Abstract

Background

Existing evidence on the role of community health workers (CHWs) in primary healthcare originates primarily from the United States, Canada and Australia, and from low- and middle-income countries. Little is known about the role of CHWs in primary healthcare in European countries. This scoping review aimed to contribute to filling this gap by providing an overview of literature reporting on the involvement of CHWs in primary healthcare in WHO-EU countries since 2001 with a focus on the role, training, recruitment and remuneration.

Methods

This systematic scoping review followed the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses, extension for Scoping Reviews. All published peer-reviewed literature indexed in PubMed, Web of Science, and Embase databases from Jan 2001 to Feb 2023 were reviewed for inclusion. Included studies were screened on title, abstract and full text according to predetermined eligibility criteria. Studies were included if they were conducted in the WHO-EU region and provided information regarding the role, training, recruitment or remuneration of CHWs.

Results

Forty studies were included in this review, originating from eight countries. The involvement of CHWs in the WHO-EU regions was usually project-based, except in the United Kingdom. A substantial amount of literature with variability in the terminology used to describe CHWs, the areas of involvement, recruitment, training, and remuneration strategies was found. The included studies reported a trend towards recruitment from within the communities with some form of training and payment of CHWs. A salient finding was the social embeddedness of CHWs in the communities they served. Their roles can be classified into one or a combination of the following: educational; navigational and supportive.

Conclusion

Future research projects involving CHWs should detail their involvement and elaborate on CHWs’ role, training and recruitment procedures. In addition, further research on CHW programmes in the WHO-EU region is necessary to prepare for their integration into the broader national health systems.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12939-023-01944-0.

Keywords: Community health workers, Primary healthcare, WHO-EU region

Introduction

The Alma-Ata declaration of 1978 explicitly established health as a human right within the global health agenda, and stressed primary healthcare (PHC) as a critical mechanism for achieving Health for All [1]. Since Alma-Ata, community health worker (CHW) programmes (worldwide) have been promoted to boost health efforts within community settings [2]. CHWs who are often members of the community they serve, possess a unique understanding of the local context, including barriers and facilitators to access PHC. The American Public Health Association (APHA) defines CHWs as:

“… a frontline public health worker who is a trusted member of and/or has an unusually close understanding of the community served. This trusting relationship enables the worker to serve as a liaison/link/intermediary between health/social services and the community to facilitate access to services and improve the quality and cultural competence of service delivery.” [3].

This definition is one of several available [4]. CHW roles are often conceptualised as performing a bridging function and acting as connectors between professional health services and communities [5]. Evidence that CHWs can facilitate effective linkages to care can especially be found for individuals living in low-income or rural communities whose access to healthcare may be limited [2]. With the increasing burden of disease due to chronic conditions globally, PHC providers face an additional workload [6] which CHWs can help address as part of a PHC team [7]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, CHWs have become more recognised due to the need for more health workers on the ground [8–10]. CHWs can hence be relevant for global health as they help to achieve universal health coverage by delivering vital services to vulnerable and underserved populations [11] or by relieving pressure on PHC providers through task shifting [12].

CHW programmes exist mainly in Low-and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs), but are also implemented in many High-Income Countries (HICs) [13]. In LMICs, CHW engagement has resulted in major improvements in health priority areas, including reducing childhood undernutrition [14], improving maternal and child health [15, 16], expanding access to family planning services [17], and contributing to the control of HIV, malaria [18], and tuberculosis infections [13]. In many Middle-Income Countries, such as Brazil and India, CHWs are key members of the health team and are essential for providing PHC and health promotion [13, 19, 20]. In HICs, including the United States (US), Canada and Australia, evidence indicates that CHWs can contribute to reducing the disease burden by participating in the management of hypertension, cardiovascular risk factors, diabetes control, HIV infection, and cancer screening, particularly with populations living in socio-economically vulnerable circumstances [13, 21–24]. The United Kingdom (UK) has created a CHW position, Health Trainers, in 2004 within the National Health Service (NHS) to address health inequalities in the most disadvantaged and marginalised communities [25]. Recent systematic and scoping reviews focused on CHWs in the US, Canada, Australia or LMICs [13, 21, 26–28]. However, current literature lacks an overview of the research on CHW involvement in PHC and the role(s) they perform in the European context. Because of this, the following research question was formulated: “What is the role and what are the characteristics of CHWs involved in PHC in the WHO-EU region?”

The role, recruitment, training & remuneration of CHWs in particular are of interest because of the need to understand the mechanisms of change that lead to improved health outcomes [29]. Previous literature has pointed to the importance of CHW recruitment, training [30] and remuneration [31] in attracting, retaining and motivating CHWs. These aspects have also been included in the WHO guidelines on health policy and system support to optimize CHW programmes [32]. Accurate knowledge on the CHW’s role, recruitment, training & remuneration is of critical importance to health planners and policy makers worldwide when planning and designing (future) CHW-based interventions. This paper contributes to filling the gap in literature by describing a scoping review focusing on European CHWs, which can guide future research on CHWs and be used to inform health planners and policy makers as a key strategy in health promotion and prevention as well as a means to achieve universal health coverage in the WHO-EU region.

Methods

A scoping review method was applied to generate an overview of the literature concerning the involvement of CHWs in PHC in the WHO-EU region since 2001. Following the research question, the PCC criteria (Population, Concept and Context) [33] were used to build the search strings [see Table 1].

Table 1.

PCC criteria

| Population = Community Health Workers | Synonyms of community health workers used across Europe: auxiliary health worker; barefoot doctor; community health practitioner; health auxiliaries; community health aide; community health officer; community health volunteer; medical auxiliary; lay health worker; village health worker [14]. |

|---|---|

| Concept = Primary healthcare | This review made use of the definition of primary healthcare included in the Alma-Ata Declaration: “Primary health care is the first level of contact for individuals and the community with the national health system and addresses the main health problems in the community, providing health promotion, preventive, curative and rehabilitative services accordingly”. Primary healthcare is not to be confused with primary care. Primary care is one aspect of primary healthcare and occurs when a trained healthcare provider diagnoses or treats a patient, usually in a clinic or hospital, at the point of entry into the health system [1]. |

| Context = WHO European region | The WHO-EU region was chosen as the geographical area for this review, including the following countries: Albania, Andorra, Armenia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Monaco, Montenegro, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Republic of Moldova, Romania, Russian Federation, San Marino, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Tajikistan, The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, United Kingdom and Uzbekistan. |

The guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses, extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [34] were used to structure the results. The review protocol can be found on Open Science Framework.

Eligibility criteria

Table 2 displays the inclusion and exclusion criteria that were applied to guide the search. Studies written in any other language than English were translated using DeepL Translator (DeepL SE, Cologne, Germany).

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion | Exclusion | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | CHWs are part of the intervention or program | Study does not mention CHWs (or synonyms) |

| Concept | Intervention or program takes place in PHC (e.g. management of chronic diseases, cancer screenings, etc.) | Intervention or program is not related to PHC (e.g. specialised (cancer) care) |

| Context | Study needs to be conducted in the WHO-EU region [see Table 1] | Study takes place outside the WHO-EU region |

| Design | All study designs (quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods) | Not applicable |

| Year | Published after 2001 | Published before 2001 |

| Research question | / | Study does not provide information on at least one of the following elements: CHW role, recruitment, training or remuneration. |

Information sources

The following databases were searched for peer-reviewed literature: PubMed, Web of Science Core Collection and Embase.

Search strategy

The PRESS checklist was used to develop search strings based on the PCC criteria mentioned above [35]. Search strings used in the different databases are presented in Additional File 1. In PubMed, Boolean operators (AND/OR), truncation and the appropriate Mesh terms were used to specify the search string. In Web of Science, the concept of ‘PHC’ was left out to broaden the search because of limited hits, but the studies were screened manually for this concept. The original search strings were launched in the databases on the 8th of February 2022. The search strategy was updated on the 9th of February 2023.

