ABSTRACT

Background:

Mental health problems cause significant distress and impairment in adolescents worldwide. One-fifth of the world’s adolescents live in India, and much remains to be known about their mental health and wellbeing.

Aim:

In this preregistered study, we aimed to estimate the rates of depressive and anxiety symptoms, examine their relationship with indicators of wellbeing, and identify correlates of mental health among Indian adolescents.

Methods:

We administered self-report measures of depressive symptoms (PHQ-9), anxiety symptoms (GAD-7), wellbeing (WEMWBS), and happiness (SHS) to 1,213 Indian adolescents (52.0% male; Mage = 14.11, SDage = 1.48).

Results:

Findings from the PHQ-9 (M = 8.08, SD = 5.01) and GAD-7 (M = 7.42, SD = 4.78) indicated high levels of depressive symptoms and anxiety symptoms. Thirty seven percent of the sample scored above the clinical cutoff for depressive symptoms, and 30.6% scored above the cutoff for anxiety symptoms. Although measures of mental health symptoms (PHQ-9 and GAD-7) were associated with measures of wellbeing and happiness (WEMWBS and SHS), these associations were only modest (Correlation < 0.45). Female students reported higher symptoms (and worse wellbeing) compared to male students, and older students reported higher symptoms (and worse wellbeing and happiness) compared to younger students.

Conclusion:

This study highlights the high prevalence of depressive symptoms and anxiety symptoms among Indian high school students. Symptom measures correlated only modestly with measures of wellbeing and happiness, suggesting that wellbeing and happiness reflect more than the absence of internalizing symptoms. Future research is needed to identify effective and appropriate ways to promote mental health and wellness among Indian students.

Keywords: Adolescents, anxiety, depression, India, mental health, wellbeing

INTRODUCTION

Depression and anxiety are common in adolescents and contribute considerably to the global burden of disease.[1] However, reliable estimates of the prevalence of these conditions in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) have been difficult to obtain, in part due to limited awareness of mental health concerns and limited funding for mental health initiatives.[2] Research into prevalence and correlates of mental health problems is particularly warranted in India. About 250 million adolescents live in India—one-fifth of the world’s total adolescent population.

In a recent review of epidemiological studies among Indian youth, Grover et al.[3] documented an extremely wide range of point prevalence estimates of depression (ranging from 3% to 68% among school-based studies). Age, gender, and urban-rural disparities emerged in their review. The prevalence estimates they reported tended to be higher in older adolescents[4] than those obtained in studies with younger children and adolescents.[5] This may be due to intense academic pressure faced by high school students; this pressure is especially strong in 10th and 12th grade when students are preparing for high-stakes national examinations.[6] Gender may also be a risk factor, possibly due in part to gender discrimination and strict gender roles in certain parts of India.[7] Moreover, an urban-rural disparity in the incidence of psychiatric disorders has been found among Indian adults, with both depression and anxiety being significantly higher among adults inhabiting rural parts of the country.[8] However, information is scarce on such a disparity existing among Indian youths.

Additionally, there have been several limitations in previous studies and much remains to be known about the prevalence and correlates of depression and anxiety among Indian adolescents. First, many studies have reported the prevalence of depression and anxiety dichotomously—that is, they used a particular cutoff score to group people as “depressed” or “not depressed”.[5] More recent dimensional conceptualizations of psychopathology suggest that it may be useful to apply multiple thresholds or cutoffs and to distinguish between mild, moderate, and severe mood disorders.[9] Second, most previous studies of Indian adolescents have conducted exploratory analyses without registered hypotheses. Preregistering planned analyses and hypotheses can reduce the number of spurious findings, reduce the influence of biased findings, promote greater transparency, and ultimately improve the quality and reproducibility of a research base.[10] Third, few studies have measured wellbeing and happiness alongside depression and anxiety. Recently, international public health entities like the World Health Organization have argued that “positive” indicators of mental health like wellbeing and happiness ought to be considered independently from mental illnesses—that good mental health is more than the mere absence of mental disorders.[11] Nevertheless, research that simultaneously examines the prevalence of psychopathology and psychological wellbeing is currently lacking. Given these limitations and gaps in existing work, additional research is needed to understand the rates of depression and anxiety among Indian adolescents and their correlates with indicators of positive mental health.

