Abstract

Background

There are few medicines in clinical use for managing preterm labor or preventing spontaneous preterm birth from occurring. We previously developed two target product profiles (TPPs) for medicines to prevent spontaneous preterm birth and manage preterm labor. The objectives of this study were to 1) analyse the research and development pipeline of medicines for preterm birth and 2) compare these medicines to target product profiles for spontaneous preterm birth to identify the most promising candidates.

Methods

Adis Insight, Pharmaprojects, WHO international clinical trials registry platform (ICTRP), PubMed and grant databases were searched to identify candidate medicines (including drugs, dietary supplements and biologics) and populate the Accelerating Innovations for Mothers (AIM) database. This database was screened for all candidates that have been investigated for preterm birth. Candidates in clinical development were ranked against criteria from TPPs, and classified as high, medium or low potential. Preclinical candidates were categorised by product type, archetype and medicine subclass.

Results

The AIM database identified 178 candidates. Of the 71 candidates in clinical development, ten were deemed high potential (Prevention: Omega-3 fatty acid, aspirin, vaginal progesterone, oral progesterone, L-arginine, and selenium; Treatment: nicorandil, isosorbide dinitrate, nicardipine and celecoxib) and seven were medium potential (Prevention: pravastatin and lactoferrin; Treatment: glyceryl trinitrate, retosiban, relcovaptan, human chorionic gonadotropin and Bryophyllum pinnatum extract). 107 candidates were in preclinical development.

Conclusions

This analysis provides a drug-agnostic approach to assessing the potential of candidate medicines for spontaneous preterm birth. Research should be prioritised for high-potential candidates that are most likely to meet the real world needs of women, babies, and health care professionals.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12884-023-05842-9.

Keywords: Aspirin, Celecoxib, Drug development, Isosorbide dinitrate, L-arginine, Nicardipine, Nicorandil, Omega-3 fatty acid, Oral progesterone, Preterm labour, Selenium, Tocolytics, Vaginal progesterone

Background

Preterm birth (born alive prior to 37 completed weeks’ gestation) is the leading cause of death in children under five and a major cause of newborn morbidity [1–3]. Up to 50% of preterm births are due to spontaneous preterm labour [4]. There are limited medicines in clinical use for spontaneous preterm birth/labour. Several drugs can delay preterm labour—a 2022 Cochrane network meta-analysis on tocolytics found all subclasses (betamimetics, COX inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, magnesium sulfate, oxytocin receptor antagonists, nitric oxide donors) are probably effective at delaying preterm birth by 48 h, and that calcium channel blockers possibly reduce the risk of some adverse neonatal outcomes including respiratory and neurodevelopmental morbidity [5]. The World Health Organization (WHO) subsequently recommended the calcium channel blocker nifedipine as the preferred tocolytic agent, however noted a lack of long-term follow up studies [6]. All tocolytic drugs in clinical use, apart from atosiban, are repurposed medicines that are used off-label in pregnant women [7]. Fewer options are available for preventing spontaneous preterm birth – while vaginal progesterone can prevent preterm birth in high- risk women (women a history of spontaneous preterm birth or shortened cervix), some clinical indications for use (short cervical length, detected via ultrasound) are not easy to identify in all settings [8]. In October 2022, the FDA recommended Makena (injectable 17-alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate) be withdrawn from market due to evidence of a lack of clinical benefit in preventing preterm birth [9, 10].

The lack of innovation in medicines for spontaneous preterm birth/labour can be attributed to the broader, long-standing lack of investment in research and development (R&D) for new medicines for obstetric conditions [11]. A 2014 analysis of maternal research funding demonstrated that very few funders, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry, place a high priority on maternal health medicines R&D [12]. In 2008 there were fewer drugs in active development for all maternal conditions than for the rare disease amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [13]. This “drug drought” in maternal medicines has meant only two new drugs—the tocolytic atosiban and carbetocin for prevention of postpartum haemorrhage – have been licenced over the past 30 years specifically for use among pregnant women [14].

The Accelerating Innovation for Mothers (AIM) project was initiated to catalyse the development of new medicines for obstetric conditions [15]. Within AIM, we previously developed two target product profiles (TPPs) for new medicines to prevent spontaneous preterm birth and manage preterm labour [16]. TPPs are strategic documents that describe the key characteristics of new products and have helped drive R&D in vaccines, diagnostics and therapeutics for multiple conditions [17–21]. In this study, we aimed to analyse a database established by the AIM project [22–24] of the pipeline of medicines for preterm birth and compared candidates to the TPPs to identify the most promising options for reducing preterm birth-related morbidity and mortality globally.

Materials and methods

AIM database of drug development pipeline

Development of the AIM medicine pipeline database has been previously described [22–25]. Briefly, the database was created by systematically searching leading pharmaceutical databases (Adis Insight and Pharmaprojects), WHO international clinical trials registry platform (ICTRP) and other clinical trial registries, PubMed and grant databases of top maternal health product funders to identify candidate medicines (including drugs, dietary supplements and biologics) investigated for five priority maternal conditions (preeclampsia, preterm birth/labour, post-partum hemorrhage, fetal growth restriction and fetal distress). The AIM project database identified a total of 444 candidates that were investigated during the period 2000 to 2021. Candidates under investigation for preterm birth/labour were included in the database regardless of aetiology of preterm birth. Preterm labor/birth had the largest number of candidates for any of the five pregnancy-related conditions, with 178 unique candidates.

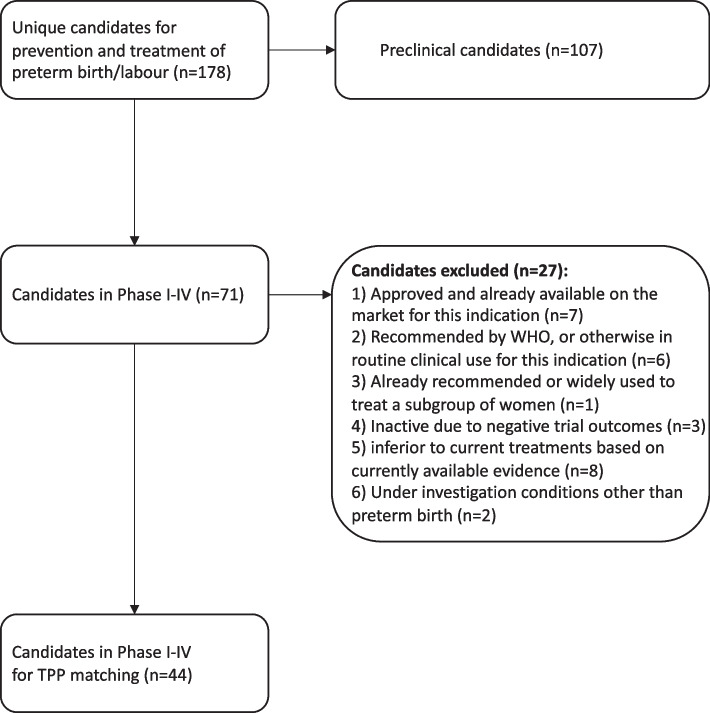

To identify high-potential candidates in the pipeline, we applied a systematic, stepwise approach to assessing all 178 candidates for preterm birth prevention and preterm labour management. First, we excluded candidates that were: 1) approved and already available on the market for this indication; 2) recommended by WHO, or otherwise in routine clinical use for this indication; 3) already recommended or widely used to treat a subgroup of women within the condition of interest (for example, levothyroxine in pregnant women with hypothyroidism); 4) inactive due to negative trial outcomes (such as adverse maternal or neonatal outcomes); 5) indicated as inferior to current treatments based on currently available evidence; and 6) under investigation for other conditions related to labour/birth, such as labour induction, and not preterm birth.

