Abstract

Background

COVID-19 is associated with an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE). This study examined the prevalence of VTE among acute ischaemic stroke (AIS) patients with and without a history of COVID-19.

Methods

We identified AIS hospitalisations of Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) beneficiaries aged ≥65 years from 1 April 2020 to 31 March 2022. We compared the prevalence and adjusted prevalence ratio of VTE among AIS patients with and without a history of COVID-19.

Results

Among 283 034 Medicare FFS beneficiaries with AIS hospitalisations, the prevalence of VTE was 4.51%, 2.96% and 2.61% among those with a history of hospitalised COVID-19, non-hospitalised COVID-19 and without COVID-19, respectively. As compared with patients without a history of COVID-19, the prevalence of VTE among patients with a history of hospitalised or non-hospitalised COVID-19 were 1.62 (95% CI 1.54 to 1.70) and 1.13 (95% CI 1.03 to 1.23) times greater, respectively.

Conclusions

There appeared to be a notably higher prevalence of VTE among Medicare beneficiaries with AIS accompanied by a current or prior COVID-19. Early recognition of coagulation abnormalities and appropriate interventions may help improve patients’ clinical outcomes.

Keywords: COVID-19, Stroke, Risk Factors

INTRODUCTION

Several studies have suggested that infection with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19 may predispose patients to an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), especially among hospitalised patients.1 2 VTE is a common medical complication in patients with acute ischaemic stroke (AIS) and is recognised as a negative quality indicator of stroke care.3 Few studies have examined the association between COVID-19 and VTE among AIS patients.4 We examined this relationship among Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) beneficiaries aged ≥65 years who were hospitalised with AIS from 1 April 2020 to 31 March 2022.

