Abstract

Although women engage in both physical and nonphysical aggression, little is known about how aggression type influences perceptions of their morphology, personality, and social behavior. Evolutionary theory predicts that women avoid physical aggression due to risk of injury, which could compromise reproductive success. Engaging in physical aggression might therefore decrease women’s perceived mate value. However, physical aggression could be advantageous for some women, such as those who are larger in size and less vulnerable to injury. This presents the possibility that physically aggressive women might be perceived as larger and not necessarily lower in mate value. These hypotheses have not been tested. Across three studies, I used narratives to test the effect of aggression type (physical, verbal, indirect, nonaggressive) on perceptions of women’s height, weight, masculinity, attractiveness, and social status. In Studies 1 and 2, participants perceived a physically aggressive woman to be both larger and more masculine than nonphysically aggressive women. In Study 3, participants perceived both a physically aggressive woman and a nonaggressive woman to be larger than an indirectly aggressive woman; the effect of aggression type on perceptions of a hypothetical man’s height was not significant. I also found some evidence that aggression type influenced perceptions of attractiveness and social status, but these were small and inconsistent effects that warrant further study. Taken together, the results suggest that physical and indirect aggressive behavior may be associated with certain morphological and behavioral profiles in women.

Keywords: aggression, body size, women, masculinity, social status, attractiveness

Relative to men, little is known about women’s aggression. Which women engage in which types of aggression, and how women’s aggressive behavior influences people’s perceptions of their morphology, personality, and social behavior has not been well studied. One reason for this is that women are less physically aggressive than men (Archer, 2004), and therefore their aggression may be less obvious. In most mammals including humans, the female invests more than the male in child-rearing. Women may be less physically aggressive because it places them at greater risk of injury and death, which would limit their ability to bear and care for offspring, ultimately lowering their reproductive success (Campbell & Cross, 2012). Although not necessarily less competitive, women may therefore avoid direct physical confrontation with competitors and instead strive to enhance their own reproductive qualities by putting energy into their physical appearance and being perceived as chaste. These qualities signal health, vitality, and paternal certainty—all of which are highly valued by potential male mates (e.g., Buss, 1989).

One way women compete is through indirect aggression. Indirect aggression harms competitors through damage to their reputations or social relationships. This is done covertly, though spreading rumors, excluding others from activities and peer groups, and making jokes at their expense (see Vaillancourt, 2013). Women use these techniques because they can exaggerate their own reproductive value while damaging the reputations of others. At the same time, they limit the physical risks to themselves by minimizing the likelihood of their opponent finding out about their aggression or at least delaying it. Indeed, several studies have shown that indirect aggression may be an effective strategy for increasing women’s mating opportunities, reducing the mating opportunities of competitors, and strengthening same-sex social alliances by excluding third parties (Beneson et al., 2011, 2013; Reynolds et al., 2018; reviewed in Arnocky & Vaillancourt, 2017).

However, there may be circumstances where it is more advantageous for women to engage in physical compared to indirect aggression. For example, a female-biased operational sex ratio (i.e., more women than men of reproductive age) would reduce the number of available male mates in a population, thus lowering each individual woman’s chances of reproductive success. Indeed, Campbell (2013) reported that women living in impoverished neighborhoods with low numbers of available men for long-term mating are not only willing to engage in short-term relationships to garner financial support but are also more physically aggressive in competition with other women. Further, Moss and Maner (2016) showed that when women were primed to think their town’s operational sex ratio was female-biased, they subjected a hypothetical desirable (physically attractive and high social status) same-sex competitor to longer and louder noise blasts than when they were primed to think their town’s operational sex ratio was male-biased.

Physical aggression is risky, though—both physically and socially. Women who engage in such aggression may therefore be those who are best able to mitigate those risks. For example, Campbell and Muncer (2009) found that self-reported “risky” impulsivity, which includes actions such as “drive too fast when I’m feeling upset” and “run across the road to beat traffic if I am in a hurry,” was positively correlated with self-reported acts of physical and verbal aggression in women. In addition, greater muscularity, body mass, height, and body size would increase a woman’s chances of not only surviving a physically risky scenario but also in physically dominating a competitor. A growing body of evidence suggests that body size positively predicts actual physical aggression in women. Pinhey (2002) found a positive correlation between adolescent girls’ body mass index (BMI) and their self-reported participation in physical fights. Further, Palmer-Hague et al. (2015) found that BMI positively predicted both number of fights and number of wins in a sample of adult female mixed martial arts fighters. Indirectly aggressive women have also been shown to be larger (Gallup & Wilson, 2009) and could be perceived as such, but there is more evidence suggesting larger women are victims of others’ indirect aggression (Janssen et al., 2004; Pearce et al., 2002).

Body size may therefore serve as a cue to a woman’s aggressive behavior. Several studies have shown that women’s body size positively predicts naive raters’ impressions of their aggressiveness. Gallup and Wilson (2009) found that BMI, calculated from height and weight measurements collected by nurses during annual school examinations, was positively correlated with participants’ perceptions of women’s aggressiveness from their yearbook photographs. Similarly, Sell et al. (2009) found that both male and female participants’ judgments of women’s physical strength from pictures of their bodies and faces accurately aligned with their actual upper body strength measurements. In a more recent study, Palmer-Hague et al. (2018) found that BMI positively predicted both men and women’s ratings of aggressiveness and fighting ability in photographs of faces of female Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) fighters.

If body size serves as a cue to women’s aggressive behavior, then we might also expect descriptions of aggressive behavior to influence perceptions of women’s body size. In fact, somewhat surprisingly, Fessler, Holbrook, et al. (2014) showed that participants perceived a woman described as risk-prone (e.g., a “daredevil,” “climbed a steep rocky cliff without safety gear”) to be larger in size than a woman described as risk-averse (e.g., “cautious,” “refused to hike up a path on a hillside, even though she was wearing safety gear”). According to the Crazy Bastard Hypothesis (Fessler, Tiokhin, et al., 2014), this display of nonviolent risk-taking contributes to an observer’s perception that the risk-taker is willing to take physical risks and would therefore be more dangerous in a potential conflict. Thus, the observer perceives them as physically formidable (i.e., larger). Although this work assumes that risk-taking signals formidability in the same ways for both men and women, it failed to control for sex differences in physical aggression. Women’s relatively smaller size and lowered frequency of physical aggression could influence the ways in which people assess their propensity to harm compared to men’s. This hypothesis has not yet been tested.

In addition, it is unclear whether physically aggressive women can bear the associated social costs of such behavior. If physical aggression compromises reproductive success, people should perceive physically aggressive women as lower in mate value. Although this hypothesis has not been directly tested, several lines of research support its plausibility. For example, many studies have shown that men consider women with higher BMI to be less physically attractive (e.g., Grillot et al., 2014; Singh & Young, 1995). In addition, others have shown that women with higher BMI may have fewer sexual partners and be less open to sex without commitment than women with lower BMI (e.g., Fisher et al., 2016). Of course, men might find women with higher BMI less attractive for other reasons, such as lowered fecundity (see Buss & Schmitt, 1993; Lassek & Gaulin, 2016; Singh & Young, 1995); however, the link between aggression and body size suggests that BMI could be associated not only with the ability to produce but also to raise and provide for healthy offspring after birth.

Given the large and robust sex differences in physical aggression (Archer, 2004), it is also possible that women who engage in physical aggression will be perceived as more masculine than their less physically aggressive peers. Perceived masculinity, either through assessment of physical features, observed behavior, or both, could influence perceived attractiveness. For example, it is well-known that both men and women perceive more feminine female faces to be more attractive than masculine ones (e.g., Perrett et al., 1998). However, Keisling and Gynther (1993) showed that when masculine behavioral descriptions were paired with women’s faces, perceptions of their attractiveness decreased. Specifically, they found that men rated photographs of (previously rated) unattractive or average-looking women described as “independent” or “assertive” as less attractive than those described as “affectionate” or “compassionate.” Thus, women who are known to engage in particularly “masculine” behaviors may be perceived as depicting more masculine and less attractive physical features as well.

On the other hand, perceptions of mate value could be irrelevant to women’s aggressive behavior. Several studies have shown that preferences for body size depend on resource availability, with men from poorer geographic locations preferring larger BMI (e.g., Swami & Tovee, 2005, 2007). This is presumably because women with higher BMI demonstrate greater ability to acquire caloric resources. If physical aggression helps women to acquire scarce resources, then physically aggressive women might be perceived as equally or even more attractive than nonphysically aggressive women. In fact, men appear relatively unaffected by women’s dominance in their perceptions of her mate value, both for short- and long-term partners. This was true when women were described as both physically and socially dominant (Bryan et al., 2011; Honey & Coulombe, 2009; Sadalla et al., 1987; but see Brown & Lewis, 2004). Taken together, these studies suggest that women’s mate value might not be dependent on their aggressive behavior.

