Abstract

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death worldwide. Sex differences in lung cancer incidence and survival are known. Female sex is an independent good prognostic factor. Estrogens appear to play a key role in lung cancer outcomes. Accordingly, antiestrogen use may also influence survival in female non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients. In this study, we compared survival among antiestrogen users and nonusers. We performed a retrospective population-based study. Using the Manitoba Cancer Registry (MCR), we identified all women diagnosed with NSCLC from 2000 to 2007. The population-based Drug Program Information Network was accessed to establish which patients received antiestrogens. Demographic data (e.g., smoking patterns, stage, histology) were gathered from the MCR and by chart review. Survival differences between antiestrogen-exposed and not exposed groups were compared using multivariable Cox regression. Two thousand three hundred twenty women fit our patient criteria, of which 156 had received antiestrogens. Exposure to antiestrogens was associated with a significantly decreased mortality in those exposed both before and after the diagnosis of NSCLC (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.42, p = 0.0006). This association remained consistent across age and stage groups. Antiestrogen use before and after the diagnosis of NSCLC is associated with decreased mortality. This supports previous evidence that estrogens may play a key role in the biology and outcomes of NSCLC and suggests a potential therapeutic use for these agents in this disease.

Keywords: Lung Cancer, Fulvestrant, Primary Lung Cancer, Lung Cancer Mortality, Lung Cancer Incidence

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death worldwide. Despite advances in treatment, age-adjusted 5-year survival rates remain poor at 15 % [18]. The Canadian Cancer Society estimates that 25,600 Canadians will be diagnosed with lung cancer in 2012 while 20,100 will die from it. Women account for as many as 12,300 of these new cases and 9,400 deaths [4]. Since the 1990s, there has been an increasing trend in the incidence of lung cancer cases. Despite a recent decline in incidence and mortality among men in the USA, this epidemic continues to follow a rising trend among women in western countries [4, 17].

While tobacco exposure is a well-established major risk factor for the development of lung cancer, other factors contribute to the differing degree of lung cancer incidence in women compared to men [21, 23]. Estrogens appear to increase the risk of lung cancer in women by directly promoting cell proliferation in the lung and may also influence lung tumor metabolism [15]. A large prospective cohort study demonstrated a significant increase in the risk of lung cancer with the use of combined estrogen and progestin that was duration dependent, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.27 for 1 to 9 years of use and 1.48 for 10+ years of use [24]. In contrast, a recent subgroup analysis of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), where women were randomly and blindly assigned to combined estrogen and progesterone vs. estrogen alone vs. placebo, demonstrated that there was no statistical difference in the incidence of lung cancer between the arms [6, 7].

Females with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) have significantly better survival than males with the same disease, in all stages, histology, and methods of treatment [19, 20, 29]. Several retrospective studies have attempted to determine the link between exogenous hormone use and death from NSCLC. In these studies, conflicting observations, small sample sizes, poor study design, and incomplete analyses have made it difficult to determine a uniform consensus [1, 12, 28]. In the WHI, those women who developed lung cancer had a significant increase in the risk of death from lung cancer in the combined hormone group (HR 1.71; 95 % confidence interval (CI), 1.16–2.52; p = 0.01) [6, 7]. These studies suggest that estrogens play a role in lung cancer outcomes, but the mechanism for this effect remains unclear.

Antiestrogen use in breast cancer patients was recently examined for the incidence and mortality of NSCLC [3]. In this study, 6,655 women were diagnosed with breast cancer between 1980 and 2003 in the Geneva Cancer Registry, 46 % of whom had received some form of oral antiestrogen therapy. In those taking antiestrogen, they demonstrated a nonsignificant lower risk of developing lung cancer (standardized incidence rate per 100,000 person-years, 0.63; 95 % CI, 0.33–1.10) compared to the general population. However, the risk of death from lung cancer was significantly decreased among women who received antiestrogen therapy (standardized mortality rate per 100,000 person-years, 0.13; 95 % CI, 0.02–0.47) compared to the general population.

Manitoba is a Canadian province with a stable population of approximately 1.2 million. Population-based cancer registry and administrative data have been in place for over 50 and 25 years, respectively. Using these population-based data, we tested the hypothesis that antiestrogen use is associated with a lower risk of death from lung cancer.

