Abstract

Background

Compared to the general population, cancer patients are at higher risk of morbidity and mortality following SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. The immune response to a two‐dose regimen of mRNA vaccines in cancer patients is generally lower than in immunocompetent individuals. Booster doses may meaningfully augment immune response in this population. We conducted an observational study with the primary objective of determining the immunogenicity of vaccine dose three (100 μg) of mRNA‐1273 among cancer patients and a secondary objective of evaluating safety at 14 and 28 days.

Methods

The mRNA‐1273 vaccine was administered ∼7 to 9 months after administering two vaccine doses (i.e., the primary series). Immune responses (enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA]) were assessed 28 days post‐dose three. Adverse events were collected at days 14 (± 5) and 28 (+5) post‐dose three. Fisher exact or X2 tests were used to compare SARS‐CoV‐2 antibody positivity rates, and paired t‐tests were used to compare SARS‐CoV‐2 antibody geometric mean titers (GMTs) across different time intervals.

Results

Among 284 adults diagnosed with solid tumors or hematologic malignancies, dose three of mRNA‐1273 increased the percentage of patients seropositive for SARS‐CoV‐2 antibody from 81.7% pre‐dose three to 94.4% 28 days post‐dose three. GMTs increased 19.0‐fold (15.8‐22.8). Patients with lymphoid cancers or solid tumors had the lowest and highest antibody titers post–dose three, respectively. Antibody responses after dose three were reduced among those who received anti‐CD20 antibody treatment, had lower total lymphocyte counts and received anticancer therapy within 3 months. Among patients seronegative for SARS‐CoV‐2 antibody pre‐dose three, 69.2% seroconverted after dose three. A majority (70.4%) experienced mostly mild, transient adverse reactions within 14 days of dose three, whereas severe treatment‐emergent events within 28 days were very rare (<2%).

Conclusion

Dose three of the mRNA‐1273 vaccine was well‐tolerated and augmented SARS‐CoV‐2 seropositivity in cancer patients, especially those who did not seroconvert post–dose two or whose GMTs significantly waned post–dose two. Lymphoid cancer patients experienced lower humoral responses to dose three of the mRNA‐1273 vaccine, suggesting that timely access to boosters is important for this population.

Keywords: Cancer, Coronavirus disease 2019, Immunogenicity, Observational study, Vaccination

Abbreviations

- ACIP

Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices

- BTK

Bruton's tyrosine kinase

- CAR‐T

chimeric antigen receptor T‐cell

- COVID‐19

coronavirus disease 2019

- ELISA

enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay

- GMTs

geometric mean titers

- HM

hematologic malignancies

- IgA

immunoglobulin A

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- IgM

immunoglobulin M

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- MCC

Moffitt Cancer Center

- STROBE

STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational Studies in Epidemiology

1. INTRODUCTION

Patients diagnosed with cancer are at higher risk of morbidity and mortality following SARS‐CoV‐2 infection than the general population [1]. We and others have previously demonstrated that immune responses following two doses of a COVID‐19 vaccine induce highly variable SARS‐CoV‐2 antibody seroconversion rates, with lower geometric mean titers (GMTs) in this population than in healthy adults [2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]. Generally, there is strong evidence supporting the waning clinical efficacy of an initial series of COVID‐19 vaccination at approximately 6 months, an observation that may relate to reduced duration of humoral response, particularly in older adults [10, 11]. Within the cancer patient population specifically, loss of or reduction in humoral response following the initial series of COVID‐19 vaccination may be even more pronounced [12]. These data suggest that patients diagnosed with cancer could benefit from dose three of the COVID‐19 vaccine.

We previously conducted an observational study to evaluate the safety and immunogenicity of a two‐dose regimen of 100 μg of mRNA‐1273 vaccine (Moderna) in cancer patients diagnosed with solid tumors and hematologic malignancies (HM) [2]. In a follow‐up to this, we conducted a second observational study with the primary objective of determining the immunogenicity of dose three of the mRNA‐1273 vaccine in cancer patients. Herein, we report on both immunogenicity and safety results through day 28 after dose three. In this report, we also describe a sub‐cohort of cancer patients who participated in both observational studies, allowing for an immune response assessment after each of the three vaccine doses.

2. METHODS

2.1. Subject eligibility and consent

All cancer patients enrolled in this observational study (n = 284) had a documented history of previously receiving two doses of mRNA‐1273 approximately one month apart between January and March of 2021 at Moffitt Cancer Center (MCC; Tampa, Florida, United States of America). A subset of patients (n = 130) also had participated in an earlier study of a two‐dose regimen, in which seroconversion (to SARS‐CoV‐2 antibody positivity) and SARS‐CoV‐2 GMTs pre‐vaccination and post‐vaccine doses one and two were available for analysis, henceforth referred to as Cohort 1 [2]. Other analyzed cohorts included the subset of patients who were SARS‐CoV‐2 antibody‐negative prior to dose 3 and the subset of patients who remained antibody‐negative following dose 3. Key eligibility criteria included: (1) 18 years of age or older; (2) documented cancer history; (3) completed two mRNA‐1273 vaccine series prior to March 31, 2021; and (4) had no known or suspected allergy or history of anaphylaxis, urticaria, or other significant adverse reaction to the vaccine or its excipients. The study was approved by the Advarra Institutional Review Board (IRB) per protocol Pro00056961. All patients provided written informed consent. This study followed the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines.

2.2. Study procedures and data collection

A third 100 μg dose of mRNA‐1273 was administered intramuscularly to each patient between October and December 2021. Dose three administration was consistent with emergency use authorization published by the United States Federal Drug Administration on August 12, 2021, for a third 100 μg dose to be administered at least 28 days following the two‐dose regimen, which was issued two months prior to the start of the study enrolment. For the purposes of determining the primary study objective (immunogenicity), serum samples were collected immediately prior to administration of dose three and on day 28 post–dose three (+ 14 days). For the secondary objective, safety data were collected 14 days (±5) and 28 days (+14 days) post‐vaccination using a standardized questionnaire administered by staff interview of vaccine recipients (Supplementary Materials). Data collected included local and systemic reactions and serious adverse events. In addition, an electronic health record review was conducted for all patients to validate patient‐reported adverse events and to determine any laboratory‐defined adverse events within this timeframe (28 days + 14 days after vaccine dose three).