Aggressive behavior should, however, influence perceptions of women’s social status. As a status-seeking strategy, aggression assists both men and women to obtain mates, resources, and social alliances. In males, physical aggression is associated with dominance over same-sex rivals, which leads to control of resources and access to mating opportunities (reviewed in Archer, 2019). Because women devote more resources to rearing and raising offspring, they are less likely to compete with same-sex rivals in this way. However, given that women’s physical aggression might enhance their ability to acquire resources and mates, physically aggressive women might be perceived as higher in social status than women who aren’t physically aggressive. In contrast, a growing body of evidence suggests that women use indirect aggression as a strategy to increase their access to mating opportunities as well as enhance same-sex social alliances (Beneson et al., 2011, 2013; Reynolds et al., 2018; reviewed in Arnocky & Vaillancourt, 2017). Thus, women who are indirectly aggressive might be perceived as higher in social status than physically aggressive women. These hypotheses have not been tested.

Here, I report the results of three studies designed to investigate the effects of women’s aggressive behavior on perceptions of their body size, masculinity, attractiveness, and social status. I used narratives describing fictitious women engaged in physical and nonphysical aggressive behaviors, as well as nonaggressive behaviors, to compare participants’ perceptions. Narratives that describe individuals with varying traits and behaviors of interest are commonly used in the literature and have been used in similar studies to assess perceptions of women’s body size (e.g., Fessler, Holbrook, et al., 2014) as well as their attractiveness and mate value (e.g., Brown & Lewis, 2004; Sadalla et al., 1987). Studies 1 and 2 tested the hypothesis that a physically aggressive woman would be perceived as larger, more masculine, less attractive, and lower in social status than a nonphysically aggressive woman. Study 3 clarified (a) how perceptions of mate value for aggressive women compared to a nonaggressive woman and (b) whether an effect of aggression type on perceptions of women’s body size reflected a general tendency to percieve threat in larger individuals, or specific attunement to individual differences in women who choose different aggression strategies.

Study 1

The purpose of Study 1 was to test the hypothesis that a woman described as physically aggressive would be perceived as taller, heavier, larger, more masculine, less attractive, and lower in social status compared to a woman described as nonphysically aggressive. Given that attractiveness increases women’s mate value (e.g., Bryan et al., 2011; Buss, 1989) as well as buffers the negative effects of physical aggression on popularity in young women (e.g., Rosen & Underwood, 2010), I also tested whether an explicit description of a woman as attractive would influence participants’ perceptions of her characteristics.

I had no a priori expectations for sex differences in these perceptions, except for attractiveness. Here, I did expect a sex difference; men would perceive a physically aggressive woman as less attractive than women would. I also hypothesized that this sex difference would be attenuated by a description of women as attractive.

Method

Participants

I recruited 180 students (65 men, mean age (SD) = 19.77 (2.68) years and 115 women, mean age (SD) = 19.68 (4.21) years) from Trinity Western University as participants. Sensitivity analysis (β = .80, α = .05, three independent variables, eight groups) with G*Power (Faul et al., 2007) revealed that with this sample, the minimum effect size I could detect was medium (f = .23). Sample size was determined before any analyses were conducted. Each participant received introductory psychology course credit in exchange for participating. The majority of participants were White/Caucasian (68%), East Asian/Asian (10%), and South Asian/Indian (5%).

Materials

Aggression narratives

To assess the effects of aggression type and attractiveness on participants’ perceptions of women’s body size, I created two narratives. One narrative described a hypothetical woman who was physically aggressive and the other described a hypothetical woman who was verbally and indirectly, but not physically, aggressive. For each aggression type, I also either described the woman as attractive or included no such description. In all four narratives, I attempted to portray Kristin as a typical peer. Thus, I included a concluding sentence about Kristin feeling remorse after her engagement in these conflicts. This was intended to mitigate any perception that Kristin was aggressive without cause or lacked insight, empathy, or concern regarding her actions. Narratives, with the attractiveness manipulation in brackets, are provided below.

Kristin (is an attractive woman who) is known as the life of the party. In her free time, she likes to go to concerts, watch movies, and go for long walks with her dogs. Although she is well-liked by her friends and coworkers, she tends to act out when she gets angry. One time…

[Physical]…she thought she saw her friend flirting with a guy she liked, and after an argument, ended up shoving her hard in front of everyone, including the guy. Another time, she pushed a chair out in front of a woman walking by, causing her to trip and fall in front of all her coworkers. Kristin always feels sorry after these things happen.

[Nonphysical]…she thought she saw her friend flirting with a guy she liked, and after an argument, ended up loudly calling her an “ugly slut” so that everyone, including the guy, heard her. Another time, she spread rumors about another woman, causing all of her coworkers to think she was having several affairs. Kristin always feels sorry after these things happen.

Perceptions of height, weight, and body size

To assess participants’ perceptions of women’s body size, I first asked them to provide an estimate of Kristin’s height, in inches, and weight, in pounds. I then presented a series of four silhouettes varying in size from largest to smallest and asked them to choose which one they thought best represented the woman in the narrative they read. Similar to Fessler, Holbrook, et al. (2014), I chose four silhouettes of women in different postures, hairstyles, and clothing to maximize the likelihood that participants would choose a silhouette based on body size rather than on other attributes (see Figure 1). Four presentation orders were generated. Relative size as well as the left to right presentation of each silhouette was alternated within the four versions. Versions were counterbalanced across participants.

Figure 1.

Four versions of silhouettes presented to participants.

Perceptions of masculinity/femininity and attractiveness

To assess participants’ perceptions of Kristin’s masculinity/femininity and attractiveness, I asked them to rate each attribute using Likert-type scales. Scales ranged from 1 = very feminine/very unattractive to 7 = very masculine/very attractive.

Perceptions of social status

To determine participants’ perceptions of Kristin’s social status, I used the Subjective Social Status Scale (Adler et al., 2000). Briefly, participants were presented with the image of a 10-rung ladder and asked to rank where Kristin would be. The bottom of rung corresponded to the lowest social status (e.g., least friends, worst or no dates, least money, etc.) and the highest rung corresponded to the highest social status (e.g., most friends, best dates, most money, etc.). For scoring, each rung was assigned a rank from 1 to 10, with 10 being the highest social status.

Procedure

Data were collected as part of a larger study investigating women’s aggression and dominance. Participants were asked to provide their own height, weight, and facial photograph for the larger study, but measures for the present study were administered to the participant first. There was therefore no possible influence from additional, unrelated procedures. After providing informed consent, participants were randomly assigned to one of the following aggression/attractiveness narrative combinations: (1) physical/attractive (n = 33 (male = 7, female = 26)), (2) physical/neutral (n = 55 (male = 25, female = 30)), (3) nonphysical/attractive (n = 51 (male = 23, female = 28)), (4) nonphysical/neutral (n = 41 (male = 10, female = 31)). They then read a narrative describing a fictional aggressive woman and provided perceptions of, in order, her height, weight, body size, masculinity/femininity, attractiveness, and social status. All study procedures were approved by the Trinity Western University Research Ethics Board.

Data Analysis

Age and ethnicity differences across groups were assessed with two-way (aggression type, attractive) analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Pearson’s χ2 tests. Perceived height, weight, masculinity, and social status were all analyzed with separate two-way (aggression type, attractive) ANOVAs. Moderating effects of participant sex were explored with subsequent three-way (aggression type, attractive, sex) ANOVAs. For attractiveness, I ran a three-way (aggression type, attractive, sex) ANOVA. Silhouette choice was explored initially with χ2 tests and then the effects of aggression type, attractiveness, and their interaction on silhouette size were tested with a multinomial logistic regression. Significance level was set to p < .050 for all analyses.

Null effects

In order to further explore the magnitude of any observed null effects, I employed equivalence tests using the two one-sided tests (TOST) procedure (Lakens, 2017). Based on previous literature, I assumed the smallest effect size of interest to be medium. Most effect sizes reported in meta-analyses of studies looking at aggression in social psychology are medium or larger (Richard et al., 2003). In addition, several studies have demonstrated very large effects of body size and shape on women’s attractiveness (e.g., Grillot et al., 2014; Singh & Young, 1995), and others have shown medium to large effects for relationships between women’s body size and aggressiveness (e.g., Gallup & Wilson, 2009, Study 2; Palmer-Hague et al., 2015, 2018). I therefore tested between group means against upper (d = .50) and lower (d = −.50) equivalence bounds for a medium effect.

