Abstract

When an individual or group trauma becomes a shared public experience through widespread media coverage (e.g., mass violence, being publicly outed), sharing a social identity with a targeted individual or group of victims may amplify feelings of personal vulnerability. This heightened perceived threat may draw people to engage with trauma-related media because of increased vigilance for self-relevant threats, which can, in turn, amplify distress. We studied this possibility among two U.S. national samples following the 2016 Pulse nightclub massacre in Orlando, FL (N = 4675) and the 2018 Dr. Christine Blasey Ford and Judge Brett Kavanaugh Supreme Court Senate hearings (N = 4894). Participants who shared LGBT or Hispanic identities with Pulse massacre victims reported greater exposure to massacre-related media and acute stress. Participants who shared Dr. Blasey Ford’s identities as a victim of interpersonal violence and a Democrat reported more hearings-related media exposure and acute stress. Indirect effects of shared single identity on acute stress through self-reported event-related media exposure emerged in both studies. Results for sharing dual identities with victims were mixed. These findings have implications for media use and public health.

Subject terms: Psychology, Human behaviour

Introduction

Traditional and social media frequently disseminate news of group-based traumas (e.g., terrorist attacks, mass shootings) widely. With increasing frequency, graphic detail, and instantaneous reporting, the negative consequences of exposure to media coverage of these events are demonstrated in two decades of correlational and prospective research1–11. For example, exposure to media coverage of trauma was associated with acute stress, posttraumatic stress, and depression following the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks4–8, 1995 Oklahoma City bombing9, 2002 Washington D.C. sniper shootings10, and 2013 Boston Marathon bombings11. Thus, media coverage of traumatic events may transmit distress to entire populations beyond those locally affected by it. Considering the breadth and depth of exposure to these events provided by modern media, it is important to understand who might be vulnerable to such media exposure and its negative psychological effects.

Collective stressors frequently occur among homogeneous social groups. For instance, victims of the 2017 Route 91 concert mass shooting in Las Vegas, Nevada were predominantly country music fans, the 2018 Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania synagogue shooting victims were Jewish, and the 2019 Christchurch massacre victims in New Zealand were Muslim. As the trauma is broadcast to people around the world, some may identify with the targeted social groups, placing them at increased risk for distress. Personal identities are the unique aspects of the self that individuate a person from others12,13. Social (collective) identities are depersonalized perceptions of the self in terms of social groups, where the self and social ingroup members become interchangeable13. People often come to identify with a group by incorporating the group’s identity into their self-concept and attaching emotional significance to that group’s membership14,15. When made contextually salient, social identities can be used as a lens through which to interpret information, guide behavior, and experience emotion14–21. Hence, an attack on one’s ingroup may be perceived as an attack on oneself, leading to an identity-congruent response such as feelings of anxiety and threat of vulnerability to a similar experience. Indeed, prior research suggests that individuals who share similarities with trauma victims report more depression and distress22–26.

However, social identities are more than just perceived similarities. Social identities extend one’s sense of self to ingroup members such that consequences for an individual group member are psychologically and emotionally tied to consequences for other ingroup members27,28. Moreover, social identities can be based on shared experiences rather than physical features, and this is especially true for more intense shared experiences. Sharing similar experiences in war, for example, helps mold soldiers’ bonds into the social identity of veterans27,28. Two veterans need not share physical attributes, nor even have been in the same war, to share the emotional and psychological bond that comes with being a veteran. They are treated by people the same way, such as with particular deference, and this helps further consolidate their identification with the group. They also have access to the same social identity-specific resources, like veterans' benefits and organizations. Furthermore, being a veteran can be both a personal identity (i.e., it is what is unique about an individual across most social environments) and a social/collective identity (i.e., it is what emotionally and psychologically connects the individual to ingroup members in a way that blurs perceptions of the self and ingroup others). Given that social groups function, in part, to promote identification among members29 and can lead to experiencing group-congruent emotions20,21, those who share social identities with victims of traumatic experiences that are broadcast widely may share their feelings of threat, anxiety, and distress.

A growing body of research over the past decade suggests that social identities shape people’s physiological and psychological responses to threat27–36. The social identity approach to clinical and health psychology recognizes that people do not just experience and express attitudes, emotions, and behaviors as individuals in a physical environment, but also as group members in a social environment27,28,35,36. However, this work has largely focused on the role of single shared social identities in direct experiences of trauma, leaving unanswered whether sharing multiple social identities with people who have experienced a publicly broadcasted trauma (e.g., mass shooting, being outed) is associated with greater distress following that event.

Moreover, when a person or group’s trauma is shared widely through the media, individuals who share identities with the trauma victim(s) may also be at risk of distress indirectly from increased exposure to event-related media coverage. Individuals who feel threatened or anxious have shown an attentional bias toward threatening stimuli37,38, and threatening visual stimuli activate fear and capture attention39, especially when relevant to the self40,41. Therefore, media coverage of trauma—whether a personal or collective experience—may be especially attention-grabbing for people who share the social identities of the victims. Consequently, victims’ ingroup members may turn to event-related media coverage for information to mitigate feelings of anxiety, ambiguity, and uncertainty42. Yet, exposure to this media coverage may have the opposite effect by increasing, rather than decreasing, distress1–11,43. The present research adds to the social, political, and health psychology literature by examining—among two large U.S. national samples—the roles of shared social identities in media exposure and distress following two public events in the U.S. where the trauma was widely disseminated by the media.

2016 Orlando Pulse nightclub massacre

On June 12, 2016, a lone gunman entered Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida, and opened fire, injuring 53 and killing 49 people. At the time, the attack was the largest mass shooting in U.S. history. However, it was a unique event in another respect: the victims were predominantly lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT) and Hispanic. On the evening of the attack, Pulse, an LGBT-oriented nightclub, hosted a Latin-themed night as part of LGBT Pride month celebrations. As a result, approximately 90% of the victims were both LGBT and Hispanic44.

Both LGBT and Hispanic individuals tend to be disadvantaged in the U.S., and social identities are not experienced independently of each other. A multiple-identities approach states that the negative impact of belonging to more than one disadvantaged social identity has multiplicative repercussions for negative psychological experiences45,46. Research that focuses on a single identity may not fully capture experiences produced from belonging to multiple social groups. For instance, individuals who identify as both LGBT and Hispanic may experience compounded effects of racism in their LGBT communities and heterosexism in their Hispanic communities. We investigated the roles of LGBT and Hispanic identities in Americans’ reactions to the Pulse nightclub attack, and how the interaction of these two identities might be related to greater negative psychological responses. We hypothesized that:

Participants who share the salient identities of the Pulse nightclub massacre victims (i.e., LGBT [n = 287] or Hispanic [n = 478]), would report greater exposure to media coverage about the massacre and greater acute stress than non-LGBT and non-Hispanic participants, respectively,

Participants who identify as both LGBT and Hispanic (n = 50) would report significantly greater Pulse massacre-related media exposure and greater acute stress than those who identify as one or neither identity, and

There would be indirect effects of LGBT and Hispanic identities, and their interaction, on acute stress through self-reported Pulse nightclub massacre media exposure.

