Abstract

Doxorubicin-overproducing strains of Streptomyces peucetius ATCC 29050 can be obtained through manipulation of the genes in the region of the doxorubicin (DXR) gene cluster that contains dpsH, the dpsG polyketide synthase gene, the putative dnrU ketoreductase gene, dnrV, and the doxA cytochrome P-450 gene. These five genes were characterized by sequence analysis, and the effects of replacing dnrU, dnrV, doxA, or dpsH with mutant alleles and of doxA overexpression on the production of the principal anthracycline metabolites of S. peucetius were studied. The exact roles of dpsH and dnrV could not be established, although dnrV is implicated in the enzymatic reactions catalyzed by DoxA, but dnrU appears to encode a ketoreductase specific for the C-13 carbonyl of daunorubicin (DNR) and DXR or their biosynthetic precursors. The highest DXR titers were obtained in a dnrX dnrU (N. Lomovskaya, Y. Doi-Katayama, S. Filippini, C. Nastro, L. Fonstein, M. Gallo, A. L. Colombo, and C. R. Hutchinson, J. Bacteriol. 180:2379–2386, 1998) double mutant and a dnrX dnrU dnrH (C. Scotti and C. R. Hutchinson, J. Bacteriol. 178:7316–7321, 1996) triple mutant. Overexpression of doxA in a doxA::aphII mutant resulted in the accumulation of DXR precursors instead of in a notable increase in DXR production. In contrast, overexpression of dnrV and doxA jointly in the dnrX dnrU double mutant or the dnrX dnrU dnrH triple mutant increased the DXR titer 36 to 86%.

Daunorubicin (DNR) and doxorubicin (DXR) are clinically important chemotherapeutic agents, and in spite of undesirable acute and long-term toxic effects, DXR remains one of the most widely used agents for antitumor therapy (6, 45). DXR was first isolated in 1969 (7) from Streptomyces peucetius subsp. caesius ATCC 27952, a mutant strain derived from S. peucetius ATCC 29050, and is formed by C-14 hydroxylation of its immediate precursor, DNR (Fig. 1). Although a number of organisms (including strain 29050) are known to produce DNR (26), S. peucetius subsp. caesius has been the only organism reported to produce DXR, which currently is obtained commercially by the chemical conversion of the more abundant DNR. Since DXR is expensive, the development of improved strains or processes for its production would be beneficial. One of the many approaches for the realization of this goal is the cloning and characterization of the gene(s) responsible for the conversion of DNR to DXR. It had been tacitly assumed that strain 27952 and the mutants derived from it were the only DXR producers (5, 26). However, about 10 years ago we found that strain 29050 produces significant quantities of DXR when it is grown in a highly-buffered DXR production medium developed in our laboratory. This finding eventually led us to characterize the region of the DNR-DXR gene cluster in strain 29050 that governs DXR production.

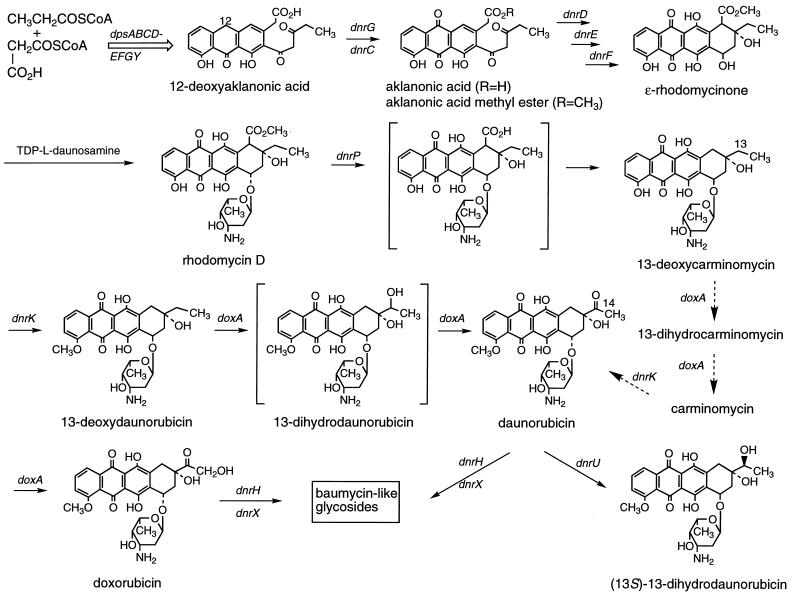

FIG. 1.

Abbreviated pathway for biosynthesis of DNR and DXR from propionyl-coenzyme A, malonyl-coenzyme A, and thymidine-diphospho (TDP)-d-glucose. Open arrows indicate multiple steps between the precursor and product shown. Gene functions are indicated above or adjacent to the steps they govern. Intermediates that have not been isolated and characterized are enclosed in brackets. The main route from 13-deoxycarminomycin to DNR is depicted by the solid arrows, and a possible subsidiary route is depicted by the dashed arrows, as proposed by Dickens et al. (19) and supported by the study of DoxA in vitro (59a). The absolute stereochemistry of the 13-hydroxyl group in the 13-dihydro anthracyclines is unknown.

Here we report the results of gene sequence analysis and disruption or replacement experiments on the region of the DNR-DXR cluster that contains dpsH, the dpsG polyketide synthase gene, the putative dnrU ketoreductase gene, and the dnrV and doxA genes (Fig. 2). The latter gene encodes a dual-function cytochrome (CY) P-450 hydroxylase that may act together with the product of dnrV to convert 13-deoxycarminomycin or 13-deoxy-DNR to DNR and hydroxylate DNR to DXR. Although the role of the dpsH gene could not be deduced, the dpsG gene has been shown to encode the acyl carrier protein component of the DNR/DXR polyketide synthase (dps) in other work from our laboratory (25, 43) as well as by Strohl and coworkers, who have studied the Streptomyces sp. strain C5 dpsG homolog (18, 20). The distinctive changes in the metabolic profile of dnrV and doxA mutants, on the other hand, confirm the role assigned by Dickens and Strohl (18) and Dickens et al. (19) to the doxA homolog in Streptomyces sp. strain C5 through expression in a heterologous host but also implicate dnrV in the oxidation events catalyzed by DoxA. Disruption of dnrU, encoding a putative ketoreductase, caused a notable increase in DXR production, most likely by eliminating the reduction of DNR to 13-dihydro-DNR. In fact, DXR was the major product seen in dnrX dnrU mutants of the wild-type strain and in a dnrU mutant of a DNR-overproducing strain, in which the yield of DXR was increased three to four times over that of the dnrU+ strain (22). By combining the dnrH (52) and dnrX (40) mutations that cause increased DNR or DXR production, respectively, with the dnrU mutation in a single background, DXR production was increased over that obtained with the S. peucetius dnrX dnrU double mutant when the triple mutant was grown in an optimized medium. Thus, industrially useful DXR-overproducing strains can be produced by genetic engineering.

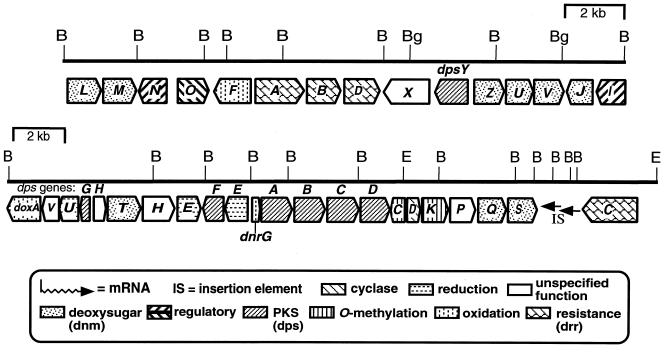

FIG. 2.

Physical and functional map of the DNR-DXR gene cluster. The relative sizes of the ORFs and the direction of gene transcription are designated by pointed boxes, which are shaded according to the types of functions, indicated below the restriction map. dps indicates PKS and cyclase genes involved in assembly of 12-deoxyaklanonic acid, dnm indicates the genes required for the biosynthesis of thymidine-diphospho-l-daunosamine, drr indicates the DNR and DXR self-resistance genes, and dnr indicates all other types of genes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and phages.

Escherichia coli DH5 (50) and pUC19 (60) and the pGEM7Zf(−), pSP72 (Promega, Madison, Wis.), pSE380 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.), Litmus 28 and Litmus 38 (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.), and pCMV.SPORT3 (Gibco BRL Products, Grand Island, N.Y.) plasmids were used for routine subcloning. pFDNeoS, containing the aphII kanamycin-neomycin resistance gene, was from Denis and Brzezinski (16). The high-copy-number Streptomyces shuttle vectors pWHM3 and pWHM1250 (a derivative of pWHM3 containing the ermEp* promoter) were from Vara et al. (59) and Madduri et al. (42), respectively. The pWHM335 cosmid clone containing a fragment of the DXR gene cluster was from Stutzman-Engwall and Hutchinson (56). pWHM951 and pWHM959 were from Scotti and Hutchinson (52). The Streptomyces strains, other plasmids, and øC31-derived phages used in this study are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and phages

| Strain, plasmid, or phage | Genotype or relevant phenotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| S. peucetius ATCC 29050 | Wild type | American Type Culture Collection |

| WMH1530 | dnrN::aphII | 46 |

| WMH1650 | dnrX::aphII | 40 |

| WMH1658 | dnrU::aphII | This work |

| WMH1662 | dnrX::aphII dnrU::aphII | This work |

| WMH1663 | dnrV::aphII | This work |

| WMH1664, WMH1665 | doxA::aphII | This work |

| WMH1666 | dpsH::aphII | This work |

| WMH1667, WMH1668 | dnrX::aphII dnrU::aphII dnrH::aac(IV); SLP1−, SLP2−, spectinomycin resistant | This work |

| S. lividans TK23 | 30 | |

| TK24 | SLP1−, SLP2−, streptomycin resistant | 30 |

| WMH1594 | SLP1−, SLP2−, streptomycin resistant, φC31 lysogen | 40 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pWHM249 | XhoI site eliminated from the aphII gene in pFDNeoS | 40 |

| pWHM555 | 6.0-kb BamHI fragment cloned from pWHM335 into pUC19 | This work |

| pWHM289 | 4.8-kb BamHI-NruI fragment cloned from pWHM555 into pSE380 | This work |

| pWHM290 | 4.8-kb BamHI-XhoI fragment cloned from pWHM299 into pSP72 | This work |

| pWHM293 | 1.0-kb SalI fragment containing aphII gene cloned blunt ended from pWHM249 into the filled-in BalI site of pWHM290 | This work |

| pWHM294 | 4.0-kb AatII-XhoI fragment containing the aphII gene cloned blunt ended from pWHM293 into the filled-in PvuII site of pSP72 | This work |

