Abstract

Purpose

This study investigated how cancer diagnosis and treatment lead to career disruption and, consequently, loss of income and depletion of savings.

Design

This study followed a qualitative descriptive design that allowed us to understand the characteristics and trends of the participants.

Method

Patients recruited (n = 20) for this study were part of the University of Kansas Cancer Center patient advocacy research group (Patient and Investigator Voices Organizing Together). The inclusion criteria were that participants must be cancer survivors or co-survivors, be aged 18 years or older, be either employed or a student at the time of cancer diagnosis, have completed their cancer treatment, and be in remission. The responses were transcribed and coded inductively to identify themes. A thematic network was constructed based on those themes, allowing us to explore and describe the intricacies of the various themes and their impacts.

Results

Most patients had to quit their jobs or take extended absences from work to handle treatment challenges. Patients employed by the same employer for longer durations had the most flexibility to balance their time between cancer treatment and work. Essential, actionable items suggested by the cancer survivors included disseminating information about coping with financial burdens and ensuring that a nurse and financial navigator were assigned to every cancer patient.

Conclusions

Career disruption is common among cancer patients, and the financial burden due to their career trajectory is irreparable. The financial burden is more prominent in younger cancer patients and creates a cascading effect that financially affects close family members.

Every year more than 1.7 million Americans are diagnosed with cancer. Because of existing system-level factors, every cancer patient experiences financial toxicity (FT) because of high treatment costs, which leads to adverse health outcomes (1). FT was first coined in 2009 to describe the clinical relevance of financial burden, particularly in cancer treatment (1,2). Regardless of insurance type or socioeconomic status, patients are vulnerable to adverse economic consequences following a cancer diagnosis. FT affects the entire family, most severely affecting spouse caregivers, whose assets, income, and expenses are often inextricably linked to the patient (3,4).

The financial burden on individuals can arise from several factors. Every cancer patient has different needs and is at a different stage of life, and treatment can vary in complexity depending on the cancer type and stage. Compared with individuals without a history of cancer, cancer survivors have greater out-of-pocket (OOP) costs for medication and cancer treatment, even many years after the initial diagnosis (5). Because of high OOP costs and reduced income from work impairment, cancer survivors are more likely to delay, forego, or adhere poorly to their treatment (6).

Recent advancements in technology and medication have increased cancer survival rates, but it is important to understand how patients survive the posttreatment consequences of their cancer treatment (7). Most cancer patients must deal with the new reality of chronic late effects caused by their treatment or enduring damage from chemotherapy, radiation, surgery, or medication (8). Typical late effects among cancer patients include physical, cognitive, and emotional distress (9). Furthermore, cancer patients undergo disruptive processes, resulting in life-altering changes that may negatively restrict mobility and physical activity, causing negative self-perception (10-12). For example, immobility because of lack of movement may be caused by joint pain, muscle pain, and stiffness; malnutrition; cancer metastases; medication; anxiety; or depression (13). A previous study stated that it is essential for health-care professionals to describe cancer patients’ journeys to set realistic expectations of the hardships they encounter during treatment (14).

However, qualitative studies evaluating the FT are limited. There are barriers to capturing cancer patients’ experiences via in-person interviews, such as limited physical mobility, limited social exposure due to the potential spread of infection, and lack of transportation. Owing to the recent pandemic, there has been a paradigm shift with institutional review boards allowing for remote consent and remote interviewing, which has increased accessibility.

Most patients with cancer face a loss of income due to job loss or the long gap they develop in their work history because of cancer treatment. In addition to the loss of income, cancer patients can also lose insurance and employer benefits tied to their employer and employment status. To further explore these phenomena, we conducted a qualitative study to identify themes around how career disruption, limitations in financial earnings, coping methodologies adopted, and the depletion of savings have led to FT among cancer patients.

Methods

The University of Kansas Medical Center institutional review board reviewed and approved this study (STUDY00148394). Informed consent was obtained from all study participants according to institutional guidelines.

We used a qualitative descriptive study design to conduct this research, as we aimed to identify the characteristics, frequencies, trends, and themes that lead cancer patients to career disruption, savings depletion, and coping mechanisms (15).