TPP matching of candidates in development phase I, II or III

We previously developed TPPs to guide development of novel medicines for prevention of spontaneous preterm birth and management of preterm labour – the first TPPs developed for preterm birth [26]. These TPPs included 21 parameters with “minimum” and “preferred” criteria defined for each parameter (Tables S1 and S2)—an ideal medicine would be one that met the preferred criteria for all 21 parameters. For the current analysis, we used a drug agnostic systematic matching approach [23], which utilises nine critical parameters from the TPPs as criteria to rank candidates in Phases I, II or III (Table 1, Table S1). These nine variables were selected based on their relative importance for wide-scale implementation, and the selection was informed by expert interviews during TPP development. TPP matching was performed for each candidate by two authors independently, and where differences arose, a third author was consulted to determine final matching.

Table 1.

Critical parameters from target product profiles used to rank candidates in clinical development

| 1. Setting – Has the medicine been trialled for this indication in high-income country settings only, low-middle income country settings only, or both? |

| 2. Efficacy—In the available trials for this indication, has the medicine demonstrated clinically significant effect on the efficacy outcome/s? |

| 3. Need for a companion diagnostic test—In the available trials for this indication, has the medicine required the routine use of a companion diagnostic test? |

| 4. Need for clinical monitoring—In the available trials for this indication, has the medicine required the use of routine monitoring, or additional clinical monitoring? |

| 5. Safety—In the available trials for this indication, has the medicine demonstrated any safety concerns? |

| 6. Mode of administration – In the available trials for this indication, what is the mode of administration? If no trials have been completed, what is the mode of administration for repurposed medicine? |

| 7. Treatment adherence—In the available trials for this indication, what has been the adherence to treatment? |

| 8. Stability—is cold chain required for this product? |

| 9. WHO Essential Medicines List—Is the product is currently listed on the WHO Essential Medicines List or not? |

Preclinical candidates were assessed descriptively, including categorisation by product type, new or repurposed, and medicine subclass. Comparison of preclinical candidates to the TPPs was not performed, given the lack of data for most of the TPP-based criteria.

Data visualisation and ranking of potential

For each variable, candidates were assigned a numerical score representing the level of matching for a given variable of the TPP (Table 1 and Tables S1 and S2), as described in our previous study [23]. Given the greater importance of clinical efficacy and safety criteria, these variables were given a greater weight. These scores were also represented graphically – candidates were classified as having met preferred (dark green), met minimum (light green), partially met minimum (yellow) or did not meet minimum (red). Hence, the ranking of a candidate as high, medium or low is based on a systematic assessment of available evidence against pre-specified criteria.

Results

Of the 178 candidates in the pipeline, seven (3.9%) were approved and on the market for the prevention or management of preterm birth (allylestrenol, atosiban, injectable 17-alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate, hexoprenaline, isoxsuprine, fenoterol, ritodrine). An additional 11/178 (6.2%) candidates are approved for other clinical conditions and have been used off-label for preterm birth (terbutaline, salbutamol, vaginal/topical progesterone, magnesium sulphate, orciprenaline, nicardipine, nifedipine, indomethacin, sulindac) or to promote fetal well-being following preterm delivery (dexamethasone, betamethasone).

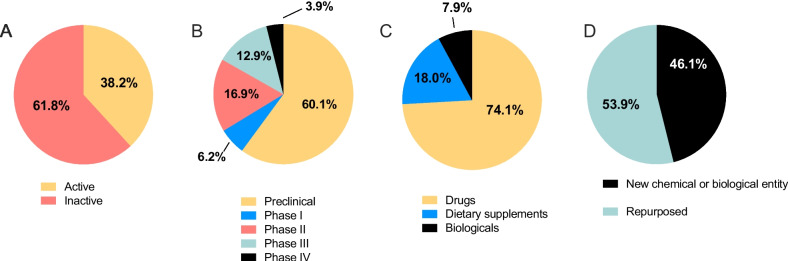

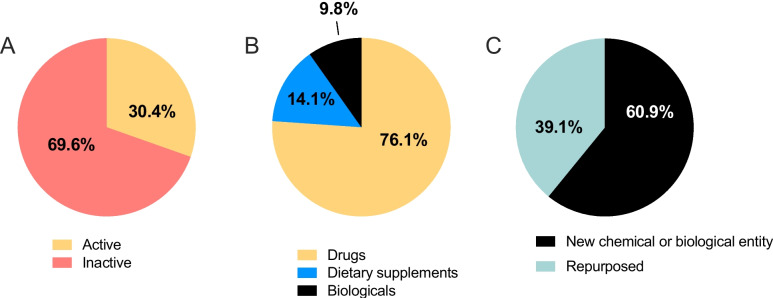

In total, 68 (38.2%) candidates were currently active and 110 (61.8%) were inactive (no updates since 2018; Fig. 1A). The majority (107 candidates; 60.1%) were at the preclinical stage of development (Fig. 1B). In total, 11 candidates were in Phase I (6.2%), 30 candidates in Phase II (16.9%), 23 candidates in Phase III (12.9%) and 7 candidates in Phase IV (3.9%). Across all 178 candidates, 132 (74.1%) were classified as drugs, 14 (7.9%) were biologics and 32 (18.0%) were dietary supplements (Fig. 1C). In total, 82 (46.1%) were new chemical/biological entities and 96 (53.9%) were repurposed (Fig. 1D). Of the 71 candidates in clinical development, 27 were removed from further analysis due to the exclusion criteria, leaving 44 candidates (Fig. 2). In total, 10 clinical phase candidates were ranked as high potential, 7 as medium potential and 27 as low potential.

Fig. 1.

Details of the candidates in the R&D pipeline for preterm birth/labor. Summary of the 178 candidates in the R&D pipeline for the prevention of preterm birth and management of preterm labor from 2000 – 2021. The proportion of candidates A in active development, and inactive (no publications since 2018), B in each phase of the development pipeline, C classified as drugs, biologicals or dietary supplements, and D classified as new chemical or biological entities or repurposed drugs

Fig. 2.

Flowchart of assessment of candidates against the eligibility criteria

Prevention of spontaneous preterm birth

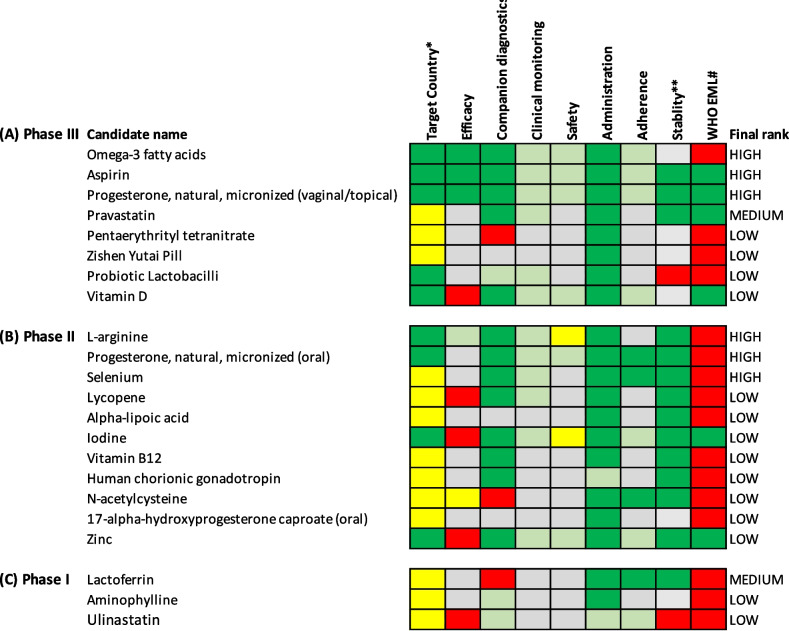

Eight candidates were assessed for prevention in Phase III clinical trials (Fig. 3a), 10 in Phase II (Fig. 3b) and three in Phase I (Fig. 3c). Six candidates were ranked as high potential and two as medium potential. The evidence for candidates ranked low potential is presented in Additional file 2: Appendix B.

