Abstract

The sensitivity of systems biology models to parameter variation can give insights into which parameters are most important for physiological function, and also direct efforts to estimate parameters. However, in general, kinetic models of biochemical systems do not remain thermodynamically consistent after perturbing parameters. To address this issue, we analyse the sensitivity of biological reaction networks in the context of a bond graph representation. We find that the parameter sensitivities can themselves be represented as bond graph components, mirroring potential mechanisms for controlling biochemistry. In particular, a sensitivity system is derived which re-expresses parameter variation as additional system inputs. The sensitivity system is then linearized with respect to these new inputs to derive a linear system which can be used to give local sensitivity to parameters in terms of linear system properties such as gain and time constant. This linear system can also be used to find so-called sloppy parameters in biological models. We verify our approach using a model of the Pentose Phosphate Pathway, confirming the reactions and metabolites most essential to maintaining the function of the pathway.

Keywords: systems biology, bond graph, sensitivity, energy-based modelling

1. Introduction

The sensitivity of a system is a quantitative measure of how much system outputs change in response to changes in parameters or inputs; a system that is insensitive is said to be robust with respect to those parameters, which are then refered to as sloppy. On the other hand, parameters associated with high sensitivity are often important for the function of a biological system, for example defining switch-like behaviours [1]. Sensitivity theory of dynamical systems and its application to engineering systems is well established and summarized in the textbooks [2,3]. There are many applications of sensitivity methods to systems and control problems including: system optimization, control system analysis [4,5] controller tuning [6] and parameter estimation [7,8].

The importance of sensitivity to the discipline of systems biology has long been recognized [9–12] and continues to be investigated [13–15]. In particular, metabolic control analysis (MCA) [16–20] applies sensitivity methods to the analysis of chemical reaction networks in general and metabolism in particular. A thorough investigation into the links between MCA and more general sensitivity theory can be found in the works of Ingalls [21–24].

Because of the overlap between engineering and systems biology, it is insightful to import methods from the former to the latter [25–27]. The bond graph technique provides one example of this methodological transfer, and has shown great potential in constraining models to be consistent with the laws of physics and thermodynamics [28,29]. Bond graphs were introduced by Paynter [30,31] to model the flow of energy though physical systems of interest to engineers and are described in several textbooks [32–35] and a tutorial for control engineers [36]. Bond graphs provide a systematic approach to elucidating the analogies between disparate physical domains based on energy and thus can also provide a foundation for systems biology. In particular, bond graphs were first used to model chemical reaction networks by Katchalsky and co-workers [37]. A detailed account is given by Oster et al. [38] and an overview of the approach is given by Perelson [39]. This work has been extended to systems biology [40–46]. A recent introduction and overview of the bond graph approach to systems biology is given by Gawthrop & Pan [28].

Sensitivity analysis is often based on analysing the ODE derived from a system rather than the system itself [12,15]. By contrast, this paper analyses the system itself by extending the bond graph approach to sensitivity analysis, that has previously been developed for engineering systems [47–50], to biochemical systems. This approach has the advantage that the sensitivity is with respect to physically meaningful parameters and both unperturbed and perturbed systems obey basic physical laws such as mass and energy conservation.

A key insight in sensitivity analysis is that the sensitivity properties of a system may be described by a related system: the sensitivity system [2,48,49,51]. This notion has been extended in the context of bond graph models of engineering systems to the idea that a system represented by a bond graph has a sensitivity system also described by a bond graph [48,49]. As will be shown, this property is inherited by biochemical systems.

Employing this sensitivity system in place of analysing the sensitivity of the underlying ODE has a number of advantages including: the variability is encapsulated by additional inputs rather than variable parameters; as the sensitivity system is itself a bond graph, the full range of bond graph tools can be applied including linearization [41] and modular modelling [41,44,45].

There are two main categories of sensitivity analysis: local and global [12]. The former corresponds to small parameter variations and leads to linear dynamic systems; the latter corresponds to arbitrary parameter variations [12,15] and thus corresponds to nonlinear dynamic systems. In the context of this paper, the bond graph sensitivity system represents the nonlinear system and thus can be used for global analysis. As will be shown, this system can then be linearized and used for local sensitivity analysis. We focus on local sensitivity in this paper. Although the local approach is approximate, it is more computationally efficient than global methods and offers more insight into the effects of varying combinations of parameters. Indeed, the properties of the linearized system can be summarized by basic linear system properties such as gain and time constant; these can be derived without simulation. The variation of the local model properties with the point of linearization can also give insight into system properties. The local approach can also be for initial investigations followed by targeted global analysis [52].

As mentioned above, parameter variation appears in the sensitivity system as additional inputs. Hence local sensitivity analysis, which linearizes with respect to parameter variation, is closely related to linearization with respect to inputs; this paper explicitly shows this relationship. Such linearization has already been examined in the bond graph systems biology context [41,53]. This paper looks at the approximation inherent in local analysis by comparing global with local results for a range of examples.

Sensitivity analysis can either be static and show how steady-state values of species depend on parameters, as in MCA, or be dynamic and show how the time trajectories of species depend on parameters. This paper looks at dynamic sensitivity analysis; this enables not only static values of sensitivity to be derived but also the sensitivity of the time course of species as parameters change. These sensitivity trajectories can be represented as a transfer function, the properties of which can be summarized in various ways according to the application. For example, the trajectory transfer function can be summarized by steady-state gain (also know as DC gain), initial response and time constant or, in the context of control theory, by a frequency response.

This paper extends bond graph-based sensitivity analysis to biochemical systems. In particular, the bond graph of the sensitivity system of a biochemical system is derived; following [48], this involves ascertaining the sensitivity component associated with biochemical bond graph components. Biochemical bond graph components are different from those found in engineering systems and thus require the new methods derived in this paper. Biochemical systems form a subset of nonlinear systems with special properties; in particular, the mass-action equations result from the logarithmic nature of chemical potential [40,54] and the exponential nature of the Marcelin–de Donder formulation of reaction flows [40,55]. Moreover, the reaction components have two energy ports as compared with the single port of typical engineering resistive components. As will be shown, this leads to the reformulation of parametric variation in terms of modulating chemical potentials which act as additional system inputs.

Bond graph models of mass-action equations can be combined in a modular fashion to represent more complex reaction formulations such as enzyme catalysed reactions [28,40,41]; thus sensitivity of these more complex reaction formulations is within the scope of this paper.

It is well known that system dynamics can be insensitive to variation of parameters: this behaviour has been called sloppy parameter sensitivities [56]. In particular, a quadratic cost function involving system trajectories has been formulated [56] to investigate this behaviour. This paper draws explicit links with the sloppy parameter analysis of Gutenkunst et al. [56].

Section 2 gives the background in bond graph modelling required for the rest of the paper and introduces a set of normalized variables. Section 3 introduces the bond graph sensitivity system appropriate to biochemical systems. Section 4 shows how the nonlinear sensitivity system can be linearized. Section 5 explores the relationship between the sensitivity system and the concept of sloppy parameter sensitivities. Sections 6 and 7 look at two illustrative examples: a modulated enzyme-catalysed reaction and the Pentose Phosphate Pathway.

The Python code used to generate the figures in this paper is available as Jupyter notebooks at https://github.com/gawthrop/Sensitivity23. Software tools for manipulating biochemical bond graphs are available in Python [57] at https://pypi.org/project/BondGraphTools/ and in Julia [58] at https://github.com/jedforrest/BondGraphs.jl. Both sets of tools are designed for modularity and scaleability and can generate both symbolic ODEs and numerical ODEs for simulation. The Python Control Systems Library, used for manipulating linearized systems, is available at https://pypi.org/project/control/.

2. Bond graph modelling of biochemical systems

This section summarizes the material needed for the rest of the paper. Section 2.1 summarizes, in the form of a specific example, the basic ideas of modelling biochemical systems to be found in more detail in a recent paper [28]. Section 2.2 introduces a normalization approach to simplify the sensitivity analysis and §2.3 considers the stoichiometry of bond graph models [28]. Section 2.4 summarizes the linearization of biochemical systems [41].