Patient and Investigator Voices Organizing Together (PIVOT) is a patient research advocacy initiative at the University of Kansas Cancer Center. PIVOT allows cancer survivors, co-survivors, and researchers to work together to design research that may lead to improved treatments and therapies. We partnered with PIVOT to recruit participants (16). A link to the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) registration survey was distributed via email by the PIVOT staff to all PIVOT members.

The survey captured patients’ gender, race, ethnicity, cancer diagnosis, educational background, marital status, employment status, and household income. In addition to the survey questions, the participants electronically consented to participate in the study. Consenting was performed via the REDCap platform, where participants read and electronically signed the consent. Consent covered critical aspects such as privacy protection, commitment for an in-depth (1-hour) interview, and a withdrawal option. Once the survey and consent were completed, the corresponding author coordinated scheduling with the participants via email. Once the times were decided, meeting invites were sent, and links were included for an in-depth zoom interview. During the scheduled interview, participants were reminded about the purpose of the interview and were told their answers would be recorded. After oral consent to record, the interviewer started recording the session.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for this study specified that a participant must be a cancer survivor or a cancer co-survivor aged 18 years or older, be either employed or a student at the time of their cancer diagnosis, have completed their cancer treatment, and be in remission.

The interview guide was developed using common themes found in the academic literature and built on the biopsychosocial model designed by late George Engel (17). This design utilizes the following 7 pillars: self-awareness, active cultivation of trust, emotional style characterized by empathic curiosity, self-calibration to reduce bias, education and emotion to assist with diagnosis and form a therapeutic relationship, using informed intuition, and communicating clinical evidence to foster dialogue (17,18). It asked questions within the following domains: demographics, cancer diagnosis and treatment journey, financial situation, coping mechanisms, and other information relevant to the financial burden of cancer diagnosis and treatment.

After an interview guide was developed, which was iterated based on feedback from PIVOT members, we randomly chose 5 cancer survivors with the help of a PIVOT coordinator. In the first iteration, patient feedback was solicited regarding wording appropriateness, interview guide flow, and missed opportunities. Patients suggested softening the wording around earnings, savings, and income. Following the revision, the second iteration (the same 5 patients from round 1 were involved) received recommendations to rearrange questions to better align with our overarching aim. The audio of the interviews was digitally recorded and transcribed professionally.

Steps were followed strictly as described under Sterling’s guidelines around analyzing interview data (18).

Step 1: Become familiar with the data.

Step 2: Generate initial codes.

Step 3: Search for themes.

Step 4: Review themes.

Step 5: Define themes.

Step 6: Develop thematic network.

The first author consulted with co-authors after coding the first 7 transcripts to ensure rigor and mitigate bias. They discussed the codebook, resolving differences in their understandings of code definitions by consensus, consistent with the constant-comparative process. The first author coded the next 4 transcripts, consulting again with co-authors after the 11th transcript. At that point, they made minor revisions to the codebook by consensus, and the first author reviewed all previous coding and reached code saturation during the 16th interview, meaning no new codes emerged. Data from our 18 codes were further analyzed using thematic network analysis, which created organizing themes from the basic coded units of data, then grouped organizing themes into global themes. These global themes primarily comprised factors that directly influenced participants’ finances due to cancer. The first author assembled the thematic network after completing all coding and finalizing the codebook. We managed the coding, codebook development, and thematic network analysis using NVivo Pro (19). Additional details about the study design, data collection, and data analysis used for the study are described in detail in the Supplementary Material (available online).

Results

Twenty participants responded and agreed to be interviewed to share their experiences out of the 23 participants who had initially signed up for the study. Each interview lasted for 40-50 minutes. The participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1. We had 2 co-survivors out of the entire sample size of 20. The gender we captured at the time of consenting included the patient’s gender.

Table 1.

