Abstract

Clostridium perfringens can obtain sialic acid from host tissues by the activity of sialidase enzymes on sialoglycoconjugates. After sialic acid is transported into the cell, sialic acid lyase (NanA) then catalyzes the hydrolysis of sialic acid into pyruvate and N-acetylmannosamine. The latter is converted for use as a biosynthetic intermediate or carbohydrate source in a pathway including an epimerase (NanE) that converts N-acetylmannosamine-6-phosphate to N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate. A 4.0-kb DNA fragment from C. perfringens NCTC 8798 that contains the nanE and nanA genes has been cloned. The identification of the nanA gene product as sialic acid lyase was confirmed by overexpressing the gene and measuring sialic acid lyase activity in a nanA Escherichia coli strain, EV78. The nanA gene product was also shown to restore growth to EV78 in minimal medium with sialic acid as the sole carbon source. By using Northern blot experiments, it was demonstrated that the nanE and nanA genes comprise an operon and that transcription of the operon in C. perfringens is inducible by the addition of sialic acid to the growth medium. The Northern blot experiments also showed that there is no catabolite repression of nanE-nanA transcription by glucose. With a plasmid construct containing a promoterless cpe-gusA gene fusion, in which β-glucuronidase activity indicated that the gusA gene acted as a reporter for transcription, a promoter was localized to the region upstream of the nanE gene. Primer extension experiments then allowed us to identify a sialic acid-inducible promoter located 30 bp upstream of the nanE coding sequence.

Clostridium perfringens is a ubiquitous pathogenic bacterium. In nature, it is found in soils and sediments as well as in the intestinal tracts of animals, especially birds and mammals (21). C. perfringens in humans commonly causes clostridial myonecrosis (gas gangrene), acute food poisoning, and antibiotic-associated diarrhea (21); in domestic livestock, it causes a wide range of enteric diseases (15). For C. perfringens gangrene and enteric infections, it has been postulated that the availability of nutrients for bacterial growth is an important factor in the disease process (5). One nutrient that C. perfringens can readily obtain and metabolize is sialic acid.

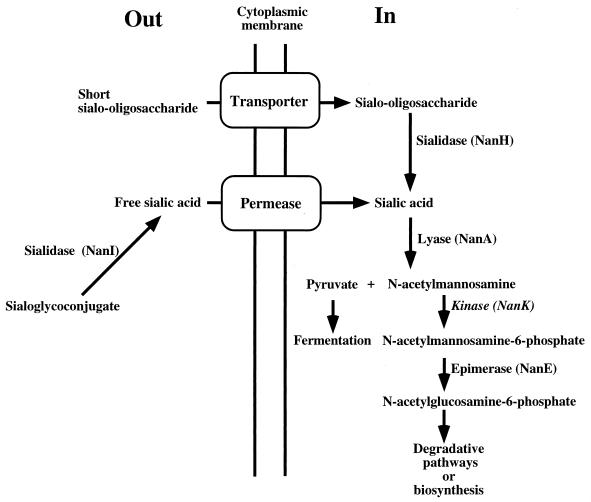

Sialic acids comprise a family of related sugar moieties that are found throughout the body as a component of glycoproteins, gangliosides, and other sialoglycoconjugates (23). C. perfringens produces enzymes that release sialic acid from sialoglycoconjugates, transport it into the cell, and degrade it as a source of nutrients or biosynthetic intermediates (Fig. 1). Sialic acids are especially abundant in the intestinal tract, where they are a major constituent of mucins (23). The enzyme sialidase (or neuraminidase) is able to cleave terminal sialic acid residues from carbohydrate polymers, making them available as nutrients (5). C. perfringens is an unusual bacterium in that it synthesizes two different sialidase enzymes. The larger sialidase (71 kDa), NanI, is secreted from the cell and exhibits a broad substrate specificity (18). This enzyme is probably responsible for providing free sialic acid to C. perfringens in the intestinal tract and host tissues. C. perfringens also synthesizes a smaller (43-kDa) cytoplasmic sialidase, NanH (18, 19). The role of the cytoplasmic enzyme was initially puzzling, since the substrate for sialidase is usually a complex carbohydrate that cannot be transported into the cell. However, more recent work shows that NanH has a marked preference for cleaving sialic acid conjugated to short oligosaccharides (18, 20), suggesting that NanH may act on low-molecular-weight oligosaccharides that can be transported into the cell (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram illustrating the proposed pathway of sialic acid metabolism in C. perfringens. The genes encoding each enzyme except the transporter, permease, and kinase (NanK) have been detected in C. perfringens.