Fig. 3.

Visual representation of target product profile matching for candidates to prevent spontaneous preterm birth. A traffic light system to visualise each candidate for preterm birth prevention at A Phase III, B Phase II and C Phase I clinical development. Candidates are classified as met preferred (dark green), met minimum (light green), partially met minimum (yellow) and did not meet the minimum (red) requirements in the target product profiles. When insufficient information is available for a specific variable, they have been classified as not yet known (grey). *Target country is classified as trials being conducted in HIC and LMIC (dark green), HIC only or LMIC only (both yellow) or country not stated (grey). **Stability has been classified as does not require cold chain (green), requires cold chain (red) or unsure (grey). #WHO EML is classified as candidate is already on the WHO EML list (green), or candidate is not on the WHO EML list (red). Final rank has been determined by quantification of the matching to the target product profiles (see Tables S1 and S2 for details of quantification coding), with efficacy and safety given a greater weight than other variables. HIC = high-income country, LMIC = low- or middle-income country, EML = essential medicines list

Phase III candidates

Aspirin, vaginal/topical progesterone and omega-3 fatty acids supplementation were ranked as high potential (Fig. 3a). A 2021 individual participant data meta-analysis found that vaginal progesterone reduces the risk of preterm birth (nine trials, 3769 women, RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.68 – 0.90) in women at increased risk, defined as women with a history of preterm birth and/or short cervix (< 25 mm) [8]. A 2018 Cochrane review examining omega-3 fatty acid supplementation during pregnancy found high quality evidence of a reduced risk of preterm birth < 37 weeks (26 trials, 10,304 women, RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.81 – 0.97) and < 34 weeks (9 trials, 5204 women, RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.44 – 0.77) [27]. Meta-analysis of 35 placebo-controlled trials found taking low dose aspirin during pregnancy reduced the risk of preterm birth (46,568 women, RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.86 – 0.94) [28], however, it is unclear if aspirin is beneficial in preventing spontaneous preterm birth, or if this benefit relates to the known effects of aspirin in reducing the risk of preeclampsia [29]. A 2017 individual participant data meta-analysis including 17 trials (including 28,797 women) evaluating aspirin for the prevention of preeclampsia, found that aspirin reduced the risk of spontaneous preterm birth at < 37 weeks (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.86 – 0.996) and < 34 weeks (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.76 – 0.99) [30]. Similar reductions were observed in a 2018 secondary analysis of a trial investigating the effect of low-dose aspirin to prevent preeclampsia. In women with a low risk of preeclampsia, aspirin reduced the odds of spontaneous preterm birth < 34 weeks’ gestation compared to placebo (OR 0.43, 95% CI 0.26 – 0.84; 2543 women) [31]. However, the 2022 APRIL trial assessed the effects of aspirin prophylaxis in 406 women with a history of preterm birth, and found no significant difference in the risk of preterm birth (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.58 – 1.20) [32].

Pravastatin was ranked as medium potential (Fig. 3a). The clinical efficacy of pravastatin for preventing spontaneous preterm birth remains unknown. A 2021 meta-analysis of trials and observational studies found that any statin use during pregnancy was associated with a non-significant reduction in the risk of preterm birth (four studies, 483 women, OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.06 – 3.70), but also a significant increase in risk of spontaneous abortion (six studies, 4,165 women, OR 1.36, 95% CI 1.10 – 1.68) [33]. One mechanism by which pravastatin is thought to prevent preterm birth is by preventing preeclampsia [34], however a 2021 Phase III trial in 1120 women reported that pravastatin was not effective for this indication [35].

Phase II candidates

Oral progesterone, the amino-acid L-arginine and the trace element selenium were ranked high potential (Fig. 3b). A 2021 individual participant data meta-analysis of progesterone for preventing preterm birth found oral progesterone reduced the risk of preterm birth < 24 weeks (RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.41 – 0.90) [8]. However, this only included 2 trials of 183 women and more evidence is required to evaluate clinical efficacy. Meta-analysis of L-arginine supplementation in women at high risk of preeclampsia or with mild chronic hypertension showed it reduces the risk of preterm birth (three trials, 625 women, RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.30 – 0.85) [36]. While there are currently no clinical trials examining the effects of L-arginine supplementation on prevention of spontaneous preterm birth, a prospective cohort study of 7591 pregnant women in Tanzania found that the level of L-arginine dietary intake was associated with a decreased risk of spontaneous preterm birth [37].

Evidence of clinical efficacy of selenium is limited to a small trial in 180 HIV-positive pregnant women that found selenium reduced the risk of preterm birth (RR 0.32, 95% CI 0.11 – 0.96) [38]. Meta-analysis of observational data has also reported an association between prenatal maternal selenium plasma concentrations and reduced odds of preterm birth (17 cohorts, 9946 singleton births, OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.90 – 1.0) [39].

Phase I candidates

Lactoferrin was ranked as medium potential (Fig. 3c), and there is evidence from a small trial of 125 pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis that vaginal lactoferrin significantly reduced the rate of preterm birth (25.0% vs 44.6%, p = 0.02) [40]. However, lactoferrin did not meet the minimum requirements for companion diagnostics, as it requires a diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis, which involves laboratory testing of vaginal discharge to identify the causative agent. Additional laboratory diagnostic testing may act as a barrier to implementation in some settings.

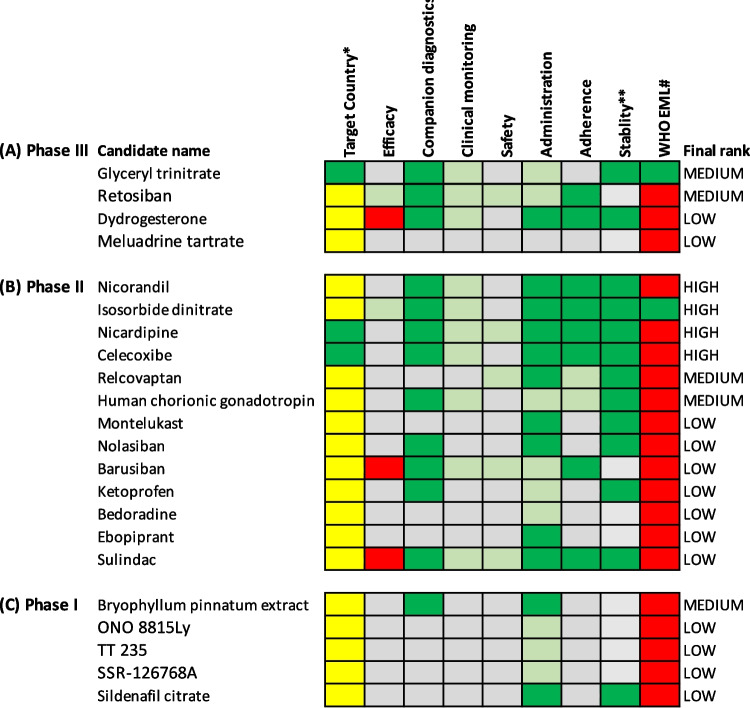

Management of preterm labour

There were four candidates assessed for management of preterm labour in Phase III (Fig. 4a), 13 in Phase II (Fig. 4b) and five in Phase I (Fig. 4c). Four candidates were ranked as high potential and five as medium potential. The evidence for candidates ranked low potential is presented in Additional file 2: Appendix B.

Fig. 4.