Materials and Methods

Databases

Diagnosis and treatment codes have been recorded in the Manitoba Health Administrative databases since the early 1970s. The Personal Health Identification Number (PHIN) was added as a unique identifier for every citizen in Manitoba in 1984. Prescription data have been collected in the Drug Program Information Network (DPIN) since 1995. The Manitoba Cancer Registry (MCR) has used a mandatory reporting system to record all neoplastic diagnoses in Manitoba since 1956. The MCR has a long history of accurate data and is Gold Certified from the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries (the highest standard), which requires at least 95–98 % case ascertainment [5]. CancerCare Manitoba (CCMB) is the Provincial Cancer Centre serving the province of Manitoba and has maintained an electronic charting system for clinical records since 1997.

Study Population

All female patients diagnosed with NSCLC from January 1, 2000 to December 31, 2007 were identified from the MCR using the International Statistical Classification of Disease Codes (ICD-9 and ICD-10). These were linked to DPIN using individual patient PHIN numbers. Patients with small cell lung cancer, pleural-based malignancies, other thoracic neoplasms, and unspecified lung cancer were excluded from the study. The final study cohort excluded males. The remaining 2,320 females with NSCLC formed the main study cohort, in whom 2,375 NSCLC tumors were diagnosed. Subjects were considered exposed to antiestrogens if there was a record of a prescription fill of one of these medications at any time from 1995 to 2007 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Frequency table of antiestrogen exposure

| Antiestrogen | Numbera | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Tamoxifen | 74 | 40.88 |

| Raloxifene | 48 | 26.52 |

| Megestrol acetate | 22 | 12.15 |

| Anastrozole | 19 | 10.5 |

| Letrozole | 11 | 6.08 |

| Exemestane | 5 | 2.76 |

| Levonorgestrel | 1 | 0.55 |

| Goserelin | 1 | 0.55 |

aPatients may be in more than one category

Data Collection

Data extracted from the MCR for our patient population included date of diagnosis of NSCLC, date of birth, date of death, sex, histology, and treatment modalities. The date of diagnosis as recorded by the MCR is the date of first sample collection that pathologically confirmed NSCLC and the date of death were followed until May 31, 2011. Patients with metachronous primary lung cancers were analyzed with survival time from the date of their first primary lung cancer during the study period. Collaborative stage data were available from the MCR from January 2004 to December 2007. Physician staging was compiled manually through individual electronic chart review for those diagnosed between January 2000 and December 2004. The overlapping physician-based working stage data from 2004 was compared to the gold standard (collaborative stage) and there was high correlation within stage subgroupings (kappa 0.73). Therefore, all staging information was compiled together with collaborative stage used when available.

Demographic data not available in the MCR were manually collected from the electronic chart. Information was available for approximately two thirds of our patient cohort who presented to CCMB following diagnosis. Smoking histories, categorized as never or ever smoker, past or present smoker, and amount of smoking exposure were documented when present. The University of Manitoba Research Ethics Board approval was obtained with a waiver of informed consent.

Statistical Methods

Our main cohort was divided into two groups: those patients that received antiestrogen therapy and those patients that did not receive antiestrogen therapy. We further divided the antiestrogen-exposed group into exposures occurring before, after, and both before and after the diagnosis of NSCLC. Survival was measured from the date of diagnosis to the date of death and censored at the end of study (May 31, 2011). Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan–Meier survival functions, logrank testing, and a multivariable Cox proportional hazards survival model using SAS statistical software version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Predictor selection for the multivariable analysis was based on scientific and clinical importance of the variable and improvements in model fit. The final model included age (dichotomized at the median), histology (adenocarcinoma vs. non-adenocarcinoma), stage (I and II combined, III, and IV), and exposure to antiestrogen (exposure before, after, and both before and after the diagnosis of NSCLC). Stratified analyses were performed to evaluate the exposure effect size within age, stage, and histology subgroups. Sensitivity analyses were done for smoking history and type of antiestrogen.

