Visual Abstract

Keywords: acute renal failure, cardiovascular, cardiovascular disease, chronic heart failure, CKD, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, epidemiology and outcomes, heart disease, heart failure

Abstract

Background

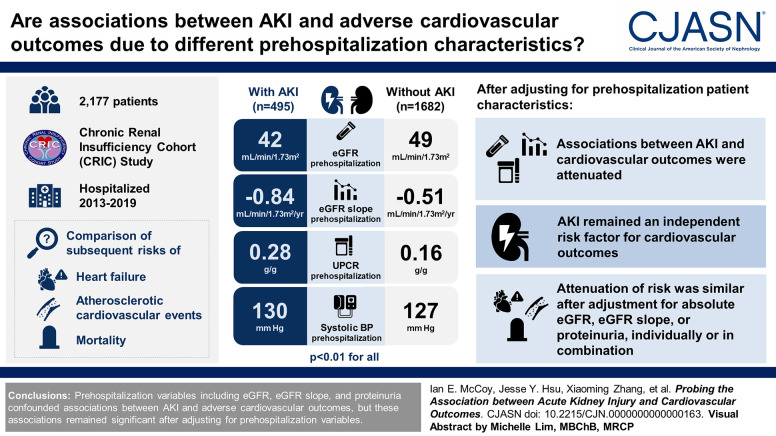

Patients hospitalized with AKI have higher subsequent risks of heart failure, atherosclerotic cardiovascular events, and mortality than their counterparts without AKI, but these higher risks may be due to differences in prehospitalization patient characteristics, including the baseline level of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), the rate of prior eGFR decline, and the proteinuria level, rather than AKI itself.

Methods

Among 2177 adult participants in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort study who were hospitalized in 2013–2019, we compared subsequent risks of heart failure, atherosclerotic cardiovascular events, and mortality between those with serum creatinine–based AKI (495 patients) and those without AKI (1682 patients). We report both crude associations and associations sequentially adjusted for prehospitalization characteristics including eGFR, eGFR slope, and urine protein-creatinine ratio (UPCR).

Results

Compared with patients hospitalized without AKI, those with hospitalized AKI had lower eGFR prehospitalization (42 versus 49 ml/min per 1.73 m2), faster chronic loss of eGFR prehospitalization (−0.84 versus −0.51 ml/min per 1.73 m2 per year), and more proteinuria prehospitalization (UPCR 0.28 versus 0.16 g/g); they also had higher prehospitalization systolic BP (130 versus 127 mm Hg; P < 0.01 for all comparisons). Adjustment for prehospitalization patient characteristics attenuated associations between AKI and all three outcomes, but AKI remained an independent risk factor. Attenuation of risk was similar after adjustment for absolute eGFR, eGFR slope, or proteinuria, individually or in combination.

Conclusions

Prehospitalization variables including eGFR, eGFR slope, and proteinuria confounded associations between AKI and adverse cardiovascular outcomes, but these associations remained significant after adjusting for prehospitalization variables.

Introduction

A number of epidemiologic studies have linked hospitalized AKI (hitherto referred to as AKI) to higher subsequent risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality.1–5 Kidney failure and CKD are established risk factors for cardiovascular events,6–9 so it seems possible that AKI—a condition also associated with impaired kidney function and similar metabolic disturbances10–12—may likewise result in a heightened risk of future cardiovascular events. Animal models of AKI have demonstrated cardiac alterations and endothelial dysfunction as distant effects of AKI.13,14 In humans, AKI has been associated with increases in selected inflammatory cytokines,15–17 which may increase the risk of subsequent cardiovascular disease analogous to other acute illnesses characterized by inflammation (e.g., serious infections).18,19

However, the associations between AKI and cardiovascular disease and death seen in epidemiologic studies may be due to confounding by differences in patient characteristics between patients with and without AKI. These differences may be observable prehospitalization, including proteinuria level, eGFR level, and slope of eGFR change before hospital admission. We hypothesize that confounding is possible because (1) higher proteinuria, lower eGFR, and more rapid eGFR loss are risk factors for both AKI20,21 and cardiovascular events and death,22–25 and (2) a recent analysis of the ASsessment, SErial evaluation, and Subsequent Sequelae of AKI (ASSESS-AKI) study5 found that after adjusting for post-AKI eGFR and proteinuria, the associations of AKI with heart failure and death were attenuated and no longer statistically significant,5 and much of the proteinuria observed post-AKI may already be present pre-AKI. However, that study did not include information on pre-AKI proteinuria and eGFR slope.

Clarifying whether and to what extent these variables may confound associations between AKI and cardiovascular outcomes is important to address a long-standing question that remains incompletely answered: Does AKI cause poor outcomes or is AKI just a marker of higher risk for poor outcomes? To fill this gap in the AKI epidemiology literature, we conducted the current analysis of the prospective Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC), which systematically measured proteinuria and eGFR both before and after hospitalization.

