Abstract

Background

The most common and deadly cancer in female is breast cancer (BC) and new incidence and deaths related to this cancer are rising.

Aims

Several issues, that is, high cost, toxicity, allergic reactions, less efficacy, multidrug resistance, and the economic cost of conventional anti‐cancer therapies, has prompted scientists to discover innovative approaches and new chemo‐preventive agents.

Materials

Numerous studies are being conducted on plant‐based and dietary phytochemicals to discover new‐fangled and more advanced therapeutic approaches for BC management.

Result

We have identified that natural compounds modulated many molecular mechanisms and cellular phenomena, including apoptosis, cell cycle progression, cell proliferation, angiogenesis and metastasis, up‐regulation of tumor‐suppressive genes, and down‐regulation of oncogenes, modulation of hypoxia, mammosphere formation, onco‐inflammation, enzymatic regulation, and epigenetic modifications in BC. We found that a number of signaling networks and their components such as PI3K/Akt/mTOR, MMP‐2 and 9, Wnt/‐catenin, PARP, MAPK, NF‐κB, Caspase‐3/8/9, Bax, Bcl2, Smad4, Notch1, STAT3, Nrf2, and ROS signaling can be regulated in cancer cells by phytochemicals. They induce up‐regulation of tumor inhibitor microRNAs, which have been highlighted as a key player for ani‐BC treatments followed by phytochemical supplementation.

Conclusion

Therefore, this collection offers a sound foundation for further investigation into phytochemicals as a potential route for the development of anti‐cancer drugs in treating patients with BC.

Keywords: anti‐cancer mechanism, breast cancer, cancer treatment, natural products, phytochemicals, resistance

This review mainly focused the potential role of phytochemicals against breast cancer (BC) treatment with the molecular mechanism and cellular phenomenon. Altogether, this review also suggests that phytochemicals might be the good source to discover potential alternative and complementary chemotherapeutic agents for the treatment of BC due to their therapeutic advantages.

1. INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer (BC) is the most common and frequent malignancy among females, and it is the second most frequent carcinoma and a significant cause of cancer‐associated death worldwide. This cancer is a multifactorial disease and various factors, including demographic, oxidative stress, bacterial infection, reproductive, hormonal, hereditary, and lifestyle contribute to its occurrence. 1 A number of conventional therapeutic options such as surgical resection, radiotherapy, chemo‐radiotherapies (e.g., adjuvant chemotherapies and neoadjuvant therapy), hormonal therapies, monoclonal antibodies, immunotherapy, and small molecular inhibitors are available for the patients with BC. 2 , 3 However, these therapeutic modalities have drawbacks, bearing side effects and toxicities. Thus, new approaches and strategies are needed to manage patients with BC effectively to minimize the limitations, such as increasing resistance to conventional therapeutics, side effects, and toxicities of existing treatment modalities. Interestingly, alternative medicines (with fewer side effects) for patients with BC, especially metastatic cancer, have been developed.

Phytochemicals are an essential natural resource for anti‐cancer medicine. They are safe, non‐toxic, cost‐effective, and readily available sources from villages to cities and underdeveloped to developed countries. 4 Currently, medicinal plants or their derivatives account for about 70% of the anti‐cancer compounds, thus, playing the lead role in developing anti‐cancer drugs. 5 , 6 Initially, natural plant extracts have showed higher anti‐tumor responses and better pharmacological or bioactivity with less toxicity in patients with advanced BC (Table 1). 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 For example, anti‐cancer compounds from Curcuma longa, Piper longum, Nigella sativa, Murrayakoenigii, Amora rohituka, Withania somnifera, and Dimocarpus longan possess anti‐cancer activity against various cancers, especially anti‐BC properties. 8 , 25 , 36 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 Latter specific phytochemicals have been identified as a new source of anti‐cancer agents from plant extract to decrease the negative effects of cancer chemotherapies in recent research. 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 These natural agents can target several BC‐related pathways and provide protective activity against breast malignancies, which play a significant role in preventing and managing patients with BC. 46 , 49 Several individual studies exhibited phytochemicals had anti‐cancer property through several mechanisms. 50 , 51 , 52 However, a comprehensive summary on precise anti‐cancer mechanisms including apoptosis induction, cell cycle, and cell proliferation regulation, inhibition of angiogenesis and metastasis, regulating hypoxia‐inducible factor, suppressed mammosphere formation, onco‐inflammation inhibition, controlling enzyme activity, signal transduction regulation, epigenetic and immune regulation have not been reported collectively. Therefore, in this review, we have discussed various phytochemicals with their major sources, structure, and their possible anti‐cancer pathways in the BC, thereby providing an aggregative source of information on potential natural anti‐cancer resources.

TABLE 1.

Summary of plants extract and their anti‐cancer activity in human breast cancer cell line.

| Source/plant | Parts used | Working protocol | Anti‐cancer mechanism | Efficacy/dose | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methods | Extract used | Cell line | |||||

| Ailanthus altissima | Bark | Flow cytometry, RT‐PCR, western blot | Petroleum, dichloromethane | MCF‐7 |

↓ Cell proliferation ↑ Cell cycle arrest, apoptosis |

0.5–8.0 μg/mL | 7 |

| Amoora rohituka | Leaf | FTIR analysis, phytochemical screening methods | Petroleum ether, ethyl acetate, methanol | MCF‐7 |

↓ Cell migration ↑ Apoptosis ↑ Cytotoxic effect |

9.81 mg/mL | 8 |

| Ardisia crispa | Leaves | MTT assay, DPPH, ABTS assay | Ethyl acetate, aqueous | MCF‐7, MDA‐MB‐231 | ↓ Glucose uptake | 57–100 μg/mL | 9 |

| Baeckea frutescens | Leaves extracts | Cytotoxity, glucose consumption assay | Ethanol, aqueous | MCF‐7 MDA‐MB‐231, MCF10A |

↓ Cell viability, cell motility ↑ Cell cycle arrest, apoptosis |

53 μg/mL | 10 |

| Bryonia dioica | Roots | Extracted, flow cytometry, staining, western blot | Aqueous | BL‐41 |

↑ Cell cycle arrest, apoptosis |

15–63 g/mL | 11 |

| Bulbine frutescens | Bulb | Membrane potential, ROS, Notch promoter, western blot | Methanol, hexane | MDA‐MB‐231, T47D | ↑ Cell cycle arrest, DNA repair, scavenge free radical | 4.8–28.4 μg/mL | 12 |

| Butea monosperma | Bark fractions | MTT, clonogenic, neutral comet assay, flow cytometry | Methanol, hexane, chloroform, ethyl acetate | MCF‐7 | ↑ Inhibit proliferation, cell cycle arresting effect | 44–213 mg/mL | 13 |

| Cimicifuga dahurica | Rizhomes | Extraction NMR, BrdU | 70% ethanol | MCF‐7 |

↓ Oncogene expression cell proliferation ↑ Apoptosis induction |

30 μM | 14 |

| Decatropis bicolor | Leaves | MTT assay, cell morphology analysis, western blot | Water, ethanol, acetone, hexane |

MDA‐MB‐231 |

↑ Apoptosis induction | 53.81 μg/mL | 15 |

| Fagonia indica | flower | Cytotoxicity, PARP, DNA fragmentation assay | EtOH | MCF‐7, MDA‐MB‐468 | ↑ Apoptosis | 50–100 μM | 16 |

| Garcinia oblongifoli | Fruits, leaves | Cell viability, antioxidant | Methanol | MCF‐7 | ↑ Cytotoxic effect | 1000 μg/mL | 17 |

| Glycyrrhiza glabra | Root | qRT‐PCR, western blots, DNA methylation analysis, immunostaining | Glabridin | Multiple cell line | ↑ Anti‐tumor activity | 0 or 20 mg/kg | 18 |

| Hedyotis diffusa | Leaves and shoots | Mitochondrial membrane potential, western blot | Methylanthraquinone | MCF‐7 |

↓ Cell growth ↑ Apoptosis |

18.62 μM | 19 |

| Lawsonia nermis | Leaves | Chromatography, dynamic light scattering, UV–Vis spectroscopy | Alcoholic solution | MCF‐7 | ↑ Apoptosis, autophagy | 1.5 μM | 20 |

| Lotus corniculatus | Leaves | MTT, PCR, wound healing assay | Ethyl acetate, methanol, water | MDA‐MB‐231, MCF‐7 | ↓ Cell migration, cancer‐related enzymatic activity | 21.13 mg RE/g | 21 |

| Lycium barbarum | Fruit | Signaling mechanism test | NA | MCF‐7 cells | ↓ Cancer‐related signaling, hypoxia condition | 0.50 mg/mL | 22 |

| Malus domestica | Fruit | Western blot, cell cycle analysis | Acetone | MCF‐7, MDA‐MB‐231 | ↓ Enzyme activity, cell growth | 10–80 mg/mL | 23 |

| Morus alba | Leaves | Anti‐proliferative radical scavenging assay | Methanol | MCF‐7 |

↑ Morphology change ↓ Cell proliferation |

350 μg/mL | 24 |

| Nigella sativa | Seed | UV–visible spectroscopy, FT‐IR, SEM, EDX | Aqueous | MCF‐7 |

↑ Apoptosis ↓ Migration, adhesion, metastasis |

1–200 μg/mL | 25 |

| Platycodon grandiflorus | Root | Cytotoxicity, flow cytometry, western | Platycodin D | MCF‐7 | ↑ Apoptosis | 8 μg/mL | 26 |

| Premna odorata | Leaves | NMR, extraction, molecular modeling, proliferation, migration assay | 70% ethanol | MCF‐7, BT‐ 474 | ↑ Cytotoxicity activity | 13.3 μM | 27 |

| Rabdosiae rubescens | Whole part | Western blot analysis, immunohistochemistry analysis | Ethanol, water extract |

MDA‐MB‐231 In vivo |

↓ Growth migration, apoptosis | 12 μg/mL | 28 |

| Salpichroascandens | Aerial parts | Extraction, cytotoxicity assay | Dichloromethane | MCF‐7, T47D | ↓ Growth, cytotoxic activity | 29–646 μM | 29 |

| Salvia sclarea | Plant | In vivo mice | n‐hexane/ethylacetate/methanol (1:1:1) | MCF‐7, T47D, ZR‐75‐1 | ↑ Anti‐proliferative, cytotoxicity activity | 7.85 μg/day | 30 |

| Salvia species | N/A | Sulforhodamine B assay, chromatography | Ethanol | T47D, ZR‐75‐1, BT 474 | ↓ Aromatase enzyme | 30 μg/mL | 31 |

| Schisandra chinensis | Seeds, leaves, and stems | Western blotting, Immunohistochemistry | Schisandrin A | MDA‐MB‐ 231, BT‐549 | ↑ Apoptosis induction, cell cycle arrest, cell cytotoxicity | 134.21 ± 6.85 μM | 32 |

| Scrophularia variegat | Aerial parts | MTT assay, ELISA, annexin V‐FITC/PI staining | Ethanol | MCF‐7 | ↑ Apoptosis induction, cell cycle arrest | 31–299 mg/L | 33 |

| Scutellaria baicalensis | Root | HPLC, staining | Ethanol, ethyl acetate, 1‐butanol, water | MCF‐7 |

