Key Points

Question

What are the rates of second tumor, metastasis, and death from cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) in patients with and without transplant-associated immunosuppression?

Findings

In this cohort study of 46 784 non–organ transplant recipients (non-OTRs) with cSCC and 1208 organ transplant recipients (OTRs) with cSCC with registry data spanning more than 5 decades, OTRs with cSCC had significantly elevated rates of second tumor, metastasis, and death from cSCC. In both groups, most deaths were from causes other than cSCC and cSCC metastasis.

Meaning

As metastasis and death from cSCC are relatively rare events, this study’s findings suggest that better methods may be needed to identify patients with high risk and those with close to no risk of metastasis and death.

This cohort study assesses the rate of second tumor, metastasis, and death from cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) in patients with and without organ transplant–associated immunosuppression.

Abstract

Importance

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) may occur with multiple primary tumors, metastasize, and cause death both in immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients.

Objective

To study the rates of second cSCC, metastasis, and death from cSCC in patients with and without organ transplant–associated immunosuppressive treatment.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This population-based, nationwide cohort study used Cancer Registry of Norway data from 47 992 individuals diagnosed with cSCC at 18 years or older between January 1, 1968, and December 31, 2020. Data were analyzed between November 24, 2021, and November 15, 2022.

Exposures

Receipt of a solid organ transplant at Oslo University Hospital between 1968 and 2012 followed by long-term immunosuppressive treatment.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Absolute rates of second cSCC, metastasis, and death from cSCC were calculated per 1000 person-years with 95% CIs. Hazard ratios (HRs) estimated using Cox proportional hazard regression were adjusted for age, sex, and year of first cSCC diagnosis.

Results

The study cohort comprised 1208 organ transplant recipients (OTRs) (median age, 66 years [range, 27-89 years]; 882 men [73.0%] and 326 women [27.0%]) and 46 784 non-OTRs (median age, 79 years [range, 18-106 years]; 25 406 men [54.3%] and 21 378 women [45.7%]). The rate of a second cSCC per 1000 person-years was 30.9 (95% CI, 30.2-31.6) in non-OTRs and 250.6 (95% CI, 232.2-270.1) in OTRs, with OTRs having a 4.3-fold increased rate in the adjusted analysis. The metastasis rate per 1000 person-years was 2.8 (95% CI, 2.6-3.0) in non-OTRs and 4.8 (95% CI, 3.4-6.7) in OTRs, with OTRs having a 1.5-fold increased rate in the adjusted analysis. A total of 30 451 deaths were observed, of which 29 895 (98.2%) were from causes other than cSCC. Death from cSCC was observed in 516 non-OTRs (1.1%) and 40 OTRs (3.3%). The rate of death from cSCC per 1000 person-years was 1.7 (95% CI, 1.5-1.8) in non-OTRs and 5.4 (95% CI, 3.9-7.4) in OTRs, with OTRs having a 5.5-fold increased rate in the adjusted analysis.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cohort study, OTRs with cSCC had significantly higher rates of second cSCC, metastasis, and death from cSCC than non-OTRs with cSCC, although most patients with cSCC in both groups died from causes other than cSCC. These findings are relevant for the planning of follow-up of patients with cSCC and for skin cancer services.

Introduction

Patients with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC), globally the second-most common form of skin cancer, frequently develop multiple primary tumors either simultaneously or during follow-up.1 The reported risk of metastasis from cSCC varies, particularly between hospital-based2,3,4,5,6 and population-based studies.7,8,9 Organ transplant recipients (OTRs) have a very high risk of developing cSCC10,11,12,13 and seem to have a greater risk of metastasis from cSCC than immunocompetent patients.14 Studies on the risk of disease-specific death from cSCC, however, are limited both in immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients.15,16 To increase knowledge on the epidemiology and clinical course of cSCC, we studied the occurrence of a second cSCC, metastasis, and death from cSCC in non-OTRs and OTRs, using population-based data from national registries that span more than 5 decades.

