Abstract

The Plasmodium FIKK kinases are diverged from human kinases structurally. They harbour conserved ATP-binding domains that are non-homologous to other existing kinases. FIKK9.1 kinase is considered as an essential protein for parasite survival. It is localized in major organelles present in parasite and trafficked throughout the infected RBC. It is speculated that FIKK9.1 may phosphorylate several substrates in the parasite’s proteome and contribute to parasite survival. Therefore, FIKK9.1 is an attractive target that may lead to a novel class of antimalarials. To identify specific FIKK9.1 kinase inhibitors, we virtually screened organic structural scaffolds from a library of 623 entries. The top hits were identified based on conformations and molecular interactions with the ATP biophore. The hits were also validated under in vitro conditions. In this study, we identified seven top hit organic compounds that may arrest the growth of parasites by inhibiting FIKK9.1 kinase. Evaluation of top hit compounds in antimalarial activity assay identifies that the highly substituted 1,3-selenazolidin-2-imine 1 and thiophene 2 are inhibiting parasite growth with an IC50 of 3.2 ± 0.27 μg/ml and 3.13 ± 0.16 μg/ml, respectively. These functionalized heterocyclic compounds 1 and 2 kills the malaria parasite with an IC50 of 2.68 ± 0.02 μg/ml and 3.08 ± 0.14 μg/ml, respectively. Isothermal titration calorimetry analysis indicate that ATP is binding to the FIKK9.1 kinase. The dissociation constant (Kd) is measured to be 27.8 ± 2.07 μM with a stoichiometry of n = 1. The heterocyclic scaffolds 1 and 2 were abolishing the binding of ATP into the binding pocket. They in-turn reduce the ability of FIKK9.1 kinase to phosphorylate its substrate. Our study found that compounds 1 and 2 are potent inhibitor of FIKK9.1 kinase and the inhibition of FIKK9.1 kinase using small molecules disturbs the parasite life cycle and leads to the death of parasites. This provides new insight in development of novel antimalarials.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13205-023-03677-x.

Keywords: Malaria, FIKK kinase, Lead identification and antimalarial

Introduction

Malaria is a pernicious disease causing nearly half million deaths each year (Organization 2020). Although, malaria-associated death may have declined over a few decades through various efforts such as vector control strategies (Mnzava et al. 2014) and stable artemisinin combination therapies (Pousibet-Puerto et al. 2016) there is a steady increase in malarial cases around the globe. This demands extensive efforts to achieve the goal of eradication of malaria. To improve the outcome, we must ensure total cure of disease through safer and efficient development of new treatments. Drugs such as chloroquine, mefloquine, sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine, lumefantrine and quinine are prevalently used in endemic regions as antimalarials. Drug resistance and side effects of those drugs forced the introduction of artemisinin combination therapy (ACT’s) in endemic areas (Haldar et al. 2018). However, the resistance and delayed death of parasites to artemisinin with some of its partner drugs are reported in Greater Mekong Sub-region (Menard and Dondorp 2017) and Eastern India (Das et al. 2018). Though the current antimalarial drug pipeline is promising, there is no alternative therapy besides ACT to control malaria (Nsanzabana 2019). Therefore, development of new antimalarials against novel targets is important to control malaria.

During the parasite life cycle, early rings develop into trophozoites and schizonts before the merozoites rupture to invade other uninfected RBC’s (Tuteja 2007). The developmental process involves a cascade of signaling events to alter structural and functional changes of RBC’s. The RBC’s structural and functional aberrations include increased rigidity, decreased deformability and abnormal cyto-adherence of infected RBC’s (Moxon et al. 2011). A number of proteins exported to infected RBC cytoplasm are characterized to understand the molecular mechanism behind RBC modulation and pathogenesis of parasites inside the host (Batinovic et al. 2017; Rug et al. 2014). Out of ⁓ 99 epk’s, 27 families of kinase are exported outside parasites which includes FIKK kinases as well. Studies suggests that these family of kinases may involve in remodeling of RBCs, but there are not substantial evidence to support its exact function in IRBC’s.

FIKK kinases are present exclusively in apicomplexan family and do not have any orthologues in humans. Interestingly, Plasmodium falciparum, which is responsible for complicated malaria, contains 21 FIKK kinases but other apicomplexan members consists of single FIKK kinase (Ward et al. 2004). Among 21 FIKK kinases 17 FIKK’s contains PEXEL (protein export element) motif in their sequence in order to export these proteins outside parasite. In contrast, even the presence of PEXEL motif in FIKK3 and FIKK9.5, has not found to be exported outside parasite. FIKK3 present in apical rhoptry organelle, whereas FIKK9.5 is associated with parasite nucleus. It shows that FIKK3 may involve in invasion and FIKK9.5 may involve in controlling of nuclei division. All other FIKK’s are targeted toward different location inside the IRBC’s (infected RBC) and plays a crucial role in parasite survival. FIKKs (4.1, 9.3, 9.4, 9.6 and 9.7) are found to be non-essential proteins for parasite growth and are characterized to involve in pathogenicity of malaria (Davies et al. 2020). The deletion of genes such as FIKK9.1, FIKK10.1 and FIKK10.2 in Plasmodium falciparum, shows its essentiality of these for parasite survival during erythrocytic stages of parasite and may play an important role in novel pathways (Siddiqui et al. 2020). The phosphoproteomic analysis of FIKK’s shows unique phosphorylation fingerprinting for each FIKK even though it involves in similar pathways (Davies et al. 2020). Hence, each FIKK has its independent role in parasite to complete its life cycle in hosts. Emodin, a known kinase inhibitor, arrests the parasite growth by inhibiting PvFIKK and FIKK 8 under in vitro condition (Lin et al. 2017a; Lin et al. 2017b). In our previous study, we found FIKK9.1 is localized in cytoplasm, Maurer’s clefts (mC’s) (Davies et al. 2020) and as well as in apicoplast (AK et al. 2021). Collectively, evidence suggests that FIKK9.1 may be involved in trafficking virulence proteins and/or drug-related stresses linked to new permeability pathways (NPP). Therefore, targeting FIKK kinases could lead to development of novel class of antimalarials.

In the current study, we focused on identifying potent FIKK9.1 kinase inhibitors through virtual screening. We have created library of more than 600 structural scaffolds with diverse chemical features. The synthesized compounds are found to be structurally similar to the bioactive compounds found in nature. Therefore, we created the library of these molecules to explore the possibility of identifying a potential antimalarial compound. The compounds are docked in previously identified ATP biophoric region in FIKK9.1 using Autodock (4.1) virtual screening tool. The compounds are shortlisted based on their affinity and chemical complementarity within the ATP-binding region of FIKK9.1 kinase. Top-ranked molecules are further screened through its drug-likeness and in silico toxicity predictions. Our study identified a total of seven compounds, of which compound 1–4 are potential small molecule inhibitors for FIKK9.1 kinase. Through in-vitro antimalarial assays, we found the Se and S-containing heterocycles, (Z)-3-isopropyl-N-(naphthalene-1-yl)-5-phenyl-1,3-selenazolidin- 2-imine 1 and 4-benzoyl-3-benzyl-5-(m-tolyl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde 2, significantly inhibit the growth of parasites with an IC50 2.68 ± 0.02 µg/ml and 3.08 ± 0.14 µg/ml, respectively. Both the heterocycles has deleterious effect on ATP binding with FIKK9.1 kinase and as well as significantly reduces the phosphorylation of Bovine serum albumin (BSA). The distribution of ATP binding with FIKK9.1 and kinase activity of FIKK9.1 under in vitro conditions in presence and absence of compound 1 and 2 clearly suggest that the killing of parasite growth may be mediated through inhibiting FIKK9.1. Hence, our data suggest that FIKK9.1 kinase may be exploited as a drug target to develop new class of antimalarial.

