Abstract

Objective:

To assess the association between financial toxicity and survival in patients with head and neck cancer (HNC).

Materials and Methods:

Using a single-institution database, we retrospectively reviewed HNC patients treated at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center treated with definitive or postoperative radiation therapy between 2013 and 2017. Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank tests were used to analyze survival outcomes. Propensity score matching on all clinically relevant baseline characteristics was performed to address selection bias. All statistical tests were two-sided and those less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results:

Of a total of 284 HNC patients (age: median 61 years, IQR 55-67; 220 [77.5%] men), 204 patients (71.8%) received definitive radiation and 80 patients (28.2%) received adjuvant radiation. There were 41 patients (14.4%) who reported high baseline financial toxicity. Chemotherapy was used in 237 patients (83.5%). On multivariable analysis, those with high financial toxicity exhibited worse overall survival (hazards ratio [HR] 1.75, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.05-2.94, p=0.03) and cancer specific survival (HR 2.28, 95% CI 1.31-3.96, p=0.003). Matched pair analysis of 66 patients, high financial toxicity remained associated with worse OS (HR 2.72, 95% CI 1.04-7.09, p=0.04) and CSS (HR 3.75, 95% CI 1.22-11.5, p=0.02).

Conclusion:

HNC patient reported baseline financial toxicity was significantly correlated with both decreased overall and cancer specific survival. These significant correlations held after match pairing. Further research is warranted to investigate the impact of financial toxicity in HNC and mitigate its risk.

Keywords: Financial support, Head and neck neoplasms, Oral cancer, Survival, Kaplan-Meier Analysis, Matched-pair analysis

Introduction

The second century physician Galen observed that cancer was a constitutional disease that more frequently afflicted those with a “melancholic” disposition.1 For the modern cancer patient, financial problems often exacerbate the “melancholy.” Broadly, those “problems a patient has related to the cost of medical care” are defined as financial toxicity (FT) by the National Cancer Institute; FT is also called: economic burden, economic hardship, financial burden, financial distress, financial hardship, and financial stress.2

Cancer patients are more likely to have more FT than patients without cancer.3 This is consistent with the fact that cancer treatments are the among the most expensive and have the highest out of pocket costs.4 Most of these costs relate to radiation and chemotherapy.5 A 2018 survey showed that patients are more worried about financial depletion and its impact than dying of cancer.6 Emotional distress from the diagnosis of cancer amplified by FT may impact the patient’s ability to cope with the physical and psychological of cancer therapy thus negatively impacting outcomes.7 In particular, medical expenses and out-of-pocket expenses were higher for head and neck cancer patients than other cancers.8 Head and neck cancer patients have been shown to be at risk for worsening quality of life due to FT,9 and more than 2 out of 3 such patients relied on cost-coping strategies, such as selling personal assets, using personal savings, taking credit card loans, and having family members work additional hours to relieve FT.10

Furthermore, extreme FT, manifested as bankruptcy, has been correlated with increased mortality in cancer survivors; the magnitude of the correlation varies by tumor type11. However, in those analyses the patient’s financial burden at baseline was unknown. There is limited data on the relationship baseline FT and overall survival (OS). To examine the relationship between baseline FT and OS, we performed an observational cohort study of head and neck cancer patients treated with definitive or post-operative radiation therapy, usually with chemotherapy.

Materials and Methods

Our retrospective database included all primary head and neck cancer patients treated at a single institution with definitive or post-operative radiation between January 1, 2013 and August 3, 2017. Upon completion of treatment, patients were seen in clinic for follow up every 3 months in year 1, every 2 months in year 2, and annually in year 3 and beyond. The database was constructed through a detailed medical chart review. All staging information is based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer, 7th edition. A total of 284 patients met the above criteria. The analysis occurred April 1st and June 9th, 2020. Our study was approved by the institutional review board. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines for cohort studies was followed.12

The cisplatin-based chemotherapy (weekly or every three weeks) and intensity modulated radiation therapy regimens (70 Gy to the primary tumor and 56 Gy to the elective lymph nodes in 35 fractions) applied in this cohort have been previously described in detail.13,14

At the beginning of their radiation course, all patients completed the EORTC QLQ 30 and HN 35 Questionnaires.15 The financial question was, “Has your physical condition or medical treatment caused you financial difficulties?” with answer choices ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (very much). Similar to a previous report, this variable was stratified by those who answered as 1 or 2 (low financial difficulty) and 3 or 4 (high financial difficulty) for analysis.15,16 If available, questionnaires were also collected at 3-months following the completion of treatment. Other extracted variables included gender, age, smoking history, histology, primary site, human papillomavirus (HPV) status, number of comorbidities, cancer staging, surgery, chemotherapy, radiation dose, hospitalization, hemoglobin level, and white blood cell count. Nutrition support was defined as the use of feeding tube.17 Age was stratified by its median value. White blood cell count was categorized based on our institutional normal range, 4-11x109/L. Hemoglobin was categorized based on 12 g/dL as a cutoff value.18,19 White blood cell count and hemoglobin levels were included since they were previously associated with clinical outcomes for head and neck cancer.17-19 Hospitalization was defined as inpatient admission during or within 90 days after completing radiation therapy.17 All missing values were coded as unknown for analysis.

Primary endpoints were overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS), defined as the duration of interval from diagnosis to any death or last follow up and cancer-related death, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Fisher exact test and Mann-Whitney U test were performed when comparing baseline characteristics. Chi-square was performed to compare differences in receiving salvage treatments. Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank tests were used to analyze survival outcomes. Cox proportional hazard univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to evaluate variables associated with survival outcomes. Assumptions of the Cox proportional hazard model were verified using the Schoenfeld residuals method. Final multivariate analysis model was constructed based on all statistically significant variables from the univariate analysis. All statistical tests were two-sided and those less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Propensity score matching was performed to address selection bias. Matching was based on nearest neighbor method in a 1:1 ratio without replacements, and its caliper distance was 0.1 of the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score.20 All baseline characteristics were matched as deemed clinically pertinent.

