Abstract

While most parents and healthcare providers understand the importance of educating young people about their emerging sexuality, many report never discussing sex with the young people in their care. Using data from a survey of 1193 emerging adults, we applied concept mapping to a corpus of over 2,350 short qualitative responses to two questions: 1) What, if anything, makes it difficult to talk to your parents about sexuality or your sexual health? and 2) What, if anything, makes it difficult to talk to your doctors, therapists, or mental health professionals about sexuality or your sexual health? Qualitative analyses revealed that while embarrassment, shame and awkwardness were commonly reported barriers to communicating with both parents and providers, participants reported different effects across settings: parent-related embarrassment was associated with concerns about changing the intimacy of the parental relationship, while provider-related embarrassment was associated with fears of seeming incompetent or eliciting dismissal. These observations were supported by multidimensional scaling and hierarchical cluster analyses, which we used to derive conceptual maps based on quantitative spatial analysis of single-concept statements. These analyses revealed a best-fit solution of 8 conceptual groups for barriers to discussing sexuality with healthcare providers, but only 4 groups of barriers in discussing with parents. Broadly, our findings reinforce the need to tailor sexual health communication to patient characteristics and setting.

Keywords: sexuality education, communication, adolescents, doctors, parents

Providing young people with information about sex can prevent significant negative reproductive outcomes and support development of their positive sexual wellbeing (Widman, Choukas-Bradley, Noar, Nesi, & Garrett, 2016; Foshay & O’Sullivan, 2020). Both parents and healthcare providers report awareness of the impact they have on young people’s sexual wellbeing, and aspirations to have conversations with their children or patients about sexuality (Shindel et al., 2010; Henry-Reid et al., 2010; Paiera, 2016; Mullis, 2020). And yet, significant barriers to sexuality communication persist: more than 20% of parents report having never spoken to their children about sexuality (Fisher et al., 2015) and only 35% of adolescent health care visits include discussion about sexuality (Alexander et al., 2014). While much research has investigated the possible barriers to sexuality communication in parent-child (Rogers, 2017) and patient-provider dyads (Fuzzell, Shields, Alexander, & Fortenberry, 2017), most of this research has been “top-down” – that is, driven by (adult) researchers and their perceptions. By ignoring the perspectives of young people, we are likely missing key factors. The present study explored barriers to discussing sexuality with either parents or healthcare providers, using a corpus of over 2,350 qualitative responses in 1,193 young adult participants, centering their voices and concerns to better target interventions to support this critical aspect of health communication. In this study, the term sexuality referred to both sexual identity and its expression in sexual practices.

Lack of sexuality communication contributes to significant health burdens in young people

When parents shy away from talking to their children about sex, they lose the chance to teach about healthy sexual behaviors that prevent risk of sexually transmitted infection or unwanted pregnancy (Coakley et al., 2017; Rogers, 2016; Widman et al., 2019; Widman et al., 2016). More importantly, young people’s sexual wellbeing is profoundly impacted by poor parental communication about sexuality: children of parents who avoid discussing sex have less sexual knowledge (Somers & Paulson, 2000), report greater sexual shame and sexual dysfunction (Widman et al, 2016; Foshay & O’Sullivan, 2020), and are less comfortable communicating with sexual partners about consent or pleasure (Widman et al., 2013). Similarly, when healthcare providers shy from bringing up sexuality in caring for their adolescent and young adult patients, there are a variety of negative outcomes including failure to provide reproductive care to those who are assumed to be sexually inactive or incorrectly assumed to be at low risk for STIs (Sulak et al., 2005; Tabaac et al., 2021), missed opportunities to intervene in sexual problems before they become serious sexual dysfunctions (O’Sullivan et al., 2016), and failure to support adherence to treatments with sexual side effects (Lorenz, 2020a).

Prior research has found that key barriers to parent-child communication about sexuality include limited parental sexual knowledge; parental beliefs that young people are not ready to learn about sex; discomfort; and cultural factors such as gender, race, and religion (Malacane & Beckmeyer, 2016). In the case of healthcare providers, barriers include personal discomfort; perceiving their patients to have a limited knowledge base; and issues establishing confidentiality (Lung et al., 2021).

Centering young adult voices in understanding barriers to discussing sexuality

Most of the research on barriers to discussing sexuality in young people has used fixed sets of questions in surveys or structured interviews (Widman et al., 2016). While these methods can gather data quickly and can include a wide diversity of participant identities, those data are limited by what questions researchers choose to include, which are determined by the (adult) researcher’s perspectives and understanding of the issue. At the other extreme, traditional in-depth qualitative analyses (such as interviews or focus groups) can capture rich depth on young people’s perspectives on the most important barriers to communication. However, qualitative methods require significant time investments from both researchers and participants, necessitating smaller samples to focus on just a few voices at a time. There is a limit to how diverse a small sample can be.

A compromise between these two extremes lies in open-ended short form responses embedded within online surveys (Pietsch & Lessmann, 2018) or via texting (Walsh & Brinker, 2016). There are several methods to assess short form data, including concept class analysis (Taylor & Stultz, 2020), and text mining or word count analyses (Pietsch & Lessmann, 2018). For our study, we used a set of voluntary free-response questions embedded in a larger quantitative survey of sexual attitudes and mental health history. By not requiring an answer to these items to complete the survey, we were able to avoid some social desirability effects while capturing whatever thoughts are at the forefront of participants’ minds at the time they were taking the survey. Our analytic method, concept mapping, also allowed us to not only examine the themes, but also the structure and organization of those themes as sources of information about the barriers.

Our free response questions engaged two different contexts for sexuality communication: with parents and with providers. As noted above, prior research has identified different barriers in each context. Also, there is reason to expect significant differences in the nature of the relational context: for providers, contact with patients is infrequent and short with narrowly defined goals; for parents, contact with children is more frequent but potentially more subtle, covering both practical and emotional components of sexual behaviors, and the transmission of cultural norms around sexuality.

The primary aim of this analysis was to examine the differences in young adults’ reported barriers to communication between parent-child and patient-provider contexts, both in terms of the narrative components of participants’ responses (i.e., using qualitative analysis methods), and in the structure of how those themes were grouped via scaling analysis (i.e., using quantitative analysis methods). As an additional exploratory analysis, we tested how the clusters identified in our qualitative analyses differed across demographic groups – that is, how different groups experienced unique barriers.

Method

Data Collection

We used data from an online survey of a convenience sample of 1193 undergraduates at two universities in the Southeastern and Midwestern United States. Participants were recruited from Psychology participant pools and received course credit for their participation; all participants indicated their informed consent. Institutional Review Board approval was granted by University of North Carolina at Charlotte and University of Nebraska Lincoln. Surveys were conducted from 2016 – 2019 and pooled across multiple waves. Each wave of the survey took approximately 60 minutes to complete and contained some core questions (including the free response questions used here) as well as modifications across waves for other variables including sexual and relationship development, mental and physical health history, and sexual attitudes and behaviors (see the following for analyses of these other variables: Lorenz, 2019; Lorenz, 2020a; Lorenz, 2020b; Lorenz, 2020c; Sartin-Tarm, Clephane & Lorenz, 2021).

Participants

The sample included here had an average age of 19.95 (SD = 2.93). There were 72% of participants who identified as women and 27% as men, with fewer than 1% of the dataset identifying with another gender (e.g., nonbinary, genderqueer). A majority (68%) of the sample was characterized as heterosexual (see below for details), with 29% as mostly heterosexual or bisexual, and 3% with a different sexual orientation (e.g., lesbian/gay; asexual). Although this was a majority non-Hispanic white sample (66%), 10% of respondents identified as non-Hispanic Black, 9% as mixed race, 7% as non-Hispanic Asian, and 6% as Hispanic of any race.

Measures

Demographics

Participant demographics were obtained via a series of self-report questions; see Table 4 for summary. Participants were asked to indicate their sex/gender1, relationship status, religious affiliation in their family of origin, and race/ethnicity using established categorical choices, or to select “other” and provide a free-response answer. Age was measured via free response and was continuous. The highest level of education their primary caregiver(s) had received was used to approximate socioeconomic status (SES).

