Abstract

Background

Nurse team leaders encounter considerable ethical challenges that necessitate using effective strategies to overcome them. However, there is a lack of research exploring the experiences of nurse team leaders in Indonesia who face ethical dilemmas in their professional duties.

Objective

This study aimed to explore nurse team leaders’ experiences regarding strategies and challenges in dealing with ethical problems in hospital settings in Indonesia.

Methods

This qualitative study employed a hermeneutic phenomenology design. Online semi-structured interviews were conducted between November 2021 and February 2022 among 14 nurse team leaders selected using a snowball sampling from seven hospitals (three public and four private hospitals). Van Manen’s approach was used for data analysis.

Results

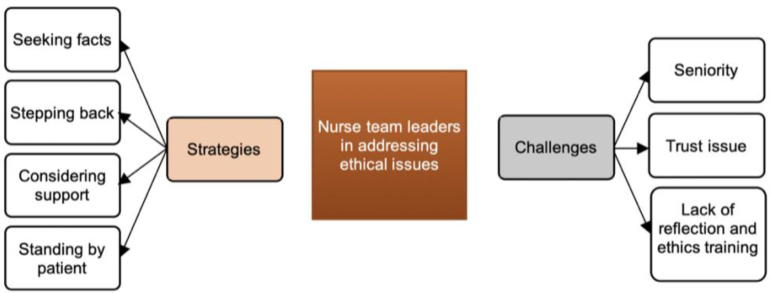

The strategies for overcoming ethical dilemmas included (i) seeking the facts, (ii) stepping back, (iii) considering support, and (iv) standing by patients. The challenges for the nurse team leaders in resolving ethical problems consisted of (i) seniority, (ii) trust issue, and (iii) lack of reflection and ethics training.

Conclusion

Nurse team leaders recognize their specific roles in the midst of ethical challenges and seek strategies to deal with them. However, a negative working environment might impact ethical behavior and compromise the provision of quality care. Therefore, it is imperative for hospital management to take note of these findings and address issues related to seniority by providing regular ethics training and group reflection sessions to maintain nurses' ethical knowledge in hospital practice. Such interventions can support nurse team leaders in resolving ethical dilemmas and provide a conducive environment for ethical decision-making, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Keywords: ethics, hospitals, nurse administrators, leadership, team leader, hermeneutic, Indonesia

Background

In 2021, Gallup’s annual poll revealed that nursing was voted the most ethical and honest profession (Saad, 2022). This achievement is largely attributed to the efforts of those in nursing leadership positions who are recognized for their actions and interventions aligned with their values and beliefs (Stanley & Stanley, 2018). Nurse leaders can be found at any healthcare organization level and in all clinical settings and hold various positions, including nurse team leader, first-line nurse manager, clinical nurse specialist, and nurse executive (Birkholz et al., 2022; Stanley & Stanley, 2018).

However, nurse leaders’ roles face complex challenges (Sugianto et al., 2022), including ethical challenges in their daily practice, such as complaints, critical decision-making, patient and family demands, and conflicts between staff (Aitamaa et al., 2016), which require an excellent strategy to respond appropriately. Thus, ethical leadership is crucial, aligning nursing fundamentals with ethical nursing behavior and positively impacting clinical practice (Barkhordari-Sharifabad et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2019).

In the context of the inpatient department, nurse leaders experience considerable pressure, and ethical challenges in clinical practice are prevalent, such as inadequate ethical vocabulary, competing demands on nurse leaders, and concerns about young nurses' ethical awareness (Storaker et al., 2022). Nevertheless, ethical nursing leaders show professional insight and mentorship through empathic interactions, ethical behavior, and exalted manners (Barkhordari-Sharifabad et al., 2018).

One specific type of nurse leader is the nurse team leader, who plays an essential role in managing and coordinating their team during working hours. However, there is a lack of research exploring their experiences overcoming ethical dilemmas, particularly in Indonesia. Therefore, this study aimed to fill this gap. Specifically, the study aimed to explore the experiences of nurse team leaders regarding challenges and strategies for resolving ethical problems in hospital settings. This study will contribute to the development of ethical leadership in nursing and inform future research on the role of nurse team leaders in promoting ethical nursing practice.

