Abstract

An increasing number of publications over the past ten years have focused on the development of chitosan-based cross-linked scaffolds to regenerate bone tissue. The design of biomaterials for bone tissue engineering applications relies heavily on the ideals set forth by a polytherapy approach called the “Diamond Concept”. This methodology takes into consideration the mechanical environment, scaffold properties, osteogenic and angiogenic potential of cells, and benefits of osteoinductive mediator encapsulation. The following review presents a comprehensive summarization of recent trends in chitosan-based cross-linked scaffold development within the scope of the Diamond Concept, particularly for nonload-bearing bone repair. A standardized methodology for material characterization, along with assessment of in vitro and in vivo potential for bone regeneration, is presented based on approaches in the literature, and future directions of the field are discussed.

Keywords: Chitosan-Based Scaffolds, Bone Tissue Engineering, Diamond Concept, Cross-linking, Osteogenic Cells, Growth Factors

1. Introduction

Advancement of the bone tissue engineering field in recent years has opened new potentials for the design of alternative treatments of various orthopedic conditions. Naturally, bone tissue relies on its self-healing capabilities through direct or indirect healing, but this can be hindered following severe traumas or other underlying conditions.1−3 Current conventional bone graft treatments, while advantageous in some respects, present many limitations including invasiveness, donor site morbidity, limited graft volume, and long hospitalization times.4−10

Interest has since shifted to the design and implementation of tissue engineered substitutes. These designs focus on targeting the regeneration of native tissue both at the structural and functional level using a complex polytherapy approach called the “Diamond Concept”.9,11−13 This design framework established by Giannoudis et al. provides a guideline for the minimal requirements needed for efficient bone healing: osteoconductive scaffolds, osteogenic and angiogenic cells, osteoinductive mediators, and a suitable mechanical environment9−12,14−16 (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Comprehensive overview of the literature review presented in this manuscript. (A) “Diamond Concept” for Bone Regeneration, which encompasses an osteoconductive scaffold, osteogenic cells, osteoinductive mediators, and vascularization in a suitable mechanical environment. This builds the foundation for the organization of the review. (B) Increasing number of publications within the chitosan-based cross-linked scaffold/hydrogel domain for bone tissue engineering applications in the last 20 years. (C) The review’s novelty within the combined domain of chitosan based cross-linked hydrogel/scaffolds for bone tissue engineering applications implementing the Diamond Concept.

Each component within this approach plays a critical role in the overall ability of the biological substitute for bone healing and regeneration.12,15,17−21 The biomaterial scaffold acts as a 3D microenvironment for cells by providing structural support thereby necessitating similarities in mechanical properties between a chosen biomaterial and native tissue environment. In terms of bone regeneration, the scaffold needs to have a sufficiently high mechanical strength,22−24 in addition to a biodegradation rate similar to that of new bone tissue formation.12,25−30 The architecture of the scaffold should be porous to allow for cellular migration and vascular network infiltration.17,31

Incorporation of cells is also necessary since cells are responsible for the secretion of the extracellular matrix along with different growth factors and cytokines involved in tissue healing.32,33 For bone applications, this aspect often encompasses osteoblast lineage cells such as preosteoblasts since they are already lineage committed and require less effort in differentiation processes.33,34 More recent work has also focused on the usage of mesenchymal stem cells with subsequent differentiation once encapsulated in the scaffold.33,35 Finally, osteoinductive mediators such as bone morphogenetic proteins 2, 4, and 7 (BMP2, 4, 7) are a crucial consideration as their incorporation aids in developing the scaffold into an optimal environment for cell growth, differentiation, and new tissue formation.20,36−42 While the three previously discussed components make up the tissue engineering triad for the regeneration of many tissues, vascularization and mechanical environment are specific considerations for bone applications.43 These are added due to the complex nature of bone tissue thereby necessitating a more complex design approach.

Polymers represent the largest class of biomaterials investigated for various biomedical and tissue engineering purposes. These chains of repeating monomers can be sourced naturally such as chitosan, alginate, and collagen or fabricated synthetically like poly(glycolic acid) (PGA), poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), and poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA), among many others.44−47 As evidenced throughout the literature, chitosan is among the most widely investigated polymers for the design of ideal scaffolds for bone tissue engineering.44−46,48 Its usage is often compounded with a physical or chemical cross-linker, which serves to improve material properties such as compressive strength, elastic modulus, degradation rate, structural stability, and architecture.44,48−51 The implementation of cross-linking for chitosan-based scaffolds in bone applications has continued to become more popular in literature studies, thus requiring a more thorough investigation of its demonstrated benefits (Figure 1B).

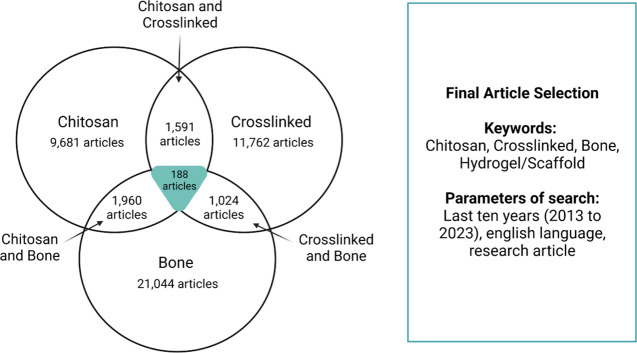

In the scope of this review, we aim to provide in-depth comparisons of material and osteogenic properties for chitosan-based cross-linked scaffolds within the ideals of the Diamond Concept for bone tissue engineering of nonload bearing tissues. Each subcategory of the Diamond Concept will be discussed according to the most recent advances in that component. This literature review is to our knowledge the first of its kind to review the design of chitosan based cross-linked scaffolds for bone in this manner (Figure 1C). To accomplish this, a literature search was conducted using the SCOPUS database with keywords: chitosan, cross-linked, and bone, and resulting articles were further screened for availability and intended application (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Results of literature search conducted for this manuscript. The search was performed using the keywords: Chitosan, Crosslinked (or Cross-linked), Bone, and Scaffold or Hydrogels. These results were also limited to publications from the last ten years and written in the English language. From this search, 188 articles were found to be suitable and screened further to examine the specific target of the study.

Although the need for assessment of scaffold material properties and bone regenerative capabilities is evident in many studies found in the literature, no clear set standardized methodology has been presented in the literature for bone applications. Thus, our additional goal of this review is to highlight the most popular methods of experimental testing to drive the construction of a more standardized methodology in the development of biomaterial substitutes for bone.

2. Chitosan as a Biomaterial

Among the various polymers available for scaffold fabrication, chitosan remains one of the most attractive biomaterials in the field due to various desirable inherent properties such as excellent biocompatibility and biodegradability, antibacterial properties, as well as its mucoadhesive nature and versatility for further chemical and physical modification.46,52,53 Chitosan is derived from chitin through the deacetylation of N-acetylglucosamine residues into N-glucosamines following treatment with an alkaline compound. Similarities in structure between the attained chitosan and glycosaminoglycans found in the extracellular matrix provide chitosan biomaterials with the ability to interact well with cells.54 Numerous studies have demonstrated the material’s potential for bone applications since it can support the proliferation and adhesion of osteoblastic lineage cells as well as mesenchymal stem cells.22,54 Further to this benefit, the wide abundance of chitin in nature designates chitosan as an accessible and cost-effective biomaterial for use in many different applications including both tissue engineering and pharmaceuticals.53

The physicochemical and biological properties of chitosan are largely influenced by its degree of deacetylation, which is defined by the percentage of N-glucosamine residues formed.55,56 Degree of deacetylation (DD) of commercially available chitosan can vary from low (<50%) to full deacetylation (100%), but many studies have shown that a higher DD is favorable in bone tissue regeneration.57 These newly formed amine groups allow for chitosan to become soluble under dilute acidic conditions, which yields the advantage of fabricating minimally invasive, injectable chitosan-based scaffolds. Use of chitosan with a higher DD often correlates with higher solubility and offers more protonated sites that can be exploited to modify the chitosan chains or complex them with other biomaterials, lipids, proteins, and genetic material for a wide range of therapeutic applications.57 These chemical modifications of chitosan solutions such as quaternized, carboxyalkyl, and thiolated chitosan have more recently emerged as additional options for base materials in designed bone regenerative scaffolds since they aid in attaining more optimal material properties.54

3. Cross-linking for Chitosan Scaffolds

Although chitosan possesses many beneficial properties for consideration as a biomaterial substitute, previous literature has shown insufficiencies in certain parameters of the material needed to achieve optimal bone healing.58−60 For instance, chitosan lacks the necessary mechanical strength for bone related applications and exhibits issues with stability and control of biodegradation rates.44,48−50,61,62 To overcome these limitations, the addition of small molecule cross-linkers is explored to improve chitosan’s capability for healing.58 Particularly, in recent years, cross-linking of chitosan has become a popular trend allowing for not only the development of chitosan scaffolds with optimal properties but also the development of composite scaffolds through cross-linking with other materials (Table 1).

