Highlights

-

•

Site differences emerge in approach-related brain activity and cannabis use.

-

•

In Texas, more cannabis use was associated with higher approach-related activity.

-

•

In Amsterdam, more cannabis use was associated with lower approach-related activity.

Keywords: Cannabis use disorder, fMRI, Approach bias, Cross-cultural

Abstract

Introduction

As cannabis policies and attitudes become more permissive, it is crucial to examine how the legal and social environment influence neurocognitive mechanisms underlying cannabis use disorder (CUD). The current study aimed to assess whether cannabis approach bias, one of the mechanisms proposed to underlie CUD, differed between environments with distinct recreational cannabis policies (Amsterdam, The Netherlands (NL) and Dallas, Texas, United States of America (TX)) and whether individual differences in cannabis attitudes affect those differences.

Methods

Individuals with CUD (NL-CUD: 64; TX-CUD: 48) and closely matched non-using controls (NL-CON: 50; TX-CON: 36) completed a cannabis approach avoidance task (CAAT) in a 3T MRI. The cannabis culture questionnaire was used to measure cannabis attitudes from three perspectives: personal, family/friends, and state/country attitudes.

Results

Individuals with CUD demonstrated a significant behavioral cannabis-specific approach bias. Individuals with CUD exhibited higher cannabis approach bias-related activity in clusters including the paracingulate gyrus, anterior cingulate cortex, and frontal medial cortex compared to controls, which was no longer significant after controlling for gender. Site-related differences emerged in the association between cannabis use quantity and cannabis approach bias activity in the putamen, amygdala, hippocampus, and insula, with a positive association in the TX-CUD group and a negative association in the NL-CUD group. This was not explained by site differences in cannabis attitudes.

Conclusions

Pinpointing the underlying mechanisms of site-related differences—including, but not limited to, differences in method of administration, cannabis potency, or patterns of substance co-use—is a key challenge for future research.

1. Introduction

Cannabis policies within and across countries are now diverging, with medical and recreational cannabis use legalized and decriminalized in many countries (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Drug Market Trends of Cannabis and Opioids. World Drug Rep., Vienna: United Nations; 2022, 2022). The legal status and individuals’ attitudes towards cannabis may influence trajectories of cannabis use disorder [CUD; Askari et al., 2021, Wu et al., 2015, Prashad et al., 2017, Von Sydow et al., 2002, Philbin et al., 2019]. The current study aimed to assess whether cannabis approach bias, one of the mechanisms proposed to underlie CUD, differed between environments with distinct recreational cannabis policies (Amsterdam, The Netherlands (NL) and Dallas, Texas, United States of America (TX)) and whether individual differences in cannabis attitudes affect those differences.

Differences in cannabis policies between NL and TX provide a unique opportunity to investigate the role of cannabis culture in the mechanisms underlying CUD. Recreational cannabis use has been decriminalized in the Netherlands since 1976, while cannabis remains illegal in TX at both the state and federal level. Accumulating evidence from the US provides initial insight into how policy affects cannabis use and attitudes. As policies become more permissive, the prevalence of use increases (Bailey et al., 2020, Philbin et al., 2019). Furthermore, attitudes regarding harms and benefits appear to be a key mechanism underlying use patterns (Fleming et al., 2016, Holm et al., 2014, Martínez-Vispo and Dias, 2022, Turna et al., 2022). As legal barriers are removed, cannabis attitudes may exert a stronger influence on use behaviors, as evidenced by the stronger associations between perception of harm and use post-legalization (Fleming et al., 2016). Beyond individual attitudes, perceptions of community attitudes can be either a protective or risk factor for the development of CUD. Disapproval from family and friends has been associated with decreased odds of CUD (Wu et al., 2015), but perceived approval of the social environment has been associated with increased quantity and frequency of use (Elgendi, Bartel, Sherry, & Stewart, 2022). Taken together, more positive individual and community attitudes may play a critical role in the pathway to CUD and research on how attitudes interact with known neurocognitive mechanisms is warranted. Cannabis approach bias (tendency to approach rather than avoid cannabis-related cues) is proposed as one of the neurocognitive mechanisms underlying the development and maintenance of CUD. No studies have yet investigated whether explicit positive cannabis attitudes, affected by permissiveness of the environment, influences cannabis approach bias.

Approach bias is theorized to reflect the interaction of the heightened appetitive value and salience of substance-related cues (Robinson & Berridge, 2008) and diminished functioning of reflective control (Kroon et al., 2020, Tanabe et al., 2019) resulting in approach behavior in response to cues which may override explicit goals and desires to refrain from drug use. A systematic review identified eight studies assessing cannabis approach bias (Loijen, Vrijsen, Egger, Becker, & Rinck, 2020). While three studies did not find an approach bias in treatment-seekers (Cousijn et al., 2015, Jacobus et al., 2018, Sherman et al., 2018), five studies showed support for an association between approach bias and escalation of use in heavy and at-risk users (Cousijn et al., 2013, Cousijn et al., 2011, Field et al., 2006, Wolf et al., 2017). At the behavioral level, cannabis approach bias has also been shown to predict increased use but not problem severity after six-months (Cousijn, Goudriaan, & Wiers, 2011). Additionally, weaker approach bias activations in ‘reflective’ control related brain areas—namely the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC)—predicted increased problem severity after six months (Cousijn et al., 2012). Of note, two of the three studies that did not observe a cannabis approach bias were conducted in the US and three of the four studies that did were conducted in the NL, adding to the hypothesis that the cultural environment may affect the neurocognitive mechanisms underlying CUD.

In the current study, we examined differences in 1) the behavioral and neural correlates of cannabis approach bias and its association with cannabis use measures, and in 2) perceptions of personal and community cannabis attitudes between TX and the NL. Moreover, we examined 3) if differences in cannabis attitudes explained differences in behavioral and neural approach bias. We recruited daily or near-daily cannabis users who met the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for CUD and closely matched controls at both sites. We hypothesized that individuals in the more permissive legal environment (NL) would demonstrate stronger behavioral approach biases and weaker approach bias activations in the control-related brain regions compared to controls and the TX CUD group. Furthermore, we hypothesized that NL users would report more positive cannabis attitudes in the CUD group compared to controls and the TX CUD group. Finally, we expected that more positive cannabis attitudes would moderate the site differences in cannabis approach bias measures, such that more positive attitudes would be associated with stronger approach behavior and approach-related activations.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants and procedure

A total of 131 (NL:76; TX: 54) cannabis users with a CUD and 93 (NL: 54; TX: 39) controls were recruited via social media and flyers. Participants were aged 18–30, right handed, and had no MRI contra-indications, history of or current diagnosis of major Axis-1 disorders except anxiety and depression, known neurological disorders, brain damage, chronic medical issues, or a history of regular (i.e. monthly) use of illicit drugs. Participants were excluded at screening if they reported a score above 12 on the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test [AUDIT; Saunders, Aasland, Babor, De La Fruente, & Grant, 1993], but retained in the sample if they scored higher during the session (N = 12). Participants in the CUD group had to meet at least two DSM-5 CUD symptoms, use cannabis at least six days per week in the previous year and not have active plans to quit or seek treatment. Participants in the control group used cannabis ≤ 50 times in their life, not in the previous three months, and ≤ 5 times in the previous year. During the session, participants were screened for recent drug use with a rapid urine screen. Individuals who tested positive for a drug except for cannabis and individuals in the control group who tested positive for cannabis were excluded from analysis. Participants missing MRI data or behavioral data and those who moved more than 4.5 mm during the fMRI task were excluded from analysis.

The ethics committee of the University of Amsterdam Faculty of Social and Behavioral Sciences (2018-DP-9616) and the University of Texas Dallas Institutional Review Board (19–107) approved the procedures. All participants provided voluntary informed consent and were compensated financially for their time. Before scanning, participants completed all questionnaires and tasks unrelated to substance use, a urine drug screen, and a practice version of the approach avoidance task. After scanning, participants completed all substance related questionnaires and interviews.

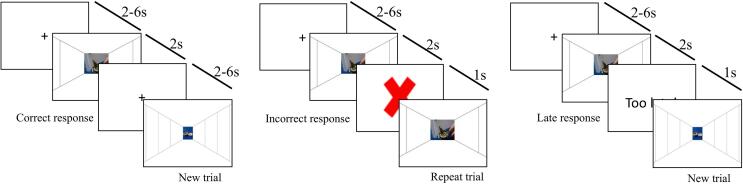

2.2. Cannabis approach avoidance task

Participants were instructed to approach or avoid cannabis and neutral stimuli matched on shape and brightness based on image orientation (portrait or landscape) resulting in four conditions: cannabis approach (CAp), cannabis avoid (CAv), neutral approach (NAp), and neutral avoid (NAv). The CAAT design was based on our previous work (Cousijn et al., 2011, Cousijn et al., 2012). A fixation cross (2–6 s jitter) was presented between each stimulus (2 s). Participants could approach or avoid by continuously pressing a corresponding button with either their right pointer or middle fingers depending on response type that would result in a zooming in or zooming out effect respectively to imitate stimulus approach and avoidance. A response was correct when the image was approached or avoided correctly based on the image orientation. Following an incorrect response, a red ‘X’ was shown for one second and the trial was repeated. Following a late response, ‘Too Late!’ was shown for one second but the trial was not repeated (Fig. 1). A total of 20 cannabis and 20 neutral stimuli were presented four times each, twice in approach trials and twice in avoid trials, resulting in 160 trials. The task used an event-related design. The sequence of stimuli, conditions, and the timing of the fixation events between trials was optimized and determined using the Optseq2 tool (https://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/optseq/). The three sequences with the best optimizations were chosen. Landscape or portrait images was counterbalanced for each sequence, resulting in six versions of the task counterbalanced across participants.

