Abstract

To investigate changes in estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) signaling during progression of endometriosis to endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer (EAOC) as a driver of malignant transformation. We procured tissue samples of normal endometrium, endometriosis (benign, atypical, concurrent with EAOC), and EAOC. We evaluated expression of a 236-gene signature of estrogen signaling. ANOVA and unsupervised clustering were used to identify gene expression profiles across disease states. These profiles were compared to profiles of estrogen regulation in cancer models from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was performed to determine whether gene expression in EAOC was consistent with ERα activity. ANOVA revealed 158 differentially expressed genes (q < 0.05) and unsupervised clustering identified five distinct gene clusters. The estrogen signaling profile of EAOC was not consistent with activated ERα in pre-clinical models. Gene set enrichment analysis did not identify signatures of activated ERα in EAOC but instead identified expression patterns consistent with loss of ERα function and development of endocrine resistance. Gene expression data suggest that ERα signaling becomes inactivated throughout the progression of endometriosis to EAOC. The gene expression pattern in EAOC is more consistent with profiles of endocrine resistance.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12672-018-0350-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Endometriosis, Estrogen receptor alpha, Human, Estrogens, Ovarian neoplasms, Transcriptome

Introduction

Endometriosis is a common condition, affecting 6–10% of all women of reproductive age and up to 50% of women with infertility [1, 2]. While endometriosis is regarded largely as a benign condition, endometriotic lesions can undergo transformation to specific subtypes of invasive ovarian cancer [3]. A pooled analysis of case-control studies revealed odds ratios of 3.05, 2.11, and 2.04 for the development of clear cell (CCC), endometrioid (ENOC), and low-grade serous (LGS) ovarian cancers for patients with a self-reported history of endometriosis compared to those without [4]. Further, approximately 60–80% of CCC and ENOC present in the setting of atypical endometriosis. As such, these subtypes are often referred to as endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer (EAOC). However, the mechanisms underlying the progression from endometriosis to EAOC are poorly understood.

Identifying biomarkers and pathways associated with the transition from endometriosis to cancer is an active area of research. We have recently identified differences in plasma microRNA profiles between healthy patients, those with endometriosis, and those with EAOC [5, 6]. We also identified immunologic signaling, particularly the complement cascade, as a potential factor in the transformation from endometriosis to EAOC [7]. One pathway that has been understudied to date, however, is the estrogen signaling pathway.

Estrogen is a known driver of endometriosis, contributing to both proliferation of the disease and inflammation [1, 2, 8, 9]. Hormonal therapy (e.g., estrogen-progestin contraceptives or GnRH agonists) is typically prescribed to regulate proliferation of endometriotic implants [2]. Estrogen has also been implicated in ovarian cancer progression; estrogen exposure (e.g., through post-menopausal hormone replacement therapy [HRT]) correlates with risk of ovarian cancer, particularly for ENOC [10, 11]. To this point, a meta-analysis of 27 trials including more than 1.5 million patients found a 20–25% increase in the risk of developing ovarian cancer for ever users of estrogen-containing HRT compared to never users [10]. A second meta-analysis revealed a similar increase in risk and noted a correlation with duration of HRT, the greatest risk associated with over 10 years of use [11]. Interestingly, estrogen-progestin contraceptive use has been shown to decrease risk of ovarian cancers including EAOC and this is likely related to the suppression of ovulation that occurs with use of oral contraceptives [12, 13]. Taken together, these clinical observations suggest that estrogen is involved in the pathogenesis of ovarian cancers and EAOC in particular.

Here, we investigate estrogen signaling during the progression of endometriosis into EAOC using a cohort of tissue samples from healthy controls, patients with both benign and atypical endometriosis, and patients with EAOCs. Using a comprehensive gene signature of estrogen response (the “E2sig”), we identified gene expression changes associated with each disease state. Understanding changes in estrogen signaling during disease progression will help determine the role of ER in transformation from endometriosis to EAOC.

Materials and Methods

Patients

We obtained tissue samples from patients at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center undergoing pelvic surgery for indications including fibroids, pelvic pain, endometriosis, pelvic mass, and confirmed or suspected ovarian malignancy. Tissues were included if they provided adequate samples of benign endometriosis, atypical endometriosis, endometriosis within the vicinity of an EAOC collected at the time of primary surgery (referred to herein as “concurrent endometriosis”), or endometriosis-associated cancers as determined by a pathologist (E.E.). Endometriosis-associated cancers were defined as any epithelial ovarian cancer with concurrent endometriosis identified within the pathologic specimen following surgical resection. We also identified samples of normal endometrium from patients without a diagnosis of endometriosis or cancer, to use as controls. The sample cohort utilized here is part of the sample collection previously described [7]. All samples underwent an independent pathology review by a staff pathologist prior to inclusion in the study. Endometrial phase in the normal endometrium samples was assessed by pathological evaluation. Corresponding patient demographic characteristics, clinical disease characteristics, and treatment factors were abstracted from patient charts. All work was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Pittsburgh.