Table 4:

Demographics of study sample.

| Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 19.97 | 2.97 |

| Gender typicality | 91.20 | 23.21 |

| Heritage Acculturation | 15.10 | 3.76 |

| Mainstream Acculturation | 16.26 | 3.82 |

| Religiosity Total | 8.15 | 3.86 |

| Number (N) | Percentage (%) | |

|

| ||

| Racial/ethnic identity | ||

| Black/African American | 117 | 9.81% |

| Asian | 86 | 7.21% |

| white | 849 | 71.17% |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 68 | 5.70% |

| Multiracial/Other | 11 | 0.92% |

| Missing/Not Answered | 62 | 5.20% |

| Gender/sex | ||

| Female | 823 | 68.99% |

| Male | 311 | 26.07% |

| Other/Not Answered | 59 | 4.94% |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Exclusively heterosexual | 778 | 65.21% |

| Mostly heterosexual | 177 | 14.84% |

| Bisexual | 153 | 12.83% |

| Other/Not Answered | 85 | 7.12% |

| Parental SES | ||

| High school degree | 134 | 11.23% |

| College or technical degree | 640 | 53.65% |

| Graduate degree | 360 | 30.18% |

| Not Answered | 59 | 4.94% |

| Religion in family of origin | ||

| Protestant | 268 | 22.47% |

| Evangelical | 170 | 14.25% |

| Non-denominational Christian | 130 | 10.90% |

| Catholic | 358 | 30.00% |

| Other | 70 | 5.87% |

| None/Agnostic | 47 | 3.94% |

| Atheist | 92 | 7.71% |

| Not Answered | 58 | 4.86% |

Religiosity

Participants were asked to indicate their religiosity using three items assessing the importance of religious service attendance (indexing extrinsic religiosity), prayer or personal religious ritual (indexing intrinsic religiosity) and spirituality. These items were chosen for their relevance to the development of sexual attitudes in young people (Ahrold & Meston, 2010; Ahrold, Farmer, Trapnell, & Meston, 2011). Participants were presented with five options on a rating scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 5 (extremely important). Religiosity was calculated as a total sum of these three questions.

Acculturation

Acculturation was measured using six items adapted from the Vancouver Index of Acculturation (Ryder, Alden, & Paulhus, 2000). This well-validated scale measures degree of identification with heritage and mainstream cultures, allowing consideration of a variety of acculturative systems (e.g., assimilation, enculturation, biculturalism). Items asked participants to rate their agreement with statements about the importance of different cultures to their identity on a Likert response scale, ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 7 (strongly disagree).

Gender typicality

To assess gender typicality, participants were asked to indicate their gender identity as masculine/male and feminine/female using sliders that ranged from 0 (not at all) to 100 (very strongly). From these data and the participants reported sex/gender assigned at birth, we constructed a continuous variable to characterize participants’ gender typicality, subtracting the value for the gender that would be cis-atypical for their sex/gender category from that which would be cis-typical. For example, if a participant identified their sex/gender as female, and indicated identification as 80% feminine and 20% masculine, they would receive a score of 60% gender typical. Thus, rather than being a direct measure of masculine or feminine identity per se, this measure provided a rough approximation of participants alignment with traditional gender norms for the sex they were assigned at birth.

Sexual orientation

To assess sexual orientation and attraction, participants were asked to indicate their orientation to men/masculine people, women/feminine people, and gender non-binary people. As with gender typicality, they were presented with sliders from 0% (no interest/orientation) to 100% (strong interest/orientation) and were instructed to select responses to each category independently (i.e., the total did not have to add up to 100%). Following other studies, for ease of interpretation we used these data to characterize participants as heterosexual, mostly heterosexual, bisexual, gay/lesbian, asexual, or other (Lorenz, 2019). This method has been shown to capture non-heterosexual orientation in participants who might not identify as a sexual minority when presented with categorical options (Lorenz, 2021).

Free Response Questions

Free response questions were worded as follows: (1) What, if anything, makes it difficult to talk to your parents about sexuality or your sexual health? and (2) What, if anything, makes it difficult for you to talk to your doctors, therapists, or mental health professionals about sexuality or your sexual health? Participants were free to skip any question that they wished; however, approximately one half (49%) of respondents wrote something for at least one question with 47% responding to both questions.

Coder Expertise and Positionality

The coding team consisted of 7 researchers. The team included two undergraduate research assistants, three masters-level graduate research assistants, a post-baccalaureate lab manager, and a doctoral researcher who served as a project consultant. Researchers were 5 cisgender women, one genderqueer person and one nonbinary person; the team endorsed a range of sexual orientations. The research team was majority white, and the lead researcher (SS) is non-white Latina. All researchers worked in a university laboratory specializing in women’s sexual and reproductive health, had backgrounds in psychology research, and most had prior experience analyzing qualitative data. A senior sexual health researcher consulted on project methods and thematic organization (TKL).

Concept Mapping Procedures

Overview

Whereas content analysis has been criticized for relying on researcher-driven classification schemes, allowing interdependence between coders, and offering relatively weak reliability and validity assessments (Kelle & Laurie, 1995; Krippendorff, 1980; Weber, 1990), concept mapping blends the open-endedness of qualitative content analysis with the reliability of quantitative approaches. Concept mapping both enables human researchers to use their judgment to initially sort responses based on thematic similarities and incorporates statistical analysis as a basis for the final organizational decisions. Concept mapping has previously been used to explore the sexual and reproductive health needs of Jordanian and Syrian youth (Gausman et al., 2020) and young women with Cystic Fibrosis (Kazmerski et al., 2019), as well as community responses to rape (Campbell & Salem, 1999).

We adapted concept mapping procedures from Jackson and Trochim (2002). These methods provide an alternative mechanism to code-based and word-based text analysis for organizing and contextualizing responses to open-ended survey questions. They describe five core steps: (a) create units of analysis, (b) sort units into groups of similar concepts, (c) run a quantitative multidimensional scaling (MDS) analysis on the group-sorted data, (d) run a cluster analysis on the MDS coordinates to identify and decide upon cluster solutions, and (e) qualitatively label the clusters.

Data preparation into units of analysis

The lead researcher first created a set of specific rules for the coding team (e.g., differentiating between the words “and” / ”or”; using periods and commas to separate units of analysis); see Table 1 for all coding rules. She sorted open-ended responses into individual statements, creating two corpuses of statements describing barriers in communication with parents (n = 1,434 statements) and those describing providers (n = 919). Following best practices for concept mapping (Jackson & Trochim, 2002), individual participants could have provided multiple statements if parts of their written response were separated based on periods, commas, or introduction of a new barrier (e.g., use of “and” to indicate a new exemplar). For example, the raw data included the statement: “It’s not difficult, it’s just that it’s not worth the time and effort to do so. Makes things awkward due to my upbringing and the way they interact with me.” This same cleaned statement resulted in three separate units for analysis: (1) It’s not difficult, it’s just that it’s not worth the time and effort to do so; (2) Makes things awkward due to my upbringing; (3) Makes things awkward due to the way they interact with me.

Table 1:

Step one concept mapping rule

| Type of Statement | Rules |

|---|---|

| One word statements | - Lifted straight from dataset - Edited for clarity if needed |

| Multiword statements separated by commas, “and”, or “or” | - Split up into multiple statements as designated by commas - Repeated syntax if needed for clarity - Removed filler words unnecessary for meaning |

| Multiword statements separated by “but” | - Kept as one statement - Edited for clarity and shortness - Removed filler words unnecessary for meaning |

| Multi-sentence statements | - Used rules above for each sentence - Kept sentences together if they are a continuation of a single thought |

We considered blank responses and active non-answers (e.g., responses in which participants deliberately wrote “N/A”, or “not applicable”) as potentially relevant and thus retained them both in cluster analyses and exploratory quantitative analyses. This arose out of consideration of the conceptual difference between leaving an item completely blank (as in the X answers) and actively taking time to write out “not applicable” or “choose not to respond” (as in the “N/A” answers). The former likely indicates lack of engagement with the questions – likely, a desire to be done with the survey faster. The latter suggests unwillingness or discomfort in reporting on one’s thoughts about sexuality to a set of researchers, which potentially reflects the very phenomenon of interest. As such, the presence of these categories allows us to account for the effects of participant apathy and apprehension when being questioned about their role in sexuality conversations – both of which may be meaningful elements when planning educational interventions.

Data sorting

The seven raters were provided a spreadsheet of all data points already cleaned by the head researcher, as well as a blank labeling document in which to create theme names and assign statement IDs to individual researcher-created themes. Raters were instructed to read through the statements and sort similar statements together into whatever thematic groups made sense to them; raters were allowed (and encouraged) to re-sort previously grouped data as new themes emerged during their individual analyses. The only restriction was that there could be no “miscellaneous” category; all themes had to have a unique meaning. Categorization was not mutually exclusive, meaning that raters could categorize a single statement in multiple theme groups. For example, for the parent question, the number of categories across raters ranged from 29 to 57, with a mean of 41 across all seven raters. At the end of the initial sort, all raters met to discuss their themes and interpretation of the data; however, this was not a consensus meeting and differences between raters could (and did) persist. Following this meeting, raters were asked to finalize their sorts and return their grids for each question to the lead researcher.

