Abstract

The mutagenic and carcinogenic properties of chromium(VI) complexes have been ascribed to the formation of ternary Cr(III)-small molecule-DNA complexes. As part of these laboratories’ efforts to establish the structure and properties of discrete binary and ternary adducts of Cr(III) and DNA at a molecular level, the properties of Cr(III)-cysteine-DNA, Cr(III)-ascorbate-DNA, and Cr(III)-glutathione-DNA complexes formed from Cr(III) were examined. These studies determined the composition of previously described “pre-reacted” chromium cysteinate and chromium glutathione. Neither of these complexes nor “chromium ascorbate” form ternary complexes with DNA as previously proposed. In fact, these Cr(III) compounds do not measurably bind to DNA and cannot be responsible for the mutagenic and carcinogenic properties ascribed to ternary Cr(III)-cysteine-DNA and Cr(III)-ascorbate-DNA adducts. The results of biological studies where “ternary adducts” of Cr(III), cysteine, glutathione, or ascorbate and DNA were made from “pre-reacted” chromium cysteinate or chromium glutathione or from “chromium ascorbate” must, therefore, be interpreted with caution.

Keywords: Chromium, Cysteine, Ascorbate, Glutathione, DNA, Cancer

Introduction

Chromium(VI) is a potent carcinogen and mutagen when inhaled, and questions have been raised about its potential toxicity at high concentrations in drinking water [1]. The molecular-level mechanism for this toxicity is unclear although it involves processes during the reduction of Cr(VI) to Cr(III). These include the generation of the potent oxidants Cr(IV) and Cr(V), the generation of reactive organic radicals, and ultimately formation of Cr(III). While numerous studies have probed the potential effects of radical reactions and oxidation, studies of the effects of Cr(III) binding to DNA have been rather limited, particularly at a molecular level. However, the amount of Cr(III) adducts formed appear to correlate with the DNA damage and subsequent cellular effects [1]. More specifically, increases in the number of nucleotide misincorporations by polymerases in vitro [2] and the accompanying polymerase arrest [3–5] have been reported to result from the binding of Cr(III) to DNA [6].

The genotoxicity of Cr(III)-DNA adducts is a function of whether they are binary or involve a third molecule in a ternary complex. Ternary adducts are believed to be premutagenic [7], while binary adducts have less mutagenic potential or are non-mutagenic. For example, Cr(III) DNA ternary adducts reportedly are stronger inhibitors of replication in plasmids transfected into human cells than binary adducts [8, 9]. Their mutagenicity and carcinogenicity appear to arise by inappropriate processing by mismatch repair (MMR) proteins [10–13].

In vitro and in treated cells, Cr and DNA reportedly form ternary complexes with several free amino acids (most notably cysteine, glutamate, glutamine, and histidine), peptides (such as glutathione), proteins, and other small biomolecules such as ascorbic acid [14–19]. Ternary complexes involving ascorbate, glutathione, and amino acids such as histidine and cysteine have all been found to be mutagenic; the ascorbate complex appears to be the most mutagenic ([6] and references therein). Single-base substitutions were the major type of mutation identified for glutathione and amino acid adducts [20]. Ternary ascorbate adducts lead to similar amounts of point mutations as well as larger genetic changes [9]. The identified changes occurred primarily at G/C pairs leading to G/C → T/A transversions and G/C → A/T transitions, regardless of the adduct type [6, 8, 9, 20]. As a result, Cr(III) has been postulated to associate with guanine bases, and three-dimensional structures of such adducts have been proposed [6]. Recently, occupational Cr carcinogenesis has been suggested to involve selection of Cr(VI)-resistant, MMR (mismatch repair)-deficient cells [10, 21]. Proportionally increased chromosomal breakage from chromate resulted from increased ascorbate levels in cells [11, 13]; aberrant mismatch repair of Cr damage in replicated DNA resulted in double-strand breaks in G2 phase cells.

The unwinding of plasmid DNA from reaction with [Cr(III)(cysteine)2]− or CrCl3 has also been examined [22]. The Cr(III)-cysteine complex only weakly interacted with DNA, while addition of CrCl3 only resulted in unwinding DNA by 1–2. CrCl3 was found to be non-nrutagenic, suggesting that under the study conditions only binary complexes formed [22]. Oligonucleotides (39-mer) with randomized sequences have also been utilized to examine cysteine binding in the presence of Cr(III) and Cr(VI) [14]. Yet, only the quantity of cysteine associated with the oligonucleotides after a 2-h incubation was determined; results varied on Cr source and whether the Cr was “pre-reacted” with cysteine [13]. The results of these studies were interpreted to suggest that Cr binds to phosphate groups; but no direct evidence for this was presented.

Similarly, participation of DNA phosphate groups in binding Cr has also been proposed based on the prevention of Cr(VI)-induced ascorbate-DNA cross-links in calf thymus DNA or 40-mer single-stranded oligonucleotides by phosphate buffer [23]; yet, EDTA and other coordinating ligands had similar effects on preventing the binding of Cr. Using Cr(III)-cysteine, Cr(III)-histidine, and Cr(III)-glutathione to treat plasmid DNA causes blockage of exonuclease activity of T4 DNA polymerase, but no patterns of blockage from the Cr(III) complexes could be identified that were related to the DNA sequence [20]. These results again led to the suggestion Cr(III) binding was random and phosphate groups could be involved.

These laboratories have recently shown the structure(s) of potential Cr(III)-binding sites can be characterized at a molecular level using oligodeoxynucleotide duplexes and a variety of spectroscopic techniques [24]. Such substrates for Cr(III)-binding can be synthesized and purified to homogeneity in appreciable quantities with complete control of base composition. The adducts that result when DNA is exposed to Cr(III) directly and when Cr(VI) is reduced in the presence of DNA can now be accessed for molecular-level characterization. The binding of Cr(III) to DNA to form binary complexes was found not to involve phosphate groups from the DNA backbone. Instead, the [Cr(III)(H2O)5]3+ moiety was found to bind in the major groove to N-7 of guanines bases, with the aquo ligands hydrogen-bonded to the oligonucleotide; this occurred with very little disturbance of the three-dimensional structure of the oligonucleotide DNA [24], consistent with the results of studies using plasmid DNA [22]. However, the molecular-level structure of Cr(III)-DNA ternary adducts has not yet been explored.

Initial attempts to obtain high-resolution structures of such ternary complexes to determine whether the sites of formation are the same as those for binary lesions and whether formation of these complexes is accompanied by the same lack of deformation have not met with success. Previous studies of Cr-DNA ternary complexes have focused primarily on the small molecules, e.g., ascorbate, and amino acids, primarily histidine and cysteine [14]. As Cr complexes with histidine are much better characterized than those with cysteine or ascorbate, the potential to form ternary DNA-Cr-histidine complexes was examined by these laboratories. However, unlike the literature reports, DNA-Cr-histidine ternary complexes were not found starting from Cr(III); instead, Cr(III)-histidine complexes were found to be minor groove binders [25].

