This cross-sectional study examines differences in the prevalence of suicidal thoughts and behaviors across intersectional combinations of gender, sexual orientation, race and ethnicity, and rurality among US adults.

Key Points

Question

Does the prevalence of suicide ideation, plan, and attempt vary across intersectional combinations of gender, sexual orientation, race and ethnicity, and rurality?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study of 189 800 adults based on 5 years of data from an annual population-based US survey, prevalence of suicide ideation, plan, and attempt were highest among Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black bisexual women living in nonmetropolitan counties.

Meaning

The findings suggest that Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black bisexual women living in nonmetropolitan counties may experience high prevalence of suicide ideation, plan, and attempt, possibly due to experiencing compounding forms of structural discrimination.

Abstract

Importance

Suicidal thoughts and behaviors (STBs) are major public health problems, and some social groups experience disproportionate STB burden. Studies assessing STB inequities for single identities (eg, gender or sexual orientation) cannot evaluate intersectional differences and do not reflect that the causes of inequities are due to structural-level (vs individual-level) processes.

Objective

To examine differences in STB prevalence at the intersection of gender, sexual orientation, race and ethnicity, and rurality.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional study used adult data from the 2015-2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), a population-based sample of noninstitutionalized US civilians. Data were analyzed from July 2022 to March 2023.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Outcomes included past-year suicide ideation, plan, and attempt, each assessed with a single question developed for the NSDUH. Intersectional multilevel analysis of individual heterogeneity and discriminatory accuracy (MAIHDA) models were estimated, in which participants were nested within social strata defined by all combinations of gender, sexual orientation, race and ethnicity, and rurality; outcome prevalence estimates were obtained for each social stratum. Social strata were conceptualized as proxies for exposure to structural forms of discrimination that contribute to health advantages or disadvantages (eg, sexism, racism).

Results

The analytic sample included 189 800 adults, of whom 46.5% were men; 53.5%, women; 4.8%, bisexual; 93.0%, heterosexual; 2.2%, lesbian or gay; 18.8%, Hispanic; 13.9%, non-Hispanic Black; and 67.2%, non-Hispanic White. A total of 44.6% were from large metropolitan counties; 35.5%, small metropolitan counties; and 19.9%, nonmetropolitan counties. There was a complex social patterning of STB prevalence that varied across social strata and was indicative of a disproportionate STB burden among multiply marginalized participants. Specifically, the highest estimated STB prevalence was observed among Hispanic (suicide ideation: 18.1%; 95% credible interval [CrI], 13.5%-24.3%) and non-Hispanic Black (suicide plan: 7.9% [95% CrI, 4.5%-12.1%]; suicide attempt: 3.3% [95% CrI, 1.4%-6.2%]) bisexual women in nonmetropolitan counties.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cross-sectional study, intersectional exploratory analyses revealed that STB prevalence was highest among social strata including multiply marginalized individuals (eg, Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black bisexual women) residing in more rural counties. The findings suggest that considering and intervening in both individual-level (eg, psychiatric disorders) and structural-level (eg, structural discrimination) processes may enhance suicide prevention and equity efforts.

Introduction

Millions of people experience suicide ideation, suicide plans, and suicide attempts every year.1 Suicidal thoughts and behaviors (STBs) are a major public health problem population-wide, but some groups experience a disproportionate burden of STBs.2 For instance, cisgender women are 1.2 to 3 times more likely than cisgender men to experience STBs (excluding suicide deaths).3 Sexual minority populations are 3 to 6 times more likely than heterosexual populations to experience STBs.4,5 American Indian and Alaska Native individuals have the highest STB prevalence of all racial and ethnic groups, although STB prevalence is increasing for Black and Hispanic young adults.6

When viewing STB inequities for women, sexual minority populations, and racial and ethnic minority groups through the lens of Black feminist scholarship’s intersectionality theory,7 these inequities arise not due to the identities themselves but due to mutually constitutive forms of structural discrimination based on these identities.8 Structural discrimination is a fundamental cause of health inequities and occurs when interlocking systems of power, privilege, and oppression are embedded into policies, cultural norms and practices, and beliefs. These policies and practices compound and reinforce one another such that more socially advantaged groups enjoy more health advantages while more socially oppressed groups experience more health disadvantages.9 For instance, abortion restrictions are a manifestation of structural sexism10 that are associated with STBs among women.11 Legislation opposing gay rights is a manifestation of structural heterosexism12 that is associated with STBs in sexual minority populations.13 Racial and ethnic minority groups’ longstanding residential segregation and related correlates, such as quality of the built and social environment and opportunities for high-quality education and employment, are manifestations of structural racism that systemically reduce health care access, use, and quality14,15,16,17,18; limited health care access is thereby associated with STBs in racial and ethnic minority groups.14 These manifestations of structural discrimination intersect with one another and are associated with excess risk for health disadvantages for multiply marginalized groups.9 For example, abortion restrictions disproportionately harm Black women.19

Typically, STB inequities are investigated by 1 identity at a time. However, people possess multiple identities, each of which comes with varying degrees of advantage or disadvantage due to structural power, privilege, and oppression.20 Consequently, social groups defined by unique combinations of identities (ie, intersectional identities) are likely to experience differential risks for certain outcomes. These risk differences can only be captured through intersectional paradigms. Intersectional STB investigations may promote suicide prevention by (1) shifting intervention targets away from individual-level processes and toward the root causes (ie, power, privilege, and oppression) that disproportionately expose marginalized groups to STB risk factors and (2) identifying the intersectional groups at highest STB risk who may be in need of culturally tailored STB prevention and/or intervention programs.

