Abstract

Institutional review boards (IRBs) are permitted by regulation to seek assistance from outside experts when reviewing research applications that are beyond the scope of expertise represented in their membership. There is insufficient understanding, however, of when, why, and how IRBs consult with outside experts, as this practice has not been the primary focus of any published literature or empirical study to date. These issues have important implications for IRB quality. The capacity IRBs have to fulfill their mission of protecting research participants without unduly hindering research is influenced by IRBs’ access to and use of the right type of expertise to review challenging research ethics, regulatory, and scientific issues. Through a review of the regulations and standards permitting IRBs to draw on the competencies of outside experts and through examination of the needs, strategies, challenges, and concerns related to doing so, we identify critical gaps in the existing literature and set forth an agenda for future empirical research.

Keywords: institutional review board, IRB, human research protection program, HRPP, research ethics, human subjects research, outside expertise, consultant, competencies

Given the exposure of research participants to risks and burdens for the benefit of society, and the associated potential for exploitation, research involving human subjects requires oversight and regulation. For both the protection of research participants and the promotion of high-quality research, institutional review boards (IRBs), the bodies charged with reviewing and approving research on human subjects, are expected and required to have—or have access to—adequate regulatory, ethical, and scientific expertise. IRB members are selected with the goal of creating a board with the combined expertise needed to review the portfolio of protocols likely to come before it, but sometimes additional expertise will need to be found elsewhere.

Although federal regulations governing federally funded research with humans set forth several general and specific requirements for IRB membership, more work is needed to better understand adequate (and ideal) board composition and expertise, as well as how the expertise of existing members can best be used. Relatedly, it is also important to understand whether, when, and how best to engage with experts beyond those who are IRB members, which is our focus here. Recognizing that even appropriately constituted IRBs may need additional insight, the regulations explicitly allow IRBs to call upon the expertise of those who are not appointed members. Seeking such assistance may be essential to an IRB’s ability to appropriately safeguard the rights and welfare of research participants, making the capacity to successfully recruit, engage, and use outside experts a critical aspect of IRB quality. Yet there has been limited discussion of when, why, and how IRBs consult with outside experts—and when, why, and how they should do so. Further empirical study of this area is needed to inform appropriate use of outside experts and ultimately to guide IRBs.

To advance this goal, we first present a cohesive view of known regulations, standards, and practices to define the landscape of what is known about IRB use of outside experts. We then examine unmet needs, identify strategies, and assess challenges and concerns related to external consultation. Critical gaps in the literature serve to ground a proposed research agenda for future empirical study of IRBs using outside experts.

REGULATORY CONTEXT AND GUIDANCE

The potential consequences of shortfalls in IRB expertise are significant.1 An IRB unfamiliar with a specific research domain, participant population, and/ or study design can misestimate relevant benefits and misidentify risks of research studies they review, overlook a study’s methodological flaws, fail to identify inconsistencies of the study, and miss important details relevant to adequate informed consent, among other problems. If IRBs do not adequately assess these essential elements, legitimate doubts will arise about whether an IRB has truly fulfilled its primary duty of participant protection and ensured that the regulatory criteria for approving a proposed study are satisfied. Shortcomings in IRB expertise may also result in inefficiencies or errors that hinder important, ethical research due to misunderstandings. For these reasons, adequate expertise is a critical issue for IRB quality.

The Common Rule addresses this issue by requiring that IRBs be composed of “at least five members, with varying backgrounds to promote complete and adequate review of research activities commonly conducted by the institution.” It also requires that IRBs “be sufficiently qualified through the experience and expertise of its members … to ascertain the acceptability of proposed research in terms of institutional commitments (including policies and resources) and regulations, applicable law, and standards of professional conduct and practice.” There is also a requirement for special expertise when an IRB regularly reviews research involving vulnerable populations or people who may be disproportionately susceptible to pressure or persuasion, in which case the regulations call for “inclusion of one or more individuals who are knowledgeable about and experienced in working with these categories of subjects.”

