Abstract

Purpose

The study purpose was to learn and describe 1) where homeless shelter residents receive health care, 2) what contributes to positive or negative health care experiences among shelter residents, and 3) shelter resident perceptions toward health care.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews (SSIs) utilizing purposive sampling and focus group discussions (FGDs) utilizing convenience sampling were conducted at 6 homeless shelters in Seattle-King County, Washington, during July–October 2021. All residents (age ≥18) were eligible to participate. SSIs were conducted with 25 residents, and 8 FGDs were held. Thematic analysis was conducted using Dedoose.

Results

Participants received health care in settings ranging from no regular care to primary care providers. Four elements emerged as contributing positively and negatively to health care experiences: 1) ability to access health care financially, physically, and technologically; 2) clarity of communication from providers and staff about appointment logistics, diagnoses, and treatment options; 3) ease of securing timely follow-up services; and 4) respect versus stigma and discrimination from providers and staff. Participants who felt positively toward health care found low- or no-cost care to be widely available and encouraged others to seek care. However, some participants described health care in the United States as greedy, classist, discriminatory, and untrustworthy. Participants reported delaying care and self-medicating in anticipation of discrimination.

Conclusions

Findings demonstrate that while people experiencing homelessness can have positive experiences with health care, many have faced negative interactions with health systems. Improving the patient experience for those experiencing homelessness can increase engagement and improve health outcomes.

Keywords: homelessness, health care disparities, perceived discrimination, patient attitude, access

Primary health care is an important element of disease prevention, early identification of health conditions, and treatment or management of conditions.1–5 Ideally, everyone would have access to primary care networks for optimal health. However, many people in the United States (U.S.) face challenges accessing primary care.6–8 When there are significant barriers to receiving primary care services, people may wait to seek care until a health concern has progressed to needing emergency or urgent care.9–10 This pattern of care-seeking places strain on health systems.

People experiencing homelessness (PEH) may face additional challenges accessing and receiving primary health care services.11–13 Transportation and lack of insurance are significant barriers to primary care for PEH, and literature has described how patient-provider relationships influence health care seeking for some PEH.14–17 When PEH can access health care services, their experiences are often marked by stigma, bias, and discrimination from providers and facility staff.11–15 Negative health care experiences may lead people to seek out services less often when future health concerns arise, perpetuating the cycle of waiting until a health concern becomes an emergency.15 As a result, PEH may disproportionately overutilize emergency departments (EDs), and rely on EDs as their source of primary care.16 Overutilization of EDs contributes to health care costs and is an unsustainable mechanism to receive primary and preventive health care.

If patients have positive health care experiences — meaning they have few challenges accessing care and they have trusting and respectful relationships with providers — they may view health care positively and be more likely to seek out routine care and preventive screenings.12 Despite this possibility, current literature on health care experiences among PEH has focused on specific subpopulations of PEH, such as veterans or people with specific chronic conditions, and most data collection occurred before the COVID-19 pandemic. Considering the previously documented challenges receiving health care among PEH, and that health care experiences have changed drastically during the COVID-19 pandemic, the study team felt it critical to document recent experiences and perceptions among this population.

The purpose of this paper is to describe: 1) health care settings where shelter residents receive health care; 2) the elements that shape health care experiences; and 3) the current perceptions toward health care among PEH in Seattle-King County, Washington. We conclude by highlighting potential intervention points across the socioecological model to improve experiences and perceptions of health care among sheltered PEH.

METHODS

In 2021, the University of Washington (UW) conducted semi-structured interviews (SSIs) and focus group discussions (FGDs) with residents across 6 homeless shelters in Washington’s Seattle-King County metro area. Qualitative data collection was conducted to understand influencing factors on COVID-19 vaccine attitudes and intent, which included assessment of previous health care experiences and perceptions of health care. The findings presented here are a subanalysis of a larger study regarding COVID-19 vaccines.18–20 A subset of those study participants, specifically homeless shelter residents, provided data that warranted separate analysis and presentation.

Conceptual Framework

SSI and FGD question guides (Online Appendix A and Online Appendix B, respectively) were informed by a conceptual framework (not shown, described elsewhere20), stakeholder input from Public Health – Seattle & King County, and people with lived experience of homelessness. While the conceptual framework for the larger study was used to inform development of SSI and FGD guides, it was not used in this analysis. A separate conceptual framework, known as the “Iron Triangle,”21,22 was used for analyzing these data on health care experiences. The Iron Triangle was not used to inform study design or development of data collection tools; it was used to group codes and make inferences about the interplay between themes.