Participants characteristics

| Characteristics | Count, No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 21 (91.3) |

| Male | 2 (8.7) |

| Race | |

| Asian | 2 (8.7) |

| Black or African American | 3 (13.04) |

| White | 18 (78.26) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 23 (100) |

| Age group, y | |

| 65 and older | 4 (17.4) |

| 19-64 | 19 (82.6) |

| Marital status | |

| Divorced | 1 (4.35) |

| Married | 13 (56.52) |

| Separated | 1 (4.35) |

| Single | 6 (26.09) |

| Widowed | 2 (8.7) |

| Employment status | |

| Homemaker | 1 (4.35) |

| Student | 2 (8.7) |

| Employed for wages | 15 (65.22) |

| Out of work but not currently looking for work | 1 (4.35) |

| Retired | 1 (4.35) |

| Unable to work | 3 (13.04) |

| Household income | |

| $10 000-$59 999 | 8 (34.78) |

| $60 000-$79 999 | 3 (13.04) |

| $80 000-$99 999 | 6 (26.09) |

| $100 000-$149 999 | 2 (8.7) |

| $150 000 or more | 4 (17.40) |

| Education level | |

| Bachelor’s | 11 (47.82) |

| Master’s and above | 9 (39.14) |

| Unknown | 3 (13.04) |

| Cancer stage | |

| 1 | 4 (17.39) |

| 2 | 9 (39.13) |

| 3 | 4 (17.40) |

| 4 | 2 (8.7) |

| Unknown | 4 (17.38) |

| Cancer type | |

| Breast | 15 (65.22) |

| Colon | 2 (8.7) |

| Lymphoma | 4 (17.4) |

| Oral | 1 (4.35) |

| Thyroid | 1 (4.35) |

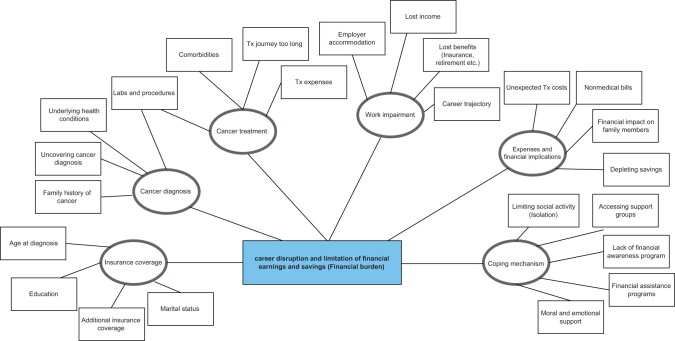

Our study uncovered where, how, and why cancer patients incur a financial burden. The coding and identification of themes are highlighted in Table 2. Themes were arranged during the construction of the thematic network, as depicted in Table 3, and an organizing theme was derived that best described these basic themes, as identified in Table 2.

Table 2.

Coding and identification of themesa

| Codes (Step 1) | Issues highlighted | Themes identified (Step 2) |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dx = diagnosis; Tx = treatment.

Table 3.

Basic themes to organizing themes to global themesa

| Basic themes | Organizing themes | Global themes |

|---|---|---|

|

Insurance | Career disruption and limitation of financial earnings and savings (financial burden) |

|

Cancer diagnosis | |

|

Cancer Tx | |

|

Expenses and financial implications | |

|

Work impairment | |

|

Coping mechanism |

Tx = treatment.

Based on Sterling’s guidelines for designing a thematic network diagram, we ensured that there were at least 4 basic themes and no more than 15 basic themes under each organizational theme. Utilizing basic, organizing, and global themes, a weblike network was crafted to describe thematic relationships (18). The thematic network is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Thematic network, illustrating the financial burden among the cancer patients. Tx = treatment.

We articulated the thematic network, starting with the organizing themes of insurance coverage, cancer diagnosis, cancer treatment, work impairment, expenses and financial implications, and coping mechanisms, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Organizing theme 1: insurance

Insurance coverage is the first organizing theme. The insurance coverage that the patients had at diagnosis varied statistically significantly, with some covered by their spouse’s insurance, some with inadequate insurance, and one who was uninsured.

Organizing theme 2: cancer diagnosis

The second organizing theme was cancer diagnosis, which encompassed how patients were initially diagnosed. One participant preemptively screened because she was aware that her mother and sister had been diagnosed with breast cancer (family history).

My mother had breast cancer, she died of breast cancer in her 30s. And then my sister, 18 months before I was diagnosed, she had had breast cancer, and she got her diagnosis when she was like 25 […]. I had already done my BRCA testing, so I knew that I was BRCA positive. [11] (Female, 36 years, employed, married)

Another participant described how they had accidentally uncovered their cancer diagnosis while seeking treatment for another illness.