Results

Cohort

We identified 2,320 women diagnosed with NSCLC that fit our patient criteria of which 156 received antiestrogen therapy. Demographic characteristics and the distribution of potential confounders are summarized in Table 2. Mean age at diagnosis for both antiestrogen and no antiestrogen groups was 69 (median 70, range 46–89 for antiestrogen exposed; median 71, range 25–99 for antiestrogen not exposed). Smoking data were collected via electronic records and thus was subject to missing data. The proportion of smokers was similar in those treated with antiestrogen therapy (83 %) vs. those who were not (88 %). Stage distribution was different between antiestrogen-exposed and unexposed groups with a higher proportion of stage I and II patients in the antiestrogen-exposed group (Χ 2, p = 0.03). As expected, therefore, there was a higher rate of surgery in the antiestrogen-exposed group (Χ 2, p = 0.003). Nearly 40 % of antiestrogen-exposed women had a past history of breast cancer, which may partially explain the lower stage of lung cancer at presentation in this group. History of other previous invasive (non-breast) cancer showed a similar pattern of stage distribution of lung cancer with more lower stage patients in those with cancer that may have experienced increased surveillance (Χ 2, p < 0.001; data not shown).

Table 2.

Demographics

| Characteristic | Antiestrogen therapy | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 156) | No (n = 2,164) | |

| Number (percent) | ||

| Age | ||

| <55 | 9 (5.8) | 224 (10.4) |

| 55–74 | 96 (61.5) | 1,112 (51.4) |

| 75+ | 51 (32.7) | 828 (38.3) |

| Smoking status | ||

| Not charted | 45 (28.8) | 958 (44.3) |

| Charted | 111 (71.2) | 1,206 (55.7) |

| Never | 19 (17.1) | 144 (11.9) |

| Ever | 92 (82.9) | 1,062 (88.1) |

| Past | 66 (71.7) | 751 (70.7) |

| Current | 26 (28.3) | 311 (29.3) |

| Smoking amount (pack-years) | ||

| Unknown | 46 (50.0) | 429 (40.4) |

| Known | 46 (50.0) | 633 (59.6) |

| <5 | 0 (0) | 6 (0.9) |

| 5–29 | 14 (30.4) | 195 (30.8) |

| 30+ | 32 (69.6) | 432 (67.9) |

| Staging | ||

| Unknown | 35 (22.4) | 521 (23.5) |

| Known | 121 (77.6) | 1,698 (76.5) |

| I | 41 (33.9) | 453 (26.7) |

| II | 9 (7.4) | 101 (5.9) |

| III | 35 (28.9) | 460 (27.1) |

| IV | 36 (29.8) | 684 (40.3) |

| Histology | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 78 (50.0) | 1,008 (46.6) |

| Squamous | 19 (12.2) | 302 (14.0) |

| Large cell | 3 (1.9) | 43 (2.0) |

| Adenosquamous | 4 (2.6) | 18 (0.8) |

| Giant cell | 1 (0.6) | 3 (0.1) |

| NSCLC—no obvious subtype | 51 (32.7) | 790 (36.5) |

| Treatment | ||

| Surgery | ||

| Yes | 64 (41.0) | 701 (31.6) |

| No | 92 (59.0) | 1,518 (68.4) |

| Radiotherapy | ||

| Yes | 62 (39.7) | 948 (42.7) |

| No | 94 (60.2) | 1,271 (57.3) |

| Chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | 45 (28.8) | 491 (22.1) |

| No | 111 (71.2) | 1,728 (77.9) |

| Previous breast cancer | ||

| Yes | 62 (39.7) | 22 (1.0) |

| No | 94 (60.3) | 2,142 (99.0) |

Antiestrogen Exposure

We examined the pattern of antiestrogen use in the 156 patients exposed. Based on the days supplied noted in the DPIN database, the mean duration of use was 883.9 days, with a median of 662.5 days and a range of 1–4,350. Antiestrogen use was also classified based on the timing, with 78 (50.0 %) being exposed prior to the diagnosis of lung cancer, 40 (25.6 %) being exposed after the diagnosis of lung cancer, and 38 (24.4 %) being exposed both before and after the diagnosis of lung cancer.