Visual representation of target product profile matching for candidates to manage preterm labor. A traffic light system to visualise each candidate for preterm labor treatment at A Phase III, B Phase II and C Phase I clinical development. Candidates are classified as met preferred (dark green), met minimum (light green), partially met minimum (yellow) and did not meet the minimum (red) requirements in the target product profiles. When insufficient information is available for a specific variable, they have been classified as not yet known (grey). *Target country is classified as trials being conducted in HIC and LMIC (dark green), HIC only or LMIC only (both yellow) or country not stated (grey). **Stability has been classified as does not require cold chain (green), requires cold chain (red) or unsure (grey). #WHO EML is classified as candidate is already on the WHO EML list (green), or candidate is not on the WHO EML list (red). Final rank has been determined by quantification of the matching to the target product profiles (see Tables S1 and S2 for details of quantification coding), with efficacy and safety given a greater weight than other variables. HIC = high-income country, LMIC = low- or middle-income country, EML = essential medicines list

Phase III candidates

No Phase III candidates were identified as high potential. Retosiban, a selective oxytocin antagonist and glyceryl trinitrate, a nitric oxide donor were ranked medium potential (Fig. 4a). A pilot trial of 29 pregnant women suggested retosiban has a favourable safety and tolerability profile [41]. A small placebo-controlled trial of 64 women in preterm labour found retosiban significantly prolonged pregnancy by an average of 8.2 days and reduced the risk of preterm birth (RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.15 – 0.81) [42]. A Phase III trial of retosiban compared to placebo or atosiban was stopped early due to failure to recruit [43]. Data from this stopped trial suggested a possible increase in time to delivery compared to placebo (23 women) and no significant difference in time to delivery between retosiban and atosiban (97 women). The 2022 Cochrane network meta-analysis on tocolytics found that nitric oxide donors such as Glyceryl trinitrate (13 trials) probably delay preterm birth by 48 h (RR 1.17, 95% CI 1.05 – 1.31) and 7 days (RR 1.18, 95% CI 1.02 – 1.37) [5].

Phase II candidates

Nicardipine, nicorandil, isosorbide dinitrate and celecoxib were all ranked high potential and are all from the same drug class as tocolytics in clinical use (Fig. 4b). Nicardipine and nicorandil are calcium channel blockers, isosorbide dinitrate is a nitric oxide donor and celecoxib is a COX-2 inhibitor. The 2022 Cochrane network meta-analysis found that calcium channel blockers, nitric oxide donors and COX-2 inhibitors were all effective in delaying preterm birth compared to placebo or no tocolytic [5]. COX inhibitors and calcium channel blockers are both possibly effective at delaying birth by 48 h (RR 1.11, 95% CI 1.01 – 1.23, and RR 1.16, 95% CI 1.07 – 1.24, respectively). Calcium channel blockers are also probably effective at delaying preterm birth by 7 days (RR 1.15, 95% CI 1.04 – 1.27), however are probably more likely to result in cessation of treatment (RR 1.23, 95% CI 1.23 – 7.11). Importantly, calcium channel blockers possibly reduce the risk of adverse neonatal outcomes including neurodevelopmental morbidity (RR 0.51, 95% CI 0.30 – 0.85), respiratory morbidity (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.53 – 0.88) and low birthweight (RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.28 – 0.87) [5]. As mentioned above, nitric oxide donors (13 trials) probably delay preterm birth and are ranked highest for delaying birth by 48 h and 7 days [5].

Human chorionic gonadotropin and relcovaptan were ranked medium potential (Fig. 4b). A placebo-controlled trial of 100 pregnant women suggested human chorionic gonadotropin can significantly delay labour [44] while two other trials (165 pregnant women) suggest it is as effective as magnesium sulfate at delaying labour for 48 h, with fewer side-effects [45, 46]. A pilot trial (18 women) of relcovaptan, an orally active vasopressin V1a receptor inhibitor, found it effectively reduced uterine contractions during premature labour compared to placebo [47], however development was discontinued in 2001 before the results of Phase II trials in Sweden, France and Poland were reported.

Phase I candidates

Bryophyllum pinnatum extract, a herbal succulent that contained phenolic constituents was ranked medium potential (Fig. 4c). The authors of a trial of 26 pregnant women comparing Bryophyllum pinnatum extract to nifedipine suggested it might be promising, but the study was stopped early due to poor recruitment [48].

Preclinical candidates

Of the 107 candidates in preclinical development, 15 were excluded due to adverse effects, being inferior to other products in development or being used preclinically as a research tool to investigate pathophysiology and not intended for clinical translation. Of the 92 remaining candidates, 28 (30.4%) were active and 64 (69.6%) were inactive (Fig. 5A). Most candidates were drugs (70 candidates, 76.1%); 13 were dietary supplements (14.1%) and 9 were biologics (9.8%; Fig. 5B). There were 36 repurposed medicines (39.1%) and 56 new chemical or biological entities (60.9%; Fig. 5C). Overall, 34 candidates were evaluated for the prevention of preterm birth, 56 were evaluated for the management of preterm labour and two were evaluated for both the prevention and management (resveratrol and rolipram).

Fig. 5.

Details of the preclinical candidates in the R&D pipeline for preterm birth/labor. Summary of the preclinical candidates in the R&D pipeline for the prevention of preterm birth and treatment of preterm labor from 2000 – 2021. The proportion of candidates A in active development, and inactive (no publications since 2018), B classified as drugs, biologicals or dietary supplements, and C classified as new chemical or biological entities or repurposed drugs

A diverse range of medicine subclasses were under investigation at the preclinical stage (Tables 2 and 3). The most common preclinical medicine subclass for prevention were amino acid/peptides (14 candidates, 38.9%; Table 2). Amino acid/peptides were also the most common subclass for management of preterm labour (12 candidates, 20.7%) followed by tocolytics and vascular agents (10 candidates each, 17.2%; Table 3). We identified 13 candidates with some concerns and six candidates with major concerns about the quality of the preclinical evidence. Concerns identified included lack of preterm birth animal model studies, conflicting results between studies of the same candidate and extremely high dose of candidate medicine used in preclinical studies.

Table 2.

Summary of preclinical candidates for preterm birth prevention

| Drug subclass | Candidate | Summary | Archetype | Proposed administration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevention of preterm birth | ||||

| Amino acid-peptide | AG126 | A cell-permeable tyrophostin/tyrosine kinase inhibitor | New | Unspecified |

| AG1288 | A tyrosine kinase inhibitor | New | Unspecified | |

| Anti- Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) monoclonal antibody | Competitively binds to the TLR4 receptor, blocking TLR4-induced inflammation | New | Intravenous | |

| Etanercept | Dimeric fusion protein that binds specifically to TNF | Repurposed | Unspecified | |

| Histone deacetylase inhibitors (nanosuspension) | Anti-inflammatory histone deacetylase inhibitors delivered in a nanosuspension | New | Vaginal | |

| IMD-0560 | Novel IκB kinase β inhibitor | New | Vaginal | |

| Melatonin | Hormone associated with the sleep–wake cycle | Repurposed | Oral | |

| NS-398 | A selective COX-2 inhibitor with great specificity for prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 | New | Intravenous | |

| Rytvela | Small, non-competitive IL-1R-biased ligand | New | Unspecified | |

| SB 202190 | A highly selective, potent, cell-permeable p38 MAP kinase inhibitor | New | Unspecified | |

| SB 239063 | A second-generation p38 MAP kinase inhibitor | New | Unspecified | |

| Super-repressor (SR) IχBα (exosome delivery) | NF-κB inhibitor delivered by engineered extracellular vesicles | New | Injection | |

| Synthetic TLR4 | Synthetic TLR4 protein | New | Intravenous | |

| Vaginal progesterone (nanosuspension) | Natural progesterone delivered in a nanosuspension | New | Vaginal, rectal, topical | |

| Antibiotics | Sirolimus | Macrolide antibiotic with potent anti-inflammatory effects | Repurposed | Oral |

| Anti-depressant | Rolipram | A selective phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor | New | Oral, injectable |

| Cell therapy | Exosome-based protein therapeutics | Proprietary Exosome engineering for Protein loading via Optically reversible Protein–Protein interaction (EXPLOR™) technology | New | Injectable |