Herein are reported studies to extend the attempts to prepare and characterize DNA-Cr-ternary complexes starting from Cr(III) and ascorbic acid or cysteine.

Experimental

Chemicals

All chemicals were used as received. CrCl3·6H2O, Cr(NO3)3·9H2O, and l-ascorbic acid were from Fisher (Fairlawn, NJ); D2O was from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc. (Andover, MA); l-cysteine and l-glutathione were from Sigma (St. Fouis, MO); 1,5-diphenylcarbazide was from Riedel–De Haen (Seelze, Germany); and NaOH, H2O2, and H2SO4 were from VWR (Radnor, PA). The anion exchange media DE52 was from Whatman (Maidstone, England). Oligonucleotide DNAs were synthesized by GenScript (Piscataway, NJ). The DNA oligonucleotide was stored in a −20 °C freezer before use. Doubly deionized water was used throughout.

DNA Solution Preparation

The self-complimentary oligonucleotide 5′-ATAGG TATAC CTAT-3′ was dissolved in H2O. The pH of the solutions was then adjusted to pH of 7.0 (± 0.1) with HCl or NaOH. The final concentrations of the oligonucleotides were determined using the absorbance of solutions at 260 nm (ε = 1.454 × 105 M−1 cm−1). Solutions were annealed on a Fisher Scientific dry bath incubator by heating at 95 °C for 5 min and then allowed to cool to room temperature over the course of 4 h.

NMR Spectroscopy

Experiments with the oligonucleotide were performed at 283 K in D2O with 50 mM NaCl. Solutions for NMR and other studies were allowed to sit for 24 h after the addition of Cr(III) (0–4 equivalents Cr(III) per oligonucleotide) before being used in the subsequent experiments. One-dimensional 1H spectra were collected on either a Bruker Avance NEO-500 with cryoprobe or AM-500 spectrometers (Billerica, MA) using the zg pulse program with 128 scans. 31P spectra were collected on the AM-500 spectrometer using the zgpg30 pulse program with 2400 scans. The data was then processed in Topspin 3.5pl7 using a Gaussian method. The non-exchangeable proton resonances of the oligonucleotide have been assigned previously [24].

Experiments with the synthetic Cr(III) complexes were performed on a Bruker AM-360 spectrometer (Billerica, MA).

Electronic Spectroscopy, Mass Spectrometry, pH Titrations, and Lipophilicity Measurements

Electronic spectra were measured on a Beckman Coulter DU-800 spectrophotometer (Brea, CA). Electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectra were collected using a Bruker HCTultra PTM Discovery System quadrupole ion trap mass spectrometer; samples were dissolved in water and diluted with a 50:50 mixture of acetonitrile:water (except for the Cr glutathione complex). Spectra were collected in the negative mode. pH titrations were performed using a Denver Instruments Basic pH meter with a pH ACT electrode (Bohemia, NY) or with a Mettler-Toledo LE422 microelectrode (Columbus, OH). pH was adjusted with solutions of HCl or NaOH. After adjusting the pH, solutions were allowed to sit overnight before measurement of the electronic spectra to guarantee that equilibrium was reached. The partitioning of chromium(III) complexes between octanol and water was examined. Aqueous solutions of the chromium(III) complexes were vigorously shaken with an equal volume of octanol, the layers were allowed to separate, and the electronic spectrum of each layer was obtained.

Ultrafiltration Studies

The binding of Cr(III) complexes to the oligonucleotide duplex was examined by a variation of the equilibrium dialysis method using a centrifugal filter. Aliquots of the Cr(III) complexes were added to an ~ 0.3 to 1.0 mM solution of oligonucleotide in 500 mL of H2O with pH adjusted to 7.0 at 4 °C. The resulting solutions were stored for 24 h to reach equilibrium and then were placed in an Amicon Ultra 0.5-mL centrifugal filter (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) with a 3000 molecular weight cutoff. The device was centrifuged, and effluent was collected. The content of Cr(III) in the effluent was determined by atomic absorption spectroscopy, using a PerkinElmer Analyst 400 atomic absorption spectrometer. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Trials were also performed without DNA and revealed that the initial Cr concentration and the concentration of Cr in the effluent were identical within error. Similarly, trials were performed without Cr and the concentration of DNA was determined by UV absorbance at 260 nm; only a small amount of DNA passed through the filter [24].

Preparation of Sodium Bis(l-cysteinato) chromate(III) Dihydrate, Potassium Bis(glutathionato)chromate(III) Trihydrate, and “Chromium ascorbate”

Dark blue crystals of the compound sodium bis(l-cysteinato)chromate(III) dihydrate, Na[Cr(III) (cysteinate)2]·2H2O, were prepared by the method of Ref. [26]. Potassium bis(glutathionato)chromate(III) trihydrate, K2[Cr(gluathione2−)(glutathione3−)]·3H2O, was prepared by the method of Ref. [27], although Cr(ClO4)3·9H2O was replaced with Cr(NO3)3·9H2O. K[Cr(III)(ascorbate)2]·7H2O, “chromium ascorbate,” was prepared by the method of Ref. [28].

Results and Discussion

Chromium and Cysteine

Zhitkovich and coworkers have reported that the addition of cysteine to DNA with bound Cr(III) does not yield ternary adducts [14]. They found that the addition of the mixture to a size exclusion column resulted in separation of the binary Cr(III)-DNA adducts from cysteine. When a pre-reacted mixture of Cr(III) and cysteine was added to DNA, a potential ternary complex was observed by co-localization of [35S] cysteine with DNA after purification by size exclusion chromatography. However, the pre-reacted Cr(III) and cysteine mixture produced by mixing 50 μM CrCl3·6H2O and 500 μM cysteine in 10 mM MES buffer (pH 6.1) at 50 °C for 5 h or at 37 °C for 2 h was not characterized in this report [14].