| pWHM298 | 1.55-kb AatII-SstI fragment cloned from pWHM555 into pSE380 | This work |

| pWHM299 | 1.55-kb EcoRI-HindIII fragment containing the dnrU gene cloned from pWHM298 into pWHM3 | This work |

| pWHM373 | 3.1-kb PvuII-SstI fragment cloned from pWHM555 into pSP72 | This work |

| pWHM374 | 3.1-kb EcoRI-XhoI fragment cloned from pWHM373 into pSE380 | This work |

| pWHM375 | 3.1-kb EcoRI-HindIII fragment containing dnrU and dnrV genes cloned from pWHM374 into pWHM3 | This work |

| pWHM381 | 1.0-kb SalI fragment containing the aphII gene cloned blunt ended from pWHM249 into the filled-in AatII site of pWHM374 | This work |

| pWHM382 | 4.1-kb EcoRI-XhoI fragment cloned from pWHM381 into pCEM7zf(+) | This work |

| pWHM384 | 1.0-kb SalI-NotI fragment cloned from pWHM373 into pSE380 | This work |

| pWHM385 | 1.0-kb EcoRI-HindIII fragment containing the dnrV gene cloned from pWHM384 into pWHM3 | This work |

| pWHM386 | 2.3-kb BamHI-NotI fragment cloned from pWHM290 into pSE380 | This work |

| pWHM387 | 2.3-kb EcoRI-HindIII fragment containing the dnrV and doxA genes cloned from pWHM386 into pWHM3 | This work |

| pWHM388 | 1.6-kb AgeI-BamHI fragment cloned from pWHM555 into XmaI-BamHI sites of pCMV SPORT3 | This work |

| pWHM389 | 1.6-kb EcoRI-HindIII fragment cloned from pWHM388 into Litmus 38 | This work |

| pWHM390 | 1.6-kb EcoRI-HindIII fragment containing the doxA gene cloned from pWHM389 into pWHM3 | This work |

| pWHM391 | 1.0-kb SalI fragment containing aphII gene cloned blunt ended from pWHM249 into the filled-in BspEI site of pWHM555 | This work |

| pWHM392 | 4.4-kb BamHI-SstI fragment cloned from pWHM391 into pSE380 | This work |

| pWHM394 | 1.0-kb SalI fragment containing the aphII gene cloned blunt ended from pWHM249 into the filled-in NcoI site of pWHM290 | This work |

| pWHM395 | 3.5-kb NotI-XhoI fragment cloned from pWHM394 into pSE380 | This work |

| pWHM546 | 3.7-kb SstI fragment containing the dnrU, dnrV, and doxA genes cloned into pWHM3 | This work |

| pWHM547 | 2.3-kb NotI-BamHI fragment containing the dnrV and doxA genes cloned under the control of the ermEp* promoter in pWHM3 | This work |

| pWHM548 | 1.4-kb KpnI-BamHI fragment containing the doxA gene cloned under the control of the strong constitutive ermEp* promoter into pWHM3 | This work |

| pWHM959 | 0.4-kb internal segment of the dnrH gene cloned into the temperature-sensitive pKC1139 plasmid carrying the aac(IV) apramycin resistance gene | 52 |

| Phages | ||

| KC515 | c+ attP, thiostrepton resistant, viomycin resistant | 11 |

| phWHM295 | c+ attP::vph::4.0-kb XhoI-BamHI fragment::aphII; 4.0-kb XhoI-BamHI fragment cloned from pWHM294 into KC515 | This work |

| phWHM353 | c+ attP::vph:4.1-kb XhoI-BamHI fragment::aphII; 4.1-kb XhoI-BamHI fragment cloned from pWHM352 into KC515 | This work |

| phWHM363 | c+ attP::vph::4.4-kb XhoI-BamHI fragment::aphII; 4.4-kb XhoI-BamHI fragment cloned from pWHM362 into KC515 | This work |

| phWHM366 | c+ attP::vph::3.5-kb XhoI-BamHI fragment::aphII; 3.5-kb XhoI-BamHI fragment cloned from pWHM365 into KC515 | This work |

Biochemicals and chemicals.

Thiostrepton was obtained from S. J. Lucania at Bristol-Myers-Squibb (Princeton, N.J.). ɛ-Rhodomycinone (RHO), DNR, and DXR were obtained from Pharmacia & Upjohn (Milan, Italy). 13-Deoxy-DNR was isolated in this study. Restriction enzymes and other molecular biology reagents were obtained from standard commercial sources.

Media and other growth conditions.

E. coli strains carrying plasmids were grown in Luria-Bertani medium (50) and selected with ampicillin (100 μg ml−1). S. peucetius strains were grown on ISP4 medium (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.). R2YE agar medium (30) was used in transformation experiments, and R2YE agar medium without sucrose was used for infection of S. peucetius with øC31 derivatives and for sporulation of S. lividans TK24 and the TK24 (øC31) lysogen. The minimal medium (MM) of Hopwood et al. (30) was used to screen S. peucetius recombinant clones. S. peucetius strains were grown at 30°C in R2YE liquid medium for preparation of protoplasts and isolation of chromosomal DNA. KC515 derived from øC31 and KC515-derived phages were propagated as described by Hopwood et al. (30).

Production of DXR by S. peucetius ATCC 29050.

The APM medium was developed and used as follows. Five milliliters of seed medium containing (grams/liter) glucose (25), yeast extract (4), malt extract (10), NaCl (2), 3-(morpholino)propanesulfonic acid (MOPS sodium salt) (15), and MgSO4 (0.1) and 10 ml of trace elements consisting of (milligrams/liter) ZnCl2 (40), FeCl3 · 6H2O (200), CuCl2 · 2H2O (10), MnCl2 · 4H2O (10), Na2B4O7 · 10H2O (10), and (NH4)6Mo7O24 · 4H2O (10) was inoculated with spores or mycelium of strain 29050 and incubated at 30°C and 300 rpm in baffled Erlenmeyer flasks. After 24 h of incubation, the seed culture was transferred to 25 ml of the APM production medium containing (grams per liter) glucose (60), yeast extract (8), malt extract (20), NaCl (2), MOPS sodium salt (15), MgSO4 (0.1), FeSO4 · 7H2O (0.01), ZnSO4 · 7H2O (0.01), and antifoam B emulsion (4 ml; Sigma) and incubated in a 250-ml baffled flask as described above for 72 h. Cultures were extracted with chloroform and analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as previously described (47). Under these conditions, strain 29050 produced 4.2 μg of DXR per ml (n = 2) as determined by HPLC assay. To provide further proof of the identity of the metabolite, authentic S. peucetius 29050 (newly obtained from the American Type Culture Collection for this purpose) was grown on a preparative scale (400 ml), and the metabolites were isolated and purified to yield 0.5 mg of DXR.

Isolation and in vitro manipulation of DNA.

Plasmid DNA was isolated from bacterial cells with the Bio 101 kit (Vista, Calif.). Phage DNA was isolated with the Qiagen lambda kit (Chatsworth, Calif.). Total S. peucetius DNA was isolated by the protocol of Hopwood et al. (30). Restriction endonuclease digestion and ligation were performed by standard techniques (50). DNA fragments for labelling and subcloning were isolated with the Qiaex (Qiagen) gel extraction kit. The conditions for phage DNA transfection and S. peucetius transformation were as described by Hopwood et al. (30).

DNA sequencing.

DNA sequencing of both strands of a nucleotide fragment was carried out with DNA fragments subcloned in M13 vectors (61) as previously described (46).

Southern analysis.

Streptomyces chromosomal DNA was digested with restriction endonuclease enzymes for 4 h, electrophoresed in a 0.8% agarose gel overnight, and blotted to Hybond N membranes (Amersham, Chicago, Ill.) by capillary transfer (50). Labelling, hybridization, and detection were carried out with the Genius 1 nonradioactive DNA labelling kit (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Construction of the dnrU::aphII, dnrV::aphII, doxA::aphII, and dpsH::aphII mutants by insert-directed homologous recombination in S. peucetius.

The AatII-NruI, PvuII-SstI, BamHI-SstI, and NotI-NruI DNA fragments were used for insert-directed homologous recombination to disrupt the dnrU, dnrV, doxA, and dpsH genes, respectively, as shown in Fig. 3B. A 1.0-kb SalI fragment containing the aphII gene from pWHM249 (Table 1) was cloned blunt ended into the unique BalI, AatII, BspEI, and NcoI sites located at the beginning of the dnrU, dnrV, doxA, and dpsH genes, respectively (Fig. 3B). The steps required for subcloning the fragments for subsequent cloning into the KC515 phage vector are described in Table 1. The BamHI-XhoI fragments from plasmids pWHM294, pWHM382, pWHM392, and pWHM365 (Fig. 3B) were cloned into KC515 (Fig. 3A) to create recombinant phages phWHM295, phWHM353, phWHM363, and phWHM366, containing disrupted copies of the dnrU, dnrV, doxA, and dnrH genes, respectively. Protoplasts of Streptomyces lividans TK24 were transfected with each of the phage constructs, and the recombinant phages were isolated from plaques by a convenient spot-test method we developed (38). The recombinant phages were characterized phenotypically as containing aphII and vph resistance genes, and the presence of the cloned DNA was confirmed by restriction endonuclease digestion analysis. Infection of S. peucetius 29050 with recombinant phages and selection for gene replacement were carried out as described by Lomovskaya et al. (40).

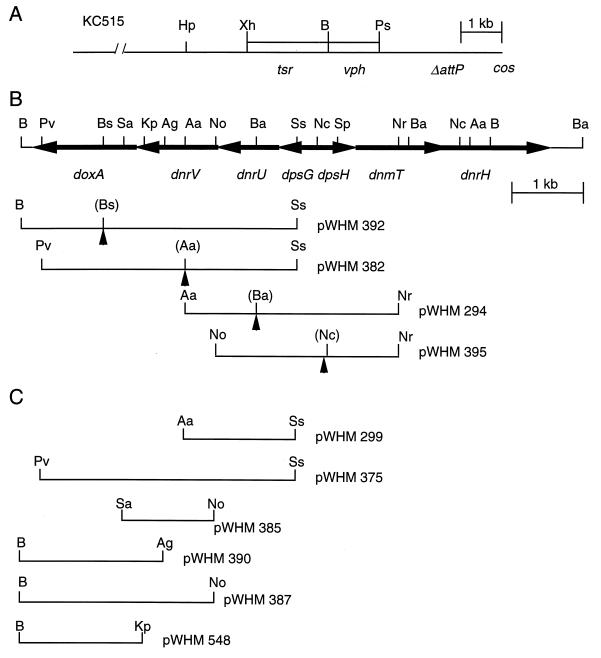

FIG. 3.