Results

A total of 284 patients (age: median 61 years, interquartile range [IQR] 55-67; 220 [77.5%] men) met our criteria and received either definitive (n=204, 71.8%) or adjuvant (n=80, 28.2%) radiation therapy. Chemotherapy was used in 237 patients (83.5%) and was usually cisplatin. Median follow up was 39.9 months (IQR 33.4-51.3). High level of financial difficulties was reported by 41 patients (14.4%). The baseline characteristics of unmatched patients are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics of patients before matching.

| Low Financial Difficulty |

High Financial Difficulty |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Gender | 0.31 | ||

| Male | 191 (78.6) | 29 (70.7) | |

| Female | 52 (21.4) | 12 (29.3) | |

| Total | 243 (100) | 41 (100) | |

| Marital status | 0.85 | ||

| Single | 59 (24.3) | 9 (22.0) | |

| Married | 132 (54.3) | 24 (58.5) | |

| Divorced | 26 (10.7) | 5 (12.2) | |

| Widowed | 14 (5.8) | 3 (7.3) | |

| NA | 12 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Total | 243 (100) | 41 (100) | |

| Insurance | 0.70 | ||

| Private | 108 (45.0) | 17 (42.0) | |

| Medicare | 101 (41.0) | 16 (39.0) | |

| Medicaid | 18 (7.0) | 5 (12.0) | |

| NA | 16 (7.0) | 3 (7.0) | |

| Total | 243 (100) | 41 (100.0) | |

| Age | 0.002 | ||

| <61 | 108 (44.4) | 29 (70.7) | |

| ≥61 | 135 (55.6) | 12 (29.3) | |

| Total | 243 (100) | 41 (100) | |

| Smoker | 0.95 | ||

| Never | 67 (27.6) | 10 (24.4) | |

| Former | 133 (55.7) | 24 (58.5) | |

| Current | 43 (17.7) | 7 (17.1) | |

| Total | 243 (100) | 41 (100) | |

| T | 0.13 | ||

| X | 1 (0.4) | 1 (2.4) | |

| 0-2 | 120 (49.4) | 15 (36.6) | |

| 3-4 | 116 (47.7) | 23 (56.1) | |

| NA | 6 (2.5) | 2 (4.9) | |

| Total | 243 (100) | 41 (100) | |

| RT complete | 1 | ||

| No | 8 (3.3) | 1 (2.4) | |

| Yes | 233 (95.9) | 40 (97.6) | |

| NA | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Total | 243 (100) | 41 (100) | |

| RT dose | <0.001 | ||

| Median | 70 | 68 | |

| IQR | 70-70 | 66-70 | |

| Response | 0.15 | ||

| No response | 15 (6.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Partial | 187 (77.0) | 30 (73.2) | |

| Complete | 21 (8.6) | 7 (17.1) | |

| NA | 20 (8.2) | 4 (9.8) | |

| Total | 243 (100) | 41 (100) | |

| Chemo groups | 0.69 | ||

| None | 41 (16.9) | 6 (14.6) | |

| Cis q21d | 137 (56.4) | 22 (53.7) | |

| Cis wkly | 18 (7.4) | 6 (14.6) | |

| Cetux wkly | 14 (5.8) | 2 (4.9) | |

| NA | 1 (0.4) | 1 (2.4) | |

| Carbo wkly | 17 (7.0) | 3 (7.3) | |

| Pt regimen NOS | 8 (3.3) | 1 (2.4) | |

| Crossover to cetux | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Crossover to carbo | 5 (2.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Total | 243 (100) | 41 (100) | |

| Nutrition support | 0.09 | ||

| No | 126 (51.9) | 15 (36.6) | |

| Yes | 117 (48.1) | 26 (63.4) | |

| Total | 243 (100) | 41 (100) | |

| Hospitalized | 0.69 | ||

| No | 190 (78.2) | 31 (75.6) | |

| Yes | 53 (21.8) | 10 (24.4) | |

| Total | 243 (100) | 41 (100) | |

| WBC count | <0.001 | ||

| Normal | 192 (79.0) | 26 (63.4) | |

| Low | 3 (1.2) | 0 (0) | |

| High | 12 (4.9) | 9 (22.0) | |

| NA | 36 (14.8) | 6 (14.6) | |

| Total | 243 (100) | 41 (100) | |

| Histology | 0.05 | ||

| Squamous | 229 (94.2) | 35 (85.4) | |

| Others | 14 (5.8) | 6 (14.6) | |

| Total | 243 (100) | 41 (100) | |

| Primary site | 0.46 | ||

| NA | 29 (11.9) | 4 (9.8) | |

| Oral Cavity | 13 (5.3) | 6 (14.6) | |

| Nasopharynx | 7 (2.9) | 1 (2.4) | |

| Oropharynx | 102 (42.0) | 12 (29.3) | |

| Hypopharynx | 11 (4.5) | 1 (2.4) | |

| Glottis | 40 (16.5) | 8 (19.5) | |

| Salivary | 9 (3.7) | 3 (7.3) | |

| Other | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Unknown | 16 (6.6) | 4 (9.8) | |