Table 1. Common Cross-linkers for Chitosan-Based Scaffolds in the Literature.

| Scaffolds | Method of Cross-linking | Cross-linkers Used | Influence of Cross-linking on Mechanical/Rheological Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan | Chemical cross-link – Covalent bonding | EDC/NHS64,65 | Increased Young’s modulus for chitosan scaffolds with vanillin (and bioglass) compared to chitosan scaffold.79 Increased resistance to compression for glutaraldehyde cross-linked scaffolds compared to uncross-linked scaffolds, concentration dependent increase in strength for the cross-linker.81 No significant difference in Young’s modulus with different genipin concentrations (0.25 and 0.5 M final concentration) under compression.500 Increased stiffness for cross-linked scaffold with genipin compared to chitosan scaffold73 |

| Genipin66−78 | |||

| Vanillin500,79 | |||

| Glutaraldehyde80−83 | |||

| Schiff base reaction84 | |||

| Hexamethylene-1,6-diaminocarboxysulfonate (HDACS)74 | |||

| Citric acid85 | |||

| Physical cross-link – Other bonding | Purines – Guanosine Diphosphate4,51,86−89 | Increased compressive modulus with increasing concentrations of TPP in scaffolds.93 Increased compressive strength with TPP cross-linking compared to uncross-linked scaffolds.94 Increased stiffness for cross-linked scaffold with pectin compared to chitosan scaffold73 | |

| β-Glycerophosphate84,90−92 | |||

| Tripoly phosphate (TPP)93−98 | |||

| Copper99 | |||

| Pectin73 | |||

| Chitosan-composite | Chemical cross-link – Covalent bonding | EDC/NHS100−102 | Increased elastic and loss Modulus with increasing DF-P1000 cross-linker concentration (Schiff Base and EDC dual cross-linking).100 Increased modulus and compressive strength with cross-linking using glutaraldehyde (increasing concentrations and soaking time).108 Increase in compressive strength for cross-linked scaffolds with glutaraldehyde alone or in combination with calcium cations. (110) Increased compression modulus with genipin cross-linking (also with graphene oxide addition).120 Increase in compressive strength with glyoxal cross-linking compared to uncross-linked scaffolds.106 Increased compressive strength with increasing concentration of inorganic phase (GPTMS)131 |

| Schiff base reaction100,103−105 | |||

| Glyoxal101,106,107 | |||

| Glutaraldehyde108−116 | |||

| Genipin112,117−129 | |||

| N′-Methylene bis(acrylamide)130 | |||

| 3-Glycidoxypropyl trimethoxysilane (GPTMS)131 | |||

| 2-Hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA)111 | |||

| Hexamethylene diisocyanate (HDI)132 | |||

| Physical cross-link – Other bonding | Tripoly phosphate (TPP)101,133−135 | Decreasing compressive strength with lemon grass oil addition due to decreased H-bonding potential of HPMC.136 Increase in compressive strength with addition of calcium cations as cross-linker compared to uncross-linked scaffolds.110 Increased elastic modulus (G′) in scaffold with Mg2+ions and BMP due to increased cross-linking density.130 Increased compressive strength for DHT treated scaffolds compared to IR treated, glutaraldehyde, and HEMA cross-linked111 | |

| Hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose (HPMC)136,137 | |||

| Calcium cations110,113,138 | |||

| Mg2+ ions130 | |||

| Dehydrothermal (DHT) Treatment111 | |||

| Irradiation treatment111 | |||

| Cu2+ ions139 |

Various studies in the literature have examined the use of cross-linkers including genipin, glutaraldehyde, and sodium tripolyphosphate as means to ensure stability within the polymer network.48−51,63 The incorporation of these cross-linkers relies on physical or chemical means through bonding to the polymer’s functional groups either by covalent bonding or supramolecular interactions.58,60 With respect to chitosan, this bonding often implements its amine groups, which can form a bond to hydroxyl groups.46

As discussed previously, this cross-linking can be further improved in chitosan through modifications of the polymer backbone by methacrylate or substitution of carboxymethyl derivatives.130,140,141 While physical methods of cross-linking including UV or gamma irradiation treatments tend to allow for a reversible process in certain pH and temperature environments, the use of chemical treatments for cross-linking is more commonly found in regenerative medicine applications.59,62,63,142 Treatment with chemical reagents has been shown to result in a higher degree of cross-linking and formation of a permanent network rather than a reversible one.60,62

In the selection of a cross-linker for chitosan, many factors need to be considered including the intended use of the scaffold and the properties of the cross-linking agent itself. For tissue engineering applications, the cross-linking agent must not induce an immunogenic effect and should not affect cell and material interactions.58−60 Within the chemical domain, glutaraldehyde and genipin are the most used cross-linkers for chitosan-based scaffold applications since their beneficial abilities have been well-documented in the literature.63 However, the toxicity of the functional aldehyde group of glutaraldehyde has resulted in its limited usage in commercial products.58,60 Conversely, genipin has been shown to be less cytotoxic, as it stems from natural roots.58,60,63

3.1. Methodology for Material Property Studies of Chitosan-Based Scaffolds

Addition of a cross-linking agent to scaffolds is expected to have significant effects with regards to material properties including degradation rate, structural architecture, and mechanical properties. This notion thus requires further testing of non-cross-linked and cross-linked materials for comparison to attain a more thorough understanding of its effects (Table 2, Figure 3). Within recent literature, 91% of material property studies are shown to include some form of evaluation of structural architecture, 71% show an examination of mechanical properties, and 54% look at biodegradation mechanisms.

Table 2. Common Methodologies for Material Property Testing in Chitosan Cross-linked Scaffolds for Bone (N = 100).

| Material Properties | Incorporation in Property Studies (%) | Methodology | Method Usage in Specific Property (%) | Information Obtained |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical properties | 71% | Compression testing(64−70,72,73,75,76,79,81,91,93−95,97,98,101−103,105−111,114−117,120,129,131−137,140,141,143−160) | 87.3% | Compressive strength, Young’s modulus |

| Dynamic mechanical analyzer83,130,138,161−163 | 8.4% | Creep and recovery properties | ||

| Tensile testing130,164−166 | 5.6% | Tensile strength, Tensile strain | ||

| Nanoindentation testing65,85,119 | 4.2% | Nanomechanical properties | ||

| Atomic force microscopy79 | 1.4% | Young’s modulus of hydrated samples | ||

| Hardness testing97 | 1.4% | Hardness of material | ||

| Flexural strength testing83 | 1.4% | Flexural strength | ||

| Rheological properties | 28% | Frequency sweep(66,69,86,89,92,100,103,104,112,123,130,134,144,147,149,158,167,168) | 64.3% | Storage modulus (G′) and Loss modulus (G′′) with angular frequency |

| Strain sweep92,104,105,118,121,123,125,126,128,168 | 35.7% | Storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G′′) with respect to strain | ||

| Time sweep92,100,112,130,158,162 | 21.4% | Determination of gelation | ||

| Structural architecture properties | 91% | Scanning electron microscopy(4,64−68,70−73,75,79−81,83,85,86,89−95,98,99,101,102,104−112,114−121,123,124,126,128−141,145−171) | 96.7% | Morphology and architecture of the scaffold, Pore size measurements with ImageJ |

| Liquid Displacement69,73,79,83,94,97,102,105,107,109−111,114−116,132,133,136,138,141,148−150,152−154 | 28.6% | Porosity and density measurement | ||

| MicroCT imaging68,87,89,95,120,124 | 7.7% | Porosity and interconnectivity | ||

| Mercury porosimeter65,70,75,126,129,158 | 6.6% | Porosity measurement | ||

| Physisorption analyzer117 | 1.1% | Measurement of specific surface area and pore structure | ||

| Atomic force microscopy65 | 1.1% | Surface structure | ||

| Stereomicroscope154 | 1.1% | Surface structure | ||

| Pycnometer93 | 1.1% | Bulk volume of scaffold to find porosity | ||

| Biodegradation properties | 54% | In solution (PBS, SBF, or water) with additives (lysozymes, muramidase, collagenase I, etc.)(64,69,70,72,73,75,85,89,105,111,119,121,124−126,129,130,136,138,140,141,149,155,158,159) | 46.3% | Percentage of degradation, Weight loss over time |

| In PBS(72,79,94,101,103,104,106,108−110,112,114,115,125,130−132,134,135,137,151,152,155,164,169) | 46.3% | Weight remaining ratio, Weight loss percentage | ||

| In simulated body fluid95,116,133,145 | 7.4% | Degradation weight | ||

| In culture media93,150 | 3.7% | Degradation rate | ||

| In water157 | 1.8% | Degradation percentage |

Figure 3.