Conducting the search and selection of the studies

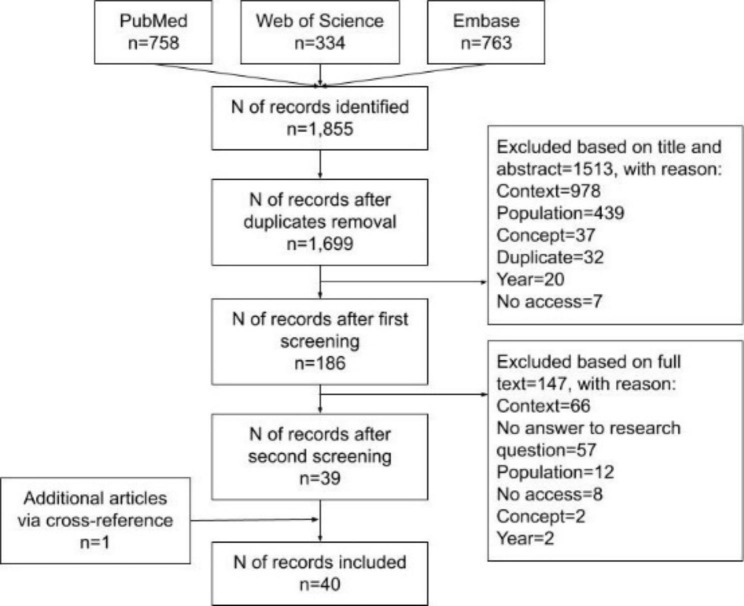

The resulting studies of each database were collated in Endnote Online. Duplicate studies were removed and two screening phases were carried out, including a first screening on title and abstract and a second screening on full-text reading of the studies that passed the first screening. In both screening phases the predetermined in- and exclusion criteria were assessed. Two researchers (TVI & IJ) performed the screening phases and independently screened all selected studies. Discrepancies were discussed until a consensus was found. Reasons for exclusion during both screening phases were registered and are shown in the PRISMA flowchart [see Fig. 1]. In addition, a hand search was performed to identify additional literature through backward citation tracking of included studies. These additional studies were added manually to Endnote and underwent the same screening process.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart

Data extraction & data items

After screening, the selected studies were transferred to an Excel template for data extraction. The following data items were extracted: first author; year of publication; country; term used to describe CHWs; target population; area of involvement; role of CHWs; tasks of CHWs; recruitment of CHWs; training of CHWs; remuneration of CHWs; primary aim of the study; conclusions concerning CHWs; and other remarks.

Quality assessment of selected studies

A quality assessment of the included studies was conducted to support the findings and specifically to provide more background information when interpreting the conclusions regarding the CHWs. Selected studies were subjected to the “innovative tools for quality assessment: integrated quality criteria for review of multiple study designs (ICROMS)”. This tool unifies, integrates and refines current quality criteria for many study designs [36]. A final quality appraisal was given (poor, moderate or strong) based on the minimum scores per design provided by the ICROMS tool [36]. Studies that scored lower than the ICROMS minimum score received a low-quality appraisal, scores equal to or slightly higher (+ 3) than the minimum score received a moderate quality appraisal, and a high-quality appraisal was given to scores at least four points above the minimum. Study designs for which there were no predefined criteria within the ICROMS tool (i.e., realist evaluation and costing study) were assessed on applicable criteria determined by the authors and given an appraisal based on how much their score deviated from their maximum attainable score [see Additional File 3]. Studies were not removed based on their quality.

Data processing

The data gathered during data extraction [see Additional File 2] was summarised in a narrative form and was further analysed in the results and discussion sections below. Statistical data of the included studies was not further analysed as this was beyond the scope of this review.

Results

Study selection

The combined search of selected databases resulted in 1,855 studies. After the removal of duplicates, 1,699 studies remained. During the first screening on title and abstract, 1,513 were excluded, largely because they did not focus on any of the included countries. In the second screening of the full text, 147 studies were excluded, also mainly due to ineligible contexts and/or not providing the required information. Another single study was included after searching the reference lists of included studies. After both screening phases, including additional cross-references, 40 studies were included for data extraction (Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

This review found a substantial amount (n = 40) of studies describing CHW roles, recruitment, training or remuneration in the WHO-EU. The publication year of the included studies ranged from 2005 to 2022 with 13 studies published after 2020. The included study designs showed significant heterogeneity, including: randomised controlled trials; cohort studies; quasi-experimental designs; and realist evaluations. Qualitative study designs were most prevalent among the included studies (n = 20). This scoping review identified evidence from the following countries: UK (n = 26); Belgium (n = 4); Ireland (n = 1); Hungary (n = 1); Spain (n = 2); Sweden (n = 2); Tajikistan (n = 1); The Netherlands (n = 2) and a multi-country study including twenty European countries (n = 1). Overall, 10% of studies were of low quality, 55% were of moderate quality and 35% were of high quality. The entire quality assessment table can be found in Additional File 3: ICROMS sheet & scoring system.

Synthesis of results

Results of the individual studies were collected using a data extraction sheet which can be found in Additional File 2: Data Extraction Table. In addition, a summary table [see Table 3] and narrative synthesis of the results can be found below, structured in eight paragraphs: terminology; target population; areas of involvement within PHC; role; recruitment; training; remuneration; and evidence regarding the effect of CHW-based programmes.

Table 3.

Summary Table of the Included Articles

| First author* | Publication year | Study design | Country | Terms used for CHWs | Area of involvement | Target population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allen-Collinson et al. [49] | 2020 | Qualitative study | UK | Health Trainers | Smoking cessation, improving diet, reducing alcohol intake, increasing healthy physical activity, and addressing mental wellbeing issues | ‘Disadvantages’ populations in general |

| Ball & Nasr [50] | 2011 | Qualitative study | UK (Northern and central England) | Health Trainers | Healthcare access for ‘hard-to-reach’ community groups | Health trainer clients proved to be an extremely ‘hard-to-reach’, deprived group |

| Begh et al. (1) [57] | 2011 | Cluster Randomised controlled trial (RCT) | UK (Birmingham) | Outreach workers | Smoking cessation | Communities where more than 10% of the population were of Pakistani and Bangladeshi origin |

| Begh et al. (2) [58] | 2011 | Qualitative study | ||||

| Brady & Keogh [48] | 2016 | Qualitative study | Ireland | Traveller community health workers | Access to health services & Asthma self-management | Traveller and Roma community |

| Brown et al. [70] | 2007 | Qualitative study | UK (London and Manchester) | Lay educator | Asthma self-management | Cultural West London and inner city & socially deprived areas in Manchester |

| Carver et al. [61] | 2012 | Qualitative study | UK (Scotland) | Outreach worker | Access to care/reduce health inequalities | These workers tend to work with clients in a natural setting by visiting the populations they serve, such as homeless or drug-using populations |

| Cook & Wills [51] | 2012 | Qualitative study | UK (London) | Health Trainers | Access to health care system & health promotion | Marginalized communities, including ‘harder-to-reach and disadvantaged’ groups |

| Furze et al. [67] | 2012 | RCT | UK | Lay workers | Angina management | Adults (aged 18 + years) with a diagnosis of angina following a positive symptom-limited exercise treadmill test in rapid access chest pain clinic; does not have any exclusion criteria. |

| Gale & Sidhu [52] | 2019 | Qualitative study | UK (Midlands) | Health Trainers | Cardiovascular disease | A deprived area called the Black Country. It has a very ethnically diverse population with significant spatial segregation between ethnic groups. |