| Multiple | 14 (5.8) | 2 (4.9) | |

| Total | 243 (100) | 41 (100) | |

| N stage | 0.70 | ||

| 0-1 | 92 (37.9) | 13 (31.7) | |

| 2-3 | 145 (59.7) | 27 (65.9) | |

| NA | 6 (2.4) | 1 (2.4) | |

| Total | 243 (100) | 41 (100) | |

| M stage | 0.03 | ||

| 0 | 233 (95.9) | 36 (87.8) | |

| 1 | 3 (1.2) | 3 (7.3) | |

| NA | 7 (2.9) | 2 (4.9) | |

| Total | 243 (100) | 41 (100) | |

| HPV | 0.04 | ||

| Negative | 45 (18.5) | 14 (34.1) | |

| Positive | 104 (42.8) | 11 (26.8) | |

| NA | 94 (38.7) | 16 (39.0) | |

| Total | 243 (100) | 41 (100) | |

| Surgery | 0.002 | ||

| No | 183 (75.3) | 21 (51.2) | |

| Yes | 60 (24.7) | 20 (48.8) | |

| Total | 243 (100) | 41 (100) | |

| Comorbidity # | 0.003 | ||

| 0 | 42 (17.3) | 8 (19.5) | |

| 1 | 72 (29.6) | 5 (12.2) | |

| 2 | 59 (24.3) | 5 (12.2) | |

| 3+ | 70 (28.8) | 23 (56.1) | |

| Total | 243 (100) | 41 (100) | |

| Hemoglobin | 0.58 | ||

| ≥12 | 168 (69.1) | 26 (63.4) | |

| <12 | 39 (16.0) | 9 (22.0) | |

| NA | 36 (14.8) | 6 (14.6) | |

| Total | 243 (100) | 41 (100) |

HPV: Human papilloma virus; NA: Not available; RT: Radiotherapy; IQR: Interquartile range; Chemo: Chemotherapy; Cis: Cisplatin; Q21d: every 21 days; Wkly: Weekly; Cetux: Cetuximab; Carbo: Carboplatin; Pt: Platinum; NOS: Not otherwise specified; WBC: White blood cell

Of the 284 patients, 179 (63.0%) completed surveys 3-months following completion of treatment. In this subset of patients, high levels of financial difficulties were reported in 32 (17.9%) of patients, with 17 (11.3%) patients without initial high levels of financial difficulties having concerns at 3-months, whereas financial difficulty at 3-months persisting in 15 (53.6%) with initial financial worries. Within the low financial difficulty group, there were 50 (20.6%) relapses (34 distant,16 local) with subsequent treatments including: none (n=15, 30%), systemic therapy (n=25, 50%), surgery (n=10, 20%). 14 (28%) had received immunotherapy at some point during their treatment. By comparison, those with initial high levels of financial difficulties had 14 (33.3%) relapses (7 distant, 7 local) with subsequent treatments including: none (n=6, 42.9%), systemic therapy (n=5, 35.7%), surgery (n=3, 21.4%). 3 (21.4%) had received immunotherapy at some point during their treatment. The association of significant financial difficulties with the receipt of additional treatments (p=0.36) or immunotherapy (p=0.62) following recurrence was not statistically significant. Of those who did not receive additional treatment following disease recurrence, 13 (86.7%) patients in the low financial difficulty group were offered additional treatment vs 4 (66.7%) in the high financial difficulty group.

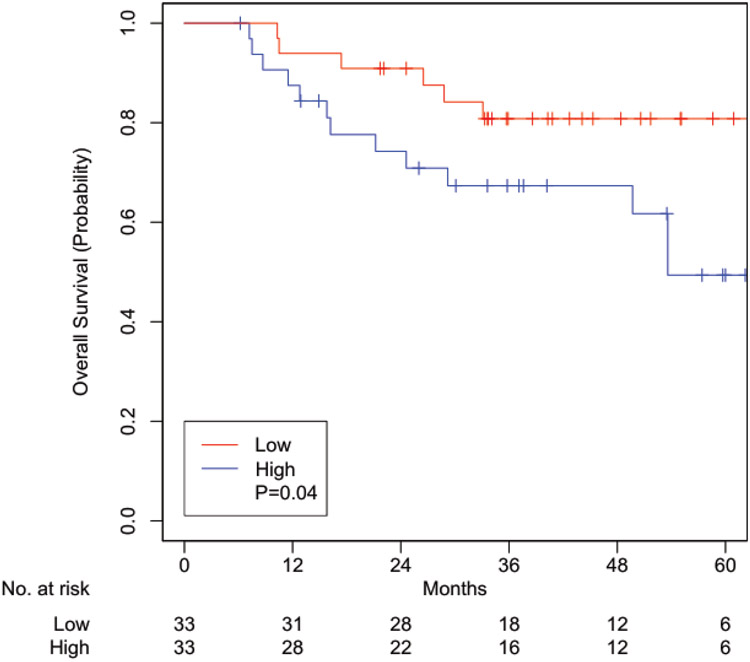

On multivariable analysis adjusted for HPV status, radiation treatment discontinuation, treatment response, hemoglobin level, and comorbidities, those with a high level of financial difficulties were associated with worse OS (hazards ratio [HR] 1.75, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.05-2.94, p=0.03; Table 2) and cancer-specific survival (CSS) (HR 2.28, 95% CI 1.31-3.96, p=0.003; Table 3). A total of 66 patients were matched with well-balanced baseline characteristics (Table 4). High level of financial difficulties remained associated with worse OS (HR 2.72, 95% CI 1.04-7.09, p=0.04; Figure 1) and CSS (HR 3.75, 95% CI 1.22-11.5, p=0.02; Figure 2).

Table 2:

Overall survival univariable and multivariable analyses.

| Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Financial difficulty | ||||

| Low | 1 | 1 | ||

| High | 1.83 (1.12-2.98) | 0.02 | 1.75 (1.05-2.94) | 0.03 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1 | |||

| Female | 0.83 (0.50-1.37) | 0.46 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 1 | 1 | ||

| Married | 0.50 (0.31-0.79) | 0.003 | 0.73 (0.48-1.11) | 0.14 |

| Divorced | 0.58 (0.27-1.21) | 0.15 | ||

| Widowed | 1.41 (0.67-2.97) | 0.37 | ||

| Insurance | ||||

| Private | 1 | 1 | ||

| Medicare | 0.72 (0.45-1.14) | 0.16 | ||

| Medicaid | 2.32 (1.26-4.27) | 0.007 | 0.41 (0.19-0.91) | 0.03 |

| Smoker | ||||

| Never | 1 | |||

| Former | 1.58 (0.94-2.65) | 0.08 | ||

| Current | 1.19 (0.59-2.37) | 0.63 | ||

| Age | ||||

| <61 | 1 | |||

| ≥61 | 1.07 (0.71-1.61) | 0.73 | ||

| T | ||||

| X | <0.001 | 1 | ||

| 0-2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 3-4 | 2.15 (1.38-3.36) | <0.001 | 1.23 (0.75-2.01) | 0.42 |