(A) Structure of KC515. ΔattP and cos indicate the relative locations of the deletion in the attachment site and the cohesive ends of φC31, respectively; tsr and vph are defined in the text. (B) Disruption of the doxA, dnrV, dnrU, and dpsH genes. Gene location and transcription direction are indicated by arrows. The plasmids containing fragments of S. peucetius chromosome with disrupted genes, cloned into KC515, are shown beneath the restriction map of the genes. Dashed triangles indicate insertions of an aphII gene cloned blunt ended into the filled-in sites. (C) Plasmids carrying fragments of the S. peucetius chromosome used to complement dnrU, dnrV, and doxA mutations. Restriction site abbreviations: Aa, AatI; Ag, AgeI; B, BamHI; Ba, BalI; Bs, BspEI; Hp, HpaI; Kp, KpnI; Nc, NcoI; No, NotI; Nr, NruI; Ps, PstI; Pv, PvuII; Sa, SalI; Sp, SphI; Ss, SstI; Xh, XhoI.

For the dnrV::aphII and doxA::aphII mutants, S. peucetius 29050 was infected with phWHM353 or phWHM363, and clones resistant to neomycin and viomycin (270 from phWHM353 and 117 from phWHM363) as well as clones resistant only to neomycin (130 from phWHM353 and 42 from phWHM363) were obtained. Clones resistant only to neomycin were expected to have undergone dnrV or doxA gene replacement via double crossover recombination. Southern analysis of the genomic DNA from three clones belonging to each group was performed to confirm that homologous recombination had taken place between the cloned fragment and genomic DNA in the dnrV or doxA region. When the 1.0-kb PstI-BamHI fragment of pFDNeoS containing the aphII gene was used as a probe, a 7.0-kb BamHI fragment was detected in both cases, instead of the 6-kb BamHI fragments characteristic of the wild-type strain, as expected (data not shown).

For the dpsH::aphII mutant, S. peucetius 29050 was infected with phWHM366, and 158 clones resistant to neomycin and viomycin and 99 clones resistant only to neomycin were identified. Southern analysis of the genomic DNA of five neomycin-resistant clones, with the aphII gene as a probe, revealed a 4.5-kb BamHI-BglII fragment, which is consistent with replacement of dpsH with its disrupted copy (data not shown).

Construction of the dnrU::aphII dnrX::aphII double mutant by insert-directed homologous recombination in S. peucetius.

The WMH1650 dnrX::aphII mutant was infected with phWHM295 (Table 1), containing a disrupted copy of the dnrU gene. Six clones resistant to both neomycin and viomycin were obtained after infection, with the expectation that these clones could be produced by homologous recombination between the cloned dnrU::aphII fragment and the chromosome of the WMH1650 dnrX::aphII mutant but not the aphII segment internal to the dnrX gene. PCR analysis was used to show that recombination did not take place between the aphII genes in the host and incoming phage DNA. When the primers 5′-TTTGGATCCAGCATCACTCCGTCGTTGCT-3′ and 5′-TTTAAGCTTCTGCTTCCCCGTGAAGATCA-3′ were used with the PCR conditions described by Lomovskaya et al. (40), a 1.5-kb chromosomal fragment was amplified. The same fragment was amplified when DNA from each of the six clones resistant to neomycin and viomycin was analyzed (data not shown), strongly suggesting that these clones resulted from homologous recombination in the dnrU region and not the dnrX::aphII region. Consequently, progeny of these neomycin- and viomycin-resistant clones were analyzed to obtain clones resistant to neomycin only, produced as a result of an additional crossover in the dnrU region but not between the two aphII genes. To verify disruption of dnrU in the latter strains, representative neomycin-resistant viomycin-sensitive clones were examined by Southern analysis. When chromosomal DNA from the clones was digested with BamHI and probed with the 1.0-kb PstI-BamHI fragment containing the aphII gene, the probe hybridized to 4.3- and 7.0-kb BamHI fragments in the DNA from the dnrX::aphII dnrU::aphII double mutant (data not shown). This result is consistent with insertion of the aphII gene into both the dnrX and dnrU genes.

Construction of the dnrU, dnrV, and doxA expression plasmids.

The following plasmids, illustrated in Fig. 3C, were constructed as described in Table 1. pWHM299, pWHM385, and pWHM390 contain the dnrU, dnrV, and doxA genes, respectively, and pWHM548 contains the doxA gene cloned under the control of the strong, constitutive ermEp* promoter (10). pWHM375 and pWHM387 contain the dnrU and dnrV or the dnrV and dox genes, respectively. Each plasmid was introduced into the host strain by transformation to study complementation of the dnrU::aphII, dnrV::aphII, and doxA::aphII mutations in strains WMH1658, WMH1663, and WMH1664, respectively. The presence of the plasmids in the transformants was verified by analysis of the reisolated DNA by restriction enzyme digestion.

Determination of anthracycline production.

S. peucetius strains were cultured in APM seed and production medium as described by Furuya and Hutchinson (24). The cultures were acidified with oxalic acid, heated at 60°C for 45 min, adjusted to pH 8.5, and extracted with chloroform. The combined solvent extracts were concentrated to dryness in vacuo, and the residue was dissolved in ethyl acetate and analyzed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) according to the method described by Otten et al. (47). HPLC analysis was performed as described by Lomovskaya et al. (40) for the majority of the samples. Determination of anthracycline production in experiments that included transformants of the doxA mutant (see Fig. 7) was performed by HPLC analysis as follows. The chromatographic system included two model 510 solvent delivery systems (Waters, Milford, Mass.) controlled with the Waters Pump Control Module and Millennium Chromatography Manager. The effluent was monitored at 488 nm with a Waters 996 Photodiode Array detector. The data were stored and processed with a Waters Millennium Chromatography Manager. Chromatography was performed on a Waters Nova-Pak C18 column, 4-mm particle size (3.9 by 150 mm), equipped with a Waters Nova-Pak C18 guard column, 4-mm particle size (3.9 by 20 mm). The mobile phase A was 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA; Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, Mo.) in H2O, and mobile phase B was 0.078% TFA in acetonitrile (EM Science, Gibbstown, N.J.). Elution was performed by the following method: 20 to 25% B in A with a linear gradient for 5 min, followed by 25 to 40% B in A with gradient 8 for 15 min, followed by 40 to 70% B in A with a linear gradient for 3 min, and remaining at 70% B in A for an additional 5 min. These conditions were followed by a gradient of 70% B in A to 100% B over 4 min, followed by 100% B for 2 min and then an immediate return to the initial conditions for a 4-min reequilibration period. The flow rate during the 34-min run was 1.5 ml min−1 at room temperature.

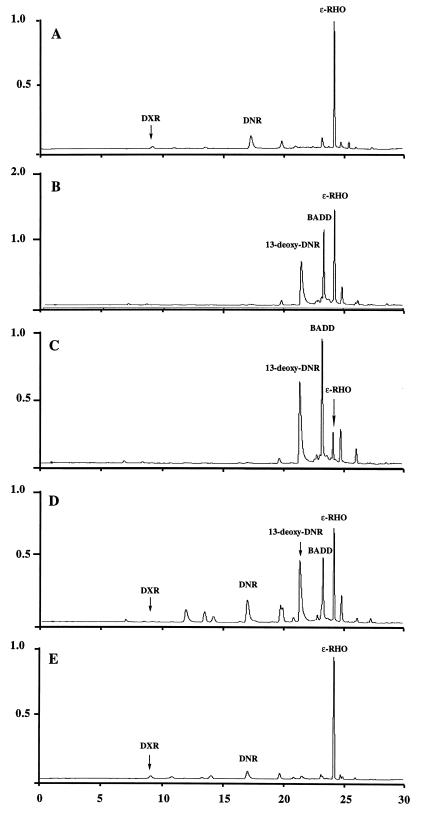

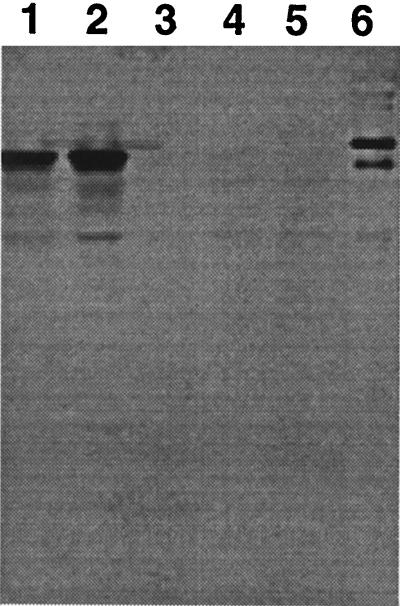

FIG. 7.

HPLC chromatograms of the ethyl acetate extract of S. peucetius 29050 (wild type) (A) and WMH1664 doxA::aphII transformed with pWHM3 (B), pWHM390 doxA (C), pWHM548 ermE*::doxA (D), or pWHM387 dnrVdoxA (E). ɛ-RHO, ɛ-rhodomycinone.

Isolation and characterization of 13-deoxy-DNR from S. peucetius.

The S. peucetius WMH1663 dnrV mutant was added to seed APM medium (12.5 ml) containing neomycin (3 μg ml−1) and incubated for 17 h. A 0.2-ml aliquot of the seed culture was transferred to each of 20 flasks containing 50 ml of APM medium with neomycin (3 μg ml−1) and incubated at 30°C for 5 days. The cultures were combined and centrifuged, and the broth was extracted with ethyl acetate (3 times, 1 liter each). The ethyl acetate-soluble fraction was evaporated under reduced pressure (<35°C) to give a residue (400 mg), which was separated by gel filtration on a Sephadex LH-20 column (1.5 by 100 cm; Pharmacia) by elution with methanol (MeOH). The material recovered in the fractions from 100 to 130 ml (186 mg) was subjected to KH2PO4-buffered silica gel column chromatography (1.0 by 50 cm) and eluted with chloroform (CHCl3)-MeOH from 1:0 to 1:1 (vol/vol). The material eluted with CHCl3-MeOH from 7:3 to 6:4 (111 mg) was passed through a Waters Sep-Pak C18 cartridge. The fraction eluting with acetonitrile (CH3CN)-H2O (35:65 [vol/vol]) was purified by reverse-phase HPLC (Waters Nova-Pak C18 column, 10 by 300 mm; flow rate, 2.5 ml/min; detection with UV at 488 nm; eluent, CH3CN-H2O [35:65; vol/vol] plus 0.1% TFA) to yield 13-deoxy-DNR (5.9 mg) as a red, amorphous residue. It had the same retention time (24.5 min) as an authentic standard obtained from Pharmacia & Upjohn, as well as the following characteristics: 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (DMSO-d6) δ 14.07 (1H, s, 6 or 11-OH), 13.28 (1H, s, 6 or 11-OH), 7.93 (1H, brdd, J = 7.0 and 3.4 Hz, C-1), 7.77 (1H, brm, C-2), 7.67 (1H, brdd, J = 5.3 and 3.4 Hz, C-3), 5.31 (1H, brs, C-7), 4.91 (1H, brt, C-1′), 4.18 (1H, brdd, C-4′), 4.15 (1H, ddd, J = 12.4, 6.0, and 2.0 Hz, C-3′), 4.10 (1H, dq, J = 6.1 and 1.5 Hz, C-4′), 3.99 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.54 (1H, brs, 9-OH), 3.17 (2H, d, J = 4.0 Hz, NH2), 2.88 (1H, d, J = 18.0 Hz, C-10a), 2.58 (1H, d, J = 18.0 Hz, C-10b), 2.10 (1H, brd, J = 14.7 Hz, C-8a), 1.95 (1H, brd, J = 14.7 Hz, C-8b), 1.69 (1H, m, C-2′), 1.50 (1H, m, C-13), 1.16 (3H, d, J = 6.1 Hz, C-6′), 1.11 (1H, t, J = 8.4 Hz, C-14); liquid chromatography-fast atom bombardment mass spectral data (LC-FABMS), m/z 514 (M + H).

