Abstract

Introduction

Domestic dogs and cats can be a source of human infection by a wide diversity of zoonotic pathogens including parasites. Genotyping and subtyping tools are useful in assessing the true public health relevance of canine and feline infections by these pathogens. This study investigated the occurrence, genetic diversity, and zoonotic potential of common diarrhea-causing enteric protist parasites in household dogs and cats in Egypt, a country where this information is particularly scarce.

Methods

In this prospective, cross-sectional study a total of 352 individual fecal samples were collected from dogs (n = 218) and cats (n = 134) in three Egyptian governorates (Dakahlia, Gharbeya, and Giza) during July–December 2021. Detection and identification of Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia duodenalis, Enterocytozoon bieneusi, and Blastocystis sp. were carried out by PCR and Sanger sequencing. Basic epidemiological variables (geographical origin, sex, age, and breed) were examined for association with occurrence of infection by enteric protists.

Results and discussion

The overall prevalence rates of Cryptosporidium spp. and G. duodenalis were 1.8% (95% CI: 0.5–4.6) and 38.5% (95% CI: 32.0–45.3), respectively, in dogs, and 6.0% (95% CI: 2.6–11.4) and 32.1% (95% CI: 24.3–40.7), respectively, in cats. All canine and feline fecal samples analyzed tested negative for E. bieneusi and Blastocystis sp. Dogs from Giza governorate and cats from Dakahlia governorate were at higher risk of infection by Cryptosporidium spp. (p = 0.0006) and G. duodenalis (p = 0.00001), respectively. Sequence analyses identified host-adapted Cryptosporidium canis (n = 4, one of them belonging to novel subtype XXe2) and G. duodenalis assemblages C (n = 1) and D (n = 3) in dogs. In cats the zoonotic C. parvum (n = 5) was more prevalent than host-adapted C. felis (n = 1). Household dogs had a limited (but not negligible) role as source of human giardiasis and cryptosporidiosis, but the unexpected high frequency of zoonotic C. parvum in domestic cats might be a public health concern. This is the first molecular-based description of Cryptosporidium spp. infections in cats in the African continent to date. Molecular epidemiological data provided here can assist health authorities and policy makers in designing and implementing effective campaigns to minimize the transmission of enteric protists in Egypt.

Keywords: enteric parasites, epidemiology, zoonoses, genotyping, small subunit ribosomal RNA gene, 60 kDa glycoprotein

1. Introduction

Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia duodenalis, Enterocytozoon bieneusi, and Blastocystis sp. are common zoonotic protists able to cause diarrhea and other gastrointestinal disorders in a wide range of animal species including humans (1–3). Human infection outcomes vary largely from asymptomatic to severe manifestations and even death. The most frequent clinical signs are abdominal discomfort, anorexia, acute and chronic diarrhea, nausea, and weight loss. Fever, vomiting, and bloody stool are less common (4–6). Extraintestinal manifestations including urticaria and other allergic diseases have also been reported for some of them (7). All four pathogens are fecal-orally transmitted after accidental ingestion of their transmissive stages (cysts, oocysts, spores) directly through contact with infected humans or animals or indirectly via consumption of contaminated water or fresh produce (8, 9).

Cryptosporidium spp., G. duodenalis, Blastocystis sp., and E. bieneusi display a large intra-species genetic diversity with marked differences in host specificity, range, zoonotic potential and even pathogenicity (10–12). Dogs and cats are commonly infected with Cryptosporidium spp. and G. duodenalis (13, 14), being primarily infected by host-adapted species/genetic variants including Cryptosporidium canis and Cryptosporidium felis and G. duodenalis assemblages C, D, and F. Despite the risk of zoonotic transmission of Cryptosporidium spp. and G. duodenalis from domestic dogs and cats is typically regarded as low (15–17), the sporadic but constant reporting of human infections caused by canine- and feline-adapted species/genotypes of these pathogens suggest that the role of dogs and cats as sources of human cryptosporidiosis and giardiasis should not be overlooked (18, 19).

The stramenopile Blastocystis sp. is a highly polymorphic protozoal parasite of uncertain pathogenicity commonly detected in fecal samples of humans and several other animal species. The parasite encompasses at least 36 subtypes (ST; ST1-ST17, ST21, ST23-ST40) (11, 20, 21). Blastocystis sp. is typically reported at relatively low (7%–9%) carriage rates in dogs and cats globally (22). Both host species have been shown to carry zoonotic STs including ST1–8, ST10, and ST14 (22), although the occurrence of zoonotic transmission events seems rare (23). Furthermore, E. bieneusi is an obligate intracellular fungus-like parasite with high genetic diversity among mammalian and avian hosts (24). Nearly 600 genotypes have been described within E. bieneusi (12), of which zoonotic genotypes A, BEB6, D, and TypeIV have been found circulating in domestic dogs and cats (25).

Domestic dogs and cats can carry a large variety of bacterial, viral, and parasitic (including protist) pathogens which can be transmitted to humans through bites, scratches, saliva, urine, feces, or contaminated surfaces. Therefore, understanding the frequency and molecular diversity of these pathogens is important to assess their zoonotic potential and public health relevance. In Egypt, information on the epidemiology of intestinal protist species of public and veterinary health relevance in canine and feline populations is scarce. Most of the studies conducted to date were based on conventional microscopy as screening method, and only few assessed the frequency and diversity of species/genotypes at the molecular level (Table 1) (26–39). It is therefore essential to conduct periodical surveys to provide updated information on the current status of these pathogens in domestic animals, which might be helpful to reduce the risk of potential zoonotic transmission events to humans. Under this approach, this molecular study investigated the occurrence, genetic diversity, and zoonotic potential of Cryptosporidium spp., G. duodenalis, Blastocystis sp., and E. bieneusi infection in domestic dogs and cats in three geographical areas of Egypt.

Table 1.