Fig. 1.

Schematic overview of the cannabis approach avoidance task (CAAT) trial outcomes: correct response (left), incorrect response (middle) and late response (right).

2.3. Questionnaire assessments

2.3.1. Cannabis measures

The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview [MINI; Sheehan et al., 1998] was administered to assess CUD symptoms. A substance use history questionnaire assessed average days of use per week, average grams per use day, and age at first use. The Cannabis Culture Questionnaire [CCQ; Holm, Tolstrup, Thylstrup, & Hesse, 2016] consists two subscale that measure beliefs about the benefits (positive) and harms (negative) of cannabis respectively. Expanding upon the original questionnaire, participants completed each item from three perspectives: their own beliefs, their perception of their family and friends’ beliefs, and their perception of the majority belief in their societal context (TX or NL; supplementary materials). Positive and negative effect sum scores were calculatedly separately for each perspective resulting in six measures.

2.3.2. Substance use, well-being, and other measures

Participants reported on alcohol use and related problems (AUDIT (Saunders et al., 1993), daily number of cigarettes, and lifetime use of other substances. The Beck Depression Inventory [BDI-II; Beck, Steer, Ball, & Ranieri, 1996], the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory [STAI; Spielberger, 2010], Adult ADHD Self-Report Screening Scale (ASRS; (Ustun et al., 2017), and the DSM5 self-rated level 1 cross-cutting symptom checklist [DSM5-CCSM; American Psychiatric Association, 2013]; excluding the substance abuse items), were administered to assess current symptoms of depression, anxiety, ADHD, and cross-cutting symptoms of mental illness. The Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale [WAIS-IV; Wechsler, 2012, Coalson et al., 2010] matrix reasoning and vocabulary tasks were administered to estimate IQ.

2.4. Neuroimaging data collection and preprocessing

Anatomical and functional MRI scans were collected using a 3 T Philips Achieva MRI Scanner with a 32-channel SENSE head coil at the University of Amsterdam and a 3 T Siemens MAGNETOM Prisma MRI Scanner with a 64-channel head coil at the University of Texas Dallas. To register the functional scans to anatomical space, an anatomical (T1) scan was conducted (TR/TE = 8.3/3.9 ms, FOV = 188 × 240 × 220 mm3, 1 × 1 × 1 mm3, flip angle = 8°). Functional scans were acquired with a T2* single-shot multiband accelerated EPI sequence during the CAAT task (multiband factor = 4, TR/TE = 550/30 ms, FOV = 240 × 240 × 118.5, voxel size = 3 × 3 × 3 mm3, interslice gap = 0.3 mm, flip angle = 55°). Preprocessing was conducted using fMRIprep as implemented in Harmonized AnaLysis of Functional MRI pipeline (HALFpipe version 1.2.2 (Waller et al., 2022), which included skull-stripping, spatial smoothing, and motion correction of the functional images and registration to the anatomical images [supplementary materials; Esteban et al., 2019].

2.5. Data analysis

2.5.1. Behavioral data

ANOVAs were performed to assess group (CAN, CON) and site (TX, NL) differences, and group by site interactions for all descriptive outcomes. Outcomes with group or site differences were added to subsequent analyses as a sensitivity check.

Linear mixed effects models were estimated (maximum likelihood estimation, allowing for random intercepts and random slopes for participant and perspective), using the lme4 package (Bates, Mächler, Bolker, & Walker, 2015) in R version 3.6.3 (R Core Team, 2022) to assess group and site differences in CCQ scores. All possible models including at least group, site, and perspective were estimated and the model with the best fit based on AIC metrics was interpreted.

For the CAAT, group and site differences in approach/avoidance accuracy were examined using ANOVA. To assess cannabis approach bias, incorrect responses and trials with reaction times (RT) < 200 ms were removed, and RTs were log-transformed. Linear mixed effects models were estimated (maximum likelihood estimation, allowing for random intercepts and random slopes for movement and stimulus type) to assess the effect of site, group, movement type (approach, avoid), stimulus type (cannabis, neutral), their four-way interaction, and all lower-level interactions on RT. Cannabis attitudes, grams per week, CUD symptom count, CCQ (sum score for each subscale) were added to the model separately as an interaction term with movement and stimulus type to assess their effect of cannabis approach bias in the cannabis group only. Site was then added to this interaction term to examine whether the associations differed between NL and TX.

2.5.2. fMRI data

Subject-level models were computed with FSL FEAT [version 6.0; (Woolrich et al., 2009)]. Using a general linear model, predictors for each condition (CAp, CAv, NAp, NAv) were convolved with a double-gamma hemodynamic response function. The contrast of interest [(CAp > CAv) - (NAp > NAv)] isolated activity on cannabis approach trials (versus cannabis avoid trials) corrected for neutral approach trials (versus neutral avoid trials).

Whole-brain voxel-wise analyses were conducted with FSL’s FEAT FLAME 1 mixed effects models with cluster-wise multiple comparison correction (Z > 2.3, cluster p-significance threshold = 0.05). A two-group difference model was run to assess group differences in brain activity, adding site as a covariate to model scanner differences. To examine whether the group differences were dependent on site, a two-way between-subjects ANOVA was conducted. Regression models including CUD symptom count and grams of use per week as regressors (controlling for mean site activity), were run to assess their association with cannabis approach bias-related activity in the CUD group as well as whether differences emerged across sites in the associations.

For all analyses, individual mean peak activity was extracted from significant clusters to visualize effects and perform follow-up analyses. Task accuracy and approach bias score—computed as (CAv – CAp) – (NAv – NAp) using individual median RT for each condition—were regressed on mean peak activity to assess whether task performance was related to brain activity, and whether associations differed across sites. When significant clusters of activity emerged when comparing sites, follow-up regressions were computed with mean peak activity as the dependent variable and CCQ scores as the predictors, with and without site as a moderator. When significant effects were observed, sensitivity analyses were conducting controlling for sample characteristic differences between groups.

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics

Twenty-five participants were excluded from the analysis (Table 1), resulting in a sample of 64 NL cannabis users (NL-CUD), 48 TX cannabis users (TX-CUD), 50 NL controls (NL-CON), and 36 TX controls (TX-CON). Cannabis users were matched across sites on CUD symptom count, days of cannabis use per week, depression and anxiety symptoms, years of education, other illicit substance use, alcohol use and related problems, and overall mental health symptoms (DSM5-CCSM; Table 2). The NL-CUD group was significantly younger, had lower estimated IQ, reported typically using less grams per week, had more daily cigarette smokers, and reported more ADHD-related symptoms than the TX-CUD group. Controls were well-matched on age, anxiety and depression symptoms, and overall mental health symptoms across sites. The NL-CON group was younger, had lower estimated IQ, had more years of education, more lifetime illicit substance use, more daily cigarette smokers, more alcohol use and related problems, and reported more ADHD-related symptoms than the TX-CON group.

Table 1.

Detailed reasons for exclusion.

| Reasons | TX | NL | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural brain abnormality | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Exceeds 4.5 mm motion threshold | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| MRI data quality issue | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| CAAT performance below 60 % accuracy | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Positive drug screen | 0 | 7 | 7 |

| CUD: too little cannabis use | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Total exclusions | 25 | ||

| Initial sample | 223 | ||

| Final sample | 198 |

Table 2.