↑ Cytotoxicity ↓ Hypoxic conditions |

100 mg/mL | 34 |

| Senecio graveolens | Flower, leaves, stems | Extraction, cytotoxic assays, western blot | Ethanol | ZR‐75‐1, MDA‐MB‐ 231 |

↑ Cell death, cell cycle arrest ↓ Proliferation |

200 μg/mL | 35 |

| Withania somnifera | N/A | Flow cytometry, microarray data analysis, PCR, invasion assay, western blotting | 70% ethanol | MDA‐MB‐ 231, MCF‐7 | ↑ Apoptosis induction, cell cycle arrest | 853.6 nM | 36 |

2. SOURCE OF ENLISTED DIETARY PHYTOCHEMICAL

Phytochemicals are plant‐based compounds founds in vegetables, fruits, beans, grains, and other parts of plants. Bioactive phytochemicals protect cells from cancer‐causing injury. 53 For instance, daidzein, genistein, epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), epigallocatechin, and formononetin‐A are phytoestrogen in nature and found in the form of flavonoids in soy and soy products. 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 Lutein, 3,3‐Diindolylmethane, benzyl isothiocyanate, kaempferol, and quercetin are available in green leafy vegetables including spinach, broccoli, peas, and herbs such as dill, chives, onion, leeks, and egg yolks. 9 , 58 , 59 , 60 In addition, vegetables such as tomatoes, potatoes, and fruits such as citruses, watermelon, apples, pink guava, pink grapefruit, papaya, passion flower fruit, and dried apricots, are the significant source of 2‐hydroxychalcone, 61 lycopene, 62 naringenin. 63 Also, natural compounds such as nimbolide, sanguinarine, withaferin A, α‐Mangostin, arctigenin, calycosin, curcumin, and flavopiridol are present abundantly in medicinal plants such as Azadirachta indica (leaves and seed), Sanguinaria canadensis (rhizome), W. somnifera, Tripterygium wilfordix (roots), Garcinia mangostana L.(pericarps), Arctium lappa L. (seeds), Radix astragali (dry root), C. longa (rhizome), and Dysoxylum binectariferum (stem and bark), respectively. 36 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 Furthermore, punicalagin, sesamin, shikonin, silibinin, taiwanin A, and wogonin are found in Punica granatum, Cuscuta palaestina (seed), Sesamum indicum, Lithospermum erythrorhizon (roots), Silybum marianum, Taiwania cryptomerioides (bark), N. sativa (seeds), and Anodendron affine (stems) plants. 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 EGCG, and epigallocatechin are known catechin phytochemicals, widely distributed in tea with several health benefits. 75 , 76 The source and structure of these phytochemicals are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Source and structure of common phytochemicals with anti‐cancer properties.

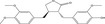

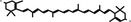

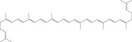

| Compounds | Structure | Source | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2‐Hydroxychalcone |

|

Tomatoes, potatoes, licorice, citruses, apples (Humulus lupulus L.) | 61 |

| 3,3‐Diindolylmethane |

|

Cruciferous vegetables, that is, brussels sprouts, cauliflower, cabbage, and broccoli | 59 |

| Apigenin |

|

Parsley, chamomile, celery, vine‐spinach, and oregano | 77 |

| Arctigenin |

|

Present in the seeds of Arctium lappa L. | 67 |

| Benzyl isothiocyanate |

|

Cruciferous vegetables like 3,3‐diindolylmethane source | 9 |

| Calycosin |

|

Dry root extract of Radix astragali | 68 |

| Celastrol |

|

The root extract of Tripterygium wilfordi plant | 78 |

| Coumestrol |

|

Clover, Kala Chana, Alfalfa sprouts | 79 |

| Curcumin |

|

Rhizome of turmeric (Curcuma longa) | 80 |

| Daidzein |

|

Soybeans and soy products, that is, beans, peas, nuts, coffee, tea, and specific herb like red clover | 54 |

| EGCG |

|

Green tea | 81 |

| Emodin |

|

Herbs, that is, Polygonum cuspidatum, Aloe vera, Rheum palmatum, and Cassia obtusifolia | 82 |

| Enterolactone |

|

Flaxseed, sesame seed | |

| Epigallocatechin |

|

Green tea | 83 |

| Flavopiridol |

|

The stem and bark of Dysoxylum binectariferum plant | 84 |

| Formononetin |

|

Red clovers, soya bean, milk vetch (Astragalus mongholicus) | 55 |

| Genistein |

|

Soybeans and soy products | 56 |

| Ginsenoside Rh1 |

|

Red ginseng, root | 85 |

| Ginsenosides |

|

Panax species (roots, leaves, stems, flower, fruits) | 86 |

| Isoliquiritigenin |

|

Licorice, extract of Sinofranchetia chinensis | 87 |

| Kempferol |

|

Green leafy vegetables such as broccoli, spinach, and kale, and herbs such as dill, chives, and tarragon, onion, leeks | 60 |

| Lutein |

|

Green leafy vegetables such as broccoli, spinach peas, lettuce, and egg yolks | 58 |

| Lycopene |

|

Tomato, watermelon, pink guava, papaya, pink grapefruit, and dried apricots passionflower fruit | 62 |

| Naringenin |

|

Fruits like citrus species and tomatoes | 63 |

| Nimbolide |

|

Leaves and flowers of neem (Azadirachta indica) | 64 |

| Pharbilignan C |

|

Pharbitidis semen, the seed of morning glory (Pharbitis nil) | 88 |

| Pterostilbene |

|

Blueberries, grapes, and tree wood | 89 |

| Punicalagin |

|

Pomegranate (Punica granatum) | 69 |

| Quercetin |

|

Nuts, apples, onions, olive oil green tea, broccoli, red grapes, dark cherries | 90 |

| Sanguinarine |

|

Rhizome of bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis) | 65 |

| Withaferin A |

|

Withania somnifera | 36 |

| α‐Mangostin |

|

Pericarps of mangosteen | 66 |

| Resveratrol |

|

Grapes, peanuts, and soy | 57 |

| Rg3 |

|

Red ginseng root (Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer) | 91 |

| Rosmarinic acid |

|

Boraginaceae species and Nepetoideae of the Lamiaceae subfamily | 92 |

| Sesamin |

|

Sesame seeds, Cuscuta palaestina plant extract | 48 |

| Shikonin |

|

Roots of Lithospermum erythrorhizon | 93 |

| Silibinin |

|

Silybum marianum plant | 72 |

| Sulforaphane |

|

Broccoli, cauliflower, radish, cabbage and arugula | 94 |

| Taiwanin A |

|

Bark of Taiwania cryptomerioides | 73 |

| Thymoquinone |

|

Nigella sativa (seeds) | 95 |

| Wogonin |

|

Scutellaria baicalensis (dried root), Scutellaria rivularis, Andrographis paniculata (wall, leaves) | 74 |

| Oxymatrine |

|

Sophora flavescens (quinazine alkaloid extracted) | 96 |

| Jasmonates |

|

Camellia sasanqua L., Camellia sinensis L. (anther and pollen) | 97 |

| Fisetin |

|

Fragaria ananassa, Malus domestica (fruit) | 98 |

3. PHYTOCHEMICALS TARGETING BC CELLS

Therapeutic strategies against BC include surgery chemoradiotherapies, adjuvant/neoadjuvant therapies, hormonal therapies, monoclonal antibodies, immunotherapy, nanomedicines, and small molecular inhibitors. 99 However, limitations such as resistance, compromised efficacy, and side effects of conventional therapies limit their clinical applications. Thus, plant‐derived anti‐cancer agents with less or no toxic effects can be an alternative chemotherapeutic option. Anti‐cancer activity of phytochemicals is dependent on their multi‐targeted mechanism of action. Since carcinogenesis is a multistep process involving multiple signaling mechanisms, numerous phytochemicals targeting the altered signaling in cancer are considered promising anti‐cancer therapeutics. 100 Phytochemicals targeting signaling pathways in cancer are summarized (Table 3). The following sections outline the role of potentially bioactive compounds against BC cells with their possible molecular mechanism.

TABLE 3.

Summary of selected particular phytochemical and their anti‐cancer activity in human breast cancer cell line.

| Phytochemical | Dose | Study type | Target | Macular mechanism | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effects of phytochemicals on cell proliferation | |||||

| Formononetin‐A | 25 μM | MCF‐7 and MDA‐MB‐231 |

↓ Tumor growth ↓ Angiogenesis |

↓ FGFR2‐mediated Akt signaling | 101 |

| Sesamin | 100 μM | MCF‐7 | ↓ Proliferation | ↓ Cyclin D1 expression | 102 |

| Curcumin | 1.25–5 mg/mL | MDA‐MB‐231 and BT‐483 cell | ↓ Proliferation | ↓ NF‐κB, and more importantly cyclin D1, CDK4 MMP1 mRNA | 103 |

| Genistein | 40–100 μM | MCF‐7 | ↓ Proliferation |

↓ IGF‐1R‐PI3K/Akt ↓ Bcl‐2/Bax mRNA |

45, 104 |

| Lycopene | 100 μM | MDA‐MB‐468 |

↓ Proliferation ↑ Apoptosis |

↓ Akt, mTOR ↑ Bax |

105 |

| Rosmarinic acid | 20 μmol/L | MCF‐7 | ↓ Proliferation | ↓ COX‐2 expression, AP‐1 activation, and antagonized the ERK1/2 activation | 106 |

| Silibinin | 50–200 μmol | MCF‐7 |

↑ Apoptosis ↓ Proliferation |

↓ Bcl‐xl ↑ p53, p21, BRCA1, Bak, ATM |

107 |

| Apigenin | 30 μM | MDA‐MB‐468 | ↓ Proliferation |

↑ ROS production ↓ p‐Akt |

108 |

| Enterolactone | 75 μM | MDA‐MB‐231 |

↓ Proliferation ↓ Migration |

↓ PA‐induced plasmin activation ↓ MMP‐2 and MMP‐9 |

109 |

| Effects of phytochemicals on apoptosis induction | |||||

| Ginsenoside Rh1 | 50 μM |

In vitro MCF‐7, HCC1428 |

↑ Apoptosis, autophagy |

↓ ROS‐mediated PI3K/Akt pathway ↑ ROS production ↑ LC3B and cleaved caspase‐3 |

110 |

| Daidzein | 25–100 μM |

In vitro MCF‐7 |

↑ Apoptosis |

↑ Bax, cyt c, caspases 9 and 3 ↓ Bcl‐2 |

111 |

| Nimbolide | 1.97–5 μM |

In vitro MDA‐MB‐231 MCF‐7 |

Apoptosis autophagy |

↓ Bcl2, mTORp62 Beclin 1, LC3B protein |

112 |

| Lycopene | 2–16 μM |

In vitro MCF‐7 |

↓ Proliferation ↑ Apoptosis |

↑ p53 and Bax | 113 |

| Pharbilignan C | 5–20 μM |

In vitro MDA‐MB‐231 |

↑ Apoptosis |

↑ Bax, caspases 9 and 3 ↓ Bcl‐2 |

88 |

| EGCG | 0–80 μM |

In vitro T47D |

↑ Apoptosis |

↓ Telomerase and P13K/AKT ↑ Bax/Bcl‐2, CASP3, CASP9, and PTEN |

83 |

| Sanguinarine | 0–1.5 μM |

In vitro MDA‐MB‐231 |

↑ Apoptosis |

↑ ROS generation ↑ cytochrome c ↑ caspase‐3 and caspase‐9 ↓ XIAP, cIAP‐1 |

114 |

| Lutein | N/A |

In vivo BALB/c mice |

↑ Apoptosis ↓ angiogenesis |

↑ p53 and Bax ↓ Anti‐apoptotic gene, Bcl‐2 |

115 |

| Kaempferol | 20–80 μM |

In vitro MCF‐7 cells |

↑ Apoptosis |

↑ PARP cleavage, Bax ↓ Bcl‐2 |

116 |

| Emodin | 40 μM |

In vitro Bcap‐37 and ZR‐75‐30 |

↓ Growth ↑ Apoptosis |

↑ Cleaved caspase‐3, PARP, p53 ↑ Bax/Bcl‐2 ratio |

117 |

| Withaferin A | 2.5–5 μM |

In vitro MDA‐MB‐231 and MCF‐7 |

↑ Apoptosis |

ROS production, Bax and Bak mitochondrial membrane potential |

118 |

| Celastrol | 1–10 μM |

In vitro MDA‐MB‐231 and MCF‐7 |

Apoptosis |

↑ TNF‐α, caspase‐8, caspase‐3, PARP cleavage ↓ Cellular cIAP1 and cIAP2, FLIP, Bcl‐2 |