| Gale et al. [62] | 2018 | Qualitative study | UK (Birmingham) | Lay health workers & pregnancy outreach workers (POW) | Maternity care | Each locality had different characteristics of deprivation: POW#1 and POW#2 were working in an inner city community with a large migrant population, POW#3 and POW#4 were working in a suburban area of the city, adjacent to a rural area, with a predominantly white working class population and POW#5 and POW#6 were working in an inner city community, with a more established multi-ethnic community |

| Gilworth et al. [68] | 2019 | Qualitative study | UK | Lay health workers | Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | COPD patients |

| Goelen et al. [76] | 2010 | Individual level RCT | Belgium | Community peer volunteers | Breast cancer screening | Setting: Four semirural communities in Belgium. Sample: Women aged 50–69 years who had not had a mammogram |

| Hesselink & Harting [45] | 2011 | Qualitative study | The Netherlands | Community health workers | Maternal, newborn and child health (MNCH) | Ethnic Turkish women |

| Hodgins et al. [72] | 2018 | Quasi experimental study | UK (Scotland) | Dental Health Support Workers | Dental/oral Health | All newborn children in Scotland that are referred to a dental health support worker |

| Hoens et al. [39] | 2021 | Realist evaluation | Belgium (Brussels) | Community health workers | Provide culturally competent care | Migrant families living in deprived urban areas of Brussels |

| Kennedy et al. [73] | 2005 | Qualitative study | UK | Expert Patients Programme Trainers | Management of chronic conditions, patient education | People with chronic conditions |

| Kennedy, L. [69]. | 2010 | Qualitative study | UK | Lay food and Health workers | Food and health initiatives | People from less-affluent neighbourhoods |

| Kenyon et al. [59] | 2016 | Prospective, pragmatic, individually RCT. | UK (Midlands) | POW | Maternity care | Nulliparous women under 28 weeks gestation with social risk factors |

| Kósa et al. [74] | 2020 | Quantitative analysis | Hungary | Health Mediators | Access to primary care services | Roma minority groups |

| López-Sánchez et al. [47] | 2021 | Quantitative analysis | Spain (Valencia) | Community health workers | Health literacy in the community and access to care | Persons in vulnerable situations in the city of Valencia |

| Lorente et al. [40] | 2021 | Qualitative study | 20 European countries | Community health workers | Sexual health support | Men Who Have Sex with Men |

| Martró et al. [46] | 2022 | Cross-sectional study | Spain | Community Health Worker | Hepatitis care | Pakistani adults |

| McWilliams et al. [64] | 2018 | Qualitative study | UK | Lay health workers | Cancer care | 5 separate lay groups: (1) completed cancer treatment; (2) friends/family of cancer patients; (3) cancer hospital volunteers; (4) cancer charity volunteers; and (5) members of the public |

| Netherwood [55] | 2007 | Pilot project | UK | Health Trainers | Access to care/ Reducing health inequalities | These areas also tend to have higher than average levels of unemployment, more single parent families and a higher proportion of black and minority ethnic groups, especially Pakistani, Bangladeshi and Caribbean communities |

| Rämgård & Avery [75] | 2022 | Qualitative study | Sweden | Lay health promotor | Health equity through health promotion | Low-income neighbourhood in the outskirts of Malmö, southern Sweden. |

| Roberts et al. [71] | 2012 | Costing study | UK | Lay educators | Asthma self-management | Eligible patients were adults aged 18 or over with clinician diagnosed asthma with persistent disease requiring regular preventative therapy. Participants also had evidence of unscheduled health care usage or increased medication for the treatment of an exacerbation in the 12 months prior to recruitment. |

| South et al. [63] | 2012 | Qualitative study | UK | Lay health workers | Health and well-being, breastfeeding, physical activity | A single community located in a disadvantaged urban area |

| Stone et al. [60] | 2020 | Qualitative study | UK | Telephone outreach workers | Cardiovascular risk assessment and management (= NHS health checks) | Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) communities |

| Thompson et al. [56] | 2018 | Pilot study for RCT | UK | Health Trainers | Provide support for lifestyle change, enhance mental well-being and signpost to appropriate services | People with experience of the criminal justice system. If they have served a custodial sentence, then they have to have been released for at least 2 months. The supervision period must have at least 7 months left at recruitment. |

| Vanden Bossche et al. (1) [37] | 2021 | RCT | Belgium (Ghent) | Community health workers | Psychosocial support | Eligible patients (1) had a limited social network; (2) were older than 18 years; (3) had a psychiatric history, or a precarious social context, or an uncertain residence status, or a chronic illness, or were going through a recent critical event such as bereavement or divorce, or were older than 65 years; (4) had a score of ≤ 7 on the screening questions for emotional support and ≥ 7 on the screening questions for anxiety |

| Vanden Bossche et al. (2) [38] | 2022 | Qualitative study | CHW provided support at home to vulnerable people at risk of becoming victims of fear and social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic | |||

| Verhagen et al. [41] | 2013 | Quasi experimental study | The Netherlands | Community health workers | Access to health care system | Elderly immigrants, aged 55 years and over, Living independently (alone or with others), Born in Turkey, Morocco, Moluccan Islands or descendant of Moluccan immigrants born in the Netherlands and lived in one of the Moluccan “camps” |

| Visram et al. [53] | 2015 | Qualitative study | UK | Lay health trainers | Cardiovascular risk assessment and management (= NHS health checks) | People aged 40–74 years without established disease living in socio-economic deprivation |

| White et al. [65] | 2019 | Qualitative study | UK | Lay health workers | Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) for COPD | Persons with a diagnosis of COPD; eligibility for PR treatment; and fluency in English |

| White et al. [54] | 2013 | Mixed methods | UK | Health trainers | Chronic disease management, mental health | Areas of deprivation |

| Wildman & Wildman[42] | 2021 | Cohort study | UK (Primary practices in North East England) | Community health workers | Type 2 diabetes care | UK patients aged 40 to 74 years with type 2 diabetes in a socio-economically deprived area |

| Wrede et al. [43] | 2021 | Cohort study | Sweden | Community health workers | Migrants’ mental health status | Migrants, primarily asylum seekers and newly arrived immigrants |

| Yoeli & Catan [66] | 2017 | Qualitative study | UK | Lay public health workers | Access to health care system | Anonymised urban estate in North East England, with a long-standing reputation for its socioeconomic deprivation and poor health, yet also for its strong community spirit and friendly people. |

| Yorick et al. [44] | 2021 | Cohort study | Tajikistan | Community health workers | Maternal, newborn and child health (MNCH) | Rural farming communities in Tajikistan |

*Authors are alphabetically ordered

Terms used to describe CHWs

Diverse terminology was used to describe the CHWs in the included studies. CHW as a term was used in twelve studies [37–48], and UK studies mainly referred to CHWs as (lay) health trainers [49–56]. Other studies referred to outreach workers [57–62], lay (public) (health) workers [62–69], lay educators [70, 71], dental health support worker [72], expert patient programme trainers [73], health mediators [74], lay health promotor [75] and community peer volunteers [76]. However, for the sake of readability, this paper will continue to use CHWs as an umbrella term that encompasses all these terms.

Target populations

The interventions in the included studies targeted diverse populations: ‘hard-to-reach’, disadvantaged, underserved, deprived, or low-income areas or groups [39, 47, 49–53, 55, 60–63, 65, 66, 69, 70, 75]; Bangladeshi and Pakistani men [46, 57, 58]; Roma groups [48, 74]; (elderly) immigrants [41, 43, 45]; people with chronic conditions [73]; nulliparous pregnant women [59]; people living with diagnosed asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [65, 68, 71]; people living with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in socioeconomically deprived areas [42]; new-born children [72]; angina patients [67]; psychosocial vulnerable people [37, 38]; men who have sex with men [40]; rural (farming) communities [44, 76]; and people with experience in the criminal justice system [56].