Results

Sample Demographics

There was no significant difference in participants’ ages across aggression, F(1, 172) = 0.33, p = .565, η2 < .01, or attractive, F(1, 172) = 0.76, p = .386, η2 < .01, conditions, or between the four study groups, F(1, 172) = 2.37, p = .126, η2 = .01. There was also no significant difference in proportion of Caucasian participants across aggression (attractive: N = 84, χ2 = 1.02, p = .313, V = .11; neutral: N = 96, χ2 = 3.27, p = .070, V = .19) or attractive (physical: N = 88, χ2 = 1.21, p = .272, V = .12; nonphysical: N = 92, χ2 = 0.20, p = .654, V = .05) conditions.

Body Size

For perceived height, one woman (nonphysical/neutral) did not provide a response, and I excluded one woman’s (nonphysical/neutral) response (77 in.) for being >3 SD from the mean. For perceived weight, I excluded responses from three participants (two women [one physical/attractive, 200 lbs and one nonphysical/neutral, 230 lbs] and 1 man [physical/attractive, 66 lbs]) for being >3 SD from the mean. Descriptive statistics for the final sample are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Perceptions of Kristin’s Characteristics, by Aggression Type.

| Characteristic | Physical | Nonphysical | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attractive (n = 33) | Neutral (n = 55) | Attractive (n = 51) | Neutral (n = 41) | |

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Height (in.) | 67.36 (2.07) | 66.53 (2.20) | 66.81 (1.93) | 66.23 (2.28) |

| Weight (pounds) | 136.70 (15.07) | 134.41 (14.64) | 130.97 (15.36) | 128.97 (16.54) |

| Masculine | 3.12 (1.14) | 3.70 (1.31) | 2.63 (1.30) | 2.90 (1.39) |

| Attractiveness | 5.24 (0.97) | 4.90 (0.89) | 5.33 (1.05) | 4.98 (0.88) |

| Social status | 6.67 (1.85) | 6.26 (1.57) | 6.49 (1.85) | 6.43 (1.74) |

Perceived height

The main effect of aggression type on perceived height was not significant, F(1, 174) = 1.73, p = .190, η2 = .01, and it (d = .14) was significantly within the equivalence bounds, t(176) = −2.43, p = .008. In contrast, I did find a significant main effect of attractiveness, F(1, 174) = 4.72, p = .031, η2 = .03, where the woman presented as attractive, M (SD) = 67.03 (1.99), was perceived to be taller than the woman presented neutrally, M (SD) = 66.41 (2.13), d = .30. However, this difference was small (.62 in.) and should be interpreted with caution as it may or may not be important for social perception. The interaction between aggression type and attractiveness was not significant, F(1, 174) = 0.15, p = .701, η2 < .01.

Perceived weight

Here, I found a significant main effect of aggression type, F(1, 173) = 5.58, p = .019, η2 = .02. Women presented as physically aggressive, M (SD) = 135.26 (14.75) were perceived to be heavier than those presented as nonphysically aggressive, M (SD) = 130.09 (15.84), d = .34 (Figure 2). Neither the main effect of attractiveness, F(1, 173) = 0.83, p = .364, η2 < .01, nor the interaction between aggression type and attractiveness, F(1, 173) < 0.01, p = .951, η2 < .01, was significant. Further, the effect of attractiveness on perceived height (d = .07) was significantly within the equivalence bounds, t(175) = −2.85, p = .002.

Figure 2.

Distributions of perceived weight when Kristin was presented as physically aggressive compared to nonphysically aggressive. Black dots with thick horizontal bars represent the mean, and vertical bars represent ±1 SD. *p < .05.

Silhouette choice

Silhouettes sizes were chosen at similar frequencies overall, χ2(3) = 3.28, p = .351, r = .14. In contrast, participants were significantly more likely to select the silhouette depicting a woman with one hand on her hip (see Figure 1; n = 102, 57%) than all other silhouettes, regardless of size, χ2(3) = 103.62, p < .001, r = .76. A multinomial logistic regression confirmed there were no significant effects of aggression type, attractiveness, or their interaction on silhouette choice, R2 = .36 (Cox & Snell), χ2(9) = 6.55, p = .684, see Online Supplemental Material for full model results.

Masculinity, Attractiveness, and Social Status

Descriptive statistics for perceived masculinity, attractiveness, and social status, by group, are also shown in Table 1.

Perceived masculinity

I found a significant main effect of aggression type, F(1, 176) = 10.75, p = .001, η2 = .06, with the physically aggressive woman perceived as more masculine, M (SD) = 3.48 (1.27), than the nonphysically aggressive woman, M (SD) = 2.75 (1.34), d = .56. There was also a main effect of described attractiveness, F(1, 176) = 4.70, p = .032, η2 = .02, where the woman described as attractive, M (SD) = 2.82 (1.25), was perceived to be less masculine than the woman described neutrally, M (SD) = 3.36 (1.39), d = .41. The interaction effect was not significant (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effects of Aggression Type and Attractiveness on Kristin’s Perceived Masculinity, Attractiveness, and Social Status.

| Analysis | SS | df | F | p | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masculinity | |||||

| AT | 18.03 | 1 | 10.75** | .001 | .06 |

| A | 7.88 | 1 | 4.70* | .032 | .02 |

| AT × A | 1.00 | 1 | 0.60 | .442 | <.01 |

| Error | 295.35 | 176 | |||

| Attractiveness | |||||

| AT | 1.16 | 1 | 1.28 | .260 | <.01 |

| A | 2.46 | 1 | 2.71 | .101 | .02 |

| PS | 0.56 | 1 | 0.62 | .432 | <.01 |

| AT × A | 0.10 | 1 | 0.11 | .745 | <.01 |

| AT × PS | 2.38 | 1 | 2.62 | .108 | .01 |

| A × PS | 0.14 | 1 | 0.15 | .696 | <.01 |

| AT × A × PS | 0.04 | 1 | 0.04 | .834 | <.01 |

| Error | 156.23 | 172 | |||

| Social status | |||||

| AT | 0.002 | 1 | 0.001 | .980 | <.01 |

| A | 2.35 | 1 | 0.77 | .380 | <.01 |

| AT × A | 1.25 | 1 | 0.41 | .523 | <.01 |

| Error | 535.29 | 176 | |||

Note. AT = aggression type; A = attractiveness; PS = participant sex.

*p < .05. **p < .01.

Perceived attractiveness

Ratings of Kristin’s attractiveness, by aggression type and participant sex, are shown in Table 2. A three-way (aggression type, attractiveness, participant sex) ANOVA showed no significant main or interaction effects (Table 2). However, equivalence tests showed that for male participants, the difference in perceived attractiveness between the physically, M (SD) = 4.77 (0.91), and nonphysically, M (SD) = 5.30 (0.88), aggressive women (d = −.59) was outside the bounds, t(63) = −0.37, p = .644, 1 and therefore unlikely to represent a true null effect. In contrast, the observed effect for women’s ratings of the physically, M (SD) = 5.18 (0.92), and nonphysically aggressive, M (SD) = 5.10 (1.05), women (d = .08) was significantly different from the nearest equivalence bound, t(113) = −2.25, p = .013, and is therefore likely to reflect a null effect.

Perceived social status

No main or interaction effects were significant (Table 2).

Moderation by Participant Sex

I found no evidence that participant sex was a significant moderator of effects of aggression type or attractiveness on body size, masculinity, or social status (see Online Supplemental Material).

Discussion

The results of Study 1 demonstrate that when women are presented as physically aggressive, they are perceived by others to be heavier, more masculine, and potentially less attractive than when they are presented as nonphysically aggressive. These results provide preliminary evidence that women’s aggression influences perceptions of their morphological and personality characteristics, regardless of their stated attractiveness.

Interestingly, however, I found that perceptions of weight, but not height, were associated with women’s aggression. This contrasts with previous work showing that a woman described as risk-prone was perceived to be taller and larger than a woman described as risk-averse (Fessler, Holbrook, et al., 2014). Although it could be argued that my use of silhouettes in varying body postures, hairstyles, and physical builds confounded people’s perceptions of body size, Fessler, Holbrook, et al. (2014) used very similar silhouette arrays and found that body size perceptions superseded posture for judgments of risky behavior. Given that physical aggression is associated with physical risk, it is unclear why participants did not make the same judgments here. One possible explanation is that women’s aggression is not considered physically risky; another is that women’s aggression is more often associated with perceived heaviness than stature.