Results

FIKK9.1 has well-defined ATP-binding pocket within catalytic domain

Structural features of FIKK9.1 catalytic domain is of typical kinase domain, which has similar structural arrangement to other protein kinases. The catalytic domain consists of two lobes where ATP and protein substrates tend to bind. N-lobe made with five β-strands and one α-helix, whereas C-lobes consist of conserved α-helix structure. In comparison with structural elements of cAMP dependent kinases, calcium-dependent kinases and protein kinase A (PKA) structures, FIKK9.1 possesses a number of conserved residues for ATP binding in between the lobes. Though it has conserved regions such as SELYG (312–315), PENILI (365–370) and DFG (379–382) motif, the absence of glycine triad and RD activation loop shows FIKK9.1 can be specifically targeted (Fig. 1A). To exploit the ATP-binding region for virtual screening of potential inhibitors, ATP docked with FIKK9.1 interaction is analyzed. As like typical kinases, the region is lined with F243, V244, M245, I443, K320, K324, D379, F380 and G381 residues that makes a better region for ATP to bind with FIKK9.1. The ribose ring of ATP supported by hydrophobic residues such as V244, M245 and E246, and other residues notably F243, I443 and D445 covered adenine ring to stabilize ATP. Whereas the PO4 group is anchored and correctly positioned for phosphor transfer by a positive-charged tunnel consists of R318, K320 and K324 residues (Fig. 1B). Besides the ATP-binding pocket, there are residues which extensively interact with ATP and stabilize it for catalysis. The formation of salt bridge between I443 and adenine ring anchors ATP, whereas the hydrogen bonding of K320 with α-phosphate and K324 with leaving group γ-phosphate stabilizing and positioning the ATP for phospho transfer to substrate (Fig. 1C). These functionally important interacting residues of FIKK9.1with ATP have been exploited for further screening of inhibitors.

Fig. 1.

FIKK9.1 catalytic domain harbors ATP. A Structure of FIKK9.1 kinase catalytic domain with highlighted ATP-binding pocket. B ATP (red) that rendered as ball and stick model, binds to FIKK9.1 catalytic site nicely. The important residues present around ATP binding is labeled. C Interaction of ATP with crucial residues of FIKK9.1 catalytic domain. The ATP biophore consists of residues such as F243, V244, M245, I443, K320, K324, D379, F380 and G381. The ribose group is interacts with F243, V244 and M245. The phosphate group is anchored with conserved lysine (K320 and K324)

Compounds interact with important ATP-binding residues in FIKK9.1

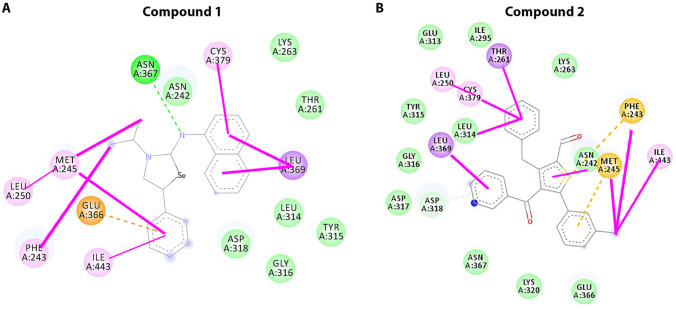

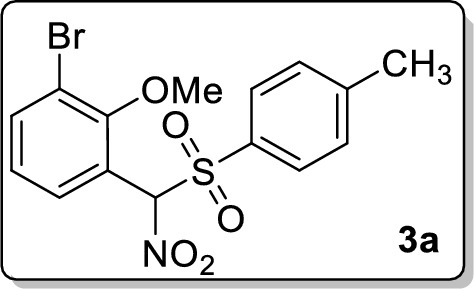

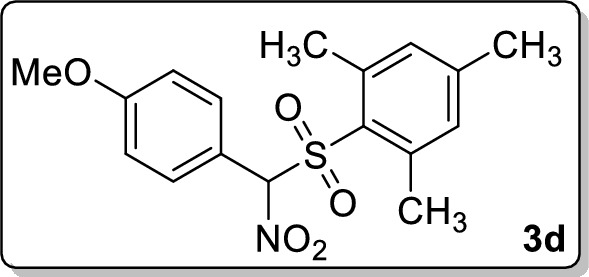

In our collaborator’s lab, who is extensively performing the organic synthesis of different types of compounds to explore its mechanistic details. The synthesized compounds are found to be structurally similar to the well-known bioactive compounds found in nature. Therefore, we created the library of the compounds to explore the possibility of identifying a potential antimalarial compound. Total 623 chemical inhibitors are screened for identifying inhibitors of FIKK9.1 to develop antimalarials. All 623 compounds are docked into ATP pharmacophore environment. Docking pose of each compound is inspected and stored to identify potent inhibitors. Compounds are shortlisted based on binding affinity, binding geometry and interaction with most important residues of FIKK9.1 (supplementary Excel sheet1). The binding energy of ATP (control for docking) is calculated to be − 6.14 kcal/mol and energy required minimal than ATP for compounds to bind with FIKK9.1 are identified. From binding affinity and geometry inspection, 20 compounds are identified as potential hit (Table 1). The binding affinity obtained for top compounds are ranged from − 8.24 to − 7.34 kcal/mol. Further all those molecules are analyzed for its toxicity profiling, most of the molecules follows Lipinski’s rule of 5 and fewer molecules predicted to produce hepatotoxicity (supplementary Excel sheet2). Therefore, based on docking studies and toxicity profiling, seven compounds 1–4 are selected to perform in vitro assays. All these molecules are binding exactly to the ATP pharmacophore environment and interact with FIKK9.1 (Fig. 2A, B). Bonding with most important residues for ATP binding suggests some of these molecules could be potential inhibitors of FIKK9.1. The compound 1 and 2 mostly forms hydrophobic interaction to the biophore region. The ligplot analysis reveals heterocycles 1 and 2 make extensive bonding and non-bonding interaction with active site residues (Fig. 3). In comparison with ATP and FIKK9.1 interaction, compounds 1 and 2 renders similar atomic interaction with FIKK9.1. In depth, both the compounds favours extensive hydrophobic interaction and makes hydrogen bonding with key residues such as L314, D318, E366 and I443 within a distance of 4 Å. In typical kinases, these residues are known for anchoring and positioning of adenosine ring and phosphate residues in ATP for phospho transfer to the substrate. Standard kinase inhibitor (Pc-44215930) was tested to address the FIKK9.1 kinase ATP biophore environment favours specific dock with lead molecules. Interestingly, the Pc-44215930 find to interact with fewer residues in FIKK9.1 kinase at relatively high binding energy (− 6.16 kcal/mol). The Pc-44215930 restricted to interact with residues such as ASN242, GLY316, ASP318, ASN 317 and ASN367 in FIKK9.1 ATP biophore (Table 2). Absence of major bonding events such as interaction of CDFG motif and key lysine residues between FIKK9.1 and ligand shows ATP-binding pocket may disfavours binding of existing ATP competitive kinase inhibitor.

Table 1.