Areas of CHW involvement

Areas of CHW involvement within PHC showed substantial variability, broadly covering the four following categories:

Access to PHC, including: healthcare access for underserved community groups in the UK [47, 50, 51, 55, 61, 75]; guiding Roma minority groups towards PHC services in Hungary [74]; CHWs improving care for elderly immigrants in the Netherlands [41]; and enabling dialogue with health professionals for people living with asthma in Ireland [48]. Improved access was facilitated through direct referral [51] or health literacy interventions by CHWs [47]. A realist evaluation showed how training of CHWs contributed to increased access to care for migrant families in deprived urban areas [39].

Management of non-communicable diseases [54, 73], including: cancer screening [64, 76]; T2DM care [42]; angina management [67]; COPD management [65, 68]; asthma self-management [70, 71]; and cardiovascular risk assessment and management [52, 53, 56, 60]. Three studies focused primarily on smoking cessation [49, 57, 58].

Psychosocial support of migrants with regards to their mental health [43], psychosocial support in disadvantaged urban areas [63] or in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic [37, 38].

Sexual and reproductive health: maternal, new-born and child health (MNCH) [44, 45]; sexual health support for men who have sex with men [40]; and maternity care [59, 62].

Other studies focused on food and health initiatives [69], hepatitis care [46] and dental health [72].

Recruitment of CHWs

Information on how CHWs were recruited was lacking in nineteen studies. The remaining 21 studies reported a trend towards locally-recruited CHWs; i.e., CHWs were recruited from within the communities [54, 66, 75]. For example, Gale & Sidhu [52] recruited health trainers from the local community because they would have greater contextual and nuanced knowledge of socio-cultural barriers within the community. Similarly, Kósa et al. [74] recruited locals through advertisements at participating general practitioners’ offices. Stone et al. [60] and Verhagen et al. [41] added a slight nuance by using a recruitment strategy under supervision by a local public health commissioner or coordinator. López-Sánchez et al. [47] worked with persons that were proposed by local associations. In the study by Kennedy et al. [73], CHWs were recruited after participation in a course, implying they were also patients with chronic conditions. The studies by Brown et al. [70] and Roberts et al. [71] reported that the CHWs involved in asthma care had to have asthma themselves or at least have a relative with asthma. Brown et al. [70] reported there were no other (educational) requirements. Hoens et al. [39] recruited ten jobseekers with migration backgrounds, also without mentioning further specifications. In the study of Vanden Bossche et al. [37], CHWs needed to be aware of the problems of people living in a vulnerable context, either through experience or background. Contrary to this, Wrede et al. [43] mentioned they were looking for CHWs with a migrant background who did have some form of healthcare education. Only White et al. [65] and Yorick et al. [44] explicitly stated inclusion criteria for recruitment, including specific skills, such as networking and communications skills.

Twelve studies included information on the sex of the CHWs [39, 40, 47, 51, 57, 58, 60, 65, 66, 68, 70, 73]. Three studies reported more male CHWs: out of 20 volunteers accepted for training, eleven were male [65, 68]; 67.9% of CHWs were men [40]; four and five male CHWs participated in the focus groups [57, 58]. Eight studies reported more female CHWs: all participating CHWs were female [66]: nine out of ten CHWs were female [60]; 164 female and 37 male CHWs [47]; 15 female and four male CHWs [73]; eight female and two male CHWs [39]; all but one were female [51]; twelve female and three male CHWs [70].

Training of CHWs

Training of CHWs was not mentioned in five studies [42, 53, 55, 72, 76], while eleven studies stated that CHWs received training but without elaborating on its content [40, 43, 48–50, 62, 63, 66, 68, 69, 73]. In the remaining 24 studies, the reported training received ranged from two days [71] up to nine months [39]. The studies by Begh et al. [57, 58] reported two weeks of training by accredited NHS trainers and the research team. CHWs in the study of Brown et al. [70] underwent a two-day residential training, followed by a six-week distance learning programme. A twelve-week training course for CHWs was provided in the study reported by López-Sánchez et al. [47]. Kósa et al. [74] reported that CHWs were trained on-the-job with several short courses during work hours. In case of bigger project funds, longer training periods were set up. Hoens et al. [39] for example, reported a nine-month training programme for CHW supported by a European social fund with courses on culturally competent care and learning of the Dutch language, followed by an internship. Yoeli & Catan [66] concluded that training could help to engage the most underserved groups. In general, CHWs received training in delivering behavioural support, medication management, general health promotion, empowering strategies and culturally specific norms. The studies of Stone et al. [60] and Verhagen et al. [41] concluded that both purposeful recruitment and training of CHWs were vital. However, this review did not find any studies linking the duration of training with the duration of deployment of CHWs in the communities.

Remuneration of CHWs

CHWs received a salary in thirteen studies [41, 44, 45, 48, 52, 54, 57, 58, 62, 67, 70, 74, 75]. Five studies worked with volunteers [37, 38, 63, 65, 76] and six studies reported a mix of paid and unpaid CHWs, often without specifying the reason for this [40, 51, 65, 66, 69, 73]. In the UK-based studies, paid CHWs were financed by the NHS [52, 66] and unpaid CHWs worked for non-profit organisations [51]. White et al. reported that the volunteer CHWs were offered payment for the research elements of their role [65]. Cook & Wills [51] noted that CHWs working voluntarily offered greater potential for engaging communities and providing practical options for health gains because of their informal status compared to CHWs employed by the NHS. Remuneration was not mentioned in the other 16 studies.

CHW role

The role of CHWs as reported in the included studies can be classified into one or a combination of the following: educational role; navigational role; and support role.

A primarily educational role was seen in the studies of Brown et al. [70], Furze et al. [67], Kennedy et al. [73], Kennedy [69], Roberts et al. [71] and Wrede et al. [43]. CHWs in Brown et al. [70] and Roberts et al. [71] had to provide consultations and follow-up meetings to improve people’s asthma self-management. CHWs in the study of Kennedy et al. [73] were responsible for weekly educational sessions on the management of chronic conditions and Kennedy [69] reported that CHWs were mainly tasked with nutrition education. In the study by Wrede et al. [43], CHWs led the mental health sessions for Swedish immigrants. The CHWs in the study of Gale et al. [62] described themselves as ‘myth-busters’.

Navigational roles were reported in the study of Ball & Nasr [50], focusing on underserved community groups. In the study of Begh et al. [58] in Pakistani and Bangladeshi communities in the UK, a navigational role was adopted at first, followed by a more educational role in the second stage of the intervention. Cook & Wills [51] also instructed CHWs to promote health services, next to providing some educational aspects. Kósa et al. [74] used CHWs to bridge the gap between the Roma community and the general practitioners. CHWs in Stone et al. [60] and Visram et al. [53] sent invitations to attend NHS appointments and referred to lifestyle services. Verhagen et al. [41] focused on culturally competent care and showed that this can improve access to the healthcare system. People living with T2DM were referred by CHWs to PHC practitioners in Wildman & Wildman [42] and CHWs in the study of Yorick et al. [44] referred children with malnutrition and diarrhoea to health facilities in Tajikistan. People living with COPD in Gilworth et al. [68] were assisted into pulmonary rehabilitation courses by CHWs who acted as patient navigators. Similarly, CHWs in the study of Goelen et al. [76] contacted eligible women to participate in breast cancer screenings.

A supporting role was reported in the study of Allen-Collinson et al. [49] where CHWs supported the community in making healthy lifestyle choices. Similarly, in the study of Vanden Bossche et al. [37], CHWs provided psychosocial support for patients from vulnerable communities to reduce the workload of PHC providers. In the study of Gale & Sidhu [52] and Thompson et al. [56], CHWs supported lifestyle, smoking cessation and weight management. Kenyon et al. [59] noted that CHWs supported mothers with newborn babies by regular home visits and referral to specialist services in the case of the presence of risk factors. Sexual health support was the main objective of CHWs in Lorente et al. [40]. In McWilliams et al. [64], support was provided to patients with cancer care. CHWs in Carver et al. [61] provided one-on-one support to patients before and after their health checks. Finally, CHWs in Gale et al. [62] provided informational and emotional support to pregnant women.

