Abstract

Background:

Patients with pulmonary diseases often experience fatigue. Severe fatigue is associated with a worse health status and worse physical and social functioning. The study aimed to evaluate the relationship between fatigue and quality of life in patients with nonmalignant pulmonary diseases.

Methods:

The St George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) was used to assess health status and the Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS) to measure the level of fatigue. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to test for normal distribution. Correlations were described as Spearman's rank correlation coefficient.

Results:

The study included 200 consecutive patients (mean age, 57.7) with the following diagnoses: COPD (26%), asthma (36%), obstructive sleep apnoea (19%), pneumonia or bronchitis of various aetiologies (8.5%), bronchiectasis (2.5%), interstitial lung disease (3%). The mean score in the SGRQ was 44.62 ± 24.94. The mean score in the MFIS was 28.64 ± 15.8. The strongest correlations appeared between quality-of-life scales and fatigue as measured by physical functioning (symptoms r = 0.622; activity r = 0.632; impact r = 0.692; p < 0.001 for all subscales); however, all the correlations between SGRQ and MFIS were significant.

Conclusions:

Patients with chronic pulmonary diseases were revealed to have a reduced level of quality of life and an increased level of fatigue. The negative influence of fatigue on quality of life highlights the need for careful and routine assessment of this symptom in pulmonary patients. Treating fatigue may improve quality of life and increase the ability of patients with chronic pulmonary diseases to perform activities in daily life.

Keywords: Fatigue, quality of life, chronic pulmonary diseases

Background

Fatigue often appears in the course of pulmonary diseases as a result of laboured breathing. Patients with obstructive airways diseases may experience fatigue of varying intensity and frequency depending on the underlying disease. In patients with asthma, fatigue appears as an episodic experience often associated with times of exacerbation, while in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), it is experienced daily. 1 Patients with COPD experience significantly greater fatigue than healthy subjects. In those patients, clinically significant fatigue is associated with worse health status, worse physical and social functioning as well as worse chronic respiratory symptoms.2,3 Shortness of breath also appears in patients with restrictive lung diseases despite it having different pathogenesis. 4 Up to 80% of patients with chronic sarcoidosis experience fatigue.5,6

The development of fatigue in patients with chronic pulmonary diseases is poorly understood, although the symptom itself has long been known. 7 Identifying possible underlying causes of fatigue and developing an understanding of the relation between fatigue and other symptoms may help to treat patients who experience fatigue. Fatigue contributes to a decrease in the ability to perform activities in daily life. The symptoms can be debilitating, troublesome, and unresponsive to treatment. It is also known that quality of life deteriorates as the severity of the disease increases – this includes increasing fatigue, among other issues. However, to date, the relation between fatigue and its impact on quality of life has not been sufficiently studied in patients with nonmalignant pulmonary diseases.

The study aimed to evaluate the relationship between fatigue and quality of life in patients with nonmalignant pulmonary diseases.

Methods

The inclusion criteria: chronic pulmonary disease (symptoms of obstructive or restrictive airways); first hospitalization or early stage of disease; age >18 years; patient's informed consent; understanding of all the questionnaire issues. The exclusion criteria: lack of nonmalignant pulmonary disease; age <18 years; long-term O2 treatment; long-term noninvasive mechanical ventilation; long-term corticosteroid treatment; no consent to participate; any disabilities interfering with the completion of the questionnaire.

The study was approved by the Commission of Bioethics at Wroclaw Medical University (No 32/2017). All the participants consented to take part in the study and to fill in questionnaires. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject.