2.3. Assay for SARS‐COV‐2 antibody detection and quantification

The enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) used to assess immunogenicity has been previously described [2]. The human SARS‐COV‐2 serology standard provided by the Frederick National Laboratory (National Institute of Health) was used to quantify GMTs. The assay's limit of detection (above which was defined as a positive result) was calculated as the mean optical density of pooled negative control sera plus 3 standard deviations. The mean concentration at the limit of detection was 25 AU/mL.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics (proportions and frequencies for categorical variables and medians [ranges] for continuous variables) were used to summarize patient characteristics. The primary study objective was to assess immunogenicity following dose three of the mRNA‐1273 vaccine. To enable a quantitative estimate of an immune response, antibody‐negative patients were assigned an imputed value of 12.5, which was halfway between 0 and the assay's detection limit (25 AU/mL). Binding antibody IgG geometric mean titers (GMTs) and their 95% confidence intervals were calculated based on log10‐transformed titers and t‐distribution, then transformed back to the original scale. The 95% confidence intervals of fold change were calculated based on the t‐distribution of the difference in the log10‐transformed titers, then transformed back to the original scale. Fisher exact or x2 tests were used to compare SARS‐CoV‐2 antibody positivity rates across patient characteristics; the Fisher exact test was used when any of the cell counts were <5. The Kruskal‐Wallis test was used to evaluate the association between SARS‐CoV‐2 GMTs and patient characteristics. Paired t‐tests were used to compare SARS‐CoV‐2 GMTs ∼7 to 9 months after dose two to levels 29 days after dose three. Observations with missing data were removed from the analyses. All analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc) and R software, version 4.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Two‐sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patient characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the entire population and Cohort 1 are depicted in Table 1. A total of 284 patients diagnosed with cancer were included in the study, among whom 157 (55.3%) were diagnosed with HM and 127 (44.7%) with solid tumor malignancies. All received dose three of mRNA‐1273 between August 24, 2021, and December 17, 2021, ∼7 to 9 (median of 7.4) months after the second dose. The median age of participants at the time of dose three was 67 years, and 46.5% were female; 90.8% of patients were White, 5.3% were Black, and 7.0% were Hispanic. Only 2 of the overall study participants (n = 284) reported SARS‐CoV‐2 infection prior to receipt of dose 3 of mRNA‐1273.

TABLE 1.

Study population demographics of all cancer study patients and cohort 1 sub‐population.

| Characteristics | All cancer patients (n = 284) | Cohort 1 sub‐population ¶ (n = 130) |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Time interval (months) from the second dose to dose three (median, range) | 7.4 (6.8‐9.0) | 7.4 (6.9‐9.0) |

| Age group (median age 67 years) | ||

| ≤67 years | 145 (51.1) | 73 (56.2) |

| >67 years | 139 (48.9) | 57 (43.8) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 152 (53.5) | 68 (52.3) |

| Female | 132 (46.5) | 62 (47.7) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 20 (7.0) | 5 (3.8) |

| Non‐Hispanic | 264 (93.0) | 125 (96.2) |

| Race | ||

| White | 258 (90.8) | 124 (95.4) |

| Black | 15 (5.3) | 4 (3.1) |

| Asian | 3 (1.1) | 1 (0.8) |

| Other | 8 (2.8) | 1 (0.8) |

| Primary patient category | ||

| Hematological malignancies | 157 (55.3) | 82 (63.1) |

| Myeloid disorders | 38 (24.2) | 19 (23.2) |

| Lymphoid disorders | 67 (42.7) | 35 (42.7) |

| Plasma cell disorders | 52 (33.1) | 28 (34.1) |

| Solid tumors | 127 (44.7) | 48 (36.9) |

| Disease status | ||

| Previously untreated | 23 (8.1) | 7 (5.4) |

| Remission | 171 (60.2) | 95 (73.1) |

| Relapse/refractory/stable disease | 90 (31.7) | 28 (21.5) |

| Lymphocyte count a | ||

| >1 × 109/L | 152 (65.0) | 67 (67.0) |

| ≤1 × 109/L | 82 (35.0) | 33 (33.0) |

| Among Plasma Cell Disorders | ||

| IgG level a | ||

| <700 mg/dL | 28 (56.0) | 16 (59.3) |

| ≥700 mg/dL | 22 (44.0) | 11 (40.7) |

| IgA level a | ||

| <70 mg/dL | 26 (52.0) | 14 (51.9) |

| ≥70 mg/dL | 24 (48.0) | 13 (48.1) |

| IgM level a | ||

| <40 mg/dL | 40 (80.0) | 20 (74.1) |

| ≥40 mg/dL | 10 (20.0) | 7 (25.9) |

| Received anticancer therapy within 3 months b | ||

| No | 160 (56.3) | 75 (57.7) |

| Yes | 124 (43.7) | 55 (42.3) |

| Small molecules c | ||

| No | 227 (79.9) | 98 (75.4) |

| Yes | 57 (20.1) | 32 (24.6) |

| Anti‐CD20 antibodies within 6 months | ||

| No | 273 (96.1) | 124 (95.4) |

| Yes | 11 (3.9) | 6 (4.6) |

| Anti‐CD38 antibodies within 6 months | ||

| No | 270 (95.1) | 120 (92.3) |

| Yes | 14 (4.9) | 10 (7.7) |

| Patients treated with cellular therapy | ||

| No | 243 (85.6) | 104 (80.0) |

| Yes | 41 (14.4) | 26 (20.0) |

| Patients treated with cellular therapy type | ||

| Allo‐HSCT any time prior to vaccination | 22 (53.7) | 14 (53.8) |

| Auto‐HSCT within the past 24 months | 13 (31.7) | 8 (30.8) |

| CD19 CAR‐T any time prior to vaccination | 5 (12.2) | 3 (11.5) |

| BCMA CAR‐T any time prior to vaccination | 1 (2.4) | 1 (3.8) |

| BTK inhibitors | ||

| No | 278 (97.9) | 129 (99.2) |

| Yes | 6 (2.1) | 1 (0.8) |

| Line of systemic therapy to date | ||

| 0 | 67 (23.6) | 23 (17.7) |

| 1 | 115 (40.5) | 54 (41.5) |

| ≥2 | 102 (35.9) | 53 (40.8) |

| SARS‐CoV‐2 infection prior to vaccine dose 1 | ||

| Yes | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.8) |

| No/unknown | 283 (99.6) | 129 (99.2) |

All lab assessments were within 3 months before dose three of the vaccine, and 17.6% of total patients had missing lymphocyte count data. Among patients with plasma cell disorders, 3.8% had missing IgG values, 3.8% had missing IgA values, and 3.8% had missing IgM values.

Anti‐androgen and anti‐estrogen hormonal therapies were not considered anticancer therapy for this study.

Small molecules include tyrosine kinase inhibitors, proteasome inhibitors, lenalidomide, pomalidomide, and venetoclax.

The 3‐dose cohort includes the subset of patients who had safety and immunogenicity data after doses 1, 2, and 3.

In total, 60.2% of all HM and solid tumor patients were in remission, and 65.0% had a lymphocyte count >1 × 109/mL at the time of receipt of dose three of the vaccine (Table 1). Among the 157 patients diagnosed with HM, 24.2% had myeloid disorders, 42.7% had lymphoid disorders, and 33.1% had plasma cell disorders/malignancies.

3.2. Adverse events

Dose three of mRNA‐1273 was generally well tolerated (Table 2). The most common adverse event reported within 14 days (± 5 days) and 28 days (+14 days) of dose three was mild injection site pain (reported by 51.1% and 5.6% of patients 14‐ and 28‐days post–dose three, respectively). The next most common adverse events 14 days post–dose three included mild tiredness (18.0%), injection site redness/hardness (12.7%), and mild headache (12.3%). There were only 4 patients (1.4%) with protocol‐defined severe adverse events, none of which were deemed related to the vaccine. No treatment‐emergent laboratory adverse events were observed.

TABLE 2.