13-Deoxy-DNR (5.9 mg) was dissolved in 0.1 N HCl (1 ml) and stirred at 100°C for 1 h. The mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate (3 times, 20 ml each) and washed with saturated aqueous NaCl (3 times, 20 ml each). The organic layer was evaporated under reduced pressure (<35°C). The resulting residue was chromatographed (buffered silica gel, CHCl3-MeOH from 10:0 to 9:1 [vol/vol]) to give the algycone of 13-deoxy-DNR (2.4 mg, 54.3% yield) as a red amorphous residue with the following characteristics: 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 14.01 (1H, s, 6 or 11-OH), 13.14 (1H, s, 6 or 11-OH), 7.93 (1H, brm, C-1), 7.93 (1H, brm, C-2), 7.67 (1H, brdd, C-3), 5.33 (1H, brdd, C-7), 4.00 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.00 (1H, d, J = 18.2 Hz, C-10a), 2.55 (1H, d, J = 18.2 Hz, C-10b), 2.07 (1H, dd, J = 13.0 and 2.1 Hz, C-8a), 1.79 (1H, dd, J = 13.0 and 5.2 Hz, C-8b), 1.58 (1H, m, C-13), 1.24 (1H, brt, C-14). (CDCl3) δ 13.73 (1H, s, 6 or 11-OH), 13.22 (1H, s, 6 or 11-OH), 8.05 (1H, d, J = 7.5 Hz, C-1), 7.79 (1H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, C-2), 7.39 (1H d, J = 7.5 Hz, C-3), 5.30 (1H, brs, C-7), 4.73 (1H, brs, 9-OH), 4.09 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.20 (1H, d, J = 18.7 Hz, C-10a), 2.57 (1H, d, J = 18.7 Hz, C-10b), 2.35 (1H, dd, J = 14.9 and 3.1 Hz, C-8a), 1.86 (1H, brd, J = 14.9 Hz, C-8b), 1.74 (1H, m, C-13), 1.10 (1H, t, J = 6.2 Hz, C-14); electron impact mass spectrum (EIMS), m/z 384 (M+); high-resolution EIMS, found m/z 384.1180 [calculated for C21H20O7 (M+): 384.1209].

Western immunoblot analysis of doxA expression in S. peucetius.

Wild-type strain 29050 and the WMH1663 dnrV and WMH1662 dnrX dnrU mutant strains were grown for 96 h in APM medium, in duplicate. One culture was used to prepare an extract for HPLC analysis, and the other flask was used to prepare a protein extract. After two washes with phosphate-buffered saline (50) plus 10 mM EDTA, the mycelium was resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline plus 10 mM EDTA plus 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Sigma) to a final concentration of 500 mg (wet weight) ml−1. The suspension was sonicated (three cycles of 1 min each at 15-s intervals; Sonicator MS-50; Heat Systems Ultrasonics, Farmingdale, N.Y.) and centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 15 min (Heraeus microcentrifuge) to obtain a cell-free supernatant fraction and the cell debris as a pellet. Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed according to the method of Laemmli (35). For Western blotting, the supernatant and pellet fractions were suspended in SDS-PAGE sample buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 100 mM dithiothreitol, 2% SDS [wt/vol], 0.1% bromophenol blue [wt/vol], and 10% glycerol [vol/vol]) and heated in boiling water for 3 min, and then the supernatant material from each sample was run on an SDS–12.5% PAGE gel to separate the proteins. The proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond ECL; Amersham, Chicago, Ill.) by using a Bio-Rad electroblotting apparatus (Richmond, Calif.). The immunodetection assay was done with an ECL kit as instructed by the manufacturer (Amersham). Antiserum to DoxA was raised in rabbits by injection with purified DoxA obtained from cell extracts of an E. coli strain bearing the doxA gene cloned into pET-14b (Novagen, Madison, Wis.). A goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G horseradish peroxidase conjugate was used as the secondary antibody.

Bioconversion of DNR to DXR in S. peucetius WMH1530 and S. lividans.

The experiments conducted at the University of Wisconsin were performed by the method described previously (46, 47) with GPS medium (15). The experiments conducted at Pharmacia & Upjohn were done as follows. A seed culture was grown in liquid R2YE medium (30) containing 20 μg of thiostrepton per ml. After 2 days of growth at 30°C and 280 rpm, 2.5 ml of this culture was transferred to 25 ml of the GMS production medium ([grams/liter] glucose, 5; saccharose, 40; soybean meal, 25; CaCO3, 3; NaCl, 2.7) containing 20 μg of thiostrepton per ml. Cultures were grown in Erlenmeyer flasks on a rotary shaker at 280 rpm and 30°C for 72 h, after which DNR (10 mg/ml in a water solution) was added to 10 ml of the cultures to give a final concentration of 200 μg/ml. After 2 days of further incubation on a shaker at 25°C, the cultures were extracted with 10 ml of acetonitrile-methanol (1:1 [vol/vol]) at 30°C for 30 min on a rotary shaker at 280 rpm. The extract was filtered, and the filtrate was analyzed by HPLC as previously described (46).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence reported here has been deposited at GenBank/EMBL with accession no. U77891.

RESULTS

Production of DXR by S. peucetius ATCC 29050.

The DXR producer S. peucetius var. caesius ATCC 27952 (7) was derived by mutagenesis of S. peucetius ATCC 29050, and anthracycline production was originally assayed under conditions that led to the belief that strain 29050 does not produce DXR (5, 7, 26). However, several years ago we found that strain 29050 does in fact produce significant quantities of DXR when it is grown in highly-buffered APM medium as described in Materials and Methods. Characterization of the isolated material identified as DXR by its chromatographic behavior in 300 MHz 1H NMR spectroscopy showed that the spectrum of the sample was identical to that of authentic DXR (data not shown). This result gave us confidence that the DNR C-14 hydroxylase gene would be found in strain 29050.

Sequence analysis of a 3.9-kb DNA fragment containing the doxA, dnrV, dnrU, and dpsG genes plus the 5′ end of the dpsH gene.

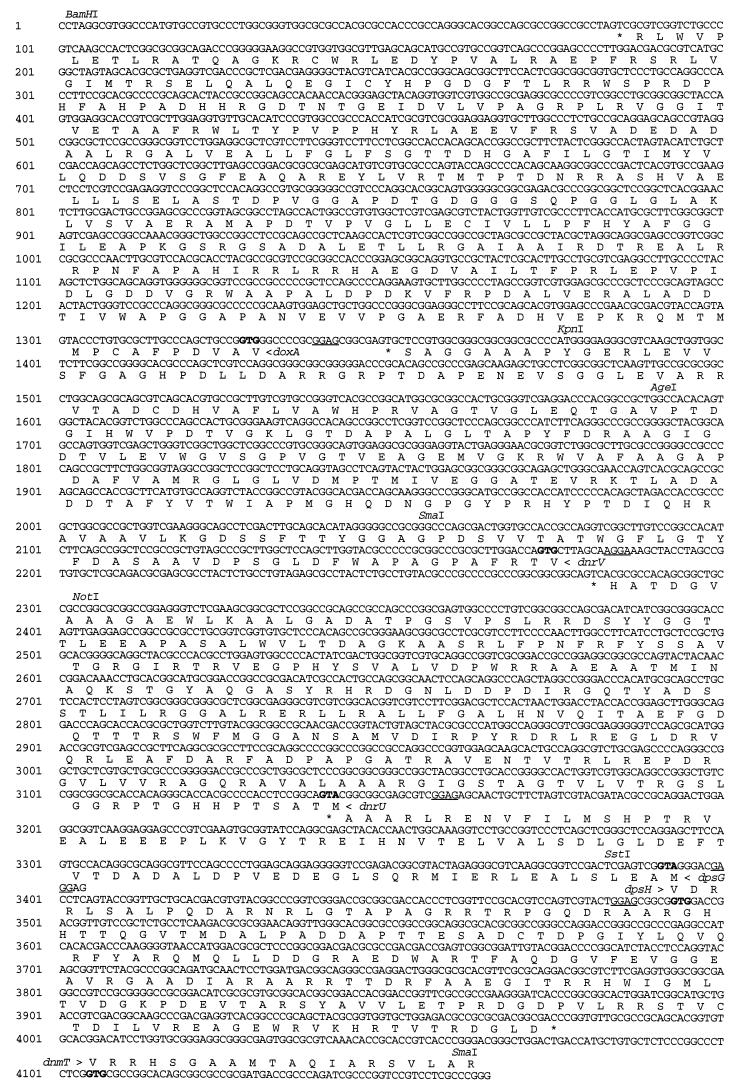

DNA sequencing of both strands of a 3,898-nucleotide (nt) fragment (Fig. 4), obtained from cosmid clones bearing the relevant genes (47, 56), was carried out with DNA fragments subcloned in M13 vectors (61) as previously described (46). The open reading frames (ORFs) were assigned based on the distinctive codon usage and third-position G+C bias characteristic of Streptomyces genes by using the CODONPREFERENCE program (17). This analysis revealed four complete ORFs (doxA, dnrV, dnrU, and dpsG) (Fig. 2) and one partial ORF (dpsH), the C-terminal end of which extends 179 nt into the adjacent DNA fragment (52). Homologues of these ORFs have been reported from the DNR gene cluster of Streptomyces sp. strain C5 (18, 20), a non-DXR-producing strain.

FIG. 4.

DNA sequence of the region containing the doxA, dnrV, dnrU, dpsG, and dpsH genes. The proposed translational start sites of the ORFs are shown in boldfaced type, and putative RBS are underlined. Stop codons are indicated with an asterisk. Amino acid translations are shown for the doxA, dnrV, dnrU, dpsG, and dpsH gene products and the N terminus of the dnmT gene product (52).

