Abstract

Background

Perry disease (or Perry syndrome [PS]) is a hereditary neurodegenerative disorder inevitably leading to death within few years from onset. All previous cases with pathological confirmation were caused by mutations within the cytoskeleton‐associated protein glycine‐rich (CAP‐Gly) domain of the DCTN1 gene.

Objectives

This paper presents the first clinicopathological report of PS due to a novel DCTN1 mutation outside the CAP‐Gly domain.

Methods

Clinical and pathological features of the new variant carrier are compared with another recently deceased PS case with a well‐known pathogenic DCTN1 mutation and other reported cases.

Results and Conclusions

We report a novel DCTN1 mutation outside the CAP‐Gly domain that we demonstrated to be pathogenic based on clinical and autopsy findings.

Keywords: DCTN1, parkinsonism, TDP‐43, hypoventilation, weight loss

Perry disease (or Perry syndrome [PS]) is a rare autosomal‐dominant neurodegenerative disorder featuring parkinsonism, neuropsychiatric features (primarily apathy and depression), weight loss, and central hypoventilation. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 It is rapidly progressive, with death usually within 5.5 years from onset. 5 Neuropathologically, it is characterized by the accumulation of transactive response DNA binding protein of 43 kDa (TDP‐43) with a distinct distribution and morphological pattern. 6 Identification of the DCTN1 gene mutations as a genetic cause of PS enabled a definite diagnosis during a patient's life and increased the recognition of the disease. 1 , 7

This article adds to the growing knowledge on the genetic, clinical, and pathologic characteristics of PS by presenting a case with a novel DCTN1 mutation beyond the classic genetic locus of PS, and comparing their clinicopathological features with another recently deceased PS patient with well‐known pathogenic DCTN1 mutation.

Methods

The historical and clinical data were obtained by movement disorder specialists (J.D. and Z.K.W.) through personal patient evaluation, including history taking, neurological examination, and medical chart review. Genetic testing included whole exome sequencing, mitochondrial sequencing, repeat expansion testing for dominant spinocerebellar ataxia genes, and copy number variant analysis via chromosome microarray. Neuroimaging studies included brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and brain single‐photon emission computerized tomography (SPECT) with dopamine transporter imaging with ioflupane (DaTscan). The autopsy was performed on two patients.