| NA | 3.71 (1.30-10.60) | 0.01 | 3.57 (1.12-11.35) | 0.03 |

| RT complete | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.18 (0.08-0.39) | <0.001 | 0.33 (0.13-0.79) | 0.01 |

| NA | <0.001 | 1 | ||

| RT dose | ||||

| 1 Gy increase | 1 (1-1) | 0.64 | ||

| Response | ||||

| No response | 1 | 1 | ||

| Partial | 0.11 (0.06-0.21) | <0.001 | 0.07 (0.03-0.15) | <0.001 |

| Complete | 1.35 (0.68-2.71) | 0.39 | ||

| NA | 0.86 (0.40-1.86) | 0.70 | ||

| Chemo groups | ||||

| None | 1 | 1 | ||

| Cis q21d | 0.71 (0.39-1.28) | 0.26 | 1.21 (0.15-9.84) | 0.86 |

| Cis wkly | 1.31 (0.60-2.85) | 0.50 | ||

| Cetux wkly | 2.10 (0.92-4.82) | 0.08 | ||

| NA | 1.12 (0.15-8.58) | 0.92 | ||

| Carbo wkly | 0.72 (0.29-1.79) | 0.48 | ||

| Pt regimen NOS | 1.57 (0.52-4.73) | 0.42 | ||

| Crossover to cetux | 7.09 (1.60-31.52) | 0.01 | ||

| Crossover to carbo | <0.001 | 1 | ||

| Nutrition support | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.69 (1.11-2.56) | 0.01 | 1.09 (0.67-1.75) | 0.74 |

| Hospitalized | ||||

| No | 1 | |||

| Yes | 1.23 (0.77-1.97) | 0.39 | ||

| WBC count | ||||

| Normal | 1 | 1 | ||

| Low | 1.07 (0.15-7.68) | 0.95 | 0.78 (0.35-1.72) | 0.53 |

| High | 1.90 (1.00-3.60) | 0.05 | ||

| NA | 1.12 (0.62-2.04) | 0.70 | ||

| Histology | ||||

| Squamous | 1 | 1 | ||

| Others | 2.02 (1.08-3.79) | 0.03 | 1 (0.38-2.63) | 0.99 |

| Primary site | ||||

| NA | 1 | 1 | ||

| Oral Cavity | 0.97 (0.41-2.32) | 0.95 | 1.93 (0.77-4.85) | 0.16 |

| Nasopharynx | 0.45 (0.10-1.97) | 0.29 | ||

| Oropharynx | 0.49 (0.26-0.92) | 0.03 | ||

| Hypopharynx | 1.54 (0.64-3.66) | 0.33 | ||

| Glottis | 0.68 (0.33-1.38) | 0.28 | ||

| Salivary | 0.59 (0.19-1.80) | 0.36 | ||

| Other | <0.001 | 1 | ||

| Unknown | <0.001 | 1 | ||

| Multiple | 1.31 (0.56-3.03) | 0.53 | ||

| N stage | ||||

| 0-1 | 1 | |||

| 2-3 | 1.29 (0.83-2.01) | 0.26 | ||

| NA | 2.47 (0.75-8.14) | 0.14 | ||

| M stage | ||||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 3.37 (1.23-9.22) | 0.02 | 0.88 (0.19-4.03) | 0.87 |

| NA | 2.12 (0.77-5.78) | 0.14 | ||

| HPV | ||||

| Negative | 1 | 1 | ||

| Positive | 0.40 (0.23-0.69) | <0.001 | 0.44 (0.24-0.81) | 0.008 |

| NA | 0.81 (0.50-1.32) | 0.40 | ||

| Surgery | ||||

| No | 1 | |||

| Yes | 0.89 (0.56-1.43) | 0.64 | ||

| Comorbidity # | ||||

| 0 | 1 | |||

| 1 | 0.78 (0.43-1.41) | 0.41 | ||

| 2 | 0.52 (0.26-1.02) | 0.06 | ||

| 3+ | 0.88 (0.50-1.55) | 0.65 | ||

| Hemoglobin | ||||

| ≥12 | 1 | 1 | ||

| <12 | 2.95 (1.85-4.70) | <0.001 | 2.73 (1.58-4.72) | <0.001 |

| NA | 1.36 (0.74-2.50) | 0.33 | ||

HPV: Human papilloma virus; NA: Not available; RT: Radiotherapy; IQR: Interquartile range; Chemo: Chemotherapy; Cis: Cisplatin; Q21d: every 21 days; Wkly: Weekly; Cetux: Cetuximab; Carbo: Carboplatin; Pt: Platinum; NOS: Not otherwise specified; WBC: White blood cell

Table 3:

Cancer-specific survival univariable and multivariable analyses.

| Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Financial difficulty | ||||

| Low | 1 | 1 | ||

| High | 2.11 (1.25-3.55) | 0.005 | 2.35 (1.35-4.09) | 0.002 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1 | |||

| Female | 0.87 (0.50-1.51) | 0.61 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 1 | 1 | ||

| Married | 0.54 (0.31-0.91) | 0.02 | 0.81 (0.44-1.48) | 0.49 |

| Divorced | 0.78 (0.36-1.68) | 0.52 | ||

| Widowed | 1.70 (0.76-3.80) | 0.20 | ||

| Insurance | ||||

| Private | 1 | 1 | ||

| Medicare | 0.66 (0.39-1.12) | 0.12 | ||

| Medicaid | 2.43 (1.25-4.69) | 0.009 | 0.57 (0.26-1.27) | 0.17 |

| Smoker | ||||

| Never | 1 | |||

| Former | 1.60 (0.90-2.86) | 0.11 | ||

| Current | 1.30 (0.61-2.77) | 0.50 | ||

| Age | ||||

| <61 | 1 | |||

| ≥61 | 1.09 (0.69-1.71) | 0.71 | ||

| T | ||||

| X | <0.001 | 1 | ||

| 0-2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 3-4 | 2.65 (1.58-4.44) | <0.001 | 1.39 (0.78-2.46) | 0.27 |