No, it was for a scan for something else in my neck, and when they were scanning my neck, they found the tumor also. [1] (Female, 32 years, employed, single)

Symptoms may be mild during the early stages of cancer. Participants in whom cancer was detected early stated they had a long recovery path but had better treatment options than patients diagnosed with the late stage.

Organizing theme 3: cancer treatment journey

The third organizational theme was the cancer treatment journey. Most participants described their diagnosis and treatment journey as long and stressful, negatively affecting their overall health. One participant described how she was financially impacted and how worried she was because she had to skip work for treatment.

Yes, there was a huge loss of income because I wasn’t salaried […] I didn’t get any funds the time I was off. I would probably say […], I missed 50% of the work because I was out, so it did have a huge, it did have an impact. But I was so sick, I’d be in the bed for six days. [11] (Female, 36 years, employed, married)

Several participants pointed out how their careers were jeopardized after their long treatment journey. Because of long gaps in employment, they felt that they could not return to what they had done previously. They also had no idea how to restart their careers. One participant expressed a desire for assistance in restarting their career. Participants suggested that a personal coach or a life coach resource could help them develop and deploy a plan to find the right job that best suited their situation and skill set.

But like have some kind of – not backup plan, but kind of have like a, a – career wise, a plan to return to work. Like, what’s the path to get back, as opposed to letting your work contract expire. Like, what’s the – what I do when I get better? How do I go back into employment? How can they help me figure that out? [7] (Female, 53 years, employed, single)

Some participants lost employer-sponsored benefits (eg, health insurance and health savings account) in the context of increasing cancer-related expenses. Critically, benefits were not standardized. For example, one participant did not have the option to utilize the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA).

So, because I hadn’t been at my job very long, I wasn’t FMLA protected, and technically, they probably could have let me go. But they did work with me. […] Any days that I was off, like when I was in the hospital with sepsis, or when I got the blood clot, I just didn’t get paid for those days. [7] (Female, 53 years, employed, single)

Younger participants experienced major negative career impact because they were just starting to build their careers. Unfortunately, they either had to take long breaks or quit their jobs to focus on their treatment. For example:

From my perspective, I didn’t feel I could apply for a new job knowing that I needed to be out […]. I mean, how can you be starting a new job and say, okay, once every three weeks, I’m going to be completely out for five days. […] I just chose to ride things out where I was. I would say the hardest part for me now is that I’m having these troubles with my, you know, these issues with my vision, because it’s affecting my driving, and it’s affecting my ability to use the computer a lot. [7] (Female, 53 years, employed, single)

Overall, 12 of the 15 participants who were employed at the time of their cancer diagnosis reported career disruption and loss of income (the other 4 were students, and 1 participant was transitioning from a full-time job to a full-time student at the time of their cancer diagnosis). This was a consistent theme across all employed participants who had experienced work impairments owing to their diagnoses and treatments. Students reported that their diagnosis had derailed their educational trajectory, eventually impacting their professional careers.

Organizing theme 4: expenses and financial implications

Most participants had some form of family support. Family members provided moral and financial support, which played vital roles during treatment as both minimized the financial burden and mental strain. One participant said:

I moved back home with my parents because I need help to survive […] I could not afford anything anymore because my money went to the prescriptions and, you know, travel. […] I basically lived at the cancer center probably 4-5 days a week, my electrolytes needed to be replaced all the time. So, I had to drive there every single day back and forth. When I couldn’t drive and my parents cannot take me, I had to take Ubers […] so it became, all of my money goes to my meds, travel, and bills. [2] (Female, 44 years, employed, separated)

Organizing theme 5: coping mechanism

The final organizing theme was coping mechanism, which relates to the presence or absence of direct social support from providers, friends, and families. Participants expected health-care providers to direct them toward resources for financial guidance. One participant said:

You know for finances, I think it would be helpful, you know at the time of diagnosis because you know, you hear the horror stories and I know it’s out there that you know, people can’t pay for it or insurance isn’t enough or however that happens but maybe somebody in the business office is sit down and be like, okay, this is your plan. This is you know, how much it’s going to cost here is your portion. [10] (Female, 44 years, employed, single)

Like this patient, most participants were provided only with information related to side effects of chemotherapy or radiation, whereas there was little to no information regarding financial assistance. Participants also wanted information that would benefit them in the long term.