Methods

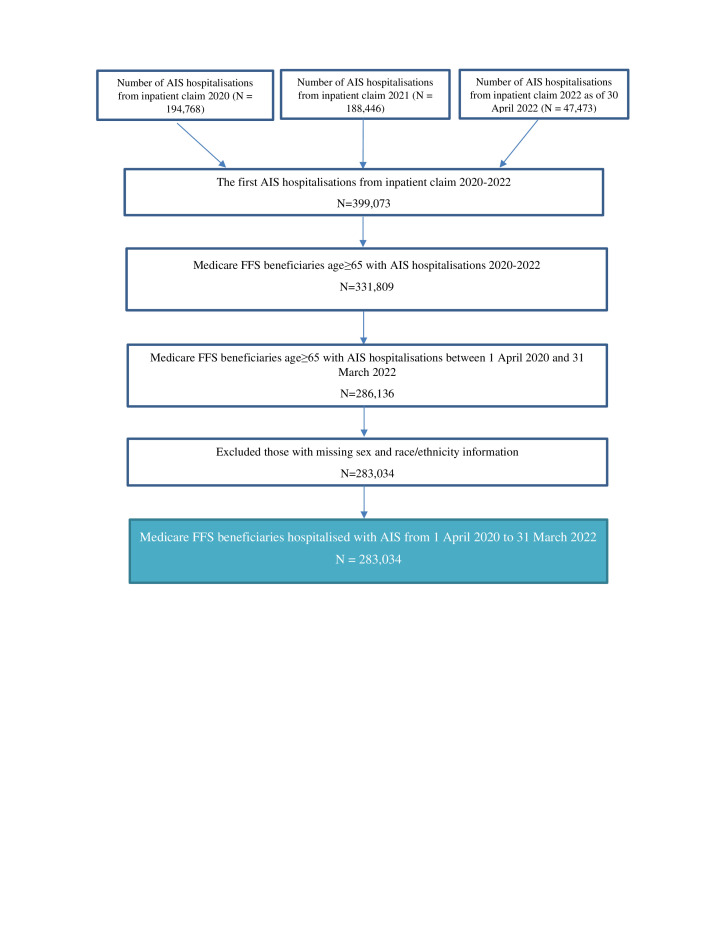

We used the real-time Medicare monthly files to identify the beneficiaries for this retrospective study. AIS was defined as having a hospital admission with primary diagnosis of International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) code I63. The final analytical study population had 283 304 Medicare FFS beneficiaries diagnosed with AIS (figure 1). We obtained the first diagnosis of COVID-19 (ICD-10-CM U07.1) through claims from any type of healthcare setting and classified by hospitalisation status to reflect the severity of COVID-19. If the first occurrence of COVID-19 was identified through the inpatient setting claims, it was defined as hospitalised COVID-19. We defined AIS patients with a history of COVID-19 if the dates of the first COVID-19 diagnoses were earlier than AIS admission dates. For each AIS admission, we identified the beneficiaries with VTE through secondary diagnoses codes (ICD-10-CM I80–I82, I26).

Figure 1.

Study flowchart of Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) beneficiaries aged ≥65 years hospitalised with acute ischaemic stroke (AIS) in the USA, 2020–2022

We calculated the median age and IQR and the distribution of age group, sex, race/ethnicity, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) scores, VTE, death and medical history of comorbidity conditions among AIS patients by three groups: with history of hospitalised COVID-19; with history of non-hospitalised COVID-19 and without COVID-19. About 37% of AIS patients had missing NIHSS scores, and we used the multiple imputation to impute the missing values with 25 imputed datasets using PROC MI in SAS. We used SAS PROC GENMOD’s log-binomial regression to estimate the prevalence ratio (PR) and 95% CIs for all patients and by age group, sex and race/ethnicity group. We calculated the adjusted PR (adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, NIHSS score, history of stroke/transient ischaemic attack, ischaemic heart disease, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, chronic kidney disease, acute myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and tobacco use) of VTE by comparing: AIS patients with a history of hospitalised COVID-19 or non-hospitalised COVID-19 versus those without COVID-19.

Data availability

The Medicare data used in this study cannot be shared by authors because of the data usage agreement, but the investigators can access to these data by application to Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Results

Among total of 283 034 Medicare FFS beneficiaries with AIS admissions, 9.5% patients had a history of COVID-19, while 52% of them classified as hospitalised, and 2.7% patients had VTE (online supplemental table 1). The stroke severity measured by NIHSS score was higher among AIS patients with a history of COVID-19 than those without COVID-19. AIS patients with a history of hospitalised COVID-19 had the mortality rate of 41.0%, compared with 31.9% with a history of non-hospitalised COVID-19, and 30.8% among those without COVID-19. Among 26 770 AIS patients with a history of COVID-19, the median days between COVID-19 and AIS dates were 97 days (IQR 9–275 days).

svn-2022-001814supp001.pdf (49.3KB, pdf)

VTE prevalence was 4.51%, 2.96% and 2.61% among AIS patients with a history of hospitalised, non-hospitalised COVID-19 and without COVID-19, respectively (table 1). As compared with AIS patients without COVID-19, adjusted PRs of VTE was 1.62 (95% CI 1.54 to 1.70) and 1.13 (95% CI 1.03 to 1.23) among those with a history of hospitalised or non-hospitalised COVID-19, respectively. Patients aged 65–74 years had the highest prevalence of VTE as compared with those aged 75–84 years and those aged ≥85 years. Compared with other race/ethnicity groups, non-Hispanic black patients had the highest prevalence of VTE at 6.53% among those with a history of hospitalised COVID-19, 3.86% among those with non-hospitalised COVID-19 and 3.97% among those without COVID-19.

Table 1.

Prevalence and adjusted prevalence ratios of VTE among AIS patients with and without COVID-19 by demographic characteristics

| Variables | Total N (%) | AIS patients with hospitalised COVID-19 (N=13 873) | AIS patients with non-hospitalised COVID-19 (N=12 897) | AIS patients without COVID-19 (N=256 264) | P value* | PR (95% CI)† Hospitalised COVID-19 vs non-COVID-19 AIS |