Methods

In Norway, medical doctors and pathology laboratories are required by law to report all cases of cancer (except basal cell carcinoma) and cancer metastasis to the national Cancer Registry of Norway.17 In this cohort study, we included all patients diagnosed with at least 1 histologically verified cSCC between January 1, 1968, and December 31, 2020, except those younger than 18 years at the time of cSCC diagnosis. The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Ethics in Medical and Health-related Research in South-East Norway (#2012/1154), the data protection officer at Oslo University Hospital, and the data delivery unit at the Cancer Registry of Norway and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Individual informed consent was not found to be required by the ethics committee. This report followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.18

In situ tumors (ie, cSCC in situ) were not included. Primary anatomic location of the tumor was categorized as ear, head and face (including the eyelid), neck and trunk, perineum and perianal, upper limbs, lower limbs, multiple localizations (based on clinical notification of >1 tumor within the diagnostic period of 4 months), and unspecified location.

The Cancer Registry of Norway also provides information on second cSCC and metastasis from cSCC. All histologically verified second tumors and metastases are reported to the registry by pathology laboratories. In addition, clinicians may report second tumors and metastases based on clinical and radiologic examination, but such reports have been shown to constitute only a small proportion of the total numbers of reported second tumors and metastases.17,19 Information on vital status (ie, alive, emigrated, died) and dates of emigration and death were obtained by linkage to the National Population Register using the unique personal identification number assigned to all Norwegian citizens. Similarly, information on cause of death, set by clinicians, was obtained by linkage to the Norwegian Cause of Death Registry.

All solid organ transplants in Norway are performed at Oslo University Hospital. In the period from January 1, 1968, to December 31, 2012, 8278 patients received a kidney (from 1968), heart (from 1983), lung (from 1986), or liver (from 1984) transplant, of whom more than 75% had received kidney transplants.10 Organ transplant recipients with at least 1 cSCC tumor were identified by linkage to organ-specific national registries on organ transplant.10 Time of transplant was obtained, and 19 patients with cSCC before first organ transplant were excluded. Data on OTRs receiving their first organ transplant between 2013 and 2020 were not available.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes were a second cSCC, metastasis, and death from cSCC. A second cSCC was defined either based on the clinical notification of more than 1 tumor registered with multiple locations at the time of first cSCC (including up to 4 months thereafter) or registration of a second cSCC during follow-up. Metastasis, defined as regional lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis, was registered either at the time of diagnosis of first cSCC (including up to 4 months thereafter) or during follow-up. Death from cSCC includes deaths with cSCC as the underlying cause.

Statistical Analysis

Patients were followed from the date of first cSCC diagnosis to the date of the primary outcome (ie, second cSCC, metastasis, death from cSCC) and censored at emigration, death, or end of study (ie, December 31, 2020), whichever occurred first. Due to restrictions in the General Data Protection Regulations, only month of diagnosis was reported by the cancer registry. Thus, the day of event was set to the 15th of each month. If the month of second cSCC, metastasis, or death was identical to the month of first cSCC diagnosis, then time of second cSCC, metastasis, or death was set to that date plus 1 day in order to fit the statistical model.

Absolute rates of second cSCC, metastasis, and death from cSCC are presented per 1000 person-years, with 95% CIs calculated using the exact Poisson method. Cause-specific hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CIs were estimated using Cox proportional hazards regression, with time since diagnosis of first cSCC as the time scale and taking competing risk of death into account. We adjusted for age, sex, and year of first cSCC diagnosis in the multivariable models. Data on race and ethnicity were not available. The probabilities of developing a second cSCC, metastasis, or death from cSCC were summarized separately based on age-adjusted cumulative incidence functions during the 30 years after the first cSCC diagnosis, taking into account competing risk of events, including all-cause mortality. In addition, we performed secondary analyses restricted to patients diagnosed with cSCC between 1968 and 2012. In OTRs with cSCC, we also analyzed possible associations between time of transplant (ie, 1968-1982, 1983-1992, 1993-2002, 2003-2012) and rates of second posttransplant cSCC, metastasis, and death from cSCC. Statistical analyses were conducted from November 24, 2021, to November 15, 2022, using Stata, version 17 software (StataCorp LLC).

Results

Of approximately 5.4 million inhabitants in Norway (as of 2020),20 47 992 persons aged 18 years or older were diagnosed with cSCC during the study period (1968-2020). Of these patients, 1208 received an organ transplant before the end of 2012 (Table 1). The majority of non-OTRs and OTRs were men (25 406 [54.3%] and 882 [73.0%], respectively, vs 21 378 [45.7%] and 326 [27.0%] women, respectively). Non-OTRs were generally older at the time of first cSCC diagnosis than OTRs (median [range], 79 [18-106] and 66 [27-89] years, respectively). Emigration was registered in 70 patients (0.2%), all non-OTRs. In OTRs, median time from organ transplant to first cSCC was 10.3 years (range, 0.1-45.5 years). Head and face were the most common tumor sites in both groups (22 329 [47.7%] and 367 [30.4%]), while multiple localizations were more frequent in OTRs (476 [39.4%]) than in non-OTRs (5728 [12.2%]) (Table 1).

