Abstract

Background:

Parkinson’s disease is a heterogeneous neurodegenerative disorder with distinctive gut microbiome patterns suggesting that interventions targeting the gut microbiota may prevent, slow, or reverse disease progression and severity.

Objective:

Because secretory IgA (SIgA) plays a key role in shaping the gut microbiota, characterization of the IgA-Biome of individuals classified into either the akinetic rigid (AR) or tremor dominant (TD) Parkinson’s disease clinical subtypes was used to further define taxa unique to these distinct clinical phenotypes.

Methods:

Flow cytometry was used to separate IgA-coated and -uncoated bacteria from stool samples obtained from AR and TD patients followed by amplification and sequencing of the V4 region of the 16 S rDNA gene on the MiSeq platform (Illumina).

Results:

IgA-Biome analyses identified significant alpha and beta diversity differences between the Parkinson’s disease phenotypes and the Firmicutes/Bacteroides ratio was significantly higher in those with TD compared to those with AR. In addition, discriminant taxa analyses identified a more pro-inflammatory bacterial profile in the IgA+ fraction of those with the AR clinical subclass compared to IgA-Biome analyses of those with the TD subclass and with the taxa identified in the unsorted control samples.

Conclusion:

IgA-Biome analyses underscores the importance of the host immune response in shaping the gut microbiome potentially affecting disease progression and presentation. In the present study, IgA-Biome analyses identified a unique proinflammatory microbial signature in the IgA+ fraction of those with AR that would have otherwise been undetected using conventional microbiome analysis approaches.

Keywords: 16S RNA gene sequencing, IgA-Biome, microbiome, Parkinson’s disease, Parkinson’s disease clinical subtypes, secretory IgA

INTRODUCTION

Parkinson’s disease is a remarkably heterogeneous neurodegerative condition that affects all levels of the brain-gut axis including the autonomic, central, and enteric nervous symptoms [1, 2]. Highlighting the heterogeneity of Parkinson’s disease are the three clinically different motor phenotypes that have long been recognized in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. These different classifications have been proposed either using empirical categorization or data-driven grouping schemes. Empirical types are usually determined by relevant clinical signs, with motor symptoms being the most commonly used. Motor subtyping creates distinct groups that are easily and rapidly identified in a clinical setting and provides practical information for clinical care but excludes non-motor symptoms. Other classifications, like cluster analyses, include motor and non-motor features, but they are limited by the time and tools needed to collect and analyze the data. The most commonly identified Parkinson’s disease clinical subtypes include tremor-dominant (TD), indeterminate/mixed (ID/MX), and postural instability gait difficulty/akinetic-rigid (PIGD/AR) with TD and PIGD/AR representing the two most common empirical groupings [3– 8]. The PIGD/AR subtype has been referred to as ‘malignant’ due to a more rapid rate of progression [9], cognitive decline [10], higher prevalence of non-motor symptoms, and a shorter response to levodopa therapy [11].

Changes to the gut microbiome occur long before any overt symptoms of Parkinson’s disease manifest, suggesting that Parkinson’s disease etiology may be intimately linked to the makeup of the gut microbiome via its impact on the gut-brain axis also referred to as the gut-brain-enteric microbiota axis [2, 12, 13]. Due to the impact the gut microbiota has on Parkinson’s disease progression, and possibly the nature of the disease subtype that emerges, a fundamental question to our understanding of disease development is identifying factors that modify the gut microbiome. One possible contributor to gut microbiome changes in Parkinson’s disease patients is the nature the secretory immunoglobulin A (SIgA) response to respective taxa in individuals presenting across the Parkinson’s disease spectrum [14– 16]. The collection of SIgA-coated and -uncoated taxa is referred to as the IgA-Biome and many SIgA-coated bacteria exert a homeostatic function in healthy people and are important to gut health [17, 18]. In disease states associated with dysbiosis, including neurodegenerative disorders, the IgA-Biome is diminished and may contribute to disease pathogenesis [19, 20].

Although standard microbiome analyses can identify differential abundances of microbial communities, these analyses do not necessarily reflect the immunological impact of these microbiota. In 2014, Palm et al. characterized the gut IgA-Biome of individuals with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and identified relationships between the gut microbiome and IBD that were not otherwise evident through standard microbiome analyses [21]. Specifically, 35 bacterial species present in both IBD patients and healthy controls were highly coated with SIgA only in those with IBD [21]. Using SIgA-positive and SIgA-negative microbial consortia generated from IBD cases, the authors established that fecal transfer of SIgA-positive microbes to germ-free mice facilitated the development of the IBD phenotype whereas SIgA-negative microbes produced only minimal inflammation [21]. The importance of the gut IgA-Biome has also been observed in malnutrition, where a study of Malawian twins discordant for severe acute undernutrition [22] demonstrated that transfer of the SIgA-bound bacterial consortia from the unhealthy twin induced diet-dependent disruption of the gut epithelium, weight loss, sepsis, and death in mice. These effects were prevented by administering two SIgA-targeted bacterial species isolated from the gut microbiomes of healthy subjects. Together these studies indicate that traditional methods of assessing the disease-associated microbiome may invariably miss key host-microbe relationships and highlight the importance of the IgA-Biome as a unique and measurable signature of disease states that could be exploited both diagnostically and therapeutically while also providing insights into underlying disease mechanisms.

The present study tests the hypothesis that the subset of the gut microbiota targeted by SIgA represents a unique signature across Parkinson’s disease clinical subtypes. Here we report IgA-Biome analysis of the gut microbiota of Parkinson’s disease patients classified as either AR or TD and identify significant differences in alpha and beta diversity between the two clinical subtypes. Additionally, specific species with a pro-inflammatory phenotype (Bilophila wadsworthia, Flavonifractor plautii, and Prevotella disiens) are shown to be associated with the IgA+ compartment of those with the more severe AR subtype compared to the taxa associated with the IgA-Biome of those presenting with the TD clinical subtype. Not only do these studies highlight unique associations of the gut microbiome in the context of Parkinson’s disease phenotypes but they further underscore the importance of IgA-Biome analyses as means of identifying taxa associated with respective disease states.

METHODS

Patient enrollment and tremor dominant and akinetic rigid clinical subtypes

Stool samples collected from 40 subjects with PD enrolled in the study were classified after enrollment into three clinical subtypes: Akinetic Rigid (AR) (n = 11; 6 male and 5 female), Tremor Dominant (TD) (n = 29; 23 male and 6 female), or Mix (MX) (n = 3) (Table 1). The average age between AR and TD patients (73.91 and 72.17 years of age, respectively) and average weeks since diagnosis (291.74 and 224.62, respectively) was not significantly different (Table 1). Due to the low number of MX participants these individuals were not included in the analyses described. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas Health Science Center and informed written consent was obtained from each participant. Stool was collected using a commode specimen collection system (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and a portion of the sample was stored at – 80°C in a 2 ml cryovial until processed for flow cytometry.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics by Parkinson’s disease type (n = 43)

| AR | TD mean (SD) or N(%) |

MX | p | |

| Age (y) | 73.91 | 72.17 | 69.33 | 0.53 |

| Sex | 0.29 | |||

| Female | 5 (45.45) | 6 (20.69) | 1 (33.33) | |

| Male | 6 (54.55) | 23 (79.31) | 2 (66.67) | |

| Weeks since Diagnosis | 291.74 (141.41) | 224.62 (261.66) | 454.86 (327.13) | 0.26 |

AR, Akinetic Rigid; TD, Tremor Dominant.

