Abstract

Background:

Causal feature selection is essential for estimating effects from observational data. Identifying confounders is a crucial step in this process. Traditionally, researchers employ content-matter expertise and literature review to identify confounders. Uncontrolled confounding from unidentified confounders threatens validity, conditioning on intermediate variables (mediators) weakens estimates, and conditioning on common effects (colliders) induces bias. Additionally, without special treatment, erroneous conditioning on variables combining roles introduces bias. However, the vast literature is growing exponentially, making it infeasible to assimilate this knowledge. To address these challenges, we introduce a novel knowledge graph (KG) application enabling causal feature selection by combining computable literature-derived knowledge with biomedical ontologies. We present a use case of our approach specifying a causal model for estimating the total causal effect of depression on the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) from observational data.

Methods:

We extracted computable knowledge from a literature corpus using three machine reading systems and inferred missing knowledge using logical closure operations. Using a KG framework, we mapped the output to target terminologies and combined it with ontology-grounded resources. We translated epidemiological definitions of confounder, collider, and mediator into queries for searching the KG and summarized the roles played by the identified variables. We compared the results with output from a complementary method and published observational studies and examined a selection of confounding and combined role variables in-depth.

Results:

Our search identified 128 confounders, including 58 phenotypes, 47 drugs, 35 genes, 23 collider, and 16 mediator phenotypes. However, only 31 of the 58 confounder phenotypes were found to behave exclusively as confounders, while the remaining 27 phenotypes played other roles. Obstructive sleep apnea emerged as a potential novel confounder for depression and AD. Anemia exemplified a variable playing combined roles.

Conclusion:

Our findings suggest combining machine reading and KG could augment human expertise for causal feature selection. However, the complexity of causal feature selection for depression with AD highlights the need for standardized field-specific databases of causal variables. Further work is needed to optimize KG search and transform the output for human consumption.

Keywords: knowledge representation, management, or engineering, knowledge graphs, causal modeling, feature selection, Alzheimer’s disease, depression

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) are widely considered to be the paramount method for determining the causal relationship between exposure and outcome in the medical field1. The supremacy of RCTs is due to the efficacy of randomization in eliminating bias by eliminating the relationship between exposure assignment and the health characteristics of study participants that may impact the outcome. However, there are instances where RCTs are not feasible due to ethical or pragmatic reasons. For instance, studying the risk factors for chronic diseases among older adults through RCTs can be impractical, as RCTs typically require short durations and healthy participants. Additionally, the external validity of RCTs can be problematic, as it may not be possible to generalize conclusions from the study to the target population1. Therefore, study designs have been developed to address these limitations to estimate the effects of non-randomized, observational data.

However, confounding bias is common when estimating causal effects in observational studies. Confounding bias occurs when a third unrelated factor is linked to both the exposure and the outcome of interest, distorting the true causal effect of the exposure. Researchers can use methods like matching, stratification, restriction, or statistical adjustment to reduce or eliminate this bias. Thus, identifying variables sufficient to control for confounding bias is essential to estimate the effects from observational data reliably2. This variable identification task, causal feature selection, is the present study’s focus.

Fortunately, the causal inference literature has produced exacting causal criteria to guide causal feature selection, i.e., to populate a causal model (often in a directed acyclic graph or DAG) 2–4. These causal criteria recommend which variables to include in an adjustment set. First and foremost of these criteria is the Principle of the Common Cause or PCC, first expressed by philosopher of science Hans Reichenbach4. Essentially, the PCC requires the inclusion of all common causes (confounders) of the exposure and the outcome. More recently, more advanced alternative criteria have been proposed for mitigating scenarios with unmeasured confounders5. Nevertheless, applying these causal feature selection criteria to real-world problems depends on accurate, granular knowledge about etiological relationships relating an exposure to an outcome.

Traditionally, the task of causal feature selection depends on prior knowledge of the subject matter through literature review, or expert consultation has fallen to human content-matter experts to identify and carefully select variables for which to control2,6,7 using a judicious mix of content-matter expertise, literature review, and guesswork8–11. However, the literature is vast (PubMed indexes over 1 million articles per year12), making this a difficult task for humans to carry out. Knowledge about the underlying causal structure is fragmentary and in constant revision.

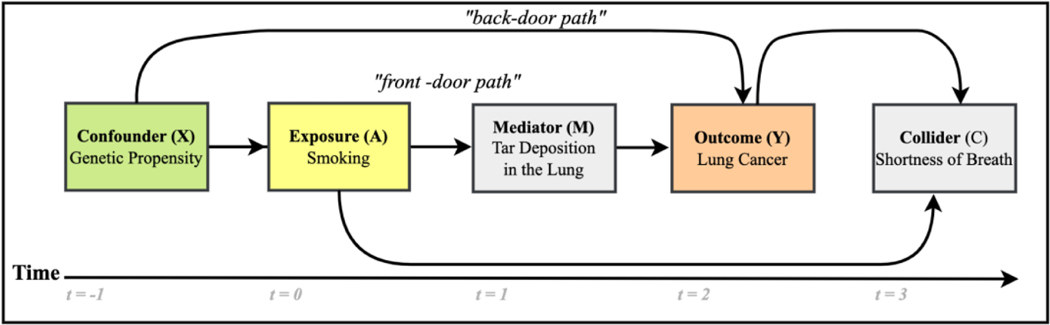

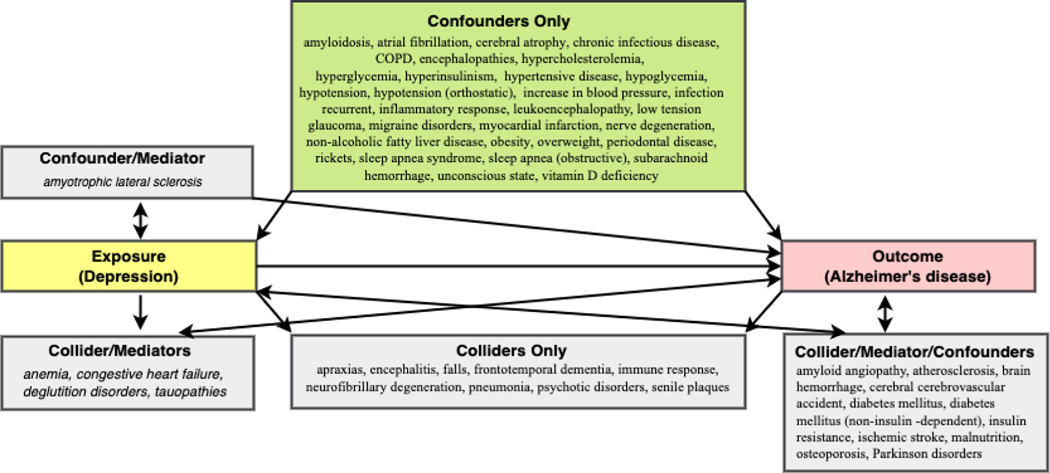

The roles (confounder, collider, and mediator) played by variables etiologically related to an exposure and an outcome are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

This causal diagram depicts exposure (A) and outcome (Y) in yellow and orange, respectively, along with a confounder denoted “X” with a green background, a mediator variable denoted “M” with a gray background, and a collider “C” also with a gray background. The green background for the confounder means that it is desirable to condition on such variables. Gray indicates that conditioning on that type of variable induces bias.

Causal variables do not always behave solely as confounders. For example, conventional regression-based estimates fail under treatment confounder feedback13, in which confounders act simultaneously as intermediate variables called mediators14–16. Conditioning on mediators is not recommended for estimating the total causal effect as mediators are on the causal path and tend to bias effect measures. Variables that act simultaneously as confounders and mediators are also called confounders affected by prior treatment, or CAPTs17. CAPTs should not be adjusted for unless estimation methods designed for this purpose are used.

Additionally, variables called colliders, the common effects of the exposure and outcome, should not be used for conditioning because they induce collider bias that distorts measures of effect. By introducing non-causal dependency, collider bias can inflate a null effect into a positive or negative effect or reverse the direction of the effect18. In a well-known example of collider bias, a strong association was detected between locomotor disease (exposure) and respiratory disease (outcome): odds ratio (OR) 4.09. In this case, collider-stratification bias resulted from looking only at hospitalized patients. When the data included a mix of hospitalized patients and the general population, this association was absent (OR 1.06)19. Thus, because variables may not act in well-defined categories, it is important to be aware of potentially ill-behaved covariates when selecting features so that variables with complex behavior can be dealt with optimally. In our Discussion, we address these and related issues in more depth.

The inability to ensure comprehensive knowledge can mean that important confounders are not controlled for20,21 while inappropriate variables are19,22–24. Fortunately, it may be possible to reduce confounding bias better and prevent inducing bias from the inappropriate selection of variables by considering a more comprehensive set of potential confounders using computational tools.

Harnessing computable causal knowledge made accessible by machine reading could improve the comprehensiveness of causal feature selection. Machine reading works by capturing concepts25, or units of meaning representing specific biomedical entities or ideas in a text, e.g., diseases, symptoms, treatments, but also how different concepts are related by automatically extracting knowledge from the biomedical literature in subject-predicate-object triples, also called semantic predications, e.g., “ibuprofen TREATS migraine.” These concepts are then represented in standardized terminologies and ontologies that describe and communicate healthcare-related information. There is substantial literature on workflows deploying triples from machine reading systems in a broad range of biomedical applications from pharmacovigilance26–29, cancer research30,31, and drug repositioning32,33. However, machine reading output has potential weaknesses. For instance, the recall of machine reading is low relative to other natural language processing tasks since machine reading systems often rely on overly precise manually-crafted patterns34. Furthermore, machine reading output may be incomplete. For instance, while a machine reading system may accurately detect the above predication, critical implied information may be missed. For example, as human semantic reasoners proficient in English, it may be possible to infer that therapeutic potential extends to all NSAIDs, the broader category of drugs to which ibuprofen belongs, or that ibuprofen and the other NSAIDs could also treat migraine. Other weaknesses include that machine reading systems can produce erroneous output that is unsuitable as is for downstream applications, e.g., causal feature selection35. We address these challenges further in the Discussion.

Fortunately, biomedical ontologies contain authoritative, expert-curated representations of entities and relationships between those entities that are exploitable by computer programs. Causal knowledge in these ontologies has been used to inform causal models in AD research36 and elsewhere37–41. This knowledge could be used to filter out erroneous assertions from machine reading by distilling those assertions through the ontologies created by domain experts. However, like the literature, biomedical ontologies are incomplete due to the extensive manual effort to build and maintain them42.

The computable literature-derived knowledge from the literature and ontology-grounded resources are often consolidated into a knowledge graph (KG) representation. A KG is defined as a “graph-theoretic representation of human knowledge such that it can be ingested with semantics by a machine43.”In biomedical KGs, entities such as disease phenotypes, genes, enzymes, ligands, and diseases are represented as nodes, while edges (or arrows) denote relationships (predicates) between the nodes. Certain KG implementations can employ ontology-grounded information to prune erroneous inputs and thus may partially overcome the limitations of relying exclusively on structured information extracted from the literature.