Table 1. Clinical Characteristics of Organ Transplant Recipients (OTRs) and Non-OTRs With Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma (cSCC).

| Characteristic | Non-OTRs (n = 46 784) | OTRs (n = 1208) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, No. (%) | ||

| Men | 25 406 (54.3) | 882 (73.0) |

| Women | 21 387 (45.7) | 326 (27.0) |

| Age at first cSCC diagnosis, y, median (range) | 79 (18-106) | 66 (27-89) |

| Year of first cSCC diagnosis, No. (%) | ||

| 1968-1990 | 8249 (17.6) | 46 (3.8) |

| 1991-2000 | 7904 (16.9) | 268 (22.2) |

| 2001-2010 | 11 555 (24.7) | 383 (31.7) |

| 2011-2020 | 19 076 (40.8) | 511 (42.3) |

| Site of tumor, No. (%) | ||

| Ear | 4838 (10.3) | 79 (6.5) |

| Head and face | 22 329 (47.7) | 367 (30.4) |

| Neck and trunk | 6454 (13.8) | 138 (11.4) |

| Perineum and perianal | 359 (0.8) | 8 (0.7) |

| Upper limbs | 3832 (8.2) | 90 (7.5) |

| Lower limbs | 2574 (5.5) | 38 (3.2) |

| Multiple localizations | 5728 (12.2) | 476 (39.4) |

| Unspecified | 670 (1.4) | 12 (1.0) |

| Age at transplant, y, median (range) | NA | 54.4 (9.1-82.6) |

| Period of transplant, No. (%) | ||

| 1968-1982 | NA | 142 (11.8) |

| 1983-1992 | NA | 386 (32.0) |

| 1993-2002 | NA | 371 (30.7) |

| 2003-2012 | NA | 309 (25.6) |

| Time from first transplant to first cSCC, y, median (range) | NA | 10.3 (0.1-45.5) |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

A second cSCC was registered in 8561 patients (17.8%) (ie, 7876 non-OTRs [16.8%] and 685 OTRs [56.7%]) (Table 2). The rates of a second cSCC per 1000 person-years were 30.9 (95% CI, 30.2-31.6) and 250.6 (95% CI, 232.2-270.1), respectively. In the adjusted analysis, OTRs had a significant 4.3-fold increased rate of a second cSCC compared with non-OTRs.

Table 2. Rates and Hazard Ratios (HRs) of Second Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma (cSCC), Metastasis, and Death From cSCC in Organ Transplant Recipients (OTRs) vs Non-OTRs With cSCC.

| No. (%) of patients | Follow-up, person-years | Rate per 1000 person-years (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age-adjusted | Multivariable-adjusteda | ||||

| Second cSCC | |||||

| Non-OTRs | 7876 (16.8) | 254 678 | 30.9 (30.2-31.6) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| OTRs | 685 (56.7) | 2733 | 250.6 (232.2-270.1) | 4.7 (4.3-5.1) | 4.3 (3.9-4.6) |

| Metastasis | |||||

| Non-OTRs | 845 (1.8) | 305 161 | 2.8 (2.6-3.0) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| OTRs | 35 (3.0) | 7275 | 4.8 (3.4-6.7) | 1.4 (1.0-2.0) | 1.5 (1.0-2.1) |

| Death from cSCC | |||||

| Non-OTRs | 516 (1.1) | 307 982 | 1.7 (1.5-1.8) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| OTRs | 40 (3.3) | 7351 | 5.4 (3.9-7.4) | 6.6 (4.7-9.3) | 5.5 (3.9-7.8) |

Adjusted for age at diagnosis, sex, and year of first cSCC diagnosis.

Metastases were registered in 880 patients (1.8%) (845 non-OTRs [1.8%] and 35 OTRs [3.0%]) (Table 2). The metastasis rates per 1000 person-years were 2.8 (95% CI, 2.6-3.0) and 4.8 (95% CI, 3.4-6.7), respectively. In the adjusted analysis, OTRs had a significant 1.5-fold increased rate of metastasis compared with non-OTRs.