RNA Extraction and Nanostring Analysis

RNA was isolated from FFPE sections using the RNeasy FFPE Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Expression of 236 genes associated with estrogen signaling (referred to as the E2sig) [14] was measured using a custom code set for the NanoString nCounter platform. RNA (100 ng) was processed for NanoString analysis as previously described [15]. Data were normalized to internal positive controls and to the geometric mean of five housekeeping genes. Additional details of the analysis are provided below under “statistical analysis.”

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for ERα (SP-1 clone, Verotech) was performed by the Department of Pathology at Magee-Womens Hospital of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Stained slides were then reviewed and H-scored by a staff pathologist (E.E.).

Statistical Analysis

Gene expression for each sample was normalized to the mean expression of that gene in the normal endometrium. Hierarchical clustering was used to obtain gene clusters. To refine these clusters to genes with significantly different expressions across the four tissue types, we performed ANOVA with a cutoff of q < 0.05. The 158 genes identified by ANOVA were used for the remaining statistical analysis.

Expression of the 158 differentially expressed genes was compared to pre-clinical profiles of hormone receptor signaling using publicly available data from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). For ERα signaling, we used the following studies: GSE50695, GSE3529, GSE22600, and GSE38234. For ERβ signaling, we used GSE1153 and GSE42347; for PR, GSE46715. Heat maps were generated showing log2(fold change) for hormone treatment vs. vehicle for each study and expression patterns were compared to log2(fold change) of diseased tissue vs. normal endometrium.

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

To evaluate signatures similar to the E2sig, all 236 genes were overlapped against gene sets in the C2 (curated gene set) collection of the molecular signatures database (MsigDB) using the online portal (http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp). To identify gene signatures activated in EAOC, upregulated and downregulated in EAOC relative to normal endometrium were compared to a cancer-specific subset of gene sets in MsigDB C2 by pre-ranked analysis using the Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) desktop application. Upregulated genes comprised those in clusters 1 and 2; downregulated genes were those in clusters 3, 4, and 5.

Availability of Data and Materials

Raw Nanostring data generated in this study are available in the Supplementary Information section of this manuscript. The Gene Expression Omnibus can be accessed at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo. The molecular signature database (MsigDB) can be accessed at http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp.

Results

We collected 83 samples from patients with benign endometriosis (n = 19), which includes both ovarian (n = 11) and non-ovarian endometriosis (n = 8); atypical endometriosis (n = 11); concurrent endometriosis (n = 9); and EAOCs (n = 21). We also obtained 23 samples of normal endometrium with an equal distribution between the proliferative and secretory phases. The sociodemographic and disease characteristics of this patient cohort are summarized in Table 1. Not surprisingly, the patients with concurrent endometriosis and EAOC were older than those with benign and atypical endometriosis (median age of 70 and 57.5 versus 39 and 47 years old, respectively). The majority of patients with EAOC presented at an early stage (15 patients, 71%) and had tumors of endometrioid and clear cell histologies (14, 66% and 5, 34%, respectively). Most of the endometriosis patients were pre-menopausal, while most of the patients with EAOC were post-menopausal at the time of surgery.

Table 1.

Demographic and disease characteristics. Clinical characteristics and disease characteristics of those patients included in the study

| Benign endometriosis (n = 19) | Atypical endometriosis (n = 11) | Concurrent endometriosis (n = 9) | Endometriosis-associated cancer (n = 21) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (y), range | 39 (25–74) | 47 (34–50) | 70 (49–75) | 57.5 (47–77) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.6 | 30.6 | 27.4 | 29.6 |

| Menopausal status | ||||

| Pre-menopausal | 10 | 7 | 2 | 2 |

| Post-menopausal | 1 | 1 | 3 | 11 |

| Unknown | 8 | 3 | 3 | 8 |

| Cancer stage | ||||

| Early (I–II) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 15 (71%) |

| Late (III–IV) | 6 (29%) | |||

| Tumor histology | ||||

| Clear cell | N/A | N/A | N/A | 5 (24%) |

| Endometrioid | 14 (66%) | |||

| Serous | 1 (5%) | |||

| Adenocarcinoma NOS | 1 (5%) | |||

To profile estrogen signaling in patient samples, we analyzed expression of the E2sig [14]. The E2sig is a panel of 236 genes associated with endocrine response. The majority (n = 207) were identified by meta-analysis of estrogen-regulated genes across breast, ovarian, endometrial, and bone cancer [14]. The remaining genes (n = 29) were E2 targets more specific to ovarian cancer, components of the estrogen signaling pathway (e.g., NCOA1, GATA3, FOXA1), and genes associated with clinical response to endocrine therapy [16–18].