Material properties to consider following cross-linking of chitosan scaffolds. Each property is presented with common methodology for testing found in the literature.

With respect to mechanical assessment, the most reported technique (87.3%) in the literature is found to be compression testing due to its ability to closely mimic the experience of bone in vivo. This is expected since it is thought to more accurately represent the material’s mechanical behavior when placed in the body.22 However, in addition to compressive modulus and strength, other parameters such as Young’s modulus, toughness, fatigue strength, and shear modulus of materials have also been reported in the literature but to a lesser extent.9,12,30,172 For derivation of these parameters, other methodologies are utilized including a mechanical tester for tensile properties, atomic force microscopy or nanoindentation for nanoindentation and stiffness, and a dynamic mechanical analyzer to measure the response of force versus displacement.

Further mechanical scaffold characterization has focused on examining the material’s viscoelastic properties under deformation using rheology. For chitosan-based scaffolds, literature studies often include either one or a combination of frequency,86,103,123,134,147,149,167 strain,98,100,112,130,151 or time sweep98,104,105,121,126,128,168 tests, which all provide complementary information about the material’s mechanical properties. However, recent literature has shown a popularity in using frequency sweeps especially since they can provide information such as the elastic and loss modulus with respect to angular frequency. These particular sweeps are performed 64.3% of the time in recent studies, whereas strain sweeps and time sweeps are performed 35.7% and 21.4% of the time, respectively.

With respect to assessment of scaffold morphology and architecture changes, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) is considered as the most popular method with a percentage of usage around 96.4% in recent publications of the field. This technique is so popular as it allows researchers to determine the pore size, interconnectivity, and distribution as well as the distribution of any other added materials within the scaffold. Furthermore, researchers can also use this technique to observe and image the surface morphology of the designed material. Other techniques including liquid displacement (28.6%), Micro CT (7.7%), or porosimeter usage (6.6%) have also been explored in the literature to a lesser extent, either alone or in conjunction with SEM, to determine the percentage of porosity and density. Assessment of biodegradation rate in the literature generally encompasses weight measurements at multiple time points after incubation of scaffolds in either PBS alone, with enzyme solutions, or in media. In the scope of chitosan-based scaffolds, the effect of cross-linker incorporation is beneficial to optimize and increase native material properties for bone related application.

3.2. Influence of Chitosan Cross-linking on Mechanical Properties

The protectoral function of bones in the body necessitates the consideration of mechanical properties of the material in the design of biological substitutes, that will provide sufficient mechanical support and integrity throughout the entire repair process.22,23 This explains why the mechanical environment is considered as one of the essential branches of the diamond concept on its own. Insufficiencies in mechanical strength have been demonstrated to be detrimental to the functionality of encapsulated cells rendering healing unsuccessful.22,173 For instance, variations in stiffness result in the differentiation of cells into other lineages, since cells can sense mechanical changes to their microenvironment through mechanosensation and respond accordingly.22,173 Increased mechanical properties and stiffness of chitosan-based materials with cross-linking can favor the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells into the osteogenic lineage compared to others since osteogenic cells favor stiffer substrates.24

Design criteria often suggest that a material’s mechanical properties should be similar to those of the native bone tissue, which tend to vary based on the type of bone.22,23 The compressive strength and Young’s modulus of healthy human cortical bone has been illustrated in the literature to be between 130 to 200 MPa and 7 to 30 GPa, respectively, whereas trabecular bone values are reported to be between 0.1 to 16 MPa and 0.05 to 0.5 GPa.174 Mechanical properties of a material tend to vary in response to a variety of factors. Changes in structural items such as the incorporation of other polymeric components,64,70,105,117,154,155 cross-linkers,69,75,81,93,94,97,101,106,110,111,117,131,135,152 and additives64,66,69,81,94,103,105,106,115,120,121,131−133,136,138,143,148,151 can have dramatic effects on the mechanical properties of the chitosan-based biomaterial substitute.175 However, comparison between studies is often difficult since chitosan can be used with different modifications, molecular weights, and degree of deacetylations.22

The incorporation of a cross-linker as previously mentioned is used with the intention of improving the mechanical properties of chitosan scaffolds. Improved compressive strengths and young’s modulus values compared to uncross linked scaffolds have regularly been demonstrated in the literature.94,97 A study by Pinto et al. showed that the addition of glutaraldehyde in increasing concentrations to a chitosan scaffold, produced increasing Young’s modulus values from 0.27 MPa with 0% to 1.7 MPa in 10% resulting in a more rigid and stable structure.81 Since many different cross-linking methods exist, some authors have chosen to compare the effects of multiple cross-linkers on the mechanical properties to determine which methodology is most efficient. Karakecili et al. evaluated different cross-linkers including EDAC/NHS, tripolyphosphate, and glyoxal in chitosan and collagen type I composite scaffolds, with results indicating a significant effect of cross-linking method on mechanical strength.101 The glyoxal cross-linking showed the highest percentage of increase for the compression modulus, whereas EDAC/NHS was found to have the lowest values of the three cross-linkers. Interestingly, significant differences between cross-linkers are not always observed within the literature. A study comparing tripolyphosphate and genipin cross-linkers in a chitosan and nano beta-tricalcium phosphate scaffold suggested a bimodal trend in concentrations with no significant differences between the cross-linkers.75 Demonstration of both these cross-linker modality effects indicates the necessity of significant testing for optimal composition when designing scaffolds prior to exploration of in vitro and in vivo osteogenic potential of materials.

In addition to the influence of cross-linking, some studies of composite chitosan cross-linked scaffolds have also examined the effect of different polymeric ratios within the scaffold. Nair et al. tested for compressive strength differences between chitosan and collagen scaffolds at varying ratios (75/25, 50/50, and 25/75) before and after cross-linking with glyoxal (Figure 4A,B). Results demonstrated that as the concentration of chitosan decreased, the compressive strength of the material also decreased (with cross-linking: CH–CO 75/25:19.3 kPa to CH–CO 25/75:9.3 kPa).106 This is promising as it suggests the possible benefit of chitosan for mechanical properties compared to collagen. Another study was also able to support this possible benefit, but this time examining changes in concentration of N,O-carboxymethyl chitosan with aldehyde containing hyaluronate acid in a scaffold cross-linked through Schiff base reactions.105 Increasing the concentration of N,O-carboxymethyl chitosan in the scaffold resulted in a significant increase in compressive modulus from 4.35 kPa with 4% to 20.99 kPa in 8%.

Figure 4.

Influence of scaffold design changes on the mechanical properties. (A) Compressive strength measurements of chitosan and collagen composite scaffolds at different ratios (75:25, 50:50, 25:75) prior to cross-linking. (B) Measurements of the same composite scaffolds after cross-linking with glyoxal. Both A and B were reproduced with permission from ref (106). Copyright 2021 Royal Society of Chemistry and the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique. (C) Elastic modulus and compressive strength of gelatin chitosan composite scaffolds with increasing concentrations of bioglass (0 to 30%). C was reproduced and adapted under open access conditions (Creative Commons Attribution License) from ref (115). Copyright 2016 Kanchan Maji et al. and Hindawi.

As the addition of compounds and mediators have been widely studied to improve the material and osteogenic properties of scaffolds, the influence of these additions on mechanical properties must also be considered. Some additives are included for the purpose of improving mechanical properties while others are not expected to have a significant effect. One of the main methods for improving the mechanical strength is the incorporation of hydroxyapatite or the induction of scaffold mineralization . A study by Lu et al. examined compressive stress values of mineralized and nonmineralized N,O-carboxymethyl chitosan scaffolds with cross-linking through amidation reactions using EDC/NHS.141 The mineralization of the scaffold presented a marked increase in ultimate compressive stress from 19.5 to 91.6 kPa. This effect was expected, as n-HA is known for its reinforcing ability. Fucoidan was also examined in this study as a potential drug delivery vehicle, but authors suggest that its addition could improve the ability of the scaffold to mineralize as well. Fucoidan incorporated scaffolds showed increased nonmineralized and mineralized values of compressive stress compared to pure N,O-carboxymethyl chitosan scaffolds alone. Another study demonstrated that through the addition of increasing concentrations of bioactive glass (0, 10, 20, 30 wt %) in chitosan and gelatin scaffolds, the compressive strength and elastic modulus were able to increase (Figure 4C).115 However, not all additives have been shown to have a beneficial effect. An example of this is the addition of lemongrass oil, which was found to produce a decrease in compressive strength with increasing concentrations.136 This undesirable effect was explained to be due to a disruption in cross-linking of hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose and chitosan with this addition.