Sample Characteristics.

|

Cannabis Users |

Controls |

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Overall |

NL |

TX |

Overall |

NL |

TX |

|||||||||||||||

| Median | MAD | Range | Median | MAD | Range | Median | MAD | Range | Median | MAD | Range | Median | MAD | Range | Median | MAD | Range | Results | Pairwise Comparisons | |

| N = 112; 42 % female | N = 64; 33 % female | N = 48; 54 % female | N = 90; 55 % female | N = 50, 54 % female | N = 36; 58 % female | Group | ||||||||||||||

| Age | 22 | 3 | 18–30 | 21 | 2 | 18–30 | 24 | 2 | 18–30 | 22 | 2 | 18–30 | 22 | 2 | 18–30 | 23 | 19–30 | Site*Group | 5* | |

| IQ | 22 | 3 | 7–30 | 21 | 3 | 7–30 | 23 | 2 | 16–30 | 25 | 3 | 12–35 | 23 | 3 | 12–30 | 26 | 2 | 17–35 | Site | |

| Education years | 14.5 | 1.5 | 5–20 | 15 | 2 | 7–20 | 14.25 | 2 | 5–20 | 16 | 1 | 10–23 | 17 | 1 | 12–23 | 16 | 2 | 10–21 | Group, Site | |

| Cannabis use measures | ||||||||||||||||||||

| CUD symptom count | 6 | 1 | 2–10 | 5 | 1.5 | 2–10 | 6 | 1 | 2–10 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Days of use (per week) | 7 | 0 | 5–7 | 7 | 0 | 5–7 | 7 | 0 | 5–7 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Typical grams/week | 7 | 3.5 | 0.275–35 | 5.6 | 2.6 | 0.275–21 | 8.4 | 2.25 | 0.7–35 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Site | |

| Age at first use | 16 | 1 | 11–27 | 15 | 1 | 11–18 | 16 | 2 | 12–27 | 17 | 2 | 13–21 | 17 | 1 | 14–21 | 19 | 0 | 13–20 | Group, Site | |

| Other substance use measures | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Lifetime illicit substance use (episodes) | 13 | 12 | 0–287 | 13 | 11.5 | 0–175 | 15 | 11 | 0–287 | 0 | 0 | 0–85 | 0 | 0 | 0–85 | 0 | 0 | 0–4 | Site*Group | 1*,3*,4* |

| Alcohol use and related problems (AUDIT) | 6 | 2 | 1–15 | 6 | 2 | 1–14 | 6 | 2.5 | 2–15 | 5 | 2 | 1–19 | 7 | 3 | 1–19 | 4 | 1 | 2–11 | Site*Group | 2*,3* |

| Daily smokers (%, N) | 32 % (36) | 51.6 % (33) | 6 % (3) | 16.7 % (15) | 28 % (14) | 2.8 % (1) | Site, Group | |||||||||||||

| Well-being measures | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Depression (BDI) | 9 | 6 | 0–39 | 8.5 | 5.5 | 0–34 | 10 | 6.5 | 0–39 | 5 | 4 | 0–31 | 6 | 3 | 0–23 | 5 | 4 | 0–31 | Group | |

| Anxiety (STAI-Trait) | 39.5 | 8.5 | 20–64 | 38 | 7 | 20–63 | 41 | 9 | 21–64 | 33 | 6 | 22–65 | 32 | 5 | 22–55 | 35.5 | 6.5 | 22–65 | Group | |

| ADHD (ASRS) | 14 | 3 | 3–22 | 16 | 2 | 10–22 | 10.5 | 2.5 | 3–21 | 13 | 3 | 3–23 | 15 | 2 | 10–23 | 9 | 3 | 3–18 | Group, Site | |

| DSM 5 Cross Cutting Symptoms (count) | 14 | 6 | 1–45 | 13.5 | 6 | 1–37 | 14.5 | 6.5 | 3–45 | 9 | 3 | 0–34 | 9.5 | 3.5 | 1–21 | 8 | 3 | 0–34 | Site*Group | 1*,3*,4* |

| Cannabis Attitudes | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Positive Personal | 26 | 2 | 6–30 | 24 | 3 | 6–30 | 27 | 27 | 22–30 | 18 | 3 | 10–28 | 17 | 2 | 10–28 | 18.5 | 3.5 | 10–25 | Group*Perspective; Site*Perspective | |

| Positive Family/Friends | 20 | 3 | 7–30 | 19.5 | 2.5 | 7–29 | 23 | 23 | 12–30 | 17 | 3 | 6–26 | 17 | 2 | 10–24 | 18 | 4.5 | 6–26 | ||

| Positive State/Country | 17 | 3 | 7–27 | 16.5 | 2.5 | 9–26 | 18 | 18 | 7–27 | 16 | 2 | 7–25 | 16 | 2 | 11–25 | 15 | 3 | 7–24 | ||

| Negative Personal | 15 | 3 | 6–25 | 16 | 3 | 7–25 | 12 | 12 | 6–20 | 19 | 4 | 8–28 | 20 | 3 | 8–27 | 18 | 3 | 9–28 | Site*Group Group*Perspective | 1** |

| Negative Family/Friends | 18 | 3 | 8–30 | 19 | 3 | 11–30 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 8–24 | 20.5 | 3 | 11–30 | 21 | 3 | 11–29 | 19.5 | 4.5 | 13–30 | ||

| Negative State/Country | 23 | 3 | 11–30 | 24 | 2 | 11–30 | 22 | 22 | 11–30 | 23 | 3 | 13–30 | 22 | 3 | 13–30 | 24 | 3 | 16–30 | ||

Note. CUD = Cannabis Use Disorder; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test; ADHD = Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; STAI = State Trait Anxiety Inventory; ASRS = Adult Self-Report Scale; 1: TX CAN-NL CAN, 2: TX CON-NL CON, 3: TX CAN-TX CON, 4: NL CAN-NL CON, 5: TX CAN-NL CON, 6: NL CAN-TX CON; *Significance threshold p =.05; **Significance threshold P =.05/28.

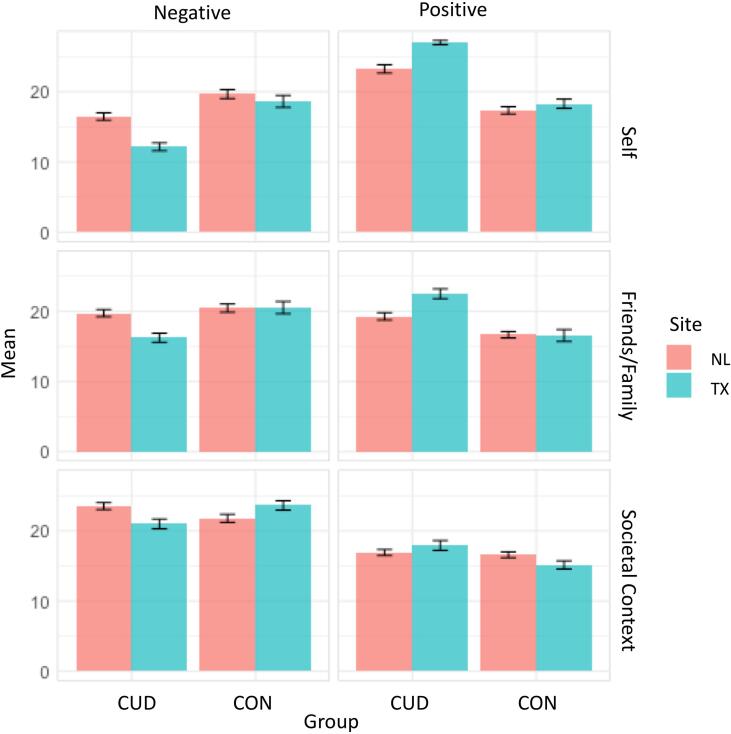

3.2. Cannabis attitudes

Significant group by perspective interactions emerged for negative and positive cannabis attitudes (Fig. 2; Table 3). Regardless of site, the CUD group reported more positive and less negative personal and family-friends attitudes. No group differences in state-country attitudes were observed.

Fig. 2.

Linear mixed effects models revealed significant Group*Perspective, Group*Site, and Site*Perspective two-way interactions in cannabis attitudes. Group*Perspective: For personal and family and friend perspectives, the CUD group overall reported less negative and more positive attitudes than the CON group. Group*Site: For negative attitudes only, the TX-CUD group reported less negative attitudes than the NL-CUD group for all perspectives. Site*Perspective: For positive attitudes only, the TX site overall reported more positive personal and family and friend attitudes than the NL site. Error bars based on standard error. Attitudes measured with adapted Cannabis Culture Questionnaire.

Group by site interactions were only observed for negative attitudes. Personal, family-friends, and state-country negative attitudes did not differ between TX and NL controls, but the TX-CUD group reported less negative attitudes for all perspectives compared to the NL-CUD group. A site by perspective interaction emerged for positive cannabis attitudes, with the TX group reporting more positive personal and family-friends attitudes than the NL group.

3.3. CAAT performance

3.3.1. Accuracy

Significant between-subjects main effects of site and group emerged in accuracy in the task overall. The NL participants had significantly more accurate first responses than the TX participants (92.4 % vs. 89.4 %; F(1,194) = 7.53, p =.007). Regardless of site, the CUD group was significantly less accurate than the controls (89.8 % vs. 92.9 %; F(1,194) = 11.421, p <.001).

A significant within-subject group by stimulus by movement type was observed (F(1, 194) = 10.2, p =.002). Post hoc Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons revealed that the CUD group was significantly less accurate on the cannabis avoid trials compared to all other conditions both within the CUD group and compared to the control group (Table 4). The CUD group was also less accurate during neutral approach trials compared to the control group.

Table 4.