PR (95% CI)† Non-hospitalised COVID-19 vs non-COVID-19 AIS |

|||

| No with VTE | Prevalence (95% CI) | No with VTE | Prevalence (95% CI) | No with VTE | Prevalence (95% CI) | |||||

| Total | 283 034 | 626 | 4.51 (4.18 to 4.87) | 382 | 2.96 (2.68 to 3.27) | 6697 | 2.61 (2.55 to 2.68) | <0.001 | 1.62 (1.54 to 1.70) | 1.13 (1.03 to 1.23) |

| Age in groups | ||||||||||

| 65–74 | 93 060 (32.9) | 231 | 5.39 (4.75 to 6.10) | 149 | 3.62 (3.09 to 4.23) | 2458 | 2.90 (2.79 to 3.02) | <0.001 | 1.69 (1.56 to 1.83) | 1.24 (1.08 to 1.40) |

| 75–84 | 106 608 (37.7) | 249 | 4.82 (4.27 to 5.44) | 122 | 2.54 (2.13 to 3.02) | 2603 | 2.69 (2.59 to 2.80) | <0.001 | 1.68 (1.55 to 1.81) | 0.94 (0.76 to 1.12) |

| 85+ | 83 366 (29.5) | 146 | 3.31 (2.82 to 3.88) | 111 | 2.79 (2.32 to 3.36) | 1636 | 2.18 (2.08 to 2.29) | <0.001 | 1.44 (1.27 to 1.60) | 1.27 (1.08 to 1.46) |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | 125 356 (44.3) | 311 | 5.18 (4.65 to 5.77) | 160 | 2.91 (2.50 to 3.39) | 2915 | 2.56 (2.47 to 2.65) | <0.001 | 1.89 (1.77 to 2.00) | 1.13 (0.98 to 1.29) |

| Female | 157 678 (55.7) | 315 | 4.00 (3.59 to 4.46) | 222 | 3.00 (2.63 to 3.41) | 3782 | 2.66 (2.57 to 2.74) | <0.001 | 1.43 (1.31 to 1.54) | 1.13 (1.00 to 1.27) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 230 539 (81.5) | 451 | 4.36 (3.98 to 4.77) | 313 | 2.99 (2.68 to 3.34) | 5211 | 2.48 (2.42 to 2.55) | <0.001 | 1.70 (1.61 to 1.80) | 1.21 (1.09 to 1.32) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 27 673 (9.8) | 125 | 6.53 (5.51 to 7.73) | 45 | 3.86 (2.89 to 5.14) | 976 | 3.97 (3.73 to 4.22) | <0.001 | 1.56 (1.37 to 1.74) | 0.95 (0.66 to 1.24) |

| Hispanic | 13 702 (4.8) | 32 | 2.94 (2.07 to 4.13) | 15 | 1.91 (1.13 to 3.15) | 310 | 2.62 (2.35 to 2.93) | 0.388 | 1.06 (0.70 to 1.42) | 0.72 (0.21 to 1.24) |

| Other race | 11 120 (3.9) | 18 | 3.41 (2.13 to 5.36) | 9 | 1.86 (0.93 to 3.56) | 200 | 1.98 (1.72 to 2.27) | 0.109 | 1.60 (1.11 to 2.08) | 0.93 (0.27 to 1.59) |

*P value comparing the difference in prevalence of VTE between the Medicare FFS beneficiaries hospitalised with AIS across three groups of COVID-19 status based on t-test.

†PRs were estimated using the log-binomial regression models adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, NIHSS score, history of medical conditions and tobacco use.

AIS, acute ischaemic stroke; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; PR, prevalence ratio; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Discussion

Our findings suggested a notably higher prevalence of VTE among AIS patients with a history of COVID-19 among Medicare FFS beneficiaries aged ≥65 years. Compared with AIS patients without COVID-19, the prevalence of VTE among AIS patients with a history of hospitalised or non-hospitalised COVID-19 were 1.62 and 1.13 times greater, respectively. Non-Hispanic black AIS patients had the highest prevalence of VTE consistent with the findings of other studies.5 6

Many studies reported significant increases in incidence of VTE among hospitalised COVID-19 patients ranging from 1.0% to 85% with an average of 17%.1 2 7 Our study showed a 4.51% of VTE among AIS patients with a history of hospitalised COVID-19, which was lower than the average reported previously. However, if studies were restricted to those that included ≥200 patients with COVID-19, then the pooled incidence of VTE was approximately 4%.1 While most studies focused on thrombotic complications among the hospitalised patients with COVID-19, especially among those ICU admissions, we are not aware of any study that examined the association between AIS patients with history of non-hospitalised COVID-19. Our findings suggested that the prevalence of VTE among AIS patients is notably higher among those with milder symptoms of COVID-19 that do not require hospitalisation when compared with those without history of COVID-19.