I think with the long-term stuff for the treatments, [it] probably would have been good to know a little more about those. Just to have in the back of your mind – this could possibly happen, but we hope it doesn’t type of situation. […] just knowing what to do after everything is like, you know, your treatment’s done, everything’s good. So, what do I do after that? It’s kind of like, I don’t know what to do. [22] (Female, 55 years, employed, single)

Information on financial assistance or resources that could be accessed to deal with financial consequences would be beneficial. This is where participants would immensely benefit from a financial navigator. Many cancer centers are starting to implement this strategy. This role is similar to that of nurse navigators but focuses on optimizing insurance coverage and minimizing financial costs (20).

Every interview concluded with the question, Do you think financial burden is an important topic? All participants attested that this was an important topic.

I just appreciate you for doing this, and I’m sure you’ll get a lot of interesting comments and results and I think it’s good. Like I said, my financial burden wasn’t as much as some like my cousin went bankrupt. She had to declare bankruptcy. And so, I know you’ll hear a lot of that too. So yeah, when people that are well set off still have ramifications from that [13]. (Female, 51 years, employed, married)

Additionally, participants described that the train of expenses did not stop with the initial treatment. Ongoing expenses to maintain health have cascading effects on other nontreatment-related expenses.

In addition, participants who had the worst financial impact mentioned that they had no idea how to cope financially and mentally. There was little support from the Social Security Disability Insurance, which they used to pay for medications. They were able to work out a payment plan with the health system but eventually had to pay the debt. One participant pointed out their difficult financial path.

During this my husband told me he wanted to be separated during 3rd treatment, then I got even more afraid thinking if I would be able to afford for medication or not. Before my diagnosis I was literally on zero medication, right now you know I am on 15 pills twice a day it’s just hard.[2] (Female, 44 years, employed, separated)

The participants clearly described the intensity of their career disruptions, which often led to a complete halt in their earnings. In some cases, patients lost employer-sponsored benefits leading patients to defer treatments or become noncompliant with treatment.

Discussion

These results demonstrate that negative mental and physical health outcomes are common among participants experiencing high financial burden (16). Additionally, many participants pointed out that they faced career disruptions because of the delayed effects of treatment. Participants who worked for the same employer for a long period prior to diagnosis were given flexibility by their employers or allowed to file for long-term disability. Other participants who had to quit their jobs experienced large gaps in their career trajectories or were unable to rejoin the workforce.

Prior research suggests that 60% of workers across the United States are not entitled to any form of sick leave or time off. Combined with the results of this study, this suggests a possible opportunity to support public policies protecting workers who encounter cancer, as treatment journeys are long and difficult (21). In addition, many workers who have a higher probability of being exposed to carcinogens are more prone to a lack of FMLA and sick leave benefits (22).

Declining mental health and depression often accompany financial hardship and cancer. Previous research has demonstrated that family and group support may help cancer patients overcome depression-related issues (23). This finding was consistent among the participants. Depression and financial issues can accompany one another (24). Cancer is the number one disease causing patients to file for bankruptcy, which prompts health-care teams and patients to preemptively plan system-level factors and resources that would help reduce their financial burden (3).

Financial burdens can contribute to worsening health outcomes among patients with cancer, and some evidence explains why this continues. Issues include lack of open communication during treatment planning, cost of treatment, vague disclosure of financial assistance options, unclear insurance reimbursement procedures, and gaps in insurance coverage (25). Another issue is the lack of clarity regarding how insurance reimbursements work; some posttreatment therapies, such as genomics and yoga, are not covered (26-28).

Every health-care system should have a team of financial professionals trained in policies, such as the Affordable Care Act, Medicaid, and Medicare. Early intervention by professionals helps mitigate the effects of medical debt on a patient’s finances (29). Pretreatment discussions between cancer patients and financial professionals allow patients to explore their options such as payment plans or other financial assistance programs. There is no clear path for Medicare patients, as there are multiple insurance plans and few without high deductibles (27).

Patients must be open to communication and let their health-care team know what is right for them. This can minimize a lot of back and forth communication and ease the administrative and claim processes. This in turn allows health-care teams to explore other options with their financial teams. With the financial uncertainty that occurs postcancer diagnosis, patients should be able to rely on their care team to navigate difficult terrains. Previous studies have demonstrated that patients and physicians rarely express a desire to discuss costs (30-32).