The Iron Triangle of health economics describes the dynamic relationship between health care cost, access, and quality.21,22 For this substudy, we conceptualized the patient experience as a microcosm of this larger tension between cost, access, and quality, and wanted to situate these factors, plus patient interactions with their provider and facility staff, as part of an entire health care experience. To do this, we distinguished between financial access (cost) and other barriers to accessing health care among PEH, presented communication and appropriate connection to follow-up care as elements informed by health care quality at an organizational and institutional level,23 then added individual and interpersonal influences among patients, providers, and other facility staff.

Participants and Recruitment

The UW study team utilized existing partnerships with 6 homeless shelters in Seattle-King County to identify residents for SSIs and FGDs. Residents from the 6 shelters were eligible to participate if they were 18 years of age or older and could complete an interview in English, Spanish, French, Amharic, or Tigrinya.

Two sampling approaches were used to identify and recruit participants for SSIs and FGDs; these are described elsewhere.18,20 Participant characteristics were proportionate to the characteristics of Seattle-King County’s population of PEH broadly.20,24 All residents who participated in SSIs and FGDs were included in this subanalysis.

Overall, 25 shelter residents participated in SSIs, and 43 unique residents participated in 8 FGDs. The majority of participants were 18–49 years of age (n=40; 54%), cisgender men (n=43, 58%), and categorized as either White (n=30, 41%) or Black/African American (n=26, 35%) race (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participating Residents in Semi-Structured Interviews and Focus Group Discussions in 6 Seattle Homeless Shelters, July–October 2021

| Participant characteristics | Total N=68, n (%) |

Semi-structured interviews (n=25) | Focus group discussions (n=43) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants per shelter site | |||

| Adult mixed 1 | 17 (25%) | 4 | 13 |

| Adult mixed 2 | 12 (18%) | 3 | 9 |

| Mixed family 1 | 11 (16%) | 4 | 7 |

| Mixed family 2 | 4 (6%) | 4 | 0 |

| Older adult male | 13 (19%) | 4 | 9 |

| Young adult | 11 (16%) | 6 | 5 |

| Gender | |||

| Cisgender man | 40 (59%) | 12 | 28 |

| Cisgender woman | 18 (26%) | 7 | 11 |

| Transgender man | 1 (1%) | 1 | 0 |

| Transgender woman | 0 (0%) | 0 | 0 |

| Non-binary | 5 (7%) | 3 | 2 |

| Other | 2 (3%) | 1 | 1 |

| Prefer not to say | 2 (3%) | 1 | 1 |

| Age group | |||

| 18–49 years | 38 (56%) | 16 | 22 |

| 50–64 years | 22 (32%) | 5 | 17 |

| 65 and older | 8 (12%) | 4 | 4 |

| Race | |||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (1%) | 1 | 0 |

| Asian | 0 (0%) | 0 | 0 |

| Black or African American | 22 (32%) | 6 | 16 |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 3 (4%) | 1 | 2 |

| White | 29 (43%) | 10 | 19 |

| Multiracial | 5 (7%) | 2 | 3 |

| Prefer not to say | 8 (12%) | 5 | 3 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | |||

| Yes | 5 (7%) | 2 | 3 |

| No | 59 (87%) | 21 | 38 |

| Prefer not to say | 4 (6%) | 2 | 2 |

| Primary language | |||

| English | 66 (97%) | 23 | 43 |

| Spanish | 2 (3%) | 2 | 0 |

Data Collection

SSI and FGD guides were piloted internally with the UW study team to assess flow and timing of questions as well as to ensure all interviewers were equally familiar and comfortable asking the questions. SSIs and FGDs were conducted from July 27 to October 14, 2021. SSIs were conducted by 1 study team member, while FGDs were conducted by 2 study team members — 1 serving as the facilitator and 1 as a notetaker. Field notes were written up within 24 hours after the SSI or FGD and shared back with the study team weekly to allow for iterative data collection.

Data Analysis

All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim using a transcription service (Dynamic Language). Interviews conducted in a language other than English were translated after transcription. For FGDs, participants picked a pseudonym to be referred to on the recording so that their names were not included in the recording or transcript. All transcription files were given a unique identifier that did not include personally identifiable information.

