Abstract

Objectives

To explore avoidant behaviour of frequent emergency department (ED) users, reasons behind ED avoidance and healthcare-seeking behaviours in avoiders during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Design and setting

Cross-sectional, telephone-based survey administered between March and August 2021 at a tertiary care centre in Beirut, Lebanon.

Participants

Frequent ED users (defined as patients who visited the ED at least four times during the year prior to the first COVID-19 case in Lebanon).

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary outcome was ED avoidance among frequent ED users. Secondary outcomes included reasons behind ED avoidance and healthcare-seeking behaviours in avoiders.

Results

The study response rate was 62.6% and 286 adult patients were included in the final analysis. Within this sample, 45% (128/286) of the patients reported avoidant behaviour. Male patients were less likely to avoid ED visits than female patients (adjusted OR (aOR), 0.53; 95% CI 0.312 to 0.887). Other independent variables associated with ED avoidance included university education (aOR, 1.76; 95% CI 1.004 to 3.084), concern about contracting COVID-19 during an ED visit (aOR, 1.31; 95% CI 1.199 to 1.435) and underlying lung disease (aOR, 3.39; 95% CI 1.134 to 10.122). The majority of the patients who experienced acute complaints and avoided the ED completely (n=56) cited fear of contracting COVID-19 as the main reason (89.3% (50/56)). Most of the ED avoiders (83.9% (47/56)) adopted alternatives for seeking acute medical care, including messaging/calling a doctor (46.4% (26/56)), visiting a clinic (25.0% (14/56)), or arranging for a home visit (17.9% (10/56)). Of the avoiders, 64.3% (36/56) believed that the alternatives did not impact the quality of care, while 30.4% (17/56) reported worse quality of care.

Conclusions

Among frequent ED users, ED avoidance during COVID-19 was common, especially among women, those with lung disease, those with university-level education and those who reported fear of contracting COVID-19 in the ED. While some patients resorted to alternative care routes, telemedicine was still underused in our setting. Developing strategies to reduce ED avoidance, especially in at-risk groups, may be warranted during pandemics.

Keywords: epidemiology, quality in health care, public health, accident & emergency medicine

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

This study focuses on a segment of patients with high baseline emergency department (ED) utilisation rates.

This study investigated reasons for ED avoidance and explored patterns of healthcare-seeking behaviours in avoiders during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This was a single-centre study conducted in a tertiary care centre ED in Beirut, which limits generalisability to the population at large.

The limited response rate of 62.6% suggests the possibility of sampling/non-response bias, which may impact the representativeness of the sample.

Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, emergency departments (EDs) experienced drops in their ED visit volume globally. These drops were observed in settings with variable transmission rates, from high community transmission settings to ones with stringent containment strategies and low community prevalence. While stronger drops were observed for certain conditions and demographics, with bigger drops in communicable diseases and paediatrics, all types of ED presentations seem to have been impacted.1

Lower ED utilisation rates during the pandemic can partially be explained by drops in common communicable diseases as countries went into lockdown and practised social distancing. Emerging data also suggest that ED avoidance seems to have played a significant role in reducing ED utilisation during the pandemic. A study in Portugal found that 24.5% of patients who perceived a need for acute ED care during the pandemic avoided the ED.2 These findings have also been reported in other settings including the USA and Australia where avoidance of any type of medical care during the pandemic was found to be as high as 32.9% and emergency care avoidance ranged between 10.1% and 12%.3 4

While the impact of ED avoidance on patient outcomes has not been established, there are growing data on excess deaths observed during the pandemic. One study in the USA, looking at excess deaths during the pandemic, estimated that there were 87 001 excess deaths in the early weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic. Only 65% of these excess deaths were attributed to COVID-19, while 35% were attributed to causes other than COVID-19.5 In Lebanon, patients presenting to the ED during the COVID-19 lockdown period had higher hospital and critical care admission rates and double the mortality rate, reflecting a sicker demographic.6 Similar data have emerged from other countries where EDs witnessed a rise in the proportion of cases presenting with higher complexity,7 8 with some EDs also reporting increases in overall mortality of patients presenting to the ED during the pandemic.9 This suggests that patients may have avoided seeking ED care during the early phase of their illnesses, leading to delayed and more advanced presentations.