The diagnostic survey method has been used. For the assessment of health status, the St George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) was used. 8 This questionnaire is a disease-specific tool designed to measure the impact of an obstructive airways disease on overall health, daily life, and perceived well-being. It consists of 50 items divided into two parts (three components). Every item is scored from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating more limitations. The American version of the questionnaire has good test-retest reproducibility (intraclass correlations between 0.795 and 0.900) and internal consistency (Cronbach's α below 0.70 for all components).9,10 The SGRQ has been validated for Polish conditions. In patients with bronchial asthma, the reliability was good, with Cronbach's alpha over 0.75 for the total score and all subscale scores. 11

The level of fatigue and its impact on quality of life was assessed with a modified form of the Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS), which was initially developed to evaluate how fatigue impacts the lives of patients with multiple sclerosis. It consists of 21 items grouped into 3 subscales: physical, cognitive, and psychosocial functioning. The total result of the MFIS may be scored from 0 to 84, with higher scores indicating greater fatigue. The MFIS has good internal consistency – Cronbach's alpha of 0.81 and reliability of below 0.87 for the total scale and its subscales.12,13 The MFIS scale has been validated for Polish conditions. 14

Data from questionnaires were collected on a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and statistically analysed using the R software v. 3.4.2. Data were presented as means and standard deviations from the mean as well as numbers and percentages. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to test for normal distribution. Correlations were described as Spearman's rank correlation coefficient as all variables had a distribution other than normal.

Results

200 consecutive patients (105 men and 95 women), suffering from symptoms of obstructive or restrictive airways, were enrolled in the study between January 2017 and October 2017. Out of 215 patients who met the eligibility criteria, 15 respondents had not filled in the questionnaires accurately, or withdrew from the research study without giving a reason.

The majority of patients were diagnosed with COPD – 52 (26%), asthma – 72 (36%), and obstructive sleep apnoea – 38 (19%); 17 (8.5%) patients were diagnosed with pneumonia (BOOP) or bronchitis of various aetiologies and courses. Another 5 (2.5%) had bronchiectasis, 6 (3%) interstitial lung disease, and 10 (5%) obstructive pulmonary symptoms in the course of treatment for cancer. All the patients were being treated in the Department of Pulmonology and Lung Cancer of Wroclaw Medical University, Poland.

In the study, questionnaires filled in by 200 patients were analysed. The mean age of the patients was 57.7 ± 16 years. The majority of them lived in the city (61.5%) and were professionally active (38.5%). Only 29.5% of respondents had high education degree. Two-thirds of the study group were smokers, i.e. active smokers (27.5%) or past smokers (38%). 40.5% of patients had no coexisting disease. The detailed characteristics of the study group are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The characteristics of the study group (n = 200).

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Median (quartiles) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 57.7 (16) | 60 (48–68) | ||

| Variable | n | % | ||

| Gender | Men | 105 | 52.50 | |

| Women | 95 | 47.50 | ||

| Place of living | In the city | 123 | 61.50 | |

| Rural area | 75 | 37.50 | ||

| Missing data | 2 | 1.00 | ||

| Education | Primary | 33 | 16.50 | |

| Vocational | 52 | 26.00 | ||

| Secondary | 56 | 28.00 | ||

| University | 59 | 29.50 | ||

| Professional activity | Employed | 77 | 38.50 | |

| Unemployed | 19 | 9.50 | ||

| Pensioner | 56 | 28.00 | ||

| Disability pensioner | 46 | 23.00 | ||

| Missing data | 2 | 1.00 | ||

| Smoking status | Smokers | 55 | 27.50 | |

| Non-smokers | 69 | 34.50 | ||

| Past smokers | 76 | 38.00 | ||

| Comorbidities | No comorbidities | 81 | 40.50 | |

| One coexisting disease | 88 | 44.00 | ||

| Two or more coexisting diseases | 29 | 14.50 | ||

| Pulmonary diseases | COPD | 52 | 26 | |

| Asthma | 72 | 36 | ||

| Obstructive sleep apnoea | 38 | 19 | ||

| Pneumonia or bronchitis (e.g. BOOP) | 17 | 8.5 | ||

| Bronchiectasis | 5 | 2.5 | ||

| Interstitial lung disease | 6 | 3 | ||

| Obstructive pulmonary symptoms | 10 | 5 | ||

The mean total score achieved in the SGRQ was below 50% of the maximal score; the mean score was 44.62 ± 24.94. Similarly, in the MFIS questionnaire, half of the respondents obtained scores of 27 or below out of a maximal score of 84. The greatest fatigue was observed in the area of physical functioning, while the lowest was in the area of cognitive functioning. The results of the SGRQ and MFIS questionnaires are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results of the St George's Respiratory Questionnaire and the Fatigue Impact Scale.

