Abstract

We isolated a toluene-sensitive mutant, named mutant No. 32, which showed unchanged antibiotic resistance levels, from toluene-tolerant Pseudomonas putida IH-2000 by transposon mutagenesis with Tn5. The gene disrupted by insertion of Tn5 was identified as cyoC, which is one of the subunits of cytochrome o. The membrane protein, phospholipid, and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of IH-2000 and that of mutant No. 32 were examined and compared. Some of the outer membrane proteins showed a decrease in mutant No. 32. The fatty acid components of LPS were found to be dodecanoic acid, 2-hydroxydodecanoic acid, 3-hydroxydodecanoic acid, and 3-hydroxydecanoic acid in both IH-2000 and No. 32; however, the relative proportions of these components differed in the two strains. Furthermore, cell surface hydrophobicity was increased in No. 32. These data suggest that mutation of cyoC caused the decrease in outer membrane proteins and the changing fatty acid composition of LPS. These changes in the outer membrane would cause an increase in cell surface hydrophobicity, and mutant No. 32 is considered to be sensitive to toluene.

Organic solvents, such as toluene, xylene, and cyclohexane, are very toxic to microorganisms. Highly organic solvent-tolerant microorganisms which are tolerant to toluene have been isolated (15). There are various types of organic solvent molecules, such as alkanes, alkenes, cycloalkanes, cycloalkenes, and aromatics. It has been demonstrated that the degree of toxicity of an organic solvent corresponds to its log Pow value, which is the logarithm of the partition coefficient of the organic solvent between n-octanol and water (15, 16). Organic solvents with a low log Pow show higher toxicity to microorganisms (16). Since the discovery of Pseudomonas putida IH-2000, there have been many reports about toluene-tolerant microorganisms (18, 20–22, 26, 35). Most of these toluene-tolerant strains have been identified as Pseudomonas species (26). Organic solvent-tolerant microorganisms have attracted attention, due to the possibility of applying them to persolvent fermentation of water-insoluble compounds (6).

We have studied the mechanisms of toluene tolerance in P. putida IH-2000, and there have been various reports about such mechanisms in Pseudomonas species. The trans-lipid ratio of the cell membrane was found to increase in cells cultured in the presence of toluene (11, 13, 34, 44). It is thought that the membrane acquires rigidity and is less susceptible to structural disturbance caused by the organic solvent. Also, an increase in phospholipid biosynthesis is reported to occur during growth in the presence of an organic solvent, which could be one of the mechanisms of organic solvent tolerance (31). Recently, it has been reported that a multiantibiotic resistance system involving an antibiotic efflux pump contributes to organic solvent tolerance in microorganisms (13, 18, 20, 35, 44, 47). The antibiotic efflux pump is reported to pump antibiotics from inside the cells through an energy-dependent process (28, 30). Furthermore, some genes involved in toluene tolerance have been reported (21).

Many mutants either tolerant or sensitive to organic solvents have been isolated from Pseudomonas or Escherichia coli in previous studies (5, 13, 16, 21, 32). These mutants showed phenotypic changes not only in solvent tolerance levels but also in antibiotic resistance levels (5, 13). It is of interest to determine whether all organic solvent-tolerant systems of bacteria are included in antibiotic-resistant systems. In this study, we isolated a toluene-sensitive mutant, No. 32, which did not show altered antibiotic resistance levels, from toluene-tolerant P. putida IH-2000. The cell surface properties of mutant No. 32 and IH-2000 were compared.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmid.

The toluene-tolerant microorganism P. putida IH-2000, isolated by Inoue and Horikoshi (16), and a toluene-sensitive mutant, No. 32, derived from the strain IH-2000, were used in this study. The P. putida strains IFO3738 and IFO1506, both of which are sensitive to toluene, were employed as standard strains. Charomid 9-36 was used as a cloning vector for large DNA fragments (38) and was purchased from Nippon Gene Co. Ltd. (Toyama, Japan). Plasmid pMMB66EH was used as a vector for cloning the cyo gene cluster in E. coli or mutant No. 32 (14).

Culture media.

Escherichia coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium consisting of 10 g of Bacto Tryptone (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.), 5 g of yeast extract (Difco), and 10 g of NaCl (pH 7.0) per liter. Pseudomonas strains were grown in modified LB medium (15) (LB-Mg medium) containing 10 mmol of MgSO4 · 7H2O per liter. The organic solvent was added to the medium at a concentration of 10% (vol/vol). To cultivate bacteria, the media were supplemented with 1.5% (wt/vol) agar. Organic solvents were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries (Osaka, Japan).

Determination of MICs of antibiotics.

MICs were determined by twofold serial broth dilution in LB-Mg medium. The inoculum was 106 cells/ml, and the results were read after 36 h of incubation at 30°C. Growth was measured by optical density at 660 nm (OD660). An OD660 lower than 0.1 was considered negative.