This paper introduces a novel causal feature selection method using a KG application combining literature-derived structured knowledge with the precise semantics of ontology-grounded resources. Our approach entails constructing and searching a large biomedical KG and provides a proof of concept in a use case identifying and refining a set of confounders for estimating the total causal effects of depression on Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

AD is the fourth most common cause of death for those 75 years of age or older44 and is a progressive, multifactorial neurodegenerative disease and the most common cause of dementia. Although most commonly associated with progressive memory loss, AD impacts cognitive ability across multiple domains45, including executive and language function, sleep, mood, and personality. Over time, it reduces a person’s autonomy and leads to death. Despite AD’s significant and growing burden, major knowledge gaps remain in AD diagnosis, treatment, and prevention, and only two FDA-approved disease-modifying therapies exist (Iacanumab and Aducanumab). Depression is a common mental illness where the person focuses on negative emotions with symptoms of restlessness, inability to focus, irritability, fatigue, and suicidal thoughts, and may be accompanied by coping behavior, e.g., overeating46,47.

We chose to study the relationship between depression and AD as a use case for the following reasons. First, the two conditions are multifactorial and heterogeneous in nature48,48–50 and have overlapping clinical definitions, common risk factors, and etiological mechanisms48–52. Hence, we expect the structure of the causal neighborhood of variables related to both depression and AD to be inherently challenging and complex. We would expect to find variables that play multiple roles. Second, recent insights into the modifiable risk factors present unprecedented opportunities for preventive interventions to reduce AD’s disease burden dramatically. The Lancet Commission on dementia identified depression among eleven other modifiable risk factors, reporting that 40% of AD diagnoses are attributable to these modifiable risk factors53. Thus, if depression were truly an independent risk factor, reducing the prevalence of depression could also reduce the population-level disease burden of AD.

However, controversy surrounds depression as either an independent and modifiable risk factor or a prodrome of AD in late life, making depression an interesting condition to study. Lastly, depression is a highly prevalent disorder. In 2018, it was the third most common mental illness; by 2030, it is expected to become the number one most prevalent mental illness47. The prevalence of depression has also been exacerbated by current events, including the COVID-19 pandemic54. Thus, if the relationship between depression and AD is genuinely causal, intervening in depression could significantly impact public health. Taken together, the depression and AD relationship is a good fit as a use case since the objective of our causal feature selection method could address a critical need to clarify the etiological status of depression for its effect on AD risk in future studies by furnishing a more comprehensive set of confounders.

This work aims to advance the state-of-the-art causal feature selection method that combines literature-derived structured knowledge with the precise semantics of ontology-grounded resources. The essential idea of this study is to use information extracted from the literature to define the domain of discourse (here, the set of variables potentially related to depression and AD) and then filter out the variables based on biological plausibility using an ontology-grounded KG. We hypothesize that:

It is possible to identify plausible confounders, colliders, and mediators from structured knowledge distilled from the literature through an ontology-grounded KG (H1). Some of the variables identified by the KG search would also appear in the results of complementary methods and be reported in published observational studies.

There is a high degree of complexity regarding the variables linking depression and AD because of the bidirectional nature of the relationship between depression and AD (H2). Hence, we expect many variables, including confounders, to play multiple causal roles.

● The reasoning paths traversed searching the KG can produce reasonable hypotheses for the mechanisms underlying the relationships between the variables and clarify their meaning (H3).

In the next section, we describe the workflow for extracting and post-processing the structured knowledge from the literature, constructing the KG, and reporting and evaluating the KG search results. Then, we report the KG search results and evaluation. Finally, we interpret these results in the context of our use case and clarify the strengths and weaknesses of the approach to inform future work.

2. Methods and Materials

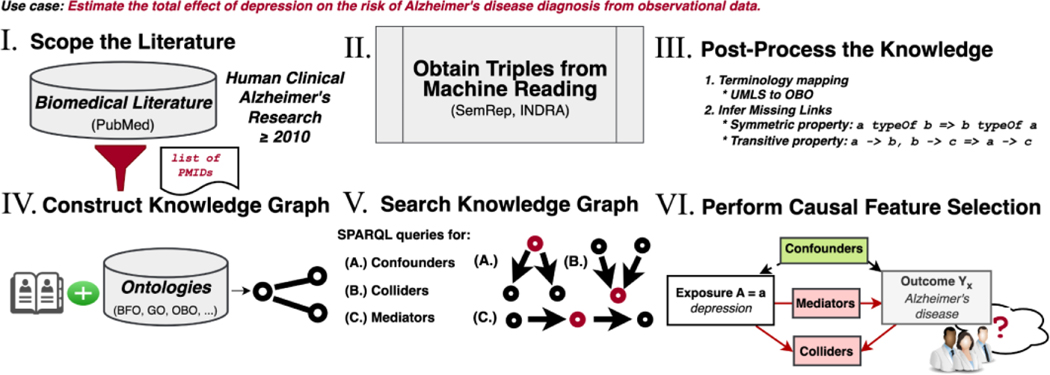

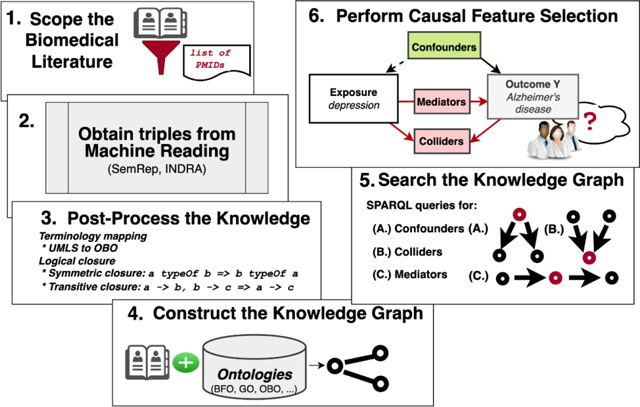

Figure 2 shows the workflow for this study. We first delineated the scope of the corpus of articles in PubMed by their PubMed identifiers. Next, we extracted triples from the titles and abstracts from the articles in the corpus using machine reading systems (SemRep55–57 along with EIDOS and REACH in the INDRA58 ecosystem) and combined and harmonized the outputs. We refer to the graph containing the outputs, i.e., the structured knowledge derived from machine reading of the literature (and in the post-processing stages), as the extraction graph. Next, since there may be information logically entailed by the extracted information, we applied forward-chaining over the extracted triples to infer implied triples based on logical properties, e.g., transitivity, symmetry, asymmetry, and reflexivity, of predicates extracted by machine reading. The terminology-mapped and logically closed extraction graph was combined with an ontology-grounded KG constructed with the PheKnowLator workflow developed by Callahan et al.59–61. We then translated standard epidemiological criteria for confounders, colliders, and mediators into discovery patterns, which are semantic constraints over the relations between concepts62. We implemented those discovery patterns as SPARQL queries for searching the KG based on our previous research63. We analyzed the KG search results for evaluation by compiling the variables by their simple and combined roles and comparing these results with reported confounders from published observational studies that we manually collected from a pilot meta-review and the output of a complementary method (searching the Semantic MEDLINE database, or SemMedDB64). Finally, we manually inspected a selection of variables by inspecting the source sentences, interpreting explanatory reasoning paths produced by the search, and searching PubMed.

Figure 2.

The principal stages of the workflow to construct the causal feature selection system. I. Scope the literature to clinical studies investigating AD, published in 2010 or after. II. Obtain triples from the machine reading systems. III. Post-process the knowledge by performing logical closure operations with the CLIPS production rule system65,66 to infer missing edges and terminology mapping. IV. Construct the KG using the PheKnowLator platform, merging the output of the machine reading systems with ontology-grounded information. V. Search the KG to identify relevant variables. VI. Compile the search results into a causal model analyzing KG search result output and comparing that output with the structured knowledge in SemMedDB, the results of a pilot meta-review of reported confounders collected from observational studies, and PubMed.

We provide details for each component in the paragraphs below and document constructing the extraction graph and KG search. The code we produced for this work is available on the Zenodo project repository, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6785307. Documentation for how to use this code archive is available in Appendix C in the Supplementary Materials.

2.1. Scoping the literature

We consulted with a health sciences librarian to design a PubMed query (see File II. (Appendix_C.docx), Listing S1) to limit the indexed literature’s scope to human research related to AD-related associations and risk factors. The idea is to ingest a significant fraction of the concepts in the AD domain while having a tractable data set. We limited the search to 10 years before the search date (July 11, 2020) to a subset of the literature related solely to AD. This is because different types of dementia may have different underlying etiological mechanisms and risk factors.

2.3. Obtaining triples from machine reading

SemRep.

SemRep is a natural language processing tool developed by the National Library of Medicine (NLM) for extracting semantic triples from biomedical literature55. SemRep uses a named entity recognition system called MetaMap67–69. MetaMap transforms mentions of particular biomedical entities identified as components of semantic triples to “concepts” in the Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) metathesaurus55. Each concept in the UMLS metathesaurus is assigned a unique handle called a concept unique identifier or CUI. SemRep infers relations between entities encountered in the biomedical text using a part-of-speech tagger and a semantic network informed by semantic constraints and outputs semantic triples. SemRep has been evaluated extensively over its existence (now almost two decades). Evaluations focusing on SemRep’s intrinsic ability to extract semantic triples that accord with human judgment have yielded 0.55–0.9 precision, 0.24–0.42 recall, and 0.38–0.5 F155. For more extensive information on SemRep, see an overview of Semrep by Kilicoglu55.

We used the triples present in the Semantic MEDLINE database, SemMedDB. We downloaded SemMedDB version 40 (on June 1st, 2020). We searched SemMedDB for the triples associated with the PubMed identifiers resulting from the literature scoping query.

INDRA.

The Integrated Network and Dynamical Reasoning Assembler, or INDRA, is an automated machine reading and model assembly software. We use two machine reading systems developed within the ecosystem, EIDOS and REACH. EIDOS is a rule-based open-domain machine reader that extracts causal and correlational relations between events mentioned in free-text70,71. EIDOS extracts three predicate types - EVENT, INFLUENCE, and ASSOCIATION. EVENT signifies a change or modification of a concept identified by the machine reader. INFLUENCE is a causal relationship between two events, while ASSOCIATION represents a set of events without implying causality. REading and Assembling Contextual and Holistic mechanisms from text, or REACH, detects mentions of protein-modifying biochemical processes called post-translational modifications in text. Mass fluorescence spectroscopy has allowed for the precise characterization of different post-translational modifications and opened the possibility of discovering novel biomarkers, therapeutic strategies, or drug targets involving protein interactions. In addition, a burgeoning literature in AD research79–81 has revealed that many processes involving proteins related to AD’s pathogenesis are related to perturbations to processes involving post-translational modifications. REACH provides a window into these processes. Table 1 lists the predicates detected by the machine reading systems we analyze in the paper.