Participants consisted of N = 4675 panelists from GfK KnowledgePanel, an independent survey research company that uses addressed-based sampling to randomly sample and recruit participants across the U.S. Panelists received free internet or, if already web-enabled, compensation for their participation. Data collection began five days after the Pulse nightclub massacre on Friday June 17, 2016, and lasted until Friday July 22, 2016. Participants reported the average daily number of hours they watched or listened to media coverage about the shooting in the days following the massacre for five types of media sources, including television, radio, online news sources, pictures and/or videos on social media, and news or text updates on social media. Participants also reported their distress about the massacre on a standardized multi-item measure of acute stress47. Age, gender, education, employment status, marital status, prior mental health diagnoses, and direct exposure to the Pulse nightclub shooting were included in the models as covariates. Sexual orientation, ethnicity, mental health, and demographic covariates were collected upon entry into the GfK KnowledgePanel prior to the Pulse nightclub shooting.

Results

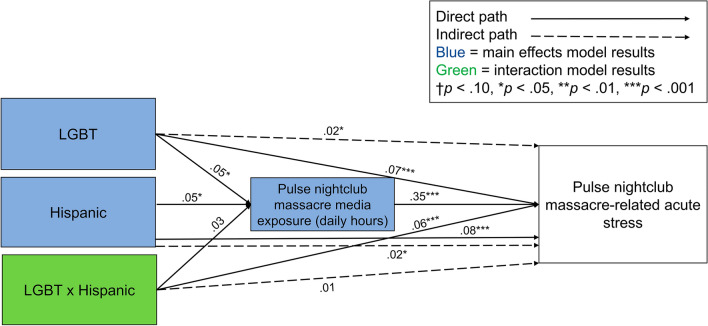

Sample descriptive statistics and full results are presented in Supplementary Tables 1–5. A path model was constructed predicting acute stress from LGBT and Hispanic identities with indirect paths through self-reported media exposure, controlling for covariates (Fig. 1). The model was fit with a full-information maximum likelihood approach and demonstrated good fit, χ2 (3) = 5.01, p = 0.171, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.012, 95% confidence intervals (CI) [< 0.001, 0.030], p = 1.00, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.998, Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) = 0.976, coefficient of determination (CD) = 0.159 (Supplementary Table 2). Supporting our first hypothesis, participants who identified as LGBT (β = 0.05, standard error (SE) = 0.02, 95% CI [0.01, 0.08], p = 0.012) or Hispanic (β = 0.05, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [0.01, 0.08], p = 0.012) reported significantly greater massacre-related media exposure than non-LGBT and non-Hispanics, respectively. This suggests that sharing a social identity with victims of trauma is associated with increased self-reported event-related media exposure. Also as hypothesized, participants who identified as either LGBT (β = 0.07, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [0.04, 0.11], p < 0.001) or Hispanic (β = 0.08, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [0.05, 0.12], p < 0.001) reported significantly greater massacre-related acute stress than non-LGBT and non-Hispanics, respectively. This suggests that sharing a social identity with victims of trauma is associated with increased risk of distress.

Figure 1.

Path models predicting Pulse nightclub massacre-related acute stress from prior self-reported LGBT identity and self-reported Hispanic identity (blue = main effects model), and LGBT × Hispanic identity interaction (green = interaction model). Both models included self-reported average daily hours of Pulse massacre-related media exposure as a mediator and controlled for covariates. Exogenous variables were allowed to correlate, and the models were fit with a full-information maximum likelihood approach.

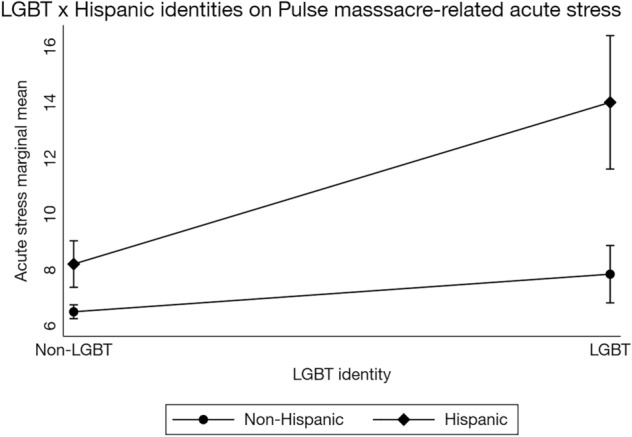

The same path model was repeated with the addition of a LGBT × Hispanic identity interaction term (Fig. 1) to capture the potential for additive effects of identifying with both groups. This model demonstrated good fit, χ2 (3) = 4.94, p = 0.176, RMSEA = 0.012, 95% CI [< 0.001, 0.030], p = 1.00, CFI = 0.998, TLI = 0.975, CD = 0.165 (Supplementary Table 4). Our second hypothesis received mixed support. The interaction between LGBT and Hispanic identities was not significantly associated with reported Pulse massacre-related media exposure (β = 0.03, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [.− 0.01, 0.08], p = 0.123). It was, however, associated with acute stress (β = 0.06, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [0.02, 0.10], p = 0.001; Fig. 2), such that participants who identified as both LGBT and Hispanic reported greater acute stress than those who identified as only one or neither of these identities.

Figure 2.

Interaction between LGBT and Hispanic identities on Pulse nightclub massacre-related acute stress, controlling for covariates. Stata 16 does not allow for factor notation using the sem command. Thus, this interaction plot was generated using the regress command with factor notation among a subset of respondents with complete data (n = 3001). The regression equation used to generate this plot was identical to the regression equation used in the full structural equation model. Although the error estimates differ slightly, this simpler model replicates the interaction in the structural equation model. Bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Acute stress ranged from 0 to 56.

Consistent with prior research1–11, there was a significant association between self-reported Pulse massacre-related media exposure and acute stress (β = 0.35, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [0.32, 0.38], p < 0.001). There were also small, significant indirect effects of LGBT (β = 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.003, 0.03], p = 0.013) and Hispanic (β = 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.004, 0.03], p = 0.012; Supplementary Table 3) identities on acute stress through self-reported massacre-related media exposure, supporting our third hypothesis. However, there was no significant indirect effect of LGBT × Hispanic identities on acute stress (β = 0.01, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [− 0.003, 0.03], p = 0.124; Fig. 2; Supplementary Table 5).

Results demonstrate that sharing social identities with trauma victims is associated with increased risk of event-related media exposure and distress. To conceptually replicate and extend these findings, we conducted a second study investigating the roles of shared social identity and self-reported media exposure in acute stress following a politically-charged event where a personal trauma was publicly shared: the 2018 Dr. Christine Blasey Ford and Judge Brett Kavanaugh Senate hearings prior to confirmation of Judge Kavanaugh to the U.S. Supreme Court.