Methods

Study Population

We studied adults with CKD using the CRIC study, a multicenter prospective observational cohort study.26 The CRIC study included annual in-person visits where samples of blood and urine were taken and midyear telephone contacts to update medical history. Hospitalizations were ascertained during annual study site visits and midyear telephone calls to participants or their proxies, in addition to active surveillance by study personnel.27,28 After July 1, 2013, serum creatinine measurements during hospitalizations were systematically extracted. The CRIC Study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of all participating centers and is in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent.

Exposure

Adapting the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes definition, we defined AKI as peak inpatient serum creatinine values ≥1.5 times the inpatient nadir or an increase in serum creatinine by ≥0.3 mg/dl during any 48 hour period during the hospitalization.29,30 AKI cases were classified using the peak:nadir serum creatinine ratios as stage 3=≥3.00 or receipt of KRT, stage 2=2.00–2.99, and stage 1=all others. To achieve greater separation, we defined non-AKI hospitalizations as those meeting all of the following conditions: (1) inpatient peak:nadir serum creatinine ratio <1.2, (2) inpatient peak minus nadir serum creatinine <0.3 mg/dl, and (3) peak inpatient/most recent outpatient study visit serum creatinine <1.5. Hospitalizations meeting neither AKI nor non-AKI criteria were not included in the main analysis.

Cohort Assembly

We selected CRIC participants who were hospitalized between January 7, 2013, and December 12, 2019, because systematic capture of inpatient serum creatinine readings to define presence or absence of AKI began after a CRIC protocol change starting on January 7, 2013. For participants who had multiple hospitalizations (68%), we selected the first hospitalization. Two thousand three hundred and sixty-two CRIC participants who were hospitalized before development of kidney failure (defined as receipt of kidney transplant or maintenance dialysis) and survived at least until hospital discharge were initially selected (Supplemental Figure 1). One hundred and eighty-five participants were excluded whose hospitalizations met criteria for neither AKI nor non-AKI. The final study cohort size for the main analysis was 2177.

Outcomes

Outcomes were as follows: (1) time to first heart failure hospitalization (encompassing definite and probable), (2) time to first atherosclerotic cardiovascular event (encompassing probable or definite myocardial infarction, probable or definite ischemic stroke, or peripheral artery disease), (3) time to death, and (4) a composite outcome of all three (heart failure, atherosclerotic cardiovascular event, or death). Outcomes were ascertained using physician adjudication of medical records or from the Social Security Death Master File for death as previously described.31

Statistical Analysis

The prehospitalization eGFR slope for each patient was estimated using a mixed effects model composed of all prehospitalization eGFR measurements (median of five measurements per patient; eGFR from the CRIC specific equation32), age, sex, race, proteinuria, diabetes, and systolic BP (all time-updated). In patients without an eGFR measurement at the prehospitalization visit (7% of the cohort), the prehospitalization eGFR was extrapolated from previous study visit measurements and eGFR slope. For other missing variables (body mass index [BMI] 22%, proteinuria 13%, systolic BP 6%, <2% for all others), the most recent prior values were used (i.e., last value carried forward). For the 3% (69 of 2177) of participants who did not have a value to carry forward for a particular variable, the corresponding median value was imputed.

Chi-squared tests for categorical variables and t tests and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests (for means and medians, respectively) for continuous variables were used to generate P values for descriptive statistics. To estimate associations between AKI and outcomes, we performed Cox proportional hazards regression for death and cause-specific hazard models for the other outcomes using the date of hospital discharge as time zero. Patients were followed until the first outcome event, death, withdrawal, or May 2020, whichever came first. Starting from a simple model adjusting only for CRIC study site, we next adjusted for demographics (age, sex, race/ethnicity), cardioprotective medication use (including statins, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers [ACEi/ARBs], mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 [SGLT2] inhibitors, β-blockers, antiplatelet agents), hospitalization type (by International Classification of Diseases-9/10 code28,33), and established cardiovascular risk factors (prehospitalization BMI, systolic BP, histories of diabetes mellitus, myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke, peripheral arterial disease, dyslipidemia, smoking status, and family history of coronary disease). We then sequentially adjusted for key prehospitalization variables including absolute eGFR, eGFR slope, and proteinuria. We additionally reported AKI-outcome associations stratified by AKI stage.

To investigate whether the results would substantially change with other AKI/non-AKI definitions, we performed two sensitivity analyses. The first sensitivity analysis defined AKI using the prehospitalization study visit creatinine as the baseline rather than the nadir inpatient creatinine. The second sensitivity analysis defined non-AKI as the absence of AKI rather than the more complex criteria for non-AKI in the main analysis.

All analyses were performed using SAS/STAT software (version 9.4 of the SAS System for Windows, 2016).

Results

Cohort Characteristics

Our final study cohort consisted of 2177 hospitalized patients who did not have kidney failure at the time of admission and who survived until hospital discharge. One thousand six hundred and eighty-two patients met the criteria for non-AKI during their hospitalizations, while 495 patients had AKI during their hospitalizations (Table 1). Seventy-nine percent of the AKI hospitalizations were classified as stage 1 AKI (Table 2). Three patients required dialysis. The patients with AKI had higher prevalence of diabetes, peripheral arterial disease, and family history of coronary disease.

Table 1.