Sample preparation for flow cytometry

Stool samples were prepared as described previously [23]. Samples were rehydrated for 30 min on ice in sterile filtered, cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) at a concentration of 0.1 g/ml. Respective stool samples (1 ml) were added to Lysing Matrix D tubes (MP Biologicals, Santa Ana, CA), homogenized for 7 s using a BeadBeater (Biospec, Bartlesville, OK) followed by centrifugation at 730 rpm for 15 min, after which 100μl were collected for immunostaining. Each sample was washed 3X with 1 ml cold PBS/1% bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Between washes, samples were centrifuged at 9,230 rpm. 20μl were removed after the first wash and frozen at – 80°C for use as the unsorted control sample also referred to as the presort sample. Phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-IgA was added to respective samples at the concentrations specified by the manufacturers (listed below) for 30 min on ice. Samples were washed 3 times in PBS/1% BSA and after the last wash, samples were resuspended in 1 ml PBS/1% BSA and filtered through a 35μm flow tube strainer cap into the flow tube [23]. All centrifugation steps were carried out in a cold room at 4°C. Samples were maintained on ice until sorted.

Flow sorting of IgA-coated bacteria

Bacteria were incubated with a PE-conjugated mouse anti-human IgA (130-093-128, Miltenyi Biotec Inc., Auburn, CA). Stool samples were sorted on two separate occasions using a BD SORP FACS Ariatrademark II (Special Order Research Product from Beckton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) equipped with forward scatter photomultiplier tube (FSC-PMT) for improved small particle detection, at the Baylor College of Medicine Cytometry and Cell Sorting Core Facility where instruments go through daily QA/QC and follow NIH biosafety standards as described [23]. The instrument was set up for small particle detection using both a forward scatter and side scatter, FSC and SSC, respectively, thresholds to separate signal from background. Scatter voltage settings were determined using FSC height and SSC height parameters to adequately adjust signal over threshold values. FSC-PMT in both area and height was used to verify FSC and SSC threshold settings. Typical singlet gating discrimination was not performed to prevent excluding populations due to variation in scatters of bacteria. To reduce coincident events and sorting error issues, the sample differential was maintained at the lowest setting and the sample threshold rate was decreased by diluting the sample as needed with phosphate buffered saline containing 1% bovine serum albumin. Background fluorescence was established using unlabeled specimens on all samples setting gates on bias to account for a range of autofluorescence. Sorted samples were collected into chilled, pre-labeled epi tubes.

IgA-Biome analyses were conducted on half a million sorted bacteria although some sorts contained fewer bacteria. Sorted samples along with sheath fluid controls were transported on ice and centrifuged at 4°C at 10,000 rpm for 15 min. The majority of the supernatant was aspirated, leaving approximately 100μl and then frozen at – 80°C until processed for 16 S sequencing [21].

16 S RNA gene sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted with the MagAttract PowerSoil DNA kit (Qiagen) following methods adapted from the NIH Human Microbiome Project [24]. The V4 region of the 16 S rDNA gene was amplified by PCR using barcoded primers (515F,806 R) and sequenced on the MiSeq platform (Illumina) via the 2x250 bp paired-end protocol, targeting at least 10,000 reads per sample.

Demultiplexed read pairs were merged using USEARCH v7.0.1090 [25] with the following parameters: merged length≥252 bp, minimum 50 bp overlap with zero mismatches, and truncation quality >5. Merged reads were further filtered against a maximum expected error rate of 0.05, and PhiX sequences were removed. Reads were clustered into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) at a similarity cutoff value of 97% using UPARSE [26] and underwent chimera removal via USEARCH [25]. OTUs were mapped against an optimized version of the SILVA Database v132 [27] containing only sequences from the v4 region of the 16S rDNA gene. To reduce the influence of potential contamination from the sorting process, OTUs identified in at least three of four sheath fluid samples were removed from the dataset if their average relative abundance among presort samples was <25% that of the sheath samples. This resulted in the removal of one OTU representing Acinetobacter. Following removal of putative contaminants, data were rarefied to 1,511 reads per sample (Supplementary Figure 1).

Statistical analysis

Agile Toolkit for Incisive Microbial Analyses 2 (ATIMA2), a stand-alone tool for microbial data exploration, was used as an integrated solution for analyzing and visualizing microbiome data (https://atima.research.bcm) ATIMA2 uses PERMANOVA to evaluate differences in overarching community composition (beta diversity), while comparisons of community dispersion were determined via the Mann-Whitney U test. Alpha diversity analyses were performed in STATA 16 using repeated measures ANOVA and the paired t-test as appropriate. Analysis of percent coated bacteria and comparisons of the Firmicutes/Bacteroides ratios were graphed and analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9 version 9.4.0. Differentially abundant taxa by IgA-bound status were determined via LEfSe [28] using parameters α= 0.05 and minimum LDA = 2.5. LEfSe analysis was limited to taxa identified in at least 10% of samples.

RESULTS

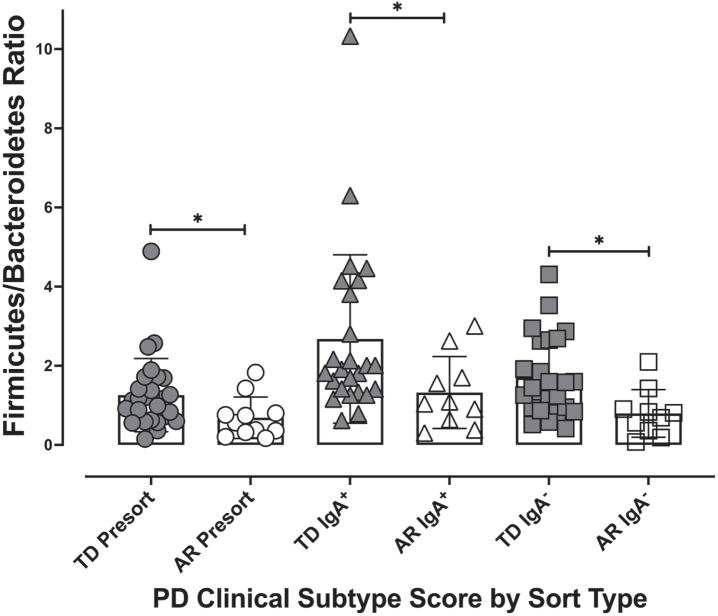

Percent IgA coated bacteria

Parkinson’s disease patients classified into either the AR (n = 11) or TD (n = 29) clinical subtypes were subjected to stool IgA-Biome analysis as described previously [23]. Fluorescently labeled anti-human IgA F(ab)’2 goat anti-human IgA was incubated with stool samples collected from individuals diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease (TD or AR) followed by flow cytometric analysis to separate IgA-coated and -uncoated bacteria [23]. This analysis identified a significant difference (p < 0.0002, Mann-Whitney t-test) in percent IgA coating between individuals in the AR (2.083% ±0.354) and TD (6.373% ±1.526) phenotypes (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Percent IgA-coated bacteria in stool according to Parkinson’s disease clinical subtype. Each dot represents a study participant. Horizontal bars represent the mean±standard error. Mann-Whitney t-test, p < 0.0002.