2018 Dr. Blasey Ford and Judge Kavanaugh U.S. Senate hearings

On July 9, 2018, Judge Brett Kavanaugh was nominated to the U.S. Supreme Court to replace retiring Justice Anthony Kennedy. Three weeks later, Dr. Christine Blasey Ford, a psychology professor in California, sent a letter to Senator Dianne Feinstein, a Democrat on the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee, asserting that Judge Kavanaugh sexually assaulted her in high school. On September 27, 2018, millions of Americans watched and listened as Dr. Blasey Ford and Judge Kavanaugh testified before the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee. While the hearings were not traumatic in the same way as the Pulse nightclub shooting, where a group was intentionally targeted and the carnage was spread across news media in the immediate aftermath, the hearings involved an individual recounting a past personal traumatic experience in great detail. Moreover, the hearings were widely disseminated live across traditional and social news media platforms, potentially retraumatizing survivors of interpersonal assault. Thus, we consider the hearings to be a publicly shared trauma experienced by a large group of people that was broadcast globally via news media.

This event may have been particularly distressing for people who shared social identities with Dr. Blasey Ford as a woman and/or as a survivor of interpersonal violence. Social identities are more than shared biological characteristics; they also emerge from shared experiences, particularly traumatic ones (e.g., refugees, orphans, veterans). The social identity model of traumatic identity change (SIMTIC) posits that sharing the experiences of trauma can engender a new social identity (e.g., as a victim) in a way that gives meaning to the trauma and an emotional connection to other victims35,36. This new social identity, such as a survivor of interpersonal violence, may provide benefits like a shared sense of belonging and connection to others that aids with trauma recovery and resilience 35. However, it also provides a new lens through which to perceive and interpret events and feel identity-congruent emotions, with potentially detrimental effects when the trauma-based identity is either targeted or re-experienced. Thus, the widely broadcast details of Dr. Blasey Ford’s assault could lead people who identify as victims of interpersonal violence to experience intrusive thoughts and rumination, which can have downstream consequences for the severity of their posttraumatic stress48,49.

More broadly, women may have been at higher risk for distress given that they are more likely to experience sexual assault50,51 and the testimonies made such attacks a salient issue52. A third salient identity during the hearings was political identity. The hearings occurred during a highly charged standoff between Democrats and Republicans where the successful appointment of Judge Kavanaugh would tip the balance of power in the Supreme Court to favor Republicans, who already controlled the executive and half of the legislative branches of government. Since Dr. Blasey Ford initially came forward with her story to a Democratic Senator, she was portrayed by some Republicans as a political tool used to block their Supreme Court advantage. Hence, Democrats may have been more distressed, not only from identifying with Dr. Blasey Ford as a fellow Democrat re-experiencing a traumatic memory but also because the outcome of the hearings could tip the balance of power by giving the opposing political party a coveted seat on the Supreme Court. We hypothesized that:

Participants who share the salient identities of Dr. Blasey Ford (i.e., interpersonal violence victim [weighted n = 2298], woman [weighted n = 2543], Democrat [weighted n = 2248]), would report greater exposure to media coverage about the Senate hearings and greater acute stress than non-victims of interpersonal violence, men, and Republicans, respectively,

Participants who identify as both interpersonal violence victim and woman (weighted n = 1525), interpersonal violence victim and Democrat (weighted n = 1082), or woman and Democrat (weighted n = 1175) would report significantly greater Ford and Kavanaugh hearings-related media exposure and greater acute stress than those who identify as one or neither of those identities, and

There would be indirect effects of interpersonal violence victim, female, and Democrat identities, and their two-way interactions, on acute stress through self-reported Dr. Blasey Ford and Judge Kavanaugh Senate hearings-related media exposure.

We surveyed a probability-based nationally representative sample of N = 4894 from the NORC AmeriSpeak panel, a private survey panel that uses address-based sampling methods to randomly sample and recruit from U.S. households in exchange for compensation. Data collection began the morning of Tuesday October 2, 2018—5 days after Dr. Blasey Ford and Judge Kavanaugh’s testimonies to the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee and four days before the final confirmation vote—and continued until mid-day Friday October 12, 2018. Participants reported their average daily hours of exposure to media coverage of the hearings using a similar measure as Study 1 and reported their acute stress to the hearings using the five-item Primary Care PTSD screener53 for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5)54. Participants also reported whether they were a victim of sexual assault, rape, and/or intimate partner violence; upon entry into the AmeriSpeak panel before the Senate hearings respondents had reported their gender, political identity, demographics, and mental health status. A binary victim of interpersonal violence identity variable was created with participants who answered yes to being a victim of sexual assault, rape, and/or intimate partner violence compared to participants who responded no to all three of these. Data were weighted to account for the probability of selection into the sample and differences between our sample and U.S. Census benchmarks.

Results

Sample descriptive statistics and full results are presented in the Supplementary Tables 6–10. A path model was constructed predicting acute stress from victim of interpersonal violence, gender, and political party identities with indirect paths through self-reported media exposure, controlling for covariates (Fig. 3). The model was fit with a full-information maximum likelihood approach, CD = 0.191 (Supplementary Table 7). Supporting our first hypothesis, participants who shared Dr. Blasey Ford’s identity as a victim of interpersonal violence (β = 0.13, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [0.08, 0.18], p < 0.001) or as a Democrat (β = 0.10, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [0.05, 0.14], p < 0.001) reported significantly greater exposure to media coverage of the hearings than non-interpersonal violence victims and Republicans, respectively. Counter to our hypothesis, women reported significantly less Ford and Kavanaugh hearings media exposure than men (β = − 0.08, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [− 0.13, − 0.04], p < 0.001). However, supporting the first hypothesis, participants who identified as a victim of interpersonal violence (β = 0.23, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [0.19, 0.27], p < 0.001), woman (β = 0.04, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [0.01, 0.08], p = 0.024), or Democrat (β = 0.10, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [0.06, 0.14], p < 0.001) reported significantly greater Ford and Kavanaugh hearings-related acute stress than non-interpersonal violence victims, men, and Republicans, respectively.

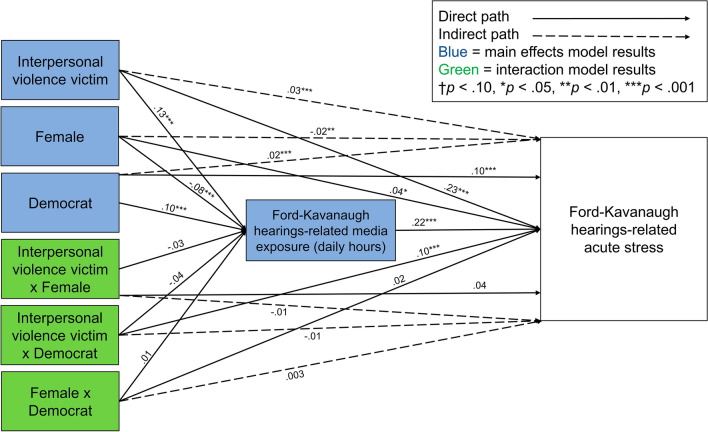

Figure 3.