Studies that have looked at ED avoidance behaviour during the pandemic have focused on establishing the behaviour, with little exploration of alternatives sought by patients or the reasons behind ED avoidance. Possible reasons mentioned in the literature include limited ability to visit medical facilities due to lockdown,10 fear of not receiving proper treatment due to healthcare providers' fatigue or lack of resources, and patient avoidance out of concerns about burdening the already overloaded emergency medical system.11

Exploring perceived barriers to ED utilisation amidst pandemics is an important step to understanding health-seeking behaviours during pandemics and associations with care outcomes. This study aims to explore the ED avoidance of frequent ED users during the COVID-19 pandemic, reasons behind ED avoidance and patterns of healthcare-seeking behaviours among avoiders.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional, telephone-based survey on frequent adult ED users, 1 year into the COVID-19 pandemic in Lebanon.

Study design and setting

The American University of Beirut Medical Center (AUBMC) is a 384-bed tertiary care teaching hospital in Beirut, Lebanon. The ED is one of the largest in the country with an annual pre-COVID volume of 57 000 visits. The ED is divided into three clinical sections: high acuity, low acuity and paediatrics. Patients are triaged to sections based on a combination of Emergency Severity Index and clinical criteria. The ED is staffed by a mix of emergency medicine (EM) trained physicians and practitioners with extensive EM experience. On average, 80% of ED patients are insured, while the remaining 20% are self-payers. Frequent adult ED users comprise 2.3% of the annual adult ED visits, with a mean age of 46 years and hospitalisation rates of 24% compared with the overall ED admission rate of 19%, reflecting a higher complexity of cases within this subgroup.

Our institution has a fully integrated electronic medical record system that was implemented in 2018. Telehealth service utilisation was initiated during the pandemic and made available to patients across the ambulatory outpatient services by appointment but was not available as an urgent care drop-in service within the ED.

During the time of the survey (1 March till 30 August 2021), Lebanon was recovering from a postholiday COVID-19 surge that had peaked in January 2021 with a peak positivity rate of 22.8%. A stringent lockdown was imposed in January to mitigate the spread of the virus, followed by the initiation of the COVID-19 vaccination campaign on 14 February 2021, targeting high-risk groups. By 23 April 2021, positivity rates had dropped down to their presurge value of 12.4%.

Selection of participants

The study population was selected from 1313 adult frequent ED users at AUBMC, defined as patients who visited the ED at least four times during the year prior to the first COVID-19 case in Lebanon (21 February 2020).12 13 Selection was conducted on the basis of weighted random sampling that accounted for the annual number of ED visits per patient. Sample size was calculated based on a confidence of 95%, a margin of error of 5% and a proposed 40% probability of ED avoidance. The target sample size to be achieved was 286 patients.

Data collection and processing

The patient’s age, sex and comorbidities were retrieved from medical records. All other variables were obtained by means of a telephone survey. The latter was developed by experts in the fields of EM and epidemiology and was pilot tested and revised. Survey questions were originally written in English and were made available in Arabic as well after a process of translation and back-translation by two independent translators.

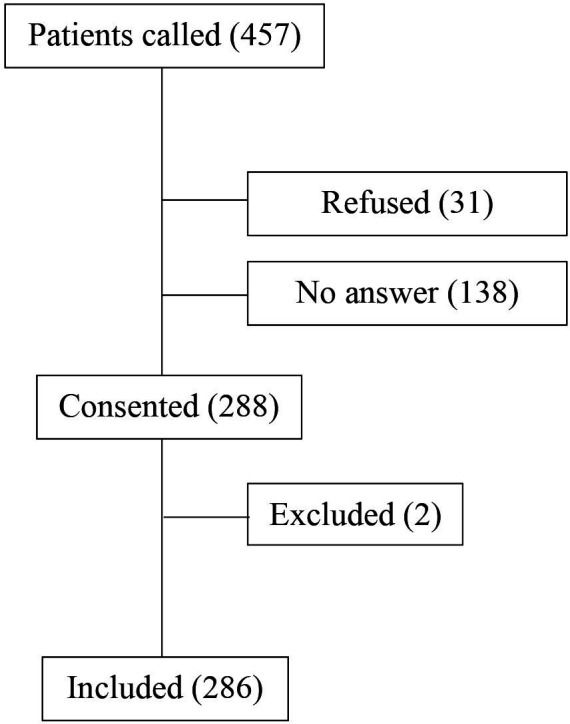

The telephone survey was administered between 1 March and 30 August 2021, by a team of four trained physicians and medical students, under the supervision of a clinical research coordinator. A maximum number of five phone calls per patient were attempted. The target sample size of 286 patients was achieved after 457 patients were contacted (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patient recruitment flow chart.