Overview of Nursing Care Delivery Models in Indonesia

In Indonesia, the nursing delivery model used in inpatient departments generally follows the person-centered care method (Juanamasta et al., 2021b). The patient-centered care method has three models: individual, team, and primary care (Parreira et al., 2021), and the model depends on the unit type and the number of beds. However, most hospitals in Indonesia use the team delivery model (Juanamasta et al., 2021a). Therefore, the role of the team leader is emphasized as they are responsible for decision-making during each shift, including complex, ethical, and interprofessional healthcare and patient issues (Arisanti et al., 2018).

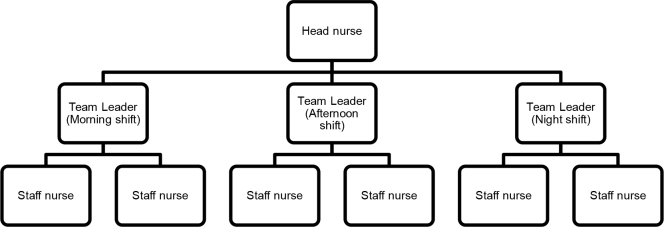

A hierarchical reporting model is applied when reporting problems (Figure 1). Staff nurses, also known as associate nurses or “Perawat Pelaksana” in Bahasa Indonesia, report to the nurse team leader or nurse shift coordinator, also known as “Ketua Tim” in Bahasa Indonesia. The nurse team leader then consults with the head nurse and continues to escalate the problem to upper management if it cannot be solved (Gunawan & Juanamasta, 2022).

Figure 1.

Typical team care delivery model structure

Head nurses or head wards/units typically work only during the morning shift. Staff nurses can consult with them if there are any problems. Unfortunately, they are not present during the afternoon and night shifts, during which the nurse team leaders handle most issues. A previous study found that the afternoon and night shifts increase the number of miscarriages (Bonde et al., 2013). Therefore, the essential role of the nurse team leader in dealing with ethical challenges should be considered.

Methods

Study Design

Hermeneutic phenomenology was used for this study to explore the experiences of nurse team leaders when dealing with ethical issues (Spence, 2017; Todres & Wheeler, 2001). The aim of phenomenology is to understand the human experience by interpreting the phenomena encountered daily. Specifically, Heidegger's philosophical approach is used in this study, which emphasizes that a person’s “being” in time shapes their interpretation of experiences. Heidegger's concept of Dasein, which refers to how humans live their lives, is essential in reflecting on the existence (Todres & Wheeler, 2001). Humans engage in inter-subjectivity, a subjective encounter with the objective elements of the world, to reflect on their existence, which is consistent with the concept of Dasein. This study's philosophical approach comes closer to one's life world and the setting of their regular contacts (Lamb et al., 2019), which is critical in understanding the experiences of nurse team leaders.

Participants

The respondents were selected from seven hospitals (three public and four private hospitals) in Indonesia. Specifically, the participants were nurse team leaders who met the inclusion criteria: clinical nurses currently working in an inpatient environment, having experience as a nurse team leader, and having reported at least one ethical case problem within 90 days prior to the start of the study (1 November 2021– 28 February 2022). Due to the limited information on nurse team leaders who had previously faced ethical issues, the participants were recruited using a snowball sampling technique. During the process, sixteen nurses refused to provide information for various reasons, such as discomfort with the topic, concern about its impact, feeling unsafe, and busy working conditions. Finally, 14 registered nurses (RNs) were included. The number of participants was decided when data reached saturation, or no new codes were extracted. It is noted that the researchers analyzed the data after each interview.

Data Collection

Interviews were conducted based on the nurse’s time and place. Online interviews were preferred using video conferencing tools like Zoom or Google Meet and social media platforms like WhatsApp, Line, and Messenger due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Gunawan et al., 2022). This study used Bahasa Indonesia for interviews, analysis, and interpretation. The lead author interviewed each participant for approximately an hour, mostly in the hospital’s conference room after their shifts were over. Semi-structured interview guideline was prepared, and the opening question was, “Please tell me about nursing ethical issues.” The interviews were dialogical, with a special focus on the strategies and challenges faced by the nurse team leaders to deal with ethical problems. Answers to the primary question guided the interviewer to ask other exploratory questions concerning the nurse team leader’s strategies and challenges to facing ethical dilemmas by asking, “Can you tell me more?” “Can you give an example?”