Path models predicting Ford and Kavanaugh hearings-related acute stress from prior self-reported interpersonal violence victim, gender, and political identities (blue = main effects model), and interpersonal violence victim × gender, interpersonal violence victim × political, and gender × political identity interactions (green = interaction model). Both models included self-reported average daily hours of Ford and Kavanaugh hearings-related media exposure as a mediator and controlled for covariates. Exogenous variables were allowed to correlate, and the models were fit with a full-information maximum likelihood approach.

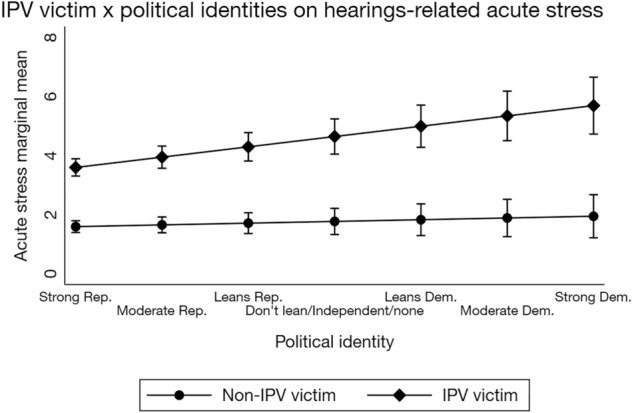

The same path model was repeated with the addition of interpersonal violence victim × gender, interpersonal violence victim × political party identity, and gender × political party identity interaction terms, using a full-information maximum likelihood approach, CD = 0.199. (Fig. 3; Supplementary Table 9). Our second hypothesis received mixed support. None of the dual identity interactions were significantly associated with self-reported Ford and Kavanaugh hearings-related media exposure. Of the three dual identity interactions, interpersonal violence victim × Democrat was significantly associated with acute stress (β = 0.10, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [0.05, 0.16], p < 0.001; Fig. 4) such that sharing these two identities with Dr. Blasey Ford was associated with greater distress than sharing a single or neither identity.

Figure 4.

Interaction between interpersonal violence victim and political identities on Ford and Kavanaugh hearings-related acute stress, controlling for covariates. Exogenous variables were allowed to correlate, and the model was fit with a full-information maximum likelihood approach. Stata 16 does not allow for factor notation using the sem command. Thus, the interaction plot was generated using the regress command with factor notation and weighting among a subset of respondents with complete data (n = 4828). The regression equation used to generate this plot was identical to the regression equation used in the full structural equation model. Although the error estimates differ slightly, this simpler model replicates the interaction in the structural equation model. Rep. = Republican, Dem. = Democrat, IPV = interpersonal violence. Bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Acute stress ranged from 0 to 20.

Consistent with prior research1–11,43 and Study 1, self-reported exposure to media coverage of the Ford and Kavanaugh hearings was significantly associated with acute stress (β = 0.22, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [0.17, 0.27], p < 0.001), and there were small, significant indirect effects of interpersonal violence victim (β = 0.03, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.02, 0.04], p < 0.001), male gender (ꞵ = − 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [− 0.03, − 0.01], p = 0.001), and Democrat (β = 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.01, 0.03], p < 0.001; Supplementary Table 8) identities on acute stress through self-reported media exposure. Counter to the third hypothesis, there were no significant indirect effects of the three dual identity interaction terms (Supplementary Table 10).

Results from Study 2 partially replicate Study 1 in that sharing a social identity with victims of trauma was associated with increased self-reported event-related media exposure and distress. However, results about sharing Dr. Blasey Ford’s gender identity were more nuanced. Men reported greater hearings-related media exposure than women, and there was a significant indirect effect of male identity on acute stress through reported media exposure. Nonetheless, results support the proposition that sharing a social identity with trauma victims is associated with both increased self-reported exposure to trauma-related media coverage and acute stress, including in contexts where personally experienced traumas are publicly shared via the media.

Discussion

In two different contexts where traumatic experiences were broadcast widely by news media, people who shared social identities with victims reported more event-related media exposure and distress. Results from both studies reported here are consistent with prior findings that self-reported exposure to media coverage of trauma1–11,43, and sharing social identities with trauma victims22–28,31–36, are associated with increased distress. Specifically, participants in our national sample in Study 1 who shared either LGBT or Hispanic identities with the Pulse nightclub shooting victims reported greater shooting-related media exposure and greater acute stress than people who shared neither identity. There was also an indirect effect of shared social identity on acute stress through self-reported media exposure, suggesting that media exposure explained, in part, the association between shared social identity with the victims and distress. These findings were replicated in a different context that similarly involved widespread media dissemination of a traumatic experience. During the Dr. Blasey Ford and Judge Kavanaugh U.S. Senate hearings, participants who shared any one of three social identities (as a woman, survivor of interpersonal violence, and Democrat) with a woman who recounted her traumatic experience live in great detail also reported greater acute stress. Results for self-reported media exposure were largely supported, where sharing four out of the five social identities examined across the two studies significantly predicted greater self-reported event-related media exposure.

Although we found consistent evidence for the hypothesized association between sharing a single social identity with trauma victims and acute stress, results were less clear for sharing dual social identities. In the aftermath of the Pulse nightclub shooting, sharing both LGBT and Hispanic identities significantly predicted acute stress. However, of the three social identity interactions tested in the Ford and Kavanaugh hearings study, only the interaction between interpersonal violence victim and Democrat significantly predicted acute stress. In both studies, there was no association between sharing dual social identities and self-reported media exposure.

One potential reason for these mixed dual identity results is because these were qualitatively different events. The Pulse nightclub shooting was a collective trauma where an individual targeted an underrepresented group to instill terror. The most salient identities of the attack victims were clear because they were related to the motive behind the attack. The intentionality behind the attack is important because it erodes trust in others among social ingroup members of the victims, leaving them feeling disconnected and betrayed27,55.

On the other hand, the Dr. Blasey Ford and Judge Kavanaugh hearings involved widespread media coverage of a personal traumatic event where a survivor of interpersonal violence recounted her traumatic experience amidst a highly polarized political environment. Indeed, although this event consisted of an individual recounting her traumatic experience in great detail, it is a trauma that is commonly experienced across the world, particularly by women. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 1 in 3 women worldwide have been subjected to either physical and/or sexual intimate partner or non-partner violence in their lifetime56. In the U.S., data from the Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention (CDC) National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS) show that about 1 in 3 women, and 1 in 4 men, reported having experienced severe physical violence from an intimate partner in their lifetimes56. Moreover, about 1 in 5 women and 1 in 13 men reported having experienced sexual violence by an intimate partner57. Thus, publicly and widely sharing the details of Dr. Blasey Ford’s assault live on global news created a moment of shared trauma-related experience, especially for those who shared an identity as a survivor of interpersonal violence.