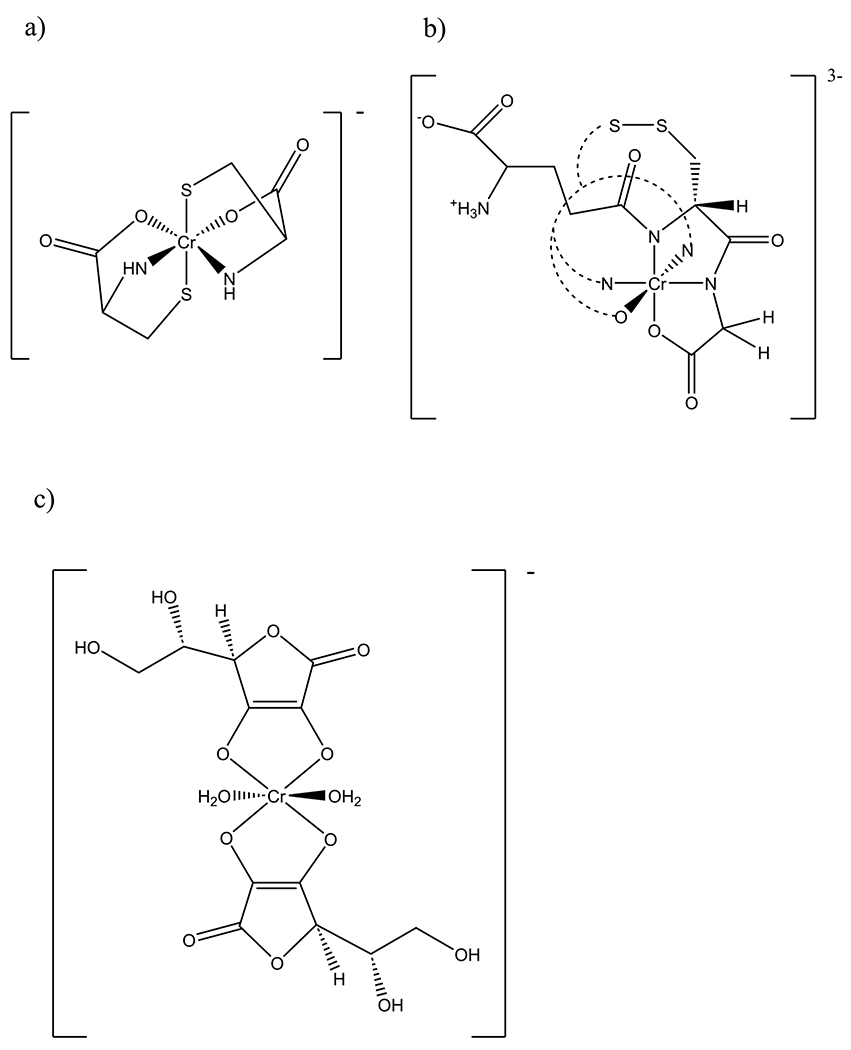

The reaction of cysteine with Cr(III) has been studies on numerous occasions, although the products are often poorly characterized [26, 29–31]. However, the reaction of three equivalents of cysteine with one equivalent of Cr(III) in boiling water has been shown to produce dark blue crystals of the compound Na[Cr(III)(cysteinate)2]·2H2O [26] (Fig. 1). The stability of [Cr(III)(cysteinate)2]− in acidic media has been examined [32, 33], demonstrating that between pH 7 and 1 that various protonation states and hydrolysis products of the anion can be detected.

Fig. 1.

Structure of a [Cr(III)(cysteinate)2]− and plausible structures for b [Cr(III)(glutathione disulfide)]2− and c [Cr(III) (ascorbate)2(H2O)2]−. For the latter two complexes, insufficient information is available to establish which isomer is present. In panel b, half the glutathione disulfide ligand is represented by dashed lines for clarity

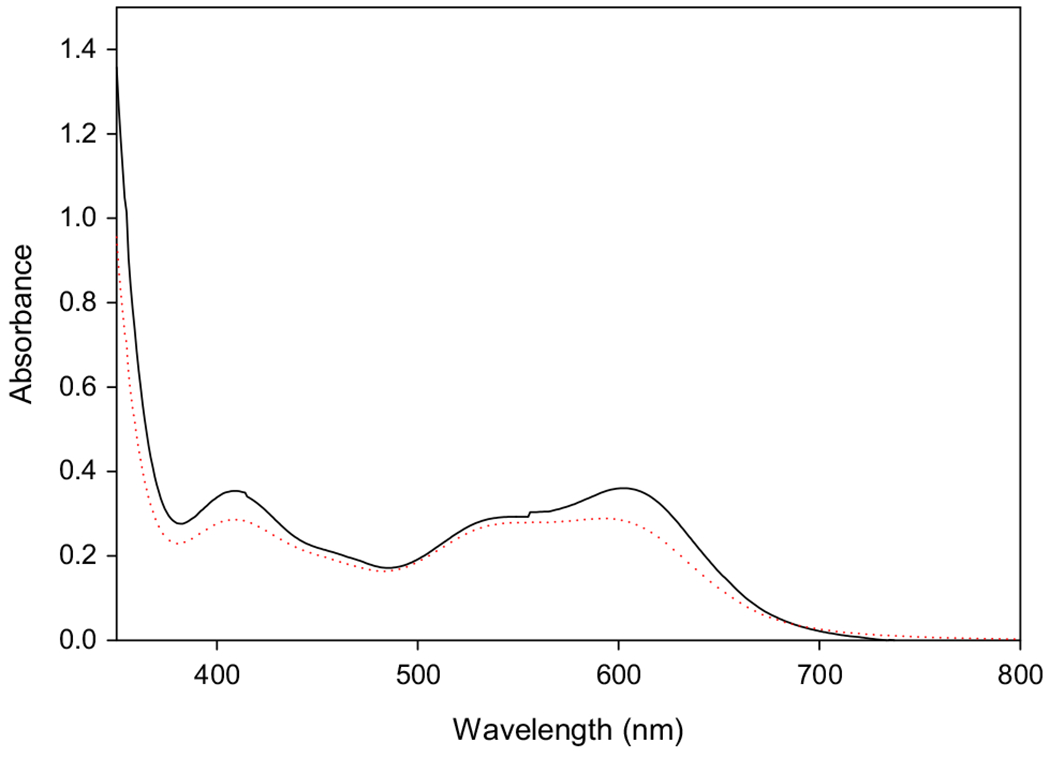

Knowing what species are present to potentially bind to DNA in the experiments of Zhitkovich and coworkers is important in attempting to understand the formation and structure of any potential ternary adducts. Thus, the reaction of chromium(III) and cysteine was performed, but the concentrations of both compounds were increased by tenfold so that visible absorbance spectra of suitable intensity could be measured on the resulting solution. The visible spectra after the solutions were heated for 5 h at 50 °C and allowed to cool revealed that the solutions were composed primarily, of [Cr(III)(cysteinate)2]− (Fig. 2), with a small amount of [Cr(III)(cysteinate)(Hcysteinate)] as the absorption maxima were at ~ 409 and ~ 594 nm ([Cr(III)(cysteinate)2]− has maxima at 418 and 608 nm, while [Cr(III)(cysteinate) (Hcysteine)] has maxima at 407 and 533 nm [33]). The position of the absorption maxima for the “pre-reacted” solutions shifts slightly from run to run as the final pH varies slightly from run to run and drops from the initial pH of 6.1 to below 6 as the reaction proceeds. (Details of the pH dependence of the visible spectra of the “pre-reacted” solutions is described below.) The formation of the bis(chelate) complex is not surprising given the 10:1 cysteine:Cr(III) ratio. When the mixture was applied to a DE52 anion exchange column, washed with water, and eluted with 0.1 M NaCl, a single blue band was observed, with the visible spectrum of [Cr(III)(cysteinate)2]−.

Fig. 2.