Survival Analyses

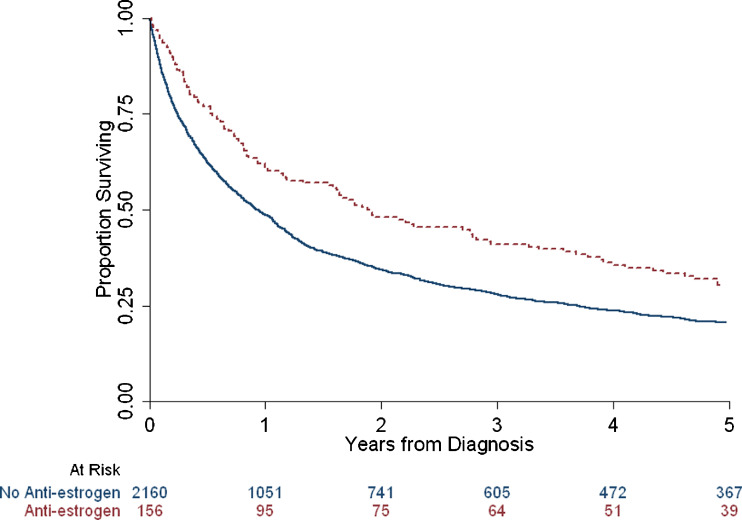

Univariate analysis of overall survival by antiestrogen use revealed a median and 5-year survival of 1.89 years and 33 %, respectively, among the antiestrogen cohort. These rates were significantly higher than those without antiestrogen use, with median and 5-year survival rates of 0.93 years and 22 %, respectively (logrank, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Unadjusted Kaplan–Meier survival function by antiestrogen exposure vs. no exposure

The final multivariable Cox model included antiestrogen exposure, age, stage, and histology. Exposure to antiestrogens both before and after the diagnosis of NSCLC was strongly associated with better survival (hazard ratio [HR] 0.42, p < 0.0006). Antiestrogen exposure either before or after the diagnosis of NSCLC was not associated with overall survival (Table 3). Despite the difference in stage distribution between the groups, antiestrogen exposure before and after the diagnosis of NSCLC remained a strong independent predictor of better of survival. Age, stage, and histology remained significant predictors of survival. Stratified multivariable analyses show a similar qualitative effect of antiestrogen exposure both before and after the diagnosis of lung cancer in each stratum, although the reduction in statistical power renders some of these estimates not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards model and stratified multivariable results

| Model | HR | 95 % CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Final model | |||

| Before and after vs. never user | 0.42 | 0.25–0.69 | 0.0006 |

| Before vs. never user | 1.08 | 0.80–1.46 | 0.6154 |

| After vs. never user | 0.97 | 0.58–1.62 | 0.8933 |

| Age group ≥70 vs. <70 | 1.40 | 1.26–1.55 | <0.0001 |

| Stage III vs. I and II | 3.24 | 2.80–3.75 | <0.0001 |

| Stage IV vs. I and II | 6.02 | 5.23–6.92 | <0.0001 |

| Adenocarcinoma vs. non-adenocarcinoma | 0.65 | 0.58–0.72 | <0.0001 |

| Age stratifieda | |||

| Before and after vs. never user (age ≥70) | 0.33 | 0.17–0.67 | 0.0018 |

| Before and after vs. never user (age <70) | 0.50 | 0.26–1.09 | 0.0858 |

| Stage stratifieda | |||

| Before and after vs. never user (stages I and II) | 0.28 | 0.08–1.06 | 0.0603 |

| Before and after vs. never user (stage III) | 0.44 | 0.18–1.06 | 0.0676 |

| Before and after vs. never user (stage IV) | 0.45 | 0.21–0.98 | 0.0454 |

| Histology stratifieda | |||

| Before and after vs. never user (adenocarcinoma) | 0.34 | 0.15–0.76 | 0.0086 |

| Before and after vs. never user (non-adenocarcinoma) | 0.47 | 0.25–0.88 | 0.0175 |

aStratified multivariable model result with only the before and after exposure result reported

Sensitivity analysis for the type of antiestrogen (selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) use vs. no-antiestrogen) showed the same qualitative difference in survival but did not meet statistical significance (HR 0.47, p = 0.0731). Separate sensitivity analysis of smoking history did not change model fit and was nonsignificant as a predictor of survival; hence, the final model excluded smoking history to maximize the number of patients in the model. Additionally, antiestrogen exposure before and after the diagnosis of lung cancer was found to have similar protective effects in smokers (HR 0.44, p = 0.0084).

Discussion

Exposure to antiestrogens before and after the diagnosis of NSCLC was associated with a significantly decreased risk of death in female patients in Manitoba. This remained true after controlling for age, histology, and stage. Our data are consistent with another population-based analysis in breast cancer patients that demonstrated a reduction in lung cancer mortality in those women taking antiestrogens compared to the general population [3]. The effect in that study was not seen in women with breast cancer who did not take antiestrogens, suggesting that the underlying diagnosis of breast cancer did not have an impact on lung cancer mortality. In our study, we directly compared members of a lung cancer population based on the use of antiestrogens and demonstrated a strongly protective effect compared to non-exposed patients.