Moreover, with major political implications at stake, the narrative surrounding the facts of Dr. Blasey Ford’s assault became polarized, leading to politicized perceptions of victimhood. For instance, as Judge Kavanaugh expressed outrage during his testimony, he claimed to be the victim of a false sexual assault allegation—a political weapon to block his appointment to the Supreme Court58. By blurring the lines of gender victimhood with an event where the trauma is recounted and the facts more easily debated (as opposed to seeing news media scenes of ongoing death and destruction), the cues for which gender should feel most threatened were less clear (e.g.,52). What was clear, however, was that the motivation behind the hearings was directly tied to interpersonal violence, making interpersonal violence survivorship a salient identity. It was also clear that if Judge Kavanaugh was successfully appointed to the Supreme Court, the balance of power would shift in favor of Republicans, making the threat that the outcome of the hearings poses to Democrats salient. Greater attention to psychological experiences engendered by multiple impacted social identities can inform public health research on vulnerable subpopulations58.

More broadly, our findings suggest that people use media in line with their social identities. There is scant research on how social identities drive media engagement, and how such engagement might influence identification with social groups. Some have theorized that people use media that portray their social identities in a positive light60,61. However, our findings suggest engaging with identity-related media may be detrimental in the context of trauma. This is especially true considering that exposure to trauma-related media can further amplify distress1–11, a finding we replicated in both studies.

Our results have implications for media engagement and public health. Media organizations should consider limiting sensational coverage of traumatic events, as it may promote distress among people who identify with victims. Likewise, the general public should be made aware of the negative repercussions of trauma-related media exposure and the increased likelihood of engaging with it when it is self-relevant. Moreover, to protect vulnerable populations following trauma, future research should test the efficacy of targeting recovery messages and treatments like group-based emotion regulation62 toward members of victims’ ingroups.

Limitations

Although identities in both studies were measured before each event, the correlational nature of our results restricts our ability to claim causality. Thus, we are unable to discern whether identification with trauma victims motivates exposure to event-related media coverage or exposure to event-related media coverage motivates identification with victims (e.g.,63). The relation may also be bidirectional, whereby those who identify with trauma victims experience distress, which in turn motivates attention to media, which further increases identification and distress3. Additional research is needed to better understand these links and potential interventions that can ameliorate negative consequences for public health.

Our studies were also limited in not directly measuring the degree to which participants identify with the victims. Rather, we inferred identification from demographic reporting before both events, which may have led to the small effects we observed. Small effects, however, can be impactful when repeated over time64. For instance, results from the present studies suggest that exposure to media coverage of a single instance of police brutality involving a Black American victim may have a small, yet significant, identification effect on Black Americans’ mental health around the country65,66, but the repetition of such events may have an even larger and longer-lasting negative psychological impact. This contradicts research suggesting that minority identification can buffer the negative effects of prejudice30. Future research should explore the longitudinal effects of shared social identities on media exposure and distress in the context of publicly shared traumas.

Additionally, we did not explore how some shared identities are more easily hidden (e.g., LGBT) than others (e.g., Hispanic), which may impact quality of life67. Our results showed nearly equal acute stress effect sizes between concealable (LGBT, interpersonal violence victim, political affiliation) and non-concealable (race/ethnicity, gender) identities. However, the concealability of shared social identities might matter for how quickly people respond to traumas spread publicly via news media (e.g., victims’ identities may be more immediately obvious as an event occurs when the identities are non-concealable). Future research should investigate whether this difference affects psychological outcomes following traumatic events.

We also note that our measure of event-related media exposure was self-report, which may be limited by biased time estimation. It is possible that participants either misremembered how much time they spent exposed to event-related media, or that their personal motivations to either engage or not with news coverage of the event biased how much time they thought they spent exposed to such media coverage. For instance, someone morally outraged by aspects of the Dr. Blasey Ford and Judge Kavanaugh hearings might overestimate how much time they spent exposed to hearings-related media coverage, or someone apathetic to the event might underestimate such exposure. Though this remains a possibility, our analyses controlled for several variables that may lead to spurious correlations between media exposure and acute stress, such as prior mental health diagnosis, employment status, education, and income.

Another limitation of our findings is that we may have been underpowered to detect statistical significance, particularly in Study 1. Though the sample was large with over 4000 participants, there were only n = 50 who identified (prior to the study) as both LGBT and Hispanic. Despite the low subsample size, we still observed a significant dual identity interaction on Pulse massacre-related acute stress. Yet, lack of statistical power may explain why there was no significant interaction on self-reported massacre-related media exposure and no significant dual identity indirect effects on acute stress through reported media exposure. That we replicated this pattern of a dual identity interaction on acute stress but not reported media exposure nor with indirect effects in Study 2, where we had much larger dual identity subsamples (ns = 1082–1525), suggests that power may not have been an issue in Study 1. Future research should consider using more targeted quota sampling of underrepresented dual identities to improve statistical power in investigating the role of shared social identities in response to publicly shared traumas.

A final limitation of Study 1 is that the sample completed the survey from 5 days to approximately one month after the Pulse massacre. It is possible that, as the massacre got farther away from recent memory, people would report less stress and less massacre-related media exposure. To address this limitation, we re-ran the models including survey completion date as a covariate and found that there was no significant association with either self-reported media exposure or acute stress (ps > 0.100). Indeed, media coverage of the attack, which was the deadliest mass shooting in U.S. history at the time, was extensive and ongoing, with major news outlets providing updates and analysis on the investigation, the victims, and the response from the community and political leaders. Additionally, the story generated significant debate and discussion about issues such as gun control, LGBT rights, and terrorism, which further contributed to its continued coverage in the media. While the intensity of the coverage gradually decreased over time, news outlets continued to report on the aftermath of the shooting, including the trial of the shooter's wife, the ongoing investigation into the incident, and the community's efforts to recover and heal from the tragedy. Time since event was less likely an issue for the Dr. Blasey Ford and Judge Kavanaugh hearings since the survey was administered in the days following the hearings and prior to the final Senate confirmation vote.

Conclusions

Belonging to social groups can be beneficial in providing resources and social support when experiencing stress30,34,68,69, and this benefit can be accessed today from geographically remote locations. However, the transmission of ingroup members’ experiences can also be detrimental, particularly when such experiences are traumatic. We demonstrate that sharing social identities with trauma victims is associated with self-reported trauma-related media exposure and distress. Thus, social identities may be a double-edged sword when the trauma is spread widely through the media in that they engender a sense of belonging and meaningful connections with others, but also a shared sense of distress when the identities are targeted and the traumatic experience is broadcast widely.

Materials and methods

2016 Orlando Pulse nightclub massacre

Participants were recruited as the sixth wave of a longitudinal population-based study investigating Americans’ psychological reactions to collective traumas, which began shortly after the Boston Marathon bombings11. The initial sample was drawn from the GfK KnowledgePanel (with oversampling in metropolitan Boston and New York City), a nationally representative panel of U.S. residents recruited using address-based sampling methods. The survey was fielded from June 17-July 22, 2016 to 6098 people, of whom 4822 responded during the fielding period and 4675 provided usable data, yielding a 76.66% completion rate. Despite recruiting a national sample, sampling weights were not applied in Study 1 because the U.S. Census does not track sexual orientation nor transgender identity and thus does not have a population benchmark for comparison. Participants received free internet or compensation. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations and all procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of California, Irvine. All participants provided informed consent.