Table 1.

This table displays the subset of predicates we analyze in this paper, organized by machine reading system and semantic domain. These machine reading system predicates were chosen because they describe information essential for causal feature selection and modeling.

| READER | Semantic Domains | Predicates |

|---|---|---|

| SemRep | Clinical Medicine | TREATS, PREVENTS |

| Molecular Interactions | INTERACTS_WITH, INHIBITS, STIMULATES | |

| Disease Etiology | ASSOCIATED_WITH, CAUSES, PRECEDES, PREDISPOSES | |

| Pharmacogenomics | AFFECTS, AUGMENTS, COMPLICATES, DISRUPTS, INHIBITS, STIMULATES | |

| Static Relations | PART_OF, COEXISTS_WITH | |

| INDRA/EIDOS | General Domain | ASSOCIATION, INFLUENCE |

| INDRA/REACH | Biochemical Reactions (involving covalent modification of a protein by attaching a functional group) | PHOSPHORYLATION, UBIQUITINATION, HYDROXYLATION, SUMOYLATION, GLYCOSYLATION, ACETYLATION, FARNESYLATION, RIBOSYLATION, METHYLATION |

| Nested Events / “Regulations” | REGULATES, PROMOTES, INHIBITS, ACTIVATES |

2.3. Knowledge post-processing

2.3.1. Terminology mapping

The purpose of knowledge post-processing is to improve the accuracy and completeness of the literature-derived knowledge. In this step, we use knowledge hygiene via terminology mapping and automated reasoning to transform the output from machine reading into an extraction graph with inferred information from applying logic and with concepts mappable to an ontology-grounded KG. Knowledge hygiene is required to make the machine reading output more amenable to inference. Knowledge hygiene addresses issues with the completeness and validity of the extracted data, including redundancy.

We performed the following steps on the triples extracted by the machine reading systems. First, triples were removed with phrases in the subject or object position with more than three space-delimited tokens, e.g., “alpha-blockers aggravation cognitive dementia patients,” from the corpus since these phrases could not be condensed to a single concept. Second, we filtered out irrelevant predicates, e.g., LOCATION_OF, and retained only the predicates listed in Table 1. We also removed duplicate triples. Third, we assigned a default probabilistic belief score of 0.8 to all SemRep triples. The belief score is a value that represents the level of confidence we place in the accuracy of the triple and ranges on a scale from 0 (no confidence) to 1.0 (certainty). The value of 0.8 was chosen because it is the average published performance characteristic across SemRep’s various predicates64,75.

Fourth, we mapped the REACH predicates to RO:0002436 MOLECULARLY_INTERACTS_WITH, except for phosphorylation, which was mapped to RO:0002447 PHOSPHORYLATES in the Relation Ontology (RO)76. We used the built-in INDRA preassembly module to remove duplicate triples and assign belief scores for the extracted triples from REACH and EIDOS with the INDRA belief module. From EIDOS, we included all unique INFLUENCE and ASSOCIATION triples. We also mapped the biomedical entities appearing in the subject and object positions in the extracted INDRA triples to UMLS concepts using MetaMap67,68 (version 1.8 with UMLS version 2018AA) and obtained the CUI, UMLS preferred name, and semantic type for the top-scoring match from MetaMap for each concept. All triples were removed from the corpus used to create the extraction graph where the subject, predicate, or object did not have a corresponding mapping in UMLS. Lastly, the triples from all three readers were converted to tab-separated files in a combined corpus that included one row for each subject, predicate, object (with UMLS mapping information), belief score, source sentence, and PubMed ID of the original text and combined the machine readers’ output into an extraction graph. The extraction graph contains only the literature-derived triples from each of the readers.

2.3.2. Logical closure over the extraction graph

Machine reading systems typically do not consider logical entailment concerning the logical properties of the predicates they detect. Consequently, the extraction graph may be incomplete regarding knowledge that could be inferred by applying simple logic.

Therefore, it is essential to consider the semantic domains of a dataset and the different categories of meaning present within it. The predicates in Table 1 can be subgrouped into broad semantic categories of causal, associative, and subsumptive predicates. For example, causal predicates such as CAUSES describe a cause-and-effect relationship between two entities. In comparison, associative predicates such as ASSOCIATES_WITH and COEXISTS_WITH describe a relationship in which two entities are frequently found together. On the other hand, subsumptive predicates such as PART_OF describe relationships in which one concept is in a hierarchical (“AD IS_A dementia”) or a mereological (from the Greek μερος, ‘part’) part-whole relationship77,78 with another.

The logical properties of predicates are essential for knowledge representation and inference, especially in machine reading. Predicates belonging to the causal, associative, and subsumptive categories possess logically defined properties such as transitivity, symmetry, asymmetry, and reflexivity that enable the reasoning and inference of new knowledge about relationships between entities. We can derive additional knowledge from the data through inferences by utilizing these logical properties. Detailed operation definitions and examples of these properties may be found in File I., Background S2. Logical properties.

To exploit these properties and logically infer entailed but missing triples, we mapped a subset of the machine readers’ predicates to their logical definition in terms of its logical properties using the logical definition from the object properties in the Relation Ontology (RO)79. The UMLS to RO mappings are available in file II., Table S1. and the analyses of logical properties of the predicates in Table 1 are in file IV predicatePropertyAnalysis.xlsx for each machine reading system.

We then used the transitive, symmetric, asymmetric, reflexive, and inverse properties present in RO in a procedure to infer new triples entailed by the extraction graph80,81. This procedure entails loading the initial extraction graph into the CLIPS forward-chaining production rule system 82 (https://clipsrules.net/) via the CLIPSPy Python library66. Simple rules using symmetric and transitive relationships belonging to RO predicates were applied to infer new triples and add them to the extraction graph. The CLIPS inference engine also tracked belief scores to manage uncertainty about the validity of inferred triples. New triples inferred from symmetric inference were assigned the same belief score as the asserted triple. The inference engine multiplied the belief score for each of the two asserted triples in transitive inference and assigned it to the inferred triple. All triples inferred from transitivity with a belief score of 0.6 were filtered out. The value 0.6 was chosen as a heuristic threshold to mimic a weakened transitivity property83, limiting transitive inference beyond one hop. For example, recalling that SemRep triples were assigned a belief score of 0.8, the first inferred triple from a transitive SemRep predicate would be retained because, through the application of the chain rule where each node is dependent on the previous nodes, 0.8 * 0.8 = 0.64. Subsequently, inferred triples would be filtered out since 0.8 * 0.8 * 0.8 < 0.6.

2.4. Constructing the KG

Phenotype Knowledge Translator (PheKnowLator) is an Ecosystem and Python 3 library designed to construct semantically rich, large-scale biomedical KGs from biomedical ontologies and complex heterogeneous data84. We cloned the PheKnowLator 2.0 code and ran the ontology hygiene and data preparation documented in the project’s Jupyter workbooks. PheKnowLator merged several ontologies represented using OWL85 related to genes, diseases, proteins, chemicals, vaccines, and other ontologies of biological interest. These ontologies are enumerated in Listing 1. Complete information about the resources used in PheKnowLator (version 2.0) is available on GitHub86. Each class in the ontologies merged by the PheKnowLator process formed nodes in the KG. Thus, the object properties assigned to each class formed an edge in the KG. The edges were extended by integrating data sources that connected classes using object properties provided by the RO79. Finally, the resulting KG was saved as an OWL ontology and a Python NetworkX graph object87. For more information on the Jupyter notebook, the mapping, and logical closure, see File VII. Appendix_C.docx.

Highlights.

Knowledge of causal variables and their roles is essential for causal inference.

We show how to search a knowledge graph (KG) for causal variables and their roles.

The KG combines literature-derived knowledge with ontology-grounded knowledge.

We design queries to search the KG for confounder, collider, and mediator roles.

KG search reveals variables in these roles for depression and Alzheimer’s disease.

2.4.1. Combining the Extraction Graph with PheKnowLator

Several steps were required to integrate the extraction graph with the PheKnowLator KG so that we could study its application in causal feature selection. The first step was to map the UMLS concept unique identifiers in the SemRep output to the OBO Foundry identifiers used by the PheKnowLator KG. We used existing mappings in the UMLS for the Gene Ontology and Human Phenotype Ontology classes supplemented by a query of the Bioportal Annotator service for other ontologies81. The REACH machine reader automatically generated mappings to OBO Foundry identifiers which we then added to a mapping table. We also mapped SemRep predicates to the RO version used by the PheKnowLator workflow as SemRep predicates when those predicates were not present in the RO.

2.4.2. Reweighting the edges to support path search

The PheKnowLator KG had features deriving from the knowledge representation that made querying and path search challenging without further processing. The downstream use of the weighting scheme described in this section was to influence the shortest path and simple path searches so that they would include fewer edges and nodes that were present in the knowledge graph to support OWL semantics and more edges and nodes that were biologically interesting. The ontologies were written in the OWL description logic language, which uses logical statements to define the semantics of ontology entities. Our approach used a reweighting procedure to distill the KG into biologically meaningful entities useful for our study. Therefore, we used the following steps and heuristics to remove OWL semantic statements and reweight the edges of the KG:

Apply OWL-NETS to the KG to simplify Web Ontology Language (OWL)-encoded biomedical knowledge into an easier-to-use network representation. OWL-NETS replaced the more complex logical statements with simpler triples without losing biologically relevant information (for examples, see https://github.com/callahantiff/PheKnowLator/wiki/OWL-NETS-2.0)88.

Remove all KG edges that specify a disjoint relationship between a subject and object in a triple. A disjoint relationship in OWL specifies that the class extension of a class description has no members in common with the class extension of another class description81. While disjoint relationships are helpful for deductive closure of the KG using a description logic reasoner, they lead to uninformative results from a path search that seeks a mechanistic explanation.

Remove all edges in the KG that specify the domain of a relationship from the RO. Many RO relations specify the ontology classes that comprise the relations’ domain and range. Like the disjoint relationships mentioned earlier, including these edges helps maintain logical consistency during deductive closure but leads to uninformative results from a path search that seeks a mechanistic explanation.

- Reweight each edge in the graph to influence the path search on predicates useful for mechanistic explanations. The weighting strategy is based on observing the method used in PheKnowLator to represent triples of value for constructing a mechanistic explanation explained below:

- Assign default edge weights. Since the PheKnowLator KG is not weighted by default, start by assigning a default weight of 2 to all edges. The value of 2 has no special significance except a value greater than 0.

- Favor hierarchical relationships. Hierarchical relationships can be very informative for mechanistic explanations. Most of the classes represented in the ontologies that have been merged are hierarchical and are represented using the rdfs:subClassOf predicate. If a predicate relates a subject to an object by rdfs:subClassOf: weight = 0. Assignment of subClasOf weights to zero lowers the cost of including a hierarchical edge in a path search through the KG, which increases the prevalence of hierarchical edges in path search results.