In this study, we aimed to investigate the prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in a large and diverse community sample of Indian adolescents in secondary schools. We also examined several potential sociodemographic correlates of depression and anxiety. Prior to data analysis, we preregistered several hypotheses (https://osf.io/ae9wb) including:

H1: The prevalence of depressive symptoms (using PHQ-9 cutoffs for moderate depression[12]) will be approximately 20%.[4,5,13,14]

H2: The prevalence of anxiety symptoms (used GAD-7 cutoffs for moderate anxiety[15]) will be approximately 20%.[4,5]

H3: Female students will experience greater depressive and anxiety symptoms than male students.[4,6,16,17]

H4: Happiness and subjective wellbeing will be negatively associated with depressive and anxiety symptoms.

H5: Younger students will report greater happiness and subjective wellbeing than older students.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

We used baseline data from a study of online mental health promotion interventions conducted in Maharashtra, India.[18] With permission from school officials, we notified students and parents about the study during a school-wide assembly. Detailed information was provided regarding our aims, the study’s purpose, and expected procedures. At this time, we obtained parental consent for interested adolescents. Those interested in participating were invited to complete the survey online via Qualtrics or via pen-and-paper during study periods designated by their schools. A youth assent form was included at the beginning of this survey. Data for the present analyses were collected prior to the implementation of the interventions. Eligible participants were 1,213 adolescents (grades 7 to 12) attending English-medium secondary schools in Maharashtra (52.0% male; Mage = 14.11, SDage = 1.48). Study procedures were approved by the Sangath Institutional Review Board; Sangath is a not-for-profit, nongovernmental organization based in India that conducts research to promote mental and behavioral health community settings. IRB approval was obtained on May 21, 2019.

Procedure

Baseline data were collected from June to August of 2019 in three high schools. The three schools were chosen to reflect geographic and socioeconomic diversity within the region: one was a well-resourced urban school (School A), one was an urban school serving middle-class youths (School B), and one was a rural school serving working-class youths (School C). The survey included two attention checks which were false items randomly placed in the middle of the survey asking participants to select a specific option to indicate they are reading the questions; participants who passed at least one were included in these analyses. English is an official language in India and also the primary language of instruction at most secondary schools in Maharashtra, including all three of the schools in our study. As a result, all questionnaires were administered in English.

Measures

The full baseline questionnaire consisted of standardized measures of depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, wellbeing, happiness, perceived stress, and demographic information (e.g., age, gender, parental education). The questionnaires are described in greater detail below.

Depressive Symptoms (PHQ-9)

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) is a commonly used measure of depressive symptoms. The PHQ-9 has demonstrated strong reliability (Cronbach’s alpha of. 86-.89) and validity,[19] and it has been validated in a sample of Indian adolescents.[20] Participants are asked to rate the frequency of each item over the past two weeks. Items are scored from 0 (“Not at all”) to 3 (“Nearly every day”). Cronbach’s alpha for the present study was 0.74.

Anxiety Symptoms (GAD-7)

The GAD-7 is a commonly used measure of anxiety symptoms.[15] It shows adequate internal consistency (Cronbach alpha = 0.92) in samples of youths in North America and strong convergent, divergent, construct, and criterion validity.[15] The GAD-7 has been used extensively in cross-cultural contexts, including with students in India.[21] Participants are asked to rate the frequency of each item over the past two weeks. Items are scored from 0 (“Not at all”) to 3 (“Nearly every day”). Cronbach’s alpha for the present study was 0.82.