Measures

Acute stress

Acute stress symptoms related to the Pulse nightclub massacre were assessed using the Acute Stress Disorder Scale 547, which measured the frequency of experiencing 14 symptoms of acute stress from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5)54 related to the Pulse nightclub massacre (e.g., “Do you try to avoid thinking about the Orlando mass shooting?”). Participants indicated the extent to which they experienced symptoms using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from not at all (0) to a great deal (4). Responses were summed, ranging from 0 to 56, α = 0.88.

Self-reported media exposure

Participants reported the average daily number of hours they watched or listened to media coverage about the Orlando mass shooting in the days after it happened. Using a checkbox grid format, participants indicated the number of hours from 0 to 11 + for five media sources, including television, radio, online news sources (e.g., CNN, Yahoo, NYTimes.com, etc.), pictures and/or videos on social media (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, etc.), and news or text updates on social media (Twitter, Reddit, etc.). This format allowed us to capture simultaneous modes of event-related news media exposure, such as scrolling through social media while watching television. Total average daily hours of media exposure were summed across all five media types to create an index of media exposure. Hours were capped at 18 (3 standard deviations above the mean) to account for outliers.

LGBT identity

Upon entry into the GFK KnowledgePanel, participants reported several demographic characteristics, including transgender identity and sexual orientation. Participants indicated whether they are cisgender (n = 4388) or transgender (n = 41), then identified as straight (i.e., heterosexual; n = 4181), gay or lesbian (n = 127), bisexual (n = 88) or something else (i.e., other; n = 39). A dichotomous variable was created comparing cisgender heterosexuals (non-LGBT, n = 4125) to those who identified as transgender, gay, lesbian, bisexual, or something else (LGBT, n = 287). Subsample sizes differ from the sample total due to missing data. To account for this, our analysis used full-information maximum likelihood estimation.

Hispanic identity

Participant ethnicity was also collected upon entry into the GfK KnowledgePanel before the Pulse nightclub attack. Participants reported whether they were Black non-Hispanic (n = 387), Hispanic (n = 478), other non-Hispanic (n = 308), or White non-Hispanic (n = 3502). Ethnicity was recoded into two categories: non-Hispanic (n = 4197) and Hispanic (n = 478).

Other demographics

Age, gender, education, household income, employment status, marital status, strength of political party identity and U.S. Census Bureau designated geographic region were collected upon entry to the KnowledgePanel prior to the Pulse nightclub massacre.

Mental health diagnoses

Mental health status was assessed as part of a comprehensive health assessment upon entry into the GfK KnowledgePanel. Participants were given a list of physical and mental health ailments and indicated whether they had ever been diagnosed by a physician for each. Responses were recoded to three levels: no diagnosis of anxiety or depression, diagnosis of anxiety or depression, and diagnoses of both anxiety and depression.

Direct Pulse massacre exposure

Participants reported whether they or someone they knew was at or near the site of the shooting as either no or yes.

Covariates

Covariates included age, gender, education, household income, employment status, marital status, strength of political party identity, U.S. Census Bureau designated geographic region, prior self-reported mental health diagnoses, and direct exposure to the Pulse nightclub massacre.

Analytic strategy

Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 1670. Summary scores were created for self-reported Pulse massacre-related media exposure and acute stress to account for variability71, and categorical variables were dummy coded. Two path models were constructed, one with LGBT identity and Hispanic identity main effects and another adding an LGBT × Hispanic identity interaction term, predicting acute stress, controlling for covariates. Self-reported media exposure was specified as a mediator between predictor variables and acute stress. Exogenous variables were free to correlate, and the models were fit with a full-information maximum likelihood approach to account for missing data.

2018 Dr. Blasey Ford and Judge Kavanaugh U.S. Senate hearings

Participants in Study 2 were recruited from the NORC AmeriSpeak panel as part of a study investigating the psychological impact of the Dr. Blasey Ford and Judge Kavanaugh hearings on Americans. Data collection began the morning of October 2, 2018—5 days after Dr. Blasey Ford and Judge Kavanaugh’s testimonies to the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee and four days before the final confirmation vote—and continued until mid-day October 12, 2018. Among the 8237 panelists invited to participate, 4894 completed the survey during the fielding period, yielding a 59.41% completion rate. Data were weighted to account for probability of selection into the AmeriSpeak panel and demographic differences in our sample compared to U.S. Census benchmarks. All participants were compensated for their time. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations and all procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of California, Irvine. All participants provided informed consent.

Measures

Acute stress

Acute stress symptoms related to the Dr. Blasey Ford and Judge Kavanaugh hearings were assessed using the Primary Care PTSD screener for the DSM-551 with a modified scale format. Participants indicated the extent to which they experienced five symptoms of acute stress as a result of the news story about the Senate Hearings (e.g., “Had nightmares about sexual or interpersonal violence or thought about it when you did not want to?”) using a 5-point Likert-type scale from never (0) to all the time (4). Responses were summed, ranging from 0 to 20, α = 0.87.

Self-reported media exposure

Daily hours of exposure to hearings-related media coverage were measured using similar items and format as Study 1. Participants indicated the number of hours, on average, in the past week they spent reading, watching, and/or listening to media coverage of the Judge Kavanaugh and Dr. Ford news story from 0 to 11+ for television, radio or podcasts, online news sources (CNN, Yahoo, NYTimes.com, etc.), news or text updates on social media (Twitter, Facebook, Reddit, etc.), and print news sources (newspaper, magazines). Hours were summed across the five media types and capped at 25 (3 standard deviations above the mean) to account for outliers.

Interpersonal violence victim identity

Participants indicated whether they were ever a victim of sexual assault, rape, or intimate partner violence. Participants who answered yes to any of the following three items: “Has anyone ever touched or felt private areas of your body under force of threat or forced you to touch or feel someone else’s private areas?” (weighted n = 1491), “Have you ever had sexual relations under force or threat?” (weighted n = 832), and “Have you ever been hit or pushed by a partner or spouse?” (weighted n = 1553), were coded as a victim of interpersonal violence (weighted n = 2298), and participants who answered no to all three of these were coded as a non-victim (weighted n = 2529).

Gender identity

Participants indicated their gender as either male (0) or female (1) upon entry to the AmeriSpeak panel.

Strength of political identity

Participants indicated the strength of their political party identity from strong Democrat (1) to don’t lean/Independent/none (4) to strong Republican (7). The item was reverse scored for easier interpretation of results so that higher scores indicate stronger identification as Democrat.

Other demographics

Ethnicity, age, household income, education, employment status, marital status, U.S. Census Bureau designated geographic region were collected upon entry to the AmeriSpeak panel, prior to the Ford and Kavanaugh hearings. These variables were included as covariates in analyses.