2.1. Example: modelling the chemical reactions

This example considers the two chemical reactions where the substance A is inter-converted with substance C via the intermediate substance B. Figure 1 gives the corresponding bond graph which consists of: the components Ce and Re which represent species and reactions, respectively, the bonds which carry energy in the form of chemical potential μ (J mol−1) and molar flow v (mol s−1) whose product μ × v has units of power (J s−1 or W) and the 0 junction which connects bonds in such a way that all impinging bonds carry the same potential. Thus, for example and vA = −v1; similarly and vB = v1 − v2. Although not used in figure 1, the dual 1 junction connects bonds in such a way that all impinging bonds carry the same flow. Ce components store, but do not dissipate, energy; Re components dissipate, but do not store, energy; bonds and junctions transmit energy without storage or dissipation.

Figure 1.

Example . The three species A, B and C are represented by the three bond graph components Ce:A, Ce:B and Ce:C and the two reactions r1 and r2 by the two bond graph components Re:r1 and Re:r2. The bonds carry the chemical potential μ, or affinities comprising sums of potentials, and molar flow v, and thus energy flows, between components. The 0 junctions combine energy flows in such a way the all impinging bonds carry the same potential.

The Ce:A component has the constitutive equations

| 2.1 |

| 2.2 |

where the time derivative in (2.2) means that this component is dynamic. R = 8.314 J mol−1 K−1 is the universal gas constant and T (K) the absolute temperature. μA (J mol−1) is the chemical potential of substance A, xA (mol) the amount of substance A and vA (mol s−1) the molar flow of substance A. As discussed by Gawthrop & Pan [28, §3.2], KA (mol−1) is given by

| 2.3 |

where is the chemical potential of substance A when . By contrast, the Re:r1 component is static with constitutive equation

| 2.4 |

where (J mol−1) and (J mol−1) are the forward and reverse affinities associated with reaction and v1 (mol s−1) is the molar flow associated with reaction . Analogous equations apply to the Ce components B and C, and the Re component .

In this simple example, these equations yield the well-known law of mass action

| 2.5 |

and

| 2.6 |

More complex biochemical systems are needed to reveal the full power of the bond graph approach. For example, detailed balance and Wegscheider conditions are automatically satisfied [28,59].

As discussed previously [28,41], an open system can be obtained from a closed system by replacing dynamic Ce components by chemostats [60] where the ODE (2.2) is replaced by

| 2.7 |

This example is continued throughout the paper as an open system with both Ce:A and Ce:C chemostats. This corresponds to the situation where substrate A and product C are kept at constant amounts.

2.2. Normalization

It is convenient to re-express chemical potential in non-dimensional form 1 where

| 2.8 |

For this section, we derive numerical values assuming that . To re-express molar flow in non-dimensional form , define a normalizing power . Choosing gives

| 2.9 |

| 2.10 |

The amount x can be re-expressed as the normalized variable

| 2.11 |

| 2.12 |

where is a normalizing time unit and v0 is given by (2.10). We can also define the normalized time as . Thus, the derivative dx/dt of the amount x can be re-expressed as the normalized variable

| 2.13 |

Using normalized variables, the Ce constitutive relation (2.1) becomes

| 2.14 |

| 2.15 |

and the Re constitutive relation (2.4) becomes

| 2.16 |

| 2.17 |

| 2.18 |

An alternative set of units uses the Faraday constant to replace chemical potential by and molar flow by [28,61]. In this case, the normalized variables can be re-expressed as

| 2.19 |

| 2.20 |

| 2.21 |

| 2.22 |

| 2.23 |

where is the amount expressed in coulombs.

2.3. Stoichiometry

As discussed previously [28,40,45] the stoichiometric representation of a biochemical system can be derived directly from the bond graph. In normalized form, the stoichiometric representation is

| 2.24 |

| 2.25 |

| 2.26 |

| 2.27 |

| 2.28 |

In the context of the example of §2.1

| 2.29 |

where

| 2.30 |

As discussed in §2.1, an open system can be obtained from a closed system by replacing dynamic Ce components by chemostats. In stoichiometric terms, equation (2.24) is replaced by

| 2.31 |

where the chemodynamic stoichiometric matrix Nc is identical to the stoichiometric matrix N except that rows corresponding to chemostats are set to zero [28,41].

In the context of the example of §2.1, choosing both Ce:A and Ce:C to be chemostats gives

| 2.32 |

2.4. Linearization

Linearization in the context of bond graph models of engineering systems is discussed by Karnopp [62], who showed that the linearized system could also be represented as a bond graph. Linearization in the context of bond graph models of biochemical systems is presented by Gawthrop & Crampin [41]. A key feature of biochemical systems is the presence of conserved moieties, which lead to constraints on system states [40, §3(b)], which in turn lead to reduced-order dynamical equations [40, §3(c)]. If such state constraints are not explicitly accounted for, linearization leads to systems with uncontrollable or unobservable states [63,64], which appear as cancelling pole/zero pairs in the corresponding transfer functions. This paper uses the approach of Gawthrop & Crampin [41, §4.2] to avoid this issue.

In particular, the linearized system is given in standard state-space form as

| 2.33 |

| 2.34 |

| 2.35 |

| 2.36 |

| 2.37 |

where , and are the deviation of the state x, the output y and the input u from the steady-state values , and , and a, b, c and d are matrices. The number of states, inputs and outputs are denoted nx, nu and ny, respectively.

This linear system has the corresponding ny × nu transfer function matrix G(s) relating the nu inputs to the ny outputs given in terms of the Laplace variable s as

| 2.38 |

where I is the nx × nx unit matrix.

In engineering system analysis [5], it is standard practice to characterize the time (t) response of a linear system in terms of the system unit step response. Because there are ny outputs and nu inputs, the unit step response gij(t) of the ith output with respect to the jth input is defined as the time response of the i output when the initial state and each input is the unit step function U(t), where

| 2.39 |

These individual step responses can be combined into the ny × nu matrix g(t) where the ijth element is gij(t). In particular, if the vector of nu inputs , where the jth element of the vector U0 is the amplitude of the jth step input, then

| 2.40 |

Moreover, the transfer function G(s) is the Laplace transform of the impulse response g′(t) = dg/dt and thus the Laplace transform of the step response g(t) is G(s)/s. It follows from the final and initial value theorems of the Laplace transform [5] that the time and Laplace domains are linked by

| 2.41 |

and

| 2.42 |

Equation (2.41) gives a convenient method for computing steady-state values from the transfer function and equation (2.42) gives a convenient method for computing the initial response of the linearized system.

Although the actual sensitivity system response may be complicated, it is useful to provide an indicator τ of the overall time scale. In the case where g0 ≠ 0, the response is instantaneous and hence τ = 0. When g0 = 0, a first-order transfer function is of the form

| 2.43 |

where τ0 is the system time constant. In this case, it is convenient to use τ = τ0. In the general case, there are many possible time constants to choose. Here, we use balanced order reduction [65] to reduce the system order to unity and select the corresponding time constant as in the first-order case.

The three numbers g0, g∞ and τ provide a convenient summary of the dynamic properties of the linearized system (2.33) and (2.34). In the control literature, g∞ is called the DC gain or steady-state gain of the linearized system (2.33) and (2.34).

3. The sensitivity system

This section shows how the bond graph corresponding to the sensitivity system can be derived from the bond graph of the biochemical system itself. There are two approaches considered. Section 3.1 shows how system components with variable parameters can be replaced by a sensitivity component represented itself by a bond graph thus giving an explicit bond graph for the sensitivity system. An alternative explored in §3.2 is to derive the stoichiometric matrix of the bond graph biochemical system model, augment this matrix to give the stoichiometric matrix of the sensitivity system and then construct the corresponding bond graph. These conversions from stoichiometric matrix to bond graph and from bond graph to stoichiometric matrix are based on earlier work [45].