A total of 30 451 deaths from cSCC were observed, of which 29 895 (98.2%) were from causes other than cSCC. Death from cSCC was observed in 516 non-OTRs (1.1%) and 40 OTRs (3.3%) (Table 2). The cSCC mortality rates per 1000 person-years were 1.7 (95% CI, 1.5-1.8) and 5.4 (95% CI, 3.9-7.4), respectively, with OTRs having a significant 5.5-fold increased rate of death from cSCC compared with non-OTRs in the adjusted analysis. Among the 556 patients who died from cSCC, 289 (52.0%) were registered as having no metastasis from cSCC, while metastasis status was unknown in 124 (22.3%).

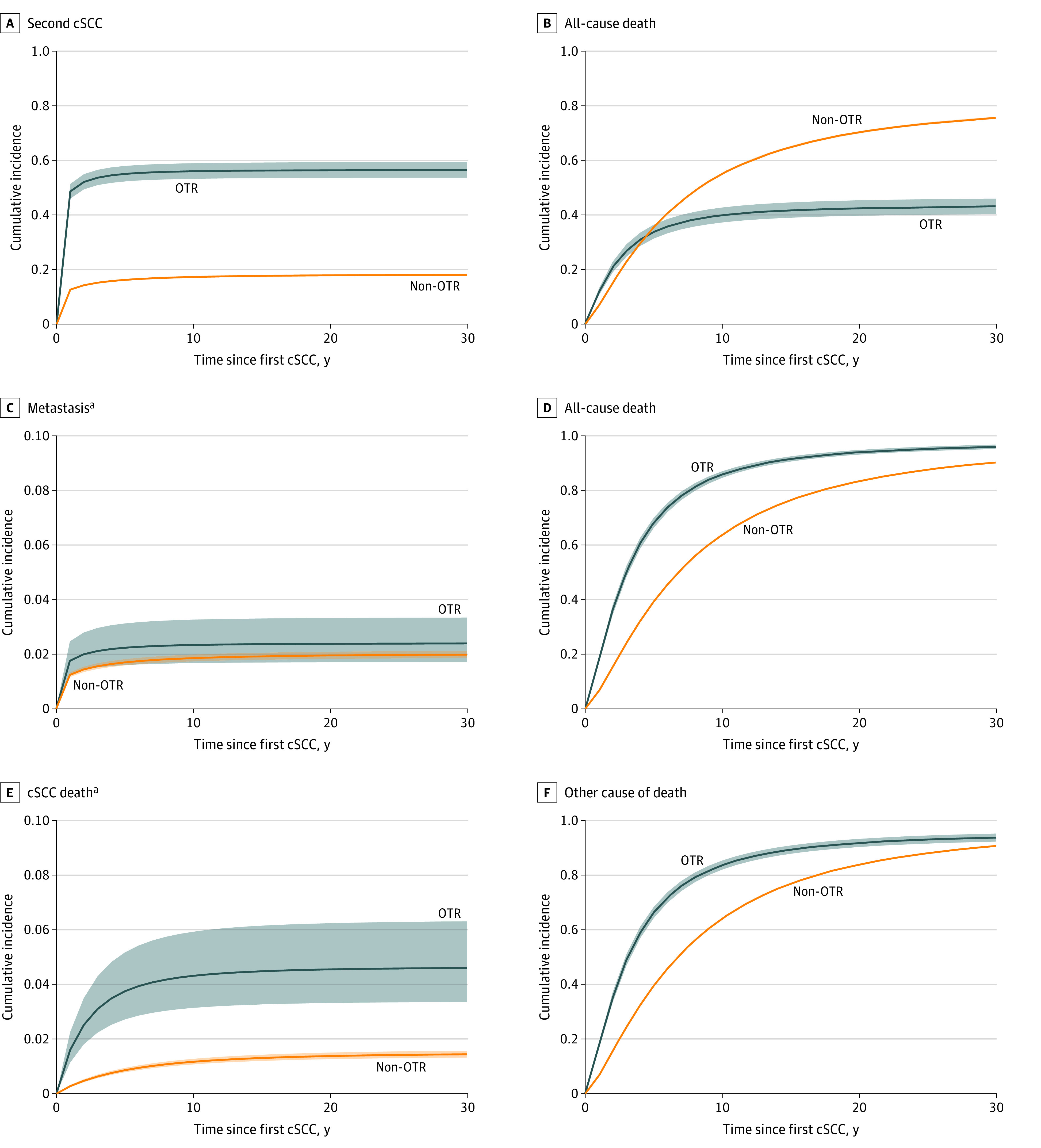

The 5-year cumulative incidence of a second cSCC, metastasis, and death from cSCC were 16.2 (95% CI, 15.9-16.6), 1.7 (95% CI, 1.6-1.8), and 0.9 (95% CI, 0.8-0.9), respectively, among non-OTRs and 55.0 (95% CI, 52.3-57.9), 2.2 (95% CI, 1.6-3.1), and 3.7 (95% CI, 2.7-5.2), respectively, among OTRs (Table 3). Thereafter, the cumulative incidence stabilized. The Figure illustrates the competing events, including all-cause mortality (Figure, A-D), and that death from causes other than cSCC was more prominent than death from cSCC (Figure, E and F).

Table 3. Age-Adjusted Cumulative Incidence of Second Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma (cSCC), Metastasis, and Death From cSCC in Organ Transplant Recipients (OTRs) and Non-OTRs With cSCC.

| No. of years after diagnosis of first cSCC | Cumulative incidence (95% CI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second cSCC | Metastasis | Death from cSCC | |||||

| Non-OTRs | OTRs | Non-OTRs | OTRs | Non-OTRs | OTRs | ||

| 5 | 16.2 (15.9-16.6) | 55.0 (52.3-57.9) | 1.7 (1.6-1.8) | 2.2 (1.6-3.1) | 0.9 (0.8-0.9) | 3.7 (2.7-5.2) | |

| 10 | 17.3 (17.0-17.7) | 56.0 (53.2-58.9) | 1.9 (1.7-2.0) | 2.3 (1.7-3.3) | 1.2 (1.1-1.3) | 4.3 (3.1-5.9) | |

| 20 | 17.9 (17.5-18.3) | 56.4 (53.6-59.3) | 2.0 (1.8-2.1) | 2.4 (1.7-3.3) | 1.4 (1.3-1.5) | 4.5 (3.3-6.2) | |