Multidimensional scaling analyses

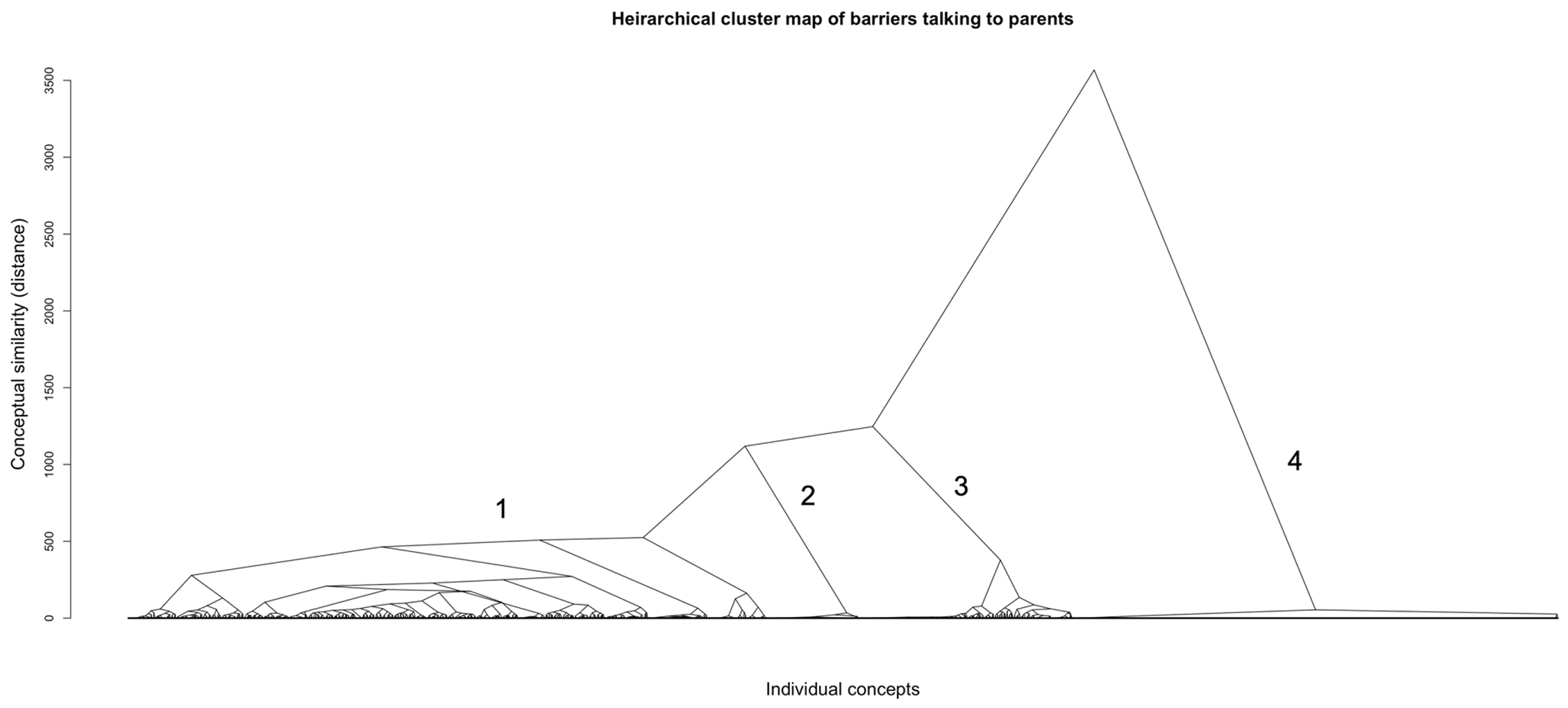

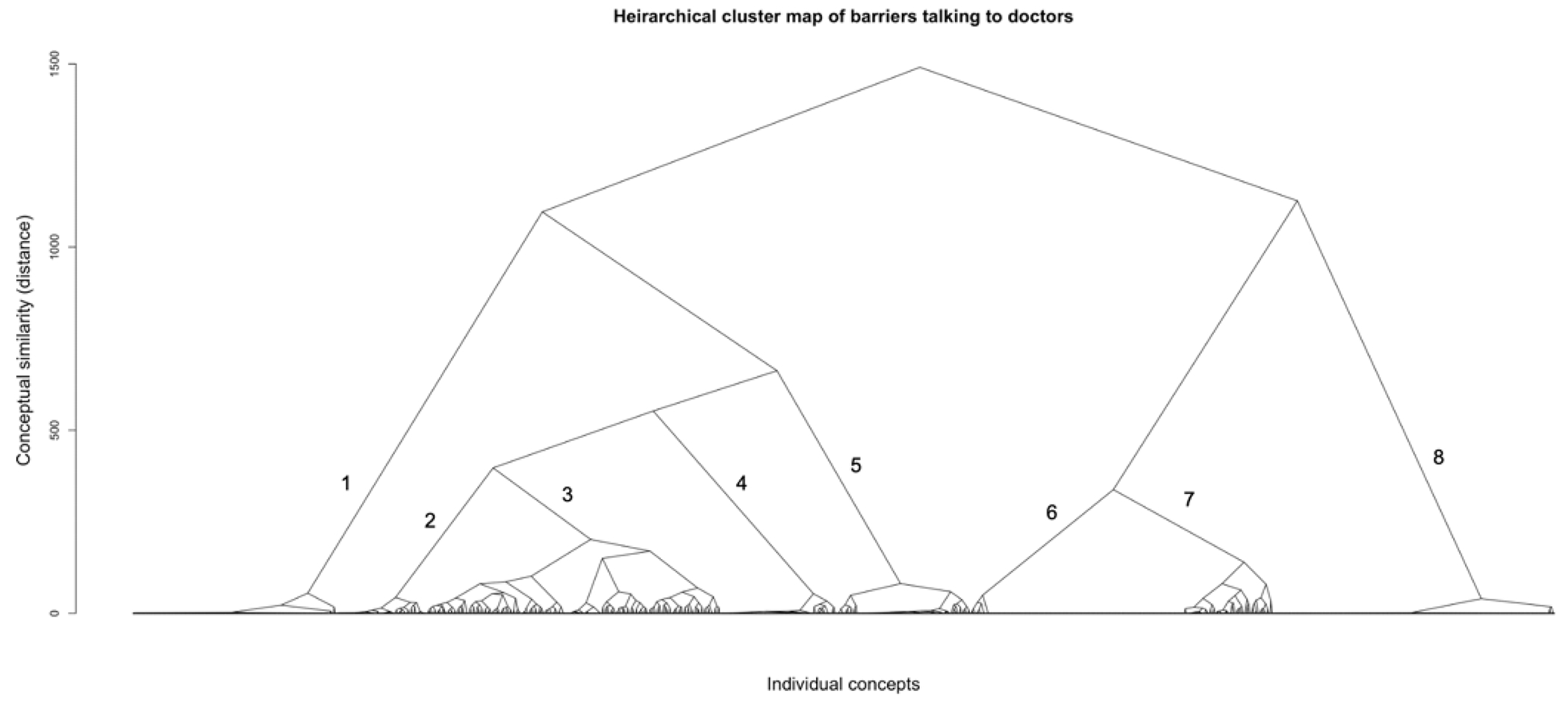

Following confirmation of rater’s final sorts, we then generated sort matrices for each rater and question. Each single-concept unit was represented as a column and row in a matrix. If two concepts were sorted into the same category, the corresponding cell in the matrix was coded as 1, otherwise as 0. These matrices were added together across raters to create an index of the aggregate similarity between concepts. We then generated a dendrogram of the aggregated matrices to spatially represent the similarity between concepts (Figures 1 and 2). In these figures, distance reflects how often two concepts were sorted into the same groups: concepts that were often sorted together are “closer” while those that were rarely sorted together are “further”. Cluster linkages (presented as branching lines between concepts and groups of concepts) were created iteratively, first grouping together close individual concepts, then close groups of concepts, then close groups of groups and so on, creating a hierarchical concept map of themes and subthemes. The height of each cluster represents the distance between concepts (or groups of concepts) at the time they were clustered – that is, the degree of conceptual similarity. Given the large number of concepts for each question, the individual concept IDs would not readable and have been replaced with dots for presentation; however, these cluster graphs give a sense of the degree of complexity of each cluster and how many subthemes are represented within. For example, in Figure 1, cluster 1 includes one subtheme with many individual concepts that were all very close, representing high agreement on the similarity of these concepts. In contrast, cluster 3 includes a wide range of subthemes, indicating that although raters tended to group these concepts together overall, there were individual differences across raters in precisely how they fit together. In other words, cluster 1 was discrete and well-defined, while cluster 3 was more complex and diffuse.

Figure 1:

Hierarchical cluster map of barriers in talking to parents

Figure 2:

Hierarchical cluster map of barriers in talking to doctors

Cluster analysis

Although the multidimensional scaling analyses help visually represent how concepts fit together, it does not determine the final number of clusters to best describe the overall patterns in the data. Following Jackson & Trochim (2002), we conducted hierarchical agglomerative cluster analyses using the agnes package in R, specifying the Wald algorithm method. These analyses were then plotted in elbow and silhouette plots using the facto_extra package to evaluate optimal-fit cluster solutions, balancing cluster complexity with overall model parsimony.