Post-hoc pairwise comparisons for interaction between group, stimulus type, and movement type on accuracy in the CAAT.

| Reference | Comparison | Mean Difference | SE | t | p bonf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CUD, Neutral, Approach | CON, Neutral, Approach | −0.04 | 0.01 | −3.33 | 0.027 |

| CUD, Cannabis, Approach | −0.01 | 0.01 | −1.76 | 1 | |

| CON, Cannabis, Approach | −0.03 | 0.01 | −2.75 | 0.175 | |

| CUD, Neutral, Avoid | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.65 | 1 | |

| CON, Neutral, Avoid | −0.02 | 0.01 | −1.44 | 1 | |

| CUD, Cannabis, Avoid | 0.03 | 0.01 | 4.11 | 0.001 | |

| CON, Cannabis, Avoid | −0.02 | 0.01 | −1.73 | 1 | |

| CON, Neutral, Approach | CUD, Cannabis, Approach | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.42 | 0.449 |

| CON, Cannabis, Approach | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.98 | 1 | |

| CUD, Neutral, Avoid | 0.05 | 0.01 | 3.75 | 0.006 | |

| CON, Neutral, Avoid | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.54 | 0.32 | |

| CUD, Cannabis, Avoid | 0.07 | 0.01 | 5.83 | < 0.001 | |

| CON, Cannabis, Avoid | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.30 | 0.625 | |

| CUD, Cannabis, Approach | CON, Cannabis, Approach | −0.02 | 0.01 | −1.84 | 1 |

| CUD, Neutral, Avoid | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.19 | 0.829 | |

| CON, Neutral, Avoid | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.53 | 1 | |

| CUD, Cannabis, Avoid | 0.04 | 0.01 | 5.27 | < 0.001 | |

| CON, Cannabis, Avoid | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.82 | 1 | |

| CON, Cannabis, Approach | CUD, Neutral, Avoid | 0.04 | 0.01 | 3.17 | 0.046 |

| CON, Neutral, Avoid | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.88 | 1 | |

| CUD, Cannabis, Avoid | 0.06 | 0.01 | 5.25 | < 0.001 | |

| CON, Cannabis, Avoid | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.38 | 1 | |

| CUD, Neutral, Avoid | CON, Neutral, Avoid | −0.02 | 0.01 | −1.86 | 1 |

| CUD, Cannabis, Avoid | 0.03 | 0.01 | 4.03 | 0.002 | |

| CON, Cannabis, Avoid | −0.03 | 0.01 | −2.15 | 0.903 | |

| CON, Neutral, Avoid | CUD, Cannabis, Avoid | 0.05 | 0.01 | 3.95 | 0.003 |

| CON, Cannabis, Avoid | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.48 | 1 | |

| CUD, Cannabis, Avoid | CON, Cannabis, Avoid | −0.05 | 0.01 | −4.23 | < 0.001 |

Note. CUD = Group with cannabis use disorder; CON = non-using controls. P-value Bonferroni-corrected for 28 comparisons.

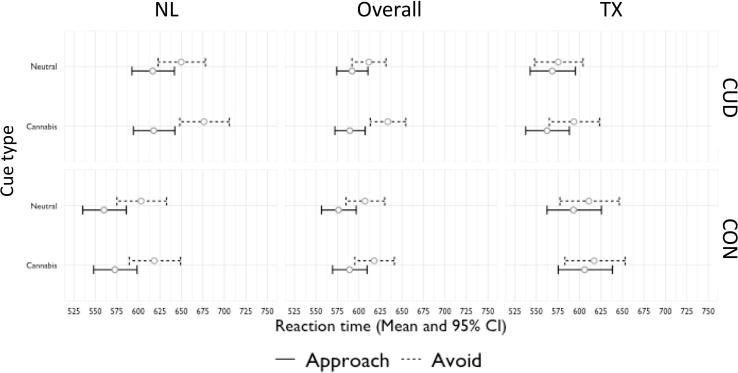

3.3.2. Reaction time

Three significant interactions emerged in the model: group by movement by stimulus, site by movement, and site by group. The three-way interaction revealed a cannabis approach bias in the CUD group only (Fig. 3; Table 5). Regardless of site, the CUD group was faster to approach than avoid the cannabis cues, while no difference in RT emerged between approaching and avoiding neutral cues. The results hold when controlling for age, gender, years of education, alcohol use and related problems, overall task accuracy, and lifetime illicit substance use.

Fig. 3.

A linear mixed effects model revealed a significant three-way interaction of Group*Movement*Stimulus and significant two-way Site*Movement and Group*Site interactions. Group*Movement*Stimulus (Overall panel): The CUD group but not the CON group was significantly slower to avoid compared to approach the cannabis stimuli but no the neutral stimuli. Site*movement: TX site was faster to respond on avoid trials than the NL site. Group*Site: The TX-CUD group was faster to respond across all trials compared to the NL-CUD group. The NL-CUD group was slower than the NL-CON group, while the TX-CUD and TX-CON groups did not significantly differ. Error bar based on standard error.

Table 5.

Linear mixed effects model for the effect of group, site, stimulus type, and movement type on reaction times in the CAAT task.

| Model |

Model coefficients |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Fixed effects |

Random effects | ||||||

| B | 95 % CI (B) | SE (B) | t | p | SD | ||

| Intercept | 6.43 | 6.39: 6.47 | 0.02 | 322.67 | < 0.001 | 0.15369 | |

| Site: NL-TX | −0.09 | −0.15: −0.03 | 0.03 | −3.10 | 0.002 | ||

| Group: CAN-CON | −0.08 | −0.13: −0.02 | 0.03 | −2.53 | 0.012 | ||

| Movement: Approach-Avoid | 0.09 | 0.07: 0.11 | 0.01 | 8.17 | <0.001 | 0.06516 | |

| Stimulus: Cannabis - Neutral | 0.00 | −0.02: 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.23 | 0.816 | 0.0198 | |

| Site * Group | 0.15 | 0.06: 0.24 | 0.05 | 3.27 | 0.001 | ||

| Site * Movement | −0.04 | −0.07: 0 | 0.02 | −2.15 | 0.033 | ||

| Site * Stimulus | 0.01 | −0.01: 0.04 | 0.01 | 1.04 | 0.301 | ||

| Group * Movement | −0.01 | −0.05: 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.81 | 0.421 | ||

| Group * Stimulus | −0.02 | −0.04: 0 | 0.01 | −1.74 | 0.084 | ||

| Movement * Stimulus | −0.04 | −0.06: −0.02 | 0.01 | −3.45 | 0.001 | 0.02676 | |

| Site * Group * Movement | −0.02 | −0.07: 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.87 | 0.384 | ||

| Site * Group * Stimulus | −0.01 | −0.05: 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.66 | 0.513 | ||

| Site * Movement * Stimulus | 0.00 | −0.04: 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.21 | 0.832 | ||

| Group * Movement * Stimulus | 0.04 | 0.002: 0.07 | 0.02 | 2.13 | 0.034 | ||

| Site * Group * Movement * Stimulus | 0.02 | −0.03: 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.69 | 0.489 | ||

| Sensitivity Analysis | |||||||

| Intercept | 6.45 | 6.08: 6.82 | 0.19 | 33.95 | <0.001 | 0.15 | |

| Site: NL-TX | −0.11 | −0.19: −0.03 | 0.04 | −2.74 | 0.007 | ||

| Group: CAN-CON | −0.08 | −0.14: −0.01 | 0.03 | −2.38 | 0.02 | ||

| Movement: Approach-Avoid | 0.09 | 0.07: 0.11 | 0.01 | 8.01 | <0.001 | 0.07 | |

| Stimulus: Cannabis - Neutral | 0.00 | −0.02: 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.19 | 0.85 | 0.02 | |

| Site * Group | 0.12 | 0: 0.24 | 0.06 | 1.91 | 0.06 | ||

| Site * Movement | −0.04 | −0.08: 0 | 0.02 | −2.06 | 0.04 | ||

| Site * Stimulus | 0.02 | −0.01: 0.05 | 0.01 | 1.24 | 0.22 | ||

| Group * Movement | −0.02 | −0.05: 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.99 | 0.32 | ||

| Group * Stimulus | −0.02 | −0.04: 0 | 0.01 | −1.67 | 0.10 | ||

| Movement * Stimulus | −0.04 | −0.06: −0.02 | 0.01 | −3.36 | 0.001 | 0.03 | |

| Site * Group * Movement | −0.02 | −0.09: 0.05 | 0.03 | −0.58 | 0.56 | ||

| Site * Group * Stimulus | −0.04 | −0.09: 0.01 | 0.02 | −1.73 | 0.09 | ||

| Site * Movement * Stimulus | −0.01 | −0.05: 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.60 | 0.55 | ||

| Group * Movement * Stimulus | 0.03 | 0: 0.07 | 0.02 | 2.04 | 0.04 | ||

| Site * Group * Movement * Stimulus | 0.05 | −0.02: 0.12 | 0.03 | 1.40 | 0.16 | ||

| Covariates | Age | 0.00 | −0.01: 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.21 | 0.84 | |

| Gender (male) | −0.07 | −0.12: −0.02 | 0.03 | −2.65 | 0.009 | ||

| Gender (other) | −0.15 | −0.46: 0.15 | 0.16 | −0.97 | 0.34 | ||

| Education years | 0.00 | −0.01: 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.38 | 0.70 | ||

| AUDIT | 0.00 | −0.01: 0 | 0.00 | −0.84 | 0.40 | ||

| Lifetime illicit substance use | 0.00 | 0: 0 | 0.00 | 0.89 | 0.37 | ||

| CAAT accuracy (all trials) | 0.09 | −0.27: 0.46 | 0.19 | 0.51 | 0.61 | ||

Note. Linear mixed model results using random intercepts and restricted maximum likelihood estimation; CAN: cannabis group, CI: Confidence Interval (Wald), CON: control group, NL: Netherlands, SE: Standard Error, SD: Standard deviation, TX: Texas; CAN & NL were used as the reference categories. Significant results are presented in bold.