Solicited local and systemic adverse events (AE) within 14 days and 28 days of receipt of dose 3 (n = 284).

| No. patients (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Day 14 (+5 days) | Day 28 (+14 days) |

| Any symptoms | 200 (70.4) | 38 (13.4) |

| Fever | 44 (15.5) | 7 (2.5) |

| Injection site pain | ||

| Mild | 145 (51.1) | 16 (5.6) |

| Mild‐Moderate | 26 (9.2) | 3 (1.1) |

| Moderate | 4 (1.4) | 0 (0) |

| Severe | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Arm swelling | ||

| Mild | 22 (7.7) | 2 (0.7) |

| Mild‐Moderate | 10 (3.5) | 1 (0.4) |

| Moderate | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Severe | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Injection site redness/hardness | ||

| Mild | 36 (12.7) | 4 (1.4) |

| Mild‐Moderate | 7 (2.5) | 1 (0.4) |

| Moderate | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) |

| Severe | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Chills | ||

| Mild | 26 (9.2) | 3 (1.1) |

| Mild‐Moderate | 10 (3.5) | 0 (0) |

| Moderate | 11 (3.9) | 1 (0.4) |

| Severe | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Tiredness | ||

| Mild | 51 (18.0) | 6 (2.1) |

| Mild‐Moderate | 37 (13.0) | 5 (1.8) |

| Moderate | 17 (6.0) | 3 (1.1) |

| Severe | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Headache | ||

| Mild | 35 (12.3) | 3 (1.1) |

| Mild‐Moderate | 7 (2.5) | 4 (1.4) |

| Moderate | 8 (2.8) | 1 (0.4) |

| Severe | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Chest pressure/discomfort | ||

| Mild | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Mild‐Moderate | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) |

| Moderate | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Severe | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Dyspnoea/shortness of breath | ||

| Mild | 4 (1.4) | 0 (0) |

| Mild‐Moderate | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Moderate | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Severe | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Palpitations (fast/irregular heartbeat) | ||

| Mild | 5 (1.8) | 0 (0) |

| Mild‐Moderate | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) |

| Moderate | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Severe | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Joint pain/aches | ||

| Mild | 13 (4.6) | 0 (0) |

| Mild‐Moderate | 9 (3.2) | 3 (1.1) |

| Moderate | 6 (2.1) | 1 (0.4) |

| Severe | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Nausea | ||

| Mild | 12 (4.2) | 0 (0) |

| Mild‐Moderate | 3 (1.1) | 0 (0) |

| Moderate | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0) |

| Severe | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Swelling of lymph node under injection arm | ||

| Mild | 4 (1.4) | 0 (0) |

| Mild‐Moderate | 3 (1.1) | 1 (0.4) |

| Moderate | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) |

| Severe | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Muscle pain/aches | ||

| Mild | 15 (5.3) | 2 (0.7) |

| Mild‐Moderate | 11 (3.9) | 2 (0.7) |

| Moderate | 9 (3.2) | 1 (0.4) |

| Severe | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 32 (11.3) | 5 (1.8) |

Participant‐reported severity was assessed as: Mild: aware of but easily tolerated; Mild‐Moderate: discomfort enough to cause interference with usual activities; Moderate: incapacitating, unable to work or do activities; Severe: requires emergency room visit or hospitalization.

3.3. Serum antibody concentrations increase after vaccine dose three

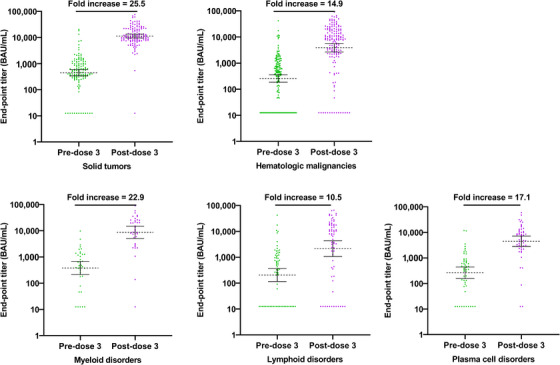

Overall, 81.7% of patients diagnosed with cancer were SARS‐CoV‐2 antibody seropositive ∼7 to 9 (median of 7.4) months after vaccine dose two, with seropositivity ranging from 64.2% for lymphoid cancer patients to 89.8% for solid tumor cancer patients (Table 3). Twenty‐eight days post–dose three, 94.4% of all study patients were seropositive, with percentages ranging from 82.1% for lymphoid cancer patients to 99.2% for solid tumor cancer patients. Overall, the GMT increased from 330.0 AU/mL pre–dose three to 6263.2 AU/mL post–dose three, a 19‐fold (range, 15.8‐22.8) titer increase. No differences in response to vaccine dose three were observed by age or gender (Table 3). As shown in Figure 1, pre–dose three and post–dose three antibody titers were highly variable among patients diagnosed with solid tumors as well as those with HM. Regardless of initial titer prior to dose three, all patient groups demonstrated a ≥10‐fold increase in titer post–dose three (ranging from 10.5‐fold for lymphoid patients to 25.5‐fold for solid tumor patients). No difference in GMTs was observed based on the patient's disease status (previously untreated, in remission, or relapsed, refractory, or stable disease).

TABLE 3.

Percent SARS‐CoV‐2 antibody seropositive and geometric mean titer pre‐vaccination and following receipt of vaccine dose three by cancer patient category and cancer treatment (n = 284).

| % of SARS‐CoV‐2 antibody seropositive patients (95% CI) | GMTs, AU/mL (95% CI) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | n | Pre‐Dose 3 | Post‐Dose 3 | P value* | Pre‐Dose 3 | Post‐Dose 3 | P value** | Fold increase |

| Overall | 284 | 81.7 (76.7‐86.0) | 94.4 (91.0‐96.8) | 330.0 (265.3‐410.5) | 6,263.2 (5,003.4‐7,840.2) | 19.0 (15.8‐22.8) | ||

| Age group (median age 66 years) | 0.264 | 0.790 | ||||||

| ≤67 | 145 | 86.2 (79.5‐91.4) | 95.9 (91.2‐98.5) | 442.7 (332.8‐588.8) | 6,536.7 (4,832.4‐8,842.2) | 14.8 (11.7‐18.6) | ||

| >67 | 139 | 77.0 (69.1‐83.7) | 92.8 (87.2‐96.5) | 242.9 (175.0‐337.1) | 5,990.0 (4,275.4‐8,392.2) | 24.7 (18.7‐32.6) | ||

| Gender | 0.420 | 0.621 | ||||||

| Male | 152 | 80.9 (73.8‐86.8) | 95.4 (90.7‐98.1) | 288.6 (214.1‐389.0) | 6,884.6 (5,161.6‐9,182.8) | 23.9 (18.4‐30.9) | ||

| Female | 132 | 82.6 (75.0‐88.6) | 93.2 (87.5‐96.8) | 385.1 (279.1‐531.3) | 5,616.7 (3,940.1‐8,006.8) | 14.6 (11.3‐18.8) | ||

| Ethnicity | 0.313 | 0.861 | ||||||

| Hispanic | 20 | 75.0 (50.9‐91.3) | 90.0 (68.3‐98.8) | 270.5 (109.0‐671.4) | 4,507.2 (1,502.5‐1,3520.5) | 16.7 (7.4‐37.5) | ||