Three studies assessed intersectional STB inequities based on gender, sexual orientation, and/or race.4,21,22 All used logistic regressions with an interaction term to quantify the intersectional association of multiple identities with STBs. Although quantifying intersectionality with interaction terms is common, it poses well-documented methodologic and theoretical challenges.23 Methodologically, traditional (ie, frequentist, single-level) regressions are not well equipped to handle increasing numbers of identity dimensions, they handle small subgroups poorly, and they do not simultaneously compare how STB prevalence differs for all intersectional groups, especially those experiencing privilege and disadvantage simultaneously. Theoretically, traditional regressions stray from intersectionality theory by (1) not explicitly recognizing that the cause of health inequities resides within social structures and (2) treating intersectional identities as if they can be broken down into their single constituent parts.23

These limitations can be addressed through multilevel analysis of individual heterogeneity and discriminatory accuracy (MAIHDA).8,24 MAIHDA is a bayesian multilevel modeling method that nests individuals within social strata defined by intersectional identities. Clustering by social strata operationalizes the assumption that people within the strata are exposed to a common set of social structures (eg, sexism, racism) that might be associated with differing degrees of STB risk and/or resilience.25,26,27 MAIHDA allows for comparison of outcome prevalence for every social stratum (ie, for every combination of advantaged or disadvantaged identities) and has been described as “an analytical standard in epidemiology” for quantitative intersectionality research.8,28,29,30,31 To our knowledge, the current study is the first to use MAIHDA to characterize intersectional STB prevalence. Specifically, we compared prevalence of suicide ideation, plans, and attempts at the intersection of gender, sexual orientation, race and ethnicity, and rurality. These exploratory comparisons may inform research determining structural factors associated with STB inequities.

We focused on rurality as an intersectional identity because there are rural-urban differences in stigma and health care access32,33 that further vary by sexual orientation and race and ethnicity and that could contribute to STBs. Among sexual minority populations, those living in rural areas report feeling more stigma related to their identity34 and experiencing more frequent violence and discrimination35 than those living in urban areas. Among rural adults overall, Black and Hispanic people are less likely than White people to have health care coverage and practitioners.36 Even when health care is available in rural areas, heterosexism and racism are major barriers to health care use for sexual minority and racial and ethnic minority groups.37,38 Being unable to access culturally responsive, affirming mental health care could exacerbate mental health problems and STBs for rural sexual minority and rural racial minority groups.14

In this study’s analyses, we treated identities (gender, sexual orientation, race and ethnicity, and rurality) as imperfect proxies for exposure to and experiences with structural discrimination (sexism, heterosexism, racism, and health care access inequities). We expected that STBs would be highest among those with the most marginalized identities due to compounding forms of structural discrimination and disadvantage.

Method

Participants

This cross-sectional study used data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), conducted annually among noninstitutionalized US civilians. Participants provide informed consent, complete an in-person interview, and are compensated. The NSDUH began assessing sexual orientation in 2015. For the current study, we used a data set that included combined data from the 2015-2019 NSDUH surveys. We excluded the following groups: individuals younger than 18 years as their sexual orientation was not assessed, those with missing or unknown sexual orientation, and racial and ethnic identity groups of small sample size. For each outcome, participants were also excluded if they answered anything other than yes or no to the items assessing suicide ideation, plan, or attempt. Methods to include complex survey weights in bayesian multilevel models are currently underdeveloped; thus, NSDUH complex survey design variables were not included in the analyses. Excluding these variables means that results of the current analyses should not be interpreted as being representative of the US population. The Pennsylvania State University institutional review board deemed this study as non–human participant research due to secondary analysis of deidentified data; thus, informed consent was not required for the current analyses (though participants provided informed consent for their original NSDUH participation). The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Measures

All respondents were asked about past-year suicide ideation through the question, “At any time in the past 12 months, that is from [date filled] up to and including today, did you seriously think about trying to kill yourself?” If respondents answered yes, they were asked about suicide plans and attempts, which were assessed through the questions, “During the past 12 months, did you make any plans to kill yourself?” and “During the past 12 months, did you try to kill yourself?” All outcomes included answer options of yes or no.

Gender

The NSDUH classifies respondents as male or female based on interviewer observation or direct inquiry. We used these categories as imperfect proxies for gender identities of man and woman.

Sexual Orientation

Sexual orientation was assessed with the question, “Which one of the following do you consider yourself to be?” Response options included in this analysis were “heterosexual, that is, straight,” “lesbian or gay,” or “bisexual.”

Race and Ethnicity

Race was assessed with the question, “Which of these groups best describes you?” Response options were American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Guamanian or Chamorro, Native Hawaiian, Other Pacific Islander, Samoan, White, and other. Participants were allowed to select more than 1 race. Ethnicity was assessed with the question, “Are you of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish descent?” The NSDUH combined race and ethnicity into a single variable with 7 categories: non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native, non-Hispanic Asian, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic multiracial, non-Hispanic Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and non-Hispanic White.

Given our focus on intersecting identities, sample sizes for people who were non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native, non-Hispanic Asian, non-Hispanic multiracial, and non-Hispanic Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander were too small to be stratified by gender, sexual orientation, and rurality (eTable 2 in Supplement 1). Thus, the analytic sample included only people who were non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, or non-Hispanic White.

Rurality

The NSDUH classifies participant county of residence as large metropolitan (population ≥1 million), small metropolitan (population <1 million), or nonmetropolitan. These classifications are based on US Department of Agriculture 2013 Rural-Urban Continuum Codes.

Covariates

Age and survey year were included as covariates. Including age as a covariate accounted for age differences in STB prevalence.22 Including survey year as a covariate accounted for potential year-to-year differences in STB prevalence.

Statistical Analysis

To implement MAIHDA, we fit 2-level bayesian multilevel logistic regression models. Individuals (level 1) were nested within social strata (level 2). We included 54 social strata based on all combinations of gender, sexual orientation, race and ethnicity, and rurality (eTable 1 in Supplement 1).

For each outcome, we estimated a null model with random intercepts for social strata. The model yielded 2 intersectional parameters. The first was the variance partition coefficient (VPC), which indicates the proportion of variance between strata. The greater the VPC, the more pronounced differences there are between (vs within) strata. The second parameter was stratum-specific STB predicted prevalence and 95% credible intervals (CrIs). Significant differences between strata are present when the 95% CrIs of 2 strata do not overlap. These were exploratory analyses to generate hypotheses for future intersectional investigations.

Analyses were conducted from July 2022 to March 2023 in R, version 4.1.1 (R Project for Statistical Computing).39 The brms package was used to fit models with bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo estimation.40 Vague prior probability distributions were specified for all parameters. Models included a burn-in period of 5000 iterations and 10 000 total iterations. eAppendix 1 in Supplement 1 includes further detail of our modeling approach. eAppendix 2 and eTables 3 and 4 in Supplement 1 include results and limitations of a pooled data set that includes NSDUH 2020 data. eAppendix 3 in Supplement 1 includes the code used for analyses.