Electronic spectrum of “pre-reacted” Cr(III)-cysteine solutions. [Cr(III)] = 5 mM. Dashed red line, reaction at 50 °C for 5 h; solid black line, reaction at 37 °C for 2 h

When the reaction is run at 37 °C for 2 h, the results are very similar with the solution having visible absorbance maxima at ~ 408 and 604 nm (Fig. 2). Only a single blue band again could be observed upon anion exchange chromatography. Thus, both “pre-reacted” solution, regardless of the temperature or time, generate the same predominate species, [Cr(III)(cysteinate)]− with small amounts of [Cr(III) (cysteinate)(Hcysteine)].

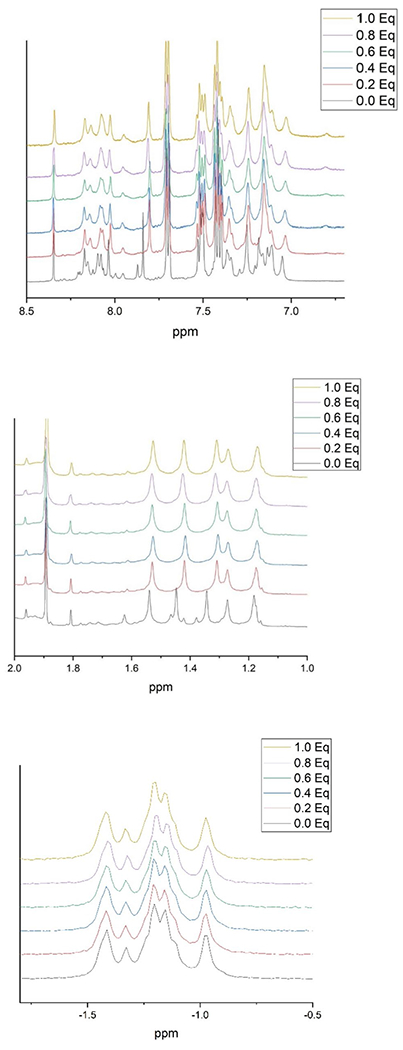

Ultrafiltration studies found no detectable binding of [Cr(III)(cysteinate)]− in the “pre-reacted solutions” of Zhitkovich to DNA. Given the anionic complex is stable at neutral pH, its failure to bind to the polyanionic oligonucleotide is not surprising. Similarly, no binding of the anionic complex, whether as the “pre-reacted” solution or the isolated compound, to the oligonucleotide could be detected by 1H or 31P NMR under conditions in which the addition of CrCl3·6H2O has been shown to generate binary Cr(III)-oligonucleotide adducts (Fig. 3) [24]; only broadening of the signals from the increase in the paramagnetism from the increase in the concentration of Cr(III) in solution was observed. (However, for the “pre-reacted solution,” which has tenfold ratio of cysteine to Cr(III), addition of first aliquot of the “pre-reacted” solution results in shifts of some of the 1H NMR signals, indicating some changes in the geometry about some of the bases. This effect arises solely from the ionic strength from buffered cysteine solutions and lead to the subsequent inclusion of the 50 mM NaCl in all samples, which prevents this effect, including when this experiment is reperformed with included NaCl.) This is consistent with the reported inability of the anionic complex to bind to DNA to form adducts in CHO cells, while the addition of CrCl3·6H2O lead to the formation of Cr-DNA adducts [22]. (Concentrated solutions of [Cr(III)(cysteinate)2]− in D2O did not give rise to any observable 1H NMR signals as a result of paramagnetic broadening from the presence of the S = 3/2 Cr(III) center.) Na[Cr(III)(cysteinate)2]·2H2O does not dissolve in octanol, so that none of the compound partitions into octanol when solutions are shaken with water, indicating it is extremely hydrophilic. Similarly, no detectable amount of the Cr(III) products from the “pre-reacted” chromium and cysteine solutions partition into the octanol layer.

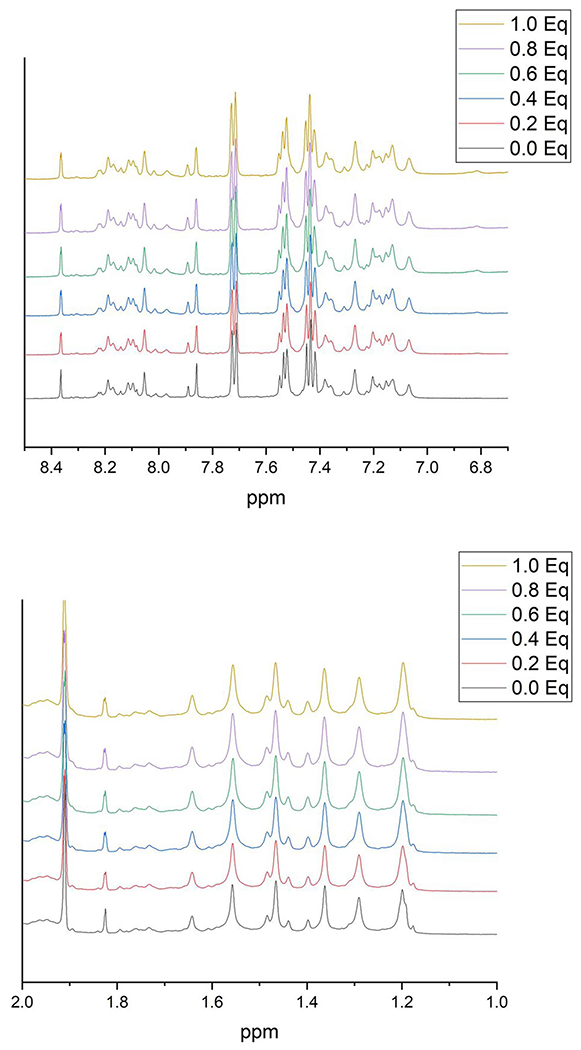

Fig. 3.

1H NMR spectrum of the (top) base proton region, (middle) methyl proton region, and.31P NMR spectrum (bottom) of oligonucleotide with and without the addition of varying quantities of prereacted Cr(III)-cysteine solution (50 °C, 5 h)