Labeling and interpreting the clusters

Finally, we examined the concepts that had been clustered together to identify the overarching themes and subthemes that had been identified in multidimensional scaling and hierarchical cluster analyses.

Exploratory Quantitative Analysis Plan

Using the thematic clusters developed during the concept mapping analyses, we explored how different barriers differentially impacted participants across demographic variables. Specifically, we conducted a series of logistic regression models with each cluster as the dependent variable, dummy coded 0 or 1, and ten predictor variables: age, parental education (as a marker for socioeconomic status), gender/sex category, sexual orientation, gender typicality, racial/ethnic identity, mainstream and heritage acculturation, religion in family of origin, and degree of religiosity. It should be noted that these analyses were atheoretic and should be considered purely exploratory. That said, because these categories reflect voluntary and spontaneous reports, when there were significant differences, it indicates that topic was sufficiently at the forefront of the mind of participants from that group that they went out of their way to report it. As such these findings point to particularly fruitful areas for future research.

Results

Cluster analyses

The final cluster solution supported by hierarchical analyses differed across the communication context. For data regarding barriers talking to providers, both elbow and silhouette plots clearly indicated an optimal fit at eight clusters. Following a close reading of the responses within these clusters, we labeled these clusters as following: X (blank answer), Judgment, It’s Not Difficult, Fear, Awkwardness, Embarrassment, Nothing, and Lack of Trust (see Table 2 of exemplars and response rates). For data regarding barriers talking to parents, the plots indicated optimal fit at either two or four clusters; as the two cluster solution would create groups that were too broad to interpret, we decided on the four cluster solution. Based on the content of these clusters, we chose the following labels: Shame and Cultural Values, Awkwardness, X (blank answer), and N/A (see Table 3 of exemplars and response rates).

Table 2:

Identified clusters of barriers to discussing sexuality with parents, with exemplars by group

| CLUSTER LABEL | EXEMPLAR(S) | NUMBER OF RESPONSES IN CLUSTER |

|---|---|---|

| SHAME & CULTURE | - “Very conservative, traditional family that does not believe in sex before marriage.” - “My mom comes from a very conservative Catholic household which makes the topic of sex almost forbidden in my house.” - “They would understand what I’m talking about because they are from a culture that doesn’t do this stuff regularly.” |

605 |

| N/A |

- “N/A” - “Choose not to respond” |

88 |

| DISCOMFORT | - “It is not something that was ever commonly spoken about. It isn’t that I feel I wouldn’t be able to go to them, just that I’m uncomfortable with it, so I don’t. It just seems taboo.” - “It’s just awkward to bring up.” |

202 |

| X (BLANK) | - “X” (response left blank, participant clicked through to next question) | 460 |

Table 3:

Identified clusters of barriers to discussing sexuality with healthcare providers, with exemplars by group

| GROUP | EXEMPLAR(S) | NUMBER OF RESPONSES IN CLUSTER |

|---|---|---|

| JUDGMENT | - “I feel that I will be judged for my sexual habits.” - “I feel worried and/or embarrassed that they will tell me I am doing something wrong.” - “Their facial expressions.” |

121 |

| IT’S NOT DIFFICULT | - “It’s not difficult for me; they know what they’re talking about and will not judge me.” - “It’s not difficult for me; I like to be as honest as possible with my doctors.” |

54 |

| FEAR | - “Fear of sounding dumb.” “I get worried they will tell my parents.” |

127 |

| AWKWARDNESS | - “Awkwardness due to age gap.” - “There’s always something about the professional that makes me feel uncomfortable.” |

175 |

| EMBARRASSMENT | - “It’s embarrassing.” - “Embarrassment. |

69 |

| NOTHING | - “Nothing.” - “None” |

80 |

| LACK OF TRUST | - “Talking to someone you don’t know that well.” - “They are unfamiliar, so visits are impersonal.” - “Because you don’t have a deep connection with them.” - “I get worried they will tell my parents since I still go to a pediatrician.” |

53 |

| X (BLANK) | - “X” (response left blank, participant clicked through to next question) | 168 |

Results of exploratory demographic analyses

A full summary of the results across all exploratory quantitative analyses is presented in Tables 5 and 6. These analyses revealed some significant differences in the kinds of barriers identified by different demographic groups. In the context of talking to doctors, gender/sex was a significant predictor of responses in the Judgement, Not Difficult, and Embarrassment categories; acculturation a predictor of Not Difficult, Fear, and Embarrassment categories; religion a predictor of X (non-response), Embarrassment, and Lack of Trust categories; sexual orientation a predictor of Lack of Trust and Embarrassment categories; age and gender typicality predictors of the Nothing category; and parental SES predicted responses in the Fear category. In the context of talking to parents, both sexual orientation and religion were significant predictors of responses in the Shame and N/A categories. Also, gender/sex, gender typicality, and acculturation were all significant predictors of responses to the Shame category in the parental context. Each of these findings is discussed below.

Table 5:

Differences between demographic groups in barriers discussing sexuality with healthcare providers

| Thematic clusters Effect Estimate (Std. Error) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | X | Judgement | Not Difficult |

Fear | Awkwardness | Embarrassment | Nothing | Lack of Trust | |

| Continuous predictors | |||||||||

| Age | 0.003 (0.040) | 0.040 (0.050) | 0.011 (0.035) | −0.022 (0.041) | −0.162 (0.088) | −0.037 (0.048) | 0.087 (0.046)* | 0.039 (0.033) | |

| Gender Typicality | 0.002 (0.006) | −0.002 (0.008) | 0.012 (0.008) | −0.005 (0.005) | −0.005 (0.007) | 0.012 (0.008) | −0.019 (0.007)*** | −0.002 (0.006) | |

| Heritage Acculturation | −0.046 (0.035) | −0.002 (0.050) | 0.010 (0.035) | 0.018 (0.032) | −0.013 (0.042) | 0.074 (0.044)* | −0.049 (0.052) | −0.024 (0.030) | |

| Mainstream Acculturation | 0.020 (0.034) | 0.030 (0.049) | 0.065 (0.035)* | −0.056 (0.030)* | 0.007 (0.040) | −0.001 (0.039) | 0.002 (0.005) | −0.019 (0.028) | |

| Religiosity total | −0.011 (0.033) | −0.083 (0.051) | 0.015 (0.031) | −0.046 (0.031) | 0.009 (0.040) | −0.017 (0.039) | −0.725 (0.005) | 0.040 (0.028) | |

| Categorical predictors | |||||||||

| Parental SES (reference group: ≤ High school degree) | College or technical degree | −0.242 (0.350) | 0.046 (0.544) | 0.103 (0.380) | −0.519 (0.308)* | 0.554 (0.515) | 0.462 (0.489) | 1.12 (0.779) | −0.100 (0.339) |

| Graduate degree | −0.648 (0.399) | 0314 (0.579) | 0.278 (0.402) | −1.006 (0.356)*** | 0.253 (0.551) | 0.587 (0.512) | 1.013 (0.819) | 0.370 (0.353) | |

| Gender/sex (reference group: Female) | Male | 0.281 (0.252) | −1.922 (0.618)*** | 0.518 (0.232)** | −0.253 (0.241) | −0.441 (0.328) | 0.750 (0.283)*** | 0.054 (0.402) | −0.371 (0.228) |

| Sexual Orientation (reference group: Heterosexual) | Bisexual | 0.233 (0.351) | −0.053 (0.528) | 0.020 (0.381) | 0.0399 (0.305) | −0.388 (0.459) | 0.975 (0.401)** | 0.414 (0.483) | −0.926 (0.362)** |

| Mostly heterosexual | −0.259 (0.346) | 0.379 (0.411) | −0.044 (0.311) | 0.055 (0.288) | −0.619 (0.434) | 0.695 (0.345)** | −0.019 (0.500) | −0.055 (0.265) | |

| Other | 0.861 (0.879) | 0.598 (1.156) | −0.088 (1.133) | 0.643 (0.789) | N/A | 1.243 (1.142) | N/A | N/A | |

| Race (reference group: white) | Non-white | −0.355 (0.294) | −0.291 (0.422) | 0.098 (0.293) | 0.419 (0.271) | 0.095 (0.365) | −0.101 (0.334) | −0.415 (0.434) | 0.085 (0.264) |

| Religion in family of origin (reference group: Protestant) | Evangelical | −0.783 (0.395)** | 0.156 (0.527) | 0.542 (0.359) | 0.260 (0.351) | 0.029 (0.501) | 0.044 (0.509) | −0.534 (0.619) | −0.054 (0.343) |

| Non-denominational Christian | −0.477 (0.391) | −0.425 (0.593) | −0.025 (0.411) | 0.320 (0.366) | 0.403 (0.485) | 0.453 (0.489) | 0.121 (0.549) | −0.072 (0.352) | |

| Catholic | −0.963 (0.338)*** | −0.349 (0.471) | 0.306 (0.312) | −0.106 (0.313) | 0.343 (0.400) | 0.550 (0.401) | −0.148 (0.483) | 0.215 (0.272) | |

| Other | −0.242 (0.506) | −0.450 (0.853) | 0.551 (0.514) | 0.523 (0.474) | −0.290 (0.825) | 0.335 (0.651) | −1.213 (1.108) | −0.220 (0.517) | |

| None/Agnostic | −0.180 (0.572) | 0.455 (0.769) | 0.468 (0.581) | 0.169 (0.589) | 0.985 (0.665) | 1.23 (0.632)* | N/A | −2.060 (1.056)* | |

| Atheist | −0.604 (0.467) | −1.343 (0.844) | −0.189 (0.518) | −0.071 (0.429) | 0.695 (0.557) | 0.485 (0.529) | −0.167 (0.752) | 0.524 (0.393) | |