Prehospitalization characteristics

| Characteristics Mean (SD) or Median (IQR) |

Patients with AKI Hospitalization (n=495) | Patients with Non-AKI Hospitalization (n=1682) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age, yr | 67 (10) | 67 (9) |

| Female, n (%) | 204 (41) | 784 (47) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Hispanic | 55 (11) | 145 (9) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 228 (46) | 745 (44) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 196 (40) | 758 (45) |

| Other | 16 (3) | 34 (2) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 335 (68) | 921 (55) |

| Dyslipidemia | 440 (89) | 1437 (85) |

| Myocardial infarction | 162 (33) | 488 (29) |

| Stroke | 75 (15) | 229 (14) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 50 (10) | 121 (7) |

| Heart failure | 64 (13) | 208 (12) |

| Cancer | 104 (21) | 340 (20) |

| Family history of coronary artery disease | 54 (11) | 132 (8) |

| Current smoker | 59 (12) | 157 (9) |

| Former smoker | 218 (44) | 743 (44) |

| Never smoker | 218 (44) | 782 (47) |

| Medications, n (%) | ||

| ACEi/ARB use | 339 (69) | 1097 (65) |

| β-blocker use | 313 (63) | 920 (55) |

| Antiplatelet use | 298 (60) | 952 (57) |

| Statin use | 328 (66) | 1127 (67) |

| MRA use | 32 (7) | 129 (8) |

| SGLT2i use | 5 (1) | 6 (0) |

| No. of antihypertensive medication classes, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 23 (5) | 126 (8) |

| 1 | 50 (10) | 277 (17) |

| 2 | 112 (23) | 429 (26) |

| 3 | 132 (27) | 380 (23) |

| 4+ | 178 (36) | 466 (28) |

| Physical examination and laboratory studies | ||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 34 (8) | 33 (8) |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 130 (22) | 127 (20) |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dl | 1.80 (0.92) | 1.52 (0.71) |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 42 (18) | 49 (18) |

| Urine protein-to-creatinine ratio, g/g | 0.28 (0.11–1.33) | 0.16 (0.07–0.50) |

| eGFR slope, ml/min per 1.73 m2 per year | −0.84 (0.97) | −0.51 (0.90) |

IQR, interquartile range; ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; SGLT2i, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor; BMI, body mass index.

Table 2.

Hospitalization characteristics

| Characteristics Mean (SD) or Median (interquartile range) |

Patients with AKI Hospitalization (n=495) | Patients with Non-AKI Hospitalization (n=1682) |

|---|---|---|

| Days between prehospitalization visit and hospital admission | 227 (120–329) | 188 (99–289) |

| Hospitalization length of stay, d | 5 (3–9) | 1 (0–2) |

| AKI stage, n (%) | ||

| Stage 1 | 391 (79) | — |

| Stage 2 | 76 (15) | — |

| Stage 3 | 28 (6) | — |

| Hospitalization type, n (%) | ||

| Cardiovascular | 135 (27) | 411 (24) |

| Infectious | 68 (14) | 91 (5) |

| Other | 292 (59) | 1180 (70) |

Differences in Patient Characteristics Prehospitalization

Prehospitalization eGFR was lower among those with AKI (mean 42 versus 49 ml/min per 1.73 m2 in the non-AKI group; P < 0.001; Table 1). The prehospitalization eGFR slope was significantly steeper (i.e., rate of eGFR loss was more rapid) for the AKI group (−0.84 versus −0.51 ml/min per 1.73 m2 per year in the non-AKI group, P < 0.001). Prehospitalization urine protein-creatinine ratio was higher in the AKI group (0.28 versus 0.16 g/g in the non-AKI group, P < 0.001). Prehospitalization systolic BP was higher in the AKI group (130 versus 127 mm Hg, P = 0.006).

Event Rates

The incidences of heart failure, atherosclerotic cardiovascular events, and death after hospital discharge were 17%, 12%, and 22%, respectively. Mean follow-up from hospital discharge to the event ranged from 3.0 to 3.8 years depending on the outcome (Table 3). The overall crude event rates per 1000 person-years were 52.1, 37.5, and 57.6 for heart failure, atherosclerotic cardiovascular events, and death, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Crude event rates

| Outcome | AKI Status | N | Mean Follow-Up, yr | Events | Event Rate/1000 Person-Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart failure | All | 2177 | 3.2 | 363 | 52.1 |

| Non-AKI | 1682 | 3.4 | 253 | 44.4 | |

| AKI | 495 | 2.6 | 110 | 86.2 | |

| Atherosclerotic cardiovascular event | All | 2177 | 3.3 | 267 | 37.5 |

| Non-AKI | 1682 | 3.5 | 188 | 32.4 | |

| AKI | 495 | 2.7 | 79 | 60.0 | |

| Death | All | 2177 | 3.8 | 479 | 57.6 |

| Non-AKI | 1682 | 4.0 | 313 | 47.1 | |

| AKI | 495 | 3.4 | 166 | 99.6 | |

| Composite of all three outcomes | All | 2177 | 3.0 | 774 | 117.5 |

| Non-AKI | 1682 | 3.2 | 538 | 99.6 | |

| AKI | 495 | 2.4 | 236 | 199.0 |

Association between AKI, Prehospitalization Characteristics, and Outcomes

Lower levels of prehospitalization eGFR, more rapid loss of prehospitalization eGFR (steeper eGFR slope), and higher levels of prehospitalization proteinuria and systolic BP were all associated with higher risks of adverse outcomes (regardless of AKI status, Supplemental Table 1).