Results

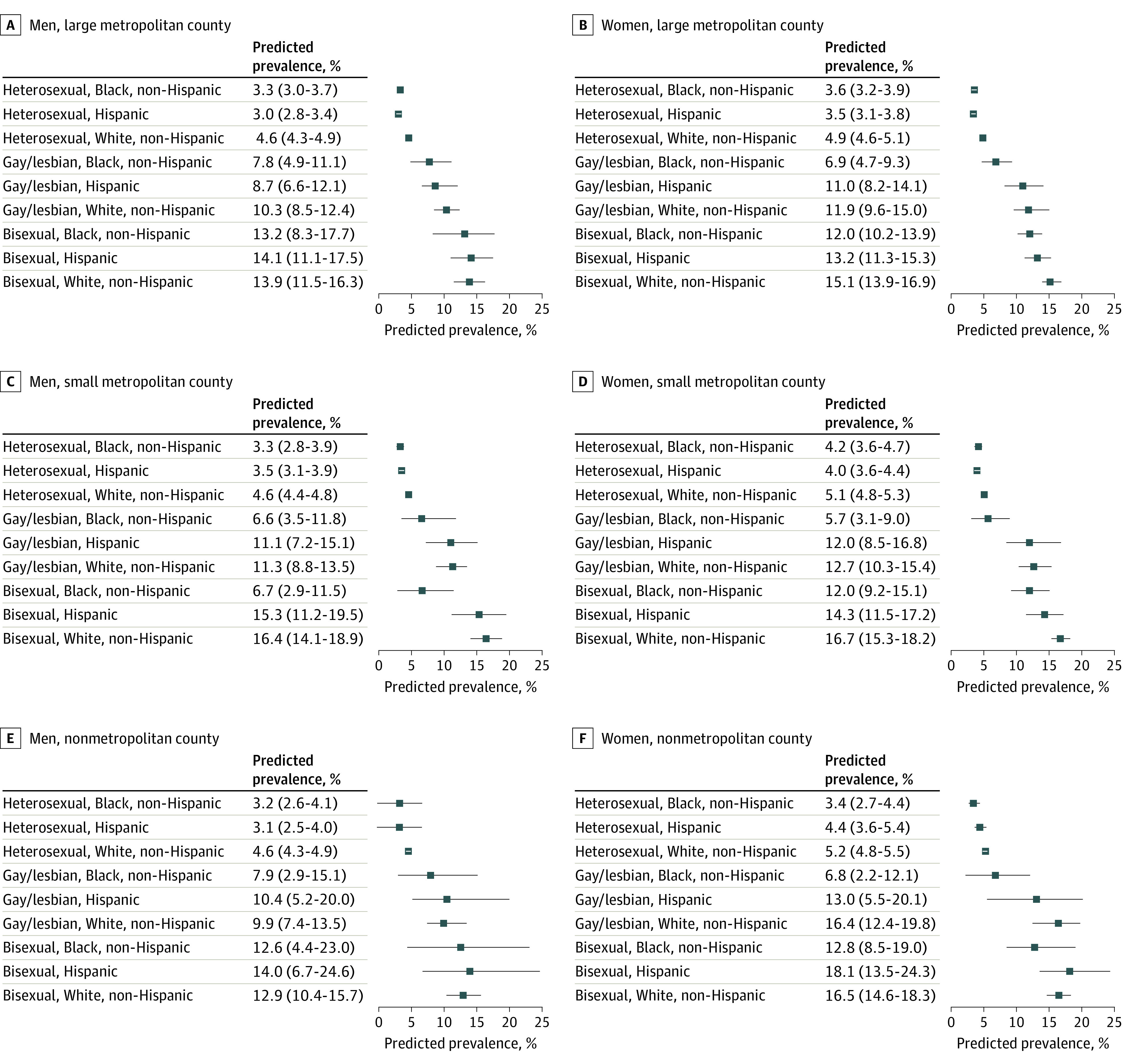

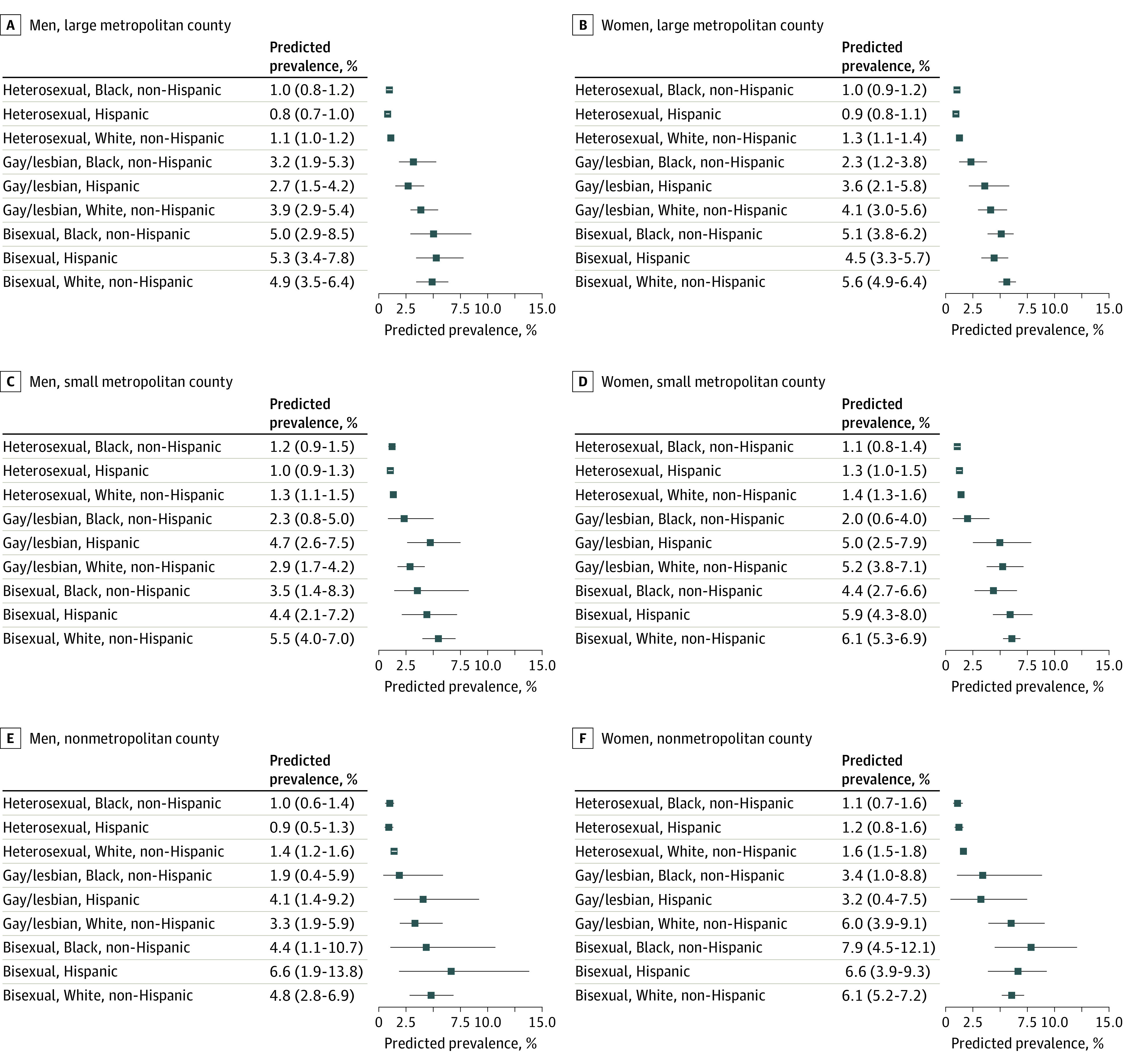

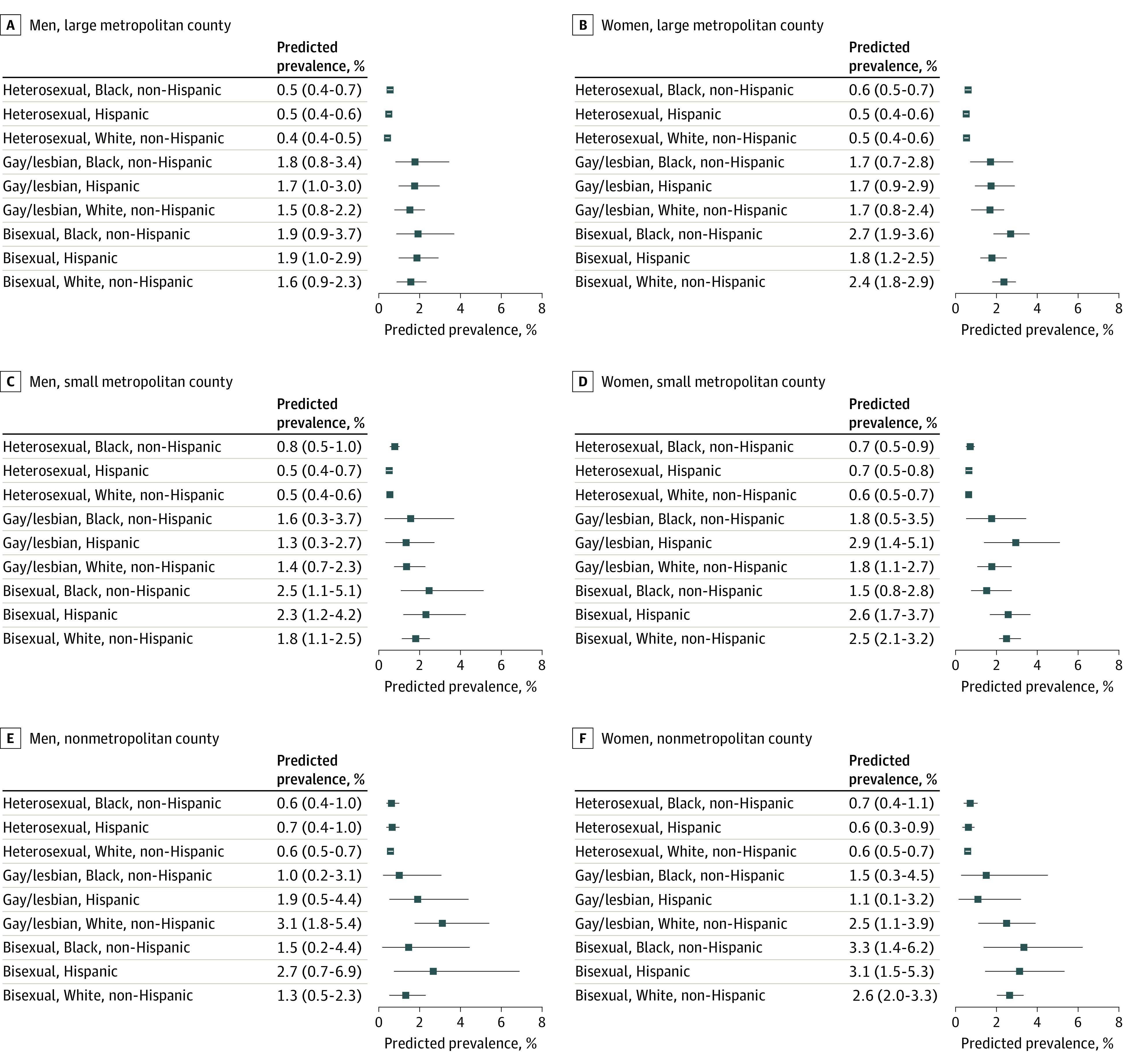

A total of 189 800 participants were included in the analysis, of whom 46.5% were men; 53.5%, women; 4.8%, bisexual; 93.0%, heterosexual; 2.2%, lesbian or gay; 18.8%, Hispanic; 13.9%, non-Hispanic Black; and 67.2%, non-Hispanic White. A total of 44.6% were from large metropolitan counties, 35.5% from small metropolitan counties, and 19.9% from nonmetropolitan counties (Table). The VPCs were 12.6% for suicide ideation, 16.2% for suicide plan, and 14.0% for suicide attempt, indicating that 12% to 16% of the variance in outcome prevalence was due to differences between strata. Prevalence estimates are detailed in Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3. The lowest predicted prevalence of suicide ideation and plan was among heterosexual Hispanic men in large metropolitan counties (suicide ideation: 3.0% [95% CrI, 2.8%-3.4%]; suicide plan: 0.8% [95% CrI, 0.7%-1.0%]]), and the lowest predicted prevalence of suicide attempt was among heterosexual White men in large metropolitan counties (0.4% [95% CrI, 0.4%-0.5%]). The highest predicted prevalence of suicide ideation was among bisexual Hispanic women in nonmetropolitan counties (18.1% [95% CrI, 13.5%-24.3%]), and the highest predicted prevalence of suicide plan and attempt was among bisexual Black women in nonmetropolitan counties (suicide plan: 7.9% [95% CrI, 4.5%-12.1%]; suicide attempt: 3.3% [95% CrI, 1.4%-6.2%]).