Wellbeing (WEMWBS)

The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale is a measure of mental wellbeing.[22] The WEMWBS has demonstrated good content validity, adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha= 0.89 in a student sample; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.91 in a general population sample), adequate test-retest reliability, and high correlation with other mental health and wellbeing scales.[22] Cronbach’s alpha for the present study was 0.75.

Happiness (Subjective happiness scale)

The Subjective Happiness Scale is a self-report measure of happiness.[23] The four-item measure has demonstrated adequate internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and validity across multiple samples and countries.[23] The Subjective Happiness Scale has also been administered to children and young adults in India.[24,25] Cronbach’s alpha for the present study was 0.65.

Perceived stress (Perceived stress scale)

The Perceived Stress Scale-4 (PSS-4) is a measure of perceived stress. The measure examines how often respondents appraise events as stressful.[26] The PSS-4 has demonstrated adequate internal consistency and validity across multiple samples.[27] The 12-item scale that the PSS-4 derives from has demonstrated adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84) and test-retest reliability (r = 0.85) in a sample of Indian adolescents.[28] Cronbach’s alpha for the present study was 0.53.

Analyses

Our analytic plan was preregistered prior to data analysis (https://osf.io/ae9wb). For our prevalence estimates, we planned to use scoring guidelines for the PHQ-9[19] and GAD-7.[15] We originally planned to examine how depression, anxiety, and subjective wellbeing vary based on class year. However, to be more consistent with the broader literature on prevalence (e.g., Sandal et al., 2017[4]), we decided to examine differences by age rather than by class year. We also chose to perform linear models, allowing us to control for covariates (e.g., assess the association between age and depressive symptoms while controlling for gender). Finally, in accordance with our preregistration, we excluded any measures that failed to demonstrate adequate internal consistency (i.e., measures with a Cronbach’s alpha less than 0.6). Thus, we excluded the Perceived Stress Scale-4 from our analyses as it did not show adequate internal consistency in the study sample.

RESULTS

Demographics

Table 1 shows participants’ demographic characteristics.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Age | 14.11 (1.48) |

|

| |

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|

| |

| Sex | |

| Female | 572 (48.0%) |

| Male | 619 (52.0%) |

| School Typea | |

| School A | 560 (46.4%) |

| School B | 257 (21.3%) |

| School C | 390 (32.3%) |

aSchool A is a well-resourced urban school, School B is a middle-class urban school, and School C is a working-class rural school

Prevalence and descriptive statistics

Table 2 shows descriptive statistics for the PHQ-9, GAD-7, WEMWBS, and Subjective Happiness Scale and correlations between these variables.

Table 2.

Correlations Between Mental Health and Wellbeing Measures

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PHQ-9 | 8.08 | 5.01 | |||

| 2. GAD-7 | 7.42 | 4.78 | 0.70** [0.67, 0.73] | ||

| 3. WEMWBS | 50.07 | 7.07 | –0.37** [–0.42, –0.32] | –0.35** [–0.40, –0.30] | |

| 4. SHS | 4.75 | 1.26 | –0.43** [–0.47, –0.38] | –0.40** [–0.45, –0.36] | 0.43** [0.38, 0.47] |

Values in square brackets indicate the 95% confidence interval for each correlation. **P<0.001

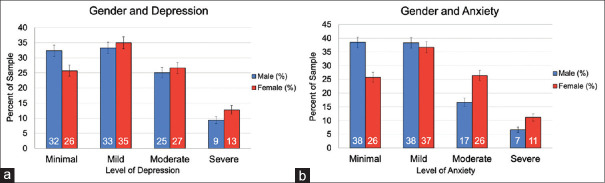

We also calculated the rates of mild, moderate, and severe depression and anxiety in our sample based on cutoffs determined from American samples.[15,19] Slightly more than a third of participants (34.1%) scored in the range of mild depression, about a quarter of participants (25.9%) scored in the range of moderate depression, and 11.1% scored in the range of severe depression. For anxiety, 37.4% of participants scored in the range of mild, about a fifth of participants (21.7%) scored in the range of moderate, and 8.9% scored in the range of severe anxiety. The prevalence of moderate to severe depressive and anxiety symptoms as observed in our sample was higher than our prediction of 20%, at 37.0% for depression, and 30.6% for anxiety, respectively.