The survey contained 23 questions that comprised the following domains: demographics, concern about contracting COVID-19, self-reported changes in ED utilisation, reasons behind these changes, alternative means for medical attention, and health outcomes. Demographics included nationality, marital status, household composition, education level and residence area. Concerns about contracting COVID-19 were assessed based on Likert Scale of 0 to 10, where zero reflects ‘no concern’ and 10 reflects ‘extreme concern’. To define our primary variable of interest—ED avoidance/non-avoidance—we considered the following as avoidant behaviour: participants who reported decreased ED utilisation during COVID-19, those who reported complete avoidance of the ED during COVID-19, or those who reported waiting longer to present to the ED for acute symptoms than they would have had to prior to COVID-19. Additional variables targeting quality of care were collected: death rates between avoiders and non-avoiders during the COVID-19 pandemic and perceived impact on quality of care in those who sought alternative care sites for acute medical complaints during COVID-19 (online supplemental appendix 1).

bmjopen-2023-072117supp001.pdf (3.3MB, pdf)

Ethical considerations

Verbal informed consent was obtained from each participant. Cognitive capacity verification was done using the Older Adults’ Capacity to Consent to Research Scale.14 If the patient did not meet the capacity to consent to research or was deceased, their next of kin was surveyed on their behalf after obtaining verbal informed consent. Confidentiality was guaranteed by removing all patient identifiers from the database after data collection.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed using number and percentage for categorical variables, whereas medians/IQRs were used for continuous variables. Comparison between the two group avoiders and non-avoiders was carried out using the Student’s t-test for continuous variables or the χ2 test for categorical variables. A backward stepwise multivariate logistic regression model was further built to identify variables associated with decreased utilisation of ED services. Considered in this model were variables known to have clinical significance as well as those that showed statistical significance at the bivariate level. Variables included in the model were age, gender, marital status, household composition, education, concern about contracting COVID-19 in daily life, concern about contracting COVID-19 during an ED visit and patients having an underlying lung disease. These were summarised by the ORs with 95% CIs. Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS, V.28). A value of p<0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance.

Patient and public involvement

None.

Results

The study response rate was 62.6%. A total of 286 adult patients were included in the final analysis. Respondents had a median age of 39 years (Q1, Q3: 26, 61.25) and 48% (138/286) were female.

Sociodemographic characteristics

Table 1 presents a comparison of the sociodemographic characteristics among the group of patients who avoided or delayed ED visits (n=128) versus those who did not (n=158). Among the avoiders, 67.2% (86/128) of participants reported a decrease in utilisation of ED services, 25% (32/128) reported complete avoidance of ED services and 7.8% (10/128) reported delaying ED visits when they had acute symptoms. There was a statistically significant difference among both groups with regards to gender and the score of concern about contracting COVID-19 both in daily life and during an ED visit. A greater proportion of female respondents reported avoiding or delaying ED visits compared with those who did not (59.4% (76/128) vs 39.2% (62/158), p<0.01). Patients who avoided the ED had a statistically significant higher median score for concern about contracting COVID-19 in their daily life (8.0, 5.0–9.0) compared with those with no reported COVID-19 impact on ED utilisation (5.0, 2.0–8.0; p<0.01). A similar trend was observed for the concern about contracting COVID-19 during an ED visit for patients who avoided the ED (9.0, 7.0–10.0) and those who did not avoid or delay ED visits (5.0, 2.0–8.00; p<0.01).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of ED avoiders and non-avoiders

| Total population (n=286) | Avoiders (n=128) | Non-avoiders (n=158) | P value | ||

| Demographic characteristics | |||||

| Age, years | 18–24 | 65 (22.7%) | 31 (24.2%) | 34 (21.5%) | 0.199* |

| 25–44 | 101 (35.3%) | 42 (32.8%) | 59 (37.3%) | ||

| 45–64 | 62 (21.7%) | 23 (18.0%) | 39 (24.7%) | ||

| ≥ 65 | 58 (20.3%) | 32 (25.0%) | 26 (16.5%) | ||

| Concern about contracting COVID-19 | In daily life | ||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 6.0 (3.0, 8.0) | 8.0 (5.0, 9.0) | 5.0 (2.0, 8.0) | <0.01† | |