Note: Cells with N/A indicate there were no participants in that demographic group who endorsed that thematic cluster.

p < 0.001 is indicated by ***;

p < 0.01 is indicated by **;

p < 0.05 is indicated by *

Table 6:

Differences between demographic groups in barriers discussing sexuality with parents

| Thematic clusters Effect Estimate (Std. Error) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Shame | Awkward | X | N/A | |

| Continuous predictors | |||||

| Age | 0.043 (0.031) | −0.080 (0.044)* | 0.005 (0.044) | 0.002 (0.039) | |

| Gender Typicality | 0.009 (0.005)** | −0.008 (0.005) | 0.002 (0.007) | (−0.005) (0.006) | |

| Heritage Acculturation | 0.054 (0.026)** | −0.037 (0.029) | −0.059 (0.038) | −0.000 (0.035) | |

| Mainstream Acculturation | −0.016 (0.025) | 0.020 (0.027) | 0.038 (0.039) | −0.019 (0.032) | |

| Religiosity total | −0.015 (0.024) | 0.010 (0.027) | −0.018 (0.038) | 0.047 (0.031) | |

| Categorical predictors | |||||

| Parental SES (reference group: ≤ High school degree) | College or technical degree | 0.267 (0.280) | 0.293 (0.326) | −0.281 (0.391) | −0.516 (0.357) |

| Graduate degree | 0.488 (0.301) | −0.111 (0.352) | −0.719 (0.451) | −0.170 (0.373) | |

| Gender/sex (reference group: Female) | Male | −0.379 (0.187)** | 0.310 (0.203) | 0.268 (0.281) | −0.319 (0.260) |

| Sexual Orientation (reference group: Heterosexual) | Bisexual | 1.548 (0.204)**** | −0.887 (0.347) | −0.052 (0.414) | −1.361 (0.478)*** |

| Mostly heterosexual | 0.493 (0.230)** | −0.165 (0.258) | −0.648 (0.428) | −0.065 (0.299) | |

| Other | 2.402 (1.127)** | −14.840 (500.387) | N/A | −0.392 (1.155) | |

| Race (reference group: white) | Non-white | −0.033 (0.221) | 0.179 (0.252) | −0.265 (0.333) | 0.049 (0.300) |

| Religion in family of origin (reference group: Protestant) | Evangelical | 0.618 (0.290)** | −0.088 (0.323) | −0.300 (0.437) | −0.768 (0.451)* |

| Non-denominational Christian | 0.230 (0.298) | −0.184 (0.346) | −0.170 (0.446) | −0.030 (0.398) | |

| Catholic | −0.015 (0.236) | 0.352 (0.257) | −0.531 (0.376) | 0.215 (0.306) | |

| Other | 0.515 (0.414) | −0.488 (0.511) | 0.185 (0.554) | −0.117 (0.566) | |

| None/Agnostic | 0.473 (0.465) | 0.022 (0.531) | 0.436 (0.596) | −1.666 (1.062) | |

| Atheist | −0.567 (0.4354) | 0.322 (0.388) | −0.732 (0.606) | 0.749 (0.433)* | |

Note: Cells with N/A indicate there were no participants in that demographic group who endorsed that thematic cluster.

p < 0.001 is indicated by ***;

p < 0.01 is indicated by **;

p < 0.05 is indicated by *

Discussion

A critical step to improving sexual health outcomes in young people is understanding their perception of the barriers they face in communicating about their sexuality. Much work that has aimed to identify such barriers has been researcher-driven rather than stemming from the experiences of young people themselves. On the other hand, although there is a rich literature of qualitative studies that center young people’s concerns, these studies are limited in the number of perspectives that can be incorporated into their theory building. In the present study, we used a mixed-methods content mapping approach to identify themes in a large corpus of young people’s brief responses to questions assessing barriers to communicating with parents and with healthcare providers about their sexuality. Our data revealed differences in barriers reported across parental vs. healthcare contexts, both in terms of the content of those themes, and the structure of the concept maps. In general, fear of judgement, shame and embarrassment were common themes, albeit with different expressions across contexts.

Structural differences in concept maps for barriers talking to parents vs. healthcare providers

There was considerable difference in the stability and complexity of content clusters across the two settings: young people’s perceptions about barriers to communicating with healthcare providers were much more concrete and clearly defined than were perceptions of barriers to communicating with parents. That is, our participants described the barriers to communicating with providers in a way that was more readily recognized as falling into discrete categories by our seven raters, while their descriptions of barriers to talking with their parents about sex were considerably more ambiguous, leading to more diversity of categorization. This in turn led to fewer, but more diffusely organized, concept clusters emerging for the reported barriers in discussing sexuality with parents. There were more, and more distinct, concept clusters for barriers in discussing sexuality with providers. It is possible that these concept maps reflect greater actual agreement among young people as to the nature of the barriers in discussing sexuality with healthcare providers. This agreement may arise out of a shared experience of attempting, or at least recognizing the possibility of attempting, such conversations with healthcare providers – but not one’s parents. A compelling theme in the providers context was how young people recognized the need to communicate with their healthcare providers about sexuality, even when it was difficult; in contrast, several participants expressed confusion or disgust at the mere idea of talking to their parents about sex. For example, one participant responded “they’re my parents, you know? Natural grossed out feelings occur every time it gets brought up”. Thus, these differences may reflect that young people had actually attempted communication about sex with their providers and were able to articulate barriers to that communication more easily.

It is also worth noting that in this university sample, all participants had access to the same healthcare provider (namely, the student health center) while everyone’s family system is unique. Broader social narratives about what makes it hard to discuss sexuality with one’s providers (from which our participants may have drawn) may be more likely shared across young people, as these narratives are constructed around an external institution. Likewise, the relative similarity in instruction across medical institutions and dearth of sexuality education therein could contribute to such shared narratives. On the other hand, the diverse range of cultural backgrounds and family dynamics around parent-child communication may introduce many kinds of barriers, each as unique as that family, leading to more disagreement across participants. But, as with the provider context, negative social accounts of “the talk” as a necessarily uncomfortable rite of passage may play a part in the statements of awkwardness provided by our participants.

It is also possible that, as raters, the range of our cultural backgrounds may have contributed to different interpretations of the responses to the parent question, while our shared interest and experience in healthcare may have created more alignment of interpretation of the data on providers. Either way, the greater diffuseness of structure in the concept map for barriers in talking to parents about sexuality would reflect the wider diversity of values and relationship styles across families that would influence such conversations. As such, our findings suggest that research on sexual health communication with parents may particularly benefit from a multidimensional model that incorporates a diversity of possible barriers, rather than a narrow focus on individual factors. Moreover, these findings point to the strong need to tailor interventions that support parents in learning to discuss sexuality with their children. While the idea that interventions to build parent-child communication should incorporate the cultural values of different ethnic or racial groups is not controversial (Prado & Pantin, 2011), our findings underscore the value of considering the unique dynamics of individual families.

Differences in reported barriers across demographic groups

Our exploratory analyses examined possible demographic differences in the barriers reported. As our sample has limited diversity in several key dimensions (e.g., relatively few trans participants or participants of color), these findings should be interpreted with caution. Nevertheless, they point to possible points of resilience and vulnerability in certain groups that are worth investigating further.

Age

Younger respondents were more likely to report awkwardness as a barrier in parent-child contexts and were significantly less likely to report “nothing” as a barrier in medical contexts. This may reflect a relative lack of sexual experience; a review of sexual behaviors in the US found that most men and women aged 15 – 19 reported 0 – 1 lifetime sexual partners, with trajectories of number of partners diverging around age 20 (Haderxhanaj et al., 2014). Lack of experience may foster a sense of insecurity when speaking to (presumably) more knowledgeable adults, like parents and doctors. Indeed, many of our respondents noted the knowledge differential contributed to their hesitancy when communicating about sex, especially with doctors (e.g., “Talking about sex in general makes me uncomfortable. I’m scared I’ll be judged because of my inexperience”). However, although many of our younger participants reported awkwardness, this did not necessarily deter them from conversations with medical providers (e.g., “We are inexperienced and I would much rather the doctors talk about sexuality and mental health because I don’t really know what I’m doing and I don’t have any knowledge except the experiences I’ve encountered”). There is also evidence that as young people age, they turn to friends for a wider range of sexuality information (Widman et al., 2013; Sartin-Tarm et al., 2021); possibly, awkwardness discussing sex decreases if one can be choosier about which sexuality topics to discuss with parents.