The doxA gene encodes a CY P-450.

A probable start codon (GTG) for doxA is located at nt 1330 and is preceded by a potential ribosome binding site (RBS), GAGG, at nt 1342. A stop codon (TGA) is located at nt 83; thus, a DoxA polypeptide having 414 amino acid residues and an Mr of 44,964 (excluding the fMet residue at the N terminus) would be encoded. A database search with the TFASTA and FASTA programs (11) identified many CY P-450s having a strong similarity to the deduced product of doxA, in particular its Streptomyces sp. strain C5 homolog (18) and three closely related proteins from Saccharopolyspora erythraea; EryF, the 6-deoxyerythronolide B hydroxylase (60); EryK, the erythromycin D hydroxylase (54); and Ery-Orf405, the major CY P-450 of S. erythraea (3). DoxA contains a sequence, FGDGPHYCIG, near the C-terminal end of the protein that matches the CY P-450 consensus se-quence, F-(SGNH)-X-(GD)-X-(RHPT)-X-C-(LIVMFAP)-(GAD) (PROSITE release 13.0) (8). This region contains the highly conserved heme binding site, including the essential cysteine residue (boldface) which serves as the heme iron ligand. The (GA)-G-X-(DE)-T motif associated with the oxygen binding site (48) is also strongly conserved as AGHDT in DoxA.

Characterization of the deduced products of dnrV, dnrU, and dpsH.

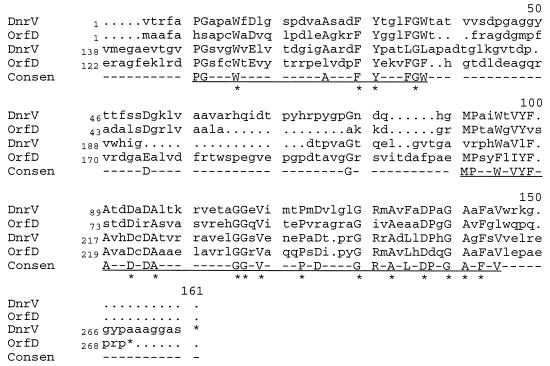

The dnrV gene (synonymous with dauV in Streptomyces sp. strain C5 [18]) has a probable start codon (GTG) at nt 2175 and a TAG stop codon at position 1348, indicating that dnrV would encode a polypeptide composed of 274 amino acid residues with an Mr of 28,349 (excluding the fMet residue at the N terminus). The predicted start codon of dnrV is preceded by a probable RBS (AGGA) at position 2186. Analysis of the deduced product of dnrV with the tBLASTn program (2) identified several peptides with considerable sequence similarity, besides the Streptomyces sp. strain C5 homolog DauV (94% identical). Among these, OrfD (58) and SgaA (4) from streptomycin-producing Streptomyces griseus are 54 and 50% similar, respectively. Neither of the latter genes provides insight into the function of dnrV. ORFD is a gene of unknown function located immediately upstream from the afsK gene encoding a serine or threonine protein kinase (58); sgaA suppresses the growth disturbance caused by high osmolarity and a high concentration of A factor during early growth (4). The exact functions of these two genes are not understood, however. An interesting characteristic of the DnrV polypeptide is that the N-terminal half (residues 1 to 137) and the C-terminal half (residues 138 to 275) possess significant sequence similarity (38% identity). OrfD shares this property, but to a lesser degree (28% identity). PILEUP (17) analysis of the N-terminal and C-terminal portions of both DnrV and OrfD revealed two conserved regions (underlined in Fig. 5) separated by a variable region. A similar comparison was not done for SgaA.

FIG. 5.

PILEUP analysis of the DnrV protein. Comparison of the N-terminal and C-terminal portions of DnrV and OrfD. Numbers represent the positions in the sequence. Two conserved regions are underlined, and highly conserved residues are marked by asterisks.

A likely start codon (ATG) for dnrU (synonymous with dauU in Streptomyces sp. strain C5 [18]) is located at nt 3142 and is preceded by a probable RBS (GAGG) at nt 1360. A TGA stop codon at nt 2279 would produce a polypeptide having 286 amino acid residues and an Mr of 30,500 (excluding the fMet residue at the N terminus). Database comparisons of the deduced product of dnrU performed by using the TFASTA/FASTA and tBLASTn programs revealed similarity to the N-terminal end of polyketide synthase ketoreductases, such as ActIII (29) and AknIII (57), that catalyze the reduction of the polyketide chain at the position corresponding to C-9 of the DNR decaketide (Fig. 1). Similarities extending throughout the length of the polypeptide were observed with an oxidoreductase of unknown function (ORF4) (63) from Streptomyces antibioticus and its closely related homologue from the S. lividans transposon Tn4811 (12) and with oxidoreductases from plants, including a pod-specific dehydrogenase from Brassica napus (13) and protochlorophyllide reductases such as PCR from barley (51). The Streptomyces sp. strain C5 ORF1 (dauU) gene was predicted to encode a protein that lacks the first 92 residues of DnrU (18); the remainder of ORF1 lies in the upstream region sequenced (20), which when joined into a complete ORF should give a protein that is 96% identical to DnrU. Since the dpsE and dnrE (dauE) gene products carry out the reductions at C-9 of the DNR decaketide and at C-7 of aklaviketone, respectively (20, 27), a likely function for the DnrU ketoreductase is the formation of the 13-dihydro-DNR and related derivatives commonly found in S. peucetius fermentations.

The first start codon (GTG) for dpsH is present at nt 3493 and is preceded by a probable RBS (GGAG) at nt 3484. The TGA stop codon at 4077, obtained from sequence data reported elsewhere (52), would result in a polypeptide having 193 amino acid residues and an Mr of 21,352 (excluding the fMet residue at the N terminus). In addition to the high identity to its Streptomyces sp. strain C5 homolog dauZ (18, 20), the deduced product of dpsH resembles gene products of unknown function associated with gene clusters for the production of the following polyketide metabolites [name]: OrfX from Streptomyces roseofulvus [frenolicin] (9) (59% similar), ActVI-OrfA from S. coelicolor [actinorhodin] (21) (57% similar), Orf1 from Saccharopolyspora hirsuta [spore pigment] (36) (55% similar), and MtmX from Streptomyces argillaceus (37) [mithramycin] (60% similar).

The dpsG gene encodes an acyl carrier protein.

The dpsG gene has a start site (ATG) at nt 3393 and a stop codon (TGA) at nt 3139 and would thus encode a product having 83 amino acid residues and an Mr of 9,305. The deduced product of dpsG exhibits significant similarity and good end-to-end alignment with acyl carrier proteins (ACPs) from many polyketide synthase (PKS) gene clusters, including DpsG from Streptomyces sp. strain C5 (98% identity by GAP analysis [17]) (20), Orf6 from S. hirsuta (45% identity) (36), and the ACP from Streptomyces violaceoruber (45% identity) (53). The location of the dpsG gene, 9.4 kb upstream of the polyketide β-ketoacyl:ACP synthase (KS) genes, dpsA and dpsB (27, 62), is very unusual, since the ACP genes of type II polyketide synthases typically are found immediately downstream of the KSβ subunit gene (31, 32), with the exception of the closely related dpsG gene from Streptomyces sp. strain C5 (20). However, heterologous expression of the dpsG gene along with the PKS region genes (dpsF-dpsD [Fig. 2]) in S. lividans (27, 49) has shown that dpsG is required for the formation of 12-deoxyaklanonic acid, the first isolatable intermediate of the DNR pathway. These results, along with the sequence homology between DpsG and ACPs from other PKS gene clusters, provide convincing evidence that dpsG functions as the ACP for the DXR gene cluster in spite of its unconventional location.

Effect of insertional inactivation of dnrU.

To examine the function of dnrU, the wild-type gene in strain 29050 was replaced with a mutant copy resulting from insert-directed homologous recombination of DNA carrying an antibiotic resistance gene. The phWHM295 (Table 1) recombinant derivative of KC515 (11) (all KC515 clones in this study are prefixed with ph) was made (as described in Materials and Methods) by transfer of a ca.-4-kb segment from pWHM294 (Fig. 3B) that carried a disrupted copy of dnrU containing the aphII gene (Table 1) inserted at the internal BamHI site. After infection of S. peucetius 29050 with phWHM295, clones resistant to neomycin and viomycin or only to neomycin were identified by methods previously used for gene disruption or replacement experiments with Streptomyces hygroscopicus (39) and the S. peucetius dnrX and dpsY genes (40). A large proportion of the clones were resistant only to neomycin (44 of 148 recombinants examined), suggesting that many of the recombinants had resulted from double-crossover events. The neomycin-resistant WMH1658 strain was chosen as representative of clones with a disrupted dnrU gene. Southern analysis of the BamHI-digested DNA from this clone upon probing with the 1.0-kb PstI-BamHI fragment of pFDNeoS (16) containing the aphII gene revealed a 7.0-kb BamHI fragment in place of the 6-kb BamHI fragment of strain 29050. This result established the presence of disrupted copy of the dnrU gene in the chromosome of strain WMH1658 (data not shown). S. peucetius 29050 and WMH1658 were grown under standard conditions for antibiotic production in APM medium (Materials and Methods), and the culture extracts were analyzed by HPLC. The resulting data indicated that the amounts of DXR and RHO increased about 3.4 and 5.8 times, respectively, in strain WMH1658 over the amounts of these metabolites produced by the control strain, 29050 (Table 2). As reported previously (40), DXR production was also increased considerably in the WMH1650 dnrX::aphII mutant strain, which produced approximately three times more DXR than strain 29050 and no detectable RHO (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Anthracycline titers of S. peucetius 29050 (wild type), WMH1658 dnrU::aphII, WMH1650 dnrX::aphII, and WMH1662 dnrX::aphII dnrU::aphII

| Strain | Titer (μg/ml)a for indicated compound

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RHO | 13-Dihydro-DNRb | DNR | DXR | |

| 29050 | 12 | 0 | 30 | 14 |

| WMH1658 dnrU::aphII | 69 | 0 | 16 | 47 |

| WMH1650 dnrX::aphII | 0c | 11 | 31 | 41 |

| WMH1662 dnrX::aphII dnrU::aphII | 5 | 0 | 14 | 94 |

Cultures were grown in APM medium for 120 h and worked up as described in Materials and Methods. The values are typical of those obtained in different fermentations.

The reference material is the 13S isomer.

No metabolite was found.

Construction and anthracycline production by dnrX dnrU double and dnrX dnrU dnrH triple mutants.