| Scale | N | Mean | SD | Median | Min | Max | Q1 | Q3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGRQ total score | 198 | 44.62 | 24.94 | 41.75 | 0 | 96.52 | 26.3 | 61.84 |

| Symptoms | 198 | 53.02 | 25.25 | 54.85 | 0 | 97.55 | 34.65 | 73.26 |

| Activity | 200 | 51.8 | 29.44 | 53.53 | 0 | 100 | 29.59 | 72.82 |

| Impact | 200 | 37.65 | 25.88 | 34.89 | 0 | 95.8 | 17.53 | 57.15 |

| MFIS total score | 200 | 28.64 | 15.8 | 27 | 0 | 67 | 17 | 39 |

| Physical functioning | 200 | 18.29 | 9.85 | 19 | 0 | 36 | 11 | 25.25 |

| Cognitive functioning | 200 | 7.09 | 6.51 | 5 | 0 | 30 | 2 | 11 |

| Psychosocial functioning | 197 | 3.02 | 2.21 | 3 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 5 |

SGRQ: St George's Respiratory Questionnaire; MFIS: Fatigue Impact Scale.

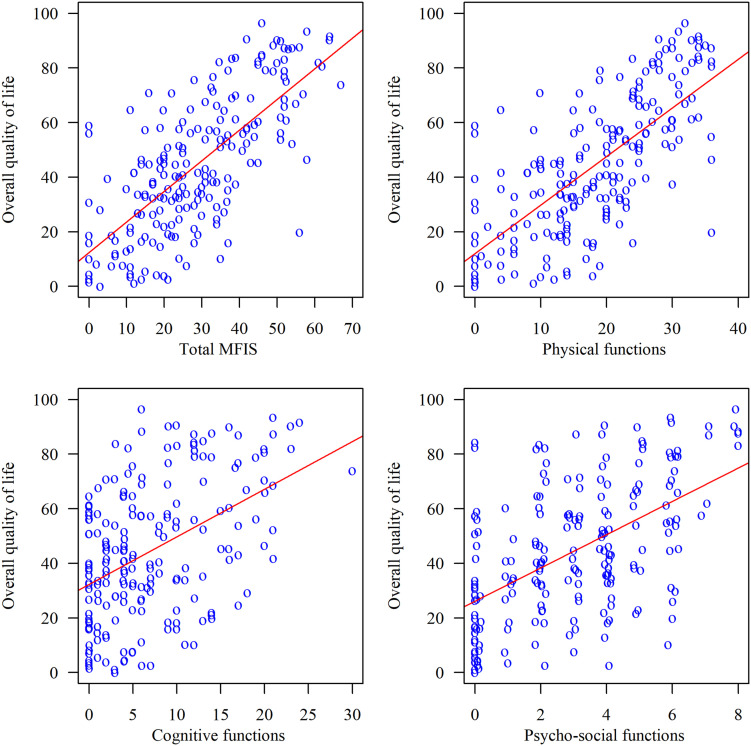

An analysis of the relationships between the total scores and the subscale scores in the SGRQ and the MFIS showed moderate and strong correlations. The strongest relationships emerged between quality-of-life scales and fatigue as measured by physical functioning. All correlations were significant. The results of the correlation analysis are shown in Table 3 and Figure 1.

Table 3.