- Favor edges providing a mechanistic triples RO. We developed a simple heuristic to produce mechanistic triples and avoid triples that provide meta-knowledge about entities in an ontology. If the predicate relates a subject to an object by owl:someValuesFrom: weight = 0. Similarly, if the object is a RO entity and the predicate is owl:onProperty: weight = 0.

- Disfavor subjects and edges that primarily describe metadata. If the subject is a RO entity or the edge is owl:equivalentClass: weight = 5.

The procedure above aims to prune the KG components that are not useful for inferring biological mechanisms and to optimize the KG for providing explanations of links between biomedical entities in terms of the underlying molecular mechanisms based on information contained in the biomedical ontology inputs.

Finally, we created two copies of the PheKnowLator KG - one that was loaded into a graph data store (OpenLink Virtuoso version 7.2089) so that it could be queried using the SPARQL graph querying language, and the other that was saved as a Python NetworkX MultiDiGraph object for the application of path search algorithms. The extraction graph was loaded into the same graph data store as the PheKnowLator KG for querying.

2.5. Searching the KG

A primary objective of this paper is to identify possible confounders, colliders, and mediators from the KG search. Hence, identifying the variables that belong to each causal role constitute the competency questions. To answer these competency questions, we translated the standard epidemiological criteria for these variables into discovery patterns, or semantic constraints we use to identify variables of interest. We used these discovery patterns as requirements to construct queries implemented in the SPARQL graph querying language. The SPARQL queries are described in more detail in the paragraphs below. Table 2 presents each causal role as a competency question with its associated discovery pattern. Note that each dyad in the discovery patterns also implies chains of causation, i.e.,”A INTERACTS_WITH B CAUSES_OR_INFLUENCES_CONDITION C.”

Table 2.

Summary of the competency questions and discovery pattern approach to finding answers via KG search. The left column enumerates the competency questions, and the right column describes the graph search for answering the competency questions identifying confounders, colliders, and mediators.

| Competency questions | Discovery patterns |

|---|---|

| 1. What are the potential confounders of depression and AD? | confounder CAUSES depression; confounder CAUSES AD. |

| 2. What are the potential colliders of depression and AD? | depression CAUSES collider; AD CAUSES collider. |

| 3. What are the potential mediators between depression and AD? | depression CAUSES mediator; mediator CAUSES AD. |

KG search was implemented using Dijkstra’s shortest path search over the KG based on queries in the SPARQL graph querying language. Dijkstra’s shortest path algorithm was used to identify the shortest paths between nodes of interest in the KG. We chose Dijkstra’s shortest path algorithm as a simple way to test proof-of-concept, though there are many other graph search methods. The Dijkstra algorithm is a variant of the best-first search that prioritizes finding the shortest path between potential nodes. (Note that many paths are of the same length.) For more information on the SPARQL queries and to inspect the raw output from running the queries, see File VII. Appendix_C.docx.

The KG search was comprised of two stages. In the first stage, the KG search was implemented as Dijkstra’s shortest path search over the KG based on a query in the SPARQL over the extraction graph. Recall that the extraction graph was the subgraph of the KG containing the literature-derived triples and edges inferred from the logical closure procedure. The purpose of the first stage is to use the concepts identified by machine reading plus the inferred edges to expand the breadth of variables, i.e., improve the completeness of the machine reading outputs.

In the second stage, the query uses the results from the first stage query are used (represented universal resource identifiers or URIs) as the start and end nodes for the input (as the start and end nodes) of the queries over the ontology-grounded KG. The purpose of this stage was to filter the literature-derived information through the ontology-grounded knowledge with the goal of improving accuracy over the literature-derived knowledge. Our discovery pattern-based KG search implementation is constrained to subsumptive and causal predicates. The causal predicates include CAUSES_OR_CONTRIBUTES_TO_CONDITION, GENETICALLY_INTERACTS_WITH, and MOLECULARLY_INTERACTS_WITH. These ontology-based predicates were chosen because they describe mechanistic causal links between disease and the genomic and biomolecular entities and processes essential for our use case.

To provide hypothetical explanations of the causal association between identified variables and depression and Alzheimer’s disease (AD), our KG search implementation traced the path of nodes and predicates traversed by Dijkstra’s shortest path search algorithm. These paths, which we refer to as reasoning paths, reveal the causal relationships and ontological links between concepts and allow us to derive an explanation linking biochemical processes with molecular definitions of disease from combined literature- and ontology-derived structured knowledge.

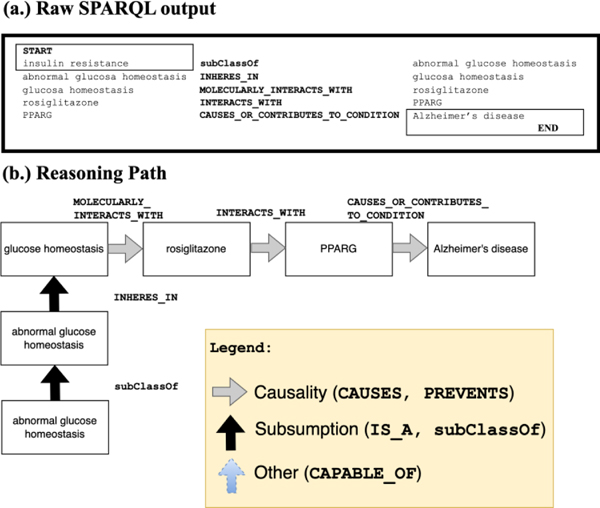

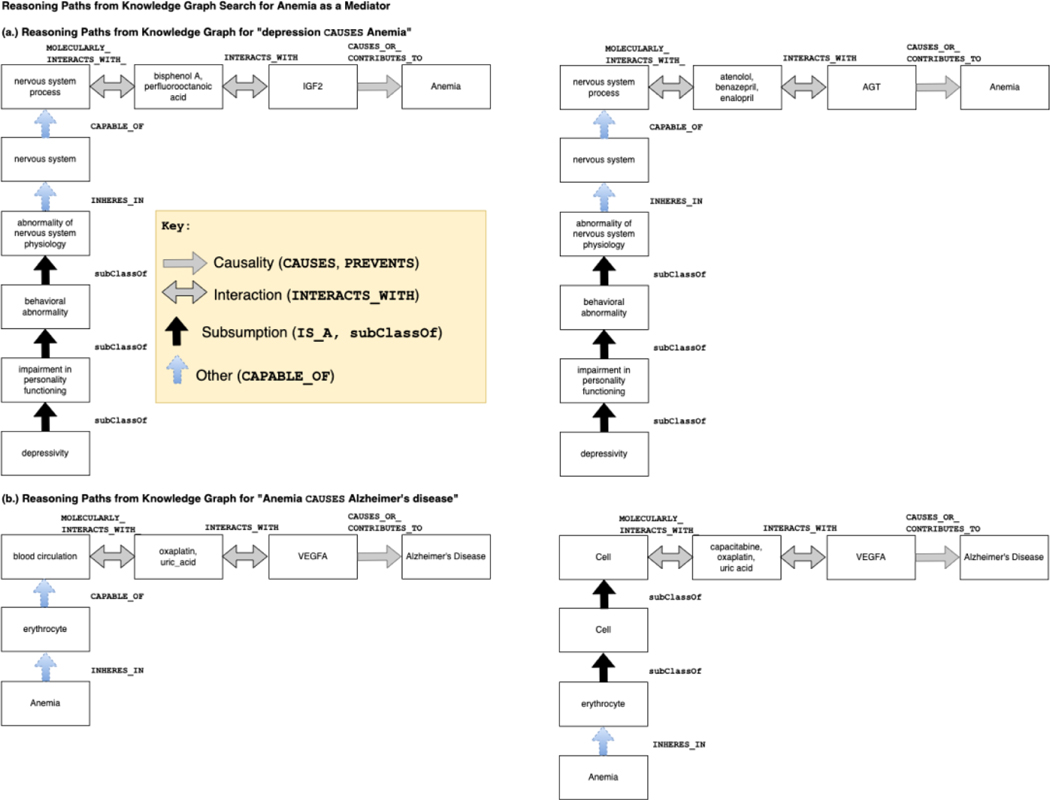

We created visualizations of the reasoning paths to facilitate the analysis and interpretation of the variables. As an illustration, Figure 3 presents a sample reasoning path in its raw form as output from the KG search and in its transformed format that includes ontological and causal predicates. The transformed format provides a clear and intuitive representation of the relationships and causal links uncovered through the KG search process. These visualizations provide hypothetical mechanistic explanations for the causal role played by each variable in the identified associations according to these reasoning paths. Overall, by tracing the reasoning paths and creating visualizations, we can provide hypothetical explanations of the causal associations between the identified variables and depression and AD.

Figure 3.

This figure shows two versions of a SPARQL query’s (partial) output. (a.) shows sample raw output from the SPARQL query, and (b.) shows a visualization we manually created from the output. Note that the visualization displays hierarchical (IS_A), mereological (from the Greek μερος, ‘part’), e.g., PART_OF, HAS_PART, relationships vertically, and causal relationships (INTERACTS_WITH, CAUSES_OR_CONTRIBUTES_TO_CONDITION) vertically.

Throughout the article, we will present reasoning paths where they serve as useful visual representations of the relationships and causal links discovered in our KG search.

2.6. Causal Feature Selection (Evaluation)

Our evaluation procedure is summarized here and described in more detail in the paragraphs below:

Present KG search results for confounder, collider, and mediator variables for depression and AD (partially answering H1). We conducted a KG search to identify the confounders, colliders, and mediators of depression and AD and reported the KG search results and sample reasoning paths.

Display the KG search results as causal diagrams in two forms: simple roles and combination roles (partially answering H1 and H2). In addition to the simple roles of confounder, collider, and mediator, our methodology allows for the identification of variables with complex behavior, referred to as combination roles, which are additional role categories for variables with more than one causal role, and include confounder/mediators, confounder/colliders, and confounder/mediator/colliders. These variables with combination roles were identified using set operations, such as set difference and intersection, on the list of variables for each role type.

Compare the KG search results with SemMedDB and reported covariates in published observational studies using Venn diagrams (partially answering H1 and H2). We compared the KG search results with results from searching the SemMedDBScoped and SemMedDBComplete databases to understand the differences between our novel feature selection and complementary methods for causal feature selection, including the consistency with which concepts are classified by their causal role(s). The search results for simple and combination roles were summarized. Additionally, we compared the KG and SemMedDBComplete with confounders reported in a small database of confounders from a pilot-metareview. For more information on the SQL queries, see File VII. Appendix_C.docx.

Prioritize and conduct in-depth analysis on a subset of variables (partially answering H1, H2, and H3). A subset of the variables was selected for in-depth analysis to prioritize the results of the KG search. This in-depth analysis aimed to provide further insight into the search results’ veracity and the reasoning paths’ usefulness (H3).