List of potential heterocyclic compounds to bind with FIKK9.1 better than ATP

| Compound | No. of conformation | Binding energy Kcal/mol |

|---|---|---|

| 3c | 3 | − 8.24 |

| 472 | 3 | − 8.06 |

| 1 | 3 | − 7.66 |

| 264 | 2 | − 8.36 |

| 263 | 5 | − 7.91 |

| 258 | 3 | − 7.79 |

| 3a | 2 | − 7.74 |

| 3d | 1 | − 7.6 |

| 255 | 3 | − 7.23 |

| 277 | 2 | − 7.62 |

| 261 | 5 | − 7.58 |

| 2 | 3 | − 7.4 |

| 435 | 5 | − 7.26 |

| 3b | 4 | − 7.26 |

| 275 | 2 | − 7.69 |

| 393 | 4 | − 7.62 |

| 260 | 2 | − 7.56 |

| 318 | 3 | − 7.4 |

| 4 | 3 | − 7.34 |

| ATP | 2 | − 6.14 |

Autodock4.1 was used to calculate binding energy of heterocyclic compounds

ATP adenosine triphosphate

Fig. 2.

Screening of Scaffolds 1–4 in ATP pharmacophore region. The binding pose of top six molecules such as 4 (green), 1 (blue), 3a (yellow), 3c (cyan), 3b (brown) and 2 (grey) within FIKK9.1 kinase binding pocket. ATP is shown in red. All the top hits are tend to binds in the ATP biophore region

Fig. 3.

Heterocycles 1 and 2 make extensive interaction with residues present within FIKK9.1 kinase binding pocket. A The 2-D interaction profile shows 1 and 2 interact with residues which are important for ATP binding in FIKK9.1 kinase. Both the compounds shows hydrophobic bonding and makes with key hydrogen bonding with residues such as L314, D318, E366 and I443

Table 2.

Interaction profiling of FIKK9.1 with its natural ligand (ATP) and inhibitors (Compound 1/2)

| Compound | Residue number | AA | Distance (Å) | Donor atom | Acceptor atom | Interaction type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 243 | PHE | 3.55 | 5576 | 2444 | Hydrophobic |

| 250 | LEU | 3.56 | 5570 | 2501 | Hydrophobic | |

| 314 | LEU | 3.02 | 5567 | 3129 | Hydrophobic | |

| 366 | GLU | 3.38 | 5579 | 3676 | Hydrophobic | |

| 369 | LEU | 3.32 | 5564 | 3707 | Hydrophobic | |

| 369 | LEU | 3.28 | 5565 | 3708 | Hydrophobic | |

| 443 | ILE | 3.34 | 5578 | 4467 | Hydrophobic | |

| 367 | ASN | 2.83 | 5560 | 3687 | Hydrogen bonding | |

| 318 | ASP | 5.38 | 5558 | – | Salt bridge | |

| 2 | 250 | LEU | 3.08 | 5574 | 2501 | Hydrophobic |

| 261 | THR | 3.46 | 5574 | 2612 | Hydrophobic | |

| 295 | ILE | 3.25 | 5572 | 2959 | Hydrophobic | |

| 318 | ASP | 3.53 | 5581 | 3164 | Hydrophobic | |

| 366 | GLU | 3.08 | 5579 | 3676 | Hydrophobic | |

| 369 | LEU | 3.31 | 5571 | 3707 | Hydrophobic | |

| 369 | LEU | 3 | 5567 | 3708 | Hydrophobic | |

| ATP | 242 | ASN | 1.71 | 2431 | 5561 | Hydrogen bonding |

| 263 | LYS | 3.09 | 2630 | 5572 | Hydrogen bonding | |

| 315 | TYR | 2.67 | 3132 | 5575 | Hydrogen bonding | |

| 318 | ASP | 2.91 | 3160 | 5565 | Hydrogen bonding | |

| 318 | ASP | 1.91 | 5565 | 3167 | Hydrogen bonding | |

| 366 | GLU | 3.17 | 3679 | 5585 | Hydrogen bonding | |

| 366 | GLU | 2.84 | 5579 | 3674 | Hydrogen bonding | |

| PC-44215930 | 242 | ASN | 1.98 | 2430 | 5581 | Hydrogen bonding |

| 316 | GLY | 2.07 | 5583 | 3149 | Hydrogen bonding | |

| 318 | ASP | 2.64 | 5558 | 3167 | Hydrogen bonding | |

| 367 | ASN | 1.81 | 5582 | 3688 | Hydrogen bonding |

An AA indicates amino acid and a dash (–) indicates no interaction of specific atom

(b) Image showing the interacting amino acid residues in 2D conformation for Pc-44215930

To validate the dependency of residues present in ligand-binding region, we performed in silico mutational analysis. Amino acid residues involved in ATP binding are mutated and docked with heterocycles (1 and 2). Every mutated protein model was compared with wild-type model. The mutated models were superimposed with wild-type before performing docking with ligands. All the mutated models were observed to have < 0.2 Å RMSD. In other words, the in silico mutated proteins does not show any significant changes in model compared to wild-type model. The mutation of amino acids such as V244A, E246A, K320A and K324A shows significant decrease in their binding energies of FIKK9.1 with ATP. On the other hand, Compound (1 and 2) exhibits different profile of dependency in biophore residues. The mutation in residues such as V244A, M245A, and E366A strongly influences the binding of small molecules within ATP-binding pocket of FIKK9.1. The difference of binding energies suggests that these heterocycles specifically binds and interact with ATP biophoric residues in FIKK9.1 (Table 3).

Table 3.

The binding energies of docked complexes of ATP and Heterocycles (1 and 2) with FIKK9.1 mutants

| Amino acid mutation (FIKK9.1) | Binding Energy (kcal/mol) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ATP | Compound 1 | Compound 2 | |

| Native | − 6.21 | − 7.84 | − 7.55 |

| V244A | − 4.89 | − 5.67 | − 6.39 |

| M245A | − 5.38 | − 5.87 | − 5.76 |

| E246A | − 4.36 | − 6.02 | − 5.92 |

| K320A | − 4.33 | − 5.59 | − 5.94 |

| N321A | − 5.57 | − 5.86 | − 6.53 |

| K324A | − 3.27 | − 6.07 | − 6.1 |

| E366A | − 5.91 | − 4.97 | − 4.54 |

The stability of the interaction between FIKK9.1 with ATP and heterocycles (1 and 2) complexes were assessed through molecular dynamics simulations. The simulation of these complexes were performed under NVT conditions for 10 ns time scale. The FIKK9.1-complexes were analyzed for Hydrogen bonding, RMSD, RMSF and Radius of gyration. Through the hydrogen bonding analysis, we observed that the interaction of FIKK9.1 and ATP is stabilized by hydrogen bond formation, whereas the interaction of FIKK9.1 and heterocycles (1 and 2) anchored by hydrophobic interaction with formation of minimal hydrogen bond. The structural difference between coordinates and compactness of the protein structure in the docked state are analyzed using RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation) and Radius of gyration for protein ligand complexes. For all the three complexes, RMSD and Radius of gyration analysis suggests that the binding of ligands with protein does not create the unfolding of protein. However, we assessed the binding strength of the FIKK9.1 and ligand complexes using root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) analysis of FIKK9.1 residue. The average RMSF value of residues present in biophoric regions is found to be 0.3 nm for all complexes (supplementary Fig. 1). This clearly suggests FIKK9.1 binding with ATP and heterocycles 1 and 2 are significantly stable in nature.