Finally, five included studies elaborated on the importance of the social embeddedness of CHWs in the communities they served, meaning the CHWs provided social support and were trusted points of contact. For example, Gale et al. [62] calls this ‘synthetic social support’. Ball & Nasr [50] reported that CHWs being a ‘person next door’ with a one-on-one approach was a critical factor in the success of their programme. CHWs viewed themselves as facilitators rather than directors and felt this was an important factor in the success of their role [50]. CHWs were also seen as friends and neighbours who are there to help the community [50]. The qualitative study by Gale & Sidhu [52] offered a nuanced explanation for intervention success in engaging communities by identifying three steps. First, CHWs should be critical insiders, meaning that they understand the (negative) effects of lifestyle behaviour in the community, e.g., in terms of nutrition. Secondly, CHWs should try to make small but sustainable changes to the community’s lifestyle. Third, CHWs should try to become accessible role models [52]. The study by Kennedy [69] identified CHWs as ‘culturally acceptable vehicles for change’ and highlighted that CHWs offered an alternative to sole professional interventions. South et al. [63] also concluded that social relationships are core to understanding CHW programmes.

Evidence regarding the effect of CHW-based programmes

Ten studies stated that CHW-based programmes proved feasible and acceptable, without reporting on the effects of the interventions [46, 53, 57, 58, 61, 64, 70, 74, 76]. Six of the included studies reported positive effects of CHW-based programmes [37, 42–44, 59, 67], including significant improvements in self-rated psychosocial health [37], less depressive symptoms in pregnant women [59], improved HbA1c levels [42], positive changes in mental health status [43], reduced anxiety and depression in people with angina [67] and improved knowledge, attitudes and practices that result in better nutrition [44]. Contrary, White et al. [54] reported they found no evidence that CHWs impacted health inequalities. Only one study mentioned the costs of CHW programmes: Roberts et al. [71] reported a lack of significant differences in the cost of training and healthcare delivery between nurses and CHWs in the UK. The generalisability of these effects could be higher given the variety of interventions across countries and the observed quality of the studies [see Additional File 3].

Discussion

This scoping review provides the first overview of CHW involvement in PHC in the WHO-EU region and can be used to learn from past efforts, identify knowledge gaps and develop new research questions regarding the involvement of CHWs in the WHO-EU region.

The involvement of CHWs in the WHO-EU region was found in published literature spanning the last few decades, with 13 out of 40 studies published since 2020, indicating a growing interest for CHW-based programmes in European health care systems. CHW involvement was usually project-based - except in the UK - and the role, recruitment, training and remuneration of CHWs varied from context to context. The information gathered in this scoping review originated mainly from studies of moderate quality. The main explanation for this can be found in poor descriptions of managing bias in the outcome and reporting of the included studies [see Additional File 3]. In line with O’Brien et al. [77], this review recommends more consistent reporting of future research on CHW roles, recruitment, training, remuneration and other elements [78] (accreditation, equipment, supervision, and community involvement among others) of the CHW Assessment and Improvement Matrix (AIM) [78] to allow to better interpret CHW-based programme findings.

This review showed that in line with existing literature [5, 79–81], CHWs and the interventions they are engaged in are best seen as bridging the communities and the national or local health system. Within this bridging element the roles and characteristics of the CHWs have been adapted to the local context. This review indicates that the role of CHWs is often a combination of educational, navigational and supporting aspects, in line with the findings of a scoping review on CHW support for T2DM self-management in South Africa which found education, support and advocacy to constitute their main roles [82]. The most important CHW aspect seemed to be the social embeddedness through which trustful relationships between CHWs and their clients are created. A recent realist evaluation reported this relationship to be rooted in recognition, equality and reciprocity [38]. In line with the literature from high-income countries [83], this review found that CHWs in the WHO-EU region commonly provide services related to non-communicable diseases. Because of this, the authors of this review believe that CHWs can be an added value to reach the objectives within the Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of NCDs in the WHO-EU Region [84], making this a political priority in the region. However, CHWs are not included in the Action Plan and to our knowledge WHO-EU has not yet released any official statements regarding CHWs in the region. They did already publish some exemplary articles on CHW involvement in Albania, Azerbaijan, Turkey and Ukraine [85]. Presumably, CHWs could have a larger scope in these poorer countries and shift their focus towards disadvantaged populations in the richer countries of the region. Previous studies have identified structural and systematic barriers to access for low socioeconomic groups, such as costs, time pressure, and linguistic and cultural differences [86]. This review supports the existing evidence that CHWs can help improve access to PHC by circumventing these barriers.

Two tensions concerning the role of CHWs were also addressed in Hodgins et al. [87]: the lay vs. professional aspect of CHWs; and the CHW as service provider or as service promotor. In LMICs, the study by Hodgins et al. [87] reported that, over time, a tendency to add new functions to the CHWs’ scope of practice was reported, resulting in deprioritising certain activities, in particular promotion services. Even if governments and programme designers intend CHWs to focus primarily on health education or health promotion, communities tend to value clinical services more [87]. Therefore, CHWs tend to prioritize what their beneficiaries value most.

Recruitment strategies of CHWs were only described in more recent studies, which could be related to the increasing attention to implementation research in recent years. Most studies generally reported recruitment strategies that embody ‘insider knowledge’ [66]. This is similar to what has been described as ‘indigenous knowledge’ of Brazilian CHWs to overcome contextual challenges [88]. Locally recruited CHWs possess embodied knowledge of their communities by being part of the community. This intuitive aspect is also captured in the WHO definition of CHWs [89]. Obviously, people coming from within the community need less training than ‘outsiders’ or ‘incomers’ with limited community knowledge. For example, participating in the Expert Patient Programme was the only condition for recruitment in the study of Kennedy et al. [73]. Besides training-related aspects, being an locally recruited is also important when building trustworthy relationships with the community.

CHW training differed among studies and aimed to help CHWs gain skills in activities directly related to their role. This scoping review showed that the amount and type of training required should be considered in view of the local healthcare system, CHWs’ prior capacities, and the roles that CHWs are intended to take on. Training CHWs is an essential part of CHW programmes [90], but there is no consensus in the literature regarding the extent or form of the training, whether in preparation for or on-the-job training. In LMICs, training increased CHW motivation, job satisfaction, and performance, but there was no direct evidence that different aspects of training or different training approaches affected CHW performance [79]. Across health occupations there has been an evolution towards higher educational requirements and longer training periods [90]. As the number of highly trained healthcare staff grows, it is projected that this professionalisation will also affect CHWs, leaving fewer and less tasks to be performed by CHWs or requiring more professionalisation of CHWs themselves. The question arises as to how the bridging role of CHWs can be maintained. On the other hand, CHWs can relieve pressure of overburdened healthcare providers through task-shifting [12].

CHWs’ remuneration is strongly linked to their accreditation and national recognition. A US study suggested that equitable compensation for their services is an important step towards CHWs’ integration within the broader health system of the country [91]. However, compensating CHWs for certain tasks also raises the question of where the CHW role ends and another health career begins, which needs to be discussed with a view to task-shifting [92]. Paid work can push CHWs towards tasks they are paid for, and White et al. (2019) in their paper opined that the community basis and the cooperative nature of CHW interventions could be undermined if CHWs are remunerated. On the other hand, non-monetary incentives such as trust, respect and recognition can play an equally important role in the motivation and performance of CHWs. Nevertheless, in LMICs, the relevance of (monetary) incentives is of great importance in the planning of CHW programmes [93, 94]. The more recent studies included in this review align with the 2018 WHO guideline that CHWs should receive a financial package corresponding to their job demands, complexity, number of hours worked, training, and the roles they undertake, supported by a written agreement [31]. There is also a global push towards CHW remuneration, led by the Community Health Impact Coalition [95], and it could be valuable to compare the effectiveness of non-monetary and monetary incentives for CHWs in a European context.