Given the discrepancy in age between endometriosis and cancer patients, we first evaluated if expression of the E2sig changed based on menopausal status. To do this, we compared expression of the entire gene set across samples from normal endometrium. Pre-menopausal and post-menopausal patients (extrapolated as those younger or older than 50, respectively) did not cluster separately (Supplementary Fig. 1). Further, a t test comparison identified no genes significantly different between these two groups. Thus, any changes observed in expression are likely due to differences in tissue biology rather than hormonal status of the patient.

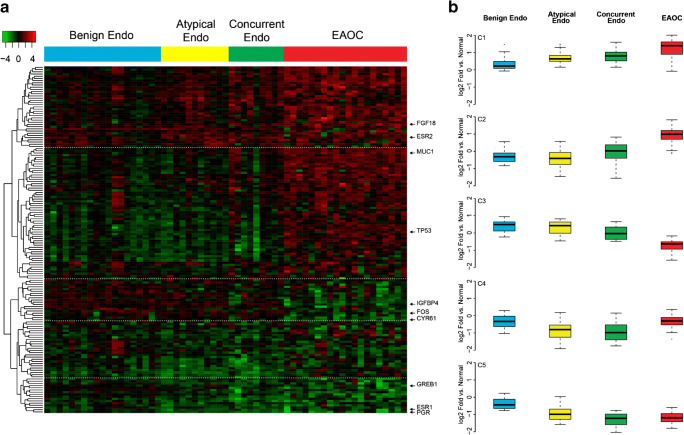

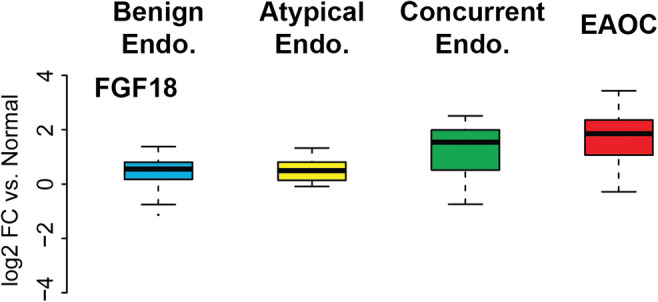

We next evaluated how estrogen signaling changes during the progression from benign endometriosis to EAOC. ANOVA identified 158 genes with significantly different (q < 0.05) expressions between different disease states and these genes separated into five distinct clusters (C1–5, Fig. 1a). Broadly, these clusters represent genes with increased expression through disease progression (C1, C2), decreased expression through progression (C3, C5), or reactivated expression in EAOC (C4). Expression of genes in cluster 1 (C1, n = 37) increased during progression from normal endometrium to endometriosis to EAOC (e.g., FGF18, ESR2; Fig. 1b), while cluster 2 genes (C2, n = 60) were highly expressed specifically in the EAOC specimens (e.g., MUC1, PAX8, TP53, NRIP1). Conversely, cluster 3 (C3, n = 20) genes are lowest expressed in EAOC (e.g., IGFBP4, FOS), and cluster 5 genes (C4, n = 41) are expressed at lower levels in both endometriosis and EAOC than in normal endometrium (e.g., GREB1, ESR1, PGR). Genes in cluster 4 showed decreased expression in concurrent and atypical endometriosis versus benign endometriosis, but were reactivated following progression to EAOC. The full list of genes in each cluster is provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Fig. 1.

Gene expression across disease categories. a Gene expression analysis using the E2Sig identified 158 genes by ANOVA which had statistically significant changes (q < 0.05) in expression between different disease states. Unsupervised clustering reveals five distinct gene clusters. Heat map is colored by log2(fold change) vs normal endometrium. b Boxplots showing the average expression of each gene cluster across disease types (log2(fold change) vs normal endometrium))