Figure. Cumulative Incidence of Second Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma (cSCC), Metastasis, and Death From cSCC and Competing Risks of Death.

Cumulative incidence with 95% confidence band during 30 years after first cSCC in organ transplant recipients (OTRs) and non-OTRs. The 95% CIs for non-OTRs are so narrow that they seem invisible due to the high number of patients.

aThe scale of the y-axis is restricted to a maximum of 0.10 due to the low number of events.

Analyses restricted to patients diagnosed with cSCC in the period of 1968-2012 showed similar results for the rates of second tumor, metastasis, and death from cSCC, except for rates being slightly lower and the cumulative incidence of a second cSCC marginally higher for OTRs (eTable in Supplement 1). Patients who received their first organ transplant in 2003-2012 had a lower risk of a second cSCC than those who received their first transplant in 1983-1992 (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.54-0.89). Those who received the first organ transplant in 1993-2002 had a numerically lower risk, but with no statistically significant difference (HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.73-1.07) (Table 4) (Table 4). No significant differences between periods of transplant were found regarding rates of metastasis and death from cSCC.

Table 4. Hazard Ratio (HRs) of Second Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma (cSCC), Metastasis, and Death From cSCC in 1208 Organ Transplant Recipients With cSCC According to Period of First Organ Transplant.

| Period of first organ transplant | HR (95% CI)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Second cSCC | Metastasis | Death from cSCC | |

| 1968-1982 | 1.10 (0.87-1.39) | 1.30 (0.51-3.32) | 0.57 (0.16-2.00) |

| 1983-1992 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 1993-2002 | 0.88 (0.73-1.07) | 0.73 (0.31-1.72) | 0.88 (0.40-1.93) |

| 2003-2012 | 0.69 (0.54-0.89) | 0.41 (0.13-1.26) | 0.89 (0.32-2.46) |

Adjusted for age at diagnosis, sex, and year of first cSCC diagnosis.