Yet another possibility, however, is that simply comparing physical with nonphysical forms of aggression did not allow me to make a distinction between verbal and indirect forms of aggression, which may have confounded participants’ perceptions of women’s body size. Verbal aggression, which is overt, may serve to signal an impending physical attack. Indirect aggression, in contrast, is covert. Thus, physically and verbally aggressive women might be perceived as larger in size than indirectly aggressive women. This would also have implications for perceptions of masculinity, attractiveness, and social status.

I found mixed evidence that perceptions of a woman’s attractiveness were dependent on her aggressive behavior. Although there was no significant main effect of aggression type, and no significant interaction effect for aggression type and participant sex, on perceived attractiveness, subsequent equivalence tests for each sex suggest that there may be a small effect of aggression type on men’s perceptions of attractiveness but not women’s. Additional data are required to determine whether effects of aggression type on men’s perceptions of women’s attractiveness exist but were too small to detect in this study.

Study 2

The purpose of Study 2 was to further evaluate the effect of aggressive behavior on perceptions of body size by isolating verbal from indirect aggression as independent forms of nonphysical aggression as well as to further evaluate the effect of aggression type on a woman’s perceived attractiveness. Both physical and verbal aggression are direct acts of confrontation, presenting explicit and potentially impending physical threats to others. I therefore hypothesized that women described as either physically or verbally aggressive would be perceived as larger and more masculine but lower in social status than a woman described as indirectly aggressive. Similar to Study 1, I hypothesized that women described as physically or verbally aggressive would be perceived as less attractive than a woman described as indirectly aggressive, and that this effect would be stronger for men than women.

Method

Participants

In order to detect a medium-sized main effect of aggression with power of .80 at a significance level of .05 (two independent variables, six groups), the minimum sample size was 158 (G*Power; Faul et al., 2007). Sample size was determined before any analyses were conducted. I recruited 160 participants from Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk, www.mturk.com). Eleven responses were invalid (9 [7 male and 2 female] respondents failed to follow survey instructions and 2 [1 male, 1 female] completed the survey twice) and were excluded from further analysis. Our final sample included 74 men and 75 women, mean age (SD) = 32.17 2 (9.06), who were predominantly White/Caucasian (74%), followed by Black/African American (10%), and East Asian/Asian American (8%).

Materials

Aggression narratives

I created three narratives, each depicting a hypothetical woman engaged in either physical, verbal, or indirect aggressive behavior. I made no reference to the woman’s attractiveness. The three narratives are shown below.

Kristin is known as the life of the party. In her free time, she likes to go to concerts, watch movies, and go for long walks with her dogs. Although she is well-liked by her friends and coworkers, she tends to act out when she gets angry. One time…

[Physical]…she thought she saw her friend flirting with a guy she liked, and after an argument, ended up shoving her hard in front of everyone, including the guy. Another time, she pushed a chair out in front of a woman walking by, causing her to trip and fall in front of her coworkers. Kristin always feels sorry after these things happen.

[Verbal]…she thought she saw her friend flirting with a guy she liked, and after an argument, ended up loudly calling her an “ugly slut” so that everyone, including the guy, heard her. Another time, Kristin called a woman a “dumb bitch,” causing everyone at the bar to turn around and stare at her. Kristin always feels sorry after these things happen.

[Indirect]…she thought she saw her friend flirting with a guy she liked, and after an argument, she spread rumors about her friend, causing all of her other friends to think she was having several affairs. Another time, Kristin told her neighbors that a woman new to their street was a “slut” and to keep their boyfriends and husbands away from her. Kristin always feels sorry after these things happen.

Perceptions of height and weight

Given that in Study 1 participants chose silhouettes based on body posture rather than size, I excluded a silhouette task from Study 2. To assess perceptions of body size, I asked participants to provide an estimate of Kristin’s height, in inches, and weight, in pounds.

Perceptions of masculinity and attractiveness

To assess participants’ perceptions of Kristin’s masculinity/femininity and attractiveness, I asked them to rate each attribute using the same scales as in Study 1.

Perceptions of social status

To determine participants’ perceptions of Kristin’s social status, I created an online version of the Subjective Social Status Scale (Adler et al., 2000). Participants were shown a ladder and asked to choose a number from 1 (top of ladder) to 10 (bottom of ladder). For ease of interpretation, I reversed these scores so that 10 represented the highest social status and 1 the lowest.

Procedure

Participants completed one of three online surveys, each containing a different aggression narrative (physical, verbal, or indirect). After giving informed consent, participants read the narrative and provided their perceptions of the woman’s height, weight, masculinity/femininity, attractiveness, and social status (in that order). Each participant received $1.25 US for completing the study. All study procedures were approved by the Trinity Western University Research Ethics Board.

Data Analysis

Age differences between groups were assessed with a one-way ANOVA and follow-up Pearson’s bivariate correlations. Ethnicity across groups was tested with a Pearson’s χ2 test. Perceived height, weight, masculinity, and social status were all assessed with one-way ANOVAs. Follow-up comparisons were performed using Fisher's Least Significant Difference (LSD) tests, where appropriate. Moderating effects of participant sex were explored with subsequent two-way (aggression type, participant sex) ANOVAs. Significance level was set to p < .050 for all analyses. Null effects were explored with equivalence tests using the TOST procedure (Lakens, 2017) where appropriate, as described in Study 1.

Results

Sample Demographics

The difference in reported age between groups approached significance, F(2, 133) = 3.00, p = .053, η2 = .04; participants in the indirect aggression condition were younger, M (SD) = 28.62 (6.18), than both the physical, M (SD) = 32.33 (10.29), and the verbal, M (SD) = 32.83 (9.73), aggression conditions (p = .051, d = .44 and p = .026, d = .52, respectively). However, age was not significantly correlated with perceptions of height (r = .06, p = .499), weight (r = .02, p = .823), masculinity (r = −.04, p = .654), attractiveness (r = .10, p = .247), or social status (r = .04, p = .644). There was no difference between conditions in the proportion of Caucasian participants, χ2(2) = 1.74, p = .418, V = .11.

Body Size

For perceived height, I excluded two men’s responses (53 and 56 in.) for being <3 SD from the mean. For perceived weight, I excluded one woman’s response for being >3 SD above the mean (280 lbs). Final descriptive statistics for perceived height and perceived weight are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics for Perceptions of Kristin’s Characteristics, by Aggression Type.

| Characteristic | Physical (n = 49) | Verbal (n = 50) | Indirect (n = 50) |

|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Height (in.) | 66.04 (2.61) | 64.16 (2.70) | 65.06 (1.93) |

| Weight (pounds) | 141.35 (21.88) | 132.30 (18.90) | 136.12 (28.06) |

| Masculinity | 3.84 (1.48) | 3.16 (1.45) | 2.58 (1.21) |

| Attractiveness | 4.51 (1.46) | 4.72 (1.34) | 4.54 (1.25) |

| Men (n = 74) | 4.13 (1.39) | 4.56 (1.61) | 4.68 (1.07) |

| Women (n = 75) | 4.88 (1.45) | 4.88 (1.01) | 4.40 (1.41) |

| Social status | 5.59 (1.58) | 5.22 (1.46) | 6.10 (1.28) |

Note. For height: verbal, n = 48; for weight: indirect, n = 49.

Perceived height

I found a significant effect of aggression type on perceived height, F(2, 144) = 5.93, p = .003, η2= .08, where the physically aggressive woman was perceived taller than both the verbally (p = .001, d = .71) and indirectly (p = .025, d = .43) aggressive women (Figure 3). The difference between the verbally and indirectly aggressive women was not significant (p = .255, d = .39); however, this effect was not significantly within the equivalence bounds for a medium effect, t(96) = −0.57, p = .285, suggesting it may not a true null effect.

Figure 3.

Distributions of perceived height when Kristin was presented as physically, verbally, and indirectly aggressive. Black dots with thick horizontal bars represent the mean, and vertical bars represent ±1 SD. *p < .05. **p < .01.