These results therefore suggest extensive testing for additive effects in scaffold design studies. It is important to note that an intimate relationship exists between mechanical properties and multiple other material parameters, including the structural architecture. Incorporation of higher porosity and larger pores, which are often necessary for cellular functionality and vascular network infiltration, often are a result of decreased cross-linking and thus the materials present decreased mechanical strength.173 Therefore, a balance must be struck between the architectural design and the corresponding scaffold mechanical properties.

3.3. Influence of Chitosan Cross-linking on Rheological Properties

Strain sweep tests are often conducted as a preliminary step to frequency sweeps to determine in what amplitude range the material exhibits viscoelastic properties by applying a strain signal with increasing amplitudes. The frequency sweep test is often performed over a range of frequencies (0.01 to 100 Hz) with a constant strain to attain important parameter values including the shear elastic modulus (G′), loss/viscous modulus (G′′) and loss tangent (tan(δ)) values. Together, these values give further insight to the stability of cross-linked scaffolds. A study by Dessi et al. used frequency sweep testing to demonstrate the deformation behavior of Beta tricalcium phosphate (1 and 1.5%) and chitosan cross-linked composite scaffolds.98 Since the G′ elastic modulus was higher than the loss modulus G′′ throughout the frequency range, authors were able to conclude that the behavior was primarily elastic indicating a stable structure. Interestingly, no significant difference was observed due to concentration changes, but this conclusion should be further examined through comparison to a scaffold without beta tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP). While the loss tangent values were below one for this study, confirming the materials viscoelasticity, the elastic modulus values (at 1 Hz: G′ of 55 Pa for β-TCP 1% and 75 Pa for β-TCP 1.5%) seem relatively low compared to the use of other cross-linkers and additives reported in the literature. Another study examining scaffolds of chitosan-cysteine conjugates with difunctionalized PEG cross-linkers demonstrated a range of elastic modulus values between 962.5 to 1561.8 Pa with increasing weight to volume percentages of chitosan-cysteine solutions from 1.5 to 2.5% (Figure 5A).100 Results presented in this study suggest a beneficial effect of increasing concentrations of chitosan-cysteine solutions as well as an increased concentration of difunctionalized PEG cross-linkers (0.3 to 0.6 w/v %). The large difference (one to 2 orders of magnitude) between G′ and G′′ was observed as well, indicating again the stability of the scaffold. The null effect of pyrophosphatase addition to a chitosan-based guanosine diphosphate cross-linked scaffold on its rheological properties has recently been demonstrated using this methodology.86

Figure 5.

Rheological property evaluation. (A) Effect of increasing chitosan-cysteine (CH–CY) solutions (1.5 to 2.5%) and difunctionalized PEG cross-linkers (0.3 to 0.6 w/v %) on G′ and G′′ values. Reproduced and adapted under open access conditions (Creative Commons Attribution License) from ref (100). Copyright 2022 Qing Min et al. and MDPI. (B) Percentages of published articles for inclusion of mechanical properties, rheological properties, both, and none.

Time sweeps can also be beneficial in providing knowledge about the elastic modulus as a function of time. This particular technique has been well implemented in the literature as means to determine gelation time measurements. For example, An et al. were able to tune the gelation time of a methyl acrylate chitosan and aldehyde containing oxidized hyaluronate acid using this technique.104 The gelation time was determined as the time point where G′ and G′′ crossed over, as an indication of the transition from a liquid to a solid (more elastic) scaffold. Other authors have used this method to establish the elastic modulus changes throughout different time periods after cross-linking.128 From reviewing the literature for chitosan-based cross-linked scaffolds in the last ten years, it is evident that rheological properties of materials have been less explored compared to mechanical and compressive studies (Figure 5B). The viscoelasticity of a material is however an important consideration as it also affects the osteogenic differentiation of cells and their spreading behavior.24 Rapid relaxation of the scaffold following an applied stress encourages differentiation of the mesenchymal stem cells.24 Therefore, although it is more common to find studies that examine both recently, this combination of studies should be a set standard in implementation of Diamond Concept in bone repair, as it allows for a more concrete understanding of the material and possible interactions with body environment and cells.

3.4. Influence of Chitosan Cross-linking on Structural Architecture

The microarchitecture of scaffolds plays a vital role in supporting various functions. Careful consideration is needed when developing scaffolds to achieve the optimal structural architecture, depending on the intended therapeutic application. Bone is a highly porous structure; as such, porosity is an important parameter of a scaffold to better mimic the native tissue.176 An interconnected porous microstructure would favor higher cell infiltration and activity, vascularization, proper exchange of nutrients, and diffusion of therapeutic agents.17,31

In general, chitosan-based scaffolds demonstrate excellent porosity, with a commonly reported range of 80–90%.69,110 Moreover, pore diameter sizes tend to often be >100 μm, which is reported to be optimal for efficacious tissue infiltration and ingrowth.116 However, cross-linking in efforts to enhance the mechanical properties might be detrimental to the desired scaffold architecture, and thus, it is important to determine a right balance between polymer and cross-linker concentrations.

Genipin is among the most commonly used cross-linkers when fabricating chitosan-based scaffolds. While increasing the concentration of this cross-linker can slow down the degradation rate of the scaffold as a consequence of higher cross-linking, Dimida et al. observed no significant change neither in the structural architecture of the formed scaffolds nor in their mechanical properties (Figure 6A).72 Similarly, increasing concentrations of glutaraldehyde, another popular chitosan cross-linker, do not show a great effect on the general microarchitecture but did aid in enhancing the mechanical behavior of the scaffold. On the other hand, the compressive modulus of sodium tripolyphosphate cross-linked chitosan scaffold showed significant increase with higher cross-linking concentrations, but the porosity decreased to as low as 17.2%.93 Such results might suggest glutaraldehyde as an optimal cross-linker to combine improved mechanical strengths with maintained porous microstructure. However, increasing the concentrations of glutaraldehyde can risk an increase in cytotoxic effects. Therefore, more focus should be placed on finding a suitable cross-linker that supports all necessary properties relevant to the Diamond Concept.

Figure 6.

Characterization of structural architecture for various modifications of chitosan scaffold. (A) SEM images of chitosan scaffolds with increasing concentrations of genipin (left −3.75%, right −7.5%). Reproduced and adapted under open access conditions (Creative Commons Attribution License) from ref (72). Copyright 2017 Simona Dimida et al. and Hindawi. (B) Total porosity measurements (T.Po), structure thickness (St.Th), and specific surface (Sp.S) for chitosan scaffolds with increasing graphene oxide (GO) percentages (0, 0.5, 3%). Reproduced and adapted under open access conditions (Creative Commons Attribution License) from ref (177). Copyright 2019 Sorina Dinescu et al. and MDPI. (C) Percentage of porosity for sodium alginate and chitosan composite scaffolds with and without the addition of collagen and graphene oxide using liquid displacement method. Reproduced and adapted with permission from ref (138). Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society.

To complement cross-linking with the enhancement of mechanical and osteogenic properties of a scaffold, the addition of apatites and other ceramics is commonly employed. Hydroxyapatite (HA) is one such frequent additive to chitosan-based cross-linked scaffolds.71,88,95,166 As a major constituent of natural bone, HA not only increases the mechanical strength of scaffolds but also their biocompatibility and bioactivity.101

This, however, can often be accompanied by changes to the overall porosity or pore size.65,152 Compared to the control scaffold with only tripolyphosphate (TPP) cross-linking, Shemshad et al. observed a decrease in pore size following incorporation of nanohydroxyapatite along with bioactive silicate diopside. Nonetheless, the size remained within the range of 40 to 250 μm often recommended for bone tissue engineering applications. The incorporation of these factors did also yield a rougher pore morphology, which can be advantageous for better cell and tissue adhesion.94 β-TCP is another ceramic that can be added to confer to scaffolds similar properties as HA does. However, Jahan et al. observed that β-TCP had a larger particle size compared to HA, resulting in more occluded scaffold pores, thereby decreasing their size.51