Inductive thematic analysis was conducted according to a conceptual framework informed by the Iron Triangle21,22 using Dedoose Version 9.0.46 (SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC). All transcripts were coded using an inductive approach. In vivo codes were generated according to specific participant responses in the transcripts. Four coders coded a single transcript together to ensure understanding of code identification; 39 transcripts were coded independently by 1 of the 4 coders, and then reviewed by an additional coder to assess consistency in code application. The rest of the transcripts were then coded independently by the 4 coders, with 18 transcripts randomly selected for review by a second coder for quality assurance. Once all codes were identified, the study team grouped codes based on patterns and themes were established based on code groupings.

Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the human subjects division of the University of Washington institutional review board (STUDY00007800). All participants were required to give informed consent to participate in SSIs and FGDs. After reading the consent script, participants were then asked for permission to audio-record the SSI or FGD. All field notes, transcripts, and participant-linking documents were stored on a secure UW server only accessible by the UW study team. All participants received a gift card as a thank-you for their time.

RESULTS

Settings Where Participants Receive Health Care

Shelter residents described a variety of settings where they receive health care (Table 2). Some mentioned that they have not been to a doctor in many years and do not have a regular care setting. Also described were recent life changes (such as recently moving to Seattle) and having not yet established a routine care provider. Other participants described going to EDs or urgent care clinics for their health needs. One participant discussed difficulties receiving health care in most hospitals because they do not have the right insurance, so they go to the ED for “something as little as a toothache.”

Table 2.

Descriptive Quotes From Participating Residents in Semi-Structured Interviews and Focus Group Discussions in 6 Seattle Homeless Shelters, July–October 2021

| Theme or subtheme | Descriptive quotes |

|---|---|

| Health care settings |

I haven't been to the doctor even for bronchitis in 12 years. Most of the time, and this is mainly because I am homeless, I would go to an ER. When you're on the streets or living in a shelter, it's really hard to get an appointment through any other hospital because most hospitals use Medicare and Medicaid [and I don’t have that]. I go to the ER if I have something as little as a toothache. [I’ve] found over-the-counter things I could use to manage my condition. |

| Elements shaping health care experiences | |

| Ability to access health care |

Sometimes, if I had an appointment and then the bus sometimes would skip over bus stops even with a lot of people or not much, so I'd be late sometimes, and then they say because I was late, they gave it to somebody else. When I resigned from my job, the health care system was very good to me. They helped me out a lot. Made sure that I didn't have any bills, no other stresses on me, and nothing like that. The health care system, it does help. Well, with the COVID-19 pandemic hitting the world, it's made getting health care, even general appointments, difficult. [It’s been difficult] having to make sure that I had phone service for video calls, because, ‘We're not seeing any patients in the office. We will do a video chat.’ |

| Level of clear communication from health care facilities and staff |

I just got an email now about an appointment I don't know anything about, and it's at the Art Institute, which I have no clue to where that is. That’s what I was talking about. Lack of communication. I'm looking around and thinking, ‘These are things I need, on the walls.’ They're telling me where I need to go. They're being so pleasant, welcoming, and open. I have had a wonderful experience. |

| Ease of securing timely follow-up care | The problem I have is scheduling so far out. I go to the emergency room and they refer you to someone and tell you how to follow up. When you do, it's like, ‘Okay, you need to be there at this time.’ I can't make that. The next appointment is six weeks out, and that's hard when you don't know what's going on with your body. |

| Respect vs stigma or discrimination |

The moment they saw my chart that I was homeless, they said, ‘You need to go somewhere after this. You need to have bed rest and such an amount of time.’ I'm like, ‘Oh, well, good luck me finding a place like that,’ because they don't like you to lay around town. Their whole demeanor changes. You could just see the change on their face. They think I'm just exhibiting drug-seeking behavior, which I'm not. They find out I'm homeless and I see the change on their face. ‘Oh, yes, homeless. Well, she's a piece of shit.’ It's gone to the point of like, ‘Oh my gosh, I’m actually being listened to and valued in a clinical setting’ because previous experiences were not that way. In previous experiences, I have to take double the amount of time to explain everything and that's frustrating and hard to have to keep doing. When we got to the hospital, it’s the usual, ‘Oh, she's homeless. Let's get her the hell out of here’ that I've encountered so many times. It's like the moment they find out you're homeless, they don't take it quite as seriously. |

| Current perceptions of health care | |

| Positive perceptions |

It's really good because if I didn't have health care who knows where I would be. Shout out free health care, man. It's been awesome. I want to teach my kids about it and how to get it. It's important. |

| Neutral perceptions |

I don't really have any feelings about it. It's neutral. If I need it, I use it. If I don't need it, I don't think about it. I have neutral feelings about health care. |