| Non‐Hispanic | 264 | 82.2 (77.0‐86.6) | 94.7 (91.3‐97.1) | 335.0 (267.2‐420.0) | 6,421.2 (5,107.0‐8,073.7) | 19.2 (15.9‐23.1) | ||

| Race | 0.794 | 0.071 | ||||||

| White | 258 | 80.2 (74.8‐84.9) | 94.2 (90.6‐96.7) | 308.9 (244.5‐390.3) | 5,968.6 (4,704.5‐7,572.4) | 19.3 (15.9‐23.5) | ||

| Black | 15 | 93.3 (68.1‐99.8) | 93.3 (68.1‐99.8) | 504.8 (225.2‐1,131.6) | 6,296.3 (2,120.4‐18,696.2) | 12.5 (6.3‐24.6) | ||

| Asian | 3 | 100.0 (29.2‐100.0) | 100.0 (29.2‐100.0) | 1,430.7 (433.7‐4,719.6) | 26,357.2 (3,548.1‐195,793.7) | 18.4 (7.7‐44.1) | ||

| Other | 8 | 100.0 (63.1‐100.0) | 100.0 (63.1‐100.0) | 722.6 (300.1‐1,740.0) | 17,107.3 (7,236.6‐40,441.2) | 23.7 (12.3‐45.7) | ||

| Primary patient category ¶ | 0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Hematological malignancies # | 157 | 75.2 (67.6‐81.7) | 90.4 (84.7‐94.6) | 0.011 | 257.9 (186.2‐357.4) | 3,851.6 (2,669.9‐5,556.4) | 0.048 | 14.9 (11.5‐19.4) |

| Myeloid disorders | 38 | 86.8 (71.9‐95.6) | 97.4 (86.2‐99.9) | 378.5 (213.0‐672.8) | 8,682.5 (5,022.8‐15,008.8) | 22.9 (13.4‐39.4) | ||

| Lymphoid disorders | 67 | 64.2 (51.5‐75.5) | 82.1 (70.8‐90.4) | 204.4 (115.0‐363.2) | 2,150.2 (1,066.7‐4,334.4) | 10.5 (7.0‐15.9) | ||

| Plasma cell disorders | 52 | 80.8 (67.5‐90.4) | 96.2 (86.8‐99.5) | 263.0 (156.4‐442.4) | 4,506.7 (2,813.4‐7,219.2) | 17.1 (11.0‐26.7) | ||

| Solid tumors | 127 | 89.8 (83.1‐94.4) | 99.2 (95.7‐100.0) | 447.5 (341.4‐586.6) | 11,424.2 (9,623.4‐13,562.0) | 25.5 (20.1‐32.5) | ||

| Disease status | 0.617 | 0.790 | ||||||

| Previously untreated | 23 | 82.6 (61.2‐95.0) | 100.0 (85.2‐100.0) | 351.0 (145.6‐846.2) | 7,630.6 (4,575.1‐12,726.6) | 21.7 (12.0‐39.3) | ||

| Remission | 171 | 84.2 (77.9‐89.3) | 94.2 (89.5‐97.2) | 393.0 (300.3‐514.2) | 6,578.6 (4,946.4‐8,749.3) | 16.7 (13.5‐20.8) | ||

| Relapse/refractory/stable disease | 90 | 76.7 (66.6‐84.9) | 93.3 (86.1‐97.5) | 233.1 (154.7‐351.2) | 5,424.2 (3,468.6‐8,482.5) | 23.3 (15.9‐34.0) | ||

| Lymphocyte count a | 0.002 | <0.001 | ||||||

| >1 × 109/L | 152 | 85.5 (78.9‐90.7) | 97.4 (93.4‐99.3) | 401.1 (301.6‐533.6) | 8,950.2 (7,009.2‐11,428.7) | 22.3 (17.5‐28.4) | ||

| ≤1 × 109/L | 82 | 67.1 (55.8‐77.1) | 85.4 (75.8‐92.2) | 179.8 (111.8‐289.1) | 2,248.5 (1,272.2‐3,974.1) | 12.5 (8.5‐18.4) | ||

| Among plasma cell disorders | ||||||||

| IgG level a | 0.497 | 0.004 | ||||||

| <700 mg/dL | 28 | 78.6 (59.0‐91.7) | 92.9 (76.5‐99.1) | 201.6 (100.4‐404.8) | 2,447.6 (1,186.5‐5,049.1) | 12.1 (7.1‐20.8) | ||

| ≥700 mg/dL | 22 | 81.8 (59.7‐94.8) | 100 (84.6‐100.0) | 333.7 (137.4‐810.3) | 9,185.8 (5,442.2‐15,504.8) | 27.5 (12.4‐61.4) | ||

| IgA level a | 0.491 | 0.001 | ||||||

| <70 mg/dL | 26 | 73.1 (52.2‐88.4) | 92.3 (74.9‐99.1) | 164.1 (72.2‐373.4) | 2,098.1 (956.4‐4,602.9) | 12.8 (6.4‐25.7) | ||

| ≥70 mg/dL | 24 | 87.5 (67.6‐97.3) | 100 (85.8‐100.0) | 399.8 (200.9‐795.6) | 9,721.6 (6,490.7‐14,560.8) | 24.3 (13.1‐45.1) | ||

| IgM level a | 0.363 | 0.048 | ||||||

| <40 mg/dL | 40 | 80.0 (64.4‐90.9) | 97.5 (86.8‐99.9) | 219.9 (122.7‐394.2) | 3,914.6 (2,399.9‐6,385.5) | 17.8 (10.5‐30.3) | ||

| ≥40 mg/dL | 10 | 80.0 (44.4‐97.5) | 90.0 (55.5‐99.7) | 431.4 (93.8‐1,984.0) | 6,864.0 (1,246.9‐37,784.3) | 15.9 (5.3‐48.2) | ||

| Received anticancer therapy within 3 months b | 0.017 | <0.001 | ||||||

| No | 160 | 90.6 (85.0‐94.7) | 97.5 (93.7‐99.3) | 509.2 (394.6‐657.1) | 9,448.7 (7,566.2‐11,799.5) | 18.6 (15.0‐23.0) | ||

| Yes | 124 | 70.2 (61.3‐78.0) | 90.3 (83.7‐94.9) | 188.6 (132.0‐269.3) | 3,684.5 (2,439.2‐5,565.5) | 19.5 (14.2‐26.9) | ||

| Small molecules c | 0.747 | <0.001 | ||||||

| No | 227 | 84.6 (79.2‐89.0) | 93.8 (89.9‐96.6) | 393.9 (310.8‐499.1) | 7,242.1 (5,633.0‐9,310.8) | 18.4 (15.1‐22.4) | ||

| Yes | 57 | 70.2 (56.6‐81.6) | 96.5 (87.9‐99.6) | 163.1 (97.4‐273.1) | 3,512.5 (2,159.7‐5,712.8) | 21.5 (13.7‐34.0) | ||

| Anti‐CD20 antibodies | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| No | 273 | 83.5 (78.6‐87.7) | 96.0 (92.9‐98.0) | 353.3 (284.6‐438.5) | 7,221.3 (5,879.7‐8,869) | 20.4 (17.1‐24.5) | ||