Alpha and beta diversity across the AR and TD disease phenotypes

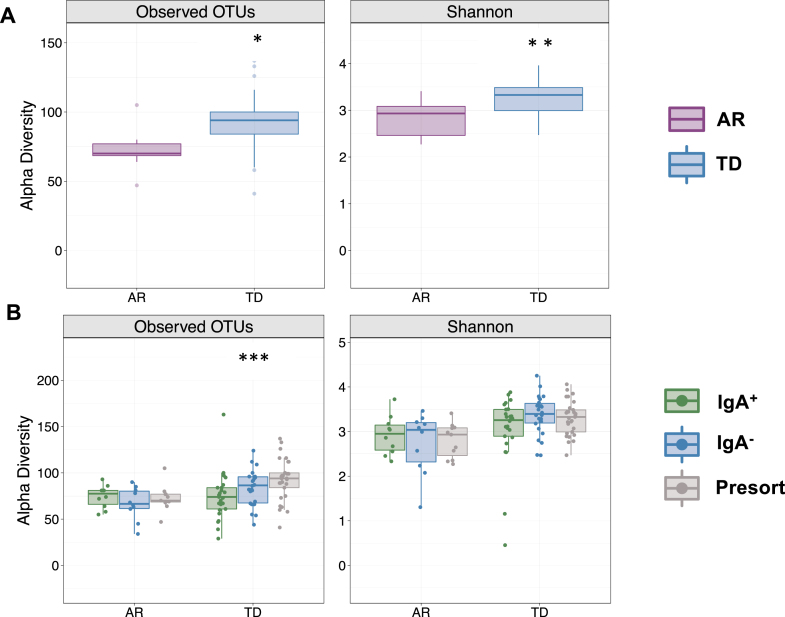

Because disease severity, symptoms, pathology, and gut microbiota composition are vastly different between Parkinson’s patients presenting with either AR or TD [29, 30], we first compared alpha diversity (within sample diversity metric) between Parkinson’s patients presenting with either AR or TD. Those presenting with AR had significantly fewer detectable OTUs paralleled by a significantly reduced Shannon diversity index (Fig. 2A). Comparisons across the IgA-Biome demonstrated that although richness remained the same in those with AR, richness in the TD group increased significantly in a step-wise fashion with the lowest richness in the IgA+ compartment followed by the IgA- compartment and then the presort (unsorted control samples) (Fig. 2B; Kruskal-Wallis false discovery rate [FDR] 0.00898). Shannon diversity index was similar between the AR and TD groups (Fig. 2B). Closer examination identified a significant difference in richness between the IgA+ and IgA– compartments of those with TD (Mann-Whitney FDR-adjusted p = 0.043; Supplementary Figure 2). The number of OTUs and the Shannon diversity index between the IgA– fractions (but not the IgA+ fractions) of those with AR and TD were significantly different (Mann-Whitney FDR-adjusted p = 0.015 and p = 0.0042, respectively; Supplementary Figure 3).

Fig. 2.

IgA-Biome alpha diversity by PD clinical subtype. Box plots depict sample richness (Observed OTU) and evenness (Shannon Diversity Index) among (A) presort only and (B) presort and sorted samples according to IgA-bound status. *p = 0.01 and p = 0.0017 FDR adjusted Mann-Whitley and ***p = 0.00898 FDR adjusted Kruskal-Wallis.

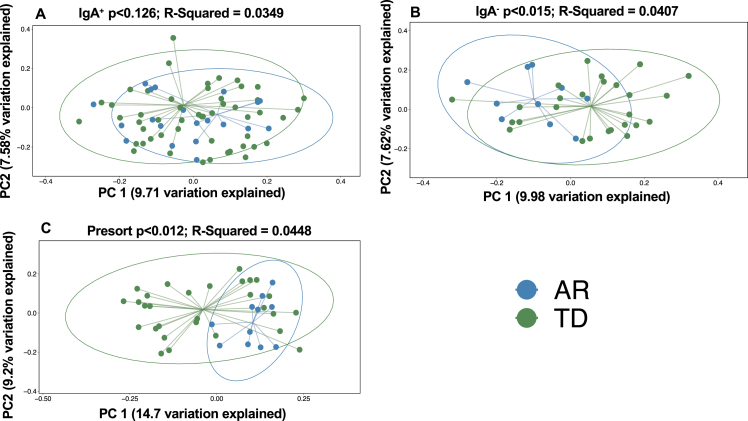

To investigate beta (between sample) diversity of the collective IgA-Biome communities, we visualized unweighted UniFrac dissimilarity that incorporates phylogenetic data to compare samples by principal coordinates analysis (PCoA). More specifically, unweighted UniFrac distance measures differences between sequences from two populations to establish the amount of evolutionary history unique to each population (measured as the fraction of branch length in a phylogenetic tree leading to descendants of one sample or the other but not both) [31]. PCoA plots did not identify a significant difference in the IgA+ (Fig. 3A; p < 0.126) compartment between the AR and TD groups; however, significant differences between those with AR and TD were observed in the IgA– compartment (Fig. 3B; p < 0.015) and unsorted (presort) sample (Fig. 3 C; p < 0.012).

Fig. 3.

Beta diversity analyses of the stool IgA-Biomes of PD individuals classified by their clinical subtype. Beta diversity visualized by principal coordinate analysis measured by unweighted UniFrac. Statistical significance was measured using PERMANOVA.

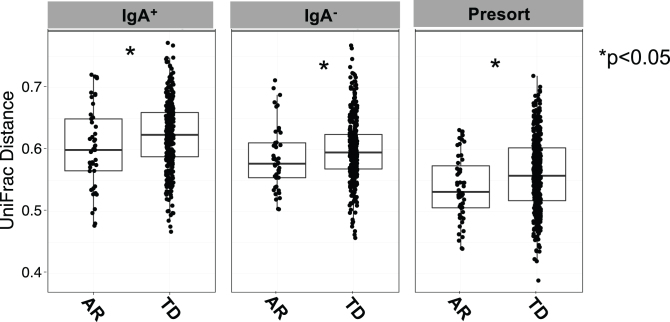

Comparisons across the IgA-Biome of unweighted UniFrac distances between each AR or TD subject revealed significant differences in community composition across all compartments (Fig. 4). That is, the gut microbial communities from AR individuals were significantly less diverse than those with TD (Fig. 4). Alpha and beta diversity analyses of those with AR and TD did not identify any significant differences based on sex (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Box plots depict unweighted UniFrac dissimilarities by IgA-Biome profile according to Parkinson’s disease clinical subtype. UniFrac distances closer to 1 indicated higher community similarity. *p < 0.0385 (IgA+), *p < 0.0442 (IgA–), and *p < 0.0133 (presort) Mann-Whitney t-test.