| Pen-NBD (cell-penetrating peptide delivery) | Cell penetrating peptides (CPPs) are novel vectors that can traverse cell membranes without the need for recognition by cell surface receptors | New | Intravenous | |

| Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs | Sulfasalazine | Releases its breakdown product, 5-aminosalcyclic acid into the colon | Repurposed | Oral |

| Enzyme inhibitors (statins) | Simvastatin | Antilipemic agent from the statin family of drugs | Repurposed | Oral |

| Herbal | Abeliophyllum distichum Nakai leaf extract | A deciduous shrub native to South Korea being investigated for anticancer, antidiabetic, antihypertensive and anti-inflammatory activities | New | Oral |

| Astragali radix extract | Dried root of Astragalus membranaceus Bunge. A traditional Chinese medicine | Repurposed | Oral | |

| Cucurbita moschata extract | Pumpkin extract | Repurposed | Oral | |

| Parthenolide | A sesquiterpene lactone occurring naturally in the plant feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium) | New | Oral; intravenous | |

| Immunosuppressant | Tocilizumab | Treatment for rheumatoid arthritis | Repurposed | Intravenous, subcutaneous |

| Opioid receptor antagonist | ( +)-Naloxone | Isomer of (-)-naloxone (Narcan), a medication indicated in opioid overdose | New | Intravenous, intramuscular, intraperitoneal, oral |

| ( +)-Naltrexone | Isomer of (-)-naltrexone (ReVia or Vivitrol), a medication used to manage opioid use | New | Intravenous, intramuscular, intraperitoneal, oral | |

| Organic compound | U-0126 | Inhibits activation of MAPK (ERK1/2) by inhibiting kinase activity of MAP Kinase Kinase | New | Subcutaneous |

| Polyphenol | Gallic acid | A trihydroxy benzoic acid found in gallnuts, sumac, witch hazel, tea leaves, oak bark and other plants | Repurposed | Oral |

| Honokial | A polyphenol lignan. The primary component of the traditional Chinese medicinal herb Houpo | Repurposed | Oral | |

| Nobiletin | A polymethoxy flavone abundant in citrus flavedo | Repurposed | Oral | |

| Resveratrol | A stilbenoid produced by several plants in response to injury | Repurposed | Oral | |

| Probiotics | Microbiome therapeutics | Live biotherapeutics being developed for preterm labour | New | Unspecified |

| Small molecule | Sc514 | Small molecule which targets the intracellular NF-κB pathway | New | Unspecified |

| TPCA-1 | IKKβ inhibitor | New | Unspecified | |

| Unclassified | Replens gel | A bioadhesive vaginal moisturiser, and the vehicle for vaginal progesterone | Repurposed | Vaginal |

Table 3.

Summary of preclinical candidates for preterm labour management

| Drug subclass | Candidate | Summary | Archetype | Administration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Management of preterm labor | ||||

| Amino acid-peptide | 15d-PGJ2 | An anti-inflammatory prostaglandin | New | Intravenous |

| Azapeptide analogues | Azapeptides are peptide analogs in which one or more of the amino residues is replaced by a semicarbazide | New | Subcutaneous | |

| BRL 37344 | A selective agonist of the β3 adrenergic receptor | New | Unspecified | |

| Butaprost | A structural analogue of PGE2 | New | Unspecified | |

| CyPPA | Stimulates myometrial Ka(Ca)2.2/2.3 channels to supress Ca2+-mediated uterine contractions | New | Injectable | |

| Exedine-4 | A 39 amino-acid polypeptide isolated from Gila monster lizard saliva | Repurposed | Subcutaneous, intravenous | |

| Leptin | Hormone synthesised in adipose tissue, involved in regulation of energy balance, metabolism and body weight | Repurposed | Oral, subcutaneous | |

| N-acetylcysteine (nanoparticle delivery) | A precursor to glutathione delivered via targeted dendrimer nanoparticles | New | Intravenous | |

| PDC113.824 | An experimental peptidomimetic prostoglandin F2α receptor ligand | New | Injectable | |

| SCH-772984 | A selective inhibitor of ERK1/2 | New | Unspecified | |

| SKF-86002 | A p38 MAPK inhibitor | New | Unspecified | |

| Surfactant protein A | Protein component of surfactant, produced in the fetal lung | New | Injection | |

| Anti-depressant | Rolipram | A selective phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor | New | Oral, injectable |

| Anti-convulsant | Retigabine | An adjuvant therapy to treat partial epilepsies | Repurposed | Oral |

| Anti-malarial | Chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine | An aminoquinolone derivative developed to treat malaria | Repurposed | Intravenous, oral |

| Herbal | Carvacrol | A phenolic monoterpenoid found in essential oils of oregano, thyme, pepperwort, wild bergamot and other plants | New | Unspecified |

| Ananas comosus, ethyl acetate fraction | Pineapple extract and traditional medicine | Repurposed | Oral | |

| Curcuma aeruginosa rhizome | A common medicinal plant used in Southeast Asia | Repurposed | Unspecified | |

| Pimpinella anisum extract | Anise, a common traditional medicine | Repurposed | Oral | |

| Paeoniflorin | A component of the dried root extract of Paeonia lactiflora Pall used widely in China, Korea, and Japan's traditional medicine | New | Intravenous | |

| Hydrogen sulfide donors | GYY4137 | Sulphide-releasing aspirin | New | Intravenous |

| Muscle relaxant | Botulinum toxin A | A neurotoxic protein, commonly known as Botox | Repurposed | Intramuscular, intravenous |

| Organic compound | 1,10-Phenatroline | Heterocyclic organic compound that targets bitter taste receptors | New | Unspecified |

| Alpha-bisabolol | An unsaturated, optically active sesquiterpene alcohol distilled from plant essential oils | Repurposed | Unspecified | |

| Citral | A pair, or mixture of terpenoids present in the oils of several plants including lemons, organges, limes and lemongrass | Repurposed | Oral, intravenous | |

| OXznl | A resorcylic acid lactone derived from fungus | New | Injectable | |

| Polyphenol | Galetin 3,6-dimethyl ether | A Brazilian folk medicine | Repurposed | Intravenous, oral |

| Resveratrol | A stilbenoid produced by several plants in response to injury | New | Unspecified | |

| Scutellaria baicalensis root extract | Tocolytic traditional Chinese medicinal herb | Repurposed | Oral | |

| Tannic acid | A weak acid found in nutgalls formed by insects on twigs of certain oak trees | Repurposed | Oral, vaginal, topical | |

| Proton-pump inhibitors | Esomeprazole | Medication to reduce stomach acid, treatment for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GERD) | Repurposed | Oral, intravenous |

| Lansoprazole | Medication to reduce stomach acid | Repurposed | Oral, intravenous | |

| Omeprazole | Medication to reduce stomach acid | Repurposed | Oral, intravenous | |

| Pantoprazole | Medication to reduce stomach acid | Repurposed | Oral, intravenous | |

| Rabeprazole | Medication to reduce stomach acid | Repurposed | Oral, intravenous | |

| Thalidomide analogue | 4APDPMe | Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor | New | Intravenous, intramuscular |

| 4NO2DPDMe | Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor | New | Intravenous, intramuscular | |

| Tocolytic | AS603831 | Non-peptide oxytocin receptor antagonist | New | Oral, intravenous |

| AS604872 | Prostaglandin F2α receptor antagonist | New | Oral | |

| HC067047 | Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 inhibitor | New | Intraperitoneal | |

| Hydrozone sulfanilide oxytocin antagonists | Class of oxytocin antagonists with high degree of selectivity against the closely related vasopressin receptors | New | Intravenous | |

| Indomethacin (nanoparticle delivery) | Nanoparticle preparation of a highly potent tocolytic | New | Oral | |