Transposon mutagenesis.

Transposon Tn5 (8, 41) was used to prepare toluene-sensitive (Tol−) mutants. E. coli S17-1 (recA pro hsdR res mod+ RP4-Tc::Mu-Km::Tn7) cells harboring the plasmid pSUP2021 (41) grown at 37°C on an LB agar plate were mixed with P. putida IH-2000 cells grown at 30°C in LB liquid medium. Four hundred microliters of the cell mixture was spread on a sterilized cellulose filter on an LB agar plate. After a 6-h mating period at 30°C, the cells were resuspended in LB liquid medium and spread on an LB agar plate supplemented with nalidixic acid (50 μg/ml) and kanamycin (50 μg/ml), and the colonies that had formed after a 2-day incubation period at 30°C were replicated onto an LB agar plate. To detect toluene-sensitive mutants, each replica plate was overlaid with pure toluene and incubated for 2 days at 30°C.

Chromosomal DNA was isolated from P. putida IH-2000 and mutant No. 32 as described previously (38). Purified DNA was digested with appropriate restriction enzymes. The pattern of digestion of chromosomal DNA with each restriction enzyme was analyzed by electrophoresis in a 0.9% (wt/vol) agarose gel, and the digested fragments were vacuum blotted onto a Hybond N+ nylon membrane (Amersham, Uppsala, Sweden). A digoxigenin-labeled kanamycin resistance gene (3.4 kb) was used as a DNA probe to detect fragments containing the Tn5 element. Southern hybridization (1) was performed with a DIG labeling and detection kit (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany).

DNA sequencing and ORF analysis.

Sequencing was performed with an ABI PRISM 373 DNA sequencer and a dye terminator cycle-sequencing kit (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.). The sequences were analyzed for the locations of possible open reading frames (ORFs) with the GeneWorks program (version 2.5.1N) from IntelliGenetics Inc. (Campbell, Calif.). The deduced amino acid sequences of the identified ORFs were compared with sequences reported in a search of the nonredundant protein data bank with the FASTA and BLAST network service (14a).

Preparation of the soluble (cytoplasmic and periplasmic) and insoluble (envelope) fractions of the organism.

The Pseudomonas strains were aerobically grown at 30°C. Cells were harvested from 400 ml of culture (OD660 = 1.0) by centrifugation (3,500 × g; 10 min; 4°C) and washed once with cold 10 mM Na2HPO4-NaOH buffer (pH 7.0). Cells suspended in 5 ml of the same buffer were broken by sonication (20 W; 2 min) in an ice-water bath. After centrifugation to remove unbroken cells, preparation of the envelope fraction from the supernatant was carried out by further centrifugation (100,000 × g; 4°C; 45 min). This supernatant was used as the cytoplasmic fraction in this study, and the precipitate was used as the envelope fraction after being washed once with the same buffer. These fractions were stored at −40°C until use.

Protein content.

Protein content was measured by the method of Lowry et al. (24) or Bradford (9). Bovine serum albumin was used as the standard.

Phosphorus content.

The membrane or phospholipid samples were heated to ash to transform organic phosphorus compounds to inorganic phosphorus compounds. The ash samples were hydrolyzed by treatment with 0.5 N HCl at 100°C for 20 min to transform diphosphate into phosphate. Inorganic phosphorus was measured by the method of Ames (2).

Relative proportions of phospholipid molecules.

Phospholipids were extracted from membrane samples by the method of Bligh and Dyer (37). Each phospholipid sample (an amount corresponding to 90 nmol of phosphorus in each instance) was spotted onto a 0.2-mm-thick silica gel 60 plate (Merck), and the plate was developed with chloroform-methanol-acetic acid (65:25:8). Phospholipid molecules were detected with iodine vapor and each spot that appeared was removed from the thin-layer chromatography plate. The relative proportion of each phospholipid was determined from the amount of phosphorus in each spot.

Fatty acid analysis.

Phospholipids were extracted from membrane samples as described above and heated with 5% (wt/vol) methanolic HCl at 100°C for 3 h. The resulting fatty acid methyl esters were extracted twice with n-hexane and concentrated under a stream of nitrogen gas. The fatty acid methyl esters were analyzed with a gas-liquid chromatograph (model GC-380; GL-Science) or a gas-liquid chromatograph–mass spectrometer (model 5820-II gas chromatograph and model HP5971 mass selective detector; Hewlett-Packard).

Preparation and analysis of LPS.

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was extracted from 10 g (wet weight) of cells by the method of Westphal and Jann (46). After DNase and RNase treatment, the LPS fraction was dialyzed against 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) containing 0.1% (wt/vol) NaN3. Finally, the LPS fraction was freeze dried and stored at −80°C. The neutral sugar content and the 2-keto-3-deoxyoctonate content of LPS were determined by the phenol-H2SO4 method (42) and the method of Weissbach and Hurwitz (45), respectively. The lipid content and phosphorus content were determined by the methods described above.

SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) of proteins.

Proteins were analyzed on a 12.5% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gel by the method of Laemmli (23). Protein samples were dissolved in 1% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 2.5% (vol/vol) β-mercaptoethanol, 20% (wt/vol) sucrose, and 16 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 6.8) and heated at 100°C for 5 min. Protein in the gel was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250.

Cell surface hydrophobicity.

Hydrophobicity was measured by two methods. One was bacterial adhesion to hydrocarbon (BATH) (4). Pseudomonas strains were grown in LB-Mg medium. When the OD660 of the culture reached 0.6, the cells were harvested and washed twice with 0.8% NaCl. The cells were suspended in 4 ml of 0.8% (wt/vol) NaCl (OD660 = 0.6), and 0.6 ml of organic solvent (n-octane, n-hexane, cyclohexane, or p-xylene) was added. Bilayer solution was mixed for 1 min and left for 10 min at room temperature, and the OD660 of the water layer (A) was measured. BATH (%) was calculated from the following equation: BATH (%) = (1 − A/0.6) × 100.

The other method was hydrophobic interaction chromatography (HIC) (4). A cell suspension was prepared as described above. Two milliliters of cell suspension and 1 ml of butyl-Sepharose resin (Pharmacia Biotech Co.) were mixed and shaken at 90 rpm for 10 min. After the resin was removed by centrifugation (40 rpm; 10 s), the OD660 of the supernatant (A) was measured. HIC (%) was calculated from the following equation: HIC (%) = (1 − A/0.6) × 100.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of the 5.5-kb DNA fragment reported in this paper has been deposited in DDBJ with accession no. AB016787.

RESULTS

Isolation of toluene-sensitive mutant No. 32.

We isolated 20 toluene-sensitive mutants from among approximately 4,300 transconjugants which were absolutely unable to grow on an LB-Mg agar plate overlaid with toluene. Three toluene-sensitive mutants did not change their antibiotic resistance levels. We selected mutant No. 32 for use in further studies because its antibiotic resistance levels were stable. Figure 1 shows the growth of strain IH-2000 and that of mutant No. 32 in LB-Mg medium with or without addition of toluene at a concentration of 40% (vol/vol). IH-2000 could grow in the liquid medium containing toluene (doubling time, 1.11 h), whereas mutant No. 32 could not. This was in accordance with our finding that this mutant was unable to grow on agar medium overlaid with toluene. The doubling times of IH-2000 and that of mutant No. 32 in LB-Mg medium were 0.72 and 0.92 h, respectively. Toluene-tolerant revertants of mutant No. 32 did not appear during incubation. Both IH-2000 and mutant No. 32 grew in LB-Mg medium containing p-xylene or any less toxic organic solvent, such as cyclohexane, n-hexane, or n-octane (data not shown). In antibiotic resistance assays, the MIC values (μg/ml) of various antibiotics for both IH-2000 and mutant No. 32 were as follows: penicillin G, >4,000; novobiocin, >3,000; erythromycin, >1,024; ampicillin, 400; and chloramphenicol, 800.

FIG. 1.

Growth of P. putida IH-2000 and mutant No. 32 in medium with or without added toluene. IH-2000 (circles) and mutant No. 32 (triangles) were grown in LB-Mg medium at 30°C. Toluene at 40% (vol/vol) was added to each culture (solid symbols), and OD660 was measured.

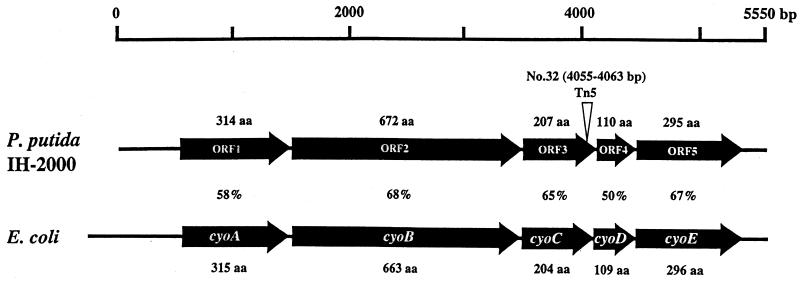

Characterization of the Tn5-transposed region and cloning of the cyo gene cluster.