Correlations between the St George's Respiratory Questionnaire and the Fatigue Impact Scale Scores.

| SGRQ total score | SGRQ symptoms | SGRQ activity | SGRQ impact | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | |

| MFIS total score | 0.698 | <0.001 | 0.593 | <0.001 | 0.628 | <0.001 | 0.687 | <0.001 |

| Physical functioning | 0.708 | <0.001 | 0.622 | <0.001 | 0.632 | <0.001 | 0.692 | <0.001 |

| Cognitive functioning | 0.419 | <0.001 | 0.355 | <0.001 | 0.378 | <0.001 | 0.408 | <0.001 |

| Psychosocial functioning | 0.518 | <0.001 | 0.418 | <0.001 | 0.469 | <0.001 | 0.522 | <0.001 |

SGRQ: St George's Respiratory Questionnaire; MFIS: Fatigue Impact Scale.

Figure 1.

The influence of fatigue (four subscales of MFIS) on QoL (SGRQ).

Discussion

Our study showed that patients with chronic pulmonary diseases have a reduced level of quality of life – they achieved 44.6 points out of 100 on average as measured by the SGRQ, and an increased level of fatigue – they achieved 28.6 points out of 84 on average as measured by the MFIS. A significant negative correlation between the severity of fatigue and the level of quality of life highlights the importance of fatigue management in order to maintain the ability to perform activities in daily life and a good quality of life among those patients. The indirect pharmacological treatment of fatigue comprises oxygen therapy, bronchodilator and steroid inhalers. Some lifestyle changes may help cope with fatigue, i.e. improving breathing techniques, eating a healthful diet, preventing dehydration, quitting smoking and sticking to good sleeping habits. Patients should be also consulted by suitable healthcare professionals (e.g. physiotherapists, psychologists, or respiratory nurses) who can help increase patients’ coping strategies. 15

The analysis of the concept of fatigue shows that the common understanding of fatigue is different from scientific definitions. Ream and Richardson developed a definition that helps to understand this feeling. According to them, fatigue is “a subjective, unpleasant symptom which incorporates total body feelings ranging from tiredness to exhaustion creating an unrelenting overall condition which interferes with individuals’ ability to function to their normal capacity.” 16 Many scales exist for the evaluation of fatigue in various populations of patients, but due to the fact that fatigue frequently coexists with many other pathological and physiological conditions, difficulties emerge in classifying and measuring this feeling. For this reason, there are also many questionnaires that measure fatigue; however, many of them are general and are often combined with measuring other aspects of selected diseases.17,18 The advantage of the MFIS questionnaire which we used in the present study is the fact that it has been validated among patients with COPD. 19

Fatigue is a common symptom among patients with chronic diseases. In the general population, the percentage of people who feel tired reaches 20%, 20 but it is much higher in patients with chronic pulmonary diseases, as it reaches up to 80% in patients with restrictive pulmonary diseases such as sarcoidosis5,6 and up to 50% in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases such as COPD.3,21,22 Despite this high prevalence, fatigue remains underreported due to the lack of specificity of this symptom, the lack of awareness among patients as well as the ambiguity of definitions and its multidimensional character. 16 There are many factors that contribute to an increase in fatigue in patients with chronic pulmonary disease. Laboured breathing leads to a reduction in physical activity and at the same time, the lack of physical activity increases the feeling of fatigue. As a result, patients who suffer from chronic pulmonary diseases intentionally limit their health-promoting physical activity and further increase the level of perceived fatigue. 20 Another factor is smoking. It is worth noting that in the present study, two-thirds of the patients were smoking at the time of the survey or had smoked in the past In COPD patients, the presence of fatigue correlates with depression and the annual exacerbation rate; it is more severe at times of exacerbation. 3 The experience of fatigue is also associated with insomnia. 23