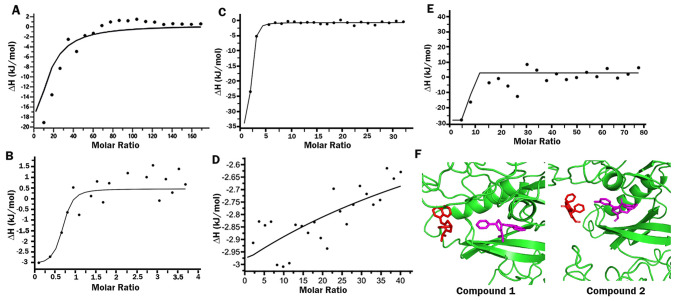

The Heterocycles 1 and 2 disrupts FIKK9.1 and ATP binding

In order to identify the heterocycles 1 and 2 can disrupt FIKK9.1 and ATP binding, isothermal titration calorimetry experiment was performed. Upon titration of ATP with FIKK9.1 heat changes in the system is measured. Binding of ATP with FIKK9.1 found to be enthalpy driven as the interaction has lesser ∆H value, in terms it favors hydrogen bonding. The dissociation constant Kd is calculated to be 27.8 ± 2.07 µM with a stoichiometry n = 1 based on binding. The saturation of curve upon subsequent injection of titrant depicts ATP binding with FIKK9.1 (Fig. 4A). The ITC experiment was performed to calculate the binding affinities of heterocycles 1 and 2 with FIKK9.1. The heat of dilution was subtracted. From the analysis, we have identified both the heterocycles binds to ATP with an Kd value of 9.6 ± 0.9 µM (compound 1) and 1.21 ± 0.32 µM (compound 2). The stoichiometry (n) of compound 1 and 2 is identified to be 1 (Fig. 4B, C).To understand whether 1 and 2 are able to abolish ATP binding with FIKK9.1, ATP is titrated when FIKK9.1 preincubated with compound 1 or 2. The interaction is observed to be affected as the dissociation constant tends to increase. The saturation curve shows that preincubation of heterocycle 1/2 produces unfavorable conditions for ATP to bind with FIKK9.1 (Fig. 4D, E). Additionally the docking of heterocycles to FIKK9.1 in presence of ATP was performed, to show heterocycles shares some of the most important residues involved ATP binding. The docking studies reveals that the compounds were binds deep inside into the ATP-binding pocket in the absence of ATP whereas in the presence of ATP, binding of the molecules was found to be disturbed and makes interaction on the surface of FIKK9.1 (Fig. 4F). Thus, these heterocycles 1 and 2 are found to be potential inhibitors and utilized to test the in vitro antimalarial activity.

Fig. 4.

Heterocycles 1 and 2 abolishes ATP binding into the FIKK9.1 kinase binding pocket. The interaction of ATP with FIKK9.1 is analyzed in presence /absence of compound 1/2. A Binding of FIKK9.1 with ATP. In the absence of 1/2 compounds, The saturation curve suggests ATP binding with FIKK9.1 Thermodynamic parameters of FIKK9.1 binding with heterocycles compound 1 (B) and compound 2 (C) were measured using ITC. The graph shows binding of FIKK9.1 with heterocycle 1 and heterocycle 2. The effect of preincubation of compounds with FIKK9.1 on ATP binding was measured. In both the cases, the preincubation of (d) compound 1 or (E) compound 2 with FIKK9.1 disturbs the ATP binding with the protein. (F) The effect of ATP in hetrocycle 1 and 2 binding with FIKK9.1 was analyzed through docking. The docked complexes of ATP (red) clearly shows that the binding of heterocycles (magenta) 1 and 2 distrubs ATP binding with FIKK9.1

Heterocycles 1 and 2 are potent antimalarials

Based on results of virtual screening, top seven compounds 1–4 from library of 623 compounds are likely to be potent inhibitors of FIKK9.1 to give antimalarial activity. Therefore, all seven compounds were tested for its antimalarial activity using Pf3d7 parasite culture. Nitromethyl sulfone, 2-(((4-chlorophenyl)(nitro)methyl)sulfonyl)-1,3,5-trimethylbenzene 3b shows no activity, whereas 1-bromo-2-methoxy-3-(nitro(tosyl)-methyl)benzene 3a and 1-(2-chlorophenyl)-N-(2-iodo-4-methylphenyl)-1H-tetrazole-5-amine 4 were giving very high IC50 in the range of 125 μM. Further, the sulfones, 2-(nitro(tosyl)methyl)- naphthalene 3c and 2-(((4-methoxyphenyl)(nitro)methyl)sulfonyl)-1,3,5-trimethylbenzene 3d showed moderate antimalarial activity. The heterocycles 1 and 2 are found to inhibit parasite growth with an IC50 of 2.68 ± 0.02 µg/ml and 3.08 ± 0.14 µg/ml, respectively (Table 4). Among all, the heterocycles 1 and 2 are found to be potent antimalarial. The compound treated parasite cultures is examined microscopically to understand structural abnormalities in RBCs and the ability of parasite to develop into schizont stage. The study uses chloroquine treated parasites as a positive control. In the beginning, infected RBCs were found to be healthy in both untreated and inhibitor treated cultures. But, after incubation with compounds for 38 h, parasites treated with chloroquine, heterocycle 1 or 2 showed dead ring, dead tropho and dead schizonts. In comparison, untreated parasites were showing all RBC stages and completion of erythrocytic life cycle. The microscopic examination reveals parasites are halting at one stage in treated samples and could not be able to complete its life cycle (Fig. 5A). It suggests that FIKK 9.1 inhibitor block the erythrocyte developmental stages (from ring to schizont) of parasites. The FIKK9.1 inhibitors show good schizonticidal activity in in vitro schizont maturation assay. The inhibitory concentration IC50 of 1 and 2 are observed to be 3.22 ± 0.27 µg/ml and 3.13 ± 0.16 µg/ml for schizonticidal activity and 2.68 ± 0.02 µg/ml and 3.08 ± 0.14 µg/ml for parasiticidal activity under in vitro conditions (Fig. 5B). Although both the FIKK9.1 inhibitors are effective in blocking maturation of ring to schizont, we further asked if compounds were also causing parasite death and exhibiting parasiticidal activity. Compound-treated parasite was washed three times with fresh medium and then parasite was allowed to grow in fresh medium with compound for 96 h. After 96 h, thin smear is taken and viable parasites are counted through microscopy.

Table 4.

In vitro antimalarial activity of novel heterocyclic compounds

| S. no. | Compound ID | Schizonticidal activity (µg/ml) | Parasiticidal activity (µg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 3.22 ± 0.27 | 2.68 ± 0.02 |

| 2 | 2 | 3.13 ± 0.16 | 3.08 ± 0.14 |

| 3 | 3a | > 25 | > 25 |

| 4 | 3b | No activity | No activity |

| 5 | 3c | > 25 | > 25 |

| 6 | 3d | > 25 | > 25 |

| 7 | 4 | > 25 | > 25 |

IC50 values of heterocyclic compounds were calculated using regression analysis. Values were denoted in microgram per millilitre

SD standard deviation

Fig. 5.

Heterocycles 1 and 2 are killing malaria parasite through inhibition of FIKK9.1 kinase. A Heterocycles 1 and 2 disturb parasite lifecycle. Parasite culture (ring stage parasite) was treated with the heterocycles for 38 h and thin smear of RBCs was observed under the microscope. Untreated parasite culture was exhibiting all RBC stages but compound treated parasites was showing only dead parasite (ring or trophozoite stage). B Antimalarial activity of the heterocycles 1 and 2. The growth of parasites (Pf3d7) was evaluated in presence of different concentration of compounds (0–12.5 μg/ml). C Heterocycles 1 and 2 are killing malaria parasite. Parasite culture was treated with the heterocyclc scaffolds for 38 h, culture was washed with fresh medium and incubated for 96 h in fresh culture medium without the heterocycles. A thin smear of RBCs was observed under the microscope to monitor the growth of the parasite. Untreated parasite culture was exhibiting parasite and there was increase in parasitemia but compound treated parasites was showing only dead parasite. D Heterocycles 1 and 2 are inhibiting FIKK9.1 kinase-mediated BSA phosphorylation. The BSA was incubated as a substrate with purified FIKK 9.1 kinase in absence or presence of the heterocycles 1 and 2 the phosphorylation of BSA was measured using anti-pSer antibodies in western blot. The strong phosphorylation signal of phosphorylated BSA was obtained in the absence of the heterocycles 1 and 2, whereas the reduction of phosphosphorylated signal is observed in presence of the heterocycles 1 and 2. The protein signal on blot was measured and used to calculate the inhibition of FIKK 9.1 kinase activity. These values are represented in the graph to show the inhibition of FIKK 9.1 kinase by the compounds. E, F Heterocycles are not cytotoxic. The cytotoxicity of heterocycles 1 and 2 was evaluated in HEK 293 (E) and PBMC’s (F) at IC50 and 2 × IC50 concentrations. Percentage of cell viability was determined through MTT assay. The experiment performed in triplicates and the error bars represents the standard errors of mean (sEM)