Sialic acid lyase (NanA) is a cytoplasmic enzyme that functions to split sialic acid into pyruvate and N-acetylmannosamine (Fig. 1). The C. perfringens lyase enzyme was first purified many years ago (14), has well-characterized kinetic constants, and is commonly used as a reagent to synthesize sialic acid derivatives (5). An earlier report by Nees and Schauer demonstrated that sialic acid lyase enzyme activity, as well as sialidase enzyme activity, was induced when substrates containing sialic acid were added to the medium (13).

A small family of genes encoding proteins with high levels of amino acid sequence similarity have been found to be located near nanA genes in Escherichia coli and Haemophilus influenzae and in an open reading frame (ORF) unlinked to nanA in Borrelia burgdorferi. The E. coli gene in this family (yhcJ) has recently been designated as encoding an epimerase enzyme that converts N-acetylmannosamine-6-phosphate to N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate and has been renamed nanE (17). In this report, we describe the cloning, sequence analysis, and transcriptional regulation of an operon encoding the nanE and nanA gene products from C. perfringens. Concurrently with the work detailed here, Traving et al. published a report describing the cloning and sequence analysis of the nanA gene from C. perfringens A99 (26).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli JM107 and DH10B were used for the routine transformation of plasmids. Either Luria broth (LB) (10 g of tryptone, 5 g of NaCl, and 5 g of yeast extract) or M9 minimal medium [12.8 g of Na2HPO4 · 7H2O, 3 g of KH2PO4, 0.5 g of NaCl, and 1 g of (NH4)2SO4 per liter] with added carbohydrate was used to grow the E. coli strains. To grow C. perfringens, anaerobic PGY medium (30 g of Proteose Peptone, 20 g of glucose, 10 g of yeast extract, and 1 g of sodium thioglycolate per liter) or PY medium (the same as PGY but lacking glucose) was prepared and stored in an anaerobic chamber (Coy Laboratory Products, Inc.), as previously described (31).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| JM107 | endA′ gyrA96 thi hsdR17 supE44 relA1 λ− Δ(lac-proAB) F′ traD36 proAB lacIqlacZΔM13 | 29 |

| GMS343 | lacY1 tsx-29? glnV44 (AS)? galK2 λ− manA4 aroD6 rpsL7000(str) mtl-1 argE3(Oc) | 16 |

| EV78 | araD139 Δ(argF-lac)U169 flbB5301 deoC1 rpsL150 relA1 ptsF25 rbsR nanA4 zgj-791::Tn10 | 27 |

| DH10B | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80dlacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 deoR recA1 araΔ139 Δ(ara leu)7697 galU galK λ− rpsL endA1 nupG | Gibco/BRL |

| C. perfringens | ||

| NCTC 8798 | C. Duncan | |

| SM101 | High-electroporation derivative of NCTC 8798 | 31 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pJIR750 | 1 | |

| pBluescript SK(−) | Stratagene | |

| pTrc99 | Pharmacia Biotech | |

| pACYC184 | 3 | |

| PCR2.1 | Invitrogen, Inc. | |

| pDMW3 | This study | |

| pDMW9b | This study | |

| pSM212 | This study | |

| pSM218 | This study | |

| pSM222 | This study | |

| pSM227 | This study | |

| pSM228 | This study |

Plasmid constructs and DNA manipulations.

The plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Chromosomal DNA was isolated from C. perfringens by the method described by Mengaud et al. (11), except that the cells were incubated at 37°C for 20 min after the addition of lysozyme and 30 min after the addition of proteinase K.

In order to construct a plasmid gene bank, 10 μg of C. perfringens chromosomal DNA and 5 μg of pACYC184 were digested with EcoRI overnight at 37°C; pACYC184 was then treated with alkaline phosphatase. The digested plasmid and chromosomal DNA were electrophoresed through a 1% agarose gel. Chromosomal DNA fragments between 3 and 10 kb in length and the EcoRI-cut pACYC184 were purified from the gel with the Qiaex II gel extraction kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After ligation, the plasmids were transformed into E. coli JM107 by electroporation and plated on LB agar plates with 15 μg of tetracycline per ml. Colonies were washed off the plates with LB and stored in 15% glycerol at −80°C.

Fifty microliters of electrocompetent E. coli GMS343 (manA) cells were pulsed in a 2-mm cuvette with 1 μg of the EcoRI gene bank plasmid DNA and then plated on M9 medium with 15 μg of tetracycline per ml and 5 g of mannose per liter. One isolate grew above background levels but not to the same extent as the wild-type JM107 (manA+) control. The transformant contained a recombinant plasmid with a 4.1-kb insert in the EcoRI site of pACYC184; it was called pDMW3. A 4.0-kb EcoRI-XbaI fragment from pDMW3 was subcloned into the EcoRI-XbaI sites of the plasmid pBluescript SK(−) to make pDMW9b.