Socioeconomic status (SES)

Participants with lower parental SES were significantly more likely to relate fear as a barrier to communication about sex with their medical providers. Participants who come from higher SES backgrounds may have better access to a wider range of providers, allowing them to find providers who have more training with a diverse range of patient populations. As higher SES is associated with greater time spent on patient questions and education during provider visits (Fiscella, Goodwin, & Stange, 2002), it is also possible that this finding reflects the effects of time spent allaying participant fears. One study of adolescents found that for every minute longer in a healthcare visit, there was a 6% increased likelihood of adolescents talking about sexuality with their provider (Alexander et al., 2014). Other research on physician biases finds that physicians perceive their higher SES patients to be more “independent, responsible, intelligent, compliant, and rational” than their lower SES patients (van Ryn & Burke, 2000), suggesting that participants from higher SES backgrounds may have providers who treat them as mature enough to discuss sexuality.

Gender/sex

Relative to female participants, the male participants in our sample were significantly less likely to report feeling judged by their providers when talking about sex, and more likely to report no difficulty. This is in keeping with other work showing that while physicians are more likely to bring up sexual health topics (such as contraception) in visits with adolescent female patients (Fuzzell, et al., 2017), they are specifically more likely to bring up negative consequences of sex (e.g., sexually transmitted infection; unwanted pregnancy; Fuzzell, et al., 2017). In the US, social norms for male adolescents’ sexual activity are not nearly as negatively centered as they are for adolescent females. It is thus not surprising that adolescent females are more uncomfortable bringing up sexuality with their providers (Fuzzell, et al., 2017), and in our sample, more likely to feel judged.

Gender atypicality

Interestingly, we found that degree of gender atypicality was associated with significantly higher likelihood of reporting a lack of barriers in talking to physicians and lower likelihood of reporting feelings related to shame in the parental context. As with other groups endorsing a lack of difficulty across both contexts, the literature supports the idea that gender diverse people are more likely to get their sexual information from a variety of sources, which in turn could lead to greater comfort with communicating about sexuality overall. Several studies have found that, relative to cis-hetero youths, trans* and non-binary youth reported learning about a more diverse range of sexual health topics (such as abortion and sex work) from a more diverse range of sources including friends and the internet (Charest & Kleinplatz, 2021). Ironically, the heteronormativity perpetuated by public sex education (not to mention the medical field) may lead gender diverse youths to seek alternative – and more sex-positive – sources for their sexual information. It is also likely that in addition to capturing gender atypicality, our measures reflected young people’s rejection of traditional conceptualizations of binary gender norms altogether. Increasing numbers of young people identify outside the gender binary and preliminary work suggests these youths are particularly likely to feel left out of traditional sex education at school and to seek sexuality information elsewhere (Haley, Tordoff, Kantor, Crouch, & Ahrens, 2019). Thus, these findings may reflect the tremendous courage that gender diverse youths build as they navigate discrimination in their daily lives; having to educate others about one’s gender identity may build skills and resilience for navigating other tricky conversations. Similarly, rejecting traditional gender norms (and in some cases, the construct of binary gender) may also afford these youths more flexible and creative perspectives on sexuality (Schudson & Morgenroth, 2022) that contribute to willingness to discuss sexuality with others.

Sexual orientation

The barriers reported by sexually diverse respondents were more variable. Bisexual and mostly heterosexual participants were more likely to report embarrassment when asked to consider their experience with doctors. These findings align with work suggesting that less than half of queer youth felt comfortable disclosing their sexual identity to a doctor (Maguen, Floyd, Bakeman, & Armistead, 2002), and that bisexual youth were less likely to mention their sexual orientation to their physician when compared to other sexual minority groups (Meckler et al., 2006). However, bisexual participants were also significantly less likely than any other group to endorse “lack of trust” when talking to doctors. Possibly, our findings reflect a slowly increasing understanding of bisexual identities among young people. According to a recent nationally representative poll published, approximately 11.5% of Gen Z respondents (i.e., aged 18 – 25 years) identify as bisexual and 3.5% identify as gay or lesbian – higher than in any previous generation (Jones, 2021).

That said, when compared to heterosexual respondents, all sexual minorities were more likely to report shame in the parental context. Ironically, a supportive relationship with parents is one of the most important factors predicting resilience to internalized homophobia (Pachankis, Mahon, Jackson, Fetzner, & Branstrom, 2020) – and yet, as expressed by a number of our participants, the fear of losing that parental support is one of the biggest barriers to being able to discuss their sexual concerns.

Race and acculturation

Of our ten demographic factors, race was one of the few to not have any significant associations with communication barriers in either context. This is likely the result of low statistical power due to a largely racially homogenous sample, and not a true null. Indeed, a large literature suggests racial and ethnic groups differ in terms of comfort in sex communication, particularly in family contexts (Kim & Ward, 2007; Lee et al., 2012; Wilson et al., 2010). It is also possible that our simple measures of race alone missed important cultural and ethnic factors that contribute variance both between and within groups.

Participants reporting lower levels of heritage acculturation were more likely to endorse shame in the parental context, but not the physician context. It should be noted that, owing to the predominantly white sample, the heritage acculturation measure may reflect less about cultural assimilation and more about endorsement of one’s individual family values. Following this view, greater endorsement of one’s heritage culture correlates with increased family cohesion (Smokowski et al., 2008), which may protect adolescents from experiencing sexual shame when communicating with their parents. In contrast, low endorsement of heritage values has been associated with more sexual partners and more short-term sexual partnerships in adolescence (Meston & Ahrold, 2010), and other patterns of sexual behavior that youths may interpret as shameful in the eyes of their parents (Woo, Brotto, & Gorzalka, 2010).

In contrast, those reporting higher levels of mainstream acculturation were significantly less likely to report fear as a barrier to communication and significantly more likely to say there’s nothing hard about talking to doctors about sex. As most of our participants were white, our measure of mainstream acculturation may reflect participants’ assimilation into college culture and adopting the values of their fellow students. Greater comfort in the university setting – in particular, access to developmentally appropriate sexual health information through the student health center and peer educators – may empower students to talk about sexuality with their medical providers.

Religion and religiosity

Those who grew up as Evangelical Christians were more likely to report shame as a barrier to talking to their parents about sexuality. Interestingly, those who grew up either Catholic or Evangelical were significantly less likely to leave the medical provider question blank, suggesting they more readily endorsed a range of barriers to conversations with providers about sexuality. Possibly this reflects the broad literature suggesting that Evangelical Christian parents are more likely to either avoid conversations about sex with their children (Regnerus, 2005) or use predominantly shame-based messaging (Hottenstein, 2014), particularly with girls (Killam & Gingrich, 2011). That said, respondents’ self-reported current religiosity was not significantly correlated with barriers in either context, suggesting significant differences between participants’ religious upbringing and their personal thoughts and feelings about religion. Although prior work has shown that women’s current religiosity predicts their sexual shame (Cowden & Bradshaw, 2007), other work suggests that parental religiosity has a powerful effect on the likelihood of communicating sexual information (Ritchwood et al., 2017). In our own sample, participants expressed greater concerns about their parent’s religiosity than their own (e.g., “My parents are very religious and don’t share my views on sex”).

Implications of comparisons across contexts

The juxtaposition of themes suggests that young people recognize the value of talking about sexuality in a healthcare context – as one participant put it, “At first, it can be a little awkward….but after learning how important it is to talk about these issues, I’ve become more open and willing to share.” As such, young people may be ready to jump directly into interventions to build skills to communicate with providers. When it comes to similar interventions building communication skills with their parents, however, young people may benefit from a preliminary discussion of the benefits of open communication about sexuality with their families to get them on board. The transtheoretical model of behavior change suggests that skills-based interventions are most effective when applied to people who are ready to enact those skills, and likely to fail in people who do not see the value of making a change; applying this model to sex education programs has been shown to improve their efficacy (Davis, et al., 2014; Lee & Tsai, 2012; Horowitz, 2003). In our data, both the thematic content and the conceptual structure of the corpus suggest that young people may be at an action-oriented stage of change for communicating with their providers about sexuality, but pre-contemplative when considering talking with their parents.

Another key finding was although “embarrassment” and “awkwardness” were consistent themes across barriers to communicating with both parents and providers, those feelings manifested differently when considering demographic differences between members of the dyads (i.e., parent and child vs. patient and provider). For example, young people reported respect for doctors’ intelligence and experience. This respect led to a fear of being seen as incompetent or sexually inexperienced, as exemplified by the statements: “…I’m scared I’ll be judged because of my inexperience.”; “…I don’t want it to seem like I don’t know what I am doing…”. On the other hand, age differences between parent and child were more often related to generational differences with competing or incompatible values, often rooted in differences in religiosity. For example, participants responded: “They are old-fashioned, [they] do not believe in sex before marriage or any type of same-sex romantic or sexual relationships.”; “Different beliefs and values, mostly stemming from religion”.