The heterocycles are killing malaria parasite through chemically knocking out FIKK9.1

The untreated parasites were growing during this period to attain 2 folds parasitemia but there is no significant increase in parasitemia under compound treated conditions. Moreover, parasites treated with compounds were appeared to be dead and deformed compared to control parasites (Fig. 5C). To confirm that parasite killing is mediated through chemical knockout of FIKK9.1, kinase inhibition assay has been performed. Previously, it is known that FIKK9.1 belongs to serine-threonine protein kinase family and it efficiently phosphorylate BSA (AK et al. 2021). Therefore, we have analyzed in vitro BSA phosphorylation status by FIKK9.1 in presence and absence of 1 and 2 inhibitors. In the absence of FIKK9.1 inhibitor, FIKK9.1 is extensively phosphorylating BSA by addition of ATP, whereas in the presence of inhibitors, the phosphorylation of BSA is found to be decreased by several fold (Fig. 5D). It shows that FIKK9.1 is one of the primary targets for compound 1 and 2 for parasite death. This suggests FIKK9.1 is a drug target and possesses different unique salient features from host proteins which may provide deep insight to explore a new class of antimalarial.

The heterocycles are nontoxic to cells

The two promising antimalarial compounds is subjected to evaluate for its cytotoxicity on normal cell line (HEK 293) and PBMC’s. Both these cells are treated with IC50 and 2 × IC50 concentrations of heterocycles 1 and 2. In comparison to control, the morphology of HEK (Fig. 5E) and PBMC’s (Fig. 5F) are found to be unaffected upon treatment of heterocycles 1 and 2 at IC50 and 2 × IC50 concentrations. The MTT assay is performed to find the percentage difference in the cell viability compared to control. The cell viability percentage for compound 1 in HEK is determined to be 96.2 ± 3.56% and 92 ± 4.03%, whereas compound 2 shows 97.75 ± 2.44% and 93.8 ± 0.43% for IC50 and 2 × IC50 concentrations, respectively. In case of PBMC’s, the viable cells upon treatment with compound 1 are found to be 96.3 ± 4.1% and 94.1 ± 1.5% for IC50 and 2 × IC50 concentrations, whereas for compound 2–94 ± 7% and 84 ± 4% for IC50 and 2 × IC50 concentrations. Thus, the results suggest that both compounds are safe to use as an antimalarial.

Discussion

Kinases are the most important molecular targets in malaria, as we focus on deciphering new therapeutics against malaria (Arendse, et al. 2021). The clusters of malarial kinases that fall with other eukaryotic kinases made it as underrated targets. However, FIKK kinase of Plasmodium falciparum diverged from all other organisms and are exclusive to parasite only (Ward et al. 2004). Molecular function of most of FIKK’s are uncharacterized but localization as well export of FIKK kinase outside infected RBCs suggests that they may perform important functions such as remodeling of host cells, cyto-adhesion and protein trafficking leads to parasite virulence (Davies et al. 2020; Siddiqui et al. 2020; Lin et al. 2017b; Nunes et al. 2010). FIKK 9.1 is an exported FIKK family kinase, it spreads throughout IRBC’s during erythrocyte stages of parasites. Notably, subcellular and MC’s localization (Siddiqui et al. 2020; D, A.K.,, et al. 2021) makes FIKK9.1 an exciting target. In this study, we have exploited ATP pharmacophore environment in FIKK9.1 catalytic domain for identifying potential lead molecules (Fig. 1A). The ATP-binding region in FIKK9.1 is versatile and possesses some of the unique features from host proteins. The identification of alignment of the hydrophobic region for adenine group to bind and pocket favors triphosphate group anchoring (Fig. 1B, C) makes it suitable to screen inhibitors. Total 623 compounds were screened (supplementary data 1) and 20 molecules are predicted to inhibit parasite growth (Table 1). From 20 molecules, 7 compounds were found to interact with most important residues in FIKK9.1 for ATP binding (Fig. 2). Mainly interaction of two compounds 1 and 2 with residues M245, E366 and I443 involved in ATP binding and as well interaction with C379 in CDFG motif, a motif act as ON or OFF switch for kinases (Vijayan et al. 2015) makes these compounds as probable inhibitor for FIKK9.1 (Fig. 3A, B). The conclusion highly supported by docking of Pc-44215930 with FIKK9.1. The absence of the key interactions between Pc-44215930 and FIKK9.1 strongly suggests that the ATP biophore environment requires different structural scaffolds from existing kinase inhibitor groups. The molecular dynamic simulation also suggests the interaction between heterocycles (1 and 2) and FIKK9.1 are stable in nature. Treating the parasites with all seven molecules suggests 1 and 2 are potential lead molecules to inhibit parasite under in vitro condition (Table 3). Based on the ITC experiment the binding between heterocycles with FIKK9.1 was confirmed. Further, we found both these compounds were disrupts ATP binding with FIKK9.1 (Fig. 4A–E). Schizont maturation assay also suggests these compounds 1 and 2 is significantly decreasing parasite growth (Fig. 5A, B). Previously, only emodin has found as inhibitor for FIKK (pfFIKK8and pvFIKK) family of kinases (Lin et al. 2017a; b) but here we showed compound that could inhibit parasite growth by targeting FIKK kinase. The inactivation of FIKK9.1 enzyme through factors such as specific spacio-constraints, strong ionic and hydrophobic interaction makes inhibitors to specific in nature. In addition, both the inhibitors are found to be killing parasite (Fig. 5C). The dual localization, subcellular and exported to IRBC cytoplasm makes FIKK9.1 an excellent target. In our study, by targeting FIKK9.1, the parasite is killed irreversibly and which has been supported by kinase inhibition assay of FIKK9.1 on substrate (Fig. 5D). The cytotoxicity analysis of the heterocycle compound 1 and 2 supports that these molecules is specifically kills the parasite but not the normal mammalian HEK293 cells or human PBMC’s (Fig. 5E, F). These studies evident that FIKK9.1 could be potent drug target to develop new antimalarial of different chemical and biological sources.

Conclusion

In the present study, we identified organic compounds can inhibit the FIKK9.1 of Plasmodium falciparum 3D7. From docking analysis, seven compounds are predicted to be potential lead molecules for FIKK9.1. Out of seven compounds, compound 1 and 2 are significantly kills the parasites under in vitro conditions. The inhibitory effect on FIKK9.1 binding with ATP and phosphorylation of BSA in presence of compound 1/2 suggests, parasite death is occurred by chemical knock out of FIKK9.1. In conclusion, compounds target FIKK kinases could block the parasites survival and serves good platform to develop new class of antimalarials.

Materials and methods

Materials

RPMI1640 and gentamycin were purchased from Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA. AlbumaxR II (lipid-rich bovine serum albumin) was purchased from GIBCO, Grand Island, NY, USA. Solvents and other reagents used in this study are of analytical grade purity.