3.1. The sensitivity bond graph

The key idea in this paper is to replace each parametric perturbation by an equivalent chemostat (§2.1) and thus each bond graph component by a corresponding sensitivity bond graph component. This leads to

-

1.

a (nonlinear) sensitivity system represented by a bond graph for any biochemical system represented by a bond graph;

-

2.

a (linear) local sensitivity system via linearization [41] of the sensitivity system; and

-

3.

a stoichiometric interpretation of the sensitivity system.

3.1.1. The Ce sensitivity component

The constitutive relation (2.14) of the normalized Ce component has a single parameter . For a given substance, is dependent on temperature.

The perturbation in this parameter is modelled using the multiplicative variable λ so that the constitutive relation (2.14) is replaced by

| 3.1 |

Thus the effect of λ can be thought of as adding a second chemostat Ce component in such a way that the normalized potential adds to the normalized potential of the original component to give

| 3.2 |

| 3.3 |

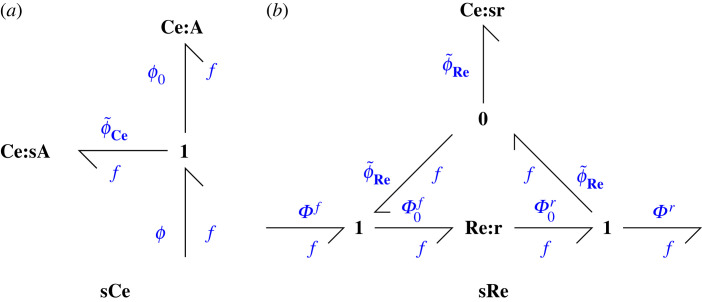

Figure 2a gives the bond graph interpretation.

Figure 2.

Sensitivity components (a) sCe, the sensitivity Ce component, comprises the original Ce component Ce:A with normalized potential and an additional chemostat Ce:sA with normalized potential connected by a 1 junction so that the overall normalized potential is . (b) sRe, the sensitivity Re component, comprises the original Re component Re:r with normalized forward and reverse potentials and and an additional chemostat Ce:sr with normalized potential connected by 1 junctions so that the overall normalized forward and reverse potentials are and .

3.1.2. The chemostat sensitivity component

In bond graph terms, chemostats are Ce components with a fixed state . As discussed in §2.1, they represent substances such as metabolites which are external to the system. In biochemical terms, can vary if the amount of the external substance changes. In this case, the fixed state x0 can also be perturbed using the multiplicative parameter λ

| 3.4 |

Comparing equation (3.4) with equation (3.1), it follows that a perturbation in the chemostat state x0 can be modelled in the same way as a perturbation in .

3.1.3. The Re sensitivity component

The constitutive relation (2.16) of the normalized Re component has a single parameter . In biochemical terms, can vary due to the amount of enzyme and the effect of enzyme inhibitors. The perturbation in the parameter is modelled using the multiplicative variable λ so that the constitutive relation (2.16) is replaced by

| 3.5 |

| 3.6 |

Thus the effect of λ can be thought of as adding a chemostat Ce component in such a way that the normalized potential adds to the normalized forward and reverse reaction potentials and to give the normalized forward and reverse reaction potentials and at the original component to give

| 3.7 |

| 3.8 |

| 3.9 |

Figure 2b gives the bond graph interpretation.

Thus, for both the Ce and Re components, the perturbation λ is modelled as an additional chemostat with normalized potential .

3.1.4. Example

The sensitivity system of figure 3 gives the normalized flows and through the reaction components Re:r1 and Re:r2 as

| 3.10 |

and

| 3.11 |

Note that if each λ = 1, the two flows correspond to the nominal system. The steady-state flows correspond to ; that is and thus

| 3.12 |

The steady-state value of is then given by

| 3.13 |

Again, the nominal steady state is obtained by setting each λ = 1.

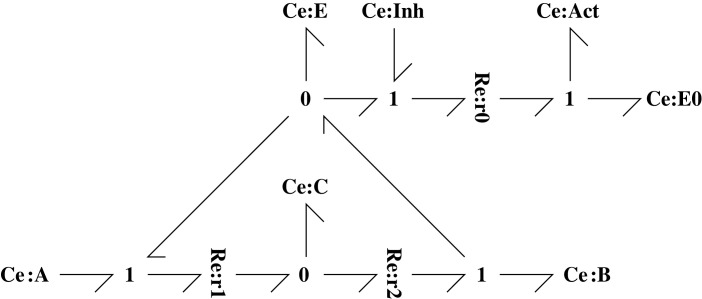

Figure 3.

Sensitivity example . This figure is similar to figure 1 except that the Ce and Re components have been replaced by the sCe and sRe components of figure 2. Thus the additional Ce and Re components of figure 2 are implicitly included within each sensitivity component. As discussed in §2.1, the system is open and Ce:A and Ce:C are chemostats; the corresponding sensitivity components are modelled in §3.1.2.

3.2. A stoichiometric interpretation

The bond graph interpretation of the sensitivity system given in §3.1 is conceptually useful and also provides a method for computer generation of the sensitivity system equations. This section presents an alternative approach to generating the sensitivity system equations from the bond graph using the stoichiometric representation outlined in §2.3. For simplicity, the equations are generated for the sensitivity of every component.

The stoichiometry of the bond graph was considered in §2.3. As discussed in §3.1, the sensitivity bond graph consists of the original bond graph with extra Ce components acting as chemostats connected to the original Ce and Re components as indicated in figure 2. These connections, together with those of the original bond graph, define the stoichiometry of the sensitivity bond graph. Following §2.3, the equations for the closed sensitivity system where all chemostats are regarded as ordinary Ce components is considered first. Assuming that a sensitivity component is appended for every Ce component and every Re component, the sensitivity system state can be written as

| 3.14 |

where is the original system state, and and are the states of the additional sensitivity Ce components associated with each Ce and Re component, respectively.

Noting from figure 2a that the sensitivity components associated with the Ce components share the same flows as the Ce components themselves, it follows from equation (2.31) that, in the case of a closed system

| 3.15 |

Further, noting from figure 2b that the sensitivity components associated with the Ce components share the same forward () and reverse () flows as the Re components themselves, it follows that

| 3.16 |

From §2.3, it follows that the stoichiometry of the sensitivity system corresponding to the open system with and as chemostats is given in terms of the stoichiometry (equations (2.31)–(2.26)) by

| 3.17 |

and

| 3.18 |

| 3.19 |

| 3.20 |

.

4. Linearization of the sensitivity system

Section 3 showed how the bond graph of the sensitivity system can be derived from the bond graph of the system itself; in general, this sensitivity system is nonlinear. A feature of the sensitivity system is that each parameter variation is replaced by a chemostat representing a system input. As discussed in §2.4, nonlinear biochemical systems can be linearized. In the case of the nonlinear sensitivity system of §3, the inputs are the parameter variables λ (represented by chemostats) and system flows were chosen to be the outputs. Hence the sensitivity system can be linearized about a steady state to give a linear system of the form

| 4.1 |

and

| 4.2 |

where the column vector contains all of the sensitivity deviation variables . Comparison with equations (2.33) and (2.34) shows that has the same role as the system input, and the same role as the system output, in the linearized system.

As discussed in §2.4, the three numbers g0, g∞ and τ provide a convenient summary of the dynamic properties of the linearized sensitivity system (4.1)–(4.2). In particular, g∞ is the DC gain or steady-state gain of the linearized sensitivity system (4.1) and (4.2) and g0 and τ represent the initial response and timescale, respectively.

Using the result of Karnopp [62] noted in §2.4, it follows that the linearized sensitivity system also has a bond graph representation but with linear components.

4.1. Example

As an illustrative example, this section continues the example of §2.1 for the particular set of parameters

| 4.3 |

and

| 4.4 |

Using the explicit calculations of appendix A, the dynamic linearization of §2.4 gives the transfer function

| 4.5 |

| 4.6 |

| 4.7 |

where and are the Laplace transforms of the flows and the incremental sensitivity parameters and G(s) is the transfer function. In this case,

| 4.8 |

Using equation (2.41) of §2.4, the steady-state gains relating the two flows to the five parameters are

| 4.9 |

| 4.10 |

Using equation (2.42) of §2.4, the initial response is

| 4.11 |

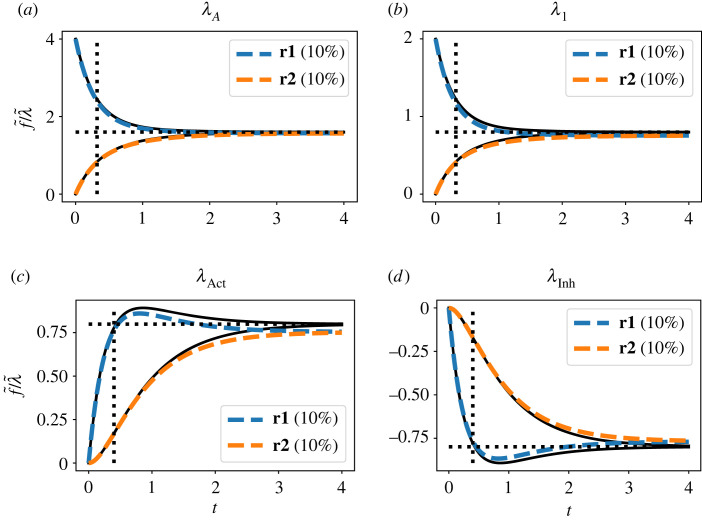

The five panels in figure 4a–e correspond to the five columns of g(t). To emphasize that the linearized response is a linear function of the perturbation amplitude, the figures show the perturbation step response normalized by the perturbation step amplitude . In each case, the normalized response of the flow through Re:r1 and Re:r2 to a 10% step change in the corresponding parameter is shown as dashed lines and compared to the unit step response of the corresponding transfer function element of G(s) together with the steady-stage gain g∞. The initial and final values correspond to the elements of the matrices (4.11) and (4.10), respectively, as indexed by (4.6) and (4.7).

Figure 4.

Illustrative example: the linearization approximation. The normalized (with respect to perturbation —see text) temporal responses of the flows through Re:r1 and Re:r2 to perturbations in (a) ; (b) ; (c) ; (d) ; (e) represented by the corresponding perturbation parameters λA, λB, λC, λ1 and λ2, respectively, as in equations (4.5)–(4.7). Parameters are perturbed using a 10% step change in the perturbation parameter λ. The black line is the normalized response of the linearized sensitivity system to the step change in the perturbation parameter λ (i.e. the unit step response), the horizontal dashed black line the corresponding DC gain g∞ and the vertical dashed black line the corresponding time-constant τ. The coloured dashed lines show the response of the simulated (nonlinear) sensitivity system to the same perturbation in λ. (f) As (d) but the flow through Re:r2 is shown for a ±10% and ±99% step change in the perturbation parameter λ1. In each case, the response of the linearized sensitivity system is an approximation to the response of the (nonlinear) sensitivity system itself.

The nonlinear response is close to that of the linearized response in each case. Figure 4f indicates how the discrepancy changes with parameter variations of ±10% and ±99%.

5. Sloppy parameter sensitivities

In their seminal paper, Gutenkunst et al. [56] introduced the concept of sloppy parameter sensitivities in the context of fitting parameters to experimental data. Following standard system identification practice [8], their method is based on a quadratic cost function of the variation of the system time response as parameters vary. This gives rise to a data-dependent Hessian matrix; the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of this matrix determine parameter sensitivity.

This section looks at how this concept applies in the context of the linear time responses of the linearized sensitivity model of §4. As discussed in §2.4, the linearized sensitivity system of §4 can be summarized in terms of the two parameters: steady-state gain g∞ and time constant τ; these two parameters can be deduced from the model itself without requiring simulation. By contrast, the sloppy parameter approach [56] is data based. Therefore, the relationship between the two approaches to characterizing model sensitivity to parameter variation is via the simulation of a model to generate data, even though such simulation is not required to generate g∞ and τ. As an illustrative example, the sensitivity of internal flows through reactions and external flows associated with chemostats are considered here. In particular, define the quadratic function Q of normalized system flow variation

| 5.1 |

Using equation (4.5), it follows that the cost function Q may be rewritten explicitly in terms of the parameter variation vector as

| 5.2 |

| 5.3 |

The matrix H is positive semi-definite and therefore has the eigenvalue decomposition

| 5.4 |

where σi ≥ 0 is the ith eigenvalue and the column eigenvectors Vi are orthogonal and have unit length. Without loss of generality, assume that the eigenvectors are sorted with the largest first and the smallest last. The basic idea of sloppy parameter sensitivities [56] is that small eigenvalues σi correspond to directions (indicated by Vi) in parameter space where the effect of parameter variations is small—these parameter combinations are termed sloppy. Conversely, large eigenvalues σi correspond to directions where the effect of parameter variations is large—these parameter combinations are termed stiff.

In the special case that the final time tf is large, H can be approximated in terms of the steady-state time response g∞

| 5.5 |

In the special case of a single output, g∞ is a vector and H∞ has rank 1 and the matrix H∞ has the decomposition

| 5.6 |

| 5.7 |

| 5.8 |

thus eigenvalues are zero. The corresponding cost function is defined as

| 5.9 |

5.1. The two-parameter case

Because Q is a quadratic function of the sensitivity parameter vector each constant value of Q corresponds to an ellipsoid in -dimensional space. In particular, in two-dimensional parameter space, this eigen-decomposition gives elliptical contours of Q = 1 with minor axis corresponding to and major axis corresponding to where σ1 ≥ σ2—see figure 1A of Gutenkunst et al. [56]. In the particular case of equation (5.6), σ2 = 0 the major axis has infinite length and the ellipse degenerates to two parallel lines. This two-parameter case is illustrated in figure 5 for both Q = 1 and Q∞ = 1.

Figure 5.

Sloppy parameters. As discussed in §5.1, the contours of the two-parameter cost function corresponding to constant values Q = 1 are ellipses in parameter space whereas Q∞ = 1 corresponds to two parallel lines. (a) The parameters λr1 and λr2, corresponding to the two Re components, are varied. (b) As (a) but with a long timescale; as expected, Q ≈ Q∞. (c) The parameters λA and λC, corresponding to the two chemostat Ce components, are varied. (d) As (c) but with a long timescale.

5.2. Example

Here, we consider the steady-state sensitivity of the biochemical pathway . For simplicity, consider the particular case where only the two sensitivity parameters λ1 and λ2 (corresponding to Re:r1 and Re:r2) are varied and the flow through Re:r1 is measured. The case where only the two sensitivity parameters λA and λC (corresponding to Ce:A and Ce:B) are varied can be analysed in a similar fashion.

The eigenvalue σ1 and eigenvector V1 corresponding to H∞ are given by

| 5.10 |

When tf = 1, the two eigenvalues and eigenvectors of H are given by

| 5.11 |

and

| 5.12 |

The ellipse corresponding to Q = 1 (5.2) appears in figure 5a together with the two parallel lines corresponding to Q∞ = 1 (5.9).

When tf = 1000, the two eigenvalues and eigenvectors of H are given by

| 5.13 |

and

| 5.14 |

In this case, the first eigenvalue and eigenvector of H are close to that of H∞; and the second eigenvector σ2 ≈ 0. Thus, in this case, H ≈ H∞. The ellipse corresponding to Q (5.2) appears in figure 5a together with the two parallel lines corresponding to Q∞ (5.9).

6. Example: modulated enzyme-catalysed reaction

Enzyme-catalysed reactions are an important control mechanism in biochemical systems [66]. One such mechanism is an enzyme-catalysed reaction with competitive activation and inhibition; which has been analysed within the bond graph context [53] and is shown in figure 6. This simple system is used to illustrate the sensitivity methods of this paper. In particular, the dynamic sensitivities are derived and compared with the steady-state gain g∞ and time constant τ characterization of the linear response. In addition, the variation of steady-state gain g∞ with steady-state flows through Re:r1 and Re:r2 is investigated.

Figure 6.

Modulated enzyme-catalysed reaction. For the purposes of this example, all parameters are unity and all initial states are unity except the total enzyme amount and .

The four plots of figure 7 show the dynamic sensitivity of the normalized flows in Re:r1 and Re:r2 to step changes in , , and . In the case of and , the flow through Re:r1 changes instantaneously and that through Re:r2 has a steady-state gain of about g∞ = 1.60 for and g∞ = 0.80 for . The normalized time constant is about τ = 0.32 in each case. In the case of and , the flow through both Re:r1 and Re:r2 does not change instantly and has a steady-state gain of about g∞ = ±0.8 and time constant of about τ = 0.4.

Figure 7.

Modulated enzyme-catalysed reaction: dynamical sensitivities. The normalized temporal responses of the flows through Re:r1 and Re:r2 to perturbations in (a) ; (b) ; (c) ; (d) represented by the corresponding perturbation parameters λA, λ1, λAct and λInh, respectively. Parameters are perturbed using a 10% step change in the perturbation parameter λ. The black line is the response of the linearized sensitivity system to the step change in the perturbation parameter λ, the horizontal dashed black line the corresponding DC gain g∞ and the vertical dashed black line the corresponding time-constant τ. The coloured dashed lines show the response of the simulated (nonlinear) sensitivity system to the same perturbation in λ.

Because the dynamics of the enzyme-catalysed reaction with competitive activation and inhibition are nonlinear, the linearized gains are a function of the operating point. Figure 8a shows how the steady-state flow varies with the amount of substrate ; this is the typical reversible Michaelis–Menten curve saturating at a value dependent on the total enzyme. The system steady state is computed for a range of flows and the corresponding linearized gains are plotted in figure 8b–d. At small flows, the steady-state gains g∞ in figure 8b–d are small because they correspond to flow sensitivity. At high flows, the flow is constrained by the maximum Michaelis–Menten flow Vmax = e0κ2 Kc, where e0 is the total amount of bound and unbound enzyme; and so is independent of all of the sensitivity parameters shown except for κ2. Hence g∞ = 0 when the flow is saturated in all cases shown except for κ2.

Figure 8.

Modulated enzyme-catalysed reaction: variation of sensitivity with steady-state. (a) The steady-state flow is a nonlinear function of the substrate concentration: the classical Michaelis–Menten curve. The corresponding steady-state values of the state of each Ce component is computed for a number of values of . (b) The sensitivity gain relating flow to variation in λA is plotted against the steady-state flow . (c) As (b) but with parameters λ1 and λ2 corresponding to Re:r1 and Re:r2. (c) As (b) but with parameters λAct and λInh corresponding to Ce:Act and Ce:Inh. As expected, activation increases, and inhibition decreases, steady-state flow; in both cases, the modulation is most effective at flows corresponding to half the saturated flow.

7. Example: Pentose Phosphate Pathway

The Pentose Phosphate Pathway [67,68] provides a number of different products from the metabolism of glucose. This flexibility is adopted by proliferating cells, such as those associated with cancer, to adapt to changing requirements of biomass and energy production [69,70]. The Escherichia coli core model [71,72] is a well-documented and readily available stoichiometric model of a biomolecular system. As discussed previously [45], species, reactions and stoichiometric matrix pertaining to the Pentose Phosphate Pathway were extracted, a bond graph model created and parameters fitted using experimental data from E. coli [73]; the normalizing time [45]. The reactions used in this model are listed in appendix B.

This section examines the sensitivity properties of this model; in particular, §7.1 looks at linearized sensitivity and why it is useful; §7.2 looks at the linearization error and §7.3 examines the sensitivity from the sloppy-parameter viewpoint.

7.1. Linearized sensitivity

The sensitivity system was created using the approach of §3.2 and linearized as discussed in §§2.4 and 4. The advantage of linearization is that steady-state gains g∞ and time-constants τ can be derived directly from the system bond graph model without the need for simulation or choice of perturbation magnitude. The errors involved in this simplification are discussed in §7.2.

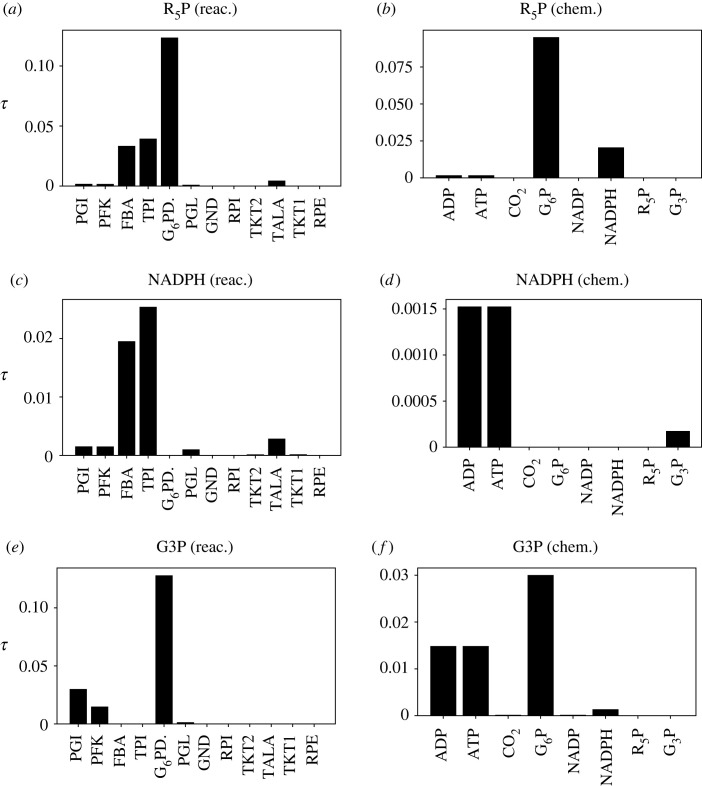

Figure 9 shows the steady-state gain g∞ from equation (2.41) for the flows of three products: , and for two cases: sensitivity with respect to reaction constants and sensitivity with respect to chemostat states. Figure 10 shows the time constant τ for each of the six cases of figure 9 computed as discussed in §2.4.

Figure 9.

Pentose Phosphate Pathway: steady-state sensitivity g∞. (a) The steady-state sensitivity g∞ of the flow of product with respect to the reaction sensitivity variables are shown for all reactions in the network. The dominant reaction is . (b) The steady-state sensitivity g∞ of the flow of product with respect to chemostat sensitivity variables . Flow is increased primarily by and ; flow is decreased primarily by . (c) As (a) but for product ; again, the dominant reaction is . (d) As (b) but for product . Again, flow is increased primarily by and . (e) As (a) but for product ; in this case, the dominant reactions are and . (f) As (b) but for product ; in this case, flow is increased primarily by and .

Figure 10.

Pentose Phosphate Pathway: sensitivity normalized time constant τ. The normalizing time [45]. (a) The sensitivity time constants τ of the flow of product with respect to the reaction sensitivity variables are shown for all reactions in the network. The sensitivity time constant for the dominant reaction is about τ = 0.1—see figure 11. (b) The sensitivity time constant τ of the flow of product with respect to chemostat sensitivity variables . The time constant for is greater than that for reflecting the greater number of intervening reactions. (c) As (a) but for product ; the sensitivity to dominant reaction has no delay (τ = 0) as is a product of that reaction. (d) As (b) but for product . The sensitivity to dominant species has no delay (τ = 0) as is a product of the same reaction. (e) As (a) but for product ; the dominant reactions and have a relatively small τ due to their proximity to this product. (f) As (b) but for product ; the dominant substrates and have relatively small τ decreasing with proximity to the product.

The rate parameter associated with has the most influence over and production (figure 9a,c). These rates of production are also most sensitive to the concentrations of and , and the concentration of has a substantial effect on its own rate of production (figure 9b,d). Different reactions and species are involved in the regulation of production, with and being the primary reactions (figure 9e); and and being the primary metabolites (figure 9f).