The role of estrogens in lung cancer remains somewhat unclear. Several large epidemiological studies have confirmed an independent protective effect of female compared to male sex on lung cancer outcomes [9, 11, 19]. Part of this effect may be due to differences in noncancer-related mortality such as cardiovascular disease. Exogenous estrogens may, however, worsen outcomes in lung cancer. One study reported significantly worse outcomes in women with lung cancer taking hormone replacement therapy, defined as either estrogen alone or estrogen and progesterone combinations [12]. In contrast, Ayeni et al. found no association, although they describe poorer outcomes in general and the effect of progesterone was not reported [1]. Recently, the WHI reported more deaths from lung cancer in the combined estrogen and progesterone group compared to placebo [7]. No effect was seen in the estrogen replacement group alone [6].

Biological mechanisms for these effects have been described. Estrogen receptors (ER-α and ER-β) are expressed and active in NSCLC tissue [27]. ER activity has been shown to activate epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and enhances the epithelial–mesenchymal transition in lung cancer cell lines, suggesting a role for estrogens in tumor growth and promotion [25, 32]. This effect may be sex specific, with nuclear localization and ER activity seen in NSCLC lines from female but not male patients, despite similar amounts of ER expression [9, 13]. Intratumoral estradiol concentrations are well correlated with markers of proliferation in ER-α or ER-β positive cases, and cellular proliferation in vitro has been inhibited with both tamoxifen and raloxifene [16]. Tamoxifen appears to inhibit the invasion capacity of ER-positive NSCLC cells by lowering the MMP-9/TIMP-1 ratio [31]. Data from a number of studies also suggest an antiproliferative effect of fulvestrant on NSCLC cell lines [2]. Furthermore, aromatase, the enzyme responsible for a key step in estrogen biosynthesis, is present in NSCLC cell lines and targeted inhibition results in decreased cellular proliferation and increased apoptosis [14, 16, 30]. Additive effects have been seen using combinations of antiestrogens with EGFR inhibitors [2, 22]. A recent animal model study demonstrated reduced lung tumor development with combination antiestrogen (SERM with aromatase inhibitor) when exposed to a tobacco carcinogen [26]. These studies support our results, and together suggest a protective effect of inhibiting estrogen signaling in NSCLC, perhaps by slowing lung cancer development and proliferation, reducing the tumor burden and making it more amenable to surgical resection.

The survival advantage noted in our study was limited to those who were exposed to antiestrogens both before and after the diagnosis of lung cancer, suggesting that either long durations of antiestrogen use are necessary for this effect or that we did not have sufficient power to show a difference in survival in those exposed only before or after NSCLC. Alternatively, the use of antiestrogens throughout the development, detection, and treatment of a NSCLC may be required to reduce the lethality of this disease, and stopping too early or starting too late does not have the same effect. Access to the MCR captured all NSCLC cases providing us with this large population-based cohort and eliminating selection bias, but with greater numbers, we may have seen an association with antiestrogen use before or after the lung cancer diagnosis. The DPIN database captured all prescriptions filled in the province since 1995 and eliminated the potential for biases that result from patient questionnaires and patient recall; however, we could not capture any use prior to the institution of DPIN. To allow for pre-NSCLC exposures, we elected to capture patients diagnosed with NSCLC after 2000, thereby limiting our cohort size. Patients exposed to antiestrogens prior to the diagnosis of NSCLC therefore could have had years of exposure, yet no effect on survival was seen. It is not clear, based on this observation, if antiestrogens impact the early pathogenesis or growth of NSCLC. For those exposed after the diagnosis of lung cancer, exposure duration was more limited because of the significantly shortened life expectancy from lung cancer itself. Furthermore, we would have needed considerably more patients in the after NSCLC exposure group or a very strong effect size to detect a difference. The point estimate of the HR in this group was very close to 1.0, but with a wide confidence interval. Further investigation into the effect of antiestrogen exposures after the diagnosis of NSCLC would require a large prospective study.

