Undocumented immigrants comprise an estimated 11 million of the US population. Access to health care for this community is limited; nearly 50%–70% lack health care insurance.1 Undocumented immigrants can receive primary care through safety-net clinics, such as federally qualified health centers, and they can receive emergency medical treatment as mandated by the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA). There are medical conditions, however, with treatments that do not fall into primary care or emergency medical care, as strictly defined by EMTALA. This is the case for undocumented immigrants with kidney failure.

There are an estimated six to 9000 undocumented immigrants with kidney failure across the United States.2 The 1972 Medicare ESKD entitlement program provides health care coverage of all kidney replacement therapy options for US citizens and permanent residents present for 5 years, regardless of age.2 Undocumented immigrants are not eligible for this Medicare benefit. In 2019, 12 states provided state-wide access to outpatient thrice-weekly hemodialysis through Medicaid or Emergency Medicaid. In the other 38 states, undocumented immigrants did not have uniform state-wide access to kidney replacement therapy through Medicaid or Emergency Medicaid; in those states, many relied on emergency only hemodialysis (dialysis only after presenting critically ill to an emergency department). The costs of emergency-only hemodialysis are likely different than providing routine thrice-weekly hemodialysis sessions or home dialysis. Providing care to a growing number of patients who may need treatment may generate concern about costs.

Before 2019 in Colorado, undocumented immigrants could only receive dialysis approximately every 7 days and if they met hospital-based criteria qualifying as a medical emergency, as mandated by EMTALA. Under EMTALA, uninsured individuals can only receive health care coverage if treatment is for an emergency medical condition “such that absence of immediate medical attention could reasonably be expected to result in placing the patient's health in serious jeopardy, serious impairment to the bodily functions, or serious dysfunction of any bodily organ or part” (Social Security Act 1903; https://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/ssact/title19/1903.htm). Research demonstrated that undocumented immigrants who rely on emergency-only hemodialysis and their family caregivers (who are often US citizens) experience psychosocial distress from weekly near-death experiences.3,4 Their treating clinicians report drivers of burnout from witnessing needless suffering and moral distress from providing care on the basis of nonmedical factors, such as immigration and health insurance status.5 In addition, compared with undocumented immigrants who receive routine thrice-weekly hemodialysis, these patients have a 5- and 14-fold higher 1- and 5-year mortality rates, respectively, as well as higher resource utilization.6,7

Under EMTALA, the services and conditions that qualify as an emergency and are reimbursed under Emergency Medicaid are decided at the state level. In 1997, the Office of the Inspector General affirmed the state's role in defining an emergency medical condition: “Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services allows each state to identify which conditions qualify as emergencies” (Office of the Inspector General Report on New Jersey's Program A-02-07-01038; https://oig.hhs.gov/oas/reports/region2/20701038.pdf). Before 2019, undocumented immigrants in Colorado qualified for Emergency Medicaid health care coverage for emergency dialysis. This health care coverage included emergency department visit and hospitalization; outpatient-related services (e.g., medications and surgeries) were not included. In 2019, Colorado decided to include the diagnosis of kidney failure as a qualifying condition for Emergency Medicaid, thereby expanding health care coverage to outpatient thrice-weekly hemodialysis, home dialysis, as well as health care coverage of dialysis-related medications and surgeries for undocumented immigrants with kidney failure.8 Undocumented immigrants who transition from emergency to routine thrice-weekly hemodialysis in Colorado reported an improvement in quality of life and symptom burden and felt that their humanity had been restored.9 Research demonstrates that, in general, undocumented immigrants with kidney failure are more likely to work because they do not receive federal benefits. With this health care policy change, undocumented immigrants are able to work and contribute a tax surplus to the US financing system, helping to subsize the health care of US residents.10

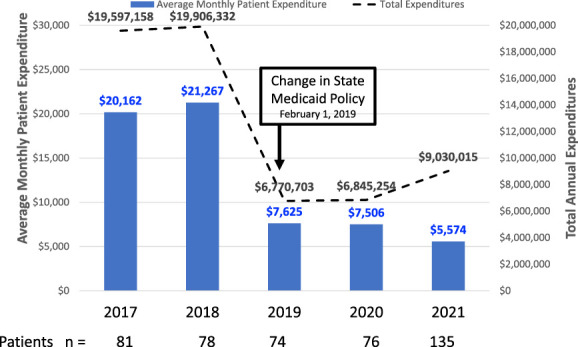

The health care policy change in Colorado reimbursing outpatient dialysis centers at Medicaid rates took effect on February 1, 2019. Data from the Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing show that the annual Emergency Medicaid Service (EMS) dialysis expenditures for all undocumented immigrants with kidney failure undergoing emergency-only hemodialysis in 2017 and 2018 (n=81 and n=78 per month, respectively) was almost $20,000,000, with an average monthly EMS dialysis patient expenditure of $20,000 (Figure 1). After the health care policy change, in 2019 and 2020, total annual and monthly expenditures decreased almost three-fold and by 2021, total monthly expenditures decreased four-fold. In 2021, total annual expenditures increased to over $9,000,000, with an increase in the number of patients served (n=135 per month); however, the average monthly patient expenditure remained lower at $5574. While the number of undocumented immigrants with kidney failure has increased, the Medicaid program in Colorado is paying less than half of what it paid before the health care policy change. Evaluation over time is needed to know whether the cost savings can be sustained if care is extended to more patients. In addition, states that may similarly benefit would be those similar to Colorado, where Emergency Medicaid pays for the emergency department visit and hospitalization related to emergency dialysis. Finally, our findings are similar to a Houston, Texas, study that assessed 1-year cost savings among undocumented immigrants with kidney failure who transitioned from emergency dialysis to scheduled dialysis after enrolling into private health insurance. They estimated a net savings of nearly $6000 per person per month or $720,000 per person per year.7

Figure 1.