| Negative perceptions |

It's very classist. If you're bottom of the barrel, have fun scraping. My ability to make money shouldn't be the priority of my health and it is, that’s how it works. We have systems based around failure over success. It's really sad. I have not gone to a doctor because I’ve already filed bankruptcy once. I really don't want to have to file it again. There's been times that it's like, ‘Okay, let's play the game panic attack or heart attack.’ As usual, the staff that are responsible for billing are like, ‘I want 600 pieces of information and you need to sign over your firstborn child.’ It's absolutely ridiculous. I know so many people that have been impacted by the financial side of health care in this country to the point of being bankrupted, to the point of cashing in funds that were supposed to be for retirement. I don't trust doctors from my experiences. When I would go out because I was sick – and this is mainly because I am homeless – I would go to an ER because when you're on the streets or living in a shelter, it's really hard to get an appointment. I have constantly dealt with unreliability. |

ER, emergency room.

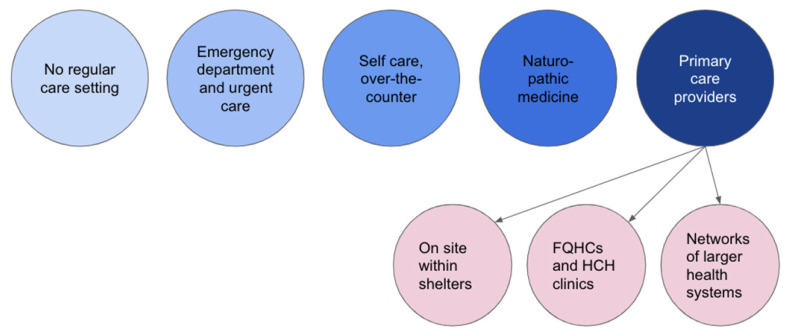

In some instances, participants avoided health care clinics and relied on over-the-counter medications from drug stores or pharmacies to manage their symptoms. Others described knowing basic first aid and being able to take care of their health issues on their own. Some described primarily using holistic healing centers and naturopathic medicine for their health concerns, while others described established primary care provider relationships, naming specific providers and clinics. Participants reported receiving care primarily from onsite clinics at homeless shelters, community-based federally qualified health centers or health care for the homeless clinics, and from larger health care networks in the Seattle area such as the UW Medical System (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Settings where residents of 6 homeless shelters in Seattle-King County received health care during July–October 2021. FQHCs, federally qualified health centers; HCH, Health Care for the Homeless.

Elements That Shaped Previous Health Care Experiences

When asked to share about previous experiences receiving health care, participants described experiences with health care across the life course; some reflected on experiences the week prior, while others reflected on experiences in childhood or adolescence. Across all experiences, 4 elements emerged as being able to influence if the participant viewed their experience positively, negatively, or neutrally: 1) ability to access care physically, financially, and technologically; 2) clarity of communication from facility staff and care providers; 3) the timeliness and ease of follow-up care; and 4) respect versus stigma/discrimination from health care providers and staff.

1) Ability to Access Health Care

Health care access was described in 3 components: (a) physical access, including transportation and distance to a facility; (b) financial access, including having health care insurance and affording medical bills; and (c) technological access to the facility and medical records, which became more challenging during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Participants described facilitators and challenges around physical access to health care services. Some residents expressed that having clinics within their homeless shelter made it easy for them to access their providers and receive care. Other participants described challenges getting to their health care facilities. Specifically, relying on public buses that come at unpredictable times can lead to missed appointments.

In addition to physically accessing a health care facility, participants described positive and negative financial and insurance-related components to accessing care. Not all nearby facilities accepted Medicare or Medicaid, two common insurance plans for residents in shelters. Participants also shared experiences arriving at health care facilities and being denied care because they did not have insurance and could not pay up front. In contrast, other participants described experiences where services were low- or no-cost or medical bills were covered, which made the experience positive.

Participants reported that the COVID-19 pandemic amplified challenges around technological barriers to health care. Many health care providers switched to telehealth, providing services by video call and phone. Shelter residents described that they, along with others experiencing homelessness, either did not have phones or did not have phones that could support video calls. This prevented them from being able to access the health care facility, as no alternatives were provided to them.

2) Level of Clear Communication From Health Care Facility Staff

Participant experiences also elicited variations in verbal and nonverbal communication from health care staff. Clarity of communication from staff, including administrative or facility staff and clinical care providers, influenced participants’ perceptions of their health care experiences. Clear communication was not just important when discussing specific health conditions and treatment plans, but also when discussing the logistics of the appointment. Facilities that sent appointment reminders and asked about transportation to follow-up appointments facilitated health care access. In other instances, lack of clear communication around next steps for treatment and scheduling led to confusion, negatively influencing patient experiences.