Results

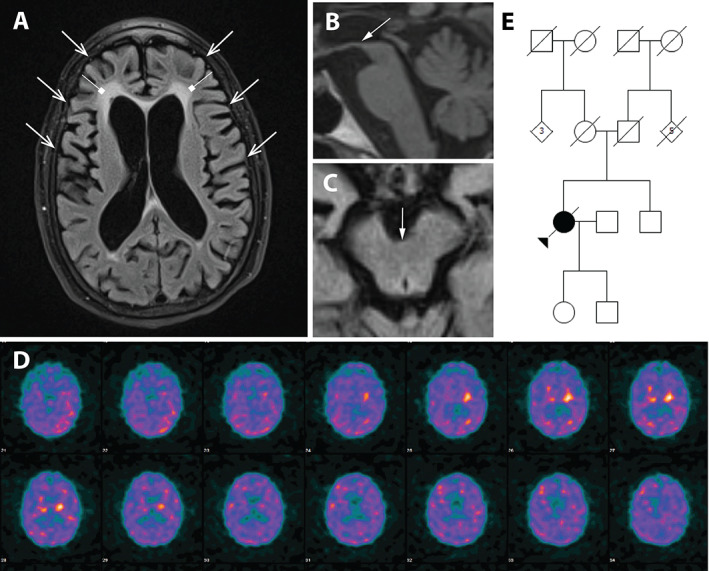

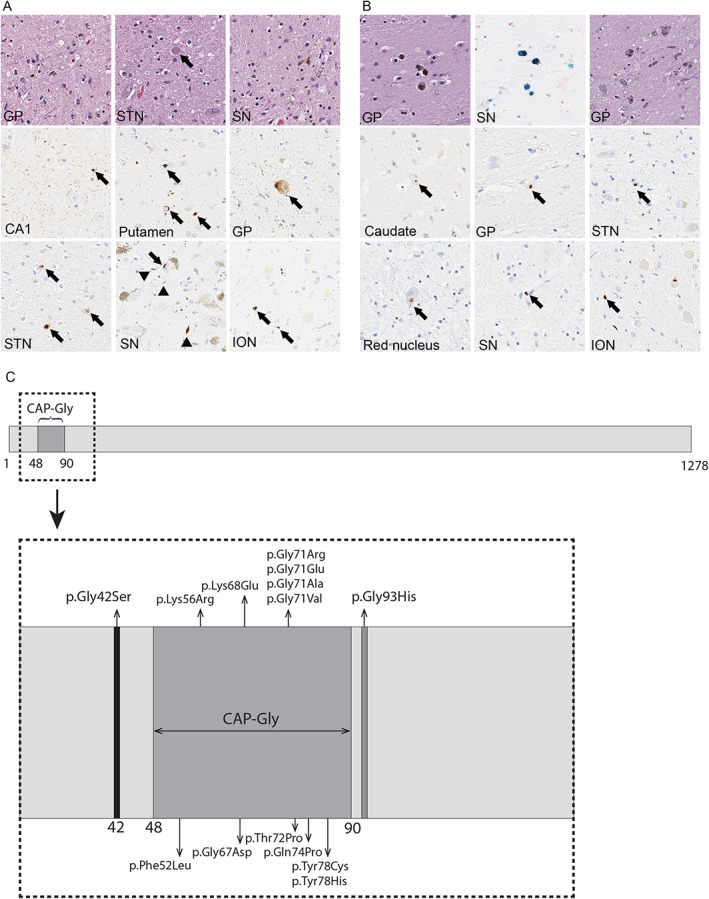

A 58‐year‐old female (case 1) of Irish descent developed apathy and social withdrawal, followed by emotional detachment, attention deficits, and forgetfulness. Additionally, she became preoccupied most of the time with repeated semi‐purposeful tasks (cleaning the house, tracing, and retracing the pattern of her gown). At 64 years, she was suspected of depression and underwent psychotherapy with no effect. Subsequently, her gait became slower with decreased arm swing bilaterally and a stooped posture. She was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease (PD) and was started on levodopa/carbidopa 600/150 mg and pramipexole 2.25 mg with suboptimal improvement. The neuropsychological evaluation at 65 years old showed mild cognitive impairment. She also developed urinary urgency with occasional incidents of incontinence at night and decreased sweating. Polysomnography study (PSG) at 66 years revealed mild obstructive sleep apnea with an apnea‐hypopnea index of 8.5 and sleep efficiency of 20.2%. She spent 45.1%, 33.2%, 0%, and 21.7% of her sleep in stages N1, N2, N3, and rapid eye movement (REM), respectively. Limb activity or features of REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) were not observed. On neurological examination at 68 years, she responded only with yes/no or head nodding, often inappropriately, and scored 16/30 at Mini‐Mental State Examination. She had hypophonia, limited upgaze, and asymmetric parkinsonism (bradykinesia, rigidity, impaired posture, and balance) more pronounced on the left side, brisk tendon reflexes, and Babinski sign on the left. Her weight had decreased by 10 kg since the disease onset (over the course of 10 years). Brain MRI demonstrated moderate cerebral atrophy most prominent in the frontal lobes bilaterally and midbrain (Fig. 1A‐C). SPECT‐DaTscan showed severe presynaptic dopaminergic deficit, worse on the right side (Fig. 1D). She had one sibling, a 66‐year‐old brother, who was healthy at the time of manuscript preparation. Her parents and multiple relatives lived up to 80 or 90 years without similar symptoms (Fig. 1E). Whole exome sequencing revealed a novel heterozygous DCTN1 mutation (NM_004082.4:c.124G > A; Gly42Ser). At 69 years, the patient developed episodes of irregular breathing and pauses in breathing; however, her motor state remained stable (Video 1). The follow‐up PSG at 68 years showed a normal central and obstructive apnea index of 1 and 1, respectively. Sleep efficiency was 90%, and she spent 14%, 53%, 0%, and 34% of her sleep in stages N1, N2, N3, and REM, respectively. The patient was admitted to a hospice and died several months later at 69 years. At brain autopsy, the fixed left hemibrain weighed 460 grams. The macroscopic evaluation showed mild cortical atrophy in the dorsolateral, anterior, and medial frontal lobe, with marked enlargement of the frontal and moderate enlargement of the temporal horn of the lateral ventricle. The hippocampal formation had moderate atrophy. There was markedly decreased pigmentation in the substantia nigra and mild decrease in the locus ceruleus. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining revealed neuronal loss and gliosis with iron‐type pigment and granular foamy axonal spheroids (pigment‐spheroid degeneration) in the globus pallidus and subthalamic nucleus (Fig. 2A). The substantia nigra had marked neuronal loss with extraneuronal neuromelanin and gliosis, most marked in medial cell groups (Fig. 2A). The findings were associated with pigment‐spheroid degeneration in a pallidonigroluysial distribution (PNLA). PNLA is often associated with tauopathies, such as progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) and corticobasal degeneration, 8 , 9 but tau immunohistochemistry in multiple brain regions did not reveal a tauopathy. Instead, phospho‐TDP‐43 immunohistochemistry evidenced neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions (NCIs), dystrophic neurites (DNs), and perivascular glial inclusions (PVGs) in the affected regions, including the basal ganglia and substantia nigra, but minimal involvement of the medial temporal structures and the neocortex (Fig. 2A). The neuronal intranuclear inclusions were sparse in the nucleus basalis of Meynert and pontine tegmentum. The distribution and severity of each TDP‐43 lesion in 22 regions are summarized in Table S1., which is consistent with the typical distribution of PS.