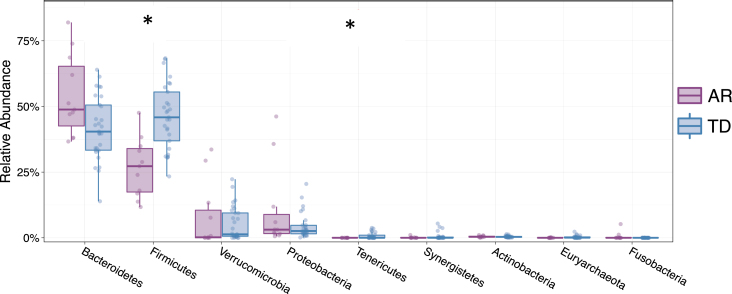

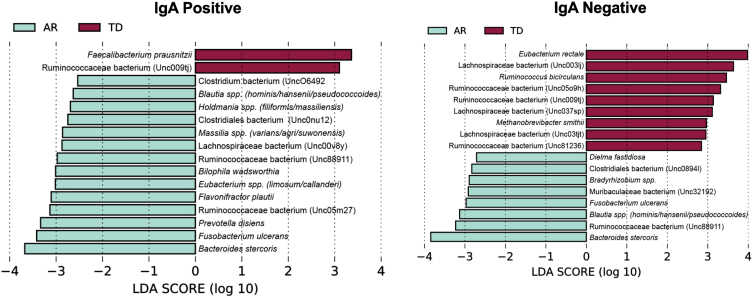

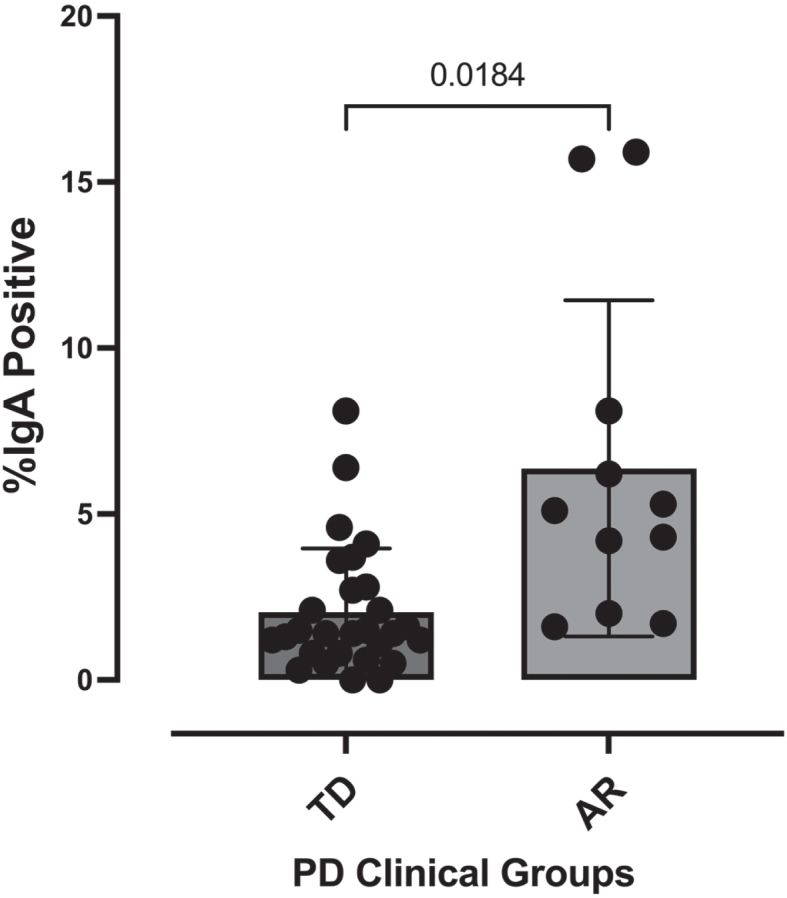

Taxonomy of the IgA-Biome

Examining the relative abundances of the 10 most abundant taxa (phyla) in the unsorted (presort) sample demonstrated that individuals diagnosed with the TD clinical subtype had significantly higher relative abundances of Firmicutes (Mann-Whitney FDR p < 0.00225) and Tenericutes (Mann-Whitney FDR p < 0.0294) compared to those presenting with the AR phenotype (Fig. 5). Although the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio is a common gauge of dysbiosis in obesity, autism and other metabolic disorders in humans [32– 34], a meta-analysis of 10 studies failed to identify significant differences in the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio between Parkinson’s patients and healthy controls [35]. However, because the AR and TD clinical subtype disease manifestations are so distinct, we examined this ratio in this context of these phenotypes. Analysis of the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio across the IgA-Biome revealed that across all compartments, individuals in the TD clinical subclass had significantly higher Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio (Fig. 6). Specifically, the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio in the presort for those with AR and TD was 0.687±0.157 and 1.260±0.174, respectively. In the IgA+ compartment the ratio for those with AR and TD was 1.326±0.287 and 2.678±0.425, respectively and in the IgA– compartment the ratio for those with AR and TD was 0.796±0.190 and 1.7±0.202, respectively (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Relative abundance of phyla from individuals classified as either AR (purple) or TD (blue). Depicted are the 9 phyla present in greatest abundance. The relative abundances Firmicutes (FDR *p < 0.00225) and Tenericutes (FDR *p < 0.0294) were significantly different between Parkinson’s disease individuals classified as either AR or TD. Mann-Whitney t-test.

Fig. 6.

The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio by Parkinson’s disease clinical subtype and IgA coating profile. The Firmicutes/Bacteroides ratio for each individual was calculated for presort, IgA+, and IgA– samples. Individuals classified as TD had significantly higher Firmicutes/Bacteroides ratios than the ratio of those classified as AR across all IgA-Biome compartments. *p < 0.025; Mann-Whitney t-test.

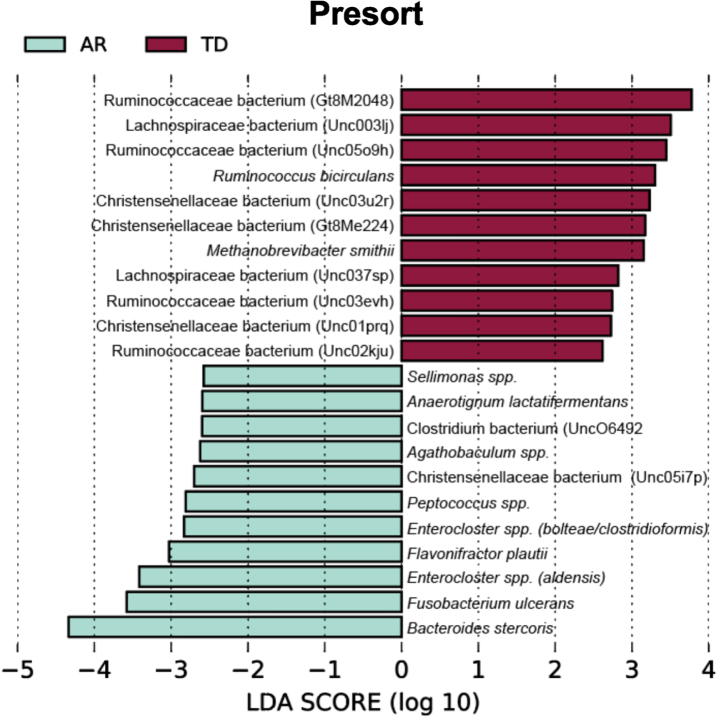

To identify bacterial taxa that discriminate the IgA coated versus uncoated sorting fractions, we used the biomarker discovery tool Linear Discriminant Analysis Effect Size (LEfSe) [23, 36, 37] (Fig. 7). This analysis identified various taxa uniquely associated with the IgA-Biomes of those with the TD and AR Parkinson’s disease subtypes (Fig. 7) and some, e.g., Eubacterium, Prevotella, Blautia, Faecalibacterium, Bilophila, Methanobrevibacter, Bacteroides, and Ruminococcus have been previously been linked to Parkinson’s disease-related dysbiosis [38, 39]. The only unique species identified by LEfSe in the presort samples of those with the AR phenotype was Anaerotgnum lactifermentans and Enterocloster aldensis that to date have not been associated with any human disease states (Fig. 8) [40]. LEfSe analyses of the IgA-Biome and presort samples further distilled Parkinson’s disease phenotypes, including some associations at the species level.