| NA | 5.46 (1.86-16.06) | 0.002 | 1.11 (0.08-15.21) | 0.94 |

| RT complete | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.20 (0.08-0.49) | <0.001 | 0.73 (0.21-2.51) | 0.62 |

| NA | <0.001 | 1 | ||

| RT dose | ||||

| 1 Gy increase | 0.98 (0.96-1.00) | 0.11 | ||

| Response | ||||

| No response | 1 | 1 | ||

| Partial | 0.07 (0.03-0.14) | <0.001 | 0.04 (0.02-0.09) | <0.001 |

| Complete | 1.34 (0.67-2.70) | 0.41 | ||

| NA | 0.61 (0.26-1.42) | 0.25 | ||

| Chemo groups | ||||

| None | 1 | 1 | ||

| Cis q21d | 0.62 (0.33-1.19) | 0.15 | 0.66 (0.08-5.32) | 0.70 |

| Cis wkly | 1.35 (0.59-3.08) | 0.48 | ||

| Cetux wkly | 1.60 (0.60-4.21) | 0.35 | ||

| NA | 1.20 (0.15-9.35) | 0.87 | ||

| Carbo wkly | 0.57 (0.20-1.63) | 0.30 | ||

| Pt regimen NOS | 1.80 (0.58-5.52) | 0.31 | ||

| Crossover to cetux | 8.37 (1.85-37.86) | 0.006 | ||

| Crossover to carbo | <0.001 | 1 | ||

| Nutrition support | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.68 (1.05-2.68) | 0.03 | 1.14 (0.60-2.14) | 0.69 |

| Hospitalized | ||||

| No | 1 | |||

| Yes | 1.19 (0.70-2.02) | 0.53 | ||

| WBC count | ||||

| Normal | 1 | 1 | ||

| Low | 1.42 (0.20-10.29) | 0.73 | 0.97 (0.38-2.46) | 0.95 |

| High | 2.52 (1.31-4.85) | 0.006 | ||

| NA | 1.40 (0.74-2.62) | 0.30 | ||

| Histology | ||||

| Squamous | 1 | 1 | ||

| Others | 2.58 (1.36-4.90) | 0.004 | 1.20 (0.27-5.40) | 0.81 |

| Primary site | ||||

| NA | 1 | 1 | ||

| Oral Cavity | 1.08 (0.42-2.78) | 0.88 | 2.83 (0.96-8.34) | 0.06 |

| Nasopharynx | 0.56 (0.12-2.53) | 0.45 | ||

| Oropharynx | 0.47 (0.23-0.96) | 0.04 | ||

| Hypopharynx | 1.45 (0.54-3.92) | 0.47 | ||

| Glottis | 0.69 (0.31-1.54) | 0.37 | ||

| Salivary | 0.75 (0.24-2.35) | 0.62 | ||

| Other | <0.001 | 1 | ||

| Unknown | <0.001 | 1 | ||

| Multiple | 1.26 (0.49-3.27) | 0.63 | ||

| N stage | ||||

| 0-1 | 1 | |||

| 2-3 | 1.49 (0.90-2.48) | 0.12 | ||

| NA | 3.47 (1.03-11.67) | 0.04 | ||

| M stage | ||||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 4.38 (1.59-12.09) | 0.004 | 2.98 (0.95-9.38) | 0.06 |

| NA | 2.71 (0.98-7.46) | 0.05 | 2.85 (0.91-8.95) | 0.07 |

| HPV | ||||

| Negative | 1 | 1 | ||

| Positive | 0.41 (0.22-0.77) | 0.006 | 0.61 (0.32-1.18) | 0.14 |

| NA | 0.97 (0.56-1.67) | 0.90 | ||

| Surgery | ||||

| No | 1 | |||

| Yes | 0.94 (0.56-1.57) | 0.80 | ||

| Comorbidity # | ||||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 0.81 (0.42-1.54) | 0.51 | 0.22 (0.10-0.51) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 0.40 (0.18-0.89) | 0.02 | ||

| 3+ | 0.81 (0.44-1.52) | 0.51 | ||

| Hemoglobin | ||||

| ≥12 | 1 | 1 | ||

| <12 | 2.70 (1.58-4.60) | <0.001 | 2.46 (1.38-4.40) | 0.002 |

| NA | 1.56 (0.82-2.97) | 0.17 | ||

HPV: Human papilloma virus; NA: Not available; RT: Radiotherapy; IQR: Interquartile range; Chemo: Chemotherapy; Cis: Cisplatin; Q21d: every 21 days; Wkly: Weekly; Cetux: Cetuximab; Carbo: Carboplatin; Pt: Platinum; NOS: Not otherwise specified; WBC: White blood cell

Table 4:

Baseline characteristics of matched pairs.

| Low Financial Difficulty |

High Financial Difficulty |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Gender | 0.78 | ||

| Male | 25 (75.8) | 23 (69.7) | |

| Female | 8 (24.2) | 10 (30.3) | |

| Total | 33 (100) | 33 (100) | |

| Marital status | 0.92 | ||

| Single | 9 (27.3) | 8 (24.2) | |

| Married | 18 (54.5) | 18 (54.5) | |

| Divorced | 3 (9.1) | 5 (15.2) | |

| Widowed | 3 (9.1) | 2 (6.1) | |

| NA | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Total | 33 (100) | 33 (100) | |