Since we have shown that dnrH (52) and dnrX (40) mutants also display increased DNR or DXR production, we determined the effect of combining these mutations with the dnrU::aphII mutation in a single background. An S. peucetius dnrU dnrX double mutant (WMH1662) was constructed as described in Materials and Methods, and the metabolite profile of this strain was determined. Culture extracts of WMH1662 were analyzed by HPLC analysis along with extracts from the WMH1650 dnrX::aphII and WMH1658 dnrU::aphII mutants and the wild-type S. peucetius 29050. About twice as much DXR was produced by the WMH1662 double mutant as was made by the WMH1650 and WMH1658 single mutants (Table 2), indicating that the dnrX and dnrU mutations have an additive effect on DXR production. As expected, the double mutant produced only a small amount of RHO compared with the 29050 or dnrU::aphII mutant strains (Table 2). The double mutant also lost the ability to produce (13S)-13-dihydro-DNR [this compound should be the 13S isomer, since that isomer was used as the HPLC standard; a definitive conclusion will require a sample of the (13R)-13-dihydro-DNR isomer for comparison], supporting our belief that DnrU is responsible for reduction of the carbonyl group at position 13 in DNR or its immediate precursor(s). When strain WMH1662 was grown in a medium optimized for anthracycline metabolite production, the DXR titer was also increased (approximately twofold greater than the value shown in Table 2) compared with the values observed for the dnrX and dnrU single mutants (22). Furthermore, a dnrU mutant of a DNR-overproducing strain that does not produce the baumycins, a group of metabolites that can be converted to DNR upon acid treatment (as summarized in reference 55), produced a much larger amount of DXR in the optimized medium than did the dnrU+ parental strain (22). This mutant, like WMH1662, also exhibited a notable decrease in DNR titer and produced up to five times less 13-dihydro-DNR than its dnrU+ parent (22).

The dnrX::aphII dnrU::aphII dnrH::aac(3)IV triple mutant strains, WMH1667 and WMH1668 (Table 1), were constructed according to the method of Scotti and Hutchinson (52). This method involved disrupting the dnrH gene in the WMH1662 dnrX::aphII dnrU::aphII double mutant with the pWHM959 plasmid (52) bearing an internal 0.4-kb segment of dnrH cloned into a temperature-sensitive plasmid vector carrying the aac(3)IV apramycin resistance gene. Apramycin-resistant transformants were isolated as described previously (52), and the genotype of three independent recombinant strains was verified by Southern analysis. When grown in a medium optimized for anthracycline production, the WMH1667 and WMH1668 mutants produced 3.4 to 3.8 times more DXR than the WMH1662 double mutant (data not shown). Neither 13-Deoxy-DNR nor 13-dihydro-DNR was produced.

Effect of insertional inactivation of dnrV and doxA.

To assess the importance of dnrV for DXR production, the chromosomal dnrV and doxA genes were each replaced with mutant alleles containing a drug resistance gene, as described in Materials and Methods. The neomycin-resistant strain WMH1663 was chosen as representative of clones with a mutant dnrV gene and strains WMH1664 and WMH1665 were chosen as representative of clones with a mutant doxA gene for metabolite profile determinations. HPLC analysis of culture extracts of the WMH1663 dnrV::aphII mutant showed that the strain did not produce DXR, whereas a significant amount of 13-deoxy-DNR and a small amount of 13-dihydro-DNR were identified (these latter two metabolites are not usually produced by the wild-type strain) (Table 3). RHO was produced at nearly the same level by strains 29050 and WMH1663. The WMH1664 and WMH1665 doxA::aphII mutants produced 13-deoxy-DNR as the principal metabolite and a higher level of RHO than strain 29050 but no DNR, DXR, or 13-dihydro-DNR (Table 3). They also produced bis-anhydro-13-deoxydaunomycinone (BADD), as characterized by UV and electrospray mass spectral analysis of the corresponding HPLC peak (see Fig. 7B). The latter metabolite is a shunt product reported to be derived nonenzymatically from 13-deoxy-DNR (19). These results confirm the dual role of DoxA described by Strohl and coworkers (19, 20), C-13 oxidation of 13-deoxy-DNR and C-14 hydroxylation of DNR. On this basis, the dnrV::aphII mutant appears to be a leaky doxA mutant, even though Western analysis of the WMH1663 cell extract with a DoxA-specific polyclonal antiserum failed to show a detectable level of the DoxA protein compared with the amounts seen in strains 29050 and WMH1662 (Fig. 6).

TABLE 3.

Anthracycline titers of S. peucetius 29050 (wild type), WMH1663 dnrV::aphII, and WMH1665 doxA::aphII

| Strain | Titer (μg/ml)a for indicated compound

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RHO | 13-Deoxy-DNRb | 13-Dihydro-DNR | DNR | DXR | |

| 29050 | 8 | 0c | 0 | 20 | 9 |

| WMH1663 dnrV::aphII | 9 | 41 | 6 | 6 | 0 |

| WMH1665 doxA::aphII | 18 | 58 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

a–c See footnotes to Table 2.

FIG. 6.

Analysis for the presence of the DoxA protein in cell extracts of different S. peucetius strains by Western immunoblotting. Lanes: 1, ATCC 29050 wild-type strain; 2, WMH1662 dnrX::aphII dnrU::aphII double mutant; 3, molecular weight standards (not visible); 4, WMH1663 dnrV::aphII mutant; 5, independent clone of strain WMH1663; 6, DoxA fusion protein used to prepare the DoxA antiserum.

Expression of the dnrU, dnrV, and doxA genes in S. peucetius mutant strains.

Complementation experiments were carried out with representative dnrU, dnrV, and doxA mutants to gain further support for our deductions about the role of each gene. To confirm that the increased production of RHO and DXR by the dnrU::aphII mutant was due only to dnrU disruption, the WMH1658 dnrU::aphII mutant was transformed with pWHM299 containing the dnrU gene (Fig. 3C). WMH1658 was also transformed separately with pWHM375 bearing the dnrU and dnrV genes and pWHM385 containing only the dnrV gene (Fig. 3C) to study the possibility of a polar effect of the dnrU mutation on expression of dnrV and doxA. HPLC analysis of culture extracts showed a decrease in the amount of RHO and DXR produced by strains WMH1658(pWHM299) and WMH1658(pWHM375), containing the dnrU gene only and both the dnrU and dnrV genes, respectively, compared with the amounts of these metabolites produced by the WMH1658(pWHM3) transformants carrying only the plasmid vector (data not shown). The resulting phenotype of these transformants was similar to that of the wild-type strain with respect to the amounts of RHO, DNR, and DXR produced and clearly different from the phenotypes of dnrV and doxA mutants. Introduction of pWHM385 containing only the dnrV gene did not change the phenotype of the WMH1658 mutant.

The ability of the wild-type dnrV gene to complement the dnrV::aphII mutation was tested in WMH1663. pWHM385 containing the dnrV gene and the pWHM3 plasmid vector as a control were introduced separately into the WMH1663 strain, and culture extracts from three transformants of each variant were analyzed by HPLC. pWHM385 did not restore DXR production, and significant amounts of 13-deoxy-DNR and 13-dihydro-DNR were produced (Table 4). The same results were obtained when pWHM390 (Fig. 3C), containing the doxA gene, was used for transformation of WMH1663 (Table 4). On the other hand, the dnrV mutation was complemented when pWHM387, containing the dnrV and doxA genes (Fig. 3C), was introduced into strain WMH1663. The amounts of RHO, DNR, and DXR produced by WMH1663(pWHM387) transformants were similar to those observed for the wild-type strain, and the transformed strain did not produce 13-deoxy-DNR or 13-dihydro-DNR (Table 4). Since the wild-type phenotype was restored only if both dnrV and doxA were introduced into the dnrV mutant, it appears that the dnrV::aphII mutation had a polar effect on doxA expression. Hence, dnrV and doxA appear to belong to one operon that, in light of the data shown in Table 2, does not include the dnrU gene.

TABLE 4.

Anthracycline titers of S. peucetius WMH1663 dnrV::aphII and WMH1664 doxA::aphII mutants transformed with pWHM3, pWHM355, pWHM360, or pWHM357a

| Strain | Titer (μg/ml)a for indicated compound

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RHO | 13-Deoxy-DNRb | 13-Dihydro-DNR | DNR | DXR | |

| WMH1663(pWHM3) | 14 | 38 | 10 | 7 | 0 |

| WMH1663(pWHM385) dnrV | 12 | 50 | 11 | 10 | 0 |

| WMH1663(pWHM390) doxA | 15 | 56 | 11 | 8 | 0 |

| WMH1663(pWHM387) dnrVdoxA | 31 | 0c | 0 | 44 | 22 |

| WMH1664(pWHM3) | 18 | 98 | 0 | 0 | 2d |

| WMH1664(pWHM390) doxA | 8 | 36 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| WMH1664(pWHM387) dnrVdoxA | 67 | 0c | 7 | 54 | 30 |

See footnote a in Table 2. The titers shown are the average values obtained from three independent fermentations.

The reference material is the 13S isomer.

No metabolite was found.

This value was not confirmed by isolation and characterization and thus may not be valid.

Complementation of the doxA::aphII mutation in WMH1664 was studied with plasmids containing doxA alone or the dnrV and doxA genes. Only pWHM387 with the doxA and dnrV genes together restored the wild-type phenotype (Table 4 and Fig. 7E). This observation suggests that these two genes must be expressed in cis (this conclusion is confirmed by results shown in Table 4 for the dnrV::aphII mutant). Unexpectedly, introduction of pWHM390 with only the doxA gene into WMH1664 gave a phenotype similar to that of the doxA::aphII mutant (Table 4 and Fig. 7C). To determine if the latter observation was due to lack of adequate doxA expression, doxA was subcloned under the control of the strong, constitutive ermEp* promoter (10) as pWHM548 (Fig. 3C), and then pWHM548 was introduced into strain WMH1664. Culture extracts from the resulting transformants were analyzed by HPLC compared with transformants carrying pWHM3, pWHM390, and pWHM387 (Fig. 7). The presence of DNR and DXR was observed together with 13-deoxy-DNR and BADD in transformants carrying pWHM548 (Fig. 7D). Consequently, overexpression of the doxA gene did not restore the wild-type behavior to the WMH1664 doxA::aphII mutant but resulted in the accumulation of 13-deoxy-DNR (and some other, unidentified metabolites) instead of its disappearance by conversion to DNR and thence to DXR.

Bioconversion experiments with the dnrV and doxA genes.