The prevalence of depressive symptoms by gender can be seen in Figure 1a, and the prevalence of anxiety symptoms by gender can be seen in Figure 1b.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms by sex

Depressive symptoms and sociodemographic factors

We examined the relation between depressive symptoms and the sociodemographic variables of gender, age, and school using a linear model [Table 3]. Consistent with our hypothesis, there was a gender difference (b = –.91, t[1182] = –3.17, P =0.002), with female students reported experiencing greater depression (MFemalePHQ = 8.46) than male students (MMalePHQ = 7.67). The model also revealed significant effects of age (b =0.23, t[1182] = 2.31, P =.021), with older students reporting higher levels of depressive symptoms. There was a significant effect of school (b = 2.02, t[1182] = 6.15, P <.001). Post-hoc tests using Tukey’s Honest Significant Differences method revealed significant differences between School C’s and School A’s mean PHQ scores (Mean Difference = 2.05, 95% confidence interval [CI]: [1.29, 2.81], P <.001) and significant differences between School C’s and School B’s mean PHQ scores (Mean Difference = 1.86, 95% CI: [.93, 2.79], P <.001). That is, students at the rural school (School C) reported greater levels of depressive symptoms than students at the urban schools (School A and School B). See Table 3 for more information.

Table 3.

Predictors of Mental Health and Wellbeing

| Predictors | PHQ-9 | GAD-7 | WEMWBS | SHS | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| B | SE | P | B | SE | P | B | SE | P | B | SE | P | |

| (Intercept) | 4.52 | 1.44 | 0.002 | 3.74 | 1.36 | 0.006 | 59.12 | 2.01 | <0.001 | 22.28 | 1.46 | <0.001 |

| Gender (male) | –0.91 | 0.29 | 0.002 | –1.65 | 0.27 | <0.001 | 1.84 | 0.40 | <0.001 | 0.24 | 0.29 | 0.413 |

| Age | 0.23 | 0.10 | 0.021 | 0.29 | 0.10 | 0.002 | –0.75 | 0.14 | <0.001 | –0.20 | 0.10 | 0.046 |

| School B | 0.33 | 0.38 | 0.383 | –0.25 | 0.36 | 0.493 | –0.35 | 0.53 | 0.507 | –0.68 | 0.39 | 0.078 |

| School C | 2.02 | 0.33 | <0.001 | 1.33 | 0.31 | <0.001 | 2.27 | 0.46 | <0.001 | –1.03 | 0.33 | 0.002 |

Results of linear models assessing the associations between depression symptoms, anxiety symptoms, wellbeing, and subjective happiness and sociodemographic factors (bold indicates statistical significance)

Anxiety symptoms and sociodemographic factors

A linear model revealed a significant effect of gender (b = –1.65, t[1182] = –6.07, P <.001), wherein female students reported experiencing greater anxiety symptoms (MFemaleGAD = 8.17) than male students (MMaleGAD = 6.65). The model also revealed significant effects of age (b =0.29, t[1182] = 3.06, P =0.002) and school (b = 1.33, t[1182] = 4.26, P <.001). Post-hoc tests using Tukey’s Honest Significant Differences method revealed significant differences between School C’s and School A’s mean GAD scores (Mean Difference = 1.35, 95% CI: [.62, 2.08], P <.001) and significant differences between School C’s and School B’s mean GAD scores (Mean Difference = 1.75, 95% CI: [.86, 2.64], P <.001). See Table 3 for more information.