It remains possible that the survival advantage noted in our antiestrogen cohort is a result of surveillance bias. A significant portion of patients in the antiestrogen exposure group had a previous history of breast cancer, raising the possibility that these patients may have increased surveillance as an explanation of the lower stage at presentation for their lung cancer. To assess the impact of surveillance bias, we analyzed the lung cancer stage for patients with a history of any other invasive cancer (excluding breast cancer and non-melanoma skin cancers). Patients with a history of any other invasive cancer had a lower stage at presentation (p < 0.001), very similar to those with a history of breast cancer, suggesting that while surveillance bias may have played a role in the lower stage at diagnosis, it was not limited to those with breast cancer and therefore not preferentially found in our exposure group.

This study was restricted to patients with confirmed NSCLC so that the outcomes were not confounded by treatment effects and prognostic factors from other thoracic malignancies. This restriction also helped to ensure that the histology was of primary lung cancers, and of NSCLC origin, particularly since many patients had previous breast cancer that can commonly metastasize to the lung. Furthermore, despite the population-based nature of our data, we found a relatively small number of antiestrogen users and were limited in our ability to control for smoking based on the available data from chart review. It remains possible that the difference in outcome noted in our study is due to noncancer-related mortality. Cause of death data are available in the MCR, but have well-known limitations since they are based on death certificate data. The risk of cardiovascular disease in this cohort is relatively high, and it is possible that antiestrogen therapy impacted cardiovascular risk. Based on breast cancer literature, however, the effect of antiestrogens on cardiovascular disease is felt to be too small to account for the difference in survival noted in our study [8, 10].

We have shown a strong association between the use of antiestrogens before and after the diagnosis of NSCLC and better survival in our population-based study. Although this is in line with previous work, further questions remain. In particular, defining the population who may derive the greatest benefit from antiestrogen therapies, further exploration of which antiestrogen provides the strongest effect, and evaluating the appropriate setting for antiestrogen use in this disease is necessary. Antiestrogens are well studied in the breast cancer setting and therefore have well-defined toxicity, relatively low cost, and are readily accessible. While these features and potential benefits make their use in lung cancer extremely promising, further data, including a well-designed randomized controlled trial, are necessary before their adoption in clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

Funding was received from The Manitoba Medical Service Foundation and the Winnipeg Foundation. The Manitoba Health Research Council and CCMB provided stipendiary support. The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the Thoracic Oncology Research Group at CancerCare Manitoba. The results and conclusions presented are those of the authors. No official endorsement by Manitoba Health is intended or should be inferred.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ayeni O, Robinson A. Hormone replacement therapy and outcomes for women with non-small cell lung cancer: can an association be confirmed. Current Oncol. 2009;16:21–25. doi: 10.3916/c32-2009-02-001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bogush TA, Dudko EA, Beme AA, Bogush EA, Kim AI, Polotsky BE, Tjuljandin SA, Davydov MI. Estrogen receptors, antiestrogens, and non-small cell lung cancer. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2010;75(12):1421–1427. doi: 10.1134/S0006297910120011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouchardy C, Benhamou S, Schaffar R, Verkooijen HM, Fioretta G, Schubert H, Vinh-Hung V, Soria J-C, Vlastos G, Rapiti E. Lung cancer mortality risk among breast cancer patients treated with anti-estrogens. Cancer. 2011;117(6):1288–1295. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canadian Cancer Statistics 2012 (2012) Canadian Cancer Society. http://www.cancer.ca. Accessed December 2012

- 5.Registries Certified in 2007 for 2004 Incidence Data. North American Association of Central Cancer Registries (NAACCR). http://www.naaccr.org. Accessed May 2013.