Table. Sociodemographic Characteristics and Observed Prevalence of Suicide Ideation, Plan, and Attempt for the Analytic Sample.

| Characteristic | Participants, No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 189 800) | Suicide ideationa | Suicide plana | Suicide attempta | |

| Gender identity | ||||

| Man | 88 298 (46.5) | 4835 (5.5) | 1447 (1.6) | 674 (0.8) |

| Woman | 101 502 (53.5) | 6738 (6.7) | 2158 (2.1) | 1033 (1.0) |

| Sexual orientation | ||||

| Bisexual | 9140 (4.8) | 2035 (22.4) | 820 (9.0) | 389 (4.3) |

| Gay or lesbian | 4165 (2.2) | 583 (14.1) | 220 (5.5) | 120 (2.9) |

| Heterosexual | 176 495 (93.0) | 8955 (5.1) | 2565 (1.5) | 1198 (0.7) |

| County type | ||||

| Large metropolitan | 84 574 (44.6) | 4867 (5.8) | 1440 (1.7) | 700 (0.8) |

| Small metropolitan | 67 400 (35.5) | 4328 (6.4) | 1371 (2.0) | 655 (1.0) |

| Nonmetropolitan | 37 826 (19.9) | 2376 (6.3) | 794 (2.1) | 352 (0.9) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 26 477 (13.9) | 1365 (5.2) | 457 (1.7) | 286 (1.1) |

| Hispanic | 35 767 (18.8) | 2007 (5.6) | 637 (1.8) | 356 (1.0) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 127 556 (67.2) | 8201 (6.4) | 2511 (2.0) | 1065 (0.8) |

| Age, y | ||||

| 18-25 | 60 851 (32.1) | 6196 (10.2) | 2080 (3.4) | 1096 (1.8) |

| 26-34 | 38 452 (20.3) | 2233 (5.8) | 621 (1.6) | 270 (0.7) |

| 35-49 | 50 043 (26.4) | 2094 (4.2) | 616 (1.2) | 248 (0.5) |

| 50-64 | 23 048 (12.1) | 728 (3.2) | 215 (0.9) | 63 (0.3) |

| ≥65 | 17 406 (9.2) | 322 (1.9) | 73 (0.4) | 30 (0.2) |

| Year | ||||

| 2015 | 38 594 (20.3) | 2091 (5.4) | 624 (1.6) | 331 (0.9) |

| 2016 | 37 915 (20.0) | 2132 (5.6) | 644 (1.7) | 319 (0.8) |

| 2017 | 37 665 (19.8) | 2264 (6.0) | 728 (1.9) | 347 (0.9) |

| 2018 | 37 978 (20.0) | 2396 (6.3) | 778 (2.1) | 354 (0.9) |

| 2019 | 37 648 (19.8) | 2690 (7.2) | 831 (2.2) | 356 (0.9) |

| Outcomeb | NA | 11 573 (6.1) | 3605 (1.9) | 1707 (0.9) |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Values indicate the number (percentage) of the outcome among people with a given identity or characteristic.

Values indicate the number (percentage) of the overall sample.

Figure 1. Predicted Prevalence of Suicide Ideation at the Intersections of Gender, Sexual Orientation, Race and Ethnicity, and Rurality.

Estimates are adjusted for age category and survey year. Whiskers represent 95% credible intervals.

Figure 2. Predicted Prevalence of Suicide Plan at the Intersections of Gender, Sexual Orientation, Race and Ethnicity, and Rurality.

Estimates are adjusted for age category and survey year. Whiskers represent 95% credible intervals.

Figure 3. Predicted Prevalence of Suicide Attempt at the Intersections of Gender, Sexual Orientation, Race and Ethnicity, and Rurality.

Estimates are adjusted for age category and survey year. Whiskers represent 95% credible intervals.

Between-Group Differences for Sexual Orientation

As shown in Figure 1, across gender identities and most racial and ethnic identities and rurality levels, sexual minority populations had a significantly higher predicted prevalence of suicide ideation than heterosexual populations. An exception to this pattern was that for Black men in small metropolitan counties, predicted prevalence of suicide ideation was similar among heterosexual, gay, and bisexual men. Sexual minority populations also had higher predicted prevalence of suicide plan and attempt than heterosexual populations, although the cell sizes and outcome prevalence were small for some strata, which contributed to some overlapping 95% CrIs (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Intersectional Differences

There were intersectional differences in STB predicted prevalence among sexual minority individuals (Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3). These differences varied across combinations of gender, race and ethnicity, and rurality.

Bisexual vs Gay or Lesbian Individuals and White vs Black Individuals

Among Black women in large metropolitan and small metropolitan counties, the predicted prevalence of suicide ideation was higher among bisexual individuals vs lesbian or gay individuals (Figure 1). As shown in Figure 1, among lesbian women living in any county type, the predicted prevalence of suicide ideation was significantly higher among those who were White than among those who were Black. The predicted prevalence of suicide ideation was also significantly higher (1) among White bisexual women than among Black bisexual women in large and small metropolitan counties and (2) among White bisexual men than among Black bisexual men in small metropolitan counties.

Nonmetropolitan vs Metropolitan Counties

As shown in Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3, among sexual minority women, the predicted prevalence of suicide ideation, plan, and attempt tended to be descriptively higher in nonmetropolitan or small metropolitan counties compared with large metropolitan counties, although several 95% CrIs overlapped. Among Hispanic sexual minority men, the predicted prevalence of suicide plan was descriptively higher for those in nonmetropolitan or small metropolitan counties than for those in large metropolitan counties, although the 95% CrIs overlapped.