Adjusted only for study site, AKI was associated with higher risks of heart failure (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.86; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.48 to 2.33), atherosclerotic cardiovascular events (aHR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.41 to 2.41), death (aHR, 2.12; 95% CI, 1.75 to 2.57), and the composite of all three outcomes (aHR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.66 to 2.26; Table 4; model 1).

Table 4.

Hazard ratios (95% confidence interval) of AKI for four outcomes

| Model | Heart Failure | Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Event | Death | Composite of All Three Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1: crude (adjusted for site only) | 1.86 (1.48 to 2.33) | 1.84 (1.41 to 2.41) | 2.12 (1.75 to 2.57) | 1.93 (1.66 to 2.26) |

| 2: model 1 + nonrenal variablesa | 1.67 (1.32 to 2.10) | 1.75 (1.33 to 2.30) | 2.08 (1.71 to 2.54) | 1.79 (1.53 to 2.10) |

| 3a: model 2 + prehospitalization eGFR | 1.45 (1.15 to 1.84) | 1.62 (1.23 to 2.13) | 1.87 (1.53 to 2.29) | 1.62 (1.38 to 1.91) |

| 3b: model 2 + prehospitalization eGFR slope | 1.51 (1.19 to 1.91) | 1.65 (1.25 to 2.17) | 1.96 (1.60 to 2.39) | 1.68 (1.43 to 1.97) |

| 3c: model 2 + prehospitalization proteinuria | 1.53 (1.21 to 1.94) | 1.68 (1.28 to 2.22) | 1.97 (1.61 to 2.41) | 1.69 (1.44 to 1.99) |

| 4: model 2 + prehospitalization eGFR and eGFR slope | 1.44 (1.14 to 1.83) | 1.61 (1.22 to 2.12) | 1.87 (1.53 to 2.29) | 1.62 (1.38 to 1.90) |

| 5: model 4 + prehospitalization eGFR, eGFR slope, and proteinuria | 1.40 (1.11 to 1.78) | 1.59 (1.20 to 2.10) | 1.84 (1.50 to 2.26) | 1.59 (1.35 to 1.87) |

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular event encompasses myocardial infarction, stroke, and peripheral artery disease.

Sex, race/ethnicity, age, body mass index, systolic BP, use of statin, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blocker, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor, β-blocker, antiplatelet, hospitalization type, and histories of diabetes, myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke, peripheral artery disease, smoking status, dyslipidemia, and family history of coronary disease.

When the model was adjusted for demographics, cardioprotective medication use, and established cardiovascular risk factors (Table 4; model 2), hazard ratios for all outcomes were attenuated but remained statistically significant. Additional adjustment for prehospitalization eGFR, eGFR slope, and proteinuria (Table 4; models 3a–3c) each resulted in further attenuation in the hazards of all outcomes. When added to the model already accounting for prehospitalization eGFR and other confounders (Table 4; model 3a), additional adjustment for prehospitalization eGFR slope (Table 4; model 4) did not attenuate hazard ratios, and additional adjustment for prehospitalization proteinuria (Table 4; model 5) only resulted in slight additional attenuation. In the fully adjusted model including prehospitalization eGFR, eGFR slope, and proteinuria (Table 4; model 5), the attenuated associations between AKI and all outcomes remained significant (aHR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.11 to 1.78 for heart failure; aHR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.20 to 2.10 for atherosclerotic cardiovascular events; aHR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.50 to 2.26 for death).

Examination of risks by AKI stage was limited by relatively few AKI stage 2/3 cases (21%; Table 2). Adjusted hazard ratios stratified by AKI stage are shown in Supplemental Table 2. Stage 1 AKI remained statistically significantly associated with all adverse outcomes.

Sensitivity Analyses

For the first sensitivity analysis, defining AKI using prehospitalization study visit creatinine as the baseline rather than the nadir inpatient creatinine, the new cohort included 2186 patients (584 AKI and 1602 non-AKI). The hazard ratio of AKI for heart failure was higher than in the main analysis (1.79 versus 1.40), while the hazard ratios for the other three outcomes were similar (Supplemental Table 3). For the second sensitivity analysis, defining non-AKI as the absence of AKI rather than the more complex criteria for non-AKI in the main analysis, the new cohort included 2362 patients (414 AKI and 1948 non-AKI). Compared with the main analysis, the hazard ratios for atherosclerotic cardiovascular events, death, and the composite were all attenuated (though still significant), while the hazard for heart failure was similar (1.45 versus 1.40).