| During an ED visit | |||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 7.0 (4.0, 10.0) | 9.0 (7.0, 10.0) | 5.0 (2.0, 8.0) | <0.01† | |

| Gender | Female | 138 (48.3%) | 76 (59.4%) | 62 (39.2%) | <0.01* |

| Chronic conditions | Lung disease | 22 (7.7%) | 15 (11.7%) | 7 (4.4%) | 0.026* |

| Cardiovascular disease | 91 (31.8%) | 43 (33.6%) | 48 (30.4%) | 0.610* | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 13 (4.5%) | 7 (5.5%) | 6 (3.8%) | 0.574* | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 32 (11.2%) | 13 (10.2%) | 19 (12.0%) | 0.707* | |

| Malignancy/haematological disease | 54 (18.9%) | 24 (18.8%) | 30 (19.0%) | 1.000* | |

| Gastrointestinal/liver disease | 5 (1.7%) | 1 (0.8%) | 4 (2.5%) | 0.384‡ | |

| Neurological disease | 34 (11.9%) | 15 (11.7%) | 19 (12.0%) | 1.000* | |

| Psychiatric disease | 38 (13.3%) | 15 (11.7%) | 23 (14.6%) | 0.491* | |

| Other diseases | 125 (43.7%) | 57 (44.5%) | 68 (43.0%) | 0.812* | |

| Marital status | Single, never married | 96 (33.6%) | 44 (34.4%) | 52 (32.9%) | 0.411* |

| Married | 165 (57.7%) | 76 (59.4%) | 89 (56.3%) | ||

| Widowed/divorced | 25 (8.7%) | 8 (6.3%) | 17 (10.8%) | ||

| Household composition | Lives alone | 38 (13.3%) | 14 (10.9%) | 24 (15.2%) | 0.301* |

| Lives with other people | 248 (86.7%) | 114 (89.1%) | 134 (84.8%) | ||

| Level of education | Up to high school | 101 (35.3%) | 38 (29.7%) | 63 (39.9%) | 0.082* |

| University | 185 (64.7%) | 90 (70.3%) | 95 (60.1%) | ||

| Guarantor | Insured | 273 (95.5%) | 119 (93.0%) | 154 (97.5%) | 0.088* |

| Self-payer | 13 (4.5%) | 9 (7.0%) | 4 (2.5%) | ||

| Deceased | Yes§ | 10 (3.5%) | 5 (3.9%) | 5 (3.2%) | 0.757‡ |

*Pearson’s χ2 test.

†Independent samples t-test.

‡Fisher’s exact test.

§At the time of the survey, the patient was deceased and next of kin was surveyed per protocol.

ED, emergency department.

No statistically significant difference has been noted between avoiders and non-avoiders in terms of chronic conditions such as cardiovascular diseases and chronic kidney diseases among others (p>0.05). However, a greater percentage of patients who avoided the ED completely or delayed care were those with chronic lung disease (11.7% (15/128) vs 4.4% (7/158) in non-avoiders, p=0.026). Furthermore, 3.5% (10/286) of the patients were deceased at the time of the survey and the next of kin was surveyed per protocol. No statistically significant difference was reported between deceased patients who avoided ED visits and those who did not (p=0.757).

Variables associated with ED avoidance

Table 2 documents the results of the backward stepwise multivariate logistic regression analyses of the variables associated with avoidance of ED visits. Gender, concern about contracting COVID-19 during an ED visit, education and underlying lung disease were found to be independent variables associated with avoidance of ED visits. In particular, male respondents were significantly less likely than female respondents to avoid or delay ED visits (adjusted OR (aOR), 0.53; 95% CI 0.312 to 0.887, p=0.016). Moreover, those who were concerned about contracting COVID-19 during an ED visit were more likely to avoid the ED (aOR, 1.31; 95% CI 1.199 to 1.435, p<0.001). Patients with a university education were more likely to avoid ED visits compared with those with a lower level of education (aOR, 1.76; 95% CI 1.004 to 3.084, p=0.048). Finally, patients with underlying lung disease were significantly more likely to avoid the ED (aOR, 3.39; 95% CI 1.134 to 10.122, p=0.029) (the full model is available in online supplemental appendix 2). The area under the curve was found to be 0.77, which indicates a good fit for the model.