As noted earlier, we compiled a database of confounders from a pilot meta-review of confounding control. More information, including details on the pilot meta-review, is provided on each step below.

2.6.1. Confounders, colliders, and mediators KG search

We report the confounders, colliders, and mediators for depression and AD identified by searching the KG. To show the feasibility of our pilot project, KG search should be able to identify causal variables playing each role, and thereby demonstrate competency.

2.6.2. Analysis of search results

In addition to the pre-defined, “simple” roles (confounder, collider, and mediator, mentioned earlier), our compilation procedures allow us to identify variables with complex behavior, i.e., “combination” roles, which we define as additional role categories for variables with more than one causal role. The combination roles included confounder/mediators, confounder/colliders, and confounder/mediator/colliders. Our rationale was to sort out the roles played by the variables and identify variables with complex behavior of which other researchers ought to be aware. The combination roles were identified using set operations, e.g., set difference and intersection, over the list of variables for each role type. For example, to identify “Confounders only” variables, we perform a set difference operation over the set of confounders minus the set of variables appearing in the collider, mediator, or both KG search result sets.

2.6.3. Comparing search results

We sought to understand how our novel feature selection differs from complementary methods for causal feature selection using SQL queries to identify relevant variables from the literature explored in previous research and with confounders reported in published observational studies investigating depression as a risk factor for AD or dementia. To this end, we compared the KG search results with results from searching the original scoped predictions in MachineReadingDBScoped and SemMedDBComplete. MachineReadingDBScoped contained the original subset of structured knowledge restricted to human clinical studies on AD published in 2010 or after that we used to construct the extraction graph. SemMedDBComplete contained the entire database of SemRep predicates extracted from titles and abstracts of articles published in 2010 or after. We summarized the search results for simple and complex roles as we did in the previous subsubsection. To gain insight into the veracity of our search results, we also conducted a comparison of search results for confounders with confounders reported in the literature. Such a comparison hinges on the existence of a database of reported confounders in the published literature. However, no such standardized and validated causal question-specific confounder database exists. Fortunately, however, we have been developing just such a confounder database in parallel research.

In the pilot meta-review, we manually collected from a small corpus of observational studies investigating depression as the exposure and dementia or AD as the outcome. We based on recommendations from the Cochrane Group90. Confounders appearing in the search results that were already recognized in the pilot meta-review of the literature partially validate the soundness of our methods. Information on confounders was manually collected from a small corpus of papers and entered into a spreadsheet. This small corpus included confounders reported in three papers studying depression cited by the Lancet Commission Report (LCR) on late-life modifiable risk factors for dementia53. We reason that papers cited in the LCR should be of relatively high quality. Additional reported confounders from four sporadically collected papers over the course of our research. We also collected information on each paper’s exposure and outcome definitions included in the corpus. In this way, we could ensure that only confounders specific to depression and dementia or depression and AD were included in our database. Hence, while the corpus of papers analyzed is small and the scoping strategy was not systematic, reflecting the preliminary stage of this research, which focused on the feasibility of building such a database rather than exhaustiveness, the confounders in the database can be assured to be accurate and reflective of confounders recognized as such by human content-matter experts.

Finally, we compiled the reported confounders into a set containing each confounder to execute the comparison.

Confounders appearing in search results that have already been recognized as such partially validate the soundness of our methods. Search results that do not appear in the literature may indicate that the search results are erroneous or that the search-identified confounder may have been overlooked. Alternatively, since our data collecting strategy was not systematic, our confounder database is not comprehensive. Hence, certain reported confounders may be missed, and potential confounders appearing in the search may not be novel confounders after all.

2.6.4. In-depth analysis

In our study, we conducted several additional posthoc analyses on a set of variables obtained from a Knowledge Graph (KG) search. Due to the large number of variables identified through the KG search, we prioritized the subset of variables to be analyzed in-depth based on several criteria, including the potential to address confounding bias, the strength of the relationship as indicated by the strength of the association, scientific interest, and degree of surprise (a concept not present in pilot meta-review but present in the KG and SemMedDBComplete, or present but with conflicting assertions causal directionality).

One of the human experts who conducted the verification procedure (CES, with expertise in the population neuroscience of ADRD) was a content expert in Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (ADRD). The other human expert (HTK) has expertise in bioengineering and focuses on the biology of brain aging.

The human experts examined the source sentences from SemMedDB along with the reasoning paths produced by the KG search for those variables. The task was then to determine if the claims asserted by the KG and SemMedDBComplete, i.e., the source sentences from SemMedDB along with the reasoning paths produced by the KG search, were consistent with a combination of the human expert’s background knowledge and information gleaned performing additional searches in PubMed to fill in any gaps in their understanding.

In summary, after prioritizing a subset of variables for further examination, the post hoc analysis performed in our study aimed to verify the validity of selected confounders through a human expert-based verification procedure.

3. Results

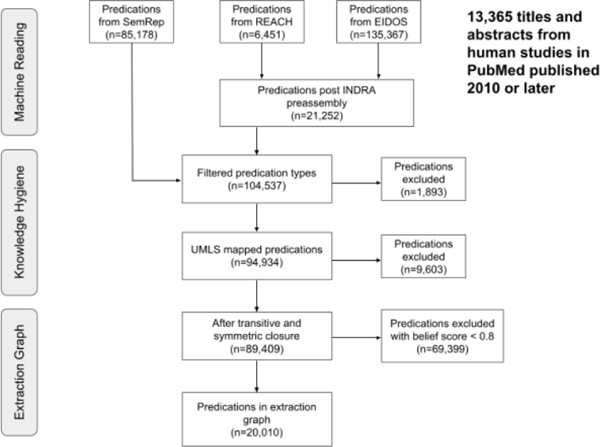

Figure 4 shows the result of applying post-processing procedures to the extracted triples. 13,365 PubMed-indexed articles were returned from PubMed, resulting in 226,997 triples from machine reading. The number of triples remaining after executing the knowledge hygiene procedure was 94,934, or 41.8% of the original triples. The subject and object entities of the entire set of triples included 10,020 unique UMLS CUIs, of which 2,504 were mapped to ontological identifiers and merged using the PheKnowLator workflow (2,110 from Bioportal, 844 from the Gene Ontology91,92 and Human Phenotype Ontology93 mappings present in UMLS, and 394 from REACH). After filtering out the machine reading and inferred triples with a belief score of < 0.8 and mapping predicates to the RO, the total number of machine reading triples was 20,010, or 8.8% of the original total.

Figure 4.

This figure illustrates merging the outputs from the machine reading systems, performing knowledge hygiene, and applying logical closure operations on the extraction graph.

The KG from the PheKnowLator workflow contained 18,869,980 triples. Table 3 shows the counts of inferred edges by predicate type. The most significant gains by predicate type CAUSES_OR_CONTRIBUTES_TO_CONDITION yielded the most novel inferred causal edges, followed by CAUSAL_RELATION_BETWEEN_PROCESSES. There were zero inferred edges for certain other predicate types because we did not define the logical properties of those predicates to allow for inference. Table 4 shows the count of edges for four triple types relating genes or variants of genes to health conditions.

Table 3.

Counts of triples inferred using the logical closure operations given the symmetric and transitive properties of the literature-derived predicates from machine reading. Transitive and symmetric closure produced 73,046 triples after filtering out inferred triples with a belief score of < 0.6 and those without a mapping to the RO.

| Predicate Type | Machine Reading | Inferred | Symmetric (yes/no) | Transitive (yes/no) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAPABLE_OF_INHIBITING_OR_PREVENTING PATHOLOGICAL_PROCESS | 683 | 0 | No | Yes |

| CAUSAL_RELATION_BETWEEN_PROCESSES | 3,103 | 20,945 | No | Yes |

| CAUSES_OR_CONTRIBUTES_TO_CONDITION | 2,003 | 45,697 | No | Yes |

| CORRELATED_WITH | 3,000 | 3,000 | Yes | No |

| EXISTENCE_OVERLAPS_WITH | 2,528 | 2,528 | Yes | No |

| INTERACTS_WITH | 1,236 | 1,236 | Yes | No |

| INVOLVED_IN_POSITIVE_REGULATION_OF | 457 | 0 | No | No |

| IS_SUBSTANCE_THAT_TREATS | 2,647 | 0 | No | No |

| MOLECULARLY_INTERACTS_WITH | 7 | 0 | No | No |

| NEGATIVELY_REGULATES | 816 | 0 | No | No |

| PART_OF | 1,355 | 6,929 | No | Yes |

| PHOSPHORYLATES | 18 | 0 | No | No |

| PRECEDES | 136 | 313 | No | Yes |

| REGULATES | 3,512 | 0 | No | No |

Table 4.

The count of four causal predicates in the KG produced by PheKnowLator after running OWL-NETS.

| Predicate Type | # of triples |

|---|---|

| CAUSES_OR_CONTRIBUTES_TO_CONDITION | 113,837 |

| MOLECULARLY_INTERACTS_WITH | 5,678,829 |

| GENETICALLY_INTERACTS_WITH | 3,246,417 |

Note that we did not collect detailed, precise runtimes for these analyses. All analyses were performed on modest hardware configurations. The execution of the INDRA machine reading component took several days. The post-processing of the SemRep and INDRA outputs took minutes. The construction of the knowledge graph took days. Finally, the execution of all of the SPARQL queries took several hours on the modest hardware.

3.1. Answering competency questions

3.1.1. Question #1 - What are the potential confounders of Depression and AD?

The KG search found 126 unique variables potentially confounding the association between depression and AD, including 47 conditions or phenotypes, 43 drugs, and 35 genes or enzymes. Examples included apolipoproteins, arachidonic acid, chronic infectious disease, encephalopathies, estradiol, hypercholesterolemia, hypoglycemia, inflammatory response, interleukin-6, myocardial infarction, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. (The KG search found 141. Fifteen of the 141 confounders appeared to be redundant, e.g., vascular endothelial growth factor A (PR_000017284) and vascular endothelial growth factor A (human) (PR_P15692)). However, according to PRO, these concepts are not the same. The human version (PR_P15692) is a child of (PR_000017284), so we retained both in the KG. For the purposes of reporting in the tables, we have merged these concepts.