Discussion

In this study, we confirmed previous observations1–5 that patients who were hospitalized and experienced AKI had higher risks of heart failure and atherosclerotic cardiovascular events months to years after discharge compared with their counterparts who were hospitalized but did not experience AKI. The novel contribution of this study is to show that those with AKI not only had lower prehospitalization eGFR but they were also having more rapid chronic loss of eGFR prehospitalization and higher levels of proteinuria prehospitalization and that accounting for prehospitalization characteristics attenuated the associations between AKI and subsequent risks of heart failure and atherosclerotic cardiovascular events and to a lesser extent death. However, AKI remained an independent risk factor for cardiovascular events and death after adjusting for prehospitalization eGFR, eGFR slope, and proteinuria in models adjusted for all available prehospitalization parameters and in sensitivity analyses.

Interestingly, the results were similar whether prehospitalization eGFR, eGFR slope, and proteinuria were all accounted for (Table 4; model 5) or only prehospitalization eGFR was (Table 4; model 3a). Despite eGFR slope and proteinuria being associated with both the exposure (AKI) and all outcomes (Supplemental Table 1), adjustment for them did not have much additional effect on AKI-outcome associations (Table 4; models 4 and 5) beyond absolute eGFR, suggesting their confounding effects are accounted for by other variables in the model. This finding may be reassuring to AKI researchers whose datasets include a single pre-AKI eGFR measurement but do not have pre-AKI eGFR slope or proteinuria available. At least for the purposes of evaluating associations between AKI and cardiovascular outcomes, as long as pre-AKI eGFR (almost certainly the most readily available variable) is included, then the others may not be required. Indeed, the magnitudes of risks associated with AKI in our results were similar to previous reports1–5 where some but not all these prehospitalization renal variables were available.

AKI remained significantly associated with cardiovascular and mortality outcomes in our fully adjusted model. These persistent associations are particularly notable because most of the AKI cases were stage 1 AKI (79%, a proportion similar to that seen in other AKI studies2,4,5). The hazard ratios for these adverse outcomes for AKI were higher than for a 10 ml/min per 1.73 m2 lower eGFR or a 10 mm Hg higher blood systolic BP (compare model 2 in Table 4 with the models in Supplemental Table 1). These associations may be causal or due to residual confounding. Causality may be less likely given that years often elapsed between AKI and the outcome event (Table 3), although it is conceivable that AKI's effect on traditional cardiovascular risk factors (e.g., eGFR) and nontraditional risk factors (e.g., tubular damage or cytokine levels) might take years to cause an event. It is likely that some residual confounding exists in our analysis related to the severity of illness during hospitalization (e.g., median length of stay 5 versus 1 day), but it is difficult to determine whether such hospitalization differences may be effects of AKI rather than confounders.

Regardless of whether the associations with AKI are truly causal, AKI clearly captures information on cardiovascular risk and should signal clinicians to optimize cardiovascular risk factors among AKI survivors. Recognition of the higher cardiovascular risk associated with AKI, beyond that associated with CKD and traditional risk factors, is essential because AKI is common,34–36 and the incidence is increasing by some estimates.35,37–39 Attention to cardiovascular risk in AKI follow-up clinics may be one promising path to improved outcomes in this vulnerable population.40–42 A recent study of an AKI follow-up clinic in Canada found that attendance was associated with fewer major adverse cardiovascular events, mostly driven by all-cause mortality (but interestingly not with fewer major adverse kidney events).42 Higher use of cardioprotective medications, including β-blockers, statins, and SGLT2 inhibitors (but not ACEi/ARB), was observed and may be responsible for the benefits observed (attention to cardioprotective medications was part of the standardized assessment in the AKI follow-up clinic). There were also more visits to a cardiologist among those who attended the AKI follow-up clinic.42

Strengths of our study include the ability to examine pre-AKI eGFR slope and pre-AKI proteinuria, systematically captured per a prospective research study protocol. These variables are rarely captured in such an unbiased manner in previous AKI studies, which are often based on data collected as part of routine clinical care (so there is ascertainment bias in that those with more measurements of eGFR and proteinuria are likely different from those with fewer measurements). Even prospective studies of AKI such as the ASSESS-AKI study43 and the AKI Risk In Derby study44 do not have systematically captured information on pre-AKI eGFR slope or pre-AKI proteinuria because participants are enrolled only at time of the index AKI hospitalization, and thus, biosample collection for research protocol–driven measurement of eGFR and proteinuria are not available before the index hospitalization. Our study used actual observed serum creatinine values abstracted from hospitalization records to enable laboratory-defined AKI classification, which is an advancement over reliance on diagnostic codes to capture AKI because diagnostic codes are known to have suboptimal performance.45,46 Another strength is that the outcomes were systemically captured over long-term follow-up and rigorously adjudicated by at least two physicians.31

Limitations of our study include a lack of information on the etiologies of the observed AKI episodes because the prognostic implications of AKI vary by etiology and clinical context,47 although there is no established adjudication method for AKI etiology.48 Our cohort was comprised entirely of adults with CKD, so it is unknown whether our results may be extrapolated to children or to adults without CKD. We did not include additional possible AKI episodes that occurred during follow-up, and patients who experienced AKI in the past are more likely to experience AKI again, so the observed associations may reflect the combined effects of multiple AKI episodes. However, this limitation is shared by many other studies of long-term outcomes after AKI.2,4,5,44 The preponderance of stage 1 AKI limited the power of our analysis of risks by AKI stage (Supplemental Table 2). We did not have information on severity of illness during hospitalization (e.g., whether patients were in the intensive care unit or needed mechanical ventilation).