119 |

| Effects of phytochemicals on cell cycle regulator | |||||

| Quercetin | 5–20 μM |

In vitro MCF‐7 |

↓ Cell cycle progression |

↓ Cdc2‐cyclin B1 ↑ p21CIP1/WAF1 |

120 |

| Taiwanin A | 5 μg/mL |

In vitro MCF‐7 |

↑ DNA damage ↑ Cell cycle arrest at G(2)/M ↑ Apoptosis |

↑ p53, p‐p53, p21, p27 | 121 |

| Coumestrol | 50 μM |

In vitro MCF‐7 |

↑ G1/S phase arrest | ↑ CDKI p21 and p53 | 122 |

| Ginsenosides | 100 μM |

In vitro MCF‐7 |

↓ Proliferation |

↓ CDK4, cyclin E2, cyclin D1 ↑ p21WAF1/CIP1, p53 p15INK4B |

123 |

| Kaempferol | 10–6 μM |

In vitro MCF‐7 |

↓ Proliferation ↑ Apoptosis |

↓ Capthepsin D, cyclin E and cyclin D1 ↑ Bax and p21 |

124 |

| Thymoquinone | 100–200 μM |

In vitro MCF‐7, T47D, MDA‐MB231 |

↓ Proliferation, viability | ↓ Cyclin D1, cyclin E, p27, survivin | 125 |

| Naringenin | 0.05–4 μM |

In vitro HTB26 and HTB132 |

↓ Cell growth ↑ Cell cycle arrest at S‐ and G2/M‐phases ↑ Apoptotic cell death ↓ Cell survival factors |

↑ p18, p19, p21 ↓ Cdk4, Cdk6, Cdk7, NF‐κB p65 |

126 |

| Effects of phytochemicals on angiogenesis and metastasis | |||||

| Shikonin | 5 μM |

In vitro MCF‐7 |

↓ Migration and invasion |

↓ MMP‐9 |

127 |

| Flavopiridol | 70 nM | MDA‐MB‐231 | ↓ Metastasis | ↓ MMPs 2 and 9, c‐erbB‐2 | 128 |

| Silymarin | 100 μg/mL | MCF‐7 and MDA‐MB‐468 | ↓ Migration and invasion | ↓ VEGF secretion, MMP‐9, AP‐1 activation | 129 |

| Curcumin | 20–100 μM | MCF‐7 | ↓ Metastasis and migration | ↓ uPA, NF‐κB activation | 130 |

| Arctigenin | 10–200 μM | MCF‐7 and MDA‐MB‐231 | ↓ Cell migration | ↓ MMP‐9, urokinase‐type plasminogen activator | 131 |

| 2‐hydroxychalcone and xanthohumol | 4.6–18.1 μM | MDA‐MB‐231 | ↓ Invasive phenotype |

↓ MMP‐9 ↓ Bcl‐2 |

132 |

| Enterolactone | 25–5 μM | MDA‐MB‐231 cells | ↓ Migration and invasion |

↓ MMP‐2 and MMP‐9 expressions ↑ MMPs inhibitor |

109 |

| Quercetin | 34 mg/kg | MCF‐7 | ↓ Angiogenesis | ↓ VEGF, VEGFR2, NFATc3, calcineurin pathway | 133 |

| Rg3 | 5 mg/kg Rg3, 1 time/2 day | MCF‐7 | ↓ Invasion and angiogenesis | ↓ MMP‐2, MMP‐9, VEGFA, VEGFB, VEGFC, p62, Beclin‐1, P13K, mTOR, Akt and JNK | 134 |

| Sulforaphane | 10 μM | MCF10 | ↓ Migration, invasion | ↓ TNF‐α, MMP‐2, MMP‐9, MMP‐13 | 135 |

| Silibinin | 50 μg/mL |

MDA‐MB‐468 xenograft model |

↓ Metastasis and migration ↓ Tumor volume |

↓ EGFR phosphorylation VEGF, MMP‐9, and COX‐2 |

136 |

| Isoliquiritigenin | 25–50 μM | MDA‐MB‐231 |

↓ Migration ↓ Angiogenesis |

↓ VEGF, HIF‐1α, MMP‐2, MMP‐9 ↓ p38, Akt, NF‐κB, P13K |

137 |

| Thymoquinone | 100 μL | MCF7 and MDA‐MB‐231 | ↓ Migration, invasion |

↑ TGF‐b, E‐cadherin, cytokeratin 19 ↓ MMP‐2, MMP‐9, Ysnail, Twist, Smad2, NF‐κB |

138 |

| Punicalagin | N/A | MDA‐MB‐231 | ↓ Invasion and angiogenesis |

↓ VEGF expression ↑ MIF regulation |

139 |

| Effects of phytochemicals on hypoxia‐inducible factor | |||||

| EGCG | 50–100 mg/kg/day for 4 weeks |

In vivo C57BL/6 J mice |

↓ Growth ↓ Migration ↓ Angiogenesis ↓ Proliferation |

↓ HIF‐1α ↓ NFκB and VEGF expression |

140 |

| Isoliquiritigenin | 25–50 μM |

In vitro MDA‐MB‐231 |

↓ Proliferation | ↓ HIF‐1α | 137 |

| 3,3‐Diindolylmethane | 50 μM |

In vitro MDA‐MB‐231 |

↓ Angiogenesis |

↓ Furin, glucose transporter‐1 ↓ VEGF, enolase‐1 ↓ Phosphofructokinase in hypoxic |

141 |

| Lyciumbarbarum polysaccharides | 0.50 mg/mL |

In vitro MCF‐7 |

↓ Angiogenesis | ↓ HIF‐1α mRNA levels | 22 |

| Wogonin | 40 μM |

In vitro and vivo MCF‐7, MDA‐MB‐231 Xenograft mouse |

↓ Angiogenesis |

↑ HIF‐1α degradation ↓ HIF‐1α protein aggregation and translation ↓ Hsp90 client proteins EGFR, Cdk4, and survivin |

142 |

| Effects of phytochemicals on mammosphere formation | |||||

| Pterostilbene | 25–50 μM | MCF‐7 |

↓ bCSCs ↓ Mammospheres |

↓ CD44, hedgehog, Akt, GSK3b signaling, cyclin D1, c‐Myc ↑ β‐Catenin |

143 |

| Sulforaphane | 50 mg/kg | SUM‐149 and SUM‐159 Y |

↓ bCSCs ↓ Mammospheres |

↓ NF‐κB p65 subunit, p52 | 144 |

| Benzyl isothiocyanate | 3 μmol/g | MDA‐MB‐231, MCF‐7 and SUM159 |

↓ bCSCs ↓ Mammospheres |

↓ Ron, sfRon, ALDH1 ↑ SOX‐2, Nanog, [Oct‐4] |

145 |

| Resveratrol | 100 mg/kg/day | MCF‐7, SUM159 |

↓ bCSC proliferation ↓ Mammospheres |

↓ Wnt, β‐catenin | 146 |

| Curcumin | 5 μM | MCF‐7, MCF10A, SUM149 | ↓ bCSCs self‐renewal | ↓ SCD, CD49f, LDH1A3, TP63 | 147 |

| EGCG | 40 μM | MDA‐MB‐231 and MDA‐MB436 | ↓ bCSCs growth | ↓ ER‐a36, MAPK/ERK, EGFR, PI3K/AKT | 148 |

| Effects of phytochemicals on inflammation | |||||

| Pomegranate juice | 20–80 μmol/L |

ApoE‐KO mice J774.A1 macrophage |

↓ Pro‐inflammatory state |

↓ TNF‐α and IL‐6 secretion ↑ IL‐10 |

149 |

| Curcumin | 10–20 μM |

In vitro MCF‐7 |

↓ Inflammation ↓ Cell proliferation ↑ Apoptosis |

↑ Blocked the TNF‐α‐induced NF‐κB ↓ Proteasomal activities |

150 |

| Resveratrol | 10 ppm |

In vivo Sprague Dawley rats |

↑ Cell cycle arrest at S‐G(2)‐M phase ↓ Ductal carcinoma |

↓ NF‐κB, cyclooxygenase‐2, and matrix metalloprotease‐9 expression | 151 |

| Resveratrol, EGCG, curcumin | – |

In vivo Sprague Dawley rats |

↑ Pro‐inflammatory mediators in macrophage ↓ Stearic acid‐mediated activation |

↓ TNF‐α, IL‐1β, COX‐2, phospho‐Akt, phospho‐p65, NF‐κB | 152 |

| Effects of phytochemicals on enzymatic activity | |||||

| Curcumin | 20 μM |

In vitro MCF‐7 |

↓ GSTP1 methylation | ↑ Glutathione S‐transferase Pi 1 | 153 |

| Resveratrol | 25 μM |

In vitro MCF‐7 |

↑ Enzymatic inhibition |

↓ Aromatase mRNA expression ↓ CYP19 promoters activity and II transactivation |

154 |

| Sulforaphane | 25 μM |

In vitro MCF10A |

Block signaling pathways |

↓ COX‐2 expression ↓ ERK1/2‐IKK and NAK‐IKK |

155 |

| Rosmarinic acid | 10 μmol/L |

In vitro MCF10A |

↓ Pro‐inflammatory gene ↓ Cell proliferation |

↑ AP‐1 activation ↓ COX‐2 expression |

106 |

| Silibinin | 200 μM |

In vitro MCF‐7 and MDA‐MB231 |

↓ Cell viability ↓ Tumor inducing genes |

↓ COX‐2 expression ↓ TPA‐arbitrated MMP‐9 expression |

156 |

| Isoliquiritigenin | 10–40 μM |

In vitro MDA‐MB‐231, BT‐549 |

↓ Metastasis ↑ Apoptosis |

↓ COX‐2, CYP 4A activity ↓ PGE2, PLA2 expression and activity |

157 |

| Quercetin and epigallocatechin | 0.01–500 μM and 0.01–1000 μM |

In vitro MCF‐7 and MDA‐MB231 |

↓ Metabolic process |

↓ Glucose uptake ↓ Lactate production |

158 |

| Effects of phytochemicals on cell signaling pathways | |||||

| Genistein | 100 μM | MCF‐7 and MCF‐7 HER2 | Signal inhibition |

↓ IκBα, p65 nucleus phosphorylation ↓ NF‐ŚB transcription |

159 |

| Formononetin | 10–100 μM | MCF‐7 |

↓ Proliferation ↓ Cyclin D1 mRNA expression |

↓ IGF1/IGF1R‐PI3K/Akt phosphorylation | 160 |

| Calycosin | 0–100 μM | MCF‐7, T‐47D, MDA‐231 and MDA‐435 | ↓ Growth and induce apoptosis | ↓ IGF‐1R, MAPK, (PI3K)/Akt pathways | 161 |