Fig. 7.

LEfSe identifies bacterial biomarkers associated with IgA-coated and uncoated genera across the Parkinson’s disease clinical subtypes. Analyses were conducted using parameters α<0.10 and linear discriminant analysis (LDA) threshold≥2.0.

Fig. 8.

LEfSe identifies bacterial biomarkers associated with Presort samples across the Parkinson’s disease clinical subtypes. Analyses were conducted using parameters α<0.10 and linear discriminant analysis (LDA) threshold≥2.0.

Taxa unique to the presort sample include Ruminococcaceae bacterium (Gt8M2048), Enterocloster spp. (bolteae/clostridioformis), Ruminococcaceae bacterium (Unc03evh), Christensenellaceae bacterium (Unc03u2r), Christensenellaceae bacterium (Gt8Me224), Christensenellaceae bacterium (Unc01prq), Anaerotignum lactatifermentans, Enterocloster spp. (aldensis), Ruminococcaceae bacterium (Unc02kju), Agathobaculum spp., Christensenellaceae bacterium (Unc05i7p), Sellimonas spp., Peptococcus spp (Fig. 8 and Supplementary Figure 4).

Taxa shared between the IgA+ and IgA– fractions include: Ruminococcaceae bacterium (Unc009tj), Blautia spp. (hominis/hansenii), and Ruminococcaceae bacterium (Unc88911); taxa unique to the IgA+ fraction include: Bilophila wadsworthia, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Ruminococcaceae bacterium (Unc05m27), Holdmania spp. (filiformis/massiliensis), Clostridiales bacterium (Unc0nu12), Prevotella disiens, Eubacterium spp. (limosum/callanderi), Lachnospiraceae bacterium (Unc00v8y), and Massilia spp. (varians/agri/suwonensis); and taxa unique to the IgA– fraction include: Eubac-terium rectale, Lachnospiraceae bacterium (Unc03tjt), Ruminococcaceae bacterium (Unc81236), Bradyrhizobium spp., Dielma fastidiosa, Clostridiales bacterium (Unc0894l), and Muribaculaceae bacterium (Unc32192) (Fig. 7 and Supplementary Figure 4).

DISCUSSION

Even before the link between the intestinal microbiome and human health was recognized, the etiology of Parkinson’s disease had long been linked to the gut through gastrointestinal symptoms such as constipation typically preceding motor and nonmotor disease manifestations and the detection of α-synuclein and Lewy bodies in the gut prior to their detection in the brain [41, 42]. We now know that changes to the gut microbiome occur prior to the manifestation of any overt Parkinson’s disease symptoms, suggesting that Parkinson’s disease etiology and disease subtype presentation may be intimately linked to the architecture of the gut microbiome by impacting the gut-brain-enteric microbiota axis [2, 12, 13].

In this study we chose to focus on the gut IgA-Biome as this microbial fraction are key regulators at the mucosal interface influencing the gut in disease and health compared with the larger number of undocumented microbiota remaining in the free lumen [17, 18]. In multiple-sclerosis, another form of neurodegeneration, IgA-coated bacteria were shown to traffic to the inflamed central nervous system and appeared to be systemic mediators in the disease that could serve as novel biomarkers [43]. In addition, evidence in both humans and animal models of Parkinson’s disease support the involvement of inflammation in disease onset and progression, further underscoring the need for IgA-Biome approaches designed to identify taxa with the potential of driving inflammation in the gut that can manifest systemically [44]. Targeting the malleable makeup of the gut microbiome presents an attractive target for both the prevention and treatment of Parkinson’s and related diseases.

Due to the heterogeneity of both the gut microbiome and Parkinson’s disease manifestations we hypothesized that gut microbiota signatures would differ between Parkinson’s disease patients presenting with AR or TD and that the host immune response and its interaction with the gut microbiota, i.e., the IgA-Biome could be further leveraged in the characterization of Parkinson’s disease phenotypes [3– 8].

Alpha diversity analyses identified significant differences between the AR and TD phenotypes in similar fashion as described by Vascellari et al. [30], that is, individuals presenting with the TD clinical subtype had significantly more OTUs and an increased Shannon diversity index than those presenting with the AR clinical phenotype. Additional alpha diversity analyses across the IgA-Biome revealed no differences in either OTUs or the Shannon diversity index among those with the AR clinical subtype. By contrast, similar comparisons identified significant OTU differences across the IgA-Biome of those presenting with the TD clinical subtype with higher OTUs observed in the IgA- fraction compared to the IgA+ fraction. That no differences were observed in between the IgA+ fraction of those with AR compared to those with TD is interesting considering that the number of IgA-coated bacteria was significantly higher in the AR group compared to the TD group.

Beta diversity analyses identified similar differences between the AR and TD clinical subtypes across the IgA-Biome. The significant unweighted UniFrac distances observed in presort samples were likely driven by the IgA– compartment since significance was observed in the IgA– but not the IgA+ compartment between those presenting with AR and TD.

The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio is critical to the maintenance of intestinal homeostasis and increases or decreases to the ratio of these phyla is regarded as dysbiosis depending on the disease, e.g., increased ratios are observed with obesity and autism and decreased ratios with inflammatory bowel disease [34, 45]. For this reason, we examined these ratios in the context of the AR and TD phenotypes. Across the IgA-Biome, this ratio was significantly higher in those with TD compared with those presenting with AR, suggesting that monitoring this ratio may be useful in measuring/predicting Parkinson’s disease progression.

The ultimate goal of microbiome research is establishing causality or contribution to disease pathogenesis; the identification of taxa that are responsible for disease etiology and/or disease presentation/severity. Although the present study is not longitudinal, the stability of the microbiome among Parkinson’s patients suggests that our findings may be extrapolated over time [46, 47]. Establishing temporal associations presents tremendous challenges, especially when conducting studies in humans regardless of whether the studies are longitudinal in nature. While the present study has such limitations, the results regarding the potential impact of species identified by LEfSe analyses of the IgA-Biome in the context of the AR and TD Parkinson’s disease clinical subtypes cannot be ignored. They are both intriguing an suggest further more definitive studies.