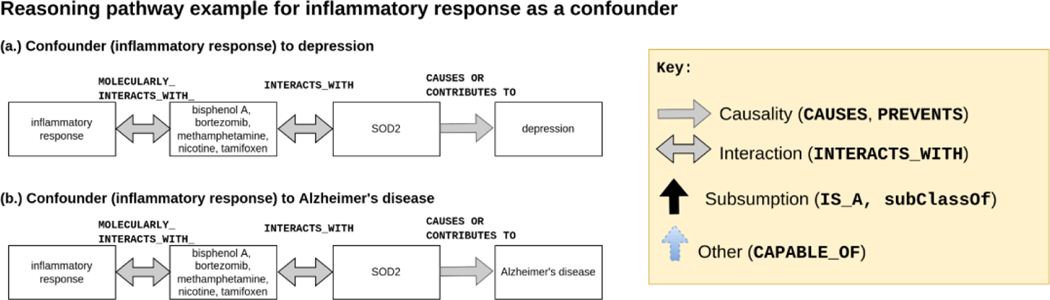

The shortest path lengths returned by Dijkstra’s path search algorithm varied from 2 (15 paths from a confounder to depression / 16 paths from a confounder to AD) to 9 (2 paths, both from confounder to depression or confounder to AD). The paths for the confounder with the longest path lengths (statin (CHEBI_87631)) included paths that passed through the hub molecular entity (CHEBI_23367). The majority of confounders had paths to depression or AD with 4 or fewer path lengths (77 paths with <= 4 steps to depression and 80 paths with <= 4 steps to AD). Figure 5 depicts the reasoning path for inflammatory response.

Figure 5.

Sample reasoning pathway of inflammatory response, a confounder identified by KG search. Note that the y-axis is the TYPE_OF/subsumption axis. The x-axis is the CAUSES/INTERACTS_WITH axis. SOD2 is superoxide dismutase 2, a gene that encodes a mitochondrial protein. SOD2 is associated with diabetes and gastric cancer94. SOD2 polymorphisms are associated with neurodegenerative diseases, including cognitive decline, stroke, and AD95,96. SOD2 is a gene that scavenges for reactive oxygen species (ROS) resulting from environmental exposures, e.g., bisphenol A, that result in inflammation97. Bisphenol A is found ubiquitously in plastics and is ingested from water bottles, packaged food, and many other sources98–100.

3.1.2. Question #2 - What are potential colliders of Depression and AD?

The KG search found 28 unique potential colliders for depression and AD. These included amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, anemia, apraxias, atherosclerosis, brain hemorrhage, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, cerebrovascular accident, congestive heart failure, deglutition disorders, dementia, diabetes mellitus, diabetes mellitus, non-insulin-dependent, encephalitis, falls, frontotemporal dementia, homeostasis, immune response, insulin resistance, ischemic stroke, malnutrition, neurofibrillary degeneration (morphologic abnormality), osteoporosis, parkinsonian disorders, pathogenesis, pneumonia, psychotic disorders, senile plaques, stroke, and tauopathies.

Note that in the list of colliders above, the KG search identified as potential colliders several variables we have emphasized by italicizing and underlining. The KG may have inferred dementia because AD is a specific dementia etiology. Homeostasis may have been included in the results as a generic biological process that was not filtered out. Finally, it would not make sense that AD would cause frontotemporal dementia, the most common dementia in patients younger than 60. We drop supercategories like dementia and generic processes like homeostasis for our analysis since these can be easily identified and explained away from context as spurious.

There were two colliders identified using SPARQL for which no path could be found from depression to the collider in the KG created using the PheKnowLator workflow (falls (HP_0002527) and neurofibrillary tangles (HP_0002185)). Two of the 26 colliders with paths from depression in KG had multiple identifiers (cerebral amyloid angiopathy (HP_0011970 and DOID_9246) and frontotemporal dementia (DOID_10216, DOID_9255, and HP_0002145)). Path search identified a total of 29 collider entities in KG.

For depression to the colliders, the path lengths of the shortest paths returned were 7 steps for 2 colliders, 8 for 26, and 9 for 1. The majority of colliders (24) resulted in 5 or more shortest paths returned. For AD to the colliders, the path step counts were slightly lower at 6 steps for 2 colliders, 7 for 26 colliders, and 8 for 1 collider. Similar to depression, 23 colliders have 5 or more shortest path lengths from AD.

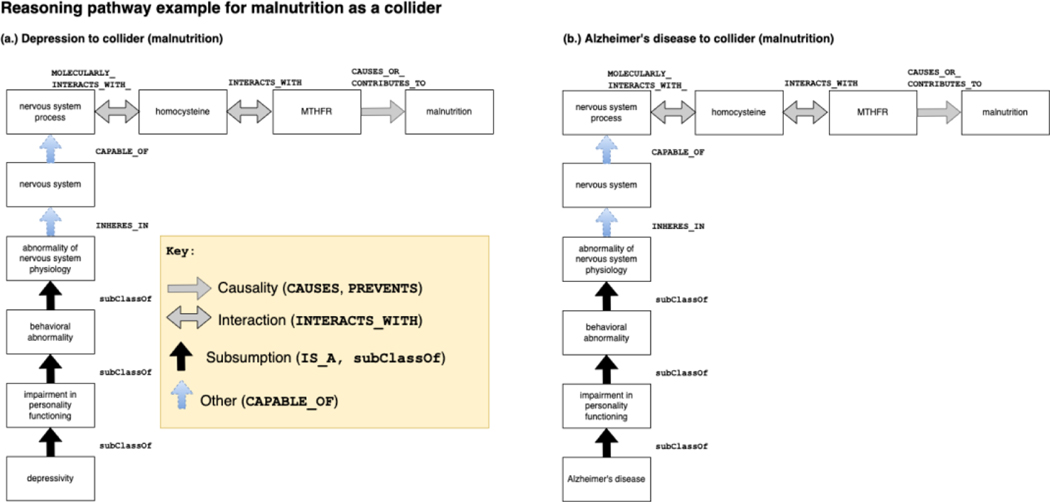

As shown in Figure 6 below, the typical path pattern for both cases involved passing through the hub node nervous system (UBERON_0001016) and nervous system process (GO_0050877) that molecularly interacts with a drug or chemical that also interacts with a gene that causes or contributes to AD.

Figure 6.

Sample reasoning pathway of malnutrition, a collider identified by KG search. The MTHFR gene is a gene that encodes the Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) enzyme that is critical for the metabolism of amino acids, including homocysteine101. MTHFR perturbations and mutations decrease the metabolism and elevate homocysteine. Elevated homocysteine is linked with blood clots and thrombosis events102–104. Homocysteine has been reported in the published literature as a confounder of depression and AD in at least one observational study105. Elevated homocysteine is also associated with low levels of vitamins B6 and B12 and folate.

3.1.3. Question #3 - What are the potential mediators of Depression and AD?

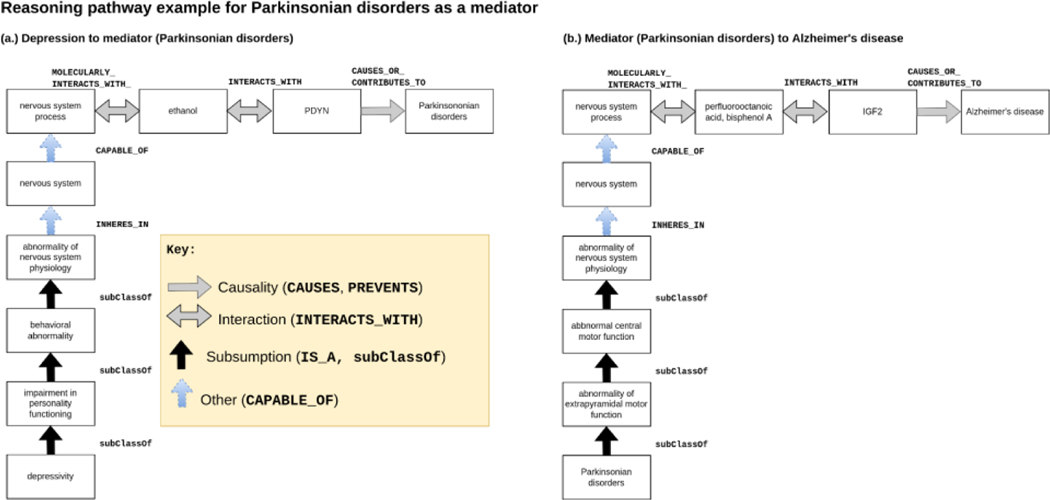

The KG search found 18 unique potential mediators that were conditions or phenotypes for depression and AD. These included amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, anemia, atherosclerosis, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, cerebral hemorrhage, congestive heart failure, dementia, diabetes mellitus, dysphagia, insulin resistance, ischemic stroke, malnutrition, osteoporosis, parkinsonism, pathogenesis, stroke, tauopathy, type II diabetes mellitus. The shortest path lengths from Dijkstra’s path search algorithm were 8 for depression to mediators. There is more variety in path length from mediators to AD, with most path lengths between 4 and 6. As is shown in Figure 7 below, the typical path pattern for both cases involves associating the disorder (depression or a mediator) with a nervous system process that molecularly interacts with a chemical that causes or contributes to AD.

Figure 7.

Sample reasoning pathway of Parkinsonian disorders, a potential mediator for AD identified by KG search. Prodynorphin (PDYN) is a gene that produces endogenous opioid peptides involved with motor control and movement106 implicated in neurodegenerative diseases that modulate response to psychoactive substances, including cocaine and ethanol107. The gene insulin growth factor 2 (IGF2) is associated with development and growth. Perfluorooctanoic acid and bisphenol A exposure is associated with neurodegeneration resulting in AD108. Hippocampal IGF2 expression is decreased in AD-diagnosed patients109. Increased IGF2 expression improves cognition in AD mice models110.