| Yes | 11 | 36.4 (10.9‐69.2) | 54.5 (23.4‐83.3) | 60.7 (11.7‐314.8) | 183.0 (23.3‐1,436.8) | 3.0 (1.0‐9.4) | ||

| Anti‐CD38 antibodies | 1.000 | 0.002 | ||||||

| No | 270 | 82.2 (77.1‐86.6) | 94.1 (90.6‐96.6) | 345.6 (277.1‐431.1) | 6,434.2 (5,086.5‐8,139.0) | 18.6 (15.5‐22.4) | ||

| Yes | 14 | 71.4 (41.9‐91.6) | 100 (76.8‐100.0) | 135.1 (38.4‐475.7) | 3,725.3 (2,435.6‐5,697.8) | 27.6 (10.1‐75.6) | ||

| Patients treated with cellular therapy | 0.262 | 0.461 | ||||||

| No | 243 | 82.3 (76.9‐86.9) | 95.1 (91.5‐97.4) | 325.1 (258.2‐409.4) | 6,722.5 (5,342.4‐8,459.2) | 20.7 (17.1‐25.1) | ||

| Yes | 41 | 78.0 (62.4‐89.4) | 90.2 (76.9‐97.3) | 360.4 (183.4‐708.0) | 4,117.3 (1,908.0‐8,884.5) | 11.4 (6.6‐19.7) | ||

| Patients treated with cellular therapy type | ||||||||

| Allo‐HSCT any time prior to vaccination | 22 | 81.8 (59.7‐94.8) | 95.5 (77.2‐99.9) | 433.3 (177.7‐1,056.3) | 6,429.1 (2,493.0‐16,579.5) | 14.8 (6.8‐32.6) | ||

| Auto‐HSCT within the past 24 months | 13 | 92.3 (64.0‐99.8) | 100.0 (75.3‐100.0) | 522.5 (186.0‐1,467.9) | 8,438.8 (4,217.8‐16,884.0) | 16.2 (7.0‐37.1) | ||

| CD19 CAR‐T any time prior to vaccination | 5 | 20.0 (0.5‐71.6) | 40.0 (5.3‐85.3) | 53.2 (1.0‐2,964.9) | 75.4 (2.0‐2,817.2) | 1.4 (0.4‐5.6) | ||

| BCMA CAR‐T any time prior to vaccination | 1 | 100.0 (2.5‐100.0) | 100.0 (2.5‐100.0) | 712 d | 9,794.2 d | 13.8 | ||

| BTK inhibitors | 1.000 | 0.002 | ||||||

| No | 278 | 82.4 (77.4‐86.7) | 94.2 (90.8‐96.7) | 340.6 (273.5‐424.0) | 6,504.3 (5,185.9‐8,157.8) | 19.1 (15.9‐23.0) | ||

| Yes | 6 | 50.0 (11.8‐88.2) | 100.0 (54.1‐100.0) | 76.7 (9.4‐625.2) | 1,088.2 (293.2‐4,039.1) | 14.2 (3.1‐64.0) | ||

| Line of systemic therapy to date | 0.847 | 0.929 | ||||||

| 0 | 67 | 85.1 (74.3‐92.6) | 95.5 (87.5‐99.1) | 384.6 (246.7‐599.4) | 7,608.9 (5,083.5‐11,388.9) | 19.8 (13.8‐28.4) | ||

| 1 | 115 | 86.1 (78.4‐91.8) | 94.8 (89.0‐98.1) | 396.2 (289.0‐543.1) | 6,670.8 (4,783.2‐9,303.4) | 16.8 (13.1‐21.6) | ||

| ≥2 | 102 | 74.5 (64.9‐82.6) | 93.1 (86.4‐97.2) | 242.9 (162.6‐362.9) | 5,133.3 (3,331.8‐7,908.7) | 21.1 (14.8‐30.2) | ||

Abbreviations: BTK, Bruton's tyrosine kinase; allo‐HSCT, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; auto‐HSCT, autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; CAR‐T, chimeric antigen receptor T‐cell therapy; GMT, geometric mean titer; CI, confidence interval

Blood draws were conducted prior to and after vaccine dose three.

All lab assessments were within 3 months before dose three of the vaccine. 17.6% of total patients had missing lymphocyte count. Among patients with plasma cell disorder, 3.8% had missing IgG values, 3.8% had missing IgA values, and 3.8% had missing IgM values.

Anti‐androgen and anti‐estrogen hormonal therapies were not considered anticancer therapy for this study.

Small molecules include tyrosine kinase inhibitors, proteasome inhibitors, lenalidomide, pomalidomide, and venetoclax.

As this sub‐analysis group only included one patient, a confidence interval cannot be generated.

P‐values were calculated comparing patients on a specific therapy with patients not on the therapy on a specific study time point by Fisher exact test or Chi‐square test (antibody seropositivity 29 days after dose 3).

P‐values were calculated by comparing patients on a specific therapy with those not on the therapy on a specific study time point by the Kruskal‐Wallis test (GMTs 29 days after dose 3).

P‐values were calculated by comparing hematological malignancies with solid tumors

P‐values were calculated comparing myeloid, lymphoid, and plasma cell disorders.

FIGURE 1.

Comparison of antibody titers (ELISA) pre‐dose 3‐ and one‐month post‐dose 3 by cancer type and type of hematological malignancy.

Abbreviations: ELISA, enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay; HM, hematological malignancy.

GMTs post–dose three were significantly lower (P ≤ 0.002) among patients who had received anticancer therapy within three months as well as those treated with small molecules, anti‐CD20 antibodies, or anti‐CD38 antibodies within six months, and BTK inhibitors (Table 3). While no significant difference in response to vaccine dose three was noted between those who received cellular therapy and those who did not, it was notable that the 5 patients who had received CD19 CAR‐T any time prior to dose three had very low GMTs pre– and post‐dose three and showed only a 1.4‐fold increase in titer post–dose three. Among the 52 patients with plasma cell disorders, GMTs were positively correlated to IgG, IgM, and IgA levels.

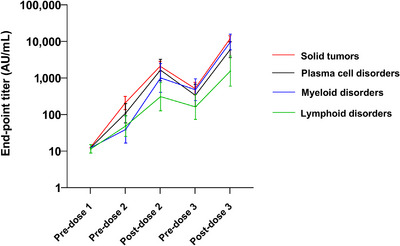

3.4. Serum antibody responses in selected cohorts

Among the cohort of 130 patients from the original primary vaccine trial who had sera data pre–dose one, post–dose one, post–dose two, pre–dose three, and post–dose three, the percentage of seropositive patients (Table 4) and the GMTs increased with administration of each additional vaccine dose (Table 5, Figure 2). Vaccine dose three significantly increased GMTs compared to pre‐dose three levels and led to significantly increased GMTs over what was achieved after two vaccine doses. Although GMTs dropped nearly 3‐fold in the ∼7 to 9 months between doses two and three, administration of dose three resulted in titers that were considerably higher 28 days after dose three compared to 28 days post–dose two (ranging from 3.7‐ to 9.6‐fold higher). Titers among lymphoid cancer patients, who had the lowest response to the vaccine, increased 4.7‐fold between post–dose two and post–dose three.

TABLE 4.