Perceived weight

Here, the main effect of aggression type approached significance, F(2, 145) = 3.06, p = .050, η2= .04; the physically aggressive woman was perceived as significantly heavier than the verbally (p = .026, d = .44) and indirectly (p = .045, d = .21) aggressive women (Figure 4). There was no significant difference between the verbal and indirect conditions (p = .826, d = .16); this effect approached the equivalence bounds for a medium effect, t(97) = 1.69, p = .05.

Figure 4.

Distributions of perceived weight when Kristin was presented as physically, verbally, and indirectly aggressive. Black dots with thick horizontal bars represent the mean, and vertical bars represent ±1 SD. *p ≤ .05.

Masculinity, Attractiveness, and Social Status

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 3.

Perceived masculinity

I found a significant effect of aggression type, F(2, 146) = 10.22, p < .001, η2 = .12, on perceived masculinity (Figure 5). The physically aggressive woman was perceived as more masculine than both the verbally (p = .016, d = .46) and indirectly aggressive (p < .001, d = .93) women. The verbally aggressive woman was also perceived as significantly more masculine than the indirectly aggressive woman (p = .038, d = .43).

Figure 5.

Distributions of perceived masculinity when Kristin was presented as physically, verbally, and indirectly aggressive. Black dots with thick horizontal bars represent the mean, and vertical bars represent ±1 SD. *p < .05. **p < .001.

Perceived attractiveness

I found no significant main effect of aggression type, F(2, 143) = 0.37, p = .689, η2 < .01, participant sex, F(1, 143) = 1.45, p = .230, η2 < .01, or their interaction, F(2, 143) = 1.86, p = .160, η2 < .02, on perceived attractiveness. Men and women’s ratings, by aggression type, are shown in Table 3.

Equivalence tests on men’s ratings showed that the difference between the physically and verbally aggressive conditions (d = .29) and the physically and indirectly aggressive conditions (d = .45) was outside the equivalence bounds for a medium effect and unlikely to represent true null effects, t(47) = 0.75, p = .228 and t(47) = 0.20, p = .421, respectively. In contrast, the difference between the verbally and indirectly aggressive conditions (d = .09) approached the bounds, t(48) = 1.46, p = .075, and likely represents a true null effect. For women’s ratings, equivalence tests showed that the difference between the physically and indirectly aggressive conditions (d = .34) and the verbally and indirectly aggressive conditions (d = .39) was outside the equivalence bounds for a medium effect and unlikely to represent true null effects, t(48) = −0.58, p = .282 and t(48) = −0.38, p = .353, respectively. In contrast, the difference between the physically and verbally aggressive conditions (d = .00) was within the equivalence bounds, t(48) = −1.77, p = .042, and likely represents a true null effect.

Perceived social status

Here, I found a significant main effect of aggression type on perceived social status, F(2, 146) = 4.67, p = .011, η2 = .06. Follow-up tests showed that the verbally aggressive woman was perceived as lower in social status than the indirectly aggressive woman (p < .01, d = .64). There were no significant differences between the woman described as physically aggressive and the woman described as verbally aggressive (p = .20, d = .24) or between the woman described as physically aggressive and the woman described as indirectly aggressive (p = .08, d = .36); however, both group differences were outside the equivalence bounds, t(98) = −1.28, p = .102 and t(97) = −0.72, p = .237, respectively, suggesting they may not be true null effects.

Moderation by Participant Sex

Again, I found no evidence for participant sex as a moderator of body size, masculinity, or social status (see Online Supplemental Material).

Discussion

The results of Study 2 provide additional support for the hypothesis that women’s aggression influences perceptions of their morphological and personality characteristics. In particular, Study 2 demonstrates that physically aggressive women are perceived as taller, heavier, and more masculine than verbally and indirectly (i.e., nonphysically) aggressive women. They may also be perceived as less attractive and lower in social status.

Although I wasn’t able to show a significant effect of aggression type on perceived attractiveness in my main analyses, follow-up equivalence tests suggest that ideas both men and women have about the attractiveness of aggressive women might be affected by the type of aggression they display. In fact, the results of these tests suggest that overt aggression might negatively impact women’s mate value. These effects might be smaller than were detectable in Study 2 and therefore warrant further research.

Interestingly, in contrast to Study 1, I also found here that women who engage in indirect aggression are perceived to be higher in social status than women who engage in verbal aggression. The difference between the physical and indirect aggression conditions was also not significant but did approach significance (p = .08) and warrants further investigation. This latter finding could suggest that women who engage in overt forms of aggression are perceived as having lower social status than those who use more covert forms. Indirect aggression may therefore facilitate ascendance within a social hierarchy, but additional evidence is required to determine whether this is directly related to mate value and choice, or in spite of it.

Study 3

Studies 1 and 2 provide evidence that people perceive women described as physically aggressive to be larger in size; however, because there was no nonaggressive control condition in Studies 1 and 2, it was impossible to determine the direction of any differences between women described as physically aggressive and women described as indirectly aggressive. In addition, Studies 1 and 2 did not permit an assessment of whether perceptions of physical formidability from aggressive behavior were dependent on sex of the aggressive target. To address these issues, I included a fourth, nonaggressive control condition where the target behaved in a nonaggressive manner in Study 3. I also included a corresponding male condition to serve as a comparison for each aggression type. This latter manipulation allowed me to test the extent to which participants’ perceptions of formidability were based generally on aggression signaling potential physical threat (i.e., a threat detection mechanism; see Fessler, Tiokhin, et al., 2014) rather than specific characteristics of women's behavior. In this case, I hypothesized that perceptions of body size should increase with risk of physical threat to the observer, regardless of target sex. However, if perceptions of formidability depend on evolved sex differences in aggressive behavior, I hypothesized that perceptions of men’s body size should not depend on type of aggressive behavior, and perceptions of women’s body size should be larger when physically aggressive compared to when verbally, indirectly, and not aggressive.

Method

Participants

In order to detect a medium-sized interaction effect between aggression type (four levels), target sex, and participant sex with power of .80 at a significance level of .05 (three independent variables, 16 groups), the minimum sample size was 179 (G*Power; Faul et al., 2007). Sample size was determined before any analyses were conducted. In order to approach 12 participants per group (N = 192) as well as account for any invalid and/or duplicate responses, I collected data from 215 participants from Amazon MTurk (www.mturk.com). Sixteen responses were invalid (9 [5 male, 4 female] respondents completed the study twice, 4 [3 male, 1 female] provided impossible height and weight estimates [BMI < 9], 2 [both male] also completed Study 2, and 1 did not report their sex) and were excluded from further analysis. My final sample included 96 men and 103 women (mean age = 36.54, 3 SD = 10.67) who were predominantly White/Caucasian (72%), followed by Black/African American (9%), and East Asian/Asian American (8%).

Materials

Aggression narratives

I created eight narratives (four for each target sex), each depicting a hypothetical woman or man engaged in either physical aggression, verbal aggression, indirect aggression, or neutral/nonaggressive behavior. The physical, verbal, and indirect aggression narratives were identical to those in Study 2, except that I revised the language to make it more gender neutral where appropriate (e.g., “ugly slut” was changed to “ugly freak” in the verbal condition). Given that all three aggression narratives involved both a provoked and an unprovoked aggressive behavior, I constructed the neutral/nonaggressive condition to reflect a person reacting nonaggressively in both a provoked and an unprovoked situation. The narratives are shown below.

Kristin/Dave is known as the life of the party. In her/his free time, she/he likes to go to concerts, watch movies, and go for long walks with her/his dogs. Although she/he is well-liked by her/his friends and coworkers, sometimes she/he gets angry. One time…

[Physical]…she/he thought she/he saw her/his friend flirting with a man/woman she/he was interested in, and after an argument, ended up shoving her/him hard in front of everyone, including the man/woman. Another time, she/he pushed a chair out in front of a woman/man walking by, causing her/him to trip and fall in front of all of her/his coworkers. Kristin/Dave always feels sorry after these things happen.

[Verbal]…she/he thought she/he saw her/his friend flirting with a man/woman she/he was interested in, and after an argument, ended up loudly calling her/him an “ugly freak” so that everyone, including the man/woman, heard her/him. Another time, Kristin/Dave called a woman/man a “stupid idiot,” causing everyone at the bar to turn around and stare at her/him. Kristin/Dave always feels sorry when 4 these things happen.

[Indirect]…she/he thought she/he saw her/his friend flirting with a man/woman she/he was interested in, and after an argument, she/he spread rumors about her/his friend, causing all of their other friends to think her/his friend was dishonest and couldn’t be trusted. Another time, Kristin/Dave told her/his neighbors that a woman/man new to their street liked to sleep around and to keep their boyfriends/girlfriends and husbands/wives away from her/him. Kristin/Dave always feels sorry when these things happen.