In vitro cultivation of Plasmodium falciparum 3D7

Plasmodium falciparum (3D7) was maintained in blood group A+ as described previously (Balaji et al. 2020).

Virtual screening of the compounds 1–4

FIKK9.1 molecular model was used to identify pharmacophoric environment for ATP binding and it was used to dock heterocyclic compounds (AK et al. 2021). The important ATP-binding residues were marked and the grid was set with default spacing of 0.375 Å and covers the angle of 40° on each coordinate of X, Y and Z. AutoDOCK4.1 was used for virtual screening of the compounds by setting the maximum number of evals and generation to 2,500,000 and 27,000, respectively, for 20 GA runs. Before proceeding with docking, the receptor and ligands were energy minimized through Swiss PDB viewer (sPDBV) and ChemBiodraw14, respectively. The interaction among ligands and receptors were analyzed through Ligplot + . Results of docking after analyzing are viewed using Pymol (Educational user module).

Generation of FIKK9.1 mutants and docking analysis

To validate the interaction of compound 1 and compound 2 with biophore residues of FIKK9.1, the most important residues were mutated with alanine and docking was carried out. To obtain mutated FIKK9.1, the structures of individual FIKK9.1 mutant were modeled using EasyModeller 4.0 GUI. The modeled FIKK9.1 mutant structures were energy minimized using swiss-PDBviewer v4.1 before performing docking analysis. The docking of ATP, Compound 1 and 2 in FIKK9.1 biophoric regions was carried out with similar coordinates used in virtual screening analysis. The binding energies of complexes were analyzed through AutoDOCK 4.1. For docking analysis of FIKK9.1 with heterocycles (1 and 2) in presence of ATP, the FIKK9.1-ATP complex structure was energy minimized and similar docking protocol was performed.

Molecular dynamic simulation analysis of FIKK9.1 and ligand complexes

The docked FIKK9.1-ligand (ATP, compound 1 and 2) complexes were used for molecular dynamics simulations. The CGenFF server is used to obtain topology file of ATP, compound 1 and 2. Charmm36_march2019 force field was used to perform simulations in GROMACS 4.6.5 package. The system is solvated by simple point charge (spc) water model and complexes were energy minimized in vacuum and water for 1 ns. In order to neutralize the protein, 19 chloride ions was included to the system. The production runs of 20 ns was performed for FIKK9.1-ligand (ATP, compound 1 and 2) complexes under NVT conditions. The MD trajectories of complexes after simulations were analyzed for Hydrogen bonding, radius of gyration (Rg), root mean square deviation (RMSD) and root mean square fluctuation (RMSF).

Isothermal calorimetry analysis of FIKK 9.1 with ATP, 1 and 2

In order to precisely understand synthesized organic compounds that could disrupt FIKK9.1 interaction with ATP, ITC experiments were performed using ITC200 microcalorimeter (microCal, Northampton, MA). ITC experiments were carried out at 30 °C under constant stirring speed of 800 rpm with reference power of 6 μcal/s. During each calorimetry measurement, 200 µM of ATP in the syringe was titrated with FIKK9.1 (7 µM) present in the sample cell. In case of inhibition assays, FIKK9.1 protein was preincubated with 1 (100 µM) or 2 (100 µM) for 10 min at 30 °C in a water bath, then the ATP was titrated. The ITC data were analyzed using Origin software (Northampton, MA).

Protein kinase assay

In a total volume of 250 µl assay mixture, BSA (100 µg/ml) was incubated with FIKK9.1 (60 µg/ml) in a 20 mM Tris pH7.4 reaction buffer contains 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2 at 37 °C in the presence and absence of the compounds 1 and 2. ATP (100 µM) was added to start the kinase reaction and allowed it to proceed for 30 min at 37 °C. The phosphorylation of BSA was determined by immunoblotting using anti-phosphoserine antibodies. The acquired signal was quantified using Image lab (Bio-Rad laboratories, USA).

Antimalarial activity assay

Antimalarial activity assay was performed as described previously (Vimee et al. 2019). Plasmodium falciparum (3D7) was synchronized using 5% D-sorbitol to obtain ring stage parasites. For antimalarial assay, 1% of ring stage parasites and 3% (final volume) of haematocrit was added to various compound concentrations (0–50 µg/ml) and incubated for 72 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2 incubator. Blood smears were taken after 40 h to examine the presence of schizont stage parasite and data used to calculate schizonticidal activity of drugs. Parasitemia was calculated by observing the number of viable parasites/1000 RBC’s for each concentration of drug.

Determination of the parasitostatic/parasitocidal nature

The compounds 1–4 were incubated with ring stage synchronized P. falciparum (3D7) parasitized cells at a range of drug concentrations from 0 µg/ml (control) to 50 µg/ml. After 42 h, the compounds 1–4 were removed by repeated washing with RPMI 1640 complete media and allowed the parasites to grow till 96 h in drug free medium. Blood smears were taken after 96 h to examine the presence of viable parasites and minimum concentration of 1–4 giving no viable parasite were used to calculate parasitocidal activity.

Microscopic imaging of parasite morphology

Giemsa stained thin smears of control as well as drug treated parasitized RBC were visualized under 100X objective in oil immersion and images were captured using a Nikon camera attached to the microscopy system.

Isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells

The PBMC’s were isolated from blood of healthy individual using HiSep 1077 (Himedia, India) density gradient method. The separation of the cells was based on manufacturer protocol. In brief, the blood was collected in anticoagulant solution and diluted with PBS in 1:1 ratio. The diluted blood was carefully overlay on top of the HiSep 1077. Then, the blood was centrifuged at 1000 × g in room temperature for 30 min. The PBC’s were resolved in between plasma and HiSep 1077 solution. The PBMC layer was carefully aspirated and performed cytotoxicity analysis.

Cytotoxicity analysis through MTT assay

The cytotoxic effect of heterocycles 1 and 2 were investigated using human embryonic kidney 293 cell line (HEK 293) at IC50 (3.5 µg/ml) and 2 × IC50 (7 µg/ml) concentrations. In a 96-well plate, cell density of 10,000 cells/well was incubated for 12 h to adhere. Compound stocks were made using incomplete media with 0.1% of DMSO as final concentrations. Incomplete media containing DMSO (0.2%) was used as a control. The prepared media containing different concentrations of drugs was added to the cells and incubated for 24 h. The images were taken at 10X using Cytell cell imaging system and the effect of the drugs was evaluated by calculating the cell survival using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazoyl-2-yl) 2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (mTT). After incubation, the media were removed, the cells were washed with PBS and media containing 20 µl of MTT (5 mg/ml) was added in the wells. The cells were incubated with MTT for 4 h at 37 °C and media was removed after incubation period. DMSO (100 µl) was added in each well to dissolve tetrazolium crystals. Finally, the absorbance was measured at 550 nm and 690 nm for standard reference. Similarly, the compounds were also evaluated for its cytotoxicity on isolated PBMC’s.

Chemical synthesis of heterocyclic compounds

General information

DMAP (≥ 99%) and 1,4-dithiane-2,5-diol (97%), N-iodosuccinamide (95%) and trifluoromethanesulfonic acid (98%), arylsulfonyl chlorides, aryl aldehydes, Cu(NO3)2·3H2O (98%) and Cu(OAc)2 (99%) of Aldrich and selenium (99.9%) of SRL were used as received. Aziridine1, 1,3-enyne2, sulfonyl hydrazides3 and substituted aminotetrazoles4 were prepared according to the reported procedure. SRL silica gel G/GF 254 plates were used for analytical TLC and SRL silica gel (60–120 mesh) was used for column chromatography. NMR spectra were recorded with Bruker Ascend 400 MHz spectrometer using CDCl3 as solvent and Me4Si as an internal standard. Chemical shifts (δ) and spin–spin coupling constant (J) are reported in ppm and in Hz, respectively, and other data are reported as follows: s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, m = multiplet, q = quartet, dd = doublet of doublets. Melting points were determined using a Büchi B-540 apparatus and are uncorrected. FT-IR spectra were collected on Perkin Elmer IR spectrometer. Q-Tof ESI–MS instrument (model HAB 273) was used for recording mass spectra. HPLC analysis was carried out using Shimadzu Prominence M20A DAD with Shimadzu-C18-250 mm X 4.6 mm I.D column using 30% water in CH3CN (flow rate = 1 ml/min).