This review only included articles originating from eight countries, reaffirming the initial point that there is limited evidence in the WHO-EU context and more research is needed. As a consequence of their national CHW program, 26 studies included in this review were UK-based. The NHS set up job descriptions, competencies, and an accreditation system for CHWs. However, the implementation varied across the nation and CHWs have not been recognised as a coherent occupational group [96]. Consequently, retention of CHWs has been problematic due to low pay, job insecurity, job intensity and lack of recognition within the health system. Consequently, many CHWs have moved from the NHS to non-governmental organisations [52]. Future CHW programmes can learn from the UK experience and learn from its successes and failures, knowing that integrating CHWs within the existing health care systems is a complex matter and cannot be done in silos. Health strategies (involving CHWs) must also be integrated into broader programmes focussing on poverty reduction and sustainable development [97], with a long-term vision and sustainable funding [98].

In addition, European CHW programmes can learn from lessons of CHW programmes in LMICs through reverse or reciprocal innovation [99], as shown by a pilot project in North Wales which tried to implement and learn from Brazil’s CHW strategy [100]. In 2018, WHO also published evidence-based global guidelines for health policy and systems support to optimise CHW programmes worldwide, based however on low and very low certainty of evidence [32]. Key considerations for implementation included the need to define the role of CHWs in relation to other health workers and to plan for the entire health workforce rather than specific occupational groups; to appropriately integrate CHW programmes into the existing health system; and to ensure internal coherence and consistency across different policies and programmes affecting CHWs [32].

Limitations

The lack of a unified terminology posed difficulties for this scoping study, and nomenclature remains a fundamental challenge for studies aiming to comprehensively review CHWs programmes [80]. This review only included published studies and did not include grey literature, potentially giving rise to a publication bias. This explains why programs such as in Belgium [101] and Westminster [102] are not part of this review. A remark can be made regarding the paucity of coverage of COVID-19-related CHW-based programmes in this review. One possible explanation could be that many of these programmes are ongoing and/or the corresponding studies are yet to be published in scientific journals. This review was also limited to a few aspects of importance to CHW programmes as described in the WHO guideline for CHW programmes [32] and CHW AIM framework [78]. Finally, although literature published in a language other than English was translated into English, this did not rule out a language bias because of the English search strategy. In spite of the growing interest in CHWs stated before, this review did not find literature for 45 countries in the WHO-EU region. This is possibly a consequence of the combined language and publication bias.

Conclusion

This scoping review indicated that CHWs provide a wide range of health-related services in the WHO-EU region, albeit in a limited number of countries. This review found substantial variability in recruitment, training and remuneration. In general, most studies reported a trend in favour of locally recruited CHWs, with some form of training and payment in most of the included studies. Their roles were classified into one or a combination of the following: educational, navigational and supporting roles. The most important aspect of CHW-based programmes was the social embeddedness in the communities they served. Further research on CHW programmes in the WHO-EU region is necessary to prepare for their integration into broader national health systems.

Recommendations

Based on the topics addressed in this review, some recommendations can be made to inform future research and policymaking. First, future research projects involving CHWs should mention their involvement and elaborate on the role, training and recruitment of CHWs to obtain a full picture of the programme. In addition, other elements of the CHW AIM framework [78] (accreditation, equipment, supervision, and community involvement among others) need to be taken into account to enable evaluation of CHW involvement. Second, there is a need for a more rigid evaluation of the evidence stated in this scoping review. Systematic reviews or realist syntheses on the role of CHWs in the WHO-EU region can respond to this research need. Third, there is limited high-quality evidence regarding CHWs’ ability to improve access to PHC for marginalised, vulnerable and underserved populations in the WHO-EU region, especially when compared to the amount of evidence from other high-income countries, such as the US. This indicates the need for rigorous studies and program evaluations. Finally, the cost and cost-effectiveness of CHW interventions, CHW involvement and integration in PHC settings in the WHO-EU region is still unknown, pointing to the need for health economics analysis (or similar). At policy level, it might be time to move from project-based CHW-based programmes to building meaningful long-term partnerships between CHWs, communities and policy-makers backed by sustainable funding [28, 98]. Therefore, national governments and the health sector should clearly commit to CHW-based programmes. Governments in the WHO-EU region should better recognize and support sustainable CHW-based programmes [40] as e.g. shown in the UK.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Additional File 1: Search Strings per database

Additional File 2: Data Extraction Table

Additional File 3: ICROMS sheet & scoring system

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

List of Abbreviations

- AIM

Assessment and Improvement Matrix

- APHA

American Public Health Association

- CHW

Community Health Workers

- HICs

High-Income Countries

- ICROMS

Integrated Quality Criteria for Review of Multiple Study Designs

- LMICs

Low- and Middle-Income Countries

- NHS

National Health Service

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PRISMA-ScR

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses, extension for Scoping Reviews

- UK

United Kingdom

- US

United States

- WHO

World Health Organisation

- WHO-EU

WHO European Office

Authors’ contributions

TVI was responsible for study rationale and design, literature search, literature selection, quality assessment of studies, data extraction, writing the manuscript and adapting the manuscript. IJ was responsible for the screening phases and the literature selection. PD, DV & PD were responsible for study rationale and feedback and input throughout the process. SW & CM were responsible for reviewing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

TVI is contracted by Ghent University and is supported by the Scientific Research Foundation-Flanders (FWO-SBO fellowship: S006123N). The funders did not play a role in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. Therefore, they accept no responsibility for the content.

Data Availability

The dataset(s) supporting the conclusions of this review is(are) included within the article (and its additional file(s)).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Alma-Ata. International conference on primary health care - Alma-Ata, USSR 6–12 September 1978. Declaration of Alma-Ata 1978. [PubMed]

- 2.Agarwal S, Sripad P, Johnson C, et al. A conceptual framework for measuring community health workforce performance within primary health care systems. Hum Resour Health. 2019;17:1–20. doi: 10.1186/s12960-019-0422-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Public Health Association., Community Health Workers, https://www.apha.org/apha-communities/member-sections/community-health-workers (accessed 23 February 2023).

- 4.Olaniran A, Smith H, Unkels R, et al. Who is a community health worker? – a systematic review of definitions. Glob Health Action. 2017;10:1272223. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2017.1272223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.LeBan K, Kok M, Perry HB. Community health workers at the dawn of a new era: 9. CHWs’ relationships with the health system and communities. Health Res Policy Syst. 2021;19:1–19. doi: 10.1186/s12961-021-00756-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yarnall KSH, Østbye T, Krause KM et al. Family physicians as team leaders: ‘Time’ to share the care. Prev Chronic Dis; 6. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Ghorob A, Bodenheimer T. Sharing the care to improve access to primary care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1955–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1202775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perry HB, Hodgins S. Health for the people: past, current, and future contributions of National Community Health Worker Programs to Achieving Global Health Goals. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2021;9:1–9. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-20-00459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ballard M, Bancroft E, Nesbit J, et al. Prioritising the role of community health workers in the COVID-19 response. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5:e002550. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valeriani G, Sarajlic Vukovic I, Bersani FS, et al. Tackling ethnic Health Disparities through Community Health Worker Programs: a scoping review on their utilization during the COVID-19 outbreak. Popul Health Manag. 2022;25:517–26. doi: 10.1089/pop.2021.0364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Odugleh-Kolev A, Parrish-Sprowl J. Universal health coverage and community engagement. Bull World Health Organ. 2018;96:660–1. doi: 10.2471/BLT.17.202382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dick K, Schneider JE, Scheibling C et al. The critical role of Community Health Workers (CHW) and Health Navigators (HN) in Access to Care for Individuals with Sickle Cell Anemia.