Participants described how visual communication within a facility made them feel positively about their experience. Specifically, signage on the walls and arrows on the floor directing people where to check-in, where to wait to be called back by a provider, and where to go to schedule follow-up appointments led to positive perceptions of their experience.

3) Ease of Securing Timely Follow-Up Care

The third element that emerged was if patients felt there was clear instruction and support to receive timely follow-up services. Participants described experiences where the next steps to receive follow-up care were unclear. In some instances, patients were expected to contact other specialists, but other times they were supposed to wait for a call from another office. Other participants described positive experiences where health care staff provided support to schedule and attend follow-up visits. Participants described feeling overwhelmed with numerous follow-ups and that having health care staff schedule these appointments for them was helpful.

Participants also noted that timeliness of follow-up care was a factor in creating positive or negative experiences. One participant described a follow-up appointment with a specialist that was scheduled 6 weeks in advance, which was too far ahead. In many instances, residents of homeless shelters had difficulties planning ahead or had symptoms that needed more urgent relief.

4) Respect vs Stigma or Discrimination

The final element in participant health care experiences was the level of respect and sensitivity displayed by providers. Many participants described experiencing stigma or discrimination in health care settings based on race, ethnicity, nationality, housing or homelessness status, and gender identity. A common expression from participants was that one could see a physical change on the provider’s face or hear a change in their tone once they found out their patient was experiencing homelessness.

Shelter residents described how providers often assumed the resident had malicious intent because of one or more of their identities. When providers made assumptions about these patients based on their housing status, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, or gender identity, participants described receiving subpar care, or care that was not sufficient for their perceived needs. Participants described encounters where their symptoms were dismissed by providers and that the prescribed treatments or medications did not resolve their issue. In some instances, patients were expecting that certain tests should be run or that certain treatment options should be discussed. When the expected tests or treatment options were not even mentioned, they were left feeling like their concerns were not heard and the care they received was not sufficient for their needs.

Furthermore, participants shared that perceived stigma and discrimination often led to them being “rushed out” of health care encounters and facilities. Participants described how feeling deprioritized or unimportant to providers led to negative experiences. On the other hand, when participants had health care experiences where they felt heard, listened to, and valued, they immediately noticed how different the encounter went. They were more likely to leave these visits feeling positively about the experience.

Current Perceptions of Health Care

After sharing previous experiences in health care, participants described their current perceptions toward health care in the U.S. References to health care included multiple layers of the health system; some participants shared perspectives on their specific provider or primary care facility as a part of the health system, while others focused on health care as a societal structure made up of large actors (such as insurers) with their own norms. Participants also described perceptions toward health care as a service to be received, separate from a structure or system. While participants were not asked how they define health care, current perceptions spanned across individuals that make up a health system and the health system itself. Regardless of the conceptualization of health care, perceptions are presented as positive, neutral, or negative.

Positive perceptions of health care at the most proximal level to participants included positive feelings toward their current health care provider or facility. Participants described confidence that their provider, if they had one, will meet their needs and cares about their livelihood, with personal relationships and connections being very important. When thinking about health care as a service, participants shared that receiving health care is important. At a systems level, health care was viewed as critical for some participants. Particularly, the ability to access free or low-cost health care services was crucial. One participant went as far as to say that they would not know where they would be without free health care, implying that being able to receive free services is a critical component to their life needs.

Some participants described neutral perceptions of health care, as neither positive nor negative. Others described not having feelings about health care but accessing services if they need them. When they were not in need of health care services, they often did not think about it.

Participants described numerous negative perceptions of health care. Participants mentioned that they expect to be treated without respect by health care providers and, as a result, hesitate to seek care. Participants mostly described negative perceptions of health care as a system. Specifically, they mentioned that the U.S. health care system is classist; only people with money will get good services and people without money will get the “bare minimum” of care. While some participants positively described the ability to access free care as an essential service, participants also described that the level of care received at free clinics is not as “good” or comprehensive as the level of care that would be received at other health care facilities.