- 6.Chlebowski RT, Anderson GL, Manson JAE, Schwartz AG, Wakelee H, Gass M, Rebecca J, Rodabough, et al. Lung cancer among postmenopausal women treated with estrogen alone in the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trial. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2010;102(18):1413–1421. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chlebowski RT, Schwartz AG, Wakelee HA, Anderson GL, Stefanick ML, Manson JE, Rodabough RJ, et al. Oestrogen plus progestin and lung cancer in postmenopausal women (Women’s Health Initiative trial): a post-hoc analysis of a randomized control trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;374:1243–1251. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61526-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cuzick J, Sestak I, Baum M, Buzdar A, Howell A, Dowsett M, Forbes JF. Effect of anastrozole and tamoxifen as adjuvant treatment for early-stage breast cancer: 10-year analysis of the ATAC trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2010;11(12):1135–1141. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70257-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dougherty, Susan M, Williard M, Bohn AR, Robinson KA, Mattingly KA, Blankenship KA, Huff MO, McGregor WG, Klinge CM. Gender difference in the activity but not expression of estrogen receptors α and β in human lung adenocarcinoma cells. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2006;13(1):113–134. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, Cecchini RS, Cronin WM, Robidoux A, Bevers TB, et al. Tamoxifen for the prevention of breast cancer: current status of the National Surgical Adjvuant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1652–1662. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu JB, Ying Kau T, Severson RK, Kalemkerian GP. Lung cancer in women analysis of the national Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Database. CHEST Journal. 2005;127(3):768–777. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.3.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganti A, Sahmoun A, Panwalkar A, Tendulkar K, Potti A. Hormone replacement therapy is associated with decreased survival in women with lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:59–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.9827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ivanova MM, Mazhawidza W, Dougherty SM, Klinge CM. Sex differences in estrogen receptor subcellular location and activity in lung adenocarcinoma cells. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 2010;42(3):320–330. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0059OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koutras A, Giannopoulou E, Kritikou I, Antonacopoulou A, Evans TR, Papvassiliou AG, Kalofonos H. Antiproliferative effect of exemestane in lung cancer cells. Mol Cancer. 2009;8:109. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kreuzer M, Gerken M, Heinrich J. Hormonal factors and risk of lung cancer among women. Int J Epi. 2003;32:263–271. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niikawa H, Suzuki T, Miki Y, Suzuki S, Nagasaki S, Akahira J, Honma S, et al. Intratumoral estrogens and estrogen receptors in human non-small cell lung carcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research. 2008;14(14):4417–4426. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parkin M. Global cancer statistics in the year 2000. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2:533–43. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(01)00486-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parkin M, Bray FI, Ferlay J. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pitz MW, Musto G, Navaratnam S. Sex as an independent prognostic factor in a population-based non-small cell lung cancer cohort. Can Respir J. 2013;20(1):30–34. doi: 10.1155/2013/618691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Radzikowska E, Glaz P, Roszkowski K. Lung cancer in women: age, smoking, histology, performance status, stage, initial treatment and survival. Population-based study of 20 561 cases. Ann Oncol. 2002;13(7):1087–1093. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rivera MP, Stover DE. Gender and lung cancer. Clin Chest Med. 2004;25:391–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shen H, Yuan Y, Jing S, Wen G, Yong-Qian S. Combined tamoxifen and gefitinib in non-small cell lung cancer shows antiproliferative effects. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2010;64(2):88–92. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siegfried JM. Women and lung cancer: does oestrogen play a role? Lancet Oncol. 2001;2:506–513. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(01)00457-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slatore CG, Chien JW, Au DH, Satia JA, White E. Lung cancer and hormone replacement therapy: association in the vitamins and lifestyle study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(9):1540–1546. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stabile LP, Lyker JS, Gubish CT, Zhang W, Grandis JR, Siegfried JM. Combined targeting of the estrogen receptor and the epidermal growth factor receptor in non-small cell lung cancer shows enhanced antiproliferative effects. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1459–1470. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stabile LP, Rothstein ME, Cunningham DE, Land SR, Dacic S, Keohavong P, Siegfried JM. Prevention of tobacco carcinogen-induced lung cancer in female mice using antiestrogens. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33(11):2181–2189. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stabile LP, Siegfried JM. Estrogen receptor pathways in lung cancer. Curr Oncol Rep. 2004;6:259–267. doi: 10.1007/s11912-004-0033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taioli E, Wynder EL. Endocrine factors and adenocarcinoma of the lung in women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:869–870. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.11.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomas L, Doyle L, Edelman M. Lung cancer in women: emerging differences in epidemiology, biology, and therapy. Chest. 2005;128:370–381. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.1.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verma MK, Miki Y, Sasano H. Aromatase in human lung carcinoma. Steroids. 2011;76:759–764. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2011.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang X-Y, Yan W, Hong-Chun L. Tamoxifen lowers the MMP-9/TIMP-1 ratio and inhibits the invasion capacity of ER-positive non-small cell lung cancer cells. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2011;65(7):525–528. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao G, Nie Y, Lv M, He L, Wang T, Hou Y. ERβ-mediated estradiol enhances epithelial mesenchymal transition of lung adenocarcinoma through increasing transcription of midkine. Molecular Endocrinology. 2012;26(8):1304–1315. doi: 10.1210/me.2012-1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]