The research team had four members: the lead investigator, one researcher, one research team member with managerial responsibilities or supervision of nurses, and one member directly tied to the study organization. The research team members used online meetings to track the study’s progress and conclusions. All members have experience in nursing research. No repeated interviews in this study, and it is noted that there was no relationship between researchers and participants that might influence the responses.

Data Analysis

The researchers utilized Van Manen’s approach (Van Manen, 2016) to analyze the data, which provides four levels of analysis that help to gain a more profound understanding of the significance of the living experience of the individuals being studied. These four levels of analysis include (1) identifying thematic aspects, (2) extracting thematic statements, (3) creating linguistic transformations, and (4) extracting thematic descriptions (Ritruechai et al., 2018). The transcripts of the interviews were read multiple times to gain a holistic comprehension of the information. All essential parts were marked up with codes. The initial coding was done by the first and second authors in Bahasa Indonesia, and then similar data were grouped into sub-themes and themes. The findings were translated into English by the first and second authors and then reviewed for accuracy by the third and fourth authors. Finally, the team discussed and agreed on the sub-themes and themes.

Trustworthiness

The researchers utilized specific rules to gain rigor and trustworthy criteria to ensure the study’s methodological soundness. Firstly, using a well-known method for phenomenological research (Van Manen, 1990) provided rigor. Additionally, evaluation methods of Guba and Lincoln (1989) were utilized, which included staying in touch with the participants for a long time and being honest about the study’s focus, in-depth data analysis, discussion of emerging themes with participants, and modification of themes based on participant input (Polit & Beck, 2017). These processes were documented in Excel files to ensure confirmability and dependability, which included participant descriptions in the final report to illustrate the applicability of the study’s findings. Furthermore, to ensure the credibility of the study, participants received a process summary and diagram, and member checks were conducted. In addition, qualitative research and nursing leadership experts were consulted throughout the study to improve accuracy. Finally, transferability was provided by explaining the study’s context, background, and stage in the introduction and choosing participants with the greatest possible variance.

Ethical Considerations

The Bali Institute of Technology and Health Research Ethics Committee (No. 04.0554/KEPITEKES-BALI/XI/2021) granted ethical approval for the study and data collection. Before participating, participants were provided with written and verbal information regarding the study’s purpose and methods. After agreeing to participate by signing the consent form and establishing a time and place for the interview, participants could withdraw at any point before data collection was concluded. Each interview was assigned a code instead of being identified by name or institution to ensure confidentiality and protect participants’ privacy. As a result, their identities and information were kept confidential.

Results

Of 14 participants, the majority of the participants were females (78.6%), aged 36-45 years (50%), and held a bachelor’s degree level in nursing (71.4%). In addition, most participants worked between 10 – 20 years (50%), eight (57.1%) worked in public hospitals, and six (42.9%) worked in private hospitals (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants

| Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 3 | 21.4 |

| Female | 11 | 78.6 |

| Age | ||

| Early adulthood (26-35 years) | 3 | 21.4 |

| Late adulthood (36-45 years) | 7 | 50 |

| Early old age (46-55 years) | 4 | 28.6 |

| Education | ||

| Diploma in Nursing | 4 | 28.6 |

| Bachelor in Nursing | 10 | 71.4 |

| Working experience | ||

| < 10 years | 4 | 28.6 |

| 10-20 years | 7 | 50 |

| > 20 years | 3 | 21.4 |

| Hospital | ||

| Public | 8 | 57.1 |

| Private | 6 | 42.9 |

Aligned with the study objective, the findings of this study were grouped into strategies and challenges in facing ethical problems (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Strategies and challenges in addressing ethical issues

Strategies in Resolving Ethical Dilemmas

Nurse team leaders have to use appropriate strategies when dealing with an ethical dilemma, especially when the problems involve patients. The techniques include seeking the facts, stepping back, considering support, and standing by patients.