Cancer centers and health-care systems are increasingly exploring the idea of utilizing financial counselors, financial navigators, and social workers more frequently to help patients navigate cancer treatment (33). Financial counselors and navigators can help explain insurance benefits, identify additional eligible benefits, and set up payment plans. Alternatively, social workers can assist patients in finding resources that may be directly or indirectly related to their financial resources. Some relevant areas include transportation, food, childcare, utility assistance, and prescription assistance, as 70% of patients with cancer often report reduced spending on necessities (34-36). Care providers can help with drug replacement plans by directly coordinating with pharmaceutical companies, which reduces costs by choosing a generic rather than a branded drug that is often expensive (37).

Low-income cancer patients who cannot afford sick leave during treatment are more susceptible to a greater financial burden. Additionally, gaps in employment and lack of guidance posttreatment can derail patients from job opportunities postcancer treatment. One longitudinal study demonstrated disparities in work status after treatment among breast cancer survivors (38-40). Factors such as job retention barriers, facilitators, and socioeconomic disparities overlaid with current policies affecting cancer and work may suggest possible approaches to improve work outcomes.

Patients with cancer should not be forced to sacrifice financial stability for treatment. Owing to the dynamic nature of FT, more detailed intervention-based research must be conducted to understand the causal effect of these new roles, such as financial and nurse navigators, to reduce the financial burden. Further research should investigate whether FT occurs more often in certain cancer types, owing to the scarcity of treatment options and shortage of doctors.

It is difficult to generalize the results across every domain because this was a single-region study. Additionally, narrower inclusion and exclusion criteria would strengthen our ability to draw inferences for certain populations or types of cancer diagnoses. It was a coincidence that most of the participants in this study were diagnosed with breast cancer. A future research direction could be a detailed qualitative study to discern the differences in patients’ experiences according to cancer type. For example, the experiences of women with breast cancer and those with lung cancer were evaluated. It is also coincidental that most participants were female.

This study provides valuable insights into the financial factors affecting patients with cancer and the coping mechanisms they adopt to overcome or minimize their financial burden. Even patients with adequate insurance still face steep, nontreatment-related expenses such as transportation costs, food, lodging, and wardrobe updates. Participants depleted their savings or used financial assistance to cope with unexpected treatment or nontreatment expenses. Family members and friends expressed sympathy and concern only during the initial period after postcancer diagnosis; participants were typically on their own thereafter. Every participant in the study suggested that cancer treatment was very expensive and that one could not pay all expenses. The complexity of medical bills and procedures is overwhelming. Participants and their families do not understand the coverage their insurance provides until they start receiving medical bills months later. Medical bills have terminology and line items that are not patient friendly. Participants pointed out that having contributed funds to their health savings accounts was beneficial for covering OOP costs.

Some forms of career disruption are common across cancer patients, and a continued lack of FT awareness could lead to a greater societal burden. Through their interviews, participants communicated how difficult it was to find information on applying for disability insurance. Policy makers and health workers must act quickly to control cancer drug pricing, which is continuing to skyrocket, and they must build educational material that is accessible at multiple outlets, helping cancer patients tackle FT and career disruption.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We extend our gratitude to the University of Kansas Cancer Center for its support during this study. We thank the PIVOT Patient Research Advocacy Program for recruiting study participants. Additionally, we would like to acknowledge Hope Krebill, Alexander Alsup, and Sam Pepper for their contribution, support, and review.

The funders had no role in the study’s design; the collection, analysis or interpretation of the data; or the writing of the manuscript or decision to submit it for publication.

Contributor Information

Dinesh Pal Mudaranthakam, Department of Biostatistics & Data Science, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS, USA; Department of Population Health, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS, USA; University of Kansas Comprehensive Cancer Center, Kansas City, KS, USA.

Dorothy Hughes, Department of Population Health, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS, USA.

Peggy Johnson, Patient and Investigator Voices Organizing Together (PIVOT), University of Kansas Comprehensive Cancer Center, Kansas City, KS, USA.

Tracy Mason, Patient and Investigator Voices Organizing Together (PIVOT), University of Kansas Comprehensive Cancer Center, Kansas City, KS, USA.