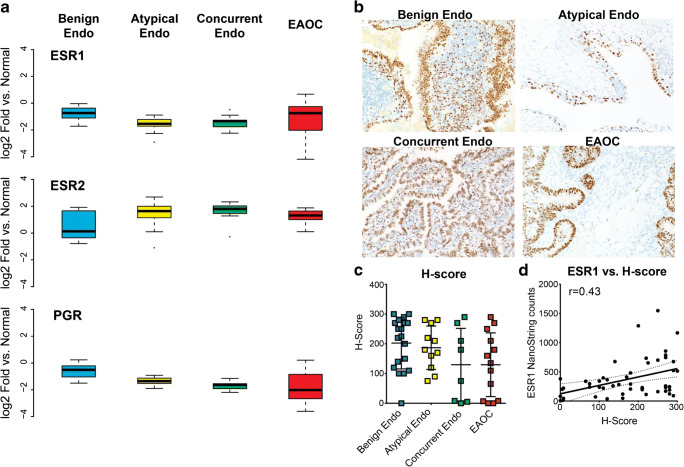

ANOVA analyses identified significant changes in expression of the hormone receptors ERα (ESR1), ERβ (ESR2), and progesterone receptor (PGR). Expression of ESR2 increases incrementally from benign endometriosis to EAOC (Fig. 2a). Conversely, PGR expression decreases from endometriosis to EAOC. ESR1 expression is decreased in benign and atypical endometriosis versus normal endometrium (Fig. 2a) but increases in a subset of EAOC, and this prompted us to investigate ERα expression by immunohistochemistry (IHC). Our results also showed a trend in decreasing ERα protein from benign endometriosis to EAOC (Fig. 2b); median H-score decreased from normal endometrium to benign endometriosis to EAOC (Fig. 2c). H-score had a modest but significant (r = 0.43, p = 0.016) correlation with ESR1 levels (Fig. 2d). Consistent with decreasing ERα, PGR expression also decreases from normal endometriosis to EAOC. Conversely, expression of ESR2 (ERβ) increases incrementally from normal endometriosis to EAOC (Fig. 2a). These changes in hormone receptor levels together with changing hormone-related gene expression profiles suggest an overall change in hormone signaling during the progression from endometriosis to EAOC.

Fig. 2.

Hormone receptor expression within disease categories. a mRNA expression of ESR1 (ERα), ESR2 (ERβ), and PGR (PR). Box plots show log2(fold change) vs normal endometrium. b ERα immunohistochemistry. c ERα H-scores across disease types. d Correlation of ERα mRNA and H-score

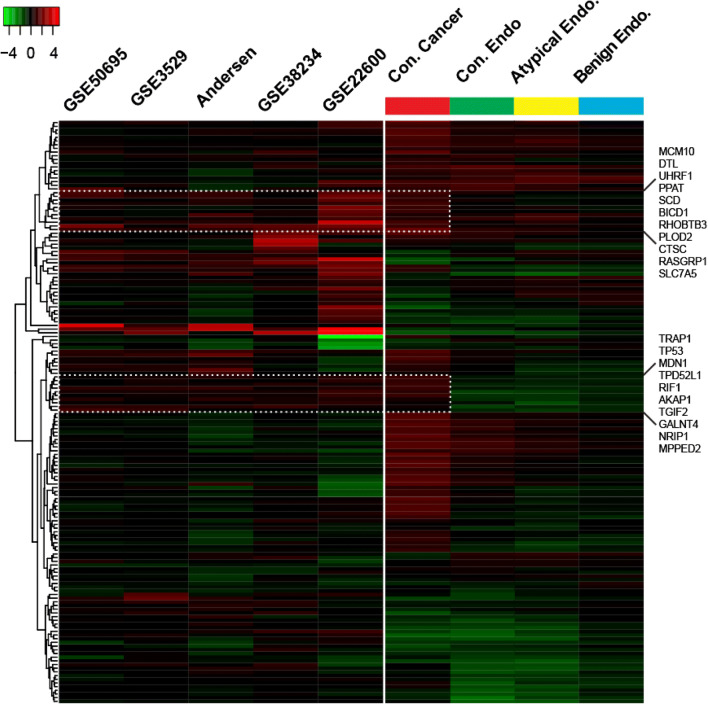

We next asked if gene expression patterns in EAOC represented active ERα signaling in cancer. To do this, we compared the expression of the 158 differentially expressed (DE) genes (Fig. 1) to four pre-clinical gene expression studies conducted after estrogen treatment in breast, ovarian, and endometrial cancer cell lines [17, 19–21], along with data using MCF7 breast cancer cells from our lab. This comparison revealed that some of the genes upregulated in EAOC are consistent with estrogen-induced ERα-mediated transcription (Fig. 3, dashed boxes), e.g., high expression of NRIP1. However, much of the canonical gene regulation is deactivated, consistent with the decrease of GREB1, IGFBP4, and PGR. The same analysis was performed comparing our cohort to profiles of ERβ and PGR signaling [22–24], but no similarities were found between our data and these signatures (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Gene expression of profiles of disease types compared to E2-regulated gene expression in breast, ovarian, and endometrial cell lines. Gene expression of the samples included in our study was compared to studies of gene expression following estrogen treatment in ERα-positive breast cancer cell lines (GSE50695, GSE3529), ovarian cancer cell lines (GSE22600), and endometrial cancer cell lines (GSE28234) found in GEO as well as one in-house study. Cell line studies are colored by fold change of estrogen treatment vs. vehicle control. Patient samples are colored as fold change vs. normal endometrium. The upper and lower panels in the figure below correspond to the highlighted gene lists to the right side of the figure.