An 8.8-kb KpnI fragment containing the Tn5 transposon (5.8 kb) was isolated from the chromosomal DNA of mutant No. 32 and cloned into Charomid 9-36. This fragment was partially sequenced around the Tn5 insertion site by means of Charomid primers (5′-AAAATAGGCGTATCACGAGG-3′ and 5′-TGACAGCTTGTATGTTTCTG-3′) and a Tn5 primer (5′-GGAGGTCACATGGAAGTCAGAT-3′), beginning at a 50-bp point within the IS50 sequence (39). Tn5 was inserted into ORF5 at 4,055 to 4,063 bp in No. 32 (Fig. 2). The 5.5-kb fragment containing the cyo gene cluster shown in Fig. 2 was further sequenced by the primer-walking method, and the whole sequence of this fragment was determined by a DNA sequencer, ABI PRISM 373. Five ORFs were identified in the 5.5-kb fragment; they were similar to E. coli cyoABCDE gene products (Fig. 2), which constitute cytochrome o, showing 58, 68, 65, 50, and 67% identity, respectively (39).

FIG. 2.

Cytochrome o gene (cyo) homologue in P. putida IH-2000. The arrows show possible ORFs, and the solid line indicates the sequenced region. The open arrowhead indicates the position of insertion of the Tn5 transposon. The amino acid (aa) sequence of the cyo homologue in P. putida IH-2000 was compared with that of a quinol oxidase from a gram-negative bacterium, E. coli cytochrome o. The percent identity between the ORF product and the quinol oxidase from E. coli is shown below each arrow.

A 6-kb DNA fragment containing the whole cyo gene and flanking region was amplified by PCR from the chromosomal DNA of the strain IH-2000 with a primer set (5′-CCCAAGCTTAATGGTCAAGTTGCGGCATCGACAC-3′ and 5′-CGGGATCCGATGTAGCGGCCTGGATCAGAAGAT-3′). PCR was performed with a DNA thermal cycler 9700 (Perkin-Elmer) under the following conditions: 25 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 1 min at 45°C, and 15 s at 72°C. After digestion of the amplified fragment with BamHI and HindIII, the fragment was ligated into BamHI/HindIII sites of pMMB67EH and the transformation to E. coli DH5α was performed by the standard method. Overexpression of cyo genes seems to be lethal for growth of E. coli DH5α, because the transformant harboring the plasmid pMCYO possessing the cyo gene cluster with the same transcriptional direction as the lac promoter in pMMB66EH was not isolated.

Membrane proteins and intracellular proteins of IH-2000 and mutant No. 32.

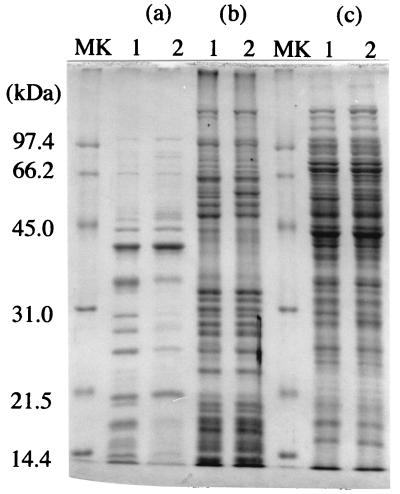

The ratio of outer membrane proteins to total membrane protein of No. 32 was 0.16, which was less than that of IH-2000 (ratio, 0.26). The SDS-PAGE profiles of the outer membrane proteins differed substantially in IH-2000 and mutant No. 32. The major outer membrane proteins of IH-2000 consisted of 40-, 33-, 24-, and 18-kDa proteins and other minor proteins. On the other hand, in the case of mutant No. 32, only one major outer membrane protein was present, a 40-kDa protein, and there were other minor proteins. The minor proteins of mutant No. 32 had almost the same molecular mass as the major proteins of IH-2000. A few differences were found in protein bands when the inner membrane proteins of IH-2000 and No. 32 were compared. Two protein bands were found in positions corresponding to a molecular mass of almost 50 kDa in the case of IH-2000, but only one protein band was found in this position in the case of No. 32. Furthermore, one 13-kDa protein band was found in the case of IH-2000 but two protein bands of almost 13-kDa were found in the case of mutant No. 32. There was no substantial difference between the SDS-PAGE profiles of intracellular proteins in IH-2000 and mutant No. 32.

LPSs of IH-2000 and mutant No. 32.

The SDS-PAGE profiles of LPSs extracted from IH-2000 and mutant No. 32 each showed three bands, and there was no substantial difference observed (data not shown). The ratios of neutral sugars to 2-keto-3-deoxyoctonate in the LPSs of IH-2000 and No. 32 were 8.3 and 9.0, respectively. The fatty acid components of the LPS were 3-hydroxydecanoic acid (10:0-3OH), dodecanoic acid (12:0), 2-hydroxydodecanoic acid (12:0-2OH), and 3-hydroxydodecanoic acid (12:0-3OH) in both IH-2000 and mutant No. 32 as determined by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (data not shown). The relative proportions of 12:0 and 12:0-2OH differed between IH-2000 (40.3% ± 0.3% and 21.4% ± 0.0%, respectively) and mutant No. 32 (29.7% ± 0.6% and 30.9% ± 0.0%, respectively) (Table 1). There was no substantial difference between the relative proportions of 10:0-3OH and 12:0-3OH in IH-2000 and mutant No. 32 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Fatty acid composition of LPS