Nicole Nollen, Department of Population Health, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS, USA; University of Kansas Comprehensive Cancer Center, Kansas City, KS, USA.

Jo Wick, Department of Population Health, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS, USA; University of Kansas Comprehensive Cancer Center, Kansas City, KS, USA.

Danny R Welch, University of Kansas Comprehensive Cancer Center, Kansas City, KS, USA; Department of Cancer Biology, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS, USA.

Elizabeth Calhoun, Department of Population Health, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS, USA; Population Health Sciences, University of Illinois Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Data availability

Detailed data cannot be shared publicly to protect the privacy of individual participants. Information to support the findings of these analyses is available by contacting the corresponding author, who, upon reasonable request and understanding of the intended use of the data, will provide the requested information in a manner that continues to protect individual patient information.

Author contributions

Dinesh Pal Mudaranthakam, PhD (Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing), Dorothy Hughes, PhD (Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Methodology; Supervision; Writing—review & editing), Peggy Johnson, MS (Resources), Tracy Mason, BS (Resources; Writing—review & editing), Nicole Nollen, PhD (Data curation; Methodology; Writing—review & editing), Jo Wick, PhD (Conceptualization; Methodology; Writing—review & editing), Danny Welch, PhD (Methodology; Writing—review & editing), and Elizabeth Calhoun, PhD (Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Supervision; Writing—review & editing).

Funding

National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA168524 supported this study. It also used the Biostatistics and Informatics Shared Resource and Masonic Cancer Alliance (MCA).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

References

- 1. O’Connor JM, Kircher SM, de Souza JA. Financial toxicity in cancer care. J Commun Supp Oncol. 2016;14(3):101-106. doi: 10.12788/jcso.0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chhatwal J, Mathisen M, Kantarjian H. Are high drug prices for hematologic malignancies justified? A critical analysis. Cancer. 2015;121(19):3372-3379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, et al. Financial insolvency as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(9):980-986. doi: 10.1200/JClinOncol.2015.64.6620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ramsey S, Blough D, Kirchhoff A, et al. Washington State cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(6):1143-1152. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guy GP Jr, Ekwueme DU, Yabroff KR, et al. Economic burden of cancer survivorship among adults in the United States. J Clin Oncol 2013;31(30):3749-3757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Yabroff KR, et al. Are survivors who report cancer-related financial problems more likely to forgo or delay medical care? Cancer. 2013;119(20):3710-3717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hvidt EA. The existential cancer journey: travelling through the intersubjective structure of homeworld/alienworld. Health (London). 2017;21(4):375-391. doi: 10.1177/1363459315617312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nabors LB, Portnow J, Ahluwalia M, et al. Central Nervous System Cancers, Version 3.2020, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020;18(11):1537-1570. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.American Cancer Society. The Affordable Care Act: how it helps people with cancer and their families. https://www.cancer.org/treatment/finding-and-paying-for-treatment/health-insurance-laws/the-health-care-law.html. Accessed December 7, 2022.

- 10. Ellingson LL, Borofka KGE. Long-term cancer survivors’ everyday embodiment. Health Commun. 2020;35(2):180-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Knox JBL. Developing a novel approach to existential suffering in cancer survivorship through Socratic dialogue. Psychooncology. 2018;27(7):1865-1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Seiler A, Jenewein J. Resilience in cancer patients. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. CityofHope. Cancer Treatment Centers of America. https://www.cancercenter.com/integrative-care/immobility. Accessed April 21, 2022.

- 14. Ellingson LL. Realistically ever after. Manag Commun Q. 2017;31(2):321-327. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shih YT, Nasso SF, Zafar SY. Price transparency for whom? In search of out-of-pocket cost estimates to facilitate cost communication in cancer care. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36(3):259-261. doi: 10.1007/s40273-018-0613-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim H, Sefcik JS, Bradway C. Characteristics of qualitative descriptive studies: a systematic review. Res Nurs Health 2017;40(1):23-42. doi: 10.1002/nur.21768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Borrell-Carrió F, Suchman AL, Epstein RM. The biopsychosocial model 25 years later: principles, practice, and scientific inquiry. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(6):576-582. doi: 10.1370/afm.245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Attride-Stirling J. Thematic networks: an analytic tool for qualitative research. Qual Res. 2001;1(3):385-405. doi: 10.1177/146879410100100307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo Pro (Release 1.7.1). 2018. https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home. Accessed September 2022.