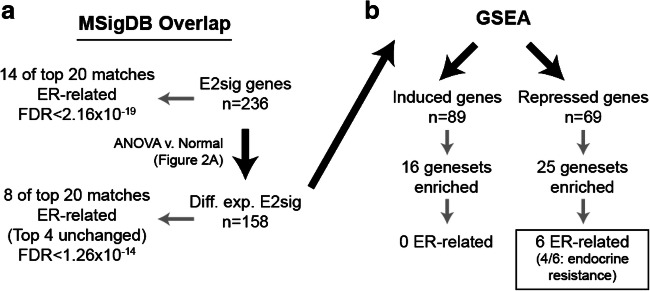

Since the pre-clinical studies used here as a reference represent activated ERα, we performed GSEA against the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) to evaluate ERα signaling in a more unbiased manner. Comparing the complete E2sig gene list to MSigDB identified extensive overlap with ERα signaling signatures (Fig. 4), consistent with the gene set design. Despite this initial enrichment, however, GSEA did not identify any activated ERα-related signatures among over-expressed genes in EAOC (C1, C2). Conversely, among under-expressed genes in EAOC (C3, C5), GSEA identified signatures related to endocrine resistance and loss of ERα function, wherein these genes were similarly under-expressed. These observations suggest that, consistent with decreased ERα expression, EAOC largely inactivate canonical ERα signaling, and may actively transition to an ERα-independent phenotype.

Fig. 4.

Workflow for GSEA analysis. The E2sig was run through MsigDB to confirm enrichment of ER-regulated genes (a). Subsequently, GSEA was performed on the 158 significantly DE genes from the ANOVA to look for gene signatures in an unbiased manner (b)

Given this shift in ERα signaling, genes most highly expressed in EAOC (C1 and C2, Fig. 1a) likely represent de-repressed ERα targets. To this point, IGFBP3, which is a known ERα-repressed target in ovarian cancer [16], has higher gene expression in EAOC and can be found in cluster 2. De-repression of some of these genes may impact tumorigenesis; for example, FGF18 overexpression (cluster 1, Fig. 1a) has recently been identified as a poor prognostic marker in HGS ovarian cancer [25]. FGF18 also modulates migration and invasion of ovarian cancer cells [25]. In our cohort, FGF18 mRNA expression rose with increasing malignancy of disease state (Fig. 5). Given its demonstrated role in HGSOC and elevated expression in EAOC, de-repression of FGF18 may promote EAOC progression.

Fig. 5.

Changes in FGF18 expression across disease types. FGF18 mRNA in different tissue types. Boxplots show log2(fold change) vs normal endometrium

Discussion

Endometriosis and ovarian cancer are both estrogen-responsive disease entities. Given this shared pathway, we investigated how ERα signaling evolves during progression from endometriosis to EAOC by profiling a comprehensive signature of estrogen-regulated genes in patient tissue. Surprisingly, our results indicate that canonical ERα signaling is largely inactivated during the progression from endometriosis to EAOC; rather, gene expression in EAOC mirrors profiles of estrogen resistance.

The overall loss of canonical ERα signaling and gain of hormone resistance in the transition from endometriosis to EAOC has not previously been reported. However, this notion is supported by several studies of the complex interplay between hormone receptors in endometriosis. ERα and PR levels have been shown to be significantly lower in endometriosis compared to normal endometrium while ERβ was elevated [26]. ERβ is generally thought to be anti-proliferative and to antagonize pro-proliferative effects of ERα; however, this may be dependent on tissue context. To this point, ERβ was reported to regulate ERα expression and E2-induced cell cycle progression in endometriosis-derived stromal cells [27]. This suggests that estrogen regulates proliferation in endometriosis through activation of ERβ rather than ERα. Further supporting this is a report that increased ERβ activity led to decreased apoptosis and increased proliferation in a murine model of endometriosis [28]. A shift from ERα to ERβ signaling could be a factor in transformation from endometriosis to EAOC. This would be consistent with our finding that canonical ERα signaling is largely deactivated in EAOC.

Inactivation of canonical ERα signaling is reflected by the decrease in genes such as GREB1, IGFBP4, and PGR. Loss of these genes could carry significant consequences for proliferation of these tissues, particularly PGR. Progesterone signaling via PGR abrogates estrogen-induced proliferation of normal endometrium. In addition, progestins have been suggested to have an anti-inflammatory role in the endometrium. PGR downregulation in EAOC, combined with a recent report that inflammation affects progression from endometriosis to EAOC [7], suggests there may be overlap between the hormonal regulation and inflammatory regulation of disease progression. Indeed, inflammatory cytokines have been reported to regulate expression of nuclear receptors including PGR in endometrial stromal cells [29]. Further, targeting either ERα or β isoform with inhibitors that also decreased inflammation was shown to block progression of endometriosis in a mouse model [30]. Moreover, recent work implicates crosstalk between IL-6 and E2 in progression of endometriosis [31]. The interplay between hormone signaling and inflammation in transformation of endometriosis to EAOC should be a focus of future study.