FIG 1.

Moderate cerebral atrophy (open arrows) most prominent in the frontal lobes bilaterally, nonspecific periventricular white matter changes (square arrows), and midbrain atrophy (arrows), axial fluid‐attenuated inversion‐recovery (FLAIR) T2 fat‐suppressed (A), on sagittal T1 (B), and axial T1 (C) magnetic resonance imaging sequences. Severe presynaptic dopaminergic deficit, worse on the right side, on single‐photon emission computerized tomography‐dopamine transporter imaging with ioflupane (D). Family pedigree of case 1 (E). For family pedigree standard pedigree symbols are used; arrow indicates the proband; circles indicate females; squares indicate males; diamond indicate undetermined gender; numbers inside the diamonds indicate number of individuals; slash through symbols indicate diseased individuals; black symbol indicates individual diagnosed with Perry disease.

VIDEO 1.

Video of a case 1 at 69‐years‐old, 6 months before her death. The patient displays parkinsonian gait with reduced arm swing L > R, small steps, and leaning forward.

FIG 2.

Representative histopathological findings of cases 1 and 2, carriers of DCTN1 Gly42Ser and Gly71Glu mutations, respectively. (A) Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and phospho‐TDP‐43 immunohistochemistry in US‐1. H&E staining reveals neuronal loss and gliosis with spheroids in the globus pallidus (GP), subthalamic nucleus (STN; the arrow indicates a spheroid), and substantia nigra (SN). Phospho‐TDP‐43 immunohistochemistry reveals numerous fine neurites with perivascular glial inclusions (arrow) in the CA1 sector of the hippocampus, pleomorphic neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions in the caudate nucleus (Caudate) and subthalamic nucleus (STN), spheroids in the GP (arrow), neuronal cytoplasmic inclusion (arrow) and dystrophic neurites (arrowheads) in the SN, and perivascular glial inclusions (arrows) in the inferior olivary nucleus (ION). (B) Representative images of H&E staining, Prussian Blue staining, phospho‐TDP‐43 immunohistochemistry in PL‐3. The GP shows minimal neuronal loss and mild perivascular iron pigment, which is more visible on Prussian Blue staining. The substantia nigra has neuronal loss with extraneuronal neuromelanin and gliosis. Phospho‐TDP‐43 immunohistochemistry reveals neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions (arrows) in the Caudate, GP, STN, and red nucleus. The perivascular glial inclusions (arrows) are observed in the substantia nigra and inferior olivary nucleus. (C) Visual depiction of DCTN1 gene, including the cytoskeleton‐associated protein glycine‐rich (CAP‐Gly) domain, the new and all of the previously reported pathogenic mutation in Perry disease.