| PGN-1473 | Prostaglandin EP2 receptor agonist | New | Intrauterine | |

| PGN-9856 | Prostaglandin EP2 receptor agonist | New | Injectable | |

| Salbutamol (nanoparticle delivery) | Bronchodilator used to treat asthma and COPD used off label as a tocolytic, nanoparticles delivered via liposome | Repurposed | Unspecified | |

| SAR-150640 | Selective β3 adrenergic receptor | New | Parenteral | |

| THG113.31 | Selective prostaglandin F2-α antagonsist | New | Intravenous, topical | |

| Uricosuric agent | Benzbromarone | Non-competitive inhibitor of xanthine oxidase used in the treatment of gout | Repurposed | Oral |

| Vascular agents | Amiloride | An antihypertensive | Repurposed | Oral, intraperitoneal |

| Isradipine | Calcium-channel blocker related to nifedipine | Repurposed | Oral | |

| LDD175 | BK(Ca) channel opener | New | Injectable | |

| Levosimendan | A hydrozone and pyridazine derivative | Repurposed | Intravenous, oral | |

| MONNA | Aanoctamin 1 antagonist | New | Unspecified | |

| Nebivolol | A third generation, FDA‐approved β1‐adregneric receptor (β1AR) antagonist | Repurposed | Oral | |

| Nifedipine (nanoparticle delivery) | PEGylated liposomes loaded with the potent tocolytic nifedipine | New | Intravenous, oral, rectal | |

| Pinacidil | A cyanoguanidine drug that acts by opening ATP-sensitive potassium channels | Repurposed | Oral | |

| S-Nitrocysteine | A low molecular weight, cell-permeable nitrosothiol and nitric oxide donor | New | Injectable | |

| ZD-7288 | A specific bradycardic agent | New | Unspecified | |

Discussion

Main findings

We systematically analysed the medicines R&D pipeline for preterm birth/labor between 2000 and 2021. Of the 178 candidates approximately 4% have made it to market for this indication. Novel medicines accounted for 46% of candidates in clinical development for management of preterm labour, a substantially higher proportion compared to other maternal conditions [25]. However, we identified only one novel medicine – oral 17-alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate—in clinical development for preterm birth prevention. Through matching candidates to pre-specified TPP criteria, we identified six high priority candidates for spontaneous preterm birth prevention (omega-3 fatty acids, aspirin, vaginal and oral progesterone, pravastatin, l-arginine and selenium) and four high priority candidates for management of preterm labour (nicorandil, isosorbide dinitrate, nicardipine and celecoxib), which warrant R&D investment.

Interpretation in light of other evidence

A 2008 analysis of the obstetric R&D pipeline identified 67 candidates in development for maternal conditions between 1980 and 2007 [13]; in contrast, we identified 444 candidates in development for five obstetric conditions between 2000 and 2021. Both studies found preterm birth/labor to be the dominant indication (45% and 40%, respectively), contributing the greatest number of individual candidates in the pipeline [13]. Given that preterm birth is the leading cause of mortality in newborns and children globally, this is perhaps unsurprising [49]. In high-income countries, where the majority of global research funding is spent [50], preterm birth is a leading cause of long-term disability and imposes significant societal and financial costs [51].

Most candidates in the preterm birth pipeline that had made it to market or were used extensively off-label were tocolytics. Our analysis identified four high- and five medium-potential candidate tocolytics, in addition to the tocolytics currently available. Strikingly, all high potential and two medium potential candidates are from the same drug classes as known effective tocolytics, including COX-inhibitors (celecoxib), nitric oxide donors (isosorbide dinitrate, glyceryl trinitate), oxytocin receptor antagonists (retosiban) and calcium channel blockers (nicorandil, nicardipine) [6]. Our analysis highlights the relatively strong interest in R&D for improved tocolytics, likely because of the efficacy evidence on drugs within the same class and that the mechanisms underlying labour progression are well characterised, providing specific drug targets [52].

In contrast, there are currently few medicines that are recommended for the prevention of preterm birth. A significant amount of active R&D concerns progestin medicines for preterm birth prevention. Studies have investigated different formulations and routes of administration (such as vaginal and oral natural micronized progesterone), as well as aiming to identify which sub-population of women will benefit most from progesterone [8]. Recently, evidence was in favour of using vaginally administered progesterone in women at increased risk of preterm birth, particularly women with a short cervix [8], and hence some guidelines recommended its use for preventing preterm birth in women with a history of preterm birth and/or cervical shortening [53–55]. However, a 2022 meta-analysis found that progesterone was not effective in preventing recurrent preterm birth in women with a history of spontaneous preterm birth, in the absence of cervical shortening [56]. Assessment of cervical length requires access to transvaginal ultrasound, which is not available in all settings. Two meta-analyses from 2021 found no significant effect of injectable 17-alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate in preventing preterm birth, prompting the FDA, in 2022, to recommend its withdrawal from market [8, 57]. These recent additions to the body of evidence on progesterone’s efficacy have prompted updated guidance from American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) on use of progesterone in pregnant women [58]. Pending the FDA final determination, hydroxyprogesterone caproate injection continues to be recommended by the International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (FIGO) in women at risk of spontaneous preterm birth [53].

Dietary supplements represented 18% of the candidates under investigation for preterm birth. Trials of some of these supplements, including vitamins A, C and E, have been conclusively shown not to be effective at preventing preterm birth [59–61]. In contrast, omega-3 fatty acids, L-arginine and selenium supplementation all have promising clinical efficacy evidence, though further evidence is needed [27, 36, 38]. There are clear implementation advantages for dietary supplements – they are usual taken orally, many are low cost and widely available, and they may be viewed as natural supplements rather than drugs, which could be more acceptable to women [62]. However, questions remain about the population of women who would benefit most from these supplements, and whether companion diagnostic tests for vitamin and mineral deficiencies are required [63] which can be a barrier to implementation.

The large number of candidates in development for preterm birth/labor suggests comparatively high R&D interest for this condition. However, 62% of all candidates and 72% of candidates in preclinical development for preterm birth/labor are inactive, with no updates or published progress since 2018. For example, the promising oxytocin receptor antagonist retosiban developed by GSK was halted in Phase III trials due to difficulties with trial recruitment [43]. The complexities of conducting large, well-designed clinical trials in pregnant women is a recognised barrier inhibiting R&D for maternal conditions [15]. A 2013 review of all US-based, phase IV, pharmaceutical industry-sponsored clinical trials that included women of childbearing age between 2011–2012, found that only 1% were specifically designed for pregnant women, and 95% specifically excluded pregnant women [64]. Pharmaceutical industry representatives cite potential liability issues, additional risks related to teratogenicity and the prohibitively large sample sizes needed to demonstrate benefit as the reasons for the lack of R&D in maternal medicines [15]. To overcome these barriers, broader international coordinated efforts around high potential candidates is needed. Successful strategies have been implemented to overcome similar barriers in the development of medicines for children. For example, in 2007, “Paediatric Investigation Plans” (PIP) were introduced by the European Union, obliging companies applying for licences for new medicines to present a plan to study the medicine in children (unless inappropriate for this age group). This scheme greatly improved the product pipeline for children’s medicines, leading to over 260 new medicines or indications for children since its launch [65]. There remains an urgent need for large trials for candidate medicines for the prevention of preterm birth and the management of spontaneous preterm labor, which are adequately powered for clinically relevant neonatal outcomes.