VTE is a serious complication among AIS patients and is associated with poor prognosis.8 VTE prophylaxis is one of the 10 evidence-based stroke core measures endorsed by the Joint Commission, American Heart Association and Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention.9 Most AIS patients receive standard VTE prophylaxis within 48 hours of admission.9 10 In the context of COVID-19, vigilance in identifying opportunities for early VTE prophylaxis or interventions to help improve patients’ clinical outcomes is recommended based on perceived coagulation abnormalities among AIS patients with a history of COVID-19.

This study has several limitations. We may have missed some beneficiaries with diagnosed COVID-19, VTE and AIS, or incorrect diagnoses dates, due to the usage of preliminary Medicare monthly data. NIHSS scores were based on the ICD-10 codes, which may not be accurate. We are unable to determine whether a history of COVID-19 may affect the severity and comorbidities of stroke, or it may directly affect the incidence of VTE. Finally, VTE was identified through the secondary diagnostic fields, and we cannot determine if VTE was a pre-existing or incident diagnosis.

Conclusions

Our findings suggested that AIS patients with a history of COVID-19 had a notably higher prevalence of VTE, especially among those with more severe COVID-19. Clinicians should be aware of this increased risk regardless of standard VTE prophylaxis provided to AIS patients. Early recognition of coagulation abnormalities and appropriate interventions may help improve patients’ clinical outcomes.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors have contributed to this manuscript, including study design, writing the manuscript and significant editing of manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Human Subjects Coordinator determined that this study did not require review for human subjects protections because the data did not contain personal identifiers and were not originally collected specifically for this study. Therefore, the requirement of informed consent was waived.

References

- 1. Jiménez D, GarcÍa-Sanchez A, Rali P, et al. Incidence of VTe and bleeding among hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest 2021;159:1182–96. 10.1016/j.chest.2020.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kollias A, Kyriakoulis KG, Lagou S, et al. Venous thromboembolism in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vasc Med 2021;26:415–25. 10.1177/1358863X21995566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tong X, Kuklina EV, Gillespie C, et al. Medical complications among hospitalizations for ischemic stroke in the United States from 1998 to 2007. Stroke 2010;41:980–6. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.578674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ma A, Kase CS, Shoamanesh A, et al. Stroke and thromboprophylaxis in the era of COVID-19. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2021;30:105392. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.105392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Heit JA, Beckman MG, Bockenstedt PL. Comparison of characteristics from White- and black Americans with venous thromboembolism: a corss-sectional study. Am J Hematol 2021;30:1053925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. White RH, Keenan CR. Effects of race and ethnicity on the incidence of venous thromboembolism. Thromb Res 2009;123:S11–17. 10.1016/S0049-3848(09)70136-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res 2020;191:145–7. 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cushman M, Barnes GD, Creager MA, et al. Venous thromboembolism research priorities: a scientific statement from the American heart association and the International Society on thrombosis and haemostasis. Circulation 2020;142:e85–94. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Overwyk KJ, Yin X, Tong X, et al. Defect-free care trends in the Paul Coverdell National acute stroke program, 2008-2018. Am Heart J 2021;232:177–84. 10.1016/j.ahj.2020.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gąsecka A, Borovac JA, Guerreiro RA, et al. Thrombotic complications in patients with COVID-19: pathophysiological mechanisms, diagnosis, and treatment. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2021;35:215–29. 10.1007/s10557-020-07084-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

svn-2022-001814supp001.pdf (49.3KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

The Medicare data used in this study cannot be shared by authors because of the data usage agreement, but the investigators can access to these data by application to Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.