Relatedly, there were also mentions of fear toward the financial burden of health care. Some participants described previous experiences that forced them to declare bankruptcy, and they did not want to take that risk again, thus avoiding health care services. Others had described how those in their lives had struggled to financially recover from large health care bills, which led participants to feel the risk of seeking health care was not worth taking if it would result in even further financial troubles. Other participants mentioned that they do not trust doctors broadly, and that they believe the U.S. is too focused on global health issues when they should be focused on caring for all U.S. citizens. In summary, participants who shared negative perceptions of health care described delaying care-seeking, avoiding health care, and resorting to over-the-counter medications or self-care for health concerns.

DISCUSSION

This study describes previous health care experiences and current (ie, mid-COVID-19 pandemic) perceptions of health care among PEH in Seattle-King County. Four elements emerged that influenced health care experiences, including the ability to access health care, the level of clear communication from health care providers, ease of securing timely follow-up, and experiences of respect, stigma, and discrimination from health care providers. Regardless of positive or negative health care experiences, PEH reported a wide spectrum of perceptions of health care. Participants described feeling like health care is available, accessible, and adequate to people with money and not available, accessible, or adequate for PEH. However, some PEH did note that utilizing no- or low-cost health care services has been beneficial.

Previous experiences with health care providers can be a key building block on which PEH make individual health-related decisions. These findings give us insight into factors that may influence decision-making around COVID-19 and other vaccinations, as well as general care-seeking. If PEH have negative experiences with health care or have negative perceptions of health care, they may be more likely to delay care-seeking and resort to emergency departments for health needs. Understanding current perceptions of health care among PEH will allow for tailored messaging and outreach for future public health efforts.

These findings also complement existing literature. Most existing research around this topic explores the individual elements in depth, while this paper summarizes health care experiences holistically.25–30 Additionally, this is the first assessment of health care experiences and perceptions among the population of adults experiencing sheltered homelessness in Seattle since the onset of the pandemic. Previous literature on this population in Seattle-King County has focused on infectious disease burden, adolescents and youth, and specific subpopulations of PEH (women only, injection drug users only, etc).31–38 The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on perceptions of health care among PEH has yet to be explored. This study provides insights into the experiences and perceptions at a critical and unique point in time — 1.5 years into the pandemic. As the U.S. has moved into an endemic state of COVID-19, future research can explore how health care experiences and perceptions change as the population of PEH changes.

In light of participant’s health care experiences, possibilities across all levels of the socioecological model emerge. While interventions to improve experiences for all patients are worthwhile, those efforts may not translate the same way for PEH. By focusing on tailored interventions to improve experiences of PEH and other people on society’s margins, health care experiences will naturally improve for all. If more people felt positively toward health care, they may be more likely to seek care early and receive preventive services, ultimately reducing the burden of numerous diseases. There are opportunities to explore the range of influences on health care perceptions. This study only explored previous experiences, but the influence from social networks on current perceptions is not clear. Further study may illuminate where else action can be taken to improve perceptions. Also, health care settings can consider opportunities to improve verbal and nonverbal communication. Posting signs with clear arrows and directions, providing written instruction on where to go, and handing out information sheets with phone numbers to call for follow-up care may improve patient experiences.

At the community and societal levels, organizations can consider updating lists of free or low-cost health care facilities in the area, with transportation routes to each clearly indicated. Additional funding to homeless service sites could facilitate the transportation of shelter residents directly to health care facilities or establish onsite health care providers. During COVID-19, the switch to telehealth showed great promise for keeping PEH connected to care.39 This was partly facilitated by policy-level changes that allowed providers to be reimbursed for a wider range of telehealth services. By instituting these policy changes longer-term, PEH may be able to access care earlier and often. Expanding access to telehealth services for PEH would need to be buttressed by provision of technological resources and supplies for maximum access to and engagement with these services.

Study Limitations

This substudy is subject to limitations. Health care experiences and current health care perceptions were not the primary focus of the interviews conducted for the parent study. As a result, opportunities for further probing and exploration of the concepts described may have been missed. Specifically, it is unclear what kind of “weight” each of these factors hold in determining if experiences are positive, negative, or neutral. For example, we were unable to determine if access to health care financially mattered more to patients in determining one’s perception of a health care experience than the level of respect and kindness displayed by providers and facility staff.

Additionally, the linkages between previous experiences and current perceptions of health care are not clear in these data. We tried to map descriptions of positive and negative experiences with positive and negative perceptions but were not able to identify clear patterns. We are not able to say if a certain number of negative experiences will lead to a negative perception, nor are we able to comment on other possible factors that may influence perceptions toward health care (eg, if hearing about others’ health care experiences influences perceptions).