The possibility that dnrV and doxA act jointly in DNR and DXR biosynthesis was examined further by bioconversion experiments. A 3.7-kb SstI fragment containing the doxA, dnrV, and dnrU genes was subcloned on the high-copy-number vector pWHM3 as pWHM546 (Table 1) and then analyzed for its ability to bioconvert DNR to DXR in the S. peucetius dnrN::aphII mutant strain WMH1530 (46). Since the regulatory dnrN gene has been inactivated in WHM1530, this strain does not accumulate DNR, DXR, or any pathway intermediates, and it does not bioconvert any of these intermediates to DXR (46). Bioconversion experiments were conducted as previously described (46, 47), as well as independently under similar conditions with both the WMH1530 and the S. lividans TK23 (30) host strains (Materials and Methods). The results shown in Table 5, obtained with two different growth media, demonstrate that transformants carrying pWHM546 converted exogenous DNR to DXR. Further subcloning from pWHM546 yielded a 2.3-kb NotI-BamHI fragment containing doxA and dnrV and a small portion of the 3′ end of dnrU (Fig. 4), as pWHM547 (Table 1), as well as pWHM548 containing the doxA gene (described above); in both cases, expression of the cloned genes is under the control of the ermEp* promoter. Transformants of WMH1530 containing pWHM547 also converted DNR to DXR, but the bioconversions by the transformants containing pWHM548 gave much lower levels of DXR. These results also support the belief that dnrV and doxA act jointly. Parallel work performed industrially (33) resulted in the construction of a recombinant vector containing the doxA and dnrV genes (these genes were obtained from a mutant derived from S. peucetius ATCC 27952) that was able to bioconvert 80% of the DNR (present at 1 mg/ml) to DXR in an S. lividans recombinant that also carried the drrA and drrB DNR and DXR resistance genes (28).

TABLE 5.

Bioconversion of DNR to DXR in the S. peucetius WMH1530 dnrN::aphII mutant and S. lividans TK23 transformed with pWHM546, pWHM547, pWHM548, or pWHM550

| Medium | Plasmid | DNR added (μg/ml) | DXR produced (μg/ml)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| GMSa | pWHM546 dnrUdnrVdoxA | 20 | 5 |

| pWHM547 ermE*::dnrVdoxA | 20 | 20 | |

| 100 | 50 | ||

| 200 | 142c | ||

| pWHM548 ermE*::doxA | 100 | 5 | |

| GPSd | pWHM546 | 20 | 1.5 |

| pWHM547 | 20 | 3 | |

| pWHM548 | 20 | <1 |

The host strain was S. peucetius WMH1530, and all strains were grown in the GMS medium (Materials and Methods). This work was performed at Pharmacia & Upjohn.

The data are the average values of two or three independent fermentations.

The host strain was S. lividans TK23, and work was performed at Pharmacia & Upjohn.

The host strain was S. peucetius WMH1530, and all strains were grown in GPS medium (Materials and Methods). This work was performed at the University of Wisconsin.

Effect of insertional inactivation of dpsH.

Gerlitz et al. (25) have suggested that DpsH is a type of polyketide cyclase. Their conclusion rests on the ability of the dpsH gene, when present in a cassette of heterologous type II PKS genes and expressed in S. lividans, to favor production of the tricyclic aklanonic acid instead of a monocyclic shunt product derived from an aklanonic acid precursor and formed in the absence of dpsH (25). Since it is possible that the dpsH gene behaved abnormally in the heterologous situation, we constructed a dpsH mutant (see Materials and Methods) to assess the importance of the dpsH gene for DXR production in the S. peucetius background. WMH1666 was chosen as a representative dpsH::aphII mutant and found to accumulate a significant amount of RHO but no DNR or DXR by TLC and HPLC analysis (data not shown). Since RHO still was produced, DpsH is either not an essential component of the DNR/DXR PKS or the dpsH mutation is suppressed by another locus among the three other clusters of type II polyketide biosynthesis genes in S. peucetius (56). The lack of DNR and DXR production is consistent with a polar effect of the dpsH::aphII mutation on expression of the dnmT gene immediately downstream of dpsH (Fig. 2), because dnmT is essential for the biosynthesis of the deoxysugar portion of DNR and DXR (52).

An extensive study of the complementation of the dpsH::aphII mutation was carried out in which dpsH or dnmT alone, dpsH plus dnmT, dnmT plus dnrH, or dpsH plus dnmT plus dnrH were introduced into strain WMH1666 in separate experiments. However, the collective results do not permit us to reach an unambiguous conclusion about the role of the dpsH gene, although they hint at the possibility that dpsH is involved in daunosamine biosynthesis or its attachment to RHO.

DISCUSSION

Current production of DXR is over 225 kg annually because it is widely used as an antitumor drug and is the starting point for the synthesis of numerous analogs and derivatives (6) aimed at improving clinical cancer treatment with this broad-spectrum antitumor drug. Although DXR was discovered as a metabolite of S. peucetius ATCC 27952, it is produced commercially by semisynthesis from DNR instead of by fermentation. DNR-overproducing strains are available worldwide, but they apparently lack the ability to make useful amounts of DXR. The reason(s) for this is not known, and, consequently, the information we report here about the effect of the dnrX and dnrU mutations on anthracycline metabolite production by the wild-type strain ATCC 29050 should enable the engineering of commercially useful DXR-overproducing strains.

Dickens et al. (19) have shown in vivo and in vitro that the DoxA CY P-450 enzyme catalyzes the oxidation of 13-deoxycarminomycin and 13-deoxy-DNR to their 13-dihydro forms (Fig. 1) and the subsequent oxidation of either of these 13-dihydro anthracyclines to carminomycin or DNR, respectively. (Two routes from 13-deoxycarminomycin to DNR are shown in Fig. 1 because the available data do not show which route is preferred in vivo.) DXR is produced by a comparatively slower C-14 hydroxylation of DNR, whereas carminomycin is not a substrate for C-14 hydroxylation. Cell extracts of a recombinant S. lividans strain that overproduced DoxA required oxygen and an NADPH source for all three oxidation steps. By analogy to other bacterial CY P-450 enzymes (44), a ferredoxin and NADPH:ferredoxin oxidoreductase also are required for hydroxylase activity, although genes for either type of protein are not present in the well-characterized DNR-DXR gene clusters (19) (Fig. 2). The accumulation of 13-deoxy-DNR and 13-dihydro-DNR by the WMH1663 dnrV mutant and that of 13-deoxy-DNR by the WMH1665 doxA mutant (Table 3 and Fig. 7) support the findings of Dickens et al. (19), obtained by expression of doxA in S. lividans. However, the wild-type phenotype was regained by the WMH1664 doxA mutant only when it was transformed with a plasmid bearing dnrV and doxA (Table 4 and Fig. 7E). Introduction of doxA alone resulted in a decrease in the level of 13-deoxy-DNR and the formation of small amounts of 13-dihydro-DNR, DNR, and DXR (Table 4). Overexpression of doxA with the strong, constitutive ermEp* promoter increased the amount of DNR and decreased the amount of BADD relative to that of 13-deoxy-DNR (Fig. 7D), but DXR production was not much higher than that observed in the wild-type or WMH1664 (dnrV+ doxA+) strains (Fig. 7A and E, respectively). This latter set of observations may mean that in the presence of an elevated DoxA level, insufficient DnrV, ferredoxin, or NADPH:ferredoxin oxidoreductase activity was present in vivo.

These observations led us to conclude that the dnrV and doxA genes (and perhaps also the DnrV and DoxA proteins) act jointly in the conversion of 13-deoxycarminomycin and 13-deoxy-DNR to DXR. This idea is supported by two other sets of results. Restoration of the wild-type phenotype to the WMH1663 dnrV mutant required the introduction of both dnrV and doxA; doxA alone had no effect (Tables 3 and 4). Optimal biotransformation of DNR to DXR by S. peucetius WMH1530 and S. lividans strains was generally observed when both the dnrV and doxA genes were present (Table 5). Our data, however, do not allow us to offer an explanation for the exact function of DnrV. Since it does not have a significant resemblance to known bacterial ferredoxins or NADPH:ferredoxin oxidoreductases, it is unlikely to be an electron transport protein. Furthermore, Strohl and coworkers have purified DoxA to homogeneity and found that it converts 13-deoxy-DNR to 13-dihydro-DNR and thence to DNR, as well as DNR to DXR, in vitro in the presence of only NADPH and suitable electron transport proteins. The relative rates of these conversions show that the C-14 hydroxylation of DNR is 3 orders of magnitude slower than the other oxidation steps (59a).

The role of dnrU in DNR and DXR production has also not been fully explained by our data. A strong similarity between DnrU and known ketoreductases and the partial to complete disappearance of 13-dihydro-DNR from culture extracts of dnrU mutants support the conclusion that DnrU catalyzes reduction of the 13-carbonyl in DNR and DXR or their precursors. An additional reason for this belief is the fact that dnrU and dnrX dnrU mutants are not defective in the only other ketoreductions that take place in the DXR pathway (Fig. 1), which involve the dpsE (27, 43, 62) and dnrE (synonymous with dauE in Streptomyces sp. strain C5) (20) gene products, because dnrU mutants still produce RHO and its derived glycosides. Considering the fact that 13-dihydrocarminomycin and -DNR can have two absolute stereochemistries at position 13, one stereochemical form might be established by the activity of DoxA and the opposite by DnrU, or both these enzymes might produce the same absolute stereochemistry at C-13. Until this issue is clarified by determination of the C-13 stereochemistry of 13-dihydro-DNR isolated from a dnrU+ strain and a dnrU mutant [the (13S)-13-dihydro-DNR reference standard used herein was isolated from an S. peucetius blocked mutant; it is also produced in S. lividans by bioconversion of DNR (22)] or obtained as the product of DoxA activity in vitro, we will not know if the changes in 13-dihydro-DNR levels given in Tables 2 to 4 are due solely to the action of DnrU or DoxA or to a S. peucetius ketoreductase other than DpsE and DnrE. The latter possibility must be considered because a dnrU mutant of a DNR-overproducing strain of S. peucetius still makes 13-dihydro-DNR, albeit at a much lower level than its dnrU+ parent (22). Regardless, the data in Table 2 that show a strong, positive effect of the dnrU mutation on DXR titers, particularly in the dnrX mutant background, certainly are consistent with the belief that a major effect of DnrU is to reduce the 13-carbonyl in DNR and/or DXR. Lack of DnrU, therefore, could avoid diversion of DNR or DXR to other products of anthracycline metabolism in S. peucetius.