The Common Rule also permits IRBs to enlist nonvoting, outside experts to assist with reviews as needed. Specifically, it states that an “IRB may, in its discretion, invite individuals with competence in special areas to assist in the review of issues that require expertise beyond or in addition to that available on the IRB.”2 U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations for clinical investigations are identical on this point, aside from a reference to “review of complex issues” as the focus of the consultation.3

The Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP), responsible for interpreting and enforcing the Common Rule at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, further explains that when an IRB is establishing conditions for approving a research protocol that requires specific expertise, it “could designate … [a] consultant with particular subject matter expertise who is not an IRB member” to review responsive material from investigators and help determine whether those conditions have been satisfied.4 OHRP also notes that IRBs “may use a consultant to assist in the review” when they encounter “studies involving science beyond the expertise of the members.”5 Finally, OHRP encourages IRBs to establish written procedures to govern “the process to identify the need for a consultant, [the process] to choose a consultant, and the consultant’s participation in the review of research.”6 It offers no examples of such procedures, however. Several government bodies and nongovernmental organizations in the United States (e.g., the Department of Health and Human Services, the FDA, and OHRP) and elsewhere have developed guidelines standards that address the extent to which IRBs are permitted to use outside experts (see appendix A, which is available online, with appendix B; information about accessing the appendices is in the “Supporting Information” section at the end of this article).

Deeper study of IRB engagement with outside experts could help identify strengths and weaknesses of existing practices, facilitate learning from the experiences of other IRBs, and indicate areas where further guidance may be needed.

International research ethics guidelines, including those provided by the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences, similarly acknowledge the role of outside experts for research ethics committees, noting that if such committees “do not have the relevant expertise to adequately review a protocol, they must consult with external persons with the proper skills or certification.”7 The World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) Operational Guidelines for Ethics Committees that Review Biomedical Research provides that ethics committees “may call upon, or establish a standing list of, independent consultants who may provide special expertise to the [ethics committee] on proposed research protocols. These consultants may be specialists in ethical or legal aspects, specific diseases or methodologies, or they may be representatives of communities, patients, or special interest groups.” The WHO guidelines also call for committees to establish “[t]erms of reference for independent consultants.”8 Several other countries similarly recognize the need for ad-hoc, non-member, outside experts to periodically inform IRB decision-making—while also pushing for review of IRB membership if outside experts seem to be needed too often (see appendix B).

DEFINING OUTSIDE EXPERTISE

Based on these regulations and guidance, we define an “outside expert” as any individual offering consultation to an IRB to inform its decision on a specific protocol but who stands apart from that IRB’s membership, even if part of the same institution. Thus, an individual who serves as a member of one IRB panel at an institution would be an outside expert if providing advice to another IRB panel at that institution of which they are not a member. In contrast, individuals who provide standard training to the IRB as part of ongoing member education, as well as individuals who are asked to join the IRB as voting members (or alternates) on the basis of their expertise, fall outside our definition of “outside experts.” We also do not consider consultation with federal regulators (e.g., OHRP or FDA) to be the type of outside expertise that we are concerned with here because such inquiries are typically aimed at obtaining formal regulatory decisions. Finally, we do not recognize as outside experts members of other research review bodies that may have distinct oversight obligations within an institution but that are not advisory to the IRB, such as radiation safety committees or pharmacy review boards—unless the IRB specifically calls on those individuals for guidance on IRB-related matters.

THE VALUE AND UNKNOWNS OF OUTSIDE EXPERTISE

Although applicable regulations and guidance clearly permit and encourage the use of outside experts, they do not provide much insight as to exactly when and how IRBs should do so, even as the human subjects research that IRBs are tasked with reviewing has become increasingly complex over the past several decades. Literature on the use of outside experts is also sparse, and no study, to our knowledge, has reported empirical data on this topic. As a result, it is unclear how IRBs determine that they need to call upon outside experts, how they identify experts once the need is clear, what logistical barriers may arise (e.g., with regard to payment, conflict of interest, and verification of expertise), what value outside experts add to the review process, and how IRBs evaluate expert input. The gaps in understanding on each of these questions are important from the perspective of IRB quality, as IRBs may not be sufficiently relying on the option to call upon outside experts, may have difficulty identifying experts, or may even be getting bad expert advice. From a more positive standpoint, if some IRBs have developed strong processes for engaging outside experts in ways that improve the quality of their reviews, sharing those lessons more broadly within their institution’s human research protection program (HRPP) community would be helpful. Overall, as Vawter et al. note, IRBs would benefit from guidance on how to readily identify if they have the requisite expertise needed to conduct a comprehensive and quality review and, if not, how to seek additional resources.9

Inevitable gaps in IRB expertise.

The few publications that reference outside experts acknowledge that it is impossible for any IRB to claim an exhaustive range of methodological and disciplinary expertise within their membership.10 This is true for many reasons. Novel study designs (e.g., cluster or step-wedged trials), research with emerging technologies (e.g., artificial intelligence or mobile apps), or research in the midst of a global pandemic, for example, can raise unique issues an IRB may not have prior experience reviewing. The topic of study may be especially niche (e.g., a rare genetic disease for which there are few known experts), or legal issues beyond the IRB’s practical knowledge can arise (e.g., state-based definitions of a legally authorized representative for purposes of consent or laws about mandatory child-abuse reporting in a specific country). Moreover, the proposed study may involve participants or communities for whom engagement and consultation are warranted (e.g., research involving Indigenous or Aboriginal peoples).

As Borenstein rightly asserts, the “expertise problem” will only intensify as research becomes more nuanced, technical, and domain specific.11 Some institutions have responded to this challenge by developing more specialized IRB panels or relying on commercial IRBs that have the resources to provide this range (e.g., Advarra and WIRB-Copernicus Group). Additional member training and regulatory guidance may also help, but these solutions are not possible in all circumstances, given resource constraints, and there will always be unique issues that come up for which no existing IRB member has the right type of knowledge.

To better understand what resources IRBs find useful when faced with ethically challenging mental health research, Sirotin et al. surveyed IRB chairs and found that they most valued increased access to experts in relevant scientific disciplines, research ethicists, international research context experts, professionals who work with a specific population, and patient advocates. Notably, an experienced chairperson of a high-volume IRB expressed concern about access to experts from pertinent disciplines: “We still continue to struggle getting certain disciplines onto our panel. It’s a large time commitment.”12 This underscores the importance of access to outside experts to fill those gaps. Yet appropriate outside experts can also be in short supply. Anderson and DuBois13 and Klitzman14 highlight conflicts of interest when the principal investigator is among the few experts the IRB could consult on a proposed study due to its novelty or specificity.

Implications for IRB composition.

Although the Common Rule requires a minimum of five regular members, IRBs often exceed this minimum to ensure voter quorum and avoid reviewer burnout, among other reasons.15 Alternatively, keeping the regular member roster small and assembling a cadre of alternates or non-member outside experts may be able to provide similar domain coverage and necessary quorum while keeping overhead low. Candilis et al. highlight ways that IRB membership size can create tensions relating to member attendance, preparation, and participation. The authors note that large IRB memberships are most beneficial if all members contribute to the discussion and deliberation. However, the authors’ observational study of IRB member contributions at major academic medical centers found the IRB chair and assigned reviewers led most review discussions. “At any given meeting,” Candilis et al. report, “between 6.7% and 44.4% of all members said nothing, with 23.9% of members at all the meetings we observed remaining silent throughout the entire meeting.”16 The authors concluded that IRBs might be larger than necessary since most meeting attendees represent a “silent majority” that do not substantively contribute to the review. Furthermore, Candilis et al. contend there would be no difference in review quality if regular membership remained low and IRBs relied instead on outside experts to contribute their expertise when reviewing specific applications. This is an empirical question, but at the very least, it assumes access to relevant experts.

Perception of IRB use of outside experts.

IRB composition and expertise may also have implications for trust in and satisfaction with IRB decisions. Keith-Spiegel et al. surveyed a national sample of biomedical and social-behavioral scientists on the importance of 45 dimensions of IRB responsibilities and functions. The findings suggest that, in IRB review, researchers prioritize “procedural justice,” that is, adherence to transparent and fair decision-making processes. One component of procedural justice under the Keith-Spiegel et al. model is “[a]n IRB that recognizes when it lacks sufficient expertise to evaluate a protocol and seeks outside experts.”17 In addition to promoting fairness and accuracy in the IRB’s assessment of proposed research, recognizing the need to seek outside expertise may benefit the IRB-researcher relationship by minimizing concerns about the IRB’s competence. Unfortunately, there is no similar study or empirical data available that reveals participants’ perspectives on the IRB’s role and function.18

RESEARCH AGENDA

The preceding discussion of the limited literature demonstrates how little is known about IRB use of outside experts. There is a lack of understanding about the frequency of engagement, the qualifications of outside consultants, what effect their insights have on IRB decisions, the impact of their contributions on IRB quality, and how to make these consults most productive, among other questions. Deeper study of IRB engagement with outside experts could help address these knowledge gaps, identify strengths and weaknesses of existing practices, facilitate learning from the experiences of other IRBs, and indicate areas where further guidance may be needed.

However, empirical analysis of the motivations, processes, and methods for consulting outside experts in IRB review may be challenging. First, the IRB personnel who would be critical to such research may be reticent to participate out of concern that such inquiry might expose their IRB’s membership to be inadequate or show that it is not engaging outside expertise in situations where it should. Additionally, IRB administrators and members are often stretched thin; participating in research about IRB processes can distract from other institutional and regulatory priorities. However, these challenges can potentially be mitigated by emphasizing that all research results will be kept confidential and keeping surveys and interviews as short as possible. Participation may also be encouraged by emphasizing the value of the research question to promote IRB quality and promising to share research results and recommendations. To the extent that IRBs question how best to engage outside experts, the opportunity to learn from a rigorous needs assessment may be an important motivator.

A second challenge that arises when studying IRB policies and practices is the heterogeneity of IRBs, which can make it difficult to identify generalizable benchmarks and offer guidance that will be suitable for all boards. For example, in this context, some IRBs may not have standard operating procedures for engaging with outside experts, or administrators may lack the records, metrics, or experience to reliably report on this issue. In addition, IRBs may not agree on what constitutes appropriate or necessary expertise or how it should be assessed. Further, logistical or practical barriers, such as budgetary constraints, human resource restrictions, contract requirements, and confidentiality protections, may prevent IRBs from engaging outside experts in ways that they think would be most beneficial. However, all these things would be helpful to empirically document to inform feasible recommendations about the use of outside expertise going forward and to address current barriers and shortcomings.

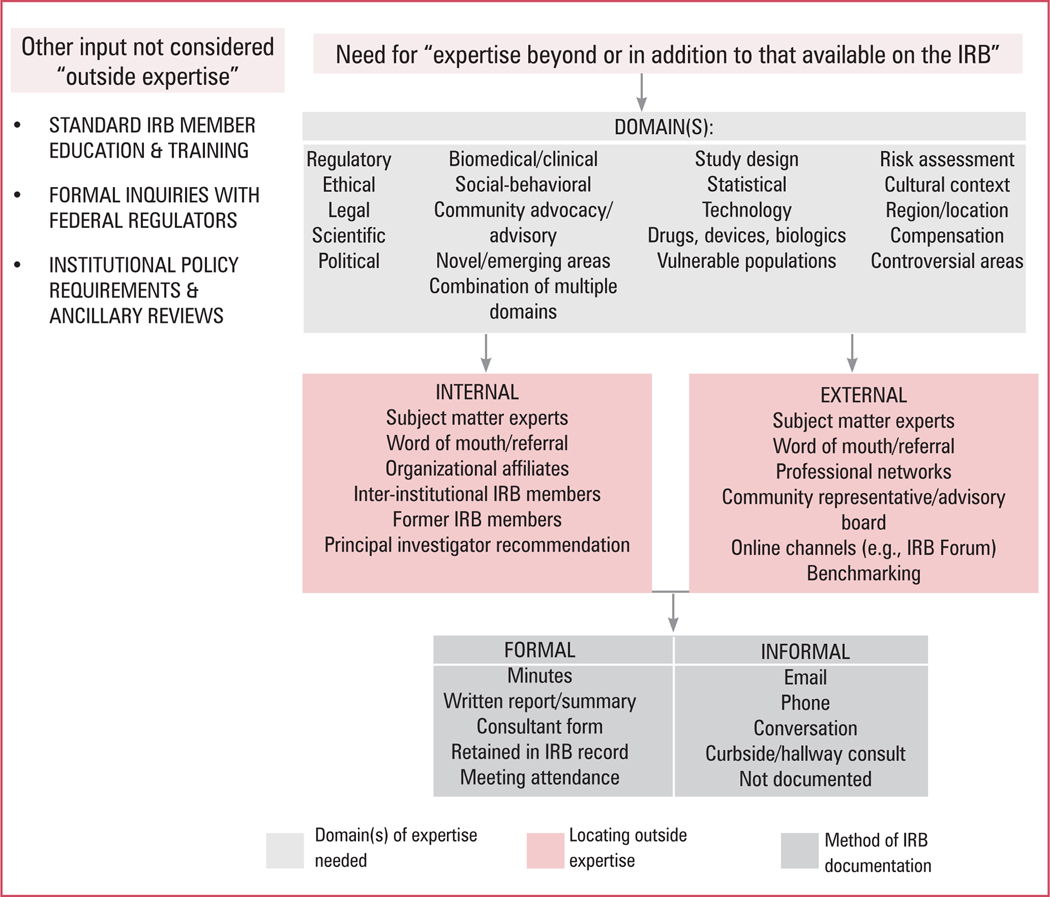

To guide future empirical research on these issues, we constructed a process map for obtaining outside expert review that provides an overview of core elements for study, including (1) the domains in which outside expertise is needed and sought, (2) how outside experts are located, and (3) the methods by which outside expertise is offered and documented (see figure 1). Within this conceptual model, our team has a mixed-methods study underway to examine consult frequency and contextual factors that motivate IRBs to request review help, characteristics of outside experts, and strategies used to identify appropriate outside experts. Other beneficial areas of study could include research with consultants who have directly served as outside experts, IRB perspectives on the types of expertise most valuable to them, researcher perspectives regarding areas in which IRB expertise is lacking, and an assessment of informal guidance provided on online IRB forums, among others.♦

Figure 1. IRB Outside Expertise Process Map.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

The appendices are available in the “Supporting Information” section for the online version of this article and via Ethics & Human Research’s “Supporting Information” https://www.thehastingscenter.org/supporting-information-ehr/.

Contributor Information

Kimberley Serpico, IRB operations in the Office of Regulatory Affairs and Research Compliance at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health and an EdD candidate at Vanderbilt University.

Vasiliki Rahimzadeh, Stanford Center for Biomedical Ethics at Stanford University.

Emily E. Anderson, Neiswanger Institute for Bioethics in the Stritch School of Medicine at Loyola University Chicago.

Luke Gelinas, IRB and a senior advisor at The Multi-Regional Clinical Trials Center of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard.

Holly Fernandez Lynch, John Russell Dickson, MD, Presidential Assistant Professor of Medical Ethics and Health Policy at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania..

REFERENCES

- 1.Vawter DE, Gervais KG, and Freeman TB, “Strategies for Achieving High-Quality IRB Review,” American Journal of Bioethics 4, no. 3 (2004): 74–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Protection of Human Subjects, 45 C.F.R. 46 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institutional Review Boards, 21 C.F.R. 56 (2019) (italics added). [Google Scholar]

- 4.“Approval of Research with Conditions: OHRP Guidance,” U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office for Human Research Protections, November 10, 2010, https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/guidance/guidance-on-irb-approval-of-research-with-conditions-2010/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 5.“Attachment B: Recommendation on IRB Membership and Definition of Non-scientist under 45 CFR 46 and 21 CFR 56,” U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office for Human Research Protections, January 24, 2011, https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/sachrp-committee/recommendations/2011-january-24-letter-attachment-b/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 6.“Institutional Review Board Written Procedures: Guidance for Institutions and IRBs,” U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office for Human Research Protections, May 2018, https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/guidance/institutional-issues/institutional-review-board-written-procedures/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS), International Ethical Guidelines for Health-related Research Involving Humans, 4th ed. (Geneva: CIOMS, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization (WHO), Operational Guidelines for Ethics Committees that Review Biomedical Research, (Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2000), at https://www.who.int/tdr/publications/training-guideline-publications/operational-guidelines-ethics-biomedical-research/en/, p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vawter Gervais, and Freeman, “Strategies for Achieving High-Quality IRB Review.” [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ibid.; Borenstein, “The Expanding Purview: Institutional Review Boards and the Review of Human Subjects Research,” Accountability in Research 15, no. 3 (2008): 188–204; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Sirotin N, et al., “IRBs and Ethically Challenging Protocols: Views of IRB Chairs about Useful Resources,” IRB: Ethics & Human Research 32, no. 5 (2010): 10–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borenstein, “The Expanding Purview.” [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sirotin et al., “IRBs and Ethically Challenging Protocols,” 12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson EE, and DuBois JM, “IRB Decision-Making with Imperfect Knowledge: A Framework for Evidence-Based Research Ethics Review,” Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 40, no. 4 (2012): 951–69.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klitzman RL, “How IRBs View and Make Decisions about Social Risks,” Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics 8, no. 3 (2013): 58–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Candilis PJ, et al. , “The Silent Majority: Who Speaks at IRB Meetings?,” IRB: Ethics & Human Research 34, no. 4 (2012): 15–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ibid, 17. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keith-Spiegel P, Koocher G, and Tabachnick B, “What Scientists Want from Their Research Ethics Committee,” Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics 1, no. 1 (2006): 67–82, at 70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicholls SG, et al. , “A Scoping Review of Empirical Research Relating to Quality and Effectiveness of Research Ethics Review,” PLoS One 10, no. 7 (2015): E0133639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.