Table 2.

Stepwise (backward) multivariate logistic regression of variables associated with ED avoidance

| Variables (*reference) | Adjusted OR | 95% CI for adjusted OR | P value | |

| Stepwise model p<0.001 | Concern about contracting COVID-19 in ED visit | 1.312 | (*1.199 to 1.435) | <0.001 |

| Gender (*female) | 0.526 | (*0.312 to 0.887) | 0.016 | |

| Education (*up to high school) | 1.760 | (*1.004 to 3.084) | 0.048 | |

| Underlying lung disease (*none) | 3.388 | (*1.134 to 10.122) | 0.029 | |

| Constant | 0.113 | <0.001 |

*Entry 0.05, removal 0.10.

ED, emergency department.

bmjopen-2023-072117supp002.pdf (100.4KB, pdf)

Variables included in the model: concern about contracting COVID-19 in daily life (continuous variable, scale 0–10); concern about contracting COVID-19 during an ED visit (continuous variable, scale 0–10); age (ref: 18–24 years); gender (ref: female); marital status (ref: single, never married); household composition (ref: lives alone); education (ref: up to high school); underlying lung disease (ref: no).

Reasons for avoidance, healthcare alternatives and perceived impact on care

Table 3 illustrates the reasons for avoidance of ED visits among the patients who completely avoided visiting the ED for their acute complaints along with the healthcare alternatives adopted. Among the 56 avoiders, 89.3% (50/56) stated that the main reason behind their ED avoidance was their fear of contracting COVID-19 in the ED and 7.1% (4/56) were concerned about overwhelming the hospitals. Most of the ED avoiders (83.9% (47/56)) sought other means of medical attention for their acute complaints, such as messaging or calling a doctor (46.4% (26/56)), visiting a clinic (25.0% (14/56)) and arranging for a home visit (17.9% (10/56)). No patient reported using telehealth. Of the 56 ED avoiders, 17 (30.4%) described that the alternatives led to worse quality of care, while 36 (64.3%) did not believe that quality of care was affected.

Table 3.

Reasons for avoidance, healthcare alternatives and perceived impact on care*

| Survey response categories | No. (%) |

| Reason behind not going to the ED† | |

| Fear of contracting COVID-19 | 50 (89.3%) |

| Concerns about hospitals being overwhelmed | 4 (7.1%) |

| Concerns about hospitals receiving patients with COVID-19 | 4 (7.1%) |

| Other reasons | 4 (7.1%) |

| Alternatives sought for acute complaints† | |

| None, postponed seeking medical care | 9 (16.1%) |

| Messaged or called a doctor | 26 (46.4%) |

| Arranged for a home visit | 10 (17.9%) |

| Visited a clinic | 14 (25.0%) |

| Used telehealth | 0 (0.0%) |

| Other | 8 (14.3%) |

| Impact on care | |

| Believed that the alternatives sought yielded better quality of care | 3 (5.4%) |

| Believed that the alternatives sought yielded worse quality of care | 17 (30.4%) |

| Alternatives sought had no impact on quality of care | 36 (64.3%) |

*In those who had acute symptoms and did not visit the ED (n=56).

†Multiple answers were allowed.

ED, emergency department.

Discussion

Our study assessed ED avoidance of frequent ED users during the COVID-19 pandemic and factors associated with ED avoidance. In patients with historically high ED utilisation behaviour, ED avoidance during COVID-19 was common, especially among female respondents, those with lung disease, those with university education and those who reported fear of contracting COVID-19 in the ED. In those who avoided the ED for acute care needs, the majority sought care through messaging or calling their primary care practitioner. Outpatient clinic visits, and home visits were also reported alternatives for ED care. Of those who avoided ED utilisation, 30.4% reported worse care.

Although several studies have explored changes in ED utilisation patterns during COVID-19 using secondary data, few have looked at factors associated with these changes. Lopes et al examined the relationship between perception of COVID-19 risk, confidence in health services and avoidance of ED visits.2 Their study however did not survey responders on reasons behind ED avoidance, nor was there an exploration of alternative healthcare access points in avoiders. Similarly, Czeisler et al surveyed adults on overall healthcare utilisation during the COVID-19 pandemic without diving into reasons for avoidance.3 4 Our study is unique in focusing on a segment of patients with high baseline utilisation of ED services, exploring changes in their ED utilisation behaviour as well as reasons behind reported changes.