[Neutral/nonaggressive]…she/he thought she/he saw her/his friend flirting with a man/woman she/he was interested in, and after an argument, she/he decided to just forget about it and move on with her/his life. Another time, Kristin/Dave took a walk to clear her/his head when she/he felt angry. Kristin/Dave always feels sorry when these things happen.

Perceptions of body size, attractiveness, masculinity, and social status

The same measures were used as in Study 2.

Procedure

Participants completed one of two online surveys, each containing either Kristin or Dave. Within each survey, participants were randomly assigned to one of the four different aggression narratives (physical, verbal, indirect, and neutral/nonaggressive). After giving informed consent, participants read the narrative and provided their perceptions of the woman’s height, weight, masculinity/femininity, attractiveness, and social status (in that order). Each participant received $0.50 US for completing the study. All study procedures were approved by the Trinity Western University Research Ethics Board.

Data Analysis

Age differences across groups were assessed with a two-way (target sex, aggression type) ANOVA. Ethnicity differences were analyzed with Pearson’s χ2. Perceived height, perceived weight, masculinity, and social status were all analyzed with separate two-way (aggression type, target sex) ANOVAs. Perceived attractiveness was analyzed with a three-way (aggression type, target sex, participant sex) ANOVA. Subsequent two-way and/or univariate ANOVAs were used to interpret significant interaction effects. Post hoc LSD comparisons were used. Perceived risk was tested using a one-sample t test and subsequent Pearson’s correlations. Null effects were explored with equivalence tests using the TOST procedure (Lakens, 2017) where appropriate, as described in Study 1. Significance level was set to p < .050 for all analyses.

Results

Sample Demographics

Participants who rated the male target, mean (SD) = 38.45 (10.71) years, were significantly older than those who rated the female target, mean (SD) = 34.73 (10.38) years, F(1, 179) = 5.94, p = .016, η2 = .03; however, there was no significant difference in age between aggression type groups, F(3, 179) = 0.55, p = .650, η2 < .01, nor did age differ between groups depending on target sex, F(3, 179) = 0.601, p = .615, η2 = .01. Proportion of Caucasian participants did not differ significantly across aggression groups, χ2(3) = 2.65, p = .449, V = .12, or by target sex, χ2(1) = 3.09, p = .079, V = .13.

Body Size

Given population sex differences in body size, I assumed that perceptions of a target man and woman’s body size would differ. I therefore ran initial descriptive statistics for perceptions of height and weight for the male and female targets separately. For height, I excluded one woman’s (male target, 60 in.) and two men’s (female target, 53 and 56 in.) responses for being <3 SD from their respective group means. For weight, I excluded two women’s (male target, 278 lbs and female target, 250 lbs, respectively) and two men’s (male target, 300 lbs and female target, 250 lbs, respectively) responses for being >3 SD from the respective group means. Final descriptive statistics for Kristin and Dave’s perceived height and weight are shown in Table 4. Summary ANOVA statistics are shown in Table 5, and interaction plots are shown in Figure 6.

Table 4.

Descriptive Statistics for Perceptions of Kristin’s Characteristics, by Aggression Type and Participant Sex.

| Characteristic | Physical | Verbal | Indirect | Neutral |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Kristin (female target) | (n = 28) | (n = 24) | (n = 25) | (n = 24) |

| Height (in.) | 66.15 (2.20) | 65.46 (1.67) | 64.88 (2.71) | 66.54 (1.67) |

| Weight (pounds) | 142.17 (26.24) | 136.42 (24.95) | 150.56 (35.92) | 137.55 (11.59) |

| Masculinity | 4.32 (1.61) | 2.96 (1.46) | 3.44 (1.64) | 2.83 (1.17) |

| Attractiveness | 4.08 (2.02) | 4.75 (0.87) | 3.10 (1.73) | 5.27 (1.01) |

| Social status | 5.67 (1.61) | 4.83 (1.75) | 4.80 (1.32) | 5.82 (1.78) |

| Dave (male target) | (n = 23) | (n = 24) | (n = 25) | (n = 25) |

| Height (in.) | 70.35 (2.39) | 69.58 (2.83) | 69.04 (2.05) | 68.52 (2.84) |

| Weight (pounds) | 185.65 (25.24) | 180.68 (22.78) | 187.31 (27.47) | 176.80 (23.27) |

| Masculinity | 5.52 (0.99) | 5.21 (1.35) | 4.96 (1.10) | 5.04 (1.17) |

| Attractiveness | 4.26 (1.39) | 4.12 (1.17) | 3.72 (1.34) | 4.32 (1.35) |

| Social status | 5.35 (1.75) | 5.64 (1.35) | 5.56 (1.42) | 5.36 (1.22) |

Table 5.

Effects of Aggression Type and Target Sex on Perceived Height and Weight.

| Analysis | SS | df | F | p | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height (total inches) | |||||

| AT | 41.40 | 3 | 2.53‡ | .059 | .02 |

| TS | 639.78 | 1 | 117.21** | <.001 | .37 |

| AT × TS | 43.87 | 3 | 2.68* | .048 | .03 |

| Error | 1,026.20 | 188 | |||

| Weight (pounds) | |||||

| AT | 3,040.12 | 3 | 1.87 | .136 | .02 |

| TS | 89,452.66 | 1 | 165.30** | <.001 | .46 |

| AT × TS | 333.46 | 3 | 0.21 | .847 | <.01 |

| Error | 101,195.91 | 187 | |||

Note. AT = aggression type; TS = target sex.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ‡p < .06.

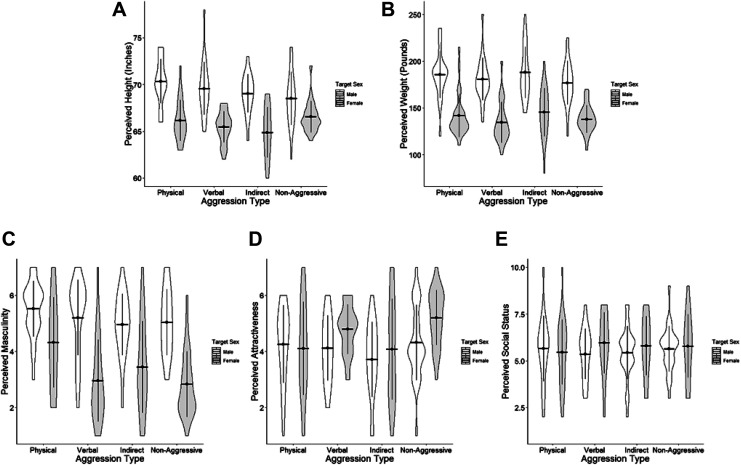

Figure 6.

Participants’ perceptions of male and female aggressors’ height (Panel A), weight (Panel B), masculinity (Panel C), attractiveness (Panel D), and social status (Panel E) by aggression type. Main effect of aggression type is significant for perceived masculinity (p = .001). Main effect of target sex (male > female) is significant for height, weight, and masculinity ( all ps < .001). Interaction is significant for perceived height ( p = .048). See main text for details.

Perceived height

As expected, I found a significant main effect of target sex, F(1, 188) = 117.21, p < .001, η2 = .37, with the male target perceived as taller than the female target. There was also a significant interaction between target sex and aggression type, F(3, 188) = 2.68, p = .048, η2 = .03 (Figure 6). A follow-up one-way ANOVA showed that for the female target, the effect of aggression type was significant, F(3, 95) = 2.98, p = .035, η2 = .09. Follow-up LSD tests showed that in both the physically aggressive and neutral/nonaggressive conditions, the woman was perceived as taller than in the indirectly aggressive condition (p = .034, d = .52 and p = .007, d = .74, respectively). There were no significant differences between the physically and verbally (p = .246, d = .35), the physically and neutral/nonaggressive (p = .507, d = .20), the verbally and indirectly (p = .340, d = .26), or verbally and neutral/nonaggressive (p = .078, d = .65) aggressive conditions. However, none of these effects fell within the equivalence bounds, t(49) = −0.53, p = .299, t(49) = 1.08, p = .143, and t(46) = −0.84, p = .203, respectively.

For the male target, the main effect of aggression type was not significant, F(3, 93) = 2.25, p = .088, η2 = .07. However, given my interest in this effect a priori, I further explored the difference between the largest and smallest height estimate averages (physical and nonaggressive conditions, respectively) with an independent samples t test. The physically aggressive man was perceived as significantly taller than the nonaggressive man, t(46) = 2.40, p = .020, d = .70.