| Insurance | 1.00 | ||

| Private | 14 (43.0) | 13 (40.0) | |

| Medicare | 12 (36.0) | 12 (36.0) | |

| Medicaid | 5 (15.0) | 5 (15.0) | |

| NA | 2 (6.0) | 3 (9.0) | |

| Total | 33 (100) | 33 (100) | |

| Age | 0.79 | ||

| <61 | 23 (69.7) | 21 (63.6) | |

| ≥61 | 10 (30.3) | 12 (36.4) | |

| Total | 33 (100) | 33 (100) | |

| Smoker | 0.89 | ||

| Never | 7 (21.2) | 8 (24.2) | |

| Former | 19 (57.6) | 20 (60.6) | |

| Current | 7 (21.2) | 5 (15.2) | |

| Total | 33 (100) | 33 (100) | |

| T | 0.53 | ||

| X | 0 (0) | 1 (3.0) | |

| 0-2 | 13 (39.4) | 15 (45.5) | |

| 3-4 | 20 (60.6) | 16 (48.5) | |

| NA | 0 (0) | 1 (3.0) | |

| Total | 33 (100) | 33 (100) | |

| RT complete | 1 | ||

| No | 1 (3.0) | 1 (3.0) | |

| Yes | 32 (97.0) | 32 (97.0) | |

| NA | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Total | 33 (100) | 33 (100) | |

| RT dose | 0.33 | ||

| Median | 70 | 70 | |

| IQR | 66-70 | 66-70 | |

| Response | 0.54 | ||

| No response | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Partial | 28 (84.8) | 25 (75.8) | |

| Complete | 2 (6.1) | 5 (15.2) | |

| NA | 3 (9.1) | 3 (9.1) | |

| Total | 33 (100) | 33 (100) | |

| Chemo groups | 0.19 | ||

| None | 9 (27.3) | 4 (12.1) | |

| Cis q21d | 19 (57.6) | 17 (51.5) | |

| Cis wkly | 1 (3.0) | 6 (18.2) | |

| Cetux wkly | 1 (3.0) | 2 (6.1) | |

| NA | 0 (0) | 1 (3.0) | |

| Carbo wkly | 2 (6.1) | 2 (6.1) | |

| Pt regimen NOS | 0 (0) | 1 (3.0) | |

| Crossover to cetux | 1 (3.0) | 0 (0) | |

| Crossover to carbo | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Total | 33 (100) | 33 (100) | |

| Nutrition support | 0.22 | ||

| No | 19 (57.6) | 13 (39.4) | |

| Yes | 14 (42.4) | 20 (60.6) | |

| Total | 33 (100) | 33 (100) | |

| Hospitalized | 0.76 | ||

| No | 27 (81.8) | 25 (75.8) | |

| Yes | 6 (18.2) | 8 (24.2) | |

| Total | 33 (100) | 33 (100) | |

| WBC count | 0.063 | ||

| Normal | 22 (66.7) | 20 (60.6) | |

| Low | 2 (6.1) | 0 (0) | |

| High | 2 (6.1) | 9 (27.3) | |

| NA | 7 (21.2) | 4 (12.1) | |

| Total | 33 (100) | 33 (100) | |

| Histology | 0.43 | ||

| Squamous | 31 (93.9) | 28 (84.5) | |

| Others | 2 (6.1) | 5 (15.2) | |

| Total | 33 (100) | 33 (100) | |

| Primary site | 0.50 | ||

| NA | 5 (15.2) | 3 (9.1) | |

| Oral Cavity | 3 (9.1) | 4 (12.1) | |

| Nasopharynx | 0 (0) | 1 (3.0) | |

| Oropharynx | 9 (27.3) | 12 (36.4) | |

| Hypopharynx | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Glottis | 10 (30.3) | 4 (12.1) | |

| Salivary | 3 (9.1) | 3 (9.1) | |

| Other | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Unknown | 1 (3.0) | 4 (12.1) | |

| Multiple | 2 (6.1) | 2 (6.1) | |

| Total | 33 (100) | 33 (100) | |

| N stage | 0.14 | ||

| 0-1 | 19 (57.6) | 12 (36.4) | |

| 2-3 | 14 (42.4) | 21 (63.6) | |

| NA | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Total | 33 (100) | 33 (100) | |

| M stage | 0.11 | ||

| 0 | 33 (100) | 29 (87.9) | |

| 1 | 0 (0) | 3 (9.1) | |

| NA | 0 (0) | 1 (3.0) | |

| Total | 33 (100) | 33 (100) | |

| HPV | 0.70 | ||

| Negative | 8 (24.2) | 10 (30.3) | |

| Positive | 9 (27.3) | 11 (33.3) | |

| NA | 16 (48.5) | 12 (36.4) | |

| Total | 33 (100) | 33 (100) | |

| Surgery | 0.29 | ||

| No | 25 (75.8) | 20 (60.6) | |

| Yes | 8 (24.2) | 13 (39.4) | |

| Total | 33 (100) | 33 (100) | |

| Comorbidity # | 0.94 | ||

| 0 | 6 (18.2) | 7 (21.2) | |

| 1 | 4 (12.1) | 5 (15.2) | |

| 2 | 7 (21.2) | 5 (15.2) | |

| 3+ | 16 (48.5) | 16 (48.5) | |

| Total | 33 (100) | 33 (100) | |

| Hemoglobin | 0.44 | ||

| ≥12 | 16 (48.5) | 21 (63.6) | |

| <12 | 10 (30.3) | 8 (24.2) | |

| NA | 7 (21.2) | 4 (12.1) | |

| Total | 33 (100) | 33 (100) |

HPV: Human papilloma virus; NA: Not available; RT: Radiotherapy; IQR: Interquartile range; Chemo: Chemotherapy; Cis: Cisplatin; Q21d: every 21 days; Wkly: Weekly; Cetux: Cetuximab; Carbo: Carboplatin; Pt: Platinum; NOS: Not otherwise specified; WBC: White blood cell

Figure 1:

Overall survival Kaplan-Meier curves of propensity score matched cohorts of patients experiencing high financial toxicity versus low financial toxicity

Figure 2:

Cancer-specific survival Kaplan-Meier curves of propensity score matched cohorts of patients experiencing high financial toxicity versus low financial toxicity.

Discussion

This is first analysis to show a statistically significant impact of baseline high financial toxicity on overall and cancer-specific survival in patients with head and neck (or any type of) cancer.

Interestingly, there was no significant increase in financial difficulties at 3-months post-treatment relative to pre-treatment measures. Furthermore, it appeared that almost half of the patients who initially endorsed financial difficulties no longer reported them at 3-months post-treatment. While interesting, we exercise caution in interpreting these data giving that 105 (37.0%) patients did not provide financial toxicity information at this time point.