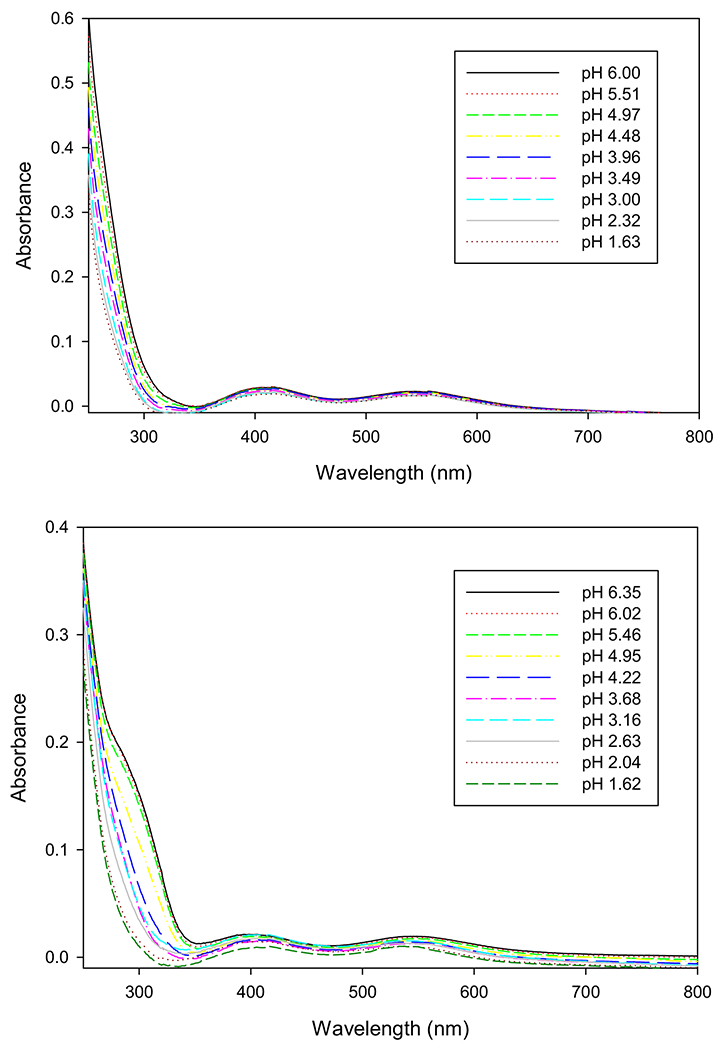

The failure of [Cr(III)(cysteinate)2]− to form an adduct with the oligonucleotide is not surprising as, in addition to being anionic, the complex lacks any open coordination sites available to bind the Cr(III) covalently to the oligonucleotide. Thus, loss of cysteine would need to occur to form a covalent ternary oligonucleotide-Cr(III)-cysteinate complex. Acid hydrolysis should result in loss of cysteine to generate [Cr(III)(cysteinate)(H2O)3]+, which would potentially be able to such a ternary adduct. Acidification of solutions of isolated [Cr(III)(cysteinate)2]− have been shown to result in protonation to [Cr(III)(cysteinate)(cysteine)] and [Cr(III)(cysteine)2]+, along with their aquation to [Cr(III)(cysteinate)(H2O)3]+ and [Cr(III) (cysteine)(H2O)3]2+ [33]. To confirm the identity of the Cr(III)-containing species in the “pre-reacted” solutions, the “pre-reacted” solutions were titrated (Fig. 4). For the “pre-reacted” solutions formed at both 50 and 37 °C, the initial lowering the pH generated an isobestic point at ~ 580 nm, suggesting the formation of [Cr(III)(cysteinate)(cysteine)]. The shift in the visible maxima to shorter wavelength is also consistent with this, as the maxima for [Cr(III)(cysteinate)(cysteine)] are reported to be at 407 and 533 nm. These results are consistent with the reported behavior of [Cr(III)(cysteinate)2]−.

Fig. 4.

Electronic spectra from pH titration of “pre-reacted” Cr(III)-cysteine solutions. Top: reaction at 50 °C for 5 h; bottom: reaction at 37 °C for 2 h. Eq—ratios of equivalents of Cr3+ per oligonucleotide

As the pH is decreased, no isobestic points are present, suggesting multiple species in solution. These changes are similar to those reported for the aquation of [Cr(III) (cysteinate)2]− which only occurs at lower pH where [Cr(III) (cysteinate)(cysteine)] is likely present [33]. Thus, the behavior of the “pre-reacted” solutions is consistent with the presence of [Cr(III)(cysteinate) 2]−.

However, the product of aquation of [Cr(III)(cysteinate)2]−, [Cr(III)(cysteinate)(H2O)3]+, could provide an avenue for the synthesis of Cr(III)-cysteinate-DNA ternary complexes. The aquo ligands should much more readily be displaced than the tridentate cysteinate ligand providing sites for the formation of covalent bonds with the N-7 of guanine bases or other sites on the DNA. [Cr(III)(cysteinate)(H2O)3]+ was prepared using the method of Ref. [33] in order to test this potential route to ternary complexes. Titration of the oligonucleotide duplex with [Cr(III)(cysteinate) (H2O)3]+ was followed by 1H NMR. No specific broadening of 1H NMR signals was observed. Heating the samples up to 75 °C for prolonged periods of time had no effect. Neither did increasing [Cr(III)(cysteinate)(H2O)3]+ concentration until DNA precipitation started to occur. Evidently, this Cr(III) complex with three comparatively labile aquo ligands did not form a detectable amount of ternary complexes. Importantly, no evidence was observed that the complex lost cysteine to form Cr(III)-DNA binary complexes as well.

In a final attempt to make ternary Cr(III)-cysteinate-DNA complexes, binary Cr(III)-DNA complexes prepared as described in Ref. [24] were treated up to 20-fold excesses of cysteine and heated for over 24 h at temperatures up to 75 °C. No change in the 1H NMR spectrum of the binary complex was observed; similarly, no change was observed in the intensity of the 1H NMR signals from free cysteine. Thus, no detectable formation of a Cr(III)-cysteinate-DNA complex could be observed.

Chromium and Glutathione

Zhitkovich and coworkers have reported the binding of “pre-reacted” products of Cr(III) and glutathione to form ternary Cr-DNA-glutathione adducts [20]. They produced their pre-reacted Cr(III) and glutathione mixture by mixing 1 mM CrCl3·6H2O and 10 mM glutathione in 10 mM MES buffer (pH 6.1) at 50 °C for 5 h. Without any characterization, they reacted this “pre-reacted” Cr and glutathione solution with DNA for 2 h at 37 °C. These conditions were reported to result in the formation of fewer ternary adducts than similar reactions of DNA with “pre-reacted” Cr and histidine and Cr and cysteine solutions [20].

The reaction of l-glutathione with Cr(III) has been studied on a few occasions, although the products are often poorly characterized [27, 28, 34]. Reaction of one equivalent of [Cr(H2O)6]3+ with two equivalents of glutathione in a mixture of ethanol and aqueous bicarbonate at elevated temperature results in the formation of [Cr(III)(glutathione2−)(glutathione3−)]2−, which crystallizes from the resulting solution of aqueous bicarbonate at pH 7–8 [27]. Unfortunately, X-ray quality crystals of the compound have never been prepared and could not be generated in the current study. Dissolved in water, the red-violet compound has visible maxima at 408 and 546 nm (e = 69.5 and 62.4 M−1 cm−1, respectively). The complex was proposed to have different coordination of the two glutathione ligands with only one binding through the cysteine sulfur, consistent with the proposed formula with glutathione ligands with different states of protonation [27]. (Glutathione2− would correspond to both carboxylate groups and the amino terminus being deprotonated; glutathione3− would presumably require a thiolate to additionally be deprotonated). The positions of the wavelength maxima are similar to those of [Cr(III) (cysteine)(Hcysteine)] (407 and 533 nm) [33], although the positions of these maxima would also be consistent with coordination only by a mixture of N and O atoms.