Wellbeing and sociodemographic factors

A linear model revealed a significant effect of gender (b = 1.84, t[1182] = 4.59, P <.001), wherein male students reported higher wellbeing (MMaleWEB = 50.95) than female students (MFemaleWEB = 49.21). As predicted, the model revealed a significant effect of age (b = –.75, t[1182] = –5.34, P <.001), with younger students reporting greater subjective wellbeing than older students. There was also a significant effect of school (b = 2.27, t[1182] = 4.92, P <.001). Post-hoc tests using Tukey’s Honest Significant Differences method revealed significant differences between School C’s and School A’s mean WEB scores (Mean Difference = 2.15, 95% CI: [1.06, 3.23], P <.001) and significant differences between School C’s and School B’s mean WEB scores (Mean Difference = 1.90, 95% CI: [0.57, 3.22], P = 0.002). See Table 3 for more information.

Subjective happiness and sociodemographic factors

A linear model did not detect a significant effect of gender (P >.4). As predicted, the model revealed a significant effect of age (b = –.20, t[1182] = –2.00, P =0.046), with younger students reporting greater subjective happiness than older students. There was also a significant effect of school (b = –1.03, t[1182] = –3.08, P =0.002). Post-hoc tests using Tukey’s Honest Significant Differences method revealed significant differences between School C’s and School A’s mean Subjective Happiness scores (Mean Difference = –1.11, 95% CI: [–1.88, –.33], P =.002). See Table 3 for more information.

DISCUSSION

This study estimated the prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms and identified factors associated with “positive” and “negative” indicators of mental health and wellbeing among a sample of Indian adolescents. Our findings suggest that mental health concerns were highly prevalent among our sample. Approximately one-third of adolescents scored in the range of mild depression, and an additional third scored in moderate or severe range. Similarly, about third scored in the range of mild anxiety, and an additional third scored in the range of moderate or severe anxiety. As predicted, female students and older students reported worse mental health and wellbeing (relative to male students and younger students). Notably, the associations between the “negative” measures of psychopathology (anxiety and depression) and “positive” measures of wellbeing and happiness were only modest (correlations < 0.45), whereas the association between the two measures of psychopathology were strong (correlation = 0.7). These findings reflect the notion that holistic mental health goes beyond the mere absence of symptoms to also include positive feelings of satisfaction, purpose, and happiness.[11]

Several factors may explain the elevated reports of depression and anxiety in our sample, which exceeded the prevalence estimates of our preregistered hypotheses. From a methodological standpoint, previous research in India has shown that higher prevalence estimates are obtained from screening instruments (like the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 used in this study) than from diagnostic interviews.[3] Additionally, contextual and cultural factors explain increased rates of internalizing symptoms in this sample, including economic, academic, and familial stressors. Adolescents in India commonly experience an intense pressure to succeed academically, and their academic stress has been linked to mental health difficulties.[4,17] Although academic pressure is common globally, it is possible that students in LMICs experience more intense pressure because performance in examinations can have important, sometimes irreversible, consequences for adolescents’ educational and vocational opportunities. Indeed, our estimates of depression and anxiety are similar to those that were reported in a recent study of adolescents in Kenya, which has a similar educational system.[29] Future research should directly investigate life stressors and family factors associated with poor mental health among Indian adolescents.

Consistent with our hypotheses, gender and age were associated with mental health and wellbeing. Even in western settings, mood disorders tend to be more common in female adolescents than in male adolescents.[30,31] In India specifically, gender discrimination may contribute to the elevated rates of depression and anxiety. Previous research has shown that gender discrimination is common in India, and Indian adolescents who face gender discrimination are at a higher risk of developing mental health problems.[7] We also found that older adolescents reported greater levels of depression and anxiety. Explanations for the elevated rate of mental health problems among older adolescents include social changes (e.g., increased sensitivity to peer relations), academic changes (e.g., heightened pressure to succeed academically, especially on standardized tests), and biological changes (e.g., puberty and hormonal changes) that occur throughout adolescence.[6,30,32] Finally, our exploratory analyses found that students at a rural high school reported higher symptom levels than those at urban high schools. This replicates findings of a rural-urban mental health disparity among Indian adults.[8] Overall, our findings underscore the importance of understanding demographic (e.g., age, gender) and contextual factors (e.g., urbanicity) that predict mental health risk and increasing access to mental healthcare for groups at highest risk.