The above information led us to engineer S. peucetius strains that were comparatively high-level producers of DXR. Introduction of the dnrU::aphII mutation into a dnrX mutant significantly increased DXR production (Table 2). Also, introduction of the dnrH::aac(3)IV mutation into the WMH1662 dnrX dnrU double mutant led to increased DXR production by the triple mutant, as noted above. The resulting strains, WHM1667 and WMH1668, behaved as expected, since both produced considerably more DXR than any of their predecessors. Similarly, introduction of the dnrU and dnrH mutations into an overproducing strain that does not produce the acid-sensitive, baumycin-like metabolites (such as a dnrX mutant [40]) led to a very low level of accumulated RHO, low DNR, and very low 13-dihydro-DNR titers and a five- to eightfold increase in DXR titer compared with that of the parent dnrU+ dnrH+ strain (22). We believe that these comparatively high yields result from blocking the diversion of DNR and DXR or their precursors to acid-sensitive metabolites, some of which might not be suitable substrates for DoxA (19), as well as from inhibition of the formation of 13-dihydro-DNR. Further yield enhancement might be achieved by increasing expression of the dnrV and doxA genes at the onset of DNR biosynthesis. In fact, the DXR titer of strain WMH1662 was raised 36% and that of strain WMH1667 was raised 86% upon introduction of pWHM547, containing the dnrV and doxA genes under the control of the ermEp* promoter, compared with the values for the vector-only control strains (data not shown). Expression of other genes known to limit DNR biosynthesis in the wild-type strain, such as dnmT, required for daunosamine biosynthesis (52), and the DNR and DXR self-resistance genes (drrA and drrB [28], drrC [38], and drrD [1]), might also have to be increased to obtain the optimum yield.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Umberto Breme for HPLC analyses and G. Ventrella for production of DoxA antibodies and Western blot analyses.

This research was supported by grants from Pharmacia & Upjohn and the National Institutes of Health (CA 64161).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ali, A., and C. R. Hutchinson. Unpublished results.

- 2.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schäffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen J F, Hutchinson C R. Characterization of Saccharopolyspora erythraea cytochrome P-450 genes and enzymes, including 6-deoxyerythronolide B hydroxylase. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:725–735. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.3.725-735.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ando N, Ueda K, Horinouchi S. A Streptomyces griseus gene (sgaA) suppresses the growth disturbance caused by high osmolarity and a high concentration of A-factor during early growth. Mol Microbiol. 1997;143:2715–2723. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-8-2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arcamone F. Doxorubicin: anticancer antibiotics. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arcamone F, Animati F, Capranico G, Lombardi P, Pratesi G, Manzini S, Supino R, Zunino F. New developments in antitumor anthracyclines. Pharmacol Ther. 1998;76:117–124. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(97)00096-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arcamone F, Cassinelli G, Fantini G, Grein A, Orezzi P, Pol C, Spalla C. 14-Hydroxydaunomycin, a new antitumor antibiotic from Streptomyces peucetius var. caesius. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1969;11:1101–1110. doi: 10.1002/bit.260110607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bairoch A. PROSITE: a dictionary of sites and patterns in proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:2013–2018. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.suppl.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bibb M, Sherman D H, Omura S, Hopwood D A. Cloning, sequencing and deduced functions of a cluster of Streptomyces genes probably encoding biosynthesis of the polyketide antibiotic frenolicin. Gene. 1994;142:31–39. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90351-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bibb M J, White J, Ward J M, Janssen G R. The mRNA for the 23S rRNA methylase encoded by the ermE gene of Saccharopolyspora erythraea is translated in the absence of a conventional ribosome-binding site. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:533–545. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb02187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chater K F. Streptomyces phages and their application to Streptomyces genetics. In: Queener S E, Day L E, editors. The bacteria. 9. Antibiotic-producing Streptomyces. Orlando, Fla: Academic Press; 1986. pp. 119–158. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen C W, Yu T-W, Chung H-M, Chou C-F. Discovery and characterization of a new transposable element, Tn4811, in Streptomyces lividans 66. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7762–7769. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.23.7762-7769.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coupe S A, Taylor J E, Isaac P G, Roberts J A. Characterization of a mRNA that accumulates during development of oilseed rape pods. Plant Mol Biol. 1994;24:223–227. doi: 10.1007/BF00040589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dekleva M L, Strohl W R. Glucose-stimulated acidogenesis by Streptomyces peucetius. Can J Microbiol. 1987;33:1129–1132. doi: 10.1139/m87-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dekleva M L, Titus J A, Strohl W R. Nutrient effects on anthracycline production by Streptomyces peucetius in a defined medium. Can J Microbiol. 1985;31:287–294. doi: 10.1139/m85-053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denis F, Brzezinski R. An improved aminoglycoside resistance gene cassette for use in gram-negative bacteria and Streptomyces. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1991;81:261–264. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(91)90224-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dickens M L, Strohl W R. Isolation and characterization of a gene from Streptomyces sp. strain C5 that confers the ability to convert daunomycin to doxorubicin on Streptomyces lividans TK24. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3389–3395. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.11.3389-3395.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dickens M L, Priestley N D, Strohl W R. In vivo and in vitro bioconversion of ε-rhodomycinone glycoside to doxorubicin: functions of DauP, DauK, and DoxA. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2641–2650. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.8.2641-2650.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dickens M L, Ye J, Strohl W R. Cloning, sequencing, and analysis of aklaviketone reductase from Streptomyces sp. strain C5. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3384–3388. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.11.3384-3388.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernandez-Moreno M A, Martinez E, Caballero J L, Ichinose K, Hopwood D A, Malpartida F. DNA sequence and functions of the actVI region of the actinorhodin biosynthetic gene cluster of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) J Biol Chem. 1994;269:24854–24863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Filippini, S., and A. L. Colombo. Unpublished results.

- 23.Fujiwara A, Hoshino T. Anthracyclic antibiotics. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 1983;3:133–157. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Furuya K, Hutchinson C R. The DnrN protein of Streptomyces peucetius, a pseudo-response regulator, is a DNA-binding protein involved in the regulation of daunorubicin biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6310–6318. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.21.6310-6318.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gerlitz M, Meurer G, Wendt-Pienkowski E, Madduri K, Hutchinson C R. The effect of the daunorubicin dpsH gene on the choice of starter unit and cyclization pattern reveals that type II polyketide synthases can be unfaithful yet intriguing. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:7392–7393. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grein A. Antitumor anthracyclines produced by Streptomyces peucetius. Adv Appl Microbiol. 1987;32:203–214. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2164(08)70081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grimm A, Madduri K, Ali A, Hutchinson C R. Characterization of the Streptomyces peucetius ATCC 29050 genes encoding doxorubicin polyketide synthase. Gene. 1994;151:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90625-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guilfoile P G, Hutchinson C R. A bacterial analog of the mdr gene of mammalian tumor cells is present in Streptomyces peucetius, the producer of daunorubicin and doxorubicin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8553–8557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hallam S, Malpartida F, Hopwood D. DNA sequence, transcription and deduced function of a gene involved in polyketide antibiotic synthesis in Streptomyces coelicolor. Gene. 1989;74:305–320. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90165-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hopwood D A, Bibb M J, Chater K F, Kieser T, Bruton C J, Kieser H M, Lydiate D J, Smith C P, Ward J M, Schrempf H. Genetic manipulation of Streptomyces: a laboratory manual. Norwich, United Kingdom: The John Innes Foundation; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hopwood D A, Sherman D H. Molecular genetics of polyketides and its comparison to fatty acid biosynthesis. Annu Rev Genet. 1990;24:37–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.24.120190.000345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hutchinson C R. Biosynthetic studies of daunorubicin and tetracenomycin C. Chem Rev. 1997;97:2525–2535. doi: 10.1021/cr960022x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Inventi-Scolari, A., F. Torti, S. L. Otten, A. L. Colombo, and C. R. Hutchinson. Process for preparing doxorubicin, U.S. patent applied for.

- 34.Katz L, Donadio S. Polyketide synthesis: prospects for hybrid antibiotics. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1993;47:875–912. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.004303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Le Gouill C, Desmarais D, Dery C V. Saccharopolyspora hirsuta 367 encodes clustered genes similar to ketoacyl synthase, ketoacyl reductase, acyl carrier protein and biotin carboxyl carrier protein. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;240:146–150. doi: 10.1007/BF00276894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lombo F, Blanco G, Fernandez E, Mendez C, Salas J A. Characterization of Streptomyces argillaceus genes encoding a polyketide synthase involved in the biosynthesis of the antitumor antibiotic mithramycin. Gene. 1996;172:87–91. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00029-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lomovskaya N, Hong S-K, Kim S-U, Fonstein L, Furuya K, Hutchinson C R. The Streptomyces peucetius drrC gene encodes a Uvr-like protein involved in daunorubicin resistance and production. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3238–3245. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.11.3238-3245.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lomovskaya N, Fonstein L, Ruan X, Stassi D, Katz L, Hutchinson C R. Gene disruption and replacement in the rapamycin-producing Streptomyces hygroscopicus strain ATCC 29253. Microbiology. 1997;143:875–883. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-3-875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lomovskaya N, Doi-Katayama Y, Filippini S, Nastro C, Fonstein L, Gallo M, Colombo A L, Hutchinson C R. The Streptomyces peucetius dpsY and dnrX genes govern early and late steps of daunorubicin and doxorubicin biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2379–2386. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.9.2379-2386.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Madduri K, Hutchinson C R. Functional characterization and transcriptional analysis of the dnrR1 locus, which controls daunorubicin biosynthesis in Streptomyces peucetius. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1208–1215. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.5.1208-1215.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Madduri K, Kennedy J, Rivola G, Inventi-Solary A, Filippini S, Zanuso G, Colombo A L, Gewain K M, Occi J L, MacNeil D J, Hutchinson C R. Production of the antitumor drug epirubicin (4′-epidoxorubicin) and its precursor by a genetically engineered strain of Streptomyces peucetius. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:69–74. doi: 10.1038/nbt0198-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meurer G, Gerlitz M, Wendt-Pienkowski E, Vining L C, Rohr J, Hutchinson C R. Iterative, type II polyketide synthases, cyclases and ketoreductases exhibit context dependent behavior in the biosynthesis of linear and angular decapolyketides. Chem Biol. 1997;4:433–443. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(97)90195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Munro A W, Lindsay J G. Bacterial cytochromes P-450. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:1115–1125. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Myers C E, Mimnaugh E G, Yeh G C, Sinha B K. Biochemical mechanisms of tumor cell kill by anthracyclines. In: Lown J W, editor. Anthracycline and anthracenedione-based anti-cancer agents. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1988. pp. 527–569. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Otten S L, Ferguson J, Hutchinson C R. Regulation of daunorubicin production in Streptomyces peucetius by the dnrR2 locus. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1216–1224. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.5.1216-1224.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Otten S L, Stutzman-Engwall K J, Hutchinson C R. Cloning and expression of daunorubicin biosynthesis genes from Streptomyces peucetius and S. peucetius subsp. caesius. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3427–3434. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.3427-3434.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Poulos T L, Finzel B C, Howard A J. High-resolution crystal structure of cytochrome P450CAM. J Mol Biol. 1987;195:687–700. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rajgarhia V, Strohl W R. Minimal Streptomyces sp. strain C5 daunorubicin polyketide biosynthesis genes required for aklanonic acid for biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2690–2696. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.8.2690-2696.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sambrook J, Fritch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. 1 to 3. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]