Discussion

In this population-based, nationwide cohort study using registry data spanning more than 5 decades, a second cSCC, metastasis, and death from cSCC occurred more often in OTRs with cSCC than in non-OTRs with cSCC. Death from cSCC was a relatively rare event, particularly in non-OTRs, and most deaths during the study period were from causes other than cSCC. This finding reflects the older median age at the time of first cSCC diagnosis, particularly in non-OTRs, and demonstrates the role of competing risks of death, as shown by the cumulative incidence for second tumor, metastasis, and death from cSCC stabilizing after 5 years due to all-cause mortality. The competing risk of death is an important consideration in any epidemiologic and clinical study among older adults.21 The majority of the patients who died from cSCC were registered as having no metastasis, suggesting that most patients who died from cSCC may have died from a locally infiltrating tumor and its complications and not from metastasis. This explanation is in line with prospective clinical cohort studies from Germany in which local infiltration of the tumor or local metastasis, and not distant metastases, was the most common cause of death among patients who died from cSCC.15,16

The overall rate of metastasis from cSCC in our study (1.83%) indicates that previous higher estimates, ranging from 3.1% to 5.15%,2,3,4,5,6 may be explained by selection bias in patient cohorts from hospitals in which patients with larger and more advanced tumors are being treated. Our metastasis rate is more in line with more recent population-based studies, all with shorter follow-up time than our study.7,8,9 In a small UK study from the Isle of Wight, metastasis occurred in 1.2% of patients with cSCC.7 In a study from Norway in patients diagnosed with cSCC between 2000 and 2004, 1.5% were diagnosed with metastasis within 5 years.8 In a large population-based study in the UK, cumulative incidence of metastasis in patients with cSCC up to 36 months was 1.1% in women and 2.4% in men.9

The significantly higher rate of cSCC metastasis in OTRs than in non-OTRs supports the findings of some, but not all, similar studies.14 Despite the heterogeneity of such studies, a systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that OTRs are at increased risk of metastasis from cSCC compared with immunocompetent populations.14 This difference may be explained by compromised immunologic tumor surveillance from and tumor-enhancing effects of the immunosuppressive drugs used by OTRs.22

We found a high rate of second cSCC, particularly in OTRs; in fact, more than one-half of all OTRs with cSCC were diagnosed with a second cSCC, which is in line with other studies.13,23,24,25 This finding emphasizes the great disease burden associated with cSCC—particularly in OTRs, many of whom will develop a very high number of cSCCs—and the substantial health care costs related to diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. The true overall incidence of cSCC is often underestimated, partly because most cancer registry reports are based on 1 cSCC tumor per patient only.26

Rizvi et al10 reported on a declining incidence of posttransplant cSCC in patients undergoing an organ transplant after 1993 compared with those undergoing a transplant between 1983 and 1992. We found a similar decline in the incidence of a second posttransplant cSCC. Period of transplant may be regarded as a proxy for different immunosuppressive regimens, ie, regimens without cyclosporin (1968-1982), with high-dose cyclosporin (1983-1992), and with lower-dose cyclosporin or with less carcinogenic drugs (1993-2002 and 2003-2012).10 Thus, the decline in the incidence of first and second cSCC after organ transplant may be explained by the use of less aggressive, less carcinogenic, and more individualized immunosuppressive treatment over time. The rates of metastasis and death from cSCC in OTRs with cSCC did not change significantly, but the numbers of events were relatively small and the CIs wide. We were not able to include type of organ transplant in our analyses, but in a recent study from a large US transplant center, type of organ transplant was not associated with the risk of an additional skin cancer, despite the fact that patients with a transplanted heart, lung, or kidney were more likely to develop at least 1 skin cancer than those with a liver transplant.27

Our results have implications for the clinical follow-up of patients with cSCC. With the high volume of patients with cSCC, skin cancer services should be organized so that patients receive individualized and optimal care without an unmanageably high number of consultations and referrals. The high incidence of multiple and additional cSCC tumors in OTRs underscores the need for systematic dermatologic screening and surveillance of OTRs,28 which can be accomplished by using the validated Skin and UV Neoplasia Transplant Risk Assessment Calculator.29,30

With new therapeutic options for advanced cSCC31 and increasing incidence rates of cSCC,1,32,33 we need tools to better identify patients with a particularly high risk of metastasis and death from cSCC as well as those with close to no risk. Unfortunately, present staging systems for cSCC have low positive predictive values for regional and distant metastasis.8,33 Clinicians must use their clinical judgment and best practice guidelines available when deciding on what to do and what to tell the patient. In addition to tumor thickness, immunosuppression, and other known risk factors, each patient’s individual circumstances and preferences should be taken into account.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has a number of strengths. It is population based and, therefore, includes all patients with cSCC regardless of whether they had been treated in or outside a hospital setting. The data were retrieved from national registries on cancer and death, providing reliable data from nonselected patients spanning more than 5 decades. The completeness and quality of the Cancer Registry of Norway have been shown to be high,17 although registration of a second cSCC and metastasis from cSCC may be incomplete, as second tumors and metastases that are not histologically verified need to be reported by a clinician. We believe, however, that a possible incomplete reporting of second tumors and metastases would affect non-OTRs and OTRs similarly and, therefore, would not influence the comparative analyses in a significant way.