The Erase-a-Base system (Promega Corp.) was utilized to make a series of nested deletions in the insert of pDMW9b. The resulting plasmids were sequenced with an Applied Biosystems, Incorporated, model 373A DNA sequencer.

For expression studies, the nanA gene was amplified by PCR with oligonucleotides ODMW5 (5′-CAAATAGAATTCGGATTTTGGGAGGAGAAAAAC-3′), which has an EcoRI site (shown in italics), and ODMW6 (5′-TAAGAGCTGCAGGCTAGTGATAAGAATTGAAATTGGAC-3′), which has a PstI site. Both the PCR product (nanA) and pTrc99 were digested with EcoRI and PstI and ligated together to form pDMW67.

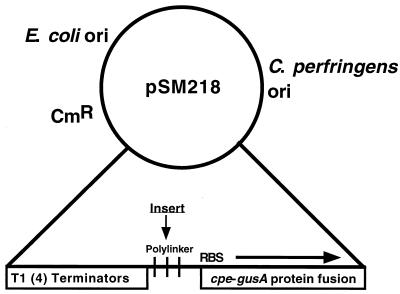

The promoterless cpe-gusA gene fusion vector was created as follows. A cloned cpe-gusA fusion from pSM129 (31), containing 25 bases upstream of the cpe ATG initiation codon (including the putative ribosomal binding site) and the coding sequence for the first 13 amino acids of Cpe, was amplified by PCR with primers engineering 5′ PstI and 3′ HindIII sites. This PCR fragment was ligated to pJIR750 at the PstI and HindIII sites to make pSM212. Then, the four consecutive terminators of pRS415 (25) were amplified by PCR with primers with an EcoRI site at the 5′ end and a KpnI site at the 3′ end to provide the proper orientation for the terminators. The PCR product was cloned into pCR2.1, which was then digested with EcoRI and KpnI and ligated to pSM212 at the EcoRI and KpnI sites to create plasmid pSM218.

NanA overexpression.

An E. coli nanA Tn10 insertion mutant, strain EV78, was obtained from Eric Vimr (27). Overnight cultures of either pDMW67 or pTrc99 in EV78 were diluted 1:50 in LB containing 100 μg of ampicillin per ml and then incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to a final concentration of 0.5 mM, and the cells were grown at 37°C until reaching stationary phase, which was approximately 2 h later. The cells were pelleted and washed with phosphate-buffered saline. Five hundred microliters of sample buffer (2% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 150 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 2% β-mercaptoethanol, 20% sucrose, and 0.05% bromophenol blue) were added to each sample prior to a 15-s sonication (model 450 Sonifier; Branson). Following sonication, the sample was boiled for 10 min and immediately cooled on ice for 2 min. Then a portion of the sample was electrophoresed through a SDS–10% polyacrylamide gel and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue, as described previously (22).

Growth of the complemented E. coli mutant.

Overnight cultures of E. coli EV78(pDMW67) or EV78(pTrc99) in LB containing 100 μg of ampicillin per ml were diluted 1:100 in M9 minimal medium with 3.2 mM sialic acid and 100 μg of ampicillin per ml in sidearm flasks at 37°C. IPTG (to 0.5 mM) was added after 8 h of growth. The optical density was then monitored with a Klett-Summerson photoelectric colorimeter until the cells reached stationary phase.

Sialic acid lyase assay in E. coli extracts.

Overnight cultures of E. coli EV78 (pDMW67 or pTrc99) were diluted 1:50 in LB plus 100 μg of ampicillin per ml. The cultures were incubated at 37°C on a shaking rotor for 2.5 h. IPTG was added to a final concentration of 0.5 mM. The cultures were grown for an additional 2 h. The cells were washed twice in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), resuspended in 1 ml of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), and then subjected to four rounds of sonication (model 450 Sonifier; Branson) consisting of 30 s of sonication followed by 30 s on ice. The lysed cells were centrifuged for 15 min at 15,000 × g to remove cell debris. The supernatant was removed and loaded on a Sephadex G-25 desalting column. Two-milliliter fractions were collected, and the protein content was measured with the Bio-Rad protein assay kit with bovine serum albumin as the standard. Either 25 or 50 μg of protein was used in the lactate dehydrogenase-coupled assay for sialic acid lyase, as previously described (30).

Primer extension and Northern blot assays.