Strengths and limitations

We have developed a novel, drug-agnostic approach for analysing the R&D pipeline for medicines for spontaneous preterm birth and preterm labor. Our analysis provides the most extensive mapping of the historic and current R&D pipeline for preterm birth/labor and identified ten high priority candidates currently in clinical development, as well as significant gaps in R&D. This approach may be useful for prioritising research for other maternal conditions, as well as other fields of drug development, particularly where TPPs already exist [18]. However, there are some limitations to this approach. Firstly, ranking of candidates relied on available information, and it is possible that data on some candidates are not publicly available. Secondly, this system of matching candidates to the TPPs was not possible for candidates in preclinical development, due to a lack of available data on many variables in the TPPs. Thus, when examining preclinical candidates, other factors such as the quality of the laboratory findings should be considered prior to further investments in clinical trials. Finally, preterm birth is a broad category that can involve many different aetiologies. It is highly unlikely that a single drug could be effective in all forms of preterm birth. All medicines under investigation for preterm birth were included in the database, as the specific aetiology an individual medicine was targeting was often poorly articulated. In the current study we analysed each candidate medicine against the TPPs for medicines to prevent spontaneous preterm birth, as this was highlighted during TPP development as the specific target population most in need [16]. As advances are made in the understanding of the causes of preterm birth the TPP, a living document, and the pipeline analysis can be updated to address additional pathologies.

Conclusion

Over the last 20 years R&D for preterm birth/labor medicines is an active area compared to other maternal conditions. However, many candidates, including promising new therapies, are currently inactive. Development of alternative tocolytics, new formulations of progestins and dietary supplements are areas of high research activity. We identified six high priority candidates for preventing spontaneous preterm birth and four high priority candidates for the management of preterm labor that best meet real-world requirements. This novel method of matching drug candidates to TPPs can help better direct research funding towards the most promising candidates and ensure new and effective therapies become available.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Appendix A. Supplementary tables. Table S1. Scoring of target product profile comparison, for quantification of potential of candidates. Table S2. Threshold for ranking of potential at each phase of the R&D development pipeline.

Additional file 2: Appendix B. Low rank candidates.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ACOG

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

- AIM

Accelerating Innovation for Mothers

- COX

Cyclooxygenase

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- FIGO

Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique

- GSK

GlaxoSmithKline plc.

- R&D

Research and development

- TPP

Target product profile

- WHO

World Health Organization

Authors’ contributions

JPV and AMG led the conceptualisation and supervision of the project and funding acquisition. AMcD, RH, AT and MG were involved in conceptualisation of the project and development of the methodology. AA was involved in conceptualisation of the project, funding acquisition and project administration. AMcD and RH performed collection, management, visualisation and analysis of all data. All authors were involved in interpretation of data. AMcD wrote the original draft of the manuscript and all authors contributed to writing and editing and had full access to the data. AMcD and JPV has accessed and verified all the data in this study. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Funding

This research was funded by The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The funders played no role in the design of the study, collection, analysis and inteptretation of the data, or in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. The database generated and analysed during the current study are available at https://www.conceptfoundation.org/accelerating-innovation-for-mothers/.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hug L, Alexander M, You D, Alkema L, Estimation UNI-aGfCM National, regional, and global levels and trends in neonatal mortality between 1990 and 2017, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(6):e710–e20. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30163-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheong JL, Doyle LW, Burnett AC, Lee KJ, Walsh JM, Potter CR, et al. Association between moderate and late preterm birth and neurodevelopment and social-emotional development at age 2 years. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(4):e164805. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.4805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, Walsh MC, Carlo WA, Shankaran S, et al. Trends in care practices, morbidity, and mortality of extremely preterm neonates, 1993–2012. JAMA. 2015;314(10):1039–1051. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morisaki N, Togoobaatar G, Vogel JP, Souza JP, Rowland Hogue CJ, Jayaratne K, et al. Risk factors for spontaneous and provider-initiated preterm delivery in high and low Human Development Index countries: a secondary analysis of the World Health Organization Multicountry Survey on Maternal and Newborn Health. BJOG . 2014;121(Suppl 1):101–109. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson A, Hodgetts-Morton VA, Marson EJ, Markland AD, Larkai E, Papadopoulou A, et al. Tocolytics for delaying preterm birth: a network meta-analysis (0924) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;8:CD014978. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD014978.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO recommendation on tocolytic therapy for improving preterm birth outcomes. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [PubMed]

- 7.Husslein P. Development and clinical experience with the new evidence-based tocolytic atosiban. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81(7):633–641. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2002.810709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Group E Evaluating Progestogens for Preventing Preterm birth International Collaborative (EPPPIC): meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2021;397(10280):1183–1194. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00217-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang CY, Nguyen CP, Wesley B, Guo J, Johnson LL, Joffe HV. Withdrawing approval of Makena - a proposal from the FDA center for drug evaluation and research. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(24):e131. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2031055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Federal register: proposal to withdraw approval of MAKENA; hearing - a notice by the food and drug administration on 08/17/2022. Available from: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2022/08/17/2022-17715/proposal-to-withdraw-approval-of-makena-hearing.

- 11.The Lancet Global H Progressing the investment case in maternal and child health. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(5):e558. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00178-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Footman K, Chersich M, Blaauw D, Campbell OM, Dhana A, Kavanagh J, et al. A systematic mapping of funders of maternal health intervention research 2000–2012. Global Health. 2014;10:72. doi: 10.1186/s12992-014-0072-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisk NM, Atun R. Market failure and the poverty of new drugs in maternal health. PLoS Med. 2008;5(1):e22. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhattacharya S, Innovation BHPCfRS . Safe and effective medicines for use in pregnancy: a call to action. Birmingham: University of Birmingham; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foundation C . Medicines for pregnancy specific conditions: research, development and market analysis. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDougall ARA, Tuttle A, Goldstein M, Ammerdorffer A, Aboud L, Gulmezoglu AM, et al. Expert consensus on novel medicines to prevent preterm birth and manage preterm labour: target product profiles. BJOG. 2022. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.World Health Organization. WHO target product profiles, preferred product characteristics, and target regimen profiles: standard procedure V1.02. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

- 18.Lewin SR, Attoye T, Bansbach C, Doehle B, Dube K, Dybul M, et al. Multi-stakeholder consensus on a target product profile for an HIV cure. Lancet HIV. 2021;8(1):e42–e50. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(20)30234-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murtagh M, Blondeel K, Peeling RW, Kiarie J, Toskin I. The relevance of target product profiles for manufacturers, experiences from the World Health Organization initiative for point-of-care testing for sexually transmitted infections. Arch Public Health. 2021;79(1):187. doi: 10.1186/s13690-021-00708-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pelle KG, Rambaud-Althaus C, D'Acremont V, Moran G, Sampath R, Katz Z, et al. Electronic clinical decision support algorithms incorporating point-of-care diagnostic tests in low-resource settings: a target product profile. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(2):e002067. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.WHO . Target product profiles for needed antibacterial agents: enteric fever, gonorrhoea, neonatal sepsis, urinary tract infections and meeting report. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim S, McDougall ARA, Goldstein M, Tuttle A, Hastie R, Tong S, et al. Analysis of a maternal health medicines pipeline database 2000–2021: new candidates for the prevention and treatment of fetal growth restriction. BJOG. 2023;130(6):653–63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.McDougall ARA, Hastie R, Goldstein M, Tuttle A, Tong S, Ammerdorffer A, et al. Systematic evaluation of the pre-eclampsia drugs, dietary supplements and biologicals pipeline using target product profiles. BMC Med. 2022;20(1):393. doi: 10.1186/s12916-022-02582-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDougall AR, Goldstein M, Tuttle A, Ammerdorffer A, Rushwan S, Hastie R, et al. Innovations in the prevention and treatment of postpartum hemorrhage: analysis of a novel medicines development pipeline database. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2022;158(Suppl 1):31–39. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.14200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Foundation C. Accelerating innovation for mothers: pipeline candidates Geneva, Switzerland. Concept Foundation; 2021. Available from: https://www.conceptfoundation.org/accelerating-innovation-for-mothers/aim-pipeline-candidates/.

- 26.Foundation C. Accelerating innovation for mothers: target product profiles Geneva, Switzerland. Concept Foundation; 2021. Available from: https://www.conceptfoundation.org/accelerating-innovation-for-mothers/target-product-profiles/.

- 27.Middleton P, Gomersall JC, Gould JF, Shepherd E, Olsen SF, Makrides M. Omega-3 fatty acid addition during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;11:CD003402. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003402.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi YJ, Shin S. Aspirin prophylaxis during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2021;61(1):e31–e45. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2021.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.WHO recommendations on antiplatelet agents for prevention of pre-eclampsia. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [PubMed]

- 30.van Vliet EOG, Askie LA, Mol BWJ, Oudijk MA. Antiplatelet agents and the prevention of spontaneous preterm birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(2):327–336. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andrikopoulou M, Purisch SE, Handal-Orefice R, Gyamfi-Bannerman C. Low-dose aspirin is associated with reduced spontaneous preterm birth in nulliparous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219(4):399 e1–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Landman A, de Boer MA, Visser L, Nijman TAJ, Hemels MAC, Naaktgeboren CN, et al. Evaluation of low-dose aspirin in the prevention of recurrent spontaneous preterm labour (the APRIL study): a multicentre, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2022;19(2):e1003892. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vahedian-Azimi A, Bianconi V, Makvandi S, Banach M, Mohammadi SM, Pirro M, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the effects of statins on pregnancy outcomes. Atherosclerosis. 2021;336:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2021.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Alwis N, Beard S, Mangwiro YT, Binder NK, Kaitu'u-Lino TJ, Brownfoot FC, et al. Pravastatin as the statin of choice for reducing pre-eclampsia-associated endothelial dysfunction. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2020;20:83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2020.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dobert M, Varouxaki AN, Mu AC, Syngelaki A, Ciobanu A, Akolekar R, et al. Pravastatin versus placebo in pregnancies at high risk of term preeclampsia. Circulation. 2021;144(9):670–79. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Goto E. Effects of prenatal oral L-arginine on birth outcomes: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):22748. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-02182-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Darling AM, McDonald CR, Urassa WS, Kain KC, Mwiru RS, Fawzi WW. Maternal dietary L-arginine and adverse birth outcomes in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186(5):603–611. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Okunade KS, Olowoselu OF, John-Olabode S, Hassan BO, Akinsola OJ, Nwogu CM, et al. Effects of selenium supplementation on pregnancy outcomes and disease progression in HIV-infected pregnant women in Lagos: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021;153(3):533–541. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Monangi N, Xu H, Khanam R, Khan W, Deb S, Pervin J, et al. Association of maternal prenatal selenium concentration and preterm birth: a multicountry meta-analysis. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(9):e005856. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miranda M, Saccone G, Ammendola A, Salzano E, Iannicelli M, De Rosa R, et al. Vaginal lactoferrin in prevention of preterm birth in women with bacterial vaginosis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2021;34(22):3704–3708. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2019.1690445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thornton S, Valenzuela G, Baidoo C, Fossler MJ, Montague TH, Clayton L, et al. Treatment of spontaneous preterm labour with retosiban: a phase II pilot dose-ranging study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83(10):2283–2291. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thornton S, Miller H, Valenzuela G, Snidow J, Stier B, Fossler MJ, et al. Treatment of spontaneous preterm labour with retosiban: a phase 2 proof-of-concept study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;80(4):740–749. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saade GR, Shennan A, Beach KJ, Hadar E, Parilla BV, Snidow J, et al. Randomized trials of retosiban versus placebo or atosiban in spontaneous preterm labor. Am J Perinatol. 2021;38(S 01):e309–e17. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1710034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ali AFM, Fateena B, Ezzeta A, Badawya H, Ramadana A, El-tobge A. Treatment of preterm labor with human chorionic gonadotropin: a new modality - Abstract. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:S61. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lorzadeh N, Dehnoori A, Moumennasab M. Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) versus magnesium sulfate to arrest preterm. Yafteh. 2004;5:41–6. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sakhavar N, Mirteimoori M, Teimoori B. Magnesium sulfate versus hCG (Human Chorionic Gonadotropin) in suppression of preterm labor. Shiraz E-Med J. 2008;9:134–40. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Steinwall M, Bossmar T, Brouard R, Laudanski T, Olofsson P, Urban R, et al. The effect of relcovaptan (SR 49059), an orally active vasopressin V1a receptor antagonist, on uterine contractions in preterm labor. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2005;20(2):104–109. doi: 10.1080/09513590400021144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Simoes-Wust AP, Lapaire O, Hosli I, Wachter R, Furer K, Schnelle M, et al. Two randomised clinical trials on the use of Bryophyllum pinnatum in preterm labour: results after early discontinuation. Complement Med Res. 2018;25(4):269–273. doi: 10.1159/000487431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, Perin J, Rudan I, Lawn JE, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2000–13, with projections to inform post-2015 priorities: an updated systematic analysis. Lancet. 2015;385(9966):430–440. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61698-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.White C. Global spending on health research still skewed towards wealthy nations. BMJ. 2004;329(7474):1064. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7474.1064-e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Petrou S, Yiu HH, Kwon J. Economic consequences of preterm birth: a systematic review of the recent literature (2009–2017) Arch Dis Child. 2019;104(5):456–465. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2018-315778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ilicic M, Zakar T, Paul JW. The Regulation of uterine function during parturition: an update and recent advances. Reprod Sci. 2020;27(1):3–28. doi: 10.1007/s43032-019-00001-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shennan A, Suff N, Leigh Simpson J, Jacobsson B, Mol BW, Grobman WA, et al. FIGO good practice recommendations on progestogens for prevention of preterm delivery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021;155(1):16–18. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.RANZCOG. Progesterone: use in the second and third trimester of pregnancy for the prevention of preterm birth. Melbourne, Australia; Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. 2017.

- 55.American College of O. Gynecologists' Committee on Practice B-O Prediction and prevention of spontaneous preterm birth: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 234. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138(2):e65–e90. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Conde-Agudelo A, Romero R. Vaginal progesterone does not prevent recurrent preterm birth in women with a singleton gestation, a history of spontaneous preterm birth, and a midtrimester cervical length >25 mm. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227(6):923–926. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.07.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Almutairi AR, Aljohani HI, Al-Fadel NS. 17-alpha-hydroxyprogesterone vs. placebo for preventing of recurrent preterm birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Front Med. 2021;8:764855. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.764855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Simhan HN, Bryant A, Gandhi M, Turrentine M, Gynecologists” ACoOa . Updated clinical guidance for the use of progesterone supplementation for the prevention of recurrent preterm birth. Washington: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rumbold A, Ota E, Nagata C, Shahrook S, Crowther CA. Vitamin C supplementation in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;9:CD004072. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004072.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rumbold A, Ota E, Hori H, Miyazaki C, Crowther CA. Vitamin E supplementation in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(9):CD004069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.McCauley ME, van den Broek N, Dou L, Othman M. Vitamin A supplementation during pregnancy for maternal and newborn outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(10):CD008666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Kennedy DA, Lupattelli A, Koren G, Nordeng H. Herbal medicine use in pregnancy: results of a multinational study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13:355. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Heaney RP. Vitamin D–baseline status and effective dose. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(1):77–78. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1206858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shields KE, Lyerly AD. Exclusion of pregnant women from industry-sponsored clinical trials. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(5):1077–1081. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182a9ca67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council. State of paediatric medicines in the EU: 10 years of the EU Paediatric regulation. COM (2017) 626. European Commission; 2017.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Appendix A. Supplementary tables. Table S1. Scoring of target product profile comparison, for quantification of potential of candidates. Table S2. Threshold for ranking of potential at each phase of the R&D development pipeline.

Additional file 2: Appendix B. Low rank candidates.

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. The database generated and analysed during the current study are available at https://www.conceptfoundation.org/accelerating-innovation-for-mothers/.