Medicaid dialysis expenditures for undocumented immigrants before and after change in state Medicaid policy.

There are several explanations for the increase in the number of undocumented immigrants with kidney failure in the state. There may be concern that more undocumented patients with kidney failure are being attracted to the state by the change in health care coverage policy. However, as patients transitioned to standard outpatient dialysis, their risk of mortality likely decreased as shown in prior studies.6,7 Likely, newly diagnosed patients with kidney failure add to the number of existing patients who are living longer. It is possible that changes in risk factors of kidney failure (e.g., coronavirus disease 2019 and diabetes), which disproportionately burden the undocumented immigrant community, could contribute to increases in the kidney failure incidence.

The National Kidney Foundation and the American Society of Nephrology have urged state Medicaid directors to expand access to kidney replacement therapy, including kidney transplantation, for undocumented immigrants in a letter that was supported by several physician organizations, including the Society of General Internal Medicine, the American Society of Nephrology, and the Society of Hospital Medicine. Clinician and advocacy groups have engaged in changing access to kidney replacement therapy for undocumented immigrants in their states. Indeed, a Colorado team of clinicians, community organizations, and state Medicaid employees described the Medicaid policy strategy to inform other states similarly interested in expanding this access.8 In addition, a national approach to expanding access to kidney replacement therapy may be more effective and may address concerns regarding the movement of undocumented immigrants to states where there is adequate health care coverage. This economic analysis demonstrates that states seeking to control Medicaid program costs should consider expanding access to care for undocumented immigrants with kidney failure. Doing so, not only helps contain costs but also benefits patients, caregivers, and providers challenged by the provision of emergency-only hemodialysis care for kidney failure.

Disclosures

L. Cervantes reports Research Funding: Retrophin; and Other Interests or Relationships: Center for Health Progress Board of Directors, Denver Health Board of Directors, and National Kidney Foundation. N.R. Powe reports Advisory or Leadership Role: Hennepin Healthcare Research Institute, Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute, Portland VA Research Foundation, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, University of Washington, and Vanderbilt University. K. Rizzolo reports Other Interests or Relationships: ASN Health Care Justice Committee. S.L. Tummalapalli reports Research Funding: Scanwell Health; and Other Interests or Relationships: Travel support through Abbott Pharmaceuticals and the International Society of Nephrology.

Funding

Dr. L. Cervantes is supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) K23 Mentored Patient-Oriented Research (K23DK117018) and the RWJF Clinical Scholars Program (77887). Dr. S.L. Tummalapalli is supported by funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K08HS028684). Dr. K. Rizzolo is supported by the NIDDK (5T32DK007135-46).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Lilia Cervantes, Neil R. Powe, Sri Lekha Tummalapalli.

Data curation: Lilia Cervantes, Neil R. Powe.

Formal analysis: Lilia Cervantes, Neil R. Powe.

Resources: Lilia Cervantes, Neil R. Powe.

Supervision: Neil R. Powe, Sri Lekha Tummalapalli.

Writing – original draft: Lilia Cervantes, Katherine Rizzolo.

Writing – review & editing: Lilia Cervantes, Neil R. Powe, Katherine Rizzolo, Sri Lekha Tummalapalli.

References

- 1.Migration Policy Institute. Profile of the unauthorized population: United States. Accessed December 14, 2022. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/data/unauthorized-immigrant-population/state/US.

- 2.Rizzolo K, Cervantes L. Immigration status and end-stage kidney disease: role of policy and access to care. Semin Dial. 2020;33(6):513–522. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cervantes L Fischer S Berlinger N et al.. The illness experience of undocumented immigrants with end-stage renal disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(4):529–535. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cervantes L Carr AL Welles CC et al.. The experience of primary caregivers of undocumented immigrants with end-stage kidney disease that rely on emergency-only hemodialysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(8):2389–2397. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05696-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cervantes L Richardson S Raghavan R et al.. Clinicians' perspectives on providing emergency-only hemodialysis to undocumented immigrants: a qualitative study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(2):78–86. doi: 10.7326/m18-0400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cervantes L Tuot D Raghavan R et al.. Association of emergency-only vs standard hemodialysis with mortality and health care use among undocumented immigrants with end-stage renal disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(2):188–195. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nguyen OK Vazquez MA Charles L et al.. Association of scheduled vs emergency-only dialysis with health outcomes and costs in undocumented immigrants with end-stage renal disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(2):175–183. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cervantes L, Johnson T, Hill A, Earnest M. Offering better standards of dialysis care for immigrants: the Colorado example. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15(10):1516–1518. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01190120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cervantes L, Tong A, Camacho C, Collings A, Powe NR. Patient-reported outcomes and experiences in the transition of undocumented patients from emergency to scheduled hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2021;99(1):198–207. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ommerborn MJ, Ranker LR, Touw S, Himmelstein DU, Himmelstein J, Woolhandler S. Assessment of immigrants’ premium and tax payments for health care and the costs of their care. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5(11):e2241166. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.41166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]