Another example related to how gender differences manifested differently across contexts. Differences in gender between patient and provider were part of a generalized feeling of discomfort, as in one participants’ statement: “If they are not the same gender as me, then it feels awkward.” However, the same incongruity between parent and child was associated with more specific concerns about honoring a gendered childhood role (“daddy’s girl”; “momma’s boy”). To speak of sex would be to violate the inherent innocence of the bond in ways that were specifically keyed to gender role expectations, as in these statements: “…it makes it a little bit difficult for me to talk about sex with my dad because he looks at me as his “little girl” so I don’t want it to be awkward between us.”; “They don’t know that I have had sex and I feel like they see me as their angel child”.

Similarly, dyad-level differences in race, ethnicity, and resulting culture were also tied to embarrassment and awkwardness – but here too, these themes differed across contexts. Like with gender differences, race/ethnicity mismatch between patient and provider was seen in the framework of more generalized difficulties in communicating to unfamiliar people, as in this statement: “If they are male, I feel uncomfortable. If they are female, they usually aren’t the same race as me. There’s always something about the professional that makes me feel uncomfortable…” In the context of talking with parents, racial/ethnic differences were rarely cited (as most children were of similar racial/ethnicity identity as their parents) but acculturative differences were more commonly expressed. As with age and gender differences, acculturative differences with parents reflected more specific concerns about differing values, life experiences (e.g., “They did not have the same experience as I did. They did not start having sex until college…”) and levels of comfort in communicating about sex (e.g., “traditional values and their own aversions to taboo subjects”).

Actionable Recommendations

Taken together, our findings point to some actionable recommendations for researchers, parents, providers and institutions. Regarding recommendations for sexual education research, our findings underscore the value of mixed methods for identifying contextual factors that could make or break an educational intervention. While the same barrier was mentioned across contexts (e.g., “awkwardness”) – and presumably would be endorsed at similar rates in traditional surveys – the mechanism of those barriers differed by context. This subtle difference suggests different interventions may be needed for the “same” barrier. For example, in talking to parents, “awkwardness” may stem from fears of fundamentally altering parental perception of their child’s dependence/interdependence. In this case, reducing awkwardness requires setting expectations that talking about sex will not change parent’s (positive) perception of their child, and may deepen rather than jeopardize the intimacy of the parental relationship. For talking to providers, “awkwardness” reflects perceptions that one must be seen as adult to receive care for one’s sexual wellbeing, and insecurity occupying an adult role. In this case, reducing awkwardness requires providers recognize young people’s sexual activity in the context of their normative development, and normalizing both their experience and their concerns.

In terms of recommendations for parents, our respondents made it clear that discomfort confers discomfort; the verbal and non-verbal difficulty that parents experience when talking to their kids about sex confers a shame that is not easily overcome. Further, this shame leads children to find other sources of information about sexuality, which may or may not be accurate. Thus, parents should work actively to identify and confront the sources of their own discomfort around sexuality. And, while parents may fear that their children don’t want to engage with them about topics such as sexual pleasure or sexual identity, our findings and those of others (e.g., Pariera & Brody, 2018) suggest quite the opposite; these conversations, though rarely reported, were deeply valued by the young people in our sample.

For providers, taking time to build rapport before broaching the subject of sex is paramount. Many of our respondents stated that their provider felt like a stranger, and this lack of familiarity made it difficult to introduce intimate topics. Further, demeanor matters; our participants felt that many providers were cold, too professional, and unfamiliar. Lastly, many participants were afraid of their providers breaking their trust by discussing what they had disclosed about their sexuality with their parents, representing a significant proportion of the “fear” category of responses. Providers may help reduce this fear by proactively describing the (few) circumstances under which they would be medically or legally required to disclose information about their patient’s sexuality to their parents, prior to starting the conversation. Also, following private consultations, providers should ask patients about the topics they feel comfortable discussing openly when their parents are back in the room, as our participants noted that comfort disclosing some things to their parents (e.g., contraceptive use) did not indicate willingness to disclose all sexual matters (e.g., their sexual orientation).

Another important note our participants made was regarding differences in gender identity and race/ethnicity between themselves and their providers. From our data, young patients were clearly more comfortable sharing important health-related information with providers with whom they identify. From an institutional perspective, these findings underscore the importance of recruiting and retaining gender and race-diverse healthcare providers. Moreover, these findings support the recent movements to integrate cultural humility into medical education and public health infrastructures (Allwright, Goldie, Almost, & Wilson, 2019; Solchanyk, Ekeh, Saffran, Burnett-Zeidler, & Doobay-Persaud, 2021). These recommendations may help to foster a variety of more sex-positive, comfortable environment for adolescents to learn about their sexuality, leading to healthier outcomes overall.

Limitations and future directions

Overall, we found that young adults reported different barriers to communicating about sexuality with their parents as opposed to healthcare providers. While these results are novel, they should be considered in the context of their limitations. Our sample was composed mostly of psychology majors or related fields, and largely from the United States. In addition, this sample was largely racially homogenous, as reflective of the geographic areas where the surveys were conducted. Future studies should conduct similar analyses in a non-convenience sample.

Because most of our sample reported high levels of cis-typicality, we were unable to glean insights on the barriers to discussing sexuality and sexual health with parents and doctors for transgender, gender non-conforming, nonbinary, and gender expansive folks. Especially given present legislation in the United States (bans on gender-affirming healthcare, anti-trans bills in schools), it is reasonable to expect that gender-expansive folks would report different and more salient barriers to discussing their sexual wellbeing with both parents and doctors. Indeed, ample research suggests that LGBTQ+ individuals broadly are less likely to trust their doctors (Quinn et al., 2019). This distrust is particularly salient for transgender patients (Kosenko et al., 2013).

Additionally, most of our sample was white. Women of color tend to be fetishized, sexualized, and objectified at earlier ages than their white peers (Holmes, 2016). Parents may respond to their daughters’ sexualization with greater restrictions regarding discussing and exploring sexuality (Brown-Guillory, 2021). It is reasonable to expect that findings would differ from a sample of racially diverse respondents. Moreover, due to racial discrimination in medical training and access to medical education across the US (Steinecke & Terrell, 2010), it is likely that respondents of color would be interfacing with majority white doctors and medical providers (Association of American Medical Colleges, 2019). Given sociocultural structures of white supremacy and fetishization of women of color, as well as distrust in the medical establishment grounded in medical discrimination against patients who are Black, Indigenous and/ or people of color (BIPOC; Casanova-Perez et al., 2021), these participants may identify race-based barriers to discuss their sexual lives with white doctors. This future direction for research is undergirded by research asserting that racial concordance between provider and patient is associated with greater patient satisfaction and quality of care (Saha et al., 1999).

Further, while this qualitative analysis has its strengths, we are limited in the amount of information and context provided within short-answer responses; despite their drawbacks, it may be valuable to conduct lengthier interviews for richer data. We did not assess for the time since the last healthcare visit or since the last conversation about sexuality with one’s parents, and thus cannot control for possible recall biases. This limitation is somewhat softened by the fact that we were assessing participants’ general perceptions and attitudes towards communication, which may be less subject to recall bias than ability to remember specific details of those conversations (Zygar-Hoffman & Schonbrodt, 2020). Nevertheless, it is possible that some participants were responding with specific incidents in mind, and to that end, recall and recency biases would play a more prominent role. Also, although we surveyed barriers in dyadic relationships, we only collected data from one member; future analyses should analyze patient-provider and child-parent dyads for a more holistic view. These analyses may have also been subject to coder bias; however, we believe this was partially mitigated by the diversity within our team.

Because participants were not required to write anything at all in response to the open-ended questions, there were many non-responses. In some ways, the free nature of responses (and subsequently higher missing data) can be interpreted as a strength as the resulting data point to those concerns which were sufficiently forefront in our participants’ minds to be offered spontaneously and voluntarily. That said, the presence of many non-responses in may have shaped the construction of clusters in our aggregative clustering analyses. Future analyses that choose to drop non-responses may find different structures of answers to similar questions. Finally, in our exploratory analyses, we treated data from our Likert scales as approximating that of a continuous interval scale by using linear models. While there is reason to expect that our results approximated the true effect sizes in our sample (Wu & Leung, 2017), future confirmatory work may seek to assess the robustness of these effects across modeling strategies. Despite these limitations, our findings reflect the voices of young people in their own understanding of the difficulties – and benefits – of talking to parents and providers about their sexuality.