To enhance the overall morphology of chitosan-based scaffolds, the addition of graphene oxide (GO) as an additive was attempted. This carbon-based material can aid in cross-linking different polymer chains together or polymers and other biomolecules, as well as increasing the mechanical properties of a scaffold and its biocompatibility, osteogenic properties, and in some instances, the total porosity of chitosan scaffolds.138 Dinescu et al. reported enhanced porosity with the addition of 3% wt. GO in a freeze-dried chitosan scaffold. They also observed that the addition of GO favored the formation of larger pores (Figure 6B).177 In other instances where chemical cross-linking was completed, the addition of GO slightly decreased the pore size of an alginate–chitosan–collagen composite scaffold chemically cross-linked with Ca2+ (Figure 6C).138 Nonetheless, addition of GO commonly yields a more homogeneous architecture with more defined pores, thick pore walls, and rougher morphology all which beneficially influence cell attachment and osteogenic differentiation and improve the overall efficacy of the scaffold for bone tissue engineering.80,120,178

3.5. Influence of Chitosan Cross-linking on Degradation Rate

Since one of the expectations of bone healing in defects is the regeneration of bone tissue over the course of time, the biodegradability of the material is an important consideration of scaffold design. When the scaffold is placed in vivo, it is expected that its degradation rate will match that of the native bone tissue ingrowth thus allowing the gradual transfer of mechanical load.12,25−30 The scaffold’s role is to act as a temporary bridge between both ends of the defect helping cells, as well as acting as a platform to create an optimal microenvironment.25 Degradation rates that are too fast or too slow result in inadequate healing and lead to insufficiencies in mechanical support throughout the healing process.27

Due to the necessity for control, assessment of this property has become a standard practice in material design and characterization, including the design of chitosan-based scaffolds.28 Within the body, degradation of polymers typically occurs through a chain scission process of the polymer induced by enzymes such as lysozymes, which results in the hydrolysis of chitosan and the cleavage of its β-(1–4)-glycosidic bonds.26,51 A study by Kim et al. demonstrated this concept through the incorporation of varying concentrations of lysozymes in a methacrylated glycol chitosan hydrogel.140 Increases in lysozyme concentration from 0.1 to 10 mg/mL resulted in accelerated degradation rates of the hydrogel with a final degradation of around 30% left after 14 days when a lysozyme concentration of 10 mg/mL was used.

Work within the literature on chitosan cross-linked scaffolds has often embraced the lysozyme technique to study in vitro degradation behavior.69,70,72,73,129,138,140 Formation of a composite chitosan and polycaprolactone (PCL) scaffold with genipin cross-linking showed decreased degradation rates compared to chitosan alone cross-linked control groups (Figure 7A).119 The dependence of the chitosan amount on the degradation rate was not surprising since the lysozyme is expected to target the chitosan specifically. Another study by Rahman et al. further demonstrated chemical cross-linking’s influence on biodegradation rates and stability using a chitosan/hydroxyapatite/collagen composite scaffold.111 This scaffold was cross-linked with either glutaraldehyde (GTA), dehydrothermal treatment (DTH), irradiation (IR) or 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA), resulting in Ha·Col1·Cs-GTA, Ha·Col1·Cs-IR, Ha·Col1·Cs-DTH, and Ha·Col1·Cs-HEMA composites. Results indicated that the glutaraldehyde cross-linked scaffold exhibited a 16% degradation on day 21, whereas the scaffold without the cross-linker was 55% degraded at this same time point (Figure 7B). Interestingly, this improvement in degradation rate using cross-linkers was not shown when adding a fibrin coating to a chitosan scaffold.70

Figure 7.

Degradation profiles of composite chitosan scaffolds in lysozyme. (A) Chitosan (CS) and polycaprolactone (PCL) scaffolds with different concentrations of polymers (100:0, 20:80, 40:60, 0:100) cross-linked with genipin. Reproduced and adapted with permission from ref (119). Copyright 2022 Elsevier. (B) Chitosan/hydroxyapatite/collagen composite (Ha-Col1-CS) scaffolds before and after cross-linking with different methodologies: (1) DHT – dehydro-thermal treatment, (2) IR – irradiation, (3) GTA – glutaraldehyde, and (4) HEMA – 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate. Reproduced and adapted under open access conditions (Creative Commons Attribution License) from ref (111). Copyright 2019 Md. Shaifur Rahman et al. and Springer.

Since composite scaffolds are often formed with chitosan and other polymers such as collagen, the biodegradation of scaffolds in collagenase solution is also sometimes assessed in the literature.107,121,125,126 Grabska-Zielinska et al. examined the degradation profile of a chitosan and fish gelatin scaffold with genipin cross-linking and the benefits of graphene oxide incorporation. Interestingly, when cultured in collagenase 2 solution, the scaffold without graphene oxide mostly degraded (72%) within the first 24 h. However, the addition of graphene oxide in doses above 1 wt % was able to withstand some of this degradation showing percentage values around 44% to 52% depending on concentration.107 Similarly, the addition of amino group functionalized silica particles with alendronate served to slow down the degradation process of chitosan scaffolds with collagen and hyaluronic acid.121 However, the beneficial effects of biodegradation mediators should be further explored for better understanding of mediator-mediated biodegradation.

In addition to the importance of the biodegradation profile itself, the byproducts of this degradation must also be considered in aspects of design. These should be nontoxic and nonteratogenic and do not elicit any undesirable immunogenic response when degradation occurs.12,20,25,27,29,179 Often, byproducts can be beneficial in the development of an adequate microenvironment for healing and can improve bioactivity within the defect site.25,51

4. Cell Encapsulation in Chitosan Cross-linked Scaffolds

In addition to modifications of the scaffold material itself, the Diamond Concept also stresses the necessity of an encapsulated viable cell population. Incorporation of cells is important in successful bone regenerative therapies since bone cells such as osteoblasts, osteoclasts, and osteocytes are responsible for the production, remodeling, and maintenance of bone.180 Previous studies with empty scaffolds have shown almost no cellular ingrowth from the native tissue, which negatively affects the regenerative ability.181 With relevant cell encapsulation, both osteogenic differentiation of the cells and angiogenesis are encouraged when present at the target site, thereby resulting in the secretion of varying growth factors, matrix proteins and cytokines such as vascular endothelial growth factor and interleukin 6.32,33,179,182 Culmination of these secretion activities with successful cellular differentiation can improve the healing outcomes.

4.1. Methodology for Cellular In Vitro Studies in Chitosan Scaffolds

The first step in designing an encapsulated cell-based substitute is to examine the material’s ability to support cellular activity. While cross-linking of chitosan-based scaffolds can result in improved mechanical properties which is beneficial in supporting loading, it can be accompanied by a decrease in porosity and pore size. Since the functionality of cells once encapsulated is known to be heavily dependent on their access to nutrients and oxygen, such significant changes to the internal structure with cross-linking can lead to drastic changes in cellular viability and activity.

Another important consideration is the effect of the method of cross-linking itself on cellular viability and functionality. Some cross-linking techniques, like physical cross-linking, can have low cytotoxicity to cells however, they might require harsh conditions such as changes in temperature or pH and do not always provide the optimal material properties necessary for bone applications.58,183 On the other hand, chemical cross-linking might be more beneficial with respect to material properties due to stronger bonding but can have higher costs and higher risk of cytotoxicity, especially with cross-linkers such as glutaraldehyde.58 Genipin cross-linking, which is commonly used as a cross-linker for chitosan-based materials, is known to be biocompatible and less cytotoxic than other chemical cross-linkers.58

With all the considerations of cross-linker effects on cellular activity, this addition necessitates a thorough evaluation of cellular functionality in chitosan-based scaffolds. For bone applications, the in vitro assessment of cellular activity is thought to be further divided into three subgroups, namely biocompatibility, osteogenic differentiation, and mineralization (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Common methodologies for in vitro studies using cell cultures in the literature. These steps include testing for biocompatibility, osteogenic differentiation, and biomineralization.

The initial aspect of this often encompasses a quantification of cellular proliferation and metabolic activity using commercial assays such as MTT/XTT/MTS (41.9%), alamarBlue (21.5%), or Cell Counting Kits (18.3%). While these listed tend to be the most popular in terms of quantitative assays, many other techniques encompassing a visual assessment component have also been demonstrated in the literature. For example, around 33.3% of recent articles have examined cellular distribution and morphology through staining using antibodies for phalloidin and nucleic acid. Another common staining found in the literature is Live/Dead or calcein based assays, which stain live and dead cells different colors making it easy to quantify cytotoxicity and overall percentage of viability.

Furthermore, in many studies SEM is used to visually determine cell adhesion properties on the surface of the scaffold. All these methods for biocompatibility provide researchers with a more thorough understanding of whether their material can support generic cellular activities without significant adverse effects. However, not all these methods will provide the same information and therefore it is crucial to understand the differences between testing methods. Table 3 is presented to help differentiate these differences and serve as a resource for experiment planning in future studies.