Our study also has some limitations. Some surveillance bias cannot be excluded, as many OTRs are followed up at academic hospitals. The validity of cancer-specific deaths in the Norwegian Cause of Death Registry has been found to be satisfactory for several forms of cancer, although some misclassification may occur.34 We did not have access to the identities of OTRs receiving their first transplant between 2013 and 2020. However, taking into account the median time from first transplant to first cSCC being more than 10 years and the declining incidence of posttransplant cSCC in Norway in recent decades,10 we estimated that less than 0.3% of the patients with cSCC were incorrectly categorized as non-OTRs. In addition, our secondary analyses restricted to patients diagnosed with cSCC between 1968 and 2012 had similar results as the primary analyses. We did not have information on the immunocompetence of the non-OTRs, and this group therefore includes some patients with immunosuppression due to disease or due to immunosuppressive treatment for other indications than organ transplant. A correct categorization according to immunosuppression would probably have resulted in even greater differences in the rates of a second cSCC, metastasis, and death from cSCC. Our data set also did not include type of organ transplant and immunosuppressive therapy regimen in individual patients. We were not able to include subsequent cSCC accrual after a second cSCC and lacked cSCC staging data. We cannot exclude that some second cSCCs localized in the same anatomic region as the first cSCC were, in fact, recurrences. In patients with a second cSCC and metastases, we did not have information on which cSCC the metastases may have originated from. Although data on race and ethnicity were not included, the majority (>95%) of the patients were assumed to have a White skin type. Therefore, it is unclear whether the findings can be generalized to other racial and ethnic populations.

Conclusions

The findings of this population-based cohort study add information on the epidemiology and clinical course of cSCC in immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients. Organ transplant recipients with cSCC in Norway had significantly higher rates of a second cSCC, metastasis, and death from cSCC than non-OTRs with cSCC, although most patients in both groups died from causes other than cSCC and cSCC metastasis. These findings have implications for the clinical follow-up of individual patients and for skin cancer care policies.

eTable. Secondary Analyses Restricted to Organ Transplant Recipients (OTRs) and Non-OTR Patients Diagnosed With Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma (cSCC) in the Period 1968-2012

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Green AC, Olsen CM. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: an epidemiological review. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(2):373-381. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brantsch KD, Meisner C, Schönfisch B, et al. Analysis of risk factors determining prognosis of cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma: a prospective study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(8):713-720. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70178-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mourouzis C, Boynton A, Grant J, et al. Cutaneous head and neck SCCs and risk of nodal metastasis—UK experience. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2009;37(8):443-447. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2009.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karia PS, Han J, Schmults CD. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: estimated incidence of disease, nodal metastasis, and deaths from disease in the United States, 2012. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(6):957-966. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.11.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmults CD, Karia PS, Carter JB, Han J, Qureshi AA. Factors predictive of recurrence and death from cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a 10-year, single-institution cohort study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(5):541-547. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.2139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roozeboom MH, Lohman BG, Westers-Attema A, et al. Clinical and histological prognostic factors for local recurrence and metastasis of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: analysis of a defined population. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93(4):417-421. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson TG, Ashton RE. Low incidence of metastasis and recurrence from cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma found in a UK population: do we need to adjust our thinking on this rare but potentially fatal event? J Surg Oncol. 2017;116(6):783-788. doi: 10.1002/jso.24707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roscher I, Falk RS, Vos L, et al. Validating 4 staging systems for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma using population-based data: a nested case-control study. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(4):428-434. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.6428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Venables ZC, Autier P, Nijsten T, et al. Nationwide incidence of metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in England. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(3):298-306. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rizvi SMH, Aagnes B, Holdaas H, et al. Long-term change in the risk of skin cancer after organ transplantation: a population-based, nation-wide cohort study. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(12):1270-1277. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.2984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park CK, Fung K, Austin PC, et al. Incidence and risk factors of keratinocyte carcinoma after first solid organ transplant in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(9):1041-1048. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.0692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garrett GL, Blanc PD, Boscardin J, et al. Incidence of and risk factors for skin cancer in organ transplant recipients in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(3):296-303. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wehner MR, Niu J, Wheless L, et al. Risks of multiple skin cancers in organ transplant recipients: a cohort study in 2 administrative data sets. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(12):1447-1455. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.4148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Genders RE, Weijns ME, Dekkers OM, Plasmeijer EI. Metastasis of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in organ transplant recipients and the immunocompetent population: is there a difference? a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(5):828-841. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eigentler TK, Leiter U, Häfner HM, Garbe C, Röcken M, Breuninger H. Survival of patients with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: results of a prospective cohort study. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137(11):2309-2315. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.06.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eigentler TK, Dietz K, Leiter U, Häfner HM, Breuninger H. What causes the death of patients with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma? a prospective analysis in 1400 patients. Eur J Cancer. 2022;172:182-190. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2022.05.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larsen IK, Småstuen M, Johannesen TB, et al. Data quality at the Cancer Registry of Norway: an overview of comparability, completeness, validity and timeliness. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(7):1218-1231. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453-1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cancer Registry of Norway . Cancer in Norway 2021: Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Survival and Prevalence in Norway. Cancer Registry of Norway; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 20.This is Norway 2021. Statistics Norway; 2021. Accessed June 11, 2023. https://www.ssb.no/en/befolkning/folketall/artikler/this-is-norway-2021/_/attachment/inline/bd30e829-45de-403f-bbf3-347a26901290:872e3b5cfe07915e708954d68ed90e313c6e0ab7/This%20is%20Norway%202021web.pdf