In conclusion, associations between AKI and adverse outcomes such as heart failure and atherosclerotic cardiovascular events are confounded by differences in prehospitalization characteristics, but these associations remain significant after adjusting for prehospitalization variables. Prehospitalization eGFR, eGFR slope, and proteinuria were all confounding variables, but risks were similar after adjustment for each of these variables individually or in combination, suggesting their confounding effects are not independent. Our results argue that the observed associations between AKI and higher rates of cardiovascular events and death cannot be explained entirely by confounding because of differences in prehospitalization levels of eGFR, GFR slope, or proteinuria. Interventions to reduce cardiovascular disease risk should be an important component of follow-up care in patients who experience AKI.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study Investigators: Lawrence J. Appel, Debbie L. Cohen, Harold I. Feldman, Robert G. Nelson, Mahboob Rahman, Panduranga S. Rao, Vallabh O. Shah, and Mark L. Unruh.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Lawrence J. Appel, Debbie L. Cohen, Harold I. Feldman, Robert G. Nelson, Mahboob Rahman, Panduranga S. Rao, Vallabh O. Shah, and Mark L. Unruh

Disclosures

C.J. Diamantidis reports consultancy for Optum Labs/UnitedHealth Group; stock in Roblox; research funding from NIDDK and PCORI; and advisory or leadership roles for DSMB for NIDDK COPE-AKI Study, Editorial Board for Contemporary Clinical Trials, Scientific Advisory Board for National Kidney Foundation, and Steering Committee for National Kidney Foundation Patient Network. A.S. Go reports employment with Kaiser Permanente Northern California and research funding from Amarin Pharmaceuticals, Bristol Meyers Squibb, CSL Behring, Janssen Research and Development, Novartis, and Pfizer. E.J. Horwitz reports other interests or relationships as medical director for in-patient dialysis services at MetroHealth Medical Center contracted with Fresenius Kidney Care and reports serving as a member of American Society of Nephrology (ASN) and member of the International Society of Peritoneal Dialysis (ISPD). C.-y. Hsu consulted for legal cases involving acute or CKD (Lewis Brisbois and McMasters Keith Butler), reports consulting on an ad hoc basis for companies regarding kidney disease (Aria Pharma and Triangle Insights Group), reports being paid for serving as a Steering Committee member on an industry-funded trial (LG Chem), and reports research funding from Satellite Healthcare and royalties from UpToDate. J.Y. Hsu reports advisory or leadership roles as an American Journal of Kidney Diseases Statistics/Epidemiology Editor, American Medical Association Statistical Reviewer, and member of PLOS One Statistical Advisory Board. J.P. Lash reports an advisory or leadership role for Kidney360. K.D. Liu reports consultancy for AM Pharma, Biomerieux, BOA Medical, Neumora, and Seastar Medical; stock in Amgen; and other interests or relationships from UpToDate. I.E. McCoy reports ownership interest in Google and Meta and research funding from Satellite Healthcare Inc. (nonprofit). A. Srivastava reports consultancy for CVS Caremark and Tate & Latham (Medicolegal consulting) and honoraria from AstraZeneca, Bayer, FNIH, and Horizon Therapeutics PLC. J. Taliercio reports consultancy for AstraZeneca, Merck & Co, Inc., and Otsuka and speakers bureau for Merck & Co, Inc. M.R. Weir reports consultancy for Akebia, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, CareDx, Janssen, Merck, Novo Nordisk, and Vifor Pharma—all are modest (less than $10,000); honoraria from above for ad hoc advisory board meetings; and advisory or leadership roles for above for ad hoc advisory board. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This work was funded by R01DK114014, K23DK128605, R01DK122797, and K24DK92291. Funding for the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study was obtained under a cooperative agreement from the NIDDK (grants U01DK060990, U01DK060984, U01DK061022, U01DK061021, U01DK061028, U01DK060980, U01DK060963, U01DK060902, and U24DK060990) and by Clinical and Translational Science Awards to the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania (NIH/NCATS UL1TR000003), Johns Hopkins University (UL1TR000424), University of Maryland (GCRC M01RR16500), Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland (UL1TR000439) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research, Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research (UL1TR000433), University of Illinois at Chicago (UL1RR029879), Tulane Center of Biomedical Research Excellence for Clinical and Translational Research in Cardiometabolic Diseases (P20GM109036), Kaiser Permanente (NIH/NCRR UCSF-CTSI UL1RR024131), and the Department of Internal Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine (NM R01DK119199).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Alan S. Go, Jiang He, Chi-yuan Hsu, Jesse Y. Hsu, Kathleen D. Liu, Ian E. McCoy, Xiaoming Zhang.

Data curation: Jesse Y. Hsu, Xiaoming Zhang.

Formal analysis: Jesse Y. Hsu, Xiaoming Zhang.