Preparation of Isoselenocyanate.5 To a solution of the isocyanide6 (2 mmol, 308 mg) in CHCl3 (1 mL) were added selenium powder (3 mmol, 316 mg) and NEt3 (2 mmol, 0.3 mL) at room temperature under nitrogen and the mixture was stirred for 7 h. Progress of the reaction was monitored by TLC using hexane as eluent. The suspension was n passed through a short pad of celite and the solvent was removed by evaporation on a rotary evaporator. The residue was purified on a silica gel column chromatography using hexane as eluent.

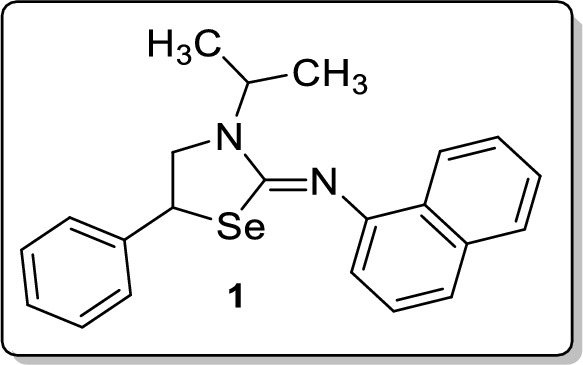

Synthesis of (Z)-3-Isopropyl-N-(naphthalen-1-yl)-5-phenyl-1,3-selenazolidin-2-imine 1

To a stirred solution of isoselenocyanatonaphthalene (0.2 mmol, 47 mg) and 1-isopropyl-2-phenylaziridine (0.24 mmol, 39 mg)) in CH2Cl2 (2 mL), was added CoCl2 (10 mol %, 2.6 mg) at room temperature. After 1 h, the reaction mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 (10 mL) and the aqueous phase was extracted with CH2Cl2 (2 × 10 mL). Drying (Na2SO4) and evaporation of the solvent gave a residue that was purified on silica gel column chromatography using ethyl acetate and hexane as an eluent. Analytical TLC on silica gel, 1:32 ethyl acetate/hexane; Rf = 0.32; yellow solid; mp 128–129 °C; yield 86% (67 mg); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.11–8.08 (m, 1H), 7.72–7.69 (m, 1H), 7.46 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.38–7.33 (m, 4H), 7.29–7.14 (m, 4H), 6.93 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 4.93–4.86 (m, 1H), 4.71 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 3.89–3.84 (m, 1H), 3.68–3.63 (m, 1H), 1.30 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 6H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 156.7, 150.2, 140.3, 134.3, 128.8, 128.8, 127.9, 127.8, 127.8, 126.1, 126.0, 125.2, 124.0, 123.3, 115.2, 54.2, 47.6, 42.2, 20.4, 19.7; FT-IR (KBr) 2971, 2926, 1623, 1584, 1570, 1503, 1453, 1389, 1363, 1278, 1245, 1207, 1184, 1066, 774, 795, 697 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C22H23N2Se: 395.1021, found: 395.1024; HPLC: 99.30% [Shimadzu C18-250 mm × 4.6 mm, water/CH3CN = 3:7, λmax = 290 nm, flow rate = 1 ml/min, tR = 18.77 min].

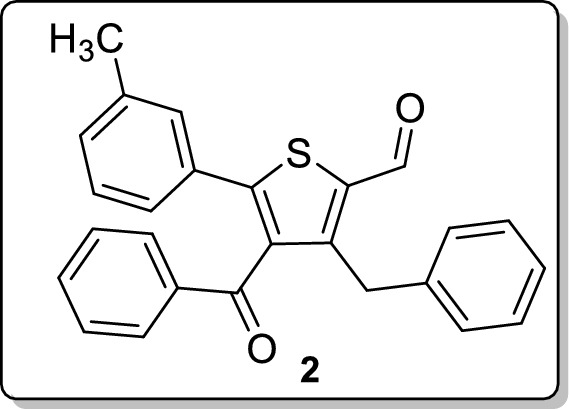

Synthesis of 4-Benzoyl-3-benzyl-5-(m-tolyl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde 2

To a stirred solution of 2-(3-methylbenzylidene)-1,4-diphenylbut-3-yn-1-one (0.2 mmol, 64 mg) and 1,4-dithiane-2,5-diol (0.2 mmol, 30 mg) in CH2Cl2 (2 mL), DMAP (0.4 mmol, 50 mg) was added at room temperature. After 6 h, the reaction mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 (10 mL), the organic layer was separated and the aqueous phase was extracted with CH2Cl2 (2 × 10 mL). Drying (Na2SO4) and evaporation of the solvent gave a residue that was purified on silica gel column chromatography using ethyl acetate and hexane as an eluent. Analytical TLC on silica gel, 1:49 ethyl acetate/hexane; Rf = 0.41; sticky yellow liquid; yield 73% (56 mg); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.13 (s, 1H), 7.49 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.32 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.16–6.98 (m, 11H), 4.33 (s, 2H), 2.19 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 194.4, 182.5, 152.9, 149.8, 139.0, 138.6, 138.3, 136.8, 133.4, 132.1, 130.4, 129.5, 129.4, 128.7, 128.7, 128.6, 128.2, 126.6, 125.8, 32.8, 21.2; FT-IR (neat) 2924, 2851, 1656, 1596, 1579, 1528, 1494, 1449, 1378, 1286, 1216, 1173, 1070, 781, 733, 691, 670, 644 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C26H21O2S: 397.1257, found: 397.1258; HPLC: 96.42% [Shimadzu C18-250 mm × 4.6 mm, water/CH3CN = 3:7, λmax = 290 nm, flow rate = 1 ml/min, tR = 25.44 min].

General procedure for the preparation of bisarylnitromethyl sulfones 3a–d

Aryl aldehyde (1 mmol) and arylsulfonyl hydrazide (1.1 mmol) were stirred in CH2Cl2 (2 mL) under reflux for an hour. The mixture was then treated with Cu(NO3)3·9H2O (40 mol %) and molecular sieves (4 Å) and stirring was continued an additional 2 h under reflux. After completion, the residue was treated with saturated NaHCO3 (3 mL) and diluted with ethyl acetate (3 × 10 mL). The combined organic solution was successively washed with brine (1 × 10 mL) and water (1 × 10 mL). Drying (Na2SO4) and evaporation of the solvent gave a residue that was purified on silica gel column chromatography using ethyl acetate and hexane as an eluent.

1-Bromo-2-methoxy-3-(nitro(tosyl)methyl)benzene 3a

Analytical TLC on silica gel, 1:4 ethyl acetate/hexane; Rf = 0.34; colorless solid; mp 154–155 °C; yield 59% (235 mg); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.76 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.69 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.56–7.54 (m, 1H), 7.37 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.12 (s, 1H), 6.80 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 3.76 (s, 3H), 2.48 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 157.0, 147.0, 135.9, 132.8, 131.8, 130.5, 130.0, 115.6, 113.2, 112.8, 95.0, 56.4, 21.9; FT-IR (KBr) 2974, 1595, 1561, 1487, 1462, 1405, 1341, 1307, 1280, 1261, 1186, 1117, 1084, 813 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) m/z [M + Na]+ calcd for C15H14BrNO5SNa: 421.9668, found: 421.9668.