- 20. Sherman D. The emerging role of the financial navigator. Navectis Group. 2019. https://www.panfoundation.org/the-emerging-role-of-the-financial-navigator/. Accessed August 5, 2019.

- 21. Langa KM, Fendrick AM, Chernew ME, Kabeto MU, Paisley KL, Hayman JA. Out-of-pocket health-care expenditures among older Americans with cancer. Value Health. 2004;7(2):186-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Heidary F, Rahimi A, Gharebaghi R. Poverty as a risk factor in human cancers. Iran J Public Health. 2013;42(3):341-343. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Toledano-Toledano F, Luna D, Moral de la Rubia J, et al. Psychosocial factors predicting resilience in family caregivers of children with cancer: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(2):748. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18020748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mercadante S, Aielli F, Adile C, Bonanno G, Casuccio A. Financial distress and its impact on symptom expression in advanced cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(1):485-490. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05507-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Collado L, Brownell I. The crippling financial toxicity of cancer in the United States. Cancer Biol Ther. 2019;20(10):1301-1303. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2019.1632132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Collins SR, Robertson R, Garber T, Doty MM. Gaps in health insurance: why so many Americans experience breaks in coverage and how the Affordable Care Act will help: findings from the Commonwealth Fund Health Insurance Tracking Survey of U.S. Adults, 2011. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2012;9:1-22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yett DE, Der W, Ernst RL, Hay JW. Physician pricing and health insurance reimbursement. Health Care Financ Rev. 1983;5(2):69-80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shearer GE. Confusing inequitable Medicare prescription drug benefit. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(2):286-288. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0080-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Z, Wilson K, Hennings J, et al. The meaning of cancer: implications for family finances and consequent impact on lifestyle, activities, roles and relationships. Psychooncology. 2012;21(11):1167-1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bestvina CM, Zullig LL, Rushing C, et al. Patient-oncologist cost communication, financial distress, and medication adherence. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(3):162-167. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Alexander GC, Casalino LP, Meltzer DO. Patient-physician communication about out-of-pocket costs. JAMA. 2003;290(7):953-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schrag D, Hanger M. Medical oncologists’ views on communicating with patients about chemotherapy costs: a pilot survey. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(2):233-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Banegas MP, Dickerson JF, Friedman NL, et al. Evaluation of a novel financial navigator pilot to address patient concerns about medical care costs. Perm J. 2019;23(1):18-084. doi: 10.7812/TPP/18-084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. DiJulio B, Kirzinger A, Wu B, Brodie M. Data note: Americans’ challenges with health care costs. Menlo Park, CA: Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation; 2017. www.kff.org/health-costs/poll-finding/data-note-americans-challenges-with-health-care-costs. Accessed October 22, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zheng Z, Han X, Guy GP Jr, et al. Do cancer survivors change their prescription drug use for financial reasons? Findings from a nationally representative sample in the United States. Cancer. 2017;123(8):1453-1463. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Booske BC, Athens JK, Kindig DA, Park H, Remington PL. Different Perspectives for Assigning Weights to Determinants of Health. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin, Population Health Institute; 2010. www.countyhealthrankings.org/sites/default/files/differentPerspectivesForAssigningWeightsToDeterminantsOfHealth.pdf. Accessed October 23, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Siddiqui M, Rajkumar SV. The high cost of cancer drugs and what we can do about it. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(10):935-943. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. de Moor JS, Mollica M, Sampson A, et al. Delivery of financial navigation services within National Cancer Institute-designated cancer centers. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2021;5(3):pkab033. doi: 10.1093/jncics/pkab033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Norris L. Missouri and the ACA’s Medicaid Expansion, Health Insurance & Health Reform Authority. 2022. https://www.healthinsurance.org/medicaid/missouri/. Accessed March 27, 2023.

- 40. Blinder VS, Gany FM. Impact of cancer on employment. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(4):302-309. doi: 10.1200/JClinOncol.19.01856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Detailed data cannot be shared publicly to protect the privacy of individual participants. Information to support the findings of these analyses is available by contacting the corresponding author, who, upon reasonable request and understanding of the intended use of the data, will provide the requested information in a manner that continues to protect individual patient information.