Our study has several strengths including the use of culturally validated instruments, a holistic assessment of positive and negative aspects of mental health, and preregistration of key hypotheses. Nevertheless, findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. The use of self-reported screening measures may have inflated the prevalence rate of symptoms in our sample relative to studies in which clinical interviews were administered. That noted, some participants may actually have under-reported their symptoms to provide socially desirable responses or circumvent the stigma associated with mental health problems (see Wasil, Park, and DeRubeis, 2020[33] for an analysis of stigma among Indian adolescents). Finally, our findings about urban-rural mental health disparities should be considered exploratory due to the inclusion of only one rural school.

Our study also raises several avenues for future research. To understand the high rates of internalizing problems, future research could incorporate open-ended assessment techniques to elicit the kinds of problems that are most salient in adolescents’ lives[34] and how adolescents cope with these problems.[35,36] Second, future research is needed to develop effective, culturally appropriate, and scalable mental health treatments for adolescents in India. Promising approaches include interventions delivered by lay counselors,[37] interventions delivered within schools,[18] and digital mental health interventions.[38] The high rates of distress reported by adolescents in this sample underscore the urgency of efforts to disseminate and scale appropriate treatments in India and other LMICs.

Financial support and sponsorship

Akash Wasil and Sarah Gillespie received support from National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowships during the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gore FM, Bloem PJ, Patton GC, Ferguson J, Joseph V, Coffey C, et al. Global burden of disease in young people aged 10–24 years: A systematic analysis. Lancet. 2011;377:2093–102. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60512-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel V, Kleinman A. Poverty and common mental disorders in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81:609–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grover S, Raju VV, Sharma A, Shah R. Depression in children and adolescents: A review of Indian studies. Indian J Psychol Med. 2019;41:216–27. doi: 10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_5_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sandal RK, Goel NK, Sharma MK, Bakshi RK, Singh N, Kumar D. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress among school going adolescent in Chandigarh. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2017;6:405. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.219988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mishra A, Sharma AK. A clinico-social study of psychiatric morbidity in 12 to 18 years school going girls in urban Delhi. Indian J Community Med. 2001;26:71. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhasin SK, Sharma R, Saini NK. Depression, anxiety and stress among adolescent students belonging to affluent families: A school-based study. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77:161–5. doi: 10.1007/s12098-009-0260-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pillai A, Patel V, Cardozo P, Goodman R, Weiss HA, Andrew G. Non-traditional lifestyles and prevalence of mental disorders in adolescents in Goa, India. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:45–51. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.034223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reddy VM, Chandrashekar CR. Prevalence of mental and behavioural disorders in India: A meta-analysis. Indian J Psychiatry. 1998;40:149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruscio AM. Normal versus pathological mood: Implications for diagnosis. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2019;15:179–205. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050718-095644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nosek BA, Alter G, Banks GC, Borsboom D, Bowman SD, Breckler SJ, et al. Promoting an open research culture. Science. 2015;348:1422–5. doi: 10.1126/science.aab2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. Mental health: Strengthening our response. 2022. [Last accessed on 2022 Sep 10]. Available from:https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response .