Frequency and genetic diversity of Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia duodenalis, Enterocytozoon bieneusi, and Blastocystis sp. infections reported in canine and feline populations in Egypt, 1995–2022.

| Pathogen | Host | Sample size (n) | Detection method | Prevalence (%) | Species (n) | Genotype (n) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cryptosporidium spp. | Dog | 50 | CM | 34.0 | – | – | (26) |

| 50 | PCR | 24.0 | C. parvum (5) | ND | |||

| Dog | 395 | CM | 10.1 | – | – | (27) | |

| Dog | 130 | CM | 5.4 | – | – | (28) | |

| Dog | 60 | CM | 1.7 | – | – | (29) | |

| Dog | 20 | CM, PCR | 50.0 | C. parvum (2) | ND | (30) | |

| Dog | 27 | CM | 18.5 | – | – | (31) | |

| Dog | 27 | CM | 11.1 | – | – | (32) | |

| Dog | 25 | CM | 12.0 | – | – | (33) | |

| Dog | 685 | CM | 3.8 | – | – | (34) | |

| Giardia duodenalis | Dog | 986 | CM, PCR | 8.5 | – | D (4) | (35) |

| Dog | 395 | CM | 0.5 | – | – | (27) | |

| Doga | 120 | CM | 1.7 | – | – | (29) | |

| Dogb | 60 | 31.7 | – | – | |||

| Dog | 685 | CM | 8.3 | – | – | (34) | |

| Dog | 27 | CM | 14.8 | – | – | (31) | |

| Cat | 113 | CM | 2.0 | – | – | (36) | |

| Enterocytozoon bieneusi | Dog | 108 | CM, PCR | 33.3 | – | – | (37) |

| Cat | 104 | CM, PCR | 23.1 | – | – | ||

| Blastocystis sp. | Dog | 144 | Culture, PCR | 0.0 | – | – | (38) |

| Dog | 21 | Culture, PCR | 0.0 | – | – | (39) | |

| Dog | 130 | CM | 3.1 | – | – | (28) | |

| Cat | 155 | PCR | 2.6 | ST3 (1), ST14 (3) | (38) | ||

| Cat | 8 | Culture, PCR | 0.0 | – | – | (39) |

CM, Conventional microscopy.

Police dog.

Domestic dog.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Ethical considerations

The animal study protocol used in the present survey was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Sohag University (Egypt) on 01.12.2019.

2.2. Study area and sample collection

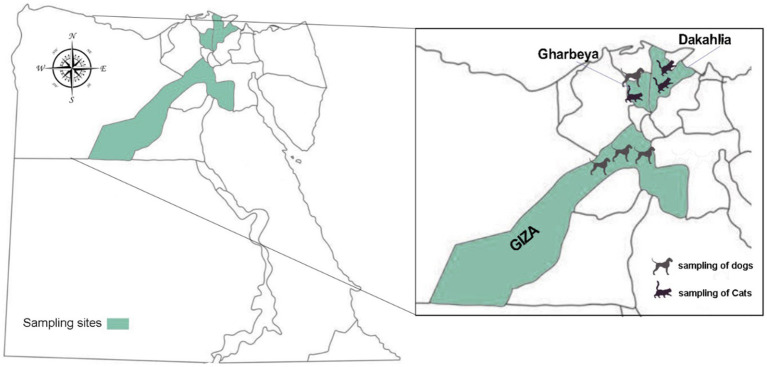

This is a prospective, cross-sectional study conducted during July–December 2021 in three Egyptian governorates: Dakahlia, Gharbeya, and Giza (Figure 1). A total of 352 individual fecal samples were collected from apparently healthy household dogs (n = 218) and cats (n = 134) after requesting and obtaining sampling permission from their owners. The term “household” was used to refer to those domestic animals kept in or about a dwelling house. Canine specimens were collected in Gharbeya, and Giza, whereas feline specimens were collected in Dakahlia and Gharbeya. The samples were collected freshly from the rectum of examined animals, placed into sterile plastic containers with 70% ethanol as preservative, and coded by a unique identifier. All fecal specimens included in this study were formed. Basic epidemiological data including the sex, age, and breed of the animal and the date and geographical location of sampling sites were gathered and entered into an Excel spreadsheet. Collected fecal samples were transported in refrigerated boxes to the Laboratory of Zoonoses, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Sohag University (Egypt) and kept at 4°C. All collected samples where then shipped to the Parasitology Reference and Research Laboratory of the National Centre for Microbiology (Majadahonda, Spain) for downstream molecular testing.

Figure 1.

Map of Egypt showing the geographical location of the three governorates where sampling was conducted.

2.3. DNA extraction and purification

The genomic DNA was extracted from a portion (about 200 mg) of each fecal sample using the QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines, except that samples mixed with InhibitEX buffer were incubated for 10 min at 95°C. Extracted and purified DNA samples were then eluted in 200 μL of PCR-grade water and stored at 4°C until molecular analysis. The maximum time elapsed between sample collection and DNA extraction and purification was 20 weeks.

2.4. Molecular detection and characterization of Cryptosporidium spp.

Detection of Cryptosporidium spp. was conducted by a nested PCR protocol targeting a 587-bp fragment of the small subunit of the ribosomal RNA (ssu rRNA) gene of the parasite (40). Subtyping tools based on the amplification of partial sequences of the 60-kDa glycoprotein (gp60) gene were used to ascertain intra-species genetic diversity in samples that tested positive for C. parvum (41), C. canis (42), and C. felis (43) by ssu-PCR.

2.5. Molecular detection and characterization of Giardia duodenalis

For the identification of Giardia duodenalis, a real-time PCR (qPCR) protocol was used to amplify a 62-bp fragment of the ssu RNA gene of the parasite (44). Samples that yielded cycle threshold (CT) values < 32 were re-assessed using a sequence-based multilocus genotyping (MLST) scheme targeting the genes encoding for the glutamate dehydrogenase (gdh), β-giardin (bg), and triose phosphate isomerase (tpi) proteins to assess G. duodenalis molecular diversity at the sub-assemblage level. A 432-bp fragment of the gdh gene was amplified using a semi-nested PCR (45), while 511 and 530-bp fragments of the bg and tpi genes, respectively, were amplified with nested PCRs (46, 47).

2.6. Molecular detection of Enterocytozoon bieneusi

To identify E. bieneusi, a nested PCR protocol was used to amplify the ITS region as well as portions of the flanking large and small subunit of the ribosomal RNA gene as previously described (48). This procedure yielded final PCR product of 390 bp.

2.7. Molecular detection of Blastocystis sp.

Blastocystis sp. were detected by a direct PCR targeting a 600-bp fragment of the ssu rRNA gene of the parasite as described elsewhere (49).

2.8. PCR and gel electrophoresis standard procedures

Detailed information on the PCR cycling conditions and oligonucleotides used for the molecular identification and/or characterization of the protozoan parasites investigated in the present study is presented in Supplementary Tables 1, 2, respectively. The qPCR protocol described above was carried out on a Corbett Rotor Gene™ 6,000 real-time PCR system (QIAGEN). Reaction mixes included 2× TaqMan® Gene Expression Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, CA, United States). All the direct, semi-nested, and nested PCR protocols described above were conducted on a 2,720 Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems, CA, United States). Reaction mixes always included 2.5 units of MyTAQ™ DNA polymerase (Bioline GmbH, Luckenwalde, Germany), and 5–10 μL MyTAQ™ Reaction Buffer containing 5 mM dNTPs and 15 mM MgCl2.