2-(((4-chlorophenyl)(nitro)methyl)sulfonyl)-1,3,5-trimethylbenzene 3b

Analytical TLC on silica gel, 1:4 ethyl acetate/hexane; Rf = 0.39; colorless solid; mp 164–165 °C; yield 61% (215 mg); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.60 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.45 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.00 (s, 2H), 6.42 (s, 1H), 2.53 (s, 6H), 2.34 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 145.7, 142.0, 138.4, 132.9, 132.03, 129.4, 129.2, 123.3, 102.4, 23.14, 21.3; FT-IR (KBr) 2986, 1598, 1561, 1492, 1453, 1411, 1338, 1288, 1153, 1094, 837 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) m/z [M + Na]+ calcd for C16H16ClNO4SNa: 376.0381, found: 376.0385.

2-(Nitro(tosyl)methyl)naphthalene 3c

Analytical TLC on silica gel, 1:9 ethyl acetate/hexane; Rf = 0.45; colorless solid; mp 175–176 °C; yield 63% (214 mg); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.95 (s, 1H), 7.88–7.81 (m, 3H), 7.62 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.58–7.51 (m, 2H), 7.29 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 6.62 (s, 1H), 2.45 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 146.9, 134.5, 132.7, 131.3, 130.8, 130.7, 129.9, 129.0, 128.8, 128.3, 127.9, 127.2, 125.3, 122.5, 104.1, 21.9; FT-IR (KBr) 2982, 1595, 1560, 1509, 1339, 1306, 1155, 1083, 815, 754 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) m/z [M + Na]+ calcd for C18H15NO4SNa: 364.0614, found: 364.0610.

2-(((4-methoxyphenyl)(nitro)methyl)sulfonyl)-1,3,5-trimethylbenzene 3d

Analytical TLC on silica gel, 1:4 ethyl acetate/hexane; Rf = 0.49; colorless solid; mp 134–135 °C; yield 55% (191 mg); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.57 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.98–6.93 (m, 4H), 6.40 (s, 1H), 3.84 (s, 3H), 2.52 (s, 6H), 2.33 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 162.4, 145.3, 142.0, 132.7, 132.3, 129.6, 116.7, 114.5, 103.1, 55.6, 23.1, 21.3; FT-IR (KBr) 2971, 1685, 1607, 1560, 1513, 1457, 1382, 1334, 1309, 1257, 1182, 1153, 1115, 1030, 839 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) m/z [M + Na]+ calcd for C17H19NO5SNa: 372.0876, found: 372.0874.

Preparation of 1-(2-chlorophenyl)-N-(2-iodo-4-methylphenyl)-1H-tetrazol-5-amine 4

To a stirred solution of 1-(2-chlorophenyl)-N-(p-tolyl)-1H-tetrazol-5-amine (0.4 mmol, 114 mg) Cu(OAc)2 (10 mol %, 7.24 mg) and NIS (1.2 mmol, 178 mg) in (CH2Cl)2 (3 mL), was added CF3SO3H (10 mol %, 2.6 mg) and the mixture was refluxed for 6 h. The reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and diluted with CH2Cl2 (10 mL) and the aqueous phase was extracted with CH2Cl2 (2 × 10 mL). Drying (Na2SO4) and evaporation of the solvent gave a residue that was purified on silica gel column chromatography using ethyl acetate and hexane as an eluent. Analytical TLC on silica gel, 1:9 ethyl acetate/hexane; Rf = 0.48; colorless solid; mp 109–110 °C; yield 68% (111 mg); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.48 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 8.09 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.49 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 7.38–7.34 (m, 2H), 7.19 (s, 1H), 7.15–7.12 (m, 1H), 7.05–7.01 (m, 1H), 2.55 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 150.8, 145.0, 141.2, 134.6, 132.7, 129.2, 128.4, 125.0, 123.9, 122.5, 121.6, 119.1, 103.2, 28.4; FT-IR (KBr) 3385, 1601, 1563, 1521, 1481, 1470, 1452, 1317, 1232, 1087, 1052, 1034, 1017, 818, 750 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C14H12ClIN5: 411.9820, found: 411.9820.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

References

- AK D et al (2021) Plasmodium falciparum FIKK9.1 is a monomeric serine-threonine protein kinase with features to exploit as a drug target. Chem Biol Drug Des. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Arendse LB et al (2021) Plasmodium kinases as potential drug targets for malaria: challenges and opportunities. ACS Infect Dis [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Balaji SN, Sahasrabuddhe AA, Trivedi V. Insulin signalling in RBC is responsible for growth stimulation of malaria parasite in diabetes patients. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2020;528(3):531–537. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.05.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batinovic S, et al. An exported protein-interacting complex involved in the trafficking of virulence determinants in Plasmodium-infected erythrocytes. Nat Commun. 2017;8:16044. doi: 10.1038/ncomms16044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S, et al. Evidence of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Eastern India. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(20):1962–1964. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1713777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies H, et al. An exported kinase family mediates species-specific erythrocyte remodelling and virulence in human malaria. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5(6):848–863. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0702-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldar K, Bhattacharjee S, Safeukui I. Drug resistance in Plasmodium. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16(3):156–170. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin BC, et al. FIKK Kinase, a Ser/Thr kinase important to malaria parasites, is inhibited by tyrosine kinase inhibitors. ACS Omega. 2017;2(10):6605–6612. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.7b00997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin BC, et al. The anthraquinone emodin inhibits the non-exported FIKK kinase from Plasmodium falciparum. Bioorg Chem. 2017;75:217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2017.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menard D, Dondorp A (2017) Antimalarial drug resistance: a threat to malaria elimination. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 7(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mnzava AP, et al. Malaria vector control at a crossroads: public health entomology and the drive to elimination. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2014;108(9):550–554. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/tru101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moxon CA, Grau GE, Craig AG. Malaria: modification of the red blood cell and consequences in the human host. Br J Haematol. 2011;154(6):670–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08755.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nsanzabana C (2019) Resistance to artemisinin combination therapies (ACTs): do not forget the partner drug! Trop Med Infect Dis 4(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nunes MC, et al. Plasmodium falciparum FIKK kinase members target distinct components of the erythrocyte membrane. PLoS One. 2010;5(7):e11747. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organization W.H. (2020) World malaria report 2020: 20 years of global progress and challenges.

- Pousibet-Puerto J, et al. Impact of using artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) in the treatment of uncomplicated malaria from Plasmodium falciparum in a non-endemic zone. Malar J. 2016;15(1):339. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1408-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rug M, et al. Export of virulence proteins by malaria-infected erythrocytes involves remodeling of host actin cytoskeleton. Blood. 2014;124(23):3459–3468. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-06-583054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui G, Proellochs NI, Cooke BM. Identification of essential exported Plasmodium falciparum protein kinases in malaria-infected red blood cells. Br J Haematol. 2020;188(5):774–783. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuteja R. Malaria—an overview. FEBS J. 2007;274(18):4670–4679. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayan RS, et al. Conformational analysis of the DFG-out kinase motif and biochemical profiling of structurally validated type II inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2015;58(1):466–479. doi: 10.1021/jm501603h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vimee R, et al. Virtual screening, molecular modelling and biochemical studies to exploit PF14_0660 as a target to identify novel anti-malarials. Lett Drug Des Discov. 2019;16(4):417–426. doi: 10.2174/1570180815666180727121200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ward P, et al. Protein kinases of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum: the kinome of a divergent eukaryote. BMC Genom. 2004;5:79. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-5-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.