In our study, 45% of patients reported ED avoidance during the COVID-19 pandemic. This figure is significantly higher than the 12.0% and 10.1% reported in nationwide web-based cross-sectional studies in the USA and Australia, respectively.3 4 Demographically, our surveyed population included frequent ED users who had a significantly higher rate of having at least one underlying comorbidity compared with the other studies (89.1%, vs 49% and 47.3% in the US and Australian studies, respectively).3 4 Prior studies have linked avoidant behaviour to presence of comorbidities, where fear of contracting COVID and its impact on health may be more pronounced. This could explain the higher rate of ED avoidance in our study.

Female gender, concern about contracting COVID-19 during an ED visit, university education and having lung disease were found to be independent variables associated with decreased ED visits in our study. Fear of contracting COVID-19 and having underlying comorbidities were found to be associated with avoidant behaviour in other studies,1 11 however—contrary to other studies—our study did not find an association with age and insurance status. Similarly, while male gender was associated with avoidant behaviour in other studies, this was not the case in our study where female gender was found to be associated with ED avoidance.4 15 Having underlying medical comorbidities—specifically lung disease in our study—is a consistent finding across studies and could be attributable to these patients’ awareness of their increased risk of disease progression with COVID-19 and their perception of the ED as a place of increased exposure.

In agreement with the above findings, the majority (89.3%) of patients who completely avoided the ED during the pandemic despite having acute symptoms reported that fear of contracting COVID-19 in the ED was the major reason behind ED avoidance. During the time of the study, Lebanon was emerging from its toughest COVID-19 surge since the start of the pandemic, reaching peak positivity rates of 22.8% in January 2021 and a peak mortality rate of 21 confirmed deaths per million people on 6 February 2021. This may have contributed to our findings. Interestingly, concern about hospitals being overwhelmed—a reason often cited in the lay press—was reported as a reason among only 7.1% of complete avoiders.

Our study explored alternative healthcare services sought by patients who had acute symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic and avoided the ED. In this group, patients mostly relied on informal ways of seeking acute medical care including messaging or calling physicians on their private numbers (46.4%). Arranging for home visits (17.9%) and resorting to clinic visits (25%) were also reported to a lesser extent. Contrary to other countries where telehealth was leveraged during COVID-19, with some countries reporting 110% increase in usage in primary care settings,2 no patients in our study reported using this modality for acute care symptoms. Telemedicine, in its current format, has not been a plausible alternative for low-income and middle-income countries like Lebanon that may lack the necessary infrastructure, resources and technical expertise to integrate telehealth services widely across their health sector. Additional barriers include lack of clear medical and legal standards for telemedical consultations as well as lack of recognition by third party payers within the existing reimbursement structures.

In patients who had acute symptoms but avoided ED care in our study, the majority felt that this had no impact on the quality of the care they received (64.3%). However, 30.4% reported that the alternatives yielded worse care. A deeper dive into what patients perceived as worse care was not included in this study. The percentage of frequent ED users who were called and were found to be deceased was not statistically significantly different between avoiders and non-avoiders. Further exploration of the impact of avoidant behaviour during the pandemic on health outcomes is required to better understand the link between avoidant behaviour and excess death.

In patients with historically high ED utilisation behaviour, ED avoidance during COVID-19 was common, especially among women, those with lung disease, responders with university education and those who reported fear of contracting COVID-19 in the ED. While some patients resorted to alternative care routes, with most relying on messaging/calling their doctors, telemedicine was still underused in our setting.

As healthcare systems re-examine their preparedness plans for future surges in novel communicable diseases, strategies to address ED avoidance behaviour, especially in at-risk groups, will be essential to meeting the acute care needs of patients. These may include exploring public messaging campaigns that highlight safety precautions in the ED and aim to build trust in safety measures within the healthcare system during surges of communicable diseases. Furthermore, addressing infrastructure barriers to telehealth services is an important aspect of pandemic preparedness for low-income and low-income to middle-income countries in the future.