Seeking the fact. Nurses have to seek facts to solve the problem. First, the patient’s complaint has to be checked and rechecked to confirm the problem. Then, they need to check all nursing staff and other teams. The participants express this:

“A caregiver complained about my member (nurse) that she (member) refused to answer and give information about everything when she injected the new chemical medicine to my son (caregiver’s son), and just said “don’t know” when I (caregiver) asked. At that time, I (Nurse) was head of the nursing team. So, I learned the truth from the caregiver, my member nurse, and other colleagues. It was found that the nurse was acting really badly.” (N 5)

Stepping back. The nurse team leaders should be aware of their position. If a problem might become bigger, it is better to step back. They also need to remind their staff to do the same. The participants state this:

“I (Nurse team leader) saw my member (Nurse) talk with a male family caregiver who was drunk. I walked and told my member to go back to the nurse station because the headward called to ask about her job.” (N 1)

“I have a lot of bad experiences. Now, I understand, I have to consider our position before dealing with the problem.” (N 3)

Considering support. Asking for another team’s support is crucial to give direction when deciding, particularly to follow up on patient treatment, because there are different situations among respondents. It is expressed by the participants:

“Actually, at the hospital, there are procedures and policies regarding presenting a palliative team, but this condition or presenting a palliative team cannot be brought to us immediately.” (N 4)

“There was a time I [team leader] was not so sure which way was correct, so my team and I decided to call the expert [Nurse who takes responsibility for the abortion policy of the province] to get support and information.” (N 13)

Standing by the patient. Hospitals need to gain benefits to maintain their employees and keep the facilities. However, the nurse’s position is sometimes a dilemma between the patient’s condition and the workplace need. The participants stated:

“An ethical situation arose when a patient had to discharge because they wanted to die at home. The breathing machine and oxygen tank were often not enough to lend because, if allowed, they borrowed to back home, and during that time, patients still survived. While in the hospital, there might have a case(s) with a greater need to use it. I [team leader] and the team have to decide what should be done to benefit all patients equally.” (N 2)

“When I [team leader] was taking care of underprivileged patients who used BPJS [Indonesia Universal Health Coverage], my manager said that the patient should be referred to another hospital because the complicated and long procedure for claiming will harm the hospital. I’m in a dilemma with this condition. Unfortunately, I need to follow the instruction, but manage to help the patient first.” (N 6)

Challenges in Addressing Ethical Issues

Seniority. Senior has a big responsibility as a model, and junior brings new hopes because they are updated with the latest knowledge. However, there are two different perspectives between seniors and juniors, in which juniors feel the senior pressures at work, while seniors think that juniors are too confident.

Juniors expressed this:

“I want to report this to our nurse manager, but I am afraid that my seniors will get angry and complain.” (N 12)

“I tried many times to remind teammate or other healthcare about following the standard, but many times I get trouble from the coordinator or above.” (N 8)

Seniors stated this:

“The senior nurses had the experience doing nursing so long and learned a lot about mistakes. I understand there are bad and good role models, but they can learn from us” (N 10)

“New generation is so confident. They do not care even though seniors try to remind them.” (N 5)

Trust issue. In dealing with ethical challenges, nurses must have excellent teamwork, which requires trust. However, in this study, the trust issue is the problem. The participants state this:

“I’m here as a primary nurse [nurse team leader], I have a bigger responsibility, so when I’m going to delegate an activity to a colleague, it’s a little difficult because my colleagues feel they can’t handle it.” (N 7)

“One time, when I was a staff nurse, after I injected the wrong medicine into patients, my team leader didn’t trust me to do injections when working with her. She will ask for checking many times, or she chose to do it herself even though she did not have the injecting assignment. That’s the lesson I learned when I become a team leader now” (N 5)

Lack of reflection and ethics training. The participants stated that the past mistakes made by the nurses should be discussed in pre or post-conferences during the shifts or in a forum to avoid repeating mistakes in the future. This also should be supported by the hospital to provide nurses with ethics training to raise awareness. Participants stated this:

“It will be beneficial for learning if the past mistakes can be discussed.” (N 6)

“We rarely take part in the training. The hospital said there is no financial support for that. We are encouraged to take the training independently.” (N 2)

“When there was a nurse who injected the wrong medicine, the head nurse instructed team leaders and staff nurses to observe her performance at all shifts. That nurse felt down, and she decided to resign. No reflection after that.” (N 1)

“When the hospital committees solve the problems related to nursing errors or ethical mistakes, they do not spread the solution. Many nurses say they do not know. So, how can we deal with this problem which has persisted for many years?” (N 3)

Discussion

Nurse team leaders face significant challenges when dealing with problems in everyday situations, particularly when it comes to ethical dilemmas involving patients and their families. These dilemmas often arise due to various reasons, such as patient complaints, uncontrolled family conditions, or requests beyond the nurse’s competence (Rainer et al., 2018). To solve such problems, nurse team leaders need to gather facts, step back, consider support from other teams, and stand by their patients, according to our study. Unfortunately, some hospitals may make unethical decisions, highlighting the importance of ethical decision-making in nursing leadership. This finding is linked with two root elements of the ethical sensitivity concept: “being aware” and “responding and reacting to the needs of others,” both of which encompass ethical considerations (Bebeau et al., 1999). Furthermore, ethical sensitivity involves role and moral responsibility, leading to moral reasoning and decision-making, which guide ethical behavior (Lützen et al., 2006).

The task of managing a team of nurses during a shift can be challenging. According to a previous study, nurse leaders struggle to address team members’ conflicts (Wittenberg et al., 2015). Senior nurses are responsible for serving as ethical role models for their junior counterparts, as one of the core competencies of all nurse leaders (Bowles et al., 2018). Nurses can develop and improve their ethical behavior by integrating role modeling, articulating expert practice, reflecting on practice, and providing feedback. However, delegating a significant responsibility to another person can be difficult, as it requires considering their ethical experience and understanding. Our findings show that while senior nurses and team leaders attempt to guide their junior counterparts, the younger nurses may be too confident to accept their advice, similar to a discussion in a previous study (Gunawan & Marzilli, 2022). In contrast, junior nurses may strive to address ethical issues to achieve professional competence and bring new perspectives based on the latest knowledge (Rennó et al., 2018). Despite appearing at odds, both generations share the same ethical goal of protecting patients’ rights. These nurses take an active role in handling challenging ethical problems as part of their professional duties. As such, they deserve support to enhance their learning and ethical competency development (Andersson et al., 2022).

On the other hand, the working environment plays a significant role in shaping the leadership style of nurse leaders. A strict and oppressive environment can lead to nurse turnover, while a healthy and supportive environment can foster a culture of learning and growth (Bove & Scott, 2021; Juanamasta et al., 2021a). According to our study, it is crucial for nurse leaders to provide an environment of learning from their mistakes, group reflections, and cultural support.

It is understandable that ethical dilemmas are common in nursing practice and can be recurrent issues for various reasons. However, nursing theory and practice evolve continuously, offering new solutions to address ethical problems. Therefore, organizations must support ethical education for nurse team leaders through seminars or workshops to enhance their knowledge and skills, especially when supporting new nurses (Andersson et al., 2022; Hemberg & Hemberg, 2020). A lack of support from the hospital can negatively affect the mindset of nurse leaders, leading to unethical decision-making, which can impact nurse and patient outcomes (Juanamasta et al., 2021a). Therefore, fostering an ethical learning environment is critical to promoting ethical behavior and improving patient care.

Implications for Nursing Practice and Hospital Policy

Ethical dilemmas cannot be stopped or avoided, and nurse team leaders have to approach them carefully. They need to consider the nurse’s position and reduce tension by remaining aware and calm. Unethical decisions can occur if they cannot adopt moral reasoning and understanding, leading to unclear nursing roles. The problem arises because of a conflict of interest between the patient and the workplace. Meanwhile, nurse team leaders should unite their team by training seniors as role models and encouraging knowledge-sharing and ethical experiences to establish a positive learning atmosphere. Additionally, the workplace environment is essential in motivating nurses to reflect and learn from ethical dilemma issues or study from mistakes. Finally, an interdisciplinary policy is necessary to avoid blaming individuals when facing ethical problems.

Strengths and Limitations

This study was the first in Indonesia to explore nurse team leaders’ experiences in dealing with ethical dilemmas, making it a valuable contribution. However, the findings could not be generalized, which require further research for confirmation.

Conclusion

Nurse team leaders have a significant responsibility to unite their teams, as a good team can bring good performance and reduce the gap between seniors and juniors. However, they face significant challenges in dealing with patients/families and team members. The strategies for solving the problem include seeking facts, stepping back, considering support, and standing by the patient. Additionally, the working environment and hospital support play an important role that affects the nurse team leader’s character in leading their team.