- 13.Perry B, Zulliger R, Rogers MM. Community health workers in low-, middle-, and high-income countries: an overview of their history, recent evolution, and current effectiveness. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:399–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alvarez Moran JL, Alé FG, Rogers E, et al. Quality of care for treatment of uncomplicated severe acute malnutrition delivered by community health workers in a rural area of Mali. Matern Child Nutr. 2018;14:e12449. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nkonki L, Tugendhaft A, Hofman K. A systematic review of economic evaluations of CHW interventions aimed at improving child health outcomes. Hum Resour Health. 2017;15:19. doi: 10.1186/s12960-017-0192-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tuyisenge G, Crooks VA, Berry NS. Facilitating equitable community-level access to maternal health services: exploring the experiences of Rwanda’s community health workers. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12939-019-1065-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott VK, Gottschalk LB, Wright KQ, et al. Community Health Workers’ provision of Family Planning Services in low- and Middle-Income Countries: a systematic review of effectiveness. Stud Fam Plann. 2015;46:241–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2015.00028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oo WH, Gold L, Moore K, et al. The impact of community-delivered models of malaria control and elimination: a systematic review. Malar J. 2019;18:1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12936-019-2900-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blanchard AK, Ansari S, Rajput R, et al. Understanding the roles of community health workers in improving perinatal health equity in rural Uttar Pradesh, India: a qualitative study. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12939-021-01406-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macinko J, Harris MJ, Phil D. Brazil’s family health strategy—delivering community-based primary care in a universal health system. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2177–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1501140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Najafizada SAM, Bourgeault IL, Labonte R, et al. Community health workers in Canada and other high-income countries: a scoping review and research gaps. Can J Public Health. 2015;106:e157–64. doi: 10.17269/CJPH.106.4747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Javanparast S, Windle A, Freeman T, et al. Community health worker programs to improve healthcare access and equity: are they only relevant to low-and middle-income countries? Int J Health Policy Manag. 2018;7:943. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2018.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boulton A, Gifford H, Potaka-Osborne M. Realising whānau ora through community action: the role of Māori community health workers. Educ Health. 2009;22:188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berini CR, Bonilha HS, Simpson AN. Impact of Community Health Workers on Access to care for rural populations in the United States: a systematic review. J Community Health. 2022;47:539–53. doi: 10.1007/s10900-021-01052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris M, Haines A. The potential contribution of community health workers to improving health outcomes in UK primary care. J R Soc Med. 2012;105:330–5. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2012.120047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller NP, Ardestani FB, Dini HS, et al. Community Health Workers in Humanitarian Settings: scoping review. J Glob Health. 2020;10:1–21. doi: 10.7189/jogh.10.020602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hartzler AL, Tuzzio L, Hsu C, et al. Roles and functions of community health workers in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16:240–5. doi: 10.1370/afm.2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahmed S, Chase LE, Wagnild J, et al. Community health workers and health equity in low- and middle-income countries: systematic review and recommendations for policy and practice. Int J Equity Health. 2022;21:49. doi: 10.1186/s12939-021-01615-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dennis C-L. Peer support within a health care context: a concept analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2003;40:321–32. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7489(02)00092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Love MB, Legion V, Shim JK, et al. CHWs get credit: a 10-Year history of the First College-Credit Certificate for Community Health Workers in the United States. Health Promot Pract. 2004;5:418–28. doi: 10.1177/1524839903260142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colvin CJ, Hodgins S, Perry HB. Community health workers at the dawn of a new era: 8. Incentives and remuneration. Health Res Policy Syst. 2021;19:1–26. doi: 10.1186/s12961-021-00750-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cometto G, Ford N, Pfaffman-Zambruni J, et al. Health policy and system support to optimise community health worker programmes: an abridged WHO guideline. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e1397–404. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30482-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.The Joanna Briggs Institute. The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual 2015: methodology for JBI scoping reviews. Joanne Briggs Inst 2015; 1–24.