Table 3. Common Methodologies for In Vitro Testing in Chitosan Cross-linked Scaffolds for Bone (N = 94).

| In Vitro Experiments | Incorporation in In Vitro Studies (%) | Information Obtained | Methodology | Usage in Specific In Vitro (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellular Biocompatibility | 98.9% | Cellular Metabolic Activity, Growth and Proliferation | MTT/XTT/MTS Assay(69,70,72,75,79,90,93−95,98,105,106,108,110,115,116,123,124,128−132,135,137,138,141,148−150,152−155,157−159,170,171) | 41.9% |

| IF Staining – DAPI with or without Phalloidin65,66,70,74−77,79,81,85−89,98,104,106,112,119,123,129,130,137,139,144,151,152,161,166,168,169 | 33.3% | |||

| Alamar Blue Assay72,76,81,86,87,89,92,107,118,121,125−127,134,136,140,143,144,152,164,170 | 21.5% | |||

| Cellular Counting Kits64,65,71,74,100,103,104,114,117,119,133,139,147,151,163,166,169 | 18.3% | |||

| PrestoBlue Kit101,109,112 | 3.2% | |||

| EdU and BrdU Staining161,184 | 2.2% | |||

| Resazurin Assay68,102 | 2.2% | |||

| IF Staining – Ki6765,119 | 2.2% | |||

| Cellular Cytotoxicity and Counting of Viable Cell Numbers | Live Dead Assay/Calcein AM Staining(64−66,75,87,89,95,100,104,105,117,123,124,137,138,140,147,150,159,160,163,167−169) | 25.8% | ||

| Lactic Dehydrogenase Assay124,156,169 | 3.2% | |||

| Trypan Blue Staining93,165 | 2.2% | |||

| FDA Staining71,93 | 2.2% | |||

| Acridine orange/Ethidium bromide staining151 | 1.1% | |||

| Flow Cytometry – Annexin V,64 Propidium Iodide64 | 1.1% | |||

| DNA Content | PicoGreen total DNA Assay(4,70,73,75,101,123,162,170) | 8.6% | ||

| Cellular Biocompatibility, Morphology and Adhesion | Scanning Electron Microscopy(64−66,70,73−75,77,81,85,87,88,94,98,101,103,108,115,117,121,125−127,131,132,137,139,150,152,157,166,169,170) | 35.5% | ||

| Light Microscopy90,157,165,171 | 5.4% | |||

| HE Staining73 | 1.1% | |||

| Osteogenic Differentiation | 63.8% | Osteoblast Differentiation Specific Protein Secretion | Alkaline Phosphatase Testing(4,64−66,69−71,73,75−77,79,81,85,86,88,89,93,94,98,100,101,108,109,114,118,119,121,123,125−127,130,131,133,135,137,139−141,144,151,155−157,159,161,163,169,170) | 84.7% |

| ELISA - Osteocalcin,71,85,163 Type 1 Collagen,100 Osteopontin163 | 5.1% | |||

| Sirius Red Dye Assay112/SirCol Collagen Assay73 | 3.4% | |||

| Osteoblast Differentiation Related Activity Stainings | IHC, ICC, IF Staining for different markers – RUNX2,64,115,120OPN,120BSP,64OCN,86,115,184OSX88 | 11.9% | ||

| Gene Expression of Osteoblast Related Genes | qPCR – ALP,64,65,70,74,81,89,112,129,130,144,147,166,169BSP,64,65,70,79,129COL1A1,64,70,81,101,119,123,127,130,139,140,144,151,157,169OCN,64,65,77,79,81,101,108,119,123,127,130,139,140,144,157RUNX2,64,77,79,81,89,101,108,112,120,127,139,140,144,147,151,157,162,169OPN,65,77,81,101,119,120,123,129,130BMPs,81,151ON,70OSX65 | 44.1% | ||

| Protein Expression of Osteoblast Related Genes | Western Blot – Col1A1,64,119,130RUNX2,64,130ALP,130OPN,64,65,119,130BSP,64,65OSX,64OCN,64,65,70,119ECM Proteins,119B-Catenin,130Smad1,130p-smad1/5/8,130cell growth factors119 | 6.8% | ||

| Mineralization | 36.2% | Quantification of Mineral and Calcium Deposition | Alizarin Red Staining(4,64−66,69,70,86,98,101,104,106,111,114,119,120,123,130,138,140,141,143,147,151,155,156,159,161) | 45.8% |

| Von Kossa Staining73,88,106,144,184 | 8.5% | |||

| Total Calcium Kit70,75,79,156 | 6.8% | |||

| O-Cresol phthalein complexone method73,109 | 3.4% |

In addition to simply testing biocompatibility, the ability of a material to support osteogenic differentiation is another important consideration to address since the target application in many of these studies is bone regeneration. Around 63.8% of relevant literature have included this aspect into their In vitro studies, with the most common technique for studying this being the detection of an early osteogenic marker, alkaline phosphatase (84.7%). Bone ALP is known to regulate the mineralization process since it provides a phosphate reservoir to the matrix through hydrolysis of the mineralization inhibitor, pyrophosphate. Thus, it is arguably a necessary methodology with regards to claiming successful differentiation potential. This assay is sometimes complemented with other techniques such as qPCR, which serves to assess gene expression of other early and late-stage markers in a comprehensive manner.

With respect to mineralization of the material, this is often the least considered and evaluated aspect of in vitro studies, present in only around 36.2% of publications. The most common techniques for this involve mineral staining using either Alizarin Red or Von Kossa but a few studies have also shown promising results using quantitative calcium assays.

4.2. Cell Sources for Bone Tissue Engineering in Chitosan Scaffolds

A variety of factors need to be considered in the decision of cell source including aspects such as the ease of availability for harvesting, low morbidity of donor site, high efficiency of isolation, adequate cell proliferative ability, and sufficient osteogenic differentiation potential. While many different options for cell sources are currently being explored in chitosan-based cross-linked scaffolds for bone tissue engineering, the focus remains on finding a reliable cell source that will meet many of the criteria listed above. Currently, these consist of either osteogenic cells that are already lineage committed or stem cells, which allow for control of differentiation (Table 4).

Table 4. Common Cell Lineages and Lines Presented in the Literature for Chitosan-Based Scaffolds.

| Category | Cells in Literature | Scaffold |

|---|---|---|

| Lineage committed | MC3T3 preosteoblast cells (murine) | Chitosan4,79,87,88,137 |

| Chitosan/gelatin101,109,112,120,124 | ||

| Chitosan/collagen135 | ||

| Chitosan/collagen/alginate138 | ||

| Chitosan-cysteine conjugate100 | ||

| Methacrylic anhydride modified chitosan169 | ||

| Methacrylic anhydride modified chitosan/poly(acrylamide)130 | ||

| Carboxymethyl chitosan/alginate139 | ||

| Chitosan/hyaluronic acid129 | ||

| 7F2 osteoblast cells (murine) | Chitosan73 | |

| Carboxymethyl chitosan/fucoidan141 | ||

| MG-63 osteoblast like cells from osteosarcoma (murine) | Chitosan81,93,94,98 | |

| Chitosan/collagen/hyaluronic acid118,121,125,126 | ||

| Chitosan/gelatin143 | ||

| Chitosan/polyvinyl alcohol131 | ||

| Chitosan/polycaprolactone170 | ||

| Stem cells | Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) – attained from multiple sources | Chitosan66,75−77,85,86,156 |

| Chitosan/gelatin115,133,147 | ||

| Chitosan/agarose/gelatin114 | ||

| Chitosan/collagen111,127 | ||

| Thiolated chitosan/gelatin151 | ||

| Carboxymethyl chitosan64,65,71 | ||

| Chitosan/gelatin108 | ||

| Methylacrylylated chitosan/hyaluronic acid104 | ||

| Chitosan/polycaprolactone119 | ||

| Fatty acid modified chitosan/decellularized bone ECM123 | ||

| Methacrylated glycol chitosan140 | ||

| Chitosan/fibrin70 | ||

| Others | C2C12 myoblasts (murine) | Chitosan/alginate161 |

| Chitosan/lactide155 |

4.2.1. Osteogenic Lineage Committed Cells in Chitosan Scaffolds

The first category often discussed when addressing this challenge is osteogenic cells such as osteo-progenitor cells, osteoblasts, and osteocytes.30,33 Although these cells are still derived from mesenchymal cells, their previous commitment to the osteogenic lineage allows them to begin secreting bone matrix components almost immediately upon implantation.33,34 Thus, osteogenic markers such as type 1 collagen and alkaline phosphatase are expected to be present sooner into the regenerative process, therefore improving the rate of bone healing.33 In recent years, the MC3T3 preosteoblastic cell line has become a standard model regarding lineage committed cells for applications in bone tissue engineering.185,186 In many studies with chitosan-based cross-linked scaffolds, these cells have thus been included for evaluation of osteogenic differentiation and mineralization potential in the materials. For example, in a genipin cross-linked chitosan-gelatin scaffold with GO incorporated, Selaru et al. were able to use MC3T3 cells to demonstrate enhanced osteogenic differentiation and mineral deposition compared to scaffolds without GO.120 Similarly, Karakeçili et al. observed enhanced MC3T3 mineralization aided by the addition of n-HA.101 While these committed lineage cells provide many benefits in the healing cascade, they are often time-consuming with regard to the culturing process and their potential for expansion is limited in vitro.30 Furthermore, collection and harvesting processes for primary cells are invasive by nature, therefore encouraging scientists to commonly look at alternatives for cell types such as the incorporation of stem cells.33

