Zhang H, Mo C, Wang Y, Yang Y. Comparison of the Glasgow-Blatchford and Rockall Scores for prediction of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding outcomes in Chinese patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e15716. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000015716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim MS, Choi J, Shin WC. AIMS65 scoring system is comparable to Glasgow-Blatchford score or Rockall score for prediction of clinical outcomes for non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19:136. doi: 10.1186/s12876-019-1051-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martínez-Cara JG, Jiménez-Rosales R, Úbeda-Muñoz M, de Hierro ML, de Teresa J, Redondo-Cerezo E. Comparison of AIMS65, Glasgow-Blatchford score, and Rockall score in a European series of patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding: performance when predicting in-hospital and delayed mortality. United European Gastroenterol J. 2016;4:371–379. doi: 10.1177/2050640615604779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen IC, Hung MS, Chiu TF, Chen JC, Hsiao CT. Risk scoring systems to predict need for clinical intervention for patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25:774–779. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2006.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeon HJ, Moon HS, Kwon IS, Kang SH, Sung JK, Jeong HY. Which scoring system should be used for non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36:2819–2827. doi: 10.1111/jgh.15555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park SM, Yeum SC, Kim BW, Kim JS, Kim JH, Sim EH, Ji JS, Choi H. Comparison of AIMS65 Score and Other Scoring Systems for Predicting Clinical Outcomes in Koreans with Nonvariceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Gut Liver. 2016;10:526–531. doi: 10.5009/gnl15153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tham J, Stanley A. Clinical utility of pre-endoscopy risk scores in upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;13:1161–1167. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2019.1698292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Custovic N, Husic-Selimovic A, Srsen N, Prohic D. Comparison of Glasgow-Blatchford Score and Rockall Score in Patients with Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Med Arch. 2020;74:270–274. doi: 10.5455/medarh.2020.74.270-274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lau JYW, Yu Y, Tang RSY, Chan HCH, Yip HC, Chan SM, Luk SWY, Wong SH, Lau LHS, Lui RN, Chan TT, Mak JWY, Chan FKL, Sung JJY. Timing of Endoscopy for Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1299–1308. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1912484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bryant RV, Kuo P, Williamson K, Yam C, Schoeman MN, Holloway RH, Nguyen NQ. Performance of the Glasgow-Blatchford score in predicting clinical outcomes and intervention in hospitalized patients with upper GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:576–583. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jeppesen JB, Mortensen C, Bendtsen F, Møller S. Lactate metabolism in chronic liver disease. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2013;73:293–299. doi: 10.3109/00365513.2013.773591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wada T, Hagiwara A, Uemura T, Yahagi N, Kimura A. Early lactate clearance for predicting active bleeding in critically ill patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a retrospective study. Intern Emerg Med. 2016;11:737–743. doi: 10.1007/s11739-016-1392-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gulen M, Satar S, Tas A, Avci A, Nazik H, Toptas Firat B. Lactate Level Predicts Mortality in Patients with Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2019;2019:5048078. doi: 10.1155/2019/5048078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stokbro LA, Schaffalitzky de Muckadell OB, Laursen SB. Arterial lactate does not predict outcome better than existing risk scores in upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:586–591. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2017.1397737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berger M, Divilov V, Teressa G. Lactic Acid Is an Independent Predictor of Mortality and Improves the Predictive Value of Existing Risk Scores in Patients Presenting With Acute Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Gastroenterology Res. 2019;12:1–7. doi: 10.14740/gr1085w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee SH, Min YW, Bae J, Lee H, Min BH, Lee JH, Rhee PL, Kim JJ. Lactate Parameters Predict Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Nonvariceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. J Korean Med Sci. 2017;32:1820–1827. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2017.32.11.1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset available from the corresponding author at victorita.sorodoc@umfiasi.ro.