| Fatty acida | Compositionb (%)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| IH-2000 | No. 32 | No. 32(pMCYO)c | |

| 12:0 | 40.4 ± 0.3 | 29.7 ± 0.6 | 33.2 |

| 10:0-3OH | 16.1 ± 0.3 | 17.6 ± 0.6 | 15.2 |

| 12:0-2OH | 21.4 ± 0.0 | 30.9 ± 0.0 | 26.5 |

| 12:0-3OH | 22.1 ± 0.0 | 21.9 ± 0.0 | 25.1 |

12:0, dodecanoic acid; 10:0-3OH, 3-hydroxydecanoic acid; 12:0-2OH, 2-hydroxydodecanoic acid; 12:0-3OH, 3-hydroxydodecanoic acid.

Mean ± standard deviation (n = 3).

Complemented with toluene tolerance by pMCYO.

Analysis of the phospholipids of IH-2000 and No. 32.

The phospholipids found in IH-2000 and mutant No. 32 were phosphatidyl-ethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylglycerol (PG), and cardiolipin (CL). The relative proportion of PG in mutant No. 32 was 12.0% ± 2.9%, which was about 1.5 times as much as that in IH-2000 (7.9% ± 0.9%) (Table 2). The relative proportions of PE and CL were slightly decreased in mutant No. 32 because of the elevated PG content. Other phospholipids were not detected by iodine vapor. The fatty acid components of the membrane phospholipids were palmitic acid (16:0), palmitoleic acid (16:1), trans-hexadecenoic acid (16:1t), and oleic acid (18:1). The 18:1 content in mutant No. 32 was 16.5%, larger than the 12.0% in IH-2000 (Table 3). Both the 16:0 content and the 16:1t content in mutant No. 32 were lower than in IH-2000.

TABLE 2.

Ratio of phospholipid molecules

| Phospholipid | Ratio (%)a

|

|

|---|---|---|

| IH-2000 | No. 32 | |

| PE | 86.9 ± 0.6 | 83.0 ± 3.0 |

| PG | 7.9 ± 0.9 | 12.0 ± 2.9 |

| CL | 5.3 ± 0.3 | 4.7 ± 0.0 |

Mean ± standard deviation (n = 3).

TABLE 3.

Fatty acid composition of phospholipid

| Fatty acida | Composition (%)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| IH-2000 | No. 32 | |

| 16:0 | 45.7 | 43.1 |

| 16:1 | 34.5 | 34.4 |

| 16:1t | 7.7 | 6.0 |

| 18:1 | 12.1 | 16.5 |

16:0, palmitic acid; 16:1, palmitoleic acid; 16:1t, trans-hexadecenoic acid; 18:1, oleic acid.

Cell surface hydrophobicity of IH-2000 and No. 32.

Table 4 shows the cell surface hydrophobicities of IH-2000 and mutant No. 32 measured by BATH and HIC. The adhesions of IH-2000 to n-hexane, cyclohexane, and p-xylene were 0.00, 30.7, and 32.7%, respectively. On the other hand, those of No. 32 were 25.6, 53.4, and 72.0%. Neither strain adhered to n-octane. In the case of the HIC method, the adhesions of IH-2000 and No. 32 to butyl-Sepharose were 14.0 and 27.9. Both methods indicated that the cell surface of strain No. 32 was more hydrophobic than that of IH-2000.

TABLE 4.

Cell surface hydrophobicities of IH-2000 and No. 32

| Method and adsorbent | Hydrophobicity (%)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| IH-2000 | No. 32 | |

| BATH | ||

| n-Octane | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| n-Hexane | 0.0 | 25.6 |

| Cyclohexane | 30.7 | 53.4 |

| p-Xylene | 32.7 | 72.0 |

| HIC Butyl-Sepharose | 14.0 ± 0.6a | 27.9 ± 1.0a |

Mean ± standard deviation (n = 3).

Complementation of toluene tolerance.

Mutant No. 32 was transformed with pMCYO by the CaCl2 method (25). The transformants were selected on LB-Mg agar plates containing carbenicillin (2 mg/ml) (LB-MgC). Each transformant was grown on an LB-MgC plate overlaid with toluene or in an LB-MgC liquid medium containing 50% toluene at 30°C. The properties of the 14 transformants that acquired toluene tolerance were not equal to the wild-type strain IH-2000 and were somewhat unstable compared with IH-2000. No. 32 mutants carrying pMCYO showed toluene tolerance; however, their toluene tolerance levels were apparently lower than those of IH-2000. More than 70% of IH-2000 cells showed toluene tolerance; on the other hand, 10 to 20% of the transformant cells showed tolerance to toluene. Furthermore, one of the transformants could grow on LB-Mg medium containing toluene at an OD660 of 0.60, whereas IH-2000 could grow on the same medium at an OD660 of 0.85 (Fig. 1). SDS-PAGE profiles of outer membrane proteins of transformants were almost same as that of IH-2000 protein (data not shown). The LPS lipids of one of the transformants were as follows: 12:0, 33.2%; 10:0-3OH, 15.2%; 12:0-2OH, 26.5%; and 12:0-3OH, 25.1% (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