Funding acquisition: Alan S. Go, Jiang He, Chi-yuan Hsu, Jesse Y. Hsu, Kathleen D. Liu.

Investigation: Jing Chen, Clarissa J. Diamantidis, Paul Drawz, Alan S. Go, Jiang He, Edward J. Horwitz, Matthew R. Weir, Jesse Y. Hsu, James P. Lash, Kathleen D. Liu, Ian E. McCoy, Anand Srivastava, Jonathan Taliercio, Matthew R. Weir, Xiaoming Zhang.

Methodology: Alan S. Go, Jiang He, Chi-yuan Hsu, Jesse Y. Hsu, Kathleen D. Liu, Ian E. McCoy, Xiaoming Zhang.

Project administration: Chi-yuan Hsu, Ian E. McCoy.

Software: Jesse Y. Hsu.

Supervision: Chi-yuan Hsu.

Visualization: Ian E. McCoy.

Writing – original draft: Chi-yuan Hsu, Ian E. McCoy.

Writing – review & editing: Jing Chen, Clarissa J. Diamantidis, Paul Drawz, Alan S. Go, Jiang He, Edward J. Horwitz, Chi-yuan Hsu, Jesse Y. Hsu, James P. Lash, Kathleen D. Liu, Ian E. McCoy, Anand Srivastava, Jonathan Taliercio, Matthew R. Weir, Xiaoming Zhang.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://links.lww.com/CJN/B764.

Supplemental Table 1. Adjusted hazard ratios for prehospitalization variables.

Supplemental Table 2. Adjusted hazard ratios (model 5) of AKI stage for four outcomes.

Supplemental Table 3. Sensitivity analyses for alternative AKI/non-AKI definitions.

Supplemental Figure 1. Cohort assembly.