Acknowledgment

None.

Declaration of Conflicting Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest in this study.

Funding

None.

Authors’ Contributions

Study design: NMNW, IGJ, JT, JY; Data collection: NMNW; Data analysis: NMNW, IGJ, JT; Supervision: JY; Manuscript writing: IGJ, JT; Critical revisions for important intellectual content: NMNW, IGJ, JY, JT. All authors approved the final version of the article to be published and agreed to be accountable for each step of the study.

Authors’ Biographies

Ns. Ni Made Nopita Wati, S.Kep., M.Kep is a Nursing Lecturer at STIKes Wira Medika Bali, Indonesia. Her research interests are leadership and management, legal and ethics in nursing practice, and complementary and alternative medicine.

Ns. I Gede Juanamasta, S.Kep., M.Kep is a Nursing Lecturer at STIKes Wira Medika Bali, Indonesia. His research interests are management, quality nursing care, and well-being.

Jutharat Thongsalab, M.N.S, Dip. PMHN is a Senior Nurse Instructor at the Boromarajonani College of Nursing, Surin, Thailand, and a PhD student at the Faculty of Nursing, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand. Her research interests are mental health, community health, and family nursing.

Assoc. Prof. Jintana Yunibhand, Dip. PMHN, Ph.D is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Nursing, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand. Her research interests are mental health, community health nursing, smoking cessation, leadership and management.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declaration of use of AI in Scientific Writing

Nothing to declare.

References

- Aitamaa, E., Leino-Kilpi, H., Iltanen, S., & Suhonen, R. (2016). Ethical problems in nursing management: The views of nurse managers. Nursing Ethics, 23(6), 646-658. 10.1177/0969733015579309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, H., Svensson, A., Frank, C., Rantala, A., Holmberg, M., & Bremer, A. (2022). Ethics education to support ethical competence learning in healthcare: An integrative systematic review. BMC Medical Ethics, 23(1), 1-26. 10.1186/s12910-022-00766-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arisanti, H., Abidin, Z., & Andriani, R. (2018). Implementation of Professional Nursing Practice Model (MPKP) and its effect on hospital patient satisfaction in Baubau City Hospital. International Journal of Academic Research and Reflection, 5(6), 51-58. [Google Scholar]

- Barkhordari-Sharifabad, M., Ashktorab, T., & Atashzadeh-Shoorideh, F. (2018). Ethical leadership outcomes in nursing: A qualitative study. Nursing Ethics, 25(8), 1051-1063. 10.1177/0969733016687157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebeau, M. J., Rest, J. R., & Narvaez, D. (1999). Beyond the promise: A perspective on research in moral education. Educational Researcher, 28(4), 18-26. [Google Scholar]