While components of canonical ERα signaling were deactivated in EAOC, there was a subset of ERα-induced genes that remained highly expressed in EAOC (e.g., NRIP1) (Fig. 3). NRIP1, which encodes RIP140, is a nuclear receptor co-regulator. RIP140 has been previously shown to interact with both ERβ and ERα in ovarian cancer cell lines to promote proliferation [32]. This observation suggests that activation of these genes despite downregulation of ERα could potentially promote transformation to EAOC.

Another possibility based on the shift in ER signaling is that de-repression of ERα target genes promotes EAOC growth and the development of endocrine resistance. Supporting this notion is the increased expression of FGF18 in EAOC (Figs. 1 and 5). FGF18 has previously been described as a driver of tumorigenesis and poor prognostic marker in high-grade serous ovarian cancers [25]. Our results further suggest a role for FGF18 as a driver of ovarian tumorigenesis in EAOC. Potential interplay between the ERs and FGF18 in the development of EAOCs has not been described in the literature. However, broader FGFR signaling has been implicated in endocrine resistance in breast cancer [19, 33–36]. Future investigations should focus on understanding the crosstalk between FGF18 and the ERs and on the potential of FGF18 as both a biomarker and therapeutic target.

A limitation of our analyses is that the small cohort of EAOCs (n = 21) did not provide enough power to compare clear cell carcinomas to endometrioid tumors. Previous reports have indicated that only 6% of clear cell tumors express ERα and PR, whereas the majority (63%) of endometrioid tumors express both receptors [37, 38]. Further, endometrioid tumors are reported to have higher expression of ERβ than clear cell tumors [39]. One could postulate that these two histologic subtypes, despite both being classified as EAOC, may diverge in their hormone response. However, larger cohorts will be necessary to compare differences in ERα signaling between the two groups and between EAOC and high-grade serous ovarian cancer, the most frequent, yet non-endometriosis-related histotype. Additionally, while our tissue samples were reviewed to meet an epithelial purity cutoff, we used macrodissection rather than microdissection, leading to the inclusion of some stromal components. As endometrial stroma may also be estrogen-responsive, future studies should analyze epithelial and stromal tissue separately to evaluate ER signaling in each compartment. Additionally, the cohort included in this study has a mean body mass index (BMI) of 30 and represents an obese population of patients. Obesity is associated with increased estrogen exposure and the patients in this study may have had higher systemic estrogen levels than patients with a normal BMI.

In summary, expression profiles of primary tissue samples suggest ERα expression and classical signaling decreases during the progression of endometriosis to EAOC. Several ERα-induced genes remain highly expressed in EAOC (e.g., NRIP1) and may contribute to estrogen-dependent EAOC progression. Similarly, de-repression of ERα target genes such as FGF18 may facilitate the transformation of endometriosis into EAOC.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Raw Nanostring Data. (XLSX 130 kb)

E2-Regulated genes grouped by cluster. Genes within each cluster as identified by ANOVA. (PPTX 128 kb)

Comparison of the E2sig between pre- and post-menopausal patients. Heat map showing expression if E2sig in normal tumors. (PPTX 255 kb)