Using the same EORTC QLQ-C30 question on FT, Klein et al. found that increasing baseline FT was associated with shorter progression free survival (p=0.01) but not OS (p=0.67) in 43 patients treated with chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer.21 Ramsey et al. linked regional cancer registry and federal bankruptcy records and used propensity score matching to account for differences in several demographic and clinical factors between patients who did and did not file for bankruptcy. They found the adjusted mortality among patients with cancer who filed for bankruptcy nearly doubled (HR 1.79, 95% CI, 1.64 to 1.96). Colorectal, prostate, and thyroid cancers had the highest HRs. Interestingly like Klein et al., Ramsey et al. failed to show a statistically significant HR for lung cancer patients (p=0.172).11

Nonetheless, the HRs for OS shown in this study of 1.75 to 2.72 for the overall population and the match pair respectively are quite consistent with the overall cohort HR of 1.79 by Ramsey et al. If confirmed in other cohorts, this would suggest that relatively mild FT at baseline may have the same impact on mortality as an extreme consequence like post therapy bankruptcy. As some have suggested, FT at baseline should itself become a target for mitigation in prospective trials and clinical practice.22-25 Furthermore, FT should be considered as a stratifying variable for clinical trials looking at novel therapies.

There is a broad literature showing that FT can impact many other aspects of health-related quality of life (QOL). Patients who reported that cancer caused “a lot” of financial problems had a 4-fold decrease in the likelihood of reporting excellent, very good, or good QOL (P < .001).26 Similarly, there appears to be a strong relationship between decreasing levels of financial reserves and overall QOL.27 Several groups have reported that baseline general measures of QOL can be a predictor of OS in a variety of cancers28,29 including head and neck.30 Among head and neck cancer patients, the amount of medical expenses were higher than other cancers, were comparable between surgical and nonsurgical treatments, and were associated with worse physical and social-emotional functioning, poverty, unemployment.8,9,31 They were also less likely to be compliant with medications and clinic appointments.32 Patients’ regret on their treatment choices increased for those who underwent multimodality treatments, and survival was not as important for elderly patients.33 In our study, there were more patients with high FT who underwent prior head and neck surgery, although prior surgery was not associated with survival outcomes. However, it is feared that FT can alter patient decision making and may potentially cause them to forgo appropriate therapy to minimize monetary drain, thus impacting outcomes.22,34 Thus, although the association of high FT with the absence of additional interventions following recurrences was not noted in our study in part due to a small sample size, FT may impact patients’ decision making and future treatment choices ultimately affecting their survival outcomes.

Methods to mitigate FT would likely require multidisciplinary approaches. Informed, shared decision making among clinicians and patients to consider medical costs may improve compliance to medical recommendations and reduce out-of-pocket costs.35-38 As FT is also associated closely with income and employment status,8,32 the early involvement of social workers and financial care counselors to mitigate FT using available resources would be crucial.39 In addition, if found to be safe and effective in future phase III studies, the de-escalation of radiation in select patients may be also considered to reduce the cost of radiation by 33% and the total cost by 21%.40

Limitations

This is a retrospective review with its attendant limitations. Specific causes of death were not available for analysis since some patients continued their further care at outside facilities. In addition, a validated instrument to measure financial difficulties is lacking.41 Since financial toxicity in our study was measured by patient-reported financial difficulties using standardized QOL surveys at a single time point prior to radiation, it may not comprehensively reflect one’s baseline financial distress. Other pertinent variables were unavailable for analysis, such as education level, household income, and the extent of social support from caregivers. With only 41 of 284 patients (14.4%) reporting baseline FT, the analysis is at risk for small sample size effects. Moreover, several factors are known to impact of survival in head and neck cancer. Attempts to correct for the effects of these factors by creating propensity score matched pairing further reduced our numbers leaving only 33 matched pairs. Despite these small numbers, however, FT persisted as a statistically significant predictor of both OS and CSS in the overall and matched pair analysis.

Conclusion

High baseline FT had a statistically significant association with worsened HR for overall and cancer-specific mortality. On matched pair analysis, high FT remained associated with worse OS (HR 2.72, 95% CI 1.04-7.09, p=0.04) and CSS (HR 3.75, 95% CI 1.22-11.5, p=0.02). Methods to mitigate FT are urgently needed.

Highlights:

HNC patients frequently struggle with financial difficulties

Financial toxicity was associated with worse OS and CSS in HNC

Methods to mitigate financial toxicity in HNC are needed

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to acknowledge Adam Oberkircher, PA and Kelsey Smith, PA for their tireless efforts to provide excellent care of these patients.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant (P30CA016056).

Role of Funding Source:

The funding source had no role in the design of this study and did not have any role during its execution, analyses, interpretation of the data, or decision to submit results.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared

Data Availability:

The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly for the privacy of individuals that participated in the study. The data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Hajdu SI. Greco-Roman thought about cancer. Cancer. 2004;100(10):2048–2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang PY, Huang WY, Lin CL, et al. Propranolol Reduces Cancer Risk: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(27):e1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramsey S, Blough D, Kirchhoff A, et al. Washington State cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(6):1143–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernard DS, Farr SL, Fang Z. National estimates of out-of-pocket health care expenditure burdens among nonelderly adults with cancer: 2001 to 2008. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(20):2821–2826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davidoff AJ, Erten M, Shaffer T, et al. Out-of-pocket health care expenditure burden for Medicare beneficiaries with cancer. Cancer. 2013;119(6):1257–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Harris Poll: ASCO 2018 Cancer Opinions Survey. https://wwwascoorg/sites/new-wwwascoorg/files/content-files/research-and-progress/documents/2018-NCOS-Resultspdf. 2018.