We isolated a toluene-sensitive mutant, No. 32, whose antibiotic resistance levels did not change as a result of inserting Tn5. The gene in which Tn5 was inserted, ORF5, showed 65% identity with E. coli cyoC (Fig. 2). CyoC is reported to be one of the subunits of cytochrome o and is required for the assembly of the metal centers in CyoB (10, 12, 33). The cytochrome o branch of the respiratory chain shows very low activity under normal laboratory growth conditions (3, 7, 36, 43). Our finding that the cyo mutant, No. 32, grew slightly more slowly than the cyo+ strain IH-2000 (doubling time, 0.72 h [IH-2000] versus 0.92 h [No. 32]) is in accordance with the findings for E. coli. Furthermore, there was no substantial difference in the N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-1,4-phenylenediamine oxidase activities or absorbance spectral properties of mutant No. 32 and IH-2000 (data not shown). Actually, it is known that cytochrome d (cyd) is expressed mainly in the stationary growth phase in gram-negative bacteria, such as E. coli and P. putida (9, 27, 43), and cyd is usually used instead of cyo in cyo-deficient mutants of E. coli. Although the cyd of IH-2000 has not been identified yet, the cyo mutant No. 32 may use cyd. There would be enough energy for an efflux pump of antibiotics because there is no difference between the MICs for IH-2000 and No. 32. Therefore, the loss of toluene tolerance in mutant No. 32 may be due to changes in the outer membrane rather than to an altered respiratory chain.

The complementary experiments showed that the No. 32 transformants carrying pMCYO did not have the same toluene tolerance level as IH-2000. The outer membrane protein profiles of these transformants were almost the same as that of IH-2000 (data not shown), but LPS lipid compositions were different from those of IH-2000 and No. 32. Both LPS lipid composition and outer membrane protein would be related to toluene tolerance in IH-2000. Further study of the change in LPS lipid composition is needed.

Differences between IH-2000 and mutant No. 32 were evident when their outer membrane proteins and fatty acid components of LPS were compared (Fig. 3 and Table 1). These changes cause an increase in cell surface hydrophobicity (Table 4). It has been reported that the cell surfaces of organic solvent-tolerant mutants isolated from E. coli were more hydrophilic than those of their parent strain (4). Therefore, the loss of toluene tolerance in mutant No. 32 was due to an increase in the cell’s hydrophobicity. E. coli strains which were sensitive to p-xylene and cyclohexane adhered to n-octane in the BATH method (4). In this study, neither IH-2000 nor No. 32, which were tolerant to p-xylene, adhered to n-octane in the BATH method (Table 4). Cell surface hydrophobicity could play an important role in the organic solvent tolerance systems of microorganisms.

FIG. 3.

SDS-PAGE of membrane proteins and intracellular proteins from P. putida IH-2000 and mutant No. 32. Membrane proteins and intracellular proteins (30 μg) (c) were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Membrane proteins (35 μg) were dissolved in 0.5% sodium N-lauroyl sarcosinate and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Outer membrane proteins (insoluble fraction) (a) and inner membrane proteins (soluble fraction) (b) were prepared by centrifugation (100,000 × g; 1 h; 4°C). Outer membrane proteins (10 μg) and 25 μg of inner membrane protein were applied. Lanes: 1, IH-2000; 2, mutant No. 32; MK, molecular mass markers.

It has been reported that a decrease in high-molecular-weight LPS occurs in the case of cells grown in a medium containing o-xylene (31). In this study, a difference in the fatty acid composition of LPS was found in IH-2000 and No. 32 rather than a difference in the SDS-PAGE profile of LPS. It is known that lipid A shows heterogeneity with respect to the content of hydroxylated and nonhydroxylated dodecanoic acid, and it has been documented that nonhydroxylated dodecanoic acid can be esterified to either of the amide-linked 3-hydroxydodecanoic acids (22). Although the structure of lipid A from P. putida strains is still unknown, the content of nonhydroxylated dodecanoic acid may show an amount of esterified hydroxy fatty acids similar to those in the LPSs of other bacteria (22).