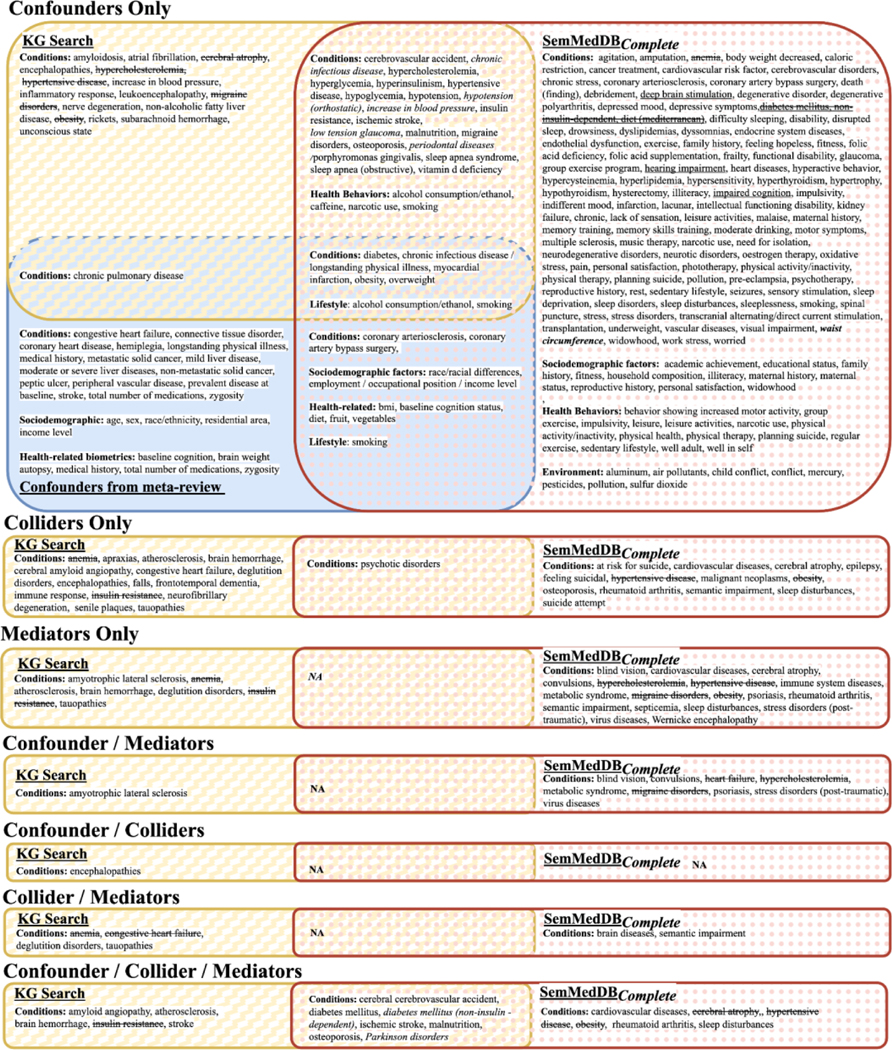

3.2. Analysis of search results by causal role

3.2.1. Simple roles

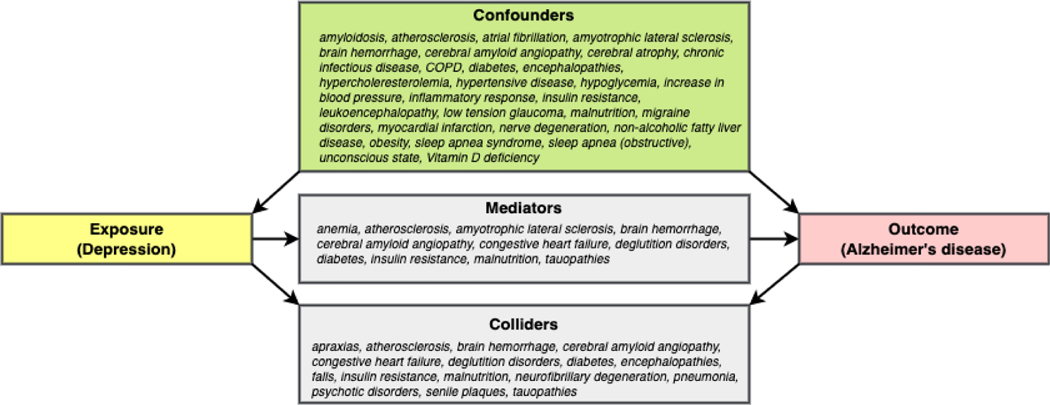

Figure 8 illustrates the phenotype variables produced from our KG search. Aside from the conditions we analyzed, the KG search also identified pharmaceutical substances, genes, and enzymes as confounders. However, the shortest path parameters produced no search results from our queries for colliders and mediators belonging to those semantic categories. Note also the same pattern was observed searching SemMedDB. We report the complete set of variables the KG identified in the spreadsheet in the Supplementary Materials in File III., Worksheet S2, and Worksheet S3. (see the worksheets entitled “Substances” and “GenesEnzymes,” respectively), and in File II. Appendix B. Figures S1 and S2.

Figure 8.

This diagram shows the variables identified using their causal roles relating to depression and AD by translating standard epidemiological definitions into patterns for querying the KG.

3.2.2. Complex roles

Figure 9 illustrates the same conditions from Figure 8, albeit in a more distilled form since we distinguish between variables playing single versus the different categories of combination roles. Twenty-two distinct confounders and nine colliders were found to behave solely in one role. The KG search could not find any variables that behave exclusively in the role of mediator. The rest of the variables fulfilled two or more causal roles. Of these, 11 variables fulfilled the criteria of all three causal roles.

Figure 9.

This diagram shows variables according to their roles, including single and hybrid role types for the relationship between depression (exposure) and AD (outcome). Each rectangular box in the figure lists all the conditions by single role (confounder, collider, or mediator) or combination roles (e.g., mediator/collider). For example, the box labeled “Confounders only” contains covariates that are exclusively confounders and were not found to act as a collider or a mediator.

Note that the graphs in Figures 8 and 9 are not, strictly speaking, causal DAGs since they depict cycles. Since causal DAGs cannot represent cyclic relationships, new graph formalisms can represent latent variables and cycles (feedback loops) by generalizing the causal interpretation of DAGs, e.g., directed mixed graphs (DMGs)111, chain graphs112.

3.3. KG vs. SemMedDB and reported covariates in the published literature

Table 5 shows the confounders from the pilot meta-review of reported confounders we gathered from human observational studies investigating depression as the exposure and dementia or Alzheimer’s disease as the outcome. About half of the studies were prospective cohort studies. The other study designs used were case-control and using twins for controls. We looked at studies at AD-specific studies, to see if there were differences between those used mainly from dementia-focused studies below, but could not find any major differences.

Table 5.

Reported confounders from published studies investigating depression and AD (or dementia) from our pilot meta-review.

| PMID | Exposure | Outcome | Confounders |

|---|---|---|---|

| 27138970113 | depression | dementia | age, sex, APOEɛ4 carrier status, educational level, BMI, smoking, alcohol consumption, cognitive score, antidepressant use, and disease status at baseline |

| 33726788114 | depression and cerebrovascular disease | dementia | age, sex, residential area, income level, comorbidities (myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, chronic pulmonary disease, connective tissue disorder, peptic ulcer, mild liver disease, uncomplicated and complicated diabetes, hemiplegia, non-metastatic solid cancer, moderate or severe liver diseases, metastatic solid cancer) |

| 23154050115 | depression, mediated by AD pathology | AD | baseline cognition, age, education, the total number of medications, and brain weight at autopsy |

| 28514478116 | depression | dementia | age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, occupational position, smoking, longstanding physical illness, fruit and vegetable consumption, diabetes, coronary heart disease, stroke, antidepressant use |

| 19485655117 | depression | dementia | age, gender, zygosity, i.e., “mono- or non-monozygotic twin status,” and years of education |

| 28463236118 | depression | dementia | age, date of birth, education, smoking, medical history |

| 27138970113 | depression | dementia | age, sex, APOe4 status, education, bmi, alcohol consumption, cognitive score, antidepressant usage, prevalence disease at baseline |

While demographic variables such as age and sex are consistently reported and there is considerable overlap between some of the covariates including APOEɛ4 status and comorbidities related to kidneys, liver, and cardiovascular systems, there is inconsistency between studies, presumably depending on whether or not data were available for these variables, a common pattern in observational studies119,120. Note that the second study in the third row of Table 5, with the many types of cancer listed as confounders, is something of an outlier.

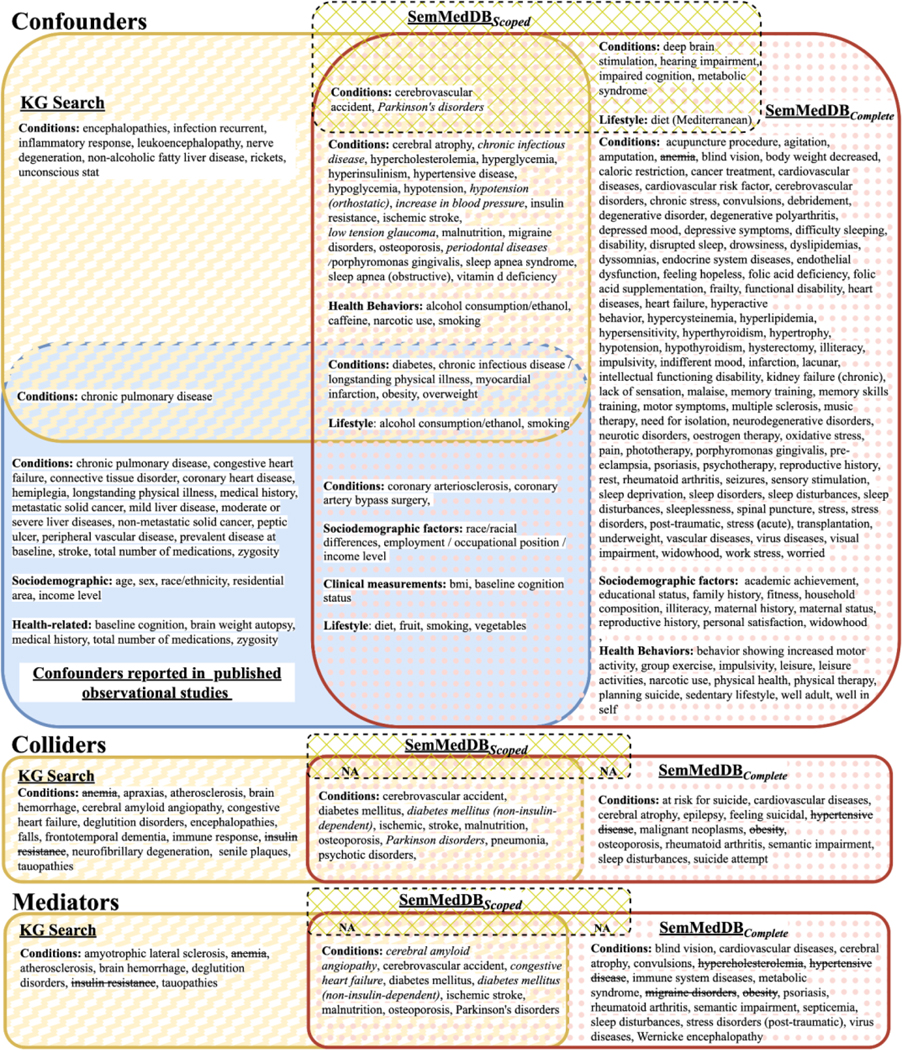

We omitted columns for the INDRA machine reading systems (EIDOS and REACH) in Figure 10 because there were no variables identified using information from those sources.

Figure 10.

This figure shows (main) condition variables/concepts for simple (not combined) causal roles from KG search in yellow, SemMedDBScoped in green diagonal and SemMedDBComplete in rose polka dot, and the confounders from the pilot-metareview in solid blue as a Venn diagram. See Appendix B. Figure S1. for the complete results, containing genes/enzymes/proteins and drugs/substances.

Only a small number of confounders appear in all sources, though many confounders appear in two sources. We see a moderately high concurrence between the KG and SemMedDBComplete, but there are curious and perhaps telling patterns. For instance, among the discordant results, there is a pattern that concerns the semantic categories of output. Specifically, SemRep had better recall performance for variables that are potentially more difficult to establish mechanistically, e.g., psychiatric symptoms (“agitation,” “dyssomnias,” “feeling hopeless”) or lifestyle factors (e.g., exercise, family history). Moreover, the concepts identified by KG search results are generally less redundant than those from searching the literature (e.g., diabetes, diabetes mellitus). Searching SemMedDBComplete yielded the most search results. Searching the KG yielded fewer search results. Searching MachineReadingDBScoped yielded still fewer results. This is not surprising since the KG was harmonized while SemMedDBComplete search was not, resulting in some concepts with multiple names.