- 34.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM et al. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Explanation and Elaboration (PRESS E&E). Cadth 2016; 40–46. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Zingg W, Castro-Sanchez E, Secci FV, et al. Innovative tools for quality assessment: Integrated quality criteria for review of multiple study designs (ICROMS) Public Health. 2016;133:19–37. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2015.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vanden Bossche D, Lagaert S, Willems S, et al. Community health workers as a strategy to tackle psychosocial suffering due to physical distancing: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:1–16. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18063097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vanden Bossche D, Willems S, Decat P. Understanding Trustful Relationships between Community Health Workers and Vulnerable Citizens during the COVID-19 pandemic: a Realist evaluation. Int J Environ Res Public Health; 19. Epub ahead of print 2022. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph19052496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Hoens S, Smetcoren AS, Switsers L et al. Community health workers and culturally competent home care in Belgium: a realist evaluation. Health Soc Care Community 2021; 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Lorente N, Sherriff N, Panochenko O, et al. The role of Community Health Workers within the Continuum of Services for HIV, viral Hepatitis, and other STIs amongst men who have sex with men in Europe. J Community Health. 2021;46:545–56. doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00900-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Verhagen I, Steunenberg B, Ros WJ, et al. Towards culturally sensitive care for elderly immigrants! Design and development of a community based intervention programme in the Netherlands. Tijdschr Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;45:82–91. doi: 10.1007/s12439-014-0068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wildman J, Wildman JM. Evaluation of a Community Health Worker Social Prescribing Program among UK patients with type 2 diabetes. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:1–12. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.26236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wrede O, Löve J, Jonasson JM, et al. Promoting mental health in migrants: a GHQ12-evaluation of a community health program in Sweden. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10284-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yorick R, Khudonazarov F, Gall AJ, et al. Volunteer community health and agriculture workers help reduce childhood malnutrition in Tajikistan. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2021;16:137–S150. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-20-00325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hesselink AE, Harting J. Process evaluation of a multiple risk factor perinatal programme for a hard-to-reach minority group: process evaluation of a multiple risk factor perinatal programme. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67:2026–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martró E, Ouaarab H, Saludes V, et al. Pilot hepatitis C micro-elimination strategy in pakistani migrants in Catalonia through a community intervention. Liver Int. 2022;42:1751–61. doi: 10.1111/liv.15327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.López-Sánchez MP, Roig Sena FJ, Sánchez Cánovas MI, et al. Associations and community health workers: analysis and time trends over ten years of training-action. Gac Sanit. 2021;35:230–5. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2019.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brady A-M, Keogh B. An evaluation of asthma education project targeting the Traveller and Roma community. Health Educ J. 2016;75:396–408. doi: 10.1177/0017896915592655. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Allen-Collinson J, Williams R, Middleton G, et al. We have the time to listen’: community health trainers, identity work and boundaries. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2020;12:597–611. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1646317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ball L, Nasr N. A qualitative exploration of a health trainer programme in two UK primary care trusts. Perspect Public Health. 2011;131:24–31. doi: 10.1177/1757913910369089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cook T, Wills J. Engaging with marginalized communities: the experiences of London health trainers. Perspect Public Health. 2012;132:221–7. doi: 10.1177/1757913910393864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gale NK, Sidhu MS. Risk work or resilience work? A qualitative study with community health workers negotiating the tensions between biomedical and community-based forms of health promotion in the United Kingdom. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:1–19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Visram S, Carr SM, Geddes L. Can lay health trainers increase uptake of NHS health checks in hard-to-reach populations? A mixed-method pilot evaluation. J Public Health U K. 2015;37:226–33. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdu041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.White J, Woodward J, South J. Addressing inequalities in health – what is the contribution of health trainers? Perspect Public Health. 2013;133:213–20. doi: 10.1177/1757913913490853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Netherwood M. Will health trainers reduce inequalities in health? Br J Community Nurs. 2007;12:463–8. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2007.12.10.27285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thompson TP, Callaghan L, Hazeldine E, et al. Health trainer-led motivational intervention plus usual care for people under community supervision compared with usual care alone: a study protocol for a parallel-group pilot randomised controlled trial (STRENGTHEN) BMJ Open. 2018;8:e023123. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Begh RA, Aveyard P, Upton P et al. Experiences of outreach workers in promoting smoking cessation to bangladeshi and pakistani men: longitudinal qualitative evaluation. BMC Public Health; 11. Epub ahead of print 2011. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Begh RA, Aveyard P, Upton P, et al. Promoting smoking cessation in pakistani and bangladeshi men in the UK: pilot cluster randomised controlled trial of trained community outreach workers. Trials. 2011;12:1–14. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kenyon S, Jolly K, Hemming K, et al. Lay support for pregnant women with social risk: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2016;6:1–8. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stone TJ, Brangan E, Chappell A, et al. Telephone outreach by community workers to improve uptake of NHS health checks in more deprived localities and minority ethnic groups: a qualitative investigation of implementation. J Public Health U K. 2020;42:1–9. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdz063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carver H, Douglas MJ, Tomlinson JEM. The outreach worker role in an anticipatory care programme: a valuable resource for linking and supporting. Public Health. 2012;126:47–S52. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gale NK, Kenyon S, MacArthur C, et al. Synthetic social support: Theorizing lay health worker interventions. Soc Sci Med. 2018;196:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.South J, Kinsella K, Meah A. Lay perspectives on lay health worker roles, boundaries and participation within three UK community-based health promotion projects. Health Educ Res. 2012;27:656–70. doi: 10.1093/her/cys006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McWilliams L, Bellhouse S, Yorke J, et al. The acceptability and feasibility of lay-health led interventions for the prevention and early detection of cancer. Psychooncology. 2018;27:1291–7. doi: 10.1002/pon.4670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.White P, Gilworth G, Lewin S, et al. Improving uptake and completion of pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD with lay health workers: feasibility of a clinical trial. Int J COPD. 2019;14:631–43. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S188731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yoeli H, Cattan M. Insiders and incomers: how lay public health workers’ knowledge might improve public health practice. Health Soc Care Community. 2017;25:1743–51. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Furze G, Cox H, Morton V, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a lay-facilitated angina management programme. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68:2267–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05920.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gilworth G, Lewin S, Wright AJ, et al. The lay health worker–patient relationship in promoting pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) in COPD: what makes it work? Chron Respir Dis. 2019;16:147997311986932. doi: 10.1177/1479973119869329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kennedy L. Benefits arising from lay involvement in community-based public health initiatives: the experience from community nutrition. Perspect Public Health. 2010;130:165–72. doi: 10.1177/1757913910369090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brown C, Hennings J, Caress AL, et al. Lay educators in asthma self management: reflections on their training and experiences. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;68:131–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Roberts NJ, Boyd KA, Briggs AH et al. Nurse led versus lay educators support for those with asthma in primary care: a costing study. BMC Pulm Med; 12. Epub ahead of print 2012. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2466-12-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 72.Hodgins F, Sherriff A, Gnich W, et al. The effectiveness of dental health support workers at linking families with primary care dental practices: a population-wide data linkage cohort study. BMC Oral Health. 2018;18:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12903-018-0650-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kennedy A, Rogers A, Gately C. From patients to providers: prospects for self-care skills trainers in the National Health Service. Health Soc Care Community. 2005;13:431–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2005.00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kósa K, Katona C, Papp M, et al. Health mediators as members of multidisciplinary group practice: Lessons learned from a primary health care model programme in Hungary. BMC Fam Pract. 2020;21:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12875-020-1092-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rämgård M, Avery H. Lay Health Promoters Empower Neighbourhoods-Results from a community-based Research Programme in Southern Sweden. Front Public Health. 2022;10:703423. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.703423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Goelen G, De Clercq G, Hanssens S. A community peer-volunteer telephone reminder call to increase breast cancer-screening attendance. Oncol Nurs Forum; 37. Epub ahead of print 2010. DOI: 10.1188/10.ONF.E312-E317. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 77.O’Brien MJ, Squires AP, Bixby RA, et al. Role Development of Community Health Workers. An examination of selection and training processes in the intervention literature. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37:262–S269. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ballard M, Bonds M, Jodi-Ann, Burey et al. Community Health Worker Assessment and Improvement Matrix (CHW AIM): updated Program Functionality Matrix for Optimizing Community Health Programs. Epub ahead of print 2018. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.27361.76644.

- 79.Kok MC, Kane SS, Tulloch O et al. How does context influence performance of community health workers in low- and middle-income countries? Evidence from the literature. Health Res Policy Syst; 13. Epub ahead of print 2015. DOI: 10.1186/s12961-015-0001-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 80.Lewin S, Glenton C, Daniels K et al. Lay health workers in primary and community health care for maternal and child health and the management of infectious diseases (review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Epub ahead of print 2005. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004015.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 81.Lehmann U, Sanders D. Community health workers: what do we know about them. Geneva World Health Organ; 42.

- 82.Egbujie BA, Delobelle PA, Levitt N, et al. Role of community health workers in type 2 diabetes mellitus self-management: a scoping review. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:1–18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Scott K, Beckham SW, Gross M, et al. What do we know about community-based health worker programs? A systematic review of existing reviews on community health workers. Hum Resour Health. 2018;16:1–17. doi: 10.1186/s12960-018-0304-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.World Health Organization . Action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases in the WHO European Region. Copenhagen: World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe; 2016. Regional Office for Europe. [Google Scholar]

- 85.WHO Europe - Search results for Community Health Workers., https://www.who.int/europe/home/search?indexCatalogue=eurosearchindex&searchQuery=community%20health%20work&wordsMode=AllWords (accessed 26 May 2023).

- 86.Van Loenen T, Van Den Muijsenbergh M, Hofmeester M, et al. Primary care for refugees and newly arrived migrants in Europe: a qualitative study on health needs, barriers and wishes. Eur J Public Health. 2018;28:82–7. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckx210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hodgins S, Kok M, Musoke D, et al. Community health workers at the dawn of a new era: 1. Introduction: tensions confronting large-scale CHW programmes. Health Res Policy Syst. 2021;19:1–24. doi: 10.1186/s12961-021-00752-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pinto RM, da Silva SB, Soriano R. Community health workers in Brazil’s Unified Health System: a framework of their praxis and contributions to patient health behaviors. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74:940–7. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.World Health Organization. What Do We Know About Community Health Workers? a Systematic Review of Existing Reviews. 2020.

- 90.Schleiff MJ, Aitken I, Alam MA, et al. Community health workers at the dawn of a new era: 6. Recruitment, training, and continuing education. Health Res Policy Syst. 2021;19:1–29. doi: 10.1186/s12961-021-00757-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rosenthal EL, Wiggins N, Ingram M, et al. Community health workers then and now: an overview of national studies aimed at defining the field. J Ambul Care Manage. 2011;34:247–59. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e31821c64d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Leong SL, Teoh SL, Fun WH, et al. Task shifting in primary care to tackle healthcare worker shortages: an umbrella review. Eur J Gen Pract. 2021;27:198–210. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2021.1954616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Singh D, Negin J, Otim M et al. The effect of payment and incentives on motivation and focus of community health workers: five case studies from low- and middle-income countries. Hum Resour Health; 13. Epub ahead of print 2015. DOI: 10.1186/s12960-015-0051-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]