- 7.Meeker CR, Geynisman DM, Egleston BL, et al. Relationships Among Financial Distress, Emotional Distress, and Overall Distress in Insured Patients With Cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(7):e755–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Massa ST, Osazuwa-Peters N, Adjei Boakye E, Walker RJ, Ward GM. Comparison of the Financial Burden of Survivors of Head and Neck Cancer With Other Cancer Survivors. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(3):239–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rogers SN, Harvey-Woodworth CN, Hare J, Leong P, Lowe D. Patients' perception of the financial impact of head and neck cancer and the relationship to health related quality of life. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;50(5):410–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Souza JA, Kung S, O'Connor J, Yap BJ. Determinants of Patient-Centered Financial Stress in Patients With Locally Advanced Head and Neck Cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(4):e310–e318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, et al. Financial Insolvency as a Risk Factor for Early Mortality Among Patients With Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(9):980–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Platek ME, McCloskey SA, Cruz M, et al. Quantification of the effect of treatment duration on local-regional failure after definitive concurrent chemotherapy and intensity-modulated radiation therapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2013;35(5):684–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fung-Kee-Fung SD, Hackett R, Hales L, Warren G, Singh AK. A prospective trial of volumetric intensity-modulated arc therapy vs conventional intensity modulated radiation therapy in advanced head and neck cancer. World J Clin Oncol. 2012;3(4):57–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fayers PM, Aaronson NK, Bjordal K, et al. The EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual (3rd Edition). 2001; https://www.eortc.org/app/uploads/sites/2/2018/02/SCmanual.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mady LJ, Lyu L, Owoc MS, et al. Understanding financial toxicity in head and neck cancer survivors. Oral Oncol. 2019;95:187–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han HR, Hermann GM, Ma SJ, et al. Matched pair analysis to evaluate the impact of hospitalization during radiation therapy as an early marker of survival in head and neck cancer patients. Oral Oncol. 2020;109:104854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghadjar P, Pottgen C, Joos D, et al. Haemoglobin and creatinine values as prognostic factors for outcome of concurrent radiochemotherapy in locally advanced head and neck cancers : Secondary results of two European randomized phase III trials (ARO 95-06, SAKK 10/94). Strahlenther Onkol. 2016;192(8):552–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCloskey SA, Jaggernauth W, Rigual NR, et al. Radiation treatment interruptions greater than one week and low hemoglobin levels (12 g/dL) are predictors of local regional failure after definitive concurrent chemotherapy and intensity-modulated radiation therapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Am J Clin Oncol. 2009;32(6):587–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Austin PC. Optimal caliper widths for propensity-score matching when estimating differences in means and differences in proportions in observational studies. Pharm Stat. 2011;10(2):150–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klein J, Bodner W, Garg M, Kalnicki S, Ohri N. Pretreatment financial toxicity predicts progression-free survival following concurrent chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Future Oncol. 2019;15(15):1697–1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carrera PM, Kantarjian HM, Blinder VS. The financial burden and distress of patients with cancer: Understanding and stepping-up action on the financial toxicity of cancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(2):153–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hazell SZ, Fu W, Hu C, et al. Financial toxicity in lung cancer: an assessment of magnitude, perception, and impact on quality of life. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(1):96–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jagsi R, Ward KC, Abrahamse PH, et al. Unmet need for clinician engagement regarding financial toxicity after diagnosis of breast cancer. Cancer. 2018;124(18):3668–3676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LaRocca CJ, Li A, Lafaro K, et al. The impact of financial toxicity in gastrointestinal cancer patients. Surgery. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fenn KM, Evans SB, McCorkle R, et al. Impact of financial burden of cancer on survivors' quality of life. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(5):332–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lathan CS, Cronin A, Tucker-Seeley R, Zafar SY, Ayanian JZ, Schrag D. Association of Financial Strain With Symptom Burden and Quality of Life for Patients With Lung or Colorectal Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(15):1732–1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braun DP, Gupta D, Staren ED. Quality of life assessment as a predictor of survival in non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lis CG, Cambron JA, Grutsch JF, Granick J, Gupta D. Self-reported quality of life in users and nonusers of dietary supplements in cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14(2):193–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fang FM, Liu YT, Tang Y, Wang CJ, Ko SF. Quality of life as a survival predictor for patients with advanced head and neck carcinoma treated with radiotherapy. Cancer. 2004;100(2):425–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sher DJ, Agiro A, Zhou S, Day AT, DeVries A. Commercial Claims-Based Comparison of Survival and Toxic Effects of Definitive Radiotherapy vs Primary Surgery in Patients With Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;144(10):913–922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beeler WH, Bellile EL, Casper KA, et al. Patient-reported financial toxicity and adverse medical consequences in head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2020;101:104521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Windon MJ, D'Souza G, Faraji F, et al. Priorities, concerns, and regret among patients with head and neck cancer. Cancer. 2019;125(8):1281–1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schroder SL, Schumann N, Fink A, Richter M. Coping mechanisms for financial toxicity: a qualitative study of cancer patients' experiences in Germany. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(3):1131–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zafar SY, Chino F, Ubel PA, et al. The utility of cost discussions between patients with cancer and oncologists. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(9):607–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schnipper LE, Davidson NE, Wollins DS, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology Statement: A Conceptual Framework to Assess the Value of Cancer Treatment Options. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(23):2563–2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meisenberg BR, Varner A, Ellis E, et al. Patient Attitudes Regarding the Cost of Illness in Cancer Care. Oncologist. 2015;20(10):1199–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bestvina CM, Zullig LL, Rushing C, et al. Patient-oncologist cost communication, financial distress, and medication adherence. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(3):162–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith SK, Nicolla J, Zafar SY. Bridging the gap between financial distress and available resources for patients with cancer: a qualitative study. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(5):e368–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma DJ, Price KA, Moore EJ, et al. Phase II Evaluation of Aggressive Dose De-Escalation for Adjuvant Chemoradiotherapy in Human Papillomavirus-Associated Oropharynx Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(22):1909–1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Witte J, Mehlis K, Surmann B, et al. Methods for measuring financial toxicity after cancer diagnosis and treatment: a systematic review and its implications. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(7):1061–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly for the privacy of individuals that participated in the study. The data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.