Discussion

This exploratory cross-sectional study quantified STB inequities at the intersections of gender, sexual orientation, race and ethnicity, and rurality. The findings indicate that between 12% and 16% of the variance in STB prevalence was attributable to differences between strata. This is a notable proportion of variance to be explained by intersectional stratification41 and suggests that structural processes (eg, sexism, heterosexism, racism, and health care access inequities)25,26,27—not just individual-level processes (eg, emotion regulation)—may be important contributors to the social patterning of STBs. To best mitigate inequities, the psychiatry field must expand suicide prevention efforts beyond individual-level risk processes by considering and directly intervening on structural contributors.

The predicted prevalence of STBs was highest for Black and Hispanic bisexual women in nonmetropolitan counties. This finding may be due to this group’s intersectional socioecological contexts. At the intersection of sexual orientation and race, individuals belonging to both sexual minority and racial and ethnic minority groups experience disparities in socioeconomic stability42 and health care access,43 which could contribute to STBs.44,45 At the intersection of sexual orientation and gender, bisexual women have the highest prevalence of STBs5 (and other forms of violence46) compared with other sexual minority groups. While lesbian and bisexual women share exposure to some structural processes that are associated with increased STB risk (eg, sexism, heterosexism), bisexual women also experience biphobia and bierasure.47 This confluence of stressors may further vary across the rural-urban continuum, with nonmetropolitan or rural areas often being more stigmatizing of sexual minority identities and having fewer health care resources than large metropolitan or urban areas.34,35

Although the predicted prevalence of STBs was generally higher for strata with more marginalized identities, this does not universally mean that the more disadvantaged identities a group possesses, the higher their STB prevalence will be. This also does not mean that intersectional effects operate similarly for all social identity dimensions. For example, our findings for most sexual minority strata were in line with previous single-axis findings: sexual minority individuals had significantly higher predicted prevalence of past-year STBs than did heterosexual individuals.4,21,22 However, our multiple-axis perspective found that the predicted prevalence of STBs was similar for Black men who were heterosexual, gay, or bisexual in small metropolitan counties and similar for Black women who were lesbian or heterosexual in nonmetropolitan and small metropolitan counties. From a single-axis perspective, 1 potential explanation for these findings is that some Black communities experience unique STB resiliencies. Conversely, an intersectional perspective shows that risks and resiliencies are not universal. Exposure to and experiences with structural racism and heterosexism may be associated with higher STB prevalence for some Black sexual minority groups than expected. In the present study, Black gay men, Black bisexual women, and Black lesbian women in large metropolitan counties had a significantly higher predicted prevalence of suicide ideation than did their Black heterosexual counterparts. Similarly, although there are well-accepted gender3 and rurality48 differences in STB prevalence, our intersectional findings did not support that women or people living in rural areas have universally higher STB prevalence compared with men or people living in urban areas.49 These examples highlight the nuances that intersectional investigations quantify.

The findings have implications for improving STB prevention for structurally oppressed groups. Historically, the mental health field has viewed STB prevention as occurring through individual-level interventions (eg, reducing emotion dysregulation). However, STB prevention may also come in the form of structural-level interventions.37 For instance, repealing policies that disproportionately impact individuals belonging to both sexual minority and racial and ethnic minority groups (eg, HIV criminalization laws50) may be associated with reduced STB consequences of both structural racism and structural heterosexism.51 Clinician-training programs could incorporate and enhance structural competencies.52 When assessing STBs, clinicians should consider that factors associated with STBs (eg, high anxiety) could be due to structural factors, not just individual factors.53 Incorporating structural discrimination–focused material into psychological interventions (eg, psychoeducation, increasing identity pride, and coping with structural discrimination) may improve effectiveness and ultimately be associated with reduced STBs.54,55

Strengths and Limitations

Study strengths include the large sample size and the novel analytic approach. The study also has limitations. First, we used a binary gender variable, yet gender is not binary.56 The prevalence of STBs is disproportionately high for transgender, nonbinary, and gender-nonconforming people.57 Intersectional investigations of factors associated with STBs in gender-diverse people are critically needed and could identify specific subgroups at the highest STB risk (eg, American Indian transgender women).58 Similarly, race and ethnicity are social constructs, and NSDUH coding does not reflect the diversity of racial and ethnic identities (eg, African vs Afro-Caribbean). Second, due to small sample sizes, our analyses did not include non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, multiracial, or Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander individuals. The exclusion of American Indian and Alaska Native individuals is particularly limiting given these groups’ elevated STB rates and the intersectional patterning of suicide deaths for rural American Indian and Alaska Native individuals.59 Third, sample sizes for sexual minority men in nonmetropolitan counties were small. Methodologic innovations to handle small strata within MAIHDA are needed.31 In the absence of such innovations, comparisons among strata with small cell sizes or low outcome prevalence should be interpreted with caution. Fourth, some 95% CrIs were wide, likely due to individual differences and/or unmodeled dimensions of social context (eg, socioeconomic status). Fifth, although structural-level processes (eg, sexism, heterosexism, racism, and limited health care access) are associated with increased STB prevalence,11,13,14 we did not measure these processes and instead used proxies (gender, sexual orientation, race and ethnicity, and rurality). Future work should examine whether these structural processes explain the STB patterns documented here. Sixth, the NSDUH does not include data on suicide deaths. Intersectional investigations on the social patterning of suicide deaths are needed, as the groups at highest risk for nonfatal STBs may not be the same groups at highest risk for suicide deaths.