Strain NCTC 8798 was grown in 10 ml of PY medium with and without the addition of carbon sources. When the cells were at mid-logarithmic phase, the total RNA was extracted with Trizol reagent (Gibco/BRL) as described earlier (10). Primer extension analysis was carried out with 40 μg of RNA and the Promega primer extension system kit, according to the manufacturer’s directions. The oligonucleotide ODMW21 (5′-CTCTTATAGCCGCTGCTCCACC-3′) annealed to the 5′ region of nanE mRNA. A DNA sequencing ladder was created by using ODMW21 as a primer and pDMW9b as a template, according to the United States Biochemical Co. protocol. Primer extension and sequencing products were electrophoresed through a 5% acrylamide gel and visualized by autoradiography, as previously described (10). Ten micrograms of total RNA was used for Northern blot analysis. All steps, including transferring the RNA to a nylon membrane, hybridizing with the biotinylated probe, and developing the light-emitting reaction, were based on the NEBlot Phototope and Phototope Star detection kit protocols (New England Biolabs).

Transformation of C. perfringens and β-glucuronidase assays.

Plasmids were introduced into C. perfringens by electroporation, as previously described (10). β-Glucuronidase assays in C. perfringens whole cells were performed as previously described (10).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the nanE and nanA gene region has been deposited in GenBank with the accession no. AF130859.

RESULTS

Cloning and analysis of a 4.0-kb DNA fragment containing the C. perfringens nanE and nanA genes.

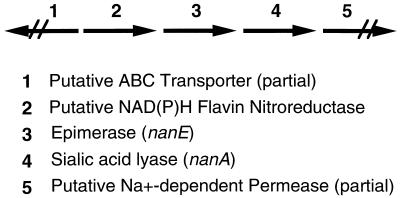

We undertook a search for genes involved in mannose biosynthesis in C. perfringens, since mannose is a component of the capsule of strain NCTC 8798 (4), the subject of this study. To isolate a potential manA gene of C. perfringens that would encode a phosphomannose isomerase, we transformed an E. coli manA strain, GMS343, with a plasmid library containing EcoRI restriction-digested chromosomal DNA from strain NCTC 8798 cloned into the EcoRI site of plasmid pACYC184. Transformants were selected for restoration of their ability to grow on M9 minimal medium plates with mannose as the sole carbon source for cell growth. We identified a transformant, containing pDMW3, that partially restored growth on mannose. A 4.0-kb EcoRI-XbaI fragment from pDMW3, cloned into pBluescript SK(−), was used to make pDMW9b. Preliminary sequence analysis of the insert indicated there were three complete ORFs present and two partial ORFs at the ends of the insert (Fig. 2). Two of the ORFs encode gene products similar to proteins known to be involved in sialic acid metabolism in E. coli: nanE encodes an epimerase that converts N-acetylmannosamine-6-phosphate to N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate (17), and nanA encodes sialic acid lyase (26).

FIG. 2.

Schematic diagram showing the gene arrangement in the 4.0-kb insert in pDMW9b. ABC, ATP-binding cassette.

The complete sequences of nanE, nanA, and a partial ORF downstream of nanA were determined. Concurrently with this work, a report describing the cloning and sequence analysis of the nanA gene from C. perfringens A99 and two adjacent partial ORFs was published (26); the upstream ORF is now proposed to be an ortholog of the nanE gene, as described in this report. There are 10 single base pair differences between the DNA sequences of the nanA structural genes in strains NCTC 8798 and A99 (28). Eight are silent changes, but NCTC 8798 nanA predicts an isoleucine at position 211 instead of the valine in strain A99 and a glutamate residue at position 278 instead of the alanine in strain A99.

The nanE gene encodes a protein of 221 amino acids with a predicted molecular weight of 24,167. The C. perfringens sequence shows the highest level of similarity (52.0% identical residues) to an ORF in B. burgdorferi, termed BB0644 (7), with somewhat less similarity to the NanE orthologs from E. coli (formerly YhcJ [2]) (40.8%) and H. influenzae HI0145 (39.9%) (6). The nanA gene of C. perfringens encodes a protein of 288 amino acids with a predicted molecular weight of 32,458. The NanA protein exhibits a high level of similarity to the NanA proteins of H. influenzae (6) (73% identical residues) and Trichomonas vaginalis (12) (68.5%), while it is much less similar to NanA of E. coli (38.4%).

A partial sequence analysis of the insert in pDMW9b upstream of nanE shows an ORF with a low level of sequence similarity to a putative NAD(P)H nitroreductase from Bacillus subtilis termed YfkO (GenBank accession no. D83967) (28) and to part of an ATP-binding cassette transporter that is transcribed divergently from the NADP(H) nitroreductase (Fig. 2) (28). Downstream of the nanA coding region is part of a gene (ORF1) that showed a low level of similarity to an Na+-dependent permease in Synechocystis spp. (28).

Complementation of a nanA mutation in E. coli with the nanA gene of C. perfringens.

We wanted to confirm that the nanA gene product in pDMW9b encodes a sialic acid lyase enzyme. Therefore, pDMW67 was transformed into the E. coli nanA strain, EV78 (27). Strain EV78 was made by transduction of the nanA4 allele from strain EV51 into strain MC4100. The parent of EV51, strain EV36 (nanA+), is capable of growth on sialic acid in minimal medium (27). After cell growth and the addition of 0.5 mM IPTG, a brightly staining band corresponding to a molecular mass of 33 kDa was detected in cell extracts electrophoresed through SDS-polyacrylamide gels (28), very close to the predicted molecular mass for NanA of 32.5 kDa. We next determined if the nanA gene expression from pDMW67 could restore lyase enzyme activity and allow growth in minimal medium with sialic acid as the sole carbon source. As seen in Table 2, pDMW67 was able to restore both sialic acid lyase enzyme activity and growth in minimal medium plus sialic acid.

TABLE 2.

Complementation of sialic acid lyase activity and restoration of growth on sialic acid by the C. perfringens nanA gene in an E. coli nanA strain, EV78

| Plasmid | Growth yielda | Sialic acid lyase activityb |

|---|---|---|

| pTrc99 (vector control) | 4 | Not detectable |

| pDMW67 (−IPTG) | 37 | 20 |

| pDMW67 (+IPTG) | 22 | 329 |

Values are Klett units at entry into stationary phase.

Values are nanomoles of NADH oxidized per minute per milligram of protein.

Northern blot analysis indicates that nanE and nanA comprise a bicistronic operon.

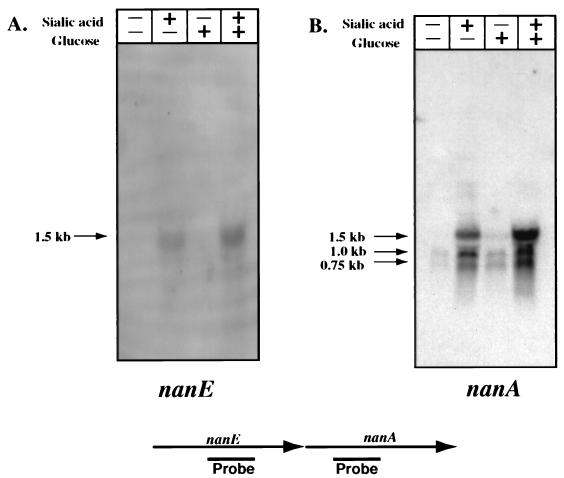

Since the NanE and NanA enzymes are involved in the same catabolic pathway, we wished to determine if they are coordinately regulated at the transcriptional level. We isolated total RNA from C. perfringens cells grown in PY medium with either no additional carbohydrate, 3.2 mM sialic acid, 1.4 mM glucose, or 3.2 mM sialic acid plus 1.4 mM glucose. Membranes containing this RNA were hybridized with probes internal to the nanE and nanA genes (Fig. 3). With the nanE probe, a band corresponding to a 1.5-kb transcript was detected when sialic acid was added to the medium, but not in its absence (Fig. 3A). The same-size band was also detected when 1.4 mM glucose was added in addition to 3.2 mM sialic acid, indicating that glucose does not have a catabolite repression effect on nanE transcription. Similar results were seen with a 1.5-kb RNA species when the nanA-specific probe was used (Fig. 3B). With the nanA-specific probe, two additional hybridizing bands 1.0 and 0.75 kb in length were detected under all conditions but at much higher levels in the lanes in which sialic acid was included in the medium (Fig. 3B). These shorter bands probably represent mRNA processing of the full-length nanE-nanA transcript, since no additional promoters could be detected downstream of the nanE promoter region (see next section). In addition, longer, weakly hybridizing mRNA species were detected in the lane containing sialic acid alone (Fig. 3B). Northern blot analysis with a probe specific for the putative permease gene (ORF1) located downstream of nanA (Fig. 2) failed to identify any hybridizing bands (28), which indicated that the small amount of transcription of this gene under the conditions tested was below the level of detection of the Northern blot assay.

FIG. 3.

(Top) Northern blot analysis of RNA from C. perfringens grown with different carbon sources hybridized with a nanE-specific probe (A) or a nanA-specific probe (B). (Bottom) Schematic diagram of the relative locations of the probes used for the blots shown at the top.

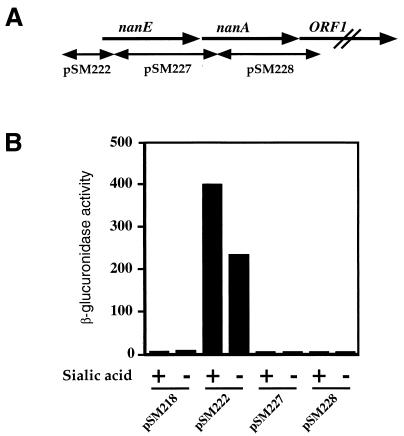

Localization of the nanE-nanA promoter.

We constructed a vector, pSM218 (Fig. 4), that allowed us to identify promoter elements in C. perfringens DNA. This vector has four tandem terminators to minimize vector-based transcription and a multiple cloning site located upstream of a promoterless cpe-gusA protein fusion. The ribosomal binding site and first 13 amino acids of the cpe gene coding region were retained to provide efficient translation (10), while the gusA gene (8) acted as a transcriptional reporter element. Three regions of the nanE-nanA operon (Fig. 5A) were placed in front of the promoterless cpe-gusA gene, and their abilities to initiate transcription in C. perfringens under inducing (PY with 3.2 mM sialic acid) and noninducing (PY with no added carbohydrate) conditions were measured (Fig. 5B). Only the fragment that included the region upstream of nanE exhibited transcription under the conditions tested, indicating that a promoter was located in this region. However, due to a high level of transcription under noninducing conditions, the level of transcription from the nanE promoter was only twofold greater when sialic acid was added to the growth medium (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 4.

Schematic diagram illustrating the relevant features of the vector used to identify promoter elements in C. perfringens. RBS, putative ribosome binding site; ori, origin of replication.

FIG. 5.

Location (A) and transcriptional activity (measured as β-glucuronidase activity) (B) of DNA fragments cloned into the polylinker site of plasmid pSM218.

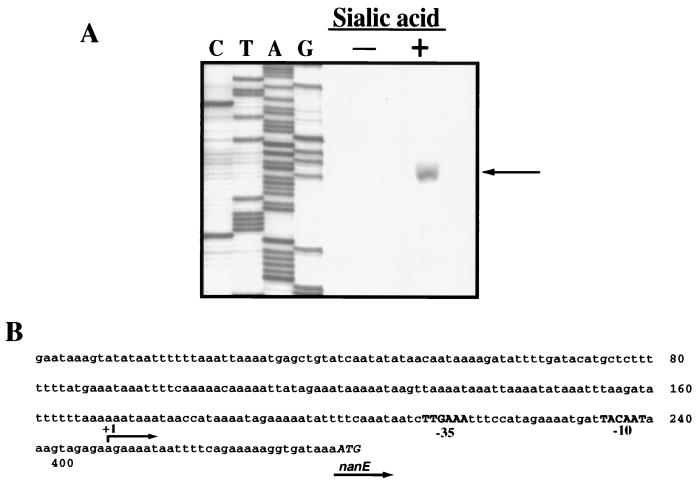

Having determined that the nanE-nanA promoter lay upstream of the nanE coding region, we used primer extension experiments to locate it precisely. We detected a 5′ end located 34 bp upstream of the nanE coding region (Fig. 6A). In addition, this 5′ end was detected only when 3.2 mM sialic acid was added to the medium, lending additional support to the Northern blot results that indicated that nanE-nanA transcription is induced when sialic acid is present. A potential promoter recognition sequence was identified upstream of the start site of transcription (Fig. 6B), with five of six matches to the canonical −10 and −35 consensus C. perfringens housekeeping promoter recognition sequences (21).

FIG. 6.

(A) Primer extension results from RNA obtained from C. perfringens growing on PY medium with or without 3.2 mM sialic acid added. (B) Sequence of the nanE promoter region shown in panel A. The −10 and −35 promoter recognition sequences are shown in bold capitals. The initiator methionine codon of the nanE structural gene is shown in italic capitals.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we attempted to identify a C. perfringens manA locus by using a selection method based on the ability to complement a manA strain of E. coli with a plasmid gene bank. Instead, our selection led to the identification of a recombinant clone that carried nanE and nanA genes. The locations of the nanE and nanA gene products in the sialic acid metabolic pathways of C. perfringens are shown in Fig. 1. We do not fully understand why pDMW3 was identified in our original selection, but it could be that the epimerase and lyase enzymes affect mannose metabolic pathways in E. coli. We have not eliminated the possibility that the putative NAD(P)H nitroreductase or the partial coding regions played a role in the complementation experiments. The question of which gene(s) is responsible for complementing the manA mutation is under investigation in our laboratory.

We have unequivocally demonstrated that the C. perfringens nanA gene encodes a sialic acid lyase by both enzymatic and growth complementation studies (Table 2). An assignment for a potential function of the nanE gene product as an epimerase that converts N-acetylmannosamine-6-phosphate to N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate in E. coli has been made only very recently (17); we are now attempting to confirm this enzymatic activity for NanE in C. perfringens in our laboratory.

We propose that the nanE and nanA genes comprise an operon that is transcribed from a single promoter. This proposal is based on the results of the Northern blot experiments shown in Fig. 3, where a 1.5-kb transcript was detected with both nanE- and nanA-specific probes. If nanE and nanA are cotranscribed, this is the approximate length of transcript that would be expected. Two additional bands, 1.0 and 0.75 kb in length, were also detected with the nanA-specific probe, but we predict that these are the results of mRNA processing rather than alternative promoter sites. This is based on our inability, with plasmid pSM218 (Fig. 5), to detect significant levels of transcription from DNA fragments which should include any promoter that was present downstream of the start of the nanE coding region.

We detected low levels of probe hybridizing to longer mRNA species with the nanA-specific probe when sialic acid was added to the medium (Fig. 3B). However, we could not detect a hybridizing band in Northern blots with an ORF1-specific probe. In addition, a potential rho-independent terminator located 47 bp downstream of the nanA gene was identified (28). This may indicate that the longer transcripts include the upstream ORF encoding a protein with similarity to an NAD(P)H nitroreductase (Fig. 2), but at much lower levels than the nanE-nanA transcript. Interestingly, in E. coli the sialic acid transporter gene, nanT, is located immediately downstream of the nanA coding region in the chromosome (9). However, the partial sequence of C. perfringens ORF1 does not show any significant similarity to nanT of E. coli, and this gene is apparently transcribed under different conditions than those examined in this study. Nonetheless, this does not exclude this gene from encoding a permease that can also transport sialic acid by a mechanism other than that used by the E. coli NanT protein.

We have also demonstrated that transcription of the nanE-nanA operon is inducible by sialic acid by using two methods, Northern blot analysis (Fig. 3) and primer extension experiments (Fig. 6). This data supports an earlier observation that the enzyme activity of sialic acid lyase was inducible when substrates containing sialic acid were present in the medium (13). Transcription of the nanE-A operon is not catabolite repressed by the presence of glucose in the medium (Fig. 3), even though excess glucose is known to repress both sporulation and amylase synthesis in C. perfringens (24).

The use of a multicopy vector to detect regulation at the nanE promoter failed to show significant levels of transcriptional regulation in the presence of sialic acid (Fig. 5); i.e., there was a considerable level of transcription even in the absence of sialic acid. This could be due to multicopy effects; e.g., a high number of plasmids may titrate away a transcriptional repressor, thereby allowing unregulated transcription at the nanE promoter. The C. perfringens replication functions of plasmid pSM218 are derived from plasmid pIP404, which is estimated to exist at 10 to 15 copies per cell in C. perfringens (21). As additional indirect evidence for a repressor activity, the promoter that we identified as being transcriptionally regulated by sialic acid showed matches at five of six positions each to canonical −10 (TATAAT) and −35 (TTGACA) promoter recognition sequences for housekeeping genes in C. perfringens, as well as the optimum 17-bp spacer between these elements (Fig. 6B). This close match to the consensus may indicate that the promoter is transcribed unless a repressor is bound at the promoter region. Further work to identify the transcriptional regulator will help resolve this issue.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank E. Vimr for the gift of strain EV78 and helpful discussions.

This work was supported by NRICGP/USDA grant 96-0154, awarded to S.B.M.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bannam T L, Rood J I. Clostridium perfringens-Escherichia coli shuttle vectors that carry single antibiotic resistance determinants. Plasmid. 1993;229:233–235. doi: 10.1006/plas.1993.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blattner F R, Plunkett G R, Bloch C A, Perna N T, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner J D, Rode C K, Mayhew G F, Gregor J, Davis N W, Kirkpatrick H A, Goeden M A, Rose D J, Mau B, Shao Y. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang A C Y, Cohen S N. Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles derived from the P15A cryptic miniplasmid. J Bacteriol. 1978;134:1141–1156. doi: 10.1128/jb.134.3.1141-1156.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cherniak R, Frederick H M. Capsular polysaccharide of Clostridium perfringens Hobbs 9. Infect Immun. 1977;15:765–771. doi: 10.1128/iai.15.3.765-771.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corfield T. Bacterial sialidases—roles in pathogenicity and nutrition. Glycobiology. 1992;2:509–521. doi: 10.1093/glycob/2.6.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleischmann R D, Adams M D, White O, Clayton R A, Kirkness E F, Kerlavage A R, Bult C J, Tomb J F, Dougherty B A, Merrick J M, et al. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science. 1995;269:496–512. doi: 10.1126/science.7542800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fraser C M, Casjens S, Huang W M, Sutton G G, Clayton R, Lathigra R, White O, Ketchum K A, Dodson R, Hickey E K, Gwinn M, Dougherty B, Tomb J F, Fleischmann R D, Richardson D, Peterson J, Kerlavage A R, Quackenbush J, Salzberg S, Hanson M, van Vugt R, Palmer N, Adams M D, Gocayne J, Venter J C, et al. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochaete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature. 1997;390:580–586. doi: 10.1038/37551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jefferson R A, Burgess S M, Hirsh D. β-Glucuronidase from Escherichia coli as a gene-fusion marker. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:8447–8451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.22.8447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinez J, Steenbergen S, Vimr E. Derived structure of the putative sialic acid transporter from Escherichia coli predicts a novel permease domain. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6005–6010. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.20.6005-6010.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melville S B, Labbe R, Sonenshein A L. Expression from the Clostridium perfringens cpe promoter in C. perfringens and Bacillus subtilis. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5550–5558. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5550-5558.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mengaud J, Geoffroy C, Cossart P. Identification of a new operon involved in Listeria monocytogenes virulence: its first gene encodes a protein homologous to bacterial metalloproteases. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1043–1049. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.3.1043-1049.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meysick K C, Dimock K, Garber G E. Molecular characterization and expression of a N-acetylneuraminate lyase gene from Trichomonas vaginalis. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;76:289–292. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(95)02544-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nees S, Schauer R. Induction of neuraminidase from Clostridium perfringens and the correlation of this enzyme with acylneuraminate pyruvate-lyase. Behring Inst Mitt. 1974;55:68–78. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nees S, Schauer R, Mayer F. Purification and characterization of N-acetylneuraminate lyase from Clostridium perfringens. Hoppe-Seyler’s Z Physiol Chem. 1976;357:839–853. doi: 10.1515/bchm2.1976.357.1.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niilo L. Clostridium perfringens in animal disease: a review of current knowledge. Can Vet J. 1980;21:141–148. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Novel G, Novel M. Mutants of E. coli K 12 unable to grow on methyl-beta-d-glucuronide: map location of uidA. Locus of the structural gene of beta-d-glucuronidase. Mol Gen Genet. 1973;120:319–335. . (In French.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Plumbridge J, Vimr E. Convergent pathways for utilization of the amino sugars N-acetylglucosamine, N-acetylmannosamine, and N-acetylneuraminic acid by Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:47–54. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.1.47-54.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roggentin P, Kleineidam G, Schauer R. Diversity in the properties of two sialidase isoenzymes produced by Clostridium perfringens spp. Biol Chem Hoppe-Seyler. 1995;376:569–575. doi: 10.1515/bchm3.1995.376.9.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roggentin P, Rothe B, Lottspeich F, Schauer R. Cloning and sequencing of a Clostridium perfringens sialidase gene. FEBS Lett. 1988;238:31–34. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)80219-9. . 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roggentin P, Schauer R. Clostridial sialidases. In: Rood J I, McClane B A, Songer J G, Titball R W, editors. The clostridia: molecular biology and pathogenesis. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc.; 1997. pp. 421–437. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rood J I, Cole S T. Molecular genetics and pathogenesis of Clostridium perfringens. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:621–648. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.4.621-648.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schauer R. Chemistry, metabolism, and biological function of sialic acids. Adv Carbohydr Chem Biochem. 1982;40:131–234. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2318(08)60109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shih N J, Labbe R G. Characterization and distribution of amylases during vegetative cell growth and sporulation of Clostridium perfringens. Can J Microbiol. 1996;42:628–633. doi: 10.1139/m96-086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simons R W, Houman F, Kleckner N. Improved single and multicopy lac-based cloning vectors for protein and operon fusions. Gene. 1987;53:85–96. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Traving C, Roggentin P, Schauer R. Cloning, sequencing and expression of the acylneuraminate lyase gene from Clostridium perfringens A99. Glycoconj J. 1997;14:821–830. doi: 10.1023/a:1018585920853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vimr E R, Troy F A. Identification of an inducible catabolic system for sialic acids (nan) in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1985;164:845–853. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.2.845-853.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walters, D. M., and S. B. Melville. Unpublished data.

- 29.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;8:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zbiral E, Kleineidam R G, Schreiner E, Hartmann M, Christian R, Schauer R. Elucidation of the topological parameters of N-acetylneuraminic acid and some analogues involved in their interaction with the N-acetylneuraminate lyase from Clostridium perfringens. Biochem J. 1992;282:511–516. doi: 10.1042/bj2820511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao Y, Melville S B. Identification and characterization of sporulation-dependent promoters upstream of the enterotoxin gene (cpe) of Clostridium perfringens. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:136–142. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.1.136-142.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]