Simple main effects analyses revealed that the site by group interaction on overall RT was driven by faster responses in the TX-CUD group compared to the NL-CUD group (F(1,194) = 12.125, p <.001), with no difference between controls across sites (F(1,194) = 0.537, p <.465). Additionally, the NL-CUD group was significantly slower than the NL-CON group (F(1,194) = 8.920, p =.003), while the TX groups did not significantly differ (F(1,194) = 1.404, p =.237).

Follow-up analyses of the site by movement interaction revealed that TX participants regardless of group were faster to respond to the avoid trials specifically (U = 5913.00, p =.005), while site differences were not observed in RT to approach trials (U = 5252.00, p =.245).

In the CUD group, the CUD symptom count and gram/week of cannabis use were not associated with approach bias (movement * stimulus), and no site-related differences in these associations were observed (Table 6, Table 7). Cannabis attitudes also did not interact with approach bias overall or differentially across sites in the CUD group (Table 8).

Table 6.

Linear mixed effects model for the effect CUD severity on reaction time in CAAT.

| Model |

Model coefficients |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Fixed effects |

Random effects | ||||||

| B | 95 % CI (B) | SE (B) | t | p | SD | ||

| Intercept | 6.39 | 6.35: 6.42 | 0.02 | 391.18 | < 0.001 | 0.16 | |

| CUD Severity (MINI) | −0.01 | −0.05: 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.89 | 0.38 | ||

| Movement: Approach-Avoid | 0.08 | 0.06: 0.09 | 0.01 | 8.15 | < 0.001 | 0.07 | |

| Stimulus: Cannabis - Neutral | 0.00 | −0.01: 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.02 | |

| CUD Severity (MINI) * Movement | −0.01 | −0.03: 0.01 | 0.01 | −1.09 | 0.28 | ||

| CUD Severity (MINI)* Stimulus | 0.00 | −0.02: 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.64 | 0.52 | ||

| Movement * Stimulus | −0.04 | −0.06: −0.02 | 0.01 | −4.38 | < 0.001 | 0.04 | |

| CUD Severity (MINI) * Movement * Stimulus | 0.01 | −0.01: 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.68 | 0.50 | ||

| Interaction with Site | |||||||

| Intercept | 6.42 | 6.38: 6.47 | 0.02 | 304.53 | < 0.001 | 0.15 | |

| Site: NL-TX | −0.09 | −0.16: −0.03 | 0.03 | −2.88 | 0.00 | ||

| CUD Severity (MINI) | −0.02 | −0.06: 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.80 | 0.43 | ||

| Movement: Approach-Avoid | 0.09 | 0.07: 0.11 | 0.01 | 7.36 | <0.001 | 0.07 | |

| Stimulus: Cannabis - Neutral | 0.00 | −0.02: 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.32 | 0.75 | 0.02 | |

| Site * CUD Severity (MINI) | 0.02 | −0.04: 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.66 | 0.51 | ||

| Site * Movement | −0.04 | −0.07: 0 | 0.02 | −1.90 | 0.06 | ||

| Site * Stimulus | 0.01 | −0.01: 0.04 | 0.01 | 1.10 | 0.27 | ||

| CUD Severity (MINI) * Movement | −0.01 | −0.04: 0.01 | 0.01 | −1.12 | 0.27 | ||

| CUD Severity (MINI)* Stimulus | −0.01 | −0.02: 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.83 | 0.41 | ||

| Movement * Stimulus | −0.04 | −0.06: −0.01 | 0.01 | −3.17 | < 0.01 | 0.03 | |

| Site * CUD Severity (MINI) * Movement | 0.01 | −0.02: 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.75 | 0.46 | ||

| Site * CUD Severity (MINI)* Stimulus | 0.00 | −0.02: 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.35 | 0.73 | ||

| Site * Movement * Stimulus | −0.01 | −0.04: 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.32 | 0.75 | ||

| CUD Severity (MINI) * Movement * Stimulus | 0.00 | −0.02: 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.94 | ||

| Site * CUD Severity (MINI) * Movement * Stimulus | 0.01 | −0.02: 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.75 | 0.45 | ||

Note. Linear mixed model results using random intercepts and maximum likelihood estimation; CI: Confidence Interval (Wald); TX: Texas NL: Netherlands, SE: Standard Error, SD: Standard deviation. CAN & NL were used as the reference categories. Significant results are presented in bold.

Table 7.

Linear mixed effects model for the effect of cannabis use quantity (grams per week) on reaction time in CAAT.

| Model |

Model coefficients |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Fixed effects |

Random effects | ||||||

| B | 95 % CI (B) | SE (B) | t | p | SD | ||

| Intercept | 6.39 | 6.36: 6.42 | 0.02 | 378.91 | < 0.001 | 0.17 | |

| GramsWeek | −0.02 | −0.05: 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.96 | 0.34 | ||

| Movement: Approach-Avoid | 0.08 | 0.06: 0.1 | 0.01 | 7.86 | < 0.001 | 0.02 | |

| Stimulus: Cannabis - Neutral | 0.01 | −0.01: 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.96 | 0.34 | 0.08 | |

| GramsWeek * Movement | 0.00 | −0.02: 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.23 | 0.82 | ||

| GramsWeek* Stimulus | 0.01 | 0: 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.38 | 0.17 | ||

| Movement * Stimulus | −0.04 | −0.06: −0.02 | 0.01 | −4.19 | < 0.001 | 0.04 | |

| GramsWeek * Movement * Stimulus | −0.01 | −0.03: 0.01 | 0.01 | −1.05 | 0.30 | ||

| Interaction with Site | |||||||

| Intercept | 6.45 | 6.4: 6.49 | 0.02 | 274.79 | < 0.001 | 0.15749 | |

| Site: NL-TX | −0.10 | −0.17: −0.02 | 0.04 | −2.64 | 0.01 | ||

| GramsWeek | 0.07 | 0: 0.13 | 0.03 | 1.99 | 0.05 | ||

| Movement: Approach-Avoid | 0.09 | 0.06: 0.12 | 0.01 | 6.35 | < 0.001 | 0.07511 | |

| Stimulus: Cannabis - Neutral | 0.00 | −0.02: 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.95 | 0.0198 | |

| Site * GramsWeek | −0.09 | −0.17: −0.01 | 0.04 | −2.31 | 0.02 | ||

| Site * Movement | −0.04 | −0.08: 0 | 0.02 | −1.94 | 0.06 | ||

| Site * Stimulus | 0.00 | −0.05: 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.34 | 0.74 | ||

| GramsWeek * Movement | −0.01 | −0.02: 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.51 | 0.61 | ||

| GramsWeek* Stimulus | −0.01 | −0.03: 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.38 | 0.70 | ||

| Movement * Stimulus | −0.04 | −0.07: −0.01 | 0.01 | −2.70 | < 0.01 | 0.03795 | |

| Site * GramsWeek * Movement | 0.02 | −0.02: 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.97 | 0.33 | ||

| Site * GramsWeek * Stimulus | 0.02 | −0.01: 0.05 | 0.02 | 1.16 | 0.25 | ||

| Site * Movement * Stimulus | 0.01 | −0.03: 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.43 | 0.66 | ||

| GramsWeek * Movement * Stimulus | 0.01 | −0.03: 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.53 | 0.60 | ||

| Site * GramsWeek * Movement * Stimulus | −0.03 | −0.08: 0.01 | 0.02 | −1.35 | 0.18 | ||

Note. Linear mixed model results using random intercepts and maximum likelihood estimation; CI: Confidence Interval (Wald); TX: Texas NL: Netherlands, SE: Standard Error, SD: Standard deviation. CAN & NL were used as the reference categories. Note: Significant results are presented in bold.

Table 8.

Linear mixed effects model for the effect of CCQ on RT in CAAT.

| Model |

Model coefficients |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Fixed effects |

Random effects | ||||||

|

B |

95 % CI (B) |

SE (B) |

t |

p |

SD |

||

| Positive Personal | |||||||

| Intercept | 6.40 | 6.37: 6.44 | 0.02 | 316.75 | < 0.001 | 0.17 | |

| CCQ_PP | −0.02 | 0: 0.07 | 0.02 | −1.04 | 0.30 | ||

| Movement: Approach-Avoid | 0.07 | 0.06: 0.1 | 0.01 | 5.96 | < 0.001 | 0.07 | |

| Stimulus: Cannabis - Neutral | 0.00 | −0.01: 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.94 | 0.02 | |

| CCQ_PP * Movement | 0.01 | −0.01: 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.99 | 0.32 | ||

| CCQ_PP* Stimulus | 0.00 | −0.02: 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.62 | 0.54 | ||

| Movement * Stimulus | −0.03 | −0.06: −0.02 | 0.01 | −2.65 | < 0.01 | 0.03 | |

| CCQ_PP* Movement * Stimulus | −0.02 | −0.02: 0.02 | 0.01 | −1.52 | 0.13 | ||

| Positive Family/Friends | |||||||

| Intercept | 6.40 | 6.37: 6.44 | 0.02 | 379.69 | < 0.001 | 0.16 | |

| CCQ_FFP | −0.04 | −0.08: −0.01 | 0.02 | −2.72 | < 0.01 | ||

| Movement: Approach-Avoid | 0.08 | 0.06: 0.09 | 0.01 | 7.70 | < 0.001 | 0.07 | |

| Stimulus: Cannabis - Neutral | 0.00 | −0.01: 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.76 | 0.45 | 0.02 | |

| CCQ_FFP * Movement | 0.00 | −0.02: 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.20 | 0.84 | ||

| CCQ_FFP* Stimulus | 0.00 | −0.02: 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.65 | 0.52 | ||

| Movement * Stimulus | −0.04 | −0.06: −0.02 | 0.01 | −3.93 | < 0.001 | 0.03 | |

| CCQ_FFP * Movement * Stimulus | 0.00 | −0.02: 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.52 | 0.60 | ||

| Positive State/Country | |||||||

| Intercept | 6.39 | 6.36: 6.42 | 0.02 | 402.66 | < 0.001 | 0.16 | |

| CCQ_SCP | −0.04 | −0.07: −0.01 | 0.01 | −2.74 | < 0.01 | ||

| Movement: Approach-Avoid | 0.07 | 0.06: 0.09 | 0.01 | 8.27 | < 0.001 | 0.07 | |

| Stimulus: Cannabis - Neutral | 0.00 | −0.01: 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.41 | 0.69 | 0.00 | |

| CCQ_SCP * Movement | 0.01 | −0.01: 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.77 | 0.44 | ||

| CCQ_SCP* Stimulus | 0.01 | 0: 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.35 | 0.18 | ||

| Movement * Stimulus | −0.04 | −0.06: −0.02 | 0.01 | −4.42 | < 0.001 | 0.01 | |

| CCQ_SCP * Movement * Stimulus | −0.01 | −0.03: 0 | 0.01 | −1.36 | 0.17 | ||

| Negative Personal | |||||||

| Intercept | 6.40 | 6.37: 6.44 | 0.02 | 366.82 | < 0.001 | 0.16 | |

| CCQ_PN | 0.04 | 0: 0.07 | 0.02 | 2.16 | 0.033 | ||

| Movement: Approach-Avoid | 0.08 | 0.06: 0.1 | 0.01 | 7.93 | < 0.001 | 0.07 | |

| Stimulus: Cannabis - Neutral | 0.00 | −0.01: 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.90 | 0.02 | |

| CCQ_PN * Movement | 0.01 | −0.01: 0.03 | 0.01 | 1.05 | 0.30 | ||

| CCQ_PN* Stimulus | −0.01 | −0.02: 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.97 | 0.33 | ||

| Movement * Stimulus | −0.04 | −0.06: −0.02 | 0.01 | −4.06 | < 0.001 | 0.03 | |

| CCQ_PN * Movement * Stimulus | 0.00 | −0.02: 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.95 | ||

| Negative Family/Friends | |||||||

| Intercept | 6.40 | 6.36: 6.43 | 0.02 | 397.08 | < 0.001 | 0.16 | |

| CCQ_FFN | 0.04 | 0.01: 0.08 | 0.02 | 2.70 | < 0.01 | ||

| Movement: Approach-Avoid | 0.08 | 0.06: 0.09 | 0.01 | 8.14 | < 0.001 | 0.07 | |

| Stimulus: Cannabis - Neutral | 0.00 | −0.01: 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.61 | 0.54 | 0.02 | |

| CCQ_FFN * Movement | 0.01 | −0.01: 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.66 | 0.51 | ||

| CCQ_FFN* Stimulus | 0.00 | −0.01: 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.25 | 0.80 | ||

| Movement * Stimulus | −0.04 | −0.06: −0.02 | 0.01 | −4.37 | < 0.001 | 0.03 | |

| CCQ_FFN * Movement * Stimulus | 0.00 | −0.02: 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.32 | 0.75 | ||

| Negative State/Country | |||||||

| Intercept | 6.39 | 6.36: 6.42 | 0.02 | 410.13 | < 0.001 | 0.16 | |

| CCQ_SCN | 0.05 | 0.02: 0.08 | 0.01 | 3.14 | < 0.01 | ||

| Movement: Approach-Avoid | 0.07 | 0.06: 0.09 | 0.01 | 8.24 | < 0.001 | 0.07 | |

| Stimulus: Cannabis - Neutral | 0.00 | −0.01: 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.56 | 0.58 | 0.01 | |

| CCQ_SCN * Movement | −0.01 | −0.03: 0 | 0.01 | −1.55 | 0.12 | ||

| CCQ_SCN* Stimulus | −0.01 | −0.02: 0 | 0.01 | −1.60 | 0.11 | ||

| Movement * Stimulus | −0.04 | −0.06: −0.02 | 0.01 | −4.42 | < 0.001 | 0.03 | |

| CCQ_SCN* Movement * Stimulus | 0.01 | −0.01: 0.03 | 0.01 | 1.31 | 0.19 | ||

Note. Linear mixed model results using random intercepts and maximum likelihood estimation; CI: Confidence Interval (Wald); TX: Texas NL: Netherlands, SE: Standard Error, SD: Standard deviation. CAN & NL were used as the reference categories. Note: Significant results are presented in bold.

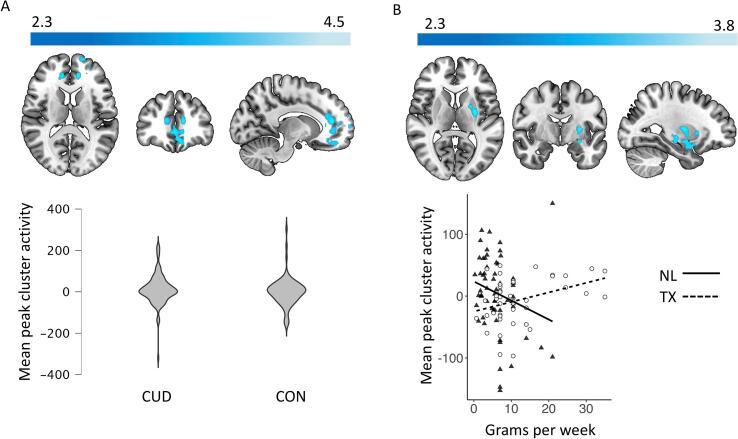

3.4. Cannabis approach bias in the brain

3.4.1. Group differences and associations with use

The CUD group showed higher approach bias activity than controls in a cluster spanning the paracingulate gyrus, anterior cingulate gyrus, frontal medial cortex, and frontal pole (Table 9, Fig. 4A). However, sensitivity analyses showed that group differences in the peak voxel were no longer significant after controlling for gender (β = −17.5, t = −1.75, p =.08), as men showed higher activity regardless of group (β = 23.5, t = 2.31, p =.02). Adding task accuracy to the model, the group difference was reduced and no longer nearing significance (β = −13.62, t = −1.35, p =.18), but the association with accuracy itself was not significant (β = −9.8, t = −1.95, p =.053). Behavioral cannabis approach bias was not related to activity in the cluster. Also, approach bias-related activity was not associated with grams per week or CUD symptom count in the overall CUD group.

Table 9.

Significant Clusters of Whole-Brain Exploratory Analyses.

|

MNI Coordinates |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster size (voxels) | Brain region | Hemisphere | x | y | z | Zmax | |

| Group Comparisons | |||||||

| CUD > CON | |||||||

| 1097 | Paracingulate gyrus, Anterior cingulate gyrus, Frontal medial cortex, frontal pole | L/R | −12 | 40 | 14 | 4.51 | |

| CON > CUD | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Group X Site | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Association with cannabis measure | |||||||

| Grams/Week | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| CUD Severity | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Site X Covariate Interactions | |||||||

| NL > TX | |||||||

| Grams/Week | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| CUD Severity | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| TX > NL | |||||||

| Grams/Week | 388 | Putamen, Amygdala, Hippocampus, Insula | L | −28 | −6 | 8 | 3.82 |

| CUD Severity | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

Note. Results of whole-brain analysis with cluster-wise correction of Z = 2.3, p <.05. CUD = Cannabis Use Disorder group; CON = non-cannabis-using controls; TX = Texas; NL = The Netherlands; CUD > CON cluster no longer significant when controlling for group differences in gender.

Fig. 4.

Mean activity extracted from the peak voxels for [(CAp > CAv) - (NAp > NAv)] contrast. Panel A - Cluster (MNI peak coordinates: x: −12 y: 40 z: 14) with significantly greater activity in the CUD group compared to CON group (Z = 2.3, p <.05 in regions encompassing the paracingulate gyrus, anterior cingulate gyrus, frontal medial cortex, and frontal pole). Panel B - Cluster of activity (MNI peak coordinates: x: −28 y: −6 z: 8) encompassing the putamen, amygdala, hippocampus, and insula with significant effect of site on the association with cannabis use (grams/week).

3.4.2. Moderating effect of site and cannabis culture

No significant group by site interactions emerged in cannabis approach bias activations and no interactions between CUD symptom count and site were observed. However, the TX-CUD group showed a stronger association between approach bias-related activation and grams of use per week than the NL-CUD group in a cluster spanning the left putamen, amygdala, hippocampus, and insula (Table 9, Fig. 4B). Sensitivity analysis on extracted peak voxel activity showed that these results hold when controlling for task accuracy and other substance use (Gram*Site: β = 4.81, t = 2.70, p =.008). Behavioral cannabis approach bias was not associated with activity in the cluster in the CUD group overall (Bias: β = 0.03, t = 0.39, p =.70), or differentially across sites (Bias*Site: β = 0.06, t = 0.39, p =.70).

Follow-up analyses replacing site with positive and negative cannabis attitudes from personal, family/friends, and state/country perspectives revealed no significant moderating effect of cannabis attitudes on the relationship between grams/week and cannabis approach bias activation in this cluster (Table 10).

Table 10.

CCQ follow-up analyses for significant whole brain site by grams interaction.

| β | SE (B) | 95 %CI | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grams*PosPersonal | −0.07 | 0.33 | −0.54: 0.54 | −0.73 | 0.46 |

| Grams*NegPersonal | −0.19 | 0.21 | −0.56: 0.27 | −1.11 | 0.27 |

| Grams*PosFamilyFriends | 0.21 | 0.21 | −0.14: 0.66 | 1.47 | 0.15 |

| Grams*NegFamilyFriends | −0.32 | 0.18 | −0.67: 0.03 | −2.11 | 0.04 |

| Grams*PosStateCountry | 0.14 | 0.07 | −0.25: 0.66 | 0.79 | 0.43 |

| Grams*NegStateCountry | −0.23 | 0.22 | −0.72: 0.13 | −1.4 | 0.17 |

Note. Bonferroni-corrected significance threshold of p = 0.008; Bootstrapping based on 5000 replicates and coefficient estimate based on the median of the bootstrapped distribution.

4. Discussion

In a cross-cultural sample of individuals with CUD from two distinct cannabis use environments, evidence for differences in cannabis attitudes and approach-bias activations in the brain emerged. Using a new event-related approach-avoidance task, individuals with CUD demonstrated a behavioral cannabis approach bias and showed heightened approach-related activity in brain regions implicated in motivational and cognitive control processes theorized to underpin addictive behavior. Furthermore, cross-cultural differences emerged in the associations between approach-related brain activity and quantity of cannabis use which could not be explained by site differences in cannabis attitudes. Taken together, these findings lend support for continued examination of the role of approach bias in CUD and highlight the importance of cross-cultural research into the underlying brain mechanisms of addictive behavior. Generalizability of the neural correlates of CUD cannot be assumed, especially when legal status and cannabis attitudes are divergent.

Regardless of site, the CUD group only made more errors in cannabis avoid trials than all other conditions and was faster to approach than avoid cannabis images specifically. Approach bias was not related to measures of use or problem severity, which is in line with previous studies [e.g. Sherman et al., 2018, Cousijn et al., 2011, Wolf et al., 2017]. Furthermore, individuals with CUD demonstrated higher cannabis approach-related activity in the ACC, paracingulate gyrus, frontal medial cortex, and frontal pole compared to the control group. These regions have all been shown to activate during tasks requiring a wide array of cognitive control-related functions, such as conflict/performance monitoring and response inhibition in the ACC and paracingulate gyrus specifically (Shenhav et al., 2016, Van Veen et al., 2001, Zhang et al., 2017). This is in line with the theoretical model of approach-avoidance tasks proposing a conflict between motivationally salient approach responses and the required response inhibition to perform the task. A sensitivity analysis accounting for lower task accuracy as well as the overrepresentation of men in the CUD group showed that the heightened cannabis approach-related activity in the CUD group was at least partially driven by task performance and the number of men, with men showing higher activity regardless of group. Adding covariates to the models likely reduced the power to detect group effects, but it also highlights the importance of investigating gender differences in the neural correlates of CUD.

Many site differences in cannabis attitudes were observed. In contrast to our hypothesis, participants from TX were more positive themselves and perceived their friends and family to be more positive about cannabis than the NL participants, despite the more permissive legal environment in the NL. While individuals with CUD were more positive and less negative in their personal and perceived family and friends’ beliefs than non-users across sites, the TX-CUD group reported even less negative personal and family and friend’s attitudes than the NL-CUD group. These findings highlight the mismatch between legal climate and perceptions of harms and benefits, and the importance of assessing both. Speculatively, individuals who use cannabis regularly in an illegal environment such as TX may have more positive beliefs about its effects because those who perceive more negative effects may choose to abstain from use given the potential legal consequences. TX users also reside within the larger context of the US, in which permissive cannabis policies are spreading and perceptions of harm are decreasing (Levy, Mauro, Mauro, Segura, & Martins, 2021). However, despite the observed differences, cannabis attitudes were not related to cannabis approach bias at the level of brain or behavior.

Cross-cultural differences did emerge in the association between severity of use and approach-bias related activity in addiction-related regions. In the NL sample, higher use was associated with less activity in the left putamen, amygdala, insula, and hippocampus, regions that consistently activate in response to cannabis stimuli in heavy cannabis users (Sehl et al., 2021). In the TX-CUD group, the reverse was found. The differential association between use and approach-bias related activity was not explained by differences in other substance use, task-performance, or cannabis attitudes. While these cross-cultural differences are difficult to interpret, they further stress the need for cross-cultural research to explore which factors may contribute to site differences in underlying brain mechanisms. For instance, cannabis potency is implicated in the severity of the effects of cannabis use on the brain (Kroon et al., 2020). Potency, as well as method of administration (e.g. bongs, joints, vaping, oral, dermal etc.) and co-use with other substances (e.g. tobacco), differ across regions and cultures (Hindocha, Freeman, Ferris, Lynskey, & Winstock, 2016). Given the lack of tobacco co-users in the TX sample and lack of identical data about method of administration across sites, we were unable to examine the role of these factors in the cross-cultural differences we observed. These are important factors for future cross-cultural research to identify what mechanisms may underlie differences in the neural correlates of CUD.

Strengths of this study included the novel cross-cultural comparison and the close matching of CUD groups in TX and NL on key variables, including CUD symptom count, frequency of cannabis use, mental well-being (depression, anxiety, cross-cutting mental health symptoms), and alcohol and illicit substance use. However, several limitations are important to consider. First, the NL- and TX-CUD groups were not matched on tobacco use and too few TX participants smoked cigarettes to allow for sensitivity analyses. Furthermore, most cannabis users in the Netherlands, and Europe (Hindocha et al., 2016) mix tobacco into their joints, which is relatively uncommon in the US. While this presents a challenge for study design and statistical control, the included samples are ecologically valid and future research should examine whether cross-cultural differences in the neural mechanisms of CUD may be attributable to tobacco co-use. For example, there is some evidence of a modulating role of nicotine on the endocannabinoid system which may mitigate effects of cannabis and modulate cognitive function (Subramaniam, McGlade, & Yurgelun-Todd, 2016) and the neural correlates of addiction, such as cue reactivity [e.g. Kuhns, Kroon, Filbey, and Cousijn (2021)]. Second, the TX-CUD group reported more grams per week of cannabis use than the NL group. While approach bias findings were not related to grams per week at the brain or behavioral level, it remains unclear whether site-related differences in cannabis effects may be due to differences in either cannabis or cannabinoid exposure. Future cross-cultural research should aim to use biospecimen analyses (e.g. hair, urine, saliva), as recommended by the iCannToolkit (Lorenzetti et al., 2021, 2021), in order to examine the role of cannabinoid exposure given potential differences in cannabis products between regions (Chandra, Radwan, Majumdar, Church, Freeman, & ElSohly, 2019).

In conclusion, these findings provide further evidence for the presence of cannabis approach bias on a brain and behavioral level in CUD. Furthermore, differences between TX and NL in the relationship between severity of use and approach-related brain activity point towards cross-cultural research as a novel and important direction in neurocognitive research into the mechanisms of CUD. While cannabis attitudes themselves differed significantly between the two sites, there was no evidence they modulated approach behavior. Culture is a dynamic and complicated concept, particularly in relation to cannabis as the social and legal landscape continues to change worldwide. Pinpointing the cultural differences that may influence the underlying neural mechanisms is a key challenge and opportunity for future research.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2023.100507.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- American Psychiatric Association, 2013 . DSM-5 self-rated level 1 cross-cutting symptom measures-Adult. Diagnostic Stat. Man. Ment. Disord., . 5th ed. p. 734–739.