In patients with chronic pulmonary diseases, the association between the presence of fatigue and quality of life remains insufficiently studied. 24 In COPD patients, quality of life is significantly reduced. Additionally, the level of quality of life correlates negatively with the severity of the disease as measured by symptoms, lung function, duration of the disease, and comorbidities.25,26 Chen et al. examined the impact of pain, fatigue and dyspnoea on quality of life in COPD patients undergoing pulmonary rehabilitation. The prevalence of fatigue among those patients was 77%. They found that the presence of fatigue and dyspnoea significantly contributed to a reduction in the level of quality of life. It is worth noting that the three symptoms they examined were mutually related. 27 Calik-Kutukcu et al. examined muscle strength, endurance, exercise capacity, and fatigue perception in relation to the level of quality of life in patients with COPD and healthy subjects. They found that fatigue and all other factors are affected in COPD patients, but not in controls. Additionally, fatigue affected activities in the daily life and the psychosocial life of patients with COPD. 28 Asthmatic patients also have a reduced quality of life, though to a lesser degree, but similar factors are important to maintain a good quality of life. 29 A cross-sectional study conducted by Peters et al. among 167 patients with severe asthma showed that fatigue was the most prevalent sub-domain of quality of life with severe impairment (90.4%). 30 In sarcoidosis patients, Michielsen et al. reported a lower level of all domains of quality of life in patients with fatigue compared to those without it. Additionally, fatigue was a significant negative predictive factor for a worse quality of life. 31 The present study supports the idea that the presence of fatigue contributes to lowering the level of quality of life. The value of this study lies in its being one among the few which discuss fatigue and its impact on quality of life in patients with chronic pulmonary diseases.

There is one limitation in this study that could be addressed in future research. The study group comprised heterogeneous disease entities. We considered them as one whole group of chronic pulmonary diseases. We did not aim to focus on the particular pulmonary diseases but to evaluate the relationship between fatigue and QoL. Future randomized and prospective studies on a more homogenous group of patients should allow for adequate evaluation of the relationship between fatigue and QoL in chronic pulmonary diseases.

Conclusions

Patients with chronic nonmalignant pulmonary diseases have a reduced level of quality of life and an increased level of fatigue. The negative influence of fatigue on quality of life highlights the need for careful and routine assessment of this symptom in pulmonary patients. Treating fatigue may improve quality of life and increase the ability to perform activities in daily life for patients with chronic pulmonary diseases. This study supports the idea that in patients with chronic pulmonary diseases, the assessment of fatigue should be included in routine clinical evaluation and should be taken into account in the planning of pulmonary rehabilitation programmes.

Footnotes

Consent for publication: Written informed consent in Polish was obtained from all the patients for the publication of this paper.

Authors’ contributions: ASC wrote and arranged the manuscript. JJ participated in the design of the study. WT participated in the design and coordination of the paper. FS participated in the design of the study. JK participated in the design and coordination of the paper. MC helped to draft the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of data and materials: The datasets generated and analysed during the current studies are not publicly available due to reasons of data security but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Uniwersytet Medyczny im. Piastów Slaskich we Wroclawiu (grant number SUB.E020.21.002).

Ethics approval and consent to participate: The study was approved by the Commission of Bioethics at Wroclaw Medical University (No 32/2017).

ORCID iD: Mariusz Chabowski https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9232-4525