Percent SARS‐CoV‐2 antibody seropositive (95% CI) at each timepoint pre‐ and post‐doses 1, 2, and 3 of the mRNA‐1273vaccine by cancer patient category among patients in the subcohort (Cohort 1) (n = 130).

| Characteristics | Pre‐Dose 1 | Post‐Dose 1 | Post‐Dose 2 | Pre‐dose 3 | Post‐dose 3 | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 0.8 (0.0‐4.2) | 71.5 (63.0‐79.1) | 90.8 (84.4‐95.1) | 84.6 (77.2‐90.3) | 95.4 (90.2‐96.3) | 130 |

| Tumor type | ||||||

| Hematologic malignancies | 1.2 (0.0‐6.6) | 58.5 (47.1‐69.3) | 85.4 (75.8‐92.2) | 79.3 (68.9‐87.4) | 92.7 (84.8‐97.3) | 82 |

| Myeloid disorders | 0.0 | 36.8 (16.3‐61.6) | 100.0 (82.4‐100.0) | 94.7 (74.0‐99.9) | 100.0 (82.4‐100.0) | 19 |

| Lymphoid disorders | 2.9 (0.1‐14.9) | 57.1 (39.4‐73.7) | 68.6 (50.7‐83.1) | 65.7 (47.8‐80.9) | 82.9 (66.4‐93.4) | 35 |

| Plasma cell disorders | 0.0 | 75.0 (55.1‐89.3) | 96.4 (81.7‐99.9) | 85.7 (67.3‐96) | 100.0 (87.7‐100.0) | 28 |

| Solid tumor | 0.0 | 93.8 (82.8‐98.7) | 100.0 (92.6‐100.0) | 93.8 (82.8‐98.7) | 100.0 (92.6‐100.0) | 48 |

TABLE 5.

SARS‐CoV‐2 antibody geometric mean titers, AU/mL (95%CI) at each timepoint pre‐ and post‐doses 1, 2, and 3 of the mRNA‐1273 by cancer patient category among patients in the subcohort (Cohort 1) (n = 130).

| Vaccine dosing | Fold increase post‐dose 3 to post‐ dose 2 a (95% CI) | Fold increase post‐ dose 3 to pre‐dose 3 b (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Pre‐Dose 1 | Post‐Dose 1 | Post‐Dose 2 | Pre‐dose 3 | Post‐dose 3 | ||

| Overall | 13.0 (12.1‐13.9) | 102.5 (75.6‐139.0) | 1,129.4 (801.0‐1,592.5) | 364.2 (266.8‐497.2) | 5,962.0 (4,335.2‐8,199.2) | 5.3 (4.2‐6.7) | 16.4 (12.8‐21.0) |

| Tumor type | |||||||

| Hematologic malignancies | 13.2 (11.8‐14.8) | 68.0 (45.7‐101.2) | 784.8 (474.7‐1,297.4) | 297.1 (191.8‐460.3) | 4,007.4 (2,493.2‐6,441.3) | 5.1 (3.7‐7.1) | 13.5 (9.7‐18.7) |

| Myeloid disorders | 12.5 c | 39.1 (16.7‐91.9) | 1,009.3 (406.5‐2,506.1) | 479.3 (241.3‐952.0) | 9,682.5 (5,888.4‐15,921.3) | 9.6 (3.9‐23.4) | 20.2 (10.8‐37.7) |

| Lymphoid disorders | 14.3 (10.9‐18.8) | 62.9 (32.2‐122.8) | 376.7 (150.7‐941.9) | 206.5 (92.1‐463.2) | 1,786.1 (677.1‐4,711.6) | 4.7 (2.8‐8.1) | 8.6 (5.0‐14.9) |

| Plasma cell disorders | 12.5 c | 109.1 (59.3‐200.6) | 1,656.1 (842.1‐3,257.0) | 338.5 (168.4‐680.5) | 6,047.7 (3,661.5‐9,988.9) | 3.7 (2.5‐5.4) | 17.9 (10.5‐30.3) |

| Solid tumors | 12.5 c | 206.5 (136.1‐313.1) | 2,103.3 (1,547.8‐2,858.2) | 515.7 (349·4‐761.2) | 11,752.1 (9,632.6‐14,338.0) | 5.6 (4.2‐7.5) | 22.8 (15.7‐33.1) |

Abbreviations: GMT, geometric mean titer.

Fold rise in GMTs was calculated by comparing post‐dose 3 GMTst o post‐dose 2 GMTs.

Fold rise in GMTs was calculated by comparing post‐dose 3 GMTs to pre‐dose 3 GMTs.

The GMTs were below the level of detection and have been assigned a value of 12·5. The 95% CI cannot be calculated if they are the same values.

FIGURE 2.

Antibody titers over time among cancer patients in the subcohort evaluated after each vaccine dose (Cohort 1) (n = 130)

Fifty‐two patients were SARS‐CoV‐2 antibody seronegative prior to dose three; of them, 36 (69.2%) seroconverted after dose three, while 16 (30.8%) did not. Notably, patients’ median age, racial/ethnic background, disease status, IgG, IgA, and IgM levels, receipt of anticancer therapy (chemo‐, immune‐, and radiation therapy) within three months, small molecules, cellular therapy, anti‐CD38 antibodies within six months, BTK inhibitor, or line of systemic therapy to date were comparable between these two subgroups Supplementary Table S1). The differences reaching statistical significance between these 2 groups were that a higher proportion of non‐seroconverting patients had been treated with anti‐CD20 antibodies within the last six months (71.4%% and 24.4%, respectively), and a higher proportion of non‐seroconverting patients had hematologic malignancies than solid tumors (38.5% and 7.7%, respectively). The GMT of the 36 patients who seroconverted increased from 12.5 AU/mL prior to dose three to 1906.5 AU/mL after dose three, a ∼153‐fold increase. The GMTs were considerably higher among the pre‐dose three positive patients (n = 232), resulting in a strong but lower fold increase of 16.8 (687.3 and 11565.1 AU/mL, pre‐ and post‐dose three, respectively) compared to the pre‐dose three seronegative patients (data not shown)

Of the 16 patients who remained seronegative at day +28 after receipt of dose three, 15 had HM (1 myeloid disorder, 12 lymphoid disorders, and 2 plasma cell disorders), and 1 was a solid tumor patient (Supplementary Table S1). Ten were in remission, while 6 had relapsed, refractory, or stable disease. The total lymphocyte count was lower among those who did not seroconvert after dose three, with 12 of the patients having a count ≤1 × 109 mL within three months prior to dose three.

4. DISCUSSION

This is one of the largest studies to report on the administration of dose three of the mRNA‐1273 COVID‐19 vaccine to cancer patients. The data reported here suggest that receipt of vaccine dose three is particularly beneficial to cancer patients, especially those with hematologic malignancies, most notably lymphoid cancer. Four weeks after dose three of mRNA‐1273, most patients showed a robust response to the vaccine, with titers increasing 10.5‐ to 25.5‐fold depending on the type of cancer with which they were diagnosed.