Conclusions

In this cross-sectional study, STB prevalence differed at the intersections of gender, sexual orientation, race and ethnicity, and rurality. Prevalence of STBs was highest among Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black bisexual women residing in more rural counties. These findings suggest that STB inequities are not adequately described when considering identity dimensions individually. Shifting investigations of STB inequities from single-axis to intersectional paradigms may lead to more nuanced knowledge of the structural processes of power, privilege, and disadvantage that contribute to STB inequities for structurally oppressed groups. Moreover, STB prevention and intervention approaches should expand to include both individual-level and structural-level processes contributing to STBs.

eAppendix 1. Calculation of Model Parameters

eAppendix 2. Description of NSDUH 2020 Methodological Changes and Their Consequences for Analyses

eTable 1. Size of Each Social Strata and Observed Prevalence of Suicide Ideation, Plan, and Attempt, Excluding 2020 Data

eTable 2. Size of the Social Strata That Were Excluded From Analyses due to Small Sample Sizes, Excluding 2020 Data

eTable 3. Size of Each Social Strata and Observed Prevalence of Suicide Ideation, Plan, and Attempt, Including 2020 Data

eTable 4. Predicted Prevalence of Suicide Ideation, Suicide Plan, and Suicide Attempt, Including 2020 Data

eAppendix 3. Code Used for Analyses

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Suicide data and statistics. June 28, 2022. Accessed November 23, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/suicide-data-statistics.html

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Disparities in suicide. Accessed November 2, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/facts/disparities-in-suicide.html

- 3.Schrijvers DL, Bollen J, Sabbe BGC. The gender paradox in suicidal behavior and its impact on the suicidal process. J Affect Disord. 2012;138(1-2):19-26. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.03.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramchand R, Schuler MS, Schoenbaum M, Colpe L, Ayer L. Suicidality among sexual minority adults: gender, age, and race/ethnicity differences. Am J Prev Med. 2022;62(2):193-202. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2021.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salway T, Ross LE, Fehr CP, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of disparities in the prevalence of suicide ideation and attempt among bisexual populations. Arch Sex Behav. 2019;48(1):89-111. doi: 10.1007/s10508-018-1150-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stone DM, Mack KA, Qualters J. Notes from the field: recent changes in suicide rates, by race and ethnicity and age group—United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(6):160-162. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7206a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics [1989]. In: Bartlett KT, Kennedy R, eds. Feminist Legal Theory: Readings in Law and Gender. Routledge; 1991:139-167. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evans CR, Williams DR, Onnela JP, Subramanian SV. A multilevel approach to modeling health inequalities at the intersection of multiple social identities. Soc Sci Med. 2018;203:64-73. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowleg L. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: intersectionality-an important theoretical framework for public health. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1267-1273. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Homan P. Structural sexism and health in the United States: a new perspective on health inequality and the gender system. Am Sociol Rev. 2019;84(3):486-516. doi: 10.1177/0003122419848723 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zandberg J, Waller R, Visoki E, Barzilay R. Association between state-level access to reproductive care and suicide rates among women of reproductive age in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2023;80(2):127-134. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.4394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hatzenbuehler ML. Structural stigma and the health of lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2014;23(2):127-132. doi: 10.1177/0963721414523775 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pachankis JE, Hatzenbuehler ML, Bränström R, et al. Structural stigma and sexual minority men’s depression and suicidality: a multilevel examination of mechanisms and mobility across 48 countries. J Abnorm Psychol. 2021;130(7):713-726. doi: 10.1037/abn0000693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheehan AE, Walsh RFL, Liu RT. Racial and ethnic differences in mental health service utilization in suicidal adults: a nationally representative study. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;107:114-119. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.10.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caraballo C, Ndumele CD, Roy B, et al. Trends in racial and ethnic disparities in barriers to timely medical care among adults in the US, 1999 to 2018. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(10):e223856. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.3856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(5):404-416. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50068-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Landrine H, Corral I. Separate and unequal: residential segregation and Black health disparities. Ethn Dis. 2009;19(2):179-184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453-1463. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Redd SK, Mosley EA, Narasimhan S, et al. Estimation of multiyear consequences for abortion access in Georgia under a law limiting abortion to early pregnancy. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(3):e231598. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.1598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moradi B, Grzanka PR. Using intersectionality responsibly: toward critical epistemology, structural analysis, and social justice activism. J Couns Psychol. 2017;64(5):500-513. doi: 10.1037/cou0000203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baiden P, LaBrenz CA, Asiedua-Baiden G, Muehlenkamp JJ. Examining the intersection of race/ethnicity and sexual orientation on suicidal ideation and suicide attempt among adolescents: findings from the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. J Psychiatr Res. 2020;125:13-20. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.02.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Layland EK, Exten C, Mallory AB, Williams ND, Fish JN. Suicide attempt rates and associations with discrimination are greatest in early adulthood for sexual minority adults across diverse racial and ethnic groups. LGBT Health. 2020;7(8):439-447. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2020.0142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evans CR. Adding interactions to models of intersectional health inequalities: comparing multilevel and conventional methods. Soc Sci Med. 2019;221:95-105. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.11.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merlo J. Multilevel analysis of individual heterogeneity and discriminatory accuracy (MAIHDA) within an intersectional framework. Soc Sci Med. 2018;203:74-80. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coimbra BM, Hoeboer CM, Yik J, Mello AF, Mello MF, Olff M. Meta-analysis of the effect of racial discrimination on suicidality. SSM Popul Health. 2022;20:101283. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2022.101283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cai Z, Canetto SS, Chang Q, Yip PSF. Women’s suicide in low-, middle-, and high-income countries: do laws discriminating against women matter? Soc Sci Med. 2021;282:114035. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marzetti H, McDaid L, O’Connor R. “Am I really alive?” understanding the role of homophobia, biphobia and transphobia in young LGBT+ people’s suicidal distress. Soc Sci Med. 2022;298:114860. doi: 10.1016/socscimed.2022.114860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merlo J. Invited commentary: multilevel analysis of individual heterogeneity-a fundamental critique of the current probabilistic risk factor epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180(2):208-212. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beccia AL, Baek J, Austin SB, Jesdale WM, Lapane KL. Eating-related pathology at the intersection of gender identity and expression, sexual orientation, and weight status: an intersectional multilevel analysis of individual heterogeneity and discriminatory accuracy (MAIHDA) of the Growing Up Today Study cohorts. Soc Sci Med. 2021;281:114092. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keller L, Lüdtke O, Preckel F, Brunner M. Educational inequalities at the intersection of multiple social categories: an introduction and systematic review of the multilevel analysis of individual heterogeneity and discriminatory accuracy (MAIHDA) approach. Educ Psychol Rev. 2023;35:31. doi: 10.1007/s10648-023-09733-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zubizarreta D, Beccia AL, Trinh MH, Reynolds CA, Reisner SL, Charlton BM. Human papillomavirus vaccination disparities among US college students: an intersectional multilevel analysis of individual heterogeneity and discriminatory accuracy (MAIHDA). Soc Sci Med. 2022;301:114871. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andrilla CHA, Patterson DG, Garberson LA, Coulthard C, Larson EH. Geographic variation in the supply of selected behavioral health providers. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(6)(suppl 3):S199-S207. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poon CS, Saewyc EM. Out yonder: sexual-minority adolescents in rural communities in British Columbia. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(1):118-124. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.122945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swank E, Frost D, Fahs B. Rural location and exposure to minority stress among sexual minorities in the United States. Psychol Sex. 2012;3:226-243. doi: 10.1080/19419899.2012.700026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swank E, Fahs B, Frost DM. Region, social identities, and disclosure practices as predictors of heterosexist discrimination against sexual minorities in the United States. Sociol Inq. 2013;83(2):238-258. doi: 10.1111/soin.12004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.James CV, Moonesinghe R, Wilson-Frederick SM, Hall JE, Penman-Aguilar A, Bouye K. Racial/ethnic health disparities among rural adults—United States, 2012-2015. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017;66(23):1-9. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6623a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alvarez K, Polanco-Roman L, Samuel Breslow A, Molock S. Structural racism and suicide prevention for ethnoracially minoritized youth: a conceptual framework and illustration across systems. Am J Psychiatry. 2022;179(6):422-433. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.21101001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holt NR, Botelho E, Wolford-Clevenger C, Clark KA. Previous mental health care and help-seeking experiences: perspectives from sexual and gender minority survivors of near-fatal suicide attempts. Psychol Serv. Published online February 9, 2023. doi: 10.1037/ser0000745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.R Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Version 4.1.1. Published online 2021. Accessed July 7, 2022. https://www.R-project.org/

- 40.Bürkner PC. brms: An R package for bayesian multilevel models using Stan. J Stat Softw. 2017;80(1):1-28. doi: 10.18637/jss.v080.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Axelsson Fisk S, Mulinari S, Wemrell M, Leckie G, Perez Vicente R, Merlo J. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Sweden: an intersectional multilevel analysis of individual heterogeneity and discriminatory accuracy. SSM Popul Health. 2018;4:334-346. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2018.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilson BDM, Bouton L, Mallory C. Racial differences among LGBT adults in the US: LGBT well-being at the intersection of race. UCLA School of Law Williams Institute. 2022. Accessed March 15, 2023. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/LGBT-Race-Comparison-Jan-2022.pdf

- 43.Krehely J. How to close the LGBT health disparities gap: disparities by race and ethnicity. Center for American Progress. 2009. Accessed March 15, 2023. https://cdn.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/issues/2009/12/pdf/lgbt_health_disparities_race.pdf?_ga=2.202414361.921803619.1678807341-415462581.1678807341

- 44.Sareen J, Afifi TO, McMillan KA, Asmundson GJG. Relationship between household income and mental disorders: findings from a population-based longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(4):419-427. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tondo L, Albert MJ, Baldessarini RJ. Suicide rates in relation to health care access in the United States: an ecological study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(4):517-523. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v67n0402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Coston BM. Power and inequality: intimate partner violence against bisexual and non-monosexual women in the United States. J Interpers Violence. 2021;36(1-2):381-405. doi: 10.1177/0886260517726415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McCann E, Brown MJ, Taylor J. The views and experiences of bisexual people regarding their psychosocial support needs: a qualitative evidence synthesis. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2021;28(3):430-443. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ivey-Stephenson AZ, Crosby AE, Jack SPD, Haileyesus T, Kresnow-Sedacca MJ. Suicide trends among and within urbanization levels by sex, race/ethnicity, age group, and mechanism of death—United States, 2001-2015. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017;66(18):1-16. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6618a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peltzman T, Gottlieb DJ, Levis M, Shiner B. The role of race in rural-urban suicide disparities. J Rural Health. 2022;38(2):346-354. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baugher AR, Whiteman A, Jeffries WL, Finlayson T, Lewis R, Wejnert C; NHBS Study Group. Black men who have sex with men living in states with HIV criminalization laws report high stigma, 23 US cities, 2017. AIDS. 2021;35(10):1637-1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.English D, Boone CA, Carter JA, et al. Intersecting structural oppression and suicidality among Black sexual minority male adolescents and emerging adults. J Res Adolesc. 2022;32(1):226-243. doi: 10.1111/jora.12726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Metzl JM, Hansen H. Structural competency: theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:126-133. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Molock SD, Boyd RC, Alvarez K, et al. Culturally responsive assessment of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in youth of color. Am Psychol. Published online March 13, 2023. doi: 10.1037/amp0001140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beard C, Kirakosian N, Silverman AL, Winer JP, Wadsworth LP, Björgvinsson T. Comparing treatment response between LGBQ and heterosexual individuals attending a CBT- and DBT-skills-based partial hospital. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2017;85(12):1171-1181. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rimes KA, Ion D, Wingrove J, Carter B. Sexual orientation differences in psychological treatment outcomes for depression and anxiety: national cohort study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2019;87(7):577-589. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.American Psychological Association . Guidelines for psychological practice with transgender and gender nonconforming people. Am Psychol. 2015;70(9):832-864. doi: 10.1037/a0039906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cramer RJ, Kaniuka AR, Yada FN, et al. An analysis of suicidal thoughts and behaviors among transgender and gender diverse adults. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2022;57(1):195-205. doi: 10.1007/s00127-021-02115-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Adams NJ, Vincent B. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors among transgender adults in relation to education, ethnicity, and income: a systematic review. Transgend Health. 2019;4(1):226-246. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2019.0009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stone D, Trinh E, Zhou H, et al. Suicides among American Indian or Alaska Native persons—National Violent Death Reporting System, United States, 2015–2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(37):1161-1168. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7137a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix 1. Calculation of Model Parameters

eAppendix 2. Description of NSDUH 2020 Methodological Changes and Their Consequences for Analyses

eTable 1. Size of Each Social Strata and Observed Prevalence of Suicide Ideation, Plan, and Attempt, Excluding 2020 Data

eTable 2. Size of the Social Strata That Were Excluded From Analyses due to Small Sample Sizes, Excluding 2020 Data

eTable 3. Size of Each Social Strata and Observed Prevalence of Suicide Ideation, Plan, and Attempt, Including 2020 Data

eTable 4. Predicted Prevalence of Suicide Ideation, Suicide Plan, and Suicide Attempt, Including 2020 Data

eAppendix 3. Code Used for Analyses

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement