Graphical abstract

Keywords: Green solvents, Ultrasonic-assisted extraction, Date fruit, Response surface method, Artificial neural network

Highlights

-

•

NADES-USAE system is developed for the first time for date sugar extraction.

-

•

Utilizing COSMO-RS, potential NADESs were molecularly screened.

-

•

RSM and ANN are used to optimize the extraction process for the highest sugar yield.

-

•

ChCl: CA:H2O (1:1:1) yielded 87.8 g/100 g TSC, 43.1% higher than CHWE.

-

•

The study paves the way for the use of untapped food resources.

Abstract

The aim of this study is to develop an environmentally friendly and effective method for the extraction of nutritious date sugar using natural deep eutectic solvents (NADES) and ultrasound-assisted extraction (USAE). The careful design of a suitable NADES-USAE system was systematically supported by COSMO-RS screening, response surface method (RSM) and artificial neural network (ANN). Initially, 26 natural hydrogen bond donors (HBDs) were carefully screened for sugar affinity using COSMO-RS. The best performing HBDs were then used for the synthesis of 5 NADES using choline chloride (ChCl) as HBA. Among the synthesized NADES, the mixture of ChCl, citric acid (CA) and water (1:1:1 with 20 wt% water) resulted in the highest sugar yield of 78.30 ± 3.91 g/100 g, which is superior to conventional solvents such as water (29.92 ± 1.50 g/100 g). Further enhancements using RSM and ANN led to an even higher sugar recovery of 87.81 ± 2.61 g/100 g, at conditions of 30 °C, 45 min, and a solvent to DFP ratio of 40 mL/g. The method NADES-USAE was then compared with conventional hot water extraction (CHWE) (61.36 ± 3.06) and showed 43.1% higher sugar yield. The developed process not only improves the recovery of the nutritious date sugar but also preserves the heat-sensitive bioactive compounds in dates, making it an attractive alternative to CHWE for industrial utilization. Overall, this study shows a promising approach for the extraction of nutritive sugars from dates using environmentally friendly solvents and advanced technology. It also highlights the potential of this approach for valorizing underutilized fruits and preserving their bioactive compounds.

1. Introduction

Phoenix dactylifera, commonly known as date palm, is among the most ancient trees cultivated by humans, with its origins believed to date back to around 4000BCE in southern Iraq [1]. Date fruit is one of the most abundant fruits in the world and contains a high amount of carbohydrates varying between 50 and 80 g/100 g, mainly in the form of simple reducing sugars (fructose and glucose) and non-reducing sugars (sucrose) [2], [3]. In addition, date fruit is a rich source of nutrients such as proteins, carbohydrates (sugars and dietary fiber), amino acids (aspartic, glutamic, leucine, glycine, lysine, and proline acids), vitamins (folate, niacin, thiamine, pyridoxine, riboflavin, vitamins A and C), and minerals (copper, magnesium, phosphorus, iron, potassium, and manganese) [4]. It also contains phytochemicals such as phenolic acids, tannins, flavonols, flavones, anthocyanins, phytoestrogens, and carotenoids, and has strong antioxidant potential. These bioactive compounds help maintain health and reduce the risk of various chronic diseases such as cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. They have anti-inflammatory, anti-mutagenic, anti-cancer, nephroprotective, and hemolytic properties [5]. Dates are high-energy foods (160–320 kcal/100 g) that can be consumed directly as fresh fruit or processed into various edible products such as date paste, syrup, or powder, which are used as ingredients for making cookies or cakes [6]. Despite the high nutritional value of date fruit, it is one of the most underutilized foods to be industrially exploited [3], which makes the development of sustainable and green date sugar extraction methods essential.

Conventional methods for extracting sugars from fruit pulp usually involve the use of aqueous solutions of organic solvents such as ethanol or methanol. However, these solvents have a number of disadvantages, including high volatility, flammability, and toxicity, which can have a negative impact on the environment and the sustainability of the extraction process [7], [8]. At the industrial level, sugar is extracted from sugarcane and sugar beet by a heat-intensive, water-based extraction process that involves several chemical treatments [9]. Date fruits are considered as an excellent source for the production of refined sugar, which has not yet been exploited [10]. Currently, the extraction process of liquid date sugar (date syrup) suffers from low sugar yield and extraction efficiency, where 40–50% of the sugar content is lost during the pressing and mixing process [11]. Moreover, most of the vital nutrients are lost as waste or during the prolonged hot water extraction process at temperatures around 70 °C [11]. Therefore, there is a need to find green yet powerful alternative solvents that can extract sugars and other heat-sensitive bioactive compounds under mild temperature conditions.

Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) have been promoted as potential alternatives to classical organic solvents as well as to various aqueous systems in different extraction processes [12]. In principle, DESs can be defined as mixtures of two or more hydrogen-bond donors (HBD) and hydrogen-bond acceptors (HBA) linked by hydrogen bonding interactions. The resulting eutectic mixture exhibits a remarkable decrease in melting point and unique physicochemical properties compared to the starting components [13]. Depending on the careful selection of constituents, DESs possess several valuable properties such as negligible volatility, high solvating ability, sustainability, biodegradability in combination with acceptable pharmaceutical toxicity profiles [14]. DESs derived from natural materials (e.g., sugars, amino acids, organic acids, choline derivatives, etc.) have been favorably received by the scientific community as it meets the criteria for a green solvent, leading to the designation of these types of solvents as natural DESs (NADESs). Recently, the use of NADESs in the extraction of bioactive compounds by various advanced techniques (ultrasound-assisted extraction (USAE), microwave-assisted extraction, pressurized liquid extraction, etc.) has attracted considerable attention [15]. NADES-based USAE methods have been reported for the effective extraction of various phytochemicals such as polyphenols [16], polysaccharides [17], sugars [17], flavonoids [18], carotenoids [19], etc. For example, Gómez et al. [7] studied the use of different NADESs for the extraction of monosaccharides from ripe bananas. Among the NADESs studied, malic acid: beta-alanine: water (1:1:3) with an additional 30 g water/100 g solvent was the most effective in extracting sugars from banana puree. The solvent achieved a sugar recovery of 106.9 g/100 g solvent (at 25 °C, 30 min), which was a much more effective extraction than the traditional reference solvents such as ethanol and water, which recovered 79.7 and 71.5 g/100 g, respectively. Zhang et al. investigated the USAE of polysaccharides from Dioscorea opposita Thunb using choline chloride (ChCl) and 1,4-butanediol, achieving an optimal extraction yield of 15.98% using 32.9 v% water at 94 °C for 45 min. This DES-USAE was better than hot water extraction and ultrasound-assisted water-based extraction [17].

Despite the great properties of most NADESs, their high viscosities result in a reduced solute diffusion rate in the extraction medium and thus lower solubilization capacity and extraction yield. However, these problems can be solved by careful selection of the NADES's constituents, composition, and operating temperature [20]. In addition, the controllable addition of water can reduce the high viscosity of NADES [21]. However, excessive addition of water (>50% v/v) could break the hydrogen bond network structure and thus compromise the integrity of DES. Another challenge that hinders the use of NADES in food applications is the recovery of analytes after extraction. There are few reported separation techniques based on the type of NADES used or analytes to be recovered, such as liquid–liquid extraction using a different solvent [22], temperature or pH change for stimuli responsive NADESs [23], countercurrent chromatographic techniques [24], supercritical CO2 extraction, and recrystallization [25]. Most of the reported NADESs used for the extraction of bioactive compounds are hydrophilic (highly polar). For this class of NADESs, the technique of countercurrent separation proved to be effective for the recovery of bioactive material, e.g. flavonoids, from a hydrophilic glucose:ChCl:water (2:5:5 mol/mol) NADES [24]. Moreover, NADES usually consist of food-grade components, so extracts obtained with these green solvents can be consumed by humans without the need for further separation and purification [14].

Due to the limited number of studies on the extraction of saccharides with NADES, considerable effort is required to discover and evaluate potential NADES combinations as viable alternatives to conventional solvents. One of the key advantages of NADESs is their versatility in terms of solvent combinations. By varying the ratio and combination of HBAs and HBDs, solvent properties can be tailored to specific extraction requirements, providing a virtually endless array of options. This allows the use of a wide range of potential NADESs for various applications. In addition, the use of computational tools such as COSMO-RS (Conductor-like Screening Model for Real Solvents) can assist in the selection of appropriate NADESs for specific applications. COSMO-RS is a quantum chemistry-based method that can predict various thermodynamic and transport properties of solvents, as well as the solubility of target compounds in the solvent, providing a more efficient method for screening potential NADESs to extract particular bioactive substances, including glucose, fructose, and sucrose.

To the best of our knowledge, no studies have been published in the literature on the use of NADESs for USAE of sugars from date fruits. Therefore, the aim of this study was to develop a method for the sustainable extraction of sugars from date fruits. This was achieved through a systematic three-stage process. In the first stage, 26 carefully selected naturally occurring HBDs were screened for the extraction of the three major sugars in date fruits (glucose, fructose, and sucrose) using COSMO-RS. Based on the screening results, the five best performing HBDs were then used - with ChCl as HBA - to prepare different NADES. These NADESs were then characterized for their physicochemical properties, evaluated for sugar extraction from date fruit powder, and compared with some conventional solvents (ethanol and water) and aquoline (ChCl:water). In the second stage, USAE operating conditions were further improved using a response surface method with a Box-Behnken design (RSM-BBD) to maximize total sugar content (TSC). In the third stage, an artificial neural network (ANN) was developed using the generated experimental data and its predictive performance was compared with the statistical RSM-BBD model. In addition, the chemical and morphological changes in the extract and residual biomass were analyzed using FT-IR and SEM. The systematic framework used in this study demonstrates the potential of using advanced computational tools such as COSMO-RS, RSM-BBD, and ANN as robust tools for selecting and optimizing new task-specific solvents. In addition, the results of this study provide a sustainable and efficient method for date sugar extraction and open new opportunities for the utilization of un- and under-utilized fruits.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals, materials, and reagents

Choline chloride (ChCl, purity ≥ 98%) and oxalic acid (OA, purity 98%) were obtained from Sigma Aldrich, anhydrous citric acid (CA, purity 99.5%) from Research-lab, gallic acid monohydrate (GA, purity 99%) from Alfa Aesar, triethylene glycol (TEG, purity 99%) from Acros Organics, and ethanolamine (EA, purity 99%) from VWR. All chemicals were used as received without further purification. Sigma Aldrich standards with a purity of 99% of sulfuric acid, phenol, and sucrose were procured and utilized without any additional refinement. Deionized H2O with a conductivity of nS/cm was employed for both preparation of samples and cleaning.

Local date fruit powder (DFP) of Sukkari type was procured from a production plant located in Abu Dhabi. The dates were exposed to sunlight and allowed to dry for a period of 2–3 days. Afterward, it was pulverized to acquire the DFP. An electromagnetic sieve machine (AS −200 model, Retsch, Germany) was utilized to sift the obtained DFP. The DFP particles ranged in size from 1000 to 63 µm. More specifically, the majority of the DFP particles (80.6%) were of a moderately fine size (500–250 µm). The remaining 6.4%, 8.1%, and 4.9% were categorized as coarse (>500 µm), fine (<250 and > 125 µm), and very fine particle sizes (<125 µm), respectively. For this research, DFP particles that were of medium size (500–250 µm) were utilized.

2.2. Molecular screening for potential NADES using COSMO-RS

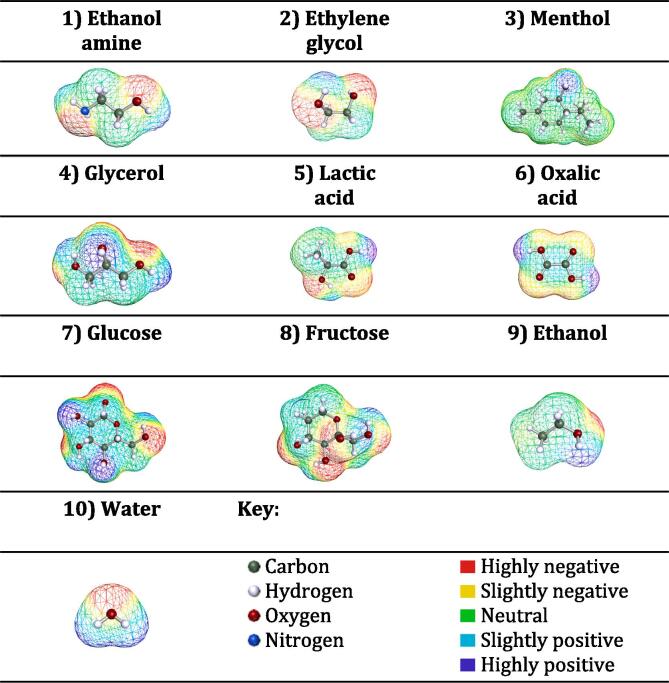

COSMO-RS is a molecular modeling method that uses quantum chemistry and statistical mechanics to predict the properties of pure fluids and mixtures based on their geometry and screening charge density. More details on the theories and applications of COSMO-RS can be found elsewhere [26], [27]. In this study, BIOVIA COSMOtherm software, version 2022, was used to screen the HBDs to be used for the extraction of sugars from date fruits. Accordingly, a list of 26 naturally occurring and commonly used HBDs was compiled based on a literature survey and the geometries of the molecules were developed using Turbomole software (TmoleX19 4.5.1) with the BP_TZVP_22.ctd parameterization file. Fig. 1 shows the geometrically optimized 3-D structures of six representative examples of HBDs as well as those of glucose and fructose and the benchmark solvents ethanol and water. Then, COSMOtherm was used to predict the activity coefficient at infinite dilution () of glucose, fructose, and sucrose in the 26 HBDs at 25 °C. The is defined as follows in COSMO-RS [28]:

| (1) |

where is the predicted the chemical potential of the HBD, and is the predicted chemical potential of the saccharide (glucose, fructose, or sucrose).

Fig. 1.

3-D COSMO-RS structures of representative examples of 6 HBDs along with the glucose and fructose, and the benchmark solvents ethanol and water.

2.3. Nadess synthesis and characterization

In this work, choline chloride (ChCl) was selected as HBA for the synthesis of NADESs. ChCl is an abundant and natural quaternary ammonium salt that is commonly used as a green HBA with various types of HBDs for the synthesis of NADESs for various applications, including extraction [29]. In addition, ChCl is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and is used as a food additive at the industrial level [15]. The DES, which contains ChCl and an HBD, is referred to as type III eutectics, which are easy to prepare and have relatively unreactive with water; many are biodegradable and relatively inexpensive [30].

Different methods have been used to prepare the NADES mixtures due to the differences in melting point and solid phase of the DES constituents. To prepare NADESs with organic acids as HBD (e.g., CA, OA, and GA), the desired molar ratio of HBA (ChCl) and HBD, as indicated in Table 1, was measured and placed in a sealed glass bottle with a magnetic stirring bar. The bottle was then placed in an oil bath that provided uniform temperature distribution from all sides and heated using a hotplate. The stirring speed and temperature were set to 350 rpm and 50 °C, respectively. As for the other NADESs (i.e., with EA or TEG as HBD), the desired mass of components was placed in sealed glass vials and shaken with an incubation shaker (KS 4000, IKA®, Germany) at 300 rpm and 80 °C. It should be noted that the eutectic molar ratios of the combinations were determined by surveying relevant literature. The corresponding references for each mixture are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

The components, molar ratios, and acronyms of the NADESs used in this work.

| NADES | HBA | HBD 1 | HBD 2 | Molar ratio | Added water content (wt%) | Liquid at RT | Acronym | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NADES 1 | Choline chloride | Oxalic acid | H2O | 1:1 | 10 wt% | Y | ChCl:OA:W | [15], [31], [32] |

| NADES 2 | Citric acid | H2O | 1:1:1 | 20 wt% | Y | ChCl:CA:W | [15], [33], [34], [35] | |

| NADES 3 | Gallic acid·H2O | – | 2:1 | – | N | ChCl:GA.W | [36] | |

| NADES 4 | Ethanolamine | – | 1:7 | – | Y | ChCl:EA | [37], [38], [39] | |

| NADES 5 | Triethylene glycol | – | 1:3 | – | Y | ChC:TEG | [40] | |

| NADES 6 | H2O | – | 3:1 | – | Y | ChCl:W | [41], [42], [43] |

The physical properties of the successfully synthesized NADESs were measured, including refractive index, viscosity (dynamic and kinematic), density, and critical properties. The density and viscosities were measured using an Anton Paar SVM 3001 (Austria), and the refractive index was determined using a digital refractometer (PR −101, Atago Co. Ltd., Japan) at room temperature. Additionally, the critical properties of the NADESs were estimated using the modified Lydersen-Joback-Reid (LJR) group contribution method (GC), along with the application of the Lee-Kesler mixing rules. A slight variation of the Lee-Kesler equations was used to account for ternary NADESs. More information on the methods and equations used can be found in the supplemental materials.

2.4. Ultrasonic-assisted NADESs extraction

The extraction process of date sugars from DFP involved utilizing an ultrasonic bath (USC 2100 THD, VWR, UK) with settings of 45 kHz and 12 W/L. The solvents were mixed with the DFP at varying liquid-to-solid ratios (L/S) ranging from 10 to 40 mL/g. The mixtures were then placed into the ultrasonic bath at settings of; sonication power of 6 W per liter, temperatures ranging between 30 and 70 °C, and extraction times of 20–60 min (Fig. 2). Five NADESs (Table 1), selected based on COSMO-RS were tested for sugar extraction.

Fig. 2.

Nutritious date sugar extraction using natural deep eutectic solvent and ultrasonic assisted extraction.

For comparison, the USAE of sugars from DFP with conventional solvents, water and ethanol, was also investigated. For this purpose, 0.25 g DFP and 10 g solvent were mixed at an L/S ratio of 40 in 25 mL vials. The vials were capped and placed in an ultrasonic bath at 50 °C for 40 min. The extracts were centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 25 min to separate the supernatant from the residue. The supernatant was further filtered using a PTFE membrane syringe filter with a pore size of 45 µm. Samples were stored at 4 °C until further analysis.

NADES-USAE was also compared with conventional hot water extraction (CHWE). CHWE was performed in a 50 mL beaker heated to an extraction temperature of 75 °C using a hot water bath while the mixture was continuously stirred at a stirring rate of 400 rpm. Extractions were performed for 40 min at a ratio of 40 mL/g. After extraction, the liquid product was filtered and analyzed [44], [45].

2.5. Sugar quantification in the extract

The TSC was measured by the spectrophotometric phenol–sulfuric acid technique [46]. The approach is based on the reaction of sugars with strong acids to form furan by-products. To perform the analysis, a diluted sample of the extract was placed in a test tube. Then, 0.05 mL of 80% (w/w) phenol and 5 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid were added and the solution was thoroughly mixed using a vortex mixer. Afterward, the mixture was cooled down to 298.15 K, and the degree of light absorption was measured via a UV/Visible spectrophotometer (DR 5000, Lange, USA) at a wavelength of 490 nm. The TSC of the sample was then determined by comparing the absorbance with a calibration curve prepared using sucrose as the standard. The extraction yield was calculated using the following equation:

| (2) |

where represents the total sugar concentration of the diluted sample, in units of grams of sucrose equivalent per milliliter (g-suc/mL). represents the dilution factor, represents the total volume of the filtered extract, in milliliters (mL), and represents the mass of DFP used in the extraction, in grams (g).

2.6. Modeling and optimization of extraction using RSM and ANN

2.6.1. RSM modeling

The NADES system with the best performance selected from the initial experimental screening results was used for further extraction optimization studies. The process parameters considered were liquid-to-solid ratio (L/S = 10–40 mL/g), temperature (T = 30–70 °C), and time (t = 20–60 min). The Response Surface Method with Box-Behnken Design (RSM-BBD) was applied to determine the optimal extraction conditions that yield the highest TSC (g/100 g).

2.6.2. ANN modeling

ANN was used to model the nonlinear relationship between selected process parameters and response variables using the experimental dataset generated from BBD. The JMP SAS Pro software (version 16) was used to construct the multilayer perceptron architecture of the ANN and train the model. Four 1- hidden layer architectures (with 1–4 neurons), and 12 2- hidden layer architectures were evaluated for their predictive performance. The simplest two hidden layer architecture had one neuron in both layers (1–1), while the most complex architecture had four neurons in both layers (4–4). To ensure the robustness of the model, k-fold cross-validation with a k-value of 5 was implemented to split the data into multiple training and validation sets. This allowed the optimal number of hidden layers and neurons to be determined by a trial-and-error method based on the highest performance in the validation set.

The equations in the ANN model use several parameters to describe the behavior of the neural network, including the weight () between neurons, the input () to a specific neuron (), the hidden layer () being considered, and the bias () of the neuron. The hyperbolic tangent () function is also incorporated into the equations, effectively constraining the output of each neuron to a range of [−1,1], representing the degree of activation or deactivation. This allows for a precise and controlled representation of the behavior and output of the network. The output of the neuron (j) is defined by the combination of these parameters as follows:

| (3) |

2.6.3. Data evaluation

Evaluation metrics such as root mean square error (), coefficient of determination (), and average absolute relative deviation () were used to evaluate and compare the adequacy of the developed models, which are expressed in the following equations:

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

where and represent the experimental and the predicted values, respectively. and represent the mean average value and the total number of data points, respectively. The models with high accuracy have high and low and .

2.7. Characterization of date sugar extract and residue

The extract and residue (remaining biomass after extraction) obtained from the NADES-USAE and CHWE methods were characterized to evaluate the impact of using the NADES on the biomass and overall extraction efficiency.

2.7.1. Color analysis

The color characteristics of the extracts obtained from both the NADES-USAE and CHWE methods were determined using a colorimeter (Colorimeter PCE-CSM 5, PCE Instruments, UK) operating with the CIELab* system. This system uses. (lightness), (red-green axis), and (yellow-blue axis) values to provide a visually linear color specification [46]. The colorimeter was first calibrated using a white ceramic disk included with the instrument. To determine the colorimetric parameters, the liquid extracts were placed in transparent vials and the instrument was placed on top of the vial to analyze the color. Then, the parameters, , , and . were measured and recorded. The total color difference () was then calculated using the following equation [47], [48]:

| (7) |

where , , and represent the color measurements of the NADES-USAE samples, and , , and represent the color measurements of the Water-USAE reference sample. All measurements were conducted in duplicate, and the results were reported as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). The degree of saturation or chroma () and the hue value () for all the measurements are listed in Table S1.

2.7.2. FT-IR analysis

The Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectra of raw DFP, the residue obtained from CHWE, and the residue obtained from NADES-USAE were determined using an ATR FT-IR (Bruker ALPHA II, UK) in the wavelength 4000–400 cm−1. To obtain accurate spectra, a background spectrum of air was used to correct each spectrum by averaging 64 scans. Data were acquired and analyzed with the OPUS software (version 4.0, Bruker, France).

2.7.3. Morphological analysis

The surface morphologies of the raw DFP and biomass residues after the extraction process were studied using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (FEI, Quanta 3D FIB, USA) at 5 kV and different magnification levels (200X and 1000X). The samples (raw DFPs and residues) were attached to aluminum stubs with double-sided carbon tape and coated with gold–palladium to prevent sample charging.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Design expert v 13 (DX Stat Ease Inc, Minneapolis, USA). The analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used to evaluate the results, and statistical significance was deemed present for -values that were below 0.05. The measurements were conducted in duplicates, and the results were presented as the average value ± the standard deviation.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Molecular screening for potential NADESs using COSMO-RS

The selection of natural HBDs for the extraction of glucose, fructose, and sucrose was conducted using COSMO-RS at 25 °C. The activity coefficient of species i at infinite dilution “” was used as an evaluation parameter to determine the most effective HBDs for saccharide extraction. The solubility of a compound in a solvent is inversely proportional to its activity coefficient in the system. The predicted results presented in Fig. 3, revealed that the activity coefficients of the solutes in the HBDs were in the following order: glucose > fructose ≫ sucrose, indicating that the HBDs can effectively solubilize sucrose, followed by fructose and glucose.

Fig. 3.

COSMO-RS predicted activity coefficients at infinite dilution for sucrose, glucose, and fructose at 25 °C.

To identify the optimal HBDs, common solvents used in biomass valorization, such as acetic acid, glycerol, ethylene glycol, lactic acid, and glycolic acid, were considered due to their availability and environmental friendliness. Although these solvents performed well, they were all ranked lower than the typical benchmark (ethanol). Nevertheless, among the top five ranked HBDs, other promising natural candidates were also given special consideration, such as oxalic acid, ethanolamine, gallic acid, citric acid, and triethylene glycol. These constituents, in combination with a suitable HBA, can serve as a starting point for the development of highly effective natural DESs for the efficient extraction of sugars. Prediction analysis also revealed that the activity coefficient of sugars generally decreases as the HBDs become more acidic. This is due to the fact that compounds with lower pKa values, such as oxalic acid and citric acid, exhibit larger negative . It can be concluded that compounds with a –COOH group have excellent capacity and affinity for monosaccharides, probably due to their π–π bonding via their carbonyl group (C = O) and hydrogen bonds (- OH). Ethanolamine and triethylene glycol were also found to be promising. At the other end of the spectrum, the least effective HBDs are quite hydrophobic (menthol, thymol, sorbitol). This is likely due to the large number of hydroxyl groups in glucose, fructose, and sucrose, which make it difficult for these saccharides to dissolve in these nonpolar HBDs.

3.2. Characterization of successfully synthesized NADES

According to the results obtained from COSMO-RS screening, five green HBDs that have high sugar solubility, namely ethanolamine (EA), triethylene glycol (TEG), citric acid (CA), oxalic acid (OA), and gallic acid (GA) with ChCl as HBA, were selected as potential NADESs for sugar extraction from DFP. These NADESs were experimentally synthesized along with the 'aquoline' NADES (ChCl:W 3:1), which was also considered due to its unique properties [41]. However, only five of the six potential NADESs formed liquids at room temperature and the reported molar ratios, as shown in Table 1. The synthesis of ChCl: GA.W at a molar ratio of 2:1 gave a yellowish solid mixture and was therefore excluded from further analysis. Synthesis of the organic acid-based NADESs (ChCl:OA and ChCl: CA) resulted in very viscous mixtures, so a certain amount of water was added to reduce the viscosity. The dilution of these natural organic acid-based NADESs with water was carefully controlled to maintain a water content of 50 wt% or less to preserve the molecular structures of these NADESs and avoid negative effects on their performance [7], [49].

The physical and critical properties of the synthesized NADESs are listed in Table 2. The densities of all NADESs were greater than those of water. ChCl: EA and ChCl:W had the lowest density and viscosity values, while ChCl:OA:W and ChCl: CA:W had the highest density values. Viscosity plays an important role in mass transfer as it governs the rate at which solutes are extracted, and is therefore an essential property for assessing the suitability and effectiveness of solvents. The highest dynamic viscosity value was observed for ChCl:OA:W, suggesting that the extraction process may be limited by solvent diffusion and energy-intensive processing may be required to improve extraction. Moreover, the high viscosity values are attributed to the extensive and complex hydrogen bonding between HBD and HBA [25]. The lowest viscosity value was observed for ChCl:W (aquoline), which was attributed to the presence of water as HBD. Similarly, the lowest refractive index (RI) values were observed in ChCl: CA:W and ChCl:W due to the presence of water. On the other hand, the highest RI values were observed in ChCl: EA and ChCl: TEG that were not diluted with water during synthesis. Gómez et al. [7] reported an inverse linear relationship between water content and RI, which is consistent with the results of this study. NADESs with low RI can penetrate the sample very quickly, resulting in higher extraction efficiency compared to solvents with high RI [50].

Table 2.

Physical and critical properties of the successfully synthesized NADESs.

| NADES 1 ChCl:OA:W |

NADES 2 ChCl:CA:W |

NADES 4 ChCl:EA |

NADES 5 ChC:TEG |

NADES 6 ChCl:W |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density, ρ (g/cm3) | 1.236 | 1.247 | 1.043 | 1.127 | 1.092 |

| Dynamic viscosity, µ (mPa.s) | 253.25 | 81.39 | 37.33 | 81.91 | 14.57 |

| Kinematic viscosity, ν (mm2/s) | 204.57 | 65.28 | 35.77 | 72.67 | 13.35 |

| RI (nD) | 1.468 | 1.457 | 1.471 | 1.472 | 1.456 |

| Molecular weight, M (g/mol) | 74.77 | 96.87 | 70.90 | 147.53 | 109.22 |

| Critical temperature, Tc (K) | 658.36 | 738.86 | 593.79 | 712.69 | 613.19 |

| Critical pressure, Pc (bar) | 65.05 | 54.96 | 49.70 | 27.38 | 37.23 |

| Critical volume, Vc (mL/mol) | 191.85 | 237.45 | 227.08 | 441.22 | 321.37 |

| Acentric factor, ω | 0.735 | 0.919 | 0.728 | 1.020 | 0.657 |

The critical properties of a solvent, whether it consists of a pure component or a mixture, are essential for the development of thermodynamic models. However, in the case of eutectic mixtures such as DESs, empirical data cannot be obtained because of the decomposition of the DES's components before the critical conditions. To estimate the critical properties of these mixtures, the group contribution method was used. The GC method, as used in the framework of Valderrama et al. [51], was found to be effective in estimating the critical properties of various ionic liquids. The same framework was used for alkanolamine-based DESs [39] and terpenoid-based DESs [52], [53], resulting in very accurate estimates. For the ChCl-based NADESs shown in Table 2, the modified Lydersen-Joback-Reid method [51] was used to estimate the critical properties of the individual components that make up the various NADESs. Then, the Lee Keseler mixing rules [54] were used to obtain the critical properties of the binary NADES compositions, and an extension of the known equations was used for the ternary-based NADESs (ChCl: CA:W and ChCl:OA:W). The acentric factors and critical properties, such as critical temperature, pressure, and volume, of the studied NADESs are listed in Table 2. Using the determined critical properties of the NADESs, their densities at different temperatures were predicted from 20 to 80 °C using the modified Rackett equation [55], and the results are shown in Fig. S1.

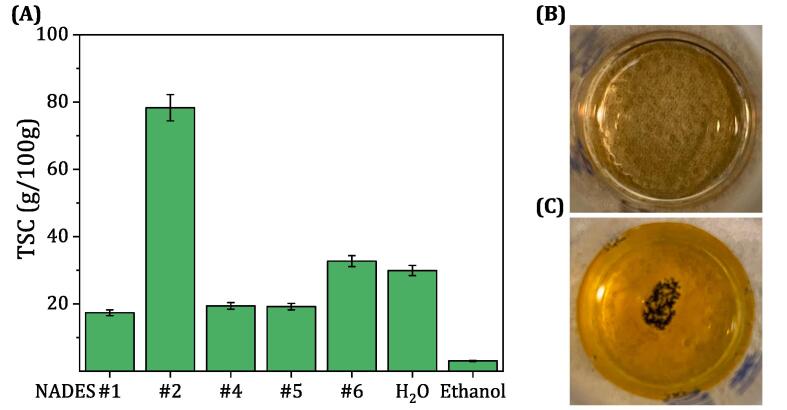

3.3. NADES selection

Fig. 4(A) illustrates the TSC in the extracts obtained with different NADESs and with conventional solvents (namely, water and ethanol) at fixed conditions of 50 °C, 40 min, and L/S of 40 mL/g. The results show that all the NADESs studied were more effective than ethanol in extracting sugars, indicating their high solubility and superior extraction ability. However, among the NADESs studied, ChCl:OA:W exhibited the lowest total sugar extraction (17.37 ± 0.87 g/100 g), which may be due to the degradation of saccharides by acid Maillard reactions with OA, as reported in a previous study [56]. Moreover, the extract obtained with ChCl:OA:W had the darkest brown color among all solvents and this color became darker with time, which could also indicate the progressive degradation of various components in the extract. The highest sugar extraction yield was obtained with ChCl:CA:W, at 78.30 ± 3.91 g/100 g, compared to the other NADESs and conventional solvents. ChCl: EA and ChCl: TEG had similar extraction yields (19.42 ± 0.97 and 19.20 ± 0.96 g/100 g, respectively), and ChCl:W (aquoline) gave the second highest extraction yield (32.72 ± 1.64 g/100 g), indicating improved sugar solubility compared with pure water (29.92 ± 1.50 g/100 g) due to the strong hydrogen bonding between ChCl and water. In general, ChCl-based NADESs were reported to effectively remove hemicellulose and lignin from biomass with HBDs such as organic acids (mono- or di-carboxylic acids) or polyols, thereby increasing the extraction yield [57]. The selected NADES (ChCl: CA:W) showed very interesting preservation properties. Furthermore, the other NADESs investigated in this study (ChCl:EA, ChCl:TEG, ChCl:OA:W, and ChCl:W) exhibited comparable preservation properties. After the extracts were stored in a dark environment for several weeks, fungal growth was observed in the water-USAE extract. In contrast, the extract dissolved in ChCl: CA:W was free of any visible growth, indicating the fungal inhibitory effect of this type of solvent. Fig. 4(B) and (C) show the pictorial images of the extracts obtained with ChCl: CA:W and water after 4 weeks of storage. Based on all the obtained results, ChCl: CA:W was selected for further analysis and optimization of the process conditions of NADES-based USAE.

Fig. 4.

(A) Date sugar extraction yields using the USAE with the screened NADESs and conventional solvents. Images of the extracts obtained using (B) NADES#2 (ChCl:CA:W), and (C) water after 4 weeks of storage in the dark.

3.4. RSM modeling

To ensure efficient ultrasound-assisted extraction of date sugars using NADES, process optimization was performed with BBD based on RSM. Three independent variables, namely extraction temperature (), extraction time (), and liquid-to-solid ratio (), were studied and the measured response was TSC. The results presented in Table 3 show that the TSC value varied between 31.91 and 86.97 g/100 g DFP. The center point runs (#3, #4, #13, #14, and #16) showed minimal variation in TSC, indicating good repeatability of the experiment.

Table 3.

Factorial and center points of the Box-Behnken experimental design for the NADES-USAE system with the experimental total sugars content (TSC) and total color difference (ΔE). a, b

| Run# | A- Temperature (°C) |

B- Time (min) |

C- L/S ratio (mL/g) |

TSC (g/100 g) |

ΔE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 70 ( 1) | 40 (0) | 40 ( 1) | 44.96 | 15.57 |

| 2 | 70 ( 1) | 20 ( 1) | 25 (0) | 81.26 | 14.03 |

| 3 | 50 (0) | 40 (0) | 25 (0) | 64.20 | 9.05 |

| 4 | 50 (0) | 40 (0) | 25 (0) | 60.06 | 8.65 |

| 5 | 70 ( 1) | 40 (0) | 10 ( 1) | 47.15 | 16.41 |

| 6 | 50 (0) | 20 ( 1) | 10 ( 1) | 35.95 | 12.78 |

| 7 | 30 ( 1) | 20 ( 1) | 25 (0) | 31.91 | 7.45 |

| 8 | 70 ( 1) | 60 ( 1) | 25 (0) | 41.75 | 15.14 |

| 9 | 30 ( 1) | 60 ( 1) | 25 (0) | 79.45 | 7.89 |

| 10 | 50 (0) | 60 ( 1) | 40 ( 1) | 57.32 | 7.54 |

| 11 | 30 ( 1) | 40 (0) | 40 ( 1) | 86.97 | 5.57 |

| 12 | 50 (0) | 20 ( 1) | 40 ( 1) | 74.96 | 6.16 |

| 13 | 50 (0) | 40 (0) | 25 (0) | 52.88 | 9.90 |

| 14 | 50 (0) | 40 (0) | 25 (0) | 55.03 | 8.95 |

| 15 | 50 (0) | 60 ( 1) | 10 ( 1) | 33.84 | 12.54 |

| 16 | 50 (0) | 40 (0) | 25 (0) | 68.16 | 8.55 |

| 17 | 30 ( 1) | 40 (0) | 10 ( 1) | 37.89 | 11.49 |

standard uncertainty:.

maximum uncertainty:.

The ANOVA method was employed to conduct a statistical examination of the model with the two-factor interaction of RSM-BBD to evaluate the relationship between the targeted response (TSC) and the parameters of the NADES-USAE process. The results of this analysis are summarized in Table 4. One linear effect () and two interaction effects ( and ) were found to be significant (-value < 0.05). The remaining linear and interaction terms and all quadratic terms were found to be insignificant (-value > 0.05). The experimental data were found to be well-aligned with the developed model equation as indicated by the lack of fit result (-value > 0.05). Furthermore, , , and values of 0.844, 12.05%, and 6.75 g/100 g, respectively, indicate a reliable fit between the model and the experimental measurements. The RSM-BBD model is represented using the following equation:

| (8) |

where , , and are the temperature (°C), time (min), and the liquid-to-solid ratio (mL/g), respectively, and is the TSC (g/100 g). A detailed comparison of the predictions made by the RSM-BBD model for all factorial points and axial center points, alongside the corresponding experimental data and statistical evaluation, can be found in Spreadsheet S.1 of the Supplementary Materials.

Table 4.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the two-factor interaction model between the NADES-USAE operating parameters and TSC.

| Source | Sum of Squares | Degrees of freedom | Mean Square | F-value | -valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 4180.61 | 6 | 696.77 | 9.00 | 0.0015 | S |

| A-Temperature | 55.77 | 1 | 55.77 | 0.7200 | 0.4160 | NS |

| B-Time | 17.16 | 1 | 17.16 | 0.2215 | 0.6480 | NS |

| C-L/S ratio | 1495.49 | 1 | 1495.49 | 19.31 | 0.0013 | S |

| AB | 1894.61 | 1 | 1894.61 | 24.46 | 0.0006 | S |

| AC | 657.33 | 1 | 657.33 | 8.49 | 0.0155 | S |

| BC | 60.26 | 1 | 60.26 | 0.7781 | 0.3984 | NS |

| Residual | 774.52 | 10 | 77.45 | |||

| Lack of Fit | 615.04 | 6 | 102.51 | 2.57 | 0.1900 | NS |

| Pure Error | 159.49 | 4 | 39.87 | |||

| Total | 4955.13 | 16 | ||||

S: significant, and NS: not significant.

To gain insight into the interaction effect of two variables on the response when the other variables are held constant at the center point (zero level), the 3-D surfaces and the 2-D contours were generated from Eq. (8). First, Fig. 5(A) and (D) demonstrate the effects of temperature and time at a fixed L/S of 25 mL/g. It is obvious that these variables have a strong effect on TSC, as shown by the -value of 0.0006 (-value < 0.01). In addition, the TSC increases when the extraction temperature and time are varied from 30 to 50 °C and 20 to 40 min, respectively. However, at higher extraction temperatures and longer extraction times, the TSC decreases, which can be attributed to the degradation of saccharides [58]. Similarly, Fig. 5(B) and (E) show the dual effects of temperature and L/S at a fixed time of 40 min. This two-way interaction was also found to be statistically significant as shown by the results of ANOVA (-value = 0.0155). Moreover, TSC increases with increasing L/S ratio and extraction temperature. Finally, Fig. 5(C) and (F) show that time and L/S have a linear effect, indicating that their dual impact on TSC is insignificant (-value = 0.398 > 0.05). The maximum sugar recovery (87.81 ± 2.61 g/100 g) was obtained at a temperature of 30 °C, an extraction time of 45 min, and a ratio of 40 mL/g.

Fig. 5.

3-D surface and 2-D contour plots showing the interaction effects on TSC. Interaction of extraction temperature and time (A, D), extraction temperature and liquid-to-solid ratio (B, E), and extraction time and liquid-to-solid ratio (C, F).

3.5. ANN modeling

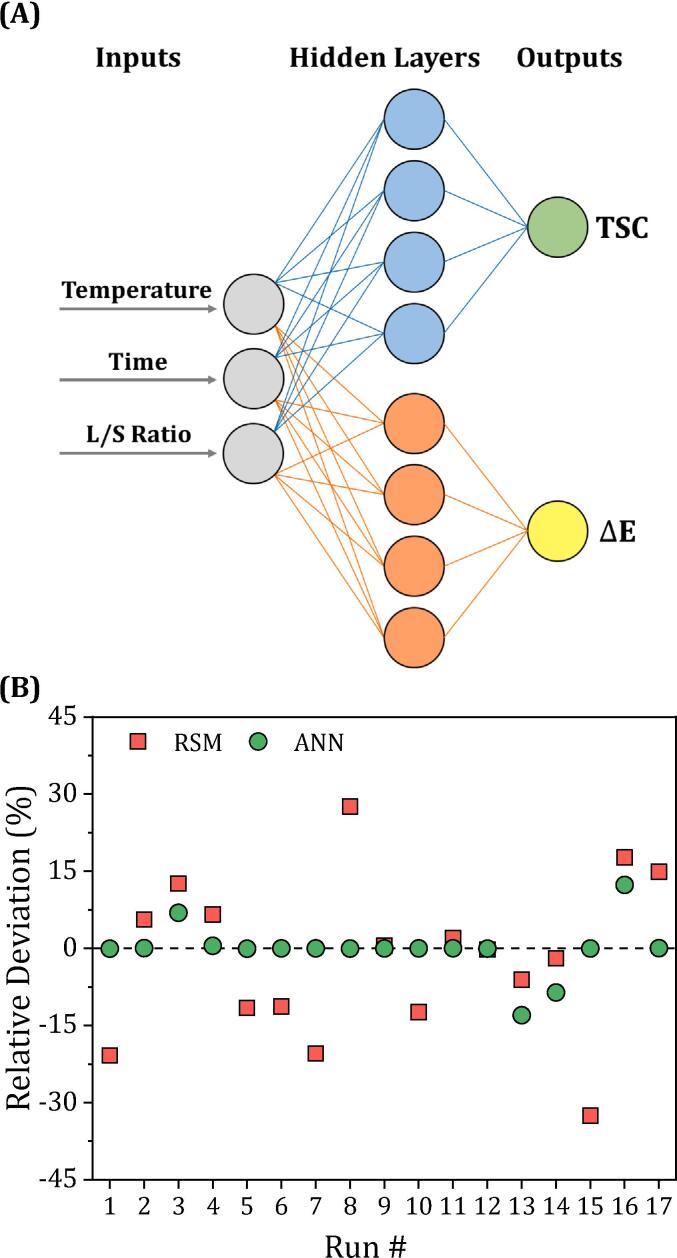

ANNs have revolutionized the field of engineering with their unparalleled predictive and estimation capabilities. In particular, ANN outperforms traditional modeling techniques such as RSM in terms of prediction accuracy. To demonstrate this, we developed an ANN to model the nonlinear relationship between three independent variables (temperature, time, and L/S ratio) and the target output (TSC) using the Broyden-Fletcher-Goldfarb-Shanno (BFGS) algorithm. To ensure optimal performance, we performed thorough hyperparameter tuning, which is illustrated in . A total of 16 different ANN architectures were trained and evaluated, systematically varying the number of neurons and layers to determine the configuration that achieved the lowest and highest values. The results showed that the optimal topology consisted of a single hidden layer with 4 neurons, which offered the best trade-off between model complexity and performance. A schematic diagram of the 3–4-1 ANN model can be found in Fig. 6(A). The values for the weights and biases of the best performing ANN model can be found in Spreadsheet S.2 of the supplementary materials.

Fig. 6.

(A) Schematic diagram of the 3–4-1 ANN models for predicting TSC and ΔE. (B) Relative deviation plot for the RSM and ANN models in predicting TSC.

The evaluation metrics listed in Table 5, such as, , , and (0.968, 2.45%, and 3.07, respectively) show a good agreement between the ANN predictions and the experimental values. Moreover, the ANN model was found to have higher level of accuracy in fitting the experimental data than the RSM model, as shown by the plot of relative deviation (RD %) in Fig. 6(B). The superior predictive capabilities of ANNs can be attributed to their ability to approximate any nonlinear system, while RSM is limited to approximating systems with second order polynomials.

Table 5.

Statistical evaluation metrics for the RSM and ANN models in predicting TSC and ΔE.

| Metric | RSM | ANN |

|---|---|---|

| TSC | ||

| 0.844 | 0.968 | |

| 12.05 | 2.45 | |

| 6.75 | 3.07 | |

| ΔE | ||

| 0.977 | 0.994 | |

| 4.40 | 1.22 | |

| 0.50 | 0.26 |

Table 6 compares optimized sugar yields using the RSM and ANN techniques. Both techniques gave similar results, with RSM predicting an optimal yield of 89.34 g/100 g and experimental validation yielding 87.81 ± 2.61 g/100 g. The ANN also predicted an optimal yield of 86.87 g/100 g. The prediction error for both techniques was 1.0% for ANN and 1.7% for RSM. It can be concluded that the ANN predicted the optimum yield more accurately than the RSM. This is likely due to the fact that RSM can only account for two interaction effects in the correlation, while ANN is able to capture a wider range of nonlinearity.

Table 6.

Experimental and predicted TSC values of NADES-USAE under the optimal conditions of 45 min and 40 mL/g compared to CHWE a.

| Predicted values |

Experimental values |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RSM-BBD | ANN | NADES-USAE | CHWE | |

| Y (g/100 g) | 89.34 | 86.87 | 87.81 2.61 | 61.36 ± 3.06 |

| ΔE | 5.23 | 5.34 | 5.32 0.07 | 3.79 ± 0.01 |

| L* | 35.53 0.01 | 36.53 ± 0.01 | ||

| a* | 4.92 0.01 | 3.08 ± 0.01 | ||

| b* | 10.89 0.01 | 11.33 ± 0.06 | ||

temperature conditions for NADES-USAE and CHWE are 30 °C and 75 °C, respectively.

ANN and RSM are both powerful tools for modeling complex systems but have different strengths and weaknesses. RSM is known for its transparency and interpretability, allowing easy observation of the variables in the equation and direct measurement of the contribution of the different components to the system by evaluating their ANOVA Fisher’s F- values and coefficient signs. For example, as shown in Table 4, the L/S ratio has the highest F value (19.31) and a positive coefficient from Eq. (8), +3.56557, which means that it is the most significant factor with a positive effect on the predicted TSC values. Among the interaction terms, the temperature–time interaction () has the highest F value (24.46) and a negative coefficient (-0.054409), which means that it is the most dominant interaction term with a negative effect on the predicted TSC values. On the other hand, ANNs are known for their excellent ability to model nonlinear relationships and make accurate predictions. However, they are considered a “black box” model, which means that it is not easy to observe the internal mechanisms of the model and understand the contribution of each component.

3.6. Comparison between NADES-USAE and CHWE

The studied NADES-USAE process was tested against another benchmark: CHWE process, to compare its performance and determine the impact of using only water in the extraction process (Fig. 7). Conditions were selected based on the highest values predicted by the developed model, namely 30 °C, 45 min, and a liquid-to-solid ratio of 40 mL/g. Under these conditions, the NADES-USAE method gave a TSC of 87.81 ± 2.61 g/100 g, which was 43.1% higher than the TSC obtained by the CHWE method (61.36 ± 3.06 g/100 g) at 75 °C, 45 min, and 40 mL/g. This higher yield can presumably be attributed to the higher solubility of sugars in NADES compared with water and the cavitation bubbles generated by the ultrasonic waves, which effectively disrupted the cell walls, allowing solvents to penetrate more easily and improving the extraction yield [59].

Fig. 7.

Comparison between the experimentally measured TSC values of CHWE and NADES-USAE.

3.7. Characterization of extract and residue (spent mass)

3.7.1. Color analysis of the extract

Total color difference (ΔE) is a numerical value used to quantify the visual difference between two color samples. Industries such as textiles, printing, paint, and food use it to compare a sample to a reference standard. Lower values indicate minimal difference, while values above 3 are noticeable to the human eye. In this study, the total color difference of the extract obtained with NADES-USAE was compared with pure water USAE (TSC of 29.93 ± 1.49 g/100 g) as a reference to calculate ΔE. As shown in Fig. 8(A) and (B), runs 1, 2, 5, 8, 6, and 15 performed at 70 and 50 °C resulted in a reddish color. However, when comparing the runs conducted at 30 °C, run 11 (30 °C, 40 min, and 40 mL/g) showed the highest ΔE value, indicating the most yellowish color and the highest luminosity compared to the other runs. It should also be noted that compared to CHWE, ΔE was measured to be 3.79 ± 0.01. To better understand the relationship between the extraction conditions and ΔE, RSM was applied. It was found that the relationship between the extraction conditions and ΔE contained both quadratic and interaction effects, as shown in Fig. 8(C) and Eq. (9), in contrast to the sole interaction relationship in the TSC model. In addition, the results of ANOVA showed that temperature and L/S ratio had the largest influence on ΔE. The relationship between the operating conditions of the NADES-USAE process and the response variable (ΔE) is represented by the following model:

| (9) |

Fig. 8.

(A) Total color difference (ΔE) in NADES-USAE extracts under different conditions, (B) lab images of obtained extracts. (C) 2-D contour plots showing the interaction effects on ΔE. (D) Relative deviation plot for the RSM and ANN in predicting ΔE.

where , , and are the temperature (°C), time (min), and the L/S (mL/g), respectively.

As extraction temperature and time increased, so did the color difference. This is probably due to Maillard reactions, which are known to be favored by acidic conditions and high temperatures. On the other hand, it was found that a higher L/S ratio had a negative effect on ΔE, as a higher L/S ratio resulted in a lower ΔE. These results are in agreement with the findings in the literature [48]. The lowest ΔE was observed at R11 (extracted at 30 °C, 40 min, and 40 mL/g), and the largest difference was observed at R5 (extracted at 70 °C, 40 min, and 10 mL/g). Notably, the extract of R5 had a lower TSC content (47.15 g/100 g) than that of R11 (86.97 g/100 g). This suggests that a lower ΔE value indicates a higher TSC content, which is likely due to the degradation of sugars by Maillard reactions at higher extraction temperatures and longer extraction time.

For comparison purpose, an ANN model was also developed to model the relationship between temperature, time, and L/S ratio and the ΔE value, as shown in Fig. 6(A). The evaluation metrics, , , and , indicate a strong fit between the predictions of ANN and the experimental values (0.994, 1.22%, 0.26, respectively), as shown in Table 5. In addition, the ANN model was found to be more accurate in fitting the experimental data compared with the RSM model, as shown by the, , , and values of 0.977, 4.40%, and 0.50, respectively (Fig. 8(D)). Table 6 also shows that the RSM and ANN models predicted similar values for the optimal TSC conditions. The RSM predicted a ΔE of 5.23, experimental validation showed 5.32 ± 0.07, and the ANN predicted a ΔE of 5.34. The ANN had a deviation of 0.34% and the RSM had a deviation of 1.75%. The RSM and ANN models developed for both TSC and ΔE were integrated into user-friendly Excel spreadsheets for easy access and analysis, which are available in the Spreadsheet S.2 of the Supplementary Materials.

3.7.2. FT-IR of residue and extract

FT-IR analysis provides valuable information on the chemical changes that occur during the extraction process. Fig. 9(A) shows the FT-IR spectra of raw DFP, residues, and extracts after extraction by the CHWE and NADES-USAE methods. The broad peaks at 3300 cm−1 observed in all spectra are attributed to the stretching vibrations of the OH groups in carbohydrates or water and indicate the release and removal of these carbohydrates from the biomass to the extract media. The bands at 2910 and 2850 cm−1 are attributed to the stretching vibrations of the CHO group in phenols and carboxylic acids. The band at 1650 cm−1 is attributed to the stretching vibration of the aromatic C = C group and the antisymmetric vibration of COO−, which is detected in all samples. The shoulder at about 1650–1720 cm−1 refers to the vibrations in C = O bonds of acids, ketones, and aldehydes, which are more pronounced in the extract of NADES-USAE. The peak at 1170 cm−1, observed in the extract obtained using NADES-USAE is attributed to polysaccharides (C–O stretch). In addition, the overall spectra of all residues (raw, CHWE, and NADES-USAE) were similar, indicating that no significant chemical changes occurred during the extraction process and that the material’s chemical integrity remained unchanged despite sonication.

Fig. 9.

FT-IR spectra of (A) raw DFP compared to the residues after CHWE and NADES-USAE. (B) Comparison of FT-IR spectra of CHWE and NADES-USAE extracts.

Fig. 9(B) shows the comparison of the FT-IR spectra of CHWE and NADES-USAE extracts. The carbonyl absorption peaks were observed at 1720 and 1650 cm−1 in NADES-USAE. Moreover, the absorbance peak at 1170 cm−1 indicates the presence of C-C and C-O bonds. The absorbance band of − CCO at 950 cm−1 indicates that the structure of, Ch–+. is not destroyed during ChCl-CA synthesis, which further favors the phase transfer catalysis of choline chloride [60]. The C − H stretching vibrations at 2925 cm−1 are also observed in the spectrum. In the 1600 and 900 cm−1 regions, specific functional groups are detected only in the extract of NADES-USAE, which could be attributed to the extracted sugars according to the results of our previous study and to the solvent (NADES) used for the extraction [59]. Overall, the unique peaks observed in the NADES-USAE extract indicate that the system effectively extracts glucose, fructose, and sucrose while maintaining the chemical integrity of the material.

3.7.3. Morphological analysis of the residue

To further investigate the effects of ultrasonic irradiation and the use of NADES on the surface morphology of DFP residues, SEM was used to analyze and compare the raw DFP and its residues after CHWE and NADES-USAE extraction. Fig. 10 shows the surface morphology of (A) raw DFP, (B) DFP residue after CHWE, and (C) DFP residue after NADES-USAE. The surface of the raw DFP is relatively smooth and has no visible pores or ruptures. However, the surface of the residue after CHWE shows some signs of rupture, which are probably due to the high operating temperature. In contrast, the surface of the residue after NADES-USAE exhibits a rough texture with a significant amount of rupture, which is due to the breakage of lignin and cellulose by the use of NADES, as previously reported by Zhang et al. [61] In addition, the use of ultrasonic irradiation, which generates cavitation force, shear force, and shock waves, can alter the surface structure of the treated biomass by creating pores and disrupting the lignocellulose matrix [62]. These observations, along with the higher extraction yields observed using the NADES-USAE method compared to CHWE, provide further insight into the effectiveness of ultrasonic irradiation and NADES on the surface morphology of DFP residues.

Fig. 10.

Scanning electron micrographs of DFP (A) raw, (B) after CHWE, and (C) after NADES-USAE.

4. Conclusion

In this work, a green and effective method for the extraction of nutritious date sugar using natural deep eutectic solvents and ultrasound-assisted extraction was investigated. Careful design of a suitable NADES-USAE system was supported by COSMO-RS screening, response surface method and artificial neural network. First, 26 natural hydrogen bond donors were carefully screened using COSMO-RS for the extraction of sugars such as glucose, fructose, and sucrose. The most effective NADES, composed of choline chloride, citric acid, and water (1:1:1 with 20 wt% water), resulted in a sugar yield of 78.30 ± 3.91 g/100 g, which was superior to the conventional solvents ethanol and water. Further improvements with RSM and ANN resulted in an even higher sugar yield of 87.81 ± 2.61 g/100 g at a temperature of 30 °C, an extraction time of 45 min, and a solvent to DFP ratio of 40 mL/g. The NADES-USAE method was then compared to conventional hot water extraction (CHWE). NADES-USAE resulted in a 43.1% higher sugar recovery. In addition, the FT-IR and SEM analyses were used to study the changes in chemical and morphological properties of the extract and residual biomass after extraction, which showed unique variations highlighting the improved efficiency of NADES-USAE compared to CHWE.

The use of NADESs as green solvents in the extraction process improved the recovery of the nutritious date sugar compared to the use of conventional organic solvents, such as ethanol and methanol. In addition, the bioactive compounds present in dates are preserved, making them an attractive alternative to CHWE for industrial utilization. The study also opens new opportunities for the utilization of underutilized fruits and has potential implications for the food industry. Future research could extend this study by investigating the extraction of other bioactive compounds present in date fruits, such as phenolic acids, flavonoids, and carotenoids, with NADES.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

This work is supported by the project grant CIRA-2019-028 under the Competitive Internal Research Award scheme of Khalifa University, UAE and the Center for Membrane and Advanced Water Technology (CMAT) under grant RC2-2018-009, Khalifa University, UAE.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106514.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Zaid A., de Wet P. Date Palm Cultiv; in: 2002. Origin, geographical distribution and nutritional values of date palm. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hussain M.I., Farooq M., Syed Q.A. Nutritional and biological characteristics of the date palm fruit (Phoenix dactylifera L.) – a review. Food Biosci. 2020;34 doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2019.100509. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghnimi S., Umer S., Karim A., Kamal-eldin A. Date fruit (Phoenix dactylifera L.): an underutilized food seeking industrial valorization. NFS J. 2017;6:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.nfs.2016.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alasalvar C., Shahidi F. Nutritional composition, phytochemicals, and health benefits of dates, dried fruits phytochem. Heal. Eff. 2013:428–443. doi: 10.1002/9781118464663.ch23. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ali A., Waly M., Essa M.M., Devarajan S. Dates Prod. Process. Food Med; Values: 2014. Nutritional and Medicinal Value of Date Fruit. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yahia E.M. Postharvest Biol. Technol. Trop. SubTrop. Fruits, Woodhead Publishing Limited; 2011. Date (Phoenix dactylifera L.) pp. 1–19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gómez A.V., Tadini C.C., Biswas A., Buttrum M., Kim S., Boddu V.M., Cheng H.N. Microwave-assisted extraction of soluble sugars from banana puree with natural deep eutectic solvents (NADES) Lwt. 2019;107:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2019.02.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.AlYammahi J., Rambabu K., Thanigaivelan A., Bharath G., Hasan S.W., Show P.L., Banat F. Advances of non-conventional green technologies for phyto-saccharides extraction: current status and future perspectives. Phytochem. Rev. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s11101-022-09831-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tomasik P. CRC Press; London: 2003. Chemical and functional properties of food saccharides. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samarawira I., East N., Samarawira I. Date palm, potential source for refined sugar. Econ. Bot. 1983;37:181–186. doi: 10.1007/BF02858783. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gamal A El Sharnouby S.M.A. Liquid Sugar Extraction from Date Palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) Fruits, J. Food Process. Technol. 2014;5 doi: 10.4172/2157-7110.1000402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martins M.A.R., Pinho S.P., Coutinho J.A.P. Insights into the nature of eutectic and deep eutectic mixtures. J. Solution Chem. 2019;48:962–982. doi: 10.1007/s10953-018-0793-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.A.P. Abbott, G. Capper, D.L. Davies, R.K. Rasheed, V. Tambyrajah, Novel solvent properties of choline chloride / urea mixtures †, (2003) 70–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Dai Y., Witkamp G.J., Verpoorte R., Choi Y.H. Natural deep eutectic solvents as a new extraction media for phenolic metabolites in carthamus tinctorius L. Anal. Chem. 2013;85:6272–6278. doi: 10.1021/ac400432p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang J., Guo X., Xu T., Fan L., Zhou X., Wu S. Ionic deep eutectic solvents for the extraction and separation of natural products. J. Chromatogr. A. 2019;1598:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2019.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang Y., Pan Z., Chen Z., Fei Y., Zhang J., Yuan J., Zhang L., Zhang J. Ultrasound-assisted natural deep eutectic solvents as separation-free extraction media for hydroxytyrosol from olives. ChemistrySelect. 2020;5:10939–10944. doi: 10.1002/slct.202002026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang L., Wang M. Optimization of deep eutectic solvent-based ultrasound-assisted extraction of polysaccharides from Dioscorea opposita Thunb. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017;95:675–681. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.11.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alrugaibah M., Washington T.L., Yagiz Y., Gu L. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of phenolic acids, flavonols, and flavan-3-ols from muscadine grape skins and seeds using natural deep eutectic solvents and predictive modelling by artificial neural networking. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;79 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koutsoukos S., Tsiaka T., Tzani A., Zoumpoulakis P., Detsi A. Choline chloride and tartaric acid, a natural deep eutectic solvent for the efficient extraction of phenolic and carotenoid compounds. J. Clean. Prod. 2019;241 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118384. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diego J.R., Gabriela G. Deep eutectic solvents: synthesis. Properties Appl. Ed. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dai Y., Witkamp G.J., Verpoorte R., Choi Y.H. Tailoring properties of natural deep eutectic solvents with water to facilitate their applications. Food Chem. 2015;187:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.03.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dwamena A.K. Recent advances in hydrophobic deep eutectic solvents for extraction. Separations. 2019;6 doi: 10.3390/separations6010009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cai C., Wang Y., Yu W., Wang C., Li F., Tan Z. Temperature-responsive deep eutectic solvents as green and recyclable media for the efficient extraction of polysaccharides from Ganoderma lucidum. J. Clean. Prod. 2020;274 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Y., Garzon J., Friesen J.B., Zhang Y., McAlpine J.B., Lankin D.C., Chen S.N., Pauli G.F. Countercurrent assisted quantitative recovery of metabolites from plant-associated natural deep eutectic solvents. Fitoterapia. 2016;112:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2016.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dai Y., Van Spronsen J., Witkamp G.J., Verpoorte R., Choi Y.H. Ionic liquids and deep eutectic solvents in natural products research: Mixtures of solids as extraction solvents. J. Nat. Prod. 2013;76:2162–2173. doi: 10.1021/np400051w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lemaoui T., Abu Hatab F., Darwish A.S., Attoui A., Hammoudi N.E.H., Almustafa G., Benaicha M., Benguerba Y., Alnashef I.M. Molecular-Based Guide to Predict the pH of Eutectic Solvents: Promoting an Efficient Design Approach for New Green Solvents, ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021;9:5783–5808. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c07367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lemaoui T., Darwish A.S., Attoui A., Hatab F.A., El N., Hammoudi H., Benguerba Y., Vega L.F., Alnashef I.M. Predicting the density and viscosity of hydrophobic eutectic solvents : towards the development of sustainable solvents †. Green Chem. 2020:15–17. doi: 10.1039/d0gc03077e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.M. Diedenhofen, F. Eckert, A. Klamt, C. Gmbh, C. Kg, B. Strasse, D.- Leverkusen, Compounds in Ionic Liquids Using COSMO-RS, Engineering. (2003) 475–479.

- 29.Gao M.Z., Cui Q., Wang L.T., Meng Y., Yu L., Li Y.Y., Fu Y.J. A green and integrated strategy for enhanced phenolic compounds extraction from mulberry (Morus alba L.) leaves by deep eutectic solvent. Microchem. J. 2020;154 doi: 10.1016/j.microc.2020.104598. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith E.L., Abbott A.P., Ryder K.S. Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs) and Their Applications. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:11060–11082. doi: 10.1021/cr300162p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gontrani L., Plechkova N.V., Bonomo M. In-Depth Physico-Chemical and Structural Investigation of a Dicarboxylic Acid/Choline Chloride Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent (NADES): A Spotlight on the Importance of a Rigorous Preparation Procedure. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019;7:12536–12543. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b02402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bai C., Wei Q., Ren X. Selective Extraction of Collagen Peptides with High Purity from Cod Skins by Deep Eutectic Solvents. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017;5:7220–7227. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.7b01439. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abbott A.P., Boothby D., Capper G., Davies D.L., Rasheed R.K. Deep Eutectic Solvents formed between choline chloride and carboxylic acids: Versatile alternatives to ionic liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:9142–9147. doi: 10.1021/ja048266j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao B.Y., Xu P., Yang F.X., Wu H., Zong M.H., Lou W.Y. Biocompatible Deep Eutectic Solvents Based on Choline Chloride: Characterization and Application to the Extraction of Rutin from Sophora japonica. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2015;3:2746–2755. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.5b00619. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sert M., Arslanoğlu A., Ballice L. Conversion of sunflower stalk based cellulose to the valuable products using choline chloride based deep eutectic solvents. Renew. Energy. 2018;118:993–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2017.10.083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song Y., Shi X., Ma S., Yang X., Zhang X. A novel aqueous gallic acid-based natural deep eutectic solvent for delignification of hybrid poplar and enhanced enzymatic hydrolysis of treated pulp. Cellulose. 2020;27:8301–8315. doi: 10.1007/s10570-020-03342-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sarmad S., Nikjoo D., Mikkola J.P. Amine functionalized deep eutectic solvent for CO2 capture: Measurements and modeling. J. Mol. Liq. 2020;309 doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.113159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mohammadi B., Shekaari H., Zafarani-Moattar M.T. Selective separation of α-tocopherol using eco-friendly choline chloride – Based deep eutectic solvents (DESs) via liquid-liquid extraction. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021;617 doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2021.126317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adeyemi I., Abu-Zahra M.R.M., AlNashef I.M. Physicochemical properties of alkanolamine-choline chloride deep eutectic solvents: Measurements, group contribution and artificial intelligence prediction techniques. J. Mol. Liq. 2018;256:581–590. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2018.02.085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hayyan M., Aissaoui T., Hashim M.A., AlSaadi M.A., Hayyan A. Triethylene glycol based deep eutectic solvents and their physical properties. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2015;50:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jtice.2015.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Triolo A., Lo F., Brehm M., Di V., Russina O. Liquid structure of a choline chloride-water natural deep eutectic solvent : A molecular dynamics characterization. J. Mol. Liq. 2021;331 doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.115750. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang H., Ferrer M.L., Rolda J., Monte F. Brillouin Spectroscopy as a Suitable Technique for the Determination of the Eutectic Composition in Mixtures of Choline Chloride and Water. 2020 doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.0c01919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rahman S., Raynie D.E. Thermal behavior, solvatochromic parameters, and metal halide solvation of the novel water-based deep eutectic solvents. J. Mol. Liq. 2021;324 doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.114779. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rambabu K., AlYammahi J., Thanigaivelan A., Bharath G., Sivarajasekar N., Velu S., Banat F. Sub-critical water extraction of reducing sugars and phenolic compounds from date palm fruit, Biomass Convers. Biorefinery. 2022:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s13399-022-02386-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ben Romdhane M., Haddar A., Ghazala I., Ben Jeddou K., Helbert C.B., Ellouz-Chaabouni S. Optimization of polysaccharides extraction from watermelon rinds: Structure, functional and biological activities. Food Chem. 2017;216:355–364. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suzanne N.S. Laboratory Manual; 2010. Food Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vieira L.M., Marinho L.M.G., Rocha J.d.C.G., Barros F.A.R., Stringheta P.C. Chromatic analysis for predicting anthocyanin content in fruits and vegetables. Food Sci. Technol. 2019;39(2):415–422. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kutlu N., Kamiloglu A., Elbir T. Optimization of Ultrasound Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Tarragon (Artemisia dracunculus L.) Using Box-Behnken Design, Biomass Convers. Biorefinery. 2022;12:5397–5408. doi: 10.1007/s13399-022-02594-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gutiérrez M.C., Ferrer M.L., Mateo C.R., Del Monte F. Freeze-drying of aqueous solutions of deep eutectic solvents: A suitable approach to deep eutectic suspensions of self-assembled structures. Langmuir. 2009;25:5509–5515. doi: 10.1021/la900552b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pereira M.G., Hamerski F., Andrade E.F., Scheer A.d.P., Corazza M.L. Assessment of subcritical propane, ultrasound-assisted and Soxhlet extraction of oil from sweet passion fruit (Passiflora alata Curtis) seeds. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2017;128:338–348. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Valderrama J.O., Sanga W.W., Lazzús J.A. Critical properties, normal boiling temperature, and acentric factor of another 200 ionic liquids. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2008;47:1318–1330. doi: 10.1021/ie071055d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Almustafa G., Darwish A.S., Lemaoui T., O’Conner M.J., Amin S., Arafat H.A., AlNashef I. Liquification of 2,2,4-trimethyl-1,3-pentanediol into hydrophobic eutectic mixtures: A multi-criteria design for eco-efficient boron recovery. Chem. Eng. J. 2021;426 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2021.131342. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Almustafa G., Sulaiman R., Kumar M., Adeyemi I., Arafat H.A., AlNashef I. Boron extraction from aqueous medium using novel hydrophobic deep eutectic solvents. Chem. Eng. J. 2020;395 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2020.125173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.H. Knapp, R. Doring, I. Oellrich, U. Plocker, J. Prausnitz, Vapor-liquid equilibria for mixtures of low boiling substances, DECHEMA. (1982).

- 55.Spencer C.F., Danner R.P. Improved Equation for Prediction of Saturated Liquid Density. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 1972;17:236–241. doi: 10.1021/je60053a012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen M., Lahaye M. Natural deep eutectic solvents pretreatment as an aid for pectin extraction from apple pomace. Food Hydrocoll. 2021;115 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2021.106601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang C.W., Xia S.Q., Ma P.S. Facile pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass using deep eutectic solvents. Bioresour. Technol. 2016;219:1–5. doi: 10.1016/J.BIORTECH.2016.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lin T., Liu Y., Lai C., Yang T., Xie J., Zhang Y. The effect of ultrasound assisted extraction on structural composition, antioxidant activity and immunoregulation of polysaccharides from Ziziphus jujuba Mill var. spinosa seeds. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018;125:150–159. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.08.078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.J. AlYammahi, A. Hai, T. Arumugham, S. Hasan, F. Banat, Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Highly Nutritious Date Sugar from Date Palm (Phoenix Dactylifera) Fruit Powder: Parametric Optimization and Kinetic Modeling, (n.d.). 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.106107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Wang J., Liu Y., Zhou Z., Fu Y., Chang J. Epoxidation of Soybean Oil Catalyzed by Deep Eutectic Solvents Based on the Choline Chloride-Carboxylic Acid Bifunctional Catalytic System. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017;56:8224–8234. doi: 10.1021/acs.iecr.7b01677. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang H., Wu S. Efficient Sugar Release by Acetic Acid Ethanol-Based Organosolv Pretreatment and Enzymatic Saccharification. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014;62(48):11681–11687. doi: 10.1021/jf503386b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee K.M., Zanil M.F., Chan K.K., Chin Z.P., Liu Y.C., Lim S. Synergistic ultrasound-assisted organosolv pretreatment of oil palm empty fruit bunches for enhanced enzymatic saccharification: An optimization study using artificial neural networks. Biomass and Bioenergy. 2020;139 doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2020.105621. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.