Analytic strategy

Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 1670. Summary scores were created for self-reported hearings-related media exposure and acute stress to account for variability71, and categorical variables were dummy coded. Two path models were constructed, one with interpersonal violence victim, gender, and political identity main effects and another adding two-way interactions among these three variables, predicting acute stress, controlling for covariates (the significance of the results does not change when the model is repeated with each interaction term included on its own). Self-reported media exposure was specified as a mediator between predictor variables and acute stress. Exogenous variables were free to correlate, and the models were fit with a full-information maximum likelihood approach. Statistical weights were applied to account for selection into the AmeriSpeak panel and differences between our sample and U.S. Census benchmarks. Model fit was based on the CD, which is analogous to R2 in linear regression and is the percentage of variance explained by the model. CD was used because estimates of other common fit indices, such as CFI, are often biased in complex weighted survey analysis72.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank GfK’s Government & Academic Research team of Debra Vanni, Wendy Mansfield, Mansour Fahimi, and Ying Wang for providing GfK KnowledgePanel data, preparing Web-based survey and data files, and for methodological and statistical guidance for Study 1. We thank J. Michael Dennis and Stephanie Jwo for their assistance with Web-based data collection from the AmeriSpeak panel and methodological guidance for Study 2. We thank Dana Rose Garfin for contributions to Study 1 and Pasha Dashtgard and Emma Grisham for their contributions to Study 2.

Author contributions

D.P.R.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. N.M.J.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Writing—review and editing. E.A.H.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing—review and editing. R.C.S.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing—review and editing.

Funding

Data collection for Study 1 was supported by U.S. National Science Foundation grants BCS-1342637, BCS-1451812, and BCS-1650792 to RCS and EAH; Study 2 was supported by intramural funds provided by the School of Social Ecology and the Sue & Bill Gross School of Nursing at the University of California, Irvine.

Data availability

Data, code and materials generated during and/or analyzed for both studies are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-023-33898-2.

References

- 1.Pfefferbaum B, Nitiéma P, Newman E. Is viewing mass trauma television coverage associated with trauma reactions in adults and youth? A meta-analytic review. J. Trauma. Stress. 2019;32:175–185. doi: 10.1002/jts.22391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lowe SR, Galea S. The mental health consequences of mass shootings. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2017;18:62–82. doi: 10.1177/1524838015591572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson RR, Jones NM, Holman EA, Silver RC. Media exposure to mass violence events can fuel a cycle of distress. Sci. Adv. 2019;5:eaav3502. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aav3502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silver RC, Holman EA, McIntosh DN, Poulin M, Gil-Rivas V. Nationwide longitudinal study of psychological responses to September 11. JAMA. 2002;288:1235–1244. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.10.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schuster MA, et al. A national survey of stress reactions after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. New Engl. J. Med. 2001;345:1507–1512. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200111153452024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silver RC, et al. Mental- and physical-health effects of acute exposure to media images of the September 11, 2001, attacks and the Iraq War. Psychol. Sci. 2013;24:1623–1634. doi: 10.1177/0956797612460406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holman EA, Silver RC. Health status and health care utilization following collective trauma: A 3-year national study of the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the United States. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011;73:483–490. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schlenger WE, et al. Psychological reactions to terrorist attacks: Findings from the national study of Americans’ reactions to September 11. JAMA. 2002;288:581–588. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.5.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pfefferbaum B, et al. Television exposure in children after a terrorist incident. Psychiatry Interpers. Biol. Process. 2001;64:202–211. doi: 10.1521/psyc.64.3.202.18462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fullerton CS, Mash HBH, Morganstein JC, Ursano RJ. Active shooter and terrorist event-related posttraumatic stress and depression: Television viewing and perceived safety. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2019;13:570–576. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2018.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holman EA, Garfin DR, Silver RC. Media’s role in broadcasting acute stress following the Boston Marathon bombings. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:93–98. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316265110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brewer MB. The social self: On being the same and different at the same time. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1991;17:475–482. doi: 10.1177/0146167291175001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brewer MB, Gardner W. Who is this “we”? Levels of collective identity and self representations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1996;71:83–93. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.71.1.83. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tajfel H, Turner JC. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In: Austin WG, Worchel S, editors. The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Brooks/Cole; 1979. pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turner JC, Hogg MA, Oakes PJ, Reicher SD, Wetherell MS. Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-categorization Theory. Basil Blackwell; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turner JC, Oakes PJ, Haslam SA, McGarty C. Self and collective: Cognition and social context. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1994;20:454–463. doi: 10.1177/0146167294205002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiao YJ, Coppin G, Van Bavel JJ. Perceiving the world through group-colored glasses: A perceptual model of intergroup relations. Psychol. Inq. 2016;27:255–274. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2016.1199221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Bavel JJ, Cunningham WA. A social identity approach to person memory: Group membership, collective identification, and social role shape attention and memory. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2012;38:1566–1578. doi: 10.1177/0146167212455829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Bavel JJ, Pereira A. The partisan brain: An identity-based model of political belief. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2018;22:213–224. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mackie DM, Devos T, Smith ER. Intergroup emotions: Explaining offensive action tendencies in an intergroup context. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2000;79:602–616. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.79.4.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith ER, Seger CR, Mackie DM. Can emotions be truly group level? Evidence regarding four conceptual criteria. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2007;93:431–446. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.3.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wayment HA. It could have been me: Vicarious victims and disaster-focused distress. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2004;30:515–528. doi: 10.1177/0146167203261892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wayment HA, Silver RC, Kemeny ME. Spared at random: Survivor reactions in the gay community. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1995;25:187–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1995.tb01590.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ursano RJ, Fullerton CS, Vance K, Kao TC. Posttraumatic stress disorder and identification in disaster workers. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1999;156:353–359. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.3.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cetin M, et al. Identification and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in rescue workers in the Marmara, Turkey, earthquake. J. Trauma. Stress. 2005;18:485–489. doi: 10.1002/jts.20056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mash HBH, Ursano RJ, Benevides KN, Fullerton CS. Identification with terrorist victims of the Washington, DC sniper attacks: Posttraumatic stress and depression. J. Trauma. Stress. 2016;29:41–48. doi: 10.1002/jts.22069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muldoon OT, et al. The social psychology of responses to trauma: Social identity pathways associated with divergent traumatic responses. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2019;30:311–348. doi: 10.1080/10463283.2020.1711628. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muldoon OT, Lowe RD, Jetten J, Cruwys T, Haslam SA. Personal and political: Post-traumatic stress through the lens of social identity, power, and politics. Polit. Psychol. 2020;42:501–533. doi: 10.1111/pops.12709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brewer MB, Caporael LR. An evolutionary perspective on social identity: Revisiting groups. In: Schaller M, Simpson J, Kenrick D, editors. Evolution and Social Psychology. Psychology Press; 2006. pp. 43–161. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Branscombe NR, Schmitt MT, Harvey RD. Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African Americans: Implications for group identification and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1999;77:135–149. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.77.1.135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gallagher S, Meaney S, Muldoon OT. Social identity influences stress appraisals and cardiovascular reactions to acute stress exposure. Br. J. Health. Psychol. 2014;19:566–579. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haslam SA. Making a good theory practical: Five lessons for an applied social identity approach to challenges of organizational, health, and clinical psychology. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2014;53:1–20. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haslam SA, Jetten J, O’Brien A, Jacobs E. Social identity, social influence, and reactions to potentially stressful tasks: Support for the self-categorization model of stress. Stress Health. 2004;20:3–9. doi: 10.1002/smi.995. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kellezi B, Bowe M, Wakefield JRH, McNamara N, Bosworth M. Understanding and coping with immigrant detention: Social identity as a cure and a curse. Euro. J. Soc. Psychol. 2019;49:333–351. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2543. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muldoon OT, Lowe RD. Social identity, groups, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Polit. Psychol. 2012;33:259–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2012.00874.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmid K, Muldoon OT. Perceived threat, social identification, and psychological well-being: The effects of political conflict exposure. Polit. Psychol. 2015;36:75–92. doi: 10.1111/pops.12073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bar-Haim Y, Lamy D, Pergamin L, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van Ijzendoorn MH. Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and nonanxious individuals: A meta-analytic study. Psychol. Bull. 2007;133:1–24. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garrett N, González-Garzón AM, Foulkes L, Levita L, Sharot T. Updating beliefs under perceived threat. J. Neurosci. 2018;38:7901–7911. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0716-18.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bishop S, Duncan J, Brett M, Lawrence AD. Prefrontal cortical function and anxiety: Controlling attention to threat-related stimuli. Nat. Neurosci. 2004;7:184–188. doi: 10.1038/nn1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mogg K, Bradley BP. Anxiety and threat-related attention: Cognitive-motivational framework and treatment. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2018;22:225–240. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2018.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mogg K, Bradley BP. A cognitive-motivational analysis of anxiety. Behav. Res. Ther. 1998;36:809–848. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00063-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seeger MW, Vennette S, Ulmer RR, Sellnow TL. Media use, information seeking, and reported needs in post crisis contexts. In: Greenberg BS, editor. Communication and Terrorism. Hampton Press; 2002. pp. 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holman AE, Garfin DR, Lubens P, Silver RC. Media exposure to collective trauma, mental health, and functioning: Does it matter what you see? Clin. Psych. Sci. 2020;8:111–124. doi: 10.1177/2167702619858300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramirez JL, Gonzalez KA, Galupo MP. Invisible during my own crisis: Responses of LGBT people of color to the Orlando shooting. J. Homosex. 2018;65:579–599. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2017.1328217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cole ER. Intersectionality and research in psychology. Am. Psychol. 2009;64:170–180. doi: 10.1037/a0014564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Collins PH, Bilge S. Intersectionality. Wiley; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bryant RA. Acute Stress Disorder: What it is and How to Treat it. Guilford Publications; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elliott DM. Traumatic events: Prevalence and delayed recall in the general population. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1997;65:811–820. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.65.5.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cloitre M, Scarvalone P, Difede J. Posttraumatic stress disorder, self-and interpersonal dysfunction among sexually retraumatized women. J. Trauma. Stress. 1997;10:437–452. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490100309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith, S. G. et al. The national intimate partner and sexual violence survey (NISVS): 2015 data brief – updated release (National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018).