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, previous health care experiences, especially negative ones, may affect how people experiencing homelessness seek care and engage with health systems. While some people have positive perceptions toward health care, many participants reported negative perceptions. If health care experiences and perceptions are improved, those who are currently homeless may be more likely to seek health care, reducing the utilization of emergency departments and maximizing possibilities for optimal health.

Patient-Friendly Recap.

People experiencing homelessness in the Seattle area were interviewed about their past experiences with health care and about how they currently feel toward health care.

Study participants shared that they can have a hard time getting health care — it’s too expensive, it’s far away, and they don’t always have transportation.

They also described feeling judged by health care providers due to their homeless status. Because they did not want to be treated differently, they avoided going to a clinic.

While some individuals were able to go to free clinics for care, many others perceived health care as only beneficial to people who have money, which can make them feel unwelcome in clinics.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Public Health – Seattle & King County, each of the shelter managers, and shelter staff who facilitated the data collection for this project. Additionally, we thank each of the participants for their time and for sharing their experiences and thoughts.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Study design: Meehan, Cox, Thuo, Rogers, Lo, Manns, Rolfes, Chow, Chu, Mosites, Al Achkar. Data acquisition or analysis: Meehan, Cox, Thuo, Rogers, Link, Martinez, Lo, Manns, Chow, Chu, Mosites, Al Achkar. Manuscript drafting: Meehan, Cox, Mosites, Al Achkar. Critical revision: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Chu reports consulting with Ellume, Abbvie, Pfizer, and The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. She has received research funding from Gates Ventures and Sanofi Pasteur and support and reagents from Ellume and Cepheid outside the submitted work. There are no other conflicts of interest to report.

Funding Sources

This work was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through a Broad Agency Agreement with the University of Washington. The findings and conclusions of this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Shi L. The impact of primary care: a focused review. Scientifica (Cairo) 2012;2012:432892. doi: 10.6064/2012/432892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedberg MW, Hussey PS, Schneider EC. Primary care: a critical review of the evidence on quality and costs of health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:766–72. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83:457–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu KT. Usual source of care in preventive service use: a regular doctor versus a regular site. Health Serv Res. 2002;37:1509–29. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.10524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blewett LA, Johnson PJ, Lee B, Scal PB. When a usual source of care and usual provider matter: adult prevention and screening services. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1354–60. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0659-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dickman SL, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S. Inequality and the health-care system in the USA. Lancet. 2017;389:1431–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30398-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bodenheimer T, Pham HH. Primary care: current problems and proposed solutions. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:799–805. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Douthit N, Kiv S, Dwolatzky T, Biswas S. Exposing some important barriers to health care access in the rural USA. Public Health. 2015;129:611–20. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams JG. Emergency department overuse: perceptions and solutions. JAMA. 2013;309:1173–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McWilliams A, Tapp H, Barker J, Dulin M. Cost analysis of the use of emergency departments for primary care services in Charlotte, North Carolina. N C Med J. 2011;72:265–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ensign J, Panke A. Barriers and bridges to care: voices of homeless female adolescent youth in Seattle, Washington, USA. J Adv Nurs. 2002;37:166–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davies A, Wood LJ. Homeless health care: meeting the challenges of providing primary care. Med J Aust. 2018;209:230–4. doi: 10.5694/mja17.01264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pendyal A, Rosenthal MS, Spatz ES, Cunningham A, Bliesener D, Keene DE. “When you’re homeless, they look down on you”: a qualitative, community-based study of homeless individuals with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2021;50:80–5. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nickasch B, Marnocha SK. Healthcare experiences of the homeless. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2009;21:39–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leggio WJ, Giguere A, Sininger C, Zlotnicki N, Walker S, Miller MG. Homeless shelter users and their experiences as EMS patients: a qualitative study. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2020;24:214–9. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2019.1626954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kushel MB, Perry S, Bangsberg D, Clark R, Moss AR. emergency department use among the homeless and marginally housed: results from a community-based study. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:778–84. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.5.778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chelvakumar G, Ford N, Kapa HM, Lange HLH, McRee AL, Bonny AE. Healthcare barriers and utilization among adolescents and young adults accessing services for homeless and runaway youth. J Community Health. 2017;42:437–43. doi: 10.1007/s10900-016-0274-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cox SN, Rogers JH, Thuo NB, et al. Trends and factors associated with change in COVID-19 vaccination intent among residents and staff in six Seattle homeless shelters, March 2020 to August 2021. Vaccine X. 2022;(12):100232. doi: 10.1016/j.jvacx.2022.100232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chu HY, Boeckh M, Englund JA, et al. The Seattle Flu Study: a multiarm community-based prospective study protocol for assessing influenza prevalence, transmission and genomic epidemiology. BMJ Open. 2020;10(10):e037295. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cox SN, Thuo NB, Rogers JH, et al. A qualitative analysis of COVID-19 vaccination intent, decision-making and recommendations to increase uptake among residents and staff in six homeless shelters in Seattle, WA, USA. J Soc Distress Homeless. Epub 2023 Apr 6. [DOI]