Several possible mechanisms of organic solvent tolerance in bacteria have been reported (34, 47). The cis-trans isomerization of fatty acids is reported to be one of the adaptive mechanisms contributing to organic solvent tolerance (11, 15, 34, 40, 44). Low cell surface hydrophobicity is reported to serve as a defensive mechanism which prevents accumulation of organic solvent molecules in the membrane (4). Our results showed that some outer membrane proteins were lost in No. 32 (Fig. 3). The Srp protein was reported as a channel protein of the solvent efflux pump system in the outer membrane (18, 35). These efflux pump systems were reported to be linked to multidrug efflux pump systems. When these pump systems were disrupted, not only the organic solvent tolerance level but also the MICs of antibiotics were reduced (13). IH-2000 and No. 32 showed almost the same level of antibiotic resistance. Therefore, the loss of the toluene tolerance system in No. 32 could be due to an increase in the cell’s hydrophobicity rather than to loss of the outer membrane channel protein of the efflux pump. It was reported that the loss of one of the outer membrane proteins increased the cell surface hydrophobicity (29). Therefore, loss of outer membrane proteins mainly affected the cell surface hydrophobicity of toluene-sensitive mutant No. 32 (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the relationship between the cyo mutation and the changes found in the outer membrane is unknown. Further study will be needed.

Compared to the number of reports about cell surface changes, there have been few reports about the genes concerned with bacterial organic solvent tolerance and cell surfaces (17, 20, 47). In this paper, we showed that the cyo gene contributes to a toluene tolerance mechanism which appears to be independent of the antibiotic resistance system. Recently, Kim et al. reported that genes associated with toluene tolerance in a P. putida strain were those encoding a solvent efflux pump, an ABC transporter, a periplasmic linker protein, and so on (21). Except for the gene encoding the solvent efflux pump, these genes may be present in normal P. putida strains whose organic solvent tolerance level is low, that is, strains sensitive to p-xylene (log Pow, 3.1). The toluene tolerance system, which is not present in normal P. putida strains, might be regulated by these genes as shown in this report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abuse F M, Brunt R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Short protocols in molecular biology (a compendium of methods from current protocols in molecular biology) 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1992. pp. 2-10–2-12. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ames B N. Assay of inorganic phosphate, total phosphate and phosphatases. Methods Enzymol. 1966;8:115–118. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anraku Y, Gennis R B. The aerobic respiratory chain of Escherichia coli. Trends Biochem Sci. 1987;12:262–266. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aono R, Kobayashi H. Cell surface properties of organic solvent-tolerant mutants of Escherichia coli K-12. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3637–3642. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.9.3637-3642.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aono R, Kobayashi M, Nakajima H, Kobayashi H. A close correlation between improvement of organic solvent tolerance levels and multiple antibiotics resistance in Escherichia coli. Biosci Biotech Biochem. 1995;59:213–218. doi: 10.1271/bbb.59.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aono R, Doukyu N, Kobayashi H, Nakajima H, Horikoshi K. Oxidative bioconversion of cholesterol by Pseudomonas sp. strain ST-200 in a water-organic solvent two-phase system. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2518–2523. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.7.2518-2523.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Au D C T, Lorence R M, Gennis R B. Isolation and characterization of an Escherichia coli mutant lacking the cytochrome o terminal oxidase. J Bacteriol. 1985;161:123–127. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.1.123-127.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berg D E. Transposon. In: Berg D E, Howe M M, editors. Mobile DNA. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1989. pp. 189–192. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chepuri V, Lemieux L, Au D C T, Gennis R B. The sequence of the cyo operon indicates substantial structural similarities between the cytochrome o ubiquinol oxidase of Escherichia coli and the aa3-type family of cytochrome c oxidases. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:11185–11192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diefenbach R, Heipieper H J, Keweloh H. The conversion of cis into trans unsaturated fatty acids in Pseudomonas putida P8: evidence for a role in the regulation of membrane fluidity. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1992;38:382–387. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukaya M, Tayama K, Tamaki T, Ebisuya H, Okumura H, Kawamura Y, Horinouchi S, Beppu T. Characterization of a cytochrome a1 that functions as a ubiquinol oxidase in Acetobacter aceti. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4307–4314. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.14.4307-4314.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukumori F, Hirayama H, Takami H, Inoue A, Horikoshi K. Isolation and transposon mutagenesis of a Pseudomonas putida KT2442 toluene-resistant variant: involvement of an efflux system in solvent resistance. Extremophiles. 1998;2:395–400. doi: 10.1007/s007920050084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fürste J P, Werner P, Ronald F, Helmut B, Peter S, Michael B, Erich L. Molecular cloning of the plasmid RP4 primase region in a multi-host-range tacP expression vector. Gene. 1986;48:119–131. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90358-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14a.Genome Net WWW Server. April 1999, copyright date. [Online.] http://www.genome.ad.jp. [12 June 1999, last date accessed.]