2.9. Sequence analyses

All amplicons of the expected size were directly sequenced in both directions with the appropriate internal primer sets (see Supplementary Table 2) in 10 μL reactions using Big Dye™ chemistries and an ABI 3730xl sequencer analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Raw sequences were assembled using Chromas Lite version 2.1 software1 and aligned using ClustalW implemented in MEGA version 11 (50). The generated consensus sequences were compared with reference sequences deposited at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) using the BLAST tool.2 Representative nucleotide sequences generated in the present study were deposited in the GenBank public repository database under accession numbers OQ778995–OQ779000 and OQ787086 (Cryptosporidium spp.) and OQ787087–OQ787091 (G. duodenalis).

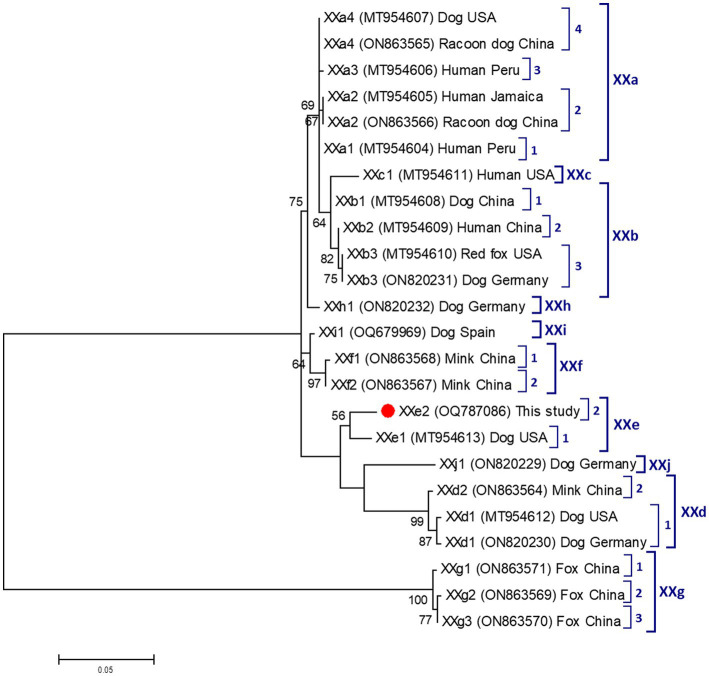

2.10. Phylogenetic analyses

To analyze the phylogenetic relationship among various subtype families of C. canis, a maximum-likelihood tree was constructed using MEGA version 11 (50), based on substitution rates calculated with the general time reversible model and gamma distribution with invariant sites (G + I). Bootstrapping with 1,000 replicates was used to determine support for the clades (42).

2.11. Statistical analyses

The potential association between parasitic infections and the different individual risk variables (geographical location, sex, age, and breed) considered was assessed using the Fisher’s exact test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Analysis were conducted on the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25 software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, United States).

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of parasites

The overall prevalences of Cryptosporidium spp. and G. duodenalis in dogs were 1.8% [4/218, 95% Confidence Interval (95% CI): 0.5–4.6] and 38.5% (84/218, 95% CI: 32.0–45.3), respectively. The overall prevalences of Cryptosporidium spp. and G. duodenalis in cats were 6.0% (8/134, 95% CI: 2.6–11.4) and 32.1% (43/134, 95% CI: 24.3–40.7). All canine and feline fecal samples analyzed tested negative for E. bieneusi and Blastocystis sp.

Dogs from Giza governorate were significantly more infected by G. duodenalis than their counterparts in Gharbeya governorate (p = 0.0006; Table 2). Cats from Dakahlia governorate were more likely to harbor infections by G. duodenalis than cats from Gharbeya governorate (p = 0.00001; Table 3). Sex, age, and breed did not affect the distribution of Cryptosporidium spp. in the investigated canine and feline populations. However, Persian cats were more likely to be infected by G. duodenalis than their counterparts from other breeds (Tables 2, 3).

Table 2.

Distribution of Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia duodenalis infections according to geographical origin, sex, age, and breed of examined dogs (n = 218).

| Cryptosporidium spp. | Giardia duodenalis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Total (n) | Infected (n) | % | p-value | Infected (n) | % | p-value |

| Geographical origin | |||||||

| Giza | 198 | 4 | 2.0 | 1 | 83 | 41.9 | 0.0006 |

| Gharbeya | 20 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5 | ||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 108 | 2 | 1.9 | 1 | 43 | 39.8 | 0.7809 |

| Female | 110 | 2 | 1.8 | 41 | 37.3 | ||

| Age (years) | |||||||

| ≤2 | 57 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.5749 | 24 | 42.1 | 0.5302 |

| >5 | 161 | 4 | 2.5 | 60 | 37.3 | ||

| Breed | |||||||

| Mixed | 196 | 4 | 2.0 | 1 | 83 | 42.3 | 0.0527 |

| Siberian husky | 12 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| German shepherd | 6 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 16.7 | ||

| Havanese | 1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Pit bull | 1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Shih tzu | 1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Yorkshire | 1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

Statistically significant values are highlighted in bold.

Table 3.

Distribution of Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia duodenalis infections according to geographical origin, sex, age, and breed of examined cats (n = 134).

| Cryptosporidium spp. | Giardia duodenalis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Total (n) | Infected (n) | % | p-value | Infected (n) | % | p-value |

| Geographical origin | |||||||

| Gharbeya | 70 | 2 | 2.9 | 0.1512 | 6 | 8.6 | <0.00001 |

| Dakahlia | 64 | 6 | 9.4 | 37 | 57.8 | ||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 59 | 2 | 3.4 | 0.4652 | 22 | 37.3 | 0.2692 |

| Female | 75 | 6 | 8.0 | 21 | 28.0 | ||

| Age (months) | |||||||

| ≤6 | 38 | 4 | 10.5 | 0.2224 | 17 | 44.7 | 0.0645 |

| >6 | 96 | 4 | 4.2 | 26 | 27.1 | ||

| Breed | |||||||

| Mixed | 47 | 1 | 2.1 | – | 4 | 8.5 | – |

| Persian | 42 | 4 | 9.5 | 0.1842 | 23 | 54.8 | <0.00001 |

| Egyptian Mau | 40 | 2 | 5.0 | 0.6761 | 14 | 35.0 | 0.0810 |

| Himalayan | 5 | 1 | 20.0 | 0.3037 | 2 | 40.0 | >0.9 |

Statistically significant values are highlighted in bold.

Regarding co-infections, 75% (3/4) of dogs and 66.7% (4/6) of cats infected with Cryptosporidium spp. had concomitant infections with G. duodenalis.

3.2. Molecular characteristics of Cryptosporidium isolates

All four canine isolates that yielded amplicons of the expected size in ssu-PCR were successfully genotyped and assigned to host-specific C. canis by sequence analyses (Table 4). Three of them were identical to GenBank reference sequence AF112576, whereas the fourth differed from it by a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) at position 646. Only a single isolate could be molecularly characterized at the gp60 locus. Sequence analysis confirmed the presence of C. canis subtype family XXe. The obtained nucleotide sequence differed from reference sequence MT954613 (named as XXe1) by 10 SNPs including an AGA insertion at position 226 (Table 4). We named this novel sequence as XXe2 in agreement with the established nomenclature for Cryptosporidium subtype families (51).

Table 4.

Frequency and molecular diversity of Cryptosporidium spp. identified in the canine and feline populations investigated in the present study.

| Host | Parasite species | Genotype | Subtype | No. isolates | Locus | Reference sequence | Stretch | Single nucleotide polymorphisms | GenBank ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dog | C. canis | – | – | 3 | ssu rRNA | AF112576 | 527–1,021 | None | OQ778995 |

| – | – | 1 | ssu rRNA | AF112576 | 529–1,017 | A646W | OQ778996 | ||

| XX | XXe2 | 1 | gp60 | MT954613 | 4–677 | A16G, C206T, C210T, C211T, A216G, C223G, T226G, 226InsAGA, T277C, A506G | OQ787086 | ||

| Cat | C. felis | – | – | 1 | ssu rRNA | AF108862 | – | None | OQ778997 |

| C. parvum | – | – | 1 | ssu rRNA | AF112571 | 533–1,026 | A546R, A646G, T649G, 686_689DelTAAT, T693A, A706R | OQ778998 | |

| – | – | 3 | ssu rRNA | AF112571 | 573–991 | A646G, T649G, 686_689DelTAAT, T693A | OQ778999 | ||

| – | – | 1 | ssu rRNA | AF112571 | – | A646G, T649G, 686_689DelTAAT, T693A, C761Y | OQ779000 |

Del, Deletion; gp60, 60 kDa glycoprotein; Ins, Insertion; R, A/G; ssu rRNA, Small subunit ribosomal RNA; W, A/T.

Figure 2 shows the maximum-likelihood tree generated with representative sequences of the nine C. canis subtype families (XXa, XXb, XXc, XXd, XXe, XXf, XXg, XXh, and XXi) described to date. As expected, our XXe2 isolate formed a distinct cluster with the only member (XXe1) known to belong to subtype family XXe. According to the topology of the generated tree, subtype families XXd and XXe were phylogenetically distant to the other six.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic relationship among nine Cryptosporidium canis subtype families (XXa–XXi) revealed by a maximum likelihood analysis of the partial gp60 gene. Substitution rates were calculated by using the general time reversible model. Numbers on branches are percent bootstrapping values over 50% using 1,000 replicates. The filled red circle indicates the nucleotide sequence generated in the present study.

All six feline isolates that yielded amplicons of the expected size in ssu-PCR were successfully genotyped (Table 4). One of them was identified as C. felis and its nucleotide sequences showed 100% identity with reference sequence AF108862. The remaining five isolates corresponded to different genetic variants of the bovine genotype of C. parvum (AF112571). These five nucleotide sequences differed from AF112571 by 4–6 SNPs and all of them included the distinctive TAAT deletion at position 689 (Table 4). None of the isolates assigned to C. felis or C. parvum could be amplified at the gp60 locus.

3.3. Molecular characteristics of Giardia duodenalis isolates

Giardia duodenalis qPCR-positive samples generated CT values that ranged from 25.3 to 38.8 (median: 33.8; SD: 3.5) in canine samples, and from 29.2 to 40.4 (median: 36.1; SD: 2.2) in feline samples. A total of 41 fecal DNA samples with CT values ≤ 32 (37 canine, 4 feline) were subjected to MLST analyses.

Among the 37 canine DNA isolates analyzed by MLST, four were successfully genotyped at the gdh and/or bg loci. Two isolates were amplified at the gdh locus only, one isolate was amplified at the bg locus only, and the remaining isolate was amplified at both loci. None of the 37 DNA isolates of canine origin could be genotyped at the tpi locus. Sequence analyses revealed the presence of canine-adapted assemblages C and D at equal (50%, 2/4 each) proportions (Table 5). At the gdh locus, the two isolates identified as assemblage C differed from reference sequence U60984 by a single SNP. The isolate assigned to assemblage D differed from reference sequence U60986 by four SNPs. Of the two isolates amplified at the bg locus and assigned to the assemblage D, one was identical to reference sequence AY545647, whereas the remaining one differed from it by a single SNP (Table 5). All four feline samples positive for G. duodenalis by qPCR failed to be amplified at the three loci (gdh, bg, and tpi) used for genotyping purposes.

Table 5.

Frequency and molecular diversity of Giardia duodenalis identified in the canine population investigated in the present study.

| Assemblage | Sub-assemblage | No. isolates | Locus | Reference sequence | Stretch | Single nucleotide polymorphisms | GenBank ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | – | 1 | gdh | U60984 | 76–491 | G276A | OQ787087 |

| – | 1 | gdh | U60984 | 76–491 | G282A | OQ787088 | |

| D | – | 1 | gdh | U60986 | 67–491 | C132T, T240C, T429C, G441A | OQ787089 |

| D | – | 1 | bg | AY545647 | 112–572 | None | OQ787090 |

| – | 1 | bg | AY545647 | 102–590 | A201G | OQ787091 |

bg, β-giardin; gdh, Glutamate dehydrogenase.

4. Discussion

Domestic dogs and cats can be a source of human infection by a wide diversity of viral, bacterial, parasitic, and fungal pathogens (52, 53). Those with unrestricted access to the outdoors might be at higher risk of pathogen exposure and represent overlooked reservoirs of zoonotic agents (54). Therefore, elucidation of the epidemiology and public health importance in these pathogens requires the use of genotyping and subtyping tools (14). Under these premises, this molecular-based study evaluated the occurrence and molecular diversity of four of the most common diarrhea-causing enteric protist parasites (Cryptosporidium spp., G. duodenalis, E. bieneusi, and Blastocystis sp.) in canine and feline populations in Egypt, with a special interest in assessing their zoonotic potential. The main strengths of the survey include (i) the use of a large sample size, (ii) the coverage of three different geographical regions, (iii) the use of highly sensitive PCRs as screening methods, and (iv) the use of specific PCR protocols for genotyping/subtyping purposes. Molecular information on the investigated protist species is particularly scarce in Egyptian animal populations in general and dogs and cats in particular. The study expands and complements information already provided by our research team on the epidemiology of enteric protists of public veterinary relevance in livestock species including buffaloes, cattle, and dromedary camels (55, 56).

Cryptosporidium spp. infections in Egyptian canine populations have been previously reported in the range of 2%–50% (Table 1) by conventional microscopy examination. In the only molecular-based study conducted to date, a prevalence of 24% (12/50) was found in household dogs in Sharkia Province (26). These highly variable prevalence rates are likely the reflection of changing epidemiological scenarios with differences in reservoir host populations, parasite´ strains, environmental and care conditions, sources of infection, and transmission pathways. This seems to be also the case of the present study, were Cryptosporidium spp. were detected at low rates (2%) in dogs from Giza governorate, but not in dogs from Gharbeya governorate. Our molecular analyses confirmed the presence of canine-adapted C. canis as the only Cryptosporidium species circulating in the surveyed dog population. This is in contrast with the evidence available in the country, where C. parvum was previously identified in five household dogs in Sharkia Province (26), and in two puppies with diarrhea in Qalubiya governorate (30). An asset of the present study is the use of a recently developed subtyping tool based on the amplification of partial sequences of the highly variable gp60 gene to ascertain subtype families within C. canis (42). This methodology has allowed the identification of nine (XXa to XXi) subtype families of C. canis in a variety of animal hosts including dogs, foxes, minks, and racoon dogs, in addition to humans (42, 57, 58). The finding of C. canis in a number of human isolates suggests that this species might represent a public health concern for vulnerable populations such as children and immunocompromised individuals. In our study we managed to subtype one of the four C. canis isolates, which was assigned to novel subtype XXe2. This result contributes to expand our knowledge on the genetic diversity and host range of this Cryptosporidium species.

Our study represents the first PCR-based description of Cryptosporidium infections in domestic cats in Africa. Using molecular methods, feline cryptosporidiosis has been documented at prevalence rates of 8%–13% in the Americas including United States, of 1%–12% in Asia (mainly China), of 2%–10% in Australia, and of 5%–7% in Europe (14). The prevalence rate found in our feline population (6.0%) falls well within the range of those figures reported globally. Our molecular analyses provided interesting data. Unexpectedly, C. parvum was far more prevalently found than feline-adapted C. felis (83.3% vs. 16.7%). This is in spite of Cryptosporidium felis is known to be the dominant species in cats globally (14), although other Cryptosporidium species including C. parvum (59, 60), C. muris (61, 62), and C. ryanae (62) have been sporadically reported in domestic cats. Our sequence analyses revealed that all five C. parvum isolates corresponded to genetic variants of the bovine genotype of the parasite (63), known to have a loose host specificity and therefore a clear zoonotic potential (64). The bovine genotype of C. parvum accounts for 43%–100% of confirmed bovine cryptosporidiosis cases in cattle in Egypt (65–69). We hypothesize that the high proportion of feline infections by C. parvum detected in our feline population can be the result of cross-species transmission between cattle and domestic cats sharing habitats under high infection pressure conditions. Examples of such events have been reported in other studies (70).

Available microscopy-based epidemiological data have demonstrated the occurrence of G. duodenalis in 1%–32% of the canine populations investigated in Egypt (Table 1). None of these studies used PCR as screening method. In the present survey we found a higher G. duodenalis prevalence of 38.5%. This was an expected result, as qPCR has a superior diagnostic performance compared with microscopy (13). As in the case of Cryptosporidium canine infections, large differences in G. duodenalis prevalence rates were observed between geographical areas, with the bulk of the infections (99%) coming from the Giza governorate. Potential explanations for this finding are the higher number of samples collected in this governorate compared with those from Gharbeya, differences in animal care and wellbeing standards and even local variations in the epidemiology of the parasite including sources of infection and transmission pathways (71). Remarkably, 56% (47/84) of the canine cases of giardiasis had qPCR CT values > 32, suggestive of light infections. This fact might also explain the limited number of G. duodenalis isolates successfully subtyped at the gdh and/or bg loci. The four G. duodenalis isolates characterized corresponded to canine-adapted assemblages C and D. These results are in agreement with those reporting assemblage D in four microscopy-positive household dogs visiting private pet clinics in different Egyptian governorates (35).

In the only available survey investigating the presence of G. duodenalis in domestic cats in Egypt, the presence of the parasite was identified by conventional microscopy in 14.8% of the animals examined (31). The global prevalence of feline giardiasis has been estimated at 2.3% (5,807/248,195) in a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence studies (n = 68) from stool samples using a variety of diagnostic methods including light microscopy, IFA, ELISA, and PCR (13). We found a much higher prevalence of 32.1% using a highly sensitive qPCR assay. Unfortunately, 90.7% (39/43) of the feline samples positive for G. duodenalis by this method yielded CT values > 32, precluding us to determine the subtype of these isolates at the gdh, bg, and/or tpi loci.

In this study, E. bieneusi and Blastocystis sp. were undetected in the investigated canine and feline populations. These results are in contrast with those previously reported in Egypt. For instance, microsporidial spores were identified by microscopy examination of stained smears in 33.3 and 23.1% of canine and feline fecal samples, respectively (37). Subsequent nucleotide sequence analyses confirmed the presence of E. bieneusi and E. intestinalis in these host species. On the other side, Blastocystis sp. colonization/infection has been detected at low rates in domestic dogs by conventional microscopy (3.1%) and cats by PCR (2.6%) (28, 38), although other surveys failed to identify the presence of the protist using culture and PCR methods (38, 39).

Taking together, molecular subtyping data generated in the present study indicate that domestic dogs and cats are primarily infected with host-adapted species including C. canis and G. duodenalis assemblages C and D in the case of dogs and C. felis in the case of cats. These genetic variants are considered of limited, but by no means negligible, zoonotic potential, as all of them have been sporadically found in human cases of giardiasis and cryptosporidiosis (10, 64, 72). The exception of this general rule is the unusual high proportion of zoonotic C. parvum infections detected in cats, a finding that represents a public health concern and should be further investigated. It should be noted that, out of 56 molecular studies in African countries, C. parvum ranked second after C. hominis as the most prevalent Cryptosporidium species circulating in humans (71).

Our results showed that canine and feline populations from Gharbeya governorate harbored lower parasitic prevalence rates than their counterparts from Dakahlia and Giza governorates. These discrepancies might be attributed to differences in sample size or the sanitary conditions under which the animals were kept (71). This study has some methodological limitations that should be taken into consideration when interpreting the obtained results and the conclusions reached. First, sample size varied among sampling areas, potentially biasing the accuracy of the statistical analyses conducted. Second, sample storage and transportation conditions might have altered the quality and quantity of available parasitic DNA, compromising the performance of the molecular methods used. Finally but not least, suboptimal amount of parasitic DNA might have hampered the PCR methods used for subtyping purposes, all of them based on the amplification of single copy genes including gdh, bg, and tpi (for G. duodenalis) or gp60 (for Cryptosporidium spp.).

5. Conclusion

This is one of the few molecular-based epidemiological surveys assessing the role of domestic dogs and cats as potential reservoirs of human infections by diarrhea-causing enteric protist parasites of public veterinary health relevance in Egypt. The main contribution of the study to the field include: (i) the confirmation that G. duodenalis, and to a lesser extent, Cryptosporidium spp. infections are common in household dogs and cats, (ii) the first description of the occurrence and molecular diversity of Cryptosporidium spp. infections in domestic cats in Africa, (iii) dogs are infected by canine-adapted pathogens, but cats carried an unusual high proportion of infections with zoonotic C. parvum that might represent a public health concern, (iv) the first description of C. canis subtype XXe2, and (v) the confirmation that strict carnivores such as dogs and cats are poor host species for Blastocystis sp. Molecular epidemiological data presented here might be useful for assenting health authorities and policy makers in designing and implementing effective intervention strategies against these zoonotic pathogens in Egypt. Simple and easy to implement measures include adequate hygiene practices (adequate canine and feline waste disposal, regular hand washing) and routine veterinary care are essential to prevent enteric parasite infections and minimize the risk of zoonotic transmission. Further research should explore the role of other domestic and wildlife species as potential reservoirs of human infections by enteric protists.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore; OQ778995–OQ779000, OQ787086, and OQ787087–OQ787091.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Sohag University (Egypt) on 01.12.2019. Written informed consent was obtained from the owners for the participation of their animals in this study.

Author contributions

EE, AGa, AA-O, AGo, SM, YM, and ME collected the samples. EE, PCK, CH-C, and BB conducted laboratory experiments. PCK, AD, and LX conducted sequence analyses. EE, AD, JA, and CH-C conducted statistical analyses. MM and EH secured the funding for conducting sampling and experimental work. EE, DG-B, and DC designed and supervised the experiments. EE and DC wrote and prepared the original draft. EE, AGa, SM, AD, DG-B, LX, and DC wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was partially funded by the Health Institute Carlos III (ISCIII), Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness under project PI19CIII/00029. This study was supported by Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2023R655), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

EE is the recipient of a postdoctoral fellowship funded by the Ministry of the Higher Education of the Arab Republic of Egypt. DG-B is the recipient of a Sara Borrell Research Contract (CD19CIII/00011) funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities. AD is the recipient of a PFIS contract (FI20CIII/00002) funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation and Universities. CH-C is the recipient of a fellowship funded by the Fundación Carolina (Spain) and the University of Antioquia, Medellín (Colombia).

Footnotes

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2023.1229151/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.Hijjawi N, Zahedi A, Al-Falah M, Ryan U. A review of the molecular epidemiology of Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia duodenalis in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Infect Genet Evol. (2022) 98:105212. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2022.105212, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han B, Pan G, Weiss LM. Microsporidiosis in humans. Clin Microbiol Rev. (2021) 34:e0001020. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00010-20, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Popruk S, Adao DEV, Rivera WL. Epidemiology and subtype distribution of Blastocystis in humans: a review. Infect Genet Evol. (2021) 95:105085. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2021.105085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hemphill A, Müller N, Müller J. Comparative pathobiology of the intestinal protozoan parasites Giardia lamblia, Entamoeba histolytica, and Cryptosporidium parvum. Pathogens. (2019) 8:116. doi: 10.3390/pathogens8030116, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han B, Weiss LM. Therapeutic targets for the treatment of microsporidiosis in humans. Expert Opin Ther Targets. (2018) 22:903–15. doi: 10.1080/14728222.2018.1538360, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ajjampur SS, Tan KS. Pathogenic mechanisms in Blastocystis spp.—interpreting results from in vitro and in vivo studies. Parasitol Int. (2016) 65:772–9. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2016.05.007, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kolkhir P, Balakirski G, Merk HF, Olisova O, Maurer M. Chronic spontaneous urticaria and internal parasites--a systematic review. Allergy. (2016) 71:308–22. doi: 10.1111/all.12818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma JY, Li MY, Qi ZZ, Fu M, Sun TF, Elsheikha HM, et al. Waterborne protozoan outbreaks: an update on the global, regional, and national prevalence from 2017 to 2020 and sources of contamination. Sci Total Environ. (2022) 806:150562. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150562, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith H, Nichols RA. Zoonotic protozoa--food for thought. Parassitologia. (2006) 48:101–4. PMID: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ryan UM, Feng Y, Fayer R, Xiao L. Taxonomy and molecular epidemiology of Cryptosporidium and Giardia—a 50 year perspective (1971-2021). Int J Parasitol. (2021) 51:1099–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2021.08.007, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stensvold CR, Clark CG. Pre-empting Pandora's box: Blastocystis subtypes revisited. Trends Parasitol. (2020) 36:229–32. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2019.12.009, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li W, Feng Y, Santin M. Host specificity of Enterocytozoon bieneusi and public health implications. Trends Parasitol. (2019) 35:436–51. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2019.04.004, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bouzid M, Halai K, Jeffreys D, Hunter PR. The prevalence of Giardia infection in dogs and cats, a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence studies from stool samples. Vet Parasitol. (2015) 207:181–202. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2014.12.011, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li J, Ryan U, Guo Y, Feng Y, Xiao L. Advances in molecular epidemiology of cryptosporidiosis in dogs and cats. Int J Parasitol. (2021) 51:787–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2021.03.002, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lucio-Forster A, Griffiths JK, Cama VA, Xiao L, Bowman DD. Minimal zoonotic risk of cryptosporidiosis from pet dogs and cats. Trends Parasitol. (2010) 26:174–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2010.01.004, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Lucio A, Bailo B, Aguilera M, Cardona GA, Fernández-Crespo JC, Carmena D. No molecular epidemiological evidence supporting household transmission of zoonotic Giardia duodenalis and Cryptosporidium spp. from pet dogs and cats in the province of Álava, northern Spain. Acta Trop. (2017) 170:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2017.02.024, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rehbein S, Klotz C, Ignatius R, Müller E, Aebischer A, Kohn B. Giardia duodenalis in small animals and their owners in Germany: a pilot study. Zoonoses Public Health. (2019) 66:117–24. doi: 10.1111/zph.12541, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryan U, Zahedi A. Molecular epidemiology of giardiasis from a veterinary perspective. Adv Parasitol. (2019) 106:209–54. doi: 10.1016/bs.apar.2019.07.002, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ryan U, Zahedi A, Feng Y, Xiao L. An update on zoonotic Cryptosporidium species and genotypes in humans. Animals. (2021) 11:3307. doi: 10.3390/ani11113307, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maloney JG, Molokin A, Seguí R, Maravilla P, Martínez-Hernández F, Villalobos G, et al. Identification and molecular characterization of four new Blastocystis subtypes designated ST35-ST38. Microorganisms. (2022) 11:46. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11010046, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu M, Yao Y, Xiao H, Xie M, Xiong Y, Yang S, et al. Extensive prevalence and significant genetic differentiation of Blastocystis in high- and low-altitude populations of wild rhesus macaques in China. Parasit Vectors. (2023) 16:107. doi: 10.1186/s13071-023-05691-7, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shams M, Shamsi L, Yousefi A, Sadrebazzaz A, Asghari A, Mohammadi-Ghalehbin B, et al. Current global status, subtype distribution and zoonotic significance of Blastocystis in dogs and cats: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Parasit Vectors. (2022) 15:225. doi: 10.1186/s13071-022-05351-2, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paulos S, Köster PC, de Lucio A, Hernández-de-Mingo M, Cardona GA, Fernández-Crespo JC, et al. Occurrence and subtype distribution of Blastocystis sp. in humans, dogs and cats sharing household in northern Spain and assessment of zoonotic transmission risk. Zoonoses Public Health. (2018) 65:993–1002. doi: 10.1111/zph.12522, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santín M, Fayer R. Microsporidiosis: Enterocytozoon bieneusi in domesticated and wild animals. Res Vet Sci. (2011) 90:363–71. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2010.07.014, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dashti A, Santín M, Cano L, de Lucio A, Bailo B, de Mingo MH, et al. Occurrence and genetic diversity of Enterocytozoon bieneusi (Microsporidia) in owned and sheltered dogs and cats in northern Spain. Parasitol Res. (2019) 118:2979–87. doi: 10.1007/s00436-019-06428-1, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gharieb RMA, Merwad AMA, Saleh AA, Abd El-Ghany AM. Molecular screening and genotyping of Cryptosporidium species in household dogs and in-contact children in Egypt: risk factor analysis and zoonotic importance. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. (2018) 18:424–32. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2017.2254, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ibrahim MA, Gihan KA, Aboelhadid SM, Abdel-Rahim MM. Role of pet dogs in transmitting zoonotic intestinal parasites in Egypt. Asian J Anim Vet Adv. (2016) 11:341–9. doi: 10.3923/ajava.2016.341.349 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Awadallah MA, Salem LM. Zoonotic enteric parasites transmitted from dogs in Egypt with special concern to Toxocara canis infection. Vet World. (2015) 8:946–57. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2015.946-957, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahmed WM, Mousa WM, Aboelhadid SM, Tawfik MM. Prevalence of zoonotic and other gastrointestinal parasites in police and house dogs in Alexandria, Egypt. Vet World. (2014) 7:275–80. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2014.275-280 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El-Madawy RS, Khalifa NO, Khater HF. Detection of cryptosporidial infection among Egyptian stray dogs by using Cryptosporidium parvum outer wall protein gene. Bulg J Vet Med. (2010) 13:104–10. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sabry MA, Lotfy HS. Captive dogs as reservoirs of some zoonotic parasites. Res J Parasitol. (2009) 4:115–22. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abdel-Maksoud NM, Ahmed MM. Hygienic surveillance of cryptosporodiosis i n dogs (Canis familiaris) and cats (Felis cattus). Ass Univ Bull Environ Res. (1999) 2:25–34. [Google Scholar]

- 33.El-Hohari AH, Abdel-Latif AM. Zoonotic importance of cryptosporidiosis among some animals at Gharbia Province in Egypt. Indian J Anim Sci. (1998) 67:305–7. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abou-Eisha A, Abdel-Aal A. Prevalence of some zoonotic parasites in dog faecal deposits in Ismailia City. Assiut Vet Med J. (1995) 33:119–26. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abdelaziz AR, Sorour SSG. Prevalence and molecular characterization of Giardia duodenalis assemblage D of dogs in Egypt, and its zoonotic implication. Microbes Infect Chemother. (2021) 1:e1268. doi: 10.54034/mic.e1268 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khalafalla RE. A survey study on gastrointestinal parasites of stray cats in northern region of Nile delta, Egypt. PLoS One. (2011) 6:e20283. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020283, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al-Herrawy AZ, Gad MA. Microsporidial spores in fecal samples of some domesticated animals living in Giza. Egypt Iran J Parasitol. (2016) 11:195–203. PMID: [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naguib D, Gantois N, Desramaut J, Arafat N, Even G, Certad G, et al. Prevalence, subtype distribution and zoonotic significance of Blastocystis sp. isolates from poultry, cattle and pets in northern Egypt. Microorganisms. (2022) 10:2259. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10112259, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mokhtar A, Youssef A. Subtype analysis of Blastocystis spp. isolated from domestic mammals and poultry and its relation to transmission to their in-contact humans in Ismailia governorate, Egypt. Parasitol United J. (2018) 11:90–8. doi: 10.21608/PUJ.2018.16318 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tiangtip R, Jongwutiwes S. Molecular analysis of Cryptosporidium species isolated from HIV-infected patients in Thailand. Tropical Med Int Health. (2002) 7:357–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00855.x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feltus DC, Giddings CW, Schneck BL, Monson T, Warshauer D, McEvoy JM. Evidence supporting zoonotic transmission of Cryptosporidium spp. in Wisconsin. J Clin Microbiol. (2006) 44:4303–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01067-06, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiang W, Roellig DM, Guo Y, Li N, Feng Y, Xiao L. Development of a subtyping tool for zoonotic pathogen Cryptosporidium canis. J Clin Microbiol. (2021) 59:e02474–20. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02474-20, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rojas-Lopez L, Elwin K, Chalmers RM, Enemark HL, Beser J, Troell K. Development of a gp60-subtyping method for Cryptosporidium felis. Parasit Vectors. (2020) 13:39. doi: 10.1186/s13071-020-3906-9, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Verweij JJ, Schinkel J, Laeijendecker D, van Rooyen MA, van Lieshout L, Polderman AM. Real-time PCR for the detection of Giardia lamblia. Mol Cell Probes. (2003) 17:223–5. doi: 10.1016/s0890-8508(03)00057-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Read CM, Monis PT, Thompson RC. Discrimination of all genotypes of Giardia duodenalis at the glutamate dehydrogenase locus using PCR-RFLP. Infect Genet Evol. (2004) 4:125–30. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2004.02.001, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lalle M, Pozio E, Capelli G, Bruschi F, Crotti D, Cacciò SM. Genetic heterogeneity at the beta-giardin locus among human and animal isolates of Giardia duodenalis and identification of potentially zoonotic subgenotypes. Int J Parasitol. (2005) 35:207–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.10.022, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sulaiman IM, Fayer R, Bern C, Gilman RH, Trout JM, Schantz PM, et al. Triosephosphate isomerase gene characterization and potential zoonotic transmission of Giardia duodenalis. Emerg Infect Dis. (2003) 9:1444–52. doi: 10.3201/eid0911.030084, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Buckholt MA, Lee JH, Tzipori S. Prevalence of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in swine: an 18-month survey at a slaughterhouse in Massachusetts. Appl Environ Microbiol. (2002) 68:2595–9. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.5.2595-2599.2002, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scicluna SM, Tawari B, Clark CG. DNA barcoding of Blastocystis. Protist. (2006) 157:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2005.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tamura K, Stecher G, Kumar S. MEGA11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol Biol Evol. (2021) 38:3022–7. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msab120, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xiao L, Feng Y. Molecular epidemiologic tools for waterborne pathogens Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia duodenalis. Food Waterborne Parasitol. (2017) 8-9:14–32. doi: 10.1016/j.fawpar.2017.09.002, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chomel BB. Emerging and re-emerging zoonoses of dogs and cats. Animals. (2014) 4:434–45. doi: 10.3390/ani4030434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baneth G, Thamsborg SM, Otranto D, Guillot J, Blaga R, Deplazes P, et al. Major parasitic zoonoses associated with dogs and cats in Europe. J Comp Pathol. (2016) 155:S54–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2015.10.179, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mendoza Roldan JA, Otranto D. Zoonotic parasites associated with predation by dogs and cats. Parasit Vectors. (2023) 16:55. doi: 10.1186/s13071-023-05670-y, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Elmahallawy EK, Sadek HA, Aboelsoued D, Aloraini MA, Alkhaldi AAM, Abdel-Rahman SM, et al. Parasitological, molecular, and epidemiological investigation of Cryptosporidium infection among cattle and buffalo calves from Assiut governorate, upper Egypt: current status and zoonotic implications. Front Vet Sci. (2022) 9:899854. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.899854, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Elmahallawy EK, Köster PC, Dashti A, Alghamdi SQ, Saleh A, Gareh A, et al. Molecular detection and characterization of Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia duodenalis, and Enterocytozoon bieneusi infections in dromedary camels (Camelus dromedaries) in Egypt. Front Vet Sci. (2023) 10:388. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2023.1139388, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang W, Wei Y, Cao S, Wu W, Zhao W, Guo Y, et al. Divergent Cryptosporidium species and host-adapted Cryptosporidium canis subtypes in farmed minks, raccoon dogs and foxes in Shandong, China. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. (2022) 12:980917. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.980917, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Murnik LC, Daugschies A, Delling C. Cryptosporidium infection in young dogs from Germany. Parasitol Res. (2022) 121:2985–93. doi: 10.1007/s00436-022-07632-2, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sotiriadou I, Pantchev N, Gassmann D, Karanis P. Molecular identification of Giardia and Cryptosporidium from dogs and cats. Parasite. (2013) 20:8. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2013008, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alves MEM, Martins FDC, Bräunig P, Pivoto FL, Sangioni LA, Vogel FSF. Molecular detection of Cryptosporidium spp. and the occurrence of intestinal parasites in fecal samples of naturally infected dogs and cats. Parasitol Res. (2018) 117:3033–8. doi: 10.1007/s00436-018-5986-4, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Santín M, Trout JM, Vecino JA, Dubey JP, Fayer R. Cryptosporidium, Giardia and Enterocytozoon bieneusi in cats from Bogota (Colombia) and genotyping of isolates. Vet Parasitol. (2006) 141:334–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.06.004, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang R, Ying JL, Monis P, Ryan U. Molecular characterisation of Cryptosporidium and Giardia in cats (Felis catus) in Western Australia. Exp Parasitol. (2015) 155:13–8. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2015.05.001, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Slapeta J. Cryptosporidium species found in cattle: a proposal for a new species. Trends Parasitol. (2006) 22:469–74. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2006.08.005, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xiao L. Molecular epidemiology of cryptosporidiosis: an update. Exp Parasitol. (2010) 124:80–9. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2009.03.018, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Amer S, Honma H, Ikarashi M, Tada C, Fukuda Y, Suyama Y, et al. Cryptosporidium genotypes and subtypes in dairy calves in Egypt. Vet Parasitol. (2010) 169:382–6. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.01.017, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Amer S, Zidan S, Adamu H, Ye J, Roellig D, Xiao L, et al. Prevalence and characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. in dairy cattle in Nile River delta provinces, Egypt. Exp Parasitol. (2013) 135:518–23. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2013.09.002, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mahfouz ME, Mira N, Amer S. Prevalence and genotyping of Cryptosporidium spp. in farm animals in Egypt. J Vet Med Sci. (2014) 76:1569–75. doi: 10.1292/jvms.14-0272, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Helmy YA, Von Samson-Himmelstjerna G, Nöckler K, Zessin KH. Frequencies and spatial distributions of Cryptosporidium in livestock animals and children in the Ismailia province of Egypt. Epidemiol Infect. (2015) 143:1208–18. doi: 10.1017/S0950268814001824, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ibrahim MA, Abdel-Ghany AE, Abdel-Latef GK, Abdel-Aziz SA, Aboelhadid SM. Epidemiology and public health significance of Cryptosporidium isolated from cattle, buffaloes, and humans in Egypt. Parasitol Res. (2016) 115:2439–48. doi: 10.1007/s00436-016-4996-3, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cardona GA, de Lucio A, Bailo B, Cano L, de Fuentes I, Carmena D. Unexpected finding of feline-specific Giardia duodenalis assemblage F and Cryptosporidium felis in asymptomatic adult cattle in northern Spain. Vet Parasitol. (2015) 209:258–63. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.02.028, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang X, Wang X, Cao J. Environmental factors associated with Cryptosporidium and Giardia. Pathogens. (2023) 12:420. doi: 10.3390/pathogens12030420, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Squire SA, Ryan U. Cryptosporidium and Giardia in Africa: current and future challenges. Parasit Vectors. (2017) 10:195. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2111-y, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore; OQ778995–OQ779000, OQ787086, and OQ787087–OQ787091.