Perceived weight

Again, I found an expected main effect of target sex, F(1, 187) = 165.30, p < .001, η2 = .46, with the male target perceived as heavier than the female target. No other main effects or interactions were significant (Table 5).

Masculinity, Attractiveness, and Social Status

One woman who rated the male target did not provide a masculinity rating. Descriptive statistics for the final sample are shown in Table 4. Summary ANOVA statistics for masculinity, attractiveness, and social status are shown in Table 6, and interaction plots for each characteristic are shown in Figure 6.

Table 6.

Effects of Aggression Type and Target Sex on Perceived Masculinity, Attractiveness, and Social Status.

| Analysis | SS | df | F | p | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masculinity | |||||

| AT | 28.72 | 3 | 5.35** | .001 | .05 |

| TS | 158.88 | 1 | 88.74** | <.001 | .30 |

| AT × TS | 9.97 | 3 | 1.86 | .139 | .02 |

| Error | 332.74 | 190 | |||

| Attractiveness | |||||

| AT | 3,537.14 | 3 | 4.43** | .005 | .06 |

| TS | 87,493.52 | 1 | 4.19* | .042 | .02 |

| PS | 121.13 | 1 | 4.43 | .471 | <.01 |

| AT × TS | 426.62 | 3 | 4.19 | .193 | .02 |

| AT × PS | 2,980.99 | 3 | 1.89 | .636 | <.01 |

| TS × PS | 104.08 | 1 | 0.20 | .160 | <.01 |

| AT × TS × PS | 3,689.63 | 3 | 2.33* | .039 | .04 |

| Error | 94,336.74 | 183 | |||

| Social status | |||||

| AT | 0.66 | 3 | 0.09 | .965 | <.01 |

| TS | 2.636 | 1 | 1.09 | .298 | <.01 |

| AT × TS | 4.153 | 3 | 0.57 | .635 | <.01 |

| Error | 462.78 | 191 | |||

Note. AT = aggression type; TS = target sex; PS = participant sex.

*p < .05. **p < .01.

Perceived masculinity

As expected, I found a significant main effect of target sex, F(1, 190) = 88.74, p < .001, η2 = .30, with the male target rated more masculine than the female target. I also found a significant main effect of aggression type, F(3, 190) = 5.35, p = .001, η2 = .06. Follow-up comparisons showed that regardless of target sex, individuals described as physically aggressive were perceived as significantly more masculine than those described as verbally (p = .002, d = .47), indirectly (p = .009, d = .43) aggressive, and nonaggressive (p < .001, d = .58). Differences between ratings of the verbally and nonaggressive (p = .648, d = .07), indirectly and neutral/nonaggressive (p = .372, d = .15), and verbally and indirectly aggressive (p = .667, d = .07) individuals were not significant; all effects fell outside of the equivalence bounds, t(95) = −2.12, p = .018, t(97) = −1.74, p = .043, and t(96) = 2.12, p = .018, respectively.

Perceived attractiveness

Descriptive statistics for attractiveness ratings for the male and female targets are shown in Table 7. Here, I found a significant three-way interaction between aggression type, target sex, and participant sex, F(3, 183) = 2.85, p = .039, η2 = .04. To interpret this interaction, I ran two-way ANOVAs for men and women separately.

Table 7.

Descriptive Statistics for Men and Women’s Perceptions of Kristin’s and Dave’s Attractiveness, by Aggression Type.

| Physical | Verbal | Indirect | Neutral | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Kristin | ||||

| Male | 4.08 (2.02) | 4.75 (0.87) | 3.10 (1.73) | 5.27 (1.01) |

| Female | 4.13 (1.41) | 4.83 (0.94) | 4.73 (1.58) | 5.15 (0.99) |

| Dave | ||||

| Male | 4.00 (1.22) | 4.33 (1.23) | 4.08 (1.26) | 4.31 (1.49) |

| Female | 4.60 (1.58) | 3.92 (1.12) | 3.33 (1.37) | 4.33 (1.23) |

For men, I found a significant main effect of aggression type, F(3, 88) = 3.43, p = .020, η2 = .10.Indirectly aggressive targetwere ratedsignificantly less attractive than verbally aggressive(p = .022, d = .68) and nonaggressive (p = .004, d = .76) targets targets. Physically aggressive targets were also rated less attractive than nonaggressive targets, and this difference approached significance (p = .064, d = .47). There were no significant differences between ratings of physically aggressive and verbally aggressive (p = .212, d = .36), physically and indirectly aggressive (p = .265, d = .25), or verbally aggressive and nonaggressive (p = .539, d = .17) targets; however, all three effects were outside of the equivalence bounds, t(47) = 0.48, p = .317, t(46) = −0.87, p = .194, and t(46) = 1.14, p = .130, respectively. Neither the main effect of target sex, F(1, 88) = 0.18, p = .670, η2 < .01, nor the interaction effect, F(3, 88) = 1.99, p = .121, η2 = .06, was significant.

For women, I found a significant main effect of target sex, F(1, 95) = 6.59, p = .012, η2 = .06, with the female target being rated more attractive than the male target. The interaction also approached significance, F(3, 95) = 2.39, p = .074, η2 = .06. Given my interest in the interaction a priori, I explored this effect with subsequent one-way ANOVAs. There was no significant main effect of aggression type for either the male, F(3, 43) = 1.98, p = .131, η2 = .12, or female, F(3, 52) = 1.65, p = .190, η2 = .09, target.

Perceived social status

No main or interaction effects were significant (Table 6).

Moderation by Participant Sex

I found no evidence of a moderating effect of participant sex on body size, masculinity, or social status (see Online Supplemental Material).

Discussion

The results of Study 3 further support the hypothesis that women who engage in physical aggression are perceived to be taller and more masculine than women who engage in other types. Interestingly however, my results also suggest that women who do not engage in any aggression at all are perceived to be taller than women who engage in indirect aggression. Although unexpected, this finding could suggest that women who are indirectly aggressive are generally considered to be smaller than other women. In contrast, it could be that participants perceived the nonaggressive woman to be avoiding engaging in desired physical aggression, and thus also larger compared to those who were indirectly aggressive.

Taken together, the results of Study 3 also suggest that the effect of aggression type on perceived height is not due to general threat detection. The lack of a main effect of aggression type on perceived height for the male target also supports this conclusion, but since that effect approached significance (p = .088), it warrants future study. It may be that despite literature suggesting small to no sex differences in indirect aggression, men are perceived as smaller and perhaps less threatening if they utilize nonphysical or no aggression strategies. Indeed, my results indicate that men who were not physically aggressive were perceived as less masculine.

Study 3 also helped to elucidate the relationship between aggression type and perceived attractiveness. Regardless of target sex, male raters perceived indirectly and physically aggressive individual to be less attractive than nonaggressive and verbally aggressive individuals. This suggests that if given a choice, men would find a potential female partner who does not engage in aggressive behavior as more attractive than one who does. It also aligns with evolutionary explanations for women’s tendency toward indirect aggression. Because it is covert, they don’t have to actually reveal their aggression to potential mates or social alliances. Additional data are needed from female raters to decipher the pattern of women’s perceived attractiveness for aggressive and nonaggressive targets.

Lastly, I found no evidence in Study 3 that aggressive behavior influences perceptions of body weight or social status in men or women. This lack of influence on body weight is in contrast to Studies 1 and 2, where physically aggressive women were perceived as heavier. The lack of influence on social status is in contrast to Study 2, where indirectly aggressive women were perceived to be higher in social status than the verbally aggressive woman. One possible reason for the discrepancies is that the brevity of the narratives forced participants to use their own imaginations to form perceptions of the male and female targets and that these varied across studies. Further research that varies narrative content would help to clarify these issues.

General Discussion

Collectively, my results demonstrate that women who are described as physically aggressive are perceived to be larger, more masculine, and potentially less attractive than women who are described as either verbally, indirectly, or not aggressive. Across three studies, I found that women described as physically aggressive were perceived to be larger (taller in Studies 2 and 3 and heavier in Studies 1 and 2) and more masculine than women described as nonphysically aggressive. I also found consistent evidence that physically aggressive behavior affects perceptions of women’s attractiveness, particularly for male participants. These effects were small, and not significant in Studies 1 and 2, but were significant in Study 3 and therefore warrant further study.