The IgA+ fraction of those presenting with the AR clinical subtype were defined by Bilophila wadsworthia, Flavonifractor plautii, and Prevotella disiens and the IgA– fraction by Dielema fastidiosa. The taxa targeted by SIgA in those presenting with the AR subtype are of interest largely due to their associations with proinflammatory states. B. wadsworthia is a pathobiont not typically identified in healthy individuals and has been correlated with chronic human disease, particularly those involving metabolic disorders in addition to associations with Parkinson’s disease [48, 49]. In mice, this organism has also been shown to synergize with a high fat diet promoting inflammation, intestinal barrier dysfunction, and bile acid dysmetabolism, and monocolonization with B. wadsworthia conferred cognitive impairment associated with increased numbers of INFγ-producing Th1 cells [49, 50]. In parallel, F. plautii decreased Th2 responses (indirectly promoting Th1 responses associated with a pro-inflammatory profile) [51]. P. disiens has been linked to elevated mucosal inflammatory responses driven by elevated Th17 cells and its presence at mucosal sites has been correlated with metabolic disorders and low-grade systemic inflammation [52]. The single LEfSe-identified species in the IgA– compartment (D. fastidiosa) does not have a pro-inflammatory profile but has been linked to progression of chronic kidney disease. Finally, Fusobacterium ulcerans and Bacteroides stercoris were identified in both the IgA+ and IgA– fractions. F. ulcerans and B. stercoris were identified in the gut microbiomes of COVID-19 patients presenting with gastrointestinal symptoms [53] and B. stercoris was also identified in the fecal microbiota transplant material derived from ulcerative colitis donors that elicited colitis in a dextran sulfate mouse model of disease [54]. The seemingly paradoxical observation that these two species are present in both compartments was addressed by Palm et al. when describing different physiologic impacts of bacteria of the same genus but of different strains [21]. That is, it is possible that different strains of F. ulcerans and B. stercoris are present in different IgA compartments or that these two taxa in particular may be more generally associated with Parkinson’s disease independent of host immunity.

The IgA+ fraction of those presenting with the TD clinical subtype were defined by Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and the IgA– fraction by Eubacterium rectale, Ruminococcus bicirculans, and Methanobrevibacter smithii. F. prausnitzii drives an anti-inflammatory environment by decreasing IL-12 and INFγ levels while concomitantly increasing IL-10 production [55]. Additional immunomodulatory effects of this species include maintaining the Th17/Treg balance by producing butyrate [56]. In the context of Parkinson’s disease, the TH17/Treg balance is critical since increased Th17 levels (and reduced Treg levels) positively correlated with α-synuclein levels and motor symptom severity [57]. In the IgA– fraction, E. rectale inhibits intestinal inflammation and reductions in E. rectale are linked to various human disease states [58, 59]. More specifically, E. rectale was positively associated with markers of reduced frailty and improved cognitive ability in addition to increasing production of short chain fatty acids [59]. R. bicirculans is an acetate and ethanol formate producer and M. smithii is a methane producer that reduces gut transit times and is present in higher numbers in irritable bowel syndrome patients [41, 60, 61].

The results of the LEfSe analyses generally point to a group of species (B. wadsworthia, F. plautii, P. disiens) in the IgA+ compartment of those with the more severe AR phenotype with a strong pro-inflammatory profile while the IgA-Biome of those in the TD group overall have an overall more anti-inflammatory species profile. The presence of the pro-inflammatory taxa in the IgA+ AR fraction may be indicative of the host attempting to eliminate these species or reduce/limit their contact with the gut epithelium. In the TD group, the fact that an anti-inflammatory species (F. prausnitzii) is targeted by SIgA and a second (E. rectale) is not underscores a limitation to IgA-Biome studies that are incapable of distinguishing SIgA coating effector function, i.e., immune exclusion vs. immune inclusion [14, 16]. Does E. rectale not require the SIgA coating for it to exert its physiological function in contrast to F. prausnitzii? One way to address this question would require characterizing the IgA-Biome of the mucosa (mucosa biopsies) and comparing it to the fecal IgA-Biome since bacteria associated with the mucosa likely differ from those free in the lumen and may be the ideal source for finding the important strains of the IgA-Biome [18]. In addition to the inflammatory profile identified in association with the AR IgA+ compartment the significant differences in the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio between the AR and TD groups was a significant finding and a potential marker of disease progression.

Data presented in this report highlight significant differences in the IgA-Biome of individuals classified as either AR or TD, not only strengthening the link between the gut microbiota and Parkinson’s disease but highlighting that differences across the Parkinson’s disease spectrum also correlate with distinct gut microbiota signatures. Better defined correlates of disease will require prospective longitudinal studies followed by the transfer of select taxa for assessment of disease-causing potential in animal models of disease accompanied by detailed characterization of host immune response profiles and metabolomic profiles [62]. The authors suggest that investigators involved in intestinal microbiome research focus on the IgA-Biome because it is more likely to correlate with disease states in which the microbiome is a contributing factor.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This word described in this report was funded by the MD Anderson Foundation, the Kelsey Research Foundation (HD and AA), the Joe and Jessie Crump Foundation Medical Research Fund, and the University of Texas School of Public Health (HD and Z-DJ). Additional funding support was provided by the Texas Medical Center, Digestive Disease Center (Public Health Service grand DK56338 (HD).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JPD-230066.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data supporting the findings described in this report are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical reasons.