Funding

This study was supported by the UPMC Research Fund (to R. Edwards and A.M. Vlad). C. L. Andersen was supported by F31CA186376, T32GM008424, and the ARCS Foundation. M.J. Sikora was supported by K99CA193734.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Courtney L. Andersen and Michelle M. Boisen contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Eskenazi B, Warner ML. Epidemiology of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am. 1997;24:235–258. doi: 10.1016/S0889-8545(05)70302-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giudice LC. Clinical practice. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2389–2398. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1000274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Gorp T, Amant F, Neven P, Vergote I, Moerman P. Endometriosis and the development of malignant tumours of the pelvis. A review of literature. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;18:349–371. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2003.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pearce CL, Templeman C, Rossing MA, Lee A, Near AM, Webb PM, Nagle CM, Doherty JA, Cushing-Haugen KL, Wicklund KG, Chang-Claude J, Hein R, Lurie G, Wilkens LR, Carney ME, Goodman MT, Moysich K, Kjaer SK, Hogdall E, Jensen A, Goode EL, Fridley BL, Larson MC, Schildkraut JM, Palmieri RT, Cramer DW, Terry KL, Vitonis AF, Titus LJ, Ziogas A, Brewster W, Anton-Culver H, Gentry-Maharaj A, Ramus SJ, Anderson AR, Brueggmann D, Fasching PA, Gayther SA, Huntsman DG, Menon U, Ness RB, Pike MC, Risch H, Wu AH, Berchuck A, Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium Association between endometriosis and risk of histological subtypes of ovarian cancer: a pooled analysis of case-control studies. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:385–394. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70404-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suryawanshi S, Vlad AM, Lin HM, Mantia-Smaldone G, Laskey R, Lee M, Lin Y, Donnellan N, Klein-Patel M, Lee T, Mansuria S, Elishaev E, Budiu R, Edwards RP, Huang X. Plasma microRNAs as novel biomarkers for endometriosis and endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:1213–1224. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dong M, Yang P, Hua F. MiR-191 modulates malignant transformation of endometriosis through regulating TIMP3. Med Sci Monit. 2015;21:915–920. doi: 10.12659/MSM.893872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suryawanshi S, Huang X, Elishaev E, Budiu RA, Zhang L, Kim S, Donnellan N, Mantia-Smaldone G, Ma T, Tseng G, Lee T, Mansuria S, Edwards RP, Vlad AM. Complement pathway is frequently altered in endometriosis and endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:6163–6174. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan KN, Kitajima M, Inoue T, Fujishita A, Nakashima M, Masuzaki H. 17beta-estradiol and lipopolysaccharide additively promote pelvic inflammation and growth of endometriosis. Reprod Sci. 2015;22:585–594. doi: 10.1177/1933719114556487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naqvi H, Sakr S, Presti T, Krikun G, Komm B, Taylor HS. Treatment with bazedoxifene and conjugated estrogens results in regression of endometriosis in a murine model. Biol Reprod. 2014;90:121. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.113.114165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou B, Sun Q, Cong R, Gu H, Tang N, Yang L, Wang B. Hormone replacement therapy and ovarian cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;108:641–651. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garg PP, Kerlikowske K, Subak L, Grady D. Hormone replacement therapy and the risk of epithelial ovarian carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:472–479. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collaborative Group on Epidemiological Studies of Ovarian C. Beral V, Doll R, Hermon C, Peto R, Reeves G. Ovarian cancer and oral contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of data from 45 epidemiological studies including 23,257 women with ovarian cancer and 87,303 controls. Lancet. 2008;371:303–314. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60167-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grandi G, Toss A, Cortesi L, Botticelli L, Volpe A, Cagnacci A. The association between endometriomas and ovarian cancer: preventive effect of inhibiting ovulation and menstruation during reproductive life. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:751571. doi: 10.1155/2015/751571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andersen CL, Sikora MJ, Boisen MM, Ma T, Christie A, Tseng G, Park Y, Luthra S, Chandran U, Haluska P, Mantia-Smaldone GM, Odunsi K, McLean K, Lee AV, Elishaev E, Edwards RP, Oesterreich S. Active estrogen receptor-alpha signaling in ovarian cancer models and clinical specimens. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:3802–3812. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nayak SR, Harrington E, Boone D, Hartmaier R, Chen J, Pathiraja TN, Cooper KL, Fine JL, Sanfilippo J, Davidson NE, Lee AV, Dabbs D, Oesterreich S. A role for histone H2B variants in endocrine-resistant breast cancer. Horm Cancer. 2015;6:214–224. doi: 10.1007/s12672-015-0230-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walker G, MacLeod K, Williams AR, Cameron DA, Smyth JF, Langdon SP. Insulin-like growth factor binding proteins IGFBP3, IGFBP4, and IGFBP5 predict endocrine responsiveness in patients with ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1438–1444. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spillman MA, Manning NG, Dye WW, Sartorius CA, Post MD, Harrell JC, Jacobsen BM, Horwitz KB. Tissue-specific pathways for estrogen regulation of ovarian cancer growth and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8927–8936. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Argenta PA, Um I, Kay C, Harrison D, Faratian D, Sueblinvong T, Geller MA, Langdon SP. Predicting response to the anti-estrogen fulvestrant in recurrent ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;131:368–373. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.07.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sikora MJ, Cooper KL, Bahreini A, Luthra S, Wang G, Chandran UR, Davidson NE, Dabbs DJ, Welm AL, Oesterreich S. Invasive lobular carcinoma cell lines are characterized by unique estrogen-mediated gene expression patterns and altered tamoxifen response. Cancer Res. 2014;74:1463–1474. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rae JM, Johnson MD, Scheys JO, Cordero KE, Larios JM, Lippman ME. GREB 1 is a critical regulator of hormone dependent breast cancer growth. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;92:141–149. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-1483-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gertz J, Reddy TE, Varley KE, Garabedian MJ, Myers RM. Genistein and bisphenol A exposure cause estrogen receptor 1 to bind thousands of sites in a cell type-specific manner. Genome Res. 2012;22:2153–2162. doi: 10.1101/gr.135681.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stossi F, Barnett DH, Frasor J, Komm B, Lyttle CR, Katzenellenbogen BS. Transcriptional profiling of estrogen-regulated gene expression via estrogen receptor (ER) alpha or ERbeta in human osteosarcoma cells: distinct and common target genes for these receptors. Endocrinology. 2004;145:3473–3486. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Madak-Erdogan Z, Charn TH, Jiang Y, Liu ET, Katzenellenbogen JA, Katzenellenbogen BS. Integrative genomics of gene and metabolic regulation by estrogen receptors alpha and beta, and their coregulators. Mol Syst Biol. 2013;9:676. doi: 10.1038/msb.2013.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dressing GE, Knutson TP, Schiewer MJ, Daniel AR, Hagan CR, Diep CH, Knudsen KE, Lange CA. Progesterone receptor-cyclin D1 complexes induce cell cycle-dependent transcriptional programs in breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2014;28:442–457. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wei W, Mok SC, Oliva E, Kim SH, Mohapatra G, Birrer MJ. FGF18 as a prognostic and therapeutic biomarker in ovarian cancer. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:4435–4448. doi: 10.1172/JCI70625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bulun SE, Monsavais D, Pavone ME, Dyson M, Xue Q, Attar E, Tokunaga H, Su EJ. Role of estrogen receptor-beta in endometriosis. Semin Reprod Med. 2012;30:39–45. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1299596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trukhacheva E, Lin Z, Reierstad S, Cheng YH, Milad M, Bulun SE. Estrogen receptor (ER) beta regulates ERalpha expression in stromal cells derived from ovarian endometriosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:615–622. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han SJ, Jung SY, Wu SP, Hawkins SM, Park MJ, Kyo S, Qin J, Lydon JP, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, DeMayo FJ, O’Malley BW. Estrogen receptor beta modulates apoptosis complexes and the inflammasome to drive the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Cell. 2015;163:960–974. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grandi G, Mueller MD, Papadia A, Kocbek V, Bersinger NA, Petraglia F, Cagnacci A, McKinnon B. Inflammation influences steroid hormone receptors targeted by progestins in endometrial stromal cells from women with endometriosis. J Reprod Immunol. 2016;117:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao Y, Gong P, Chen Y, Nwachukwu JC, Srinivasan S, Ko C, Bagchi MK, Taylor RN, Korach KS, Nettles KW, Katzenellenbogen JA, Katzenellenbogen BS. Dual suppression of estrogenic and inflammatory activities for targeting of endometriosis. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:271ra9. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3010626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burns KA, Thomas SY, Hamilton KJ, Young SL, Cook DN, Korach KS. Early endometriosis in females is directed by immune-mediated estrogen receptor alpha and IL-6 cross-talk. Endocrinology. 2018;159:103–118. doi: 10.1210/en.2017-00562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Docquier A, Garcia A, Savatier J, Boulahtouf A, Bonnet S, Bellet V, Busson M, Margeat E, Jalaguier S, Royer C, Balaguer P, Cavaillès V. Negative regulation of estrogen signaling by ERbeta and RIP140 in ovarian cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2013;27:1429–1441. doi: 10.1210/me.2012-1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tomlinson DC, Knowles MA, Speirs V. Mechanisms of FGFR3 actions in endocrine resistant breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:2857–2866. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turner N, Pearson A, Sharpe R, Lambros M, Geyer F, Lopez-Garcia MA, Natrajan R, Marchio C, Iorns E, Mackay A, Gillett C, Grigoriadis A, Tutt A, Reis-Filho JS, Ashworth A. FGFR1 amplification drives endocrine therapy resistance and is a therapeutic target in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:2085–2094. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aguilar H, Sole X, Bonifaci N, Serra-Musach J, Islam A, Lopez-Bigas N, et al. Biological reprogramming in acquired resistance to endocrine therapy of breast cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29:6071–6083. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meijer D, Sieuwerts AM, Look MP, van Agthoven T, Foekens JA, Dorssers LC. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 predicts failure on tamoxifen therapy in patients with recurrent breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2008;15:101–111. doi: 10.1677/ERC-07-0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sieh W, Kobel M, Longacre TA, Bowtell DD, deFazio A, Goodman MT, et al. Hormone-receptor expression and ovarian cancer survival: an ovarian tumor tissue analysis consortium study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:853–862. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70253-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Worley MJ, Jr, Liu S, Hua Y, Kwok JS, Samuel A, Hou L, et al. Molecular changes in endometriosis-associated ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:1831–1842. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fujimura M, Hidaka T, Kataoka K, Yamakawa Y, Akada S, Teranishi A, Saito S. Absence of estrogen receptor-alpha expression in human ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma compared with ovarian serous, endometrioid, and mucinous adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:667–672. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200105000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Raw Nanostring Data. (XLSX 130 kb)

E2-Regulated genes grouped by cluster. Genes within each cluster as identified by ANOVA. (PPTX 128 kb)

Comparison of the E2sig between pre- and post-menopausal patients. Heat map showing expression if E2sig in normal tumors. (PPTX 255 kb)

Data Availability Statement

Raw Nanostring data generated in this study are available in the Supplementary Information section of this manuscript. The Gene Expression Omnibus can be accessed at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo. The molecular signature database (MsigDB) can be accessed at http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp.