Summary

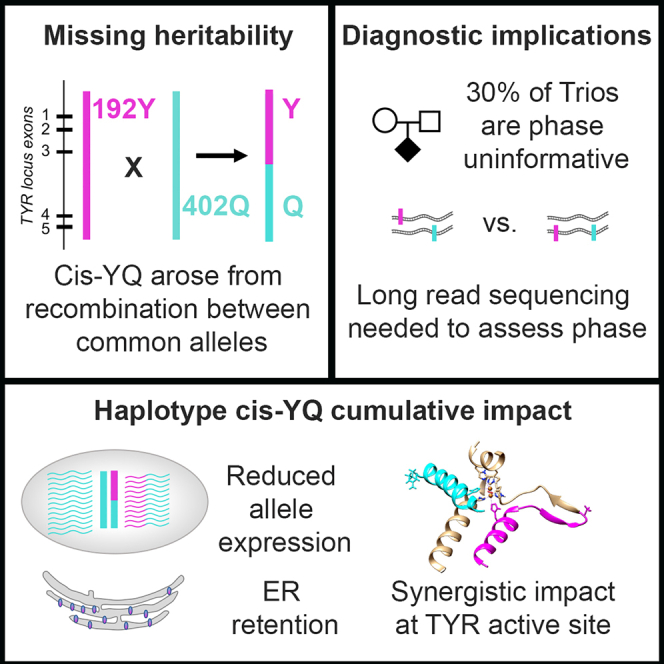

Oculocutaneous albinism (OCA) is a rare disorder of pigment production. Affected individuals have variably decreased global pigmentation and visual-developmental changes that lead to low vision. OCA is notable for significant missing heritability, particularly among individuals with residual pigmentation. Tyrosinase (TYR) is the rate-limiting enzyme in melanin pigment biosynthesis and mutations that decrease enzyme function are one of the most common causes of OCA. We present the analysis of high-depth short-read TYR sequencing data for a cohort of 352 OCA probands, ∼50% of whom were previously sequenced without yielding a definitive diagnostic result. Our analysis identified 66 TYR single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small insertion/deletions (indels), 3 structural variants, and a rare haplotype comprised of two common frequency variants (p.Ser192Tyr and p.Arg402Gln) in cis-orientation, present in 149/352 OCA probands. We further describe a detailed analysis of the disease-causing haplotype, p.[Ser192Tyr; Arg402Gln] (“cis-YQ”). Haplotype analysis suggests that the cis-YQ allele arose by recombination and that multiple cis-YQ haplotypes are segregating in OCA-affected individuals and control populations. The cis-YQ allele is the most common disease-causing allele in our cohort, representing 19.1% (57/298) of TYR pathogenic alleles in individuals with type 1 (TYR-associated) OCA. Finally, among the 66 TYR variants, we found several additional alleles defined by a cis-oriented combination of minor, potentially hypomorph-producing alleles at common variant sites plus a second, rare pathogenic variant. Together, these results suggest that identification of phased variants for the full TYR locus are required for an exhaustive assessment for potentially disease-causing alleles.

Keywords: tyrosinase, oculocutaneous albinism, haplotype, pigmentation, missing genetic heritability, foveal hypoplasia, hypopigmentation, albinism

Graphical abstract

This work finds a rare allele p.[Ser192Tyr; Arg402Gln] accounting for the majority of missing heritability in oculocutaneous albinism type 1B. This cis-YQ allele comprises two common variants recombined onto a single haplotype and highlights the need for haplotype-based disease allele queries to complement single-allele, frequency-based variant detection pipelines.

Introduction

Non-syndromic oculocutaneous albinism (OCA) is a recessive disorder in which individuals exhibit absent or reduced skin, hair, and eye pigmentation along with eye developmental anomalies. Foveal hypoplasia and optic nerve misrouting result in decreased visual acuity and stereoscopic vision.1 Extensive phenotypic variation is observed among individuals with albinism. OCA is genetically heterogeneous, with associated, bi-allelic variants detected in seven distinct genes: TYR (OCA type 1A [MIM: 203100] and 1B [MIM: 606952]), OCA2 (OCA type 2 [MIM: 203200]), TYRP1 (OCA type 3 [MIM: 203290]), SLC24A5 (OCA type 4 [MIM: 606574]), SLC45A2 (OCA type 6 [MIM: 113750]), LRMDA (OCA type 7 [MIM: 615179]), and DCT (OCA type 8 [MIM: 619165]).2,3 In addition, in a single report, OCA type 5 (MIM: 615312) is provisionally linked to a region of 4q24 in a single consanguineous Pakistani family but the specific gene has not been identified.4

Tyrosinase (TYR) is a copper-containing monophenol monooxygenase that catalyzes the conversion of tyrosine to DOPA and a subsequent conversion of DOPA to dopaquinone. It is the rate-limiting enzyme of a melanogenic pathway responsible for the production of black eumelanin and reddish pheomelanin pigments within intracellular vesicles (melanosomes). Melanin is produced in melanocytes (found in skin) and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and choroid tissues in the eye.5 The phenotypic variability in peripheral pigmentation in TYR/OCA type 1 is traditionally separated into pigmenting (OCA type 1B) and non-pigmenting (OCA type 1A) forms,6 with bi-allelic rare variants that impact TYR function accounting for roughly 50% of all instances of non-syndromic OCA worldwide. A considerable number of OCA-affected individuals exhibit missing genetic heritability, either with only a single pathogenic allele identified at the TYR locus or no variants in any OCA gene screened.7,8,9

Two common single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) at the TYR locus, rs1042602 (g.88911696C>A [GenBank: NC_000011.9] [c.575C>A (p.Ser192Tyr) (GenBank: NM_000372.5)]) and rs1126809 (g.89017961G>A [GenBank: NC_000011.9] [c.1205G>A (p.Arg402Gln)]), exhibit global minor-allele frequencies of 35% and 26%, respectively. These alleles define distinct haplotype clades found among individuals of European and northern African descent with age estimates of 15,600–6,100 years before present (BP) for rs1042602 (p.Ser192Tyr) and 29,000–20,000 years BP for rs1126809 (p.Arg402Gln).10 Admixture mapping has found rs1042602 (p.Ser192Tyr) to be associated with pigmentation differences between European and African populations.11 Both TYR variants have been identified in multiple skin and eye phenotype-based genome-wide association studies (GWASs), suggesting that these variants play a role in common pigmentation variation worldwide. Specifically, rs1042602 (p.Ser192Tyr) has been associated with 18 different GWAS traits including common skin and hair pigmentation differences, freckling, macular thickness, cataracts, intraocular pressure, retinal nerve fiber layer thickness, and ganglion cell inner plexiform layer thickness (Table S1).12 Similarly, rs1126809 (p.Arg402Gln) has been associated with 13 GWAS traits involving normal skin and hair pigmentation, eye color, optic disc size, age-related hearing loss, and vitiligo as well as 21 additional GWAS traits associations for cutaneous melanocyte-related phenotypes including actinic keratosis, tanning, sunburns, nevus counts, and multiple skin cancers (Table S1).12 While the full effects of these missense variants on TYR function have not been fully elucidated, both p.Ser192Tyr and p.Arg402Gln have been independently associated with a reduction in levels of TYR enzymatic activity and reduction in TYR protein levels.13,14,15,16 Furthermore, p.Arg402Gln exhibits impaired glycosylation and abnormal retention of TYR in the endoplasmic reticulum at 37°C, which is rescued by a lower temperature, 31°C, providing supportive evidence that it is a temperature-sensitive allele.15,17

Both the rs1042602 (p.Ser192Tyr) and rs1126809 (p.Arg402Gln) variants are over-represented among individuals with OCA.7,9,18,19,20,21,22 The high minor-allele frequency of both variants has led to debate about their contribution to the OCA phenotype.8,23,24 However, neither p.Arg402Gln nor p.Ser192Tyr seem capable of causing albinism independently given the frequency of homozygous individuals for either allele (p.Ser192Tyr = 0.08 and p.Arg402Gln = 0.04).25

A rare haplotype p.[Ser192Tyr; Arg402Gln] in which p.Ser192Tyr and p.Arg402Gln minor alleles occur in cis has been estimated to occur with a frequency ranging from 0.01 to 0.019 among individuals of European descent.15,26,27 We refer to this allele as “cis-YQ”. The cis-YQ allele has been observed in trans orientation with likely pathogenic and pathogenic trans-oriented alleles in some persons with albinism,9,16,19,20,27,28 for example, associated with OCA type 1B in a large Amish pedigree.16 The presence of two cis-YQ alleles in persons with albinism has also been observed.21 Multiple hypotheses have been put forward to explain potential deleterious properties associated with the cis-YQ allele. These include the suggestion that rare intronic variants on the cis-YQ haplotype may impact splicing19,21; the possibility that additional elements in cis may affect gene expression21; and that the presence of p.Ser192Tyr and p.Arg402Gln on the same peptide may have a synergistic impact on gene function and protein stability.15

We present analyses exploring the open questions surrounding the cis-YQ haplotype, including potential effects that the haplotype may have on gene expression and transcript stability for the cis-YQ allele. Our haplotype-based approach allows for a detailed evaluation of potential proxy variants. Given the frequency of the common alleles p.Ser192Tyr and p.Arg402Gln, the over-representation of the cis-YQ haplotype allele, and the lack of comprehensive proxy variants for the cis-YQ allele, our analysis highlights the need to clinically incorporate phase-based haplotype screening of the TYR locus for individuals with OCA type 1, with the goal of being able to provide a complete and comprehensive diagnosis for all OCA type 1-affected individuals.

Material and methods

Human subjects

Individuals were drawn from a prior NIH Clinical Center natural history study (IRB approved study 2009-HG-0035) as well as a deidentified cohort assembled by Dr. Richard King and Dr. William Oetting at the University of Minnesota and consisting of DNA samples from individuals diagnosed with OCA under IRB-950M10178. This study conforms to the recognized standard in the US Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects. Among individuals in our combined cohort, ∼50% were previously screened for variants in TYR and OCA2 but remained without complete diagnosis prior to our screening. Thus, our allele frequencies for commonly observed OCA type 1 alleles may be skewed lower than what might be present among the total population of unscreened OCA type 1-affected individuals.

Sequencing and read alignment

A total of 352 probands were custom capture sequenced across genomic loci for 37 genes responsible for non-syndromic albinism, syndromic albinism, and genes found correlated with human pigmentation variation through GWASs, as previously described.29 Briefly, the custom platform (Twist Biosciences) was designed to query all introns, exons, and established regulatory regions for TYR, OCA2, SLC45A2, SLC24A5, TYRP1, and LRMDA. The remaining 31 genes reflected syndromic albinism loci and genes identified through GWASs for common pigmentation variation and were queried for exonic and regulatory sequences. In total, this analysis consisted of 58,080 unique bait probes 120 basepairs (bp) in length, spanning a total of 6,696,663 bp (TWIST Bioscience). Sequencing was performed with at least 7 million paired-end 151 bp reads obtained for each sample. Sequence reads were aligned to build GRCh37/hg19 pipeline as previously described.29

Variant functional interpretation

Initial annotation of all variants across the 352 individuals were annotated using the Annovar-based pipeline as previously described.29 All TYR variants were identified relative to GenBank:NM_000372.5 and were further assessed using Varsome, Alumut, and ClinGen databases. Using a consistent and systematic approach, we applied the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) criteria30 to define pathogenicity with the attribute defining clarifications found in File S1.

SNP genotyping and copy number variant (CNV) detection

Samples were genotyped using the InfiniumExome-24v1.1 BeadChip (Illumina, Inc.). DNA was processed according to Illumina’s Infinium assay protocol and raw data were collected by the iScan System (Illumina, Inc.) and processed using GenomeStudio v2.0 (Illumina, Inc.). CNVs were detected using cnvParition v3.2 (Illumina, Inc.) and Nexus v10.0 (BioDiscovery, Inc.). For detection with cnvPartition, the “minimum confidence value” was set at 15, the “minimum number of contiguous SNPs” was set at 4, and “GC wave adjust” was set at “TRUE”. Default parameters were used for all other criteria in both detection algorithms. CNVs were filtered implementing the following criteria to assign a call as “likely genuine” from cnvPartition: copy number = 0 and confidence value >150; copy number = 1 and confidence value >15; copy number = 3 and confidence value >35. Nexus Copy Number was used to visually evaluate CNVs and confirm genuine calls. CNVs were annotated with PennCNV v.1.0.4 using the “scan_region.pl” script included in the package. Coordinates are in accord with human genome build 19 (GRCh37/hg19).

All individuals also received manual evaluation of sequence mapped reads using Integrative Genomics Viewer. All structural variant junction sequences were confirmed by realignment of paired reads into de novo contigs utilizing Sequencher (Gene Codes) to verify sequence junctions.

Allelic phase

For variants located within the same TYR exon, phase was established directly from paired-end sequence read pairs. For variants located in distinct exons, the phase of variant alleles was established by allelic segregation of variants in family trios. TaqMan genotyping (Thermofisher) was performed for the SNVs rs61754388 (g.88961072C>A [GenBank: NC_000011.9], c.1118C>A [p.Thr373Lys] [GenBank: NM_000372.5]), rs28940876 (g.88911363C>T [GenBank: NC_000011.9], c242C>T p.Pro81Leu) [GenBank: NM_000372.5]), rs1042602 (p.Ser192Tyr), rs1126809 (p.Arg402Gln), and rs147546939. All other alleles were evaluated by amplification of TYR and OCA2 exons with primers sequences noted in Table S2 and direct sequencing of samples by Macrogen or Eurofins Genomics. Phased haplotype alleles from 1000 Genomes were queried using LDlink.31

Cell culture

Primary melanocyte control cell lines were a generous gift from Dr. Kevin Brown (NCI).32 Primary melanocytes were obtained under a natural history study (NHGRI IRB 09-HG-0035). Cell lines were maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2 as described by Halaban et al.33 Cell lines were grown in biological triplicate for all gene expression assays.

TYR mRNA expression and splice junction assessment

RNA was isolated with RNeasy mini kits (Qiagen) from three independent biological replicates for each cell line. Complementary DNA was generated with Super Script III kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative PCR for total TYR expression was performed using TaqMan assay Hs00165976_m1 (Thermofisher) in triplicate using a relative standard curve as per instructions using a StepOne System (Thermofisher) with each biological replicate being the average of three technical replicates.

TaqMan SNP Genotyping assay rs1042602 (Thermofisher) was used for quantitative allelic expression of cis-YQ alleles in OCA-affected individuals. The standard curve was generated by artificial mix of genomic DNA from rs1042602 “CC” and “AA” genotyped individuals.34 Quantification of splice junctions was performed with a minimal junction requirement set at >1% of TYR transcript junctions relative to the TYR exon 1-2 junction value for that individual.

TYR protein structure modeling

Two models of TYR were used to predict the consequences of alteration on TYR structure. The first model (AlphaFold model, AF-P14679-F1-model_v4) is a full-length TYR from UniProt website (https://www.uniprot.org/). Notably, this model does not include the coordinated copper ions present in the mature TYR enzyme. The second model is an intra-melanosomal (IMD) domain of TYR from the ocular proteome website located at NEI Commons (https://neicommons.nei.nih.gov/). The IMD model does incorporate TYR copper ions. Each model was mutated in three patterns: addition of p.Ser192Tyr, addition of p.Arg402Gln, and addition of both p.Ser192Tyr and p.Arg402Gln. Both models for TYR were refined using optimized forcefield energy including solvation and minimized using steepest descent minimization and simulating annealing. In the last step, each model was equilibrated using 10 ns molecular dynamics. All calculations were performed using the molecular graphics, -modeling, and -simulation program Yasara (http://www.yasara.org/). Measurements of changes in active sites measured by the distance tool provided in UCSF Chimera.35 For the mutant variants, deviations of Cϒ positions in the active site histidines were calculated using the corresponding 10 ns IMD and AlphaFold models. First, AlphaFold models were superimposed over IMD models to put the atomic coordinates on the same scale. For both, IMD and AlphaFold models, the deviations of Cϒ positions were calculated as a difference between the positions of histidines in each mutant variant and the corresponding positions of the wild-type protein.

Results

Multiple TYR variants were observed in a cohort of individuals with OCA

From an initial pool of 352 OCA-diagnosed individuals, we used a custom capture sequencing (CCS) approach to identify 149 TYR/OCA type 1 probands who possess TYR variants predicted to impact TYR function (Tables S3 and S4). In total, we identified 70 distinct TYR variants. These included three large structural variant (SV) alleles, 66 rare missense and predicted splice altering variants, and one rare haplotype defined by the cis-YQ haplotype allele (Table S4). Application of ACMG criteria defined 79% of the identified TYR variants as “clearly pathogenic” or “likely pathogenic” and 21% of the variants as of “uncertain significance” (File S1, Table S4). Nine of the 15 variants of “uncertain significance” have been previously reported to be associated with OCA in the literature.

Variant alleles were distributed across the TYR locus. Among the SNVs and insertion/deletion (indel) variants, a total of 21/66 TYR/OCA type 1 variants were predicted to be null alleles. Of the 11 variants located within the defined functional protein regions of TYR (File S1), 10 were missense variants and 1 was a null variant. The most frequently observed TYR SNVs within this cohort were c.1118C>A (p.Thr373Lys) (n = 29, allele frequency [AF] = 10.4%), g.88960984T>A (GenBank: NC_000011.9), (c.1037−7T>A [GenBank: NM_000372.5]), (n = 19, AF = 6.8%), c.242C>T (GenBank: NM_000372.5) (p.Pro81Leu) (n = 15, AF = 5.4%), g.88924373G>T (GenBank: NC_000011.9), (c.823G>T [GenBank: NM_000372.5]; p.Val275Phe) (n = 10, AF = 3.6%), g.89017973C>T (GenBank: NC_000011.9), (c.1217C>T [GenBank: NM_000372.5], p.Pro406Leu) (n = 9, AF = 3.2%), and g.88961101G>A (GenBank: NC_000011.9) (c.1147G>A [GenBank: NM_000372.5], p.Asp383Asn) (n = 8, AF = 2.9%). The increased frequency of these six variants among individuals with albinism has been well established.13,21

Genetic contribution from multiple OCA genes

Single TYR variants were also identified among individuals with two pathologic variants in other non-syndromic and syndromic albinism genes. Specifically, 9 individuals carried a single, rare TYR allele in addition to 2 predicted deleterious alleles in either OCA2, SLC45A2, or HPS1. These rare TYR alleles were deemed likely pathogenic or pathogenic for 8 of these 9 probands, while the remaining proband carried a variant of unknown significance (g.89028453G>C [p.Lys503Asn] [GenBank: NC_000011.9]). Identifying deleterious variants in multiple OCA genes has been previously reported.8,18 Within this cohort, while the deleterious alleles support the probands receiving an OCA type 2, OCA type 4, or HPS1 diagnosis, respectively, the additional identified TYR variants have the potential to further modulate each individual’s phenotype.

Common TYR variants p.Ser192Tyr and p.Arg402Gln are enriched in OCA-affected individuals

The TYR missense variants p.Ser192Tyr and p.Arg402Gln have variant allele frequencies ranging from 12% to 38% for rs1042602 (p.Ser192Tyr) and 8%–28% for rs1126809 (p.Arg402Gln) in 1000 Genomes and Allele Frequency Aggregator (ALFA) databases36 (Table 1). These wide frequency ranges reflect considerable variation depending on the populations included, with higher frequencies observed among individuals of European descent. Among the 149 OCA-affected individuals in our cohort with a single identified missense or altered splicing variant in TYR, self-reported ancestry is predominately of European descent and the alternate allele frequencies of rs1042602 and rs1126809 were 0.5 and 0.36, respectively. These frequencies are increased ∼1.3-/1.4-fold relative to the expected frequency among the ALFA European/ALFA global populations, respectively, for both rs1042602 and rs1126809 and ∼4-fold over 1000 Genomes global frequencies (Table 1).

Table 1.

cis-YQ SNV alternate allele frequencies

| rsID | Location | Alleles | ALFA Global | ALFA European | 1K Genomes Global | 352 albinism proband dataset | 149 TYR proband dataset |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs4547091 | promoter | C>T | 0.4376 | 0.4036 | 0.4896 | 0.3892 | 0.2885 |

| rs1042602 | p.Ser192Tyr | C>A | 0.3519 | 0.3816 | 0.1234 | 0.396 | 0.5 |

| rs4601783 | intron 3 | A>G | 0.4705 | 0.4979 | 0.5503 | 0.4474 | 0.3959 |

| rs11018555 | intron 3 | T>G | 0.4738 | 0.4079 | 0.5226 | 0.446 | 0.3758 |

| rs529135220 | intron 3 | G>C | 0.002 | 0.002 | _ | 0.0172 | 0.0409 |

| rs1393350 | intron 3 | G>A | 0.2394 | 0.2608 | 0.0793 | 0.1761 | 0.1644 |

| rs147546939 | intron 3 | A>G | 0.0149 | 0.9825 | 0.0048 | 0.0938 | 0.208 |

| rs1126809 | p.Arg402Gln | G>A | 0.2593 | 0.2763 | 0.0813 | 0.2642 | 0.3691 |

Enrichment of the rare cis-YQ allele among individuals with OCA

Among the 352 OCA probands in our cohort, we identified 46 individuals (13%) that are obligated by genotype to have the cis-YQ allele. These represented 42 individuals who were heterozygous for the cis-YQ allele and 4 who were homozygous. We were able to further establish allelic phase for the cis-YQ allele in trans to a second pathogenic TYR allele in 7/31 probands who were heterozygous for both rs1042602 (p.Ser192Tyr) and rs1126809 (p.Arg402Gln). In total, the identified 57 cis-YQ alleles contributed to definitive diagnosis for 45% of all TYR/OCA type 1 probands, with the cis-YQ allele accounting for 19% of all variant alleles identified in TYR/OCA type 1-affected individuals. This frequency is 2-fold higher than the next most frequently observed TYR pathogenic allele identified in this cohort (p.Thr373Lys) and 25-fold increase over the cis-YQ allele frequency in 1000 Genomes. Furthermore, for all TYR/OCA type 1-affected individuals carrying a cis-YQ allele, each presented with only one additional TYR variant, not two, consistent with the cis-YQ being a second, independent, pathogenic allele. Finally, the four probands homozygous for rs1042602 (p.Ser192Tyr) and rs1126809 (p.Arg402Gln) (i.e., possessing two cis-YQ alleles) were negative for any other deleterious variant among the 37 genes queried by CCS. Taken in total, the over-representation of a rare cis-YQ haplotype allele along with its presence in individuals with only a single additional TYR pathogenic allele, and no other deleterious allele being identified in individuals who possess two cis-YQ alleles, is consistent with the cis-YQ haplotype allele contributing to an OCA phenotype.

cis-YQ allele contributes to an OCA type 1B phenotype

Among the cis-YQ allele-possessing individuals, phenotype descriptions are all consistent with the cis-YQ allele contributing to a pigmenting OCA type 1B phenotype. This OCA type 1B phenotype was present for both individuals who were homozygous for the cis-YQ allele and those who possessed a cis-YQ allele in trans to a predicted null allele. Within our cohort, this latter class included a proband who was hemizygous for the cis-YQ allele in trans-orientation to an extensive deletion of the entire TYR coding region, in addition to four other individuals who possess a single cis-YQ allele in trans to the predicted null variant GenBank: NC_000011.9:g.88911122A>G (c.1A>G) (start loss). In each instance, individuals presented with varying degrees of hair and skin hypopigmentation, indicating the OCA type 1B phenotype. These results demonstrate that the cis-YQ allele can contribute to the pathogenicity of OCA.

TYR cis-YQ allele arose by recombination in intron 3

Given the high frequency of independent rs1042602 (p.Ser192Tyr) and rs1126809 (p.Arg402Gln) variant alleles in the general population, it is challenging to definitively establish segregation of a rare cis-YQ haplotype allele in OCA probands and provide a molecular diagnosis to all families. Thus, we investigated the broader consensus cis-YQ haplotype to identify how the allele arose and assess whether any rare variants could be used as a proxy marker to distinguish the rare-cis YQ allele and assist in haplotype phase assessment. Genotypes for the four homozygous cis-YQ individuals and an additional single hemizygous individual were used to establish a consensus haplotype for the cis-YQ allele spanning g.88787290_89055293 (GenBank: NC_000011.9) (Table S5). Across the entirety of the TYR locus, distinct haplotypes were observed among individuals homozygous for either p.Ser192Tyr or p.Arg402Gln variant alleles (and were homozygous reference at the other variant). Comparison of these two ancestral haplotypes to those of cis-YQ homozygous individuals and obligate carriers of the cis-YQ allele suggests that recombination event(s) occurred within intron 3 between the two ancestral alleles to generate the rare cis-YQ allele (Figure 1, Table S5).

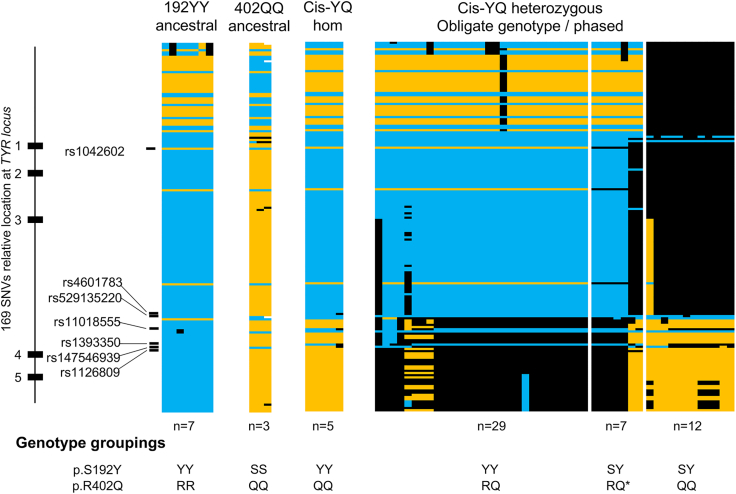

Figure 1.

cis-YQ haplotype arose by recombination

Genotypes at 169 SNVs across the TYR locus for OCA type 1-affected individuals who possess the cis-YQ allele and individuals homozygous for either ancestral allele. Probands are grouped by genotypes (left to right): homozygous for p.Ser192Tyr (192YY) ancestral haplotype (YY; RR), n = 7; homozygous for p.Arg402Gln (402QQ) ancestral haplotypes (SS; QQ), n = 3; homozygous and hemizygous for the cis-YQ haplotype, n = 5; p.Ser192Tyr genotype-obligates for the haplotype (YY; RQ), n = 29; phase-established cis-YQ haplotype individuals (noted by SY; RQ∗), n = 7; and p.Arg402Gln genotype-obligates for the haplotype (SY; QQ), n = 12. Genotypes are color coded as follows: blue, homozygous reference alleles; yellow, homozygous alternate alleles; black, heterozygous genotypes; and white, no genotype call for that SNV. Critical SNVs for distinguishing the haplotype are listed on the left. Full genotype information for this graphical representation is present in Table S5.

Multiple, distinct cis-YQ haplotypes are present

Interestingly, close review of the cis-YQ consensus haplotype revealed that rs4601783, rs11018555, rs1393350, and rs147546939 (within intron 3) were heterozygous in one of the four homozygous cis-YQ individuals (Figure 1, Table S5). The remaining variants across the TYR locus were identical among one hemizygous and three homozygous cis-YQ individuals. This variation suggests that multiple de novo recombination/mutation events have occurred within intron 3 to create the two cis-YQ alleles observed.

To assess the frequency of these two cis-YQ OCA allele haplotypes, we next queried the 1000 Genomes Project variant data for all cis-YQ haplotypes at the TYR locus, including haplotype phase information.31 A total of 16/5,016 haplotype alleles contained both p.Ser192Tyr and p.Arg402Gln in cis. These 16 cis-YQ alleles could be further subdivided into four distinct haplotypes, utilizing a total of seven variants within a 32 kb region of intron 3 that are associated with cis-YQ haplotypes (Table 2). These four haplotypes identified in 1000 Genomes were distinct from the two cis-YQ haplotypes identified in our OCA type 1 individual cohort, reflecting additional intron 3 variation. The genetic variability that is observed in this region, both in 1000 Genomes haplotypes and across individuals homozygous for p.Ser192Tyr and p.Arg402Gln, precludes identification of a single breakpoint across this region in the general population. Taken together, these data are consistent with either multiple recombination events or a single, much older recombination event, followed by the additional accruing of DNA variation, giving rise to a small number of distinct haplotypes associated with rs1042602 (p.Ser192Tyr) and rs1126809 (p.Arg402Gln) together on the same allele.

Table 2.

1000 Genomes frequencies for cis-YQ critical SNVs

| ID | rs1042602 | rs4601783 | rs4121401 | rs10741305 | rs11018555 | rs1393350 | rs147546939 | rs1126809 | Allele count OCA | Allele count 1K Genomes | Frequency 1K Genomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1K Genomes allele freq. (reference, alternate) | C = 0.877, A = 0.123 | A = 0.450, G = 0.550 | T = 0.548, C = 0.452 | T = 0.368, C = 0.632 | T = 0.477, G = 0.523 | G = 0.921, A = 0.079 | A = 0.995, G = 0.005 | G = 0.919, A = 0.081 | |||

| 1K Genome cis-YQ haplotypes | |||||||||||

| 1K allele 1 | A | A | C | C | T | G | G | A | – | 11 | 0.0022 |

| 1K allele 2 | A | A | C | C | G | A | A | A | – | 3 | 0.0006 |

| 1K allele 3 | A | A | C | C | T | A | A | A | – | 1 | 0.0002 |

| 1K allele 4 | A | A | T | T | T | G | A | A | – | 1 | 0.0002 |

| OCA cohort cis-YQ homozygote derived haplotypes | |||||||||||

| cis-YQ allele 1 | A | A | C | T | G | G | G | A | 8 | 0 | – |

| cis-YQ allele 2 | G | C | T | T | A | A | A | 1 | 0 | – | |

| 1K Genomes additional rs147546939 haplotypes | |||||||||||

| rs147546939 with rs1126809 | C | G | C | C | G | A | G | A | – | 12 | 0.0024 |

| rs147546939 alone | C | G | C | C | G | G | G | G | – | 1 | 0.00002 |

rs147546939 is present in most but not all cis-YQ alleles, and is not unique to cis-YQ alleles

The rare variant rs147546939, located in intron 3, has been proposed as a useful rare proxy variant for cis-YQ allele identification.19 Within our cohort, rs147546939 is 14-fold more frequent than expected based on ALFA global frequencies. However, it is not present on all cis-YQ alleles. For the homozygous/hemizygous individuals in our cohort, the rs147546939 alternate allele “G” is present on 8/9 alleles (Tables 2 and S4). Among the remaining cis-YQ obligate genotype and phase-established individuals, 39/48 (81.2%) possess the rs147546939 allele. Furthermore, rs147546939 was not exclusively observed among obligate cis-YQ grouped individuals in our cohort. Examination of 1000 Genomes supports these observations: the rs147546939 allele was present with both rs1042602 (p.Ser192Tyr) and rs1126809 (p.Arg402Gln) in a subset (11/16) of the cis-YQ haplotypes in 1000 Genomes, and rs147546939 was present in 31/5,016 alleles, thus occurring on 20 other non cis-YQ haplotypes. These additional rs147546939 alleles could be further subdivided into those with only p.Arg402Gln (12/5,016 haplotype alleles) and an allele with neither p.Ser192Tyr or p.Arg402Gln (1/5,016 haplotype alleles) (Tables 2 and S6). Thus, while highly enriched in cis-YQ alleles, rs147546939 is not a unique or 100% concordant proxy marker for the cis-YQ haplotype.

Rare variant rs529135220 resides on subset of cis-YQ alleles

Intermittent presence of the rare allele, rs529135220, was also associated with a subset of cis-YQ haplotypes. Although this allele was not found in 1000 Genomes, we found rs529135220 in 11 obligate cis-YQ and 1 phase established cis-YQ probands in our cohort, all of whom possess an rs147546939 variant containing cis-YQ allele (Table S6). This, in addition to the allele frequency of rs529135220 equal to 0.001 in the general population, suggests that rs529135220 is a rare variant located on a small subset of rs147546939 variant cis-YQ alleles and could be used to assist in phasing for a subset of potential cis-allele possessing individuals.

Primary melanocyte TYR mRNA expression and splicing do not differ between reference allele and obligate cis-YQ haplotype individuals

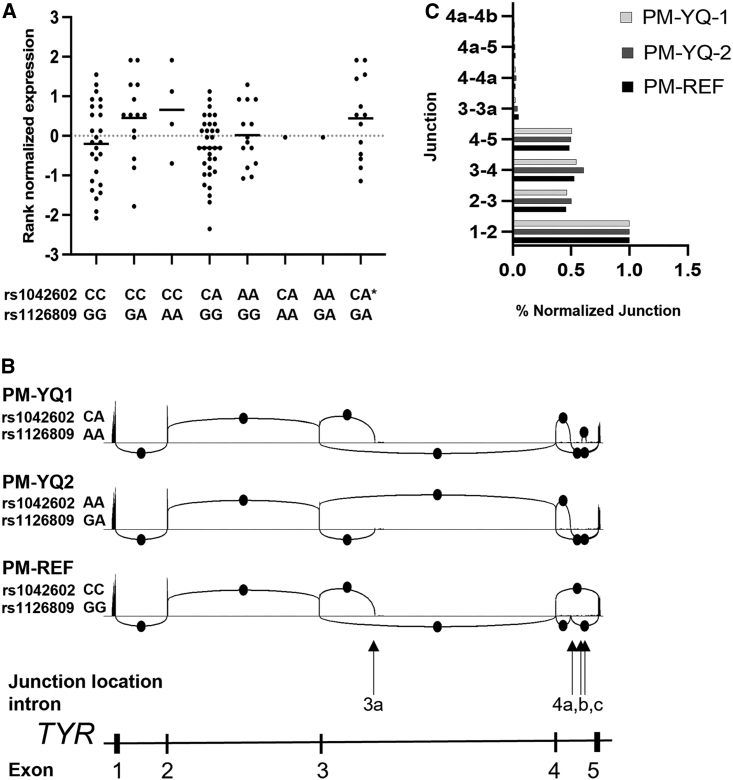

To determine if gene expression levels or alternative splicing isoforms could contribute to the pathogenicity of the cis-YQ allele, we interrogated how TYR expression may vary with respect to associated genotypes and haplotypes. For this we queried a high read depth, RNA-seq dataset from a control dataset consisting of 106 primary melanocyte cell lines.32 In this RNA-seq dataset, we identified two individuals who were obligate carriers for the cis-YQ allele. Evaluation of the overall expression of TYR mRNA for these two individuals, in contrast to the other genotype groupings, revealed no difference in total TYR expression between the obligate cis-YQ carriers and all other haplotype groupings (Figure 2A). In addition, as this is a high-depth RNA-seq dataset, we also queried whether any significant alternative splice junctions could be observed for the same two obligate cis-YQ carriers and found no evidence for alternative junctions reflecting any significant alternate splicing events for the two obligate cis-YQ individuals (Figures 2B and 2C).

Figure 2.

Total TYR expression levels and splicing profiles for cis-YQ alleles

Rank normalized total TYR mRNA expression for individual cell lines from the primary melanocyte (PM) high-depth RNA-seq dataset.32

(A) PMs grouped based on genotypes for rs1042602 (p.Ser192Tyr) and rs1126809 (p.Arg402Gln) haplotype combinations, including two genotype-obligate cis-YQ cell lines with genotypes for rs1042602 and rs1126809 as CA/AA (PM-YQ-1) and AA/GA (PM-YQ-2), respectively. Unphased compound heterozygotes are noted by an asterisk (∗).

(B) Sashimi plots indicate location of RNA-splice junctions for cis-YQ containing PM cell lines PM YQ-1 and PM YQ-2 in comparison to control primary melanocytes PM-REF. Splice junction events are denoted by the circles. Non-RefSeq junction locations are labeled 3a, 4a, 4b, and 4c based on intron location and were detected at levels between 1% and 2% of junctions as compared to the most frequent junction between exons 1 and 2.

(C) Relative junction frequency plots for cis-YQ haplotype possessing primary melanocytes (PM YQ-1 and PM YQ-2) in comparison to control primary melanocyte (PM-REF). The number of reads spanning splice junctions are presented as % normalized junctions to exons 1-2 junction.

Primary melanocyte eQTL analysis identifies increased expression for p.Arg402Gln haplotype mRNA

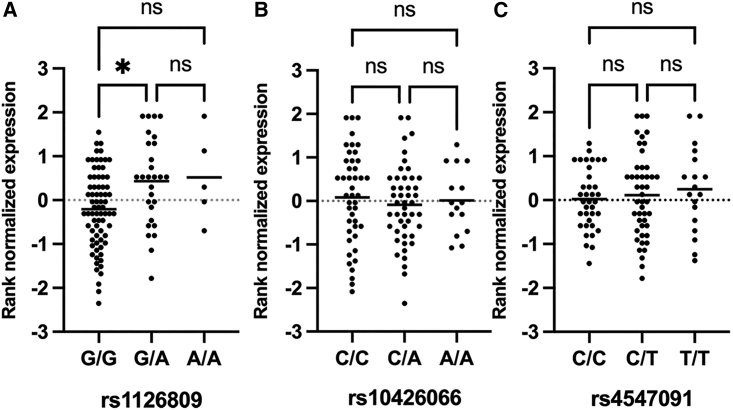

This primary melanocyte-specific eQTL dataset was next queried to assess whether there were differences in mRNA expression correlated with the ancestral haplotypes for p.Ser192Tyr and p.Arg402Gln alleles. Allele rs1126809G>A (p.Arg402Gln) was found to be a TYR eQTL,32 as individuals with either GA or AA genotypes had slightly higher expression of total TYR mRNA in comparison to reference allele GG individuals (Figure 3A). However, no difference in total TYR expression correlated with variant rs1042602 (p.Ser192Tyr) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Total TYR expression levels in primary melanocytes evaluated by genotype

Rank normalized total TYR mRNA from primary melanocyte high-depth RNA-seq plotted for (A) p.Arg402Gln genotypes, (B) p.Ser192Tyr genotypes, and (C) c.−301C>T rs1042602 genotypes.

Promoter variant c.−301C>T is not correlated with altered TYR expression

Previously, Michaud et al. had identified the common “C” allele for the TYR promoter variant, g.88910821C (GenBank: NC_000011.9G) (c.−301C>T) (rs4447091), to be present on cis-YQ alleles in their OCA individual cohort. This occurrence is notable as the rs4447091 common “C” allele variant resides within and disrupts a consensus binding sequence for OTX2, a transcription factor important in retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) specification.37,38 In fetal RPE cells, the reference “C” allele is associated with significantly lower TYR allele expression.39 Analysis of our cohort also found 100% concordance of the reference “C” allele with our 57 cis-YQ haplotype alleles. However, analysis of total TYR levels in the primary melanocyte RNA-seq dataset found no statistical difference in total TYR mRNA expression among cells with the three possible rs4447091 genotypes (Figure 3C).

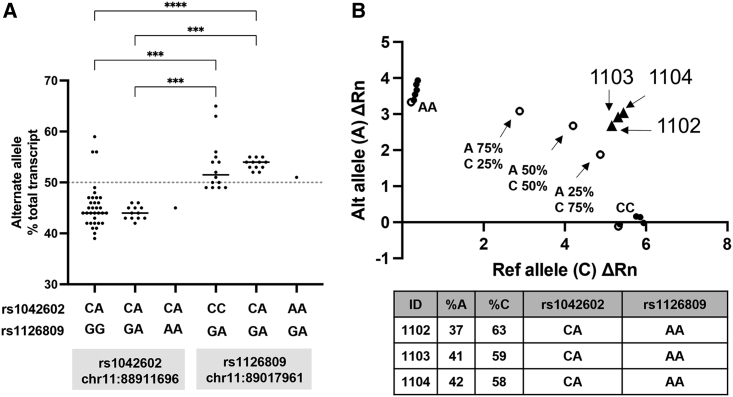

Allelic quantitation of cis-YQ alleles

To better control for intercellular differences which may impact gene expression, we tallied cSNP specific read counts for each allele of p.Ser192Tyr and p.Arg402Gln in RNA-seq data from primary melanocytes heterozygous for the cSNP being queried. Examination of rs1042602 (p.Ser192Tyr) containing alleles finds ∼45% of TYR mRNA expression comes from alleles carrying the variant allele “A,” in contrast to ∼55% from the reference allele “C” (Figure 4A, left side). Notably the single individual with an obligate cis-YQ allele, and heterozygous for the p.Ser192Tyr genotype, demonstrated a similar trend of slightly lower expression derived from the p.Ser192Tyr allele. In contrast, rs1126809 (p.Arg402Gln) informative cell lines found the variant allele p.Arg402Gln “A” had median transcript levels accounting for ∼53% of total transcripts (Figure 4A, right side). Overall, p.Ser192Tyr variant “A” alleles were detected at slightly lower level while alleles containing the p.Arg402Gln variant “A” allele were detected at slightly higher level.

Figure 4.

Comparison of allelic expression across TYR haplotypes

Relative allelic expression values for p.Ser192Tyr and p.Arg402Gln ancestral alleles and cis-YQ alleles from primary melanocytes by (A) high-depth RNA-seq and (B) rs1042602 TaqMan assays.

(A) Alternative allele percentages across haplotype combinations for cell line heterozygous for rs1042602 (p.Ser192Tyr) (left) and rs1126809 (p.Arg402Gln) (right) as a percentage of total mRNA transcript. Non-parametric Krudkal-Wallis one-way analysis of variants, followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test was performed with ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001 and ∗∗∗∗p ≤ 0.0001 as indicated. Expression of TYR from two cis-YQ alleles is reflected in the obligate cis-YQ genotype groupings.

(B) Relative TYR expression levels of cis-YQ alleles from three OCA-1B-affected, p.Ser192Tyr-informative individuals. Open dots represent a standard curve made using dilutions of homozygous control DNA. Solid dots are homozygous AA and CC individuals, and triangles depict average allelic expression for the three OCA-1-affected individuals from a single family.

Interestingly, evaluation of allelic expression in three p.Ser192Tyr informative, cis-YQ obligate OCA individual primary melanocyte cell lines (derived from a proband and their two OCA-affected sibs) supported the modest reduction in expression associated with the rs1042602 (p.Ser192Tyr) variant allele in the primary melanocyte cell lines (Figure 4B). In these cis-YQ cell lines, the p.Ser192Tyr cis-YQ allele transcript levels were slightly reduced in the range of 37%–42% compared to that of the second p.Arg402Gln allele present in trans (Figure 4B). These results, together with the levels of total TYR message, highlight that cis-YQ allele mRNA levels in epidermal melanocytes trend lower but do not produce vast differences in levels of expression as compared to ancestral p.Ser192Tyr and p.Arg402Gln alleles.

Predicted impact of cis-YQ protein on TYR active site

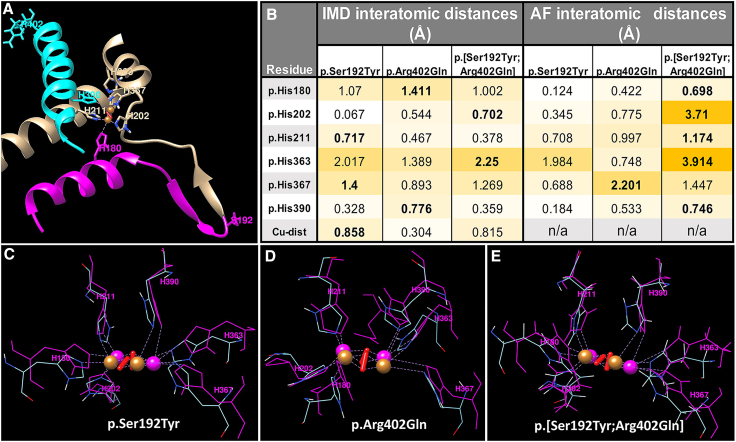

We assessed the extent to which the two variants, p.Ser192Tyr and p. Arg402Gln, located on widely separated locations on the final TYR enzyme, might impact TYR protein structure and the coordination of copper ions by critical histidines at the TYR active site (Figure 5A). We first performed molecular dynamics simulations using AlphaFold utilizing AF-P14679-F1-model_v4 obtained from UniProt which structurally models the full-length TYR by AlphaFold.40 We simulated AlphaFold structures for molecules with each of the two variants alone and in combination, in comparison to the TYR reference predicted structure. The AlphaFold model predicted a roughly additive effect for the two-variant model, with respect to predicted movement of copper-coordinating histidine positions (Figure 5B, right panel). However, this model does not contain the copper ions present in active TYR, preventing prediction of the final consequences for their position. In addition, prior work in our group suggests that the absence of copper ions causes a reduction in stability of the AlphaFold model.41 We next utilized a second TYR model that included copper ions and two oxygen atoms. This published model is based on a modification of an existing TYRP1 crystal structure. Superposition of the two models illustrates their high degree of similarity (Figure S1). Using both models, we performed a 10 ns molecular dynamics simulation with the same three modifications. Changes in interatomic distances across multiple critical histidines are predicted, with the strongest impact predicted to occur at p.His363 in both models for the p.[Ser192Tyr; Arg402Gln] double variant (Figure 5B). The AlphaFold structure predictions are consistent with a hypothesis of additive effect of two component cis-YQ mutations on the positions of critical copper-coordinating histidine residues. The intermelanosomal domain (IMD) model showed a smaller absolute changes in histidine positions, but supported an overall effect on copper positions (Figures 5B–5E).

Figure 5.

The destabilizing effect of genetic perturbations is demonstrated by molecular dynamics

Results of 10 ns molecular dynamics applied to the homology model of the TYR intra-melanosomal domain (IMD) and AlphaFold model.

(A) A fragment of the IMD model showing a partial fragment structure of a four-helix bundle maintaining a TYR active site. The α-helix (residues 383–402), which includes alteration p.Arg402Gln and p.His390 coordinating copper atom, is shown in cyan. The changes caused by the alteration p.Ser192Tyr in p.His180 may be transferred through the β-sheet strand (residues 186–191) and the α-helix formed by residues 172–185.

(B) Deviations of Cϒ positions in histidine residues from the active site for the mutant variants are presented. Results of 10 ns molecular dynamics simulations are represented by the analysis of interatomic interactions calculated for Cϒ positions of histidines from an active site for IMD and AlphaFold models. Color scale range represents absolute value of the indicated changes on a scale from 0 (white) to 4 (goldenrod), with the largest histidine change in each model indicated in bold. The changes in positions of Cu atoms are characterized by Cu-dist.

(C–E) Active site configurations at 10 ns simulations for (C) p.Ser192Tyr, (D) p.Arg402Gln, and (E) p.[Ser192Tyr; Arg402Gln] mutant variants, respectively. Coordinating copper histidine residues are shown by magenta and blue for the wild-type protein and mutant variants, respectively.

Multiple OCA1 alleles are found in cis with either p.Ser192Tyr or p.Arg402Gln common haplotypes

Given the frequency of the ancestral haplotypes that individually possess p.Ser192Tyr and p.Arg402Gln in the general population, we investigated whether any of the 66 rare SNV and indel TYR variants identified in this cohort were found in cis with either of these two, common frequency, missense variants. We identified 4/5 individuals with c.1A>G allele to have this allele present in cis to the p.Arg402Gln variant. In addition, we identified 4 rare missense alleles which were present in cis orientation with p.Ser192Tyr and 1 rare missense variant in cis orientation with p.Arg402Gln in OCA probands. These common allele/rare variant haplotypes were identified in 15 individuals for p.[Ser192Tyr; Thr373Lys], 5 individuals for p.[Ser192Tyr; Asp383Asn], 7 individuals for p.[Pro81Leu; Ser192Tyr], 4 individuals for p.[Ser192Tyr; Pro406Leu], and 3 individuals for p.[Arg217Gln; Arg402Gln] (Table 2). However, for three of these alleles (p.Pro81Leu, p.Pro406Leu, and p.Arg217Gln), a subset of OCA individuals (2, 5, and 2 individuals, respectively) possess these missense variants in cis with the reference allele, not the variant allele at p.Ser192Tyr and p.Arg402Gln, suggesting that there are two distinct haplotypes for these three rare variants, with and without p.Ser192Tyr and p.Arg402Gln.

Taken together, we find evidence that there are rare pathogenic TYR variants present on ancestral haplotypes in which p.Ser192Tyr or p.Arg402Gln reside; and thus, there are multiple OCA-causing alleles that result in the production of a TYR protein with multiple amino acid substitutions that impact TYR function on the same peptide. These results highlight that establishing phase for the common alleles p.Ser192Tyr and p.Arg402Gln has implications not only for identification of cis-YQ alleles, but also for the identification and phasing of TYR haplotypes that are characterized by both rare and common missense variants.

Discussion

Striving to build a full catalog of all TYR variants for OCA

Current databases of TYR variants, e.g., ClinVar,42 do not provide complete descriptions of assessment criteria for the majority of entries. Of the more than 330 TYR variants currently reported, at least half have uncertain functional significance. A complete, documented application of the ACMG variant interpretation guidelines is a potential path toward improving reference datasets and responding to new evidence as it arises. In preparation for a future, structured assessment of all TYR variants using ClinGen methodology, we developed a TYR-specific adaptation of the standard ACMG guidelines. We did not discard any criteria, but added gene-specific parameters where available. Additions included defining known functional regions (PM1 criterion) and frequency thresholds (PM2 criterion). Our analysis found that, among the 70 TYR variants identified, 9 were not included in ClinVar. For the remaining 61 variants previously documented in ClinVar, 8 were listed as having conflicting interpretations or only a single submitter. Our analysis now defines these 17 variants, which collectively are either unrepresented or present in ClinVar with conflicting interpretations, as pathogenic (4 alleles) and likely pathogenic (13 alleles). We recommend further development of this process, including establishment of an expert panel, by the albinism community.

No definitive proxy variant marks the pathogenic cis-YQ haplotype

Among the OCA cohort presented in this paper, the cis-YQ allele is the most frequently observed OCA-type 1B allele in this cohort contributing to 45% of the bi-allelic OCA type 1B diagnoses. Unfortunately, the alleles p.Ser192Tyr and p.Arg402Gln are 106 kb apart and cannot be phased by short read sequencing alone. In addition, the high frequency of each individual allele in the general population complicates definitive diagnosis in individuals.

Our comprehensive high-depth sequencing of TYR in OCA probands, combined with the high frequency of alleles in the general population, allowed us to establish distinct haplotypes for the cis-YQ allele and each of the p.Ser192Tyr and p.Arg402Gln ancestral alleles, revealing that multiple recombination events likely underly the creation of cis-YQ alleles. No single rare variant acts as a perfect indicator of the presence of the cis-YQ alleles. Previously, rs147546939 was reported in 6 OCA-affected individuals who possessed a cis-YQ allele.19 While this rare variant was highly enriched among individuals with TYR/OCA type 1 alleles, we found that rs147546939 was not unique to the cis-YQ allele, either in our cohort or 1000 Genomes. Therefore, use of rs147546939 as a proxy marker for the cis-YQ allele could give rise to rare false positive and false negative cis-YQ diagnoses. We also note that the SNV rs529135220, while present on a subset of cis-YQ alleles in our cohort, was not seen on all cis-YQ alleles.

The frequency of the minor variants for p.Ser192Tyr and p.Arg402Gln yield a situation where even family segregation is not always sufficient to make an unambiguous diagnosis. 38% of family trios (5/13) in which the proband was heterozygous for both p.Ser192Tyr and p.Arg402Gln in our cohort remained uninformative for phase. These numbers highlight how definitive diagnosis for some OCA type 1-affected individuals will require new approaches, such as long read sequencing, to confirm the presence of the cis-YQ allele. Other disease-associated genes are likely to include disease-causing alleles comprising multiple variants—"haplotype alleles.” In the future, establishing comprehensive phased haplotypes will be critical for not only OCA diagnosis, but also complete assessment of genotype-phenotype correlations.

Haplotype-based functional analysis is needed to establish the functional impact of alleles

We investigated the cis-YQ haplotype to characterize potential deleterious factors (mRNA expression levels, splicing, and protein alteration) that might contribute to the overall haplotype insufficiency associated with the cis-YQ allele. Using primary cultured melanocytes, we found no evidence of splicing variation as a contributor to a reduction in TYR expression. However, our allelic expression analysis did note a small but consistent reduction in p.Ser192Tyr alleles expression. We also observed reduced cis-YQ transcript levels in primary melanocytes derived from 3 OCA-affected siblings that carried a p.[Tyr327Cys; Arg402Gln] allele in trans to the cis-YQ. Thus, the reduced cis-YQ expression we detected in these OCA-affected individuals may reflect reduced p.Ser192Tyr allele levels in combination with elevated p.[Tyr327Cys; Arg402Gln] allele levels as we consistently observed slightly elevated levels of p.Arg402Gln containing haplotypes in the control population. Importantly, these results demonstrate that mRNA expression of the cis-YQ allele, while consistently lower, is only modestly decreased compared to wild-type and p.Arg402Gln ancestral alleles. Furthermore, our high-depth sequence analysis across the entire TYR genomic locus found no evidence of additional genomic rearrangements or altered splicing within the cis-YQ haplotype that would dramatically reduce cis-YQ expression.

Impact of multiple TYR variants on protein structure and function

A body of prior published work supports a correlation between computational protein structure predictions and the presence of a subset of deleterious TYR alleles. This work has focused in part on changes to the TYR active site, including coordinated copper ions and coordinating histidine residues. In the wild-type holoenzyme, the two copper ions in the active site are each coordinated by three histidines, (CuA, by p.His180, p.His202, and p.His211 and CuB, by p.His363, p.His367, and p.His390) with the distance between the two copper atoms estimated to be 2.7–2.8 Å.41 We performed protein modeling in order to assess the impact of the individual variants alone and in combination on TYR structure. This analysis found that both p.Ser192Tyr and p.Arg402Gln have the capacity to alter histidine localization within the active site. These changes are smaller than those reported for direct coordinating-histidine mutations known to be associated with OCA type 1A. As such, our findings are consistent with a hypomorphic model for cis-YQ. Previously, p.Ser192Tyr had been documented to exhibit a ∼40% reduction in TYR activity.14,19 Our protein modeling highlights how this variant is predicted to impact both histidine and copper ion placement critical to TYR activity, as the alleles representing p.Ser192Tyr and p.[Ser192Tyr; Arg402Gln] are predicted to increase the distance between the Cu ions by 0.815–0.838 Å.

Considerable analysis has also been performed on the p.Arg402Gln allele. In addition to a reduction in DOPA-oxidase activity, p.Arg402Gln exhibits both a reduction in levels of TYR protein and retention in the ER in primary melanocytes grown at 37°C vs. 31°C.15,16 The combined effects of p.Ser192Tyr and p.Arg402Gln in cis were inadvertently assayed by Tripathi et al.43 The paper reported that a p.Arg402Gln TYR cDNA construct produced 25% of wild-type activity when transfected into HeLa cells. Subsequently, it was discovered that both the reported “p.402Gln” and wild-type control constructs included the p.Ser192Tyr variant.15,43 Furthermore, the impact of the two variants in cis has been evaluated by Lin et al. utilizing transfection of all relevant genotypes into HEK293 cells.16 This analysis revealed a diminished DOPA oxidase activity for the combined double allele construct under conditions tested at 31°C and 37°C. Taken together, these results highlight the complexity in evaluating the contribution to TYR function for these two common variants. Cumulatively, these alleles have been found to have an impact on TYR enzyme thermostability, protein localization, and enzymatic activity with the synergistic impact of the two alleles contributing to the OCA1B phenotype.

These results also highlight the importance of dissecting individual contributors to the consequences of haplotype-level alleles. Other examples in which a combination of common and rare SNVs in TYR may play a synergistic role with implications for OCA include p.[Ser192Tyr; p.Thr373Lys], p.[Pro81Leu; Ser192Tyr], and p.[Arg217Gln; Arg402Gln]. Detailed documentation of allele structure and phase will be needed for an accurate assessment of the presence and consequences of disease-causing alleles present in human populations.

Full disease haplotypes need to be evaluated across multiple disease-relevant tissues

Michaud et al. have suggested that the common “C” variant c.−301C>T (rs4547091) present on cis-YQ alleles may have a role in in modulating TYR expression. While rs4547091 was not identified as a statistically significant eQTL from primary melanocyte eQTL analysis, the overall trend in TYR primary melanocyte expression was for the CC genotypes to exhibit slightly lower total TYR expression in comparison to individuals with CT and TT genotypes. This is consistent with the direction observed for the variant in normal RPE cells, lower TYR expression in cells that have c.−301C>T (rs4547091) “C” allele. In our cohort, and in 1000 Genomes data, all genotypes point to the p.Ser192Tyr minor allele and the rs4547091 major allele in being in tight linkage disequilibrium, as the common rs4547091 “C” variant is present both on the cis-YQ and the p.Ser192Tyr ancestral haplotype, with the p.Ser192Tyr allele located 875 bp away from the proximal TYR promoter variant c.−301C>T (rs4547091). This association is notable given that both p.Ser192Tyr and rs4547091 have both been associated with retinal nerve fiber layer thickness and ganglion cell inner plexiform layer thickness.21,44 However, the c.−301C>T (rs4547091) “C” allele has a frequency of 0.5624 and is also present on alleles without p.Ser192Tyr, thus occurring on many different haplotypes. Further work will be needed to compare the functional impact of the full set of coding and non-coding variants located on the cis-YQ allele in both RPE cells and dermal melanocytes to better assess the potential cumulative contribution of each allele in modulating OCA phenotypes and possibly more broadly in ocular tissue morphology.

cis-YQ notation

We propose the term cis-YQ as a shorthand term of convenience to describe the TYR haplotype p.[Ser192Tyr; Arg402Gln]. We discourage the term “tri-allelic genotype” which has been utilized recently to describe the presence of a p.Arg402Gln allele in addition to two other TYR variant alleles. The term “tri-allelic genotype” may be confused with other distinct, yet similar terms such as “tri-allelic SNP” which is used to describe variants with multiple alleles at a single genomic position, and “tri-allelic inheritance” which, by definition, refers to an affected individual with three mutant alleles present within two genes. Ongoing research has found multiple examples in which individuals with albinism are heterozygous for variants in multiple albinism genes.8,19,27 These findings highlight the importance of separating the concept of a haplotype-based allele from digenic inheritance. Our identification of other pathogenic SNVs being present in cis with either p.Ser192Tyr or p.Arg402Gln alleles further highlights the need for accurate nomenclature.

We present the molecular characterization of variation in the TYR locus among individuals in a large OCA cohort. In particular, we present an in-depth analysis of the TYR cis-YQ haplotype. This analysis suggests that cis-YQ is a common cause of OCA type 1B and that sensitive and specific detection of cis-YQ is not uniformly possible with short-read sequencing even given trio segregation data. These findings also have implications beyond albinism and serve as a reminder that the presence of minor alleles at multiple common SNV loci can define rare, disease-causing haplotypes. These pathogenic, haplotype-defined alleles can contribute to missing genetic heritability. Identification of rare haplotypes may require a focus on haplotype frequency rather than variant frequency. For OCA-affected individuals, reporting rare variants as phase defined haplotypes with respect to the common missense alleles p.Ser192Tyr and p.Arg402Gln should now be the gold standard for describing the molecular profile of OCA type 1-affected individuals.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the families with oculocutaneous albinism who have contributed to this study and Dr. Kevin Brown for the control primary melanocyte cell lines. This study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health and was funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI: 1ZIAHG000136-21 and NHGRI: 1ZIAHG000215-18) and National Eye Institute (NEI: ZIA EY000476-10).

Author contributions

S.L., M.G., L.L., J.W., Y.S., and NISC Comparative Sequencing Program conducted experiments. S.L., L.L., M.G., F.D., L.B., D.W.Y.S., and NISC Comparative Sequencing Program performed formal analysis of data. S.L., L.L., and D.A. designed experiments. S.L., M.G., L.L., L.B., D.W., F.D., W.P., W.O., Y.S., and D.A. performed writing, review, and editing of manuscript. S.L. and D.A. were responsible for data conceptualization. D.A., W.O., and W.P. provided resources.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: June 15, 2023

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2023.05.012.

Contributor Information

Stacie K. Loftus, Email: sloftus@mail.nih.gov.

David R. Adams, Email: dadams1@mail.nih.gov.

Web resources

ClinVar (retrieval of previously annotated TYR variants), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/?gr=0&term=TYR%5Bgene%5D&redir=gene

dbSNP (population frequencies for single-nucleotide variants), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/

LDlink (to obtain haplotype frequencies for 1000 Genomes), https://ldlink.nci.nih.gov/

NEI Commons (intra-melanosomal domain of TYR), https://neicommons.nei.nih.gov/#/proteomeData

UCSF Chimera (TYR protein model measurements), https://rbvi.ucsf.edu/chimera/

Uniprot (TYR AlphaFold structure), https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/P14679/entry#structure

YASARA - Yet Another Scientific Artificial Reality Application (TYR protein model measurements), http://www.yasara.org/

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

The datasets supporting the current study are in the process of being deposited in dbGaP. Data are currently available on request from the corresponding author following a customary information transfer agreement process.

References

- 1.King R.A., Pietsch J., Fryer J.P., Savage S., Brott M.J., Russell-Eggitt I., Summers C.G., Oetting W.S. Tyrosinase gene mutations in oculocutaneous albinism 1 (OCA1): definition of the phenotype. Hum. Genet. 2003;113:502–513. doi: 10.1007/s00439-003-0998-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montoliu L., Grønskov K., Wei A.H., Martínez-García M., Fernández A., Arveiler B., Morice-Picard F., Riazuddin S., Suzuki T., Ahmed Z.M., et al. Increasing the complexity: new genes and new types of albinism. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27:11–18. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garrido G., Fernández A., Montoliu L. HPS11 and OCA8: Two new types of albinism associated with mutations in BLOC1S5 and DCT genes. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2021;34:10–12. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kausar T., Bhatti M.A., Ali M., Shaikh R.S., Ahmed Z.M. OCA5, a novel locus for non-syndromic oculocutaneous albinism, maps to chromosome 4q24. Clin. Genet. 2013;84:91–93. doi: 10.1111/cge.12019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raposo G., Marks M.S. The dark side of lysosome-related organelles: specialization of the endocytic pathway for melanosome biogenesis. Traffic. 2002;3:237–248. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.030401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tripathi R.K., Strunk K.M., Giebel L.B., Weleber R.G., Spritz R.A. Tyrosinase gene mutations in type I (tyrosinase-deficient) oculocutaneous albinism define two clusters of missense substitutions. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1992;43:865–871. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320430523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simeonov D.R., Wang X., Wang C., Sergeev Y., Dolinska M., Bower M., Fischer R., Winer D., Dubrovsky G., Balog J.Z., et al. DNA variations in oculocutaneous albinism: an updated mutation list and current outstanding issues in molecular diagnostics. Hum. Mutat. 2013;34:827–835. doi: 10.1002/humu.22315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grønskov K., Ek J., Sand A., Scheller R., Bygum A., Brixen K., Brondum-Nielsen K., Rosenberg T. Birth prevalence and mutation spectrum in danish patients with autosomal recessive albinism. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2009;50:1058–1064. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lasseaux E., Plaisant C., Michaud V., Pennamen P., Trimouille A., Gaston L., Monfermé S., Lacombe D., Rooryck C., Morice-Picard F., Arveiler B. Molecular characterization of a series of 990 index patients with albinism. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2018;31:466–474. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hudjashov G., Villems R., Kivisild T. Global patterns of diversity and selection in human tyrosinase gene. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74307. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shriver M.D., Parra E.J., Dios S., Bonilla C., Norton H., Jovel C., Pfaff C., Jones C., Massac A., Cameron N., et al. Skin pigmentation, biogeographical ancestry and admixture mapping. Hum. Genet. 2003;112:387–399. doi: 10.1007/s00439-002-0896-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sollis E., Mosaku A., Abid A., Buniello A., Cerezo M., Gil L., Groza T., Güneş O., Hall P., Hayhurst J., et al. The NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog: knowledgebase and deposition resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51:D977–D985. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tripathi R.K., Hearing V.J., Urabe K., Aroca P., Spritz R.A. Mutational mapping of the catalytic activities of human tyrosinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:23707–23712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaki M., Sengupta M., Mondal M., Bhattacharya A., Mallick S., Bhadra R., Indian Genome Variation Consortium. Ray K. Molecular and functional studies of tyrosinase variants among Indian oculocutaneous albinism type 1 patients. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2011;131:260–262. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jagirdar K., Smit D.J., Ainger S.A., Lee K.J., Brown D.L., Chapman B., Zhen Zhao Z., Montgomery G.W., Martin N.G., Stow J.L., et al. Molecular analysis of common polymorphisms within the human Tyrosinase locus and genetic association with pigmentation traits. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27:552–564. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin S., Sanchez-Bretaño A., Leslie J.S., Williams K.B., Lee H., Thomas N.S., Callaway J., Deline J., Ratnayaka J.A., Baralle D., et al. Evidence that the Ser192Tyr/Arg402Gln in cis Tyrosinase gene haplotype is a disease-causing allele in oculocutaneous albinism type 1B (OCA1B) NPJ Genom. Med. 2022;7:2. doi: 10.1038/s41525-021-00275-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toyofuku K., Wada I., Spritz R.A., Hearing V.J. The molecular basis of oculocutaneous albinism type 1 (OCA1): sorting failure and degradation of mutant tyrosinases results in a lack of pigmentation. Biochem. J. 2001;355:259–269. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3550259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hutton S.M., Spritz R.A. A comprehensive genetic study of autosomal recessive ocular albinism in Caucasian patients. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2008;49:868–872. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grønskov K., Jespersgaard C., Bruun G.H., Harris P., Brøndum-Nielsen K., Andresen B.S., Rosenberg T. A pathogenic haplotype, common in Europeans, causes autosomal recessive albinism and uncovers missing heritability in OCA1. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:645. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37272-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monfermé S., Lasseaux E., Duncombe-Poulet C., Hamel C., Defoort-Dhellemmes S., Drumare I., Zanlonghi X., Dollfus H., Perdomo Y., Bonneau D., et al. Mild form of oculocutaneous albinism type 1: phenotypic analysis of compound heterozygous patients with the R402Q variant of the TYR gene. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2019;103:1239–1247. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-312729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michaud V., Lasseaux E., Green D.J., Gerrard D.T., Plaisant C., UK Biobank Eye and Vision Consortium. Fitzgerald T., Birney E., Arveiler B., Black G.C., Sergouniotis P.I. The contribution of common regulatory and protein-coding TYR variants to the genetic architecture of albinism. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:3939. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-31392-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghodsinejad Kalahroudi V., Kamalidehghan B., Arasteh Kani A., Aryani O., Tondar M., Ahmadipour F., Chung L.Y., Houshmand M. Two novel tyrosinase (TYR) gene mutations with pathogenic impact on oculocutaneous albinism type 1 (OCA1) PLoS One. 2014;9:e106656. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mendez R., Iqbal S., Vishnopolska S., Martinez C., Dibner G., Aliano R., Zaiat J., Biagioli G., Fernandez C., Turjanski A., et al. Oculocutaneous albinism type 1B associated with a functionally significant tyrosinase gene polymorphism detected with Whole Exome Sequencing. Ophthalmic Genet. 2021;42:291–295. doi: 10.1080/13816810.2021.1888129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oetting W.S., Pietsch J., Brott M.J., Savage S., Fryer J.P., Summers C.G., King R.A. The R402Q tyrosinase variant does not cause autosomal recessive ocular albinism. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2009;149A:466–469. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karczewski K.J., Francioli L.C., Tiao G., Cummings B.B., Alföldi J., Wang Q., Collins R.L., Laricchia K.M., Ganna A., Birnbaum D.P., et al. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature. 2020;581:434–443. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2308-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jin Y., Birlea S.A., Fain P.R., Gowan K., Riccardi S.L., Holland P.J., Mailloux C.M., Sufit A.J.D., Hutton S.M., Amadi-Myers A., et al. Variant of TYR and autoimmunity susceptibility loci in generalized vitiligo. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;362:1686–1697. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norman C.S., O'Gorman L., Gibson J., Pengelly R.J., Baralle D., Ratnayaka J.A., Griffiths H., Rose-Zerilli M., Ranger M., Bunyan D., et al. Identification of a functionally significant tri-allelic genotype in the Tyrosinase gene (TYR) causing hypomorphic oculocutaneous albinism (OCA1B) Sci. Rep. 2017;7:4415. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04401-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan H.W., Schiff E.R., Tailor V.K., Malka S., Neveu M.M., Theodorou M., Moosajee M. Prospective Study of the Phenotypic and Mutational Spectrum of Ocular Albinism and Oculocutaneous Albinism. Genes. 2021;12:508. doi: 10.3390/genes12040508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loftus S.K., Lundh L., Watkins-Chow D.E., Baxter L.L., Pairo-Castineira E., Nisc Comparative Sequencing P., Jackson I.J., Oetting W.S., Pavan W.J., Adams D.R. A custom capture sequence approach for oculocutaneous albinism identifies structural variant alleles at the OCA2 locus. Hum. Mutat. 2021;42:1239–1253. doi: 10.1002/humu.24257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richards S., Aziz N., Bale S., Bick D., Das S., Gastier-Foster J., Grody W.W., Hegde M., Lyon E., Spector E., et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015;17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Machiela M.J., Chanock S.J. LDlink: a web-based application for exploring population-specific haplotype structure and linking correlated alleles of possible functional variants. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3555–3557. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang T., Choi J., Kovacs M.A., Shi J., Xu M., NISC Comparative Sequencing Program. Melanoma Meta-Analysis Consortium. Goldstein A.M., Trower A.J., Bishop D.T., et al. Cell-type-specific eQTL of primary melanocytes facilitates identification of melanoma susceptibility genes. Genome Res. 2018;28:1621–1635. doi: 10.1101/gr.233304.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Halaban R., Cheng E., Smicun Y., Germino J. Deregulated E2F transcriptional activity in autonomously growing melanoma cells. J. Exp. Med. 2000;191:1005–1016. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.6.1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lo H.S., Wang Z., Hu Y., Yang H.H., Gere S., Buetow K.H., Lee M.P. Allelic variation in gene expression is common in the human genome. Genome Res. 2003;13:1855–1862. doi: 10.1101/gr.1006603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pettersen E.F., Goddard T.D., Huang C.C., Couch G.S., Greenblatt D.M., Meng E.C., Ferrin T.E. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sherry S.T., Ward M.H., Kholodov M., Baker J., Phan L., Smigielski E.M., Sirotkin K. dbSNP: the NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:308–311. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reinisalo M., Putula J., Mannermaa E., Urtti A., Honkakoski P. Regulation of the human tyrosinase gene in retinal pigment epithelium cells: the significance of transcription factor orthodenticle homeobox 2 and its polymorphic binding site. Mol. Vis. 2012;18:38–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beby F., Lamonerie T. The homeobox gene Otx2 in development and disease. Exp. Eye Res. 2013;111:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu B., Calton M.A., Abell N.S., Benchorin G., Gloudemans M.J., Chen M., Hu J., Li X., Balliu B., Bok D., et al. Genetic analyses of human fetal retinal pigment epithelium gene expression suggest ocular disease mechanisms. Commun. Biol. 2019;2:186. doi: 10.1038/s42003-019-0430-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Varadi M., Anyango S., Deshpande M., Nair S., Natassia C., Yordanova G., Yuan D., Stroe O., Wood G., Laydon A., et al. AlphaFold Protein Structure Database: massively expanding the structural coverage of protein-sequence space with high-accuracy models. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50:D439–D444. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patel M., Sergeev Y. Functional in silico analysis of human tyrosinase and OCA1 associated mutations. J. Anal. Pharm. Res. 2020;9:81–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Landrum M.J., Chitipiralla S., Brown G.R., Chen C., Gu B., Hart J., Hoffman D., Jang W., Kaur K., Liu C., et al. ClinVar: improvements to accessing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:D835–D844. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tripathi R.K., Giebel L.B., Strunk K.M., Spritz R.A. A polymorphism of the human tyrosinase gene is associated with temperature-sensitive enzymatic activity. Gene Expr. 1991;1:103–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Currant H., Hysi P., Fitzgerald T.W., Gharahkhani P., Bonnemaijer P.W.M., Senabouth A., Hewitt A.W., UK Biobank Eye and Vision Consortium. International Glaucoma Genetics Consortium. Atan D., et al. Genetic variation affects morphological retinal phenotypes extracted from UK Biobank optical coherence tomography images. PLoS Genet. 2021;17:e1009497. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1009497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the current study are in the process of being deposited in dbGaP. Data are currently available on request from the corresponding author following a customary information transfer agreement process.