The positive relationship between physical aggression and perceived body size observed here compliments the results of several other studies that showed that larger women were accurately perceived to be stronger and more physically aggressive than smaller women (Pinhey, 2002; Sell et al., 2009). My findings also strengthen the generalizability of more recent work showing that BMI positively predicted both actual fighting ability and perceptions of aggressiveness and fighting ability in female UFC fighters (Palmer-Hague et al., 2015, 2018). Importantly, though, my results further suggest that perceptions of women based on their aggressive behavior may extend to other less physical types of aggression. Specifically, indirectly aggressive women might be perceived to be smaller and more feminine than nonaggressive women. These perceptions appear to be present even when a visual representation of the aggressor is not available.

Insofar as perceptions of women’s characteristics can be taken to reflect true characteristics of women who engage in aggressive behavior, my results also support the hypothesis that physical aggression, although presenting a substantial reproductive cost to most women, may be beneficial for some women in some circumstances. Indeed, women are more likely to engage in direct rather than indirect aggression when quality mates are less readily available (Campbell, 2013; Moss & Maner, 2016). Thus, when resources are scarce and reproductive success can only be maximized by the literal removal of competitors from the environment, a woman risks physical injury or death to obtain them. Larger women would presumably have a selective advantage over a smaller woman in these instances.

In contrast, physical aggression is unlikely to benefit women when resources are plentiful. I found that physically aggressive women were perceived to be more masculine than verbally, indirectly, and not aggressive women across studies. Further, I found some evidence that physically aggressive women are perceived as less attractive than nonphysically aggressive women (Studies 1 and 2). Although I also found that both physically and indirectly aggressive women are perceived as less attractive than not aggressive women (Study 3), it is important to consider that in a real-world situation, indirect aggression would be covert. Thus, unless discovered, the indirectly aggressive woman would be perceived similarly to the not aggressive woman. If physically aggressive women are indeed larger, they might be better served by competing indirectly by excluding competitors with covert, psychological tactics when overt aggression would be negatively perceived. Indeed, several studies have shown that men in low-resource environments prefer women with a larger BMI, whereas men in high-resource environments prefer women with a smaller BMI (e.g., Swami & Tovee, 2005, 2007). Evolutionary theory predicts that physical aggression should reduce women’s perceived attractiveness, but the effects I observed were small and should be interpreted cautiously.

Lastly, I found some evidence that indirectly aggressive women may be perceived to be higher in social status. This could suggest that for women, covert status-seeking strategies are more effective than overt status-seeking strategies. Indeed, previous work has shown that covert aggression strategies, such as exclusion of others, strengthen social relationships between women (Beneson et al., 2011, 2013). However, indirect aggression against female competitors may also increase the perceived mate value of the aggressor and decrease the perceived mate value of the victim (Reynolds et al., 2018; reviewed in Arnocky & Vaillancourt, 2017). Women could therefore use indirect aggression to ascend within a social hierarchy directly, through the elimination of social competitors, or indirectly, through the resource provision of a high-quality mate. It is important to note, however, that this effect wasn’t replicated in Studies 1 and 3. Additional studies looking at the mechanisms through which indirect aggression is perceived to enhance social status will help to elucidate this relationship further.

It is important to acknowledge that my results could also be explained by social influences rather than evolutionary theory. For example, social norms regarding women’s behavior might also have played a role in participants’ perceptions. Because men are more physically aggressive than women, physically aggressive women may be seen as more masculine. In addition, when women are physically aggressive, they are often portrayed in the media as being lower in socioeconomic status (SES). Lower SES might also be perceived to be associated with higher BMI and worse health outcomes, which could also influence ideas about aggressive behavior. Future work should seek to directly examine or at least control for these possibilities.

Limitations of my work include the lack of visual stimuli to accompany any narrative descriptions of women’s aggressive behavior. Given that body size can represent a variety of different characteristics (e.g., height, weight, shape, BMI), my use of height and weight here is relatively a rough assessment of people’s perceptions. Another limitation worth noting is that the narratives I used were brief and did not provide much context for ascertaining perceptions about specific attributes such as social status. Similarly, the measure I used to assess social status did not provide a specific context that would allow participants to discriminate between, for example, a work and social environment. I also did not ask participants about desirability as a potential mate, limiting the generalizability of attractiveness perceptions to mate value. Lastly, my sample sizes were modest and may have precluded detection of some important effects. Additional work with larger sample sizes will help to determine the robustness of my findings, particularly regarding relationships between body size, aggression, and attractiveness.

Taken together, the results of these three studies present evidence that women’s aggressive behavior influences perceptions of their morphology, personality, and behavior. Future studies that directly manipulate women’s body size and shape will help to assess the role of each component in their aggressive behavior and associated perceptions of their characteristics. This will be especially important for further evaluation of the effects of women’s aggressive behavior on perceived attractiveness. It will also be valuable for future work to focus on women’s aggressive behavior and how it influences both actual attained and perceived social status. Investigating different competitive contexts as well as different strategies for obtaining status (e.g., mate vs. peer relationships) will be beneficial.

Supplemental Material

Supplementary_Material_Revision_2 for Aggression Type Influences Perceptions of a Woman’s Body Size, Personality, and Behavior by Jaime L. Palmer-Hague in Evolutionary Psychology

Acknowledgment

The author thanks A. Fuller, T. Heath, H. Lim, A. Kowbel, Y. Wang, and D. Ewald for their assistance with data collection.

Notes

Equivalence tests are one-tailed and thus the probability that an effect falls on the equivalence bound is .5. Because this effect (d = −.59) originates outside of the set equivalence bounds (d = −.50 and d = .50), its t-value reflects distance away from d = .00 but on the other side of the distribution. Thus, the associated p value for this effect was calculated as 1 − .356 = .644.

Thirteen respondents (six male, seven female) did not report their ages.

Twelve respondents (nine male, three female) did not report their ages.

During revision of the narratives, the word “after” was unintentionally replaced with “when” in the verbal, indirect, and neutral/nonaggressive conditions for both target sexes.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Jaime L. Palmer-Hague  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0384-559X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0384-559X

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Adler N. E., Epel E. S., Castellazzo G., Ickovics J. R. (2000). Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy white women. Health Psychology, 19, 586–592. 10.1037/0278-6133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer J. (2004). Sex differences in aggression in real-world settings: A meta-analytic review. Review of General Psychology, 8, 291–322. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.8.4.291 [Google Scholar]

- Archer J. (2019). The reality and evolutionary significance of human psychological sex differences. Biological Reviews. 10.1111/brv.12507 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Arnocky S, Vaillancourt T. (2017). Sexual competition among women: A Review of the theory and supporting evidence. In Fisher M. L. (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of women and competition. Oxford University Press. 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199376377.013.3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beneson J. F., Markovits H., Thompson M. E., Wrangham R. W. (2011). Under threat of social exclusion, females exclude more than males. Psychological Science, 22, 538–544. 10.1177/0956797611402511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beneson J. F., Markovits H., Hultgren B., Nguyen T., Bullock G., Wrangham R. (2013). Social exclusion: More important to human females than males. PLoS One, 8, e55851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. L., Lewis B. P. (2004). Relational dominance and mate-selection criteria: Evidence that males attend to female dominance. Evolution and Human Behavior, 25, 406–416. 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2004.08.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan A. D., Webster G. D., Mahaffey A. L. (2011). The big, the rich, and the powerful: Physical, financial, and social dimensions of dominance in mating and attraction. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37, 365–382. 10.1177/0146167210395604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss D. M. (1989). Sex differences in human mate preferences: Evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 12, 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Buss D. M., Schmitt D. P. (1993). Sexual strategies theory: An evolutionary perspective on human mating. Psychological Review, 100, 204–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell A. (2013). The evolutionary psychology of women’s aggression. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 368, 20130078. 10.1098/rtsb.2013.0078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Campbell A., Cross C. (2012). Women and aggression. In Shackelford T. K., Weekes V. A. (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of evolutionary perspectives on violence, homicide, and war (pp. 197–217). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell A., Muncer S. (2009). Can ‘risky’ impulsivity explain sex differences in aggression? Personality and Individual Differences, 47, 402–406. 10.1016/j.paid.2009.04.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F., Erdfelder E., Lang A. G., Buchner A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fessler D. M. T., Holbrook C., Tiokhin L. B., Snyder J. K. (2014). Sizing up Helen: Nonviolent physical risk-taking enhances the envisioned bodily formidability of women. Journal of Evolutionary Psychology, 12, 67–81. 10.1556/JEP-D-14-00009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]