The visible spectrum of “pre-reacted” chromium-glutathione solution has visible maxima at 406 and 545 nm (Fig. 5), identical within error to that of [Cr(III)(glutathione2−)(glutathione3−)]2−. Acidification of the solution results in a shift in the position of the 546 nm band to 540 nm between approximately pH 3 and 1.5 (Fig. 5). Acidification of an aqueous of [Cr(III)(glutathione2−)(glutathione3−)]2− from pH 6.35 to ~ pH 1.5 results in this band shifting to 536 nm (Fig. 5). Negative mode ESI MS of an aqueous solution of [Cr(III)(glutathione2−)(glutathione3−)]2− yielded a signal at m/z 660.0629 consistent with the formula C20H28CrN6O12S2 (calculated m/z = 660.0612). This formula and the need for charge balance suggests the presence of the disulfide of glutathione (Fig. 1). The existence of a disulfide is also consistent with the differences in the UV spectra of the “pre-reacted” solution and the isolated complex between 300 and 350 nm (Fig. 5). The “pre-reacted” solution contains excess glutathione that prevents disulfide formation, while dissolving the isolated complex in water (without excess glutathione) results in air oxidation of the coordinated glutathione. Given its charge, [Cr(III)(glutathione2−(glutathione3−)]2− is, not surprisingly, insoluble in octanol.

Fig. 5.

Electronic spectra from pH titration of Cr(III)-glutathione solutions. [Cr(III)] = 1 mM. Top: “pre-reacted” Cr(IIII)-glutathione solution C; bottom: K2[Cr(gluathione2−) (glutathione3−)]·3H2O in water

Given that the Cr(III) glutathione complex generated in the pre-reaction should be anionic and contain two bound glutathione ligands (such that no free coordination sites are likely present), this complex is a poor candidate to bind to DNA. 1H and 31P NMR studies failed to detect any specific broadening of 1H and 31P NMR signals when double-stranded DNA was titrated with either the “pre-reacted” solution or with a solution of the disulfide of [Cr(III)(glutathione2−)(glutathione3−)]2−, as would be anticipated based on the complex being anionic (Figs. 6 and 7).

Fig. 6.

1H NMR spectrum of the (top) base proton region and (bottom) methyl proton region of oligonucleotide with and without the addition of varying quantities of pre-reacted Cr(III)-glutathione solution. Eq—ratios of equivalents of Cr3+ per oligonucleotide

Fig. 7.

1H NMR spectrum of the (top) base proton region and (bottom) methyl proton region of oligonucleotide with and without the addition of varying quantities of K2[Cr(gluathione2−) (glutathione3−)]·3H2O. Eq—ratios of equivalents of Cr3+ per oligonucleotide

Chromium and Ascorbate

Zhitkovich and coworkers have examined the binding of “chromium ascorbate”, K[Cr(III)(ascorbate2−)2]·7H2O, to reportedly form ternary Cr-DNA-ascorbate adducts [23]. The addition of “chromium ascorbate” at neutral pH to pSP189 DNA led to the cross-linking of ascorbate to DNA, suggesting the formation of ternary adducts, although at much lower levels than the reduction of Cr(VI) in the presence of DNA and ascorbate. At pH 6.0, the extent of crosslinking increased 4.5-fold, although still not to the level of starting from Cr(VI). Thus, using the same methodology as for pre-reacted “chromium histidinate” [25] and pre-reacted “chromium cysteine” (vide supra), attempts were made to probe the molecular structure of any ternary adducts formed from DNA and “chromium ascorbate”.

“Chromium ascorbate” is an amorphous, dark green solid that is highly soluble in water. Unfortunately, it is not well characterized. The formula comes from elemental analysis; room temperature magnetic moment measurements suggest the complex is mononuclear [28]. Numerous efforts by this laboratory failed to crystallize the material. Concentrated solutions of “chromium ascorbate” in D2O did not give rise to any observable 1H NMR signals again as a result of paramagnetic broadening from the presence of the S = 3/2 Cr(III) center. “Chromium ascorbate” has no solubility in octanol; in water:octanol partitioning experiments, no “chromium ascorbate” could be detected in the octanol layer. Negative mode ESI mass spectral results were consistent with the formula [Cr(ascorbate2−)2]−; however, the spectra also suggest the complex is susceptible to oxidation in solution and/or in the gas phase. The most intense feature in the spectra at m/z 175 corresponds to ascorbate (100%) followed by a feature at 207 (88%), which corresponds to an oxidation product of ascorbate, potentially 2,3-diketogulonate·H2O. In the expected mass region for the anionic complex [Cr(ascorbate2−)2]−, two features are found at m/z 400 (58%) and 434 (63%). The former arises from the expected [Cr(ascorbate2−)2]−, while the latter probably corresponds to [Cr(Hdiketogulonate)2]−. Although oxidation occurs, the mass spectra would appear to confirm that “chromium ascorbate” is the hydrated potassium salt of [Cr(ascorbate2−)2]−. However, care must be taken as Cr(III)-aquo complexes readily lose the aquo ligands in ESI mass spectral experiments [35] so that the formulas such as K[Cr(III)(ascorbate2−)2(H2O)2]·5H2O cannot strictly be ruled out.

Similar to ultrafiltration studies with [Cr(III)(cysteinate)]−, ultrafiltration studies found no detectable binding of “chromium ascorbate” to DNA. As the complex is anionic, its failure to bind to the polyanionic oligonucleotide is also not surprising. 1H and 31P NMR studies failed to detect any selective broadening of 1H and 31P signals after titrating double-stranded DNA with “chromium ascorbate” as well.

Previously, the potential of “chromium ascorbate” to bind DNA and its toxic and genotoxic potential have been probed by Gulanowski et al. [36]. “Chromium ascorbate” was found to be neither toxic nor genotoxic in Baccilus subtilis. The compound was also found to undergo chemistry when stored in 0.05 M acetate buffer, pH 5.6 for 24 h; however, the product of this chemistry was not identified. Curiously, the addition of calf thymus DNA (at 1/30 and 1/3 the concentration of the Cr(III) complex) appeared to delay this chemistry. The authors also found a small effect from the compound on the elution of the DNA from hydroxyapatite columns. These changes were much smaller than those from the addition of [Cr(H2O)6]3+ to DNA [36]. The authors concluded that “chromium ascorbate” binds to DNA more weakly than [Cr(H2O)6]3+ (which is known to form binary adducts [24]). Although the authors concluded that “chromium ascorbate” binds DNA [36], the studies are difficult to interpret.