- 12.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Löwe B. The patient health questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: A systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:345–59. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh MM, Gupta M, Grover S. Prevalence &factors associated with depression among schoolgoing adolescents in Chandigarh, north India. Indian J Med Res. 2017;146:205. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1339_15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wasil AR, Venturo-Conerly KE, Shinde S, Patel V, Jones PJ. Applying network analysis to understand depression and substance use in Indian adolescents. J Affect Disord. 2020;265:278–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chauhan S, Lal P, Nayak H. Prevalence of depression among school children aged 15 years and above in a public school in Noida, Uttar Pradesh. J Acad Ind Res. 2014;3:269–73. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deb S, Chatterjee P, Walsh K. Anxiety among high school students in India: Comparisons across gender, school type, social strata and perceptions of quality time with parents. Aust J Educ Dev Psychol. 2010;10:18–31. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wasil AR, Park SJ, Gillespie S, Shingleton R, Shinde S, Natu S, et al. Harnessing single-session interventions to improve adolescent mental health and well-being in India: Development, adaptation, and pilot testing of online single-session interventions in Indian secondary schools. Asian J Psychiatry. 2020;50:101980. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.101980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. Psychiatric Annals. SLACK Incorporated Thorofare; NJ: 2002. The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure 32; pp. 509–15. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ganguly S, Samanta M, Roy P, Chatterjee S, Kaplan DW, Basu B. Patient health questionnaire-9 as an effective tool for screening of depression among Indian adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:546–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jamir L, Duggal M, Nehra R, Singh P, Grover S. Epidemiology of technology addiction among school students in rural India. Asian J Psychiatry. 2019;40:30–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2019.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tennant R, Hiller L, Fishwick R, Platt S, Joseph S, Weich S, et al. The Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lyubomirsky S, Lepper HS. A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Soc Indic Res. 1999;46:137–55. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holder MD, Coleman B, Singh K. Temperament and happiness in children in India. J Happiness Stud. 2012;13:261–74. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peltzer K, Pengpid S. Subjective happiness and health behavior among a sample of university students in India. Soc Behav Personal Int J. 2013;41:1045–56. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983:385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee EH. Review of the psychometric evidence of the perceived stress scale. Asian Nurs Res. 2012;6:121–7. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Augustine LF, Vazir S, Rao SF, Rao MVV, Laxmaiah A, Nair KM. Perceived stress, life events &coping among higher secondary students of Hyderabad, India: A pilot study. Indian J Med Res. 2011;134:61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Osborn TL, Venturo-Conerly KE, Wasil AR, Schleider JL, Weisz JR. Depression and anxiety symptoms, social support, and demographic factors among Kenyan high school students. J Child Fam Stud. 2020;29:1432–43. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cyranowski JM, Frank E, Young E, Shear MK. Adolescent onset of the gender difference in lifetime rates of major depression: A theoretical model. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:21–7. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewinsohn PM, Gotlib IH, Lewinsohn M, Seeley JR, Allen NB. Gender differences in anxiety disorders and anxiety symptoms in adolescents. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;107:109. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nolen-Hoeksema S, Girgus JS. The emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence. Psychol Bull. 1994;115:424. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.3.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wasil AR, Park SJ, DeRubeis R. Stigma toward individuals with mental illness among Indian adolescents: Findings from three secondary schools and a cross-cultural comparison. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weisz JR, Chorpita BF, Frye A, Ng MY, Lau N, Bearman SK, et al. Youth top problems: Using idiographic, consumer-guided assessment to identify treatment needs and to track change during psychotherapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79:369. doi: 10.1037/a0023307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ng MY, Eckshtain D, Weisz JR. Assessing fit between evidence-based psychotherapies for youth depression and real-life coping in early adolescence. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2016;45:732–48. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2015.1041591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wasil AR, Franzen RE, Gillespie S, Steinberg JS, Malhotra T, DeRubeis RJ. Commonly reported problems and coping strategies during the COVID-19 crisis: A survey of graduate and professional students. Front Psychol. 2021;12:598557. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.598557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Osborn TL, Wasil AR, Venturo-Conerly KE, Schleider JL, Weisz JR. Group intervention for adolescent anxiety and depression: Outcomes of a randomized trial with adolescents in Kenya. Behav Ther. 2020;51:601–15. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2019.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ebert DD, Zarski AC, Christensen H, Stikkelbroek Y, Cuijpers P, Berking M, et al. Internet and computer-based cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in youth: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled outcome trials. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0119895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]