Another common category of cells for various in vitro osteogenic models includes osteosarcomas such as MG-63 and Saos-2. These cell lines are derived from bone tumors and can display similar properties as osteogenic cells like alkaline phosphatase (ALP) production and mineral deposition.187 Osteosarcomas have been widely used to investigate the osteogenic suitability of a various range of chitosan-based cross-linked scaffolds.92,95,128,132,152,154,164 In the study by Shemshad et al., osteogenic differentiation of MG-63 cells seeded on a TPP cross-linked chitosan scaffold with addition of hydroxyapatite and bioactive silicate diopside is reported.94 By adding the osteogenic factor strontium to their scaffold, Rodríguez-Méndez et al. observed increased ALP activity of MG-63 cells, whereas Pati et al. demonstrated the benefits of cross-linking with an increase in mineralization (Figure 9).98,170 However, while osteosarcomas can be useful in providing valuable information regarding biocompatibility and osteogenic potential in vitro, their clinical translatability is hindered by their tumoral nature. Therefore, it can be argued that these cells are not ideal within the scope of the Diamond Concept and an alternative source should be considered or tested simultaneously with these cells.

Figure 9.

Assessment of (A) osteoblastic differentiation (ALP activity) and (B) mineralization potential (Alizarin Red Staining) from MG-63 cells over 21 days for chitosan scaffolds with and without tripolyphosphate cross-linker. Reproduced and adapted with permission from ref (98). Copyright 2012 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

4.2.2. Stem Cells in Chitosan-Based Scaffolds

Stem cells present many advantages for use, since they have self-renewal capabilities and can easily be induced to differentiate into various lineages.179,188,189 Although this broad categorization encompasses several different types, adult mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are most extensively used in the literature for bone regeneration application as they are not associated with ethical or safety constraints.33,35 Adult MSCs can be isolated from tissues such as bone marrow and adipose, which are vascularized.30,179,182 They possess beneficial properties including multilineage potential for differentiation (adipogenic, chondrogenic, and osteogenic), high proliferative abilities, and immunomodulatory capabilities.179,180,182 Bone marrow derived stem cells are the frequent cell choice for bone tissue engineering applications and treatment of bone disease since they have demonstrated the highest potential for osteogenic differentiation and bone repair.41,181,182 These cells are harvested during bone marrow biopsies, often from the iliac crest, sternum, or proximal tibia, which all are rich in marrow and are induced for differentiation through exposure of cells to a high phosphate environment.181,182,190

Although bone marrow derived stem cells are commonly employed and have been extensively characterized, they only compose around 0.001 to 0.1% of cells present in the marrow, which make their isolation in large quantities very difficult.181 The cell number for isolation is dependent on various parameters including the donor’s age and associated donor site morbidity and their limited quantity is a significant disadvantage to their use.188

An alternative cell source for osteogenic applications includes adipose derived stem cells (ADSCs). These cells are attained from adipose tissue through minimally invasive surgical procedures such as liposuction.182,188,190 They can be retrieved in high abundance from harvesting, and their differentiation from fibroblast-like morphology makes them very interesting for rapid formation of connective tissue.42,181,182,188,191,192 However, their osteogenic ability has been questioned since some studies have shown lower capability for differentiation compared to bone marrow derived stem cells.33,188 Others have demonstrated that their differentiation potential is adequate and can be enhanced in this cell type through culture with osteogenic medium.181

5. Osteoinductive Mediators’ Encapsulation in Cross-linked Chitosan Scaffolds

The third major aspect in the design of biological substitutes for bone tissue regeneration involves the incorporation of bioactive molecules, drugs, and growth factors with osteoinductive properties. These components are responsible for influencing cellular functionality including the attraction of cells to the injured site, and stimulation of cells to undergo osteogenic differentiation in turn resulting in bone regeneration.193−196 While in cell cultures growth factors can be added to media, it is often more effective to encapsulate them in the scaffold or conjugate them to the polymer backbone through chemical modification.194,197 Within the scaffold, factors can be locally delivered to the injury site in a controlled release manner, allowing for the creation of a similar microenvironment to the natural healing cascade.193,198,199

Many studies have been conducted within the literature examining the application of different osteoinductive mediators with respect to cross-linked chitosan scaffolds including growth factors, mediators, enzymes, drugs, compounds, and nanoparticles (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Common osteoinductive mediators in the literature for chitosan-based cross-linked scaffolds.

5.1. Encapsulation of Growth Factors in Cross-linked Chitosan Scaffolds

Traditional growth factors, such as BMPs, have great potential in bone regeneration applications since they are known to have a physiological role in the fracture healing cascade.199 BMPs residing within the transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) family are one of the most popular osteogenic growth factors currently. These factors encourage bone formation through downstream events that occur due to receptor binding.193−195,199 BMPs 2 and 7 specifically are known to be responsible for bone regeneration and have been demonstrated in the literature for controlled delivery both alone and in conjunction with other mediators from chitosan-based scaffolds.64,77,114,129,130,161,169,193−195 A study by Nath et al. demonstrated the osteogenic effects of BMP2 incorporation into a chitosan and hyaluronic acid scaffold cross-linked with 3 mg of genipin. Results showed that MC3T3 preosteoblast cells in the scaffolds coencapsulated with BMP2 exhibited higher expression levels of early differentiation markers ALP and osteopontin (OPN) at day 7 compared to control groups, as well as significantly higher late-stage expression of OPN at day 28. While this study showed the benefits of coencapsulation, the osteogenic effect of sustained release of BMP2 was not considered for cells outside the scaffold.129 This missing aspect was however explored in the scope of a chitosan-agarose-gelatin scaffold with chitosan oligosaccharide/heparin nanoparticles. Through indirect culture of MSCs, Wang et al. demonstrated that the loading of BMP2 within the nanoparticles resulted in a sustained release over time leading to increased ALP activity and osteogenic induction throughout 21 days. These BMP2 loaded nanoparticles in the chitosan-agarose-gelatin scaffold showed significantly higher ALP levels compared to the nanoparticles or scaffold alone and demonstrated similar levels to the group with BMP2 alone at early time points. At later stages, this BMP2 loaded test group also exhibited more positive alizarin red calcium staining compared to the BMP2 alone control group.114 Interestingly, while BMPs are present in a variety of studies in the literature for chitosan-based scaffolds due to their demonstrated beneficial effects, other alternatives are considered due to their high cost and possible side effects.

5.2. Encapsulation of Bioactive Compounds in Cross-linked Chitosan Scaffolds

In addition to traditional growth factors, studies within the bone tissue engineering domain heavily rely on the incorporation of osteoinductive mediators such as bioceramics, namely HA51,65,69,71,76,81,83,88,93,94,101,103,111,136,141,145,146,152,164−166 and β-TCP.70,75,92,145 Both ceramics contain calcium and phosphate, which make up the main components of mineralized bone.9,200−203 Many studies have included HA within their designed chitosan-based scaffolds due to its biocompatibility with cells and its known bioactivity both in vitro and in vivo.204 Recent work has explored the combination of HA with other compounds for added promotion of osteogenic activities. Lu et al. incorporated n-HA with fucoidan into a hydroxypropyl chitosan scaffold cross-linked with genipin.69 While the incorporation of n-HA alone in these scaffolds resulted in a marked concentration-dependent increase in ALP activity for 7F2 osteoblasts compared to controls, the combination of n-HA with fucoidan produced an even higher ALP activity. The influence of HA incorporation either alone or in combination with fucoidan also showed increased calcium deposition in alizarin red staining, signifying its benefits in mineralization induction. Combination of HA and β-TCP in varying ratios has also been tested in chitosan-based scaffolds68 ,81 ,95 ,133 since this biphasic calcium phosphate composite is expected to have increased osteoconductivity to HA alone.