Public Policy Statement:

Young people often face barriers to discussing their sexual health with either parents or healthcare providers. The present findings highlight similarities in barriers across context (such as embarrassment) but also some unique barriers by context (such as fear of seeming sexually inexperienced in front of providers, but not with parents). These findings suggest that young people are attentive to the ways in which having a conversation about sex may differentially impact relationship and identity dynamics in each context, and point to the need to attend to these concerns when tailoring interventions to support young adult’s sexual health communication.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health [P20GM130461] and the Rural Drug Addiction Research Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the University of Nebraska.

The authors would like to acknowledge research assistants who participated in coding but are not authors: Libby Shonka-Smith, Kirstin Clephane, and Anneliis Sartin-Tarm. We would also like to thank our participants for their candor. We hope that we did your stories justice.

Footnotes

Participants were asked to identify their biological sex and separately their gender identity (see below). However, research and theory suggest that that brief demographic questions are ill suited to capturing true distinctions between these constructs. The construct of “biological sex” as a group membership separate from gender is itself predicated on assumptions that physiology is not shaped by behavior or social systems (Fausto-Sterling, 2012), which is not well supported by research (van Anders, 2022; Hyde, Bigler, Joel, Tate, & van Anders, 2019). As such, we here refer to the results of the survey questions capturing participants’ reported “biological sex” as their “sex/gender”.

References

- Ahrold T, Meston C (2010). Ethnic Differences in Sexual Attitudes of U.S. College Students: Gender, Acculturation, and Religiosity Factors. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 190–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahrold T, Farmer M, Trapnell PD & Meston C (2011). The Relationship Among Sexual Attitudes, Sexual Fantasy, and Religiosity. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 619–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander S, Fortenberry JD, Pollak KI, Bravender T, Davis JK, Østbye T, Tulsky JA, Dolor RJ, & Shields CG (2014). Sexuality talk during adolescent health maintenance visits. JAMA Pediatrics, 168(2), 163–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allwright K, Goldie C, Almost J, Wilson R. (2019). Fostering positive spaces in public health using a cultural humility approach. Public Health Nursing, 36, 551–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association of American Medical Colleges. (2019). Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Report retrieved from: https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/figure-18-percentage-all-active-physicians-race/ethnicity-2018

- Brown-Guillory E. (2021). Disrupted Motherlines: Mothers and Daughters in a Genderized, Sexualized, and Racialized World. In: Women of Color (pp. 188–207). University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R, & Salem DA (1999). Concept mapping as a feminist research method. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 23(1), 65–89. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova-Perez R, Apodaca C, Bascom E, Mohanraj D, Lane C, Vidyarthi D, … & Hartzler AL (2021). Broken down by bias: Healthcare biases experienced by BIPOC and LGBTQ+ patients. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings, 2021, 275–284 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charest M, & Kleinplatz PJ (2021). What do young, Canadian, straight and LGBTQ men and women learn about sex and from whom? Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 19(2), 622–637. [Google Scholar]

- Coakley TM, Randolph S, Shears J, Beamon ER, Collins P, & Sides T (2017). Parent–youth communication to reduce at-risk sexual behavior: A systematic literature review. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 27(6), 609–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN). (2022). Extract and visualize the results of multivariate data analyses [R package factoextra version 1.0.7]. The Comprehensive R Archive Network. Retrieved January 8, 2022, from https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/factoextra/index.html [Google Scholar]

- Cowden CR, & Bradshaw SD (2007). Religiosity and sexual concerns. International Journal of Sexual Health, 19(1), 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Davis R, Campbell R, Hildon Z, Hobbs L, & Michie S (2014). Theories of behaviour and behaviour change across the social and Behavioural Sciences: A scoping review. Health Psychology Review, 9(3), 323–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fausto-Sterling A (2012). Sex/gender: Biology in a social world. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fiscella K, Goodwin MA, & Stange KC (2002). Does patient educational level affect office visits to family physicians? Journal of the National Medical Association, 94(3), 157–165. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CM, Telljohann SK, Price JH, Dake JA, & Glassman T (2015). Perceptions of elementary school children’s parents regarding sexuality education. American Journal of Sexuality Education, 10(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Foshay JE, & O’Sullivan LF (2020). Home-based sex communication, school coverage of sex, and problems in sexual functioning among adolescents. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 29(1), 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Fuzzell L, Shields CG, Alexander SC, & Fortenberry JD (2017). Physicians talking about sex, sexuality, and protection with adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(1), 6–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gausman J, Othman A, Daas I, Hamad I, Dabobe M, & Langer A (2020). How Jordanian and Syrian youth conceptualise their sexual and reproductive health needs: A visual exploration using concept mapping. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 23(2), 176–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haderxhanaj LT, Leichliter JS, Aral SO, & Chesson HW (2014). Sex in a lifetime. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 41(6), 345–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley SG, Tordoff DM, Kantor AZ, Crouch JM, & Ahrens KR (2019). Sex education for transgender and non-binary youth: Previous experiences and recommended content. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 16(11), 1834–1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry-Reid LM, O’Connor KG, Klein JD, Cooper E, Flynn P, & Futterman DC (2010). Current pediatrician practices in identifying high-risk behaviors of adolescents. Pediatrics, 125(4), e741–e747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes CM (2016). The colonial roots of the racial fetishization of Black women. Black & Gold, 2(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz SM (2003). Applying the transtheoretical model to pregnancy and STD Prevention: A review of the literature. American Journal of Health Promotion, 17(5), 304–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hottenstein JL (2014). Femininity, Masculinity, Gender, and the Role of Shame on Christian Men and Women in the Evangelical Church Culture. [Doctoral Dissertation, George Fox University]. Digital Commons George Fox University, Publication No. 158. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde JS, Bigler RS, Joel D, Tate CC, & van Anders SM (2019). The future of sex and gender in psychology: Five challenges to the gender binary. American Psychologist, 74(2), 171–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, & Trochim WM (2002). Concept mapping as an alternative approach for the analysis of open-ended survey responses. Organizational Research Methods, 5(4), 307–336. [Google Scholar]

- Jones JM (2021). LGBT identification rises to 5.6% in latest US estimate. Gallup News, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Kazmerski TM, Prushinskaya OV, Hill K, Nelson E, Leonard J, Mogren K, Pitts SAB, Roboff J, Uluer A, Emans SJ, Miller E, & Sawicki GS (2019). Sexual and reproductive health of young women with cystic fibrosis: A concept mapping study. Academic Pediatrics, 19(3), 307–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelle U, & Laurie H (1995). Computer use in qualitative research and issues of validity. In Kelle U (Ed.), Computer-aided qualitative data analysis: Theory, methods, and practice (pp. 19–28). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Killam RK, & Gingrich HD (2011). Sexuality among Evangelical college women. Growth: The Journal of the Association for Christians in Student Development, 10(5), 40–53. [Google Scholar]

- Kim JL, & Ward LM (2007). Silence speaks volumes: Parental Sexual Communication among Asian American emerging adults. Journal of Adolescent Research, 22(1), 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kosenko K, Rintamaki L, Raney S, & Maness K (2013). Transgender patient perceptions of stigma in health care contexts. Medical Care, 51(9): 819–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff K (1980). Validity in content analysis. In Mochmann E (Ed.), Computerstrategien die kommunikationsanalyse (pp. 69–112). Frankfurt, Germany: Campus Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee JT, & Tsai JL (2012). Transtheoretical model-based postpartum sexual health education program improves women’s sexual behaviors and sexual health. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 9(4), 986–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz T (2019). Sexual Wellbeing in Heterosexual, Mostly Heterosexual, and Bisexually Attracted Men and Women. International Journal of Sexual Health, 31(3), 339–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz T (2020a). Antidepressant use during development may impair women’s sexual desire in adulthood. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 17(3), 470–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz T (2020b). Sexual wellbeing in heterosexual, mostly heterosexual, and bisexually attracted men and women. International Journal of Sexual Health, 31(3), 339–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz T (2020c). Predictors and impact of psychotherapy side effects in young adults. Counselling & Psychotherapy Research, 21(1), 237–243. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz T (2021). Relying on an “Other” Category Leads to Significant Misclassification of Sexual Minority Participants. LGBTHealth, 8(5), 372–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lung SL, Wincentak J, Gan C, Kingsnorth S, Provvidenza C, & McPherson AC (2021). Are healthcare providers and young people talking about sexuality? A scoping review to characterize conversations and identify barriers. Child: Care, Health and Development, 47(6), 744–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguen S, Floyd FJ, Bakeman R, & Armistead L (2002). Developmental milestones and disclosure of sexual orientation among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 23(2), 219–233. [Google Scholar]

- Malacane M, & Beckmeyer JJ (2016). A review of parent-based barriers to parent–adolescent communication about sex and sexuality: Implications for sex and family educators. American Journal of Sexuality Education, 11(1), 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Meckler GD, Elliott MN, Kanouse DE, Beals KP, & Schuster MA (2006). Nondisclosure of sexual orientation to a physician among a sample of gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 160(12), 1248–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]