- Birkholz, L., Kutschar, P., Kundt, F. S., & Beil-Hildebrand, M. (2022). Ethical decision-making confidence scale for nurse leaders: Psychometric evaluation. Nursing Ethics, 29(4), 988-1002. 10.1177/09697330211065847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonde, J. P., Jørgensen, K. T., Bonzini, M., & Palmer, K. T. (2013). Miscarriage and occupational activity: A systematic review and meta-analysis regarding shift work, working hours, lifting, standing, and physical workload. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 325-334. 10.5271/sjweh.3337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bove, L. A., & Scott, M. (2021). Advice for aspiring nurse leaders. Nursing2022, 51(3), 44-47. 10.1097/01.NURSE.0000733952.19882.55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles, J. R., Adams, J. M., Batcheller, J., Zimmermann, D., & Pappas, S. (2018). The role of the nurse leader in advancing the quadruple aim. Nurse Leader, 16(4), 244-248. 10.1016/j.mnl.2018.05.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1989). Fourth generation evaluation. California: Sage Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Gunawan, J., & Juanamasta, I. G. (2022). Nursing career ladder system in Indonesia: The hospital context. Journal of Healthcare Administration, 1(1), 26-34. 10.33546/joha.2177 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gunawan, J., & Marzilli, C. (2022). Senior first, junior second. Nursing Forum, 57(1), 182-186. 10.1111/nuf.12654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunawan, J., Marzilli, C., & Aungsuroch, Y. (2022). Online ‘chatting’ interviews: An acceptable method for qualitative data collection. Belitung Nursing Journal, 8(4), 277-279. 10.33546/bnj.2252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemberg, J., & Hemberg, H. (2020). Ethical competence in a profession: Healthcare professionals' views. Nursing Open, 7(4), 1249-1259. 10.1002/nop2.501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juanamasta, I. G., Aungsuroch, Y., & Gunawan, J. (2021a). A concept analysis of quality nursing care. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing, 51(4), 430-441. 10.4040/jkan.21075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juanamasta, I. G., Iblasi, A. S., Aungsuroch, Y., & Yunibhand, J. (2021b). Nursing development in Indonesia: Colonialism, after independence and nursing act. SAGE Open Nursing, 7, 23779608211051467. 10.1177/23779608211051467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, C., Babenko-Mould, Y., Evans, M., Wong, C. A., & Kirkwood, K. W. (2019). Conscientious objection and nurses: Results of an interpretive phenomenological study. Nursing Ethics, 26(5), 1337-1349. 10.1177/0969733018763996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lützen, K., Dahlqvist, V., Eriksson, S., & Norberg, A. (2006). Developing the concept of moral sensitivity in health care practice. Nursing Ethics, 13(2), 187-196. 10.1191/0969733006ne837oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parreira, P., Santos-Costa, P., Neri, M., Marques, A., Queirós, P., & Salgueiro-Oliveira, A. (2021). Work methods for nursing care delivery. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 2088. 10.3390/ijerph18042088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2017). Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice (10th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health. [Google Scholar]

- Rainer, J., Schneider, J. K., & Lorenz, R. A. (2018). Ethical dilemmas in nursing: An integrative review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(19-20), 3446-3461. 10.1111/jocn.14542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennó, H. M. S., Ramos, F. R. S., & Brito, M. J. M. (2018). Moral distress of nursing undergraduates: Myth or reality? Nursing Ethics, 25(3), 304-312. 10.1177/0969733016643862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritruechai, S., Khumwong, W., Rossiter, R., & Hazelton, M. (2018). Thematic analysis guided by Max van Manen: Hermeneutic (interpretive) phenomenological approach. Journal of Health Science Research, 12(2), 39-48. [Google Scholar]

- Saad, L. (2022). Military brass, judges among professions at new image lows. Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/poll/388649/military-brass-judges-among-professions-new-image-lows.aspx

- Spence, D. G. (2017). Supervising for robust hermeneutic phenomenology: Reflexive engagement within horizons of understanding. Qualitative Health Research, 27(6), 836-842. 10.1177/1049732316637824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, D., & Stanley, K. (2018). Clinical leadership and nursing explored: A literature search. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(9-10), 1730-1743. 10.1111/jocn.14145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storaker, A., Heggestad, A. K. T., & Sæteren, B. (2022). Ethical challenges and lack of ethical language in nurse leadership. Nursing Ethics, 29(6), 1372-1385. 10.1177/09697330211022415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugianto, K. M. S., Hariyati, R. T. S., Pujasari, H., Novieastari, E., & Handiyani, H. (2022). Nurse workforce scheduling: A qualitative study of Indonesian nurse managers’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Belitung Nursing Journal, 8(1), 53-59. 10.33546/bnj.1735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todres, L., & Wheeler, S. (2001). The complementarity of phenomenology, hermeneutics and existentialism as a philosophical perspective for nursing research. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 38(1), 1-8. 10.1016/S0020-7489(00)00047-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Manen, M. (1990). Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. New York: The State University of New York. [Google Scholar]

- Van Manen, M. (2016). Phenomenology of practice: Meaning-giving methods in phenomenological research and writing (1st ed.). New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wittenberg, E., Goldsmith, J., & Neiman, T. (2015). Nurse-perceived communication challenges and roles on interprofessional care teams. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing, 17(3), 257-262. 10.1097/njh.0000000000000160 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N., Li, M., Gong, Z., & Xu, D. (2019). Effects of ethical leadership on nurses’ service behaviors. Nursing Ethics, 26(6), 1861-1872. 10.1177/0969733018787220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.