References

- 1.Small S, Lamb M. Fatigue in chronic illness: the experience of individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and with asthma. J Adv Nurs 1999; 30: 469–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antoniu SA, Petrescu E, Stanescu R, et al. Impact of fatigue in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from an exploratory study. Ther Adv Respir Dis 2016; 10: 26–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baghai-Ravary R, Quint JK, Goldring JJ, et al. Determinants and impact of fatigue in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med 2009; 103: 216–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robinson HC. Respiratory conditions update: restrictive lung disease. FP Essent 2016; 448: 29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drent M, Lower EE, De VJ. Sarcoidosis-associated fatigue. Eur Respir J 2012; 40: 255–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Kleijn WP, De VJ, Lower EE, et al. Fatigue in sarcoidosis: a systematic review. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2009; 15: 499–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atkins C, Wilson AM. Managing fatigue in sarcoidosis – a systematic review of the evidence. Chron Respir Dis 2017; 14: 161–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM. The St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. Respir Med 1991; 85: 25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barr JT, Schumacher GE, Freeman S, et al. American translation, modification, and validation of the St George’s respiratory questionnaire. Clin Ther 2000; 22: 1121–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM, et al. A self-complete measure of health status for chronic airflow limitation. The St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. Am Rev Respir Dis 1992; 145: 1321–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuzniar T, Patkowski J, Liebhart J, et al. Validation of the Polish version of St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire in patients with bronchial asthma. Pneumonol Alergol Pol 1999; 67: 497–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fisk JD, Pontefract A, Ritvo PG, et al. The impact of fatigue on patients with multiple sclerosis. Can J Neurol Sci 1994; 21: 9–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisk JD, Ritvo PG, Ross L, et al. Measuring the functional impact of fatigue: initial validation of the fatigue impact scale. Clin Infect Dis 1994; 18: S79–S83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gruszczak A, Bartosik-Psujek H, Pocińska K, et al. Validation analysis of selected psychometric features of Polish version of modified fatigue impact scale-preliminary findings [In Polish]. Neurol Neurochir Pol 2009; 43: 148–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kouijzer M, Brusse-Keizer M, Bode C. COPD-related fatigue: impact on daily life and treatment opportunities from the patient’s perspective. Respir Med 2018; 141: 47–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ream E, Richardson A. Fatigue: a concept analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 1996; 33: 519–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aaronson LS, Teel CS, Cassmeyer V, et al. Defining and measuring fatigue. Image J Nurs Sch 1999; 31: 45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neuberger G. Measures of fatigue. Am Coll Rheumatol 2003; 49: S175–S183. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Theander K, Cliffordson C, Torstensson O, et al. Fatigue impact scale: its validation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Psychol Health Med 2007; 12: 470–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen MK. The epidemiology of self-perceived fatigue among adults. Prev Med 1986; 15: 74–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baltzan MA, Scott AS, Wolkove N, et al. Fatigue in COPD: prevalence and effect on outcomes in pulmonary rehabilitation. Chron Respir Dis 2011; 8: 119–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Theander K, Unosson M. Fatigue in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Adv Nurs 2004; 45: 172–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kentson M, Todt K, Skargren E, et al. Factors associated with experience of fatigue, and functional limitations due to fatigue in patients with stable COPD. Ther Adv Respir Dis 2016; 10: 410–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reardon JZ, Lareau SC, ZuWallack R. Functional status and quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med 2006; 119: 32–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwon HY, Kim E. Factors contributing to quality of life in COPD patients in South Korea. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2016; 11: 103–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmed MS, Neyaz A, Aslami AN. Health-related quality of life of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: results from a community based cross-sectional study in Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, India. Lung India 2016; 33: 148–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen YW, Camp PG, Coxson HO, et al. A comparison of pain, fatigue, dyspnea and their impact on quality of life in pulmonary rehabilitation participants with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD 2018; 15: 65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calik-Kutukcu E, Savci S, Saglam M, et al. A comparison of muscle strength and endurance, exercise capacity, fatigue perception and quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and healthy subjects: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pulm Med 2014; 14: 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sundh J, Wireklint P, Hasselgren M, et al. Health-related quality of life in asthma patients – a comparison of two cohorts from 2005 and 2015. Respir Med 2017; 132: 154–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peters JB, Rijssenbeek-Nouwens LH, Bron AO, et al. Health status measurement in patients with severe asthma. Respir Med 2014; 108: 278–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michielsen HJ, Drent M, Peros-Golubicic T, et al. Fatigue is associated with quality of life in sarcoidosis patients. Chest 2006; 130: 989–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]