References

- 1.See EJ Jayasinghe K Glassford N, et al. Long-term risk of adverse outcomes after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies using consensus definitions of exposure. Kidney Int. 2019;95(1):160–172. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2018.08.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bansal N Matheny ME Greevy RA, et al. Acute kidney injury and risk of incident heart failure among US Veterans. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;71(2):236–245. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.08.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Odutayo A Wong CX Farkouh M, et al. AKI and long-term risk for cardiovascular events and mortality. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(1):377–387. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016010105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Go AS Hsu CY Yang J, et al. Acute kidney injury and risk of heart failure and atherosclerotic events. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13(6):833–841. doi: 10.2215/CJN.12591117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ikizler TA Parikh CR Himmelfarb J, et al. A prospective cohort study of acute kidney injury and kidney outcomes, cardiovascular events, and death. Kidney Int. 2021;99(2):456–465. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.06.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindner A, Charra B, Sherrard DJ, Scribner BH. Accelerated atherosclerosis in prolonged maintenance hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 1974;290(13):697–701. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197403282901301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shlipak MG Fried LF Cushman M, et al. Cardiovascular mortality risk in chronic kidney disease: comparison of traditional and novel risk factors. JAMA. 2005;14(7):14–15. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.14.1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarnak MJ Levey AS Schoolwerth AC, et al. Kidney disease as a risk factor for development of cardiovascular disease: a statement from the American heart association councils on kidney in cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure research, clinical cardiology, and epidemiology and prevention. Circulation. 2003;108(17):2154–2169. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000095676.90936.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu C. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1296–1305. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa041031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leaf DE Christov M Jüppner H, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 levels are elevated and associated with severe acute kidney injury and death following cardiac surgery. Kidney Int. 2016;89(4):939–948. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2015.12.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang M Hsu R Hsu C, et al. FGF-23 and PTH levels in patients with acute kidney injury: a cross-sectional case series study. Ann Intensive Care. 2011;1(1):21–27. doi: 10.1186/2110-5820-1-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Legrand M, Rossignol P. Cardiovascular consequences of acute kidney injury. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(23):2238–2247. doi: 10.1056/nejmra1916393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doi K, Rabb H. Impact of acute kidney injury on distant organ function: recent findings and potential therapeutic targets. Kidney Int. 2016;89(3):555–564. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2015.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golestaneh L, Melamed ML, Hostetter TH. Uremic memory: the role of acute kidney injury in long-term outcomes. Kidney Int. 2009;76(8):813–814. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simmons EM Himmelfarb J Sezer MT, et al. Plasma cytokine levels predict mortality in patients with acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 2004;65(4):1357–1365. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00512.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Himmelfarb J, Le P, Klenzak J, Freedman S, McMenamin ME, Ikizler TA. Impaired monocyte cytokine production in critically ill patients with acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 2004;66(6):2354–2360. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.66023.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hüsing AM Wulfmeyer VC Gaedcke S, et al. Myeloid CCR2 promotes atherosclerosis after AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022;33(8):1487–1500. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2022010048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corrales-Medina VF Alvarez KN Weissfeld LA, et al. Association between hospitalization for pneumonia and subsequent risk of cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2015;313(3):264–274. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.18229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smeeth L, Thomas SL, Hall AJ, Hubbard R, Farrington P, Vallance P. Risk of myocardial infarction and stroke after acute infection or Vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(25):2611–2618. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa041747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsu RK, Hsu CY. Proteinuria and reduced glomerular filtration rate as risk factors for acute kidney injury. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2011;20(3):211–217. doi: 10.1097/mnh.0b013e3283454f8d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hapca S Siddiqui MK Kwan RSY, et al. The relationship between AKI and CKD in patients with type 2 diabetes: an observational cohort study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32(1):138–150. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020030323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen JB Yang W Li L, et al. Time-updated changes in estimated GFR and proteinuria and major adverse cardiac events: findings from the chronic renal insufficiency cohort (CRIC) study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2022;79(1):36.e1–44.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2021.03.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coresh J Turin TC Matsushita K, et al. Decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate and subsequent risk of end-stage renal disease and mortality. JAMA. 2014;311(24):2518–2531. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.6634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsushita K, Selvin E, Bash LD, Franceschini N, Astor BC, Coresh J. Change in estimated GFR associates with coronary heart disease and mortality. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(12):2617–2624. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009010025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turin TC Coresh J Tonelli M, et al. Change in the estimated glomerular filtration rate over time and risk of all-cause mortality. Kidney Int. 2013;83(4):684–691. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hannan M Ansari S Meza N, et al. Risk factors for CKD progression: overview of findings from the CRIC study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;16(4):648–659. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07830520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ishigami J Taliercio JT Feldman HI, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and risk of hospitalization with infection in chronic kidney disease: the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(8):1836–1846. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2019101106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schrauben SJ Chen HY Lin E, et al. Hospitalizations among adults with chronic kidney disease in the United States: a cohort study. PLoS Med. 2020;17(12):e1003470. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kellum JA Lameire N Aspelin P, et al. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) acute kidney injury work group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2(1):1–138. doi: 10.1038/kisup.2012.1 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin J Fernandez H Shashaty MGS, et al. False-positive rate of AKI using consensus creatinine–based criteria. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(10):1723–1731. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02430315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu KD Yang W Go AS, et al. Urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin and risk of cardiovascular disease and death in CKD: results from the chronic renal insufficiency cohort (CRIC) study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65(2):267–274. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.07.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson AH Yang W Hsu CY, et al. Estimating GFR among participants in the chronic renal insufficiency cohort (CRIC) study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(2):250–261. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCoy IE Hsu JY Bonventre JV, et al. Acute kidney injury associates with long-term increases in plasma TNFR1, TNFR2, and KIM-1: findings from the CRIC study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022;33(6):1173–1181. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2021111453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lewington AJP, Cerdá J, Mehta RL. Raising awareness of acute kidney injury: a global perspective of a silent killer. Kidney Int. 2013;84(3):457–467. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoste EAJ Kellum JA Selby NM, et al. Global epidemiology and outcomes of acute kidney injury. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018;14(10):607–625. doi: 10.1038/s41581-018-0052-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sawhney S Robinson HA Van Der Veer SN, et al. Acute kidney injury in the UK: a replication cohort study of the variation across three regional populations. BMJ Open. 2018;8(6):e019435. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hsu RK, McCulloch CE, Dudley RA, Lo LJ, Hsu CY. Temporal changes in incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(1):37–42. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012080800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xue JL Daniels F Star RA, et al. Incidence and mortality of acute renal failure in Medicare beneficiaries, 1992 to 2001. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(4):1135–1142. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005060668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hsu CY, McCulloch CE, Fan D, Ordoñez JD, Chertow GM, Go AS. Community-based incidence of acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 2007;72(2):208–212. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harel Z Wald R Bargman JM, et al. Nephrologist follow-up improves all-cause mortality of severe acute kidney injury survivors. Kidney Int. 2013;83(5):901–908. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu VC Chueh JS Chen L, et al. Nephrologist follow-up care of patients with acute kidney disease improves outcomes: Taiwan experience. Value Health. 2020;23(9):1225–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2020.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Silver SA Adhikari NK Jeyakumar N, et al. Association of an acute kidney injury follow-up clinic with patient outcomes and care processes: a cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2022;81(5):554–563.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2022.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Go AS Parikh CR Ikizler TA, et al. The assessment, serial evaluation, and subsequent sequelae of acute kidney injury (ASSESS-AKI) study: design and methods. BMC Nephrol. 2010;11(1):22–13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-11-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Horne KL, Shardlow A, Taal MW, Selby NM. Long term outcomes after acute kidney injury: lessons from the ARID study. Nephron. 2015;131(2):102–106. doi: 10.1159/000439066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grams ME, Waikar SS, MacMahon B, Whelton S, Ballew SH, Coresh J. Performance and limitations of administrative data in the identification of AKI. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(4):682–689. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07650713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Waikar SS Wald R Chertow GM, et al. Validity of international classification of diseases, ninth revision? Clinical modification codes for acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(6):1688–1694. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006010073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McCoy IE, Chertow GM. AKI—a relevant safety end point? Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;75(4):508–512. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koyner JL Garg AX Thiessen-Philbrook H, et al. Adjudication of etiology of acute kidney injury: experience from the TRIBE-AKI multi-center study. BMC Nephrol. 2014;15(1):105–109. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-15-105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]