- 15.Heipieper H J, Diefenbach R, Keweloh H. Conversion of cis unsaturated fatty acids to trans: a possible mechanism for the protection of phenol-degrading Pseudomonas putida P8 from substrate toxicity. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:1847–1852. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.6.1847-1852.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inoue A, Horikoshi K. A Pseudomonas thrives in high concentrations of toluene. Nature. 1989;338:264–266. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inoue A, Horikoshi K. Estimation of solvent-tolerance of bacteria by the solvent parameter Log P. J Ferment Bioeng. 1991;71:194–196. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Isken S, de Bont J A M. Active efflux of toluene in a solvent-resistant bacterium. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6056–6058. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.20.6056-6058.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Isken S, de Bont J A M. Bacteria tolerant to organic solvents. Extremophiles. 1998;2:229–238. doi: 10.1007/s007920050065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kieboom J, Dennis J J, de Bont J A M, Zylstra G J. Identification and molecular characterization of an efflux pump involved in Pseudomonas putida S12 solvent tolerance. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:85–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim K, Lee S, Lee K, Lim D. Isolation and characterization of toluene-sensitive mutants from the toluene-resistant bacterium Pseudomonas putida GM73. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3692–3696. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.14.3692-3696.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kulshin V, Zahringer U, Lindner B, Jager K-E, Dmitriev B A, Rietschel E T. Structural characterization of the lipid A component of Pseudomonas aeruginosa wild-type and rough mutant lipopolysaccharides. Eur J Biochem. 1991;198:697–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mandel M, Higa A. Calcium dependent bacteriophage DNA infection. J Mol Biol. 1970;53:159–162. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(70)90051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakajima H, Kobayashi H, Aono R, Horikoshi K. Effective isolation and identification of toluene-tolerant Pseudomonas strains. Biosci Biotech Biochem. 1992;56:1872–1873. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakamura H, Saiki K, Mogi T, Anraku Y. Assignment and functional roles of the cyoABCDE gene products required for the Escherichia coli bo-type quinol oxidase. J Biochem. 1997;122:415–421. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nikaido H. Multidrug efflux pumps of gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5853–5859. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.20.5853-5859.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parker N D, Munn C B. Increased cell surface hydrophobicity associated with possession of an additional surface protein by Aeromonas salmonicida. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1984;21:233–237. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paulsen I T, Brown M H, Skurray R A. Proton-dependent multidrug efflux systems. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:575–608. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.4.575-608.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pinkart H C, White D C. Phospholipid biosynthesis and solvent tolerance in Pseudomonas putida strains. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4219–4226. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.13.4219-4226.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pinkart H C, Wolfram J W, Rogers R, White D C. Cell envelope changes in solvent-tolerant and solvent-sensitive Pseudomonas putida strains following exposure to o-xylene. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1129–1132. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.3.1129-1132.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Puustinen A, Finel M, Virkki M, Wikstrom M. Cytochrome o (bo) is a proton pump in Paracoccus denitrificans and Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1989;249:163–167. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)80616-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramos J L, Duque E, Rodriguez-Herva J J, Godoy P, Haidour A, Reyes F, Fernandez-Barrero A. Mechanisms for solvent tolerance in bacteria. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3887–3890. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.3887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramos J L, Duque E, Godoy P, Segura A. Efflux pumps involved in toluene tolerance in Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3323–3329. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.13.3323-3329.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rice C W, Hempfling W P. Oxygen-limited continuous culture and respiratory energy conservation in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1978;134:115–124. doi: 10.1128/jb.134.1.115-124.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rouser G, Fleischer S. Isolation, characterization, and determination of polar lipids of mitochondria. Methods Enzymol. 1967;10:385–406. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saraste M, Holm L, Lemieux L, Lubben M, van der Oost J. The happy family of cytochrome oxidases. Biochem Soc Trans. 1991;19:608–612. doi: 10.1042/bst0190608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sikkema J, de Bont J A M, Poolman B. Interactions of cyclic hydrocarbons with biological membranes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:8022–8028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simon R, Priefer U, Puhler A. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram-negative bacteria. Bio/Technology. 1983;1:784–791. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spiro R G. Analysis of sugars found in glycoproteins. Methods Enzymol. 1966;8:3–26. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sweet W J, Peterson J A. Changes in cytochrome content and electron transport patterns in Pseudomonas putida as a function of growth phase. J Bacteriol. 1978;133:217–224. doi: 10.1128/jb.133.1.217-224.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weber F J, de Bont J A M. Adaptation mechanisms of microorganisms to the toxic effects of organic solvents on membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1286:225–245. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4157(96)00010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weissbach A, Hurwitz J. The formation of 2-keto-3-deoxyheptonic acid in extracts of Escherichia coli B. J Biol Chem. 1959;234:705–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Westphal O, Jann K. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Extraction with phenol-water and further application of the procedure. In: Whistler R L, editor. Methods in carbohydrate chemistry. Vol. 5. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1965. pp. 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- 47.White D G, Goldman J D, Demple B, Levy S B. Role of the acrAB locus in organic solvent tolerance mediated by expression of marA, soxS, or robA in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6122–6126. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.19.6122-6126.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]