The previously reported patient 1 , 10 (case 2), carried the NM_004082.5 (DCTN1):c.212G > A (Gly71Glu) mutation and died after 9 years from the PS onset. At brain autopsy, the fixed left hemibrain weighed 620 grams. Macroscopically, mild atrophy of the basal ganglia and subthalamic nucleus was observed. The globus pallidus showed rusty color. The substantia nigra and the locus ceruleus have decreased neuromelanin pigmentation and increased in a rust‐like color. Microscopically, the striatum showed minimal neuronal loss and mild perivascular iron pigment (Fig. 2B). The ventromedial part of the globus pallidus had neuronal loss and gliosis accompanied by granular axonal spheroids and iron‐type pigment. The ventromedial thalamus and the hypothalamus had subtle gliosis, and the subthalamic nucleus had a relatively normal neuronal population. The substantia nigra had neuronal loss with extraneuronal neuromelanin, gliosis and axonal spheroids, which were most marked in the medial and ventrolateral cell groups. TDP‐43 immunohistochemistry revealed NCIs, DNs, and PVG predominantly in the striatum and brainstem (Fig. 2B), but no neuronal intranuclear inclusions. The neuropathologic findings were consistent with PS (Table S1.).

Discussion

The dynactin complex consists of 11 subunits interacting with dynein to form a motor complex essential for intracellular and axonal cargo trafficking. 1 , 2 , 11 DCTN1 encodes the largest subunit, which is particularly important for retrograde axonal transport. 12 It consists of 1278 amino acids, with its N‐terminal containing cytoskeleton‐associated protein glycine‐rich (CAP‐Gly) domain (Fig. 2C). The domain is located within the 48 to 90 amino acids and plays a crucial role in binding the dynactin‐dynein complex to microtubules and initiating retrograde transport. 11 The novel DCTN1 Gly42Ser mutation was located on exon 2 of the DCTN1 gene, but beyond the CAP‐Gly domain. The computational (in silico) predictions with the Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor v108 13 implied it was pathogenic (CADD, PolyPhen‐2, and SIFT score of 27, 1, and 0, respectively), and it was likely pathogenic according to the ACMG‐AMP criteria (PS4, PM2, PM6, PP2, PP3, and PP4). 14

To date, 13 pathogenic mutations were described in PS, with 12 localized within the CAP‐Gly domain (Fig. 2C). 1 In 2021, Zhang and colleagues 12 reported a novel pathogenic mutation, Gln93His, spaced just two amino acids apart from the CAP‐Gly domain. Interestingly, this mutation manifested predominantly as distal hereditary motor neuronopathy type 7B, with only few patients having symptoms suggestive of PS. However, no pathologic study was conducted.

The age of onset in case 1 was similar to that of the previously reported PS patients. The disease started with neuropsychiatric symptoms, the most common initial manifestation of PS. 15 In the following years, she also developed parkinsonism, weight loss, cognitive decline, respiratory symptoms, and dysautonomia. The neuropathological examination revealed TDP‐43 pathology with predominant pallidonigral involvement, similar to case 2 and other previously reported PS patients.