The difficulty can be seen by comparing these results with studies on a complex proposed to have the formula K[Cr(as corbateH−)2(OH)2(H2O)2]·3H2O [37]. This complex has an identical empirical formula to “chromium ascorbate,” and both compounds have similar visible maxima (585 nm for “chromium ascorbate” [28] compared to 582 nm for K[Cr-(ascorbateH−)2(OH)2(H2O)2]·3H2O). The room temperature magnetic moment for K[Cr(ascorbateH−)2(OH)2(H2O)2]·3H2O was reported to be 3.51 B.M. which is lower than the value of 3.76 B.M. reported for “chromium ascorbate.” Electron impact mass spectral results reported on K[Cr(ascorbateH−)2(OH)2(H2O)2]·3H2O (presumably in the positive mode as the mode is not stated) are uninterpretable [34]. The compound was probably destroyed under these harsh conditions. Despite the reported differences, the amorphous dark green, very water-soluble K[Cr(ascorbate)2(OH)2(H2O)2]·3H2O and “chromium ascorbate” are likely the same compound. Thermal decomposition studies suggest two water molecules are coordinated to the Cr(III) [36], so that the formula of “chromium ascorbate” is probably K[Cr(III) (ascorbate2−)2(H2O)2]·5H2O (Fig. 1). The addition of K[Cr (ascorbateH−)2(OH)2(H2O)2]·3H2O to isolated human mitochondrial and genomic DNA has been reported to have no effects on the mobility of the DNA upon electrophoresis or on DNA degradation; only cationic Cr(III) complexes had effects on the DNA [37]. These studies utilizing poorly characterized Cr(III) ascorbate complexes only stresses the need to use well characterized materials to attempt to understand the formation of binary and potentially ternary Cr(III) DNA adducts at a molecular level.

Relationship to Chromate Reduction

This work examines the binding of isolated Cr(III) complexes of cysteine, glutathione, and ascorbate or “pre-reacted” solutions that potentially contain these Cr(III) complexes with a specifically designed oligonucleotide duplex. The results of these studies can be directly compared with previous studies that utilized some of these complexes and their pre-reacted solutions for binding to much larger DNA molecules. Unlike the earlier studies, the use of the oligonucleotide duplex would has allowed for spectroscopic and magnetic studies that could probe the nature of the binding of these Cr(III) species at a molecular level had that occurred.

The relationship of the current studies to previous work examining Cr(III)-DNA adducts generated by the reduction of chromate is less straightforward. The Cr(III)-containing products of the reduction of chromate by cysteine, glutathione, and ascorbate have been shown to be [Cr(cysteine)2]− [38], the disulfide of [Cr(III)(glutathione2−)(glutathione3−)]2− [39], and [Cr(ascorbate)2(H2O)]2 [28], respectively. For cysteine and glutathione, these are the compounds utilized in herein. While it was not possible to rigorously characterize the ascorbate complex, the species utilized here are likely the same as those in the literature. Thus, these studies actually probe the binding of the Cr(III) species generated as end products of the reduction of chromate by three likely biological reductants. The lack of detectable ternary adduct formation utilizing these complexes brings into question the ability of the Cr(III) products from the reduction of chromate by these reductants to form ternary adducts. However, these studies do not rule out the possibility that ternary complexes could be generated from Cr(IV)- and Cr(V)-containing intermediates generating during the reduction by chromate by cysteine, glutathione, and ascorbate. Studies examining the binding of Cr(III) to oligonucleotide duplexes starting from Cr(IV) and Cr(V) complexes are currently underway.

Conclusion

As part of these laboratories’ efforts to establish the structure and properties of discrete binary and ternary adducts of Cr(III) and DNA, the properties of Cr(III)-cysteine-DNA, Cr(III)-glutathione-DNA, and Cr(III)-ascorbate-DNA complexes were examined. Although previous studies report that these “complexes” bind to DNA, we were unable to observe any ternary adduct formation using either characterized Cr complexes or the vaguely defined “pre-reacted” mixtures. The fact that several of these species are anionic makes the lack of interaction with the polyanionic DNA understandable. However, the lack of adduct formation by the cationic and comparatively more exchangeable [Cr(III)(cysteinate) (H2O)3]+ complex was unexpected.

Three explanations can explain these observations. One possible explanation is that the chromium complexes prepared in this work are substantially different that those prepared by other groups. This seems unlikely given that the formation of the chromium complexes is thermodynamically driven. A second possibility is that the 5′-AGG binding site on the oligonucleotide duplex utilized herein is not a competent site for ternary complex formation. However, the 5′-AGG site unequivocally forms binary complexes with Cr(III)(H2O)5 [24] and is reportedly the optimal site for DNA adduct formation [40], making this explanation appear unlikely. The final possible explanation is that contrary to the results reported in the literature, “pre-formed” Cr(III) complexes with small organic ligands cannot form ternary complexes with DNA. Under this scenario, “adducts” reportedly formed in previous studies could not be responsible for the mutagenic and carcinogenic properties ascribed to ternary Cr(III)-cysteine-DNA, Cr(III)-glutathione-DNA, or Cr(III)-ascorbate-DNA adducts. This would not imply that such ternary adducts cannot be formed starting from chromate, but only that mixtures of Cr(III) and ligands are poor models of the chemistry that occurs when chromate is reduced in a cellular medium. The results of biological studies where “ternary adducts” of Cr(III), cysteine, or ascorbate, and DNA must, therefore, be interpreted with caution.

Acknowledgements

We also thank the NSF MRI program (CHE1919906) for the purchase of the 500 MHz NMR spectrometer.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, R15ES033800 (to J.B.V and S.A.W) and the Bioinorganic Chemistry of Chromium Research Fund of The University of Alabama.

Footnotes

Code Availability Not applicable.