REFERENCES

- [1]. Lei Q, Wu T, Wu J, Hu X, Guan Y, Wang Y, Yan J, Shi G (2021) Roles of alphasynuclein in gastrointestinal microbiome dysbiosisrelated Parkinson’s disease progression (Review). Mol Med Rep 24, 734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Mulak A, Bonaz B (2015) Brain-gut-microbiota axis in Parkinson’s disease. World J Gastroenterol 21, 10609–10620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Zetusky WJ, Jankovic J, Pirozzolo FJ (1985) The heterogeneity of Parkinson’s disease: Clinical and prognostic implications. Neurology 35, 522–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Poewe W, Gerstenbrand F (1986) Clinical subtypes of Parkinson disease. Wien Med Wochenschr 136, 384–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Schiess MC, Zheng H, Soukup VM, Bonnen JG, Nauta HJ (2000) Parkinson’s disease subtypes: Clinical classification and ventricular cerebrospinal fluid analysis. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 6, 69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Jankovic J, McDermott M, Carter J, Gauthier S, Goetz C, Golbe L, Huber S, Koller W, Olanow C, Shoulson I, et al. (1990) Variable expression of Parkinson’s disease: A base-line analysis of the DATATOP cohort. The Parkinson Study Group. Neurology 40, 1529–1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Stebbins GT, Goetz CG, Burn DJ, Jankovic J, Khoo TK, Tilley BC (2013) How to identify tremor dominant and postural instability/gait difficulty groups with the movement disorder society unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale: Comparison with the unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale. Mov Disord 28, 668–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Marras C, Lang A (2013) Parkinson’s disease subtypes: Lost in translation? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 84, 409–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9]. Aleksovski D, Miljkovic D, Bravi D, Antonini A (2018) Disease progression in Parkinson subtypes: The PPMI dataset. Neurol Sci 39, 1971–1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Burn DJ, Rowan EN, Minett T, Sanders J, Myint P, Richardson J, Thomas A, Newby J, Reid J, O’Brien JT, McKeith IG (2003) Extrapyramidal features in Parkinson’s disease with and without dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies: A cross-sectional comparative study. Mov Disord 18, 884–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11]. Rajput AH, Voll A, Rajput ML, Robinson CA, Rajput A (2009) Course in Parkinson disease subtypes: A 39-year clinicopathologic study. Neurology 73, 206–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12]. Rhee SH, Pothoulakis C, Mayer EA (2009) Principles and clinical implications of the brain-gut-enteric microbiota axis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 6, 306–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13]. Kim N, Yun M, Oh YJ, Choi HJ (2018) Mind-altering with the gut: Modulation of the gut-brain axis with probiotics. J Microbiol 56, 172–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Huus KE, Petersen C, Finlay BB (2021) Diversity and dynamism of IgA-microbiota interactions. Nat Rev Immunol 21, 514–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Macpherson AJ, Ganal-Vonarburg SC (2018) IgA-about the unexpected. J Exp Med 215, 1965–1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16]. Macpherson AJ, Yilmaz B, Limenitakis JP, Ganal-Vonarburg SC (2018) IgA function in relation to the intestinal microbiota. Annu Rev Immunol 36, 359–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17]. Weis AM, Round JL (2021) Microbiota-antibody interactions that regulate gut homeostasis. Cell Host Microbe 29, 334–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18]. DuPont HL, Jiang Z-D, Alexander AS, Dupont DW, Brown EL (2022) Intestinal IgA-coated bacteria in healthy- and altered-microbiomes (dysbiosis) and predictive value in successful fecal microbiota transplantation. Microorganisms 11, 93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19]. Sterlin D, Larsen M, Fadlallah J, Parizot C, Vignes M, Autaa G, Dorgham K, Juste C, Lepage P, Aboab J, Vicart S, Maillart E, Gout O, Lubetzki C, Deschamps R, Papeix C, Gorochov G (2021) Perturbed microbiota/immune homeostasis in multiple sclerosis. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 8, e997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Rojas OL, Probstel AK, Porfilio EA, Wang AA, Charabati M, Sun T, Lee DSW, Galicia G, Ramaglia V, Ward LA, Leung LYT, Najafi G, Khaleghi K, Garcillan B, Li A, Besla R, Naouar I, Cao EY, Chiaranunt P, Burrows K, Robinson HG, Allanach JR, Yam J, Luck H, Campbell DJ, Allman D, Brooks DG, Tomura M, Baumann R, Zamvil SS, Bar-Or A, Horwitz MS, Winer DA, Mortha A, Mackay F, Prat A, Osborne LC, Robbins C, Baranzini SE, Gommerman JL (2019) Recirculating intestinal IgA-producing cells regulate neuroinflammation via IL-10. Cell 177, 492–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21]. Palm NW, de Zoete MR, Cullen TW, Barry NA, Stefanowski J, Hao L, Degnan PH, Hu J, Peter I, Zhang W, Ruggiero E, Cho JH, Goodman AL, Flavell RA (2014) Immunoglobulin A coating identifies colitogenic bacteria in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell 158, 1000–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22]. Kau AL, Planer JD, Liu J, Rao S, Yatsunenko T, Trehan I, Manary MJ, Liu TC, Stappenbeck TS, Maleta KM, Ashorn P, Dewey KG, Houpt ER, Hsieh CS, Gordon JI (2015) Functional characterization of IgA-targeted bacterial taxa from undernourished Malawian children that produce diet-dependent enteropathy. Sci Transl Med 7, 276ra224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23]. Brown EL, Essigmann HT, Hoffman KL, Palm NW, Gunter SM, Sederstrom JM, Petrosino JF, Jun G, Aguilar D, Perkison WB, Hanis CL, DuPont HL (2020) Impact of diabetes on the gut and salivary IgA microbiomes. Infect Immun 88, e00301–e00320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24]. Human Microbiome Project C (2012) Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature 486, 207–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25]. Edgar RC (2010) Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26, 2460–2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26]. Edgar RC (2013) UPARSE: Highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat Methods 10, 996–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27]. Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, Gerken J, Schweer T, Yarza P, Peplies J, Glockner FO (2013) The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res 41, D590–D596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28]. Segata N, Izard J, Waldron L, Gevers D, Miropolsky L, Garrett WS, Huttenhower C (2011) Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol 12, R60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29]. Scheperjans F, Aho V, Pereira PA, Koskinen K, Paulin L, Pekkonen E, Haapaniemi E, Kaakkola S, Eerola-Rautio J, Pohja M, Kinnunen E, Murros K, Auvinen P (2015) Gut microbiota are related to Parkinson’s disease and clinical phenotype. Mov Disord 30, 350–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30]. Vascellari S, Melis M, Palmas V, Pisanu S, Serra A, Perra D, Santoru ML, Oppo V, Cusano R, Uva P, Atzori L, Morelli M, Cossu G, Manzin A (2021) Clinical phenotypes of Parkinson’s disease associate with distinct gut microbiota and metabolome enterotypes. Biomolecules 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31]. Lozupone C, Lladser ME, Knights D, Stombaugh J, Knight R (2011) UniFrac: An effective distance metric for microbial community comparison. ISME J 5, 169–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32]. Ley RE, Backhed F, Turnbaugh P, Lozupone CA, Knight RD, Gordon JI (2005) Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102, 11070–11075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33]. Turnbaugh PJ, Hamady M, Yatsunenko T, Cantarel BL, Duncan A, Ley RE, Sogin ML, Jones WJ, Roe BA, Affourtit JP, Egholm M, Henrissat B, Heath AC, Knight R, Gordon JI (2009) A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature 457, 480–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34]. Strati F, Cavalieri D, Albanese D, De Felice C, Donati C, Hayek J, Jousson O, Leoncini S, Renzi D, Calabro A, De Filippo C (2017) New evidences on the altered gut microbiota in autism spectrum disorders. Microbiome 5, 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35]. Romano S, Savva GM, Bedarf JR, Charles IG, Hildebrand F, Narbad A (2021) Meta-analysis of the Parkinson’s disease gut microbiome suggests alterations linked to intestinal inflammation. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 7, 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36]. Madan A, Thompson D, Fowler JC, Ajami NJ, Salas R, Frueh BC, Bradshaw MR, Weinstein BL, Oldham JM, Petrosino JF (2020) The gut microbiota is associated with psychiatric symptom severity and treatment outcome among individuals with serious mental illness. J Affect Disord 264, 98–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37]. Essigmann HT, Hoffman KL, Petrosino JF, Jun G, Aguilar D, Hanis CL, DuPont HL, Brown EL (2021) The impact of the Th17:Treg axis on the IgA-Biome across the glycemic spectrum. PLoS One 16, e0258812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38]. Nowak JM, Kopczynski M, Friedman A, Koziorowski D, Figura M (2022) Microbiota dysbiosis in Parkinson disease-in search of a biomarker. Biomedicines 10, 2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39]. Li Z, Liang H, Hu Y, Lu L, Zheng C, Fan Y, Wu B, Zou T, Luo X, Zhang X, Zeng Y, Liu Z, Zhou Z, Yue Z, Ren Y, Li Z, Su Q, Xu P (2023) Gut bacterial profiles in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review. CNS Neurosci Ther 29, 140–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40]. Ueki A, Goto K, Ohtaki Y, Kaku N, Ueki K (2017) Description of Anaerotignum aminivorans gen. nov., sp. nov., a strictly anaerobic, amino-acid-decomposing bacterium isolated from a methanogenic reactor, and reclassification of Clostridium propionicum, Clostridium neopropionicum and Clostridium lactatifermentans as species of the genus Anaerotignum. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 67, 4146–4153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41]. Danau A, Dumitrescu L, Lefter A, Tulba D, Popescu BO (2021) Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth as potential therapeutic target in Parkinson’s disease. Int J Mol Sci 22, 11663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42]. Hill-Burns EM, Debelius JW, Morton JT, Wissemann WT, Lewis MR, Wallen ZD, Peddada SD, Factor SA, Molho E, Zabetian CP, Knight R, Payami H (2017) Parkinson’s disease and Parkinson’s disease medications have distinct signatures of the gut microbiome. Mov Disord 32, 739–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43]. Probstel AK, Zhou X, Baumann R, Wischnewski S, Kutza M, Rojas OL, Sellrie K, Bischof A, Kim K, Ramesh A, Dandekar R, Greenfield AL, Schubert RD, Bisanz JE, Vistnes S, Khaleghi K, Landefeld J, Kirkish G, Liesche-Starnecker F, Ramaglia V, Singh S, Tran EB, Barba P, Zorn K, Oechtering J, Forsberg K, Shiow LR, Henry RG, Graves J, Cree BAC, Hauser SL, Kuhle J, Gelfand JM, Andersen PM, Schlegel J, Turnbaugh PJ, Seeberger PH, Gommerman JL, Wilson MR, Schirmer L, Baranzini SE (2020) Gut microbiota-specific IgA(+) B cells traffic to the CNS in active multiple sclerosis. Sci Immunol 5, eabc7191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44]. Pajares M, I Rojo A, Manda G, Boscá L, Cuadrado A (2020) Inflammation in Parkinson’s disease: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Cells 9, 1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45]. Stojanov S, Berlec A, Strukelj B (2020) The influence of probiotics on the firmicutes/bacteroidetes ratio in the treatment of obesity and inflammatory bowel disease. Microorganisms 8, 1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46]. Lubomski M, Xu X, Holmes AJ, Muller S, Yang JYH, Davis RL, Sue CM (2022) The gut microbiome in Parkinson’s disease: A longitudinal study of the impacts on disease progression and the use of device-assisted therapies. Front Aging Neurosci 14, 875261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47]. Aho VTE, Pereira PAB, Voutilainen S, Paulin L, Pekkonen E, Auvinen P, Scheperjans F (2019) Gut microbiota in Parkinson’s disease: Temporal stability and relations to disease progression. EBioMedicine 44, 691–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48]. Feng Z, Long W, Hao B, Ding D, Ma X, Zhao L, Pang X (2017) A human stool-derived strain caused systemic inflammation in specific-pathogen-free mice. Gut Pathog 9, 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49]. Natividad JM, Lamas B, Pham HP, Michel ML, Rainteau D, Bridonneau C, da Costa G, van Hylckama Vlieg J, Sovran B, Chamignon C, Planchais J, Richard ML, Langella P, Veiga P, Sokol H (2018) Bilophila wadsworthia aggravates high fat diet induced metabolic dysfunctions in mice. Nat Commun 9, 2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50]. Olson CA, Iniguez AJ, Yang GE, Fang P, Pronovost GN, Jameson KG, Rendon TK, Paramo J, Barlow JT, Ismagilov RF, Hsiao EY (2021) Alterations in the gut microbiota contribute to cognitive impairment induced by the ketogenic diet and hypoxia. Cell Host Microbe 29, 1378–1392 e1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51]. Ogita T, Yamamoto Y, Mikami A, Shigemori S, Sato T, Shimosato T (2020) Oral administration of strongly suppresses Th2 immune responses in mice. Front Immunol 11, 379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52]. Larsen JM (2017) The immune response to bacteria in chronic inflammatory disease. Immunology 151, 363–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53]. Li S, Yang S, Zhou Y, Disoma C, Dong Z, Du A, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Huang W, Chen J, Song D, Chen Z, Liu P, Li S, Zheng R, Liu S, Razzaq A, Chen X, Tao S, Yu C, Feng T, Liao W, Peng Y, Jiang T, Huang J, Wu W, Hu L, Wang L, Li S, Xia Z (2021) Microbiome profiling using shotgun metagenomic sequencing identified unique microorganisms in COVID-19 patients with altered gut microbiota. Front Microbiol 12, 712081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54]. Yang Y, Zheng X, Wang Y, Tan X, Zou H, Feng S, Zhang H, Zhang Z, He J, Cui B, Zhang X, Wu Z, Dong M, Cheng W, Tao S, Wei H (2022) Human fecal microbiota transplantation reduces the susceptibility to dextran sulfate sodium-induced germ-free mouse colitis. Front Immunol 13, 836542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55]. Sokol H, Pigneur B, Watterlot L, Lakhdari O, Bermudez-Humaran LG, Gratadoux JJ, Blugeon S, Bridonneau C, Furet JP, Corthier G, Grangette C, Vasquez N, Pochart P, Trugnan G, Thomas G, Blottiere HM, Dore J, Marteau P, Seksik P, Langella P (2008) Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 16731–16736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56]. Zhou L, Zhang M, Wang Y, Dorfman RG, Liu H, Yu T, Chen X, Tang D, Xu L, Yin Y, Pan Y, Zhou Q, Zhou Y, Yu C (2018) Faecalibacterium prausnitzii produces butyrate to maintain Th17/Treg balance and to ameliorate colorectal colitis by inhibiting histone deacetylase 1. Inflamm Bowel Dis 24, 1926–1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57]. Li J, Zhao J, Chen L, Gao H, Zhang J, Wang D, Zou Y, Qin Q, Qu Y, Li J, Xiong Y, Min Z, Yan M, Mao Z, Xue Z (2022) alpha-Synuclein induces Th17 differentiation and impairs the function and stability of Tregs by promoting RORC transcription in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Behav Immun 108, 32–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58]. Lu H, Xu X, Fu D, Gu Y, Fan R, Yi H, He X, Wang C, Ouyang B, Zhao P, Wang L, Xu P, Cheng S, Wang Z, Zou D, Han L, Zhao W (2022) Butyrate-producing suppresses lymphomagenesis by alleviating the TNF-induced TLR4/MyD88/NF-kappaB axis. Cell Host Microbe 30, 1139–1150 1137e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59]. Mukherjee A, Lordan C, Ross RP, Cotter PD (2020) Gut microbes from the phylogenetically diverse genus and their various contributions to gut health. Gut Microbes 12, 1802866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60]. Park W (2018) Gut microbiomes and their metabolites shape human and animal health. J Microbiol 56, 151–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61]. Ghoshal U, Shukla R, Srivastava D, Ghoshal UC (2016) Irritable bowel syndrome, particularly the constipation-predominant form, involves an increase in, which is associated with higher methane production. Gut Liver 10, 932–938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62]. Fischbach MA (2018) Microbiome: Focus on causation and mechanism. Cell 174, 785–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings described in this report are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical reasons.