This study has some limitations. First, given the survey methodology, response bias may have influenced the results. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the study hinders the ability to address causality. In addition, this was a single-centre study conducted in a tertiary care centre ED in Beirut, limiting its generalisability to the population at large. Despite our efforts to reach all of the eligible subjects, we achieved a response rate of 62.6%, which may have introduced sampling or non-response bias. Furthermore, proxy responses may have introduced additional biases related to their own perceptions and attitudes. Proxy responses, however, only accounted for 16% (47/286) of total responses. Those who did not respond may have different characteristics than those who did. In addition, we performed multiple analyses and thereby ORs might have been overestimated. Finally, patients included in our study were frequent ED users. While this helped target a subgroup that historically resorted to the ED for some of their acute care needs, it limited generalisability to the general population.

Conclusion

In frequent ED users, variables associated with ED avoidance during COVID were female gender, those with lung disease, university education level and those who reported fear of contracting COVID-19 in the ED. While some patients resorted to alternative care routes, telemedicine was still underused in our setting. Developing strategies to reduce ED avoidance, especially in high-risk groups, may be warranted during pandemics.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: DM, CEH, OM and EH contributed to the concept and design. DM, CEH and AER acquired the data. DM, CEH and AM contributed to the analysis of the results. EH accepts full responsibility for the work and the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results, and drafting and critical revision of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at the American University of Beirut under the ID number SBS-2020-0214.

References

- 1.Lazzerini M, Barbi E, Apicella A, et al. Delayed access or provision of care in Italy resulting from fear of COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2020;4:e10–1. 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30108-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lopes S, Soares P, Gama A, et al. Association between perception of COVID-19 risk, confidence in health services and avoidance of emergency Department visits: results from a community-based survey in Portugal. BMJ Open 2022;12:e058600. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-058600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Czeisler MÉ, Marynak K, Clarke KEN, et al. Delay or avoidance of medical care because of COVID-19-related concerns - United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1250–7. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6936a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Czeisler MÉ, Kennedy JL, Wiley JF, et al. Delay or avoidance of routine, urgent and emergency medical care due to concerns about COVID-19 in a region with low COVID-19 prevalence: Victoria, Australia. Respirology 2021;26:707–12. 10.1111/resp.14094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woolf SH, Chapman DA, Sabo RT, et al. Excess deaths from COVID-19 and other causes, March-April 2020. JAMA 2020;324:1562–4. 10.1001/jama.2020.19545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahmassani D, Tamim H, Makki M, et al. The impact of COVID-19 Lockdown measures on ED visits in Lebanon. Am J Emerg Med 2021;46:634–9. 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.11.067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghaderi H, Stowell JR, Akhter M, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on emergency Department visits: a regional case study of Informatics challenges and opportunities. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2021;2021:496–505. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alharthi S, Al-Moteri M, Plummer V, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on the service of emergency Department. Healthcare (Basel) 2021;9:1295. 10.3390/healthcare9101295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwok ESH, Clapham G, Calder-Sprackman S. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on emergency Department visits at a Canadian academic tertiary care center. West J Emerg Med 2021;22:851–9. 10.5811/westjem.2021.2.49626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwarz V, Mahfoud F, Lauder L, et al. Decline of emergency admissions for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events after the outbreak of COVID-19. Clin Res Cardiol 2020;109:1500–6. 10.1007/s00392-020-01688-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sung HK, Paik JH, Lee YJ, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on emergency care utilization in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a nationwide population-based study. J Korean Med Sci 2021;36:e111. 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krieg C, Hudon C, Chouinard M-C, et al. Individual predictors of frequent emergency Department use: a Scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:594. 10.1186/s12913-016-1852-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soril LJJ, Leggett LE, Lorenzetti DL, et al. Characteristics of frequent users of the emergency Department in the general adult population: A systematic review of international Healthcare systems. Health Policy 2016;120:452–61. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilbert T, Bosquet A, Thomas-Antérion C, et al. Assessing capacity to consent for research in cognitively impaired older patients. Clin Interv Aging 2017;12:1553–63. 10.2147/CIA.S141905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pradeepa R, Rajalakshmi R, Mohan V. Use of Telemedicine Technologies in diabetes prevention and control in resource-constrained settings: lessons learned from emerging economies. Diabetes Technol Ther 2019;21:S29–216. 10.1089/dia.2019.0038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2023-072117supp001.pdf (3.3MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-072117supp002.pdf (100.4KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.