- 51.Elliott DM, Mok DS, Briere J. Adult sexual assault: Prevalence, symptomatology, and sex differences in the general population. J. Trauma. Stress. 2004;17:203–211. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000029263.11104.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wright JM, Clark JH, Evans HK. They were laughing: Congressional framing of Dr. Christine Blasey Ford’s sexual assault allegations on Twitter. Polit. Res. Quart. 2022;75:17–159. doi: 10.1177/1065912920987631. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Prins A, et al. The primary care PTSD screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5): Development and evaluation within a veteran primary care sample. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2016;31:1206–1211. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3703-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition: DSM-5, (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

- 55.Gobin RL, Freyd JJ. The impact of betrayal trauma on the tendency to trust. Psychol. Trauma. 2014;6:505–511. doi: 10.1037/a0032452. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.World Health Organization . Global, Regional and National Prevalence Estimates for Intimate Partner Violence Against Women and Global And Regional Prevalence Estimates for Non-partner Violence Against Women. WHO; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leemis R. W., et al. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2016/2017 Report on Intimate Partner Violence (National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022). https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/fastfact.html

- 58.Peck, E. Brett Kavanaugh plays the victim. HuffPost (2018). https://www.huffpost.com/entry/brett-kavanaugh-testimony-plays-victim-senate-hearing_n_5bad3b5ae4b0b4d308d1310b

- 59.Bauer GR. Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: Challenges and the potential to advance health equity. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014;110:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Slater MD. Reinforcing spirals: The mutual influence of media selectivity and media effects and their impact on individual behavior and social identity. Commun. Theory. 2007;17:281–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2007.00296.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Harwood J. Age identification, social identity gratifications, and television viewing. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media. 1999;43:123–136. doi: 10.1080/08838159909364479. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Goldenberg A, Halperin E, Van Zomeren M, Gross JJ. The process model of group-based emotion: Integrating intergroup emotion and emotion regulation perspectives. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2016;20:118–141. doi: 10.1177/1088868315581263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mash HBH, Fullerton CS, Benevides KN, Ursano RJ. Identification with terrorist attack victims: Association with television viewing and prior life threat. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2018;12:337–344. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2017.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Prentice DA, Miller DT. When small effects are impressive. Psychol. Bull. 1992;112:160–164. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bor J, Venkataramani AS, Williams DR, Tsai AC. Police killings and their spillover effects on the mental health of black Americans: A population-based, quasi-experimental study. Lancet. 2018;392:302–310. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31130-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Eichstaedt JC, et al. The emotional and mental health impact of the murder of George Floyd on the US population. PNAS. 2021;118:e2109139118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2109139118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Reinka MA, Pan-Weisz B, Lawner EK, Quinn DM. Cumulative consequences of stigma: Possessing multiple concealable stigmatized identities is associated with worse quality of life. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2020;50:253–261. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12656. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Haslam SA, O’Brien A, Jetten J, Vormedal K, Penna S. Taking the strain: Social identity, social support, and the experience of stress. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2005;44:355–370. doi: 10.1348/014466605X37468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Westmaas JL, Silver RC. The role of perceived similarity in supportive responses to victims of negative life events. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2006;32:1537–1546. doi: 10.1177/0146167206291874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.StataCorp . Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. StataCorp LLC; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 71.MacCallum RC, Zhang S, Preacher KJ, Rucker DD. On the practice of dichotomization of quantitative variables. Psychol. Methods. 2002;7:19–40. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bollen, K. A., Tueller, S. T., Oberski, D. Issues in the structural equation modeling of complex survey data. In: Proceedings of the 59th World Statistics Congress, 1235–1240 (2013).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data, code and materials generated during and/or analyzed for both studies are available from the corresponding author upon request.