- 21.Kissick WL. Medicine’s Dilemmas: Infinite Needs Versus Finite Resources. Yale University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delaronde S. The Iron Triangle of health care: access, cost and quality. [accessed August 4, 2022]. Posted February 6, 2019. https://insideangle.3m.com/his/blog-post/the-iron-triangle-of-health-care-access-cost-and-quality/

- 23.Beauvais B, Kruse CS, Fulton L, et al. Testing Kissick’s Iron Triangle — structural equation modeling analysis of a practical theory. Healthcare (Basel) 2021;9(12):1753. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9121753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Office of Policy Development and Research, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. AHAR: Part 1 – PIT estimates of homelessness in the U.S. 2020. [accessed January 3, 2023]. Published March 2021. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/ahar/2020-ahar-part-1-pit-estimates-of-homelessness-in-the-us.html .

- 25.Mejia-Lancheros C, Lachaud J, O’Campo P, et al. Trajectories and mental health-related predictors of perceived discrimination and stigma among homeless adults with mental illness. PLoS One. 2020;15(2):e0229385. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wen CK, Hudak PL, Hwang SW. Homeless people’s perceptions of welcomeness and unwelcomeness in healthcare encounters. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1011–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0183-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wrighting Q, Reitzel LR, Chen TA, et al. Characterizing discrimination experiences by race among homeless adults. Am J Health Behav. 2019;43:531–42. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.43.3.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weber M, Thompson L, Schmiege SJ, Peifer K, Farrell E. Perception of access to health care by homeless individuals seeking services at a day shelter. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2013;27:179–84. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haley RJ, Woodward KR. Perceptions of individuals who are homeless. Healthcare access and utilization in San Diego. Adv Emerg Nur J. 2007;29:346–55. doi: 10.1097/01.TME.0000300117.17196.f1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skosireva A, O’Campo P, Zerger S, Chambers C, Gapka S, Stergiopoulos V. Different faces of discrimination: perceived discrimination among homeless adults with mental illness in healthcare settings. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:376. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rogers JH, Link AC, McCulloch D, et al. Characteristics of COVID-19 in homeless shelters: a community-based surveillance study. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:42–9. doi: 10.7326/M20-3799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chow EJ, Casto AM, Roychoudhury P, et al. The clinical and genomic epidemiology of rhinovirus in homeless shelters – King County, Washington. J Infect Dis. 2022;226(Suppl 3):S304–14. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiac239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rogers JH, Cox SN, Hughes JP, et al. Trends in COVID-19 vaccination intent and factors associated with deliberation and reluctance among adult homeless shelter residents and staff, 1 November 2020 to 28 February 2021 – King County, Washington. Vaccine. 2022;40:122–32. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tenner AD, Trevithick LA, Wagner V, Burch R. Seattle YouthCare’s prevention, intervention, and education program: a model of care for HIV-positive, homeless, and at-risk youth. J Adolesc Health. 1998;23(2 Suppl):96–106. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rogers JH, Brandstetter E, Wolf C, et al. 2318. Prevalence of influenza-like illness in sheltered homeless populations: a cross-sectional study in Seattle, WA. (abstr.) Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(Suppl 2):S795. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofz360.1996. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ensign J. Reproductive health of homeless adolescent women in Seattle, Washington, USA. Women Health. 2000;31:133–51. doi: 10.1300/j013v31n02_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Golden MR, Lechtenberg R, Glick SN, et al. Outbreak of human immunodeficiency virus infection among heterosexual persons who are living homeless and inject drugs – Seattle Washington, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:344–9. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6815a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buskin SE, Erly SJ, Glick SN, et al. Detection and response to an HIV cluster: people living homeless and using drugs in Seattle, Washington. Am J Prev Med. 2021;61(5 Suppl 1):S160–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2021.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marcus R, Meehan AA, Jeffers A, et al. Behavioral health providers’ experience with changes in services for people experiencing homelessness during COVID-19, USA, August-October 2020. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2022;49:470–86. doi: 10.1007/s11414-022-09800-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.