More recently, studies have focused on this criterial element by incorporating enzymes, natural compounds, and drugs in their chitosan-based scaffolds. A few studies used pyrophosphatase in combination with the purine cross-linker guanosine diphosphate to promote mineralization.4,86,88 Nayef et al. have shown that due to the enzymatic cleavage of the purine during the degradation process, a large quantity of pyrophosphate is found in the culture media.4 Incorporation of pyrophosphatase served to cleave observed pyrophosphates into phosphate ions allowing for an increased ratio of phosphate to pyrophosphate, thus producing mineralization at levels similar to those treated with direct BMP7 injection in MC3T3 cell cultures.4 Additional studies have expanded the pyrophosphatase encapsulation in conjunction with adipose derived stem cells86 in the chitosan scaffold and reported on its beneficial effect in vivo using mouse tibial defect models.88

The loading of bisphosphonate drugs such as Alendronate have also been explored for promoting osteogenic activity in chitosan cross-linked scaffolds.119,121 Alendronate has been shown to increase BMP2 expression, thereby stimulating osteogenic differentiation and mineralization. A recent study by Shi et al. examined these possible beneficial effects in a chitosan and polycaprolactone scaffold cross-linked with genipin.119 Through seeding of ectomesenchyme cells, they demonstrated increased osteogenic induction (ALP activity) and calcium deposition with Alendronate compared to the control scaffolds. Additionally, results showed an increased level of BMP2 proteins within this test group, which could suggest Alendronate as a possible lower-cost alternative to BMP2 growth factor. Since bisphosphonate drugs are often more commonly associated with their roles in osteoclast activity inhibition, their usage proves beneficial in diseases such as osteoporosis or Paget’s disease where additional bone turnover is observed.

Natural medicinal compounds derived from herbs and minerals have also been considered as an alternate option for promotion of osteogenic differentiation to mitigate high costs and long-lasting side effects.83,100,148 Two flavonoid compounds, Quercetin and Icariin, have been explored recently with encapsulation into chitosan-based cross-linked scaffolds as possible agents for promotion of bone regeneration and formation. Both compounds exhibit similar effects in bone metabolism to estrogen, thus inhibiting osteoclast differentiation and promoting osteoblast formation. A study by Min et al. showed a synergistic osteogenic effect of amino-functionalized mesoporous bioglass nanoparticles loaded with Quercetin in a chitosan cysteine conjugate composite (CH–CY) with difunctionalized PEG cross-linkers.100 Hydrogels with loaded nanoparticles exhibited increased ALP activity and Collagen I content at 14 days compared to CH–CY gels alone. The authors suggested that the synergistic effect was a result of both Si and Ca ions released due to nanoparticle degradation as well as quercetin release. While these encouraging results of natural compounds are outlined clearly in the literature, their tested incorporation in the scaffolds serves to design a drug delivery system whereby drug release can be carefully controlled. Often, loading of these compounds relies on the usage of nano or microparticles within the scaffold as can be seen in the previous example.

5.3. Inorganic Mediators Encapsulation in Micro- and Nanoparticles

Nanoparticle encapsulation in chitosan-based cross-linked scaffolds has incorporated the usage of mostly inorganic materials including silica,90,105,118,121,122,125,127 copper,139 zinc oxide,137,148 strontium,170 and titanium oxide.128 Silica is one of the components that make up bioactive glass, thus making its incorporation in studies popular. Unlike the previous compounds and additives, silica has been shown to promote apatite formation in cultures of simulated body fluid as well as osteogenic differentiation. Filipowska et al. demonstrates both effects using hBMSCs in a chitosan and collagen composite scaffold.127 In groups with silica particles, the mRNA expression levels of osteogenic related genes (RUNX2, COL-1, and osteocalcin) were significantly higher than the control group at day 14. Interestingly, results demonstrated a dependency of the mRNA expression on the size of the particles at this early stage where the smaller particles exhibited higher levels. In addition, SEM micrographs of both silica particle groups showed aggregation on the surface of the cell as a sign of mineralization and apatite formation compared to the smooth surface found in the control collagen and chitosan scaffold. EDS analysis for calcium and phosphorus on these surfaces illustrated silica’s effect on calcium and phosphate production. These two test groups had Ca/P ratios around 1.65, which is similar to that of native crystalline hydroxyapatite. Other inorganic materials listed above have also been tested within these scaffolds, however to a much lesser extent. Copper is one of these less explored elements but has been shown to promote bone formation in the literature. A study by Lu et al. demonstrated that the incorporation of copper nanoparticles in a carboxymethyl chitosan and alginate scaffold resulted in increased ALP activity at day 7, and increased COL-1 and osteocalcin mRNA expression at day 14.139 Interestingly, the copper nanoparticles were used in place of Cu2+ ions in this study to slow down the cross-linking process of the carboxymethyl chitosan and alginate scaffold. It has been shown that the Cu2+ ion alone can serve as a cross-linker, thus allowing the scaffold to cross-link slowly as ions are released.

5.4. Investigation of Release Kinetics of Encapsulated Compounds

Since one of the main challenges in the design of biological substitutes with mediators, growth factors, or drugs is the achievement of a sustained release profile, kinetic release studies are often conducted in vitro as part of scaffold characterization.22,205−207 To perform these tests, scaffolds are loaded with a model component and its concentration in the supernatant is measured over a certain amount of time (Figure 11, Table 5). The most common method to assess the release kinetics includes UV–vis spectrophotometry and absorbance readings, with half of the relevant articles having reported on this methodology. Other techniques like enzyme linked immunosorbent assays, HPLC, or protein assays can also be used. Ideally, the release of growth factors and mediators for osteogenic promotion needs to be sustained throughout the healing process. Thus, research incorporating compounds such as BMPs, bisphosphonates, or inorganic materials in chitosan scaffolds often tests this kinetics throughout a designated period. Some studies have examined a short duration of time up to 2 weeks,64,91,135,151,155 while others have examined release past 4 or 5 weeks4,96,130 enabling a more comprehensive understanding of the mediator’s possible effect over time.

Figure 11.

General mechanisms that mediate the release of factors from scaffolds and common methodologies used to assess this release.

Table 5. Common Methodologies for Encapsulation Efficiency and Release Kinetic Studies in Chitosan Cross-linked Scaffolds for Bone (N = 31).

| Growth Factor Properties | Incorporation in Growth Factor Studies (%) | Information Obtained | Methodology | Usage in Specific Property Category testing (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Encapsulation efficiency | 45.2% | Drug loading rate encapsulation efficiency | UV–vis/ spectrophotometer–absorbance readings(67,83,100,103,121) | 35.7% |

| ELISA4,96,114,167 | 28.6% | |||

| HPLC119 | 7.1% | |||

| Weight measurements of drug105 | 7.1% | |||

| Drug specific testing | BCA protein assay–used commonly for BSA loading(91,129) | 14.3% | ||

| Toluidine Blue staining (presence of heparin)(96,146) | 14.3% | |||

| Release kinetics | 96.7% | Release rate of drug percentage of drug released | UV–vis/ spectrophotometer–absorbance readings(65,68,73,83,87,100,103,105,119,121,132,147,153,157,161,169) | 50% |

| ELISA4,64,77,96,114,129,167 | 26.7% | |||

| Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry130,139 | 6.7% | |||

| Aluminum trichloride method158 | 3.3% | |||

| HPLC135 | 3.3% | |||

| Drug specific testing | BCA protein assay–used commonly for BSA loading(91,155,162) | 10% | ||

| Toluidine Blue Assay (concentration of Heparin)146 | 3.3% |

Osteogenic mediators and factors can be added to chitosan scaffolds mainly through covalent or noncovalent binding.208,209 The latter is more prominent in bone-oriented applications and involves the adsorption of the factors onto the scaffolds or their entrapment within the scaffold mesh.22,210 Electrostatic interactions, hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, or van der Waals forces play a major role in immobilizing factors noncovalently onto the scaffolds, and disruption of these interactions can influence the release kinetics.208,209 Generally, different mechanisms mediate the release of factors from scaffolds including desorption and diffusion of factors outside of the scaffold, swelling of the scaffold, or degradation of the scaffold’s structure, and they have been previously reviewed in a publication by Herdiana et al.211 In addition to the type of factor added, the release mechanism also depends on how the factor interacts with and is bound to the scaffold as well as the properties of the scaffold itself. Thus, changes in the composition of the scaffold can allow for the rate of release to be tuned and controlled more precisely.210