Ethics Approval Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest The authors declare no competing interests.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Zhitkovich A (2011) Chromium in drinking water: sources, metabolism, and cancer risks. Chem Res Toxicol 24:1617–1629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Snow ET, Xu LS (1991) Chromium(III) bound to DNA templates promotes increased polymerase processivity and decreased fidelity during replication in vitro. Biochemistry 30:11238–11245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bridgewater LC, Manning FC, Patierno SR (1994) Base-specific arrest of in vitro DNA replication by carcinogenic chromium: relationship to DNA interstrand crosslinking. Carcinogenesis 15:2421–2427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bridgewater LC, Manning FC, Woo ES, Patierno SR (1994) DNA polymerase arrest by adducted trivalent chromium. Mol Carcinog 9:122–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bridgewater LC, Manning FC, Patierno SR (1998) Arrest of replication by mammalian DNA polymerases α and β caused by chromium-DNA lesions. Mol Carcinog 23:201–206 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhitkovich A (2005) Importance of chromium-DNA adducts to mutagenicity and toxicity of chromium(VI). Chem Res Toxicol 18:3–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Brien TJ, Ceryak S, Patierno SR (2003) Complexities of chromium carcinogenesis: role of cellular response, repair and recovery mechanisms. Mutat Res 533:3–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhitkovich A, Song Y, Quievryn G, Voitkun V (2001) Non-oxidative mechanisms are responsible for the induction of mutagenesis by reduction of Cr(VI) with cysteine: role of ternary DNA adducts in Cr(III) dependent mutagenesis. Biochemistry 40:549–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quievryn G, Peterson E, Messer J, Zhitkovich A (2003) Genotoxicity and mutagenicity of chromium(VI)/ascorbate-generated DNA adducts in human and bacterial cells. Biochemistry 42:1062–1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peterson-Roth E, Reynolds M, Quievryn G, Zhitkovich A (2005) Mismatch repair proteins are activators of toxic responses to chromium-DNA damage. Mol Cell Biol 25:3596–3607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reynolds M, Zhitkovich A (2007) Cellular vitamin C increases chromate toxicity via a death program requiring mismatch repair but not p53. Carcinogenesis 28:1613–1620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reynolds MF, Peterson-Roth EC, Johnston T, Gurel VM, Menard HL, Zhitkovich A (2009) Rapid DNA double-strand breaks resulting from processing of Cr-DNA crosslink by both MutS dimers. Cancer Res 69:1071–1079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reynolds M, Stoddard L, Bespalov I, Zhitkovich A (2007) Ascorbate acts as a highly potent inducer of chromate mutagenesis and clastogenesis: linkage to DNA breaks in G2 phase by mismatch repair. Nucleic Acids Res 35:465–476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhitkovich A, Voitkun V, Costa M (1996) Formation of amino acid-DNA complexes by hexavalent and trivalent chromium in vitro: importance of trivalent chromium and the phosphate group. Biochemistry 35:7275–7282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller C-A III, Costa M (1988) Characterization of DNA-protein complexes induced in intact cells by carcinogenic chromate. Mol Carcinog 1:125–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller C-A III, Cohen M-D, Costa M (1991) Complexing of actin and other nuclear proteins to DNA by cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II) and chromium compounds. Carcinogenesis 12:269–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mattagajasingh S-N, Misra H-P (1996) Mechanisms of the carcinogenic chromium(VI)-induced DNA-protein crosslinking and their characterization in cultured intact human cells. J Biol Chem 271:33550–33560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Voitkun V, Zhitkovich A, Costa M (1994) Complexing of amino acids to DNA by chromate in intact cells. Environ Health Perspect 102(Suppl. 3):251–255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhitkovich A, Voitkun V, Costa M (1995) Glutathione and free amino acids form stable complexes with DNA following exposure of intact mammalian cells to chromate. Carcinogenesis 16:907–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Voitkun V, Zhitkovich A, Costa M (1998) Cr(III)-mediated crosslinks of glutathione or amino acids to DNA phosphate backbone are mutagenic in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res 26:2024–2030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhitkovich A, Peterson-Roth E, Reynolds M (2005) Killing of chromium-damaged cells by mismatch repair and its relevance to carcinogenesis. Cell Cycle 4:1050–1052 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blankert SA, Coryell VH, Picard BT, Wolf KK, Lomas RE, Stearns DM (2003) Characterization of nonmutagenic Cr(III)-DNA interactions. 16:847–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quievryn G, Messer J, Zhitkovich A (2002) Carcinogenic chromium(VI) indices cross-linking of vitamin C to DNA in vitro and in human lung A549 cells. Biochemistry 41:3156–3167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown S, Lockart M, Thomas CS, Bowman MK, Woski SA, Vincent JB (2020) Molecular structure of binary chromium(III)-DNA adducts. Chem Bio Chem 21:626–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lankford E, Thomas CS, Marchi S, Brown SA, Woski SA, Vincent JB (2022) Examining the potential formation of ternary chromium-histidine-DNA complexes and implications for their carcinogenicity. Biol Trace Elem Res 200:1473–1481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Meester P, Hodgson DJ, Freeman HC, Moore CJ (1977) Tridentate coordination by the L-cysteine dianion. Crystal and molecular structure of sodium bis(L-cysteinato)chromate(III) dihydrate. Inorg Chem 16:1494–1498 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abdullah M, Barrett J, O’Brien P (1985) Synthesis and characterization of some chromium(III) complexes with glutathione. J Chem Soc Dalton Trans 2085–2089 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cieslak-Golonka M, Raczko M, Staszak Z (1992) Synthesis, spectroscopic and magnetic studies of chromium(III) complexes isolated from in vitro reduction of the chromium(VI) ion with the main cellular reductants ascorbic acid, cysteine, and glutathione. Polyhedron 19:2549–2555 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cooper JA, Blackwell LF, Buckley PD (1984) Chromium(III) complexes and their relationship to the glucose tolerance factor. Part II. Structure and biological activity of amino acid complexes. Inorg Chim Acta 92:23–31 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Freni M, Gervasini A, Romiti P, Beringhelli T, Morazzoni F (1983) Chromium(III) complexes of L(+)-cysteine, DL-penicil-lamine and L(−)-cysteine. Synthesis and spectroscopic characterization. Spectrochim Acta 39A:85–89 [Google Scholar]

- 31.El-Shahawi MS (1993) Chromium(III) complexes of naturally occurring amino acids. Trans Met Chem 18:385–390 [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Brien P, Pedrosa de Jesus JD, Santos TM (1987) A kinetic and equilibrium study of the reactions of potassium and sodium biscysteinato(N,O,S)-chromate(III) in moderately acidic solutions. 131:5–7 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kiersikowska E, Kita E, Kita P (2015) Hydrolytic chromium(III)-sulfur bond cleavage in chromium(III)-cysteine complexes. Trans Met Chem 40:427–435 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Armas MT, Mederos A, Gill P, Dominguez S, Hernandez-Molina R, Lorenzo P, Araujo ML, Brito F, Otero A, Castellanos MG (2004) Speciation in the chromium(III)-glutathione system. Chem Speciat Bioavailab 16:45–52 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Persuad RR, Dieke NE, Jing X, Lambert S, Pursa N, Hartmann E, Vincent JB, Cassady CJ, Dixon DA (2020) A mechanistic study of enhanced protonation by chromium(III) in electrospray ionization: a superacid bound to a peptide. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 31:308–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gulanowski B, Cieslak-Gulonka M, Szyba K, Urban J (1994) In vitro studies on the DNA impairments induced by Cr(III) complexes with cellular reductants. Biometals 7:177–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ay AN, Zumreoglu-Karan B, Oner R, Unaleroglu C, Oner C (2003) Effects of neutral, cationic, and anionic chromium ascorbate complexes on isolated human mitochondrial and genomic DNA. J Biochem Mol Biol 36:403–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kwong DW, Pennington DE (1984) Stoichiometry, kinetics and mechanisms of the chromium(VI) oxidation of L-cysteine at neutral pH. Inorg Chem 23:2528–2532 [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Brien P, Ozolins Z, Wang G (1989) A chromium(III) complex of oxidized glutathione isolated from the reduction of chromium(VI) with glutathione. Inorg Chim Acta 166:301–304 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arakawa H, Wu F, Costa M, Rom W, Tang M-S (2006) Sequence specificity of Cr(III)-DNA adduct formation in the p53 gene: NGG sequences are preferential adduct-forming sites. 27:639–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.