Again, only a small number of confounders appear in all sources. Two primary patterns that stand out in Figure 11 are the relatively high degree of concordance between the KG and SemMedDBComplete regarding confounders and combination variables that play all three roles (confounder, collider, and mediator) on the one hand. Note that while there is a literature describing the three “simple” or core roles (confounder, collider, and mediator), the literature for confounder/mediator (also called time-varying confounding and treatment-confounder feedback) is the only type of combination or hybrid variable for which a literature exists14. From this point on, we call variables playing all three roles, such as stroke, chimeras. In Greek mythology, a chimera is a creature with a fire-breathing head of a lion, a goat’s body, and a snake’s tail. From the perspective of valid causal inference, the chimera is a dangerous variable category because conditioning on chimeras, like conditioning on mediators and colliders, can potentially distort measures of association or effect. Thus, chimeras are important to identify to avoid introducing bias. On the other hand, the recall performance for the other types of exclusive and the combination variable is poor. For example, anemia appears in “Mediator only” in the KG search results but in “Confounders only” in the SemMedDBComplete search results.

Figure 11.

This figure shows the (mainly) condition variables/concepts for combination causal roles from KG search in yellow, SemMedDBComplete in pink poka dot, and the confounders from the pilot-metareview in solid blue as a Venn diagram. Sec Appendix B. Figure S2. for the complete results, containing genes/enzymes/proteins and drugs/substances.

3.4. Manual qualitative evaluation of search results

In this section, we analyze five condition variables in-depth. We prioritized conditions for in-depth analysis for the following reasons. First and foremost, as noted before, conditions were the only category of biomedical entity variable identified as playing all three causal roles in both the KG search results and in SemMedDB search. Hence, phenotypes were the only category of variable we could analyze from the standpoint of untangling the complexity of combined causal roles using the reasoning path outputs. Secondly, it would have been infeasible to analyze all the variables. We had to prioritize a subset of variables. Thirdly, conditions were the most frequently reported category of reported confounder in published observational studies after sociodemographic characteristics, health behaviors, and APOEε2/3/4 status. Fourthly, our use case focused on variables that would be commonly available in an electronic medical records system, which ruled out biomarkers.

3.4.1. Confounders

The objective of this section was to provide an in-depth analysis of the evidence supporting the classification of a sample of potentially newly discovered confounders for depression and AD. The source sentences for review of three variables identified as being “confounders only” in both the KG and SemMedDBComplete: chronic infectious disease (CID), obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and vitamin D deficiency (VDD) are available in the Supplementary Materials in File V. ConfounderSourceSentences.xlsx. (Note that SQL code for running the queries with which to obtain sources sentences from SemMedDB is included in the final worksheet of File V.)

These variables were chosen for analysis because: (1.) they occurred in both KG and SemMedDBComplete, and the agreement was unanimous about their categorization (confirmation by two distinct methods); (2.) they had the most support in SemMedDB, and we could analyze the source sentences and publications supporting their categorization as confounders (amount of evidence, i.e., the # of retrieved and pertinent predications); and (3.) the practical usefulness for our use case, scientific interest, and surprise. In this case, OSA, CID, and VDD pertained directly to our use case, and had support in SemMedDB, yet, surprisingly, they did not appear in the published observational studies we examined, though our review was not comprehensive.

In the view of the content expert, all three variables seemed biologically plausible common causes of both depression and AD. OSA seemed to have the most (10 predications from 9 distinct publications supporting OSA→depression (where “→” means “CAUSES”) and 22 predications from 21 distinct publications supporting OSA→AD) and the strongest evidence browsing PubMed. The 3 strongest “OSA→depression” predications and the 2 strongest “OSA→AD” predications are marked in the spreadsheet.

While there is a larger body of evidence on infections and AD, the evidence was less extensive overall for vitamin D deficiency (2 predications from 2 distinct publications supporting CID→depression and 4 predications from 4 distinct publications supporting CID→AD).

The sentences concerning VDD also supported it as a confounder (3 predications from 3 distinct publications supporting CID→depression and 9 predications from 9 distinct publications supporting CID→AD).

Notably, however, the expert noted the difficulty in assessing the evidence quality from one sentence, and the need to drill down into the article to determine if the causal assertion was transferable. When reviewing the OSA → MDD and OSA → AD assertions, the expert noted that the various studies were all plausible and included primary studies (e.g., OSA to MDD: supported by PMID 20939075, 27631236, 33158487, 33158487 and OSA→AD supported by PMID 27070140, 28329084). In general, OSA is a well-known risk factor for both MDD and AD both clinically and in research.

3.4.2. Stroke as a chimeric variable

The source sentences from SemMedDB for stroke are included in the Supplementary Materials in File VI. ChimeraSourceSentences.xlsx. (Note that SQL code for running the queries to obtain the source sentence from SemMedDB is included in the final worksheet of File VI.)

Stroke was selected for further analysis in this study due to its frequent appearance as a confounder in reported observational studies. Despite being commonly considered a confounder without referencing stroke-subtype (e.g., see the phenotype definition for stroke from Singh-Manoux et al.116), both the KG and SemMedDBComplete search results indicated that the role of stroke might vary depending on its subtype, specifically between ischemic and hemorrhagic. These findings were further supported by the results of a PubMed search, which highlighted the potential difficulties in conditioning on stroke without considering its subtype.

Stroke was identified as a chimera by both the KG and SemMedDBComplete. The support for stroke as a chimera was substantive, though with a caveat where the interpretation of the meaning of stroke depends on the stroke subtype. To review the meaning of stroke, a stroke results from a reduced blood supply to the brain from either constriction, e.g., ischemic stroke, or hemorrhage, e.g., hemorrhagic stroke, or intracerebral hemorrhage. There are also less immediately devastating stroke-like events called transient ischemic attacks that presage future more serious stroke events. Ischemic stroke is a known risk factor for both depression121–123 and AD124–126. Although the KG search classified both stroke and the ischemic stroke subtype as chimeras, presumably including both subtypes under the umbrella term or hypernym of stroke, the evidence was stronger for ischemic stroke as a chimera. However, evidence for AD as a risk factor was weaker for ischemic than for hemorrhagic stroke125. In the meta-analysis of Waziri et al. based on four national studies and assessing the relative risk of hemorrhagic vs. ischemic stroke in AD vs. non-AD patients and applying matching criteria, the relative risk of AD patients vs. similar non-AD controls was 1.41 (95% CI 1.23–1.64) for hemorrhagic stroke but 1.15 (95% CI 0.89–1.48) for ischemic stroke. A PubMed search did not yield any specific information about the hemorrhagic stroke subtype as a confounder.

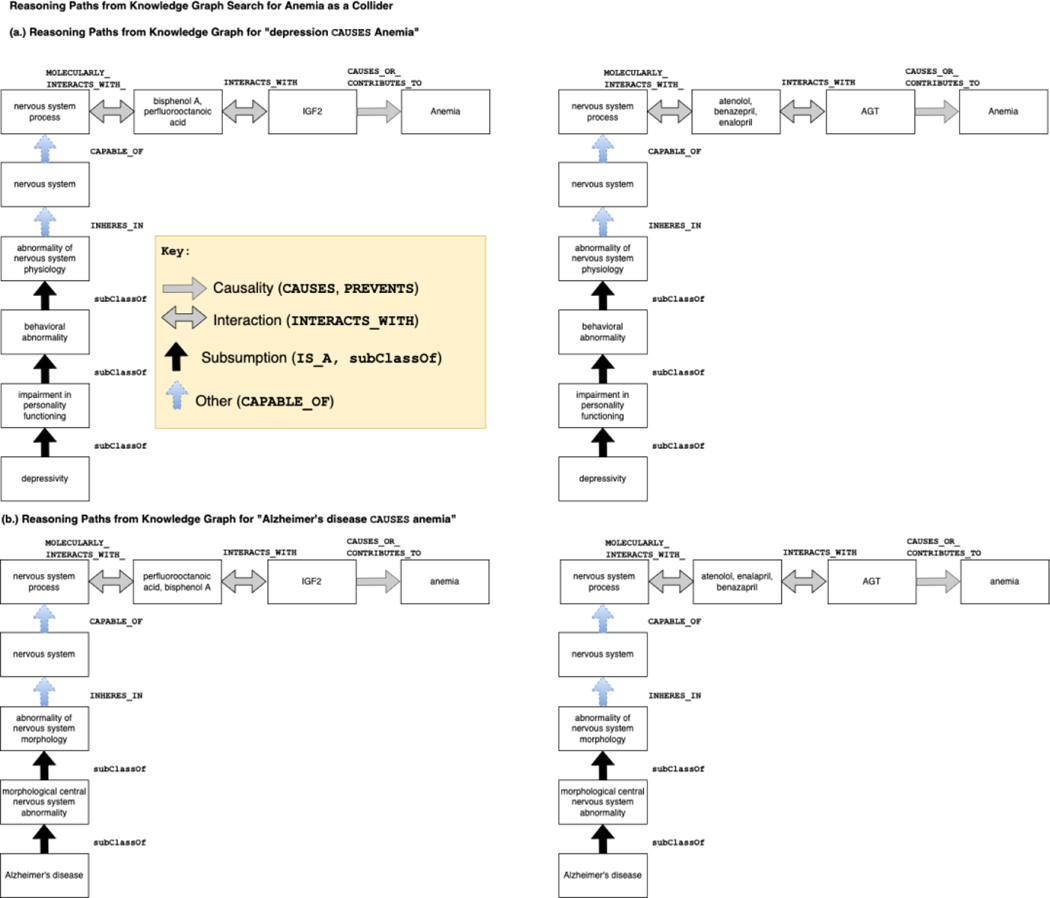

3.4.3. Resolving contradictions between SemMedDB and KG search

Anemia was selected for further analysis in this study due to its complex and contradictory relationship with depression and Alzheimer’s disease. The supporting evidence from reasoning paths, source sentences, and PubMed searches was contradictory, making it challenging to determine the exact causal role of anemia. This complexity and contradiction provided an opportunity to achieve one of the sub-goals of the paper (H3), which was to examine the causal roles of identified variables through the interpretation and evaluation of reasoning paths.

Anemia is scientifically interesting as it has been reported to have complex relationships with both depression and Alzheimer’s disease. While anemia has been reported as a risk factor for depression, some studies have also suggested that depression may lead to anemia. Similarly, while anemia has been reported to increase the risk of Alzheimer’s disease, other studies have suggested that Alzheimer’s disease may lead to anemia.