Assessment of the antibody response after vaccine dose three by cancer type yielded several important additional observations. First, among the small subset of patients who had no detectable antibodies prior to dose three, nearly 70% seroconverted after vaccine dose three. Administration of dose three not only led to seroconversion among those with nondetectable antibody titers prior to dose three but also led to substantially higher titers than observed after the second vaccine dose. Second, patients with HM had lower antibody titers compared to those with solid tumors, aligning with other data suggesting that vaccine responses are often diminished in patients with HM as a result of B‐cell defects [13, 14]. Third, antibody responses after dose three were reduced in those with lower total lymphocyte counts (≤1 × 109 mL) as well as those who had received anticancer therapy within 3 months (specifically anti‐CD20, CD38, and BTK inhibitors). A similar blunting of antibody response was previously observed based on the type of therapy following the two‐dose primary series as well [2]. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, despite waning humoral immunity observed following the second vaccine dose, administration of vaccine three dose restored antibody titers to higher levels than were observed following the second vaccine dose, even among lymphoid cancer patients (who had the lowest and slowest humoral response after each vaccine dose), suggesting good immunologic memory. Several of these observations have also been corroborated by other recent studies, in which a majority of HM patients who were seronegative prior to dose 3 seroconverted following dose 3 and in which BTK inhibitors and anti‐CD20 treatments were associated with a blunted humoral response to dose three [7, 15].

Among lymphoid cancer patients, the frequent and standard usage of B‐cell–depleting therapies likely explains the dampened humoral response to the mRNA‐1273 vaccine. In addition, such therapies are administered chronically (e.g., BTK inhibitors) or have very long‐acting B‐cell depleting properties (e.g., anti‐CD20 antibodies), making it likely that a majority of patients with advanced lymphoid cancers will experience a less robust humoral response to COVID‐19–directed vaccines. Interestingly, T‐cell immune responses may occur in a minority of patients lacking a humoral response following the initial 2‐dose COVID‐19 vaccine series, yet the cellular response following vaccine dose three in such patients remains to be determined [16, 17].

This study is one of the largest to report on safety following COVID‐19 vaccine dose three in cancer patients. Dose three of mRNA‐1273 in this population of cancer patients was well tolerated. Adverse reactions, consisting primarily of injection site reactions, fever and fatigue, were similar to those reported after two vaccine doses in this same population [2] and were generally similar to the adverse event profile observed in healthy adults after the first and second doses and after a booster dose [18, 19, 20, 21]. Notably, the vast majority (90%) of treatment‐emergent adverse events occurred within 14 days (+5) of vaccine administration, whereas severe adverse events were extremely rare at either timepoint assessed, suggesting a low risk for significantly delayed toxicities. Our safety results also appear concordant with those observed in other small series of patients with cancer or immunocompromised states (e.g., post‐allogeneic transplantation) [22, 23]. However, the data suggest that longer‐term follow‐up following vaccine dose three will be necessary to fully annotate the toxicity in this population.

The use of a binding assay (enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA]) as opposed to a neutralization assay limited our ability to determine functional immunity derived from vaccine dose three. Recent evidence, however, suggests that neutralizing antibody response occurs among cancer patients following vaccine dose three, including in patients with undetectable neutralizing antibodies after 2 doses [15]. There were several other limitations of our study as well. First, we did not determine immunogenicity against different variants, including current circulating sub‐variants of Omicron. Second, because vaccine efficacy was not directly assessed in this study and no immune correlate of protection has been identified, we cannot infer protection following dose three based on the titers observed in this study. While a protective effect following a 2‐dose regimen in cancer patients has been observed [24], and a recent observational study also suggested a clinically protective effect following dose three in cancer patients [25], threshold levels of antibody titers associated with protection remain to be determined. Third, the number of patients in each category receiving specific therapies was lower for some analyses, thereby limiting our ability to draw firm conclusions about vaccine responses in certain patient subsets. Finally, the recommendation to administer vaccine dose three as part of the priming series for immunocompromised individuals as soon as 28 days after the second dose differs from the duration between doses in this study. As such, the immune responses observed in standard clinical practice may differ from those reported here. Important strengths of this research include the large sample size, diverse population of cancer patients with various underlying conditions and cancer therapy received, and the ability to follow a large cohort of 130 subjects through three successive vaccine doses.

The results of this study highlight the value of a three‐dose primary series for cancer patients, as currently recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) [26, 27]. Timely receipt of all three doses for patients with HM, especially those receiving immunosuppressive therapy and those with significantly waned or absent humoral immunity prior to dose three, is supported by our findings. The implications of failure to seroconvert following dose three are unclear, but it would seem reasonable to strongly consider such patients for passive immunization or other preventive approaches. With the arrival of variants of concern, including Omicron, the ACIP has further revised its recommendations to administer a fourth and fifth dose for immunocompromised patients. Further research is needed to determine the best timing for vaccine receipt among cancer patients in relation to their cancer therapy regimen, the appropriate interval between doses to obtain the optimal immune response, and the ultimate clinical efficacy of additional vaccine doses in cancer patients.

DECLARATIONS

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: Anna Giuliano, Jeffrey Lancet, Patrick Hwu, Brett Leav, Barbara Kuter; Methodology: Anna Giuliano, Jeffrey Lancet, Junmin Whiting, Qianxing Mo; Formal analysis: Junmin Whiting, Qianxing Mo, Christopher Cubitt; Investigation: Anna Giuliano, Jeffrey Lancet, Shari Pilon‐Thomas, Junmin Whiting, Christopher Cubitt, Christopher Dukes, Kimberly Isaacs‐Soriano, Kayoko Kennedy, Somedeb Ball, Ning Dong, Akriti Jain; Resources: Shari Pilon‐Thomas, Christopher Cubitt; Writing – Original Draft: Anna Guiliano, Jeffrey Lancet, Barbara Kuter; Writing – Review and Editing: Jeffrey Lancet, Anna Giuliano, Junmin Whiting, Quanxing Mo, Brett Leav, Bradley Sirak, Christopher Cubitt, Kimberly Isaacs‐Soriano, Kayoko Kennedy, Patrick Hwu; Visualization: Jeffrey Lancet, Anna Giuliano, Junmin Whiting, Christopher Cubitt, Kimberly Isaacs‐Soriano, Kayoko Kennedy; Supervision: Anna Giuliano, Jeffrey Lancet; Project administration: Anna Giuliano, Jeffrey Lancet, Bradley Sirak; Funding acquisition: Anna Giuliano.

ETHICS APPROVAL STATEMENT

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Advarra Institutional Review Board (IRB# 00000971). All the participants provided written informed consent before enrollment in this study. This study followed the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Brett Leav is an employee of Moderna and holds shares in Moderna; Barbara Kuter is a consultant of Moderna; Jeffrey Lancet and Anna Giuliano received research funding from Moderna. All other authors report no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING INFORMATION

Research funding was provided by Moderna.

PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT

All patients provided written informed consent prior to enrollment in the study.

Supporting information

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the many cancer patients at the Moffitt Cancer Center who participated in this study and the Tissue, Immune Monitoring, Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Core Services of the Moffitt Cancer Center. We would also like to thank the following individuals at the Moffitt Cancer Center who supported this study including Martha Abrahamsen, Kyle Hawkins, Julie Rathwell, Kayoko Kennedy, Adele Semaan, Sashanna Roman, Natasha Francis, Karla Ali, and Amanda Bloomer. We would also like to thank Julie Vanas, Deborah Manzo, Carly Crocker, and Maha Maglinao from Moderna for their support of the study. Editorial assistance was provided by the Moffitt Cancer Center's Office of Scientific Publishing by Daley White and Gerard Hebert; no compensation was given beyond their regular salaries. This work has been supported in part by the Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Shared Resource at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, an NCI‐designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30‐CA076292).