7.2. Linearization error

The linearized sensitivity system (§4) is an approximation to the nonlinear sensitivity system (§3.1) for two reasons: it varies with the steady state of the nonlinear system about which the linearization is performed, and the discrepancy between the linear and nonlinear system responses increases with the amplitude of the parameter variation. The former is discussed in §6, figure 8; the latter is examined further in this section in the context of the Pentose Phosphate Pathway example.

Figure 11 shows the effect of varying the amplitude of the sensitivity variable . Figure 11a gives the nonlinear deviation of the flow from its steady-state value normalized by the change in sensitivity variable for three values of the sensitivity variable . As expected, the error increases with but, in this case, a 10-fold increase only gives a 20% error. Figure 11b gives a similar result for product and figure 11c gives a similar result for substrate . Figure 11d summarizes these results in terms of the steady-state linearization error where

| 7.1 |

| 7.2 |

Figure 11.

Sensitivity approximation. (a) The flow of product is shown for a 100%, 500% and 1000% change in parameter . (b) As (a) but showing flow of product (c) As (a) but with change in the concentration of . (d) Linearization error. where g∞ is the steady-state (DC) gain of the linearized system and where is the steady-state value of in (a) and (c). The gains are shown for two cases: sensitivity of with respect to and .

7.3. Sloppy parameters

This section applies the methods of §5 to the Pentose Phosphate Pathway model. In particular, the chemostat flows associated with product are examined. Because this is a high-order system, the eigenvalue/eigenvector approach can be used to simplify the results by discarding small eigenvalues and small components of eigenvectors. In this case, eigenvalues less than 1% of the largest eigenvalue are discarded, and within each eigenvector, components less than 10% of the largest element are discarded. For illustration, the sensitivity of the flow of is investigated as all reaction constants are varied. In each case, the results using the Q∞ cost function in equation (5.9) are compared with those from Q (5.2) when the final time is chosen by the step_response function of the Python Control Systems Library [74]).

The eigenvalue σ1 and eigenvector V1 corresponding to H∞ are given by

| 7.3 |

When multiplied by , the eigenvector elements correspond to the two largest values of g∞ given in figure 9a. This illustrates the point discussed in §5: sloppy analysis of the linearized response of the sensitivity system using H∞ gives the same information as g∞ obtained without simulation.

The significant eigenvalues, and corresponding significant elements of the eigenvector corresponding to H are given by

| 7.4 |

and

| 7.5 |

As discussed in §5, H∞ corresponds to an infinite time span whereas H corresponds to the length of the simulation, in this case . Hence H is dependent on the initial, transient, part of the response whereas H∞ only depends on the steady-state response. The fact that GND appears in the eigenvectors of H, but not in the eigenvectors of H∞, implies that perturbation of GND affects the initial response but has no significant effect on the steady-state response. Indeed, the corresponding unit step response initially rises to over 10 before falling back to the steady-state value of g∞ ≈ 0.5. This behaviour is consistent with experimental evidence; in particular, while GND is not seen as the major rate-controlling step of the Pentose Phosphate Pathway [75], studies have proposed its involvement in the short-term response to oxidative stress [76].

8. Conclusion

It has been shown that the sensitivity properties of the model of a biochemical system modelled using the bond graph formulation can be examined by creating a corresponding sensitivity bond graph model. The sensitivity model can be created by either replacing bond graph components with variable parameters by a corresponding sensitivity component or via a stoichiometric approach. Either approach can be used to automatically convert the original bond graph to a sensitivity bond graph. Within the sensitivity model, the parameter variation appears as a set of additional inputs modelled as bond graph chemostat components. Hence previously developed linearization approaches can be used to linearize the nonlinear sensitivity system with respect to parameter variation to give local sensitivity results.

The well-known ‘sloppy parameter’ method, and its corresponding cost-functions have been incorporated into the sensitivity approach of this paper and lead to illuminated eigenvalue/eigenvector decomposition of a Hessian matrix associated with the local sensitivity results.

The results have been illustrated using a previously derived model of the Pentose Phosphate Pathway. In this particular case, the linearized sensitivity system is compared to the nonlinear case and found to form an accurate approximation. As is well known [67, 22.6], the reaction is an important regulator of the Pentose Phosphate Pathway; the sensitivity analysis does indeed show that product flows depend strongly on this reaction.

The methods presented here could potentially be used to analyse omics data. While statistical and bioinformatics methods can reveal analytes of interest, conducting a sensitivity analysis on a mechanistic model can help researchers to assess the importance of potential changes in these analytes. Recent metabolomics and proteomics analysis of heart tissue [77] gives experimental evidence for how disease affects the heart in terms of its biochemistry. Combining this differential omics analysis with corresponding biochemical sensitivity models will allow us to map the omics data onto medically significant physical phenomena such as cardiovascular disease. Parameters with high sensitivity may point towards potential targets for biomedical interventions.

The bond graph sensitivity system replaces parameter variation by inputs. In this paper, parameter sensitivity is examined by setting these inputs to a fixed value; future work will examine time-varying parameters as modelled by time-varying inputs to the sensitivity system.

A major challenge in systems biology is model parametrization, particularly for large-scale models [78]. Sensitivity analysis can inform experimental design to reduce uncertainty in model predictions. Our results in §7.2 indicate that not all parameters are equally important for the behaviour of a model, and that different parameters are important for describing different aspects of model behaviour. This observation has been mirrored in other sensitivity studies [56,79]. Thus, determining the ‘stiff’ combinations of parameters can help to optimize for knowledge gained with limited experimental resources. Furthermore, analysing the time constants can be used to assess the biological relevance of parameter sets in machine learning approaches to parametrization [80,81]. Our approach builds on existing techniques by reframing parameters in a thermodynamically consistent context, which can in some cases reduce the number of parameters and better distinguish between the individual contributions of reactions and metabolites [82,83].

There is a wealth of control-theoretic results applicable to linear systems. As indicated in the example of §6, modulating the parameters of enzyme-catalysed reactions is a key strategy in human cellular control systems. The sensitivity models of this paper provide a foundation for applying such control-theoretic results to understand biochemical control systems. These methods are particularly relevant for attempts to rationally engineer pathways in synthetic biology, where sensitive parameters indicate potential targets of modification [84]. In many cases, biological networks are designed to be robust to noise, independent of parameter values [85,86]. However, this robustness often comes at a cost to resource and energy consumption [41,87], and in some cases, noise is harnessed for biological control [88,89]. A bond graph modelling approach frames these behaviours in a thermodynamic context, allowing investigations into trade-offs between energy consumption and performance.

Acknowledgements

P.J.G. would like to thank the Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology, University of Melbourne, for its support via a Professorial Fellowship.

Appendix A. Example : numerical calculations

In this special case, equation (3.13) becomes

| A 1 |

When all parameters are at their nominal values so that each λ = 1

| A 2 |

Similarly in the special case, the steady-state values of and are

| A 3 |

and

| A 4 |

and when all parameters are at their nominal values

| A 5 |

and

| A 6 |

The steady-state sensitivities can be computed from equations (A 1)–(A 4) by taking derivatives and substituting unit values for the remaining λ; for example,

| A 7 |

| A 8 |

| A 9 |

Appendix B. Reactions of the Pentose Phosphate Pathway

| B 1 |

| B 2 |

| B 3 |

| B 4 |

| B 5 |

| B 6 |

| B 7 |

| B 8 |

| B 9 |

| B 10 |

| B 11 |

| B 12 |

Footnotes

Bold font is used to signify normalized variables.

Data accessibility

The figures and tables in this paper were generated using the Jupyter notebooks and Python code available from the GitHub repository: https://github.com/gawthrop/Sensitivity23.

Authors' contributions

P.J.G.: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, software, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; M.P.: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing—review and editing.

All authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Conflict of interest declaration

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

M.P. was supported by a Postdoctoral Research Fellowship from the School of Mathematics and Statistics at the University of Melbourne.

References

- 1.Huang CY, Ferrell JE. 1996. Ultrasensitivity in the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 93, 10 078-10 083. ( 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10078) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frank PM. 1978. Introduction to system sensitivity theory. New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eslami M. 1994. Theory of sensitivity in dynamic systems: an introduction. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skogestad S, Postlethwaite I. 1996. Multivariable feedback control analysis and design. New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodwin GC, Graebe SF, Salgado ME. 2001. Control system design. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winning DJ, El-Shirbeeny EHT, Thompson EC, Murray-Smith DJ. 1977. Sensitivity method for online optimisation of a synchronous generator excitation controller. Proc. IEE Part D: Contr. Theory Appl. 124, 631-638. ( 10.1049/piee.1977.0135) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eykhoff P. 1974. System identification. London, UK: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ljung L. 1999. System identification: theory for the user, 2nd edn. Information and Systems Science. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kitano H. 2002. Computational systems biology. Nature 420, 206-210. ( 10.1038/nature01254) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitano H. 2002. Systems biology: a brief overview. Science 295, 1662-1664. ( 10.1126/science.1069492) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kohl P, Crampin EJ, Quinn TA, Noble D. 2010. Systems biology: an approach. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 88, 25-33. ( 10.1038/clpt.2010.92) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zi Z. 2011. Sensitivity analysis approaches applied to systems biology models. IET Syst. Biol. 5, 336-346. ( 10.1049/iet-syb.2011.0015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cazzaniga P, et al. 2014. Computational strategies for a system-level understanding of metabolism. Metabolites 4, 1034-1087. ( 10.3390/metabo4041034) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snowden TJ, van der Graaf PH, Tindall MJ. 2017. Methods of model reduction for large-scale biological systems: a survey of current methods and trends. Bull. Math. Biol. 79, 1449-1486. ( 10.1007/s11538-017-0277-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qian G, Mahdi A. 2020. Sensitivity analysis methods in the biomedical sciences. Math. Biosci. 323, 108306. ( 10.1016/j.mbs.2020.108306) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burns JA, et al. 1985. Control analysis of metabolic systems. Trends Biochem. Sci. 10, 16. ( 10.1016/0968-0004(85)90008-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cornish-Bowden A, Luz Cárdenas M (eds). 1989. Control of metabolic processes, vol. 190. Berlin, Germany: Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fell DA. 1992. Metabolic control analysis: a survey of its theoretical and experimental development. Biochem. J. 286, 313-330. ( 10.1042/bj2860313) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heinrich R, Schuster S. 1996. The regulation of cellular systems. New York, NY: Chapman & Hall. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fell D. 1997. Understanding the control of metabolism. Frontiers in Metabolism, vol. 2. London, UK: Portland Press. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ingalls BP, Sauro HM. 2003. Sensitivity analysis of stoichiometric networks: an extension of metabolic control analysis to non-steady state trajectories. J. Theor. Biol. 222, 23-36. ( 10.1016/S0022-5193(03)00011-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ingalls BP. 2004. A frequency domain approach to sensitivity analysis of biochemical networks. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 1143-1152. ( 10.1021/jp036567u) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ingalls B. 2008. Sensitivity analysis: from model parameters to system behaviour. Essays Biochem. 45, 177-194. ( 10.1042/bse0450177) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ingalls BP. 2010. A control-theoretic interpretation of metabolic control analysis. In Control theory and systems biology (eds PA Iglesias, BP Ingalls) (Chapter 8), pp. 145–168. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- 25.Khammash M, El-Samad H. 2004. Systems biology: from physiology to gene regulation. Contr. Syst. IEEE 24, 62-76. ( 10.1109/MCS.2004.1316654) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khammash M. 2016. An engineering viewpoint on biological robustness. BMC Biol. 14, 22. ( 10.1186/s12915-016-0241-x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peter He Q, Wang J. 2020. Application of systems engineering principles and techniques in biological big data analytics: a review. Processes 8, 951. ( 10.3390/pr8080951) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gawthrop PJ, Pan M. 2022. Network thermodynamics of biological systems: a bond graph approach. Math. Biosci. 352, 108899. ( 10.1016/j.mbs.2022.108899) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pan M, Gawthrop PJ, Tran K, Cursons J, Crampin EJ. 2019. A thermodynamic framework for modelling membrane transporters. J. Theor. Biol. 481, 10-23. ( 10.1016/j.jtbi.2018.09.034) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paynter HM. 1961. Analysis and design of engineering systems. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paynter HM. 1992. An epistemic prehistory of bond graphs. In Bond graphs for engineers (eds PC Breedveld, G Dauphin-Tanguy), pp. 3–17. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: North-Holland.

- 32.Wellstead PE. 1979. Introduction to physical system modelling. New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gawthrop PJ, Smith LPS. 1996. Metamodelling: bond graphs and dynamic systems. Hemel Hempstead, UK: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mukherjee A, Karmaker R, Kumar Samantaray A. 2006. Bond graph in modeling, simulation and fault indentification. New Delhi, India: I.K. International. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karnopp DC, Margolis DL, Rosenberg RC. 2012. System dynamics: modeling, simulation, and control of mechatronic systems, 5th edn. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gawthrop PJ, Bevan GP. 2007. Bond-graph modeling: a tutorial introduction for control engineers. IEEE Control Syst. Mag. 27, 24-45. ( 10.1109/MCS.2007.338279) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oster G, Perelson A, Katchalsky A. 1971. Network thermodynamics. Nature 234, 393-399. ( 10.1038/234393a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oster GF, Perelson AS, Katchalsky A. 1973. Network thermodynamics: dynamic modelling of biophysical systems. Q. Rev. Biophys. 6, 1-134. ( 10.1017/S0033583500000081) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perelson AS. 1975. Network thermodynamics: an overview. Biophys. J. 15, 667-685. ( 10.1016/S0006-3495(75)85847-4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gawthrop PJ, Crampin EJ. 2014. Energy-based analysis of biochemical cycles using bond graphs. Proc. R. Soc. A 470, 1-25. ( 10.1098/rspa.2014.0459) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gawthrop PJ, Crampin EJ. 2016. Modular bond-graph modelling and analysis of biomolecular systems. IET Syst. Biol. 10, 187-201. ( 10.1049/iet-syb.2015.0083) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gawthrop PJ, Siekmann I, Kameneva T, Saha S, Ibbotson MR, Crampin EJ. 2017. Bond graph modelling of chemoelectrical energy transduction. IET Syst. Biol. 11, 127-138. ( 10.1049/iet-syb.2017.0006) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gawthrop P, Crampin EJ. 2018. Bond graph representation of chemical reaction networks. IEEE Trans. Nanobiosci. 17, 449-455. ( 10.1109/TNB.2018.2876391) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pan M, Gawthrop PJ, Cursons J, Crampin EJ. 2021. Modular assembly of dynamic models in systems biology. PLoS Comput. Biol. 17, e1009513. ( 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009513) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gawthrop PJ, Pan M, Crampin EJ. 2021. Modular dynamic biomolecular modelling with bond graphs: the unification of stoichiometry, thermodynamics, kinetics and data. J. R. Soc. Interface 18, 20210478. ( 10.1098/rsif.2021.0478) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gawthrop PJ, Pan M. 2022. Energy-based advection modelling using bond graphs. J. R. Soc. Interface 19, 20220492. ( 10.1098/rsif.2022.0492) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roe PH, Thoma JU. 2000. A new bond graph approach to sensitivity analysis. In Proc. of the 3rd IMACS Symp. on Mathematical Modelling (eds I Troch, F Breitenecker), pp. 743–746. Vienna, Austria: ARGESIM.

- 48.Gawthrop PJ. 2000. Sensitivity bond graphs. J. Franklin Inst. 337, 907-922. ( 10.1016/S0016-0032(00)00052-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gawthrop PJ, Ronco E. 2000. Estimation and control of mechatronic systems using sensitivity bond graphs. Control Eng. Pract. 8, 1237-1248. ( 10.1016/S0967-0661(00)00062-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Borutzky W. 2011. Incremental bond graphs. In Bond graph modelling of engineering systems (ed. W Borutzky), pp. 135–176. New York, NY: Springer. ( 10.1007/978-1-4419-9368-7_4) [DOI]

- 51.Guardabassi G, Locatelli A, Rinaldi S. 1972. Structural properties of sensitivity systems. J. Franklin Inst. 294, 241-248. ( 10.1016/0016-0032(72)90022-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Toni T, Welch D, Strelkowa N, Ipsen A, Stumpf MPH. 2008. Approximate Bayesian computation scheme for parameter inference and model selection in dynamical systems. J. R. Soc. Interface 6, 187-202. ( 10.1098/rsif.2008.0172) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gawthrop PJ. 2021. Energy-based modeling of the feedback control of biomolecular systems with cyclic flow modulation. IEEE Trans. Nanobiosci. 20, 183-192. ( 10.1109/TNB.2021.3058440) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Atkins P, de Paula J. 2011. Physical chemistry for the life sciences, 2nd edn. Oxford. UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Van Rysselberghe P. 1958. Reaction rates and affinities. J. Chem. Phys. 29, 640-642. ( 10.1063/1.1744552) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gutenkunst RN, Waterfall JJ, Casey FP, Brown KS, Myers CR, Sethna JP. 2007. Universally sloppy parameter sensitivities in systems biology models. PLoS Comput. Biol. 3, 1-8. ( 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030189) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cudmore P, Pan M, Gawthrop PJ, Crampin EJ. 2021. Analysing and simulating energy-based models in biology using BondGraphTools. Eur. Phys. J. E 44, 148. ( 10.1140/epje/s10189-021-00152-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Forrest J, Rajagopal V, Stumpf MPH, Pan M. 2023. Bondgraphs.jl: composable energy-based modelling in systems biology. bioRxiv ( 10.1101/2023.04.23.537337). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Gawthrop PJ, Cursons J, Crampin EJ. 2015. Hierarchical bond graph modelling of biochemical networks. Proc. R. Soc. A 471, 1-23. ( 10.1098/rspa.2015.0642) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Polettini M, Esposito M. 2014. Irreversible thermodynamics of open chemical networks. I. Emergent cycles and broken conservation laws. J. Chem. Phys. 141, 024117. ( 10.1063/1.4886396) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gawthrop PJ. 2017. Bond graph modeling of chemiosmotic biomolecular energy transduction. IEEE Trans. Nanobiosci. 16, 177-188. ( 10.1109/TNB.2017.2674683) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Karnopp D. 1977. Power and energy in linearized physical systems. J. Franklin Inst. 303, 85-98. ( 10.1016/0016-0032(77)90078-3) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kwakernaak H, Sivan R. 1972. Linear optimal control systems. New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kailath T. 1980. Linear systems. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hsu CS, Hou D. 1991. Reducing unstable linear control systems via real Schur transformation. Electron. Lett. 27, 984-986. ( 10.1049/el:19910614) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cornish-Bowden A. 2013. Fundamentals of enzyme kinetics, 4th edn. London, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Garrett RH, Grisham CM. 2017. Biochemistry, 6th edn. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Berg JM, Tymoczko JL, Gatto GJ, Stryer L. 2019. Biochemistry, 9th edn. New York, NY: W.H. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. 2009. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science 324, 1029-1033. ( 10.1126/science.1160809) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Patra KC, Hay N. 2014. The pentose phosphate pathway and cancer. Trends Biochem. Sci. 39, 347-354. ( 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.06.005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Orth J, Fleming R, Palsson B. 2010. Reconstruction and use of microbial metabolic networks: the core Escherichia coli metabolic model as an educational guide. EcoSal Plus 4, 1-47. ( 10.1128/ecosalplus.10.2.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Palsson B. 2015. Systems biology: constraint-based reconstruction and analysis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Park JO, Rubin SA, Xu Y-F, Amador-Noguez D, Fan J, Shlomi T, Rabinowitz JD. 2016. Metabolite concentrations, fluxes and free energies imply efficient enzyme usage. Nat. Chem. Biol. 12, 482-489. ( 10.1038/nchembio.2077) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fuller S, Greiner B, Moore J, Murray R, van Paassen R, Yorke R. 2021. The Python Control Systems Library (python-control). In 2021 60th IEEE Conf. on Decision and Control (CDC), pp. 4875–4881. Austin, TX: IEEE. ( 10.1109/CDC45484.2021.9683368) [DOI]

- 75.Moritz B, Striegel K, de Graaf AA, Sahm H. 2000. Kinetic properties of the glucose-6-phosphate and 6 phosphogluconate dehydrogenases from Corynebacterium glutamicum and their application for predicting pentose phosphate pathway flux in vivo. Eur. J. Biochem. 267, 3442-3452. ( 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01354.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Christodoulou D, Link H, Fuhrer T, Kochanowski K, Gerosa L, Sauer U. 2018. Reserve flux capacity in the pentose phosphate pathway enables Escherichia coli’s rapid response to oxidative stress. Cell Syst. 6, 569-578. ( 10.1016/j.cels.2018.04.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li M, et al. 2020. Core functional nodes and sex-specific pathways in human ischaemic and dilated cardiomyopathy. Nat. Commun. 11, 2843. ( 10.1038/s41467-020-16584-z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Babtie AC, Stumpf MPH. 2017. How to deal with parameters for whole-cell modelling. J. R. Soc. Interface 14, 20170237. ( 10.1098/rsif.2017.0237) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Monsalve-Bravo GM, et al. 2022. Analysis of sloppiness in model simulations: unveiling parameter uncertainty when mathematical models are fitted to data. Sci. Adv. 8, eabm5952. ( 10.1126/sciadv.abm5952) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Choudhury S, Moret M, Salvy P, Weilandt D, Hatzimanikatis V, Miskovic L. 2022. Reconstructing kinetic models for dynamical studies of metabolism using generative adversarial networks. Nat. Mach. Intell. 4, 710-719. ( 10.1038/s42256-022-00519-y) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Choudhury S, Narayanan B, Moret M, Hatzimanikatis V, Miskovic L. 2023. Generative machine learning produces kinetic models that accurately characterize intracellular metabolic states. bioRxiv, p. 2023.02.21.529387. ( 10.1101/2023.02.21.529387) [DOI]

- 82.Ederer M, Dieter Gilles E. 2007. Thermodynamically feasible kinetic models of reaction networks. Biophys. J. 92, 1846-1857. ( 10.1529/biophysj.106.094094) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mason JC, Covert MW. 2019. An energetic reformulation of kinetic rate laws enables scalable parameter estimation for biochemical networks. J. Theor. Biol. 461, 145-156. ( 10.1016/j.jtbi.2018.10.041) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shaw WM, et al. 2019. Engineering a model cell for rational tuning of GPCR signaling. Cell 177, 782-796. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2019.02.023) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Araujo RP, Liotta LA. 2018. The topological requirements for robust perfect adaptation in networks of any size. Nat. Commun. 9, 1-12. ( 10.1038/s41467-018-04151-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Araujo R, Liotta L. 2023. Universal structures for embedded integral control in biological adaptation. Nat. Commun. 14, 2251. ( 10.1038/s41467-023-38011-9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Forrest J, Pan M, Crampin EJ, Rajagopal V, Stumpf MPH. 2023. Energy dependence of signalling dynamics and robustness in bacterial two component systems. bioRxiv, 2023.02.12.528212. ( 10.1101/2023.02.12.528212) [DOI]

- 88.Locsei JT. 2007. Persistence of direction increases the drift velocity of run and tumble chemotaxis. J. Math. Biol. 55, 41-60. ( 10.1007/s00285-007-0080-z) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Song S, et al. 2021. Engineering transient dynamics of artificial cells by stochastic distribution of enzymes. Nat. Commun. 12, 1-9. ( 10.1038/s41467-021-27229-0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The figures and tables in this paper were generated using the Jupyter notebooks and Python code available from the GitHub repository: https://github.com/gawthrop/Sensitivity23.