- 21.Berry SD, Ngo L, Samelson EJ, Kiel DP. Competing risk of death: an important consideration in studies of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(4):783-787. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02767.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harwood CA, Toland AE, Proby CM, et al. ; KeraCon Consortium . The pathogenesis of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in organ transplant recipients. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(5):1217-1224. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wisgerhof HC, Edelbroek JR, de Fijter JW, et al. Subsequent squamous- and basal-cell carcinomas in kidney-transplant recipients after the first skin cancer: cumulative incidence and risk factors. Transplantation. 2010;89(10):1231-1238. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181d84cdc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flohil SC, van der Leest RJ, Arends LR, de Vries E, Nijsten T. Risk of subsequent cutaneous malignancy in patients with prior keratinocyte carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(10):2365-2375. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tokez S, Hollestein L, Louwman M, Nijsten T, Wakkee M. Incidence of multiple vs first cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma on a nationwide scale and estimation of future incidences of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(12):1300-1306. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.3677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wehner MR. Underestimation of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma incidence, even in cancer registries. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(12):1290-1291. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.3678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wheless L, Anand N, Hanlon A, Chren MM. Differences in skin cancer rates by transplanted organ type and patient age after organ transplant in White patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158(11):1287-1292. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.3878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gjersvik P. How to take the skin cancer risk of your transplant patient seriously. Transpl Int. 2019;32(12):1244-1246. doi: 10.1111/tri.13541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jambusaria-Pahlajani A, Crow LD, Lowenstein S, et al. Predicting skin cancer in organ transplant recipients: development of the SUNTRAC screening tool using data from a multicenter cohort study. Transpl Int. 2019;32(12):1259-1267. doi: 10.1111/tri.13493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gómez-Tomás Á, Bouwes Bavinck JN, Genders R, et al. External validation of the Skin and UV Neoplasia Transplant Risk Assessment Calculator (SUNTRAC) in a large European solid organ transplant recipient cohort. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159(1):29-36. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.4820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Migden MR, Rischin D, Schmults CD, et al. PD-1 Blockade with cemiplimab in advanced cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(4):341-351. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robsahm TE, Helsing P, Veierød MB. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in Norway 1963-2011: increasing incidence and stable mortality. Cancer Med. 2015;4(3):472-480. doi: 10.1002/cam4.404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Venables ZC, Tokez S, Hollestein LM, et al. Validation of four cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma staging systems using nationwide data. Br J Dermatol. 2022;186(5):835-842. doi: 10.1111/bjd.20909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bakken IJ, Ellingsen CL, Pedersen AG, et al. Comparison of data from the Cause of Death Registry and the Norwegian Patient Register. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2015;135(21):1949-1953. doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.14.0847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Secondary Analyses Restricted to Organ Transplant Recipients (OTRs) and Non-OTR Patients Diagnosed With Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma (cSCC) in the Period 1968-2012

Data Sharing Statement