Case 1 also displayed features overlapping with PSP. 1 , 3 , 10 , 15 Despite observed respiratory symptoms in case 1, PSG studies did not evidence central hypoventilation. As the mean disease duration in PS is 5.5 years, 5 and respiratory failure is the most common cause of death, case 1 had a relatively late onset of respiratory symptoms. Interestingly, hypoventilation was absent in 4/31 of the previously published PS families. 1 Two of these families had Lys56Arg and the other two had Gly71Ala and Tyr78Cys mutations. In the newly published report of two new pedigrees with Gly71Ala mutations, only 1 of 3 reported patients displayed hypoventilation. 16 Another DCTN1 mutation, Phe52Leu, was associated with a later disease onset and slower progression in PS. 17 , 18 Therefore, genotype–phenotype correlations most likely exist. Moreover, some features, such as respiratory symptoms in case 1, may be difficult to identify, even with as sensitive techniques as repeated PSG.

We recently demonstrated that PS might mimic PD with asymmetric parkinsonism, marked and sustained response to levodopa, and levodopa‐induced peak‐of‐dose dyskinesia. 1 , 19 Moreover, previous studies reported that many cases of PS were initially diagnosed as PD or atypical parkinsonism. 1 , 10 However, the constellation of parkinsonism, apathy/depression, respiratory symptoms, and weight loss is pathognomonic for PS and should always raise suspicion of this disease. It is important to increase the levodopa dose slowly to minimize the risk of potential adverse effects (eg, gastrointestinal symptoms, orthostatic hypotension). 1 , 10 , 20 Mechanical ventilation can efficiently manage respiratory symptoms and significantly extend life expectancy. As in other neurodegenerative disorders with respiratory failure, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, the fact that mechanical ventilation may considerably prolong survival also raises the question of quality of prolonged life and ethical concerns when making the decision to start mechanical ventilation. However, because PS is very rare, clinicians are unlikely to discuss personalized prognosis at the time of diagnosis 21 , 22 , 23 because of lack of data on large patient cohorts but may consider doing so after a few years of the patient's follow‐up, knowing the individual pattern of disease progression.

The limitation of the present study is the lack of segregation analysis and low sample count. However, as clinical and autopsy findings were consistent with the previously diagnosed representative patient with PS, as documented in Figure 2A,B, and the novel DCTN1 mutation was predicted pathogenic by in silico algorithms, we were able to demonstrate the novel DCTN1 mutation outside CAP‐Gly domain was pathogenic.

In conclusion, the clinical and pathophysiological spectrum of PS is still being uncovered. Further advances in understanding the disease will pave the way toward improved treatment and better quality of life and life expectancy.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author Roles

(1) Research project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution; (2) Manuscript: A. Writing of the First Draft, B. Review and Critique.

J.D.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2A, 2B.

S.K.: 1C, 2A, 2B.

P.P.L.: 1C, 2B.

E.J.S.: 1C, 2B.

A.A.B.: 1C, 2B.

J.S.: 1B, 1C, 2B.

D.W.D.: 1B, 1C, 2B.

Z.K.W.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2B.