- Askari M.S., Keyes K.M., Mauro P.M. Cannabis use disorder treatment use and perceived treatment need in the United States: Time trends and age differences between 2002 and 2019. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2021;229 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey J.A., Epstein M., Roscoe J.N., Oesterle S., Kosterman R., Hill K.G. Marijuana Legalization and Youth Marijuana, Alcohol, and Cigarette Use and Norms. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2020;59:309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D., Mächler M., Bolker B., Walker S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software. 2015;67:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Beck A.T., Steer R.A., Ball R., Ranieri W.F. Comparison of Beck depression inventories -IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1996;67:588–597. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, S., Radwan, M.M., Majumdar, C.G., Church, J.C., Freeman, T.P., ElSohly, M.A., 2019. New trends in cannabis potency in USA and Europe during the last decade (2008–2017). European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 2691. 2019;269:5–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Coalson D.L., Raiford S.E., Saklofske D.H., Weiss L.G. WAIS-IV; 2010. WAIS-IV Clinical Use and Interpretation; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Cousijn J., Goudriaan A.E., Ridderinkhof K.R., van den Brink W., Veltman D.J., Wiers R.W. Approach-Bias Predicts Development of Cannabis Problem Severity in Heavy Cannabis Users: Results from a Prospective FMRI Study. PLoS One1. 2012;7:e42394. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousijn J., Goudriaan A.E., Wiers R.W. Reaching out towards cannabis: Approach-bias in heavy cannabis users predicts changes in cannabis use. Addiction. 2011;106:1667–1674. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03475.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousijn J., Snoek R.W.M., Wiers R.W. Cannabis intoxication inhibits avoidance action tendencies: A field study in the Amsterdam coffee shops. Psychopharmacology. 2013;229:167–176. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3097-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousijn J., van Benthem P., van der Schee E., Spijkerman R. Motivational and control mechanisms underlying adolescent cannabis use disorders: A prospective study. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. 2015;16:36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgendi M.M., Bartel S.J., Sherry S.B., Stewart S.H. Injunctive Norms for Cannabis: A Comparison of Perceived and Actual Approval of Close Social Network Members. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2022;2022:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Esteban O., Markiewicz C.J., Blair R.W., Moodie C.A., Isik A.I., Erramuzpe A., et al. fMRIPrep: A robust preprocessing pipeline for functional MRI. Nature Methods. 2019;16:111–116. doi: 10.1038/s41592-018-0235-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field M., Eastwood B., Bradley B.P., Mogg K. Selective processing of cannabis cues in regular cannabis users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;85:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming C.B., Guttmannova K., Cambron C., Rhew I.C., Oesterle S. Examination of the Divergence in Trends for Adolescent Marijuana Use and Marijuana-Specific Risk Factors in Washington State. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2016;59:269–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindocha C., Freeman T.P., Ferris J.A., Lynskey M.T., Winstock A.R. No Smoke without Tobacco: A Global Overview of Cannabis and Tobacco Routes of Administration and Their Association with Intention to Quit. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2016;7:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm, S., Sandberg, S., Kolind, T., Hesse, M., 2014. The importance of cannabis culture in young adult cannabis use, 19, 251–256. Http://DxDoiOrg/103109/146598912013790493.

- Holm S., Tolstrup J., Thylstrup B., Hesse M. Neutralization and glorification: Cannabis culture-related beliefs predict cannabis use initiation. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy. 2016;23:48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobus J., Taylor C.T., Gray K.M., Meredith L.R., Porter A.M., Li I., et al. A multi-site proof-of-concept investigation of computerized approach-avoidance training in adolescent cannabis users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2018;187:195–204. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroon E., Kuhns L., Hoch E., Cousijn J. Heavy cannabis use, dependence and the brain: A clinical perspective. Addiction. 2020;115:559–572. doi: 10.1111/add.14776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhns L., Kroon E., Filbey F., Cousijn J. Unraveling the role of cigarette use in neural cannabis cue reactivity in heavy cannabis users. Addiction Biology. 2021;26:e12941. doi: 10.1111/adb.12941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy N.S., Mauro P.M., Mauro C.M., Segura L.E., Martins S.S. Joint perceptions of the risk and availability of Cannabis in the United States, 2002–2018. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2021;226 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loijen A., Vrijsen J.N., Egger J.I.M., Becker E.S., Rinck M. Biased approach-avoidance tendencies in psychopathology: A systematic review of their assessment and modification. Clinical Psychology Review. 2020;77 doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzetti V., Hindocha C., Petrilli K., Griffiths P., Brown J., Castillo-Carniglia Á., et al. The International Cannabis Toolkit (iCannToolkit): A multidisciplinary expert consensus on minimum standards for measuring cannabis use. Addiction. 2021 doi: 10.1111/add.15702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Vispo C., Dias P.C. Risk Perceptions and Cannabis Use in a Sample of Portuguese Adolescents and Young Adults. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2022;20:595–606. [Google Scholar]

- Philbin M.M., Mauro P.M., Santaella-Tenorio J., Mauro C.M., Kinnard E.N., Cerdá M., et al. Associations between state-level policy liberalism, cannabis use, and cannabis use disorder from 2004 to 2012: Looking beyond medical cannabis law status. The International Journal on Drug Policy. 2019;65:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prashad S., Milligan A.L., Cousijn J., Filbey F.M. Cross-Cultural Effects of Cannabis Use Disorder: Evidence to Support a Cultural Neuroscience Approach. Current Addiction Reports. 2017;4:100–109. doi: 10.1007/s40429-017-0145-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2022.

- Robinson T.E., Berridge K.C. The incentive sensitization theory of addiction: Some current issues. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 2008;363:3137–3146. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders J.B., Aasland O.G., Babor T.F., De La Fruente J.R., Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption-II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehl H., Terrett G., Greenwood L.M., Kowalczyk M., Thomson H., Poudel G., et al. Patterns of brain function associated with cannabis cue-reactivity in regular cannabis users: A systematic review of fMRI studies. Psychopharmacology. 2021;238:2709–2728. doi: 10.1007/s00213-021-05973-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan D.V., Lecrubier Y., Sheehan K.H., Amorim P., Janavs J., Weiller E., et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenhav, A., Cohen, J.D., Botvinick, M.M.,2016. Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and the value of control. Nat Neurosci 2016 1910;19:1286–1291. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sherman B.J., Baker N.L., Squeglia L.M., McRae-Clark A.L. Approach bias modification for cannabis use disorder: A proof-of-principle study. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2018;87:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2018.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger, C.D., 2010. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Corsini Encycl. Psychol., Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Subramaniam P., McGlade E., Yurgelun-Todd D. Comorbid Cannabis and Tobacco Use in Adolescents and Adults. Current Addiction Reports. 2016;3:182–188. doi: 10.1007/s40429-016-0101-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe J., Regner M., Sakai J., Martinez D., Gowin J. Neuroimaging reward, craving, learning, and cognitive control in substance use disorders: Review and implications for treatment. The British Journal of Radiology. 2019;92 doi: 10.1259/bjr.20180942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turna J., Balodis I., Van Ameringen M., Busse J.W., MacKillop J. Attitudes and Beliefs Toward Cannabis Before Recreational Legalization: A Cross-Sectional Study of Community Adults in Ontario. Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research. 2022;7:526–536. doi: 10.1089/can.2019.0088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Drug Market Trends of Cannabis and Opioids. World Drug Rep., Vienna: United Nations; 2022.

- Ustun B., Adler L.A., Rudin C., Faraone S.V., Spencer T.J., Berglund P., et al. The World Health Organization Adult Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Self-Report Screening Scale for DSM-5. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:520–526. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Veen V., Cohen J.D., Botvinick M.M., Stenger V.A., Carter C.S. Anterior Cingulate Cortex, Conflict Monitoring, and Levels of Processing. NeuroImage. 2001;14:1302–1308. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Sydow K., Lieb R., Pfister H., Höfler M., Wittchen H.U. What predicts incident use of cannabis and progression to abuse and dependence? A 4-year prospective examination of risk factors in a community sample of adolescents and young adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2002;68:49–64. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller L., Erk S., Pozzi E., Toenders Y.J., Haswell C.C., Büttner M., et al. ENIGMA HALFpipe: Interactive, reproducible, and efficient analysis for resting-state and task-based fMRI data. Human Brain Mapping. 2022;43:2727–2742. doi: 10.1002/hbm.25829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. No Title; Pearson: 2012. WAIS-IV-NL: Wechsler adult intelligence scale–Nederlandstalige bewerking. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, P.A., Salemink, E., Wiers, R.W., 2017. Attentional retraining and cognitive biases in a regular cannabis smoking student population. Http://DxDoiOrg/101024/0939-5911/A000455. 2017;62:355–365.

- Woolrich M.W., Jbabdi S., Patenaude B., Chappell M., Makni S., Behrens T.…Smith S.M. Bayesian analysis of neuroimaging data in FSL. Neuroimage. 2009;45:S173–S186. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L.T., Swartz M.S., Brady K.T., Hoyle R.H., NIDA AAPI Workgroup Perceived cannabis use norms and cannabis use among adolescents in the United States. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2015;64:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R., Geng X., Lee T.M.C. Large-scale functional neural network correlates of response inhibition: An fMRI meta-analysis. Brain Structure & Function. 2017;222:3973–3990. doi: 10.1007/s00429-017-1443-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.