Giuliano A, Kuter B, Pilon‐Thomas S, Whiting J, Mo Q, Leav B, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a third dose of mRNA‐1273 vaccine among cancer patients. Cancer Commun. 2023;43:749–764. 10.1002/cac2.12453

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Chavez‐MacGregor M, Lei X, Zhao H, Scheet P, Giordano SH. Evaluation of COVID‐19 Mortality and Adverse Outcomes in US Patients With or Without Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8(1):69–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Giuliano AR, Lancet JE, Pilon‐Thomas S, Dong N, Jain AG, Tan E, et al. Evaluation of Antibody Response to SARS‐CoV‐2 mRNA‐1273 Vaccination in Patients With Cancer in Florida. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8(5):748–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Greenberger LM, Saltzman LA, Senefeld JW, Johnson PW, DeGennaro LJ, Nichols GL. Antibody response to SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines in patients with hematologic malignancies. Cancer Cell. 2021;39(8):1031–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Herishanu Y, Avivi I, Aharon A, Shefer G, Levi S, Bronstein Y, et al. Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID‐19 vaccine in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2021;137(23):3165–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Massarweh A, Eliakim‐Raz N, Stemmer A, Levy‐Barda A, Yust‐Katz S, Zer A, et al. Evaluation of Seropositivity Following BNT162b2 Messenger RNA Vaccination for SARS‐CoV‐2 in Patients Undergoing Treatment for Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(8):1133–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Monin L, Laing AG, Muñoz‐Ruiz M, McKenzie DR, Del Molino Del Barrio I, Alaguthurai T, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of one versus two doses of the COVID‐19 vaccine BNT162b2 for patients with cancer: interim analysis of a prospective observational study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(6):765–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shapiro LC, Thakkar A, Campbell ST, Forest SK, Pradhan K, Gonzalez‐Lugo JD, et al. Efficacy of booster doses in augmenting waning immune responses to COVID‐19 vaccine in patients with cancer. Cancer Cell. 2022;40(1):3–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Terpos E, Trougakos IP, Gavriatopoulou M, Papassotiriou I, Sklirou AD, Ntanasis‐Stathopoulos I, et al. Low neutralizing antibody responses against SARS‐CoV‐2 in older patients with myeloma after the first BNT162b2 vaccine dose. Blood. 2021;137(26):3674–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thakkar A, Gonzalez‐Lugo JD, Goradia N, Gali R, Shapiro LC, Pradhan K, et al. Seroconversion rates following COVID‐19 vaccination among patients with cancer. Cancer Cell. 2021;39(8):1081–90.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brockman MA, Mwimanzi F, Lapointe HR, Sang Y, Agafitei O, Cheung PK, et al. Reduced Magnitude and Durability of Humoral Immune Responses to COVID‐19 mRNA Vaccines Among Older Adults. J Infect Dis. 2022;225(7):1129–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tartof SY, Slezak JM, Fischer H, Hong V, Ackerson BK, Ranasinghe ON, et al. Effectiveness of mRNA BNT162b2 COVID‐19 vaccine up to 6 months in a large integrated health system in the USA: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2021;398(10309):1407–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ligumsky H, Dor H, Etan T, Golomb I, Nikolaevski‐Berlin A, Greenberg I, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine booster in actively treated patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(2):193–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Agha ME, Blake M, Chilleo C, Wells A, Haidar G. Suboptimal Response to Coronavirus Disease 2019 Messenger RNA Vaccines in Patients With Hematologic Malignancies: A Need for Vigilance in the Postmasking Era. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8(7):ofab353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pleyer C, Ali MA, Cohen JI, Tian X, Soto S, Ahn IE, et al. Effect of Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor on efficacy of adjuvanted recombinant hepatitis B and zoster vaccines. Blood. 2021;137(2):185–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fendler A, Shepherd STC, Au L, Wilkinson KA, Wu M, Schmitt AM, et al. Immune responses following third COVID‐19 vaccination are reduced in patients with hematological malignancies compared to patients with solid cancer. Cancer Cell. 2022;40(2):114–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ehmsen S, Asmussen A, Jeppesen SS, Nilsson AC, Østerlev S, Vestergaard H, et al. Antibody and T cell immune responses following mRNA COVID‐19 vaccination in patients with cancer. Cancer Cell. 2021;39(8):1034–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mellinghoff SC, Robrecht S, Mayer L, Weskamm LM, Dahlke C, Gruell H, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 specific cellular response following COVID‐19 vaccination in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2022;36(2):562–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Atmar RL, Lyke KE, Deming ME, Jackson LA, Branche AR, El Sahly HM, et al. Homologous and Heterologous Covid‐19 Booster Vaccinations. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(11):1046–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, Kotloff K, Frey S, Novak R, et al. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA‐1273 SARS‐CoV‐2 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(5):403–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chalkias S, Schwartz H, Nestorova B, Feng J, Chang Y, Zhou H, et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of a 100 μg mRNA‐1273 Vaccine Booster for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus‐2 (SARS‐CoV‐2). medRxiv. 2022.

- 21. Moreira ED Jr, Kitchin N, Xu X, Dychter SS, Lockhart S, Gurtman A, et al. Safety and Efficacy of a Third Dose of BNT162b2 Covid‐19 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(20):1910–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kimura M, Ferreira VH, Kothari S, Pasic I, Mattsson JI, Kulasingam V, et al. Safety and Immunogenicity After a Three‐Dose SARS‐CoV‐2 Vaccine Schedule in Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplant Recipients. Transplant Cell Ther. 2022;28(10):706.e1‐.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lasagna A, Bergami F, Lilleri D, Percivalle E, Quaccini M, Alessio N, et al. Immunogenicity and safety after the third dose of BNT162b2 anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine in patients with solid tumors on active treatment: a prospective cohort study. ESMO Open. 2022;7(2):100458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wu JT, La J, Branch‐Elliman W, Huhmann LB, Han SS, Parmigiani G, et al. Association of COVID‐19 Vaccination With SARS‐CoV‐2 Infection in Patients With Cancer: A US Nationwide Veterans Affairs Study. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8(2):281–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lee LYW, Ionescu MC, Starkey T, Little M, Tilby M, Tripathy AR, et al. COVID‐19: Third dose booster vaccine effectiveness against breakthrough coronavirus infection, hospitalisations and death in patients with cancer: A population‐based study. Eur J Cancer. 2022;175:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Center for Disease Control and Prevention . COVID‐19 Vaccines for People who are Moderately or Severely Immunocompromised: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2022. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019‐ncov/vaccines/recommendations/immuno.html?s_cid=11710:immunocompromised%20covid%20booster%20dose:sem.ga:p:RG:GM:gen:PTN.Grants:FY22 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stay Up to Date with Your COVID‐19 Vaccines : Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2022. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019‐ncov/vaccines/stay‐up‐to‐date.html [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.