Disclosures

Ethical Compliance Statement: The institutional review boards (IRB) of the Medical University of Gdansk and Mayo Clinic approved the ethical aspects of the study. We collected written informed consent from all patients or the legal next‐of‐kin. Brain autopsies were performed after consent of the legal next‐of‐kin or individuals with legal authority to grant permission for autopsy. De‐identified studies of autopsy samples are considered exempt from human subject research by the Mayo Clinic IRB. We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this work is consistent with those guidelines.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest: Funding was received by the Mayo Clinic Florida Department of Neurology Discretional Fund and the Haworth Family Professorship in Neurodegenerative Diseases fund. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Financial Disclosures for the Previous 12 Months: J.D. reports the following: he is employed by the Medical University of Gdansk, Copernicus PL, and MJ Jaroslaw Dulski. He has received honoraria from VM Media, Radosław Lipiński 90 Consulting, and Ipsen; and he has received grants from the Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange (BPN/WAL/2022/1/00007/U/00001) and the Haworth Family Professorship in Neurodegenerative Diseases fund. S.K. reports the following: he is employed by the Mayo Clinic; he has received grants from CurePSP and Rainwater Charitable Foundation. P.P.L. reports the following: he is employed by the Medical University of Lodz, Poland, The Mazovian State University in Plock, Poland and the Institute of the Polish Mother's Health Center in Lodz, Poland. E.J.S. reports the following: she has received consultancies from Cogstate; she is employed by the Medical University of Gdansk, Copernicus PL, and Gdanskie Centrum Zdrowia; she has received honoraria from Biogen, Polpharma, Alfakonferencje, Via Medica, and 90 Consulting. A.A.B. reports the following: he has stock ownership in medically‐related fields in CARA, ORMP, MDWD, and CANF (none relevant nor pertinent to this case); he is employed by Johns Hopkins Medicine; he has received honoraria from Tarsus Medical Speaker. J.S. reports the following: he has received consultancies from Allergan, AbbVie, Ipsen, Everpharma, Merz, Novartis, Biogen, Roche, and TEVA; he is employed by the Medical University of Gdansk, Copernicus PL; he has contracts withAllergan, AbbVie, Ipsen, Everpharma, Merz, Novartis, Biogen, Roche, and TEVA; he has received honoraria from Allergan, AbbVie, Ipsen, Everpharma, Merz, Novartis, Biogen, Roche, TEVA, and the Polish Neurological Society (co‐editor‐in‐chief of Neurologia I Neurochirurgia Polska). D.W.D. reports the following: he is employed by the Mayo Clinic; he has received grants from National Institutes of Health (NIH) (P30 AG062677, U19 AG063911). Z.K.W. reports the following: he has intellectual property rights in the Mayo Clinic and Z.K.W. has a financial interest in technologies entitled, “Identification of Mutations in PARK8, a Locus for Familial Parkinson's Disease” and “Identification of a Novel LRRK2 Mutation, 6055G>A (G2019S), Linked to Autosomal Dominant Parkinsonism in Families from Several European Populations”. Those technologies have been licensed to a commercial entity, and to date, Z.K.W. has received royalties <$1.500 through Mayo Clinic in accordance with its royalty sharing policies. He has received consultancies and advisory boards fees from Vigil Neuroscience; he is employed by the Mayo Clinic, Florida; he has received honoraria from the Polish Neurological Society and is the co‐editor‐in‐chief of Neurologia i Neurochirurgia Polska; he has received grants from the NIH/NIA and NIH/NINDS (1U19AG063911, FAIN: U19AG063911), Mayo Clinic Center for Regenerative Medicine, Mayo Clinic APDA Center for Advanced Research; he has received gifts from the Donald G. and Jodi P. Heeringa Family, the Haworth Family Professorship in Neurodegenerative Diseases fund, and The Albertson Parkinson's Research Foundation. He serves as PI or Co‐PI on Biohaven Pharmaceuticals (BHV4157‐206), Neuraly (NLY01‐PD‐1), and Vigil Neuroscience (VGL101‐01.002, PET tracer development protocol, and CSF1R biomarker and repository project) grants.

Supporting information

Table S1. Comparison of the distribution and severity of TDP‐43 pathology in Cases 1 and 2.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients and their families for participating in the research and their contribution to the field. Ms. Martyna Dulska, B.S., M.Arch. helped with the artwork. Dr. Ewa Golańska from Medical University of Lodz, Poland, and Ms. Audrey J. Strongosky C.C.R.C. from Mayo Clinic, Florida, helped with the logistics. Ms. Monica Castanedes‐Casey and Mr. Nicholas B. Martin from Mayo Clinic, Florida, helped with the histology processing, immunohistochemistry, and scanning slides.