| Arctigenin | 200 μM | MCF‐7, MDA‐MB‐231 | ↓ Metastasis |

↓ Akt, NF‐κB phosphorylation ↓ MAPK (ERK 1/2 and JNK 1/2) signaling |

. 131 |

| Resveratrol | 100 mg/kg | MCF‐7 |

↑ Autophagy ↑ Cytotoxicity |

Wnt/β‐catenin | 146 |

| Apigenin | 50 μM | MCF‐7/HER2 and MCF‐7 vec |

↑ Apoptosis ↓ Proliferation |

↓ p‐JAK1, p‐STAT3, NF‐κB, p‐IκBa | 162 |

| Silibinin | 50 μM | MDA‐MB‐231 | ↑ Apoptosis | ↓ ERK, Akt, Notch‐1 | 163 |

| Pterostilbene | 0–100 μM | MDA‐MB‐468 |

↑ Apoptosis ↓ Proliferation |

↑ ERK1/2 ↓ p21, YAkt, mTOR |

164 |

| Naringenin | 250 μM | MCF‐7 |

↑ Apoptosis ↓ Proliferation |

↓ P13K, MAPK, ERK1/2, AKT | 165 |

| α‐Mangostin | 30 μM | T47D, MDA‐MB‐468, SKBR3, and AU565 |

↑ Apoptosis ↓ Proliferation |

↓ P13K, ERK1/2, ERa, Akt, ERK1/2, MAPK ↑ p‐p38, p‐JNK1/2 |

166 |

| Effects of phytochemicals on epigenetic regulator | |||||

| Genistein | 80 μM |

In vitro MDA‐MB‐231 |

↑ Epigenetic stability |

↑ p21WAF1 (p21) and p16INK4a ↓ BMI1 and c‐MYC expression |

167 |

| Lycopene | 3.125 μM, 2 μm/week) |

In vitro MCF‐7 and MDA‐MB‐468, MCF10A |

↑ Epigenetics stability |

↑ Demethylases the GSTP1, RARbeta2 and the HIN‐1 genes |

168 |

| Curcumin | 40 μM |

In vitro MDA‐MB‐361 |

↓ Cell growth ↑ Repression tumor suppressor gene |

↓ Sp1 expression, DLC1 methylation | 169 |

| EGCG | 15 μM |

In vitro MCF7 and MDA MB 231 |

↓ Cell viability | ↓ RARb2, cyclin D2 methylation, TMS1 methylation, MGMT methylation | 170 |

| Sulforaphane | 5 μM |

In vitro MDA‐MB‐231 |

↑ Cell death ↓ Proliferation |

↓ HDAC demethylation | 171 |

3.1. Inhibition of cell proliferation

Cellular proliferation is essential for all multicellular organisms to develop bodies and organs during embryogenesis. However, in the case of cancer, abnormal cell proliferation is due to changing the expression or activity of protein associated with cell proliferation or cell cycle regulation. Phytochemicals and their derivatives can inhibit the growth and expansion of BC cells by targeting cell cycle regulatory proteins. 172 For example, the naturally active compound formononetin (25 μΜ) suppresses tumor growth and angiogenesis in MCF‐7 and MDA‐MB‐231 tumor models by targeting the FGFR2‐mediated Akt signaling pathway. 101 Treatment of MCF‐7 cells by silibinin (50–200 μmol) prevented cell proliferation through modulating the expression of apoptosis‐related proteins such as Bcl‐xl, bak, p53, p21, 107 whereas sesamin (100 μM) could inhibit MCF‐7 cell proliferation by down‐regulating cyclin D1 expression. 102 Curcumin mediated its anti‐proliferative activity against BC (MDA‐MB‐231 and BT‐483) cells by regulating the expression of NF‐κB, cyclin D1, CDK4, and MMP1. 103 Chen et al. noted that Genistein (40–100 μM) exhibited anti‐proliferative activity by deactivating the IGF‐1R‐PI3K/Akt signaling pathway along with increasing Bax/Bcl‐2 expressions in MCF‐7 cells, 104 whereas lycopene showed similar activities by increasing Bax expression without changing Bcl‐xL in MDA‐MB‐468 cancer cells. 105 Scheckel KA reported that the anti‐proliferative activity of rosmarinic acid (20 μmol/L) is associated with a decrease in COX‐2 expression and activation of AP‐1 and ERK1/2 in MCF‐7 cells. 106 Harrison et al. reported that apigenin arrests the cell cycle at the G2/M phase, followed by down‐regulation p‐Akt in MDA‐MB‐468 cancer cells. 108 Furthermore, enterolactone (ENL) has been shown to suppress cell proliferation by lowering uPA‐mediated plasmin activation and down‐regulation of MMP‐2 and MMP‐9 in MDA‐MB‐231 cells. 109 Therefore, phytochemicals could act as potent inhibitors of cell proliferation in BC cells by suppressing cell survival signaling, cell cycle regulatory protein, and regulating apoptosis‐related proteins.

3.2. Apoptosis inductions

Apoptosis, a programmed cell death mechanism, plays a crucial role in cancer pathogenesis and maintenance by regulating cell death and survival based on specific signals. 173 Apoptosis can be executed via two mechanisms, that is, the extrinsic and intrinsic mitochondrial pathways. 174 Both of these pathways are regulated through several regulatory proteins. 175 The extrinsic pathway, for instance, is associated with the Fas ligand, Fas‐associated protein with death domain initiator pro‐caspase‐8, and many caspases contributing to the cascade amplification. 176 In contrast, the intrinsic pathway involves apoptosis‐related proteins such as Bax, Bak, Bcl2, Cyto‐c, adaptor protein Apaf‐1, and active caspases. 177 Thus, regulating these proteins by phytochemicals could be an alternative for better management of patients with BC. Ginsenoside Rh1 (50 μM, 24 h) exerted a potential anti‐cancer effect against BC (MCF‐7 and HCC1428) cells through induction of apoptosis and autophagy. 110 Nimbolide (1.97–5 μM) and pharbilignan C (5–20 μM) are associated with the down‐regulation of Bcl‐2/Bax along with up‐regulation of caspases (caspases 9 and 3), thereby leading to induced apoptosis of MDA‐MB 231 and MCF‐7 cells through mitochondrial‐dependent intrinsic pathways. 88 , 112 Furthermore, nimbolide induces cancer cell autophagy by inhibiting mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and p62 expression and increasing two essential proteins, Beclin 1, and LC3B expression. 112 Jin et al. reported that daidzein (25–100 μM) treatment of MCF‐7 BC cells caused up‐regulation of Bax protein and down‐regulation of Bcl‐2 protein expression, leading to cytochrome c release, which in turn induced apoptosis via activating caspases‐9 and 7. 111 Choi et al. reported that treatment of BC cells (MDA‐MB 231) with sanguinarine (0–1.5 μM) caused apoptosis by generating ROS, leading to the transfer of cytochrome‐c into cytosol followed by caspase‐3 and caspase‐9 activation and inactivation of anti‐apoptosis factor XIAP and cIAP‐1. 114 Chew et al. noted that lutein regulated the apoptosis pathway by increasing tumor suppressors (and apoptosis genes) such as p53 and Bax and decreasing anti‐apoptosis genes such as Bcl‐2 expression in female BALB/c mice. 115 Zu et al. reported that emodin (40 μM) inhibits growth by inducing apoptosis through up‐regulating cleaved Bax/Bcl2, p53, caspase‐3, PARP cleavage in human BC (ZR‐75‐30 and Bcap‐37) cells. 117 Another phytochemical, withaferin A (2.5–5 μM) induced apoptosis through ROS production by modulating the expression of Bax/Bak in MDA‐MB 231 and MCF‐7 BC cells. 118 Furthermore, Mi et al. reported that celastrol (1–10 μM) induced apoptosis by modulating the expression of TNF‐α, caspase‐8, caspase‐3, and PARP cleavage along with inhibition of anti‐apoptotic proteins such as cellular cIAP1 and cIAP2, FLIP, and Bcl‐2 expression in MCF‐7 and MDA‐MB 231 cells. 119 Also, lycopene and EGCG induced apoptosis by up‐regulating the expression of p53 and Bax/Bcl‐2 ratio with down‐regulating telomerase and P13K/AKT in MCF‐7 and T47D cancer cells. 83 , 113 Furthermore, curcumin and resveratrol can induce apoptosis through the regulation of Bax/Bcl2, whereas thymoquinone, apigenin, pterostilbene, and sulforaphane are associated with apoptosis by regulating caspases cascade and signal transduction mechanism in multiple human BC cells. 144 , 164 , 178 , 179 , 180 , 181 Therefore, phytochemicals inhibit BC progression by apoptosis induction, which mediates either intrinsic or extrinsic, and sometimes both pathways.

3.3. Inducing cell cycle arrest

The cell cycle is a principal physiological mechanism regulating tissue homeostasis and development in multicellular organisms. Therefore, alterations in the cell cycle cause cancer. Thus, novel strategies have been developed targeting altered cell cycles or components. Checkpoints in the cell cycle arrest cell cycle progression in the case of DNA damage, allowing time for DNA repair. 182 , 183 In numerous breast carcinomas, phytochemicals inhibit the passage of the cell cycle by modulating checkpoints components such as lowering cyclins (D1 and E) levels and cyclin‐dependent CDKs etc., and by up‐regulating the expression of proteins such as CDK inhibitors (p21 and p27). For example, quercetin halts the cell cycle at the G2/M phase by raising Cdk‐inhibitor, especially p21CIP1/WAF1 and its associated protein Cdc2‐cyclin B1 complex in MCF‐7 cancer cells. 120 Treatment of coumestrol (50 μM) caused cell cycle arrest at the G1/S phase, followed by upregulations of regulatory protein CDKI and p21 and p53 in MCF‐7 cells. 122 Also, taiwanin A treatment was associated with the up‐regulation of p21, p27, p53, and p‐p53 in MCF‐7 cells in a dose‐dependent manner. 121 Kim et al. reported that ginsenosides (100 μM) had arrested the cell cycle at G0/G1 phase via inhibiting Cyclin D1, Cyclin E2, and their associated enzyme CDK4, along with up‐regulating p15INK4B, p21WAF1/CIP1 and p55 level in MCF‐7 cells. 123 Another phytochemical, kaempferol, reduced MCF‐7 cell growth by down‐regulating cathepsin D, cyclin E, and cyclin D1 expressions and up‐regulating Bax and p21. 124 Furthermore, thymoquinone (100–200 μM) significantly inhibited the expression of cyclin D1 and E, resulting in promoting the survival of multiple BC (MCF‐7, T47D, and MDA‐MB‐231) cells. 125 Moreover, naringenin is an essential plant chemical that can regulate cell cycle checkpoints by suppressing CDK4, CDK6, and CDK7 with up‐regulating p18, p19, and p21 in BC (HTB26 and HTB132) cells. 126 Altogether, phytochemicals halt the progression of the cell cycle of BC cells by either inhibiting the expression and activity of cyclins (B1, D1, and E) and CDKs (4, 6, 7) or increasing the expression of CDKs inhibitors (p18, p21, p27, and p53).

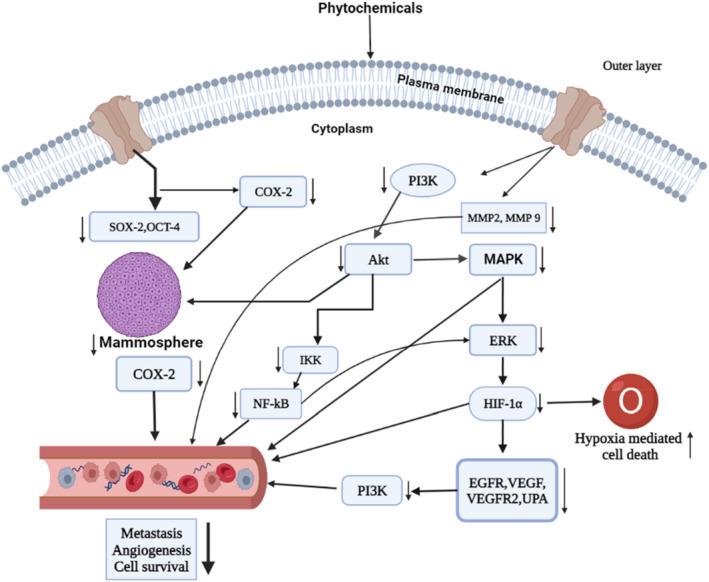

3.4. Inhibition of angiogenesis and metastasis

Angiogenesis is closely associated with metastasis. These processes are acquired at a critical density of arteries and occur as the tumors expand, spread, or become less differentiated. 184 Growth factors (VEGF, PDGF, FGF, and EGF), matrix metalloproteinase (MMP‐2, MMP‐9), intracellular adhesion molecules‐1(ICAM‐1), etc., are associated with these processes. Thus, they can be a potential target for cancer therapeutics development. It was reported that phytochemicals have significant anti‐metastatic and anti‐angiogenesis effects by inhibiting MMP‐9 and MMP‐2 and suppressing VEGFR‐2 expression, thereby inhibiting the growth and invasiveness and adhesion of cancer cells. 185 , 186 Flavopiridol, a phytochemical (70nM ), inhibited secretion of metalloproteinase, especially MMPs (MMP 2 and 9) and c‐erbB‐2 in MDA‐MB‐231 cells, which is associated with the reduction of cell invasion inhibition. 128 Nobel phytochemicals such as 2‐hydroxy chalcone and xanthohumol exerted potent inhibitory effects on the invasive phenotype of MDA‐MB‐231 cells by inhibiting MMP‐9 expression with Bcl‐2 down‐regulation and shikonin showed a similar result in MCF‐7 cells. 127 , 132 The reduced level of MMP‐9 and urokinase‐type plasminogen activator was observed in MDA‐MB‐231, TPA‐induced MCF‐7 cells followed by a lower dose of arctigenin (10–200 μM) treatment in turn inhibited cells' movement. 131 Similarly, plant‐derived silymarin decreased VEGF secretion, blocked PMA‐induced inhibition of MMP‐9, and blocked AP‐1 activation, thus, modulating MAP signaling in MCF‐7 and MDA‐MB‐ 468 cells in a dose‐dependent manner. 129 In addition, it could downregulate VEGF activity in MDA‐MB‐231 cells, inhibiting angiogenesis. 139 Mali et al. reported that ENL (2–25 μM) could downregulate MMP‐2 and MMP‐9 activity while up‐regulating tissue inhibitors, that is, metalloproteinases 1 and 2 (TIMP‐1 and TIMP‐2), in MDA‐MB‐231 cells. 109 Another phytochemical Rg3 (5 mg/kg/2 day) suppressed cell migration and angiogenesis while promoting autophagy through decreasing angiogenesis factors (VEGFA, VEGFB, VEGFC), metastatic factors (MMP‐2, MMP‐9), signaling molecules (P13K, Akt, mTOR, JNK, p62, and Beclin‐1) in MCF‐7 cells. 134 Treatment with quercetin (34 mg/kg) inhibits angiogenesis by reducing the activity of VEGF, VEGFR2, and NFATc3 in human BC xenografted nude mice. Also, it defeats calcineurin activity and its mediated pathway. 133 Kil et al. reported that silibinin (50 μg/mL) could inhibit metastasis and migration by inhibiting EGFR phosphorylation and suppressing VEGF, MMP‐9, and COX‐2 in MDA‐MB‐468 cells, resulting in decreased tumor volume in the triple‐negative BC xenograft model. 136 Isoliquiritigenin (25–50 μM) treatment inhibited signaling molecules such as NF‐κB, P13K/Akt, and p38, decreasing MMP‐2, MMP‐9, VEGF, and HIF‐1α expressions leading to reduce the motility of MDA‐MB‐231 cancer cells. 137 Another phytochemical, thymoquinone, could modulate the expression of epithelial markers such as E‐cadherin, cytokeratin 19, and mesenchymal markers such as MMP‐2, MMP‐9, integrin‐aV, TGF‐b in MCF‐7 and MDA‐MB‐231 cells. 138 Thus, the suppression of angiogenesis and metastasis in BC cells can be achieved by treating with plant products or plant‐derived bioactive compounds, which could suppress matrix metalloproteinases, growth factor expressions, and signaling mechanisms (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Control of breast cancer by dietary phytochemicals targeting multiple patways: Targeting the multiple signal transduction, phytochemicals can suppress some cell signaling pathways, that is, PI3k/Akt/mTOR, MAPK/ERK, NF‐κB, HIF‐1α, leading to a decrease cancer cell metastasis, angiogenesis, and survival. Followed by the signal transductions, phytochemicals can mitigate important metastatic and angiogenic factors including EGFR, VEGF, VEGFR2, NF‐κB, MMP2, MMP9, COX‐2, and ERK in breast cancer cell line.

3.5. Inhibition of hypoxia‐inducible factor

Tumor hypoxia refers to cells being deprived of normal oxygen due to low oxygen levels in the tumor microenvironment. Hypoxia induces multiple signaling cascades such as MAPK, phosphatidyl‐inositol 3‐kinase (PI3K), HIF, and NF‐κB pathways in cancer cells, leading to feedback loops of both positive and negative, and enhancing or diminishing hypoxic effects. 187 It was also found that hypoxia regulates several cellular phenomena, such as the expression of drug efflux proteins, apoptosis, DNA damage, the efficiency of chemotherapy, angiogenesis, and metastasis. 187 Therefore, targeting hypoxia‐inducible factor 1 (HIF‐1), a crucial component of hypoxia, could be a potential strategy against hypoxia‐induced cancer cell growth and progression. Several phytochemicals can directly inhibit HIF‐1‐related genes, including GLUT‐1, CDKN1A, and VEGF. This inhibition ultimately results in a decrease in tumor angiogenesis, migration, and chemotaxis. According to Wang et al. isoliquiritigenin (25–50 μM) treatment suppressed P13K/Akt, NF‐κB signaling pathways via modulating the expression of VEGF, HIF‐1α, and MMP‐2, MMP‐9 expressions, leading to limit the migration of MDA‐MB‐231 cells. 137 Riby et al. demonstrated that 3,3‐diindolylmethane (50 μM) exhibited anti‐cancer activity by decreasing the expression of hypoxia‐responsive factors such as furin, and glucose transporter‐1, VEGF, enolase‐1, and phosphofructokinase in hypoxic specific MDA‐MB‐231 cells. 141 In addition, lyciumbarbarum polysaccharides inhibit HIF‐1α protein aggregation by altering mRNA levels and VEGF mRNA expression leading to inhibit the nuclear translocation of HIF‐1α in MCF‐7 cells. 142 Another study showed that EGCG (50 μg/mL) inhibits breast tumor formation, proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis by inhibiting HIF‐1α in MCF‐7 and MDA‐MB‐231 cells. 140 Wang et al. noted that shikonin (10 μM) suppresses the expression of HIF‐1α in MDA‐MB‐231 cells in hypoxic conditions. 188 Thus, phytochemicals inhibit cancer progression by regulating hypoxia‐inducible factors by aggregation or degradation (Figure 3).

3.6. Inhibition of oxidative stress and redox signaling

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as hydroxyl radical, superoxide anion radical, hydrogen peroxide, oxygen singlet, nitric oxide radical, and peroxynitrite extreme play essential roles in the initiation and development of tumors. 189 These species contribute to harmful genomic material, making them genetically unstable. Also, they act as intercessors in mitogenic and survival signaling using adhesion molecules and receptors of growth factors. Enzymes involved in an antioxidant system, such as catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxiredoxins (PRXs), glutathione peroxidase (GPX) and glutathione reductase, are essential for maintaining cellular redox system. 190 However, it is not easy to mitigate the excessive production of ROS by cellular antioxidant enzymes. 191 It was noted that phytochemicals could modulate oxidative stress and redox signaling by regulating the expression of these enzymes. For example, Singh et al. reported protective roles of resveratrol via increasing Nrf‐2 expression, which could up‐regulate the expression of antioxidant genes such as SOD3, NQO1, and 8‐oxoguanine DNA glycosylase 1 (OGG1). 192 In addition, biochanin A (500 μg/g) has shown anti‐cancer activity in oxidative stress‐mediated cancer by up‐regulating CAT, DT‐diaphorase, GST, GPx, and SOD, along with the reduction of lipid peroxidation and lactate dehydrogenase activities significantly. 193 Nadal‐Serrano et al. reported the protective effects of Genistein on oxidative stress, redox signaling, and mitochondria, followed by up‐regulation of ERβ in T47D BC cells. 194 Moreover, Fan et al. reported that 3,3′‐diindolylmethane (1 μmol/L) protects BC cells against oxidative stress by stimulating the expression of nuclear factor erythroid 2 in BC cells. 195 Therefore, phytochemicals regulate oxidative‐mediated cancer progression by controlling potent oxidative markers, including Nrf‐2 expression and antioxidant gene expression in both in vitro and in vivo models.

3.7. Inhibition of mammosphere formation

The formation of the mammosphere is an essential characteristic of cancer progression, mainly cancer stem cells (CSCs). Several studies reported that BC cells, including non‐adherent, non‐differentiating CSC, form the mammosphere. 196 CSCs are believed to be associated with cancer reappearance, metastasis, and resistance to anti‐cancer drugs. Thus, targeting breast CSCs by inhibiting mammosphere formation can be an alternative approach for managing BC. Naturally occurring plant‐based compounds can prevent cancer cells and CSCs by decreasing mammosphere formation. 197 For example, Wu et al. demonstrated that pterostilbene suppressed mammosphere formation BCSCs growth by reducing CD44+ surface antigen expression and stimulating β‐catenin phosphorylation. 143 The pterostilbene also modulates the hedgehog/Akt/GSK3b signaling pathway via the down‐regulation of cyclin D1 with c‐Myc expression. 143 Another phytochemical, sulforaphane (SFN), reduced the number and size of ALDH1‐positive (BCSC) cells, resulting in the inhibition of mammospheres formation in both in vitro and in vivo models. 198 In addition, SFN‐pretreated ALDH+ cells showed enhanced sensitivity to taxane, thereby blocking mammospheres formation significantly. 144 Fu et al. noted that resveratrol (100 mg/kg/day) treatment against BCSCs induces autophagy by suppressing the Wnt/β‐catenin signaling pathway in MCF‐7 and SUM159 cells. 146 Colacino et al. found that curcumin downregulates the expression of CD49f, ALDH1A3, PROM1, and TP6 in MCF‐7, MCF10A, SUM149‐derived stem cells' growth and proliferation. 147 Benzyl isothiocyanate (3 μmol BITC/g) treatment suppressed the expression of both Ron and sfRon in cultured MCF‐7 derived stem cells and tumor xenografts, indicating that benzyl isothiocyanate treatment caused inhibition bCSCs in vitro and in vivo. 145 Piperine (10 μM) significantly decreased mammosphere formations in stem cells derived from BC. 199 Therefore, phytochemicals showed anti‐cancer activities by inhibiting mammosphere formation in multiple breast carcinomas by suppressing signaling pathways or their components (Figure 3).

3.8. Inhibition of inflammation

Inflammation is a biological reaction to cellular injury produced due to infections, chronic irritation, and other inflammatory responses. 200 Information suggests that inflammatory cells, including neutrophils, macrophages, dendritic cells, eosinophils, and lymphocytes were associated with tumor formation, development, angiogenesis, and progression. 201 , 202 Interestingly, significant research demonstrated that natural compounds prevent inflammation by regulating antioxidant defence mechanisms via modulating Phase I, and Phase II enzymes or inflammatory cells or factors in cancer. 203 An in vitro study reported the therapeutic advantage of polyphenols on the inflammatory phenotype of macrophages. 149 In this study, supplemented pomegranate juice polyphenols reduced M1‐macrophages mediated pro‐inflammatory stimulation in the J774.A1 macrophage‐like cells in a dose‐depended manner. 149 Curcumin also exhibited anti‐cancer properties against inflammation‐associated carcinogenesis by inhibiting TNF‐α mediated NF‐κB activation and inhibiting the proteasomal activity of IκB kinase in MCF‐7 cells. 150 Synergistically, using Sprague Dawley rats, curcumin with resveratrol inhibits inflammation by lowering NF‐κB and reducing inflammatory markers such as COX‐2 and MMP‐8 expression animal model. 151 In addition, Dharmappa et al. reported that genistein had anti‐inflammatory properties in cancer by inhibiting sPLA activity in a concentration‐dependent manner. 204 Furthermore, multiple dietary polyphenols combination from zyflamend, (e.g., resveratrol, curcumin, and EGCG), decreased the expression of pro‐inflammatory markers such as COX‐2, IL‐1β, TNF‐α, phospho‐Akt, phosphor‐p65, and NF‐κB‐binding activity in C57BL/6J female mouse model. 152 Therefore, natural phytochemicals are potent oncogenic inhibitors by regulating inflammation through regulating TNF‐α mediated NF‐κB, IκB kinase, COX‐2 and MMP‐8, IL‐1β, TNF‐α, phospho‐Akt, phosphor‐p65, and NF‐κB‐binding activity in numerous cancer models.

3.9. Enzymatic inhibition

Interfering the enzymatic functionality associated with cancer pathogenesis potentially prevents BC development. Phytochemical treatment could inhibit Phase I enzymes, inducible nitric oxide synthase, cyclooxygenase‐2, xanthine oxide, aromatase, and many more in cancer. 205 Supplementation of curcumin (20 μM) is associated with reversing hypermethylation of the Glutathione S‐Transferase Pi 1 (GSTP1) gene, resulting in reactivation via modulation of epigenetics mechanism in MCF‐7 cells. 153 It is also reported that curcumin (35 μM) inhibited MCF‐7 cell proliferation by Nrf2 arbitrated Flap endonuclease‐1 (Fen1) expression, 206 whereas resveratrol (25 mM) inactivates the aromatase enzyme by removing the CYP19 promoters I.3 and II transactivation. 154 Furthermore, resveratrol regulates other cancer‐associated enzymes such as COX‐2, NQO‐2, and GSTP 1. 207 In addition, Barbara E reported that cabbage juice inhibits BC (MCF10 and MDA‐MB‐231) cells by inhibiting aromatase expression. 208 Similarly, rosmarinic acid (10 μM) acts as an essential COX‐2 inhibitor through AP‐1 activation in MCF‐7 cells in a dose‐dependent manner. 106 Furthermore, another natural product, isoliquiritigenin (10–40 μM), showed chemopreventive actions by targeting metabolic enzymes such as COXs, PLA2s, LOXs, and PGE2, cytochrome P450 4 (CYP 4A) activity in MDA‐MB‐231, BT‐549 BC cells. 157 Quercetin and epigallocatechin could decrease glucose consumption and lactate production in MCF‐7 and MDA‐MB231 cells, inhibiting cancer‐related metabolic pathways. 158 Thus, phytochemicals showed anti‐cancer efficacy through regulation of enzymatic functions, that is, by regulating estrogen synthesizing enzymes such aromatase, estrogen metabolizing enzymes CYP 4A, CYP19 suppressing COX‐2 expression, or regulating GSTP1 in BC cells. Therefore, natural phytochemicals are potent oncogenic inhibitors by regulating several enzymes, including hypermethylation of the GSTP1, Flap endonuclease‐1, aromatase expression, CYP19 promoters I.3 and II transactivation, and numerous enzymes in different cell lines.

3.10. Natural compounds targeting cell signaling pathways

mTOR, PI3K, protein kinase B (Akt), MAPK/ERK, Wnt, Notch, and hedgehog signaling pathways are associated with the regulation of cell proliferation, differentiation, survival, apoptosis, invasion, migration, angiogenesis, and metastatic spread of cancer cells. 209 , 210 Phytochemicals elicit anti‐cancer actions by regulating these pathways or components. 159 For example, Seo et al. reported that genistein (100 μM) inhibited IκBα phosphorylation and maintained its association with p65–p50 heterodimer, which blocked their nuclear translocations, and p65 phosphorylation, which in turn prevented the transcription of NF‐κB targeted genes. 159 Also, genistein inhibited MAPK signaling by suppressing MEK5, ERK5, and p‐ERK5 levels in MDA‐MB231 cells, 211 whereas apigenin inhibited ERK 1/2 and JNK 1/2 phosphorylation via inhibiting MAPK signaling in MCF‐7 cells. 131 Calycosin and formononetin, two phytochemicals, regulated PI3K/Akt pathways through IGF‐1R protein expression along with the inhibition of Akt phosphorylation in T47D and MCF‐7 cells. 160 , 161 In addition, Fu et al. reported that resveratrol (100 mg/kg) down‐regulates Wnt/β‐catenin signaling, inducing autophagy in MCF‐7 cells 146 and inhibiting cell proliferation of SKBR‐3 BC cells through down‐regulation of various signaling pathways such as p‐Akt, PI3K, Akt, mTOR. 212 Apigenin inhibited MCF‐7 cells by inducing apoptosis by inhibiting NF‐κB, STAT3, and p53 signaling. 162 Silibinin is associated with the death of MDA‐MB‐231 cells by regulating Notch‐1 signaling pathways. 163 Pterostilbene regulates ERK1/2 activation, decreased cyclin D1, p‐AKT, mTOR, and increased p21, Bax protein, but not Bcl‐xL. 164 Hatkevich showed that naringenin inhibits PI3K, thus disrupting proliferation signaling in MCF‐7 cells through ERK1/2, AKT, and MAPK signaling pathways, 165 whereas α‐Mangostin mediated its anti‐tumor effect through decreasing HER2, Akt, and P13K along with increasing p‐p38 and p‐JNK1/2 phosphorylation. 166 Therefore, phytochemicals inhibit NF‐κB, PI3K/Akt, MAPK/ERK, p‐mTOR, Wnt, Notch‐1, and hedgehog signaling pathways by modulating their components or upkeep/downstream molecules in BCs (Figure 4).

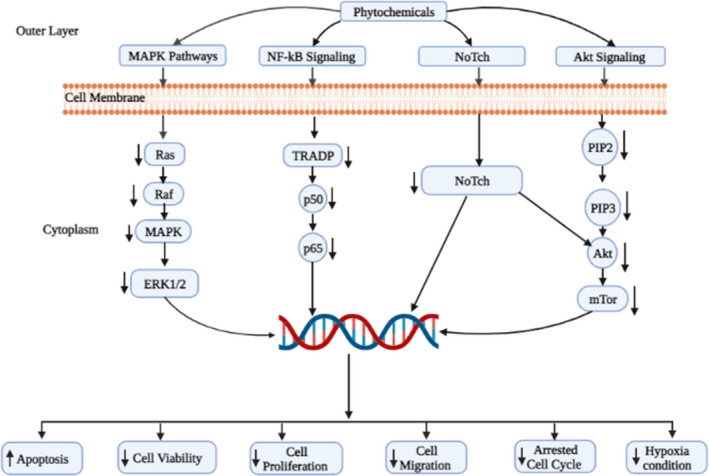

FIGURE 4.

Phytochemicals targeted signaling pathways associated with breast cancer treatment: The schematic diagram represents the overview of molecular mechanisms of phytochemicals mediated inhibition of breast cancer cell growth through the Notch, MAPK, NF‐κB, and Akt pathways.

3.11. Natural compounds targeting epigenetic control

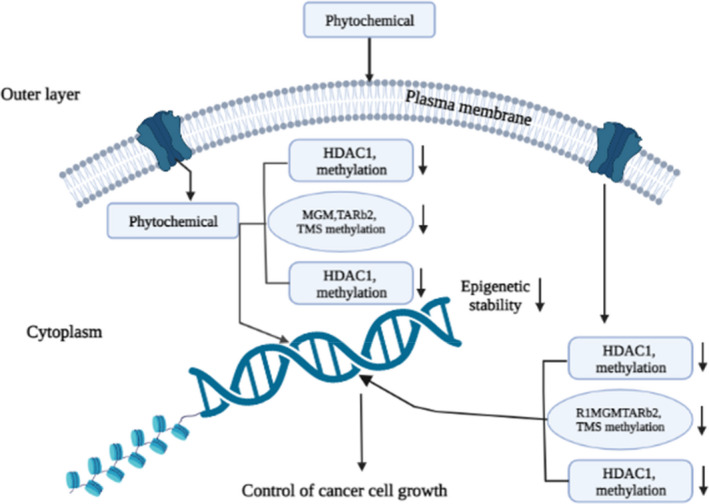

Accumulating information suggests that previous studies have shown that phytochemicals can modulate the epigenetics of cancer cells by regulating the methylation of DNA via DNA methyltransferase activity and histone modifications, resulting in inhibiting the oncogenic miRNA expression and increasing tumor‐suppressing miRNA expression. 213 , 214 , 215 Studies have shown that genistein could inhibit primary breast carcinogenesis by increasing some tumor suppressor protein i,e and p16, p16 (INK4a), p21, p21 (WAF1) expression, along with decreasing expression oncogene, that is, BMI1, and c‐MYC in estrogen negative MDA‐MB‐231 cell line. 167 Moreover, genistein attributed its anti‐cancer activity in BC cells by demethylating and reactivating methylation‐silenced tumor suppressor genes via direct contact with inhibition of both DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) catalytic domain activation and DNMT1 expression. 213 Furthermore, genistein decreased the oncogenic miR‐155 expression with increasing expression of miR‐155 targets such as Forkhead box O3 and casein kinase, p27, phosphatase, and tensin homolog (PTEN), which in turn that promote apoptosis and antiproliferation of MDA‐MB‐435 cells. 162 , 216 Lycopene up‐regulated glutathione S‐transferase pi gene (GSTP1) expression and demethylases the GSTP1 in MCF‐7, MDA‐MB‐468 cells, whereas induced RARbeta2 and HIN‐1 genes demethylation in BC (MCF10A) cells in a dose‐dependent manner. 168 Similarly, SFN (5 μM) significantly inhibits HDAC through demethylation in MDA‐MB‐231 cells. 171 Liu et al. reported that curcumin activated the promoter of deleted in liver cancer 1 by suppressing methylation status, with the help of down‐regulating the Sp1 transcription factor in MDA‐MB‐361 cells. 169 Also, EGCG (15 μM) treatment is associated with epigenetic changes that can increase DNMTs transcripts expressions such as DNMT1, DNMT3a, and DNMT3b in both MCF‐7 and MDA‐MB‐361 cells. 170 Thus, phytochemicals have the potential to modulate the epigenetic make‐up of BC cells via regulating DNA methylation and histone modification; therefore, they could control the expression of oncogenes and tumor suppression genes in BC cells. The summary of phytochemicals that act against epigenetics regulation is summarized in Figure 2.

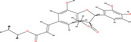

FIGURE 2.

Breast cancer management by dietary phytochemicals through enzymatic control of epigenetics factors: Breast cancer can regulate epigenetics factors. The key epigenetic regulatory protein R1MGMTARb2, TMS methylation, BMI1, c‐MYC, HDAC1 methylation, histone modification can be regulated by dietary phytochemicals; leading to show anti‐cancer effect.

3.12. Natural compounds targeting the immune system

Phytochemicals include substances found in nature that can be bioactive and possess an immune system‐stimulating effect. 217 For example, curcumin, a clinically naturally occurring compound, has immunomodulatory properties that suppress PHA‐induced T cell proliferation, IL‐2, NO, and NF‐κB while increasing NK cell cytotoxicity in mouse macrophage cells RAW.264.7. 218 A study involving C57BL/6 mice found that apigenin may influence the alteration of dendritic cells and other immune cell functions. 219 Daidzein, has a modulatory function on nonspecific immunity in Swiss mice when given in high doses since it enhances the phagocytic response of peritoneal macrophages. 220 Additionally, in male Kunming mice exposed to 60Coγ radiation, EGCG significantly reduced immune system destruction by inducing macrophage phagocytosis, boosting the activity of the antioxidant enzymes, that is, SOD and GSH‐Px (glutathione peroxidase), raising glutathione level, and preventing lipid peroxidation. 221 Conversly, genistein regulates immunological response in female Sprague Dawley, promoting IL‐4 synthesis while inhibiting IFN‐γ release and balancing Th1/Th2 cells. 222 Furthermore, kaempferol had immune‐suppressive effects on cold‐stressed, 6‐7‐week‐old SPF mice, decreasing the levels of activated pro‐inflammatory cytokines like IL‐9 and IL‐13, CD8+ T cells and raising anti‐inflammatory cytokines and CD4+ T cells. 223 Therefore, selected phytochemicals have the potential to activate immune system including numerous immune cells including NK cell, CD8+ T, CD4+ T and cytokines like IL‐9 and IL‐13 to fight against BC cells. A summary of the anti‐cancer mechanism of phytochemicals in BC treatment is presented in Table 3 and Figures 1, 2, 3, 4.

FIGURE 1.

Breast cancer management by dietary phytochemicals through apoptosis and cell cycle: Phytochemicals activate caspase‐8 through modulating TRAIL‐ and FAS‐associated receptors. Activated caspase‐8 mediated activation of some effector caspase‐3 and caspase‐7 attributed to the extrinsic pathway of apoptosis. Moreover, the anti‐apoptotic protein BCL2 mediates activation of BAK, BAX. These powerful mechanisms increase cytosolic Ca2+, cytochrome c, and reactive oxygen species (ROS). Cytochrome c sequentially activates caspase‐9, which is simultaneously activated by effector caspase‐3 and caspase‐7 attribute to apoptosis. Activation of tumor suppressor protein (p21CIP1/W, p27, p53, pRB, and AF1) and suppression of cyclin (cyclin B, D1, E1) with associating enzymes (CDK 2, 4) by phytochemicals regulated cell cycle and cell proliferation.

4. THE ABILITY OF PHYTOCHEMICALS TO ALLEVIATE THE RESISTANCE OF ANTI‐CANCER DRUGS

Due to numerous significant challenges, such as multi‐drug resistance, treating cancer patients is becoming more difficult. 224 Drug efflux, drug inactivation, drug detoxification, drug target modification, involvement of CSCs, miRNA dysregulation, epigenetic alteration, and other numerous irregular DNA damage/repair mechanisms, tumor microenvironment, and ROS modulation are just a few potential defensive processes that could result in this resistance mechanism. 40 , 225 , 226 P glycoprotein (P‐GP), MRP 1, MRP 1–9, BCRP, and changes in beta‐tubulin are a few proteins that are connected to drug resistance in cancer. 227 The multi‐drug resistance protein P‐glycoprotein (P‐gp) is overexpressed in the membrane of cancer cells, where it commonly increases drug efflux and contributes to the emergence of treatment resistance in malignancies. 228 Hence, inhibiting MDR‐efflux proteins may help improve cancer therapy's effectiveness. For example, Biochanin A exhibits this type of action. Soo et al. demonstrated that Biochanin A treatment increased [3H]‐DNM accumulation by reducing DNM efflux and caused MDR to be reversed by suppressing P‐gp activity in MCF‐7/ADR BC cells. 225 The effects of phloretin on P‐gp activity were examined (HTB26) by measuring the uptake of rhodamine 123 in a variety of cancer cells, including human MDR1 gene‐transfected mouse lymphoma cells (L1210) and human BC cells MDA‐MB‐231 expressing the MRP1 pump. 226 Genistein indirectly raises intracellular drug concentration, including doxorubicin concentration, but does not directly alter P‐gp activity in a BC cell lines. In a study, Castro and Altenberg reported that genistein reduced the photo‐affinity labeling of P‐gp with [3H] azidopine, a P‐gp substrate, indicating that genistein might suppress rhodamine123 efflux in human MCF‐7 cells by directly interacting with P‐gp to impede P‐gp‐mediated drug efflux. 229 The other component that stimulates the formation of BC is human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), a tyrosine kinase (TK) receptor that belongs to the EGFR family. Curcumin was reported to have the capacity to alter the EGFR signaling pathway, which is linked to the growth, differentiation, adhesion, and migration of cancer cells. 230 , 231 According to Chandrika et al. hesperetin at 10‐500 μM promotes apoptosis in MDA‐MB‐231 and SKBR3 BC cells and inhibits their ability to proliferate. Dietary flavonoid hesperetin reduces the development of MDA‐MB‐231 BC cells by inhibiting the activity of HER2 Tyrosine Kinase (HER2‐TK), causing MMP loss, chromatin condensation, and activating caspase‐8 and‐3, which causes cell cycle arrest at the G2 phase. 232 Sesamin inhibited cell migration at the same dosage and cells by delaying the G1 phase and down‐regulating PDL‐1, MMP‐9, and MMP‐2. Sesamin's ability to inhibit cell proliferation was demonstrated by Yokota et al. in BC cells. They discovered that sesamin inhibited growth at doses of 1–100 M by increasing retinoblastoma protein dephosphorylation and decreasing cyclin D1 gene expression, which mediates cyclin D1 degradation. 102 The co‐treatment of resistant (MCF‐7R) cells with Apigenin, which reduced MDR1 expression at the mRNA and protein levels in both resistant and non‐resistant cells, significantly reduced DOX resistance in the MCF‐7 cell line. In both the MCF‐7 and MCF‐7R cell lines, apigenin strongly inhibited the phosphorylation and activation of the JAK2 and STAT3 proteins. 233 By lowering Bcl‐2, Nimbolide induces the expression of the proteins Bax and caspases with a modulation of the expression of HDAC‐2 and H3K27Ac, and stopping the progression of the cell cycle, as well as reduced the growth of MDA‐MB‐231 and MCF‐7 cells. Increasing Beclin 1 and LC3B and decreasing p62 and mTOR protein expression in BC cells. Nimbolide also activated autophagy signaling. 112 Combining Sanguinarine with TRAIL therapy may break BC cells' resistance caused by overexpression of Akt or Bcl‐2. In human BC MDA‐231 cells, Sanguinarine triggered apoptosis, which resulted in decreased pro‐caspase‐3, Bcl‐2, cIAP2, XIAP, and c‐FLIPs protein levels and increased ROS production. 234 When Emodin was applied to the BC cells Bcap‐37 and ZR‐75‐30, it was shown to suppress proliferation, induce apoptosis, and decrease Bcl‐2 while increasing levels of cleaved caspase‐3, PARP, p53, and Bax. 117 In MCF‐7 and MDA‐MB‐231 cells, Isoliquiritigenin lowered cell survival and clonogenic potential, triggered apoptosis, suppressed mRNA expression of many AA‐metabolizing enzymes, including PLA2, COX‐2, and CYP‐4A, and reduced production of PGE2 and 20‐HETE. Moreover, it reduced the expression of phospho‐PI3K, phospho‐PDK, phospho‐Akt, phospho‐Bad, and Bcl‐xL, triggering caspase cascades that ultimately led to the cleavage of PARP. 235 The expression pattern of β‐catenin in BC tissue are high than the normal tissue. EGCG thus decreased the viability of MDA‐MB‐231 cells by lowering the levels of β‐catenin, cyclin D1, and p‐AKT. Moreover, pretreatment of MDA‐MB‐231 cells with PI3 kinase inhibitors, such wortmannin or LY294002, enhanced the suppressive effect of EGCG, given after 24 h, on the production of β‐catenin. 236 By transfecting the plasmid and inducing cytotoxicity and autophagy in BCSCs derived from MCF‐7 and SUM159, Resveratrol inhibits the Wnt/β‐catenin signaling pathway and excessive production of the β‐catenin protein. 146 The impact of Wogonin supplementation on cell survival and proliferation has been shown to be effective against a variety of BC cell lines, including TNBC and its related cell lines, BT‐549 and MDA‐MB‐231. Additionally, wogonin inhibits the cell cycle of cancer cell lines by inhibiting the expression of cyclin D1, cyclin B1, and CDK1, inducing apoptosis, improving the Bax/Bcl‐2 ratio, and increasing caspase‐3 cleavage. 237 In ER‐positive BC cells like MCF‐7 and T‐47D cells, Calycosin tends to suppress proliferation and trigger apoptosis. This effect is caused by ER‐induced inhibition of IGF‐1R as well as the targeted control of the MAPK and (PI3K)/Akt pathways. 161

5. LIMITATIONS AND PROSPECTS OF PHYTOCHEMICALS IN BREAST CANCER THERAPY DEVELOPMENT

Several factors interfere with the conventional therapeutic options used to treat BC. Phytochemicals offer a broad spectrum of pharmacological effects, which might benefit the clinical management of patients with BC. Phytochemicals are an effective therapeutic agent due to their several biological properties. Though phytochemicals have enormous benefits, there are significant constraints in achieving the actual effectiveness of phytochemicals‐based therapeutic for the management of patients with BC due to the lack of systematic and proper information in this field. In addition, to develop a clinically useful drug, a series of preclinical and clinical it must pass in vitro, in vivo, and clinical trials (Phase I–IV) studies must be accomplished with clinical benefit. Furthermore, long‐term studies are still required to determine therapeutic interactions, in vivo pharmacokinetic attributes, effective doses, suitable administration routes, and defined mass and/or nanoformulation of these phytochemicals. To estimate bioactivities, the structure–activity relationship must be established. Gathering additional information regarding phytochemicals' synergistic actions when combined with other phytochemicals, it is possible to boost their activity and prevent the anti‐cancer profile by modifying conventional medications. Moreover, these phytochemicals could be used in computational chemistry research, such as docking, neural networking, and pharmacophore‐based virtual screening programs for the drug development sector. Therefore, these phytochemicals could potentially become a potent chemotherapeutic anti‐cancerous substance in managing BCs, at least at the cellular level and could be formulated for clinical applications if all of the strategies are accomplished.

6. CONCLUSION

Although the complete molecular mechanisms for BC pathogenesis are yet to be established, whereas the mortality rates associated with this cancer are still rising worldwide. Thus, developing an effective therapeutic, especially from natural resources, that is, phytochemical‐based therapeutic, could provide significant clinical benefit in the management of patients with BC. The details mechanism of anti‐cancer activity from in vitro, preclinical and clinical studies suggested that phytochemicals mediate their anti‐cancer efficacy through targeting apoptosis proteins, including anti‐apoptotic proteins (Bcl‐2) and apoptotic proteins (Bax, Bak, Bad, and Caspase), arresting cell cycle and proliferation. They modulate the expression of growth‐related genes, for instance, inhibiting expression and activity of cyclins (B1, D1, E) and CDKs (4, 6, 7) or increasing the expression of CDKs inhibitors (p18, p21, p27, and p53). Inhibits metastasis and angiogenesis by controlling the expression of MMP‐2,8 and 9, Wnt/‐catenin, PARP, oxidative markers, including Nrf‐2, antioxidant‐related gene, inhibiting mammosphere formation, regulating inflammation via modulating TNF‐α, NF‐κB, IκB kinase, COX‐2, IL‐1β, TNF‐α, phospho‐Akt, phospho‐p65. Also, regulation enzymatic functions (i.e., aromatase, estrogen metabolizing enzymes CYP 4A, CYP19 suppressing COX‐2 expression, or regulating GSTP1), targeting cell signaling (NF‐κB, PI3K/Akt, MAPK/ERK, p‐mTOR, Wnt, Notch‐1, hedgehog), epigenetics control (regulating DNA methylation and histone modification), activate immune system (NK cell, CD8+ T, CD4+ T, cytokines like IL‐9 and IL‐13) in BC cell lines.

To conclude, phytochemicals may be used as an alternative and complementary therapeutic option in BC treatments due to their therapeutic benefits. However, further studies are needed to conduct before taking phytochemicals as a food supplement to manage and prevent BC until clinically proven standard drugs are not available in pharma‐markets.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Md Sohel: Conceptualization (supporting); data curation (lead); resources (lead); validation (lead); visualization (supporting); writing—original draft (lead); writing—review and editing (supporting). Suraiya Aktar: Resources (supporting); writing—original draft (supporting). Partha Biswas: Resources (supporting); visualization (supporting). Md. Al Amin: Resources (supporting); writing—original draft (supporting). Md. Arju Hossain: Data curation (supporting); resources (supporting). Nasim Ahmed: Resources (supporting); writing—original draft (supporting). Md. Imrul Hasan Mim: Visualization (supporting). Farhadul Islam: Supervision (supporting); validation (supporting); writing—review and editing (supporting). Md. Abdullah Al Mamun: Conceptualization (lead); resources (supporting); supervision (lead); validation (supporting); visualization (lead); writing—original draft (supporting); writing—review and editing (lead).

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not‐for‐profit sectors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Sohel M, Aktar S, Biswas P, et al. Exploring the anti‐cancer potential of dietary phytochemicals for the patients with breast cancer: A comprehensive review. Cancer Med. 2023;12:14556‐14583. doi: 10.1002/cam4.5984

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sun YS, Zhao Z, Yang ZN, et al. Risk factors and preventions of breast cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 2017;13:1387‐1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Karpuz M, Silindir‐Gunay M, Ozer AY. Current and future approaches for effective cancer imaging and treatment. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2018;33:39‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nobili S, Lippi D, Witort E, et al. Natural compounds for cancer treatment and prevention. Pharmacol Res. 2009;59:365‐378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rodriguez EB, Flavier ME, Rodriguez‐Amaya DB, Amaya‐Farfán J. Phytochemicals and functional foods. Current situation and prospect for developing countries. Segur Aliment Nutr. 2015;13:1‐22. doi: 10.20396/san.v13i1.1841 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cragg GM, Grothaus PG, Newman DJ. Impact of natural products on developing new anti‐cancer agents. Chem Rev. 2009;109:3012‐3043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sharma SB, Gupta R. Drug development from natural resource: a systematic approach. Min Rev Med Chem. 2015;15:52‐57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang R, Li YLH, et al. Antitumor activity of the Ailanthus altissima bark phytochemical ailanthone against breast cancer MCF‐7 cells. Oncol Lett. 2018;15:6022‐6028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Singh RK, Ranjan A, Srivastava AK, et al. Cytotoxic and apoptotic inducing activity of Amoora rohituka leaf extracts in human breast cancer cells. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2020;11:383‐390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nakamura Y, Yoshimoto M, Murata Y, et al. Papaya seed represents a rich source of biologically active isothiocyanate. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:4407‐4413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shahruzaman SH, Mustafa MF, Ramli S, Maniam S, Fakurazi S, Maniam S. The cytotoxic properties of Baeckea frutescens branches extracts in eliminating breast cancer cells. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2019;2019:1‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Benarba B, Meddah B, Aoues A. Bryonia dioica aqueous extract induces apoptosis through mitochondrial intrinsic pathway in BL41 Burkitt's lymphoma cells. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;141:510‐516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kushwaha PP, Vardhan PS, Kapewangolo P, et al. Bulbine frutescens phytochemical inhibits notch signaling pathway and induces apoptosis in triple negative and luminal breast cancer cells. Life Sci. 2019;234:116783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kaur V, Kumar M, Kumar A, Kaur S. Butea monosperma (Lam.) Taub. bark fractions protect against free radicals and induce apoptosis in MCF‐7 breast cancer cells via cell‐cycle arrest and ROS‐mediated pathway. Drug Chem Toxicol. 2020;43:398‐408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huyen CTT, Luyen BTT, Khan GJ, et al. Chemical constituents from Cimicifuga dahurica and their anti‐proliferative effects on MCF‐7 breast cancer cells. Molecules. 2018;23:1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Estanislao Gómez CC, Aquino Carreño A, Pérez Ishiwara DG, et al. Decatropis bicolor (Zucc.) Radlk essential oil induces apoptosis of the MDA‐MB‐231 breast cancer cell line. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16:266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Beier BA. A revision of the desert shrub Fagonia (Zygophyllaceae). Syst Biodivers. 2005;3:221‐263. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li P, AnandhiSenthilkumar H, Wu S‐b, et al. Comparative UPLC‐QTOF‐MS‐based metabolomics and bioactivities analyses of Garcinia oblongifolia . J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2016;1011:179‐195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jiang F, Li Y, Mu J, et al. Glabridin inhibits cancer stem cell‐like properties of human breast cancer cells: an epigenetic regulation of miR‐148a/SMAd2 signaling. Mol Carcinog. 2016;55:929‐940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu Z, Liu M, Liu M, Li J. Methylanthraquinone from Hedyotis diffusa WILLD induces Ca2+‐mediated apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. Toxicol In Vitro. 2010;24:142‐147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Barani M, Mirzaei M, Torkzadeh‐Mahani M, Nematollahi MH. Lawsone‐loaded niosome and its antitumor activity in MCF‐7 breast cancer cell line: a nano‐herbal treatment for cancer. DARU. 2018;26:11‐17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yerlikaya S, Baloglu MC, Diuzheva A, Jekő J, Cziáky Z, Zengin G. Investigation of chemical profile, biological properties of Lotus corniculatus L. extracts and their apoptotic‐autophagic effects on breast cancer cells. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2019;174:286‐299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Huang X, Zhang QY, Jiang QY, Kang XM, Zhao L. Polysaccharides derived from Lycium barbarum suppress IGF‐1‐induced angiogenesis via PI3K/HIF‐1α/VEGF signalling pathways in MCF‐7 cells. Food Chem. 2012;131:1479‐1484. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sun J, Rui HL. Apple phytochemical extracts inhibit proliferation of estrogen‐dependent and estrogen‐independent human breast cancer cells through cell cycle modulation. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:11661‐11667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chon SU, Kim YM, Park YJ, Heo BG, Park YS, Gorinstein S. Antioxidant and antiproliferative effects of methanol extracts from raw and fermented parts of mulberry plant (Morus alba L.). Eur Food Res Technol. 2009;230:231‐237. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rohini B, Akther T, Waseem M, Khan J, Kashif M, Hemalatha S. AgNPs from Nigella sativa control breast cancer: an in vitro study. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 2019;38:185‐194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yu JS, Kim AK. Platycodin D induces apoptosis in MCF‐7 human breast cancer cells. J Med Food. 2010;13:298‐305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Elmaidomy AH, Mohyeldin MM, Ibrahim MM, et al. Acylated iridoids and rhamnopyranoses from Premna odorata (Lamiaceae) as novel mesenchymal–epithelial transition factor receptor inhibitors for the control of breast cancer. Phytother Res. 2017;31:1546‐1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sartippour MR, Seeram NP, Heber D, et al. Rabdosia rubescens inhibits breast cancer growth and angiogenesis. Int J Oncol. 2005;26:121‐127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Basso AV, Leiva González S, Barboza GE, et al. Phytochemical study of the genus Salpichroa (Solanaceae), chemotaxonomic considerations, and biological evaluation in prostate and breast cancer cells. Chem Biodivers. 2017;14:e1700118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]