Relevant disclosures and conflict of interest are listed at the end of this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Dulski J, Cerquera‐Cleves C, Milanowski L, et al. Clinical, pathological and genetic characteristics of Perry disease‐new cases and literature review. Eur J Neurol 2021;28(12):4010–4021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dulski J, Konno T, Wszolek Z. DCTN1‐related neurodegeneration. 2010 Sep 30 [updated 2021. Aug 5]. In: Adam MP, Everman DB, Mirzaa GM, et al., eds. GeneReviews(®). Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; Copyright © 1993–2023, University of Washington, Seattle. GeneReviews is a registered trademark of the University of Washington, Seattle. All rights reserved., 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Konno T, Ross OA, Teive HAG, Sławek J, Dickson DW, Wszolek ZK. DCTN1‐related neurodegeneration: Perry syndrome and beyond. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2017;41:14–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jecmenica Lukic M, Kurz C, Respondek G, et al. Copathology in progressive supranuclear palsy: does it matter? Mov Disord 2020;35(6):984–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tsuboi Y, Mishima T, Fujioka S. Perry disease: concept of a new disease and clinical diagnostic criteria. J Mov Disord 2021;14(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mishima T, Koga S, Lin WL, et al. Perry syndrome: a distinctive type of TDP‐43 Proteinopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2017;76(8):676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wittke C, Petkovic S, Dobricic V, et al. Genotype‐phenotype relations for the atypical parkinsonism genes: MDSGene systematic review. Mov Disord 2021;36(7):1499–1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ahmed Z, Josephs KA, Gonzalez J, DelleDonne A, Dickson DW. Clinical and neuropathologic features of progressive supranuclear palsy with severe pallido‐nigro‐luysial degeneration and axonal dystrophy. Brain 2008;131(Pt 2):460–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ghayal N, Koga S, Josephs K, Ahlskog J, Wszolek Z, Dickson D. Corticobasal degeneration with pallidonigroluysial atrophy and TDP‐43 pathology: a distinct clinicopathologic variant. J Neuropathol Exp Neurology 2019;78(6): Oxford Univ Press Inc Journals Dept, 2001 Evans Rd, Cary, NC 27513, USA. p. 520–520. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dulski J, Cerquera‐Cleves C, Milanowski L, et al. L‐dopa response, choreic dyskinesia, and dystonia in Perry syndrome. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2022;100:19–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Deshimaru M, Kinoshita‐Kawada M, Kubota K, et al. DCTN1 binds to TDP‐43 and regulates TDP‐43 aggregation. Int J Mol Sci 2021;22(8):1–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhang J, Wang H, Liu W, et al. A novel Q93H missense mutation in DCTN1 caused distal hereditary motor neuropathy type 7B and Perry syndrome from a Chinese family. Neurol Sci 2021;42(9):3695–3705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cunningham F, Allen JE, Allen J, et al. Ensembl 2022. Nucleic Acids Res 2022;50(D1):D988–D995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med 2015;17(5):405–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Milanowski Ł, Sitek EJ, Dulski J, et al. Cognitive and behavioral profile of Perry syndrome in two families. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2020;77:114–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stoker TB, Dostal V, Cochius J, et al. DCTN1 mutation associated parkinsonism: case series of three new families with Perry syndrome. J Neurol 2022;269:6667–6672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Araki E, Tsuboi Y, Daechsel J, et al. A novel DCTN1 mutation with late‐onset parkinsonism and frontotemporal atrophy. Mov Disord 2014;29(9):1201–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Honda H, Sasagasako N, Shen C, et al. DCTN1 F52L mutation case of Perry syndrome with progressive supranuclear palsy‐like tauopathy. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2018;51:105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Martin WRW, Miles M, Zhong Q, et al. Is levodopa response a valid indicator of Parkinson's disease? Mov Disord 2021;36(4):948–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jost W, Altmann C, Fiesel T, Becht B, Ringwald S, Hoppe T. Influence of levodopa on orthostatic hypotension in Parkinson's disease. Neurol Neurochir Pol 2020;54(2):200–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Barć K, Kuźma‐Kozakiewicz M. Gastrostomy and mechanical ventilation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: how best to support the decision‐making process? Neurol Neurochir Pol 2020;54(5):366–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Westeneng HJ, Debray TPA, Visser AE, et al. Prognosis for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: development and validation of a personalised prediction model. Lancet Neurol 2018;17(5):423–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. van Eenennaam RM, Koppenol LS, Kruithof WJ, et al. Discussing personalized prognosis empowers patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis to regain control over their future: a qualitative study. Brain Sci 2021;11(12):1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Comparison of the distribution and severity of TDP‐43 pathology in Cases 1 and 2.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.